User login

Guidelines on Away Rotations in Dermatology Programs

Medical students often perform away rotations (also called visiting electives) to gain exposure to educational experiences in a particular specialty, learn about a program, and show interest in a certain program. Away rotations also allow applicants to meet and form relationships with mentors and faculty outside of their home institution. For residency programs, away rotations provide an opportunity for a holistic review of applicants by allowing program directors to get to know potential residency applicants and assess their performance in the clinical environment and among the program’s team. In a National Resident Matching Program survey, program directors (n=17) reported that prior knowledge of an applicant is an important factor in selecting applicants to interview (82.4%) and rank (58.8%).1

In this article, we discuss the importance of away rotations in dermatology and provide an overview of the Organization of Program Director Associations (OPDA) and Association of Professors of Dermatology (APD) guidelines for away rotations.

Importance of the Away Rotation in the Match

According to the Association of American Medical Colleges, 86.7% of dermatology applicants (N=345) completed one or more away rotations (mean, 2.7) in 2020.2 Winterton et al3 reported that 47% of dermatology applicants (N=45) matched at a program where they completed an away rotation. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of applicants matching to their home program was reported as 26.7% (N=641), which jumped to 40.3% (N=231) in the 2020-2021 cycle.4 Given that the majority of dermatology applicants reportedly match either at their home program or at programs where they completed an away rotation, the benefits of away rotations are high, particularly in a competitive specialty such as dermatology and particularly for applicants without a dermatology program at their home institution. However, it must be acknowledged that correlation does not necessarily mean causation, as away rotations have not necessarily been shown to increase applicants’ chances of matching for the most competitive specialties.5

OPDA Guidelines for Away Rotations

In 2021, the Coalition of Physician Accountability’s Undergraduate Medical Education-Graduate Medical Education Review Committee recommended creating a workgroup to explore the function and value of away rotations for medical students, programs, and institutions, with a particular focus on issues of equity (eg, accessibility, assessment, opportunity) for underrepresented in medicine students and those with financial disadvantages.6 The OPDA workgroup evaluated the advantages and disadvantages of away rotations across specialties. The disadvantages included that away rotations may decrease resources to students at their own institution, particularly if faculty time and energy are funneled/dedicated to away rotators instead of internal rotators, and may impart bias into the recruitment process. Additionally, there is a consideration of equity given the considerable cost and time commitment of travel and housing for students at another institution. In 2022, the estimated cost of an away rotation in dermatology ranged from $1390 to $5500 per rotation.7 Visiting scholarships may be available at some institutions but typically are reserved for underrepresented in medicine students.8 Virtual rotations offered at some programs offset the cost-prohibitiveness of an in-person away rotation; however, they are not universally offered and may be limited in allowing for meaningful interactions between students and program faculty and residents.

The OPDA away rotation workgroup recommended that (1) each specialty publish guidelines regarding the necessity and number of recommended away rotations; (2) specialties publish explicit language regarding the use of program preference signals to programs where students rotated; (3) programs be transparent about the purpose and value of an away rotation, including explicitly stating whether a formal interview is guaranteed; and (4) the Association of American Medical Colleges create a repository of these specialty-specific recommendations.9

APD Guidelines for Away Rotations

In response to the OPDA recommendations, the APD Residency Program Directors Section developed dermatology-specific guidelines for away rotations and established guidelines in other specialties.10 The APD recommends completing up to 2 away rotations, or 3 for those without a home program, if desired. This number was chosen in acknowledgment of the importance of external program experiences, along with the recognition of the financial and time restrictions associated with away rotations as well as the limited number of spots for rotating students. Away rotations are not mandatory. The APD guidelines explain the purpose and value of an away rotation while also noting that these rotations do not necessarily guarantee a formal interview and recommending that programs be transparent about their policies on interview invitations, which may vary.10

Final Thoughts

Publishing specialty-specific guidelines on away rotations is one step toward streamlining the process as well as increasing transparency on the importance of these external program experiences in the application process and residency match. Ideally, away rotations provide a valuable educational experience in which students and program directors get to know each other in a mutually beneficial manner; however, away rotations are not required for securing an interview or matching at a program, and there also are recognized disadvantages to away rotations, particularly with regard to equity, that we must continue to weigh as a specialty. The APD will continue its collaborative work to evaluate our application processes to support a sustainable and equitable system.

- National Resident Matching Program. Results of the 2021 NRMP program director survey. Published August 2021. Accessed May 17, 2023. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/2021-PD-Survey-Report-for-WWW.pdf

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Away rotations of U.S. medical school graduates by intended specialty, 2020 AAMC Medical School Graduation Questionnaire (GQ). Published September 24, 2020. Accessed May 17, 2023. https://students-residents.aamc.org/media/9496/download

- Winterton M, Ahn J, Bernstein J. The prevalence and cost of medical student visiting rotations. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16:291. doi:10.1186/s12909-016-0805-z

- Dowdle TS, Ryan MP, Wagner RF. Internal and geographic dermatology match trends in the age of COVID-19. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1364-1366. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.08.004

- Griffith M, DeMasi SC, McGrath AJ, et al. Time to reevaluate the away rotation: improving return on investment for students and schools. Acad Med. 2019;94:496-500. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000002505

- Coalition for Physician Accountability. The Coalition for Physician Accountability’s Undergraduate Medication Education-Graduate Medical Education Review Committee (UGRC): recommendations for comprehensive improvement in the UME-GME transition. Published August 26, 2021. Accessed May 18, 2023. https://physicianaccountability.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/UGRC-Coalition-Report-FINAL.pdf

- Cucka B, Grant-Kels JM. Ethical implications of the high cost of medical student visiting dermatology rotations. Clin Dermatol. 2022;40:539-540.

- Dahak S, Fernandez JM, Rosman IS. Funded dermatology visiting elective rotations for medical students who are underrepresented in medicine: a cross-sectional analysis [published online November 15, 2022]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:941-943.

- Council of Medical Specialty Societies. The Organization of Program Director Associations (OPDA): away rotations workgroup. Published July 26, 2022. Accessed May 18, 2023. https://cmss.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/OPDA-Work-Group-on-Away-Rotations-7.26.2022-1.pdf

- Association of Professors of Dermatology. Recommendations regarding away electives. Published December 14, 2022. Accessed May 18, 2023. https://www.dermatologyprofessors.org/files/APD%20recommendations%20on%20away%20rotations%202023-2024.pdf

Medical students often perform away rotations (also called visiting electives) to gain exposure to educational experiences in a particular specialty, learn about a program, and show interest in a certain program. Away rotations also allow applicants to meet and form relationships with mentors and faculty outside of their home institution. For residency programs, away rotations provide an opportunity for a holistic review of applicants by allowing program directors to get to know potential residency applicants and assess their performance in the clinical environment and among the program’s team. In a National Resident Matching Program survey, program directors (n=17) reported that prior knowledge of an applicant is an important factor in selecting applicants to interview (82.4%) and rank (58.8%).1

In this article, we discuss the importance of away rotations in dermatology and provide an overview of the Organization of Program Director Associations (OPDA) and Association of Professors of Dermatology (APD) guidelines for away rotations.

Importance of the Away Rotation in the Match

According to the Association of American Medical Colleges, 86.7% of dermatology applicants (N=345) completed one or more away rotations (mean, 2.7) in 2020.2 Winterton et al3 reported that 47% of dermatology applicants (N=45) matched at a program where they completed an away rotation. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of applicants matching to their home program was reported as 26.7% (N=641), which jumped to 40.3% (N=231) in the 2020-2021 cycle.4 Given that the majority of dermatology applicants reportedly match either at their home program or at programs where they completed an away rotation, the benefits of away rotations are high, particularly in a competitive specialty such as dermatology and particularly for applicants without a dermatology program at their home institution. However, it must be acknowledged that correlation does not necessarily mean causation, as away rotations have not necessarily been shown to increase applicants’ chances of matching for the most competitive specialties.5

OPDA Guidelines for Away Rotations

In 2021, the Coalition of Physician Accountability’s Undergraduate Medical Education-Graduate Medical Education Review Committee recommended creating a workgroup to explore the function and value of away rotations for medical students, programs, and institutions, with a particular focus on issues of equity (eg, accessibility, assessment, opportunity) for underrepresented in medicine students and those with financial disadvantages.6 The OPDA workgroup evaluated the advantages and disadvantages of away rotations across specialties. The disadvantages included that away rotations may decrease resources to students at their own institution, particularly if faculty time and energy are funneled/dedicated to away rotators instead of internal rotators, and may impart bias into the recruitment process. Additionally, there is a consideration of equity given the considerable cost and time commitment of travel and housing for students at another institution. In 2022, the estimated cost of an away rotation in dermatology ranged from $1390 to $5500 per rotation.7 Visiting scholarships may be available at some institutions but typically are reserved for underrepresented in medicine students.8 Virtual rotations offered at some programs offset the cost-prohibitiveness of an in-person away rotation; however, they are not universally offered and may be limited in allowing for meaningful interactions between students and program faculty and residents.

The OPDA away rotation workgroup recommended that (1) each specialty publish guidelines regarding the necessity and number of recommended away rotations; (2) specialties publish explicit language regarding the use of program preference signals to programs where students rotated; (3) programs be transparent about the purpose and value of an away rotation, including explicitly stating whether a formal interview is guaranteed; and (4) the Association of American Medical Colleges create a repository of these specialty-specific recommendations.9

APD Guidelines for Away Rotations

In response to the OPDA recommendations, the APD Residency Program Directors Section developed dermatology-specific guidelines for away rotations and established guidelines in other specialties.10 The APD recommends completing up to 2 away rotations, or 3 for those without a home program, if desired. This number was chosen in acknowledgment of the importance of external program experiences, along with the recognition of the financial and time restrictions associated with away rotations as well as the limited number of spots for rotating students. Away rotations are not mandatory. The APD guidelines explain the purpose and value of an away rotation while also noting that these rotations do not necessarily guarantee a formal interview and recommending that programs be transparent about their policies on interview invitations, which may vary.10

Final Thoughts

Publishing specialty-specific guidelines on away rotations is one step toward streamlining the process as well as increasing transparency on the importance of these external program experiences in the application process and residency match. Ideally, away rotations provide a valuable educational experience in which students and program directors get to know each other in a mutually beneficial manner; however, away rotations are not required for securing an interview or matching at a program, and there also are recognized disadvantages to away rotations, particularly with regard to equity, that we must continue to weigh as a specialty. The APD will continue its collaborative work to evaluate our application processes to support a sustainable and equitable system.

