User login

Diabesity – Fattening the U.S. health care budget

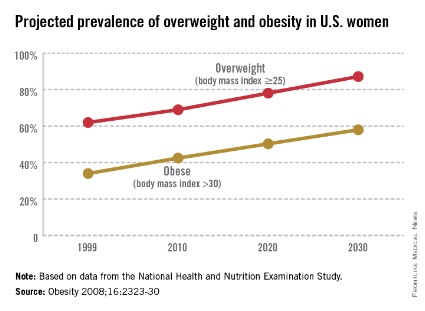

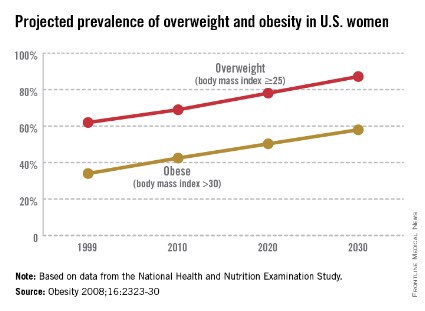

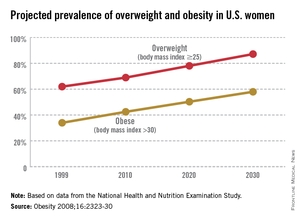

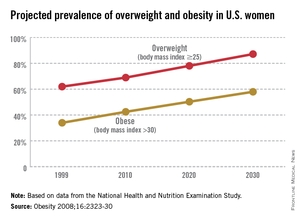

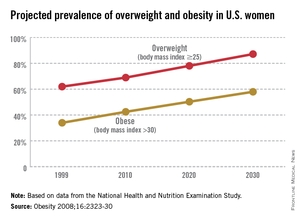

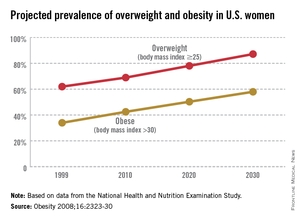

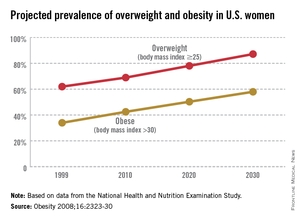

The world is not only getting older and warmer, but it’s getting heavier and more unfit each year. According to the World Health Organization’s most recent data, more than 1.4 billion adults were overweight in 2008, and 500 million of these adults were obese. In 2012, more than 40 million young children were overweight or obese. Diabetes, a disorder closely linked with obesity, affects about 347 million people worldwide – approximately ten times more people than those with HIV/AIDS. Although the number of AIDS-related deaths has steadily decreased over the last decade, even in developing countries, the number of diabetes-related deaths has steadily increased. The WHO projects that diabetes-related deaths will double by 2030, making it the seventh leading cause of death worldwide. In the United States, diabetes already is the seventh leading cause of death.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, obesity-related diseases cost $147 billion annually, a number which dwarfs the health care costs associated with smoking ($96 billion). In addition to the link with type 2 diabetes, there are strong links between obesity and heart disease, kidney disease, depression, and hypertension. From 1987 to 2007, obesity was estimated to have caused more than a 20% increase in total health care spending.

The American Diabetes Association estimates that people diagnosed with diabetes have average yearly medical expenditures of over $13,000, which is over two times higher than the expenditures of a person without diagnosed diabetes. The 2012 estimated annual cost of care for diagnosed diabetes was $245 billion, which includes $176 billion in direct medical costs and $69 billion in reduced productivity (Diabetes Care 2013 [doi:10.2337/dc12-2625]). These figures, while staggering, do not include projected expenditures for people who have yet to receive a diabetes diagnosis.

The federal government has chosen to take dramatic steps to help Americans lose weight. Since 2011, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services has covered screening and intensive behavioral therapy for obesity by primary care physicians during office visits or outpatient hospital care. Additionally, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) now requires insurance companies to help overweight and obese patients try to lose weight and be healthier. The 2012 Institute of Medicine (IOM) report, Accelerating Progress in Obesity Prevention: Solving the Weight of the Nation also has made major recommendations for health care practitioners, schools, and the food and beverage industry to take a more active part in improving our overall health.

Simple steps make a big impact on health

Despite the daunting – and perhaps somewhat disheartening – statistics on obesity and diabetes in the United States and around the world, research has shown that small steps to achieving a healthy weight and maintaining an active lifestyle can make a dramatic difference on the course of a person’s life. According to the Department of Agriculture, healthier diets could prevent about $71 billion in yearly health care costs, lost productivity, and premature deaths. This number is staggering, when you consider that the change could be as small as choosing a salad instead of fries for a side dish.

Medical research backs up the well-worn adage that "an apple a day keeps the doctor away." The Diabetes Prevention Program study, conducted in the early 2000s, found that lifestyle changes, such as getting more exercise and eating a balanced diet, had a major impact on whether a patient who is overweight with prediabetes developed type 2 diabetes (N. Engl. J. Med. 2002;346:393-403).

Lifestyle changes can also reduce the onset of diabetes in high-risk groups such as Asian Indians, where the incidence of diabetes is the highest in the world. The Indian Diabetes Prevention Programme showed that weight loss and healthy eating reduced the incidence of type 2 diabetes in this population at a rate similar to the use of metformin, one of the most common oral antidiabetic drugs (Diabetologia 2006;49:289-97).

The 16th U.S. Surgeon General, David Satcher, M.D., Ph.D., is famous for giving his "Prescription for Great Health" when he addresses colleges and universities, which includes not smoking, staying away from illicit drug use, and abstaining from unsafe sex. Importantly, the first two key points of his "prescription" are exercising at least five times a week for 30 minutes and eating at least five servings of fruits and vegetables daily. Again, very simple recommendations, but his advice has lasting and profound ramifications.

Do obstetrician/gynecologists have a role?

As ob.gyns., we always have played an incredibly critical role in maintaining the health and well-being of our patients. Now, more than ever, we have a significant opportunity to set our patients on a path to better eating, incorporating exercise into their daily routines and passing down these good habits to their children.

In the "old days," the ob.gyn. focused on a limited period in a patient’s life. Perhaps we only saw a patient for annual exams and then for a more intense time prior to and during pregnancy, and then for a checkup post partum where we may have examined our patients only for complications of the pregnancy and delivery and not much more. Although we may have included some counseling on maintaining a healthy pregnancy, many of us relied on a patient’s primary care physician to provide ongoing support.

Today, however, we must take a more active role in helping our patients establish and maintain a healthy lifestyle. Despite the increased insurance coverage under the ACA and the expansion of Medicaid, a woman’s ob.gyn. may be the only health care practitioner she will see on a routine basis. Many women do not visit a general practitioner for routine physical examinations, but women will see their ob.gyn. for regular exams. We can use these annual or biannual office visits to help women set goals to live a healthy life, approaching each patient as a whole person who needs comprehensive care throughout her reproductive life and beyond.

For patients who are overweight or obese, we may focus on helping them reduce their body mass index and blood pressure and encourage them to stay fit. We also should do everything we can to ensure that if a woman has had gestational diabetes, she’s doing what she can to reduce her risk of developing type 2 diabetes after pregnancy. For these patients, we should consider testing their blood glucose every 1-2 years during the annual checkup.

Healthy weight in pregnancy: to gain or to lose?

Whether or not an ob.gyn. practice implements a screening program and more intensive obesity and diabetes counseling, we all will face the same question: How much weight should my patient gain to have a healthy baby? Interestingly, in the first half of the 20th century, ob.gyns. were discouraged from recommending that their pregnant patients gain very much weight. Indeed, the 13th edition of "Williams Obstetrics" (New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1966, p. 326) stated that obstetricians should limit their patients from gaining more than 25 pounds during gestation, and that the ideal weight gain was 15 pounds.

