Mr. B, age 23, is admitted to an inpatient psychiatric unit for depression. During his hospitalization, Mr. B becomes fixated on obtaining specific medications, including controlled substances. He is treated by Dr. M, a psychiatrist early in her training. In a difficult conversation, Dr. M tells Mr. B he will not be prescribed the medications he is requesting and explains why. Mr. B responds by jumping across a table and repeatedly punching Dr. M. Unit staff restrains Mr. B, and Dr. M leaves to seek medical care.

Assaults perpetrated against employees on inpatient psychiatric units are common.1 Assaults on physicians can occur at any level of training, including during residency.2 This is not a new phenomenon: concerns about patients assaulting psychiatrists and other inpatient staff have been reported for decades.3-5 Most research surrounding this topic has focused on risk factors for violence and prevention.6 Research regarding the aftermath of a patient assault and what services an employee requires have primarily centered on nurses.7,8

Practical guidance for a psychiatrist who has been assaulted and wants to return to work is difficult to find. This article provides strategies to help psychiatrists (and their colleagues) transition back to work after being the victim of a patient assault. While the recommendations we provide can be applied to trainees as well as attending physicians, there are some considerations specific to residents who have been assaulted (Box9,10).

Box

Psychiatry residents who are the targets of violence (such as Dr. M) require unique management, including evaluation of how the assault impacts their training and the role of the program director. Additionally, according to the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Common Program Requirements, residency programs must address residents’ wellbeing, including “evaluating workplace safety data and addressing the safety of residents and faculty members.”9 These specific considerations for residents are guided by the most recent program requirements through ACGME, as well as the policies of the specific institution overseeing the residency. Some institutions have developed resources to assist in this area, such as the WELL Toolkit from the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center.10

Having a plan for after an assault

The aftereffects of a patient assault can take a significant toll on the individual who is assaulted. A 2021 article about psychiatric mental health nurses by Dean et al8 identified multiple potential repercussions of unaddressed workplace violence, including role confusion, job dissatisfaction, decreased resiliency traits, poor coping methods, increased attrition rate, and increased expenditures related to assault injuries. Providing appropriate services and having a plan for how best to support an assaulted psychiatrist are likely to mitigate these effects. This can be grouped into 4 categories: 1) seeking immediate care, 2) removing the patient from your care, 3) easing back into the environment, and 4) finding long-term support.

1. Seeking immediate care

“Round or be rounded on” is a phrase that encapsulates many physicians’ attitude regarding their own health care and may contribute to their refusal of medical care following acute trauma such as an assault. Feelings of shock, guilt, and shame may also lead to a psychiatrist’s initial hesitation to seek treatment. However, it is important for the victim of an assault to be promptly evaluated and treated.

Elevated adrenaline in the aftermath of a physical engagement may mask the perception of injuries, and there is a risk for exposure to blood-borne pathogens. Regardless of the severity of injuries, seeking medical care establishes documentation of any injuries that can later serve as a record for workers’ compensation claims or if legal action is taken.

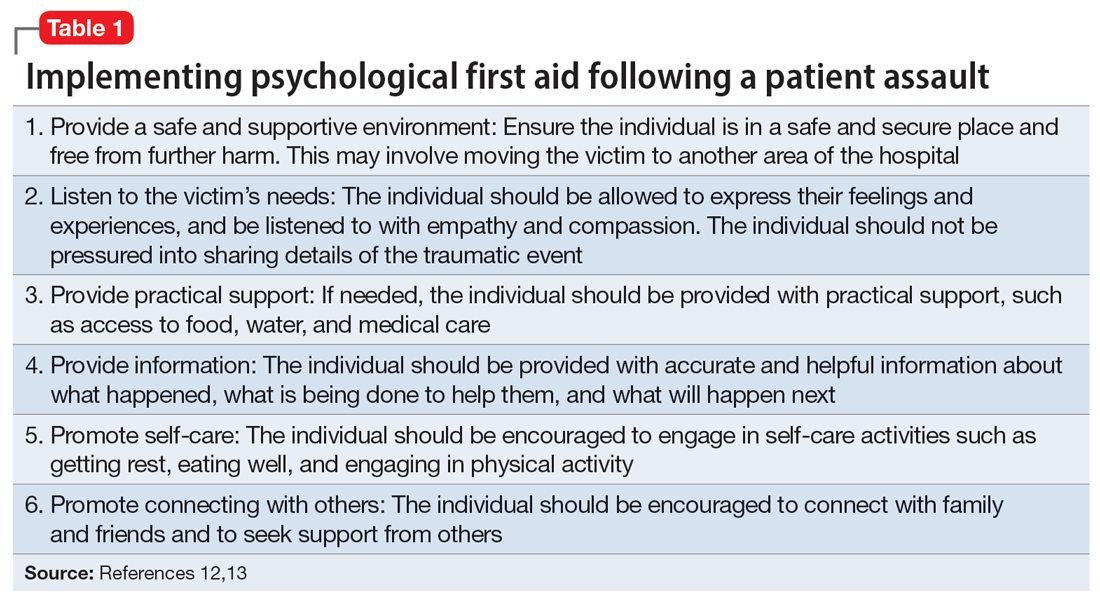

In addition to medical needs, immediate psychological support should be considered. Compulsory participation in crisis intervention stress debriefing, particularly when performed by untrained individuals, is not recommended due to questions about its demonstrated efficacy and potential to increase the risk of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in the long term.11,12 However, research has established the need for immediate support that does not necessarily involve a discussion of the traumatic event. One option is psychological first aid (PFA), an intervention supported by the World Health Organization. Originally developed for victims of mass crisis events, PFA easily translates to the hospital setting.12,13 PFA focuses on the immediate, basic needs of the victim to reduce distress and anxiety and encourage adaptive coping. Table 112,13 summarizes key components of PFA.

Continue to: PFA can be compared...