Medical students often perform away rotations (also called visiting electives) to gain exposure to educational experiences in a particular specialty, learn about a program, and show interest in a certain program. Away rotations also allow applicants to meet and form relationships with mentors and faculty outside of their home institution. For residency programs, away rotations provide an opportunity for a holistic review of applicants by allowing program directors to get to know potential residency applicants and assess their performance in the clinical environment and among the program’s team. In a National Resident Matching Program survey, program directors (n=17) reported that prior knowledge of an applicant is an important factor in selecting applicants to interview (82.4%) and rank (58.8%).1

In this article, we discuss the importance of away rotations in dermatology and provide an overview of the Organization of Program Director Associations (OPDA) and Association of Professors of Dermatology (APD) guidelines for away rotations.

Importance of the Away Rotation in the Match

According to the Association of American Medical Colleges, 86.7% of dermatology applicants (N=345) completed one or more away rotations (mean, 2.7) in 2020.2 Winterton et al3 reported that 47% of dermatology applicants (N=45) matched at a program where they completed an away rotation. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of applicants matching to their home program was reported as 26.7% (N=641), which jumped to 40.3% (N=231) in the 2020-2021 cycle.4 Given that the majority of dermatology applicants reportedly match either at their home program or at programs where they completed an away rotation, the benefits of away rotations are high, particularly in a competitive specialty such as dermatology and particularly for applicants without a dermatology program at their home institution. However, it must be acknowledged that correlation does not necessarily mean causation, as away rotations have not necessarily been shown to increase applicants’ chances of matching for the most competitive specialties.5

OPDA Guidelines for Away Rotations

In 2021, the Coalition of Physician Accountability’s Undergraduate Medical Education-Graduate Medical Education Review Committee recommended creating a workgroup to explore the function and value of away rotations for medical students, programs, and institutions, with a particular focus on issues of equity (eg, accessibility, assessment, opportunity) for underrepresented in medicine students and those with financial disadvantages.6 The OPDA workgroup evaluated the advantages and disadvantages of away rotations across specialties. The disadvantages included that away rotations may decrease resources to students at their own institution, particularly if faculty time and energy are funneled/dedicated to away rotators instead of internal rotators, and may impart bias into the recruitment process. Additionally, there is a consideration of equity given the considerable cost and time commitment of travel and housing for students at another institution. In 2022, the estimated cost of an away rotation in dermatology ranged from $1390 to $5500 per rotation.7 Visiting scholarships may be available at some institutions but typically are reserved for underrepresented in medicine students.8 Virtual rotations offered at some programs offset the cost-prohibitiveness of an in-person away rotation; however, they are not universally offered and may be limited in allowing for meaningful interactions between students and program faculty and residents.

The OPDA away rotation workgroup recommended that (1) each specialty publish guidelines regarding the necessity and number of recommended away rotations; (2) specialties publish explicit language regarding the use of program preference signals to programs where students rotated; (3) programs be transparent about the purpose and value of an away rotation, including explicitly stating whether a formal interview is guaranteed; and (4) the Association of American Medical Colleges create a repository of these specialty-specific recommendations.9

APD Guidelines for Away Rotations

In response to the OPDA recommendations, the APD Residency Program Directors Section developed dermatology-specific guidelines for away rotations and established guidelines in other specialties.10 The APD recommends completing up to 2 away rotations, or 3 for those without a home program, if desired. This number was chosen in acknowledgment of the importance of external program experiences, along with the recognition of the financial and time restrictions associated with away rotations as well as the limited number of spots for rotating students. Away rotations are not mandatory. The APD guidelines explain the purpose and value of an away rotation while also noting that these rotations do not necessarily guarantee a formal interview and recommending that programs be transparent about their policies on interview invitations, which may vary.10

Final Thoughts

Publishing specialty-specific guidelines on away rotations is one step toward streamlining the process as well as increasing transparency on the importance of these external program experiences in the application process and residency match. Ideally, away rotations provide a valuable educational experience in which students and program directors get to know each other in a mutually beneficial manner; however, away rotations are not required for securing an interview or matching at a program, and there also are recognized disadvantages to away rotations, particularly with regard to equity, that we must continue to weigh as a specialty. The APD will continue its collaborative work to evaluate our application processes to support a sustainable and equitable system.

- National Resident Matching Program. Results of the 2021 NRMP program director survey. Published August 2021. Accessed May 17, 2023. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/2021-PD-Survey-Report-for-WWW.pdf

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Away rotations of U.S. medical school graduates by intended specialty, 2020 AAMC Medical School Graduation Questionnaire (GQ). Published September 24, 2020. Accessed May 17, 2023. https://students-residents.aamc.org/media/9496/download

- Winterton M, Ahn J, Bernstein J. The prevalence and cost of medical student visiting rotations. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16:291. doi:10.1186/s12909-016-0805-z

- Dowdle TS, Ryan MP, Wagner RF. Internal and geographic dermatology match trends in the age of COVID-19. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1364-1366. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.08.004

- Griffith M, DeMasi SC, McGrath AJ, et al. Time to reevaluate the away rotation: improving return on investment for students and schools. Acad Med. 2019;94:496-500. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000002505

- Coalition for Physician Accountability. The Coalition for Physician Accountability’s Undergraduate Medication Education-Graduate Medical Education Review Committee (UGRC): recommendations for comprehensive improvement in the UME-GME transition. Published August 26, 2021. Accessed May 18, 2023. https://physicianaccountability.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/UGRC-Coalition-Report-FINAL.pdf

- Cucka B, Grant-Kels JM. Ethical implications of the high cost of medical student visiting dermatology rotations. Clin Dermatol. 2022;40:539-540.

- Dahak S, Fernandez JM, Rosman IS. Funded dermatology visiting elective rotations for medical students who are underrepresented in medicine: a cross-sectional analysis [published online November 15, 2022]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:941-943.

- Council of Medical Specialty Societies. The Organization of Program Director Associations (OPDA): away rotations workgroup. Published July 26, 2022. Accessed May 18, 2023. https://cmss.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/OPDA-Work-Group-on-Away-Rotations-7.26.2022-1.pdf

- Association of Professors of Dermatology. Recommendations regarding away electives. Published December 14, 2022. Accessed May 18, 2023. https://www.dermatologyprofessors.org/files/APD%20recommendations%20on%20away%20rotations%202023-2024.pdf

- National Resident Matching Program. Results of the 2021 NRMP program director survey. Published August 2021. Accessed May 17, 2023. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/2021-PD-Survey-Report-for-WWW.pdf

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Away rotations of U.S. medical school graduates by intended specialty, 2020 AAMC Medical School Graduation Questionnaire (GQ). Published September 24, 2020. Accessed May 17, 2023. https://students-residents.aamc.org/media/9496/download

- Winterton M, Ahn J, Bernstein J. The prevalence and cost of medical student visiting rotations. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16:291. doi:10.1186/s12909-016-0805-z

- Dowdle TS, Ryan MP, Wagner RF. Internal and geographic dermatology match trends in the age of COVID-19. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1364-1366. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.08.004

- Griffith M, DeMasi SC, McGrath AJ, et al. Time to reevaluate the away rotation: improving return on investment for students and schools. Acad Med. 2019;94:496-500. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000002505

- Coalition for Physician Accountability. The Coalition for Physician Accountability’s Undergraduate Medication Education-Graduate Medical Education Review Committee (UGRC): recommendations for comprehensive improvement in the UME-GME transition. Published August 26, 2021. Accessed May 18, 2023. https://physicianaccountability.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/UGRC-Coalition-Report-FINAL.pdf

- Cucka B, Grant-Kels JM. Ethical implications of the high cost of medical student visiting dermatology rotations. Clin Dermatol. 2022;40:539-540.

- Dahak S, Fernandez JM, Rosman IS. Funded dermatology visiting elective rotations for medical students who are underrepresented in medicine: a cross-sectional analysis [published online November 15, 2022]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:941-943.

- Council of Medical Specialty Societies. The Organization of Program Director Associations (OPDA): away rotations workgroup. Published July 26, 2022. Accessed May 18, 2023. https://cmss.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/OPDA-Work-Group-on-Away-Rotations-7.26.2022-1.pdf

- Association of Professors of Dermatology. Recommendations regarding away electives. Published December 14, 2022. Accessed May 18, 2023. https://www.dermatologyprofessors.org/files/APD%20recommendations%20on%20away%20rotations%202023-2024.pdf

Practice Points

- Away rotations are an important tool for both applicants and residency programs during the application process.

- The Association of Professors of Dermatology (APD) recommends completing up to 2 external program experiences, or 3 if the student has no home program, ideally to be completed early in the fourth year of medical school prior to interview invitations.

- Away rotations may have considerable cost and time restrictions on applicants, which the APD recognizes and weighs in its recommendations. There may be program-specific scholarships and opportunities available to help with the cost of away rotations.

Interacting With Dermatology Patients Online: Private Practice vs Academic Institute Website Content

Patients are finding it easier to use online resources to discover health care providers who fit their personalized needs. In the United States, approximately 70% of individuals use the internet to find health care information, and 80% are influenced by the information presented to them on health care websites.1 Patients utilize the internet to better understand treatments offered by providers and their prices as well as how other patients have rated their experience. Providers in private practice also have noticed that many patients are referring themselves vs obtaining a referral from another provider.2 As a result, it is critical for practice websites to have information that is of value to their patients, including the unique qualities and treatments offered. The purpose of this study was to analyze the differences between the content presented on dermatology private practice websites and academic institutional websites.

