User login

Slowing down

This past Labor Day weekend, I did something radical. I slowed down. Way down. My wife slowed down with me, which helped. We spent the weekend close to home walking, talking, reading, contemplating, planning, assessing, doing puzzles and crosswords, and imbibing a craft beer or two, slowly, of course. Why? Because of Adam Grant, PhD, the organizational psychologist at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School of Business, Philadelphia. I had recently reread his 2016 book I’m a big fan; he’s one of those professors who makes you fervently wish you were a student again, someone who will provoke you and challenge your way of thinking.

Dr. Grant’s basic premise, which he has proved through research, is that procrastination boosts productivity. Here’s how: Let’s say you’re facing a challenge or difficult task. He says to start working on it immediately, then take some time away for reflection. This “quick to start and slow to finish” method allows your brain to continually percolate on the problem. An incomplete task stays partially active in your brain. When you come back to it you often see it with fresh eyes. You will experience your highest productivity when you are toggling between these two modes.

This makes sense, and Dr. Grant cites numerous examples from Leonardo da Vinci to the founders of Warby-Parker, as examples of success. But how can it benefit physicians? Many of us are “precrastinators,” people who tend to complete or at least begin tasks as soon as possible, even when it’s unnecessary or not urgent. Unlike some jobs in which it’s easier to take a break from a project and return to it with more creative solutions, we often are racing against a clock to see more patients, read more slides, answer more emails, and make more phone calls. We are perpetually frenetic, which is not conducive to original thinking.

If this sounds like you, then you are likely to benefit from deliberate procrastination. Here are a few ways to slow down:

- Put it on your calendar. Yes, I see the irony, but it works. Start by scheduling one hour a week where you are to accomplish nothing. You can fill this time with whatever your mind wants to do at that moment.

- When faced with a diagnostic dilemma or treatment failure, resist the urge to solve that problem in that moment. Save that note for later, tell the patient you will call him back or bring him back for a visit later. Even if you’re not actively working on it, it will incubate somewhere in your brain, allowing more divergent thought processes to take over. It’s a little like trying to solve a crossword that seems impossible in the moment and then answers suddenly appear without effort.

- Take up a hobby: Play the guitar, learn to make pasta, climb a big rock. When you are fully engaged in such pursuits it requires complete mental focus. When you revisit the difficult problem you’re working on, you will likely see it from different perspectives.

- Meditate: Meditation requires our brains and bodies to slow down. It can help reduce self-doubt and criticism which stifle problem solving.

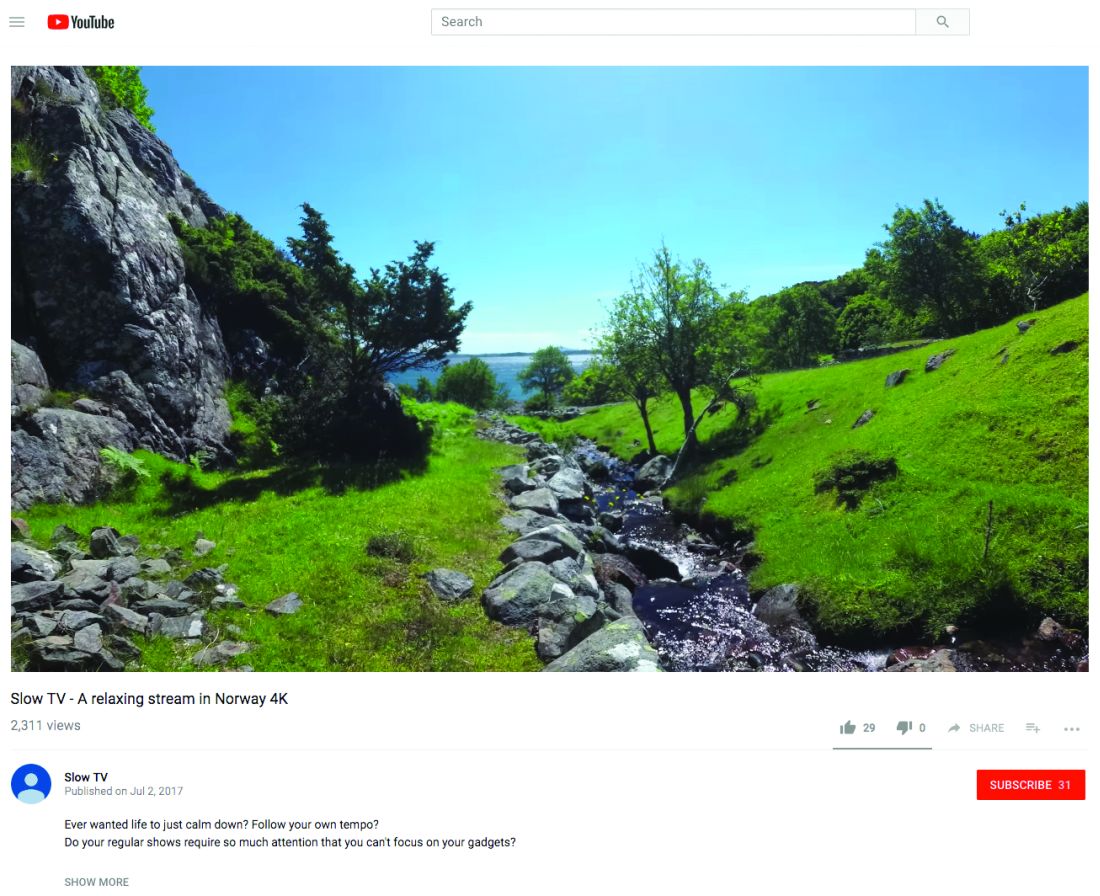

- Watch Slow TV. Slow TV is a Scandinavian phenomenon where you sit and watch meditative video such as a 7-hour train cam from Bergen, Norway, to Oslo. There’s no dialogue, no plot, no commercials. It’s just 7 hours of track and train and is weirdly comforting.

If you want to learn more, then when you get a chance, Google “slow living” and explore. Of course, some of you precrastinators probably have already started before finishing this column.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

This past Labor Day weekend, I did something radical. I slowed down. Way down. My wife slowed down with me, which helped. We spent the weekend close to home walking, talking, reading, contemplating, planning, assessing, doing puzzles and crosswords, and imbibing a craft beer or two, slowly, of course. Why? Because of Adam Grant, PhD, the organizational psychologist at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School of Business, Philadelphia. I had recently reread his 2016 book I’m a big fan; he’s one of those professors who makes you fervently wish you were a student again, someone who will provoke you and challenge your way of thinking.

Dr. Grant’s basic premise, which he has proved through research, is that procrastination boosts productivity. Here’s how: Let’s say you’re facing a challenge or difficult task. He says to start working on it immediately, then take some time away for reflection. This “quick to start and slow to finish” method allows your brain to continually percolate on the problem. An incomplete task stays partially active in your brain. When you come back to it you often see it with fresh eyes. You will experience your highest productivity when you are toggling between these two modes.

This makes sense, and Dr. Grant cites numerous examples from Leonardo da Vinci to the founders of Warby-Parker, as examples of success. But how can it benefit physicians? Many of us are “precrastinators,” people who tend to complete or at least begin tasks as soon as possible, even when it’s unnecessary or not urgent. Unlike some jobs in which it’s easier to take a break from a project and return to it with more creative solutions, we often are racing against a clock to see more patients, read more slides, answer more emails, and make more phone calls. We are perpetually frenetic, which is not conducive to original thinking.

If this sounds like you, then you are likely to benefit from deliberate procrastination. Here are a few ways to slow down:

- Put it on your calendar. Yes, I see the irony, but it works. Start by scheduling one hour a week where you are to accomplish nothing. You can fill this time with whatever your mind wants to do at that moment.

- When faced with a diagnostic dilemma or treatment failure, resist the urge to solve that problem in that moment. Save that note for later, tell the patient you will call him back or bring him back for a visit later. Even if you’re not actively working on it, it will incubate somewhere in your brain, allowing more divergent thought processes to take over. It’s a little like trying to solve a crossword that seems impossible in the moment and then answers suddenly appear without effort.

