User login

Beware of subgroup analyses in trial results

Studies often include subgroup analyses outlining how a specific treatment is more or less effective in one group of patients compared with another. But clinicians, beware: Subgroup analyses too often are not clinically meaningful and should be interpreted cautiously, Dr. Sarah R. Barton and her associates reported in a poster presentation at the American Society for Clinical Oncology’s Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium.

The investigators reviewed 145 randomized, controlled phase III trials published in peer-reviewed journals from January 2003 to January 2012 that tested an investigational therapy in GI cancer and that involved at least 150 patients. Subgroup analyses appeared in 100 studies (69%), more often in larger ones.

Here’s the shocking part: Only 25% of trials that claimed the treatment worked in a subgroup of patients had the statistical measures to back that up, reported Dr. Barton of Royal Marsden Hospital, Sutton, England. That proportion was the same for industry-sponsored and nonindustry trials.

The study, which won a Merit Award at the meeting, conducted some interesting subgroup analyses of its own. Trials sponsored by for-profit companies included a significantly higher number of subgroup analyses compared with nonindustry trials – a median of six versus two, respectively.

Trials of targeted therapies were more than three times as likely to report subgroup analyses compared with studies of cytotoxic therapies and included significantly more subgroup analyses (a median of six vs. two, respectively). Studies that reported a positive effect in the primary outcome also included a significantly higher median number of subgroup analyses compared with negative trials (again, six versus two).

Industry-sponsored trials that reported a positive effect in the primary outcome of the study were the most likely to report subgroup analyses (23 of 25 studies, or 95%) and to include the highest median number of subgroup analyses (eight) compared with industry-funded trials with a negative primary outcome or nonindustry trials, positive or negative.

Dr. Barton gave some clues that, in general, should cause physicians to look closely at efficacy claims. These include subgroup analyses conducted post hoc, when multiple tests are applied, when multiple endpoints are used, and if there’s no statistically significant test of interaction.

This is not just a problem in oncology. A previous study of 469 randomized, controlled trials published in 118 journals reported that industry-funded trials were less likely to define subgroups before starting the trial, less likely to use the interaction test for analyses of subgroup effects, and more likely to report on subgroups if the primary outcome in the study did not show a positive result (BMJ 2011;342:d1569)

The New England Journal of Medicine provides similar cautions in its guidelines for investigators reporting on subgroup analyses (N. Engl. J. Med. 2007;357:2189-2194).

Dr. Barton reported having no financial disclosures.

– Sherry Boschert

On Twitter @sherryboschert

Studies often include subgroup analyses outlining how a specific treatment is more or less effective in one group of patients compared with another. But clinicians, beware: Subgroup analyses too often are not clinically meaningful and should be interpreted cautiously, Dr. Sarah R. Barton and her associates reported in a poster presentation at the American Society for Clinical Oncology’s Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium.

The investigators reviewed 145 randomized, controlled phase III trials published in peer-reviewed journals from January 2003 to January 2012 that tested an investigational therapy in GI cancer and that involved at least 150 patients. Subgroup analyses appeared in 100 studies (69%), more often in larger ones.

Here’s the shocking part: Only 25% of trials that claimed the treatment worked in a subgroup of patients had the statistical measures to back that up, reported Dr. Barton of Royal Marsden Hospital, Sutton, England. That proportion was the same for industry-sponsored and nonindustry trials.

The study, which won a Merit Award at the meeting, conducted some interesting subgroup analyses of its own. Trials sponsored by for-profit companies included a significantly higher number of subgroup analyses compared with nonindustry trials – a median of six versus two, respectively.

Trials of targeted therapies were more than three times as likely to report subgroup analyses compared with studies of cytotoxic therapies and included significantly more subgroup analyses (a median of six vs. two, respectively). Studies that reported a positive effect in the primary outcome also included a significantly higher median number of subgroup analyses compared with negative trials (again, six versus two).

Industry-sponsored trials that reported a positive effect in the primary outcome of the study were the most likely to report subgroup analyses (23 of 25 studies, or 95%) and to include the highest median number of subgroup analyses (eight) compared with industry-funded trials with a negative primary outcome or nonindustry trials, positive or negative.

Dr. Barton gave some clues that, in general, should cause physicians to look closely at efficacy claims. These include subgroup analyses conducted post hoc, when multiple tests are applied, when multiple endpoints are used, and if there’s no statistically significant test of interaction.

This is not just a problem in oncology. A previous study of 469 randomized, controlled trials published in 118 journals reported that industry-funded trials were less likely to define subgroups before starting the trial, less likely to use the interaction test for analyses of subgroup effects, and more likely to report on subgroups if the primary outcome in the study did not show a positive result (BMJ 2011;342:d1569)

The New England Journal of Medicine provides similar cautions in its guidelines for investigators reporting on subgroup analyses (N. Engl. J. Med. 2007;357:2189-2194).

Dr. Barton reported having no financial disclosures.

– Sherry Boschert

On Twitter @sherryboschert

Studies often include subgroup analyses outlining how a specific treatment is more or less effective in one group of patients compared with another. But clinicians, beware: Subgroup analyses too often are not clinically meaningful and should be interpreted cautiously, Dr. Sarah R. Barton and her associates reported in a poster presentation at the American Society for Clinical Oncology’s Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium.

The investigators reviewed 145 randomized, controlled phase III trials published in peer-reviewed journals from January 2003 to January 2012 that tested an investigational therapy in GI cancer and that involved at least 150 patients. Subgroup analyses appeared in 100 studies (69%), more often in larger ones.

Here’s the shocking part: Only 25% of trials that claimed the treatment worked in a subgroup of patients had the statistical measures to back that up, reported Dr. Barton of Royal Marsden Hospital, Sutton, England. That proportion was the same for industry-sponsored and nonindustry trials.

The study, which won a Merit Award at the meeting, conducted some interesting subgroup analyses of its own. Trials sponsored by for-profit companies included a significantly higher number of subgroup analyses compared with nonindustry trials – a median of six versus two, respectively.

Trials of targeted therapies were more than three times as likely to report subgroup analyses compared with studies of cytotoxic therapies and included significantly more subgroup analyses (a median of six vs. two, respectively). Studies that reported a positive effect in the primary outcome also included a significantly higher median number of subgroup analyses compared with negative trials (again, six versus two).

Industry-sponsored trials that reported a positive effect in the primary outcome of the study were the most likely to report subgroup analyses (23 of 25 studies, or 95%) and to include the highest median number of subgroup analyses (eight) compared with industry-funded trials with a negative primary outcome or nonindustry trials, positive or negative.

Dr. Barton gave some clues that, in general, should cause physicians to look closely at efficacy claims. These include subgroup analyses conducted post hoc, when multiple tests are applied, when multiple endpoints are used, and if there’s no statistically significant test of interaction.

This is not just a problem in oncology. A previous study of 469 randomized, controlled trials published in 118 journals reported that industry-funded trials were less likely to define subgroups before starting the trial, less likely to use the interaction test for analyses of subgroup effects, and more likely to report on subgroups if the primary outcome in the study did not show a positive result (BMJ 2011;342:d1569)

The New England Journal of Medicine provides similar cautions in its guidelines for investigators reporting on subgroup analyses (N. Engl. J. Med. 2007;357:2189-2194).

Dr. Barton reported having no financial disclosures.

– Sherry Boschert

On Twitter @sherryboschert

Evidence-based medicine depends on quality evidence

Efforts to improve the quality of health care often emphasize evidence-based medicine, but flaws in how research is designed, conducted, and reported make this "a great time for skeptics, in looking at clinical trials," according to Dr. J. Russell Hoverman.

Multiple studies in recent years suggest that increasing influence from industry and researchers’ desire to emphasize positive results, as well as other factors, may be distorting choices about which studies get done and how they get reported, said Dr. Hoverman, a medical oncologist and hematologist at Texas Oncology in Austin, Tex.

