User login

50 years of ob.gyn.: Has practice changed for the better?

As a practicing obstetrician-gynecologist for nearly 40 years, Leonard Brabson, MD, has watched his specialty transform in ways both large and small.

For starters, his regular work attire in 1977 – a shirt and tie – is now scrubs. The paper charts that once filled his office shelves have been replaced with electronic records. And the cumbersome machines that once took blurry, still pictures of a fetus have advanced by leaps and bounds and become a staple of prenatal care.

“Back then, we were expected to be generalists. If [a patient] had a cancer, you took care of it. If [she] had a fertility problem or problem with endocrinology, you took care of it. Of course, now if I have a female cancer, we refer them to the gyn-oncologist. But when you go back 40 years and beyond, we did mostly everything.”

The ob.gyns. of today are practicing in a vastly different environment than their predecessors, and while many of the differences have improved patient care and enhanced efficiency, physicians also note that some changes have harmed the doctor-patient relationship and created career dissatisfaction.

“Certainly, the advances of modern medicine have enabled the current physician to provide the patient a level of care unparalleled in history,” said Charles E. Miller, MD, a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in private practice in Naperville and Schaumburg, Ill.

More volume, less time

Most long-time physicians agree that higher patient volumes and increasing administrative burdens have diminished the time they are able to spend with patients.

Rising clinical documentation and coding are the top administrative tasks taking away from one-on-one patient care, said Kristen Zeligs, MD, chair of the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Junior Fellow Congress Advisory Council and a gynecologic oncology fellow at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Bethesda, Md.

But there are other factors straining the doctor-patient relationship. Decades ago, first-time mothers often stayed with one doctor for a lifetime, Dr. Brabson recalled, having all of her babies delivered by a single ob.gyn. The same can’t be said for today, where insurance changes, job relocations, and a lack of connections often lead patients to switch physicians frequently.

“Now a lot of patients [move on] from one year to the next,” Dr. Brabson said. “There’s not that same loyalty.”

Doctors, too, traditionally stuck with patients over the long haul, he added. In the past, if an ob.gyn treated a patient during pregnancy, that same physician was present during the delivery, even if it meant leaving a vacation early or coming in on a night off.

“Now the younger docs, especially those that have families with small children, when it’s not their night on call and it’s 5 o’clock, they’re checking out,” Dr. Brabson said. “One of my partners right now, she started inducing someone yesterday. Well today’s her day off, so I’m going to do the delivery. That’s been a big change.”

Highs and lows of liability premiums

Another pressure on the specialty over the last couple of decades has been the high cost of liability insurance.

“2003 was really the peak of the liability crisis,” Dr. Montgomery said. “Hospitals were closing. Doctors were giving up practice. It’s a little better now than it was.”

While ob.gyns. still pay higher premiums than many other specialties, the legal climate has improved in recent years, said Paul Greve Jr., executive vice president and senior consultant for the Willis Healthcare Practice, and author of the 2016 Medical Liability Monitor, an annual report that surveys medical liability premiums.

“The best way to characterize the overall environment for medical professional liability is stable,” he said. “In the area of obstetrics, for the first time ever in recent years, we are seeing lower frequency and lower severity [of lawsuits].”

The lower number of filings are largely due to patient safety initiatives among ob.gyn. programs and tort reforms – many of which have been upheld by courts in the last decade, Mr. Greve said.

Of course, the rate of premiums greatly differs depending on location, with ob.gyns. in Eastern New York paying a high of $214,999 and ob.gyns. in Minnesota paying a low of $16,449 in 2016, according to the Medical Liability Monitor.

“The environment is specific to the region,” Mr. Greve said. “New York City is still very problematic. Chicago is still very problematic. There are some pockets around the country where there’s no damage caps, and it’s really tough to defend claims.”

Technology ups and downs

Another fairly new pressure on ob.gyns. is the integration of the electronic health record and the federal reporting requirements that go along with it.

“Most practicing ob.gyns. are really fed up with the computerization of medicine and the tasking and the charting,” Dr. Montgomery said. “For every hour you spend seeing patients, you spend 1 or 2 hours doing computer chart work and paperwork. Most doctors don’t go into medicine so they can type; they go into medicine to take care of patients.”

The Internet age also poses challenges when it comes to patients conducting their own “research,” said Megan Evans, MD, an ob.gyn. at Tufts Medical Center, Boston.

Protecting the security of patients’ medical records in the digital age is another worry, she said.

But for Dr. Evans, who completed her residency training in 2015, having dozens of digital tools at her disposal as she treats patients is definitely an upside to today’s practice environment.

“I can review a practice bulletin, look up the latest treatment regimens, and contact my colleagues with a quick question – all on my iPhone,” she said. “I also believe there is so much potential for electronic medical records and how they communicate with each other.”

Advancements in ultrasound, fetal monitoring, and other medical technologies have also allowed ob.gyns. to intervene earlier and save lives.

Dr. Brabson recalled the helplessness he and other physicians felt in the 1970s when it came to delivering extremely premature babies.

“We didn’t really feel like you could save a baby under 2 pounds,” he said. “When I was a medical student, if you had a baby under 2 pounds, very commonly what they would do is lay the baby up on the table and watch and see how vigorous it was going to be, and if it really did breathe and carry on for awhile, then you might take it to the nursery. The equipment that we have to save babies with today, compared to 40 years ago, that’s a dramatic change.”

A changing focus for the future

If current trends continue, Dr. Brabson’s early experience of being a generalist ob.gyn. won’t be the norm. Instead, more ob.gyns. will choose to subspecialize. Whether this change is positive or negative for the specialty depends on who you ask.

“You could argue the pros and cons for both sides,” Dr. Zeligs said. “For me, it takes away from what drew me to the specialty – the breadth that ob.gyn. offers, both as a primary care specialty and as a surgical subspecialty.”

However, choosing one focus may offer some doctors a way to capture that elusive professional and personal balance, she added.

Despite the changing landscape of clinical duties and business operations, some parts of ob.gyn. practice have remained intact, according to Dr. Brabson. “The most rewarding and enjoyable part of the job is developing a relationship of mutual trust and respect,” he said. “As a result of developing such a relationship, both the patient and the doctor come away with positive feelings. This has not changed.”

agallegos@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @legal_med

As a practicing obstetrician-gynecologist for nearly 40 years, Leonard Brabson, MD, has watched his specialty transform in ways both large and small.

For starters, his regular work attire in 1977 – a shirt and tie – is now scrubs. The paper charts that once filled his office shelves have been replaced with electronic records. And the cumbersome machines that once took blurry, still pictures of a fetus have advanced by leaps and bounds and become a staple of prenatal care.

“Back then, we were expected to be generalists. If [a patient] had a cancer, you took care of it. If [she] had a fertility problem or problem with endocrinology, you took care of it. Of course, now if I have a female cancer, we refer them to the gyn-oncologist. But when you go back 40 years and beyond, we did mostly everything.”

The ob.gyns. of today are practicing in a vastly different environment than their predecessors, and while many of the differences have improved patient care and enhanced efficiency, physicians also note that some changes have harmed the doctor-patient relationship and created career dissatisfaction.

“Certainly, the advances of modern medicine have enabled the current physician to provide the patient a level of care unparalleled in history,” said Charles E. Miller, MD, a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in private practice in Naperville and Schaumburg, Ill.

More volume, less time

Most long-time physicians agree that higher patient volumes and increasing administrative burdens have diminished the time they are able to spend with patients.

Rising clinical documentation and coding are the top administrative tasks taking away from one-on-one patient care, said Kristen Zeligs, MD, chair of the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Junior Fellow Congress Advisory Council and a gynecologic oncology fellow at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Bethesda, Md.