- Take up a hobby: Play the guitar, learn to make pasta, climb a big rock. When you are fully engaged in such pursuits it requires complete mental focus. When you revisit the difficult problem you’re working on, you will likely see it from different perspectives.

- Meditate: Meditation requires our brains and bodies to slow down. It can help reduce self-doubt and criticism which stifle problem solving.

- Watch Slow TV. Slow TV is a Scandinavian phenomenon where you sit and watch meditative video such as a 7-hour train cam from Bergen, Norway, to Oslo. There’s no dialogue, no plot, no commercials. It’s just 7 hours of track and train and is weirdly comforting.

If you want to learn more, then when you get a chance, Google “slow living” and explore. Of course, some of you precrastinators probably have already started before finishing this column.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

This past Labor Day weekend, I did something radical. I slowed down. Way down. My wife slowed down with me, which helped. We spent the weekend close to home walking, talking, reading, contemplating, planning, assessing, doing puzzles and crosswords, and imbibing a craft beer or two, slowly, of course. Why? Because of Adam Grant, PhD, the organizational psychologist at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School of Business, Philadelphia. I had recently reread his 2016 book I’m a big fan; he’s one of those professors who makes you fervently wish you were a student again, someone who will provoke you and challenge your way of thinking.

Dr. Grant’s basic premise, which he has proved through research, is that procrastination boosts productivity. Here’s how: Let’s say you’re facing a challenge or difficult task. He says to start working on it immediately, then take some time away for reflection. This “quick to start and slow to finish” method allows your brain to continually percolate on the problem. An incomplete task stays partially active in your brain. When you come back to it you often see it with fresh eyes. You will experience your highest productivity when you are toggling between these two modes.

This makes sense, and Dr. Grant cites numerous examples from Leonardo da Vinci to the founders of Warby-Parker, as examples of success. But how can it benefit physicians? Many of us are “precrastinators,” people who tend to complete or at least begin tasks as soon as possible, even when it’s unnecessary or not urgent. Unlike some jobs in which it’s easier to take a break from a project and return to it with more creative solutions, we often are racing against a clock to see more patients, read more slides, answer more emails, and make more phone calls. We are perpetually frenetic, which is not conducive to original thinking.

If this sounds like you, then you are likely to benefit from deliberate procrastination. Here are a few ways to slow down:

- Put it on your calendar. Yes, I see the irony, but it works. Start by scheduling one hour a week where you are to accomplish nothing. You can fill this time with whatever your mind wants to do at that moment.

- When faced with a diagnostic dilemma or treatment failure, resist the urge to solve that problem in that moment. Save that note for later, tell the patient you will call him back or bring him back for a visit later. Even if you’re not actively working on it, it will incubate somewhere in your brain, allowing more divergent thought processes to take over. It’s a little like trying to solve a crossword that seems impossible in the moment and then answers suddenly appear without effort.

- Take up a hobby: Play the guitar, learn to make pasta, climb a big rock. When you are fully engaged in such pursuits it requires complete mental focus. When you revisit the difficult problem you’re working on, you will likely see it from different perspectives.

- Meditate: Meditation requires our brains and bodies to slow down. It can help reduce self-doubt and criticism which stifle problem solving.

- Watch Slow TV. Slow TV is a Scandinavian phenomenon where you sit and watch meditative video such as a 7-hour train cam from Bergen, Norway, to Oslo. There’s no dialogue, no plot, no commercials. It’s just 7 hours of track and train and is weirdly comforting.

If you want to learn more, then when you get a chance, Google “slow living” and explore. Of course, some of you precrastinators probably have already started before finishing this column.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

Creating positive patient experiences

Let’s start with an exercise, shall we? What was the last vacation you went on? How would you rate that vacation on a scale of 1-10?

How you came up with that score is likely not entirely reflective of your actual experience. Understanding how we remember experiences is critical for the work we do everyday.

My last vacation was in Alaska. I’d rate it a 9 out of 10. How did I come up with that score? It is not the mean score of the entire trip as you might expect. Rather, I took a shortcut and thought only about the highlights to come up with a number. We remember, and evaluate, our experiences as a series of discrete events. In considering these events, it is only the highs, the lows, and the transitions that matter. Think about the score you gave your vacation. What specific moments did you remember?

This phenomenon is not specific to vacations. It applies to all service experiences. When your patients evaluate you, they will ignore most of what occurred and focus on only a few moments. Fair or not, it is from these bits only that they will rate their entire experience. This information helps us devise strategies to achieve high satisfaction scores: Focus on the high points, address the low points, if any, and be sure the transitions are pleasant.

For example, a patient might come to see you for a procedure. It could be something positive, such as injection of cosmetic filler or something negative like a colonoscopy. Either way, being finished with the procedure will likely be the best part for them. Don’t rush this time; instead of quickly moving on, take a moment to acknowledge you’re done, how well the patient did, or how much better they will now look or feel. Engaging with your patient at this moment can improve the salience of their experience and increase the likelihood that she or he will remember the appointment favorably and rate you accordingly, if given the opportunity.

In the same way, if you are aware your patient has experienced something negative, try to respond to it right away. Acknowledge if she or he expressed frustration, such as a long wait or pain, then take a minute to address or reframe it. Blunting the severity of the service failure can blunt their recall of it. This will make it less likely that it becomes a memorable part of their experience.

Last, transitions matter. These are the moments when your patient shifts from one setting to another, such as arriving at your office, moving from the waiting room to the exam room, and wrapping up the visit with the receptionist. Many of these moments will be managed by your staff. Therefore, invest time reminding them of their importance and teaching them tips and techniques to help patients transition smoothly and to feel well cared for. There will likely be a wonderful return on investment for them, you and, most importantly, your patients.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

Let’s start with an exercise, shall we? What was the last vacation you went on? How would you rate that vacation on a scale of 1-10?

How you came up with that score is likely not entirely reflective of your actual experience. Understanding how we remember experiences is critical for the work we do everyday.

My last vacation was in Alaska. I’d rate it a 9 out of 10. How did I come up with that score? It is not the mean score of the entire trip as you might expect. Rather, I took a shortcut and thought only about the highlights to come up with a number. We remember, and evaluate, our experiences as a series of discrete events. In considering these events, it is only the highs, the lows, and the transitions that matter. Think about the score you gave your vacation. What specific moments did you remember?

This phenomenon is not specific to vacations. It applies to all service experiences. When your patients evaluate you, they will ignore most of what occurred and focus on only a few moments. Fair or not, it is from these bits only that they will rate their entire experience. This information helps us devise strategies to achieve high satisfaction scores: Focus on the high points, address the low points, if any, and be sure the transitions are pleasant.

For example, a patient might come to see you for a procedure. It could be something positive, such as injection of cosmetic filler or something negative like a colonoscopy. Either way, being finished with the procedure will likely be the best part for them. Don’t rush this time; instead of quickly moving on, take a moment to acknowledge you’re done, how well the patient did, or how much better they will now look or feel. Engaging with your patient at this moment can improve the salience of their experience and increase the likelihood that she or he will remember the appointment favorably and rate you accordingly, if given the opportunity.

In the same way, if you are aware your patient has experienced something negative, try to respond to it right away. Acknowledge if she or he expressed frustration, such as a long wait or pain, then take a minute to address or reframe it. Blunting the severity of the service failure can blunt their recall of it. This will make it less likely that it becomes a memorable part of their experience.

Last, transitions matter. These are the moments when your patient shifts from one setting to another, such as arriving at your office, moving from the waiting room to the exam room, and wrapping up the visit with the receptionist. Many of these moments will be managed by your staff. Therefore, invest time reminding them of their importance and teaching them tips and techniques to help patients transition smoothly and to feel well cared for. There will likely be a wonderful return on investment for them, you and, most importantly, your patients.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

Let’s start with an exercise, shall we? What was the last vacation you went on? How would you rate that vacation on a scale of 1-10?