If researchers don’t improve the way they conduct and assess clinical trials, a lot of money could be wasted on misguided research, he said at a quality care symposium sponsored by the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

He’s not the only one making the case. Physicians at Yale recently argued for greater transparency in pharmaceutical industry–sponsored research to improve the integrity of medical research (Am. J. Public Health 2012;102:72-80).

Over the last three decades, sponsorship of breast, colon, and lung cancer studies by for-profit companies increased from 4% to 57%, Dr. Hoverman noted. Industry sponsorship was associated with trial results that endorsed the experimental agent, according to one study (J. Clin. Oncol. 2008;26:5458-64).

A separate study showed that abstracts of study results presented at major oncology meetings before final publication were discordant from the published article 63% of the time. In 10% of cases, the abstract and article presented substantially different conclusions (J. Clin. Oncol. 2009;3938-44).

One example of this was a trial of a cancer treatment regimen using gemcitabine, cisplatin, and bevacizumab. The investigators initially released an early abstract reporting an improvement in progression-free survival using the regimen. "That actually changed some [oncologists’] practices," he noted. But that was before the study reached its main outcome measure – overall survival – which, in the end, did not improve significantly with the new regimen.

Only half of phase II clinical trials with positive findings lead to positive phase III trials, another study found. For some reason, industry-sponsored trials are much more likely to report positive findings, compared with all other trials – 90% and 45%, respectively (J. Clin. Oncol. 2008;26:1511-8).

When reading or interpreting abstract summaries from a medical conference, "one needs to be a little careful," Dr. Hoverman advised.

Yet another study found that only 45% of randomized clinical trials were registered, even though trial registration has been required since 2005 by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors in order for the results to be published in participating journals.

Among the registered studies, 31% showed discrepancies between what the investigators said they would be studying and the published outcomes. Half of the studies with discrepancies could be assessed to try to figure out why this was so; of those, 83% of the time it appeared that the investigators decided to favor statistically significant findings in the published article (JAMA 2009;302:977-84).

One set of experts from within industry and from Johns Hopkins University called for "transformational change" in how randomized clinical trials are conducted (Ann. Intern. Med. 2009;151:206-209).

"Without major changes in how we conceive, design, conduct, and analyze randomized controlled trials, the nation risks spending large sums of money inefficiently to answer the wrong questions, or the right questions too late," Dr. Hoverman said.

"In fact, we probably can’t do randomized clinical trials on everything we want to know about. It’s simply impossible. There’s not enough money, and many things involve competing industries or competing members within an industry," making it unlikely that some head-to-head comparisons will ever be done, he added. "So, we are challenged to make decisions based on evidence."

The broader challenge for clinicians and researchers will be to improve the quality and integrity of medical studies while maintaining a healthy skepticism about the available evidence. Medicine has always been an art and a science. Where the science behind medicine is lacking, the art takes over.

Dr. Hoverman reported having no financial disclosures.

-- Sherry Boschert

On Twitter @sherryboschert

Efforts to improve the quality of health care often emphasize evidence-based medicine, but flaws in how research is designed, conducted, and reported make this "a great time for skeptics, in looking at clinical trials," according to Dr. J. Russell Hoverman.

Multiple studies in recent years suggest that increasing influence from industry and researchers’ desire to emphasize positive results, as well as other factors, may be distorting choices about which studies get done and how they get reported, said Dr. Hoverman, a medical oncologist and hematologist at Texas Oncology in Austin, Tex.

If researchers don’t improve the way they conduct and assess clinical trials, a lot of money could be wasted on misguided research, he said at a quality care symposium sponsored by the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

He’s not the only one making the case. Physicians at Yale recently argued for greater transparency in pharmaceutical industry–sponsored research to improve the integrity of medical research (Am. J. Public Health 2012;102:72-80).

Over the last three decades, sponsorship of breast, colon, and lung cancer studies by for-profit companies increased from 4% to 57%, Dr. Hoverman noted. Industry sponsorship was associated with trial results that endorsed the experimental agent, according to one study (J. Clin. Oncol. 2008;26:5458-64).

A separate study showed that abstracts of study results presented at major oncology meetings before final publication were discordant from the published article 63% of the time. In 10% of cases, the abstract and article presented substantially different conclusions (J. Clin. Oncol. 2009;3938-44).

One example of this was a trial of a cancer treatment regimen using gemcitabine, cisplatin, and bevacizumab. The investigators initially released an early abstract reporting an improvement in progression-free survival using the regimen. "That actually changed some [oncologists’] practices," he noted. But that was before the study reached its main outcome measure – overall survival – which, in the end, did not improve significantly with the new regimen.

Only half of phase II clinical trials with positive findings lead to positive phase III trials, another study found. For some reason, industry-sponsored trials are much more likely to report positive findings, compared with all other trials – 90% and 45%, respectively (J. Clin. Oncol. 2008;26:1511-8).

When reading or interpreting abstract summaries from a medical conference, "one needs to be a little careful," Dr. Hoverman advised.

Yet another study found that only 45% of randomized clinical trials were registered, even though trial registration has been required since 2005 by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors in order for the results to be published in participating journals.

Among the registered studies, 31% showed discrepancies between what the investigators said they would be studying and the published outcomes. Half of the studies with discrepancies could be assessed to try to figure out why this was so; of those, 83% of the time it appeared that the investigators decided to favor statistically significant findings in the published article (JAMA 2009;302:977-84).

One set of experts from within industry and from Johns Hopkins University called for "transformational change" in how randomized clinical trials are conducted (Ann. Intern. Med. 2009;151:206-209).

"Without major changes in how we conceive, design, conduct, and analyze randomized controlled trials, the nation risks spending large sums of money inefficiently to answer the wrong questions, or the right questions too late," Dr. Hoverman said.

"In fact, we probably can’t do randomized clinical trials on everything we want to know about. It’s simply impossible. There’s not enough money, and many things involve competing industries or competing members within an industry," making it unlikely that some head-to-head comparisons will ever be done, he added. "So, we are challenged to make decisions based on evidence."

The broader challenge for clinicians and researchers will be to improve the quality and integrity of medical studies while maintaining a healthy skepticism about the available evidence. Medicine has always been an art and a science. Where the science behind medicine is lacking, the art takes over.

Dr. Hoverman reported having no financial disclosures.

-- Sherry Boschert

On Twitter @sherryboschert

Efforts to improve the quality of health care often emphasize evidence-based medicine, but flaws in how research is designed, conducted, and reported make this "a great time for skeptics, in looking at clinical trials," according to Dr. J. Russell Hoverman.

Multiple studies in recent years suggest that increasing influence from industry and researchers’ desire to emphasize positive results, as well as other factors, may be distorting choices about which studies get done and how they get reported, said Dr. Hoverman, a medical oncologist and hematologist at Texas Oncology in Austin, Tex.

If researchers don’t improve the way they conduct and assess clinical trials, a lot of money could be wasted on misguided research, he said at a quality care symposium sponsored by the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

He’s not the only one making the case. Physicians at Yale recently argued for greater transparency in pharmaceutical industry–sponsored research to improve the integrity of medical research (Am. J. Public Health 2012;102:72-80).

Over the last three decades, sponsorship of breast, colon, and lung cancer studies by for-profit companies increased from 4% to 57%, Dr. Hoverman noted. Industry sponsorship was associated with trial results that endorsed the experimental agent, according to one study (J. Clin. Oncol. 2008;26:5458-64).

A separate study showed that abstracts of study results presented at major oncology meetings before final publication were discordant from the published article 63% of the time. In 10% of cases, the abstract and article presented substantially different conclusions (J. Clin. Oncol. 2009;3938-44).