But there are other factors straining the doctor-patient relationship. Decades ago, first-time mothers often stayed with one doctor for a lifetime, Dr. Brabson recalled, having all of her babies delivered by a single ob.gyn. The same can’t be said for today, where insurance changes, job relocations, and a lack of connections often lead patients to switch physicians frequently.

“Now a lot of patients [move on] from one year to the next,” Dr. Brabson said. “There’s not that same loyalty.”

Doctors, too, traditionally stuck with patients over the long haul, he added. In the past, if an ob.gyn treated a patient during pregnancy, that same physician was present during the delivery, even if it meant leaving a vacation early or coming in on a night off.

“Now the younger docs, especially those that have families with small children, when it’s not their night on call and it’s 5 o’clock, they’re checking out,” Dr. Brabson said. “One of my partners right now, she started inducing someone yesterday. Well today’s her day off, so I’m going to do the delivery. That’s been a big change.”

Highs and lows of liability premiums

Another pressure on the specialty over the last couple of decades has been the high cost of liability insurance.

“2003 was really the peak of the liability crisis,” Dr. Montgomery said. “Hospitals were closing. Doctors were giving up practice. It’s a little better now than it was.”

While ob.gyns. still pay higher premiums than many other specialties, the legal climate has improved in recent years, said Paul Greve Jr., executive vice president and senior consultant for the Willis Healthcare Practice, and author of the 2016 Medical Liability Monitor, an annual report that surveys medical liability premiums.

“The best way to characterize the overall environment for medical professional liability is stable,” he said. “In the area of obstetrics, for the first time ever in recent years, we are seeing lower frequency and lower severity [of lawsuits].”

The lower number of filings are largely due to patient safety initiatives among ob.gyn. programs and tort reforms – many of which have been upheld by courts in the last decade, Mr. Greve said.

Of course, the rate of premiums greatly differs depending on location, with ob.gyns. in Eastern New York paying a high of $214,999 and ob.gyns. in Minnesota paying a low of $16,449 in 2016, according to the Medical Liability Monitor.

“The environment is specific to the region,” Mr. Greve said. “New York City is still very problematic. Chicago is still very problematic. There are some pockets around the country where there’s no damage caps, and it’s really tough to defend claims.”

Technology ups and downs

Another fairly new pressure on ob.gyns. is the integration of the electronic health record and the federal reporting requirements that go along with it.

“Most practicing ob.gyns. are really fed up with the computerization of medicine and the tasking and the charting,” Dr. Montgomery said. “For every hour you spend seeing patients, you spend 1 or 2 hours doing computer chart work and paperwork. Most doctors don’t go into medicine so they can type; they go into medicine to take care of patients.”

The Internet age also poses challenges when it comes to patients conducting their own “research,” said Megan Evans, MD, an ob.gyn. at Tufts Medical Center, Boston.

Protecting the security of patients’ medical records in the digital age is another worry, she said.

But for Dr. Evans, who completed her residency training in 2015, having dozens of digital tools at her disposal as she treats patients is definitely an upside to today’s practice environment.

“I can review a practice bulletin, look up the latest treatment regimens, and contact my colleagues with a quick question – all on my iPhone,” she said. “I also believe there is so much potential for electronic medical records and how they communicate with each other.”

Advancements in ultrasound, fetal monitoring, and other medical technologies have also allowed ob.gyns. to intervene earlier and save lives.

Dr. Brabson recalled the helplessness he and other physicians felt in the 1970s when it came to delivering extremely premature babies.

“We didn’t really feel like you could save a baby under 2 pounds,” he said. “When I was a medical student, if you had a baby under 2 pounds, very commonly what they would do is lay the baby up on the table and watch and see how vigorous it was going to be, and if it really did breathe and carry on for awhile, then you might take it to the nursery. The equipment that we have to save babies with today, compared to 40 years ago, that’s a dramatic change.”

A changing focus for the future

If current trends continue, Dr. Brabson’s early experience of being a generalist ob.gyn. won’t be the norm. Instead, more ob.gyns. will choose to subspecialize. Whether this change is positive or negative for the specialty depends on who you ask.

“You could argue the pros and cons for both sides,” Dr. Zeligs said. “For me, it takes away from what drew me to the specialty – the breadth that ob.gyn. offers, both as a primary care specialty and as a surgical subspecialty.”

However, choosing one focus may offer some doctors a way to capture that elusive professional and personal balance, she added.

Despite the changing landscape of clinical duties and business operations, some parts of ob.gyn. practice have remained intact, according to Dr. Brabson. “The most rewarding and enjoyable part of the job is developing a relationship of mutual trust and respect,” he said. “As a result of developing such a relationship, both the patient and the doctor come away with positive feelings. This has not changed.”

agallegos@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @legal_med

As a practicing obstetrician-gynecologist for nearly 40 years, Leonard Brabson, MD, has watched his specialty transform in ways both large and small.

For starters, his regular work attire in 1977 – a shirt and tie – is now scrubs. The paper charts that once filled his office shelves have been replaced with electronic records. And the cumbersome machines that once took blurry, still pictures of a fetus have advanced by leaps and bounds and become a staple of prenatal care.

“Back then, we were expected to be generalists. If [a patient] had a cancer, you took care of it. If [she] had a fertility problem or problem with endocrinology, you took care of it. Of course, now if I have a female cancer, we refer them to the gyn-oncologist. But when you go back 40 years and beyond, we did mostly everything.”

The ob.gyns. of today are practicing in a vastly different environment than their predecessors, and while many of the differences have improved patient care and enhanced efficiency, physicians also note that some changes have harmed the doctor-patient relationship and created career dissatisfaction.

“Certainly, the advances of modern medicine have enabled the current physician to provide the patient a level of care unparalleled in history,” said Charles E. Miller, MD, a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in private practice in Naperville and Schaumburg, Ill.

More volume, less time

Most long-time physicians agree that higher patient volumes and increasing administrative burdens have diminished the time they are able to spend with patients.

Rising clinical documentation and coding are the top administrative tasks taking away from one-on-one patient care, said Kristen Zeligs, MD, chair of the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Junior Fellow Congress Advisory Council and a gynecologic oncology fellow at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Bethesda, Md.

But there are other factors straining the doctor-patient relationship. Decades ago, first-time mothers often stayed with one doctor for a lifetime, Dr. Brabson recalled, having all of her babies delivered by a single ob.gyn. The same can’t be said for today, where insurance changes, job relocations, and a lack of connections often lead patients to switch physicians frequently.

“Now a lot of patients [move on] from one year to the next,” Dr. Brabson said. “There’s not that same loyalty.”

Doctors, too, traditionally stuck with patients over the long haul, he added. In the past, if an ob.gyn treated a patient during pregnancy, that same physician was present during the delivery, even if it meant leaving a vacation early or coming in on a night off.

“Now the younger docs, especially those that have families with small children, when it’s not their night on call and it’s 5 o’clock, they’re checking out,” Dr. Brabson said. “One of my partners right now, she started inducing someone yesterday. Well today’s her day off, so I’m going to do the delivery. That’s been a big change.”

Highs and lows of liability premiums

Another pressure on the specialty over the last couple of decades has been the high cost of liability insurance.

“2003 was really the peak of the liability crisis,” Dr. Montgomery said. “Hospitals were closing. Doctors were giving up practice. It’s a little better now than it was.”

While ob.gyns. still pay higher premiums than many other specialties, the legal climate has improved in recent years, said Paul Greve Jr., executive vice president and senior consultant for the Willis Healthcare Practice, and author of the 2016 Medical Liability Monitor, an annual report that surveys medical liability premiums.