How you came up with that score is likely not entirely reflective of your actual experience. Understanding how we remember experiences is critical for the work we do everyday.

My last vacation was in Alaska. I’d rate it a 9 out of 10. How did I come up with that score? It is not the mean score of the entire trip as you might expect. Rather, I took a shortcut and thought only about the highlights to come up with a number. We remember, and evaluate, our experiences as a series of discrete events. In considering these events, it is only the highs, the lows, and the transitions that matter. Think about the score you gave your vacation. What specific moments did you remember?

This phenomenon is not specific to vacations. It applies to all service experiences. When your patients evaluate you, they will ignore most of what occurred and focus on only a few moments. Fair or not, it is from these bits only that they will rate their entire experience. This information helps us devise strategies to achieve high satisfaction scores: Focus on the high points, address the low points, if any, and be sure the transitions are pleasant.

For example, a patient might come to see you for a procedure. It could be something positive, such as injection of cosmetic filler or something negative like a colonoscopy. Either way, being finished with the procedure will likely be the best part for them. Don’t rush this time; instead of quickly moving on, take a moment to acknowledge you’re done, how well the patient did, or how much better they will now look or feel. Engaging with your patient at this moment can improve the salience of their experience and increase the likelihood that she or he will remember the appointment favorably and rate you accordingly, if given the opportunity.

In the same way, if you are aware your patient has experienced something negative, try to respond to it right away. Acknowledge if she or he expressed frustration, such as a long wait or pain, then take a minute to address or reframe it. Blunting the severity of the service failure can blunt their recall of it. This will make it less likely that it becomes a memorable part of their experience.

Last, transitions matter. These are the moments when your patient shifts from one setting to another, such as arriving at your office, moving from the waiting room to the exam room, and wrapping up the visit with the receptionist. Many of these moments will be managed by your staff. Therefore, invest time reminding them of their importance and teaching them tips and techniques to help patients transition smoothly and to feel well cared for. There will likely be a wonderful return on investment for them, you and, most importantly, your patients.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

Tabata training

I’m in really good shape. Well, more like really not bad shape. I eat healthy food (see my previous column on diet) and work out nearly every day. I have done so for years. I’ve learned that working out doesn’t make much difference with my weight, but it makes a huge difference with my mood, even more so than meditating. That’s why I’ll never give it up.

My approach is to vary my routine, typically by month. I’ve done “BUD/S qualification” months where I do only push-ups, sit-ups, pull-ups, and runs to meet the minimum requirements for the Navy Seal Training. (It’s not as hard as you might think, although I’m pretty lenient on form.)

When I have an hour to exercise and I’m deep into a podcast, then I’ll just keep going. If I’m trying to work out a piece I’m writing, like this one, then I’ll go for a run along the harbor here in San Diego. If I have to catch an early flight or drive to LA for the day, then I might have only 15 minutes. In that instance, I do high-intensity sprints, also known as high-intensity interval training (HIIT). Although it’s hard to break a good sweat, these workouts are both challenging and rewarding.

Recently, I participated in a wonderful physician wellness program at Kaiser Permanente, San Diego, where, over several weeks, we learned about nutrition, practiced meditation, and did Tabatas. What’s a Tabata you ask? It’s a kick in the butt.

. Yup, it’s a 4-minute workout that consists of 20 seconds of all-out, maximum effort, followed by 10 seconds of rest. The specific move you do for Tabatas is up to you, but it’s recommended that it be the same move for all 4 minutes. I like burpees which work your entire body – you jump, you drop into a push-up position, you pull your feet back in, and jump again. (Check out a video on YouTube.)

When we started the class, I thought Tabatas would be too easy for a gym rat like me. Plus, there were pediatricians, and even radiologists there, so how hard could they be? Let’s just say I couldn’t sit for 2 days after my first session: That’s how hard.

Tabatas are also a quick way to torch calories. A study published in the Journal of Sports Science and Medicine in 2013 found subjects who performed a 20-minute Tabata session experienced improved cardiorespiratory endurance and increased calorie burn (J Sports Sci Med. 2013 Sep;12[3]: 612-3).

Sometimes on a Monday, which is typically my difficult day, I’ll break out a few burpees in my office between patients. The energy jolt is real, and unlike caffeine, doesn’t leave me shaky. Because Tabatas require physical and mental focus, they’re an effective way to clear your mind after a grueling patient visit or if you’re feeling distracted. You simply can’t be thinking about that late patient or angry email when you’re jumping and lunging at full speed.

All the physicians in our program liked the Tabatas; many were even better than me. (Turns out we have pediatricians and radiologists who do things like run the Boston marathon and win Spartan races).

And if you start doing Tabatas, feel free to email me if you need a recommendation for a standing desk – you might not be able to sit as much afterward.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

I’m in really good shape. Well, more like really not bad shape. I eat healthy food (see my previous column on diet) and work out nearly every day. I have done so for years. I’ve learned that working out doesn’t make much difference with my weight, but it makes a huge difference with my mood, even more so than meditating. That’s why I’ll never give it up.

My approach is to vary my routine, typically by month. I’ve done “BUD/S qualification” months where I do only push-ups, sit-ups, pull-ups, and runs to meet the minimum requirements for the Navy Seal Training. (It’s not as hard as you might think, although I’m pretty lenient on form.)

When I have an hour to exercise and I’m deep into a podcast, then I’ll just keep going. If I’m trying to work out a piece I’m writing, like this one, then I’ll go for a run along the harbor here in San Diego. If I have to catch an early flight or drive to LA for the day, then I might have only 15 minutes. In that instance, I do high-intensity sprints, also known as high-intensity interval training (HIIT). Although it’s hard to break a good sweat, these workouts are both challenging and rewarding.

Recently, I participated in a wonderful physician wellness program at Kaiser Permanente, San Diego, where, over several weeks, we learned about nutrition, practiced meditation, and did Tabatas. What’s a Tabata you ask? It’s a kick in the butt.

. Yup, it’s a 4-minute workout that consists of 20 seconds of all-out, maximum effort, followed by 10 seconds of rest. The specific move you do for Tabatas is up to you, but it’s recommended that it be the same move for all 4 minutes. I like burpees which work your entire body – you jump, you drop into a push-up position, you pull your feet back in, and jump again. (Check out a video on YouTube.)

When we started the class, I thought Tabatas would be too easy for a gym rat like me. Plus, there were pediatricians, and even radiologists there, so how hard could they be? Let’s just say I couldn’t sit for 2 days after my first session: That’s how hard.

Tabatas are also a quick way to torch calories. A study published in the Journal of Sports Science and Medicine in 2013 found subjects who performed a 20-minute Tabata session experienced improved cardiorespiratory endurance and increased calorie burn (J Sports Sci Med. 2013 Sep;12[3]: 612-3).

Sometimes on a Monday, which is typically my difficult day, I’ll break out a few burpees in my office between patients. The energy jolt is real, and unlike caffeine, doesn’t leave me shaky. Because Tabatas require physical and mental focus, they’re an effective way to clear your mind after a grueling patient visit or if you’re feeling distracted. You simply can’t be thinking about that late patient or angry email when you’re jumping and lunging at full speed.

All the physicians in our program liked the Tabatas; many were even better than me. (Turns out we have pediatricians and radiologists who do things like run the Boston marathon and win Spartan races).

And if you start doing Tabatas, feel free to email me if you need a recommendation for a standing desk – you might not be able to sit as much afterward.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

I’m in really good shape. Well, more like really not bad shape. I eat healthy food (see my previous column on diet) and work out nearly every day. I have done so for years. I’ve learned that working out doesn’t make much difference with my weight, but it makes a huge difference with my mood, even more so than meditating. That’s why I’ll never give it up.

My approach is to vary my routine, typically by month. I’ve done “BUD/S qualification” months where I do only push-ups, sit-ups, pull-ups, and runs to meet the minimum requirements for the Navy Seal Training. (It’s not as hard as you might think, although I’m pretty lenient on form.)

