When initial therapy fails to control a patient’s panic attacks, a neuroanatomic model of anxiety disorders may help. This model proposes that panic sufferers have an abnormally sensitive brain “fear circuit.”1 It suggests why both medications and cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) are effective for treating panic disorder (PD) and can be used as a guide to more successful treatment.

This article explains the fear circuit model and describes how to determine whether initial drug treatment of panic symptoms has been adequate. It offers evidence-and experience-based dosing ranges, augmentation strategies, tips for antidepressant titration, and solutions to the most common inadequate response problems.

HOW THE FEAR CIRCUIT WORKS

Panic disorder may occur with or without agoraphobia. The diagnosis requires recurrent, unexpected panic attacks (Table 1), with at least one attack followed by 1 month or more of:

- persistent concern about having additional attacks

- worry about the implications of the attack

- or significant change in behavior related to the attack.

Panic disorder is usually accompanied by phobic avoidance and anticipatory anxiety, and it often coexists with other psychiatric disorders. Anxiety disorders may share a common genetic vulnerability. Childhood experiences, gender, and life events may increase or decrease the probability that a biologically vulnerable individual will develop an anxiety disorder or depression.1

Table 1

Panic attacks: The core symptom of panic disorder

| A panic attack is a discrete period of intense fear or discomfort, in which four (or more) of the following symptoms develop abruptly and peak within 10 minutes: |

|

| Source: DSM-IV-TR |

Fear circuit model. PD’s pathophysiology is not completely understood, but evidence suggests that an overactive brain alarm network may increase vulnerability for PD (Box).1,2 Individual patients require different intensities of treatment to normalize their panic symptoms:

Mild to moderate PD (characterized by little or no avoidance and no comorbid disorders) often responds to either medication or CBT. A single intervention—such as using CBT to enhance the cortical inhibitory effects or using medication to reduce the amygdala’s reactivity—may suffice for symptomatic relief.

Severe or complicated PD (characterized by frequent panic attacks, significant agoraphobia, and comorbid anxiety disorders or depression) may require high medication dosages, intense CBT/exposure therapy, or both to normalize more severely disrupted communication among the fear circuit’s components.

ASSESSING TREATMENT OUTCOME

The goal of treatment is remission: a return to functioning without illness-related impairment or loss of quality of life, as if the patient had never been ill. In clinical practice, we can use validated, patient-rated assessment tools to document improvement in panic-related impairment, patient satisfaction, and quality of life—the real targets of treatment. Two useful tools are the Sheehan Disability Scale3 and the Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire.4

With adequate treatment, achieving remission can take several months or more; without it, remission may never occur. The following guidelines can help ensure that you provide adequate treatment.

What is adequate CBT? When patients’ symptoms fail to respond to CBT, the first step is to examine whether inadequate treatment is the culprit. At least 10 weekly CBT sessions administered by a “qualified professional” has been suggested as an adequate CBT trial for PD.5 Unfortunately, qualified CBT therapists are not always available. If CBT referral is not an option, clinicians can provide patients with at least some elements of CBT, such as education about PD, information resources, and self-exposure instruction as indicated. For more information on CBT for PD, see Related Resources.

What is adequate drug treatment? Noncompliance with medication because a patient fears adverse effects or has insufficient information can easily thwart treatment. Before treatment begins, therefore, it is important to establish your credibility. Provide the patient with information about PD, its treatment options, and what to expect so that he or she can collaborate in treatment (Table 2).

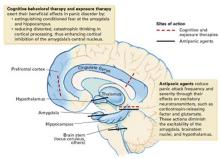

An inherited, abnormally active brain alarm mechanism—or “fear circuit”—may explain panic disorder, according to a theoretical neuroanatomic model.1 Its hub is the central nucleus of the amygdala, which coordinates fear responses via pathways communicating with the hippocampus, thalamus, hypothalamus, brainstem, and cortical processing areas.

The amygdala mediates acute emotional responses, including fear and anxiety. The hypothalamus mediates physiologic changes connected with emotions, such as release of stress hormones and some changes in heart rate. The prefrontal cortex is involved in thinking and memory and may be instrumental in predicting the consequences of rewards or punishments. In vulnerable individuals, defects in coordinating the sensory input among these brain regions may cause the central nucleus to discharge, resulting in a panic attack.

Medication and cognitive-behavioral therapy may reduce fear circuit reactivity and prevent panic attacks by acting at different components of the fear circuit. When the amygdala’s central nucleus no longer overreacts to sensory input, anticipatory anxiety and phobic avoidance usually dissipate over time.2,3 Thus, the fear circuit model integrates the clinical observation that both cognitive-behavioral therapy and medication are effective for treating panic.1

Abnormal interactions among components of this oversensitive fear circuit also may occur in social anxiety disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, and depression.1 In these disorders, communication patterns among the parts of the hypothesized circuit may be disrupted in different ways. The clinical observation that anxious individuals often become depressed when under stress is consistent with this model and with the literature.