“The best way to characterize the overall environment for medical professional liability is stable,” he said. “In the area of obstetrics, for the first time ever in recent years, we are seeing lower frequency and lower severity [of lawsuits].”

The lower number of filings are largely due to patient safety initiatives among ob.gyn. programs and tort reforms – many of which have been upheld by courts in the last decade, Mr. Greve said.

Of course, the rate of premiums greatly differs depending on location, with ob.gyns. in Eastern New York paying a high of $214,999 and ob.gyns. in Minnesota paying a low of $16,449 in 2016, according to the Medical Liability Monitor.

“The environment is specific to the region,” Mr. Greve said. “New York City is still very problematic. Chicago is still very problematic. There are some pockets around the country where there’s no damage caps, and it’s really tough to defend claims.”

Technology ups and downs

Another fairly new pressure on ob.gyns. is the integration of the electronic health record and the federal reporting requirements that go along with it.

“Most practicing ob.gyns. are really fed up with the computerization of medicine and the tasking and the charting,” Dr. Montgomery said. “For every hour you spend seeing patients, you spend 1 or 2 hours doing computer chart work and paperwork. Most doctors don’t go into medicine so they can type; they go into medicine to take care of patients.”

The Internet age also poses challenges when it comes to patients conducting their own “research,” said Megan Evans, MD, an ob.gyn. at Tufts Medical Center, Boston.

Protecting the security of patients’ medical records in the digital age is another worry, she said.

But for Dr. Evans, who completed her residency training in 2015, having dozens of digital tools at her disposal as she treats patients is definitely an upside to today’s practice environment.

“I can review a practice bulletin, look up the latest treatment regimens, and contact my colleagues with a quick question – all on my iPhone,” she said. “I also believe there is so much potential for electronic medical records and how they communicate with each other.”

Advancements in ultrasound, fetal monitoring, and other medical technologies have also allowed ob.gyns. to intervene earlier and save lives.

Dr. Brabson recalled the helplessness he and other physicians felt in the 1970s when it came to delivering extremely premature babies.

“We didn’t really feel like you could save a baby under 2 pounds,” he said. “When I was a medical student, if you had a baby under 2 pounds, very commonly what they would do is lay the baby up on the table and watch and see how vigorous it was going to be, and if it really did breathe and carry on for awhile, then you might take it to the nursery. The equipment that we have to save babies with today, compared to 40 years ago, that’s a dramatic change.”

A changing focus for the future

If current trends continue, Dr. Brabson’s early experience of being a generalist ob.gyn. won’t be the norm. Instead, more ob.gyns. will choose to subspecialize. Whether this change is positive or negative for the specialty depends on who you ask.

“You could argue the pros and cons for both sides,” Dr. Zeligs said. “For me, it takes away from what drew me to the specialty – the breadth that ob.gyn. offers, both as a primary care specialty and as a surgical subspecialty.”

However, choosing one focus may offer some doctors a way to capture that elusive professional and personal balance, she added.

Despite the changing landscape of clinical duties and business operations, some parts of ob.gyn. practice have remained intact, according to Dr. Brabson. “The most rewarding and enjoyable part of the job is developing a relationship of mutual trust and respect,” he said. “As a result of developing such a relationship, both the patient and the doctor come away with positive feelings. This has not changed.”

agallegos@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @legal_med

The 50-year quest for better pregnancy data

Editor’s note: As Ob.Gyn. News celebrates its 50th anniversary, we wanted to know how far the medical community has come in identifying and mitigating drug risks during pregnancy and in the postpartum period. In this article, our four expert columnists share their experiences trying to find and interpret critical pregnancy data, as well as how they weigh the potential risks and benefits for their patients.

The search for information

The biggest advance in the past 50 years is the availability of information, even though limited, relating to the effects of drugs in pregnancy and lactation. In the first few years of this period, it was a daunting task to obtain this information. I can recall spending hours in the hospital’s medical library going through huge volumes of Index Medicus to obtain references that the library could order for me. The appearance of Thomas H. Shepard’s first edition (Catalog of Teratogenic Agents) in 1973 was a step forward and in 1977, O.P. Heinonen and colleagues’ book (Birth Defects and Drugs in Pregnancy) was helpful.

Although all of the above sources were helpful, any book in an evolving field will not have the newest information. Two important services, TERIS and Reprotox, were started to allow clinicians to contact them for up-to-date data. Nevertheless, the biggest change was the availability of current information from the U.S. National Library of Medicine via Toxnet, PubMed, and LactMed, relating to the effects of drugs in pregnancy and lactation.

My method is to ask three questions. First, are there other drugs with a similar mechanism of action that have some human data? In most cases, the answer to this question is no, but even when there are data, it is typically very limited. Second, does the drug cross the human placenta? The answer is typically based on the molecular weight. Any drug with a molecular weight less than 1,000 daltons probably crosses. In the second half of pregnancy, especially in the third trimester, almost every drug crosses. Third, do the animal pregnancy data predict embryo/fetal risk? It was thought that it could if the dose causing harm was less than or equal to 10 times the human dose based on BSA or AUC and there were no signs of maternal toxicity. However, using data from my 10th edition, I and eight coauthors, all of whom are knowledgeable on the effects of drugs in pregnancy, found that the animal data for 311 drugs raised the possibility of human embryo-fetal harm that current data confirmed in only 75 (24%) of the drugs (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Dec;213[6]:810-5).

The system needs to be fixed. One method is to give the Food and Drug Administration the authority to require manufacturers of drugs likely to be used in pregnancy to gather and publish data on their use in pregnancy. That sounds reasonable, but will it ever occur?

Mr. Briggs is clinical professor of pharmacy at the University of California, San Francisco, and adjunct professor of pharmacy at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, and Washington State University, Spokane. He is coauthor of “Drugs in Pregnancy and Lactation,” and coeditor of “Diseases, Complications, and Drug Therapy in Obstetrics.” He has no relevant financial disclosures.

Learning the lessons of the past

During the last 50 years, two of the most potent known human teratogens, thalidomide and isotretinoin, became available for prescription in the United States. Thanks to the efforts of Frances Kelsey, MD, PhD, at the FDA, the initial application for approval of thalidomide in the United States was denied in the early 1960s. Subsequently, based on evidence from other countries where thalidomide was marketed that the drug can cause a pattern of serious birth defects, a very strict pregnancy prevention program was implemented when the drug was finally approved in the United States in 2006.

Over the last 50 years, we have also seen an important evolution in our ability to conduct pregnancy exposure safety studies. Though we still have limited ability to conduct clinical trials in pregnant women, the need for good quality observational studies has become more widely accepted. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Birth Defects Prevention Study (now in its most recent iteration known as BD STEPS) has been one very important source of data on the safety of a wide variety of medications. Using a case-control study design, women who have delivered infants with specific birth defects and comparison women who have delivered non-malformed infants are interviewed about their exposures in pregnancy. These data have been extremely helpful in generating new hypotheses, confirming or refuting findings from other studies, and in testing hypotheses regarding the safety of medications widely used in women of reproductive age. These analyses, for example, have contributed to the large body of literature now available on the safety of antidepressant medications in pregnancy.

At the same time, in the last 30 years, we have seen a tremendous increase in the number of pregnancy registries required or recommended upon approval of a new drug in the United States. These registry studies, while challenging to complete in a timely manner, have steadily improved in terms of rigor, and several disease-based pregnancy exposure studies have been implemented, which have allowed us to better understand the comparative risks or safety of anticonvulsants and antiretroviral drugs, to name a few.