When I have an hour to exercise and I’m deep into a podcast, then I’ll just keep going. If I’m trying to work out a piece I’m writing, like this one, then I’ll go for a run along the harbor here in San Diego. If I have to catch an early flight or drive to LA for the day, then I might have only 15 minutes. In that instance, I do high-intensity sprints, also known as high-intensity interval training (HIIT). Although it’s hard to break a good sweat, these workouts are both challenging and rewarding.

Recently, I participated in a wonderful physician wellness program at Kaiser Permanente, San Diego, where, over several weeks, we learned about nutrition, practiced meditation, and did Tabatas. What’s a Tabata you ask? It’s a kick in the butt.

. Yup, it’s a 4-minute workout that consists of 20 seconds of all-out, maximum effort, followed by 10 seconds of rest. The specific move you do for Tabatas is up to you, but it’s recommended that it be the same move for all 4 minutes. I like burpees which work your entire body – you jump, you drop into a push-up position, you pull your feet back in, and jump again. (Check out a video on YouTube.)

When we started the class, I thought Tabatas would be too easy for a gym rat like me. Plus, there were pediatricians, and even radiologists there, so how hard could they be? Let’s just say I couldn’t sit for 2 days after my first session: That’s how hard.

Tabatas are also a quick way to torch calories. A study published in the Journal of Sports Science and Medicine in 2013 found subjects who performed a 20-minute Tabata session experienced improved cardiorespiratory endurance and increased calorie burn (J Sports Sci Med. 2013 Sep;12[3]: 612-3).

Sometimes on a Monday, which is typically my difficult day, I’ll break out a few burpees in my office between patients. The energy jolt is real, and unlike caffeine, doesn’t leave me shaky. Because Tabatas require physical and mental focus, they’re an effective way to clear your mind after a grueling patient visit or if you’re feeling distracted. You simply can’t be thinking about that late patient or angry email when you’re jumping and lunging at full speed.

All the physicians in our program liked the Tabatas; many were even better than me. (Turns out we have pediatricians and radiologists who do things like run the Boston marathon and win Spartan races).

And if you start doing Tabatas, feel free to email me if you need a recommendation for a standing desk – you might not be able to sit as much afterward.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

What Alaska can teach us about burnout

Some people have nightmares of giant rats attacking from their basements, others encounter monsters from a Stephen King novel. My nightmares are of clinic where time is the beast pursuing me. In my nightmares, I’m running late and can’t get to my next patient, or I’m trapped somehow and unable to get to clinic at all.

Time demands that I provide patients access quickly, start clinic on time, double my speed to make up for add-ins, or worse, late patients. Time is a constant, relentless monster, one that has apparently infiltrated my subconscious. Yet, time is relative.

Over Memorial Day weekend, my wife and I flew from San Diego to Alaska. Somewhere between those places time transforms – early summer in San Diego becomes early spring in Alaska.

When we landed, daffodils were in bloom, buds on the alders were just arriving, and the sun struggled to warm the air to 50 degrees. The daytime defied gravity: it was daylight by 4 a.m. and still so after 11 p.m. We were the first visitors this season in our little cabin near Seward.

“Your hot water might take a bit to get hot,” our host, Jim, informed us. He wore a thick flannel shirt and Carhartt workman trousers. He leaned against the cabin’s door frame with one hand at the top and the other hanging from the weight of a DeWalt drill at his side. “I made these cabins myself,” he informed. I was anxious to move on, to unpack and start exploring, but every time I tried to break away from his conversation, he extended it. He shared how a cow and calf (that’s moose talk) had come through earlier that morning. Then he told us about working in the timber industry, starting by “pulling green chain” and working his way up to being the keeper of the saws. While he talked, I watched a raven drop down from the tall Sitka spruce to a branch just across from where we parked our car. Just behind Jim, the raven was not only watching, but also listening in on our conversation. Jim pointed, “That bit of snow over there was all that was left from the 12-foot-high snow earlier this year. It was an easy winter.” He then advised we should start our trip with a visit to Exit Glacier. It was reachable by road and an easy hike.

Staying upright on the steep trail to the glacier’s Harding Icefield concentrates the mind. Looking down and across the glacial outwash, I imagined how the ice once thousands of feet above my head carved a valley from rock. Ice compacted so completely and so deep that only blue light escapes. Indeed, a glacier is just a pile of unmelted snow, thousands of years in the making. The Kenai fjords, deep enough that humpback whales swim there, were carved from granite – at glacial speed. Some of the rocks there contain fossils all the way from the tropics. They were transported by the Pacific tectonic plate that has rotated counterclockwise from the equator to Alaska over millions of years – at tectonic speed. Life here has a way of sharpening your focus, allowing you to see perspective as exists in nature. Alaska is so old that an ob.gyn. could have seen his or her first patient here – a mother with a stillborn child – at the Upward Sun River, 11,500 years ago, where in 2013, the fossil remains of a late-term fetus dating back to that time was discovered. It is indeed relative.

After a long hike, a crispy, hot halibut sandwich, we made it back to our cabin. There was no WiFi or reliable cell service, no TV, no Netflix. We read in bed by daylight. I slept soundly, despite the bright light. No nightmares. No monsters.

The next morning, as I sipped my steaming coffee on our porch, the raven didn’t waste much time to stop by. He paused before coming nearly eye to eye on the roof of the firewood shed in front of me. He looked me up and down and cackled. Not a cawh, not warning me of my intrusion, but rather a vocalization. He just wanted to strike up a conversation with the first guest of the season. He had nothing but time.

On our last night, I lit a fire with wood Jim had cut for us (with help from lots of lighter fluid). Jim ambled over to say goodbye. When I mentioned we had a 2½ hour drive back to Anchorage, he said 3 hours wasn’t a long time for Alaskans. He’d made that drive many times when his kids were little just to take them to McDonald’s. I asked if he ever got burned out, living here. He gave a long pause, turning his chin up, letting the question sink in before constructing an answer. “Burned out? Huh. I don’t know. I guess like when I was pulling green chain in the saw mill. I was pretty tired by the end of the day. But that’s how we sleep so good in Alaska.”

He didn’t get it. In the lower 48, we rush, scramble, and hurry trying to outrun time. At the end, we’re burned out. In Alaska, they don’t know what burned out means. They do understand that time can’t be controlled or beaten. Rather, it is observed and appreciated. I hoped to bring a little of that perspective to clinic on Monday morning.

My recommendation to you if want to sleep better, with fewer nightmares, if you want to reduce your risk for burn out, then go to Alaska (or Montana, or Wyoming, or Idaho, or your backyard). .

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

Some people have nightmares of giant rats attacking from their basements, others encounter monsters from a Stephen King novel. My nightmares are of clinic where time is the beast pursuing me. In my nightmares, I’m running late and can’t get to my next patient, or I’m trapped somehow and unable to get to clinic at all.

Time demands that I provide patients access quickly, start clinic on time, double my speed to make up for add-ins, or worse, late patients. Time is a constant, relentless monster, one that has apparently infiltrated my subconscious. Yet, time is relative.

Over Memorial Day weekend, my wife and I flew from San Diego to Alaska. Somewhere between those places time transforms – early summer in San Diego becomes early spring in Alaska.

When we landed, daffodils were in bloom, buds on the alders were just arriving, and the sun struggled to warm the air to 50 degrees. The daytime defied gravity: it was daylight by 4 a.m. and still so after 11 p.m. We were the first visitors this season in our little cabin near Seward.

