User login

Midurethral slings

Minimally invasive synthetic midurethral slings may be considered the standard of care for the surgical treatment of stress urinary incontinence – and a first-line treatment for severe cases of the condition – based on the publication of numerous level 1 randomized trials, high-quality reviews, and recent position statements from professional societies.

The current evidence base shows that midurethral sling operations are as effective as bladder neck slings and colposuspension, with less morbidity. Operating times are shorter, and local anesthesia is possible. Compared with pubovaginal slings, which are fixed at the bladder neck, midurethral slings are associated with less postoperative voiding dysfunction and fewer de novo urgency symptoms.

Midurethral slings (MUS) also have been shown to be more successful – and more cost-effective – than pelvic floor physiotherapy for stress urinary incontinence (SUI) overall, with the possible exception of mild SUI.

Physiotherapy involving pelvic floor muscle therapy has long been advocated as a first-line treatment for SUI, with MUS surgery often recommended when physiotherapy is unsuccessful. In recent years, however, with high success rates for MUS, the role of physiotherapy as a first-line treatment has become more debatable.

A multicenter randomized trial in 660 women published last year in the New England Journal of Medicine substantiated what many of us have seen in our practices and in other published studies: significantly lower rates of improvement and cure with initial physiotherapy than with primary surgery.

Initial MUS surgery resulted in higher rates of subjective improvement, compared with initial physiotherapy (91% vs. 64%), subjective cure (85% v. 53%), and objective cure (77% v. 59%) at 1 year. Moreover, a significant number of women – 49% – chose to abandon conservative therapy and have MUS surgery for their SUI during the study period (N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;369:1124-33).

A joint position statement published in early 2014 by the American Urogynecologic Society (AUGS) and the Society of Urodynamics, Female Pelvic Medicine and Urogenital Reconstruction (SUFU) calls MUS the most extensively studied anti-incontinence procedure and “probably the most important advancement in the treatment of SUI in the last 50 years.” More than 2,000 publications in the literature have described the procedure for SUI, and multiple randomized controlled trials have compared various types of MUS procedures as well as MUS to other nonmesh SUI procedures, the statement says.

My colleague and I recently modeled the cost-effectiveness of pelvic floor muscle therapy and continence pessaries vs. surgical treatment with MUS for initial treatment of SUI. Initial treatment with MUS was the best strategy, with an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of $32,132 per quality-adjusted life-year, compared with initial treatment with pelvic floor muscle therapy. Under our model, treatment with a continence pessary would never be the preferred choice due to low subjective cure rates (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2014;211:565.e1-6).

I now tell patients who present with a history of severe stress incontinence, and who leak on a cough stress test, that a trial of pelvic floor physiotherapy is an option but one with a lower likelihood of success. I recommend an MUS as primary treatment for these patients, and the question then often becomes which sling to use.

Sling selection

There are two broad approaches to MUS surgery – retropubic and transobturator – and within each approach, there are different routes for the delivery of the polypropylene mesh sling.

Retropubic slings. Retropubic slings are passed transvaginally at the midurethral level through the retropubic space. Tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) has been used in millions of women worldwide, with good long-term outcomes, since it was introduced by Dr. Ulf Ulmsten in 1995. The TVT procedure utilizes a bottom-up approach, with curved needles being passed from a small vaginal incision up through the retropubic space to exit through two suprapubic incisions.

A second type of retropubic sling – the suprapubic urethral support sling (SPARC, American Medical Systems) – utilizes a downward-pass, or top-down, approach in which a metal trocar is passed through suprapubic incisions and down through the retropubic space to exit a vaginal incision.

The theoretical advantages of this modification to the TVT procedure have included more control over the needle introducer near the rectus fascia, and a lower risk of bowel and vascular injury. However, comparisons during the last decade of the two retropubic approaches have suggested slightly better outcomes – relating both to cure rates and to complication rates – with TVT compared with SPARC.

A Cochrane Review published in 2009, titled “Minimally invasive synthetic suburethral sling operations for stress urinary incontinence in women,” provided higher-level evidence in favor of bottom-up slings. A sub-meta-analysis of five randomized controlled trials – part of a broader intervention review – showed that a retropubic bottom-up approach was more effective than a top-down route (risk ratio, 1.10), with higher subjective and objective SUI cure rates (Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2009(4): CD006375). There also was significantly less bladder perforation, less mesh erosion, and less voiding dysfunction.

TVT slings, therefore, appear to be somewhat superior, with statistically significant differences in each of the domains of efficacy and morbidity. Still, surgeon experience and skill remain factors in sling selection; the surgeon who feels comfortable and skilled with a top-down approach and has little experience with a bottom-up approach should continue with SPARC. For surgeons who are skilled with both approaches, it might well be preferable to favor TVT.

Transobturator slings. The transobturator approach was developed to minimize the potential for bladder and bowel injuries by avoiding the pelvic organs in the retropubic space. The sling is introduced either through an inside-out technique, with the needle passed from a vaginal incision and out through the obturator foramen, or through an outside-in technique, with the needle passed through the thigh and then out through the vaginal incision.

A meta-analysis of trials of transobturator sling procedures – including four direct-comparison, randomized controlled trials of the inside-out technique vs. the outside-in technique – showed no significant differences between the two approaches in subjective and objective SUI cure rates in the short term. Rates of postoperative voiding difficulties and de novo urgency symptoms were similar (BJU Int. 2010;106:68-76).

Making a choice. Each of the currently available midurethral slings appears to work well, overall, with few clinically significant differences in outcomes. On the other hand, midurethral slings are not all the same. It is important to appreciate the more subtle differences, to be aware of the evidence, and to be appropriately trained. Often, sling selection involves weighing the risks and benefits for the individual.

On a broad scale, the most recent high-level comparison of the retropubic and transobturator slings appears to be a meta-analysis in which retropubic midurethral slings showed better objective and subjective cure rates than transobturator midurethral slings. Women treated with retropubic slings had a 35% higher odds of objective cure and a 24% higher odds of subjective cure. (The weighted average objective cure rates were 87% for retropubic slings vs. 83% for transobturator slings with a weighted average follow-up of approximately 17 months. The weighted average subjective cure rates were 76% and 73%, respectively.)

Operating times were longer with retropubic slings, but lengths of stay were equivalent between the two types of procedures. This was based on 17 studies of about 3,000 women (J. Urology 2014 [doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2014.09.104]).

The types of complications seen with each approach differed. Bladder perforation was significantly more common with retropubic slings (3.2% vs. 0.2%), as was bleeding (3.2% v. 1.1%). Transobturator slings were associated with more cases of neurologic symptoms (9.4% v. 3.5%) and vaginal perforation (3.6% v. 0.9%).

This new review provides updated information to the 2009 Cochrane Review mentioned above, which reported that women were less likely to be continent after operations performed via the obturator route, but also less likely to have encountered complications. More specifically, objective cure rates were slightly higher with retropubic slings than with transobturator slings (88% vs. 84%) in the 2009 review. There was no difference in subjective cure rates. With the obturator route, there was less voiding dysfunction, blood loss, and bladder perforation (0.3% v. 5.5%).

Other pivotal trials since the 2009 Cochrane Review include a multicenter randomized equivalence trial published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2010. The trial randomized 597 women to transobturator or retropubic sling surgery, and found no significant differences in subjective success (56% vs. 62%) or in objective success (78% vs. 81%) at 12 months (N. Engl. J. Med. 2010;362:2066-76).

There is some level 1 evidence suggesting that for severe incontinence involving intrinsic sphincter deficiency (ISD), a retropubic TVT sling is the more effective procedure. A randomized trial of 164 women with urodynamic SUI and ISD, for instance, found that 21% of those in the TVT group and 45% of those in the transobturator group had urodynamic SUI 6 months postoperatively.

The risk ratio of repeat surgery was 2.6 times higher in the transobturator group than in the retropubic TVT group (Obstet. Gynecol. 2008;112:1253-61). TVT was more effective both with and without concurrent pelvic organ prolapse repair.

I tell my patients with severe SUI or ISD, therefore, that retropubic sling procedures appear to be preferable. (Exceptions include the patient who has a history of retropubic surgeries, in whom passing the sling through this route may not be the safest approach, as well as the patient who has had mesh erosion into the bladder.)

In patients whose SUI is less severe, I counsel that a transobturator sling confers satisfaction rates similar to those of a retropubic sling and has a lower risk of complications, such as postoperative voiding dysfunction and bladder perforations, but with the possible trade-off of more thigh discomfort. I also might recommend a transobturator sling to patients with more pronounced initial complaints of urinary urgency and frequency, and to patients who have minor voiding dysfunction or a low level of incomplete bladder emptying.

While often short-lived, the small risk of thigh pain with a transobturator sling makes me less likely to recommend this type of sling for a woman who is a marathon runner or competitive athlete. In her case, an analysis of possible complications includes the consideration that bladder perforation can be addressed relatively quickly in the operating room, while persistent thigh discomfort, though relatively rare, could be a debilitating problem.

