User login

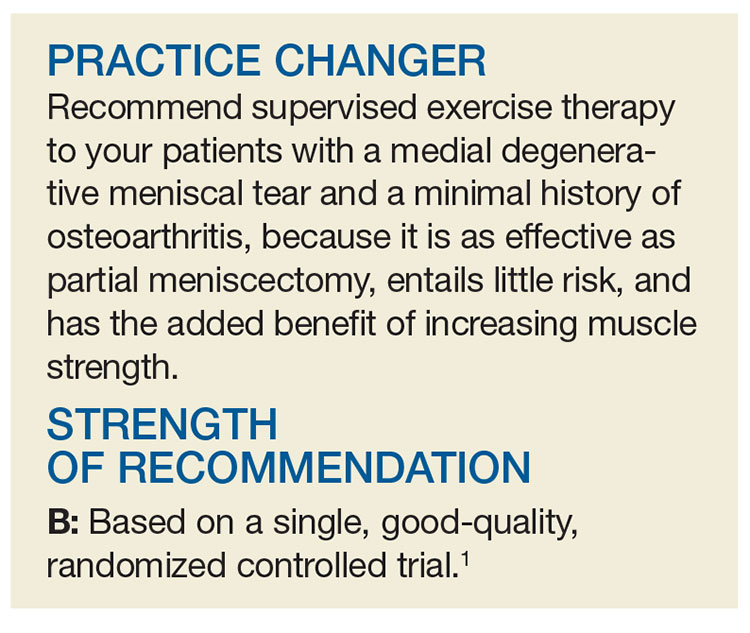

When Can Exercise Supplant Surgery for Degenerative Meniscal Tears?

A 48-year-old man presents to your office for follow-up of right knee pain that has been bothering him for the past 12 months. He denies any trauma or inciting incident for the pain. On physical exam, he does not have crepitus but does have medial joint line tenderness of his right knee. An MRI shows a partial medial meniscal tear. Do you refer him to physical therapy (PT) or to orthopedics for arthroscopy and repair?

The meniscus—cartilage in the knee joint that provides support, stability, and lubrication to the joint during activity—can tear during a traumatic event or as a result of degeneration over time. Traumatic meniscal tears typically occur in those younger than 30 during sports (eg, basketball, soccer), whereas degenerative meniscal tears generally occur in patients ages 40 to 60.2,3 The annual incidence of all meniscal tears is 79 per 100,000.4 While some clinicians can diagnose traumatic meniscal tears based on history and physical examination, degenerative meniscal tears are more challenging and typically warrant an MRI for confirmation.3

Meniscal tears can be treated either conservatively, with supportive care and exercise, or surgically. Unfortunately, there are no national orthopedic guidelines available to help direct care. In one observational study, 95 of 117 patients (81.2%) were generally satisfied with surgical treatment at four-year follow-up; satisfaction was higher among those with a traumatic meniscal tear than in those with a degenerative tear.5

Two systematic reviews of surgery versus nonoperative management or sham therapies found no additional benefit of surgery for meniscal tears in a variety of patients with and without osteoarthritis.6,7 However, both studies were of only moderate quality, because of the number of patients in the nonoperative groups who ultimately underwent surgery. Neither of the studies directly compared surgery to nonoperative management.6,7Another investigation—a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, sham-controlled study conducted in Finland involving 1

Clinical practice recommendations devised from a vast systematic review of the literature recommend that the decision for surgery be based on patient-specific factors, such as symptoms, age, mechanism of tear, extent of damage, and occupational/social/activity needs.9

STUDY SUMMARY

Exercise is as good as surgery

The current superiority RCT compared exercise therapy to arthroscopic partial meniscectomy. Subjects (ages 35 to 60) presented to the orthopedic department of two hospitals in Norway with unilateral knee pain of more than two months’ duration and an MRI-delineated medial meniscal tear. They were included in the study only if they had radiographic evidence of minimal osteoarthritis (Kellgren-Lawrence classification grade ≤ 2). Exclusion criteria included acute trauma, locked knee, ligament injury, and knee surgery in the same knee within the previous two years.

The primary outcomes were change in patient-reported knee function (as determined by overall Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score [KOOS] after two years) and thigh muscle strength at three months (as measured by physiotherapists). The researchers used four of the five KOOS subscales for this analysis: pain, other symptoms (swelling, grinding/noise from the joint, ability to straighten and bend), function in sports/recreation, and knee-related quality of life (QOL). The average score of each subscale was used.

Secondary outcomes included the five individual KOOS subscales (the four previously mentioned, plus activities of daily living [ADLs]), as well as thigh muscle strength and lower-extremity performance test results.

Methods. Testing personnel were blinded to group allocation; participants wore pants or neoprene sleeves to cover surgical scars. A total of 140 patients were randomized to either 12 weeks (24-36 sessions) of exercise therapy alone or a standardized arthroscopic partial meniscectomy; upon discharge, those in the latter group received written and oral encouragement to perform simple exercises at home, two to four times daily, to regain range of motion and reduce swelling.

Results. At two years, the overall mean improvement in KOOS4 score from baseline was similar between the exercise group and the meniscectomy group (25.3 pts vs 24.4 pts, respectively; mean difference [MD], 0.9). Additionally, muscle strength (measured as peak torque flexion and extension and total work flexion and extension) at both three and 12 months showed significant objective improvements favoring exercise therapy.

In the secondary analysis of the KOOS subscale scores, change from baseline was nonsignificant for four of the five (pain, ADL, sports/recreation, and QOL). Only the symptoms subscale had a significant difference favoring exercise therapy (MD, 5.3 pts); this was likely clinically insignificant on a grading scale of 0 to 100.

Of the patients allocated to exercise therapy alone, 19% crossed over and underwent surgery during the two-year study period.

WHAT’S NEW

Head-to-head comparison adds evidence

This is the first trial to directly compare exercise therapy to surgery in patients with meniscal tears. Interestingly, exercise therapy was as effective after a two-year follow-up period and was superior in the short term for thigh muscle strength.1

The results of this study build on those from the aforementioned smaller study conducted in Finland.8 In that study, both groups received instruction for the same graduated exercise plan. The researchers found that exercise was comparable to surgery for meniscal tears in patients with no osteoarthritis.

CAVEATS

What about more severe osteoarthritis?

This trial included patients with no to mild osteoarthritis in addition to their meniscal tear.1 It is unclear if the results would be maintained in those with more advanced disease. Additionally, 19% of patients crossed over from the exercise group to the surgery group, even though muscle strength improved. Therefore, education about the risks of surgery and the potential lack of benefit is important.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Cost and effort of PT

The cost of PT can be a barrier for patients who have adequate insurance coverage for surgery but inadequate coverage for PT. Additionally, exercise therapy requires significant and ongoing time and effort, which may deter those with busy lifestyles. Patients and clinicians may view surgery as an “easier” fix.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2017. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice (2017;66[4]:250-252).

1. Kise NJ, Risberg MA, Stensrud S, et al. Exercise therapy versus arthroscopic partial meniscectomy for degenerative meniscal tear in middle aged patients: randomised controlled trial with two year follow-up. BMJ. 2016;354:i3740.

2. Beals CT, Magnussen RA, Graham WC, et al. The prevalence of meniscal pathology in asymptomatic athletes. Sports Med. 2016;46:1517-1524.

3. Maffulli N, Longo UG, Campi S, et al. Meniscal tears. Open Access J Sports Med. 2010;1:45-54.

4. Peat G, Bergknut C, Frobell R, et al. Population-wide incidence estimates for soft tissue knee injuries presenting to healthcare in southern Sweden: data from the Skåne Healthcare Register. Arthritis Res Ther. 2014;16:R162.

5. Ghislain NA, Wei JN, Li YG. Study of the clinical outcome between traumatic and degenerative (non-traumatic) meniscal tears after arthroscopic surgery: a 4-years follow-up study. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10:RC01-RC04.

6. Khan M, Evaniew N, Bedi A, et al. Arthroscopic surgery for degenerative tears of the meniscus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ. 2014;186:1057-1064.