It is important to note that with all these advances in the last 50 years, we still have a huge gap in knowledge about medication safety in pregnancy and lactation. Recent reviews suggest that more than 80% of drugs currently marketed have insufficient or no data available. If we include over-the-counter medications, the knowledge gap grows larger. With the 2014 approval of the long-awaited Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule, clinicians are now beginning to experience the elimination of the old A-B-C-D-X category system for pregnancy safety. In its place, data-driven product labels are required. These are expected to provide the clinician with a clear summary of the relevant studies for a given medication, and to place these in the context of the background risks for the underlying maternal disease being treated, as well as the population risks. However, it is painfully clear that we have a long way to go to generate the needed, high-quality data, to populate those labels.

Dr. Chambers is a professor of pediatrics and director of clinical research at Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego, and associate director of the Clinical and Translational Research Institute at the University of California, San Diego. She is director of MotherToBaby California, a past president of the Organization of Teratology Information Specialists, and past president of the Teratology Society. She has no relevant financial disclosures.

Moving toward personalized medicine

Nowhere is a lack of actionable data more pronounced than in the impact of mental health drugs in pregnancy.

As Dr. Briggs and Dr. Chambers have outlined, the quality of data regarding the reproductive safety of medications across the therapeutic spectrum has historically been fair at best. The methodology and the rigor has been sparse and to a large extent, in psychiatry, we were only able to look for signals of concern. Prior to the late 1980s and early 1990s, there was little to guide clinicians on the safety of even very commonly used psychiatric medications during pregnancy. The health implications for women of reproductive age are extraordinary and yet that urgency was not matched by the level of investigation until more recently.

In psychiatry, we have rapidly improving data informing women about the risk for major congenital malformations. The clinical dilemma of weighing the necessity to stay on a medication to prevent relapse of a psychiatric disorder with the potential risk of malformation in the fetus is a wrenching one for the mother-to-be. Only good information can help patients, together with their physician, make collaborative decisions that make sense for them. Given the same information and the same severity of illness, women will make different decisions, and that’s a good thing. The calculus couples use to make these private decisions is unique to those involved. But they are able to move through the process because they have a platform of high-quality information.

So where do we go in the future? We need to get beyond the question of risk of major malformations and move toward understanding the long-term neurodevelopmental implications of prenatal exposures – whether such exposures confer risk or are even potentially salutary. One needs only look at the vast body of literature regarding fetal exposure to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) to observe the realization of this trend. When it comes to SSRIs, a fairly clear picture has emerged that they pose little absolute risk in terms of congenital malformations. What is missing is how SSRIs impact a child’s learning and development at age 3, 5, and 10. There have been a few studies in this area, but not a single, large prospective study that accurately quantifies both exposure to SSRIs and maternal psychiatric illness during pregnancy.

I expect that the future will also bring a greater understanding of the impact of untreated mental illness on the risk for obstetrical, neonatal, and longer-term neurodevelopmental outcomes. Most of the safety concerns have centered around the effect of fetal exposure to medications, but we also need to better understand how untreated psychiatric disorders impact the spectrum of relevant outcomes.

Getting back to the dilemma faced by pregnant women who really need medication to sustain emotional well-being, there simply is no perfect answer. No decision is perfect or risk free. What we can hope is that we’ll have personalized approaches that take into account the best available data and the patient’s individual situation and wishes. We’ve already come a long way toward meeting that goal, and I’m optimistic about where we’re going.

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, which provides information resources and conducts clinical care and research in reproductive mental health. He has been a consultant to manufacturers of psychiatric medications.

Perception of risk

Every year, numerous new medicines are approved by the FDA without data in pregnancy. Animal studies may show a problem that doesn’t appear in humans, or as was the case with thalidomide, the problem may not be apparent in animals and show up later in humans. There are many drugs that are safe in pregnancy, but women are understandably afraid of the potential impact on fetal development.

While my colleagues have presented the advances we’ve made in understanding the actual risks of medications during the prenatal period, it’s also important to focus on the perception of risk and to recognize that the reality and the perception can be vastly different.

At the same time, we began to ask women, using a visual analog scale, what would be their trend toward continuing or terminating pregnancy? Over several studies, we found that the likelihood of termination was high, and certainly much higher than was supported by the evidence of actual harm to the fetus. Specifically, if a woman received information about the safety of the drug and she still gave more than a 50% probability of terminating the pregnancy when surveyed, there was a good chance that she would terminate the pregnancy.

When you consider that most of the drugs that women are commonly prescribed in pregnancy – from most painkillers to antidepressants – are not known to cause malformations in pregnancy, you begin to see how problematic an inflated perception of risk can become.

But we see different trends in women with serious and chronic health problems, such as lupus or epilepsy. These women are typically under the care of a subspecialist, who in many cases has developed a significant knowledge base and comfort level around prescribing the drugs in this area and is able to communicate more clearly to patients both the risks to the fetus and the consequences of failure to treat their condition.

So clearly, the role of the physician and the ob.gyn. in particular is critical. It’s no secret that physicians face a negative legal climate that encourages defensive medicine and that they are often hesitant to tell women, without reservation, that it is okay to take a drug. But we must all remember that it is very easy to cause a woman not to take a medication in pregnancy and often that’s not what’s best for her health. Many women now postpone the age of starting a family and more have chronic conditions that require treatment. The idea of not treating certain conditions for the length of a pregnancy is not always a viable option. Yet there are quite a few women who would consider termination “just to be on the safe side.” That must be taken very seriously by the medical profession.

Dr. Koren is a professor of physiology/pharmacology at Western University, London, Ont., and a professor of medicine at Tel Aviv University. He is the founder of the Motherisk Program. He reported being a paid consultant for Duchesnay and Novartis.

Editor’s note: As Ob.Gyn. News celebrates its 50th anniversary, we wanted to know how far the medical community has come in identifying and mitigating drug risks during pregnancy and in the postpartum period. In this article, our four expert columnists share their experiences trying to find and interpret critical pregnancy data, as well as how they weigh the potential risks and benefits for their patients.

The search for information

The biggest advance in the past 50 years is the availability of information, even though limited, relating to the effects of drugs in pregnancy and lactation. In the first few years of this period, it was a daunting task to obtain this information. I can recall spending hours in the hospital’s medical library going through huge volumes of Index Medicus to obtain references that the library could order for me. The appearance of Thomas H. Shepard’s first edition (Catalog of Teratogenic Agents) in 1973 was a step forward and in 1977, O.P. Heinonen and colleagues’ book (Birth Defects and Drugs in Pregnancy) was helpful.

Although all of the above sources were helpful, any book in an evolving field will not have the newest information. Two important services, TERIS and Reprotox, were started to allow clinicians to contact them for up-to-date data. Nevertheless, the biggest change was the availability of current information from the U.S. National Library of Medicine via Toxnet, PubMed, and LactMed, relating to the effects of drugs in pregnancy and lactation.

My method is to ask three questions. First, are there other drugs with a similar mechanism of action that have some human data? In most cases, the answer to this question is no, but even when there are data, it is typically very limited. Second, does the drug cross the human placenta? The answer is typically based on the molecular weight. Any drug with a molecular weight less than 1,000 daltons probably crosses. In the second half of pregnancy, especially in the third trimester, almost every drug crosses. Third, do the animal pregnancy data predict embryo/fetal risk? It was thought that it could if the dose causing harm was less than or equal to 10 times the human dose based on BSA or AUC and there were no signs of maternal toxicity. However, using data from my 10th edition, I and eight coauthors, all of whom are knowledgeable on the effects of drugs in pregnancy, found that the animal data for 311 drugs raised the possibility of human embryo-fetal harm that current data confirmed in only 75 (24%) of the drugs (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Dec;213[6]:810-5).

