User login

Surgeon in the C-suite

“If you don’t have a seat at the table, you are probably on the menu.” I first heard this quote in 2013, and it launched my interest in health care leadership and influenced me countless times over the last 10 years.

As Chief of Staff at Cleveland Clinic, I oversee nearly 5,000 physicians and scientists across the globe. I am involved in the physician life cycle: recruiting, hiring, privileging and credentialing, talent development, promotion, professionalism, and career transitions. I also sit at the intersection of medical care and the business of medicine. This means leading 18 clinical service lines responsible for 5.6 million visits, 161,000 surgeries, and billions of dollars in operating revenue per year. How I spend most of my time is a far cry from what I spent 11 years’ training to do—gynecologic surgery. This shift in my career was not because I changed my mind about caring for patients or that I tired of being a full-time surgeon. Nothing could be further from the truth. Women’s health remains my “why,” and my leadership journey has taught me that it is critical to have a seat at the table for the sake of ObGyns and women everywhere.

Women’s health on the menu

I will start with a concrete example of when we, as women and ObGyns, were on the menu. In late 2019, the Ohio state House of Representatives introduced a bill that subjected doctors to potential murder charges if they did not try everything to save the life of a mother and fetus, “including attempting to reimplant an ectopic pregnancy into the woman’s uterus.”1 This bill was based on 2 case reports—one from 1915 and one from 1980—which were both low quality, and the latter case was deemed to be fraudulent.2 How did this happen?

An Ohio state representative developed the bill with help from a lobbyist and without input from physicians or content experts. When asked, the representative shared that “he never researched whether re-implanting an ectopic pregnancy into a woman’s uterus was a viable medical procedure before including it in the bill.”3 He added, “I heard about it over the years. I never questioned it or gave it a lot of thought.”3

This example resonates deeply with many of us; it inspires us to speak up and act. As ObGyns, we clearly understand the consequences of legal and regulatory change in women’s health and how it directly impacts our patients and each of us as physicians. Let’s shift to something that you may feel less passion about, but I believe is equally important. This is where obstetrician-gynecologists sit in the intersection of medical care and business. This is the space where I spend most of my time, and from this vantage point, I worry about our field.

The business of medicine

Starting at the macroeconomic level, let’s think about how we as physicians are reimbursed and who makes these decisions. Looking at the national health care expenditure data, Medicare and Medicaid spending makes up nearly 40% of the total spend, and it is growing.4 Additionally, private health insurance tends to follow Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) decision making, further compounding its influence.4 In simple terms, CMS decides what is covered and how much we are paid. Whether you are in a solo private practice, an employer health care organization, or an academic medical center, physician reimbursement is declining.

In fact, Congress passed its year-end omnibus legislation in the final days of 2022, including a 2% Medicare physician payment cut for 2023,5 at a time when expenses to practice medicine, including nonphysician staff and supplies, are at an all-time high and we are living in a 6% inflationary state. This translates into being asked to serve more patients and cut costs. Our day-to-day feels much tighter, and this is why: Medicare physician pay increased just 11% over the past 20 years6 (2001–2021) in comparison to the cost of running a medical practice, which increased nearly 40% during that time. In other words, adjusting for inflation in practice costs, Medicare physician payment has fallen 22% over the last 20 years.7

Depending on your employment model, you may feel insulated from these changes as increases in reimbursement have occurred in other areas, such as hospitals and ambulatory surgery centers.8 In the short term, these increases help, as organizations will see additional funds. But there are 2 main issues: First, it is not nearly enough when you consider the soaring costs of running a hospital. And second, looking at our national population, we rely tremendously on self-employed doctors to serve our patients.

More than 80% of US counties lack adequate health care infrastructure.9 More than a third of the US population has less-than-adequate access to pharmacies, primary care physicians, hospitals, trauma centers, and low-cost health centers.9 To put things into perspective, more than 20% of counties in the United States are hospital deserts, where most people must drive more than 30 minutes to reach the closest hospital.9

There is good reason for this. Operating a hospital is a challenging endeavor. Even before the COVID-19 pandemic and the most recent health care financial challenges, most health care systems and large hospitals operated with very low operating margins (2%–3%). Businesses with similar margins include grocery stores and car dealerships. These low-margin businesses, including health care, rely on high volume for sustainability. High patient volumes distribute expensive hospital costs over many encounters. If physicians cannot sustain practices across the country, it is challenging to have sufficient admission and surgical volumes to justify the cost base of hospitals.

To tie this together, we have very little influence on what we are paid for our services. Reimbursement is declining, which makes it hard to have financially sustainable practices. As hospitals struggle, there is more pressure to prioritize highly profitable service lines, like orthopedics and urology, which are associated with favorable technical revenue. As hospitals are threatened, health care deserts widen, which leaves our entire health care system in jeopardy. Not surprisingly, this most likely affects those who face additional barriers to access, such as those with lower income, limited internet access, and lack of insurance. Together, these barriers further widen disparities in health care outcomes, including outcomes for women. Additionally, this death by a thousand cuts has eroded morale and increased physician burnout.

Transforming how we practice medicine is the only viable solution. I have good news: You are the leaders you have been waiting for.

Continue to: Physicians make good managers...

Physicians make good managers

To successfully transform how we practice medicine, it is critical that those leading the transformation deeply understand how medicine is practiced. The level of understanding required can be achieved only through years of medical practice, as a doctor. We understand how medical teams interact and that different sectors of our health care system are interdependent. Also, because physicians drive patient activity and ultimately reimbursement, having a seat at the table is crucial.

Some health care systems are run by businesspeople—people with finance backgrounds—and others are led by physicians. In 2017, Becker’s Hospital Review listed the chief executive officers (CEOs) of 183 nonprofit hospital and health systems.10 Of these, only 25% were led by individuals with an MD. Looking at the 115 largest hospitals in the United States, 30% are physician led.10 Considering the top 10 hospitals ranked by U.S. News & World Report for 2022, 8 of 10 have a physician at the helm.

Beyond raters and rankers, physician-led hospitals do better. Goodall compared CEOs in the top 100 best hospitals in U.S. News & World Report in 3 key medical specialties: cancer, digestive disorders, and cardiac care.11 The study explored the question: “Are hospitals’ quality ranked more highly when they are led by a medically trained doctor or non-MD professional managers?”11 Analysis revealed that hospital quality scores are about 25% higher in physician-run hospitals than in manager-run hospitals.11 Additional research shows that good management practices correlate with hospital performance, and that “the proportion of managers with a clinical degree has the largest positive effect.”12

Several theories exist as to why doctors make good managers in the health care setting.13,14 Doctors may create a more sympathetic and productive work environment for other clinicians because they are one of them. They have peer-to-peer credibility—because they have walked the walk, they have insight and perspective into how medicine is practiced.

Physicians serve as effective change agents for their organizations in several ways:

- First, physicians take a clinical approach in their leadership roles13 and focus on patient care at the center of their decisions. We see the people behind the numbers. Simply put, we humanize the operational side of health care.

- As physicians, we understand the interconnectivity in the practice of medicine. While closing certain service lines may be financially beneficial, these services are often closely linked to profitable service lines.

- Beyond physicians taking a clinical approach to leadership, we emphasize quality.13 Because we all have experienced complications and lived through bad outcomes alongside our patients, we understand deeply how important patient safety and quality is, and we are not willing to sacrifice that for financial gain. For us, this is personal. We don’t see our solution to health care challenges as an “or” situation, instead we view it as an “and” situation.

- Physician leaders often can improve medical staff engagement.13 A 2018 national survey of physicians found that those who are satisfied with their leadership are more engaged at work, have greater job satisfaction, and are less likely to experience signs of burnout.15 Physician administrators add value here.

Continue to: Surgeons as leaders...

Surgeons as leaders

What do we know about surgeons as physician leaders? Looking at the previously mentioned lists of physician leaders, surgeons are relatively absent. In the Becker’s Hospital Review study of nonprofit hospitals, only 9% of CEOs were surgeons.10 In addition, when reviewing data that associated physician leaders and hospital performance, only 3 of the CEOs were surgeons.11 Given that surgeons make up approximately 19% of US physicians, we are underrepresented.

The omission of surgeons as leaders seems inappropriate given that most hospitals are financially reliant on revenue related to surgical care and optimizing this space is an enormous opportunity. Berger and colleagues offered 3 theories as to why there are fewer surgeon leaders16:

- The relative pay of surgeons exceeds that of most other specialties, and there may be less incentive to accept the challenges presented by leadership roles. (I will add that surgeon leadership is more costly to a system.)

- The craftsmanship nature of surgery discourages the development of other career interests beginning at the trainee level.

- Surgeons have been perceived stereotypically to exhibit arrogance, a characteristic that others may not warm to.

This last observation stings. Successful leadership takes social skill and teamwork.14 Although medical care is one of the few disciplines in which lack of teamwork might cost lives, physicians are not trained to be team players. We recognize how our training has led us to be lone wolves or gunners, situations where we as individuals had to beat others to secure our spot. We have been trained in command-and-control environments, in stepping up as a leader in highly stressful situations. This part of surgical culture may handicap surgeons in their quest to be health care leaders.

Other traits, however, make us particularly great leaders in health care. Our desire to succeed, willingness to push ourselves to extremes, ability to laser focus on a task, acceptance of delayed gratification, and aptitude for making timely decisions on limited data help us succeed in leadership roles. Seven years of surgical training helped me develop the grit I use every day in the C-suite.

We need more physician and surgeon leadership to thrive in the challenging health care landscape. Berger and colleagues proposed 3 potential solutions to increase the number of surgeons in hospital leadership positions16:

Nurture future surgical leaders through exposure to management training. Given the contribution to both expense in support services and resources and revenue related to surgical care, each organization needs a content expert to guide these decisions.

Recognize the important contributions that surgeons already make regarding quality, safety, and operational efficiency. An excellent example of this is the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. Because surgeons are content experts in this area, we are primed to lead.