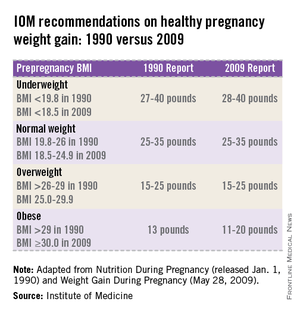

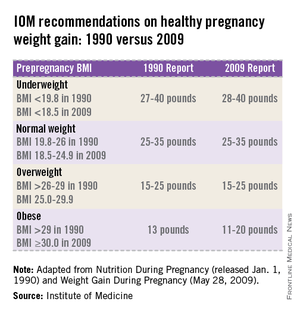

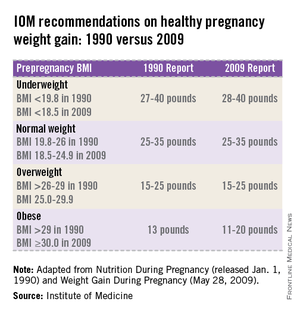

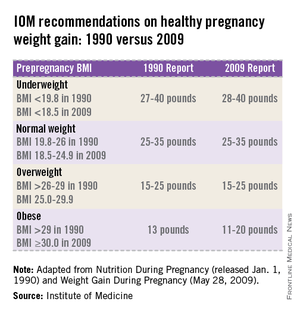

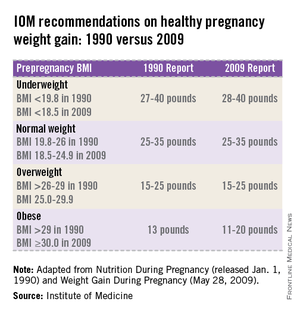

This guidance was called into question by a 1970 National Academy of Sciences report, "Maternal Nutrition and the Course of Pregnancy," which indicated a strong link between infant mortality and low maternal pregnancy weight. Further evidence suggested a need for new standards and, in 1990, the IOM issued recommendations on women’s nutrition during pregnancy (Nutrition During Pregnancy, Weight Gain and Nutrient Supplements. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press, 1990). (See table.)

Americans consume 31% more calories today than they did 40 years ago. Because of this, a woman’s need to gain weight to improve the outcome of her pregnancy is significantly reduced. The calories that many people include in their diets often come from high-fat, sodium-loaded, processed foods. We also have become a more sedentary society, spending our days at a computer, browsing the internet, watching TV, and opting to drive rather than to walk. Taking these factors into account, revising the recommendations for weight gain seemed crucial. In 2009, the IOM revised its guidance on healthy weight gain in pregnancy, and these ranges are currently widely accepted by obstetricians today (iom.edu/Reports/2009/Weight-Gain-During-Pregnancy-Reexamining-the-Guidelines.aspx). (See table.)

With the obesity and diabetes epidemics on the rise, we may need to update the 2009 IOM guidelines again – and very soon. Isolated studies have indicated that, for women who are severely obese, moderate weight loss during pregnancy may improve pregnancy outcomes. These findings remain controversial, but the "heavy" burden of diabetes and obesity on the U.S. health care system in general, and the need to reduce obstetrical complications that accompany deliveries in patients who are overweight or obese and diabetic, means that we as a community may need to reexamine our practices and approaches much more closely.

"Food" for thought

We all know of patients who, once they become pregnant, begin justifying a greater intake of food as "eating for two." Many women may use their pregnancy as an excuse to overindulge in unhealthy foods or to forgo the gym and other regular exercise regimens. Recommending basic steps to change a patient’s lifestyle can make an incredible difference in improving maternal and fetal health outcomes.

Summary recommendations for healthy pregnancy

• A low-glycemic diet, combined with moderate exercise, can reduce or eliminate many of the negative consequences of obesity on pregnant women and their babies.

• Proper weight management during pregnancy can improve birth outcomes.

• Weight loss during pregnancy is not recommended, except, potentially, for morbidly obese women (BMI greater than 40).

• For women who are normal weight, overweight or obese, leading healthy lifestyles can greatly improve maternal and fetal health outcomes. These include physical exercise, balanced diet, and weight loss, in combination with medication in some cases.

• It is never too late to begin healthy habits!

If we microfocus only on a woman’s predelivery and postdelivery health, then we’re losing a big opportunity to improve her whole self and prevent future health complications during and outside of pregnancy. The good news for ob.gyns. is that this complex problem has a simple, well-documented, and proven solution.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. Dr. Reece said he had no relevant financial disclosures. He is the medical editor of this column. Contact him at obnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

The world is not only getting older and warmer, but it’s getting heavier and more unfit each year. According to the World Health Organization’s most recent data, more than 1.4 billion adults were overweight in 2008, and 500 million of these adults were obese. In 2012, more than 40 million young children were overweight or obese. Diabetes, a disorder closely linked with obesity, affects about 347 million people worldwide – approximately ten times more people than those with HIV/AIDS. Although the number of AIDS-related deaths has steadily decreased over the last decade, even in developing countries, the number of diabetes-related deaths has steadily increased. The WHO projects that diabetes-related deaths will double by 2030, making it the seventh leading cause of death worldwide. In the United States, diabetes already is the seventh leading cause of death.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, obesity-related diseases cost $147 billion annually, a number which dwarfs the health care costs associated with smoking ($96 billion). In addition to the link with type 2 diabetes, there are strong links between obesity and heart disease, kidney disease, depression, and hypertension. From 1987 to 2007, obesity was estimated to have caused more than a 20% increase in total health care spending.

The American Diabetes Association estimates that people diagnosed with diabetes have average yearly medical expenditures of over $13,000, which is over two times higher than the expenditures of a person without diagnosed diabetes. The 2012 estimated annual cost of care for diagnosed diabetes was $245 billion, which includes $176 billion in direct medical costs and $69 billion in reduced productivity (Diabetes Care 2013 [doi:10.2337/dc12-2625]). These figures, while staggering, do not include projected expenditures for people who have yet to receive a diabetes diagnosis.

The federal government has chosen to take dramatic steps to help Americans lose weight. Since 2011, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services has covered screening and intensive behavioral therapy for obesity by primary care physicians during office visits or outpatient hospital care. Additionally, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) now requires insurance companies to help overweight and obese patients try to lose weight and be healthier. The 2012 Institute of Medicine (IOM) report, Accelerating Progress in Obesity Prevention: Solving the Weight of the Nation also has made major recommendations for health care practitioners, schools, and the food and beverage industry to take a more active part in improving our overall health.

Simple steps make a big impact on health

Despite the daunting – and perhaps somewhat disheartening – statistics on obesity and diabetes in the United States and around the world, research has shown that small steps to achieving a healthy weight and maintaining an active lifestyle can make a dramatic difference on the course of a person’s life. According to the Department of Agriculture, healthier diets could prevent about $71 billion in yearly health care costs, lost productivity, and premature deaths. This number is staggering, when you consider that the change could be as small as choosing a salad instead of fries for a side dish.

Medical research backs up the well-worn adage that "an apple a day keeps the doctor away." The Diabetes Prevention Program study, conducted in the early 2000s, found that lifestyle changes, such as getting more exercise and eating a balanced diet, had a major impact on whether a patient who is overweight with prediabetes developed type 2 diabetes (N. Engl. J. Med. 2002;346:393-403).

Lifestyle changes can also reduce the onset of diabetes in high-risk groups such as Asian Indians, where the incidence of diabetes is the highest in the world. The Indian Diabetes Prevention Programme showed that weight loss and healthy eating reduced the incidence of type 2 diabetes in this population at a rate similar to the use of metformin, one of the most common oral antidiabetic drugs (Diabetologia 2006;49:289-97).

The 16th U.S. Surgeon General, David Satcher, M.D., Ph.D., is famous for giving his "Prescription for Great Health" when he addresses colleges and universities, which includes not smoking, staying away from illicit drug use, and abstaining from unsafe sex. Importantly, the first two key points of his "prescription" are exercising at least five times a week for 30 minutes and eating at least five servings of fruits and vegetables daily. Again, very simple recommendations, but his advice has lasting and profound ramifications.

Do obstetrician/gynecologists have a role?

As ob.gyns., we always have played an incredibly critical role in maintaining the health and well-being of our patients. Now, more than ever, we have a significant opportunity to set our patients on a path to better eating, incorporating exercise into their daily routines and passing down these good habits to their children.