Methods

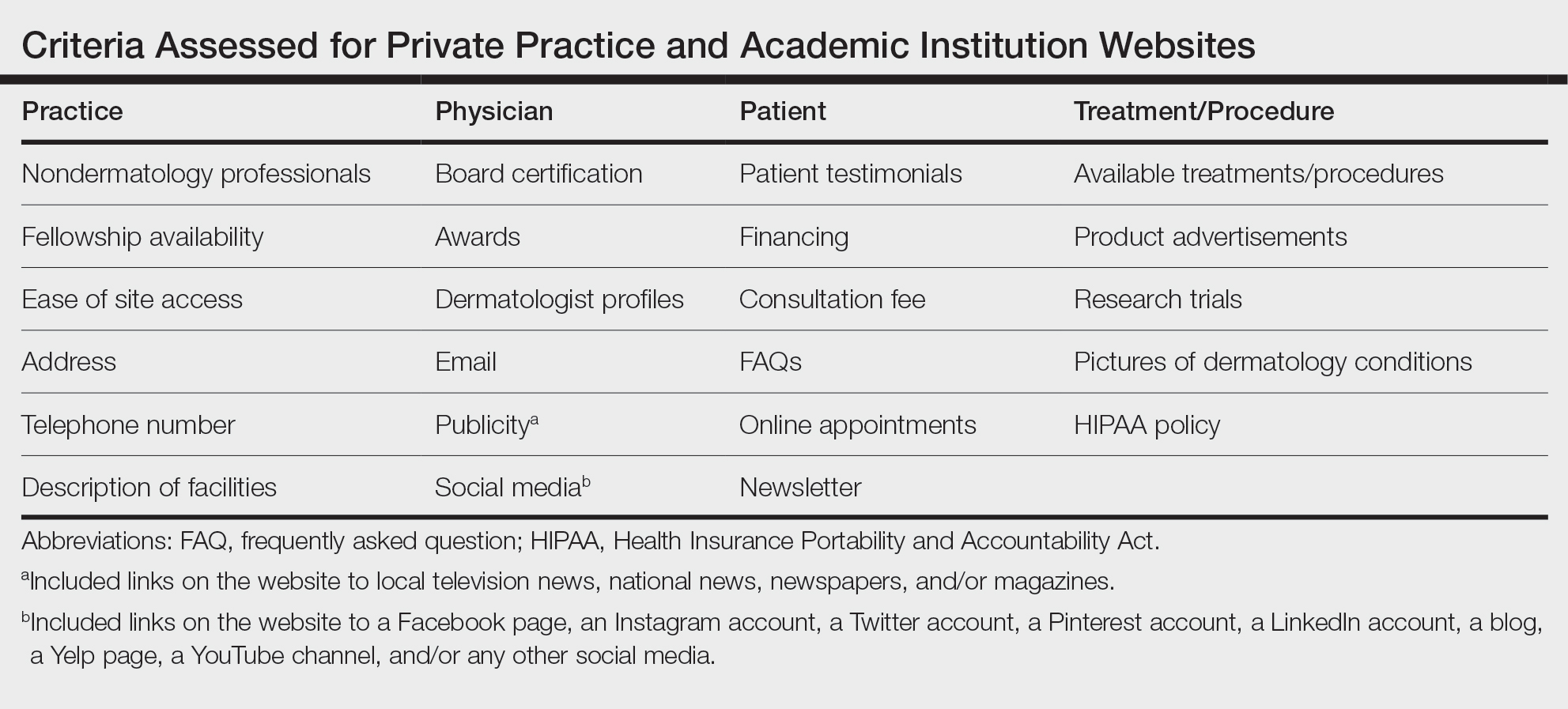

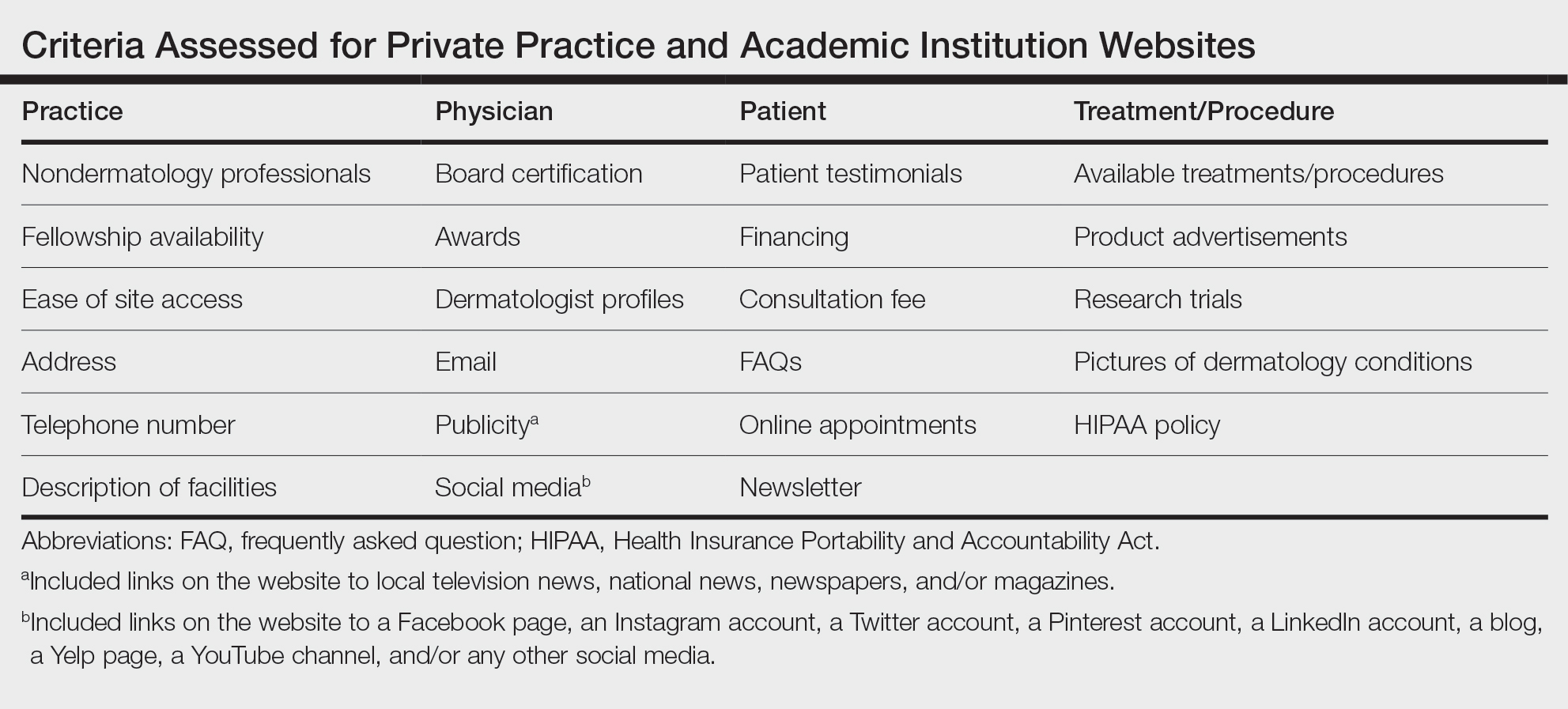

Websites Searched —All 140 academic dermatology programs, including both allopathic and osteopathic programs, were queried from the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) database in March 2022. 3 First, the dermatology departmental websites for each program were analyzed to see if they contained information pertinent to patients. Any website that lacked this information or only had information relevant to the dermatology residency program was excluded from the study. After exclusion, a total of 113 websites were used in the academic website cohort. The private practices were found through an incognito Google search with the search term dermatologist and matched to be within 5 miles of each academic institution. The private practices that included at least one board-certified dermatologist and received the highest number of reviews on Google compared to other practices in the same region—a measure of online reputation—were selected to be in the private practice cohort (N = 113). Any duplicate practices, practices belonging to the same conglomerate company, or multispecialty clinics were excluded from the study. Board-certified dermatologists were confirmed using the Find a Dermatologist tool on the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) website. 4

