Safe and efficient advanced surgical skill training is of tremendous importance. With the recent increase in Internet use for medical education, there has been a concomitant increase in video recording of surgical procedures and techniques. Surgical recordings have been used in a variety of ways—as live webcasts for remote participants, as “coaching” opportunities for surgeons evaluating their own performance in the operating room, and even as informational resources for patients about to undergo the same surgery.

Surgical multimedia is being delivered through several different outlets. Many academic conferences and meetings showcase videos of different procedures, and several subspecialty societies (eg, Arthroscopy Association of North America) house archives of technical videos for viewing by members. In addition, the VuMedi website offers videos and allows members to comment on them and interact with the videographers. Surgeons are even posting technique videos on YouTube and other public websites.

A large proportion of surgical multimedia is recorded with conventional high-definition video cameras.1 Besides being able to experience a case at any time and from outside the operating room, the audience can watch from numerous vantage points, angles, and zoom levels. Also, surgeons’ narration can be valuable in helping the audience follow along with the case.

Recording surgical multimedia historically required tight coordination and precise planning by surgeon and videographer. However, innovations in wearable technology now allow surgeons to literally wear video cameras and record procedures as they perform them, in real time—to act as both surgeon and videographer.

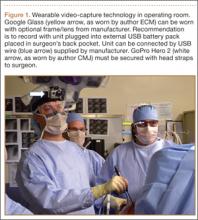

Two such products are Google Glass (Google, Mountain View, California) and GoPro Hero (GoPro, San Mateo, California), both of which allow surgeons to record exactly what they see during procedures (Figure 1). Using a wearable technology for surgical multimedia creation requires a deep familiarity with its capabilities and limitations. In this article, we summarize these products’ similarities and differences and provide a technical overview for using wearable technologies in surgical multimedia creation.

1. Choosing a device

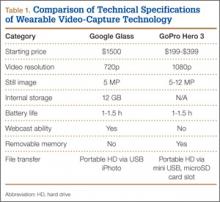

When purchasing either wearable device, several factors must be considered, including budget, possible uses outside the operating room, and possible limitations of the technology (Table 1). At this time, Google Glass is significantly more expensive than GoPro Hero. The Google Glass base unit costs $1500, and the GoPro Hero 3 model costs approximately $200 (higher-priced Hero models are available). Both devices require accessories (eg, portable battery unit, dedicated hard drive).

Device capabilities must also be considered (Table 2). Google Glass consists of both hardware and software. Users can record what is seen and heard through the lens and then use apps to create text and e-mail portals to online gaming, social media, and even golf-course GPS. The app market for Google Glass is nascent but undoubtedly will increase in volume and scope as more users adopt the technology (Google Glass comes with both Bluetooth and Wi-Fi and can function tethered through a smartphone). GoPro is mainly a hardware unit that can record in various settings (it is popular with athletes who want to capture and broadcast their participation in action sports). Newer GoPro Hero versions offer Wi-Fi, which allows streaming of video content to a smartphone or tablet through an app. Having clearly defined goals for a device—as they pertain to use outside the operating room, such as outdoor activities and underwater recording—may help the surgeon decide which product is more suitable. Last, it is important to consider limitations. Google Glass resolution is 720p (1280×720) for video and 5 MP for still images, and GoPro resolution can reach 1080p (1920×1080) for video and 5 MP for stills.

Both devices require purchase of accessories. An external USB battery pack is useful for both devices, as is a password-encrypted hard drive for media storage. Lenswear does not come with the base version of Google Glass and is purchased separately from the company. GoPro users buy micro SD cards (~$50 per 64-GB high-speed transfer card) for storage on the device and may buy lithium-ion batteries as an alternative to the external USB battery pack.

Author Update

In January 2015, Google announced that it was temporarily suspending its “Explorer” program, which allowed individual users to buy and test the device for personal use. However, Google is continuing its development of Glass with health care technology, among other areas of growth and development.2,3

2. Recording a successful surgical video

Unlike a camcorder, which typically is set on a tripod for conventional video recording of surgery, Google Glass and GoPro are intricately linked to the operator. Surgeons must be constantly aware of where they are during surgery and try not to let anything obstruct the camera’s view.