In the "old days," the ob.gyn. focused on a limited period in a patient’s life. Perhaps we only saw a patient for annual exams and then for a more intense time prior to and during pregnancy, and then for a checkup post partum where we may have examined our patients only for complications of the pregnancy and delivery and not much more. Although we may have included some counseling on maintaining a healthy pregnancy, many of us relied on a patient’s primary care physician to provide ongoing support.

Today, however, we must take a more active role in helping our patients establish and maintain a healthy lifestyle. Despite the increased insurance coverage under the ACA and the expansion of Medicaid, a woman’s ob.gyn. may be the only health care practitioner she will see on a routine basis. Many women do not visit a general practitioner for routine physical examinations, but women will see their ob.gyn. for regular exams. We can use these annual or biannual office visits to help women set goals to live a healthy life, approaching each patient as a whole person who needs comprehensive care throughout her reproductive life and beyond.

For patients who are overweight or obese, we may focus on helping them reduce their body mass index and blood pressure and encourage them to stay fit. We also should do everything we can to ensure that if a woman has had gestational diabetes, she’s doing what she can to reduce her risk of developing type 2 diabetes after pregnancy. For these patients, we should consider testing their blood glucose every 1-2 years during the annual checkup.

Healthy weight in pregnancy: to gain or to lose?

Whether or not an ob.gyn. practice implements a screening program and more intensive obesity and diabetes counseling, we all will face the same question: How much weight should my patient gain to have a healthy baby? Interestingly, in the first half of the 20th century, ob.gyns. were discouraged from recommending that their pregnant patients gain very much weight. Indeed, the 13th edition of "Williams Obstetrics" (New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1966, p. 326) stated that obstetricians should limit their patients from gaining more than 25 pounds during gestation, and that the ideal weight gain was 15 pounds.

This guidance was called into question by a 1970 National Academy of Sciences report, "Maternal Nutrition and the Course of Pregnancy," which indicated a strong link between infant mortality and low maternal pregnancy weight. Further evidence suggested a need for new standards and, in 1990, the IOM issued recommendations on women’s nutrition during pregnancy (Nutrition During Pregnancy, Weight Gain and Nutrient Supplements. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press, 1990). (See table.)

Americans consume 31% more calories today than they did 40 years ago. Because of this, a woman’s need to gain weight to improve the outcome of her pregnancy is significantly reduced. The calories that many people include in their diets often come from high-fat, sodium-loaded, processed foods. We also have become a more sedentary society, spending our days at a computer, browsing the internet, watching TV, and opting to drive rather than to walk. Taking these factors into account, revising the recommendations for weight gain seemed crucial. In 2009, the IOM revised its guidance on healthy weight gain in pregnancy, and these ranges are currently widely accepted by obstetricians today (iom.edu/Reports/2009/Weight-Gain-During-Pregnancy-Reexamining-the-Guidelines.aspx). (See table.)

With the obesity and diabetes epidemics on the rise, we may need to update the 2009 IOM guidelines again – and very soon. Isolated studies have indicated that, for women who are severely obese, moderate weight loss during pregnancy may improve pregnancy outcomes. These findings remain controversial, but the "heavy" burden of diabetes and obesity on the U.S. health care system in general, and the need to reduce obstetrical complications that accompany deliveries in patients who are overweight or obese and diabetic, means that we as a community may need to reexamine our practices and approaches much more closely.

"Food" for thought

We all know of patients who, once they become pregnant, begin justifying a greater intake of food as "eating for two." Many women may use their pregnancy as an excuse to overindulge in unhealthy foods or to forgo the gym and other regular exercise regimens. Recommending basic steps to change a patient’s lifestyle can make an incredible difference in improving maternal and fetal health outcomes.

Summary recommendations for healthy pregnancy

• A low-glycemic diet, combined with moderate exercise, can reduce or eliminate many of the negative consequences of obesity on pregnant women and their babies.

• Proper weight management during pregnancy can improve birth outcomes.

• Weight loss during pregnancy is not recommended, except, potentially, for morbidly obese women (BMI greater than 40).

• For women who are normal weight, overweight or obese, leading healthy lifestyles can greatly improve maternal and fetal health outcomes. These include physical exercise, balanced diet, and weight loss, in combination with medication in some cases.

• It is never too late to begin healthy habits!

If we microfocus only on a woman’s predelivery and postdelivery health, then we’re losing a big opportunity to improve her whole self and prevent future health complications during and outside of pregnancy. The good news for ob.gyns. is that this complex problem has a simple, well-documented, and proven solution.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. Dr. Reece said he had no relevant financial disclosures. He is the medical editor of this column. Contact him at obnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

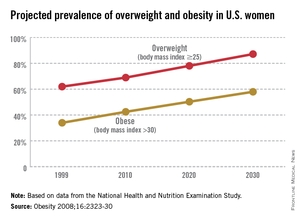

The world is not only getting older and warmer, but it’s getting heavier and more unfit each year. According to the World Health Organization’s most recent data, more than 1.4 billion adults were overweight in 2008, and 500 million of these adults were obese. In 2012, more than 40 million young children were overweight or obese. Diabetes, a disorder closely linked with obesity, affects about 347 million people worldwide – approximately ten times more people than those with HIV/AIDS. Although the number of AIDS-related deaths has steadily decreased over the last decade, even in developing countries, the number of diabetes-related deaths has steadily increased. The WHO projects that diabetes-related deaths will double by 2030, making it the seventh leading cause of death worldwide. In the United States, diabetes already is the seventh leading cause of death.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, obesity-related diseases cost $147 billion annually, a number which dwarfs the health care costs associated with smoking ($96 billion). In addition to the link with type 2 diabetes, there are strong links between obesity and heart disease, kidney disease, depression, and hypertension. From 1987 to 2007, obesity was estimated to have caused more than a 20% increase in total health care spending.

The American Diabetes Association estimates that people diagnosed with diabetes have average yearly medical expenditures of over $13,000, which is over two times higher than the expenditures of a person without diagnosed diabetes. The 2012 estimated annual cost of care for diagnosed diabetes was $245 billion, which includes $176 billion in direct medical costs and $69 billion in reduced productivity (Diabetes Care 2013 [doi:10.2337/dc12-2625]). These figures, while staggering, do not include projected expenditures for people who have yet to receive a diabetes diagnosis.

The federal government has chosen to take dramatic steps to help Americans lose weight. Since 2011, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services has covered screening and intensive behavioral therapy for obesity by primary care physicians during office visits or outpatient hospital care. Additionally, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) now requires insurance companies to help overweight and obese patients try to lose weight and be healthier. The 2012 Institute of Medicine (IOM) report, Accelerating Progress in Obesity Prevention: Solving the Weight of the Nation also has made major recommendations for health care practitioners, schools, and the food and beverage industry to take a more active part in improving our overall health.

Simple steps make a big impact on health

Despite the daunting – and perhaps somewhat disheartening – statistics on obesity and diabetes in the United States and around the world, research has shown that small steps to achieving a healthy weight and maintaining an active lifestyle can make a dramatic difference on the course of a person’s life. According to the Department of Agriculture, healthier diets could prevent about $71 billion in yearly health care costs, lost productivity, and premature deaths. This number is staggering, when you consider that the change could be as small as choosing a salad instead of fries for a side dish.

Medical research backs up the well-worn adage that "an apple a day keeps the doctor away." The Diabetes Prevention Program study, conducted in the early 2000s, found that lifestyle changes, such as getting more exercise and eating a balanced diet, had a major impact on whether a patient who is overweight with prediabetes developed type 2 diabetes (N. Engl. J. Med. 2002;346:393-403).

Lifestyle changes can also reduce the onset of diabetes in high-risk groups such as Asian Indians, where the incidence of diabetes is the highest in the world. The Indian Diabetes Prevention Programme showed that weight loss and healthy eating reduced the incidence of type 2 diabetes in this population at a rate similar to the use of metformin, one of the most common oral antidiabetic drugs (Diabetologia 2006;49:289-97).