One example of this was a trial of a cancer treatment regimen using gemcitabine, cisplatin, and bevacizumab. The investigators initially released an early abstract reporting an improvement in progression-free survival using the regimen. "That actually changed some [oncologists’] practices," he noted. But that was before the study reached its main outcome measure – overall survival – which, in the end, did not improve significantly with the new regimen.

Only half of phase II clinical trials with positive findings lead to positive phase III trials, another study found. For some reason, industry-sponsored trials are much more likely to report positive findings, compared with all other trials – 90% and 45%, respectively (J. Clin. Oncol. 2008;26:1511-8).

When reading or interpreting abstract summaries from a medical conference, "one needs to be a little careful," Dr. Hoverman advised.

Yet another study found that only 45% of randomized clinical trials were registered, even though trial registration has been required since 2005 by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors in order for the results to be published in participating journals.

Among the registered studies, 31% showed discrepancies between what the investigators said they would be studying and the published outcomes. Half of the studies with discrepancies could be assessed to try to figure out why this was so; of those, 83% of the time it appeared that the investigators decided to favor statistically significant findings in the published article (JAMA 2009;302:977-84).

One set of experts from within industry and from Johns Hopkins University called for "transformational change" in how randomized clinical trials are conducted (Ann. Intern. Med. 2009;151:206-209).

"Without major changes in how we conceive, design, conduct, and analyze randomized controlled trials, the nation risks spending large sums of money inefficiently to answer the wrong questions, or the right questions too late," Dr. Hoverman said.

"In fact, we probably can’t do randomized clinical trials on everything we want to know about. It’s simply impossible. There’s not enough money, and many things involve competing industries or competing members within an industry," making it unlikely that some head-to-head comparisons will ever be done, he added. "So, we are challenged to make decisions based on evidence."

The broader challenge for clinicians and researchers will be to improve the quality and integrity of medical studies while maintaining a healthy skepticism about the available evidence. Medicine has always been an art and a science. Where the science behind medicine is lacking, the art takes over.

Dr. Hoverman reported having no financial disclosures.

-- Sherry Boschert

On Twitter @sherryboschert

The Paralympics and Prosthesis Pride

South African runner Oscar Pistorius fell just short of winning a medal at the London 2012 Olympics, but the double amputee did show the world that people with disabilities can achieve greatness in sports. His specially made prosthetic limbs also reflect a growing trend – highly visible in the media among returning soldiers from Afghanistan and Iraq – toward more people with amputations displaying their prostheses rather than hiding them with coverings that resemble arms and legs.

The trend will be further highlighted at the 2012 Paralympic Games, taking place in London Aug. 29 through Sept. 9, and where Mr. Pistorius will again compete.

"These are not your grandparents’ prosthetic devices that are available today. They have advanced at such a rapid pace. It’s not only exciting for users of prosthetic devices, but nonamputees are also very interested in the technology – how far it has evolved, and what prosthetic users are capable of doing, whether it be climbing Mount Everest or running in the Olympics with prosthetic limbs," according to Kevin Carroll, vice president of prosthetics at Hanger Orthopedic Group, based in Austin, Tex.*

About 4,200 athletes from 165 countries will compete in the Paralympics, across 503 medal events. Athletes with amputations will be some of the most visually distinct among the Paralympics’ 10 categories of disability: impaired muscle power, impaired passive range of motion, limb deficiency, leg length difference, short stature, hypertonia, ataxia, athetosis, vision impairment, and intellectual impairment.

"This year, we’re expecting all sorts of records at the Paralympics. There is a greater focus worldwide and countries throughout the world are seeing the importance of supporting athletes in Paralympic events ... I predict many more Pistorius-types are on their way to the Olympics," said Mr. Carroll.

In the Paralympics, athletes using specially designed prosthetic devices –that is, used specifically for the sport and not for everyday use – will be most visible in track and field events. Prosthetic devices are not used in sports such as swimming and sitting volleyball. However, athletes with amputations are using prostheses for a wide range of sports in the real world.

"We are now supplying sport-specific prostheses from early ages all the way up to adults. This includes everything from prostheses made specifically for running, cycling, swimming, mountain climbing, snowboarding, skiing, and more," Mr. Carroll said.

In fact, the emerging technology is so good that some have suggested it may soon allow disabled athletes to outdo their able-bodied counterparts.

Of course, most amputees are not elite athletes. There are approximately 1.7 million people with limb loss in the United States, with another 150,000 who undergo amputations each year. While injured soldiers tend to be the most visible amputees in the media, diabetes is by far the greatest cause of limb loss – more than 80% of all amputations are the result of diabetes. Vascular disease, trauma, and cancer are among the other top causes.

But even increasing numbers of non–athlete amputees have been showcasing their prostheses within the last 10-15 years, with comparable numbers in both the civilian and military populations. As many as 50% of amputees in the United States now choose to display their prostheses, compared with less than 10% among their European counterparts. "This number wasn’t as high in the U.S. 30 years ago. This has evolved over time," Mr. Carroll said.

A realistic-looking limb cover adds to the cost of the working part of the prosthesis itself, but he believes that’s not why we’re seeing more of the latter. "[Amputees who chose to show their prostheses] like to showcase the technology they’re walking around on. This shows they have really accepted their loss. They are not showcasing their prostheses because of the cost, they’re doing it because of pride."

His advice to physicians: "Never say never to patients. We see people who are confined to wheelchairs get up and walk every day. We’re in a whole new era of rehabilitation. We’re very excited about the future."

–Miriam E. Tucker (@MiriamETucker on Twitter)

*CORRECTION 8/30/12: The original sentence misstated the location of Hanger Orthopedic Group. The sentence should have read: "These are not your grandparents’ prosthetic devices that are available today. They have advanced at such a rapid pace. It’s not only exciting for users of prosthetic devices, but nonamputees are also very interested in the technology – how far it has evolved, and what prosthetic users are capable of doing, whether it be climbing Mount Everest or running in the Olympics with prosthetic limbs," according to Kevin Carroll, vice president of prosthetics at Hanger Orthopedic Group, based in Austin, Tex..

South African runner Oscar Pistorius fell just short of winning a medal at the London 2012 Olympics, but the double amputee did show the world that people with disabilities can achieve greatness in sports. His specially made prosthetic limbs also reflect a growing trend – highly visible in the media among returning soldiers from Afghanistan and Iraq – toward more people with amputations displaying their prostheses rather than hiding them with coverings that resemble arms and legs.

The trend will be further highlighted at the 2012 Paralympic Games, taking place in London Aug. 29 through Sept. 9, and where Mr. Pistorius will again compete.

"These are not your grandparents’ prosthetic devices that are available today. They have advanced at such a rapid pace. It’s not only exciting for users of prosthetic devices, but nonamputees are also very interested in the technology – how far it has evolved, and what prosthetic users are capable of doing, whether it be climbing Mount Everest or running in the Olympics with prosthetic limbs," according to Kevin Carroll, vice president of prosthetics at Hanger Orthopedic Group, based in Austin, Tex.*

About 4,200 athletes from 165 countries will compete in the Paralympics, across 503 medal events. Athletes with amputations will be some of the most visually distinct among the Paralympics’ 10 categories of disability: impaired muscle power, impaired passive range of motion, limb deficiency, leg length difference, short stature, hypertonia, ataxia, athetosis, vision impairment, and intellectual impairment.

"This year, we’re expecting all sorts of records at the Paralympics. There is a greater focus worldwide and countries throughout the world are seeing the importance of supporting athletes in Paralympic events ... I predict many more Pistorius-types are on their way to the Olympics," said Mr. Carroll.

In the Paralympics, athletes using specially designed prosthetic devices –that is, used specifically for the sport and not for everyday use – will be most visible in track and field events. Prosthetic devices are not used in sports such as swimming and sitting volleyball. However, athletes with amputations are using prostheses for a wide range of sports in the real world.