7. Monk P, Garfjeld Roberts P, Palmer AJ, et al. The urgent need for evidence in arthroscopic meniscal surgery: a systematic review of the evidence for operative management of meniscal tears. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45:965-973.

8. Sihvonen R, Paavola M, Malmivaara A, et al; Finnish Degenerative Meniscal Lesion Study (FIDELITY) Group. Arthroscopic partial meniscectomy versus sham surgery for a degenerative meniscal tear. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:2515-2524.

9. Beaufils P, Hulet C, Dhénain M, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of meniscal lesions and isolated lesions of the anterior cruciate ligament of the knee in adults. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2009;95:437-442.

A 48-year-old man presents to your office for follow-up of right knee pain that has been bothering him for the past 12 months. He denies any trauma or inciting incident for the pain. On physical exam, he does not have crepitus but does have medial joint line tenderness of his right knee. An MRI shows a partial medial meniscal tear. Do you refer him to physical therapy (PT) or to orthopedics for arthroscopy and repair?

The meniscus—cartilage in the knee joint that provides support, stability, and lubrication to the joint during activity—can tear during a traumatic event or as a result of degeneration over time. Traumatic meniscal tears typically occur in those younger than 30 during sports (eg, basketball, soccer), whereas degenerative meniscal tears generally occur in patients ages 40 to 60.2,3 The annual incidence of all meniscal tears is 79 per 100,000.4 While some clinicians can diagnose traumatic meniscal tears based on history and physical examination, degenerative meniscal tears are more challenging and typically warrant an MRI for confirmation.3

Meniscal tears can be treated either conservatively, with supportive care and exercise, or surgically. Unfortunately, there are no national orthopedic guidelines available to help direct care. In one observational study, 95 of 117 patients (81.2%) were generally satisfied with surgical treatment at four-year follow-up; satisfaction was higher among those with a traumatic meniscal tear than in those with a degenerative tear.5

Two systematic reviews of surgery versus nonoperative management or sham therapies found no additional benefit of surgery for meniscal tears in a variety of patients with and without osteoarthritis.6,7 However, both studies were of only moderate quality, because of the number of patients in the nonoperative groups who ultimately underwent surgery. Neither of the studies directly compared surgery to nonoperative management.6,7Another investigation—a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, sham-controlled study conducted in Finland involving 1

Clinical practice recommendations devised from a vast systematic review of the literature recommend that the decision for surgery be based on patient-specific factors, such as symptoms, age, mechanism of tear, extent of damage, and occupational/social/activity needs.9

STUDY SUMMARY

Exercise is as good as surgery

The current superiority RCT compared exercise therapy to arthroscopic partial meniscectomy. Subjects (ages 35 to 60) presented to the orthopedic department of two hospitals in Norway with unilateral knee pain of more than two months’ duration and an MRI-delineated medial meniscal tear. They were included in the study only if they had radiographic evidence of minimal osteoarthritis (Kellgren-Lawrence classification grade ≤ 2). Exclusion criteria included acute trauma, locked knee, ligament injury, and knee surgery in the same knee within the previous two years.

The primary outcomes were change in patient-reported knee function (as determined by overall Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score [KOOS] after two years) and thigh muscle strength at three months (as measured by physiotherapists). The researchers used four of the five KOOS subscales for this analysis: pain, other symptoms (swelling, grinding/noise from the joint, ability to straighten and bend), function in sports/recreation, and knee-related quality of life (QOL). The average score of each subscale was used.

Secondary outcomes included the five individual KOOS subscales (the four previously mentioned, plus activities of daily living [ADLs]), as well as thigh muscle strength and lower-extremity performance test results.

Methods. Testing personnel were blinded to group allocation; participants wore pants or neoprene sleeves to cover surgical scars. A total of 140 patients were randomized to either 12 weeks (24-36 sessions) of exercise therapy alone or a standardized arthroscopic partial meniscectomy; upon discharge, those in the latter group received written and oral encouragement to perform simple exercises at home, two to four times daily, to regain range of motion and reduce swelling.

Results. At two years, the overall mean improvement in KOOS4 score from baseline was similar between the exercise group and the meniscectomy group (25.3 pts vs 24.4 pts, respectively; mean difference [MD], 0.9). Additionally, muscle strength (measured as peak torque flexion and extension and total work flexion and extension) at both three and 12 months showed significant objective improvements favoring exercise therapy.

In the secondary analysis of the KOOS subscale scores, change from baseline was nonsignificant for four of the five (pain, ADL, sports/recreation, and QOL). Only the symptoms subscale had a significant difference favoring exercise therapy (MD, 5.3 pts); this was likely clinically insignificant on a grading scale of 0 to 100.

Of the patients allocated to exercise therapy alone, 19% crossed over and underwent surgery during the two-year study period.

WHAT’S NEW

Head-to-head comparison adds evidence

This is the first trial to directly compare exercise therapy to surgery in patients with meniscal tears. Interestingly, exercise therapy was as effective after a two-year follow-up period and was superior in the short term for thigh muscle strength.1

The results of this study build on those from the aforementioned smaller study conducted in Finland.8 In that study, both groups received instruction for the same graduated exercise plan. The researchers found that exercise was comparable to surgery for meniscal tears in patients with no osteoarthritis.

CAVEATS

What about more severe osteoarthritis?

This trial included patients with no to mild osteoarthritis in addition to their meniscal tear.1 It is unclear if the results would be maintained in those with more advanced disease. Additionally, 19% of patients crossed over from the exercise group to the surgery group, even though muscle strength improved. Therefore, education about the risks of surgery and the potential lack of benefit is important.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Cost and effort of PT

The cost of PT can be a barrier for patients who have adequate insurance coverage for surgery but inadequate coverage for PT. Additionally, exercise therapy requires significant and ongoing time and effort, which may deter those with busy lifestyles. Patients and clinicians may view surgery as an “easier” fix.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2017. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice (2017;66[4]:250-252).

A 48-year-old man presents to your office for follow-up of right knee pain that has been bothering him for the past 12 months. He denies any trauma or inciting incident for the pain. On physical exam, he does not have crepitus but does have medial joint line tenderness of his right knee. An MRI shows a partial medial meniscal tear. Do you refer him to physical therapy (PT) or to orthopedics for arthroscopy and repair?

The meniscus—cartilage in the knee joint that provides support, stability, and lubrication to the joint during activity—can tear during a traumatic event or as a result of degeneration over time. Traumatic meniscal tears typically occur in those younger than 30 during sports (eg, basketball, soccer), whereas degenerative meniscal tears generally occur in patients ages 40 to 60.2,3 The annual incidence of all meniscal tears is 79 per 100,000.4 While some clinicians can diagnose traumatic meniscal tears based on history and physical examination, degenerative meniscal tears are more challenging and typically warrant an MRI for confirmation.3

Meniscal tears can be treated either conservatively, with supportive care and exercise, or surgically. Unfortunately, there are no national orthopedic guidelines available to help direct care. In one observational study, 95 of 117 patients (81.2%) were generally satisfied with surgical treatment at four-year follow-up; satisfaction was higher among those with a traumatic meniscal tear than in those with a degenerative tear.5

Two systematic reviews of surgery versus nonoperative management or sham therapies found no additional benefit of surgery for meniscal tears in a variety of patients with and without osteoarthritis.6,7 However, both studies were of only moderate quality, because of the number of patients in the nonoperative groups who ultimately underwent surgery. Neither of the studies directly compared surgery to nonoperative management.6,7Another investigation—a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, sham-controlled study conducted in Finland involving 1

Clinical practice recommendations devised from a vast systematic review of the literature recommend that the decision for surgery be based on patient-specific factors, such as symptoms, age, mechanism of tear, extent of damage, and occupational/social/activity needs.9

STUDY SUMMARY

Exercise is as good as surgery

The current superiority RCT compared exercise therapy to arthroscopic partial meniscectomy. Subjects (ages 35 to 60) presented to the orthopedic department of two hospitals in Norway with unilateral knee pain of more than two months’ duration and an MRI-delineated medial meniscal tear. They were included in the study only if they had radiographic evidence of minimal osteoarthritis (Kellgren-Lawrence classification grade ≤ 2). Exclusion criteria included acute trauma, locked knee, ligament injury, and knee surgery in the same knee within the previous two years.