Hospitals, medical schools, and academic departments of surgery should recognize administrative efforts as an important part of the overall academic mission. As the adage states, “No margin, no mission.” We need bright minds to preserve and grow our margins so that we can further invest in our missions.

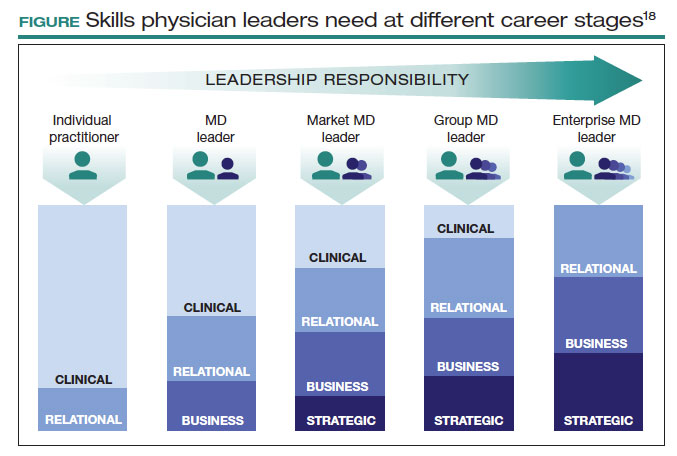

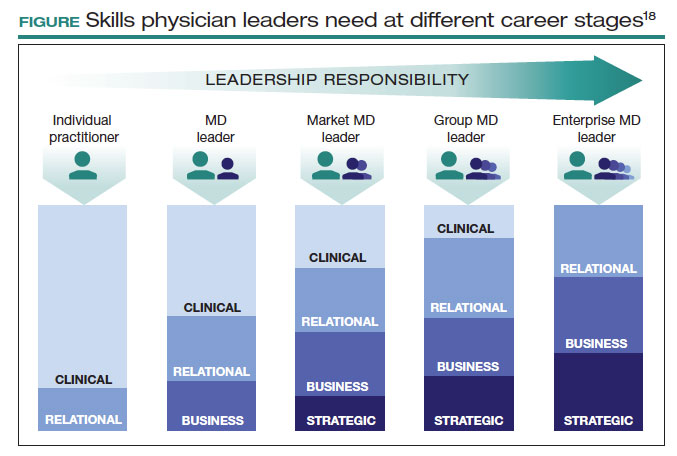

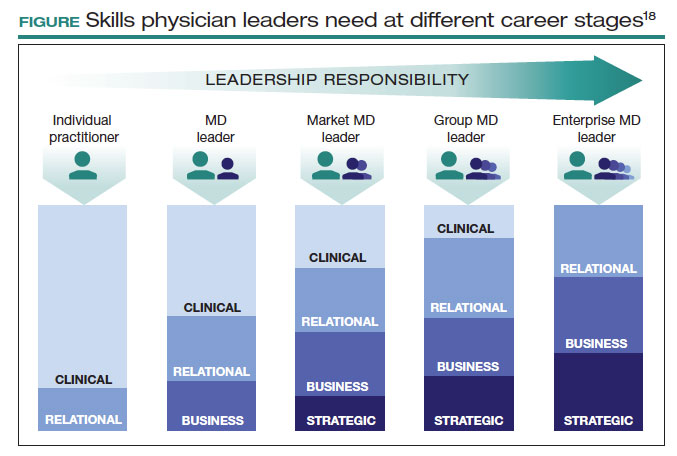

This is not easy. Given the barriers, this will not happen organically. Charan and colleagues provided an outline for a leadership pathway adapted for physicians (FIGURE).17,18 It starts with the individual practitioner who is a practicing physician and spends most of their time focused on patient care. As a physician becomes more interested in leadership, they develop new skills and take on more and more responsibility. As they increase in leadership responsibility, they tend to reduce clinical time and increase time spent on strategic and business management. This framework creates a pipeline so that physicians and surgeons can be developed strategically and given increasing responsibility as they develop their capabilities and expand their skill sets.

The leadership challenge

To thrive, we must transform health care by changing how we practice medicine. As ObGyns, we are the leaders we have been waiting for. As you ponder your future, think of your current career and the opportunities you might have. Do you have a seat at the table? What table is that? How are you using your knowledge, expertise, and privilege to advance health care and medicine? I challenge you to critically evaluate this—and lead. ●

- Law T. Ohio bill suggests doctors who perform abortions could face jail, unless they perform a non-existent treatment. December 1, 2019. Time. Accessed June 12, 2023. https://time.com/5742053 /ectopic-pregnancy-ohio-abortion-bill/

- Grossman D. Ohio abortion, ectopic pregnancy bill: ‘it’s both bad medicine and bad law-making.’ May 21, 2019. Cincinnati.com–The Enquirer. Accessed June 12, 2023. https://www .cincinnati.com/story/opinion/2019/05/21/ohio-abortion-bill -john-becker-daniel-grossman-ectopic-pregnancy-false-medicine /3753610002/

- Lobbyist had hand in bill sparking ectopic pregnancy flap. December 11, 2019. Associated Press. Accessed June 12, 2023. https://apnews .com/article/03216e44405fa184ae0ab80fa85089f8

- NHE fact sheet. CMS.gov. Updated February 17, 2023. Accessed June 12, 2023. https://www.cms.gov/research-statistics-data-and -systems/statistics-trends-and-reports/nationalhealthexpenddata /nhe-fact-sheet

- Senate passes omnibus spending bill with health provisions. December 23, 2022. American Hospital Association. Accessed June 12, 2023. https://www.aha.org/special-bulletin/2022-12-20-appropriations -committees-release-omnibus-spending-bill-health-provisions

- Medicare updates compared to inflation (2001-2021). October 2021. American Medical Association. Accessed June 12, 2023. https://www .ama-assn.org/system/files/medicare-pay-chart-2021.pdf

- Resneck Jr J. Medicare physician payment reform is long overdue. October 3, 2022. American Medical Association. Accessed June 7, 2023. https://www.ama-assn.org/about/leadership /medicare-physician-payment-reform-long-overdue

- Isenberg M. The stark reality of physician reimbursement. August 24, 2022. Zotec Partners. Accessed June 13, 2023. https://zotecpartners. com/advocacy-zpac/test-1/

- Nguyen A. Mapping healthcare deserts: 80% of the country lacks adequate access to healthcare. September 9, 2021. GoodRx Health. Accessed June 13, 2023. https://www.goodrx.com/healthcare -access/research/healthcare-deserts-80-percent-of-country-lacks -adequate-healthcare-access

- 183 nonprofit hospital and health system CEOs to know–2017. Updated June 20, 2018. Becker’s Hospital Review. Accessed June 7, 2023. https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/lists/188-nonprofit -hospital-and-health-system-ceos-to-know-2017.html

- Goodall AH. Physician-leaders and hospital performance: is there an association? Soc Sci Med. 2011;73:535-539. doi:10.1016 /j.socscimed.2011.06.025

- Bloom N, Sadun R, Van Reenen J. Does Management Matter in Healthcare? Center for Economic Performance and Harvard Business School; 2014.

- Turner J. Why healthcare C-suites should include physicians. September 3, 2019. Managed Healthcare Executive. Accessed June 13, 2023. https://www.managedhealthcareexecutive.com /view/why-healthcare-c-suites-should-include-physicians

- Stoller JK, Goodall A, Baker A. Why the best hospitals are managed by doctors. December 27, 2016. Harvard Business Review. Accessed June 13, 2023. https://hbr.org/2016/12/why-the-best-hospitals -are-managed-by-doctors

- Hayhurst C. Data confirms: leaders, physician burnout is on you. April 3, 2019. Aetnahealth. Accessed June 13, 2023. https://www .athenahealth.com/knowledge-hub/practice-management /research-confirms-leaders-burnout-you

- Berger DH, Goodall A, Tsai AY. The importance of increasing surgeon participation in hospital leadership. JAMA Surg. 2019;154:281-282. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2018.5080

- Charan R, Drotter S, Noel J. The Leadership Pipeline: How to Build the Leadership-Powered Company. Jossey-Bass; 2001.

- Perry J, Mobley F, Brubaker M. Most doctors have little or no management training, and that’s a problem. December 15, 2017. Harvard Business Review. Accessed June 7, 2023. https://hbr.org/2017/12 /most-doctors-have-little-or-no-management-training-and-thats -a-problem

“If you don’t have a seat at the table, you are probably on the menu.” I first heard this quote in 2013, and it launched my interest in health care leadership and influenced me countless times over the last 10 years.

As Chief of Staff at Cleveland Clinic, I oversee nearly 5,000 physicians and scientists across the globe. I am involved in the physician life cycle: recruiting, hiring, privileging and credentialing, talent development, promotion, professionalism, and career transitions. I also sit at the intersection of medical care and the business of medicine. This means leading 18 clinical service lines responsible for 5.6 million visits, 161,000 surgeries, and billions of dollars in operating revenue per year. How I spend most of my time is a far cry from what I spent 11 years’ training to do—gynecologic surgery. This shift in my career was not because I changed my mind about caring for patients or that I tired of being a full-time surgeon. Nothing could be further from the truth. Women’s health remains my “why,” and my leadership journey has taught me that it is critical to have a seat at the table for the sake of ObGyns and women everywhere.

Women’s health on the menu

I will start with a concrete example of when we, as women and ObGyns, were on the menu. In late 2019, the Ohio state House of Representatives introduced a bill that subjected doctors to potential murder charges if they did not try everything to save the life of a mother and fetus, “including attempting to reimplant an ectopic pregnancy into the woman’s uterus.”1 This bill was based on 2 case reports—one from 1915 and one from 1980—which were both low quality, and the latter case was deemed to be fraudulent.2 How did this happen?