"We are now supplying sport-specific prostheses from early ages all the way up to adults. This includes everything from prostheses made specifically for running, cycling, swimming, mountain climbing, snowboarding, skiing, and more," Mr. Carroll said.

In fact, the emerging technology is so good that some have suggested it may soon allow disabled athletes to outdo their able-bodied counterparts.

Of course, most amputees are not elite athletes. There are approximately 1.7 million people with limb loss in the United States, with another 150,000 who undergo amputations each year. While injured soldiers tend to be the most visible amputees in the media, diabetes is by far the greatest cause of limb loss – more than 80% of all amputations are the result of diabetes. Vascular disease, trauma, and cancer are among the other top causes.

But even increasing numbers of non–athlete amputees have been showcasing their prostheses within the last 10-15 years, with comparable numbers in both the civilian and military populations. As many as 50% of amputees in the United States now choose to display their prostheses, compared with less than 10% among their European counterparts. "This number wasn’t as high in the U.S. 30 years ago. This has evolved over time," Mr. Carroll said.

A realistic-looking limb cover adds to the cost of the working part of the prosthesis itself, but he believes that’s not why we’re seeing more of the latter. "[Amputees who chose to show their prostheses] like to showcase the technology they’re walking around on. This shows they have really accepted their loss. They are not showcasing their prostheses because of the cost, they’re doing it because of pride."

His advice to physicians: "Never say never to patients. We see people who are confined to wheelchairs get up and walk every day. We’re in a whole new era of rehabilitation. We’re very excited about the future."

–Miriam E. Tucker (@MiriamETucker on Twitter)

*CORRECTION 8/30/12: The original sentence misstated the location of Hanger Orthopedic Group. The sentence should have read: "These are not your grandparents’ prosthetic devices that are available today. They have advanced at such a rapid pace. It’s not only exciting for users of prosthetic devices, but nonamputees are also very interested in the technology – how far it has evolved, and what prosthetic users are capable of doing, whether it be climbing Mount Everest or running in the Olympics with prosthetic limbs," according to Kevin Carroll, vice president of prosthetics at Hanger Orthopedic Group, based in Austin, Tex..

South African runner Oscar Pistorius fell just short of winning a medal at the London 2012 Olympics, but the double amputee did show the world that people with disabilities can achieve greatness in sports. His specially made prosthetic limbs also reflect a growing trend – highly visible in the media among returning soldiers from Afghanistan and Iraq – toward more people with amputations displaying their prostheses rather than hiding them with coverings that resemble arms and legs.

The trend will be further highlighted at the 2012 Paralympic Games, taking place in London Aug. 29 through Sept. 9, and where Mr. Pistorius will again compete.

"These are not your grandparents’ prosthetic devices that are available today. They have advanced at such a rapid pace. It’s not only exciting for users of prosthetic devices, but nonamputees are also very interested in the technology – how far it has evolved, and what prosthetic users are capable of doing, whether it be climbing Mount Everest or running in the Olympics with prosthetic limbs," according to Kevin Carroll, vice president of prosthetics at Hanger Orthopedic Group, based in Austin, Tex.*

About 4,200 athletes from 165 countries will compete in the Paralympics, across 503 medal events. Athletes with amputations will be some of the most visually distinct among the Paralympics’ 10 categories of disability: impaired muscle power, impaired passive range of motion, limb deficiency, leg length difference, short stature, hypertonia, ataxia, athetosis, vision impairment, and intellectual impairment.

"This year, we’re expecting all sorts of records at the Paralympics. There is a greater focus worldwide and countries throughout the world are seeing the importance of supporting athletes in Paralympic events ... I predict many more Pistorius-types are on their way to the Olympics," said Mr. Carroll.

In the Paralympics, athletes using specially designed prosthetic devices –that is, used specifically for the sport and not for everyday use – will be most visible in track and field events. Prosthetic devices are not used in sports such as swimming and sitting volleyball. However, athletes with amputations are using prostheses for a wide range of sports in the real world.

"We are now supplying sport-specific prostheses from early ages all the way up to adults. This includes everything from prostheses made specifically for running, cycling, swimming, mountain climbing, snowboarding, skiing, and more," Mr. Carroll said.

In fact, the emerging technology is so good that some have suggested it may soon allow disabled athletes to outdo their able-bodied counterparts.

Of course, most amputees are not elite athletes. There are approximately 1.7 million people with limb loss in the United States, with another 150,000 who undergo amputations each year. While injured soldiers tend to be the most visible amputees in the media, diabetes is by far the greatest cause of limb loss – more than 80% of all amputations are the result of diabetes. Vascular disease, trauma, and cancer are among the other top causes.

But even increasing numbers of non–athlete amputees have been showcasing their prostheses within the last 10-15 years, with comparable numbers in both the civilian and military populations. As many as 50% of amputees in the United States now choose to display their prostheses, compared with less than 10% among their European counterparts. "This number wasn’t as high in the U.S. 30 years ago. This has evolved over time," Mr. Carroll said.

A realistic-looking limb cover adds to the cost of the working part of the prosthesis itself, but he believes that’s not why we’re seeing more of the latter. "[Amputees who chose to show their prostheses] like to showcase the technology they’re walking around on. This shows they have really accepted their loss. They are not showcasing their prostheses because of the cost, they’re doing it because of pride."

His advice to physicians: "Never say never to patients. We see people who are confined to wheelchairs get up and walk every day. We’re in a whole new era of rehabilitation. We’re very excited about the future."

–Miriam E. Tucker (@MiriamETucker on Twitter)

*CORRECTION 8/30/12: The original sentence misstated the location of Hanger Orthopedic Group. The sentence should have read: "These are not your grandparents’ prosthetic devices that are available today. They have advanced at such a rapid pace. It’s not only exciting for users of prosthetic devices, but nonamputees are also very interested in the technology – how far it has evolved, and what prosthetic users are capable of doing, whether it be climbing Mount Everest or running in the Olympics with prosthetic limbs," according to Kevin Carroll, vice president of prosthetics at Hanger Orthopedic Group, based in Austin, Tex..

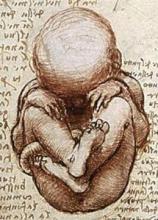

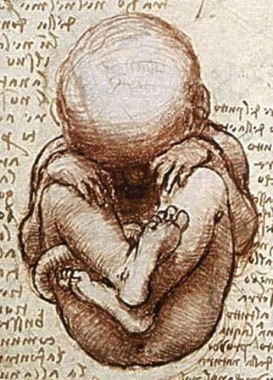

Fetal Spina Bifida Surgery: Balancing Access and Outcomes

Most medical decisions come down to weighing risks and benefits, and trying to ensure that the balance falls to the good.

About 18 months ago, the diminutive medical and surgical niche that’s fetal surgery (fewer than 1,000 U.S. fetal surgical procedures are done annually) came out with the blockbuster finding that fetal surgery to repair myelomeningoceles and blunt the complications of spina bifida was relatively safe and produced substantial benefits, compared with more conventional treatments that affected infants and children undergo when treatment starts after birth.

To help ensure an adequate number of cases in MOMS (Management of Myelomeningocele Study) to produce a meaningful result in a reasonable amount of time, the couple of dozen or so U.S. medical centers that offer fetal surgery agreed to limit fetal-myelomeningocele repair to three U.S. locations: the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP); Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tenn.; and the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF). Even when all U.S. cases were funneled into these three sites during 8 years, the study enrolled all of 183 cases. The landmark 2011 report on outcomes in MOMS 1 year following birth had data on the first 158 cases (78 fetuses that underwent in utero myelomeningocele repair and 80 control pregnancies for which interventions occurred after birth).