The primary outcomes were change in patient-reported knee function (as determined by overall Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score [KOOS] after two years) and thigh muscle strength at three months (as measured by physiotherapists). The researchers used four of the five KOOS subscales for this analysis: pain, other symptoms (swelling, grinding/noise from the joint, ability to straighten and bend), function in sports/recreation, and knee-related quality of life (QOL). The average score of each subscale was used.

Secondary outcomes included the five individual KOOS subscales (the four previously mentioned, plus activities of daily living [ADLs]), as well as thigh muscle strength and lower-extremity performance test results.

Methods. Testing personnel were blinded to group allocation; participants wore pants or neoprene sleeves to cover surgical scars. A total of 140 patients were randomized to either 12 weeks (24-36 sessions) of exercise therapy alone or a standardized arthroscopic partial meniscectomy; upon discharge, those in the latter group received written and oral encouragement to perform simple exercises at home, two to four times daily, to regain range of motion and reduce swelling.

Results. At two years, the overall mean improvement in KOOS4 score from baseline was similar between the exercise group and the meniscectomy group (25.3 pts vs 24.4 pts, respectively; mean difference [MD], 0.9). Additionally, muscle strength (measured as peak torque flexion and extension and total work flexion and extension) at both three and 12 months showed significant objective improvements favoring exercise therapy.

In the secondary analysis of the KOOS subscale scores, change from baseline was nonsignificant for four of the five (pain, ADL, sports/recreation, and QOL). Only the symptoms subscale had a significant difference favoring exercise therapy (MD, 5.3 pts); this was likely clinically insignificant on a grading scale of 0 to 100.

Of the patients allocated to exercise therapy alone, 19% crossed over and underwent surgery during the two-year study period.

WHAT’S NEW

Head-to-head comparison adds evidence

This is the first trial to directly compare exercise therapy to surgery in patients with meniscal tears. Interestingly, exercise therapy was as effective after a two-year follow-up period and was superior in the short term for thigh muscle strength.1

The results of this study build on those from the aforementioned smaller study conducted in Finland.8 In that study, both groups received instruction for the same graduated exercise plan. The researchers found that exercise was comparable to surgery for meniscal tears in patients with no osteoarthritis.

CAVEATS

What about more severe osteoarthritis?

This trial included patients with no to mild osteoarthritis in addition to their meniscal tear.1 It is unclear if the results would be maintained in those with more advanced disease. Additionally, 19% of patients crossed over from the exercise group to the surgery group, even though muscle strength improved. Therefore, education about the risks of surgery and the potential lack of benefit is important.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Cost and effort of PT

The cost of PT can be a barrier for patients who have adequate insurance coverage for surgery but inadequate coverage for PT. Additionally, exercise therapy requires significant and ongoing time and effort, which may deter those with busy lifestyles. Patients and clinicians may view surgery as an “easier” fix.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2017. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice (2017;66[4]:250-252).

1. Kise NJ, Risberg MA, Stensrud S, et al. Exercise therapy versus arthroscopic partial meniscectomy for degenerative meniscal tear in middle aged patients: randomised controlled trial with two year follow-up. BMJ. 2016;354:i3740.

2. Beals CT, Magnussen RA, Graham WC, et al. The prevalence of meniscal pathology in asymptomatic athletes. Sports Med. 2016;46:1517-1524.

3. Maffulli N, Longo UG, Campi S, et al. Meniscal tears. Open Access J Sports Med. 2010;1:45-54.

4. Peat G, Bergknut C, Frobell R, et al. Population-wide incidence estimates for soft tissue knee injuries presenting to healthcare in southern Sweden: data from the Skåne Healthcare Register. Arthritis Res Ther. 2014;16:R162.

5. Ghislain NA, Wei JN, Li YG. Study of the clinical outcome between traumatic and degenerative (non-traumatic) meniscal tears after arthroscopic surgery: a 4-years follow-up study. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10:RC01-RC04.

6. Khan M, Evaniew N, Bedi A, et al. Arthroscopic surgery for degenerative tears of the meniscus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ. 2014;186:1057-1064.

7. Monk P, Garfjeld Roberts P, Palmer AJ, et al. The urgent need for evidence in arthroscopic meniscal surgery: a systematic review of the evidence for operative management of meniscal tears. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45:965-973.

8. Sihvonen R, Paavola M, Malmivaara A, et al; Finnish Degenerative Meniscal Lesion Study (FIDELITY) Group. Arthroscopic partial meniscectomy versus sham surgery for a degenerative meniscal tear. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:2515-2524.

9. Beaufils P, Hulet C, Dhénain M, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of meniscal lesions and isolated lesions of the anterior cruciate ligament of the knee in adults. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2009;95:437-442.

1. Kise NJ, Risberg MA, Stensrud S, et al. Exercise therapy versus arthroscopic partial meniscectomy for degenerative meniscal tear in middle aged patients: randomised controlled trial with two year follow-up. BMJ. 2016;354:i3740.

2. Beals CT, Magnussen RA, Graham WC, et al. The prevalence of meniscal pathology in asymptomatic athletes. Sports Med. 2016;46:1517-1524.

3. Maffulli N, Longo UG, Campi S, et al. Meniscal tears. Open Access J Sports Med. 2010;1:45-54.

4. Peat G, Bergknut C, Frobell R, et al. Population-wide incidence estimates for soft tissue knee injuries presenting to healthcare in southern Sweden: data from the Skåne Healthcare Register. Arthritis Res Ther. 2014;16:R162.

5. Ghislain NA, Wei JN, Li YG. Study of the clinical outcome between traumatic and degenerative (non-traumatic) meniscal tears after arthroscopic surgery: a 4-years follow-up study. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10:RC01-RC04.

6. Khan M, Evaniew N, Bedi A, et al. Arthroscopic surgery for degenerative tears of the meniscus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ. 2014;186:1057-1064.

7. Monk P, Garfjeld Roberts P, Palmer AJ, et al. The urgent need for evidence in arthroscopic meniscal surgery: a systematic review of the evidence for operative management of meniscal tears. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45:965-973.

8. Sihvonen R, Paavola M, Malmivaara A, et al; Finnish Degenerative Meniscal Lesion Study (FIDELITY) Group. Arthroscopic partial meniscectomy versus sham surgery for a degenerative meniscal tear. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:2515-2524.

9. Beaufils P, Hulet C, Dhénain M, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of meniscal lesions and isolated lesions of the anterior cruciate ligament of the knee in adults. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2009;95:437-442.

Consider melatonin for migraine prevention

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 32-year-old woman comes to your office for help with her recurrent migraines, which she’s had since her early 20s. She is otherwise healthy and active. She is frustrated over the frequency of her migraines and the debilitation they cause. She has tried prophylactic medications in the past, but stopped taking them because of the adverse effects. What do you recommend for treatment?

Daily preventive medication can be helpful for chronic migraine sufferers whose headaches have a significant impact on their lives and who have a goal of reducing headache frequency or severity, disability, and/or avoiding acute headache medication escalation.2 An estimated 38% of patients with migraines are appropriate candidates for prophylactic therapy, but only 3% to 13% are taking preventive medications.3

Evidence-based guidelines from the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society state that antiepileptic drugs (divalproex sodium, sodium valproate, topiramate) and many beta-blockers (metoprolol, propranolol, timolol) are effective and should be recommended for migraine prevention (level A recommendation; based on ≥2 class I trials).2 Medications such as antidepressants (amitriptyline, venlafaxine) and other beta-blockers (atenolol, nadolol) are probably effective and can be considered (level B recommendation; based on one class I trial or 2 class II trials).2 However, adverse effects, such as somnolence, are listed as frequent with amitriptyline and occasional to frequent with topiramate.4

Researchers have investigated melatonin before. But a 2010 double-blind, crossover, randomized controlled trial (RCT) of 46 patients with 2 to 7 migraine attacks per month found no significant difference in reduction of headache frequency with extended-release melatonin 2 mg taken one hour before bed compared to placebo over an 8-week period.5

[polldaddy:9724288]

STUDY SUMMARY

Melatonin tops amitriptyline in >50% improvement in headache frequency

This RCT conducted in Brazil compared the effectiveness of melatonin to amitriptyline and placebo for migraine prevention in 196 adults (ages 18-65 years) with chronic migraines.1 Eligible patients had a history of at least 3 migraine attacks or 4 migraine headache days per month. Patients were randomized to take identically-appearing melatonin 3 mg, amitriptyline 25 mg, or placebo nightly. The investigators appear to have concealed allocation adequately, and used double-blinding.