Single-incision slings

There appears to be emerging evidence suggesting that some of the fixed and adjustable single-incision slings currently available may have efficacy similar to that of the slings that are now widely used.

A Cochrane Review presented at the 2014 AUGS-IUGA scientific meeting and published this summer concludes that there is not enough evidence on single-incision slings compared with retropubic or transobturator slings to allow reliable comparisons, and that additional, adequately powered, high-quality trials with longer-term follow-up are needed (Cochrane Database Sys. Rev. 2014;6:CD008709). However, research completed since the review offers additional data.

For instance, at the 2014 AUGS-IUGA scientific meeting this summer, an oral paper presentation highlighted findings of a randomized controlled trial that showed similar cure rates after surgery with the MiniArc, a fixed single-incision sling, and the Monarc transobturator sling (both by American Medical Systems) at 24 months. The study randomized 234 women to either sling and found no significant differences in subjective outcomes, objective outcomes, or results on various quality-of-life questionnaires.

As such studies are published and more evidence emerges, we will gain a clearer picture of how the newer single-incision slings compare to the well-tested retropubic and transobturator slings with respect to efficacy and safety.

Single-incision slings require only a small vaginal incision and no exit points. Without abdominal or thigh incisions, these new procedures – intended for less severe SUI (no ISD) – may offer improved perioperative and postoperative patient comfort and a potentially decreased risk of surgical injury to the adductor muscles, as well as a decreased risk of vascular and nerve injury. Candidates for these slings may include those who are very athletic, those who are obese, and those with a history of prior retropubic or pelvic surgery.

Research appears to be progressing, but at this time we do not yet have level 1 evidence to support their routine use.

Dr. Sokol reported that he owns stock in Pelvalon, and is a clinical adviser to that company. He also is a national principal investigator for American Medical Systems, and the recipient of research grants from Acell and several other companies.

Minimally invasive synthetic midurethral slings may be considered the standard of care for the surgical treatment of stress urinary incontinence – and a first-line treatment for severe cases of the condition – based on the publication of numerous level 1 randomized trials, high-quality reviews, and recent position statements from professional societies.

The current evidence base shows that midurethral sling operations are as effective as bladder neck slings and colposuspension, with less morbidity. Operating times are shorter, and local anesthesia is possible. Compared with pubovaginal slings, which are fixed at the bladder neck, midurethral slings are associated with less postoperative voiding dysfunction and fewer de novo urgency symptoms.

Midurethral slings (MUS) also have been shown to be more successful – and more cost-effective – than pelvic floor physiotherapy for stress urinary incontinence (SUI) overall, with the possible exception of mild SUI.

Physiotherapy involving pelvic floor muscle therapy has long been advocated as a first-line treatment for SUI, with MUS surgery often recommended when physiotherapy is unsuccessful. In recent years, however, with high success rates for MUS, the role of physiotherapy as a first-line treatment has become more debatable.

A multicenter randomized trial in 660 women published last year in the New England Journal of Medicine substantiated what many of us have seen in our practices and in other published studies: significantly lower rates of improvement and cure with initial physiotherapy than with primary surgery.

Initial MUS surgery resulted in higher rates of subjective improvement, compared with initial physiotherapy (91% vs. 64%), subjective cure (85% v. 53%), and objective cure (77% v. 59%) at 1 year. Moreover, a significant number of women – 49% – chose to abandon conservative therapy and have MUS surgery for their SUI during the study period (N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;369:1124-33).

A joint position statement published in early 2014 by the American Urogynecologic Society (AUGS) and the Society of Urodynamics, Female Pelvic Medicine and Urogenital Reconstruction (SUFU) calls MUS the most extensively studied anti-incontinence procedure and “probably the most important advancement in the treatment of SUI in the last 50 years.” More than 2,000 publications in the literature have described the procedure for SUI, and multiple randomized controlled trials have compared various types of MUS procedures as well as MUS to other nonmesh SUI procedures, the statement says.

My colleague and I recently modeled the cost-effectiveness of pelvic floor muscle therapy and continence pessaries vs. surgical treatment with MUS for initial treatment of SUI. Initial treatment with MUS was the best strategy, with an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of $32,132 per quality-adjusted life-year, compared with initial treatment with pelvic floor muscle therapy. Under our model, treatment with a continence pessary would never be the preferred choice due to low subjective cure rates (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2014;211:565.e1-6).

I now tell patients who present with a history of severe stress incontinence, and who leak on a cough stress test, that a trial of pelvic floor physiotherapy is an option but one with a lower likelihood of success. I recommend an MUS as primary treatment for these patients, and the question then often becomes which sling to use.

Sling selection

There are two broad approaches to MUS surgery – retropubic and transobturator – and within each approach, there are different routes for the delivery of the polypropylene mesh sling.

Retropubic slings. Retropubic slings are passed transvaginally at the midurethral level through the retropubic space. Tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) has been used in millions of women worldwide, with good long-term outcomes, since it was introduced by Dr. Ulf Ulmsten in 1995. The TVT procedure utilizes a bottom-up approach, with curved needles being passed from a small vaginal incision up through the retropubic space to exit through two suprapubic incisions.

A second type of retropubic sling – the suprapubic urethral support sling (SPARC, American Medical Systems) – utilizes a downward-pass, or top-down, approach in which a metal trocar is passed through suprapubic incisions and down through the retropubic space to exit a vaginal incision.

The theoretical advantages of this modification to the TVT procedure have included more control over the needle introducer near the rectus fascia, and a lower risk of bowel and vascular injury. However, comparisons during the last decade of the two retropubic approaches have suggested slightly better outcomes – relating both to cure rates and to complication rates – with TVT compared with SPARC.

A Cochrane Review published in 2009, titled “Minimally invasive synthetic suburethral sling operations for stress urinary incontinence in women,” provided higher-level evidence in favor of bottom-up slings. A sub-meta-analysis of five randomized controlled trials – part of a broader intervention review – showed that a retropubic bottom-up approach was more effective than a top-down route (risk ratio, 1.10), with higher subjective and objective SUI cure rates (Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2009(4): CD006375). There also was significantly less bladder perforation, less mesh erosion, and less voiding dysfunction.

TVT slings, therefore, appear to be somewhat superior, with statistically significant differences in each of the domains of efficacy and morbidity. Still, surgeon experience and skill remain factors in sling selection; the surgeon who feels comfortable and skilled with a top-down approach and has little experience with a bottom-up approach should continue with SPARC. For surgeons who are skilled with both approaches, it might well be preferable to favor TVT.

Transobturator slings. The transobturator approach was developed to minimize the potential for bladder and bowel injuries by avoiding the pelvic organs in the retropubic space. The sling is introduced either through an inside-out technique, with the needle passed from a vaginal incision and out through the obturator foramen, or through an outside-in technique, with the needle passed through the thigh and then out through the vaginal incision.

A meta-analysis of trials of transobturator sling procedures – including four direct-comparison, randomized controlled trials of the inside-out technique vs. the outside-in technique – showed no significant differences between the two approaches in subjective and objective SUI cure rates in the short term. Rates of postoperative voiding difficulties and de novo urgency symptoms were similar (BJU Int. 2010;106:68-76).

Making a choice. Each of the currently available midurethral slings appears to work well, overall, with few clinically significant differences in outcomes. On the other hand, midurethral slings are not all the same. It is important to appreciate the more subtle differences, to be aware of the evidence, and to be appropriately trained. Often, sling selection involves weighing the risks and benefits for the individual.

On a broad scale, the most recent high-level comparison of the retropubic and transobturator slings appears to be a meta-analysis in which retropubic midurethral slings showed better objective and subjective cure rates than transobturator midurethral slings. Women treated with retropubic slings had a 35% higher odds of objective cure and a 24% higher odds of subjective cure. (The weighted average objective cure rates were 87% for retropubic slings vs. 83% for transobturator slings with a weighted average follow-up of approximately 17 months. The weighted average subjective cure rates were 76% and 73%, respectively.)

Operating times were longer with retropubic slings, but lengths of stay were equivalent between the two types of procedures. This was based on 17 studies of about 3,000 women (J. Urology 2014 [doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2014.09.104]).

The types of complications seen with each approach differed. Bladder perforation was significantly more common with retropubic slings (3.2% vs. 0.2%), as was bleeding (3.2% v. 1.1%). Transobturator slings were associated with more cases of neurologic symptoms (9.4% v. 3.5%) and vaginal perforation (3.6% v. 0.9%).

This new review provides updated information to the 2009 Cochrane Review mentioned above, which reported that women were less likely to be continent after operations performed via the obturator route, but also less likely to have encountered complications. More specifically, objective cure rates were slightly higher with retropubic slings than with transobturator slings (88% vs. 84%) in the 2009 review. There was no difference in subjective cure rates. With the obturator route, there was less voiding dysfunction, blood loss, and bladder perforation (0.3% v. 5.5%).