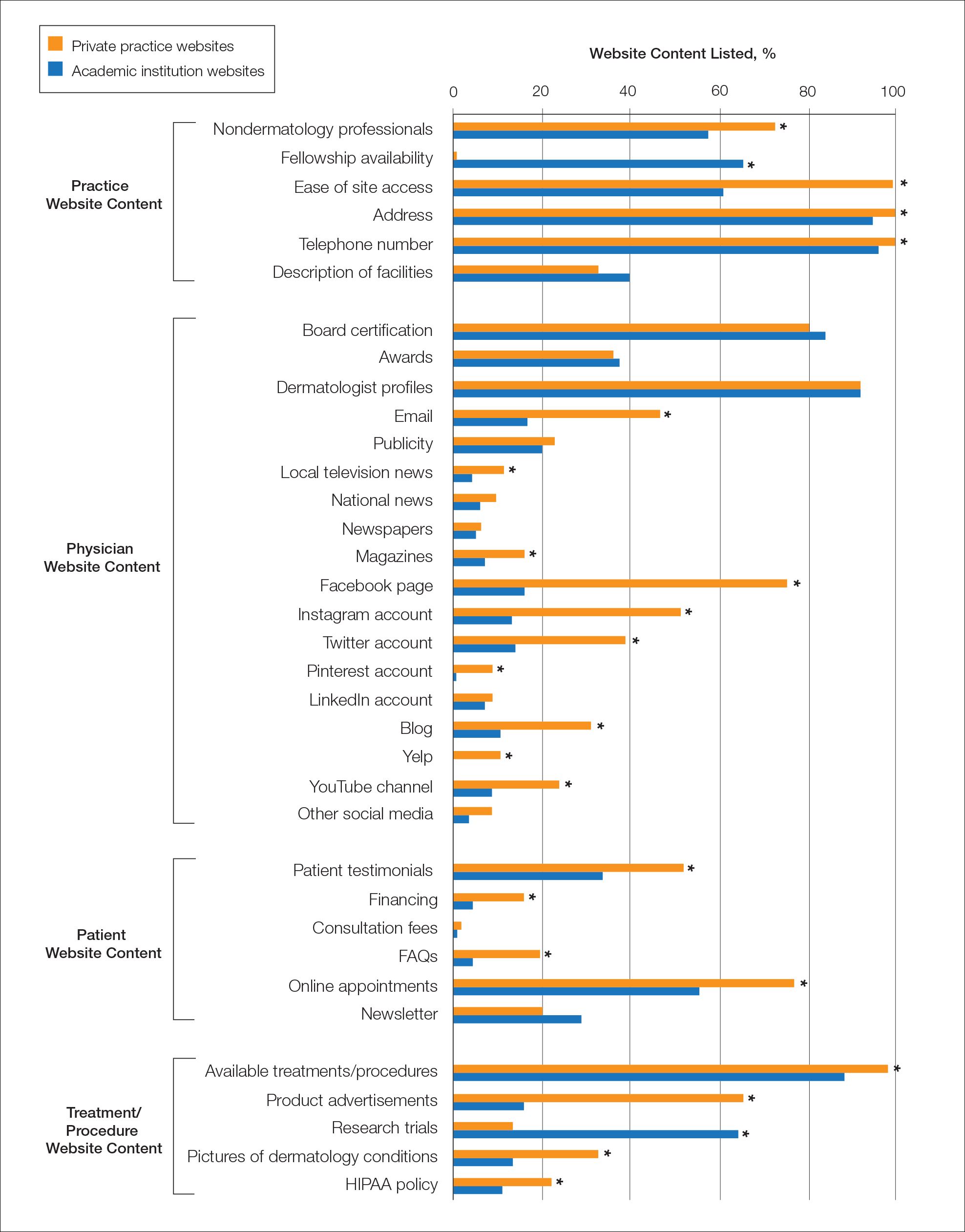

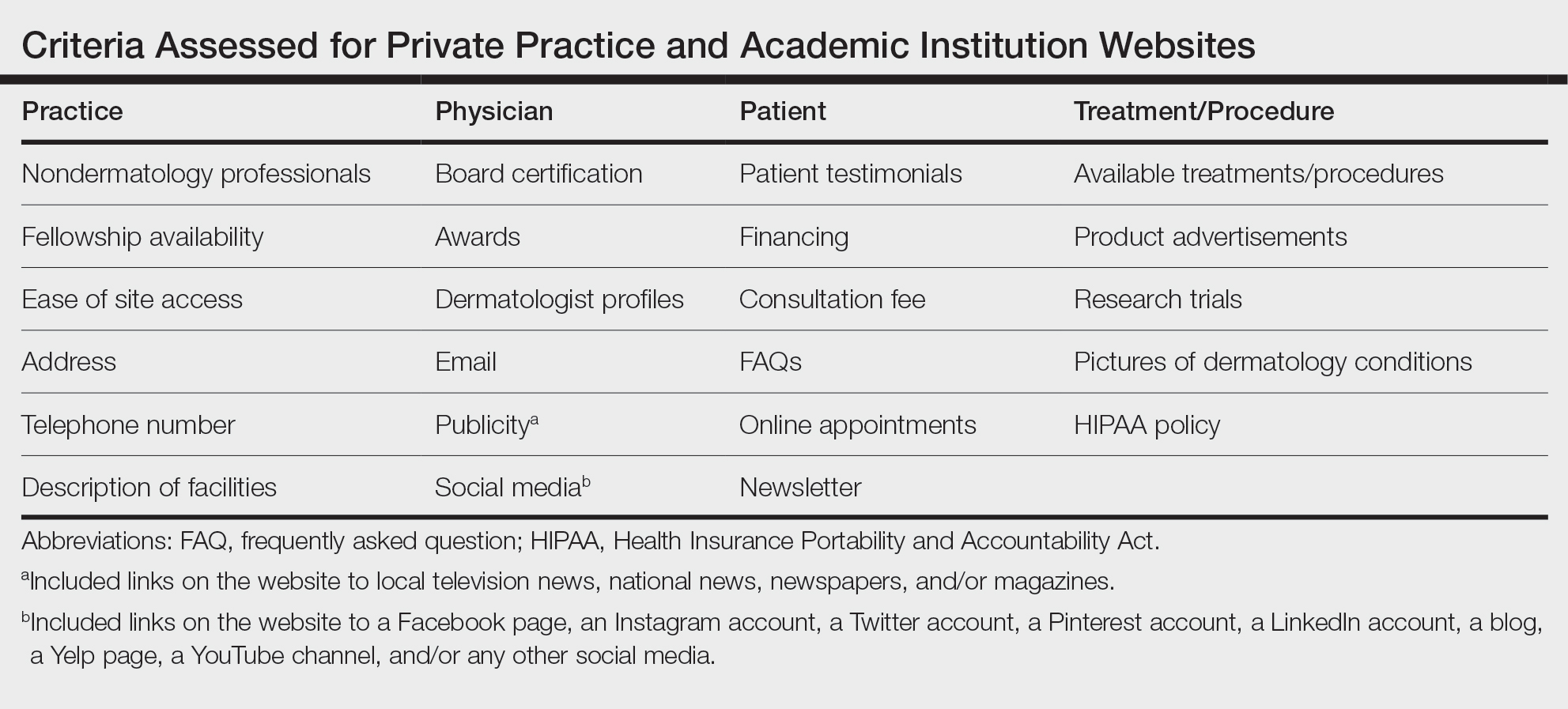

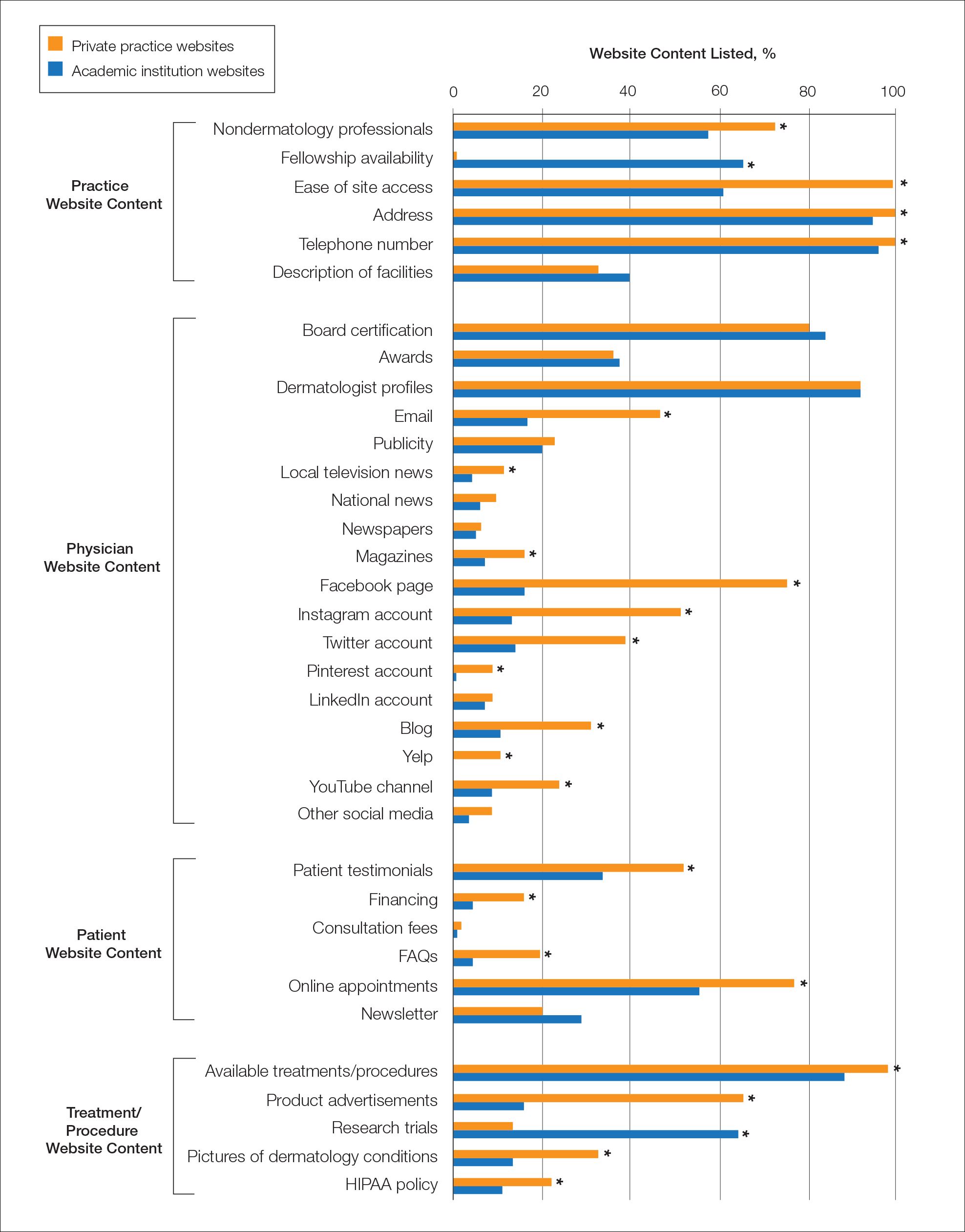

Website Assessments —Each website was assessed using 23 criteria divided into 4 categories: practice, physician(s), patient, and treatment/procedure (Table). Criteria for social media and publicity were further assessed. Criteria for social media included links on the website to a Facebook page, an Instagram account, a Twitter account, a Pinterest account, a LinkedIn account, a blog, a Yelp page, a YouTube channel, and/or any other social media. Criteria for publicity included links on the website to local television news, national news, newspapers, and/or magazines. 5-8 Ease of site access was determined if the website was the first search result found on Google when searching for each website. Nondermatology professionals included listing of mid-level providers or researchers.

Four individuals (V.S.J., A.C.B., M.E.O., and M.B.B.) independently assessed each of the websites using the established criteria. Each criterion was defined and discussed prior to data collection to maintain consistency. The criteria were determined as being present if the website clearly displayed, stated, explained, or linked to the relevant content. If the website did not directly contain the content, it was determined that the criteria were absent. One other individual (J.P.) independently cross-examined the data for consistency and evaluated for any discrepancies. 8

A raw analysis was done between each cohort. Another analysis was done that controlled for population density and the proportionate population age in each city 9 in which an academic institution/private practice was located. We proposed that more densely populated cities naturally may have more competition between practices, which may result in more optimized websites. 10 We also anticipated similar findings in cities with younger populations, as the younger demographic may be more likely to utilize and value online information when compared to older populations. 11 The websites for each cohort were equally divided into 3 tiers of population density (not shown) and population age (not shown).

Statistical Analysis —Statistical analysis was completed using descriptive statistics, χ 2 testing, and Fisher exact tests where appropriate with a predetermined level of significance of P < .05 in Microsoft Excel.