The 16th U.S. Surgeon General, David Satcher, M.D., Ph.D., is famous for giving his "Prescription for Great Health" when he addresses colleges and universities, which includes not smoking, staying away from illicit drug use, and abstaining from unsafe sex. Importantly, the first two key points of his "prescription" are exercising at least five times a week for 30 minutes and eating at least five servings of fruits and vegetables daily. Again, very simple recommendations, but his advice has lasting and profound ramifications.

Do obstetrician/gynecologists have a role?

As ob.gyns., we always have played an incredibly critical role in maintaining the health and well-being of our patients. Now, more than ever, we have a significant opportunity to set our patients on a path to better eating, incorporating exercise into their daily routines and passing down these good habits to their children.

In the "old days," the ob.gyn. focused on a limited period in a patient’s life. Perhaps we only saw a patient for annual exams and then for a more intense time prior to and during pregnancy, and then for a checkup post partum where we may have examined our patients only for complications of the pregnancy and delivery and not much more. Although we may have included some counseling on maintaining a healthy pregnancy, many of us relied on a patient’s primary care physician to provide ongoing support.

Today, however, we must take a more active role in helping our patients establish and maintain a healthy lifestyle. Despite the increased insurance coverage under the ACA and the expansion of Medicaid, a woman’s ob.gyn. may be the only health care practitioner she will see on a routine basis. Many women do not visit a general practitioner for routine physical examinations, but women will see their ob.gyn. for regular exams. We can use these annual or biannual office visits to help women set goals to live a healthy life, approaching each patient as a whole person who needs comprehensive care throughout her reproductive life and beyond.

For patients who are overweight or obese, we may focus on helping them reduce their body mass index and blood pressure and encourage them to stay fit. We also should do everything we can to ensure that if a woman has had gestational diabetes, she’s doing what she can to reduce her risk of developing type 2 diabetes after pregnancy. For these patients, we should consider testing their blood glucose every 1-2 years during the annual checkup.

Healthy weight in pregnancy: to gain or to lose?

Whether or not an ob.gyn. practice implements a screening program and more intensive obesity and diabetes counseling, we all will face the same question: How much weight should my patient gain to have a healthy baby? Interestingly, in the first half of the 20th century, ob.gyns. were discouraged from recommending that their pregnant patients gain very much weight. Indeed, the 13th edition of "Williams Obstetrics" (New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1966, p. 326) stated that obstetricians should limit their patients from gaining more than 25 pounds during gestation, and that the ideal weight gain was 15 pounds.

This guidance was called into question by a 1970 National Academy of Sciences report, "Maternal Nutrition and the Course of Pregnancy," which indicated a strong link between infant mortality and low maternal pregnancy weight. Further evidence suggested a need for new standards and, in 1990, the IOM issued recommendations on women’s nutrition during pregnancy (Nutrition During Pregnancy, Weight Gain and Nutrient Supplements. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press, 1990). (See table.)

Americans consume 31% more calories today than they did 40 years ago. Because of this, a woman’s need to gain weight to improve the outcome of her pregnancy is significantly reduced. The calories that many people include in their diets often come from high-fat, sodium-loaded, processed foods. We also have become a more sedentary society, spending our days at a computer, browsing the internet, watching TV, and opting to drive rather than to walk. Taking these factors into account, revising the recommendations for weight gain seemed crucial. In 2009, the IOM revised its guidance on healthy weight gain in pregnancy, and these ranges are currently widely accepted by obstetricians today (iom.edu/Reports/2009/Weight-Gain-During-Pregnancy-Reexamining-the-Guidelines.aspx). (See table.)

With the obesity and diabetes epidemics on the rise, we may need to update the 2009 IOM guidelines again – and very soon. Isolated studies have indicated that, for women who are severely obese, moderate weight loss during pregnancy may improve pregnancy outcomes. These findings remain controversial, but the "heavy" burden of diabetes and obesity on the U.S. health care system in general, and the need to reduce obstetrical complications that accompany deliveries in patients who are overweight or obese and diabetic, means that we as a community may need to reexamine our practices and approaches much more closely.

"Food" for thought

We all know of patients who, once they become pregnant, begin justifying a greater intake of food as "eating for two." Many women may use their pregnancy as an excuse to overindulge in unhealthy foods or to forgo the gym and other regular exercise regimens. Recommending basic steps to change a patient’s lifestyle can make an incredible difference in improving maternal and fetal health outcomes.

Summary recommendations for healthy pregnancy

• A low-glycemic diet, combined with moderate exercise, can reduce or eliminate many of the negative consequences of obesity on pregnant women and their babies.

• Proper weight management during pregnancy can improve birth outcomes.

• Weight loss during pregnancy is not recommended, except, potentially, for morbidly obese women (BMI greater than 40).

• For women who are normal weight, overweight or obese, leading healthy lifestyles can greatly improve maternal and fetal health outcomes. These include physical exercise, balanced diet, and weight loss, in combination with medication in some cases.

• It is never too late to begin healthy habits!

If we microfocus only on a woman’s predelivery and postdelivery health, then we’re losing a big opportunity to improve her whole self and prevent future health complications during and outside of pregnancy. The good news for ob.gyns. is that this complex problem has a simple, well-documented, and proven solution.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. Dr. Reece said he had no relevant financial disclosures. He is the medical editor of this column. Contact him at obnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

Diabesity – Fattening the U.S. health care budget

The world is not only getting older and warmer, but it’s getting heavier and more unfit each year. According to the World Health Organization’s most recent data, more than 1.4 billion adults were overweight in 2008, and 500 million of these adults were obese. In 2012, more than 40 million young children were overweight or obese. Diabetes, a disorder closely linked with obesity, affects about 347 million people worldwide – approximately ten times more people than those with HIV/AIDS. Although the number of AIDS-related deaths has steadily decreased over the last decade, even in developing countries, the number of diabetes-related deaths has steadily increased. The WHO projects that diabetes-related deaths will double by 2030, making it the seventh leading cause of death worldwide. In the United States, diabetes already is the seventh leading cause of death.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, obesity-related diseases cost $147 billion annually, a number which dwarfs the health care costs associated with smoking ($96 billion). In addition to the link with type 2 diabetes, there are strong links between obesity and heart disease, kidney disease, depression, and hypertension. From 1987 to 2007, obesity was estimated to have caused more than a 20% increase in total health care spending.

The American Diabetes Association estimates that people diagnosed with diabetes have average yearly medical expenditures of over $13,000, which is over two times higher than the expenditures of a person without diagnosed diabetes. The 2012 estimated annual cost of care for diagnosed diabetes was $245 billion, which includes $176 billion in direct medical costs and $69 billion in reduced productivity (Diabetes Care 2013 [doi:10.2337/dc12-2625]). These figures, while staggering, do not include projected expenditures for people who have yet to receive a diabetes diagnosis.

The federal government has chosen to take dramatic steps to help Americans lose weight. Since 2011, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services has covered screening and intensive behavioral therapy for obesity by primary care physicians during office visits or outpatient hospital care. Additionally, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) now requires insurance companies to help overweight and obese patients try to lose weight and be healthier. The 2012 Institute of Medicine (IOM) report, Accelerating Progress in Obesity Prevention: Solving the Weight of the Nation also has made major recommendations for health care practitioners, schools, and the food and beverage industry to take a more active part in improving our overall health.

Simple steps make a big impact on health

Despite the daunting – and perhaps somewhat disheartening – statistics on obesity and diabetes in the United States and around the world, research has shown that small steps to achieving a healthy weight and maintaining an active lifestyle can make a dramatic difference on the course of a person’s life. According to the Department of Agriculture, healthier diets could prevent about $71 billion in yearly health care costs, lost productivity, and premature deaths. This number is staggering, when you consider that the change could be as small as choosing a salad instead of fries for a side dish.

Medical research backs up the well-worn adage that "an apple a day keeps the doctor away." The Diabetes Prevention Program study, conducted in the early 2000s, found that lifestyle changes, such as getting more exercise and eating a balanced diet, had a major impact on whether a patient who is overweight with prediabetes developed type 2 diabetes (N. Engl. J. Med. 2002;346:393-403).