Other pivotal trials since the 2009 Cochrane Review include a multicenter randomized equivalence trial published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2010. The trial randomized 597 women to transobturator or retropubic sling surgery, and found no significant differences in subjective success (56% vs. 62%) or in objective success (78% vs. 81%) at 12 months (N. Engl. J. Med. 2010;362:2066-76).

There is some level 1 evidence suggesting that for severe incontinence involving intrinsic sphincter deficiency (ISD), a retropubic TVT sling is the more effective procedure. A randomized trial of 164 women with urodynamic SUI and ISD, for instance, found that 21% of those in the TVT group and 45% of those in the transobturator group had urodynamic SUI 6 months postoperatively.

The risk ratio of repeat surgery was 2.6 times higher in the transobturator group than in the retropubic TVT group (Obstet. Gynecol. 2008;112:1253-61). TVT was more effective both with and without concurrent pelvic organ prolapse repair.

I tell my patients with severe SUI or ISD, therefore, that retropubic sling procedures appear to be preferable. (Exceptions include the patient who has a history of retropubic surgeries, in whom passing the sling through this route may not be the safest approach, as well as the patient who has had mesh erosion into the bladder.)

In patients whose SUI is less severe, I counsel that a transobturator sling confers satisfaction rates similar to those of a retropubic sling and has a lower risk of complications, such as postoperative voiding dysfunction and bladder perforations, but with the possible trade-off of more thigh discomfort. I also might recommend a transobturator sling to patients with more pronounced initial complaints of urinary urgency and frequency, and to patients who have minor voiding dysfunction or a low level of incomplete bladder emptying.

While often short-lived, the small risk of thigh pain with a transobturator sling makes me less likely to recommend this type of sling for a woman who is a marathon runner or competitive athlete. In her case, an analysis of possible complications includes the consideration that bladder perforation can be addressed relatively quickly in the operating room, while persistent thigh discomfort, though relatively rare, could be a debilitating problem.

Single-incision slings

There appears to be emerging evidence suggesting that some of the fixed and adjustable single-incision slings currently available may have efficacy similar to that of the slings that are now widely used.

A Cochrane Review presented at the 2014 AUGS-IUGA scientific meeting and published this summer concludes that there is not enough evidence on single-incision slings compared with retropubic or transobturator slings to allow reliable comparisons, and that additional, adequately powered, high-quality trials with longer-term follow-up are needed (Cochrane Database Sys. Rev. 2014;6:CD008709). However, research completed since the review offers additional data.

For instance, at the 2014 AUGS-IUGA scientific meeting this summer, an oral paper presentation highlighted findings of a randomized controlled trial that showed similar cure rates after surgery with the MiniArc, a fixed single-incision sling, and the Monarc transobturator sling (both by American Medical Systems) at 24 months. The study randomized 234 women to either sling and found no significant differences in subjective outcomes, objective outcomes, or results on various quality-of-life questionnaires.

As such studies are published and more evidence emerges, we will gain a clearer picture of how the newer single-incision slings compare to the well-tested retropubic and transobturator slings with respect to efficacy and safety.

Single-incision slings require only a small vaginal incision and no exit points. Without abdominal or thigh incisions, these new procedures – intended for less severe SUI (no ISD) – may offer improved perioperative and postoperative patient comfort and a potentially decreased risk of surgical injury to the adductor muscles, as well as a decreased risk of vascular and nerve injury. Candidates for these slings may include those who are very athletic, those who are obese, and those with a history of prior retropubic or pelvic surgery.

Research appears to be progressing, but at this time we do not yet have level 1 evidence to support their routine use.

Dr. Sokol reported that he owns stock in Pelvalon, and is a clinical adviser to that company. He also is a national principal investigator for American Medical Systems, and the recipient of research grants from Acell and several other companies.

Minimally invasive synthetic midurethral slings may be considered the standard of care for the surgical treatment of stress urinary incontinence – and a first-line treatment for severe cases of the condition – based on the publication of numerous level 1 randomized trials, high-quality reviews, and recent position statements from professional societies.

The current evidence base shows that midurethral sling operations are as effective as bladder neck slings and colposuspension, with less morbidity. Operating times are shorter, and local anesthesia is possible. Compared with pubovaginal slings, which are fixed at the bladder neck, midurethral slings are associated with less postoperative voiding dysfunction and fewer de novo urgency symptoms.

Midurethral slings (MUS) also have been shown to be more successful – and more cost-effective – than pelvic floor physiotherapy for stress urinary incontinence (SUI) overall, with the possible exception of mild SUI.

Physiotherapy involving pelvic floor muscle therapy has long been advocated as a first-line treatment for SUI, with MUS surgery often recommended when physiotherapy is unsuccessful. In recent years, however, with high success rates for MUS, the role of physiotherapy as a first-line treatment has become more debatable.

A multicenter randomized trial in 660 women published last year in the New England Journal of Medicine substantiated what many of us have seen in our practices and in other published studies: significantly lower rates of improvement and cure with initial physiotherapy than with primary surgery.

Initial MUS surgery resulted in higher rates of subjective improvement, compared with initial physiotherapy (91% vs. 64%), subjective cure (85% v. 53%), and objective cure (77% v. 59%) at 1 year. Moreover, a significant number of women – 49% – chose to abandon conservative therapy and have MUS surgery for their SUI during the study period (N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;369:1124-33).

A joint position statement published in early 2014 by the American Urogynecologic Society (AUGS) and the Society of Urodynamics, Female Pelvic Medicine and Urogenital Reconstruction (SUFU) calls MUS the most extensively studied anti-incontinence procedure and “probably the most important advancement in the treatment of SUI in the last 50 years.” More than 2,000 publications in the literature have described the procedure for SUI, and multiple randomized controlled trials have compared various types of MUS procedures as well as MUS to other nonmesh SUI procedures, the statement says.

My colleague and I recently modeled the cost-effectiveness of pelvic floor muscle therapy and continence pessaries vs. surgical treatment with MUS for initial treatment of SUI. Initial treatment with MUS was the best strategy, with an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of $32,132 per quality-adjusted life-year, compared with initial treatment with pelvic floor muscle therapy. Under our model, treatment with a continence pessary would never be the preferred choice due to low subjective cure rates (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2014;211:565.e1-6).

I now tell patients who present with a history of severe stress incontinence, and who leak on a cough stress test, that a trial of pelvic floor physiotherapy is an option but one with a lower likelihood of success. I recommend an MUS as primary treatment for these patients, and the question then often becomes which sling to use.

Sling selection

There are two broad approaches to MUS surgery – retropubic and transobturator – and within each approach, there are different routes for the delivery of the polypropylene mesh sling.

Retropubic slings. Retropubic slings are passed transvaginally at the midurethral level through the retropubic space. Tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) has been used in millions of women worldwide, with good long-term outcomes, since it was introduced by Dr. Ulf Ulmsten in 1995. The TVT procedure utilizes a bottom-up approach, with curved needles being passed from a small vaginal incision up through the retropubic space to exit through two suprapubic incisions.

A second type of retropubic sling – the suprapubic urethral support sling (SPARC, American Medical Systems) – utilizes a downward-pass, or top-down, approach in which a metal trocar is passed through suprapubic incisions and down through the retropubic space to exit a vaginal incision.

The theoretical advantages of this modification to the TVT procedure have included more control over the needle introducer near the rectus fascia, and a lower risk of bowel and vascular injury. However, comparisons during the last decade of the two retropubic approaches have suggested slightly better outcomes – relating both to cure rates and to complication rates – with TVT compared with SPARC.

A Cochrane Review published in 2009, titled “Minimally invasive synthetic suburethral sling operations for stress urinary incontinence in women,” provided higher-level evidence in favor of bottom-up slings. A sub-meta-analysis of five randomized controlled trials – part of a broader intervention review – showed that a retropubic bottom-up approach was more effective than a top-down route (risk ratio, 1.10), with higher subjective and objective SUI cure rates (Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2009(4): CD006375). There also was significantly less bladder perforation, less mesh erosion, and less voiding dysfunction.

TVT slings, therefore, appear to be somewhat superior, with statistically significant differences in each of the domains of efficacy and morbidity. Still, surgeon experience and skill remain factors in sling selection; the surgeon who feels comfortable and skilled with a top-down approach and has little experience with a bottom-up approach should continue with SPARC. For surgeons who are skilled with both approaches, it might well be preferable to favor TVT.

Transobturator slings. The transobturator approach was developed to minimize the potential for bladder and bowel injuries by avoiding the pelvic organs in the retropubic space. The sling is introduced either through an inside-out technique, with the needle passed from a vaginal incision and out through the obturator foramen, or through an outside-in technique, with the needle passed through the thigh and then out through the vaginal incision.