The primary outcome was the number of headache days per month, comparing baseline with the 4 weeks of treatment. Secondary endpoints included reduction in migraine intensity, duration, number of analgesics used, and percentage of patients with more than 50% reduction in migraine headache days.

Compared to placebo, headache days per month were reduced in both the melatonin group (6.2 days vs 4.6 days, respectively; mean difference [MD], -1.6; 95% confidence interval [CI], -2.4 to -0.9) and the amitriptyline group (6.2 days vs 5 days, respectively; MD, -1.1; 95% CI, -1.5 to -0.7) at 12 weeks, based on intention-to-treat analysis. Mean headache intensity (0-10 pain scale) was also lower at 12 weeks in the melatonin group (4.8 vs 3.6; MD, -1.2; 95% CI, -1.6 to -0.8) and in the amitriptyline group (4.8 vs 3.5; MD, -1.3; 95% CI, -1.7 to -0.9), when compared to placebo.

Headache duration (hours/month) at 12 weeks was reduced in both groups (amitriptyline MD, -4.4 hours; 95% CI, -5.1 to -3.9; melatonin MD, -4.8 hours; 95% CI, -5.7 to -3.9), as was the number of analgesics used (amitriptyline MD, -1; 95% CI, -1.5 to -0.5; melatonin MD, -1; 95% CI, -1.4 to -0.6) when compared to placebo. There was no significant difference between the melatonin and amitriptyline groups for these outcomes.

Patients taking melatonin were more likely to have a >50% improvement in headache frequency compared to amitriptyline (54% vs 39%; number needed to treat [NNT]=7; P<.05); melatonin worked much better than placebo (54% vs 20%; NNT=3; P<.01).

Adverse events were reported more often in the amitriptyline group than in the melatonin group (46 vs 16; P<.03) with daytime sleepiness being the most frequent complaint (41% of patients in the amitriptyline group vs 18% of the melatonin group; number needed to harm [NNH]=5). There was no significant difference in adverse events between melatonin and placebo (16 vs 17; P=not significant). Melatonin resulted in weight loss (mean, -0.14 kg), whereas those taking amitriptyline gained weight (+0.97 kg; P<.01).

WHAT’S NEW

An effective migraine prevention alternative with minimal adverse effects

Melatonin is an accessible and affordable option for preventing migraine headaches in chronic sufferers. The 3-mg dosing reduces headache frequency—both in terms of the number of migraine headache days per month and in terms of the percentage of patients with a >50% reduction in headache events—as well as headache intensity, with minimal adverse effects.

CAVEATS

Product consistency, missing study data

This trial used 3-mg dosing, so it is not clear if other doses are also effective. In addition, because melatonin is available over-the-counter, the quality/actual doses may be less well regulated, and thus, there may be a lack of consistency between brands. Unlike clinical practice, neither the amitriptyline nor the melatonin dose was titrated according to patient response or adverse effects. As a result, we are not sure of the actual lowest effective dose, or if greater effect (with continued minimal adverse effects) could be achieved with higher doses.

Lastly, 69% to 75% of patients in the treatment groups completed the 16-week trial, but the authors of the study reported using 3 different analytic techniques to estimate missing data. The primary outcome included 178 of 196 randomized patients (90.8%). For the primary endpoint, the authors treated all missing data as non-headache days. It is unclear how these missing data would affect the outcome, although an analysis like this would tend towards a null effect.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Challenges are negligible

There are really no challenges to implementing this practice changer; melatonin is readily available over-the-counter and it is affordable.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

1. Gonçalves AL, Martini Ferreira A, Ribeiro RT, et al. Randomised clinical trial comparing melatonin 3 mg, amitriptyline 25 mg and placebo for migraine prevention. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2016;87:1127-1132.

2. Silberstein SD, Holland S, Freitag F, et al. Evidence-based guideline update: pharmacologic treatment for episodic migraine prevention in adults: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society. Neurology. 2012;78:1337-1345.

3. Lipton RB, Bigal ME, Diamond M, et al; The American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention Advisory Group. Migraine prevalence, disease burden, and the need for preventive therapy. Neurology. 2007;68:343-349.

4. Silberstein SD. Practice parameter: evidence-based guidelines for migraine headache (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2000;55:754-762.

5. Alstadhaug KB, Odeh F, Salvesen R, et al. Prophylaxis of migraine with melatonin: a randomized controlled trial. Neurology. 2010;75:1527-1532.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 32-year-old woman comes to your office for help with her recurrent migraines, which she’s had since her early 20s. She is otherwise healthy and active. She is frustrated over the frequency of her migraines and the debilitation they cause. She has tried prophylactic medications in the past, but stopped taking them because of the adverse effects. What do you recommend for treatment?

Daily preventive medication can be helpful for chronic migraine sufferers whose headaches have a significant impact on their lives and who have a goal of reducing headache frequency or severity, disability, and/or avoiding acute headache medication escalation.2 An estimated 38% of patients with migraines are appropriate candidates for prophylactic therapy, but only 3% to 13% are taking preventive medications.3

Evidence-based guidelines from the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society state that antiepileptic drugs (divalproex sodium, sodium valproate, topiramate) and many beta-blockers (metoprolol, propranolol, timolol) are effective and should be recommended for migraine prevention (level A recommendation; based on ≥2 class I trials).2 Medications such as antidepressants (amitriptyline, venlafaxine) and other beta-blockers (atenolol, nadolol) are probably effective and can be considered (level B recommendation; based on one class I trial or 2 class II trials).2 However, adverse effects, such as somnolence, are listed as frequent with amitriptyline and occasional to frequent with topiramate.4

Researchers have investigated melatonin before. But a 2010 double-blind, crossover, randomized controlled trial (RCT) of 46 patients with 2 to 7 migraine attacks per month found no significant difference in reduction of headache frequency with extended-release melatonin 2 mg taken one hour before bed compared to placebo over an 8-week period.5

[polldaddy:9724288]

STUDY SUMMARY

Melatonin tops amitriptyline in >50% improvement in headache frequency

This RCT conducted in Brazil compared the effectiveness of melatonin to amitriptyline and placebo for migraine prevention in 196 adults (ages 18-65 years) with chronic migraines.1 Eligible patients had a history of at least 3 migraine attacks or 4 migraine headache days per month. Patients were randomized to take identically-appearing melatonin 3 mg, amitriptyline 25 mg, or placebo nightly. The investigators appear to have concealed allocation adequately, and used double-blinding.

The primary outcome was the number of headache days per month, comparing baseline with the 4 weeks of treatment. Secondary endpoints included reduction in migraine intensity, duration, number of analgesics used, and percentage of patients with more than 50% reduction in migraine headache days.

Compared to placebo, headache days per month were reduced in both the melatonin group (6.2 days vs 4.6 days, respectively; mean difference [MD], -1.6; 95% confidence interval [CI], -2.4 to -0.9) and the amitriptyline group (6.2 days vs 5 days, respectively; MD, -1.1; 95% CI, -1.5 to -0.7) at 12 weeks, based on intention-to-treat analysis. Mean headache intensity (0-10 pain scale) was also lower at 12 weeks in the melatonin group (4.8 vs 3.6; MD, -1.2; 95% CI, -1.6 to -0.8) and in the amitriptyline group (4.8 vs 3.5; MD, -1.3; 95% CI, -1.7 to -0.9), when compared to placebo.

Headache duration (hours/month) at 12 weeks was reduced in both groups (amitriptyline MD, -4.4 hours; 95% CI, -5.1 to -3.9; melatonin MD, -4.8 hours; 95% CI, -5.7 to -3.9), as was the number of analgesics used (amitriptyline MD, -1; 95% CI, -1.5 to -0.5; melatonin MD, -1; 95% CI, -1.4 to -0.6) when compared to placebo. There was no significant difference between the melatonin and amitriptyline groups for these outcomes.