The system needs to be fixed. One method is to give the Food and Drug Administration the authority to require manufacturers of drugs likely to be used in pregnancy to gather and publish data on their use in pregnancy. That sounds reasonable, but will it ever occur?

Mr. Briggs is clinical professor of pharmacy at the University of California, San Francisco, and adjunct professor of pharmacy at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, and Washington State University, Spokane. He is coauthor of “Drugs in Pregnancy and Lactation,” and coeditor of “Diseases, Complications, and Drug Therapy in Obstetrics.” He has no relevant financial disclosures.

Learning the lessons of the past

During the last 50 years, two of the most potent known human teratogens, thalidomide and isotretinoin, became available for prescription in the United States. Thanks to the efforts of Frances Kelsey, MD, PhD, at the FDA, the initial application for approval of thalidomide in the United States was denied in the early 1960s. Subsequently, based on evidence from other countries where thalidomide was marketed that the drug can cause a pattern of serious birth defects, a very strict pregnancy prevention program was implemented when the drug was finally approved in the United States in 2006.

Over the last 50 years, we have also seen an important evolution in our ability to conduct pregnancy exposure safety studies. Though we still have limited ability to conduct clinical trials in pregnant women, the need for good quality observational studies has become more widely accepted. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Birth Defects Prevention Study (now in its most recent iteration known as BD STEPS) has been one very important source of data on the safety of a wide variety of medications. Using a case-control study design, women who have delivered infants with specific birth defects and comparison women who have delivered non-malformed infants are interviewed about their exposures in pregnancy. These data have been extremely helpful in generating new hypotheses, confirming or refuting findings from other studies, and in testing hypotheses regarding the safety of medications widely used in women of reproductive age. These analyses, for example, have contributed to the large body of literature now available on the safety of antidepressant medications in pregnancy.

At the same time, in the last 30 years, we have seen a tremendous increase in the number of pregnancy registries required or recommended upon approval of a new drug in the United States. These registry studies, while challenging to complete in a timely manner, have steadily improved in terms of rigor, and several disease-based pregnancy exposure studies have been implemented, which have allowed us to better understand the comparative risks or safety of anticonvulsants and antiretroviral drugs, to name a few.

It is important to note that with all these advances in the last 50 years, we still have a huge gap in knowledge about medication safety in pregnancy and lactation. Recent reviews suggest that more than 80% of drugs currently marketed have insufficient or no data available. If we include over-the-counter medications, the knowledge gap grows larger. With the 2014 approval of the long-awaited Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule, clinicians are now beginning to experience the elimination of the old A-B-C-D-X category system for pregnancy safety. In its place, data-driven product labels are required. These are expected to provide the clinician with a clear summary of the relevant studies for a given medication, and to place these in the context of the background risks for the underlying maternal disease being treated, as well as the population risks. However, it is painfully clear that we have a long way to go to generate the needed, high-quality data, to populate those labels.

Dr. Chambers is a professor of pediatrics and director of clinical research at Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego, and associate director of the Clinical and Translational Research Institute at the University of California, San Diego. She is director of MotherToBaby California, a past president of the Organization of Teratology Information Specialists, and past president of the Teratology Society. She has no relevant financial disclosures.

Moving toward personalized medicine

Nowhere is a lack of actionable data more pronounced than in the impact of mental health drugs in pregnancy.

As Dr. Briggs and Dr. Chambers have outlined, the quality of data regarding the reproductive safety of medications across the therapeutic spectrum has historically been fair at best. The methodology and the rigor has been sparse and to a large extent, in psychiatry, we were only able to look for signals of concern. Prior to the late 1980s and early 1990s, there was little to guide clinicians on the safety of even very commonly used psychiatric medications during pregnancy. The health implications for women of reproductive age are extraordinary and yet that urgency was not matched by the level of investigation until more recently.

In psychiatry, we have rapidly improving data informing women about the risk for major congenital malformations. The clinical dilemma of weighing the necessity to stay on a medication to prevent relapse of a psychiatric disorder with the potential risk of malformation in the fetus is a wrenching one for the mother-to-be. Only good information can help patients, together with their physician, make collaborative decisions that make sense for them. Given the same information and the same severity of illness, women will make different decisions, and that’s a good thing. The calculus couples use to make these private decisions is unique to those involved. But they are able to move through the process because they have a platform of high-quality information.

So where do we go in the future? We need to get beyond the question of risk of major malformations and move toward understanding the long-term neurodevelopmental implications of prenatal exposures – whether such exposures confer risk or are even potentially salutary. One needs only look at the vast body of literature regarding fetal exposure to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) to observe the realization of this trend. When it comes to SSRIs, a fairly clear picture has emerged that they pose little absolute risk in terms of congenital malformations. What is missing is how SSRIs impact a child’s learning and development at age 3, 5, and 10. There have been a few studies in this area, but not a single, large prospective study that accurately quantifies both exposure to SSRIs and maternal psychiatric illness during pregnancy.

I expect that the future will also bring a greater understanding of the impact of untreated mental illness on the risk for obstetrical, neonatal, and longer-term neurodevelopmental outcomes. Most of the safety concerns have centered around the effect of fetal exposure to medications, but we also need to better understand how untreated psychiatric disorders impact the spectrum of relevant outcomes.

Getting back to the dilemma faced by pregnant women who really need medication to sustain emotional well-being, there simply is no perfect answer. No decision is perfect or risk free. What we can hope is that we’ll have personalized approaches that take into account the best available data and the patient’s individual situation and wishes. We’ve already come a long way toward meeting that goal, and I’m optimistic about where we’re going.

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, which provides information resources and conducts clinical care and research in reproductive mental health. He has been a consultant to manufacturers of psychiatric medications.

Perception of risk

Every year, numerous new medicines are approved by the FDA without data in pregnancy. Animal studies may show a problem that doesn’t appear in humans, or as was the case with thalidomide, the problem may not be apparent in animals and show up later in humans. There are many drugs that are safe in pregnancy, but women are understandably afraid of the potential impact on fetal development.

While my colleagues have presented the advances we’ve made in understanding the actual risks of medications during the prenatal period, it’s also important to focus on the perception of risk and to recognize that the reality and the perception can be vastly different.

At the same time, we began to ask women, using a visual analog scale, what would be their trend toward continuing or terminating pregnancy? Over several studies, we found that the likelihood of termination was high, and certainly much higher than was supported by the evidence of actual harm to the fetus. Specifically, if a woman received information about the safety of the drug and she still gave more than a 50% probability of terminating the pregnancy when surveyed, there was a good chance that she would terminate the pregnancy.

When you consider that most of the drugs that women are commonly prescribed in pregnancy – from most painkillers to antidepressants – are not known to cause malformations in pregnancy, you begin to see how problematic an inflated perception of risk can become.

But we see different trends in women with serious and chronic health problems, such as lupus or epilepsy. These women are typically under the care of a subspecialist, who in many cases has developed a significant knowledge base and comfort level around prescribing the drugs in this area and is able to communicate more clearly to patients both the risks to the fetus and the consequences of failure to treat their condition.

So clearly, the role of the physician and the ob.gyn. in particular is critical. It’s no secret that physicians face a negative legal climate that encourages defensive medicine and that they are often hesitant to tell women, without reservation, that it is okay to take a drug. But we must all remember that it is very easy to cause a woman not to take a medication in pregnancy and often that’s not what’s best for her health. Many women now postpone the age of starting a family and more have chronic conditions that require treatment. The idea of not treating certain conditions for the length of a pregnancy is not always a viable option. Yet there are quite a few women who would consider termination “just to be on the safe side.” That must be taken very seriously by the medical profession.