A meta-analysis of trials of transobturator sling procedures – including four direct-comparison, randomized controlled trials of the inside-out technique vs. the outside-in technique – showed no significant differences between the two approaches in subjective and objective SUI cure rates in the short term. Rates of postoperative voiding difficulties and de novo urgency symptoms were similar (BJU Int. 2010;106:68-76).

Making a choice. Each of the currently available midurethral slings appears to work well, overall, with few clinically significant differences in outcomes. On the other hand, midurethral slings are not all the same. It is important to appreciate the more subtle differences, to be aware of the evidence, and to be appropriately trained. Often, sling selection involves weighing the risks and benefits for the individual.

On a broad scale, the most recent high-level comparison of the retropubic and transobturator slings appears to be a meta-analysis in which retropubic midurethral slings showed better objective and subjective cure rates than transobturator midurethral slings. Women treated with retropubic slings had a 35% higher odds of objective cure and a 24% higher odds of subjective cure. (The weighted average objective cure rates were 87% for retropubic slings vs. 83% for transobturator slings with a weighted average follow-up of approximately 17 months. The weighted average subjective cure rates were 76% and 73%, respectively.)

Operating times were longer with retropubic slings, but lengths of stay were equivalent between the two types of procedures. This was based on 17 studies of about 3,000 women (J. Urology 2014 [doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2014.09.104]).

The types of complications seen with each approach differed. Bladder perforation was significantly more common with retropubic slings (3.2% vs. 0.2%), as was bleeding (3.2% v. 1.1%). Transobturator slings were associated with more cases of neurologic symptoms (9.4% v. 3.5%) and vaginal perforation (3.6% v. 0.9%).

This new review provides updated information to the 2009 Cochrane Review mentioned above, which reported that women were less likely to be continent after operations performed via the obturator route, but also less likely to have encountered complications. More specifically, objective cure rates were slightly higher with retropubic slings than with transobturator slings (88% vs. 84%) in the 2009 review. There was no difference in subjective cure rates. With the obturator route, there was less voiding dysfunction, blood loss, and bladder perforation (0.3% v. 5.5%).

Other pivotal trials since the 2009 Cochrane Review include a multicenter randomized equivalence trial published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2010. The trial randomized 597 women to transobturator or retropubic sling surgery, and found no significant differences in subjective success (56% vs. 62%) or in objective success (78% vs. 81%) at 12 months (N. Engl. J. Med. 2010;362:2066-76).

There is some level 1 evidence suggesting that for severe incontinence involving intrinsic sphincter deficiency (ISD), a retropubic TVT sling is the more effective procedure. A randomized trial of 164 women with urodynamic SUI and ISD, for instance, found that 21% of those in the TVT group and 45% of those in the transobturator group had urodynamic SUI 6 months postoperatively.

The risk ratio of repeat surgery was 2.6 times higher in the transobturator group than in the retropubic TVT group (Obstet. Gynecol. 2008;112:1253-61). TVT was more effective both with and without concurrent pelvic organ prolapse repair.

I tell my patients with severe SUI or ISD, therefore, that retropubic sling procedures appear to be preferable. (Exceptions include the patient who has a history of retropubic surgeries, in whom passing the sling through this route may not be the safest approach, as well as the patient who has had mesh erosion into the bladder.)

In patients whose SUI is less severe, I counsel that a transobturator sling confers satisfaction rates similar to those of a retropubic sling and has a lower risk of complications, such as postoperative voiding dysfunction and bladder perforations, but with the possible trade-off of more thigh discomfort. I also might recommend a transobturator sling to patients with more pronounced initial complaints of urinary urgency and frequency, and to patients who have minor voiding dysfunction or a low level of incomplete bladder emptying.

While often short-lived, the small risk of thigh pain with a transobturator sling makes me less likely to recommend this type of sling for a woman who is a marathon runner or competitive athlete. In her case, an analysis of possible complications includes the consideration that bladder perforation can be addressed relatively quickly in the operating room, while persistent thigh discomfort, though relatively rare, could be a debilitating problem.

Single-incision slings

There appears to be emerging evidence suggesting that some of the fixed and adjustable single-incision slings currently available may have efficacy similar to that of the slings that are now widely used.

A Cochrane Review presented at the 2014 AUGS-IUGA scientific meeting and published this summer concludes that there is not enough evidence on single-incision slings compared with retropubic or transobturator slings to allow reliable comparisons, and that additional, adequately powered, high-quality trials with longer-term follow-up are needed (Cochrane Database Sys. Rev. 2014;6:CD008709). However, research completed since the review offers additional data.

For instance, at the 2014 AUGS-IUGA scientific meeting this summer, an oral paper presentation highlighted findings of a randomized controlled trial that showed similar cure rates after surgery with the MiniArc, a fixed single-incision sling, and the Monarc transobturator sling (both by American Medical Systems) at 24 months. The study randomized 234 women to either sling and found no significant differences in subjective outcomes, objective outcomes, or results on various quality-of-life questionnaires.

As such studies are published and more evidence emerges, we will gain a clearer picture of how the newer single-incision slings compare to the well-tested retropubic and transobturator slings with respect to efficacy and safety.

Single-incision slings require only a small vaginal incision and no exit points. Without abdominal or thigh incisions, these new procedures – intended for less severe SUI (no ISD) – may offer improved perioperative and postoperative patient comfort and a potentially decreased risk of surgical injury to the adductor muscles, as well as a decreased risk of vascular and nerve injury. Candidates for these slings may include those who are very athletic, those who are obese, and those with a history of prior retropubic or pelvic surgery.

Research appears to be progressing, but at this time we do not yet have level 1 evidence to support their routine use.

Dr. Sokol reported that he owns stock in Pelvalon, and is a clinical adviser to that company. He also is a national principal investigator for American Medical Systems, and the recipient of research grants from Acell and several other companies.

Treatment of stress urinary incontinence

According to a 2004 article by Dr. Eric S. Rovner and Dr. Alan J. Wein, 200 different surgical procedures have been described to treat stress urinary incontinence (Rev. Urol. 2004;6(Suppl 3):S29-47). Two goals exist in such surgical procedures:

1. Urethra repositioning or stabilization of the urethra and bladder neck through creation of retropubic support that is impervious to intraabdominal pressure changes.

2. Augmentation of the ureteral resistance provided by the intrinsic sphincter unit, with or without impacting urethra and bladder neck support (sling vs. periurethral injectables, or a combination of the two).

Sling procedures were initially introduced almost a century ago and have recently become increasingly popular – in part, secondary to a decrease in associated morbidity. Unlike transabdominal or transvaginal urethropexy, a sling not only provides support to the vesicourethral junction, but also may create some aspect of urethral coaptation or compression.

Midurethral slings were introduced nearly 20 years ago. These procedures can be performed with a local anesthetic or with minimal regional anesthesia – thus, in an outpatient setting. In addition, midurethral slings are associated with decreased pain and postoperative convalescence.

I have asked Dr. Eric Russell Sokol to lead this state-of-the-art discussion on midurethral slings. Dr. Sokol is an associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology, associate professor of urology (by courtesy), and cochief of the division of urogynecology and pelvic reconstructive surgery at Stanford (Calif.) University. He has published many articles regarding urogynecology and minimally invasive surgery. Dr. Sokol has been awarded numerous teaching awards, and he is a reviewer for multiple prestigious, peer-reviewed journals. It is a pleasure and an honor to welcome Dr. Sokol to this edition of Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery, the second installment on urinary incontinence.

Dr. Miller is clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, immediate past president of the International Society for Gynecologic Endoscopy (ISGE), and a past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in private practice in Naperville, Ill., and Schaumburg, Ill.; the director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery and the director of the AAGL/SRS fellowship in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill.; and the medical editor of this column, Master Class. Dr. Miller is a consultant and on the speaker’s bureau for Ethicon.

According to a 2004 article by Dr. Eric S. Rovner and Dr. Alan J. Wein, 200 different surgical procedures have been described to treat stress urinary incontinence (Rev. Urol. 2004;6(Suppl 3):S29-47). Two goals exist in such surgical procedures:

1. Urethra repositioning or stabilization of the urethra and bladder neck through creation of retropubic support that is impervious to intraabdominal pressure changes.

2. Augmentation of the ureteral resistance provided by the intrinsic sphincter unit, with or without impacting urethra and bladder neck support (sling vs. periurethral injectables, or a combination of the two).

Sling procedures were initially introduced almost a century ago and have recently become increasingly popular – in part, secondary to a decrease in associated morbidity. Unlike transabdominal or transvaginal urethropexy, a sling not only provides support to the vesicourethral junction, but also may create some aspect of urethral coaptation or compression.

Midurethral slings were introduced nearly 20 years ago. These procedures can be performed with a local anesthetic or with minimal regional anesthesia – thus, in an outpatient setting. In addition, midurethral slings are associated with decreased pain and postoperative convalescence.