Patients taking melatonin were more likely to have a >50% improvement in headache frequency compared to amitriptyline (54% vs 39%; number needed to treat [NNT]=7; P<.05); melatonin worked much better than placebo (54% vs 20%; NNT=3; P<.01).

Adverse events were reported more often in the amitriptyline group than in the melatonin group (46 vs 16; P<.03) with daytime sleepiness being the most frequent complaint (41% of patients in the amitriptyline group vs 18% of the melatonin group; number needed to harm [NNH]=5). There was no significant difference in adverse events between melatonin and placebo (16 vs 17; P=not significant). Melatonin resulted in weight loss (mean, -0.14 kg), whereas those taking amitriptyline gained weight (+0.97 kg; P<.01).

WHAT’S NEW

An effective migraine prevention alternative with minimal adverse effects

Melatonin is an accessible and affordable option for preventing migraine headaches in chronic sufferers. The 3-mg dosing reduces headache frequency—both in terms of the number of migraine headache days per month and in terms of the percentage of patients with a >50% reduction in headache events—as well as headache intensity, with minimal adverse effects.

CAVEATS

Product consistency, missing study data

This trial used 3-mg dosing, so it is not clear if other doses are also effective. In addition, because melatonin is available over-the-counter, the quality/actual doses may be less well regulated, and thus, there may be a lack of consistency between brands. Unlike clinical practice, neither the amitriptyline nor the melatonin dose was titrated according to patient response or adverse effects. As a result, we are not sure of the actual lowest effective dose, or if greater effect (with continued minimal adverse effects) could be achieved with higher doses.

Lastly, 69% to 75% of patients in the treatment groups completed the 16-week trial, but the authors of the study reported using 3 different analytic techniques to estimate missing data. The primary outcome included 178 of 196 randomized patients (90.8%). For the primary endpoint, the authors treated all missing data as non-headache days. It is unclear how these missing data would affect the outcome, although an analysis like this would tend towards a null effect.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Challenges are negligible

There are really no challenges to implementing this practice changer; melatonin is readily available over-the-counter and it is affordable.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 32-year-old woman comes to your office for help with her recurrent migraines, which she’s had since her early 20s. She is otherwise healthy and active. She is frustrated over the frequency of her migraines and the debilitation they cause. She has tried prophylactic medications in the past, but stopped taking them because of the adverse effects. What do you recommend for treatment?

Daily preventive medication can be helpful for chronic migraine sufferers whose headaches have a significant impact on their lives and who have a goal of reducing headache frequency or severity, disability, and/or avoiding acute headache medication escalation.2 An estimated 38% of patients with migraines are appropriate candidates for prophylactic therapy, but only 3% to 13% are taking preventive medications.3

Evidence-based guidelines from the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society state that antiepileptic drugs (divalproex sodium, sodium valproate, topiramate) and many beta-blockers (metoprolol, propranolol, timolol) are effective and should be recommended for migraine prevention (level A recommendation; based on ≥2 class I trials).2 Medications such as antidepressants (amitriptyline, venlafaxine) and other beta-blockers (atenolol, nadolol) are probably effective and can be considered (level B recommendation; based on one class I trial or 2 class II trials).2 However, adverse effects, such as somnolence, are listed as frequent with amitriptyline and occasional to frequent with topiramate.4

Researchers have investigated melatonin before. But a 2010 double-blind, crossover, randomized controlled trial (RCT) of 46 patients with 2 to 7 migraine attacks per month found no significant difference in reduction of headache frequency with extended-release melatonin 2 mg taken one hour before bed compared to placebo over an 8-week period.5

[polldaddy:9724288]

STUDY SUMMARY

Melatonin tops amitriptyline in >50% improvement in headache frequency

This RCT conducted in Brazil compared the effectiveness of melatonin to amitriptyline and placebo for migraine prevention in 196 adults (ages 18-65 years) with chronic migraines.1 Eligible patients had a history of at least 3 migraine attacks or 4 migraine headache days per month. Patients were randomized to take identically-appearing melatonin 3 mg, amitriptyline 25 mg, or placebo nightly. The investigators appear to have concealed allocation adequately, and used double-blinding.

The primary outcome was the number of headache days per month, comparing baseline with the 4 weeks of treatment. Secondary endpoints included reduction in migraine intensity, duration, number of analgesics used, and percentage of patients with more than 50% reduction in migraine headache days.

Compared to placebo, headache days per month were reduced in both the melatonin group (6.2 days vs 4.6 days, respectively; mean difference [MD], -1.6; 95% confidence interval [CI], -2.4 to -0.9) and the amitriptyline group (6.2 days vs 5 days, respectively; MD, -1.1; 95% CI, -1.5 to -0.7) at 12 weeks, based on intention-to-treat analysis. Mean headache intensity (0-10 pain scale) was also lower at 12 weeks in the melatonin group (4.8 vs 3.6; MD, -1.2; 95% CI, -1.6 to -0.8) and in the amitriptyline group (4.8 vs 3.5; MD, -1.3; 95% CI, -1.7 to -0.9), when compared to placebo.

Headache duration (hours/month) at 12 weeks was reduced in both groups (amitriptyline MD, -4.4 hours; 95% CI, -5.1 to -3.9; melatonin MD, -4.8 hours; 95% CI, -5.7 to -3.9), as was the number of analgesics used (amitriptyline MD, -1; 95% CI, -1.5 to -0.5; melatonin MD, -1; 95% CI, -1.4 to -0.6) when compared to placebo. There was no significant difference between the melatonin and amitriptyline groups for these outcomes.

Patients taking melatonin were more likely to have a >50% improvement in headache frequency compared to amitriptyline (54% vs 39%; number needed to treat [NNT]=7; P<.05); melatonin worked much better than placebo (54% vs 20%; NNT=3; P<.01).

Adverse events were reported more often in the amitriptyline group than in the melatonin group (46 vs 16; P<.03) with daytime sleepiness being the most frequent complaint (41% of patients in the amitriptyline group vs 18% of the melatonin group; number needed to harm [NNH]=5). There was no significant difference in adverse events between melatonin and placebo (16 vs 17; P=not significant). Melatonin resulted in weight loss (mean, -0.14 kg), whereas those taking amitriptyline gained weight (+0.97 kg; P<.01).

WHAT’S NEW

An effective migraine prevention alternative with minimal adverse effects

Melatonin is an accessible and affordable option for preventing migraine headaches in chronic sufferers. The 3-mg dosing reduces headache frequency—both in terms of the number of migraine headache days per month and in terms of the percentage of patients with a >50% reduction in headache events—as well as headache intensity, with minimal adverse effects.

CAVEATS

Product consistency, missing study data

This trial used 3-mg dosing, so it is not clear if other doses are also effective. In addition, because melatonin is available over-the-counter, the quality/actual doses may be less well regulated, and thus, there may be a lack of consistency between brands. Unlike clinical practice, neither the amitriptyline nor the melatonin dose was titrated according to patient response or adverse effects. As a result, we are not sure of the actual lowest effective dose, or if greater effect (with continued minimal adverse effects) could be achieved with higher doses.

Lastly, 69% to 75% of patients in the treatment groups completed the 16-week trial, but the authors of the study reported using 3 different analytic techniques to estimate missing data. The primary outcome included 178 of 196 randomized patients (90.8%). For the primary endpoint, the authors treated all missing data as non-headache days. It is unclear how these missing data would affect the outcome, although an analysis like this would tend towards a null effect.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Challenges are negligible

There are really no challenges to implementing this practice changer; melatonin is readily available over-the-counter and it is affordable.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

1. Gonçalves AL, Martini Ferreira A, Ribeiro RT, et al. Randomised clinical trial comparing melatonin 3 mg, amitriptyline 25 mg and placebo for migraine prevention. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2016;87:1127-1132.

2. Silberstein SD, Holland S, Freitag F, et al. Evidence-based guideline update: pharmacologic treatment for episodic migraine prevention in adults: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society. Neurology. 2012;78:1337-1345.