Lifestyle changes can also reduce the onset of diabetes in high-risk groups such as Asian Indians, where the incidence of diabetes is the highest in the world. The Indian Diabetes Prevention Programme showed that weight loss and healthy eating reduced the incidence of type 2 diabetes in this population at a rate similar to the use of metformin, one of the most common oral antidiabetic drugs (Diabetologia 2006;49:289-97).

The 16th U.S. Surgeon General, David Satcher, M.D., Ph.D., is famous for giving his "Prescription for Great Health" when he addresses colleges and universities, which includes not smoking, staying away from illicit drug use, and abstaining from unsafe sex. Importantly, the first two key points of his "prescription" are exercising at least five times a week for 30 minutes and eating at least five servings of fruits and vegetables daily. Again, very simple recommendations, but his advice has lasting and profound ramifications.

Do obstetrician/gynecologists have a role?

As ob.gyns., we always have played an incredibly critical role in maintaining the health and well-being of our patients. Now, more than ever, we have a significant opportunity to set our patients on a path to better eating, incorporating exercise into their daily routines and passing down these good habits to their children.

In the "old days," the ob.gyn. focused on a limited period in a patient’s life. Perhaps we only saw a patient for annual exams and then for a more intense time prior to and during pregnancy, and then for a checkup post partum where we may have examined our patients only for complications of the pregnancy and delivery and not much more. Although we may have included some counseling on maintaining a healthy pregnancy, many of us relied on a patient’s primary care physician to provide ongoing support.

Today, however, we must take a more active role in helping our patients establish and maintain a healthy lifestyle. Despite the increased insurance coverage under the ACA and the expansion of Medicaid, a woman’s ob.gyn. may be the only health care practitioner she will see on a routine basis. Many women do not visit a general practitioner for routine physical examinations, but women will see their ob.gyn. for regular exams. We can use these annual or biannual office visits to help women set goals to live a healthy life, approaching each patient as a whole person who needs comprehensive care throughout her reproductive life and beyond.

For patients who are overweight or obese, we may focus on helping them reduce their body mass index and blood pressure and encourage them to stay fit. We also should do everything we can to ensure that if a woman has had gestational diabetes, she’s doing what she can to reduce her risk of developing type 2 diabetes after pregnancy. For these patients, we should consider testing their blood glucose every 1-2 years during the annual checkup.

Healthy weight in pregnancy: to gain or to lose?

Whether or not an ob.gyn. practice implements a screening program and more intensive obesity and diabetes counseling, we all will face the same question: How much weight should my patient gain to have a healthy baby? Interestingly, in the first half of the 20th century, ob.gyns. were discouraged from recommending that their pregnant patients gain very much weight. Indeed, the 13th edition of "Williams Obstetrics" (New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1966, p. 326) stated that obstetricians should limit their patients from gaining more than 25 pounds during gestation, and that the ideal weight gain was 15 pounds.

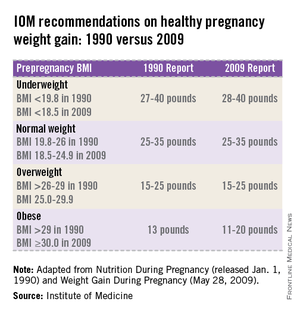

This guidance was called into question by a 1970 National Academy of Sciences report, "Maternal Nutrition and the Course of Pregnancy," which indicated a strong link between infant mortality and low maternal pregnancy weight. Further evidence suggested a need for new standards and, in 1990, the IOM issued recommendations on women’s nutrition during pregnancy (Nutrition During Pregnancy, Weight Gain and Nutrient Supplements. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press, 1990). (See table.)

Americans consume 31% more calories today than they did 40 years ago. Because of this, a woman’s need to gain weight to improve the outcome of her pregnancy is significantly reduced. The calories that many people include in their diets often come from high-fat, sodium-loaded, processed foods. We also have become a more sedentary society, spending our days at a computer, browsing the internet, watching TV, and opting to drive rather than to walk. Taking these factors into account, revising the recommendations for weight gain seemed crucial. In 2009, the IOM revised its guidance on healthy weight gain in pregnancy, and these ranges are currently widely accepted by obstetricians today (iom.edu/Reports/2009/Weight-Gain-During-Pregnancy-Reexamining-the-Guidelines.aspx). (See table.)

With the obesity and diabetes epidemics on the rise, we may need to update the 2009 IOM guidelines again – and very soon. Isolated studies have indicated that, for women who are severely obese, moderate weight loss during pregnancy may improve pregnancy outcomes. These findings remain controversial, but the "heavy" burden of diabetes and obesity on the U.S. health care system in general, and the need to reduce obstetrical complications that accompany deliveries in patients who are overweight or obese and diabetic, means that we as a community may need to reexamine our practices and approaches much more closely.

"Food" for thought

We all know of patients who, once they become pregnant, begin justifying a greater intake of food as "eating for two." Many women may use their pregnancy as an excuse to overindulge in unhealthy foods or to forgo the gym and other regular exercise regimens. Recommending basic steps to change a patient’s lifestyle can make an incredible difference in improving maternal and fetal health outcomes.

Summary recommendations for healthy pregnancy

• A low-glycemic diet, combined with moderate exercise, can reduce or eliminate many of the negative consequences of obesity on pregnant women and their babies.

• Proper weight management during pregnancy can improve birth outcomes.

• Weight loss during pregnancy is not recommended, except, potentially, for morbidly obese women (BMI greater than 40).

• For women who are normal weight, overweight or obese, leading healthy lifestyles can greatly improve maternal and fetal health outcomes. These include physical exercise, balanced diet, and weight loss, in combination with medication in some cases.

• It is never too late to begin healthy habits!

If we microfocus only on a woman’s predelivery and postdelivery health, then we’re losing a big opportunity to improve her whole self and prevent future health complications during and outside of pregnancy. The good news for ob.gyns. is that this complex problem has a simple, well-documented, and proven solution.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. Dr. Reece said he had no relevant financial disclosures. He is the medical editor of this column. Contact him at obnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

The world is not only getting older and warmer, but it’s getting heavier and more unfit each year. According to the World Health Organization’s most recent data, more than 1.4 billion adults were overweight in 2008, and 500 million of these adults were obese. In 2012, more than 40 million young children were overweight or obese. Diabetes, a disorder closely linked with obesity, affects about 347 million people worldwide – approximately ten times more people than those with HIV/AIDS. Although the number of AIDS-related deaths has steadily decreased over the last decade, even in developing countries, the number of diabetes-related deaths has steadily increased. The WHO projects that diabetes-related deaths will double by 2030, making it the seventh leading cause of death worldwide. In the United States, diabetes already is the seventh leading cause of death.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, obesity-related diseases cost $147 billion annually, a number which dwarfs the health care costs associated with smoking ($96 billion). In addition to the link with type 2 diabetes, there are strong links between obesity and heart disease, kidney disease, depression, and hypertension. From 1987 to 2007, obesity was estimated to have caused more than a 20% increase in total health care spending.

The American Diabetes Association estimates that people diagnosed with diabetes have average yearly medical expenditures of over $13,000, which is over two times higher than the expenditures of a person without diagnosed diabetes. The 2012 estimated annual cost of care for diagnosed diabetes was $245 billion, which includes $176 billion in direct medical costs and $69 billion in reduced productivity (Diabetes Care 2013 [doi:10.2337/dc12-2625]). These figures, while staggering, do not include projected expenditures for people who have yet to receive a diabetes diagnosis.

The federal government has chosen to take dramatic steps to help Americans lose weight. Since 2011, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services has covered screening and intensive behavioral therapy for obesity by primary care physicians during office visits or outpatient hospital care. Additionally, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) now requires insurance companies to help overweight and obese patients try to lose weight and be healthier. The 2012 Institute of Medicine (IOM) report, Accelerating Progress in Obesity Prevention: Solving the Weight of the Nation also has made major recommendations for health care practitioners, schools, and the food and beverage industry to take a more active part in improving our overall health.

Simple steps make a big impact on health

Despite the daunting – and perhaps somewhat disheartening – statistics on obesity and diabetes in the United States and around the world, research has shown that small steps to achieving a healthy weight and maintaining an active lifestyle can make a dramatic difference on the course of a person’s life. According to the Department of Agriculture, healthier diets could prevent about $71 billion in yearly health care costs, lost productivity, and premature deaths. This number is staggering, when you consider that the change could be as small as choosing a salad instead of fries for a side dish.