An Ohio state representative developed the bill with help from a lobbyist and without input from physicians or content experts. When asked, the representative shared that “he never researched whether re-implanting an ectopic pregnancy into a woman’s uterus was a viable medical procedure before including it in the bill.”3 He added, “I heard about it over the years. I never questioned it or gave it a lot of thought.”3

This example resonates deeply with many of us; it inspires us to speak up and act. As ObGyns, we clearly understand the consequences of legal and regulatory change in women’s health and how it directly impacts our patients and each of us as physicians. Let’s shift to something that you may feel less passion about, but I believe is equally important. This is where obstetrician-gynecologists sit in the intersection of medical care and business. This is the space where I spend most of my time, and from this vantage point, I worry about our field.

The business of medicine

Starting at the macroeconomic level, let’s think about how we as physicians are reimbursed and who makes these decisions. Looking at the national health care expenditure data, Medicare and Medicaid spending makes up nearly 40% of the total spend, and it is growing.4 Additionally, private health insurance tends to follow Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) decision making, further compounding its influence.4 In simple terms, CMS decides what is covered and how much we are paid. Whether you are in a solo private practice, an employer health care organization, or an academic medical center, physician reimbursement is declining.

In fact, Congress passed its year-end omnibus legislation in the final days of 2022, including a 2% Medicare physician payment cut for 2023,5 at a time when expenses to practice medicine, including nonphysician staff and supplies, are at an all-time high and we are living in a 6% inflationary state. This translates into being asked to serve more patients and cut costs. Our day-to-day feels much tighter, and this is why: Medicare physician pay increased just 11% over the past 20 years6 (2001–2021) in comparison to the cost of running a medical practice, which increased nearly 40% during that time. In other words, adjusting for inflation in practice costs, Medicare physician payment has fallen 22% over the last 20 years.7

Depending on your employment model, you may feel insulated from these changes as increases in reimbursement have occurred in other areas, such as hospitals and ambulatory surgery centers.8 In the short term, these increases help, as organizations will see additional funds. But there are 2 main issues: First, it is not nearly enough when you consider the soaring costs of running a hospital. And second, looking at our national population, we rely tremendously on self-employed doctors to serve our patients.

More than 80% of US counties lack adequate health care infrastructure.9 More than a third of the US population has less-than-adequate access to pharmacies, primary care physicians, hospitals, trauma centers, and low-cost health centers.9 To put things into perspective, more than 20% of counties in the United States are hospital deserts, where most people must drive more than 30 minutes to reach the closest hospital.9

There is good reason for this. Operating a hospital is a challenging endeavor. Even before the COVID-19 pandemic and the most recent health care financial challenges, most health care systems and large hospitals operated with very low operating margins (2%–3%). Businesses with similar margins include grocery stores and car dealerships. These low-margin businesses, including health care, rely on high volume for sustainability. High patient volumes distribute expensive hospital costs over many encounters. If physicians cannot sustain practices across the country, it is challenging to have sufficient admission and surgical volumes to justify the cost base of hospitals.

To tie this together, we have very little influence on what we are paid for our services. Reimbursement is declining, which makes it hard to have financially sustainable practices. As hospitals struggle, there is more pressure to prioritize highly profitable service lines, like orthopedics and urology, which are associated with favorable technical revenue. As hospitals are threatened, health care deserts widen, which leaves our entire health care system in jeopardy. Not surprisingly, this most likely affects those who face additional barriers to access, such as those with lower income, limited internet access, and lack of insurance. Together, these barriers further widen disparities in health care outcomes, including outcomes for women. Additionally, this death by a thousand cuts has eroded morale and increased physician burnout.

Transforming how we practice medicine is the only viable solution. I have good news: You are the leaders you have been waiting for.

Continue to: Physicians make good managers...

Physicians make good managers

To successfully transform how we practice medicine, it is critical that those leading the transformation deeply understand how medicine is practiced. The level of understanding required can be achieved only through years of medical practice, as a doctor. We understand how medical teams interact and that different sectors of our health care system are interdependent. Also, because physicians drive patient activity and ultimately reimbursement, having a seat at the table is crucial.

Some health care systems are run by businesspeople—people with finance backgrounds—and others are led by physicians. In 2017, Becker’s Hospital Review listed the chief executive officers (CEOs) of 183 nonprofit hospital and health systems.10 Of these, only 25% were led by individuals with an MD. Looking at the 115 largest hospitals in the United States, 30% are physician led.10 Considering the top 10 hospitals ranked by U.S. News & World Report for 2022, 8 of 10 have a physician at the helm.

Beyond raters and rankers, physician-led hospitals do better. Goodall compared CEOs in the top 100 best hospitals in U.S. News & World Report in 3 key medical specialties: cancer, digestive disorders, and cardiac care.11 The study explored the question: “Are hospitals’ quality ranked more highly when they are led by a medically trained doctor or non-MD professional managers?”11 Analysis revealed that hospital quality scores are about 25% higher in physician-run hospitals than in manager-run hospitals.11 Additional research shows that good management practices correlate with hospital performance, and that “the proportion of managers with a clinical degree has the largest positive effect.”12

Several theories exist as to why doctors make good managers in the health care setting.13,14 Doctors may create a more sympathetic and productive work environment for other clinicians because they are one of them. They have peer-to-peer credibility—because they have walked the walk, they have insight and perspective into how medicine is practiced.

Physicians serve as effective change agents for their organizations in several ways:

- First, physicians take a clinical approach in their leadership roles13 and focus on patient care at the center of their decisions. We see the people behind the numbers. Simply put, we humanize the operational side of health care.

- As physicians, we understand the interconnectivity in the practice of medicine. While closing certain service lines may be financially beneficial, these services are often closely linked to profitable service lines.

- Beyond physicians taking a clinical approach to leadership, we emphasize quality.13 Because we all have experienced complications and lived through bad outcomes alongside our patients, we understand deeply how important patient safety and quality is, and we are not willing to sacrifice that for financial gain. For us, this is personal. We don’t see our solution to health care challenges as an “or” situation, instead we view it as an “and” situation.

- Physician leaders often can improve medical staff engagement.13 A 2018 national survey of physicians found that those who are satisfied with their leadership are more engaged at work, have greater job satisfaction, and are less likely to experience signs of burnout.15 Physician administrators add value here.

Continue to: Surgeons as leaders...

Surgeons as leaders

What do we know about surgeons as physician leaders? Looking at the previously mentioned lists of physician leaders, surgeons are relatively absent. In the Becker’s Hospital Review study of nonprofit hospitals, only 9% of CEOs were surgeons.10 In addition, when reviewing data that associated physician leaders and hospital performance, only 3 of the CEOs were surgeons.11 Given that surgeons make up approximately 19% of US physicians, we are underrepresented.

The omission of surgeons as leaders seems inappropriate given that most hospitals are financially reliant on revenue related to surgical care and optimizing this space is an enormous opportunity. Berger and colleagues offered 3 theories as to why there are fewer surgeon leaders16:

- The relative pay of surgeons exceeds that of most other specialties, and there may be less incentive to accept the challenges presented by leadership roles. (I will add that surgeon leadership is more costly to a system.)

- The craftsmanship nature of surgery discourages the development of other career interests beginning at the trainee level.

- Surgeons have been perceived stereotypically to exhibit arrogance, a characteristic that others may not warm to.

This last observation stings. Successful leadership takes social skill and teamwork.14 Although medical care is one of the few disciplines in which lack of teamwork might cost lives, physicians are not trained to be team players. We recognize how our training has led us to be lone wolves or gunners, situations where we as individuals had to beat others to secure our spot. We have been trained in command-and-control environments, in stepping up as a leader in highly stressful situations. This part of surgical culture may handicap surgeons in their quest to be health care leaders.

Other traits, however, make us particularly great leaders in health care. Our desire to succeed, willingness to push ourselves to extremes, ability to laser focus on a task, acceptance of delayed gratification, and aptitude for making timely decisions on limited data help us succeed in leadership roles. Seven years of surgical training helped me develop the grit I use every day in the C-suite.

We need more physician and surgeon leadership to thrive in the challenging health care landscape. Berger and colleagues proposed 3 potential solutions to increase the number of surgeons in hospital leadership positions16:

Nurture future surgical leaders through exposure to management training. Given the contribution to both expense in support services and resources and revenue related to surgical care, each organization needs a content expert to guide these decisions.

Recognize the important contributions that surgeons already make regarding quality, safety, and operational efficiency. An excellent example of this is the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. Because surgeons are content experts in this area, we are primed to lead.

Hospitals, medical schools, and academic departments of surgery should recognize administrative efforts as an important part of the overall academic mission. As the adage states, “No margin, no mission.” We need bright minds to preserve and grow our margins so that we can further invest in our missions.

This is not easy. Given the barriers, this will not happen organically. Charan and colleagues provided an outline for a leadership pathway adapted for physicians (FIGURE).17,18 It starts with the individual practitioner who is a practicing physician and spends most of their time focused on patient care. As a physician becomes more interested in leadership, they develop new skills and take on more and more responsibility. As they increase in leadership responsibility, they tend to reduce clinical time and increase time spent on strategic and business management. This framework creates a pipeline so that physicians and surgeons can be developed strategically and given increasing responsibility as they develop their capabilities and expand their skill sets.

The leadership challenge

To thrive, we must transform health care by changing how we practice medicine. As ObGyns, we are the leaders we have been waiting for. As you ponder your future, think of your current career and the opportunities you might have. Do you have a seat at the table? What table is that? How are you using your knowledge, expertise, and privilege to advance health care and medicine? I challenge you to critically evaluate this—and lead. ●

“If you don’t have a seat at the table, you are probably on the menu.” I first heard this quote in 2013, and it launched my interest in health care leadership and influenced me countless times over the last 10 years.