I have asked Dr. Eric Russell Sokol to lead this state-of-the-art discussion on midurethral slings. Dr. Sokol is an associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology, associate professor of urology (by courtesy), and cochief of the division of urogynecology and pelvic reconstructive surgery at Stanford (Calif.) University. He has published many articles regarding urogynecology and minimally invasive surgery. Dr. Sokol has been awarded numerous teaching awards, and he is a reviewer for multiple prestigious, peer-reviewed journals. It is a pleasure and an honor to welcome Dr. Sokol to this edition of Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery, the second installment on urinary incontinence.

Dr. Miller is clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, immediate past president of the International Society for Gynecologic Endoscopy (ISGE), and a past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in private practice in Naperville, Ill., and Schaumburg, Ill.; the director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery and the director of the AAGL/SRS fellowship in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill.; and the medical editor of this column, Master Class. Dr. Miller is a consultant and on the speaker’s bureau for Ethicon.

According to a 2004 article by Dr. Eric S. Rovner and Dr. Alan J. Wein, 200 different surgical procedures have been described to treat stress urinary incontinence (Rev. Urol. 2004;6(Suppl 3):S29-47). Two goals exist in such surgical procedures:

1. Urethra repositioning or stabilization of the urethra and bladder neck through creation of retropubic support that is impervious to intraabdominal pressure changes.

2. Augmentation of the ureteral resistance provided by the intrinsic sphincter unit, with or without impacting urethra and bladder neck support (sling vs. periurethral injectables, or a combination of the two).

Sling procedures were initially introduced almost a century ago and have recently become increasingly popular – in part, secondary to a decrease in associated morbidity. Unlike transabdominal or transvaginal urethropexy, a sling not only provides support to the vesicourethral junction, but also may create some aspect of urethral coaptation or compression.

Midurethral slings were introduced nearly 20 years ago. These procedures can be performed with a local anesthetic or with minimal regional anesthesia – thus, in an outpatient setting. In addition, midurethral slings are associated with decreased pain and postoperative convalescence.

I have asked Dr. Eric Russell Sokol to lead this state-of-the-art discussion on midurethral slings. Dr. Sokol is an associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology, associate professor of urology (by courtesy), and cochief of the division of urogynecology and pelvic reconstructive surgery at Stanford (Calif.) University. He has published many articles regarding urogynecology and minimally invasive surgery. Dr. Sokol has been awarded numerous teaching awards, and he is a reviewer for multiple prestigious, peer-reviewed journals. It is a pleasure and an honor to welcome Dr. Sokol to this edition of Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery, the second installment on urinary incontinence.

Dr. Miller is clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, immediate past president of the International Society for Gynecologic Endoscopy (ISGE), and a past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in private practice in Naperville, Ill., and Schaumburg, Ill.; the director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery and the director of the AAGL/SRS fellowship in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill.; and the medical editor of this column, Master Class. Dr. Miller is a consultant and on the speaker’s bureau for Ethicon.

Master Class: Obesity

Obesity not only increases a patient’s lifetime risk of numerous chronic conditions, such as diabetes, heart disease and kidney disease, but it also is a major health issue during pregnancy. Women who are obese in pregnancy have a significantly higher chance of developing adverse perinatal outcomes and experiencing various complications that affect both their health and that of their babies.

With an ever-increasing population of overweight and obese women of reproductive age, as key caregivers for women, we must reexamine our approaches and do much more than microfocusing on a woman’s pre- and postdelivery health. We must play a more active role in helping our patients establish and maintain a healthy lifestyle – one that will help ward off and reduce the incidence of this concerning condition.

Over the previous two Master Class installments on obstetrics, we discussed the extent of the obesity epidemic and its link to diabetes, the alarming number of infants, children, and adolescents who are obese, and the implications of these societal and medical trends for ob.gyns.

In the July Master Class, we discussed the importance of appropriately counseling patients on healthy weight gain and physical activity in pregnancy. Because ob.gyns. may be the only health care professionals that many women may see, it is becoming more important that we help our patients and their children attain and maintain positive health and well-being.

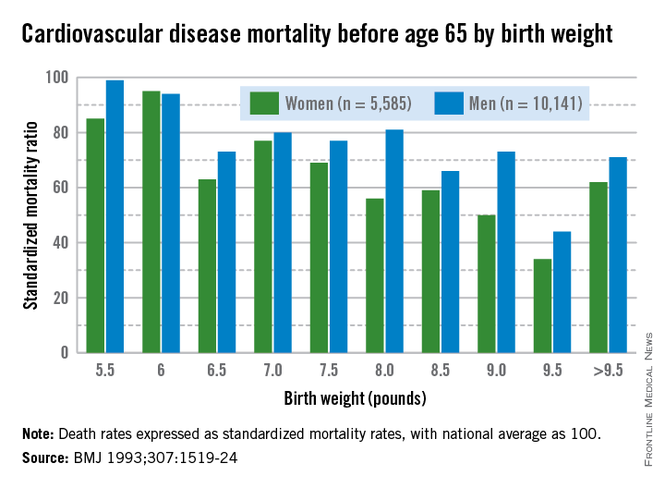

In our September installment, Dr. Thomas R. Moore looked at obesity trends through the lens of the Barker Hypothesis, which got us thinking more than 3 decades ago about the role of intrauterine environment in short- and long-term health of offspring. Dr. Moore discussed how obesity in pregnancy appears to program offspring for downstream cardiovascular risk in adulthood.

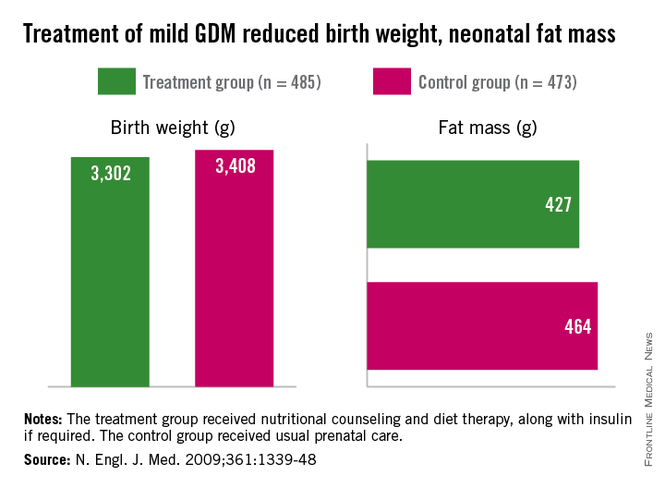

He told us that we must not only liberally treat gestational diabetes and optimize glucose control during pregnancy, but, most importantly, we also must emphasize to women the importance of having healthy weights at the time of conception.

This month’s Master Class examines this latter concept in more depth. Dr. Patrick Catalano, professor in the department of obstetrics and gynecology and director of the Center for Reproductive Health at MetroHealth Medical Center, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, has been at the forefront of research on the physiologic impact of obesity on the placenta and the fetus, and on approaches for addressing maternal obesity and improving perinatal outcomes.

Dr. Catalano explains here why weight loss before pregnancy appears to be important for preventing adverse perinatal outcomes and breaking the intergenerational transfer of obesity.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. Dr. Reece said he had no relevant financial disclosures. He is the medical editor of this column. Contact him at obnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

Obesity not only increases a patient’s lifetime risk of numerous chronic conditions, such as diabetes, heart disease and kidney disease, but it also is a major health issue during pregnancy. Women who are obese in pregnancy have a significantly higher chance of developing adverse perinatal outcomes and experiencing various complications that affect both their health and that of their babies.

With an ever-increasing population of overweight and obese women of reproductive age, as key caregivers for women, we must reexamine our approaches and do much more than microfocusing on a woman’s pre- and postdelivery health. We must play a more active role in helping our patients establish and maintain a healthy lifestyle – one that will help ward off and reduce the incidence of this concerning condition.

Over the previous two Master Class installments on obstetrics, we discussed the extent of the obesity epidemic and its link to diabetes, the alarming number of infants, children, and adolescents who are obese, and the implications of these societal and medical trends for ob.gyns.

In the July Master Class, we discussed the importance of appropriately counseling patients on healthy weight gain and physical activity in pregnancy. Because ob.gyns. may be the only health care professionals that many women may see, it is becoming more important that we help our patients and their children attain and maintain positive health and well-being.