3. Lipton RB, Bigal ME, Diamond M, et al; The American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention Advisory Group. Migraine prevalence, disease burden, and the need for preventive therapy. Neurology. 2007;68:343-349.

4. Silberstein SD. Practice parameter: evidence-based guidelines for migraine headache (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2000;55:754-762.

5. Alstadhaug KB, Odeh F, Salvesen R, et al. Prophylaxis of migraine with melatonin: a randomized controlled trial. Neurology. 2010;75:1527-1532.

1. Gonçalves AL, Martini Ferreira A, Ribeiro RT, et al. Randomised clinical trial comparing melatonin 3 mg, amitriptyline 25 mg and placebo for migraine prevention. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2016;87:1127-1132.

2. Silberstein SD, Holland S, Freitag F, et al. Evidence-based guideline update: pharmacologic treatment for episodic migraine prevention in adults: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society. Neurology. 2012;78:1337-1345.

3. Lipton RB, Bigal ME, Diamond M, et al; The American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention Advisory Group. Migraine prevalence, disease burden, and the need for preventive therapy. Neurology. 2007;68:343-349.

4. Silberstein SD. Practice parameter: evidence-based guidelines for migraine headache (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2000;55:754-762.

5. Alstadhaug KB, Odeh F, Salvesen R, et al. Prophylaxis of migraine with melatonin: a randomized controlled trial. Neurology. 2010;75:1527-1532.

Copyright © 2017. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

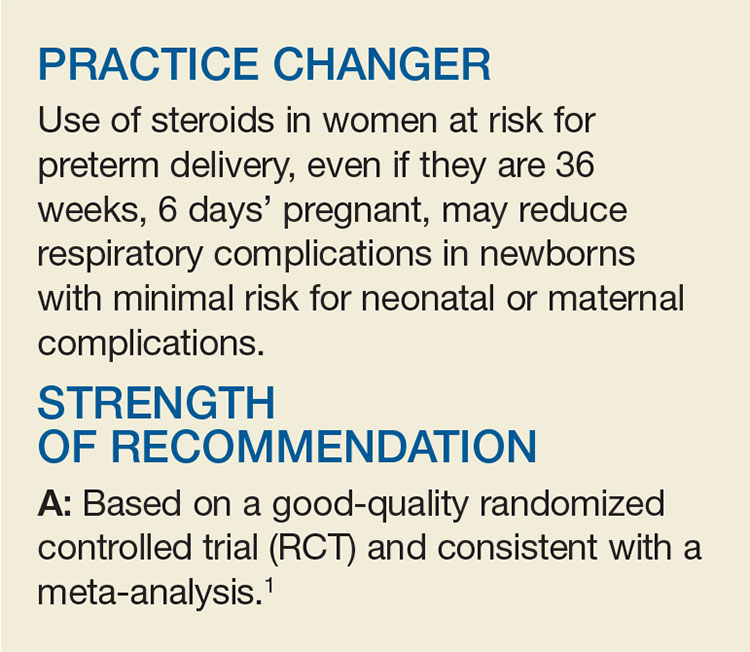

PRACTICE CHANGER

Recommend nightly melatonin 3 mg to your patients with chronic migraines, as it appears to be as effective as amitriptyline in reducing headaches and causes fewer adverse effects.

STRENGTH OF RECOMMENDATION

B: Based on a single, good quality randomized controlled trial.

Gonçalves AL, Martini Ferreira A, Ribeiro RT, et al. Randomised clinical trial comparing melatonin 3 mg, amitriptyline 25 mg and placebo for migraine prevention. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2016;87:1127-1132.1

“Cold Turkey” Works Best for Smoking Cessation

A 43-year-old man has a 35–pack-year smoking history and currently smokes one pack of cigarettes a day. He is eager to quit smoking since a close friend of his was recently diagnosed with lung cancer. He asks whether he should quit “cold turkey” or gradually. What do you recommend?

Between 2013 and 2014, one in five American adults reported using tobacco products some days or every day, and 66% of smokers in 2013 made at least one attempt to quit.2,3 The risks of tobacco use and the benefits of cessation are well established, and behavioral and pharmacologic interventions (both alone and in combination) increase smoking cessation rates.4 The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends that health care providers address tobacco use and cessation with patients at regular office visits and offer behavioral and pharmacologic interventions.5 Current guidelines, however, make no specific recommendations regarding gradual versus abrupt smoking cessation methods.5

A previous Cochrane review of 10 RCTs demonstrated no significant difference in quit rates between gradual cigarette reduction and abrupt cessation. The meta-analysis was limited, however, by differences in patient populations, outcome definitions, and types of interventions (both pharmacologic and behavioral).6

In a retrospective cohort study, French investigators reviewed an online database of more than 60,000 smokers who presented to nationwide cessation services. The researchers found that older participants (those 45 and older) and heavy smokers (≥ 21 cigarettes/d) were more likely to quit gradually than abruptly.7

STUDY SUMMARY

“Cold turkey” is better than gradual cessation at six months

A noninferiority RCT was conducted in England to assess whether gradual smoking cessation is as successful as abrupt cessation.1 The primary outcome was abstinence from smoking at four weeks, assessed using the Russell Standard. This set of six criteria (including validation by exhaled CO concentrations of < 10 ppm) is used by the National Centre for Smoking Cessation and Training to decrease variability of reported smoking cessation rates in English studies.8

Participants were recruited via letters from their primary care practice inviting them to participate in a smoking cessation study. The 697 subjects were randomized to either the abrupt-cessation group or the gradual-cessation group. Baseline characteristics were similar between groups.

All participants were asked to schedule a quit date for two weeks after their enrollment. Patients assigned to the gradual-cessation group were provided nicotine replacement patches (21 mg/d) and their choice of short-acting nicotine replacement therapy (NRT; gum, lozenges, nasal spray, sublingual tablets, inhalator, or mouth spray) to use in the two weeks leading up to the quit date. They were given instructions to reduce smoking by half of the baseline amount by the end of the first week, and to a quarter of baseline by the end of the second week.

Patients randomly assigned to the abrupt-cessation group were instructed to continue their current smoking habits until the cessation date; during those two weeks they were given nicotine patches (because the other group received them, and some evidence suggests that precessation NRT increases quit rates) but no short-acting NRT.

Following the cessation date, treatment in both groups was identical, including behavioral support, nicotine patches (21 mg/d), and the patient’s choice of short-acting NRT. Behavioral support consisted of visits with a research nurse at the patient’s primary care practice at the following intervals: weekly for two weeks before the quit date; the day before the quit date; weekly for four weeks after the quit date; and eight weeks after the quit date.

The chosen noninferiority margin was equal to a relative risk (RR) of 0.81 (19% reduction in effectiveness) of quitting gradually, compared with abrupt cessation of smoking. Quit rates in the gradual-reduction group did not reach the threshold for noninferiority; in fact, four-week abstinence was significantly more likely in the abrupt-cessation group than in the gradual-cessation group (49% vs 39.2%; RR, 0.80; number needed to treat [NNT], 10). Similarly, secondary outcomes of eight-week and six-month abstinence rates showed superiority of abrupt over gradual cessation. Six months after the quit date, 15.5% of the gradual-cessation group and 22% of the abrupt-cessation group remained abstinent (RR, 0.71; NNT, 15).

Patient preference plays a role

The investigators also found a difference in successful cessation based on the participants’ preferred method of cessation. Participants who preferred abrupt cessation were more likely to be abstinent at four weeks than participants who preferred gradual cessation (52.2% vs 38.3%).

Patients with a baseline preference for gradual cessation were equally as likely to successfully quit when allocated to abrupt cessation against their preference as when they were allocated to gradual cessation. Four-week abstinence was seen in 34.6% of patients who preferred and were allocated to gradual cessation and in 42% of patients who preferred gradual but were allocated to abrupt cessation.

WHAT’S NEW

Higher quality study; added element of preference

This large, well-designed, noninferiority study showed that abrupt cessation is superior to gradual cessation. The size and design of the study, including a standardized method of assessing cessation and a standardized intervention, make this a higher quality study than those in the Cochrane meta-analysis.6 This study also showed that participants who preferred gradual cessation were less likely to be successful—regardless of the method to which they were assigned.