Results

Demographics —A total of 226 websites from both private practices and academic institutions were evaluated. Of them, only 108 private practices and 108 academic institutions listed practicing dermatologists on their site. Of 108 private practices, 76 (70.4%) had more than one practicing board-certified dermatologist. Of 108 academic institutions, all 108 (100%) institutions had more than one practicing board-certified dermatologist.

Of the dermatologists who practiced at academic institutions (n=2014) and private practices (n=817), 1157 (57.4%) and 419 (51.2%) were females, respectively. The population density of the cities with each of these practices/institutions ranged from 137 individuals per square kilometer to 11,232 individuals per square kilometer (mean [SD] population density, 2579 [2485] individuals per square kilometer). Densely populated, moderately populated, and sparsely populated cities had a median population density of 4618, 1708, and 760 individuals per square kilometer, respectively. The data also were divided into 3 age groups. In the older population tier, the median percentage of individuals older than 64 years was 14.2%, the median percentage of individuals aged 18 to 64 years was 63.8%, and the median percentage of individuals aged 5 to 17 years was 14.9%. In the moderately aged population tier, the median percentage of individuals older than 64 years was 10.2%, the median percentage of individuals aged 18 to 64 years was 70.3%, and the median percentage of individuals aged 5 to 17 years was 13.6%. In the younger population tier, the median percentage of individuals older than 64 years was 12%, the median percentage of individuals aged 18 to 64 years was 66.8%, and the median percentage of individuals aged 5 to 17 years was 15%.

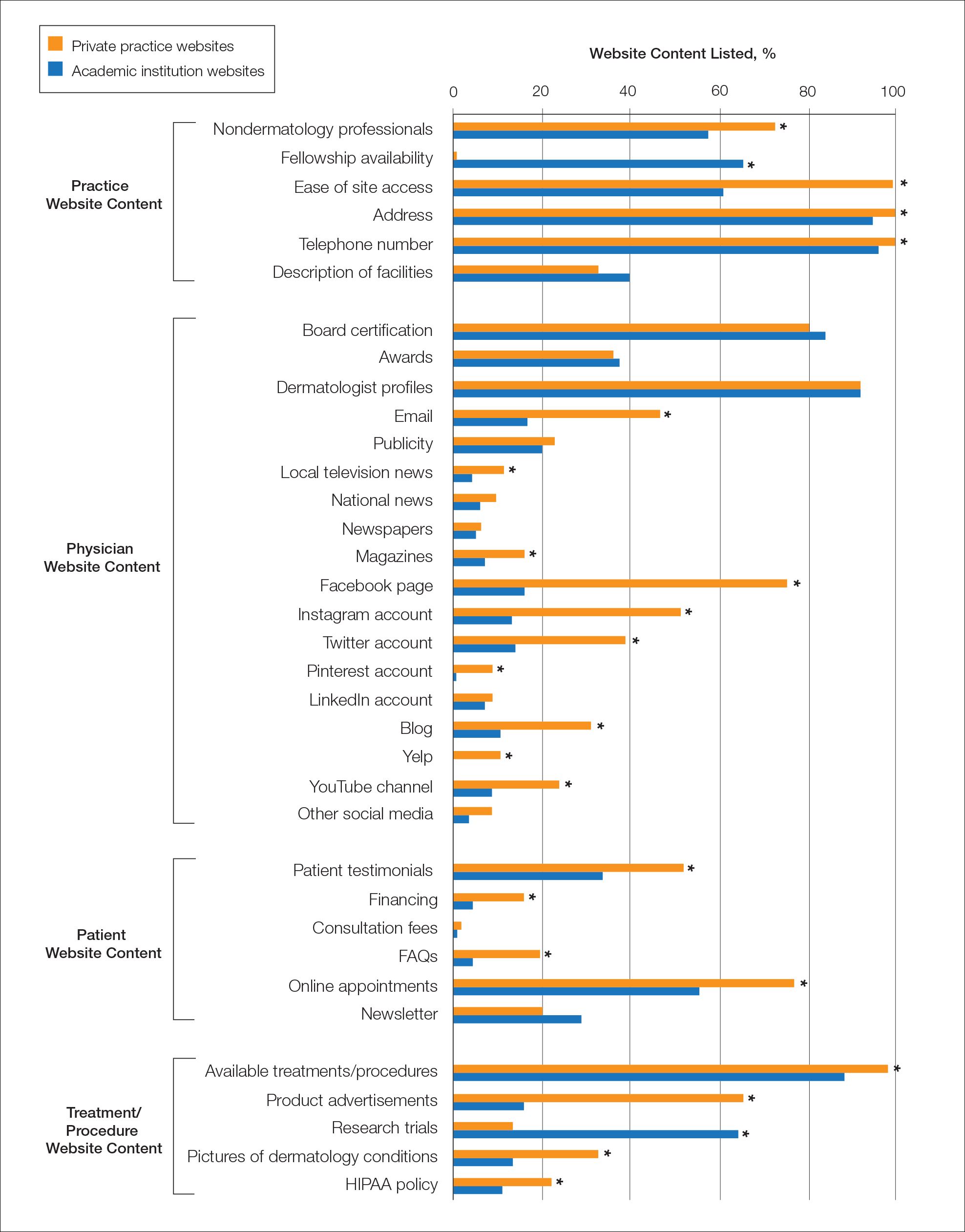

Practice and Physician Content—In the raw analysis (Figure), the most commonly listed types of content (>90% of websites) in both private practice and academic sites was address (range, 95% to 100%), telephone number (range, 97% to 100%), and dermatologist profiles (both 92%). The least commonly listed types of content in both cohorts was publicity (range, 20% to 23%). Private practices were more likely to list profiles of nondermatology professionals (73% vs 56%; P<.02), email (47% vs 17%; P<.0001), and social media (29% vs 8%; P<.0001) compared with academic institution websites. Although Facebook was the most-linked social media account for both groups, 75% of private practice sites included the link compared with 16% of academic institutions. Academic institutions were more likely to list fellowship availability (66% vs 1%; P<.0001). Accessing each website was significantly easier in the private practice cohort (99% vs 61%; P<.0001).

When controlling for population density, private practices were only more likely to list nondermatology professionals’ profiles in densely populated cities when compared with academic institutions (73% vs 41%; P<.01). Academic institutions continued to list fellowship availability more often than private practices regardless of population density. The same trend was observed for private practices with ease of site access and listing of social media.

When controlling for population age, similar trends were seen as when controlling for population density. However, private practices listing nondermatology professionals’ profiles was only more likely in the cities with a proportionately younger population when compared with academic institutions (74% vs 47%; P<.04).

Patient and Treatment/Procedure—The most commonly listed content types on both private practice websites and academic institution websites were available treatments/procedures (range, 89% to 98%). The least commonly listed content included financing for elective procedures (range, 4% to 16%), consultation fees (range, 1% to 2%), FAQs (frequently asked questions)(range, 4% to 20%), and HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) policy (range, 12% to 22%). Private practices were more likely to list patient testimonials (52% vs 35%; P<.005), financing (16% vs 4%; P<.005), FAQs (20% vs 4%; P<.001), online appointments (77% vs 56%; P<.001), available treatments/procedures (98% vs 86%; P<.004), product advertisements (66% vs 16%; P<.0001), pictures of dermatology conditions (33% vs 13%; P<.001), and HIPAA policy (22% vs 12%; P<.04). Academic institutions were more likely to list research trials (65% vs 13%; P<.0001).

When controlling for population density, private practices were only more likely to list patient testimonials in densely populated (P=.035) and moderately populated cities (P=.019). The same trend was observed for online appointments in densely populated (P=.0023) and moderately populated cities (P=.037). Private practices continued to list product availability more often than academic institutions regardless of population density or population age. Academic institutions also continued to list research trials more often than private practices regardless of population density or population age.

Comment

Our study uniquely analyzed the differences in website content between private practices and academic institutions in dermatology. Of the 140 academic institutions accredited by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), only 113 had patient-pertinent websites.

Access to Websites —There was a significant difference in many website content criteria between the 2 groups. Private practice sites were easier to access via a Google search when compared with academic sites, which likely is influenced by the Google search algorithm that ranks websites higher based on several criteria including but not limited to keyword use in the title tag, link popularity of the site, and historic ranking. 12,13 Academic sites often were only accessible through portals found on their main institutional site or institution’s residency site.

Role of Social Media —Social media has been found to assist in educating patients on medical practices as well as selecting a physician. 14,15 Our study found that private practice websites listed links to social media more often than their academic counterparts. Social media consumption is increasing, in part due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and it may be optimal for patients and practices alike to include links on their websites. 16 Facebook and Instagram were listed more often on private practice sites when compared with academic institution sites, which was similar to a recent study analyzing the websites of plastic surgery private practices (N = 310) in which 90% of private practices included some type of social media, with Instagram and Facebook being the most used. 8 Social networking accounts can act as convenient platforms for marketing, providing patient education, and generating referrals, which suggests that the prominence of their usage in private practice poses benefits in patient decision-making when seeking care. 17-19 A study analyzing the impact of Facebook in medicine concluded that a Facebook page can serve as an effective vehicle for medical education, particularly in younger generations that favor technology-oriented teaching methods. 20 A survey on trends in cosmetic facial procedures in plastic surgery found that the most influential online methods patients used for choosing their providers were social media platforms and practice websites. Front-page placement on Google also was commonly associated with the number of social media followers. 21,22 A lack of social media prominence could hinder a website’s potential to reach patients.

Communication With Practices —Our study also found significant differences in other metrics related to a patient’s ability to directly communicate with a practice, such as physical addresses, telephone numbers, products available for direct purchase, and online appointment booking, all of which were listed more often on private practice websites compared with academic institution websites. Online appointment booking also was found more frequently on private practice websites. Although physical addresses and telephone numbers were listed significantly more often on private practice sites, this information was ubiquitous and easily accessible elsewhere. Academic institution websites listed research trials and fellowship training significantly more often than private practices. These differences imply a divergence in focus between private practices and academic institutions, likely because academic institutions are funded in large part from research grants, begetting a cycle of academic contribution. 23 In contrast, private practices may not rely as heavily on academic revenue and may be more likely to prioritize other revenue streams such as product sales. 24

HIPAA Policy —Surprisingly, HIPAA policy rarely was listed on any private (22%) or academic site (12%). Conversely, in the plastic surgery study, HIPAA policy was listed much more often, with more than half of private practices with board-certified plastic surgeons accredited in the year 2015 including it on their website, 8 which may suggest that surgically oriented specialties, particularly cosmetic subspecialties, aim to more noticeably display their privacy policies for patient reassurance.