The fetal-myelomeningocele repair world quickly began to change once the New England Journal paper came out in March 2011. The surgery was no longer investigational, and other U.S. centers could get into the act, if they wanted, and if they dared.

During the nearly 18 months since then, about five new programs jumped into the myelomeningocele-repair pool. That number is a little uncertain because no one keeps "official" tabs on who does the surgery, nor is there any official tally of how many fetal repairs are done, or their results. What is clear is that in the 18 months since the MOMS report, roughly 100 fetal myelomeningocele repairs were done in the United States, more than during 8 years of MOMS from February 2003 through the end of 2010.

And, at least as of now, no information is on record for how those 100 or so most recent cases have fared, including the outcomes from the new programs. That’s largely because it takes at least a year following delivery of a repaired fetus to have outcome results with follow-up similar to MOMS, and if you do the math, that means the outcomes from even the first post-MOMS cases are just now trickling in.

The risk-benefit balance at work here is this: Can new centers offer fetal myelomeningocele repairs – an understandably challenging technical undertaking – to boost access to mothers and their affected fetuses, while at the same time ensuring that their outcomes are at least as good as what happened in MOMS? It’s a question that’s not yet been answered.

It’s also a question that so troubled officials at the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development – the U.S. agency that funded MOMS – that soon after the MOMS result came out, the institute took the unusual step of organizing a panel of experts to come up with guidelines on what a program should have in place if it wanted to venture into the fetal-myelomeningocele repair business. Those recommendations are still in process and are expected out before the end of this year. A preview was offered in June by some UCSF clinicians, but I’ve been told that their summary of the pending guidelines is not completely up to date.

The wider-access issue is very real. I spoke about it with Dr. Foong-Yen Lim, surgical director of the fetal care center at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, one of the newbie programs that began offering this fetal surgery post MOMS, and that as of mid-August had done 10 cases. Having fetal-myelomeningocele repair available at more U.S. sites is important because during MOMS, when only three sites were available, he knew of cases in which the parents of affected fetuses opted not to go out of town for fetal repair because they could not afford it or could not deal with the relocation. Of course, some patients also might have not wanted to commit to being part a study knowing that once in, they had a 50-50 chance of randomization to standard care.

Dr. Lim told me how deeply he felt the responsibility he and his associates took on when they decided to start offering fetal-myelomeningocele repair and thereby boost access for affected families in the Cincinnati area. "People who take on this procedure need to ask themselves ‘Are we doing as good a job as the other places?’ " he said. He also told me that Cincinnati Children’s counselors make it clear to prospective families that if they prefer, they could travel to CHOP, Vanderbilt, or UCSF, the U.S. sites with the most experience and best-documented track records.

It’s all a balance of risk and benefit.

–Mitchel L. Zoler (on Twitter @mitchelzoler)

Most medical decisions come down to weighing risks and benefits, and trying to ensure that the balance falls to the good.

About 18 months ago, the diminutive medical and surgical niche that’s fetal surgery (fewer than 1,000 U.S. fetal surgical procedures are done annually) came out with the blockbuster finding that fetal surgery to repair myelomeningoceles and blunt the complications of spina bifida was relatively safe and produced substantial benefits, compared with more conventional treatments that affected infants and children undergo when treatment starts after birth.

To help ensure an adequate number of cases in MOMS (Management of Myelomeningocele Study) to produce a meaningful result in a reasonable amount of time, the couple of dozen or so U.S. medical centers that offer fetal surgery agreed to limit fetal-myelomeningocele repair to three U.S. locations: the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP); Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tenn.; and the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF). Even when all U.S. cases were funneled into these three sites during 8 years, the study enrolled all of 183 cases. The landmark 2011 report on outcomes in MOMS 1 year following birth had data on the first 158 cases (78 fetuses that underwent in utero myelomeningocele repair and 80 control pregnancies for which interventions occurred after birth).

The fetal-myelomeningocele repair world quickly began to change once the New England Journal paper came out in March 2011. The surgery was no longer investigational, and other U.S. centers could get into the act, if they wanted, and if they dared.

During the nearly 18 months since then, about five new programs jumped into the myelomeningocele-repair pool. That number is a little uncertain because no one keeps "official" tabs on who does the surgery, nor is there any official tally of how many fetal repairs are done, or their results. What is clear is that in the 18 months since the MOMS report, roughly 100 fetal myelomeningocele repairs were done in the United States, more than during 8 years of MOMS from February 2003 through the end of 2010.

And, at least as of now, no information is on record for how those 100 or so most recent cases have fared, including the outcomes from the new programs. That’s largely because it takes at least a year following delivery of a repaired fetus to have outcome results with follow-up similar to MOMS, and if you do the math, that means the outcomes from even the first post-MOMS cases are just now trickling in.

The risk-benefit balance at work here is this: Can new centers offer fetal myelomeningocele repairs – an understandably challenging technical undertaking – to boost access to mothers and their affected fetuses, while at the same time ensuring that their outcomes are at least as good as what happened in MOMS? It’s a question that’s not yet been answered.

It’s also a question that so troubled officials at the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development – the U.S. agency that funded MOMS – that soon after the MOMS result came out, the institute took the unusual step of organizing a panel of experts to come up with guidelines on what a program should have in place if it wanted to venture into the fetal-myelomeningocele repair business. Those recommendations are still in process and are expected out before the end of this year. A preview was offered in June by some UCSF clinicians, but I’ve been told that their summary of the pending guidelines is not completely up to date.

The wider-access issue is very real. I spoke about it with Dr. Foong-Yen Lim, surgical director of the fetal care center at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, one of the newbie programs that began offering this fetal surgery post MOMS, and that as of mid-August had done 10 cases. Having fetal-myelomeningocele repair available at more U.S. sites is important because during MOMS, when only three sites were available, he knew of cases in which the parents of affected fetuses opted not to go out of town for fetal repair because they could not afford it or could not deal with the relocation. Of course, some patients also might have not wanted to commit to being part a study knowing that once in, they had a 50-50 chance of randomization to standard care.

Dr. Lim told me how deeply he felt the responsibility he and his associates took on when they decided to start offering fetal-myelomeningocele repair and thereby boost access for affected families in the Cincinnati area. "People who take on this procedure need to ask themselves ‘Are we doing as good a job as the other places?’ " he said. He also told me that Cincinnati Children’s counselors make it clear to prospective families that if they prefer, they could travel to CHOP, Vanderbilt, or UCSF, the U.S. sites with the most experience and best-documented track records.

It’s all a balance of risk and benefit.

–Mitchel L. Zoler (on Twitter @mitchelzoler)

Most medical decisions come down to weighing risks and benefits, and trying to ensure that the balance falls to the good.

About 18 months ago, the diminutive medical and surgical niche that’s fetal surgery (fewer than 1,000 U.S. fetal surgical procedures are done annually) came out with the blockbuster finding that fetal surgery to repair myelomeningoceles and blunt the complications of spina bifida was relatively safe and produced substantial benefits, compared with more conventional treatments that affected infants and children undergo when treatment starts after birth.

To help ensure an adequate number of cases in MOMS (Management of Myelomeningocele Study) to produce a meaningful result in a reasonable amount of time, the couple of dozen or so U.S. medical centers that offer fetal surgery agreed to limit fetal-myelomeningocele repair to three U.S. locations: the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP); Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tenn.; and the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF). Even when all U.S. cases were funneled into these three sites during 8 years, the study enrolled all of 183 cases. The landmark 2011 report on outcomes in MOMS 1 year following birth had data on the first 158 cases (78 fetuses that underwent in utero myelomeningocele repair and 80 control pregnancies for which interventions occurred after birth).

The fetal-myelomeningocele repair world quickly began to change once the New England Journal paper came out in March 2011. The surgery was no longer investigational, and other U.S. centers could get into the act, if they wanted, and if they dared.