Medical research backs up the well-worn adage that "an apple a day keeps the doctor away." The Diabetes Prevention Program study, conducted in the early 2000s, found that lifestyle changes, such as getting more exercise and eating a balanced diet, had a major impact on whether a patient who is overweight with prediabetes developed type 2 diabetes (N. Engl. J. Med. 2002;346:393-403).

Lifestyle changes can also reduce the onset of diabetes in high-risk groups such as Asian Indians, where the incidence of diabetes is the highest in the world. The Indian Diabetes Prevention Programme showed that weight loss and healthy eating reduced the incidence of type 2 diabetes in this population at a rate similar to the use of metformin, one of the most common oral antidiabetic drugs (Diabetologia 2006;49:289-97).

The 16th U.S. Surgeon General, David Satcher, M.D., Ph.D., is famous for giving his "Prescription for Great Health" when he addresses colleges and universities, which includes not smoking, staying away from illicit drug use, and abstaining from unsafe sex. Importantly, the first two key points of his "prescription" are exercising at least five times a week for 30 minutes and eating at least five servings of fruits and vegetables daily. Again, very simple recommendations, but his advice has lasting and profound ramifications.

Do obstetrician/gynecologists have a role?

As ob.gyns., we always have played an incredibly critical role in maintaining the health and well-being of our patients. Now, more than ever, we have a significant opportunity to set our patients on a path to better eating, incorporating exercise into their daily routines and passing down these good habits to their children.

In the "old days," the ob.gyn. focused on a limited period in a patient’s life. Perhaps we only saw a patient for annual exams and then for a more intense time prior to and during pregnancy, and then for a checkup post partum where we may have examined our patients only for complications of the pregnancy and delivery and not much more. Although we may have included some counseling on maintaining a healthy pregnancy, many of us relied on a patient’s primary care physician to provide ongoing support.

Today, however, we must take a more active role in helping our patients establish and maintain a healthy lifestyle. Despite the increased insurance coverage under the ACA and the expansion of Medicaid, a woman’s ob.gyn. may be the only health care practitioner she will see on a routine basis. Many women do not visit a general practitioner for routine physical examinations, but women will see their ob.gyn. for regular exams. We can use these annual or biannual office visits to help women set goals to live a healthy life, approaching each patient as a whole person who needs comprehensive care throughout her reproductive life and beyond.

For patients who are overweight or obese, we may focus on helping them reduce their body mass index and blood pressure and encourage them to stay fit. We also should do everything we can to ensure that if a woman has had gestational diabetes, she’s doing what she can to reduce her risk of developing type 2 diabetes after pregnancy. For these patients, we should consider testing their blood glucose every 1-2 years during the annual checkup.

Healthy weight in pregnancy: to gain or to lose?

Whether or not an ob.gyn. practice implements a screening program and more intensive obesity and diabetes counseling, we all will face the same question: How much weight should my patient gain to have a healthy baby? Interestingly, in the first half of the 20th century, ob.gyns. were discouraged from recommending that their pregnant patients gain very much weight. Indeed, the 13th edition of "Williams Obstetrics" (New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1966, p. 326) stated that obstetricians should limit their patients from gaining more than 25 pounds during gestation, and that the ideal weight gain was 15 pounds.

This guidance was called into question by a 1970 National Academy of Sciences report, "Maternal Nutrition and the Course of Pregnancy," which indicated a strong link between infant mortality and low maternal pregnancy weight. Further evidence suggested a need for new standards and, in 1990, the IOM issued recommendations on women’s nutrition during pregnancy (Nutrition During Pregnancy, Weight Gain and Nutrient Supplements. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press, 1990). (See table.)

Americans consume 31% more calories today than they did 40 years ago. Because of this, a woman’s need to gain weight to improve the outcome of her pregnancy is significantly reduced. The calories that many people include in their diets often come from high-fat, sodium-loaded, processed foods. We also have become a more sedentary society, spending our days at a computer, browsing the internet, watching TV, and opting to drive rather than to walk. Taking these factors into account, revising the recommendations for weight gain seemed crucial. In 2009, the IOM revised its guidance on healthy weight gain in pregnancy, and these ranges are currently widely accepted by obstetricians today (iom.edu/Reports/2009/Weight-Gain-During-Pregnancy-Reexamining-the-Guidelines.aspx). (See table.)

With the obesity and diabetes epidemics on the rise, we may need to update the 2009 IOM guidelines again – and very soon. Isolated studies have indicated that, for women who are severely obese, moderate weight loss during pregnancy may improve pregnancy outcomes. These findings remain controversial, but the "heavy" burden of diabetes and obesity on the U.S. health care system in general, and the need to reduce obstetrical complications that accompany deliveries in patients who are overweight or obese and diabetic, means that we as a community may need to reexamine our practices and approaches much more closely.

"Food" for thought

We all know of patients who, once they become pregnant, begin justifying a greater intake of food as "eating for two." Many women may use their pregnancy as an excuse to overindulge in unhealthy foods or to forgo the gym and other regular exercise regimens. Recommending basic steps to change a patient’s lifestyle can make an incredible difference in improving maternal and fetal health outcomes.

Summary recommendations for healthy pregnancy

• A low-glycemic diet, combined with moderate exercise, can reduce or eliminate many of the negative consequences of obesity on pregnant women and their babies.

• Proper weight management during pregnancy can improve birth outcomes.

• Weight loss during pregnancy is not recommended, except, potentially, for morbidly obese women (BMI greater than 40).

• For women who are normal weight, overweight or obese, leading healthy lifestyles can greatly improve maternal and fetal health outcomes. These include physical exercise, balanced diet, and weight loss, in combination with medication in some cases.

• It is never too late to begin healthy habits!

If we microfocus only on a woman’s predelivery and postdelivery health, then we’re losing a big opportunity to improve her whole self and prevent future health complications during and outside of pregnancy. The good news for ob.gyns. is that this complex problem has a simple, well-documented, and proven solution.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. Dr. Reece said he had no relevant financial disclosures. He is the medical editor of this column. Contact him at obnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

The world is not only getting older and warmer, but it’s getting heavier and more unfit each year. According to the World Health Organization’s most recent data, more than 1.4 billion adults were overweight in 2008, and 500 million of these adults were obese. In 2012, more than 40 million young children were overweight or obese. Diabetes, a disorder closely linked with obesity, affects about 347 million people worldwide – approximately ten times more people than those with HIV/AIDS. Although the number of AIDS-related deaths has steadily decreased over the last decade, even in developing countries, the number of diabetes-related deaths has steadily increased. The WHO projects that diabetes-related deaths will double by 2030, making it the seventh leading cause of death worldwide. In the United States, diabetes already is the seventh leading cause of death.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, obesity-related diseases cost $147 billion annually, a number which dwarfs the health care costs associated with smoking ($96 billion). In addition to the link with type 2 diabetes, there are strong links between obesity and heart disease, kidney disease, depression, and hypertension. From 1987 to 2007, obesity was estimated to have caused more than a 20% increase in total health care spending.

The American Diabetes Association estimates that people diagnosed with diabetes have average yearly medical expenditures of over $13,000, which is over two times higher than the expenditures of a person without diagnosed diabetes. The 2012 estimated annual cost of care for diagnosed diabetes was $245 billion, which includes $176 billion in direct medical costs and $69 billion in reduced productivity (Diabetes Care 2013 [doi:10.2337/dc12-2625]). These figures, while staggering, do not include projected expenditures for people who have yet to receive a diabetes diagnosis.

The federal government has chosen to take dramatic steps to help Americans lose weight. Since 2011, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services has covered screening and intensive behavioral therapy for obesity by primary care physicians during office visits or outpatient hospital care. Additionally, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) now requires insurance companies to help overweight and obese patients try to lose weight and be healthier. The 2012 Institute of Medicine (IOM) report, Accelerating Progress in Obesity Prevention: Solving the Weight of the Nation also has made major recommendations for health care practitioners, schools, and the food and beverage industry to take a more active part in improving our overall health.