Study Limitations —There are several limitations of our study. First, it is common for a conglomerate company to own multiple private practices in different specialties. As with academic sites, private practice sites may be limited by the hosting platforms, which often are tedious to navigate. Also noteworthy is the emergence of designated social media management positions—both by practice employees and by third-party firms 25 —but the impact of these positions in private practices and academic institutions has not been fully explored. Finally, inclusion criteria and standardized criteria definitions were chosen based on the precedent established by the authors of similar analyses in plastic surgery and radiology. 5-8 Further investigation into the most valued aspects of care by patients within the context of the type of practice chosen would be valuable in refining inclusion criteria. Additionally, this study did not stratify the data collected based on factors such as gender, race, and geographical location; studies conducted on website traffic analysis patterns that focus on these aspects likely would further explain the significance of these findings. Differences in the length of time to the next available appointment between private practices and academic institutions also may help support our findings. Finally, there is a need for further investigation into the preferences of patients themselves garnered from website traffic alone.

Conclusion

Our study examined a diverse compilation of private practice and academic institution websites and uncovered numerous differences in content. As technology and health care continuously evolve, it is imperative that both private practices and academic institutions are actively adapting to optimize their online presence. In doing so, patients will be better equipped at accessing provider information, gaining familiarity with the practice, and understanding treatment options.

- Gentry ZL, Ananthasekar S, Yeatts M, et al. Can patients find an endocrine surgeon? how hospital websites hide the expertise of these medical professionals. Am J Surg . 2021;221:101-105.

- Pollack CE, Rastegar A, Keating NL, et al. Is self-referral associated with higher quality care? Health Serv Res . 2015;50:1472-1490.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Residency Explorer TM tool. Accessed May 15, 2023. https://students-residents.aamc.org/apply-smart-residency/residency-explorer-tool

- Find a dermatologist. American Academy of Dermatology website. Accessed May 15, 2023. https://find-a-derm.aad.org/

- Johnson EJ, Doshi AM, Rosenkrantz AB. Strengths and deficiencies in the content of US radiology private practices’ websites. J Am Coll Radiol. 2017;14:431-435.

- Brunk D. Medical website expert shares design tips. Dermatology News . February 9, 2012. Accessed May 15, 2023. https://www.mdedge.com/dermatology/article/47413/health-policy/medical-website-expert-shares-design-tips

- Kuhnigk O, Ramuschkat M, Schreiner J, et al. Internet presence of neurologists, psychiatrists and medical psychotherapists in private practice [in German]. Psychiatr Prax . 2013;41:142-147.

- Ananthasekar S, Patel JJ, Patel NJ, et al. The content of US plastic surgery private practices’ websites. Ann Plast Surg . 2021;86(6S suppl 5):S578-S584.

- US Census Bureau. Age and Sex: 2021. Updated December 2, 2021. Accessed March 15, 2023. https://www.census.gov/topics/population/age-and-sex/data/tables.2021.List_897222059.html#list-tab-List_897222059

- Porter ME. The competitive advantage of the inner city. Harvard Business Review . Published August 1, 2014. https://hbr.org/1995/05/the-competitive-advantage-of-the-inner-city

- Clark PG. The social allocation of health care resources: ethical dilemmas in age-group competition. Gerontologist. 1985;25:119-125.

- Su A-J, Hu YC, Kuzmanovic A, et al. How to improve your Google ranking: myths and reality. ACM Transactions on the Web . 2014;8. https://dl.acm.org/doi/abs/10.1145/2579990

- McCormick K. 39 ways to increase traffic to your website. WordStream website. Published March 28, 2023. Accessed May 22, 2023. https://www.wordstream.com/blog/ws/2014/08/14/increase-traffic-to-my-website

- Montemurro P, Porcnik A, Hedén P, et al. The influence of social media and easily accessible online information on the aesthetic plastic surgery practice: literature review and our own experience. Aesthetic Plast Surg . 2015;39:270-277.

- Steehler KR, Steehler MK, Pierce ML, et al. Social media’s role in otolaryngology–head and neck surgery. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg . 2013;149:521-524.

- Tsao S-F, Chen H, Tisseverasinghe T, et al. What social media told us in the time of COVID-19: a scoping review. Lancet Digit Health . 2021;3:E175-E194.

- Geist R, Militello M, Albrecht JM, et al. Social media and clinical research in dermatology. Curr Dermatol Rep . 2021;10:105-111.

- McLawhorn AS, De Martino I, Fehring KA, et al. Social media and your practice: navigating the surgeon-patient relationship. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med . 2016;9:487-495.

- Thomas RB, Johnson PT, Fishman EK. Social media for global education: pearls and pitfalls of using Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. J Am Coll Radiol . 2018;15:1513-1516.

- Lugo-Fagundo C, Johnson MB, Thomas RB, et al. New frontiers in education: Facebook as a vehicle for medical information delivery. J Am Coll Radiol . 2016;13:316-319.

- Ho T-VT, Dayan SH. How to leverage social media in private practice. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am . 2020;28:515-522.

- Fan KL, Graziano F, Economides JM, et al. The public’s preferences on plastic surgery social media engagement and professionalism. Plast Reconstr Surg . 2019;143:619-630.

- Jacob BA, Lefgren L. The impact of research grant funding on scientific productivity. J Public Econ. 2011;95:1168-1177.

- Baumann L. Ethics in cosmetic dermatology. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:522-527.

- Miller AR, Tucker C. Active social media management: the case of health care. Info Sys Res . 2013;24:52-70.

Patients are finding it easier to use online resources to discover health care providers who fit their personalized needs. In the United States, approximately 70% of individuals use the internet to find health care information, and 80% are influenced by the information presented to them on health care websites.1 Patients utilize the internet to better understand treatments offered by providers and their prices as well as how other patients have rated their experience. Providers in private practice also have noticed that many patients are referring themselves vs obtaining a referral from another provider.2 As a result, it is critical for practice websites to have information that is of value to their patients, including the unique qualities and treatments offered. The purpose of this study was to analyze the differences between the content presented on dermatology private practice websites and academic institutional websites.

Methods

Websites Searched —All 140 academic dermatology programs, including both allopathic and osteopathic programs, were queried from the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) database in March 2022. 3 First, the dermatology departmental websites for each program were analyzed to see if they contained information pertinent to patients. Any website that lacked this information or only had information relevant to the dermatology residency program was excluded from the study. After exclusion, a total of 113 websites were used in the academic website cohort. The private practices were found through an incognito Google search with the search term dermatologist and matched to be within 5 miles of each academic institution. The private practices that included at least one board-certified dermatologist and received the highest number of reviews on Google compared to other practices in the same region—a measure of online reputation—were selected to be in the private practice cohort (N = 113). Any duplicate practices, practices belonging to the same conglomerate company, or multispecialty clinics were excluded from the study. Board-certified dermatologists were confirmed using the Find a Dermatologist tool on the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) website. 4

Website Assessments —Each website was assessed using 23 criteria divided into 4 categories: practice, physician(s), patient, and treatment/procedure (Table). Criteria for social media and publicity were further assessed. Criteria for social media included links on the website to a Facebook page, an Instagram account, a Twitter account, a Pinterest account, a LinkedIn account, a blog, a Yelp page, a YouTube channel, and/or any other social media. Criteria for publicity included links on the website to local television news, national news, newspapers, and/or magazines. 5-8 Ease of site access was determined if the website was the first search result found on Google when searching for each website. Nondermatology professionals included listing of mid-level providers or researchers.

Four individuals (V.S.J., A.C.B., M.E.O., and M.B.B.) independently assessed each of the websites using the established criteria. Each criterion was defined and discussed prior to data collection to maintain consistency. The criteria were determined as being present if the website clearly displayed, stated, explained, or linked to the relevant content. If the website did not directly contain the content, it was determined that the criteria were absent. One other individual (J.P.) independently cross-examined the data for consistency and evaluated for any discrepancies. 8

A raw analysis was done between each cohort. Another analysis was done that controlled for population density and the proportionate population age in each city 9 in which an academic institution/private practice was located. We proposed that more densely populated cities naturally may have more competition between practices, which may result in more optimized websites. 10 We also anticipated similar findings in cities with younger populations, as the younger demographic may be more likely to utilize and value online information when compared to older populations. 11 The websites for each cohort were equally divided into 3 tiers of population density (not shown) and population age (not shown).

Statistical Analysis —Statistical analysis was completed using descriptive statistics, χ 2 testing, and Fisher exact tests where appropriate with a predetermined level of significance of P < .05 in Microsoft Excel.

Results

Demographics —A total of 226 websites from both private practices and academic institutions were evaluated. Of them, only 108 private practices and 108 academic institutions listed practicing dermatologists on their site. Of 108 private practices, 76 (70.4%) had more than one practicing board-certified dermatologist. Of 108 academic institutions, all 108 (100%) institutions had more than one practicing board-certified dermatologist.

Of the dermatologists who practiced at academic institutions (n=2014) and private practices (n=817), 1157 (57.4%) and 419 (51.2%) were females, respectively. The population density of the cities with each of these practices/institutions ranged from 137 individuals per square kilometer to 11,232 individuals per square kilometer (mean [SD] population density, 2579 [2485] individuals per square kilometer). Densely populated, moderately populated, and sparsely populated cities had a median population density of 4618, 1708, and 760 individuals per square kilometer, respectively. The data also were divided into 3 age groups. In the older population tier, the median percentage of individuals older than 64 years was 14.2%, the median percentage of individuals aged 18 to 64 years was 63.8%, and the median percentage of individuals aged 5 to 17 years was 14.9%. In the moderately aged population tier, the median percentage of individuals older than 64 years was 10.2%, the median percentage of individuals aged 18 to 64 years was 70.3%, and the median percentage of individuals aged 5 to 17 years was 13.6%. In the younger population tier, the median percentage of individuals older than 64 years was 12%, the median percentage of individuals aged 18 to 64 years was 66.8%, and the median percentage of individuals aged 5 to 17 years was 15%.