As Chief of Staff at Cleveland Clinic, I oversee nearly 5,000 physicians and scientists across the globe. I am involved in the physician life cycle: recruiting, hiring, privileging and credentialing, talent development, promotion, professionalism, and career transitions. I also sit at the intersection of medical care and the business of medicine. This means leading 18 clinical service lines responsible for 5.6 million visits, 161,000 surgeries, and billions of dollars in operating revenue per year. How I spend most of my time is a far cry from what I spent 11 years’ training to do—gynecologic surgery. This shift in my career was not because I changed my mind about caring for patients or that I tired of being a full-time surgeon. Nothing could be further from the truth. Women’s health remains my “why,” and my leadership journey has taught me that it is critical to have a seat at the table for the sake of ObGyns and women everywhere.

Women’s health on the menu

I will start with a concrete example of when we, as women and ObGyns, were on the menu. In late 2019, the Ohio state House of Representatives introduced a bill that subjected doctors to potential murder charges if they did not try everything to save the life of a mother and fetus, “including attempting to reimplant an ectopic pregnancy into the woman’s uterus.”1 This bill was based on 2 case reports—one from 1915 and one from 1980—which were both low quality, and the latter case was deemed to be fraudulent.2 How did this happen?

An Ohio state representative developed the bill with help from a lobbyist and without input from physicians or content experts. When asked, the representative shared that “he never researched whether re-implanting an ectopic pregnancy into a woman’s uterus was a viable medical procedure before including it in the bill.”3 He added, “I heard about it over the years. I never questioned it or gave it a lot of thought.”3

This example resonates deeply with many of us; it inspires us to speak up and act. As ObGyns, we clearly understand the consequences of legal and regulatory change in women’s health and how it directly impacts our patients and each of us as physicians. Let’s shift to something that you may feel less passion about, but I believe is equally important. This is where obstetrician-gynecologists sit in the intersection of medical care and business. This is the space where I spend most of my time, and from this vantage point, I worry about our field.

The business of medicine

Starting at the macroeconomic level, let’s think about how we as physicians are reimbursed and who makes these decisions. Looking at the national health care expenditure data, Medicare and Medicaid spending makes up nearly 40% of the total spend, and it is growing.4 Additionally, private health insurance tends to follow Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) decision making, further compounding its influence.4 In simple terms, CMS decides what is covered and how much we are paid. Whether you are in a solo private practice, an employer health care organization, or an academic medical center, physician reimbursement is declining.

In fact, Congress passed its year-end omnibus legislation in the final days of 2022, including a 2% Medicare physician payment cut for 2023,5 at a time when expenses to practice medicine, including nonphysician staff and supplies, are at an all-time high and we are living in a 6% inflationary state. This translates into being asked to serve more patients and cut costs. Our day-to-day feels much tighter, and this is why: Medicare physician pay increased just 11% over the past 20 years6 (2001–2021) in comparison to the cost of running a medical practice, which increased nearly 40% during that time. In other words, adjusting for inflation in practice costs, Medicare physician payment has fallen 22% over the last 20 years.7

Depending on your employment model, you may feel insulated from these changes as increases in reimbursement have occurred in other areas, such as hospitals and ambulatory surgery centers.8 In the short term, these increases help, as organizations will see additional funds. But there are 2 main issues: First, it is not nearly enough when you consider the soaring costs of running a hospital. And second, looking at our national population, we rely tremendously on self-employed doctors to serve our patients.

More than 80% of US counties lack adequate health care infrastructure.9 More than a third of the US population has less-than-adequate access to pharmacies, primary care physicians, hospitals, trauma centers, and low-cost health centers.9 To put things into perspective, more than 20% of counties in the United States are hospital deserts, where most people must drive more than 30 minutes to reach the closest hospital.9

There is good reason for this. Operating a hospital is a challenging endeavor. Even before the COVID-19 pandemic and the most recent health care financial challenges, most health care systems and large hospitals operated with very low operating margins (2%–3%). Businesses with similar margins include grocery stores and car dealerships. These low-margin businesses, including health care, rely on high volume for sustainability. High patient volumes distribute expensive hospital costs over many encounters. If physicians cannot sustain practices across the country, it is challenging to have sufficient admission and surgical volumes to justify the cost base of hospitals.

To tie this together, we have very little influence on what we are paid for our services. Reimbursement is declining, which makes it hard to have financially sustainable practices. As hospitals struggle, there is more pressure to prioritize highly profitable service lines, like orthopedics and urology, which are associated with favorable technical revenue. As hospitals are threatened, health care deserts widen, which leaves our entire health care system in jeopardy. Not surprisingly, this most likely affects those who face additional barriers to access, such as those with lower income, limited internet access, and lack of insurance. Together, these barriers further widen disparities in health care outcomes, including outcomes for women. Additionally, this death by a thousand cuts has eroded morale and increased physician burnout.

Transforming how we practice medicine is the only viable solution. I have good news: You are the leaders you have been waiting for.

Continue to: Physicians make good managers...

Physicians make good managers

To successfully transform how we practice medicine, it is critical that those leading the transformation deeply understand how medicine is practiced. The level of understanding required can be achieved only through years of medical practice, as a doctor. We understand how medical teams interact and that different sectors of our health care system are interdependent. Also, because physicians drive patient activity and ultimately reimbursement, having a seat at the table is crucial.

Some health care systems are run by businesspeople—people with finance backgrounds—and others are led by physicians. In 2017, Becker’s Hospital Review listed the chief executive officers (CEOs) of 183 nonprofit hospital and health systems.10 Of these, only 25% were led by individuals with an MD. Looking at the 115 largest hospitals in the United States, 30% are physician led.10 Considering the top 10 hospitals ranked by U.S. News & World Report for 2022, 8 of 10 have a physician at the helm.

Beyond raters and rankers, physician-led hospitals do better. Goodall compared CEOs in the top 100 best hospitals in U.S. News & World Report in 3 key medical specialties: cancer, digestive disorders, and cardiac care.11 The study explored the question: “Are hospitals’ quality ranked more highly when they are led by a medically trained doctor or non-MD professional managers?”11 Analysis revealed that hospital quality scores are about 25% higher in physician-run hospitals than in manager-run hospitals.11 Additional research shows that good management practices correlate with hospital performance, and that “the proportion of managers with a clinical degree has the largest positive effect.”12

Several theories exist as to why doctors make good managers in the health care setting.13,14 Doctors may create a more sympathetic and productive work environment for other clinicians because they are one of them. They have peer-to-peer credibility—because they have walked the walk, they have insight and perspective into how medicine is practiced.

Physicians serve as effective change agents for their organizations in several ways:

- First, physicians take a clinical approach in their leadership roles13 and focus on patient care at the center of their decisions. We see the people behind the numbers. Simply put, we humanize the operational side of health care.

- As physicians, we understand the interconnectivity in the practice of medicine. While closing certain service lines may be financially beneficial, these services are often closely linked to profitable service lines.

- Beyond physicians taking a clinical approach to leadership, we emphasize quality.13 Because we all have experienced complications and lived through bad outcomes alongside our patients, we understand deeply how important patient safety and quality is, and we are not willing to sacrifice that for financial gain. For us, this is personal. We don’t see our solution to health care challenges as an “or” situation, instead we view it as an “and” situation.

- Physician leaders often can improve medical staff engagement.13 A 2018 national survey of physicians found that those who are satisfied with their leadership are more engaged at work, have greater job satisfaction, and are less likely to experience signs of burnout.15 Physician administrators add value here.

Continue to: Surgeons as leaders...

Surgeons as leaders

What do we know about surgeons as physician leaders? Looking at the previously mentioned lists of physician leaders, surgeons are relatively absent. In the Becker’s Hospital Review study of nonprofit hospitals, only 9% of CEOs were surgeons.10 In addition, when reviewing data that associated physician leaders and hospital performance, only 3 of the CEOs were surgeons.11 Given that surgeons make up approximately 19% of US physicians, we are underrepresented.

The omission of surgeons as leaders seems inappropriate given that most hospitals are financially reliant on revenue related to surgical care and optimizing this space is an enormous opportunity. Berger and colleagues offered 3 theories as to why there are fewer surgeon leaders16:

- The relative pay of surgeons exceeds that of most other specialties, and there may be less incentive to accept the challenges presented by leadership roles. (I will add that surgeon leadership is more costly to a system.)

- The craftsmanship nature of surgery discourages the development of other career interests beginning at the trainee level.

- Surgeons have been perceived stereotypically to exhibit arrogance, a characteristic that others may not warm to.

This last observation stings. Successful leadership takes social skill and teamwork.14 Although medical care is one of the few disciplines in which lack of teamwork might cost lives, physicians are not trained to be team players. We recognize how our training has led us to be lone wolves or gunners, situations where we as individuals had to beat others to secure our spot. We have been trained in command-and-control environments, in stepping up as a leader in highly stressful situations. This part of surgical culture may handicap surgeons in their quest to be health care leaders.

Other traits, however, make us particularly great leaders in health care. Our desire to succeed, willingness to push ourselves to extremes, ability to laser focus on a task, acceptance of delayed gratification, and aptitude for making timely decisions on limited data help us succeed in leadership roles. Seven years of surgical training helped me develop the grit I use every day in the C-suite.

We need more physician and surgeon leadership to thrive in the challenging health care landscape. Berger and colleagues proposed 3 potential solutions to increase the number of surgeons in hospital leadership positions16:

Nurture future surgical leaders through exposure to management training. Given the contribution to both expense in support services and resources and revenue related to surgical care, each organization needs a content expert to guide these decisions.

Recognize the important contributions that surgeons already make regarding quality, safety, and operational efficiency. An excellent example of this is the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. Because surgeons are content experts in this area, we are primed to lead.

Hospitals, medical schools, and academic departments of surgery should recognize administrative efforts as an important part of the overall academic mission. As the adage states, “No margin, no mission.” We need bright minds to preserve and grow our margins so that we can further invest in our missions.