Simple steps make a big impact on health

Despite the daunting – and perhaps somewhat disheartening – statistics on obesity and diabetes in the United States and around the world, research has shown that small steps to achieving a healthy weight and maintaining an active lifestyle can make a dramatic difference on the course of a person’s life. According to the Department of Agriculture, healthier diets could prevent about $71 billion in yearly health care costs, lost productivity, and premature deaths. This number is staggering, when you consider that the change could be as small as choosing a salad instead of fries for a side dish.

Medical research backs up the well-worn adage that "an apple a day keeps the doctor away." The Diabetes Prevention Program study, conducted in the early 2000s, found that lifestyle changes, such as getting more exercise and eating a balanced diet, had a major impact on whether a patient who is overweight with prediabetes developed type 2 diabetes (N. Engl. J. Med. 2002;346:393-403).

Lifestyle changes can also reduce the onset of diabetes in high-risk groups such as Asian Indians, where the incidence of diabetes is the highest in the world. The Indian Diabetes Prevention Programme showed that weight loss and healthy eating reduced the incidence of type 2 diabetes in this population at a rate similar to the use of metformin, one of the most common oral antidiabetic drugs (Diabetologia 2006;49:289-97).

The 16th U.S. Surgeon General, David Satcher, M.D., Ph.D., is famous for giving his "Prescription for Great Health" when he addresses colleges and universities, which includes not smoking, staying away from illicit drug use, and abstaining from unsafe sex. Importantly, the first two key points of his "prescription" are exercising at least five times a week for 30 minutes and eating at least five servings of fruits and vegetables daily. Again, very simple recommendations, but his advice has lasting and profound ramifications.

Do obstetrician/gynecologists have a role?

As ob.gyns., we always have played an incredibly critical role in maintaining the health and well-being of our patients. Now, more than ever, we have a significant opportunity to set our patients on a path to better eating, incorporating exercise into their daily routines and passing down these good habits to their children.

In the "old days," the ob.gyn. focused on a limited period in a patient’s life. Perhaps we only saw a patient for annual exams and then for a more intense time prior to and during pregnancy, and then for a checkup post partum where we may have examined our patients only for complications of the pregnancy and delivery and not much more. Although we may have included some counseling on maintaining a healthy pregnancy, many of us relied on a patient’s primary care physician to provide ongoing support.

Today, however, we must take a more active role in helping our patients establish and maintain a healthy lifestyle. Despite the increased insurance coverage under the ACA and the expansion of Medicaid, a woman’s ob.gyn. may be the only health care practitioner she will see on a routine basis. Many women do not visit a general practitioner for routine physical examinations, but women will see their ob.gyn. for regular exams. We can use these annual or biannual office visits to help women set goals to live a healthy life, approaching each patient as a whole person who needs comprehensive care throughout her reproductive life and beyond.

For patients who are overweight or obese, we may focus on helping them reduce their body mass index and blood pressure and encourage them to stay fit. We also should do everything we can to ensure that if a woman has had gestational diabetes, she’s doing what she can to reduce her risk of developing type 2 diabetes after pregnancy. For these patients, we should consider testing their blood glucose every 1-2 years during the annual checkup.

Healthy weight in pregnancy: to gain or to lose?

Whether or not an ob.gyn. practice implements a screening program and more intensive obesity and diabetes counseling, we all will face the same question: How much weight should my patient gain to have a healthy baby? Interestingly, in the first half of the 20th century, ob.gyns. were discouraged from recommending that their pregnant patients gain very much weight. Indeed, the 13th edition of "Williams Obstetrics" (New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1966, p. 326) stated that obstetricians should limit their patients from gaining more than 25 pounds during gestation, and that the ideal weight gain was 15 pounds.

This guidance was called into question by a 1970 National Academy of Sciences report, "Maternal Nutrition and the Course of Pregnancy," which indicated a strong link between infant mortality and low maternal pregnancy weight. Further evidence suggested a need for new standards and, in 1990, the IOM issued recommendations on women’s nutrition during pregnancy (Nutrition During Pregnancy, Weight Gain and Nutrient Supplements. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press, 1990). (See table.)

Americans consume 31% more calories today than they did 40 years ago. Because of this, a woman’s need to gain weight to improve the outcome of her pregnancy is significantly reduced. The calories that many people include in their diets often come from high-fat, sodium-loaded, processed foods. We also have become a more sedentary society, spending our days at a computer, browsing the internet, watching TV, and opting to drive rather than to walk. Taking these factors into account, revising the recommendations for weight gain seemed crucial. In 2009, the IOM revised its guidance on healthy weight gain in pregnancy, and these ranges are currently widely accepted by obstetricians today (iom.edu/Reports/2009/Weight-Gain-During-Pregnancy-Reexamining-the-Guidelines.aspx). (See table.)

With the obesity and diabetes epidemics on the rise, we may need to update the 2009 IOM guidelines again – and very soon. Isolated studies have indicated that, for women who are severely obese, moderate weight loss during pregnancy may improve pregnancy outcomes. These findings remain controversial, but the "heavy" burden of diabetes and obesity on the U.S. health care system in general, and the need to reduce obstetrical complications that accompany deliveries in patients who are overweight or obese and diabetic, means that we as a community may need to reexamine our practices and approaches much more closely.

"Food" for thought

We all know of patients who, once they become pregnant, begin justifying a greater intake of food as "eating for two." Many women may use their pregnancy as an excuse to overindulge in unhealthy foods or to forgo the gym and other regular exercise regimens. Recommending basic steps to change a patient’s lifestyle can make an incredible difference in improving maternal and fetal health outcomes.

Summary recommendations for healthy pregnancy

• A low-glycemic diet, combined with moderate exercise, can reduce or eliminate many of the negative consequences of obesity on pregnant women and their babies.

• Proper weight management during pregnancy can improve birth outcomes.

• Weight loss during pregnancy is not recommended, except, potentially, for morbidly obese women (BMI greater than 40).

• For women who are normal weight, overweight or obese, leading healthy lifestyles can greatly improve maternal and fetal health outcomes. These include physical exercise, balanced diet, and weight loss, in combination with medication in some cases.

• It is never too late to begin healthy habits!

If we microfocus only on a woman’s predelivery and postdelivery health, then we’re losing a big opportunity to improve her whole self and prevent future health complications during and outside of pregnancy. The good news for ob.gyns. is that this complex problem has a simple, well-documented, and proven solution.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. Dr. Reece said he had no relevant financial disclosures. He is the medical editor of this column. Contact him at obnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

Electromechanical power morcellation confined to a bag

In the previous edition of Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery, I described the controversy concerning electromechanical power morcellation freely in the abdominopelvic cavity. I also discussed the risks, as noted in the literature, of spreading an unsuspected leiomyosarcoma, and thus, up-staging the disease and lowering both the length of the disease-free state and the overall survival. I also talked about the lack of an adequate diagnostic study to definitively separate a leiomyoma from a leiomyosarcoma, discussed the at-risk population group, and also noted the benefits of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery. At that time, I stated I was against a ban on the morcellator, and that I recommended that physicians provide proper informed consent and, when possible, consider other treatment options, especially in the at-risk population. These included continued use of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery utilizing a specimen bag for electromechanical power morcellation.

Following that publication, the Food and Drug Administration released a statement regarding electromechanical power morcellation on April 17, 2014. While "discouraging" the use of electromechanical power morcellation, they wisely did not call for a moratorium. Again, the FDA recommended that patients be properly informed as to risk and that alternative therapies be discussed, which included the use of power morcellation in a bag.

While the FDA did not ban electromechanical power morcellation, the phrase "discourages the use" sent widespread ripples throughout our specialty. Within a week, Ethicon Endo-Surgery pulled its morcellator off the market worldwide. My hospital system – Advocate Health Care – as well as virtually every hospital in Boston placed a moratorium on electromechanical power morcellation. Dr. Jim Tsaltas, president of the Australian Gynecological Endoscopy & Surgery Society (AGES), was contacted by his country’s FDA equivalent to discuss the use of power morcellation freely in the abdominopelvic cavity.