Dr. Koren is a professor of physiology/pharmacology at Western University, London, Ont., and a professor of medicine at Tel Aviv University. He is the founder of the Motherisk Program. He reported being a paid consultant for Duchesnay and Novartis.

Editor’s note: As Ob.Gyn. News celebrates its 50th anniversary, we wanted to know how far the medical community has come in identifying and mitigating drug risks during pregnancy and in the postpartum period. In this article, our four expert columnists share their experiences trying to find and interpret critical pregnancy data, as well as how they weigh the potential risks and benefits for their patients.

The search for information

The biggest advance in the past 50 years is the availability of information, even though limited, relating to the effects of drugs in pregnancy and lactation. In the first few years of this period, it was a daunting task to obtain this information. I can recall spending hours in the hospital’s medical library going through huge volumes of Index Medicus to obtain references that the library could order for me. The appearance of Thomas H. Shepard’s first edition (Catalog of Teratogenic Agents) in 1973 was a step forward and in 1977, O.P. Heinonen and colleagues’ book (Birth Defects and Drugs in Pregnancy) was helpful.

Although all of the above sources were helpful, any book in an evolving field will not have the newest information. Two important services, TERIS and Reprotox, were started to allow clinicians to contact them for up-to-date data. Nevertheless, the biggest change was the availability of current information from the U.S. National Library of Medicine via Toxnet, PubMed, and LactMed, relating to the effects of drugs in pregnancy and lactation.

My method is to ask three questions. First, are there other drugs with a similar mechanism of action that have some human data? In most cases, the answer to this question is no, but even when there are data, it is typically very limited. Second, does the drug cross the human placenta? The answer is typically based on the molecular weight. Any drug with a molecular weight less than 1,000 daltons probably crosses. In the second half of pregnancy, especially in the third trimester, almost every drug crosses. Third, do the animal pregnancy data predict embryo/fetal risk? It was thought that it could if the dose causing harm was less than or equal to 10 times the human dose based on BSA or AUC and there were no signs of maternal toxicity. However, using data from my 10th edition, I and eight coauthors, all of whom are knowledgeable on the effects of drugs in pregnancy, found that the animal data for 311 drugs raised the possibility of human embryo-fetal harm that current data confirmed in only 75 (24%) of the drugs (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Dec;213[6]:810-5).

The system needs to be fixed. One method is to give the Food and Drug Administration the authority to require manufacturers of drugs likely to be used in pregnancy to gather and publish data on their use in pregnancy. That sounds reasonable, but will it ever occur?

Mr. Briggs is clinical professor of pharmacy at the University of California, San Francisco, and adjunct professor of pharmacy at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, and Washington State University, Spokane. He is coauthor of “Drugs in Pregnancy and Lactation,” and coeditor of “Diseases, Complications, and Drug Therapy in Obstetrics.” He has no relevant financial disclosures.

Learning the lessons of the past

During the last 50 years, two of the most potent known human teratogens, thalidomide and isotretinoin, became available for prescription in the United States. Thanks to the efforts of Frances Kelsey, MD, PhD, at the FDA, the initial application for approval of thalidomide in the United States was denied in the early 1960s. Subsequently, based on evidence from other countries where thalidomide was marketed that the drug can cause a pattern of serious birth defects, a very strict pregnancy prevention program was implemented when the drug was finally approved in the United States in 2006.

Over the last 50 years, we have also seen an important evolution in our ability to conduct pregnancy exposure safety studies. Though we still have limited ability to conduct clinical trials in pregnant women, the need for good quality observational studies has become more widely accepted. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Birth Defects Prevention Study (now in its most recent iteration known as BD STEPS) has been one very important source of data on the safety of a wide variety of medications. Using a case-control study design, women who have delivered infants with specific birth defects and comparison women who have delivered non-malformed infants are interviewed about their exposures in pregnancy. These data have been extremely helpful in generating new hypotheses, confirming or refuting findings from other studies, and in testing hypotheses regarding the safety of medications widely used in women of reproductive age. These analyses, for example, have contributed to the large body of literature now available on the safety of antidepressant medications in pregnancy.

At the same time, in the last 30 years, we have seen a tremendous increase in the number of pregnancy registries required or recommended upon approval of a new drug in the United States. These registry studies, while challenging to complete in a timely manner, have steadily improved in terms of rigor, and several disease-based pregnancy exposure studies have been implemented, which have allowed us to better understand the comparative risks or safety of anticonvulsants and antiretroviral drugs, to name a few.

It is important to note that with all these advances in the last 50 years, we still have a huge gap in knowledge about medication safety in pregnancy and lactation. Recent reviews suggest that more than 80% of drugs currently marketed have insufficient or no data available. If we include over-the-counter medications, the knowledge gap grows larger. With the 2014 approval of the long-awaited Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule, clinicians are now beginning to experience the elimination of the old A-B-C-D-X category system for pregnancy safety. In its place, data-driven product labels are required. These are expected to provide the clinician with a clear summary of the relevant studies for a given medication, and to place these in the context of the background risks for the underlying maternal disease being treated, as well as the population risks. However, it is painfully clear that we have a long way to go to generate the needed, high-quality data, to populate those labels.

Dr. Chambers is a professor of pediatrics and director of clinical research at Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego, and associate director of the Clinical and Translational Research Institute at the University of California, San Diego. She is director of MotherToBaby California, a past president of the Organization of Teratology Information Specialists, and past president of the Teratology Society. She has no relevant financial disclosures.

Moving toward personalized medicine

Nowhere is a lack of actionable data more pronounced than in the impact of mental health drugs in pregnancy.

As Dr. Briggs and Dr. Chambers have outlined, the quality of data regarding the reproductive safety of medications across the therapeutic spectrum has historically been fair at best. The methodology and the rigor has been sparse and to a large extent, in psychiatry, we were only able to look for signals of concern. Prior to the late 1980s and early 1990s, there was little to guide clinicians on the safety of even very commonly used psychiatric medications during pregnancy. The health implications for women of reproductive age are extraordinary and yet that urgency was not matched by the level of investigation until more recently.

In psychiatry, we have rapidly improving data informing women about the risk for major congenital malformations. The clinical dilemma of weighing the necessity to stay on a medication to prevent relapse of a psychiatric disorder with the potential risk of malformation in the fetus is a wrenching one for the mother-to-be. Only good information can help patients, together with their physician, make collaborative decisions that make sense for them. Given the same information and the same severity of illness, women will make different decisions, and that’s a good thing. The calculus couples use to make these private decisions is unique to those involved. But they are able to move through the process because they have a platform of high-quality information.

So where do we go in the future? We need to get beyond the question of risk of major malformations and move toward understanding the long-term neurodevelopmental implications of prenatal exposures – whether such exposures confer risk or are even potentially salutary. One needs only look at the vast body of literature regarding fetal exposure to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) to observe the realization of this trend. When it comes to SSRIs, a fairly clear picture has emerged that they pose little absolute risk in terms of congenital malformations. What is missing is how SSRIs impact a child’s learning and development at age 3, 5, and 10. There have been a few studies in this area, but not a single, large prospective study that accurately quantifies both exposure to SSRIs and maternal psychiatric illness during pregnancy.

I expect that the future will also bring a greater understanding of the impact of untreated mental illness on the risk for obstetrical, neonatal, and longer-term neurodevelopmental outcomes. Most of the safety concerns have centered around the effect of fetal exposure to medications, but we also need to better understand how untreated psychiatric disorders impact the spectrum of relevant outcomes.