“Your hot water might take a bit to get hot,” our host, Jim, informed us. He wore a thick flannel shirt and Carhartt workman trousers. He leaned against the cabin’s door frame with one hand at the top and the other hanging from the weight of a DeWalt drill at his side. “I made these cabins myself,” he informed. I was anxious to move on, to unpack and start exploring, but every time I tried to break away from his conversation, he extended it. He shared how a cow and calf (that’s moose talk) had come through earlier that morning. Then he told us about working in the timber industry, starting by “pulling green chain” and working his way up to being the keeper of the saws. While he talked, I watched a raven drop down from the tall Sitka spruce to a branch just across from where we parked our car. Just behind Jim, the raven was not only watching, but also listening in on our conversation. Jim pointed, “That bit of snow over there was all that was left from the 12-foot-high snow earlier this year. It was an easy winter.” He then advised we should start our trip with a visit to Exit Glacier. It was reachable by road and an easy hike.

Staying upright on the steep trail to the glacier’s Harding Icefield concentrates the mind. Looking down and across the glacial outwash, I imagined how the ice once thousands of feet above my head carved a valley from rock. Ice compacted so completely and so deep that only blue light escapes. Indeed, a glacier is just a pile of unmelted snow, thousands of years in the making. The Kenai fjords, deep enough that humpback whales swim there, were carved from granite – at glacial speed. Some of the rocks there contain fossils all the way from the tropics. They were transported by the Pacific tectonic plate that has rotated counterclockwise from the equator to Alaska over millions of years – at tectonic speed. Life here has a way of sharpening your focus, allowing you to see perspective as exists in nature. Alaska is so old that an ob.gyn. could have seen his or her first patient here – a mother with a stillborn child – at the Upward Sun River, 11,500 years ago, where in 2013, the fossil remains of a late-term fetus dating back to that time was discovered. It is indeed relative.

After a long hike, a crispy, hot halibut sandwich, we made it back to our cabin. There was no WiFi or reliable cell service, no TV, no Netflix. We read in bed by daylight. I slept soundly, despite the bright light. No nightmares. No monsters.

The next morning, as I sipped my steaming coffee on our porch, the raven didn’t waste much time to stop by. He paused before coming nearly eye to eye on the roof of the firewood shed in front of me. He looked me up and down and cackled. Not a cawh, not warning me of my intrusion, but rather a vocalization. He just wanted to strike up a conversation with the first guest of the season. He had nothing but time.

On our last night, I lit a fire with wood Jim had cut for us (with help from lots of lighter fluid). Jim ambled over to say goodbye. When I mentioned we had a 2½ hour drive back to Anchorage, he said 3 hours wasn’t a long time for Alaskans. He’d made that drive many times when his kids were little just to take them to McDonald’s. I asked if he ever got burned out, living here. He gave a long pause, turning his chin up, letting the question sink in before constructing an answer. “Burned out? Huh. I don’t know. I guess like when I was pulling green chain in the saw mill. I was pretty tired by the end of the day. But that’s how we sleep so good in Alaska.”

He didn’t get it. In the lower 48, we rush, scramble, and hurry trying to outrun time. At the end, we’re burned out. In Alaska, they don’t know what burned out means. They do understand that time can’t be controlled or beaten. Rather, it is observed and appreciated. I hoped to bring a little of that perspective to clinic on Monday morning.

My recommendation to you if want to sleep better, with fewer nightmares, if you want to reduce your risk for burn out, then go to Alaska (or Montana, or Wyoming, or Idaho, or your backyard). .

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

Some people have nightmares of giant rats attacking from their basements, others encounter monsters from a Stephen King novel. My nightmares are of clinic where time is the beast pursuing me. In my nightmares, I’m running late and can’t get to my next patient, or I’m trapped somehow and unable to get to clinic at all.

Time demands that I provide patients access quickly, start clinic on time, double my speed to make up for add-ins, or worse, late patients. Time is a constant, relentless monster, one that has apparently infiltrated my subconscious. Yet, time is relative.

Over Memorial Day weekend, my wife and I flew from San Diego to Alaska. Somewhere between those places time transforms – early summer in San Diego becomes early spring in Alaska.

When we landed, daffodils were in bloom, buds on the alders were just arriving, and the sun struggled to warm the air to 50 degrees. The daytime defied gravity: it was daylight by 4 a.m. and still so after 11 p.m. We were the first visitors this season in our little cabin near Seward.

“Your hot water might take a bit to get hot,” our host, Jim, informed us. He wore a thick flannel shirt and Carhartt workman trousers. He leaned against the cabin’s door frame with one hand at the top and the other hanging from the weight of a DeWalt drill at his side. “I made these cabins myself,” he informed. I was anxious to move on, to unpack and start exploring, but every time I tried to break away from his conversation, he extended it. He shared how a cow and calf (that’s moose talk) had come through earlier that morning. Then he told us about working in the timber industry, starting by “pulling green chain” and working his way up to being the keeper of the saws. While he talked, I watched a raven drop down from the tall Sitka spruce to a branch just across from where we parked our car. Just behind Jim, the raven was not only watching, but also listening in on our conversation. Jim pointed, “That bit of snow over there was all that was left from the 12-foot-high snow earlier this year. It was an easy winter.” He then advised we should start our trip with a visit to Exit Glacier. It was reachable by road and an easy hike.

Staying upright on the steep trail to the glacier’s Harding Icefield concentrates the mind. Looking down and across the glacial outwash, I imagined how the ice once thousands of feet above my head carved a valley from rock. Ice compacted so completely and so deep that only blue light escapes. Indeed, a glacier is just a pile of unmelted snow, thousands of years in the making. The Kenai fjords, deep enough that humpback whales swim there, were carved from granite – at glacial speed. Some of the rocks there contain fossils all the way from the tropics. They were transported by the Pacific tectonic plate that has rotated counterclockwise from the equator to Alaska over millions of years – at tectonic speed. Life here has a way of sharpening your focus, allowing you to see perspective as exists in nature. Alaska is so old that an ob.gyn. could have seen his or her first patient here – a mother with a stillborn child – at the Upward Sun River, 11,500 years ago, where in 2013, the fossil remains of a late-term fetus dating back to that time was discovered. It is indeed relative.

After a long hike, a crispy, hot halibut sandwich, we made it back to our cabin. There was no WiFi or reliable cell service, no TV, no Netflix. We read in bed by daylight. I slept soundly, despite the bright light. No nightmares. No monsters.

The next morning, as I sipped my steaming coffee on our porch, the raven didn’t waste much time to stop by. He paused before coming nearly eye to eye on the roof of the firewood shed in front of me. He looked me up and down and cackled. Not a cawh, not warning me of my intrusion, but rather a vocalization. He just wanted to strike up a conversation with the first guest of the season. He had nothing but time.

On our last night, I lit a fire with wood Jim had cut for us (with help from lots of lighter fluid). Jim ambled over to say goodbye. When I mentioned we had a 2½ hour drive back to Anchorage, he said 3 hours wasn’t a long time for Alaskans. He’d made that drive many times when his kids were little just to take them to McDonald’s. I asked if he ever got burned out, living here. He gave a long pause, turning his chin up, letting the question sink in before constructing an answer. “Burned out? Huh. I don’t know. I guess like when I was pulling green chain in the saw mill. I was pretty tired by the end of the day. But that’s how we sleep so good in Alaska.”

He didn’t get it. In the lower 48, we rush, scramble, and hurry trying to outrun time. At the end, we’re burned out. In Alaska, they don’t know what burned out means. They do understand that time can’t be controlled or beaten. Rather, it is observed and appreciated. I hoped to bring a little of that perspective to clinic on Monday morning.

My recommendation to you if want to sleep better, with fewer nightmares, if you want to reduce your risk for burn out, then go to Alaska (or Montana, or Wyoming, or Idaho, or your backyard). .

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

Diet

I’m about to embark on a controversial topic. Perhaps it’s safer to avoid, but I can’t put it off any longer. We need to talk about diet.

Discussing diet, like politics, religion, or salary, is best done just with oneself. Yet, I’m compelled to share what I’ve learned. First, I’m agnostic. I don’t believe you need to be vegan or paleo to be saved. I eat plant-based foods. I also eat things that eat plants. I’m sure you’d find a fine film of gluten in my kitchen. What I’ve learned is that for me, it doesn’t matter.