During the nearly 18 months since then, about five new programs jumped into the myelomeningocele-repair pool. That number is a little uncertain because no one keeps "official" tabs on who does the surgery, nor is there any official tally of how many fetal repairs are done, or their results. What is clear is that in the 18 months since the MOMS report, roughly 100 fetal myelomeningocele repairs were done in the United States, more than during 8 years of MOMS from February 2003 through the end of 2010.

And, at least as of now, no information is on record for how those 100 or so most recent cases have fared, including the outcomes from the new programs. That’s largely because it takes at least a year following delivery of a repaired fetus to have outcome results with follow-up similar to MOMS, and if you do the math, that means the outcomes from even the first post-MOMS cases are just now trickling in.

The risk-benefit balance at work here is this: Can new centers offer fetal myelomeningocele repairs – an understandably challenging technical undertaking – to boost access to mothers and their affected fetuses, while at the same time ensuring that their outcomes are at least as good as what happened in MOMS? It’s a question that’s not yet been answered.

It’s also a question that so troubled officials at the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development – the U.S. agency that funded MOMS – that soon after the MOMS result came out, the institute took the unusual step of organizing a panel of experts to come up with guidelines on what a program should have in place if it wanted to venture into the fetal-myelomeningocele repair business. Those recommendations are still in process and are expected out before the end of this year. A preview was offered in June by some UCSF clinicians, but I’ve been told that their summary of the pending guidelines is not completely up to date.

The wider-access issue is very real. I spoke about it with Dr. Foong-Yen Lim, surgical director of the fetal care center at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, one of the newbie programs that began offering this fetal surgery post MOMS, and that as of mid-August had done 10 cases. Having fetal-myelomeningocele repair available at more U.S. sites is important because during MOMS, when only three sites were available, he knew of cases in which the parents of affected fetuses opted not to go out of town for fetal repair because they could not afford it or could not deal with the relocation. Of course, some patients also might have not wanted to commit to being part a study knowing that once in, they had a 50-50 chance of randomization to standard care.

Dr. Lim told me how deeply he felt the responsibility he and his associates took on when they decided to start offering fetal-myelomeningocele repair and thereby boost access for affected families in the Cincinnati area. "People who take on this procedure need to ask themselves ‘Are we doing as good a job as the other places?’ " he said. He also told me that Cincinnati Children’s counselors make it clear to prospective families that if they prefer, they could travel to CHOP, Vanderbilt, or UCSF, the U.S. sites with the most experience and best-documented track records.

It’s all a balance of risk and benefit.

–Mitchel L. Zoler (on Twitter @mitchelzoler)

The Double-Edged Sword of Doctor Speak

Imagine if you will that you’re in the throes of labor (there is a point to this exercise in unplanned parenthood, so bear with me).

Between contractions, there’s a nattering in your ear about the use of local anesthesia prior to the epidural that friends swear will allow you to actually consider doing this again.

The injection is announced by someone saying either, "We are going to give you a local anesthetic that will numb the area so that you will be comfortable during the procedure" or "You are going to feel a big bee sting; this is the worst part of the procedure."

Not surprising, the perceived pain was found to be significantly greater after the latter statement.

German investigators highlight this experiment as part of a detailed and fascinating look at the nocebo phenomenon, or the opposite of the placebo phenomenon, in medicine.

The topic has apparently been given the short shrift by scientists and clinicians. A recent PubMed search by the Germans revealed roughly 2,200 studies penned on the placebo effect, but only 151 publications on the nocebo effect, with the vast majority of these being editorials, commentaries, and reviews, rather than empirical studies.

Dr. Winfried Häuser of the Klinikum Saarbrücken and his associates, nail the crux of the issue with a quote from cardiologist and Nobel laureate Dr. Bernard Lown that "Words are the most powerful tool a doctor possesses, but words, like a two-edged sword, can maim as well as heal."

The article touches on the neurobiological mechanisms of the nocebo effect, which like those for the placebo effect, center around conditioning and reaction to expectations – albeit in this case negative expectations.

There is a discussion about who might be at risk of nocebo responses (yes, ladies he’s speaking to us), and an amusing array of clinical studies illustrating the nocebo effect.

There’s a randomized controlled trial (RCT) of finasteride in benign prostate hyperplasia, in which sexual dysfunction was reported by 44% of patients informed of this possible side effect, compared with only 15% of those not informed.

Similarly, there’s another RCT of the beta-blocker atenolol in coronary heart disease. Rates of sexual dysfunction jumped from 3% of patients not told of the drug or side effect to 31% of those treated to complete details about both the drug and the possible sexual dysfunction

Where the review really hits its stride, however, is in the discussion of ethical problems that arise in everyday clinical practice where the nocebo phenomenon may be triggered by verbal and non-verbal communications by physicians and nurses.

The authors note that physicians are obliged to inform patients about the possible adverse events of a proposed treatment so they can make an informed decision, but also have a duty to minimize the risks of a medical intervention, including those induced by the patient briefing.

Strategies are offered to reduce this dilemma with the most obvious being patient education and communications training for medical staff.

Clinicians are also advised to focus on the proportion of patients who tolerate a procedure or drug rather than the proportion experiencing adverse events.

The most controversial suggestion is the concept of "permitted non-information." Patients agree not to receive information on mild and/or transient side effects, but must be briefed about severe and/or irreversible side effects. To respect their autonomy and preferences, patients could pick and chose what side effects they want to briefed on (or forego) from a list of categories of possible side effects for a drug or procedure.

When the German Medical Association gets round to updating its 1990 recommendations on patient briefing, the authors say there needs to be discussion on "whether it is legitimate to express a right of the patient not to know about complications and side effects of medical procedures and whether this must be respected by the physician."

There should also be debate on whether some patients might be left confused or uncertain by their inability to follow the comprehensive adverse event information found on package inserts or consent forms.

Such a strategy could be problematic in the United States, where nearly half of all adults (90 million people) have difficulty understanding and acting upon health information, according to the Institute of Medicine report "Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion."

Throw in the wracking pain of childbirth, the instability of bipolarity, or the confusion of Parkinson’s, and you’ve just made the lawyers of America incandescently happy.

Dr. Häuser reports reimbursement for training and travel costs from Eli Lilly and the Falk Foundation, and lecture fees from Lilly, the Falk Foundation and Janssen-Cilag. A co-author reports research funds from Sorin, Italy.

Imagine if you will that you’re in the throes of labor (there is a point to this exercise in unplanned parenthood, so bear with me).

Between contractions, there’s a nattering in your ear about the use of local anesthesia prior to the epidural that friends swear will allow you to actually consider doing this again.

The injection is announced by someone saying either, "We are going to give you a local anesthetic that will numb the area so that you will be comfortable during the procedure" or "You are going to feel a big bee sting; this is the worst part of the procedure."

Not surprising, the perceived pain was found to be significantly greater after the latter statement.

German investigators highlight this experiment as part of a detailed and fascinating look at the nocebo phenomenon, or the opposite of the placebo phenomenon, in medicine.

The topic has apparently been given the short shrift by scientists and clinicians. A recent PubMed search by the Germans revealed roughly 2,200 studies penned on the placebo effect, but only 151 publications on the nocebo effect, with the vast majority of these being editorials, commentaries, and reviews, rather than empirical studies.

Dr. Winfried Häuser of the Klinikum Saarbrücken and his associates, nail the crux of the issue with a quote from cardiologist and Nobel laureate Dr. Bernard Lown that "Words are the most powerful tool a doctor possesses, but words, like a two-edged sword, can maim as well as heal."

The article touches on the neurobiological mechanisms of the nocebo effect, which like those for the placebo effect, center around conditioning and reaction to expectations – albeit in this case negative expectations.