This is not easy. Given the barriers, this will not happen organically. Charan and colleagues provided an outline for a leadership pathway adapted for physicians (FIGURE).17,18 It starts with the individual practitioner who is a practicing physician and spends most of their time focused on patient care. As a physician becomes more interested in leadership, they develop new skills and take on more and more responsibility. As they increase in leadership responsibility, they tend to reduce clinical time and increase time spent on strategic and business management. This framework creates a pipeline so that physicians and surgeons can be developed strategically and given increasing responsibility as they develop their capabilities and expand their skill sets.

The leadership challenge

To thrive, we must transform health care by changing how we practice medicine. As ObGyns, we are the leaders we have been waiting for. As you ponder your future, think of your current career and the opportunities you might have. Do you have a seat at the table? What table is that? How are you using your knowledge, expertise, and privilege to advance health care and medicine? I challenge you to critically evaluate this—and lead. ●

- Law T. Ohio bill suggests doctors who perform abortions could face jail, unless they perform a non-existent treatment. December 1, 2019. Time. Accessed June 12, 2023. https://time.com/5742053 /ectopic-pregnancy-ohio-abortion-bill/

- Grossman D. Ohio abortion, ectopic pregnancy bill: ‘it’s both bad medicine and bad law-making.’ May 21, 2019. Cincinnati.com–The Enquirer. Accessed June 12, 2023. https://www .cincinnati.com/story/opinion/2019/05/21/ohio-abortion-bill -john-becker-daniel-grossman-ectopic-pregnancy-false-medicine /3753610002/

- Lobbyist had hand in bill sparking ectopic pregnancy flap. December 11, 2019. Associated Press. Accessed June 12, 2023. https://apnews .com/article/03216e44405fa184ae0ab80fa85089f8

- NHE fact sheet. CMS.gov. Updated February 17, 2023. Accessed June 12, 2023. https://www.cms.gov/research-statistics-data-and -systems/statistics-trends-and-reports/nationalhealthexpenddata /nhe-fact-sheet

- Senate passes omnibus spending bill with health provisions. December 23, 2022. American Hospital Association. Accessed June 12, 2023. https://www.aha.org/special-bulletin/2022-12-20-appropriations -committees-release-omnibus-spending-bill-health-provisions

- Medicare updates compared to inflation (2001-2021). October 2021. American Medical Association. Accessed June 12, 2023. https://www .ama-assn.org/system/files/medicare-pay-chart-2021.pdf

- Resneck Jr J. Medicare physician payment reform is long overdue. October 3, 2022. American Medical Association. Accessed June 7, 2023. https://www.ama-assn.org/about/leadership /medicare-physician-payment-reform-long-overdue

- Isenberg M. The stark reality of physician reimbursement. August 24, 2022. Zotec Partners. Accessed June 13, 2023. https://zotecpartners. com/advocacy-zpac/test-1/

- Nguyen A. Mapping healthcare deserts: 80% of the country lacks adequate access to healthcare. September 9, 2021. GoodRx Health. Accessed June 13, 2023. https://www.goodrx.com/healthcare -access/research/healthcare-deserts-80-percent-of-country-lacks -adequate-healthcare-access

- 183 nonprofit hospital and health system CEOs to know–2017. Updated June 20, 2018. Becker’s Hospital Review. Accessed June 7, 2023. https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/lists/188-nonprofit -hospital-and-health-system-ceos-to-know-2017.html

- Goodall AH. Physician-leaders and hospital performance: is there an association? Soc Sci Med. 2011;73:535-539. doi:10.1016 /j.socscimed.2011.06.025

- Bloom N, Sadun R, Van Reenen J. Does Management Matter in Healthcare? Center for Economic Performance and Harvard Business School; 2014.

- Turner J. Why healthcare C-suites should include physicians. September 3, 2019. Managed Healthcare Executive. Accessed June 13, 2023. https://www.managedhealthcareexecutive.com /view/why-healthcare-c-suites-should-include-physicians

- Stoller JK, Goodall A, Baker A. Why the best hospitals are managed by doctors. December 27, 2016. Harvard Business Review. Accessed June 13, 2023. https://hbr.org/2016/12/why-the-best-hospitals -are-managed-by-doctors

- Hayhurst C. Data confirms: leaders, physician burnout is on you. April 3, 2019. Aetnahealth. Accessed June 13, 2023. https://www .athenahealth.com/knowledge-hub/practice-management /research-confirms-leaders-burnout-you

- Berger DH, Goodall A, Tsai AY. The importance of increasing surgeon participation in hospital leadership. JAMA Surg. 2019;154:281-282. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2018.5080

- Charan R, Drotter S, Noel J. The Leadership Pipeline: How to Build the Leadership-Powered Company. Jossey-Bass; 2001.

- Perry J, Mobley F, Brubaker M. Most doctors have little or no management training, and that’s a problem. December 15, 2017. Harvard Business Review. Accessed June 7, 2023. https://hbr.org/2017/12 /most-doctors-have-little-or-no-management-training-and-thats -a-problem

- Law T. Ohio bill suggests doctors who perform abortions could face jail, unless they perform a non-existent treatment. December 1, 2019. Time. Accessed June 12, 2023. https://time.com/5742053 /ectopic-pregnancy-ohio-abortion-bill/

- Grossman D. Ohio abortion, ectopic pregnancy bill: ‘it’s both bad medicine and bad law-making.’ May 21, 2019. Cincinnati.com–The Enquirer. Accessed June 12, 2023. https://www .cincinnati.com/story/opinion/2019/05/21/ohio-abortion-bill -john-becker-daniel-grossman-ectopic-pregnancy-false-medicine /3753610002/

- Lobbyist had hand in bill sparking ectopic pregnancy flap. December 11, 2019. Associated Press. Accessed June 12, 2023. https://apnews .com/article/03216e44405fa184ae0ab80fa85089f8

- NHE fact sheet. CMS.gov. Updated February 17, 2023. Accessed June 12, 2023. https://www.cms.gov/research-statistics-data-and -systems/statistics-trends-and-reports/nationalhealthexpenddata /nhe-fact-sheet

- Senate passes omnibus spending bill with health provisions. December 23, 2022. American Hospital Association. Accessed June 12, 2023. https://www.aha.org/special-bulletin/2022-12-20-appropriations -committees-release-omnibus-spending-bill-health-provisions

- Medicare updates compared to inflation (2001-2021). October 2021. American Medical Association. Accessed June 12, 2023. https://www .ama-assn.org/system/files/medicare-pay-chart-2021.pdf

- Resneck Jr J. Medicare physician payment reform is long overdue. October 3, 2022. American Medical Association. Accessed June 7, 2023. https://www.ama-assn.org/about/leadership /medicare-physician-payment-reform-long-overdue

- Isenberg M. The stark reality of physician reimbursement. August 24, 2022. Zotec Partners. Accessed June 13, 2023. https://zotecpartners. com/advocacy-zpac/test-1/

- Nguyen A. Mapping healthcare deserts: 80% of the country lacks adequate access to healthcare. September 9, 2021. GoodRx Health. Accessed June 13, 2023. https://www.goodrx.com/healthcare -access/research/healthcare-deserts-80-percent-of-country-lacks -adequate-healthcare-access

- 183 nonprofit hospital and health system CEOs to know–2017. Updated June 20, 2018. Becker’s Hospital Review. Accessed June 7, 2023. https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/lists/188-nonprofit -hospital-and-health-system-ceos-to-know-2017.html

- Goodall AH. Physician-leaders and hospital performance: is there an association? Soc Sci Med. 2011;73:535-539. doi:10.1016 /j.socscimed.2011.06.025

- Bloom N, Sadun R, Van Reenen J. Does Management Matter in Healthcare? Center for Economic Performance and Harvard Business School; 2014.

- Turner J. Why healthcare C-suites should include physicians. September 3, 2019. Managed Healthcare Executive. Accessed June 13, 2023. https://www.managedhealthcareexecutive.com /view/why-healthcare-c-suites-should-include-physicians

- Stoller JK, Goodall A, Baker A. Why the best hospitals are managed by doctors. December 27, 2016. Harvard Business Review. Accessed June 13, 2023. https://hbr.org/2016/12/why-the-best-hospitals -are-managed-by-doctors

- Hayhurst C. Data confirms: leaders, physician burnout is on you. April 3, 2019. Aetnahealth. Accessed June 13, 2023. https://www .athenahealth.com/knowledge-hub/practice-management /research-confirms-leaders-burnout-you

- Berger DH, Goodall A, Tsai AY. The importance of increasing surgeon participation in hospital leadership. JAMA Surg. 2019;154:281-282. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2018.5080

- Charan R, Drotter S, Noel J. The Leadership Pipeline: How to Build the Leadership-Powered Company. Jossey-Bass; 2001.

- Perry J, Mobley F, Brubaker M. Most doctors have little or no management training, and that’s a problem. December 15, 2017. Harvard Business Review. Accessed June 7, 2023. https://hbr.org/2017/12 /most-doctors-have-little-or-no-management-training-and-thats -a-problem

Surgical volume and outcomes for gynecologic surgery: Is more always better?

Over the last 3 decades, abundant evidence has demonstrated the association between surgical volume and outcomes. Patients operated on by high-volume surgeons and at high-volume hospitals have superior outcomes.