Specifically, I have little or nothing to eat from when I wake until dinner. As a busy dermatologist, that may seem draconian, but in fact it is easier than you might think. Patients are a constant all day, while hunger is fleeting. Got a craving at 10:15 a.m.? Easy. Walk in to see the next patient. Then repeat. Most days, this continues until 6:30 p.m. or so, when it’s time to head home. It’s not that hard, particularly when you don’t have anything in your office to eat except Dentyne Ice gum and green tea.

Now, this doesn’t always work. Why? Meetings. How do I manage fasting on those days? I don’t. If I know I have a lunch meeting scheduled, then I eat a healthy breakfast before I leave home, such as a protein smoothie or a bowl of hot oats with a dollop of Greek yogurt, sunflower seeds, walnuts, and berries. By eating a wholesome, well-balanced meal of fiber, carbs, lean protein, and good fats, I’m not starving before the meeting and am less likely to overeat. (That’s because I have also learned I’m not one of those enviable people who can simply say “no” to a crispy fish taco and guacamole if I’m hungry. I’m gonna eat it.) So, I avoid fasting and the inevitable frustration of breaking a fast on those days.

On days when I fast, I monitor how I feel. Fortunately, I have rarely felt hypoglycemic; except for that one Tuesday a couple of months ago. I had completed a long, hard early morning workout, and by mid-morning my hands were shaking and I felt nauseous. I quickly downed two RX bars and felt fine within minutes. Better for me, better for my patients.

Right now, intermittent fasting is working for me. Here’s my weekly plan:

I don’t fast on Fridays or weekends or when I travel. I eat out rarely. On weekends, my wife and I shop at the local farmers’ and fish markets to prepare ourselves for a week of healthy eating. And on Sundays, we continue our treasured family tradition of Sunday supper, which is basted with nostalgia and drizzled liberally with comfort. Often it requires long preparation, which is part of the appeal, and short attention is paid to its nutritional value. That’s not the point of Sunday dinner. A delicious dunk of fresh Italian bread in grassy-green olive oil or fresh pasta doused with homemade tomato basil sauce is the best possible meal I can have to prepare for a long, hard week ahead.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

I’m about to embark on a controversial topic. Perhaps it’s safer to avoid, but I can’t put it off any longer. We need to talk about diet.

Discussing diet, like politics, religion, or salary, is best done just with oneself. Yet, I’m compelled to share what I’ve learned. First, I’m agnostic. I don’t believe you need to be vegan or paleo to be saved. I eat plant-based foods. I also eat things that eat plants. I’m sure you’d find a fine film of gluten in my kitchen. What I’ve learned is that for me, it doesn’t matter.

Specifically, I have little or nothing to eat from when I wake until dinner. As a busy dermatologist, that may seem draconian, but in fact it is easier than you might think. Patients are a constant all day, while hunger is fleeting. Got a craving at 10:15 a.m.? Easy. Walk in to see the next patient. Then repeat. Most days, this continues until 6:30 p.m. or so, when it’s time to head home. It’s not that hard, particularly when you don’t have anything in your office to eat except Dentyne Ice gum and green tea.

Now, this doesn’t always work. Why? Meetings. How do I manage fasting on those days? I don’t. If I know I have a lunch meeting scheduled, then I eat a healthy breakfast before I leave home, such as a protein smoothie or a bowl of hot oats with a dollop of Greek yogurt, sunflower seeds, walnuts, and berries. By eating a wholesome, well-balanced meal of fiber, carbs, lean protein, and good fats, I’m not starving before the meeting and am less likely to overeat. (That’s because I have also learned I’m not one of those enviable people who can simply say “no” to a crispy fish taco and guacamole if I’m hungry. I’m gonna eat it.) So, I avoid fasting and the inevitable frustration of breaking a fast on those days.

On days when I fast, I monitor how I feel. Fortunately, I have rarely felt hypoglycemic; except for that one Tuesday a couple of months ago. I had completed a long, hard early morning workout, and by mid-morning my hands were shaking and I felt nauseous. I quickly downed two RX bars and felt fine within minutes. Better for me, better for my patients.

Right now, intermittent fasting is working for me. Here’s my weekly plan:

I don’t fast on Fridays or weekends or when I travel. I eat out rarely. On weekends, my wife and I shop at the local farmers’ and fish markets to prepare ourselves for a week of healthy eating. And on Sundays, we continue our treasured family tradition of Sunday supper, which is basted with nostalgia and drizzled liberally with comfort. Often it requires long preparation, which is part of the appeal, and short attention is paid to its nutritional value. That’s not the point of Sunday dinner. A delicious dunk of fresh Italian bread in grassy-green olive oil or fresh pasta doused with homemade tomato basil sauce is the best possible meal I can have to prepare for a long, hard week ahead.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

I’m about to embark on a controversial topic. Perhaps it’s safer to avoid, but I can’t put it off any longer. We need to talk about diet.

Discussing diet, like politics, religion, or salary, is best done just with oneself. Yet, I’m compelled to share what I’ve learned. First, I’m agnostic. I don’t believe you need to be vegan or paleo to be saved. I eat plant-based foods. I also eat things that eat plants. I’m sure you’d find a fine film of gluten in my kitchen. What I’ve learned is that for me, it doesn’t matter.

Specifically, I have little or nothing to eat from when I wake until dinner. As a busy dermatologist, that may seem draconian, but in fact it is easier than you might think. Patients are a constant all day, while hunger is fleeting. Got a craving at 10:15 a.m.? Easy. Walk in to see the next patient. Then repeat. Most days, this continues until 6:30 p.m. or so, when it’s time to head home. It’s not that hard, particularly when you don’t have anything in your office to eat except Dentyne Ice gum and green tea.

Now, this doesn’t always work. Why? Meetings. How do I manage fasting on those days? I don’t. If I know I have a lunch meeting scheduled, then I eat a healthy breakfast before I leave home, such as a protein smoothie or a bowl of hot oats with a dollop of Greek yogurt, sunflower seeds, walnuts, and berries. By eating a wholesome, well-balanced meal of fiber, carbs, lean protein, and good fats, I’m not starving before the meeting and am less likely to overeat. (That’s because I have also learned I’m not one of those enviable people who can simply say “no” to a crispy fish taco and guacamole if I’m hungry. I’m gonna eat it.) So, I avoid fasting and the inevitable frustration of breaking a fast on those days.

On days when I fast, I monitor how I feel. Fortunately, I have rarely felt hypoglycemic; except for that one Tuesday a couple of months ago. I had completed a long, hard early morning workout, and by mid-morning my hands were shaking and I felt nauseous. I quickly downed two RX bars and felt fine within minutes. Better for me, better for my patients.

Right now, intermittent fasting is working for me. Here’s my weekly plan:

I don’t fast on Fridays or weekends or when I travel. I eat out rarely. On weekends, my wife and I shop at the local farmers’ and fish markets to prepare ourselves for a week of healthy eating. And on Sundays, we continue our treasured family tradition of Sunday supper, which is basted with nostalgia and drizzled liberally with comfort. Often it requires long preparation, which is part of the appeal, and short attention is paid to its nutritional value. That’s not the point of Sunday dinner. A delicious dunk of fresh Italian bread in grassy-green olive oil or fresh pasta doused with homemade tomato basil sauce is the best possible meal I can have to prepare for a long, hard week ahead.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

Grind it out

“And five more, four more, three more, two more, one more, and done!” Just when you thought you could not stand the searing pain any longer, it ends. Your spin instructor is not only helping you be fit, she is also teaching you an important lesson for life: Sometimes you just need to grind it out.

. College basketball teams need to simply grind it out to advance in the NCAA championship tournament. How might Tiger Woods recover from a disastrous few holes at the Masters? “He’ll just have to grind it out on the back nine.” How will you finally finish your PhD thesis? You’ll have to grind it out this month. It’s how I’m writing this column, how I got my taxes in on time, and, sometimes, how I get through clinic.

