We report the case of a patient who was treated with total hip arthroplasty (THA) for osteoarthritis but was found to have a large acetabular defect caused by pulmonary metastasis. She was promptly referred to our orthopedic oncology clinic for revision because she had experienced no improvement in her symptoms. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 61-year-old woman was referred to us for evaluation of a large right supra-acetabular lesion after undergoing a right THA at another hospital 3 weeks earlier. Preoperative radiographs showed severe osteoarthritis of the right hip but there was no diagnosis of an acetabular lesion in her medical history. During the operation, the surgeon noted poor acetabulum bone quality and sent acetabular reamings for histopathologic analysis, which revealed adenocarcinoma. The arthroplasty was completed in a normal fashion, and the patient was discharged. Postoperatively, her pain did not resolve, and her functional status deteriorated from ambulating with a walker to very limited activity and weight-bearing.

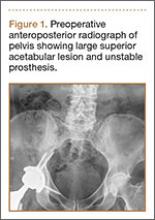

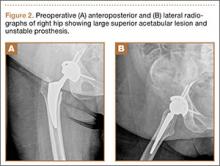

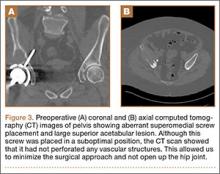

When the patient came to our clinic, we learned she underwent a lobectomy in 2011 for lung cancer resulting from her 40-pack-year history of smoking and had a strong family history of breast cancer. She also had a history of coronary artery disease, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, morbid obesity, and depression. We obtained plain films and a computed tomography (CT) scan that showed a 6.5×7.1×6.5-cm lytic lesion arising from the right acetabulum with cortical penetration and an extraosseous soft-tissue component. Two smaller 10-mm to 12-mm lesions were also found superior and medial to the large lesion. These radiographs and CT images are shown in Figures 1-3.

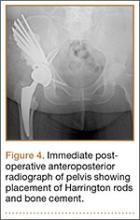

We discussed nonoperative and operative options for treatment with the patient and her family, and she elected to undergo palliative surgical curettage and fixation. Significant bone erosion of the acetabulum and a resultant lack of mechanical support for the acetabular cup were found intraoperatively. An unusual surgical approach was selected in order to minimize morbidity and avoid performing a revision acetabular component if the cup was found to be stable from the standpoint of osseointegration. We approached from the superior side of the ilium, removing the abductors in the superperiosteal fashion extending down from the supra-acetabular ilium, sparing the hip capsule. When the acetabular component was exposed and stressed under fluoroscopy, there was no evidence of loosening. We decided to reconstruct the mechanical defect without revision of the acetabular component and to leave the screw in place. After partial excision of the right supra-acetabular ilium, specimens were sent to pathology. We placed five 4.8-mm and four 4.0-mm threaded Steinmann pins intraosseously through the iliac wing to abut the acetabular cup. In this way, the Steinmann pins provided a stable roof to the cup for weight-bearing and scaffolding for methylmethacrylate cement impregnated with tobramycin. A postoperative radiograph of the patient’s pelvis is shown in Figure 4.

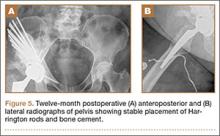

Immediately after her surgery, the patient was bearing weight as tolerated and participating in physical therapy 3 times a day. Two months postoperatively, she was able to walk 1 block with use of a walker, and her pain was controlled with oral pain medication. At her 1-year visit, she was walking without pain for prolonged distances. She had a mild limp but did not need ambulatory aids. She had full range of motion, was able to perform all of her desired activities, and was quite pleased with her result. One-year postoperative radiographs (Figure 5) show stable placement of her acetabular cup with her pins and cement in an unchanged position without recurrence of her destructive lesion. There was no evidence of progression of her cancer, although she had some heterotopic bone in her lateral soft tissues.

Discussion

Many cases have been reported in the literature of metastases to the pelvis and acetabulum; almost 10% of bone metastases are in the pelvis.1 Although many are seen on radiographs, pelvic metastases, especially if they involve the acetabulum, can present with hip pain, decreased joint range of motion, and reduced ambulatory function, all symptoms that are similar to osteoarthritis. While the presence of metastases indicates late-stage disease, many patients still live for years with hip symptoms before succumbing to cancer.1 Palliative treatment initially consists of protected weight-bearing, analgesics, antineoplastic medications ,and radiation. When these first-line therapies fail, palliative operative treatment can be considered, with goals to maintain stability and to preserve mobility, independence, and comfort.2 Patients should be offered this only if there is a reasonable chance that structural stability can be achieved via reconstruction and if the patient will live long enough to realize the functional improvement.3 Harrington4 described patterns of acetabular metastases and surgical treatments in his classic series of 58 patients. For class II and III lesions, he concluded it was necessary to provide additional structural support to the acetabular component of a THA, either in the form of a protrusion shell or with Steinmann pins and bone cement.4 Antiprotrusion cages combined with arthroplasty have been used with modest success for cases where implant bone integration is unlikely.5-6 Several studies since Harrington have shown that constructs with cement reinforced with Steinmann pins can provide reduced pain and improved mobility with a low failure rate for the remainder of the patient’s life.7-9