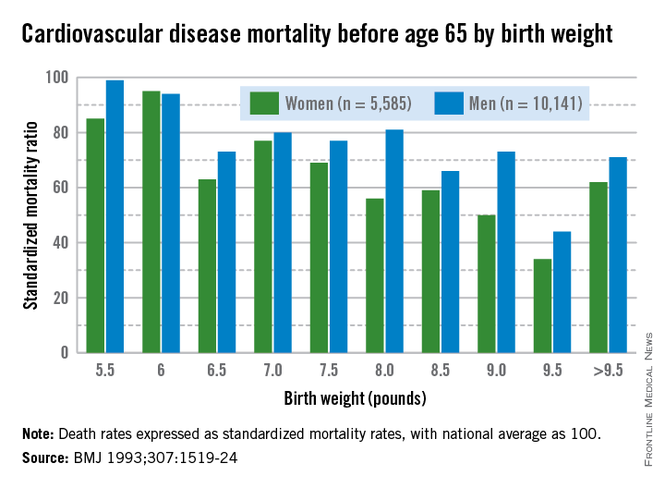

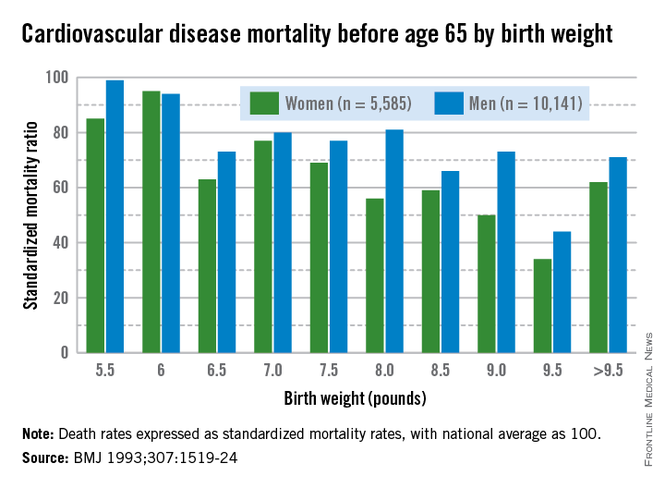

In our September installment, Dr. Thomas R. Moore looked at obesity trends through the lens of the Barker Hypothesis, which got us thinking more than 3 decades ago about the role of intrauterine environment in short- and long-term health of offspring. Dr. Moore discussed how obesity in pregnancy appears to program offspring for downstream cardiovascular risk in adulthood.

He told us that we must not only liberally treat gestational diabetes and optimize glucose control during pregnancy, but, most importantly, we also must emphasize to women the importance of having healthy weights at the time of conception.

This month’s Master Class examines this latter concept in more depth. Dr. Patrick Catalano, professor in the department of obstetrics and gynecology and director of the Center for Reproductive Health at MetroHealth Medical Center, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, has been at the forefront of research on the physiologic impact of obesity on the placenta and the fetus, and on approaches for addressing maternal obesity and improving perinatal outcomes.

Dr. Catalano explains here why weight loss before pregnancy appears to be important for preventing adverse perinatal outcomes and breaking the intergenerational transfer of obesity.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. Dr. Reece said he had no relevant financial disclosures. He is the medical editor of this column. Contact him at obnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

Obesity not only increases a patient’s lifetime risk of numerous chronic conditions, such as diabetes, heart disease and kidney disease, but it also is a major health issue during pregnancy. Women who are obese in pregnancy have a significantly higher chance of developing adverse perinatal outcomes and experiencing various complications that affect both their health and that of their babies.

With an ever-increasing population of overweight and obese women of reproductive age, as key caregivers for women, we must reexamine our approaches and do much more than microfocusing on a woman’s pre- and postdelivery health. We must play a more active role in helping our patients establish and maintain a healthy lifestyle – one that will help ward off and reduce the incidence of this concerning condition.

Over the previous two Master Class installments on obstetrics, we discussed the extent of the obesity epidemic and its link to diabetes, the alarming number of infants, children, and adolescents who are obese, and the implications of these societal and medical trends for ob.gyns.

In the July Master Class, we discussed the importance of appropriately counseling patients on healthy weight gain and physical activity in pregnancy. Because ob.gyns. may be the only health care professionals that many women may see, it is becoming more important that we help our patients and their children attain and maintain positive health and well-being.

In our September installment, Dr. Thomas R. Moore looked at obesity trends through the lens of the Barker Hypothesis, which got us thinking more than 3 decades ago about the role of intrauterine environment in short- and long-term health of offspring. Dr. Moore discussed how obesity in pregnancy appears to program offspring for downstream cardiovascular risk in adulthood.

He told us that we must not only liberally treat gestational diabetes and optimize glucose control during pregnancy, but, most importantly, we also must emphasize to women the importance of having healthy weights at the time of conception.

This month’s Master Class examines this latter concept in more depth. Dr. Patrick Catalano, professor in the department of obstetrics and gynecology and director of the Center for Reproductive Health at MetroHealth Medical Center, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, has been at the forefront of research on the physiologic impact of obesity on the placenta and the fetus, and on approaches for addressing maternal obesity and improving perinatal outcomes.

Dr. Catalano explains here why weight loss before pregnancy appears to be important for preventing adverse perinatal outcomes and breaking the intergenerational transfer of obesity.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. Dr. Reece said he had no relevant financial disclosures. He is the medical editor of this column. Contact him at obnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

Timing of lifestyle interventions for obesity

Obesity has become so pervasive that it is now considered a major health concern during pregnancy. Almost 56% of women aged 20-39 years in the United States are overweight or obese, based on the World Health Organization’s criteria for body mass index (BMI) and data from the 2009-2010 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). Moreover, 7.5% of women in this age group are morbidly obese, with a body mass index (BMI) greater than 40 kg/m2 (JAMA 2012;307:491-7).

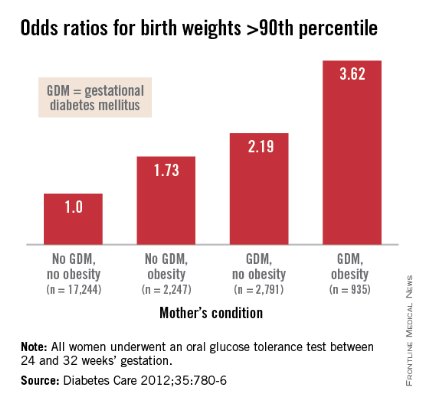

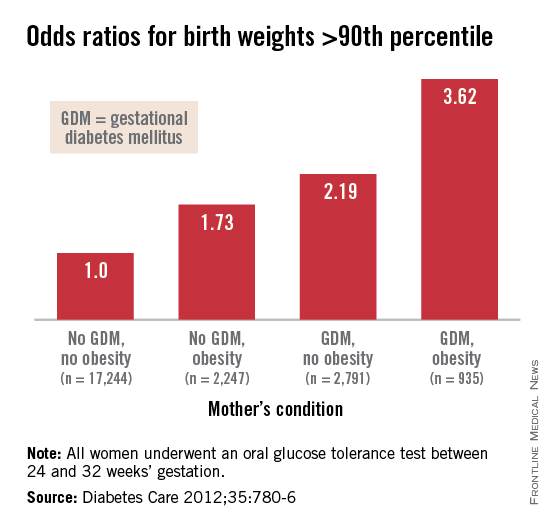

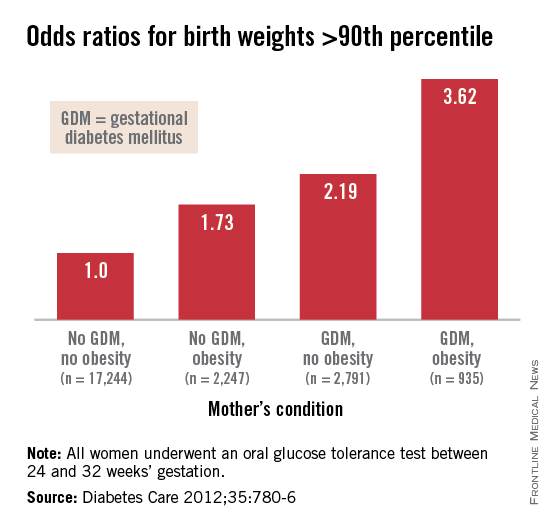

Obesity in pregnancy not only increases the risk of spontaneous abortions and congenital anomalies, it also increases the risk of gestational diabetes (GDM), hypertensive disorders, and other metabolic complications that affect both the mother and fetus.

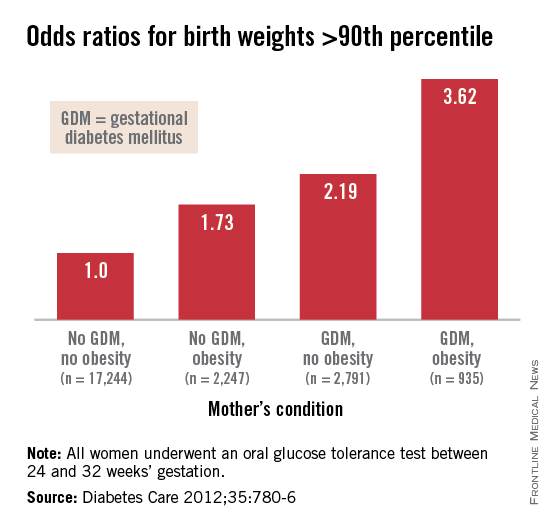

Of much concern is the increased risk of fetal overgrowth and long-term health consequences for children of obese mothers. Obesity in early pregnancy has been shown to more than double the risk of obesity in the offspring, which in turn puts these children at risk for developing the metabolic syndrome – and, as Dr. Thomas Moore pointed out in September’s Master Class – appears to program these offspring for downstream cardiovascular risk in adulthood.