There is a discussion about who might be at risk of nocebo responses (yes, ladies he’s speaking to us), and an amusing array of clinical studies illustrating the nocebo effect.

There’s a randomized controlled trial (RCT) of finasteride in benign prostate hyperplasia, in which sexual dysfunction was reported by 44% of patients informed of this possible side effect, compared with only 15% of those not informed.

Similarly, there’s another RCT of the beta-blocker atenolol in coronary heart disease. Rates of sexual dysfunction jumped from 3% of patients not told of the drug or side effect to 31% of those treated to complete details about both the drug and the possible sexual dysfunction

Where the review really hits its stride, however, is in the discussion of ethical problems that arise in everyday clinical practice where the nocebo phenomenon may be triggered by verbal and non-verbal communications by physicians and nurses.

The authors note that physicians are obliged to inform patients about the possible adverse events of a proposed treatment so they can make an informed decision, but also have a duty to minimize the risks of a medical intervention, including those induced by the patient briefing.

Strategies are offered to reduce this dilemma with the most obvious being patient education and communications training for medical staff.

Clinicians are also advised to focus on the proportion of patients who tolerate a procedure or drug rather than the proportion experiencing adverse events.

The most controversial suggestion is the concept of "permitted non-information." Patients agree not to receive information on mild and/or transient side effects, but must be briefed about severe and/or irreversible side effects. To respect their autonomy and preferences, patients could pick and chose what side effects they want to briefed on (or forego) from a list of categories of possible side effects for a drug or procedure.

When the German Medical Association gets round to updating its 1990 recommendations on patient briefing, the authors say there needs to be discussion on "whether it is legitimate to express a right of the patient not to know about complications and side effects of medical procedures and whether this must be respected by the physician."

There should also be debate on whether some patients might be left confused or uncertain by their inability to follow the comprehensive adverse event information found on package inserts or consent forms.

Such a strategy could be problematic in the United States, where nearly half of all adults (90 million people) have difficulty understanding and acting upon health information, according to the Institute of Medicine report "Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion."

Throw in the wracking pain of childbirth, the instability of bipolarity, or the confusion of Parkinson’s, and you’ve just made the lawyers of America incandescently happy.

Dr. Häuser reports reimbursement for training and travel costs from Eli Lilly and the Falk Foundation, and lecture fees from Lilly, the Falk Foundation and Janssen-Cilag. A co-author reports research funds from Sorin, Italy.

Imagine if you will that you’re in the throes of labor (there is a point to this exercise in unplanned parenthood, so bear with me).

Between contractions, there’s a nattering in your ear about the use of local anesthesia prior to the epidural that friends swear will allow you to actually consider doing this again.

The injection is announced by someone saying either, "We are going to give you a local anesthetic that will numb the area so that you will be comfortable during the procedure" or "You are going to feel a big bee sting; this is the worst part of the procedure."

Not surprising, the perceived pain was found to be significantly greater after the latter statement.

German investigators highlight this experiment as part of a detailed and fascinating look at the nocebo phenomenon, or the opposite of the placebo phenomenon, in medicine.

The topic has apparently been given the short shrift by scientists and clinicians. A recent PubMed search by the Germans revealed roughly 2,200 studies penned on the placebo effect, but only 151 publications on the nocebo effect, with the vast majority of these being editorials, commentaries, and reviews, rather than empirical studies.

Dr. Winfried Häuser of the Klinikum Saarbrücken and his associates, nail the crux of the issue with a quote from cardiologist and Nobel laureate Dr. Bernard Lown that "Words are the most powerful tool a doctor possesses, but words, like a two-edged sword, can maim as well as heal."

The article touches on the neurobiological mechanisms of the nocebo effect, which like those for the placebo effect, center around conditioning and reaction to expectations – albeit in this case negative expectations.

There is a discussion about who might be at risk of nocebo responses (yes, ladies he’s speaking to us), and an amusing array of clinical studies illustrating the nocebo effect.

There’s a randomized controlled trial (RCT) of finasteride in benign prostate hyperplasia, in which sexual dysfunction was reported by 44% of patients informed of this possible side effect, compared with only 15% of those not informed.

Similarly, there’s another RCT of the beta-blocker atenolol in coronary heart disease. Rates of sexual dysfunction jumped from 3% of patients not told of the drug or side effect to 31% of those treated to complete details about both the drug and the possible sexual dysfunction

Where the review really hits its stride, however, is in the discussion of ethical problems that arise in everyday clinical practice where the nocebo phenomenon may be triggered by verbal and non-verbal communications by physicians and nurses.

The authors note that physicians are obliged to inform patients about the possible adverse events of a proposed treatment so they can make an informed decision, but also have a duty to minimize the risks of a medical intervention, including those induced by the patient briefing.

Strategies are offered to reduce this dilemma with the most obvious being patient education and communications training for medical staff.

Clinicians are also advised to focus on the proportion of patients who tolerate a procedure or drug rather than the proportion experiencing adverse events.

The most controversial suggestion is the concept of "permitted non-information." Patients agree not to receive information on mild and/or transient side effects, but must be briefed about severe and/or irreversible side effects. To respect their autonomy and preferences, patients could pick and chose what side effects they want to briefed on (or forego) from a list of categories of possible side effects for a drug or procedure.

When the German Medical Association gets round to updating its 1990 recommendations on patient briefing, the authors say there needs to be discussion on "whether it is legitimate to express a right of the patient not to know about complications and side effects of medical procedures and whether this must be respected by the physician."

There should also be debate on whether some patients might be left confused or uncertain by their inability to follow the comprehensive adverse event information found on package inserts or consent forms.

Such a strategy could be problematic in the United States, where nearly half of all adults (90 million people) have difficulty understanding and acting upon health information, according to the Institute of Medicine report "Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion."

Throw in the wracking pain of childbirth, the instability of bipolarity, or the confusion of Parkinson’s, and you’ve just made the lawyers of America incandescently happy.

Dr. Häuser reports reimbursement for training and travel costs from Eli Lilly and the Falk Foundation, and lecture fees from Lilly, the Falk Foundation and Janssen-Cilag. A co-author reports research funds from Sorin, Italy.

The U.S. Obesity Epidemic and Surging Liver Cancer

If there is one truism that trumps everything else these days about U.S. health, it’s that America is a chubby country that keeps getting fatter.

The consequences seep into every corner of the nation’s medical state, including the surprising fact that obesity and the type 2 diabetes it causes are likely pushing up the incidence of liver cancer – hepatocellular carcinoma – to unprecedented heights.

When I covered Digestive Disease Week in San Diego recently, one of the biggest stories I heard was that U.S. liver-cancer rates tripled from 1975-2007, and that the numbers continued to rise from the mid to the late 2000s. (My full report on this is here).

Granted, factors other than just obesity play into the liver cancer surge, notably the sizable number of Americans infected with either hepatitis B or C virus, and the fact that as they age their risk for developing hepatocellular carcinoma rises.

But new U.S. infections by hepatitis B and C are largely under control these days (although people infected elsewhere continue to emigrate to the United States). The part of the booming liver-cancer story that is by no means under control is the obesity part.

Every time I see a new CDC map for U.S. obesity prevalence, the colors on it keep getting redder and darker (the CDC’s code for higher prevalence rates).

Earlier this year, the CDC reported a 36% obesity prevalence rate for the entire U.S. population – and still on the rise – and just a few weeks ago we heard that obesity among children and adolescents had hit a new high of 17%. With obesity seemingly on an unchanging upward trajectory, one can only wonder what rates of liver cancer it might produce in the future. Obesity carries a special relationship with the liver, and it’s not pretty. Just consider any goose headed to a foie-gras future.