CAVEATS

Generalizability limited by race and number of cigarettes smoked

Patients lost to follow-up at four weeks (35 in the abrupt-cessation group and 48 in the gradual-cessation group) were assumed to have continued smoking, which may have biased the results toward abrupt cessation. That said, the large number of study participants, along with the relatively small number lost to follow-up, minimizes this weakness.

The majority of participants were white, which may limit generalizability to nonwhite populations. In addition, participants smoked an average of 20 cigarettes per day and, as noted previously, an observational study of tobacco users in France found that heavy smokers (≥ 21 cigarettes/d) were more likely to quit gradually than abruptly. Therefore, results may not be generalizable to heavy smokers.7

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Considerable investment in behavioral support

One significant challenge is the implementation of such a structured tobacco cessation program in primary care. Both abrupt- and gradual-cessation groups were given considerable behavioral support from research nurses. Participants in this study were seen by a nurse seven times in the first six weeks of the study, and the intervention included nurse-created reduction schedules.

Even if patients in the study preferred one method of cessation to another, they were receptive to quitting either gradually or abruptly. In clinical practice, patients are often set in their desired method of cessation. In that setting, our role is then to inform them of the data and support them in whatever method they choose.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center for Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2017. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice (2017;66[3]:174-176).

1. Lindson-Hawley N, Banting M, West R, et al. Gradual versus abrupt smoking cessation: a randomized, controlled noninferiority trial. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164:585-592.

2. Hu SS, Neff L, Agaku IT, et al. Tobacco product use among adults—United States, 2013-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:685-691.

3. Lavinghouze SR, Malarcher A, Jama A, et al. Trends in quit attempts among adult cigarette smokers–United States, 2001-2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:1129-1135.

4. Patnode CD, Henderson JT, Thompson JH, et al. Behavioral counseling and pharmacotherapy interventions for tobacco cessation in adults, including pregnant women: a review of reviews for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163:608-621.

5. Siu AL; US Preventive Services Task Force. Behavioral and pharmacotherapy interventions for tobacco smoking cessation in adults, including pregnant women: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163:622-634.

6. Lindson-Hawley N, Aveyard P, Hughes JR. Reduction versus abrupt cessation in smokers who want to quit. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;11:CD008033.

7. Baha M, Le Faou AL. Gradual versus abrupt quitting among French treatment-seeking smokers. Prev Med. 2014;63: 96-102.

8. West R, Hajek P, Stead L, et al. Outcome criteria in smoking cessation trials: proposal for a common standard. Addiction. 2005;100:299-303.

A 43-year-old man has a 35–pack-year smoking history and currently smokes one pack of cigarettes a day. He is eager to quit smoking since a close friend of his was recently diagnosed with lung cancer. He asks whether he should quit “cold turkey” or gradually. What do you recommend?

Between 2013 and 2014, one in five American adults reported using tobacco products some days or every day, and 66% of smokers in 2013 made at least one attempt to quit.2,3 The risks of tobacco use and the benefits of cessation are well established, and behavioral and pharmacologic interventions (both alone and in combination) increase smoking cessation rates.4 The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends that health care providers address tobacco use and cessation with patients at regular office visits and offer behavioral and pharmacologic interventions.5 Current guidelines, however, make no specific recommendations regarding gradual versus abrupt smoking cessation methods.5

A previous Cochrane review of 10 RCTs demonstrated no significant difference in quit rates between gradual cigarette reduction and abrupt cessation. The meta-analysis was limited, however, by differences in patient populations, outcome definitions, and types of interventions (both pharmacologic and behavioral).6

In a retrospective cohort study, French investigators reviewed an online database of more than 60,000 smokers who presented to nationwide cessation services. The researchers found that older participants (those 45 and older) and heavy smokers (≥ 21 cigarettes/d) were more likely to quit gradually than abruptly.7

STUDY SUMMARY

“Cold turkey” is better than gradual cessation at six months

A noninferiority RCT was conducted in England to assess whether gradual smoking cessation is as successful as abrupt cessation.1 The primary outcome was abstinence from smoking at four weeks, assessed using the Russell Standard. This set of six criteria (including validation by exhaled CO concentrations of < 10 ppm) is used by the National Centre for Smoking Cessation and Training to decrease variability of reported smoking cessation rates in English studies.8

Participants were recruited via letters from their primary care practice inviting them to participate in a smoking cessation study. The 697 subjects were randomized to either the abrupt-cessation group or the gradual-cessation group. Baseline characteristics were similar between groups.

All participants were asked to schedule a quit date for two weeks after their enrollment. Patients assigned to the gradual-cessation group were provided nicotine replacement patches (21 mg/d) and their choice of short-acting nicotine replacement therapy (NRT; gum, lozenges, nasal spray, sublingual tablets, inhalator, or mouth spray) to use in the two weeks leading up to the quit date. They were given instructions to reduce smoking by half of the baseline amount by the end of the first week, and to a quarter of baseline by the end of the second week.

Patients randomly assigned to the abrupt-cessation group were instructed to continue their current smoking habits until the cessation date; during those two weeks they were given nicotine patches (because the other group received them, and some evidence suggests that precessation NRT increases quit rates) but no short-acting NRT.

Following the cessation date, treatment in both groups was identical, including behavioral support, nicotine patches (21 mg/d), and the patient’s choice of short-acting NRT. Behavioral support consisted of visits with a research nurse at the patient’s primary care practice at the following intervals: weekly for two weeks before the quit date; the day before the quit date; weekly for four weeks after the quit date; and eight weeks after the quit date.

The chosen noninferiority margin was equal to a relative risk (RR) of 0.81 (19% reduction in effectiveness) of quitting gradually, compared with abrupt cessation of smoking. Quit rates in the gradual-reduction group did not reach the threshold for noninferiority; in fact, four-week abstinence was significantly more likely in the abrupt-cessation group than in the gradual-cessation group (49% vs 39.2%; RR, 0.80; number needed to treat [NNT], 10). Similarly, secondary outcomes of eight-week and six-month abstinence rates showed superiority of abrupt over gradual cessation. Six months after the quit date, 15.5% of the gradual-cessation group and 22% of the abrupt-cessation group remained abstinent (RR, 0.71; NNT, 15).

Patient preference plays a role

The investigators also found a difference in successful cessation based on the participants’ preferred method of cessation. Participants who preferred abrupt cessation were more likely to be abstinent at four weeks than participants who preferred gradual cessation (52.2% vs 38.3%).

Patients with a baseline preference for gradual cessation were equally as likely to successfully quit when allocated to abrupt cessation against their preference as when they were allocated to gradual cessation. Four-week abstinence was seen in 34.6% of patients who preferred and were allocated to gradual cessation and in 42% of patients who preferred gradual but were allocated to abrupt cessation.

WHAT’S NEW

Higher quality study; added element of preference

This large, well-designed, noninferiority study showed that abrupt cessation is superior to gradual cessation. The size and design of the study, including a standardized method of assessing cessation and a standardized intervention, make this a higher quality study than those in the Cochrane meta-analysis.6 This study also showed that participants who preferred gradual cessation were less likely to be successful—regardless of the method to which they were assigned.

CAVEATS

Generalizability limited by race and number of cigarettes smoked

Patients lost to follow-up at four weeks (35 in the abrupt-cessation group and 48 in the gradual-cessation group) were assumed to have continued smoking, which may have biased the results toward abrupt cessation. That said, the large number of study participants, along with the relatively small number lost to follow-up, minimizes this weakness.

The majority of participants were white, which may limit generalizability to nonwhite populations. In addition, participants smoked an average of 20 cigarettes per day and, as noted previously, an observational study of tobacco users in France found that heavy smokers (≥ 21 cigarettes/d) were more likely to quit gradually than abruptly. Therefore, results may not be generalizable to heavy smokers.7

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Considerable investment in behavioral support

One significant challenge is the implementation of such a structured tobacco cessation program in primary care. Both abrupt- and gradual-cessation groups were given considerable behavioral support from research nurses. Participants in this study were seen by a nurse seven times in the first six weeks of the study, and the intervention included nurse-created reduction schedules.