Mean term birth weights have risen in the United States during the past several decades. In Cleveland, we have seen a significant 116 g increase in mean term birth weight since 1975; this increase encompasses weights from the 5th to the 95th percentiles. Even more concerning is our finding that the ponderal index in our neonatal population has increased because of decreased fetal length over the last decade.

Some recent studies have suggested that the increase in birth weight in the United States has reached a plateau, but our analyses of national trends suggest that such change is secondary to factors such as earlier gestational age of delivery. Concurrently, an alarming number of children and adolescents – 17% of those aged 2-19 years, according to the 2009-2010 NHANES data – are overweight or obese (JAMA 2012;307:483-90).

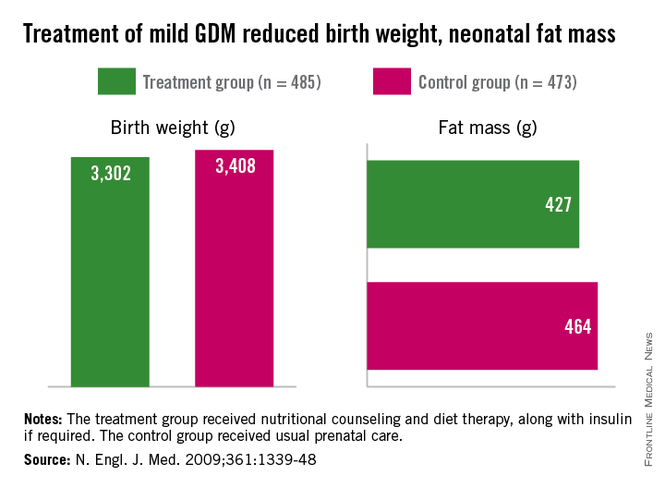

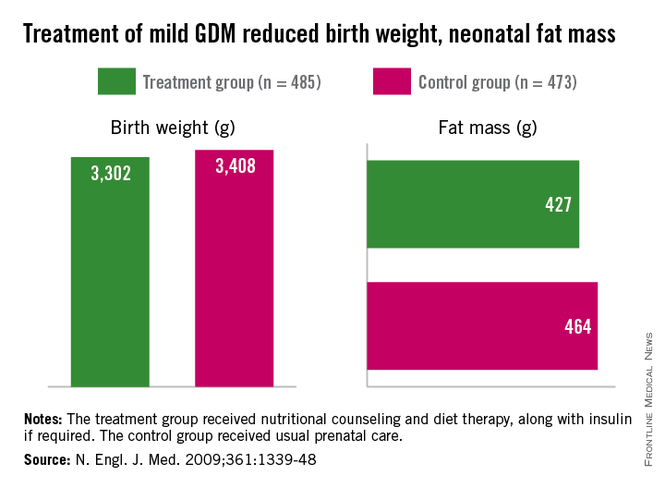

How to best treat obesity for improved maternal and fetal health has thus become a focus of research. Studies on lifestyle interventions for obese women during pregnancy have aimed to prevent excessive gestational weight gain and decrease adverse perinatal outcomes – mainly macrosomia, GDM, and hypertensive disorders.

However, the results of this recent body of research have been disappointing. Lifestyle interventions initiated during pregnancy have had only limited success in improving perinatal outcomes. The research tells us that while we may be able to reduce excessive gestational weight gain, it is unlikely that we will be successful in reducing fetal overgrowth, GDM, or preeclampsia in obese women.

Moreover, other studies show that it is a high pregravid BMI – not excessive gestational weight gain or the development of GDM – that plays the biggest role in fetal overgrowth and fetal adiposity.

A paradigm shift is in order. We must think about lifestyle intervention and weight loss before pregnancy, when the woman’s metabolic condition can be improved in time to minimize adverse perinatal metabolic outcomes and to maximize metabolic benefits relating to fetal body composition and metabolism.

Role of prepregnancy BMI

In 2008, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) and National Research Council reexamined 1990 guidelines for gestational weight gain. They concluded that excessive weight gain in pregnancy was a primary contributor to the development of obesity in women. In fact, according to the 2009 IOM report, “Weight Gain During Pregnancy: Reexamining the Guidelines” (Washington: National Academy Press, 2009), 38% of normal weight, 63% of overweight, and 46% of obese women had gained weight in excess of the earlier guidelines.

Helping our patients to gain within the guidelines is important. Excessive gestational weight gain is a primary risk factor for maternal postpartum weight retention, which increases the risk for maternal obesity in a subsequent pregnancy. It also has been associated with a modest increased risk of preterm birth and development of type 2 diabetes.

Interestingly, however, high gestational weight gain has not been related to an increased risk of fetal overgrowth or macrosomia in many obese women. Increased gestational weight gain is a greater risk for fetal overgrowth in women who are of normal weight prior to pregnancy (J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012;97:3648-54).

Our research has found that in overweight and obese women, it is maternal pregravid BMI – and not gestational weight gain – that presents the greatest risk for fetal macrosomia, and more specifically, the greatest risk for fetal obesity. Even when glucose tolerance levels are normal, overweight and obese women have neonates who are heavier and who have significant increases in the percentage of body fat and fat mass (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2006;195:1100-3).

In an 8-year prospective study of the perinatal risk factors associated with childhood obesity, we similarly found that maternal pregravid BMI – independent of maternal glucose status or gestational weight gain – was the strongest predictor of childhood obesity and metabolic dysfunction (Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009;90:1303-13).

Other studies have teased apart the roles of maternal obesity and GDM in long-term health of offspring. This work has found that maternal obesity during pregnancy is associated with metabolic syndrome in the offspring and an increased risk of type 2 diabetes in youth, independent of maternal diabetes during pregnancy. A recent meta-analysis also reported that, although maternal diabetes is associated with an increased BMI z score, this was no longer significant after adjustments were made for prepregnancy BMI (Diabetologia 2011;54:1957-66).

Maternal pregravid obesity, therefore, is not only a risk factor for neonatal adiposity at birth, but also for the longer-term risk of obesity and metabolic dysfunction in the offspring – independent of maternal GDM or excessive gestational weight gain.

Interventions in Pregnancy

Numerous prospective trials have examined lifestyle interventions for obese women during pregnancy. One randomized controlled study of a low glycemic index diet in pregnancy (coined the ROLO study) involved 800 women in Ireland who had previously delivered an infant weighting greater than 4,000 g. Women were randomized to receive the restricted diet or no intervention at 13 weeks. Despite a decrease in gestational weight gain in the intervention group, there were no differences in birth weight, birth weight percentile, ponderal index, or macrosomia between the two groups (BMJ 2012;345:e5605).

Another randomized controlled trial reported by a Danish group involved an intervention that consisted of dietary guidance, free membership in a fitness center, and personal coaching initiated between 10 and 14 weeks of gestation. There was a decrease in gestational weight gain in the intervention group, but paradoxically, the infants in the intervention group also had significantly higher birth weight, compared with controls (Diabetes Care 2011;34:2502-7).

Additionally, there have been at least five meta-analyses published in the past 2 years looking at lifestyle interventions during pregnancy. All have concluded that interventions initiated during pregnancy have limited success in reducing excessive gestational weight gain but not necessarily to within the IOM guidelines. The literature contains scant evidence to support further benefits for infant or maternal health (in other words, fetal overgrowth, GDM, or hypertensive disorders).

A recent Cochrane review also concluded that the results of several randomized controlled trials suggest no significant difference in GDM incidence between women receiving exercise intervention versus routine care.

Just this year, three additional randomized controlled trials of lifestyle interventions during pregnancy were published. Only one, the Treatment of Obese Pregnant Women (TOP) study, showed a modest effect in decreasing gestational weight gain. None found a reduction in GDM or fetal overgrowth.

Focus on prepregnancy

Obesity is an inflammatory condition that increases the risk of insulin resistance, impaired beta-cell function, and abnormal adiponectin concentrations. In pregnancy, maternal obesity and hyperinsulinemia can affect placental growth and gene expression.

We have studied lean and obese women recruited prior to a planned pregnancy, as well as lean and obese women scheduled for elective pregnancy termination in the first trimester. Our research, some of which we reported recently in the American Journal of Physiology , has shown increased expression of lipogenic and inflammatory genes in maternal adipose tissue and in the placenta of obese women in the early first trimester, before any phenotypic change becomes apparent (Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012;303:e832-40).

Specifically, hyperinsulinemia and/or defective insulin action in obese women appears to affect the placental programming of genes relating to adipokine expression and lipid metabolism, as well as mitrochondrial function. Altered inflammatory and lipid pathways affect the availability of nutrients for the fetus and, consequently, the size and body composition of the fetus. Fetal overgrowth and neonatal adiposity can result.