Surgical volume in gynecology

The association between both hospital and surgeon volume and outcomes has been explored across a number of gynecologic procedures.3 A meta-analysis that included 741,000 patients found that low-volume surgeons had an increased rate of complications overall, a higher rate of intraoperative complications, and a higher rate of postoperative complications compared with high-volume surgeons. While there was no association between volume and mortality overall, when limited to gynecologic oncology studies, low surgeon volume was associated with increased perioperative mortality.3

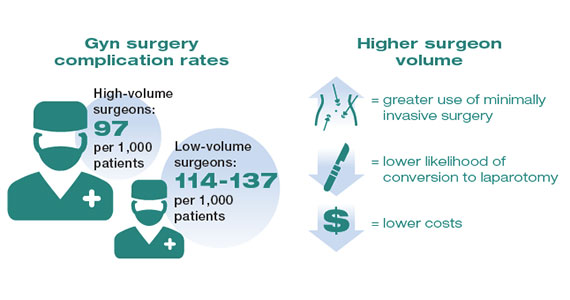

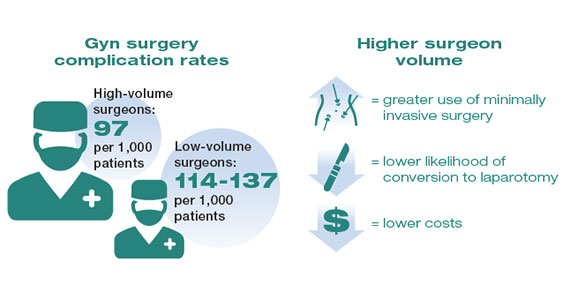

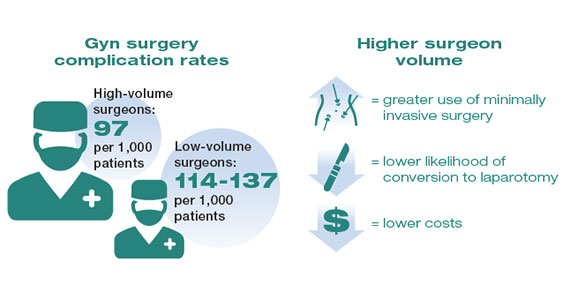

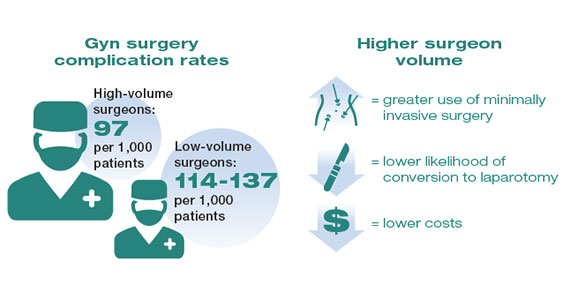

While these studies demonstrated a statistically significant association between surgeon volume and perioperative outcomes, the magnitude of the effect is modest compared with other higher-risk procedures associated with greater perioperative morbidity. For example, in a large study that examined oncologic and cardiovascular surgery, perioperative mortality in patients who underwent pancreatic resection was reduced from 15% for low-volume surgeons to 5% for high-volume surgeons.1 By contrast, for gynecologic surgery, complications occurred in 97 per 1,000 patients operated on by high-volume surgeons compared with between 114 and 137 per 1,000 for low-volume surgeons. Thus, to avoid 1 in-hospital complication, 30 surgeries performed by low-volume surgeons would need to be moved to high-volume surgeons. For intraoperative complications, 38 patients would need to be moved from low- to high-volume surgeons to prevent 1 such complication.3 In addition to morbidity and mortality, higher surgeon volume is associated with greater use of minimally invasive surgery, a lower likelihood of conversion to laparotomy, and lower costs.3

Similarly, hospital volume also has been associated with outcomes for gynecologic surgery.4 In a report of patients who underwent laparoscopic hysterectomy, the authors found that the complication rate was 18% lower for patients at high- versus low-volume hospitals. In addition, cost was lower at the high-volume centers.4 Like surgeon volume, the magnitude of the differential in outcomes between high- and low-volume hospitals is often modest.4

While most studies have focused on short-term outcomes, surgical volume appears also to be associated with longer-term outcomes. For gynecologic cancer, studies have demonstrated an association between hospital volume and survival for ovarian and cervical cancer.5-7 A large report of centers across the United States found that the 5-year survival rate increased from 39% for patients treated at low-volume centers to 51% at the highest-volume hospitals.5 In urogynecology, surgeon volume has been associated with midurethral sling revision. One study noted that after an individual surgeon performed 50 procedures a year, each additional case was associated with a decline in the rate of sling revision.8 One could argue that these longer-term end points may be the measures that matter most to patients.

Although the magnitude of the association between surgical volume and outcomes in gynecology appears to be relatively modest, outcomes for very-low-volume (VLV) surgeons are substantially worse. An analysis of more than 430,000 patients who underwent hysterectomy compared outcomes between VLV surgeons (characterized as surgeons who performed only 1 hysterectomy in the prior year) and other gynecologic surgeons. The overall complication rate was 32% in VLV surgeons compared with 10% among other surgeons, while the perioperative mortality rate was 2.5% versus 0.2% in the 2 groups, respectively. Likely reflecting changing practice patterns in gynecology, a sizable number of surgeons were classified as VLV physicians.9

Continue to: Public health applications of gynecologic surgical volume...

Public health applications of gynecologic surgical volume

The large body of literature on volume and outcomes has led to a number of public health initiatives aimed at reducing perioperative morbidity and mortality. Broadly, these efforts focus on regionalization of care, targeted quality improvement, and the development of minimum volume standards. Each strategy holds promise but also the potential to lead to unwanted consequences.

Regionalization of care

Recognition of the volume-outcomes paradigm has led to efforts to regionalize care for complex procedures to high-volume surgeons and centers.10 A cohort study of surgical patterns of care for Medicare recipients who underwent cancer resections or abdominal aortic aneurysm repair from 1999 to 2008 demonstrated these shifting practice patterns. For example, in 1999–2000, pancreatectomy was performed in 1,308 hospitals, with a median case volume of 5 procedures per year. By 2007–2008, the number of hospitals in which pancreatectomy was performed declined to 978, and the median case volume rose to 16 procedures per year. Importantly, over this time period, risk-adjusted mortality for pancreatectomy declined by 19%, and increased hospital volume was responsible for more than two-thirds of the decline in mortality.10

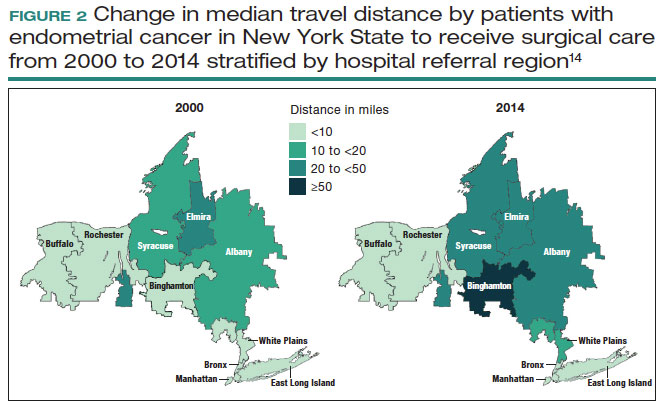

There has similarly been a gradual concentration of some gynecologic procedures to higher-volume surgeons and centers.11,12 Among patients undergoing hysterectomy for endometrial cancer in New York State, 845 surgeons with a mean case volume of 3 procedures per year treated patients in 2000. By 2014, the number of surgeons who performed these operations declined to 317 while mean annual case volume rose to 10 procedures per year. The number of hospitals in which women with endometrial cancer were treated declined from 182 to 98 over the same time period.11 Similar trends were noted for patients undergoing ovarian cancer resection.12 While patterns of gynecologic care for some surgical procedures have clearly changed, it has been more difficult to link these changes to improvements in outcomes.11,12