Getting back to the dilemma faced by pregnant women who really need medication to sustain emotional well-being, there simply is no perfect answer. No decision is perfect or risk free. What we can hope is that we’ll have personalized approaches that take into account the best available data and the patient’s individual situation and wishes. We’ve already come a long way toward meeting that goal, and I’m optimistic about where we’re going.

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, which provides information resources and conducts clinical care and research in reproductive mental health. He has been a consultant to manufacturers of psychiatric medications.

Perception of risk

Every year, numerous new medicines are approved by the FDA without data in pregnancy. Animal studies may show a problem that doesn’t appear in humans, or as was the case with thalidomide, the problem may not be apparent in animals and show up later in humans. There are many drugs that are safe in pregnancy, but women are understandably afraid of the potential impact on fetal development.

While my colleagues have presented the advances we’ve made in understanding the actual risks of medications during the prenatal period, it’s also important to focus on the perception of risk and to recognize that the reality and the perception can be vastly different.

At the same time, we began to ask women, using a visual analog scale, what would be their trend toward continuing or terminating pregnancy? Over several studies, we found that the likelihood of termination was high, and certainly much higher than was supported by the evidence of actual harm to the fetus. Specifically, if a woman received information about the safety of the drug and she still gave more than a 50% probability of terminating the pregnancy when surveyed, there was a good chance that she would terminate the pregnancy.

When you consider that most of the drugs that women are commonly prescribed in pregnancy – from most painkillers to antidepressants – are not known to cause malformations in pregnancy, you begin to see how problematic an inflated perception of risk can become.

But we see different trends in women with serious and chronic health problems, such as lupus or epilepsy. These women are typically under the care of a subspecialist, who in many cases has developed a significant knowledge base and comfort level around prescribing the drugs in this area and is able to communicate more clearly to patients both the risks to the fetus and the consequences of failure to treat their condition.

So clearly, the role of the physician and the ob.gyn. in particular is critical. It’s no secret that physicians face a negative legal climate that encourages defensive medicine and that they are often hesitant to tell women, without reservation, that it is okay to take a drug. But we must all remember that it is very easy to cause a woman not to take a medication in pregnancy and often that’s not what’s best for her health. Many women now postpone the age of starting a family and more have chronic conditions that require treatment. The idea of not treating certain conditions for the length of a pregnancy is not always a viable option. Yet there are quite a few women who would consider termination “just to be on the safe side.” That must be taken very seriously by the medical profession.

Dr. Koren is a professor of physiology/pharmacology at Western University, London, Ont., and a professor of medicine at Tel Aviv University. He is the founder of the Motherisk Program. He reported being a paid consultant for Duchesnay and Novartis.

Early days of IVF marked by competition, innovation

In 1978, when England’s Louise Brown became the world’s first baby born through in vitro fertilization, physicians at academic centers all over the United States scrambled to figure out how they, too, could provide IVF to the thousands of infertile couples for whom nothing else had worked.

Interest in IVF was strong even before British physiologist Robert Edwards and gynecologist Patrick Steptoe announced their success. “We knew that IVF was being developed, that it had been accomplished in animals, and ultimately we knew it was going to succeed in humans,” said reproductive endocrinologist Zev Rosenwaks, MD, of the Weill Cornell Center for Reproductive Medicine in New York.

In the late 1970s, “we were able to help only about two-thirds of couples with infertility, either with tubal surgery, insemination – often with donor sperm – or ovulation induction. A full third could not be helped. We predicted that IVF would allow us to treat virtually everyone,” Dr. Rosenwaks said.

But even after the first IVF birth, information on the revolutionary procedure remained frustratingly scarce.

“Edwards and Steptoe would talk to nobody,” said Richard Marrs, MD, a reproductive endocrinologist and infertility specialist in Los Angeles.

And federal research support for “test-tube babies,” as IVF was known in the media then, was nil thanks to a ban on government-funded human embryo research that persists to this day.

The U.S. physicians who took part in the rush to achieve an IVF birth – most of them young fellows at the time – recall a period of improvisation, collaboration, shoestring budgets, and surprise findings.

“People who just started 10 or even 20 years ago don’t realize what it took for us to learn how to go about doing IVF,” said Dr. Rosenwaks, who in the first years of IVF worked closely with Dr. Howard Jones and Dr. Georgeanna Jones, the first team in the U.S. to announce an IVF baby.

Labs in closets

In the late 1970s, Dr. Marrs, then a fellow at the University of Southern California, was focused on surgical methods to treat infertility – and demand was sky-high. Intrauterine devices used in the 1970s left many women with severe scarring and inflammation of the fallopian tubes.

“I was very surgically oriented,” Dr. Marrs said. “I thought I could fix any disaster in the pelvis that was put in front of me, especially with microsurgery.”

After the news of IVF success in England, Dr. Marrs threw himself into a side project at a nearby cancer center, working on single-cell cultures. “I thought if I could grow tumor cells, I could one day grow embryos,” he said.

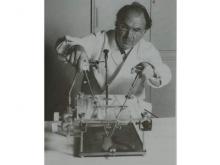

A year later, Dr. Marrs set up the first IVF lab at USC – in a storage closet. “I sterilized the place and that was our first IVF lab, literally a closet with an incubator and a microscope.” Its budget was accordingly thin, as the director at the time felt certain that IVF was a dead end. To fund his work, Dr. Marrs asked IVF candidate patients for research donations in lieu of payment.

But before Dr. Marrs attempted to perform his first IVF, two centers in Australia announced their own IVF babies. “I decided I really needed to go see someone who had had a baby,” he said. He used his vacation time to fly to Melbourne, shuttling between two competing clinics that were “four blocks apart and wouldn’t even talk to each other,” he recalled.

Over 6 weeks, “I learned how to stimulate, how to time ovulation. I watched the PhDs in the lab – how they handled the eggs and the sperm, what the conditions were, the incubator settings,” he said.

The first IVF babies in the United States were born only months apart: The first, in December 1981, was at the Jones Institute for Reproductive Medicine in Norfolk, Va., where Dr. Rosenwaks served as the first director.

The second baby born was at USC. After that, “we had 4,000 women on a waiting list, all under age 35,” Dr. Marrs said. The Jones Institute reportedly had 5,000.

As demand soared and more IVF babies arrived, the cloak of secrecy surrounding the procedure started to lift. British, Australian, and U.S. clinicians started getting together regularly. “We would pick a spot in the world, present our data: what we’d done, how many cycles, what we used for stimulation, when we took the eggs out,” Dr. Marrs said. “I don’t know how many hundreds of thousands of miles I flew in the first years of IVF, because it was the only way I could get information. We would literally stay up all night talking.”

Answering safety questions

Alan H. DeCherney, MD, currently an infertility researcher at the National Institutes of Health, started Yale University’s IVF program at around the same time Dr. Marrs and the Joneses were starting theirs. Yale already had a large infertility practice, and only academic centers had the laboratory resources and skilled staff needed to attempt IVF in those years.

In 1983, when Yale announced the birth of its first IVF baby – the fifth in the United States – Dr. DeCherney was starting to think about measuring outcomes, as there was concern over the potential for congenital anomalies related to IVF. “This was such a change in the way conception occurred, people were afraid that all kinds of crazy things would happen,” he said.

One concern was about ovarian stimulation with fertility drugs or gonadotropins. The earliest efforts – including by Dr. Steptoe and Dr. Edwards – used no drugs, instead trying to pinpoint the moment of natural egg release by measuring a woman’s hormone levels constantly, but these proved disappointing. Use of clomiphene citrate and human menopausal gonadotropin allowed for more control over timing, and for multiple mature eggs to be harvested at once.