In addition, our research has shown that obese women have decreased insulin suppression of lipolysis in white adipose tissue, which during pregnancy results in improved lipid availability for fetal fat accretion and lipotoxicity.

When interventions aimed at weight loss and improved insulin sensitivity are undertaken before pregnancy or in the period between pregnancies, we have the opportunity to increase fat oxidation and reduce oxidative stress in early pregnancy. We also may be able to limit placental inflammation and favorably affect placental growth and gene expression. By the second trimester, our research suggests, gene expression in the placenta and early molecular changes in the white adipose tissue have already been programmed and cannot be reversed (Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012;303:e832-40).

In studies by our group and others of interpregnancy weight loss or gain, interpregnancy weight loss has been associated with a lower risk of large-for-gestational-age (LGA) infants, whereas interpregnancy weight gain has been associated with an increased risk of LGA. Preliminary work from our group shows that the decrease in birth weight involves primarily fat and not lean mass.

The 2009 IOM guidelines support weight loss before pregnancy and state that overweight women should receive individual preconceptional counseling to improve diet quality, increase physical activity, and normalize weight. Multifaceted interventions do work: In obese nonpregnant individuals, lifestyle interventions, which include an exercise program, diet, and behavioral modification have been shown to be successful in improving insulin sensitivity, inflammation, and overall metabolic function.

According to the IOM report, preconceptional services aimed at achieving a healthy weight before conceiving will represent “a radical change to the care provided to obese women of childbearing age.” With continuing research and accumulating data, however, the concept is gaining traction as a viable paradigm for improving perinatal outcomes, with long-term benefits for both the mother and her baby.

Dr. Catalano reports that he has no disclosures relevant to this Master Class.

Obesity has become so pervasive that it is now considered a major health concern during pregnancy. Almost 56% of women aged 20-39 years in the United States are overweight or obese, based on the World Health Organization’s criteria for body mass index (BMI) and data from the 2009-2010 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). Moreover, 7.5% of women in this age group are morbidly obese, with a body mass index (BMI) greater than 40 kg/m2 (JAMA 2012;307:491-7).

Obesity in pregnancy not only increases the risk of spontaneous abortions and congenital anomalies, it also increases the risk of gestational diabetes (GDM), hypertensive disorders, and other metabolic complications that affect both the mother and fetus.

Of much concern is the increased risk of fetal overgrowth and long-term health consequences for children of obese mothers. Obesity in early pregnancy has been shown to more than double the risk of obesity in the offspring, which in turn puts these children at risk for developing the metabolic syndrome – and, as Dr. Thomas Moore pointed out in September’s Master Class – appears to program these offspring for downstream cardiovascular risk in adulthood.

Mean term birth weights have risen in the United States during the past several decades. In Cleveland, we have seen a significant 116 g increase in mean term birth weight since 1975; this increase encompasses weights from the 5th to the 95th percentiles. Even more concerning is our finding that the ponderal index in our neonatal population has increased because of decreased fetal length over the last decade.

Some recent studies have suggested that the increase in birth weight in the United States has reached a plateau, but our analyses of national trends suggest that such change is secondary to factors such as earlier gestational age of delivery. Concurrently, an alarming number of children and adolescents – 17% of those aged 2-19 years, according to the 2009-2010 NHANES data – are overweight or obese (JAMA 2012;307:483-90).

How to best treat obesity for improved maternal and fetal health has thus become a focus of research. Studies on lifestyle interventions for obese women during pregnancy have aimed to prevent excessive gestational weight gain and decrease adverse perinatal outcomes – mainly macrosomia, GDM, and hypertensive disorders.

However, the results of this recent body of research have been disappointing. Lifestyle interventions initiated during pregnancy have had only limited success in improving perinatal outcomes. The research tells us that while we may be able to reduce excessive gestational weight gain, it is unlikely that we will be successful in reducing fetal overgrowth, GDM, or preeclampsia in obese women.

Moreover, other studies show that it is a high pregravid BMI – not excessive gestational weight gain or the development of GDM – that plays the biggest role in fetal overgrowth and fetal adiposity.

A paradigm shift is in order. We must think about lifestyle intervention and weight loss before pregnancy, when the woman’s metabolic condition can be improved in time to minimize adverse perinatal metabolic outcomes and to maximize metabolic benefits relating to fetal body composition and metabolism.

Role of prepregnancy BMI

In 2008, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) and National Research Council reexamined 1990 guidelines for gestational weight gain. They concluded that excessive weight gain in pregnancy was a primary contributor to the development of obesity in women. In fact, according to the 2009 IOM report, “Weight Gain During Pregnancy: Reexamining the Guidelines” (Washington: National Academy Press, 2009), 38% of normal weight, 63% of overweight, and 46% of obese women had gained weight in excess of the earlier guidelines.

Helping our patients to gain within the guidelines is important. Excessive gestational weight gain is a primary risk factor for maternal postpartum weight retention, which increases the risk for maternal obesity in a subsequent pregnancy. It also has been associated with a modest increased risk of preterm birth and development of type 2 diabetes.

Interestingly, however, high gestational weight gain has not been related to an increased risk of fetal overgrowth or macrosomia in many obese women. Increased gestational weight gain is a greater risk for fetal overgrowth in women who are of normal weight prior to pregnancy (J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012;97:3648-54).

Our research has found that in overweight and obese women, it is maternal pregravid BMI – and not gestational weight gain – that presents the greatest risk for fetal macrosomia, and more specifically, the greatest risk for fetal obesity. Even when glucose tolerance levels are normal, overweight and obese women have neonates who are heavier and who have significant increases in the percentage of body fat and fat mass (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2006;195:1100-3).

In an 8-year prospective study of the perinatal risk factors associated with childhood obesity, we similarly found that maternal pregravid BMI – independent of maternal glucose status or gestational weight gain – was the strongest predictor of childhood obesity and metabolic dysfunction (Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009;90:1303-13).

Other studies have teased apart the roles of maternal obesity and GDM in long-term health of offspring. This work has found that maternal obesity during pregnancy is associated with metabolic syndrome in the offspring and an increased risk of type 2 diabetes in youth, independent of maternal diabetes during pregnancy. A recent meta-analysis also reported that, although maternal diabetes is associated with an increased BMI z score, this was no longer significant after adjustments were made for prepregnancy BMI (Diabetologia 2011;54:1957-66).

Maternal pregravid obesity, therefore, is not only a risk factor for neonatal adiposity at birth, but also for the longer-term risk of obesity and metabolic dysfunction in the offspring – independent of maternal GDM or excessive gestational weight gain.

Interventions in Pregnancy

Numerous prospective trials have examined lifestyle interventions for obese women during pregnancy. One randomized controlled study of a low glycemic index diet in pregnancy (coined the ROLO study) involved 800 women in Ireland who had previously delivered an infant weighting greater than 4,000 g. Women were randomized to receive the restricted diet or no intervention at 13 weeks. Despite a decrease in gestational weight gain in the intervention group, there were no differences in birth weight, birth weight percentile, ponderal index, or macrosomia between the two groups (BMJ 2012;345:e5605).

Another randomized controlled trial reported by a Danish group involved an intervention that consisted of dietary guidance, free membership in a fitness center, and personal coaching initiated between 10 and 14 weeks of gestation. There was a decrease in gestational weight gain in the intervention group, but paradoxically, the infants in the intervention group also had significantly higher birth weight, compared with controls (Diabetes Care 2011;34:2502-7).

Additionally, there have been at least five meta-analyses published in the past 2 years looking at lifestyle interventions during pregnancy. All have concluded that interventions initiated during pregnancy have limited success in reducing excessive gestational weight gain but not necessarily to within the IOM guidelines. The literature contains scant evidence to support further benefits for infant or maternal health (in other words, fetal overgrowth, GDM, or hypertensive disorders).

A recent Cochrane review also concluded that the results of several randomized controlled trials suggest no significant difference in GDM incidence between women receiving exercise intervention versus routine care.

Just this year, three additional randomized controlled trials of lifestyle interventions during pregnancy were published. Only one, the Treatment of Obese Pregnant Women (TOP) study, showed a modest effect in decreasing gestational weight gain. None found a reduction in GDM or fetal overgrowth.

Focus on prepregnancy

Obesity is an inflammatory condition that increases the risk of insulin resistance, impaired beta-cell function, and abnormal adiponectin concentrations. In pregnancy, maternal obesity and hyperinsulinemia can affect placental growth and gene expression.

We have studied lean and obese women recruited prior to a planned pregnancy, as well as lean and obese women scheduled for elective pregnancy termination in the first trimester. Our research, some of which we reported recently in the American Journal of Physiology , has shown increased expression of lipogenic and inflammatory genes in maternal adipose tissue and in the placenta of obese women in the early first trimester, before any phenotypic change becomes apparent (Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012;303:e832-40).