The phrase is used to describe something which needs to be done that is tedious, laborious, or joyless. Although the outcome of grinding it out is always pleasant, the task is often considered arduous.

In my dermatology practice, patient demand came in like a lion this March, and to meet our awesome access goals, we needed to add clinics on Saturdays, early mornings, and even a few nights. We met our goal, with supply to spare, and felt proud of our accomplishments. Physician wellness gurus (this author not included) say that, to avoid burnout from such excess work, you must find meaning in your work. Be grateful to help that 24-year-old with acne at 8:15 p.m. Think about how lucky you are to serve that lawyer with hand dermatitis at 8:45 p.m. Celebrate the mom’s cancer-free skin screening at 9:00 p.m. By finding meaning in our work, we’re told, we can achieve clinic nirvana. Except it doesn’t always work, and sometimes it serves us badly.

For the long days that ended in night clinic last month, I found myself counting down those last few patients – “four more, three more, two more, and last one.” I love my work and care about my patients, but sometimes I just have to grind it out. I’m proud of what I’ve accomplished.

Now it’s on to spin class.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@MDedge.com.

“And five more, four more, three more, two more, one more, and done!” Just when you thought you could not stand the searing pain any longer, it ends. Your spin instructor is not only helping you be fit, she is also teaching you an important lesson for life: Sometimes you just need to grind it out.

. College basketball teams need to simply grind it out to advance in the NCAA championship tournament. How might Tiger Woods recover from a disastrous few holes at the Masters? “He’ll just have to grind it out on the back nine.” How will you finally finish your PhD thesis? You’ll have to grind it out this month. It’s how I’m writing this column, how I got my taxes in on time, and, sometimes, how I get through clinic.

The phrase is used to describe something which needs to be done that is tedious, laborious, or joyless. Although the outcome of grinding it out is always pleasant, the task is often considered arduous.

In my dermatology practice, patient demand came in like a lion this March, and to meet our awesome access goals, we needed to add clinics on Saturdays, early mornings, and even a few nights. We met our goal, with supply to spare, and felt proud of our accomplishments. Physician wellness gurus (this author not included) say that, to avoid burnout from such excess work, you must find meaning in your work. Be grateful to help that 24-year-old with acne at 8:15 p.m. Think about how lucky you are to serve that lawyer with hand dermatitis at 8:45 p.m. Celebrate the mom’s cancer-free skin screening at 9:00 p.m. By finding meaning in our work, we’re told, we can achieve clinic nirvana. Except it doesn’t always work, and sometimes it serves us badly.

For the long days that ended in night clinic last month, I found myself counting down those last few patients – “four more, three more, two more, and last one.” I love my work and care about my patients, but sometimes I just have to grind it out. I’m proud of what I’ve accomplished.

Now it’s on to spin class.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@MDedge.com.

“And five more, four more, three more, two more, one more, and done!” Just when you thought you could not stand the searing pain any longer, it ends. Your spin instructor is not only helping you be fit, she is also teaching you an important lesson for life: Sometimes you just need to grind it out.

. College basketball teams need to simply grind it out to advance in the NCAA championship tournament. How might Tiger Woods recover from a disastrous few holes at the Masters? “He’ll just have to grind it out on the back nine.” How will you finally finish your PhD thesis? You’ll have to grind it out this month. It’s how I’m writing this column, how I got my taxes in on time, and, sometimes, how I get through clinic.

The phrase is used to describe something which needs to be done that is tedious, laborious, or joyless. Although the outcome of grinding it out is always pleasant, the task is often considered arduous.

In my dermatology practice, patient demand came in like a lion this March, and to meet our awesome access goals, we needed to add clinics on Saturdays, early mornings, and even a few nights. We met our goal, with supply to spare, and felt proud of our accomplishments. Physician wellness gurus (this author not included) say that, to avoid burnout from such excess work, you must find meaning in your work. Be grateful to help that 24-year-old with acne at 8:15 p.m. Think about how lucky you are to serve that lawyer with hand dermatitis at 8:45 p.m. Celebrate the mom’s cancer-free skin screening at 9:00 p.m. By finding meaning in our work, we’re told, we can achieve clinic nirvana. Except it doesn’t always work, and sometimes it serves us badly.

For the long days that ended in night clinic last month, I found myself counting down those last few patients – “four more, three more, two more, and last one.” I love my work and care about my patients, but sometimes I just have to grind it out. I’m proud of what I’ve accomplished.

Now it’s on to spin class.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@MDedge.com.

Podcasts

you need no effort to enjoy them. Indeed, you can be actively engaged elsewhere: running, cycling, commuting, or simply loafing. The detail and richness of the sound also creates an intimate connection with the host in a way other mediums cannot. It feels like they are talking only to you.

Yet, there is a problem with podcasts: There are too many of them. If I listened continuously to the episodes in my queue it would take 6 months. I suppose I could see patients and listen at the same time. (Yes, I have a problem.) I also own far more books than I’ll ever read. Aspirational, I call it.

If, like me, you’re unable to dedicate your life to consuming podcasts, you might appreciate a few recommendations. Here’s a charcuterie board of tasty bits, carefully curated to avoid political allergies and Dunning-Kruger references.

1. Physicians Practice. It’s one of the oldest podcasts running and addresses a wide range of issues affecting health care professionals and the industry at large. Episodes are short (typically under 10 minutes) and address a range of issues relevant to both young and seasoned physicians With scores of podcasts from which to choose, I suggest just selecting one and jumping in. With episode titles such as “The Patient Empathy Problem Physicians Must Face” and “EHRs Not Designed with Real People in Mind, Expert Opines,” it’s easy to do.

2. UpToDate. If you’re looking for straight clinical talk buttressed with scientific evidence, then download UpToDate. Episodes typically feature interviews with one or two respected physician leaders who share their clinical findings. You can select episode topics based upon clinical specialty or simply start listening. Here is a sampling of topics: sentinel lymph node metastasis in melanoma; dexamethasone and acute pharyngitis pain in adults; management of anticoagulation for patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. UpToDate states that it is entirely funded by user subscriptions and does not accept advertising or funding unrelated to subscriptions.

3. Bedside Rounds. The tagline for the podcast Bedside Rounds is “Because medicine is awesome.” This is not meant to be ironic. Creator and host, Adam Rodman, MD, a global health hospitalist who divides his time between Boston (at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center) and Botswana, is that eager kid in the classroom who sits in the front row just because he’s so excited to be there. Unlike UpToDate, which focuses on current advances in clinical medicine, Bedside Rounds explores both the science and art of medicine through captivating stories heavily rooted in the history of medicine. Instead of brushing the dust off of your old medical books, tune in to Bedside Rounds to hear stories such as “Bone Portraits,” which explores the history of radiation, and “Curse of the Ninth,” which explores whether or not composer Gustav Mahler, worked his heart murmur into his famous Ninth Symphony.

4. The Adventures of Memento Mori. Creator and host, D.S. Moss, has created a podcast about death, or, to be more upbeat, the quest for the meaning of life. A screenwriter/producer, Mr. Moss deep dives into all things death. But it’s not as depressing as it sounds. “Memento mori,” he explains, is Latin for being mindful that you will die. As a result, Mr. Moss has created his podcast with the goal of encouraging listeners to live a more engaged, mindful, and meaningful life. We can apply many of these lessons to our own professional and personal lives and perhaps learn some ways to help our patients cope with terminal illness and mortality. Topics range from the emotional (“Thoughts in Passing,” which features several hospice patients) to the technological (“Digital Afterlife,” which explores what our digital legacies say about us), to the scientific (“The Science of Immortality,” which explores venture capital’s movement in the science of living forever).

5. Invisibilia. Invisibilia – Latin for invisible things – is an exploration of the “unseeable forces” that shape human behavior – our beliefs, thoughts, and assumptions. Hosts Alix Spiegel and Hanna Rosin, both of National Public Radio, seamlessly weave storytelling, interviewing, and scientific data to tackle a wide range of topics such as prejudice and implicit bias in “The Culture Inside” to people’s desire for radical change in “Bubble Hopping.” Part behavioral economics, part neuroscience, part sociology, part pop culture, fully fascinating.