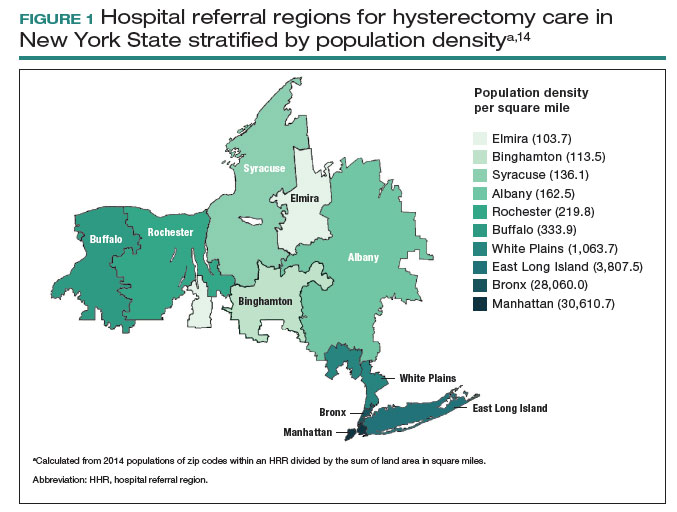

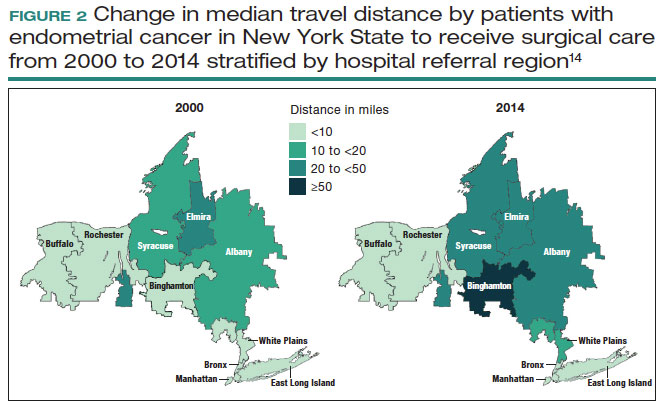

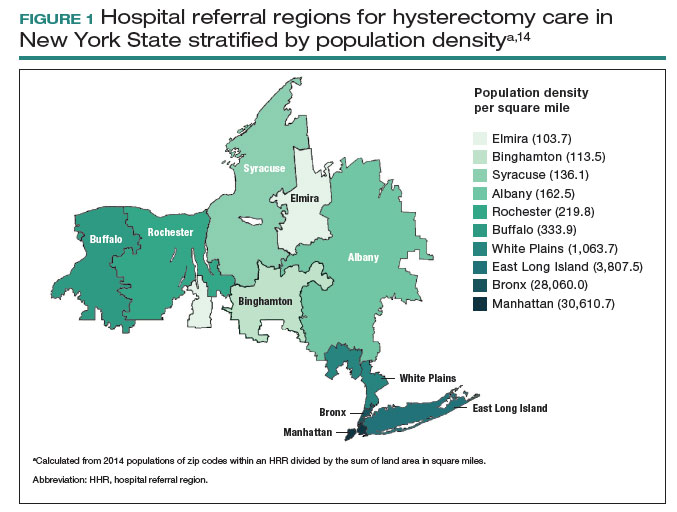

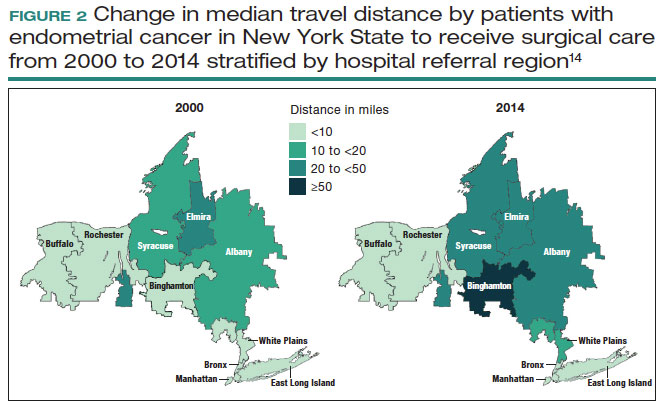

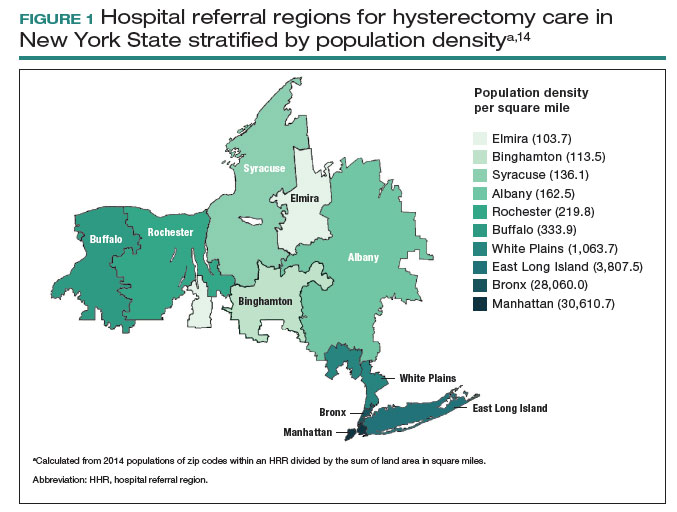

Despite the intuitive appeal of regionalization of surgical care, such a strategy has a number of limitations and practical challenges. Not surprisingly, limiting the number of surgeons and hospitals that perform a given procedure necessitates that patients travel a greater distance to obtain necessary surgical care.13,14 An analysis of endometrial cancer patients in New York State stratified patients based on their area of residence into 10 hospital referral regions (HRRs), which represent health care markets for tertiary medical care. From 2000 to 2014, the distance patients traveled to receive their surgical care increased in all of the HRRs studied. This was most pronounced in 1 of the HRRs in which the median travel distance rose by 47 miles over the 15-year period (FIGURE 1; FIGURE 2).14

Whether patients are willing to travel for care remains a matter of debate and depends on the disease, the surgical procedure, and the anticipated benefit associated with a longer travel distance.15,16 In a discrete choice experiment, 100 participants were given a hypothetical scenario in which they had potentially resectable pancreatic cancer; they were queried on their willingness to travel for care based on varying differences in mortality between a local and regional hospital.15 When mortality at the local hospital was double that of the regional hospital (6% vs 3%), 45% of patients chose to remain at the local hospital. When the differential increased to a 4 times greater mortality at the local hospital (12% vs 3%), 23% of patients still chose to remain at the local hospital.15

A similar study asked patients with ovarian neoplasms whether they would travel 50 miles to a regional center for surgery based on some degree of increased 5-year survival.16 Overall, 79% of patients would travel for a 4% improvement in survival while 97% would travel for a 12% improvement in survival.16

Lastly, a number of studies have shown that regionalization of surgical care disproportionately affects Black and Hispanic patients and those with low socioeconomic status.12,13,17 A simulation study on the effect of regionalizing care for pancreatectomy noted that using a hospital volume threshold of 20 procedures per year, a higher percentage of Black and Hispanic patients than White patients would be required to travel to a higher-volume center.13 Similarly, Medicaid recipients were more likely to be affected.13 Despite the inequities in who must travel for regionalized care, prior work has suggested that regionalization of cancer care to high-volume centers may reduce racial and socioeconomic disparities in survival for some cancers.18

Targeted quality improvement

Realizing the practical limitations of regionalization of care, an alternative strategy is to improve the quality of care at low-volume hospitals.5,19 Quality of care and surgical volume often are correlated, and the delivery of high-quality care can mitigate some of the influence of surgical volume on outcomes.

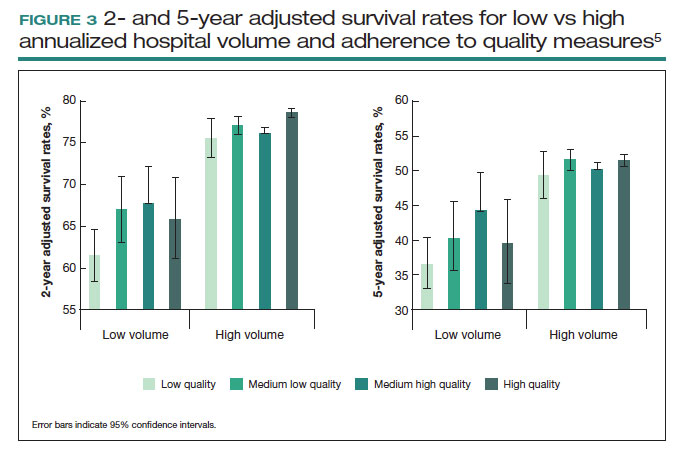

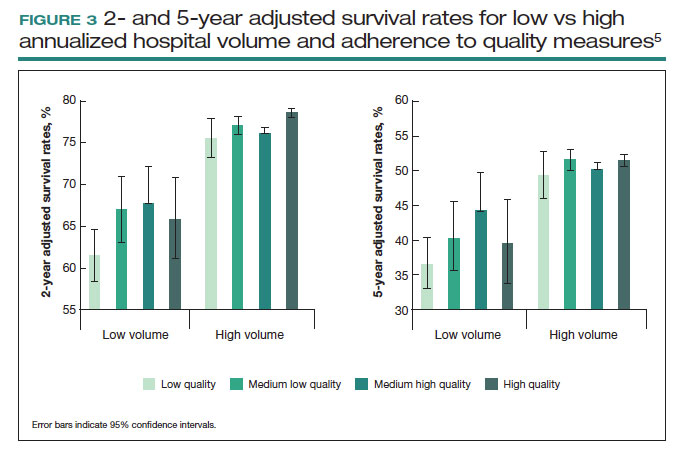

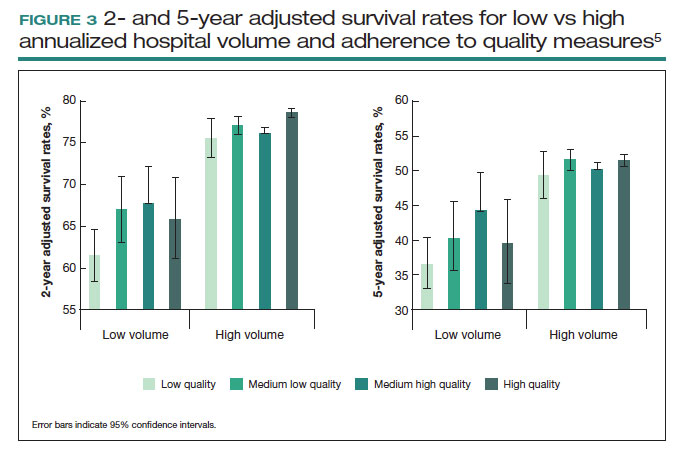

These principles were demonstrated in a study of more than 100,000 patients with ovarian cancer that stratified treating hospitals into volume quintiles.5 As expected, survival (both 2- and 5-year) was highest in the highest-volume quintile hospitals (FIGURE 3).5 Similarly, quality of care, measured through adherence to various process measures, was also highest in the highest-volume quintile hospitals. Interestingly, in the second-fourth volume quintile hospitals, there was substantial variation in adherence to quality metrics. Among hospitals with higher quality care, an improved survival was noted compared with lower quality care hospitals within the same volume quintile. Survival at high-quality, intermediate-volume hospitals approached that of the high-volume quintile hospitals.5

These findings highlight the importance of quality of care as well as the complex interplay of surgical volume and other factors.20 Many have argued that it may be more appropriate to measure quality of care and past performance and outcomes rather than surgical volume.21

Continue to: Minimum volume standards...