Practice and Physician Content—In the raw analysis (Figure), the most commonly listed types of content (>90% of websites) in both private practice and academic sites was address (range, 95% to 100%), telephone number (range, 97% to 100%), and dermatologist profiles (both 92%). The least commonly listed types of content in both cohorts was publicity (range, 20% to 23%). Private practices were more likely to list profiles of nondermatology professionals (73% vs 56%; P<.02), email (47% vs 17%; P<.0001), and social media (29% vs 8%; P<.0001) compared with academic institution websites. Although Facebook was the most-linked social media account for both groups, 75% of private practice sites included the link compared with 16% of academic institutions. Academic institutions were more likely to list fellowship availability (66% vs 1%; P<.0001). Accessing each website was significantly easier in the private practice cohort (99% vs 61%; P<.0001).

When controlling for population density, private practices were only more likely to list nondermatology professionals’ profiles in densely populated cities when compared with academic institutions (73% vs 41%; P<.01). Academic institutions continued to list fellowship availability more often than private practices regardless of population density. The same trend was observed for private practices with ease of site access and listing of social media.

When controlling for population age, similar trends were seen as when controlling for population density. However, private practices listing nondermatology professionals’ profiles was only more likely in the cities with a proportionately younger population when compared with academic institutions (74% vs 47%; P<.04).

Patient and Treatment/Procedure—The most commonly listed content types on both private practice websites and academic institution websites were available treatments/procedures (range, 89% to 98%). The least commonly listed content included financing for elective procedures (range, 4% to 16%), consultation fees (range, 1% to 2%), FAQs (frequently asked questions)(range, 4% to 20%), and HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) policy (range, 12% to 22%). Private practices were more likely to list patient testimonials (52% vs 35%; P<.005), financing (16% vs 4%; P<.005), FAQs (20% vs 4%; P<.001), online appointments (77% vs 56%; P<.001), available treatments/procedures (98% vs 86%; P<.004), product advertisements (66% vs 16%; P<.0001), pictures of dermatology conditions (33% vs 13%; P<.001), and HIPAA policy (22% vs 12%; P<.04). Academic institutions were more likely to list research trials (65% vs 13%; P<.0001).

When controlling for population density, private practices were only more likely to list patient testimonials in densely populated (P=.035) and moderately populated cities (P=.019). The same trend was observed for online appointments in densely populated (P=.0023) and moderately populated cities (P=.037). Private practices continued to list product availability more often than academic institutions regardless of population density or population age. Academic institutions also continued to list research trials more often than private practices regardless of population density or population age.

Comment

Our study uniquely analyzed the differences in website content between private practices and academic institutions in dermatology. Of the 140 academic institutions accredited by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), only 113 had patient-pertinent websites.

Access to Websites —There was a significant difference in many website content criteria between the 2 groups. Private practice sites were easier to access via a Google search when compared with academic sites, which likely is influenced by the Google search algorithm that ranks websites higher based on several criteria including but not limited to keyword use in the title tag, link popularity of the site, and historic ranking. 12,13 Academic sites often were only accessible through portals found on their main institutional site or institution’s residency site.

Role of Social Media —Social media has been found to assist in educating patients on medical practices as well as selecting a physician. 14,15 Our study found that private practice websites listed links to social media more often than their academic counterparts. Social media consumption is increasing, in part due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and it may be optimal for patients and practices alike to include links on their websites. 16 Facebook and Instagram were listed more often on private practice sites when compared with academic institution sites, which was similar to a recent study analyzing the websites of plastic surgery private practices (N = 310) in which 90% of private practices included some type of social media, with Instagram and Facebook being the most used. 8 Social networking accounts can act as convenient platforms for marketing, providing patient education, and generating referrals, which suggests that the prominence of their usage in private practice poses benefits in patient decision-making when seeking care. 17-19 A study analyzing the impact of Facebook in medicine concluded that a Facebook page can serve as an effective vehicle for medical education, particularly in younger generations that favor technology-oriented teaching methods. 20 A survey on trends in cosmetic facial procedures in plastic surgery found that the most influential online methods patients used for choosing their providers were social media platforms and practice websites. Front-page placement on Google also was commonly associated with the number of social media followers. 21,22 A lack of social media prominence could hinder a website’s potential to reach patients.

Communication With Practices —Our study also found significant differences in other metrics related to a patient’s ability to directly communicate with a practice, such as physical addresses, telephone numbers, products available for direct purchase, and online appointment booking, all of which were listed more often on private practice websites compared with academic institution websites. Online appointment booking also was found more frequently on private practice websites. Although physical addresses and telephone numbers were listed significantly more often on private practice sites, this information was ubiquitous and easily accessible elsewhere. Academic institution websites listed research trials and fellowship training significantly more often than private practices. These differences imply a divergence in focus between private practices and academic institutions, likely because academic institutions are funded in large part from research grants, begetting a cycle of academic contribution. 23 In contrast, private practices may not rely as heavily on academic revenue and may be more likely to prioritize other revenue streams such as product sales. 24

HIPAA Policy —Surprisingly, HIPAA policy rarely was listed on any private (22%) or academic site (12%). Conversely, in the plastic surgery study, HIPAA policy was listed much more often, with more than half of private practices with board-certified plastic surgeons accredited in the year 2015 including it on their website, 8 which may suggest that surgically oriented specialties, particularly cosmetic subspecialties, aim to more noticeably display their privacy policies for patient reassurance.

Study Limitations —There are several limitations of our study. First, it is common for a conglomerate company to own multiple private practices in different specialties. As with academic sites, private practice sites may be limited by the hosting platforms, which often are tedious to navigate. Also noteworthy is the emergence of designated social media management positions—both by practice employees and by third-party firms 25 —but the impact of these positions in private practices and academic institutions has not been fully explored. Finally, inclusion criteria and standardized criteria definitions were chosen based on the precedent established by the authors of similar analyses in plastic surgery and radiology. 5-8 Further investigation into the most valued aspects of care by patients within the context of the type of practice chosen would be valuable in refining inclusion criteria. Additionally, this study did not stratify the data collected based on factors such as gender, race, and geographical location; studies conducted on website traffic analysis patterns that focus on these aspects likely would further explain the significance of these findings. Differences in the length of time to the next available appointment between private practices and academic institutions also may help support our findings. Finally, there is a need for further investigation into the preferences of patients themselves garnered from website traffic alone.

Conclusion

Our study examined a diverse compilation of private practice and academic institution websites and uncovered numerous differences in content. As technology and health care continuously evolve, it is imperative that both private practices and academic institutions are actively adapting to optimize their online presence. In doing so, patients will be better equipped at accessing provider information, gaining familiarity with the practice, and understanding treatment options.

Patients are finding it easier to use online resources to discover health care providers who fit their personalized needs. In the United States, approximately 70% of individuals use the internet to find health care information, and 80% are influenced by the information presented to them on health care websites.1 Patients utilize the internet to better understand treatments offered by providers and their prices as well as how other patients have rated their experience. Providers in private practice also have noticed that many patients are referring themselves vs obtaining a referral from another provider.2 As a result, it is critical for practice websites to have information that is of value to their patients, including the unique qualities and treatments offered. The purpose of this study was to analyze the differences between the content presented on dermatology private practice websites and academic institutional websites.

Methods

Websites Searched —All 140 academic dermatology programs, including both allopathic and osteopathic programs, were queried from the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) database in March 2022. 3 First, the dermatology departmental websites for each program were analyzed to see if they contained information pertinent to patients. Any website that lacked this information or only had information relevant to the dermatology residency program was excluded from the study. After exclusion, a total of 113 websites were used in the academic website cohort. The private practices were found through an incognito Google search with the search term dermatologist and matched to be within 5 miles of each academic institution. The private practices that included at least one board-certified dermatologist and received the highest number of reviews on Google compared to other practices in the same region—a measure of online reputation—were selected to be in the private practice cohort (N = 113). Any duplicate practices, practices belonging to the same conglomerate company, or multispecialty clinics were excluded from the study. Board-certified dermatologists were confirmed using the Find a Dermatologist tool on the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) website. 4

Website Assessments —Each website was assessed using 23 criteria divided into 4 categories: practice, physician(s), patient, and treatment/procedure (Table). Criteria for social media and publicity were further assessed. Criteria for social media included links on the website to a Facebook page, an Instagram account, a Twitter account, a Pinterest account, a LinkedIn account, a blog, a Yelp page, a YouTube channel, and/or any other social media. Criteria for publicity included links on the website to local television news, national news, newspapers, and/or magazines. 5-8 Ease of site access was determined if the website was the first search result found on Google when searching for each website. Nondermatology professionals included listing of mid-level providers or researchers.

Four individuals (V.S.J., A.C.B., M.E.O., and M.B.B.) independently assessed each of the websites using the established criteria. Each criterion was defined and discussed prior to data collection to maintain consistency. The criteria were determined as being present if the website clearly displayed, stated, explained, or linked to the relevant content. If the website did not directly contain the content, it was determined that the criteria were absent. One other individual (J.P.) independently cross-examined the data for consistency and evaluated for any discrepancies. 8

A raw analysis was done between each cohort. Another analysis was done that controlled for population density and the proportionate population age in each city 9 in which an academic institution/private practice was located. We proposed that more densely populated cities naturally may have more competition between practices, which may result in more optimized websites. 10 We also anticipated similar findings in cities with younger populations, as the younger demographic may be more likely to utilize and value online information when compared to older populations. 11 The websites for each cohort were equally divided into 3 tiers of population density (not shown) and population age (not shown).

Statistical Analysis —Statistical analysis was completed using descriptive statistics, χ 2 testing, and Fisher exact tests where appropriate with a predetermined level of significance of P < .05 in Microsoft Excel.

Results

Demographics —A total of 226 websites from both private practices and academic institutions were evaluated. Of them, only 108 private practices and 108 academic institutions listed practicing dermatologists on their site. Of 108 private practices, 76 (70.4%) had more than one practicing board-certified dermatologist. Of 108 academic institutions, all 108 (100%) institutions had more than one practicing board-certified dermatologist.