6. Jocko Podcast. Jocko Willink, a retired Navy SEAL and motivational author and speaker, along with Echo Charles, conduct compelling interviews with leaders from various fields including the military, sports, medicine, and the arts. Mr. Willink’s style of motivation is refreshingly honest and direct. I have taken tips from his podcasts that have helped me become a more efficient and energetic physician and leader. Two fundamental themes that run through his podcast are the value of treating people well and of living your life with discipline. It gets you a long way as a Navy SEAL, as well as a doctor. One of my personal favorites is Episode 69: “The Real Top Gun. Battlefield, Work, and Life are Identical” with Elite Marine Fighter Pilot, David Berke. If that doesn’t pique your interest, no worries; there are over 100 episodes from which to choose.

There are many, many more podcasts I’d like to recommend, but I’ll show some discipline (thanks, Jocko) and save them for next time.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

you need no effort to enjoy them. Indeed, you can be actively engaged elsewhere: running, cycling, commuting, or simply loafing. The detail and richness of the sound also creates an intimate connection with the host in a way other mediums cannot. It feels like they are talking only to you.

Yet, there is a problem with podcasts: There are too many of them. If I listened continuously to the episodes in my queue it would take 6 months. I suppose I could see patients and listen at the same time. (Yes, I have a problem.) I also own far more books than I’ll ever read. Aspirational, I call it.

If, like me, you’re unable to dedicate your life to consuming podcasts, you might appreciate a few recommendations. Here’s a charcuterie board of tasty bits, carefully curated to avoid political allergies and Dunning-Kruger references.

1. Physicians Practice. It’s one of the oldest podcasts running and addresses a wide range of issues affecting health care professionals and the industry at large. Episodes are short (typically under 10 minutes) and address a range of issues relevant to both young and seasoned physicians With scores of podcasts from which to choose, I suggest just selecting one and jumping in. With episode titles such as “The Patient Empathy Problem Physicians Must Face” and “EHRs Not Designed with Real People in Mind, Expert Opines,” it’s easy to do.

2. UpToDate. If you’re looking for straight clinical talk buttressed with scientific evidence, then download UpToDate. Episodes typically feature interviews with one or two respected physician leaders who share their clinical findings. You can select episode topics based upon clinical specialty or simply start listening. Here is a sampling of topics: sentinel lymph node metastasis in melanoma; dexamethasone and acute pharyngitis pain in adults; management of anticoagulation for patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. UpToDate states that it is entirely funded by user subscriptions and does not accept advertising or funding unrelated to subscriptions.

3. Bedside Rounds. The tagline for the podcast Bedside Rounds is “Because medicine is awesome.” This is not meant to be ironic. Creator and host, Adam Rodman, MD, a global health hospitalist who divides his time between Boston (at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center) and Botswana, is that eager kid in the classroom who sits in the front row just because he’s so excited to be there. Unlike UpToDate, which focuses on current advances in clinical medicine, Bedside Rounds explores both the science and art of medicine through captivating stories heavily rooted in the history of medicine. Instead of brushing the dust off of your old medical books, tune in to Bedside Rounds to hear stories such as “Bone Portraits,” which explores the history of radiation, and “Curse of the Ninth,” which explores whether or not composer Gustav Mahler, worked his heart murmur into his famous Ninth Symphony.

4. The Adventures of Memento Mori. Creator and host, D.S. Moss, has created a podcast about death, or, to be more upbeat, the quest for the meaning of life. A screenwriter/producer, Mr. Moss deep dives into all things death. But it’s not as depressing as it sounds. “Memento mori,” he explains, is Latin for being mindful that you will die. As a result, Mr. Moss has created his podcast with the goal of encouraging listeners to live a more engaged, mindful, and meaningful life. We can apply many of these lessons to our own professional and personal lives and perhaps learn some ways to help our patients cope with terminal illness and mortality. Topics range from the emotional (“Thoughts in Passing,” which features several hospice patients) to the technological (“Digital Afterlife,” which explores what our digital legacies say about us), to the scientific (“The Science of Immortality,” which explores venture capital’s movement in the science of living forever).

5. Invisibilia. Invisibilia – Latin for invisible things – is an exploration of the “unseeable forces” that shape human behavior – our beliefs, thoughts, and assumptions. Hosts Alix Spiegel and Hanna Rosin, both of National Public Radio, seamlessly weave storytelling, interviewing, and scientific data to tackle a wide range of topics such as prejudice and implicit bias in “The Culture Inside” to people’s desire for radical change in “Bubble Hopping.” Part behavioral economics, part neuroscience, part sociology, part pop culture, fully fascinating.

6. Jocko Podcast. Jocko Willink, a retired Navy SEAL and motivational author and speaker, along with Echo Charles, conduct compelling interviews with leaders from various fields including the military, sports, medicine, and the arts. Mr. Willink’s style of motivation is refreshingly honest and direct. I have taken tips from his podcasts that have helped me become a more efficient and energetic physician and leader. Two fundamental themes that run through his podcast are the value of treating people well and of living your life with discipline. It gets you a long way as a Navy SEAL, as well as a doctor. One of my personal favorites is Episode 69: “The Real Top Gun. Battlefield, Work, and Life are Identical” with Elite Marine Fighter Pilot, David Berke. If that doesn’t pique your interest, no worries; there are over 100 episodes from which to choose.

There are many, many more podcasts I’d like to recommend, but I’ll show some discipline (thanks, Jocko) and save them for next time.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

you need no effort to enjoy them. Indeed, you can be actively engaged elsewhere: running, cycling, commuting, or simply loafing. The detail and richness of the sound also creates an intimate connection with the host in a way other mediums cannot. It feels like they are talking only to you.

Yet, there is a problem with podcasts: There are too many of them. If I listened continuously to the episodes in my queue it would take 6 months. I suppose I could see patients and listen at the same time. (Yes, I have a problem.) I also own far more books than I’ll ever read. Aspirational, I call it.

If, like me, you’re unable to dedicate your life to consuming podcasts, you might appreciate a few recommendations. Here’s a charcuterie board of tasty bits, carefully curated to avoid political allergies and Dunning-Kruger references.

1. Physicians Practice. It’s one of the oldest podcasts running and addresses a wide range of issues affecting health care professionals and the industry at large. Episodes are short (typically under 10 minutes) and address a range of issues relevant to both young and seasoned physicians With scores of podcasts from which to choose, I suggest just selecting one and jumping in. With episode titles such as “The Patient Empathy Problem Physicians Must Face” and “EHRs Not Designed with Real People in Mind, Expert Opines,” it’s easy to do.

2. UpToDate. If you’re looking for straight clinical talk buttressed with scientific evidence, then download UpToDate. Episodes typically feature interviews with one or two respected physician leaders who share their clinical findings. You can select episode topics based upon clinical specialty or simply start listening. Here is a sampling of topics: sentinel lymph node metastasis in melanoma; dexamethasone and acute pharyngitis pain in adults; management of anticoagulation for patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. UpToDate states that it is entirely funded by user subscriptions and does not accept advertising or funding unrelated to subscriptions.

3. Bedside Rounds. The tagline for the podcast Bedside Rounds is “Because medicine is awesome.” This is not meant to be ironic. Creator and host, Adam Rodman, MD, a global health hospitalist who divides his time between Boston (at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center) and Botswana, is that eager kid in the classroom who sits in the front row just because he’s so excited to be there. Unlike UpToDate, which focuses on current advances in clinical medicine, Bedside Rounds explores both the science and art of medicine through captivating stories heavily rooted in the history of medicine. Instead of brushing the dust off of your old medical books, tune in to Bedside Rounds to hear stories such as “Bone Portraits,” which explores the history of radiation, and “Curse of the Ninth,” which explores whether or not composer Gustav Mahler, worked his heart murmur into his famous Ninth Symphony.