Even if patients in the study preferred one method of cessation to another, they were receptive to quitting either gradually or abruptly. In clinical practice, patients are often set in their desired method of cessation. In that setting, our role is then to inform them of the data and support them in whatever method they choose.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center for Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2017. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice (2017;66[3]:174-176).

A 43-year-old man has a 35–pack-year smoking history and currently smokes one pack of cigarettes a day. He is eager to quit smoking since a close friend of his was recently diagnosed with lung cancer. He asks whether he should quit “cold turkey” or gradually. What do you recommend?

Between 2013 and 2014, one in five American adults reported using tobacco products some days or every day, and 66% of smokers in 2013 made at least one attempt to quit.2,3 The risks of tobacco use and the benefits of cessation are well established, and behavioral and pharmacologic interventions (both alone and in combination) increase smoking cessation rates.4 The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends that health care providers address tobacco use and cessation with patients at regular office visits and offer behavioral and pharmacologic interventions.5 Current guidelines, however, make no specific recommendations regarding gradual versus abrupt smoking cessation methods.5

A previous Cochrane review of 10 RCTs demonstrated no significant difference in quit rates between gradual cigarette reduction and abrupt cessation. The meta-analysis was limited, however, by differences in patient populations, outcome definitions, and types of interventions (both pharmacologic and behavioral).6

In a retrospective cohort study, French investigators reviewed an online database of more than 60,000 smokers who presented to nationwide cessation services. The researchers found that older participants (those 45 and older) and heavy smokers (≥ 21 cigarettes/d) were more likely to quit gradually than abruptly.7

STUDY SUMMARY

“Cold turkey” is better than gradual cessation at six months

A noninferiority RCT was conducted in England to assess whether gradual smoking cessation is as successful as abrupt cessation.1 The primary outcome was abstinence from smoking at four weeks, assessed using the Russell Standard. This set of six criteria (including validation by exhaled CO concentrations of < 10 ppm) is used by the National Centre for Smoking Cessation and Training to decrease variability of reported smoking cessation rates in English studies.8

Participants were recruited via letters from their primary care practice inviting them to participate in a smoking cessation study. The 697 subjects were randomized to either the abrupt-cessation group or the gradual-cessation group. Baseline characteristics were similar between groups.

All participants were asked to schedule a quit date for two weeks after their enrollment. Patients assigned to the gradual-cessation group were provided nicotine replacement patches (21 mg/d) and their choice of short-acting nicotine replacement therapy (NRT; gum, lozenges, nasal spray, sublingual tablets, inhalator, or mouth spray) to use in the two weeks leading up to the quit date. They were given instructions to reduce smoking by half of the baseline amount by the end of the first week, and to a quarter of baseline by the end of the second week.

Patients randomly assigned to the abrupt-cessation group were instructed to continue their current smoking habits until the cessation date; during those two weeks they were given nicotine patches (because the other group received them, and some evidence suggests that precessation NRT increases quit rates) but no short-acting NRT.

Following the cessation date, treatment in both groups was identical, including behavioral support, nicotine patches (21 mg/d), and the patient’s choice of short-acting NRT. Behavioral support consisted of visits with a research nurse at the patient’s primary care practice at the following intervals: weekly for two weeks before the quit date; the day before the quit date; weekly for four weeks after the quit date; and eight weeks after the quit date.

The chosen noninferiority margin was equal to a relative risk (RR) of 0.81 (19% reduction in effectiveness) of quitting gradually, compared with abrupt cessation of smoking. Quit rates in the gradual-reduction group did not reach the threshold for noninferiority; in fact, four-week abstinence was significantly more likely in the abrupt-cessation group than in the gradual-cessation group (49% vs 39.2%; RR, 0.80; number needed to treat [NNT], 10). Similarly, secondary outcomes of eight-week and six-month abstinence rates showed superiority of abrupt over gradual cessation. Six months after the quit date, 15.5% of the gradual-cessation group and 22% of the abrupt-cessation group remained abstinent (RR, 0.71; NNT, 15).

Patient preference plays a role

The investigators also found a difference in successful cessation based on the participants’ preferred method of cessation. Participants who preferred abrupt cessation were more likely to be abstinent at four weeks than participants who preferred gradual cessation (52.2% vs 38.3%).

Patients with a baseline preference for gradual cessation were equally as likely to successfully quit when allocated to abrupt cessation against their preference as when they were allocated to gradual cessation. Four-week abstinence was seen in 34.6% of patients who preferred and were allocated to gradual cessation and in 42% of patients who preferred gradual but were allocated to abrupt cessation.

WHAT’S NEW

Higher quality study; added element of preference

This large, well-designed, noninferiority study showed that abrupt cessation is superior to gradual cessation. The size and design of the study, including a standardized method of assessing cessation and a standardized intervention, make this a higher quality study than those in the Cochrane meta-analysis.6 This study also showed that participants who preferred gradual cessation were less likely to be successful—regardless of the method to which they were assigned.

CAVEATS

Generalizability limited by race and number of cigarettes smoked

Patients lost to follow-up at four weeks (35 in the abrupt-cessation group and 48 in the gradual-cessation group) were assumed to have continued smoking, which may have biased the results toward abrupt cessation. That said, the large number of study participants, along with the relatively small number lost to follow-up, minimizes this weakness.

The majority of participants were white, which may limit generalizability to nonwhite populations. In addition, participants smoked an average of 20 cigarettes per day and, as noted previously, an observational study of tobacco users in France found that heavy smokers (≥ 21 cigarettes/d) were more likely to quit gradually than abruptly. Therefore, results may not be generalizable to heavy smokers.7

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Considerable investment in behavioral support

One significant challenge is the implementation of such a structured tobacco cessation program in primary care. Both abrupt- and gradual-cessation groups were given considerable behavioral support from research nurses. Participants in this study were seen by a nurse seven times in the first six weeks of the study, and the intervention included nurse-created reduction schedules.

Even if patients in the study preferred one method of cessation to another, they were receptive to quitting either gradually or abruptly. In clinical practice, patients are often set in their desired method of cessation. In that setting, our role is then to inform them of the data and support them in whatever method they choose.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center for Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2017. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice (2017;66[3]:174-176).

1. Lindson-Hawley N, Banting M, West R, et al. Gradual versus abrupt smoking cessation: a randomized, controlled noninferiority trial. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164:585-592.

2. Hu SS, Neff L, Agaku IT, et al. Tobacco product use among adults—United States, 2013-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:685-691.

3. Lavinghouze SR, Malarcher A, Jama A, et al. Trends in quit attempts among adult cigarette smokers–United States, 2001-2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:1129-1135.

4. Patnode CD, Henderson JT, Thompson JH, et al. Behavioral counseling and pharmacotherapy interventions for tobacco cessation in adults, including pregnant women: a review of reviews for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163:608-621.

5. Siu AL; US Preventive Services Task Force. Behavioral and pharmacotherapy interventions for tobacco smoking cessation in adults, including pregnant women: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163:622-634.

6. Lindson-Hawley N, Aveyard P, Hughes JR. Reduction versus abrupt cessation in smokers who want to quit. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;11:CD008033.

7. Baha M, Le Faou AL. Gradual versus abrupt quitting among French treatment-seeking smokers. Prev Med. 2014;63: 96-102.

8. West R, Hajek P, Stead L, et al. Outcome criteria in smoking cessation trials: proposal for a common standard. Addiction. 2005;100:299-303.

1. Lindson-Hawley N, Banting M, West R, et al. Gradual versus abrupt smoking cessation: a randomized, controlled noninferiority trial. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164:585-592.

2. Hu SS, Neff L, Agaku IT, et al. Tobacco product use among adults—United States, 2013-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:685-691.

3. Lavinghouze SR, Malarcher A, Jama A, et al. Trends in quit attempts among adult cigarette smokers–United States, 2001-2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:1129-1135.

4. Patnode CD, Henderson JT, Thompson JH, et al. Behavioral counseling and pharmacotherapy interventions for tobacco cessation in adults, including pregnant women: a review of reviews for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163:608-621.

5. Siu AL; US Preventive Services Task Force. Behavioral and pharmacotherapy interventions for tobacco smoking cessation in adults, including pregnant women: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163:622-634.