Of the dermatologists who practiced at academic institutions (n=2014) and private practices (n=817), 1157 (57.4%) and 419 (51.2%) were females, respectively. The population density of the cities with each of these practices/institutions ranged from 137 individuals per square kilometer to 11,232 individuals per square kilometer (mean [SD] population density, 2579 [2485] individuals per square kilometer). Densely populated, moderately populated, and sparsely populated cities had a median population density of 4618, 1708, and 760 individuals per square kilometer, respectively. The data also were divided into 3 age groups. In the older population tier, the median percentage of individuals older than 64 years was 14.2%, the median percentage of individuals aged 18 to 64 years was 63.8%, and the median percentage of individuals aged 5 to 17 years was 14.9%. In the moderately aged population tier, the median percentage of individuals older than 64 years was 10.2%, the median percentage of individuals aged 18 to 64 years was 70.3%, and the median percentage of individuals aged 5 to 17 years was 13.6%. In the younger population tier, the median percentage of individuals older than 64 years was 12%, the median percentage of individuals aged 18 to 64 years was 66.8%, and the median percentage of individuals aged 5 to 17 years was 15%.

Practice and Physician Content—In the raw analysis (Figure), the most commonly listed types of content (>90% of websites) in both private practice and academic sites was address (range, 95% to 100%), telephone number (range, 97% to 100%), and dermatologist profiles (both 92%). The least commonly listed types of content in both cohorts was publicity (range, 20% to 23%). Private practices were more likely to list profiles of nondermatology professionals (73% vs 56%; P<.02), email (47% vs 17%; P<.0001), and social media (29% vs 8%; P<.0001) compared with academic institution websites. Although Facebook was the most-linked social media account for both groups, 75% of private practice sites included the link compared with 16% of academic institutions. Academic institutions were more likely to list fellowship availability (66% vs 1%; P<.0001). Accessing each website was significantly easier in the private practice cohort (99% vs 61%; P<.0001).

When controlling for population density, private practices were only more likely to list nondermatology professionals’ profiles in densely populated cities when compared with academic institutions (73% vs 41%; P<.01). Academic institutions continued to list fellowship availability more often than private practices regardless of population density. The same trend was observed for private practices with ease of site access and listing of social media.

When controlling for population age, similar trends were seen as when controlling for population density. However, private practices listing nondermatology professionals’ profiles was only more likely in the cities with a proportionately younger population when compared with academic institutions (74% vs 47%; P<.04).

Patient and Treatment/Procedure—The most commonly listed content types on both private practice websites and academic institution websites were available treatments/procedures (range, 89% to 98%). The least commonly listed content included financing for elective procedures (range, 4% to 16%), consultation fees (range, 1% to 2%), FAQs (frequently asked questions)(range, 4% to 20%), and HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) policy (range, 12% to 22%). Private practices were more likely to list patient testimonials (52% vs 35%; P<.005), financing (16% vs 4%; P<.005), FAQs (20% vs 4%; P<.001), online appointments (77% vs 56%; P<.001), available treatments/procedures (98% vs 86%; P<.004), product advertisements (66% vs 16%; P<.0001), pictures of dermatology conditions (33% vs 13%; P<.001), and HIPAA policy (22% vs 12%; P<.04). Academic institutions were more likely to list research trials (65% vs 13%; P<.0001).

When controlling for population density, private practices were only more likely to list patient testimonials in densely populated (P=.035) and moderately populated cities (P=.019). The same trend was observed for online appointments in densely populated (P=.0023) and moderately populated cities (P=.037). Private practices continued to list product availability more often than academic institutions regardless of population density or population age. Academic institutions also continued to list research trials more often than private practices regardless of population density or population age.

Comment

Our study uniquely analyzed the differences in website content between private practices and academic institutions in dermatology. Of the 140 academic institutions accredited by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), only 113 had patient-pertinent websites.

Access to Websites —There was a significant difference in many website content criteria between the 2 groups. Private practice sites were easier to access via a Google search when compared with academic sites, which likely is influenced by the Google search algorithm that ranks websites higher based on several criteria including but not limited to keyword use in the title tag, link popularity of the site, and historic ranking. 12,13 Academic sites often were only accessible through portals found on their main institutional site or institution’s residency site.

Role of Social Media —Social media has been found to assist in educating patients on medical practices as well as selecting a physician. 14,15 Our study found that private practice websites listed links to social media more often than their academic counterparts. Social media consumption is increasing, in part due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and it may be optimal for patients and practices alike to include links on their websites. 16 Facebook and Instagram were listed more often on private practice sites when compared with academic institution sites, which was similar to a recent study analyzing the websites of plastic surgery private practices (N = 310) in which 90% of private practices included some type of social media, with Instagram and Facebook being the most used. 8 Social networking accounts can act as convenient platforms for marketing, providing patient education, and generating referrals, which suggests that the prominence of their usage in private practice poses benefits in patient decision-making when seeking care. 17-19 A study analyzing the impact of Facebook in medicine concluded that a Facebook page can serve as an effective vehicle for medical education, particularly in younger generations that favor technology-oriented teaching methods. 20 A survey on trends in cosmetic facial procedures in plastic surgery found that the most influential online methods patients used for choosing their providers were social media platforms and practice websites. Front-page placement on Google also was commonly associated with the number of social media followers. 21,22 A lack of social media prominence could hinder a website’s potential to reach patients.

Communication With Practices —Our study also found significant differences in other metrics related to a patient’s ability to directly communicate with a practice, such as physical addresses, telephone numbers, products available for direct purchase, and online appointment booking, all of which were listed more often on private practice websites compared with academic institution websites. Online appointment booking also was found more frequently on private practice websites. Although physical addresses and telephone numbers were listed significantly more often on private practice sites, this information was ubiquitous and easily accessible elsewhere. Academic institution websites listed research trials and fellowship training significantly more often than private practices. These differences imply a divergence in focus between private practices and academic institutions, likely because academic institutions are funded in large part from research grants, begetting a cycle of academic contribution. 23 In contrast, private practices may not rely as heavily on academic revenue and may be more likely to prioritize other revenue streams such as product sales. 24

HIPAA Policy —Surprisingly, HIPAA policy rarely was listed on any private (22%) or academic site (12%). Conversely, in the plastic surgery study, HIPAA policy was listed much more often, with more than half of private practices with board-certified plastic surgeons accredited in the year 2015 including it on their website, 8 which may suggest that surgically oriented specialties, particularly cosmetic subspecialties, aim to more noticeably display their privacy policies for patient reassurance.

Study Limitations —There are several limitations of our study. First, it is common for a conglomerate company to own multiple private practices in different specialties. As with academic sites, private practice sites may be limited by the hosting platforms, which often are tedious to navigate. Also noteworthy is the emergence of designated social media management positions—both by practice employees and by third-party firms 25 —but the impact of these positions in private practices and academic institutions has not been fully explored. Finally, inclusion criteria and standardized criteria definitions were chosen based on the precedent established by the authors of similar analyses in plastic surgery and radiology. 5-8 Further investigation into the most valued aspects of care by patients within the context of the type of practice chosen would be valuable in refining inclusion criteria. Additionally, this study did not stratify the data collected based on factors such as gender, race, and geographical location; studies conducted on website traffic analysis patterns that focus on these aspects likely would further explain the significance of these findings. Differences in the length of time to the next available appointment between private practices and academic institutions also may help support our findings. Finally, there is a need for further investigation into the preferences of patients themselves garnered from website traffic alone.

Conclusion

Our study examined a diverse compilation of private practice and academic institution websites and uncovered numerous differences in content. As technology and health care continuously evolve, it is imperative that both private practices and academic institutions are actively adapting to optimize their online presence. In doing so, patients will be better equipped at accessing provider information, gaining familiarity with the practice, and understanding treatment options.

- Gentry ZL, Ananthasekar S, Yeatts M, et al. Can patients find an endocrine surgeon? how hospital websites hide the expertise of these medical professionals. Am J Surg . 2021;221:101-105.

- Pollack CE, Rastegar A, Keating NL, et al. Is self-referral associated with higher quality care? Health Serv Res . 2015;50:1472-1490.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Residency Explorer TM tool. Accessed May 15, 2023. https://students-residents.aamc.org/apply-smart-residency/residency-explorer-tool

- Find a dermatologist. American Academy of Dermatology website. Accessed May 15, 2023. https://find-a-derm.aad.org/

- Johnson EJ, Doshi AM, Rosenkrantz AB. Strengths and deficiencies in the content of US radiology private practices’ websites. J Am Coll Radiol. 2017;14:431-435.

- Brunk D. Medical website expert shares design tips. Dermatology News . February 9, 2012. Accessed May 15, 2023. https://www.mdedge.com/dermatology/article/47413/health-policy/medical-website-expert-shares-design-tips

- Kuhnigk O, Ramuschkat M, Schreiner J, et al. Internet presence of neurologists, psychiatrists and medical psychotherapists in private practice [in German]. Psychiatr Prax . 2013;41:142-147.

- Ananthasekar S, Patel JJ, Patel NJ, et al. The content of US plastic surgery private practices’ websites. Ann Plast Surg . 2021;86(6S suppl 5):S578-S584.

- US Census Bureau. Age and Sex: 2021. Updated December 2, 2021. Accessed March 15, 2023. https://www.census.gov/topics/population/age-and-sex/data/tables.2021.List_897222059.html#list-tab-List_897222059

- Porter ME. The competitive advantage of the inner city. Harvard Business Review . Published August 1, 2014. https://hbr.org/1995/05/the-competitive-advantage-of-the-inner-city

- Clark PG. The social allocation of health care resources: ethical dilemmas in age-group competition. Gerontologist. 1985;25:119-125.

- Su A-J, Hu YC, Kuzmanovic A, et al. How to improve your Google ranking: myths and reality. ACM Transactions on the Web . 2014;8. https://dl.acm.org/doi/abs/10.1145/2579990

- McCormick K. 39 ways to increase traffic to your website. WordStream website. Published March 28, 2023. Accessed May 22, 2023. https://www.wordstream.com/blog/ws/2014/08/14/increase-traffic-to-my-website

- Montemurro P, Porcnik A, Hedén P, et al. The influence of social media and easily accessible online information on the aesthetic plastic surgery practice: literature review and our own experience. Aesthetic Plast Surg . 2015;39:270-277.