But there were still many unanswered questions related to these agents’ safety and dosing, both for women and for babies.

When the NIH refused to fund a study of IVF outcomes, Dr. DeCherney and Dr. Marrs collaborated on a registry funded by a gonadotropin maker. “The drug company didn’t want to be associated with some terrible abnormal outcomes,” Dr. DeCherney recalled, though by then, “there were 10, maybe even 20 babies around the world, and they seemed to be fine,” he said.

The first registry results affirmed no changes in the rate of congenital abnormalities. (Larger, more recent studies have shown a small but significant elevation in birth defect risk associated with IVF.) A few years later, ovarian stimulation was adjusted to correspond with ovarian reserve, reducing the risk of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome.

But even by the late 1980s, success rates for IVF per attempted cycle were still low overall, leading many critics, even within the profession, to accuse practitioners of misleading couples. Charles E. Miller, MD, an infertility specialist in Chicago, recalled an early investigation by a major newspaper “that looked at all the IVF clinics in Chicago and found the chances of having a baby was under 3%.”

It was true, Dr. Miller acknowledged – “the rates were dismal. But remember that IVF at the time was still considered a procedure of last resort.” Complex diagnostic testing to determine the cause of infertility, surgery, and fertility drugs all came first.

Some important innovations would soon change that and turn IVF into a mainstay of infertility treatment that could help women not only with damaged tubes but also with ovarian failure, low ovarian reserve, or dense pelvic adhesions. Even some types of male factor infertility would find an answer in IVF, by way of intracytoplasmic sperm transfer.

Eggs without surgery

Laparoscopic egg retrieval was the norm in the first decade of IVF. “We went through the belly button, allowing us to directly visualize the ovary and see whether ovulation had already occurred or we had to retrieve it by introducing a needle into the follicle,” Dr. Rosenwaks recalled.

“Some of us were doing 6 or even 10 laparoscopies a day, and it was physically quite challenging,” he said. “There were no video screens in those days. You had to bend over the scope.” And it was worse still for patients, who had to endure multiple surgeries.

Though egg and embryo cryopreservation were already being worked on, it would be years before these techniques were optimized, giving women more chances from a single retrieval of oocytes.

Finding a less invasive means of retrieving eggs was crucial.

Maria Bustillo, MD, an infertility specialist in Miami, recalled being criticized by peers when she and her then-colleagues at the Genetics & IVF Institute in Fairfax, Va., began retrieving eggs via a needle placed in the vagina, using abdominal ultrasound as a guide.

While the technique was far less invasive than laparoscopy, “we were doing it semi-blindly, and were told it was dangerous,” Dr. Bustillo said.

But these freehand ultrasound retrievals paved the way for what would become a revolutionary advance – the vaginal ultrasound probe, which by the end of the 1980s made nonsurgical extraction of eggs the norm.

Dr. Marrs recalled receiving a prototype of a vaginal ultrasound probe, in the mid-1980s, and finding patients unwilling to use it, except one who relented only because she had an empty bladder. Abdominal ultrasonography required a full bladder to work.

“It was as though somebody had removed the cloud cover,” he said. “I couldn’t believe it. I could see everything: her ovaries, tiny follicles, the uterus.”

Later probes were fitted with a needle and aspirator to retrieve eggs. Multiple IVF cycles no longer meant multiple surgeries, and the less-invasive procedure helped in recruiting egg donors, allowing women with ovarian disease or low ovarian reserves, including older women, to receive IVF.

“It didn’t make sense for a volunteer to go through a surgery, especially back in the early ’80s when the results were not all that great,” Dr. Bustillo said.

Improving ‘home brews’

The culture media in which embryos were grown was another strong factor limiting the success rates of early IVF. James Toner, MD, PhD, an IVF specialist in Atlanta, called the early media “home brews.”

“Everyone made them themselves,” said Dr. Toner, who spent 15 years at the Jones Institute. “You had to do a hamster or mouse embryo test on every batch to make sure embryos would grow.” And often they did not.

Poor success rates resulted in the emergence of alternative procedures: GIFT (gamete intrafallopian transfer) and ZIFT (zygote intrafallopian transfer). Both aimed to get embryos back into the patient as soon as possible, with the thought that the natural environment offered a better chance for success.

But advances in culture media allowed more time for embryos to be observed. With longer development, “you could do a better job selecting the ones that had a chance, and de-selecting those with no chance,” Dr. Toner said.

This also meant fewer embryos could be transferred back into patients, lowering the likelihood of multiples. Ultimately, for young women, single-embryo transfer would become the norm. “The problem of multiple pregnancy that we used to have no longer exists for IVF,” Dr. Toner said.

Allowing embryos to reach the blastocyst stage – day 5 or 6 – opened other, previously unthinkable possibilities: placing embryos directly into the uterus, without surgery, and pre-implementation genetic screening for abnormalities.

“As the cell number went up, the idea that you could do a genetic test with minimal impact on the embryo eventually became true,” Dr. Toner said.

A genetic revolution?

While many important IVF innovations were achieved in countries with staunch government support, one of the remarkable things about IVF’s evolution in the United States is that so many occurred with virtually none.

By the mid-1990s, most of the early practitioners had moved from academic settings into private practice, though they continued to publish. “After a while it didn’t help to be in academics. It just sort of slowed you down. Because you weren’t going to get any [government] money anyway, you might as well be in a place that’s a little more nimble,” Dr. Toner said.

At the same time, he said, IVF remains a costly, usually unreimbursed procedure – limiting patients’ willingness to take part in randomized trials. “IVF research is built more on cohort studies.”

Most of the current research focus in IVF is on possibilities for genetic screening. Dr. Miller said that rapid DNA sequencing is allowing specialists to “look at more, pick up more abnormalities. That will continue to improve so that we will be able to see virtually everything.”

But he cautioned there is still much to be done in IVF apart from the genetics – he’s concerned, he said, that the field has moved too far from its surgical origins, and is working with the academic societies to encourage more surgical training.

“We don’t do the same work we did before on fallopian tubes, which is good,” Dr. Miller said, noting that there have been many advances, particularly minimally invasive surgeries in the uterus or ovaries, that have occurred parallel to IVF and can improve success rates. “I think we have a better understanding of what kind of patients require surgical treatments and what kind of surgeries can help enhance fertility, and also what not to do.”

Dr. Bustillo said that “cytogenetics is wonderful, but not everything. You have embryos that are genetically normal and still don’t implant. There’s a lot of work to be done on the interaction between the mother and the embryo.”

Dr. Marrs said that even safety questions related to stimulation have yet to be fully answered. “I’ve always been a big believer that lower is better, but we need to know whether stimulation creates genetic abnormalities and whether less stimulation produces fewer – and we need more data to prove it,” he said. Dr. Marrs is an investigator on a national randomized trial comparing outcomes from IVF with standard-dose and ultra-low dose stimulation.

Access, income, and age

The IVF pioneers agree broadly that access to IVF is nowhere near what it should be in the United States, where only 15 states mandate any insurance coverage for infertility.

“Our limited access to care is a crime,” Dr. Toner said. “People who, through no fault of their own, find themselves infertile are asked to write a check for $15,000 to get pregnant. That’s not fair.”

Dr. DeCherney called access “an ethical issue, because who gets IVF? People with higher incomes. And if IVF allows you to select better embryos – whatever that means – it gives that group another advantage.”

Dr. Toner warned that the push toward genetic testing of embryos, especially in the absence of known hereditary disease, could create new problems for the profession – not unlike in the early days of IVF, when the Jones Institute and other clinics were picketed over the specter of “test tube babies.”