Minimum volume standards

While efforts to regionalize surgical care have gradually evolved, calls have been growing to formalize policies that limit the performance of some procedures to surgeons and centers that meet a minimum volume threshold or standard.21 One such effort, based on consensus from 3 academic hospital systems, was a campaign for hospitals to “Take the Volume Pledge.”21 The campaign’s goal is to encourage health care systems to restrict the performance of 10 procedures to surgeons and hospitals within their systems that meet a minimum volume standard for the given operations.21 In essence, procedures would be restricted for low-volume providers and centers and triaged to higher-volume surgeons and hospitals within a given health care system.21

Proponents of the Volume Pledge argue that it is a relatively straightforward way to align patients and providers to optimize outcomes. The Volume Pledge focuses on larger hospital systems and encourages referral within the given system, thus mitigating competitive and financial concerns about referring patients to outside providers. Those who have argued against the Volume Pledge point out that the volume cut points chosen are somewhat arbitrary, that these policies have the potential to negatively impact rural hospitals and those serving smaller communities, and that quality is a more appropriate metric than volume.22 The Volume Pledge does not include any gynecologic procedures, and to date it has met with only limited success.23

Perhaps more directly applicable to gynecologic surgeons are ongoing national trends to base hospital credentialing on surgical volume. In essence, individual surgeons must demonstrate that they have performed a minimum number of procedures to obtain or retain privileges.24,25 While there is strong evidence of the association between volume and outcomes for some complex surgical procedures, linking volume to credentialing has a number of potential pitfalls. Studies of surgical outcomes based on volume represent average performance, and many low-volume providers have better-than-expected outcomes. Volume measures typically represent recent performance; it is difficult to measure the overall experience of individual surgeons. Similarly, surgical outcomes depend on both the surgeon and the system in which the surgeon operates. It is difficult, if not impossible, to account for differences in the environment in which a surgeon works.25

A study of gynecologic surgeons who performed hysterectomy in New York State demonstrates many of the complexities of volume-based credentialing.26 In a cohort of more than55,000 patients who underwent abdominal hysterectomy, there was a strong association between low surgeon volume and a higher-than-expected rate of complications. If one were to consider limiting privileges to even the lowest-volume providers, there would be a significant impact on the surgical workforce. In this cohort, limiting credentialing to the lowest-volume providers, those who performed only 1 abdominal hysterectomy in the prior year would restrict the privileges of 17.5% of the surgeons in the cohort. Further, in this low-volume cohort that performed only 1 abdominal hysterectomy in the prior year, 69% of the surgeons actually had outcomes that were better than predicted.26 These data highlight not only the difficulty of applying averages to individual surgeons but also the profound impact that policy changes could have on the practice of gynecologic surgery.

Volume-outcomes paradigm discussions continue

The association between higher surgeon and hospital procedural volume for gynecologic surgeries and improved outcomes now has been convincingly demonstrated. With this knowledge, over the last decade the patterns of care for patients undergoing gynecologic surgery have clearly shifted, and these operations are now more commonly being performed by a smaller number of physicians and at fewer hospitals.

While efforts to improve quality are clearly important, many policy interventions, such as regionalization of care, have untoward consequences that must be considered. As we move forward, it will be essential to ensure that there is a robust debate among patients, providers, and policymakers on the merits of public health policies based on the volume-outcomes paradigm. ●

- Birkmeyer JD, Stukel TA, Siewers AE, et al. Surgeon volume and operative mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2117-2127.

- Birkmeyer JD, Siewers AE, Finlayson EV, et al. Hospital volume and surgical mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:11281137.

- Mowat A, Maher C, Ballard E. Surgical outcomes for low-volume vs high-volume surgeons in gynecology surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215:21-33.

- Wallenstein MR, Ananth CV, Kim JH, et al. Effect of surgical volume on outcomes for laparoscopic hysterectomy for benign indications. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119:709-716.

- Wright JD, Chen L, Hou JY, et al. Association of hospital volume and quality of care with survival for ovarian cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:545-553.

- Cliby WA, Powell MA, Al-Hammadi N, et al. Ovarian cancer in the United States: contemporary patterns of care associated with improved survival. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;136:11-17.

- Matsuo K, Shimada M, Yamaguchi S, et al. Association of radical hysterectomy surgical volume and survival for early-stage cervical cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:1086-1098.

- Brennand EA, Quan H. Evaluation of the effect of surgeon’s operative volume and specialty on likelihood of revision after mesh midurethral sling placement. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:1099-1108.

- Ruiz MP, Chen L, Hou JY, et al. Outcomes of hysterectomy performed by very low-volume surgeons. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:981-990.

- Finks JF, Osborne NH, Birkmeyer JD. Trends in hospital volume and operative mortality for high-risk surgery. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:21282137.

- Wright JD, Ruiz MP, Chen L, et al. Changes in surgical volume and outcomes over time for women undergoing hysterectomy for endometrial cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:59-69.

- Wright JD, Chen L, Buskwofie A, et al. Regionalization of care for women with ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2019;154:394-400.

- Fong ZV, Hashimoto DA, Jin G, et al. Simulated volume-based regionalization of complex procedures: impact on spatial access to care. Ann Surg. 2021;274:312-318.

- Knisely A, Huang Y, Melamed A, et al. Effect of regionalization of endometrial cancer care on site of care and patient travel. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;222:58.e1-58.e10.

- Finlayson SR, Birkmeyer JD, Tosteson AN, et al. Patient preferences for location of care: implications for regionalization. Med Care. 1999;37:204-209.

- Shalowitz DI, Nivasch E, Burger RA, et al. Are patients willing to travel for better ovarian cancer care? Gynecol Oncol. 2018;148:42-48.

- Rehmani SS, Liu B, Al-Ayoubi AM, et al. Racial disparity in utilization of high-volume hospitals for surgical treatment of esophageal cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2018;106:346-353.

- Nattinger AB, Rademacher N, McGinley EL, et al. Can regionalization of care reduce socioeconomic disparities in breast cancer survival? Med Care. 2021;59:77-81.

- Auerbach AD, Hilton JF, Maselli J, et al. Shop for quality or volume? Volume, quality, and outcomes of coronary artery bypass surgery. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:696-704.

- Kurlansky PA, Argenziano M, Dunton R, et al. Quality, not volume, determines outcome of coronary artery bypass surgery in a university-based community hospital network. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;143:287-293.

- Urbach DR. Pledging to eliminate low-volume surgery. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1388-1390.

- Blanco BA, Kothari AN, Blackwell RH, et al. “Take the Volume Pledge” may result in disparity in access to care. Surgery. 2017;161:837-845.

- Farjah F, Grau-Sepulveda MV, Gaissert H, et al. Volume Pledge is not associated with better short-term outcomes after lung cancer resection. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:3518-3527.

- Tracy EE, Zephyrin LC, Rosman DA, et al. Credentialing based on surgical volume, physician workforce challenges, and patient access. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122:947-951.

- Statement on credentialing and privileging and volume performance issues. April 1, 2018. American College of Surgeons. Accessed April 10, 2023. https://facs.org/about-acs/statements/credentialing-andprivileging-and-volume-performance-issues/

- Ruiz MP, Chen L, Hou JY, et al. Effect of minimum-volume standards on patient outcomes and surgical practice patterns for hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:1229-1237.

Over the last 3 decades, abundant evidence has demonstrated the association between surgical volume and outcomes. Patients operated on by high-volume surgeons and at high-volume hospitals have superior outcomes.

Surgical volume in gynecology

The association between both hospital and surgeon volume and outcomes has been explored across a number of gynecologic procedures.3 A meta-analysis that included 741,000 patients found that low-volume surgeons had an increased rate of complications overall, a higher rate of intraoperative complications, and a higher rate of postoperative complications compared with high-volume surgeons. While there was no association between volume and mortality overall, when limited to gynecologic oncology studies, low surgeon volume was associated with increased perioperative mortality.3

While these studies demonstrated a statistically significant association between surgeon volume and perioperative outcomes, the magnitude of the effect is modest compared with other higher-risk procedures associated with greater perioperative morbidity. For example, in a large study that examined oncologic and cardiovascular surgery, perioperative mortality in patients who underwent pancreatic resection was reduced from 15% for low-volume surgeons to 5% for high-volume surgeons.1 By contrast, for gynecologic surgery, complications occurred in 97 per 1,000 patients operated on by high-volume surgeons compared with between 114 and 137 per 1,000 for low-volume surgeons. Thus, to avoid 1 in-hospital complication, 30 surgeries performed by low-volume surgeons would need to be moved to high-volume surgeons. For intraoperative complications, 38 patients would need to be moved from low- to high-volume surgeons to prevent 1 such complication.3 In addition to morbidity and mortality, higher surgeon volume is associated with greater use of minimally invasive surgery, a lower likelihood of conversion to laparotomy, and lower costs.3

Similarly, hospital volume also has been associated with outcomes for gynecologic surgery.4 In a report of patients who underwent laparoscopic hysterectomy, the authors found that the complication rate was 18% lower for patients at high- versus low-volume hospitals. In addition, cost was lower at the high-volume centers.4 Like surgeon volume, the magnitude of the differential in outcomes between high- and low-volume hospitals is often modest.4

While most studies have focused on short-term outcomes, surgical volume appears also to be associated with longer-term outcomes. For gynecologic cancer, studies have demonstrated an association between hospital volume and survival for ovarian and cervical cancer.5-7 A large report of centers across the United States found that the 5-year survival rate increased from 39% for patients treated at low-volume centers to 51% at the highest-volume hospitals.5 In urogynecology, surgeon volume has been associated with midurethral sling revision. One study noted that after an individual surgeon performed 50 procedures a year, each additional case was associated with a decline in the rate of sling revision.8 One could argue that these longer-term end points may be the measures that matter most to patients.

Although the magnitude of the association between surgical volume and outcomes in gynecology appears to be relatively modest, outcomes for very-low-volume (VLV) surgeons are substantially worse. An analysis of more than 430,000 patients who underwent hysterectomy compared outcomes between VLV surgeons (characterized as surgeons who performed only 1 hysterectomy in the prior year) and other gynecologic surgeons. The overall complication rate was 32% in VLV surgeons compared with 10% among other surgeons, while the perioperative mortality rate was 2.5% versus 0.2% in the 2 groups, respectively. Likely reflecting changing practice patterns in gynecology, a sizable number of surgeons were classified as VLV physicians.9

Continue to: Public health applications of gynecologic surgical volume...

Public health applications of gynecologic surgical volume