Until now, the evidence linking obesity and liver cancer, and type 2 diabetes and liver cancer has been epidemiologic. Compelling, but just an association. At DDW, a new study provided more observational data on the diabetes-liver cancer link, and while still circumstantial it further supports the notion and also carries an intriguing punchline.

The study, done in Taiwan, examined 97,000 hepatocellular carcinoma patients and 195,000 matched controls. The analysis showed that people with diabetes had a two-fold increased risk for liver cancer compared with those without diabetes. Even more striking, the analysis also showed that people with diabetes treated with the oral hypoglycemic drug metformin had their risk for liver cancer cut in half compared with those not on metformin, and those with diabetes treated with a glitazone drug (such as pioglitazone-Actos) had their risk cut nearly in half.

The best solution would be if people avoided obesity and type 2 diabetes all together. Both conditions cause a lot of medical problems, and this new evidence indicates more strongly than ever before that liver cancer is one of them.

— Mitchel Zoler (on Twitter @mitchelzoler)

If there is one truism that trumps everything else these days about U.S. health, it’s that America is a chubby country that keeps getting fatter.

The consequences seep into every corner of the nation’s medical state, including the surprising fact that obesity and the type 2 diabetes it causes are likely pushing up the incidence of liver cancer – hepatocellular carcinoma – to unprecedented heights.

When I covered Digestive Disease Week in San Diego recently, one of the biggest stories I heard was that U.S. liver-cancer rates tripled from 1975-2007, and that the numbers continued to rise from the mid to the late 2000s. (My full report on this is here).

Granted, factors other than just obesity play into the liver cancer surge, notably the sizable number of Americans infected with either hepatitis B or C virus, and the fact that as they age their risk for developing hepatocellular carcinoma rises.

But new U.S. infections by hepatitis B and C are largely under control these days (although people infected elsewhere continue to emigrate to the United States). The part of the booming liver-cancer story that is by no means under control is the obesity part.

Every time I see a new CDC map for U.S. obesity prevalence, the colors on it keep getting redder and darker (the CDC’s code for higher prevalence rates).

Earlier this year, the CDC reported a 36% obesity prevalence rate for the entire U.S. population – and still on the rise – and just a few weeks ago we heard that obesity among children and adolescents had hit a new high of 17%. With obesity seemingly on an unchanging upward trajectory, one can only wonder what rates of liver cancer it might produce in the future. Obesity carries a special relationship with the liver, and it’s not pretty. Just consider any goose headed to a foie-gras future.

Until now, the evidence linking obesity and liver cancer, and type 2 diabetes and liver cancer has been epidemiologic. Compelling, but just an association. At DDW, a new study provided more observational data on the diabetes-liver cancer link, and while still circumstantial it further supports the notion and also carries an intriguing punchline.

The study, done in Taiwan, examined 97,000 hepatocellular carcinoma patients and 195,000 matched controls. The analysis showed that people with diabetes had a two-fold increased risk for liver cancer compared with those without diabetes. Even more striking, the analysis also showed that people with diabetes treated with the oral hypoglycemic drug metformin had their risk for liver cancer cut in half compared with those not on metformin, and those with diabetes treated with a glitazone drug (such as pioglitazone-Actos) had their risk cut nearly in half.

The best solution would be if people avoided obesity and type 2 diabetes all together. Both conditions cause a lot of medical problems, and this new evidence indicates more strongly than ever before that liver cancer is one of them.

— Mitchel Zoler (on Twitter @mitchelzoler)

If there is one truism that trumps everything else these days about U.S. health, it’s that America is a chubby country that keeps getting fatter.

The consequences seep into every corner of the nation’s medical state, including the surprising fact that obesity and the type 2 diabetes it causes are likely pushing up the incidence of liver cancer – hepatocellular carcinoma – to unprecedented heights.

When I covered Digestive Disease Week in San Diego recently, one of the biggest stories I heard was that U.S. liver-cancer rates tripled from 1975-2007, and that the numbers continued to rise from the mid to the late 2000s. (My full report on this is here).

Granted, factors other than just obesity play into the liver cancer surge, notably the sizable number of Americans infected with either hepatitis B or C virus, and the fact that as they age their risk for developing hepatocellular carcinoma rises.

But new U.S. infections by hepatitis B and C are largely under control these days (although people infected elsewhere continue to emigrate to the United States). The part of the booming liver-cancer story that is by no means under control is the obesity part.

Every time I see a new CDC map for U.S. obesity prevalence, the colors on it keep getting redder and darker (the CDC’s code for higher prevalence rates).

Earlier this year, the CDC reported a 36% obesity prevalence rate for the entire U.S. population – and still on the rise – and just a few weeks ago we heard that obesity among children and adolescents had hit a new high of 17%. With obesity seemingly on an unchanging upward trajectory, one can only wonder what rates of liver cancer it might produce in the future. Obesity carries a special relationship with the liver, and it’s not pretty. Just consider any goose headed to a foie-gras future.

Until now, the evidence linking obesity and liver cancer, and type 2 diabetes and liver cancer has been epidemiologic. Compelling, but just an association. At DDW, a new study provided more observational data on the diabetes-liver cancer link, and while still circumstantial it further supports the notion and also carries an intriguing punchline.

The study, done in Taiwan, examined 97,000 hepatocellular carcinoma patients and 195,000 matched controls. The analysis showed that people with diabetes had a two-fold increased risk for liver cancer compared with those without diabetes. Even more striking, the analysis also showed that people with diabetes treated with the oral hypoglycemic drug metformin had their risk for liver cancer cut in half compared with those not on metformin, and those with diabetes treated with a glitazone drug (such as pioglitazone-Actos) had their risk cut nearly in half.

The best solution would be if people avoided obesity and type 2 diabetes all together. Both conditions cause a lot of medical problems, and this new evidence indicates more strongly than ever before that liver cancer is one of them.

— Mitchel Zoler (on Twitter @mitchelzoler)

'The Talk' About PSA Screening Just Got Thornier

Nuance is not a commonly cited virtue of American discourse, as you well know if you’ve watched reality television of late, or, for that matter, any recent political debate. And that’s what makes me nervous about the recent decision by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) to recommend against routine screening for prostate cancer using prostate-specific antigen levels.

I’m neither a physician nor a biostatistician; rest assured, I won’t argue the science here. But I do worry about the psychological implications of a Grade D recommendation (considered "at least fair" evidence) that screening does more harm to men than good.

The task force’s report, published online May 21 in Annals of Internal Medicine (annals.org), makes some excellent points about the need for more reliable screening measures and real quality-of-life costs associated with false positive PSA results and aggressive treatment of what is, in many cases but not all, a slow-growing disease.

Its call for better research deserves special mention. Prostate cancer, in my opinion, has long been a neglected step-brother in cancer research funding, despite the fact that it kills more American men than does any other cancer, except lung cancer. Just because I was curious, I compared this week the number of hits on PubMed for the search terms "prostate cancer" and "screening" versus "breast cancer" and "screening." To be sure, it’s a crude measure of relative attention, but the disparate tally was striking: 55,758 to 129,451.

The task force report also offers physicians a brief, handy guide on how to talk with patients about the latest findings, including three generic "patient scenarios." I think that’s fine, as far as it goes, but what the guide fails to capture is the nuance of American attitudes toward screening, toward medicine in general (and especially large, impersonal task forces known by their acronyms), toward preventive health care, and toward prostate cancer itself.

It will be those attitudes physicians will encounter once patients, their partners, and families hear the recommendations in a 12-second sound bite, while channel-flipping on their way to an update on the Kardashian family.

There will be patients, I suspect, who will completely disregard the recommendations; a few, perhaps, because they’ve read of the scientific objections of many dubious urologists.

More, undoubtedly, will suspect a conspiracy between medicine and insurance companies bent on depriving patients of life-saving treatment in the interest of saving a few bucks.