Since the letter from the FDA, position papers have come from both the world’s largest society focused on minimally invasive surgery, the AAGL, and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). Both of the society’s statements agree that proper informed consent is imperative and that alternate treatment be considered, especially in the at-risk population. Although both papers discuss the use of electromechanical power morcellation in the confines of a bag, the ACOG statement accurately notes that there is very little data regarding morcellation in a bag placed in the abdominopelvic cavity.

Experience with electromechanical power morcellation in a bag placed in the abdominopelvic cavity is now quickly developing. To quote my coauthor, Dr. Ceana Nezhat, "My goal with this Master Class is to provide a forum for discussion and encourage gynecologic surgeons to continue to practice minimally invasive surgery for the benefit of their patients. Despite the current limitation on unprotected, intraperitoneal electromechanical morcellation, the hope is that surgeons will not revert back to laparotomy, but will continue to learn and find innovative ways to provide the least invasive surgical techniques or refer to centers that can provide these services to women."

In this edition of Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery, I am featuring techniques of electromechanical power morcellation in a specimen bag by early adapters and innovators, and other techniques by Dr. Tony Shibley, Dr. Bernard Taylor, and Dr. Ceana H. Nezhat.

Dr. Shibley has been in full-time practice with Ob.Gyn. Specialists, Fairview Health Services in the Minneapolis area (Edina), for the past 20 years. He has a focus on single-site surgery and has been involved in minimally invasive surgical education both nationally and internationally, as well as in medical device development.

Dr. Taylor is a urogynecologist who is a female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgeon practicing at the Carolinas Medical Center–Advanced Surgical Specialties for Women in Charlotte, N.C. He lectures nationally and internationally on minimally invasive gynecologic surgery.

Dr. Nezhat is the current president of the AAGL, adjunct professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Emory University and program director of minimally invasive surgery at Northside Hospital, both in Atlanta, and adjunct clinical professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Stanford (Calif.) University.

Dr. Miller is clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, immediate past president of the International Society for Gynecologic Endoscopy, and a past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in private practice in Naperville, Ill., and Schaumburg, Ill.; the director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill.; and the medical editor of this column. Dr. Miller disclosed that he is a consultant to Ethicon Endo-Surgery.

Videos of our experts’ individual techniques of electromechanical power morcellation within the confines of a bag, as well as that of Dr. Douglas Brown, director of the Center for Minimally Invasive Gynecologic Surgery at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, can be viewed at the SurgeryU website. Also at SurgeryU is a video of the electromechanical power morcellation technique in a bag that my partner, Dr. Aarathi Cholkeri-Singh, and I utilize. We use a 3,100-cc ripstop nylon specimen bag from Espiner Medical and the 5 x 150 mm, extra-long, shielded-bladed balloon-tipped trocar from Applied Medical. Go to SurgeryU to view videos of the procedures.

In the previous edition of Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery, I described the controversy concerning electromechanical power morcellation freely in the abdominopelvic cavity. I also discussed the risks, as noted in the literature, of spreading an unsuspected leiomyosarcoma, and thus, up-staging the disease and lowering both the length of the disease-free state and the overall survival. I also talked about the lack of an adequate diagnostic study to definitively separate a leiomyoma from a leiomyosarcoma, discussed the at-risk population group, and also noted the benefits of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery. At that time, I stated I was against a ban on the morcellator, and that I recommended that physicians provide proper informed consent and, when possible, consider other treatment options, especially in the at-risk population. These included continued use of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery utilizing a specimen bag for electromechanical power morcellation.

Following that publication, the Food and Drug Administration released a statement regarding electromechanical power morcellation on April 17, 2014. While "discouraging" the use of electromechanical power morcellation, they wisely did not call for a moratorium. Again, the FDA recommended that patients be properly informed as to risk and that alternative therapies be discussed, which included the use of power morcellation in a bag.

While the FDA did not ban electromechanical power morcellation, the phrase "discourages the use" sent widespread ripples throughout our specialty. Within a week, Ethicon Endo-Surgery pulled its morcellator off the market worldwide. My hospital system – Advocate Health Care – as well as virtually every hospital in Boston placed a moratorium on electromechanical power morcellation. Dr. Jim Tsaltas, president of the Australian Gynecological Endoscopy & Surgery Society (AGES), was contacted by his country’s FDA equivalent to discuss the use of power morcellation freely in the abdominopelvic cavity.

Since the letter from the FDA, position papers have come from both the world’s largest society focused on minimally invasive surgery, the AAGL, and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). Both of the society’s statements agree that proper informed consent is imperative and that alternate treatment be considered, especially in the at-risk population. Although both papers discuss the use of electromechanical power morcellation in the confines of a bag, the ACOG statement accurately notes that there is very little data regarding morcellation in a bag placed in the abdominopelvic cavity.

Experience with electromechanical power morcellation in a bag placed in the abdominopelvic cavity is now quickly developing. To quote my coauthor, Dr. Ceana Nezhat, "My goal with this Master Class is to provide a forum for discussion and encourage gynecologic surgeons to continue to practice minimally invasive surgery for the benefit of their patients. Despite the current limitation on unprotected, intraperitoneal electromechanical morcellation, the hope is that surgeons will not revert back to laparotomy, but will continue to learn and find innovative ways to provide the least invasive surgical techniques or refer to centers that can provide these services to women."

In this edition of Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery, I am featuring techniques of electromechanical power morcellation in a specimen bag by early adapters and innovators, and other techniques by Dr. Tony Shibley, Dr. Bernard Taylor, and Dr. Ceana H. Nezhat.

Dr. Shibley has been in full-time practice with Ob.Gyn. Specialists, Fairview Health Services in the Minneapolis area (Edina), for the past 20 years. He has a focus on single-site surgery and has been involved in minimally invasive surgical education both nationally and internationally, as well as in medical device development.

Dr. Taylor is a urogynecologist who is a female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgeon practicing at the Carolinas Medical Center–Advanced Surgical Specialties for Women in Charlotte, N.C. He lectures nationally and internationally on minimally invasive gynecologic surgery.

Dr. Nezhat is the current president of the AAGL, adjunct professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Emory University and program director of minimally invasive surgery at Northside Hospital, both in Atlanta, and adjunct clinical professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Stanford (Calif.) University.

Dr. Miller is clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, immediate past president of the International Society for Gynecologic Endoscopy, and a past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in private practice in Naperville, Ill., and Schaumburg, Ill.; the director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill.; and the medical editor of this column. Dr. Miller disclosed that he is a consultant to Ethicon Endo-Surgery.

Videos of our experts’ individual techniques of electromechanical power morcellation within the confines of a bag, as well as that of Dr. Douglas Brown, director of the Center for Minimally Invasive Gynecologic Surgery at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, can be viewed at the SurgeryU website. Also at SurgeryU is a video of the electromechanical power morcellation technique in a bag that my partner, Dr. Aarathi Cholkeri-Singh, and I utilize. We use a 3,100-cc ripstop nylon specimen bag from Espiner Medical and the 5 x 150 mm, extra-long, shielded-bladed balloon-tipped trocar from Applied Medical. Go to SurgeryU to view videos of the procedures.

In the previous edition of Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery, I described the controversy concerning electromechanical power morcellation freely in the abdominopelvic cavity. I also discussed the risks, as noted in the literature, of spreading an unsuspected leiomyosarcoma, and thus, up-staging the disease and lowering both the length of the disease-free state and the overall survival. I also talked about the lack of an adequate diagnostic study to definitively separate a leiomyoma from a leiomyosarcoma, discussed the at-risk population group, and also noted the benefits of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery. At that time, I stated I was against a ban on the morcellator, and that I recommended that physicians provide proper informed consent and, when possible, consider other treatment options, especially in the at-risk population. These included continued use of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery utilizing a specimen bag for electromechanical power morcellation.

Following that publication, the Food and Drug Administration released a statement regarding electromechanical power morcellation on April 17, 2014. While "discouraging" the use of electromechanical power morcellation, they wisely did not call for a moratorium. Again, the FDA recommended that patients be properly informed as to risk and that alternative therapies be discussed, which included the use of power morcellation in a bag.