Three-dimensional (3-D) printing is a rapidly evolving technology with both medical and nonmedical applications.1,2 Rapid prototyping involves creating a physical model of human tissue from a 3-D computer-generated rendering.3 The method relies on export of Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM)–based computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) data into standard triangular language (STL) format. Reducing CT or MRI slice thickness increases resolution of the final model.2 Five types of rapid prototyping exist: STL, selective laser sintering, fused deposition modeling, multijet modeling, and 3-D printing.

Most implant manufacturers can produce a 3-D model based on surgeon-provided DICOM images. The ability to produce anatomical models in an office-based setting is a more recent development. Three-dimensional modeling may allow for more accurate and extensive preoperative planning than radiographic examination alone does, and may even allow surgeons to perform procedures as part of preoperative preparation. This can allow for early recognition of unanticipated intraoperative problems or of the need for special techniques and implants that would not have been otherwise available, all of which may ultimately reduce operative time.

The breadth of applications for office-based 3-D prototyping is not well described in the orthopedic surgery literature. In this article, we describe 7 cases of complex orthopedic disorders that were surgically treated after preoperative planning in which use of a 3-D printer allowed for “mock” surgery before the actual procedures. In 3 of the cases, the models were made by the implant manufacturers. Working with these models prompted us to buy a 3-D printer (Fortus 250; Stratasys, Eden Prairie, Minnesota) for in-office use. In the other 4 cases, we used this printer to create our own models. As indicated in the manufacturer’s literature, the printer uses fused deposition modeling, which builds a model layer by layer by heating thermoplastic material to a semi-liquid state and extruding it according to computer-controlled pathways.

We present preoperative images, preoperative 3-D modeling, and intraoperative and postoperative images along with brief case descriptions (Table). The patients provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of these case reports.

Case Reports

Case 1

A 28-year-old woman with a history of spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia presented to our clinic with bilateral hip pain. About 8 years earlier, she had undergone bilateral proximal and distal femoral osteotomies. Her function had initially improved, but over the 2 to 3 years before presentation she began having more pain and stiffness with activity. At time of initial evaluation, she was able to walk only 1 to 2 blocks and had difficulty getting in and out of a car and up out of a seated position.

On physical examination, the patient was 3 feet 10 inches tall and weighed 77 pounds. She ambulated with decreased stance phase on both lower extremities and had developed a significant amount of increased forward pelvic inclination and increased lumbar lordosis. Both hips and thighs had multiple healed scars from prior surgeries and pin tracts. Range of motion (ROM) on both sides was restricted to 85° of flexion, 10° of internal rotation, 15° of external rotation, and 15° of abduction.

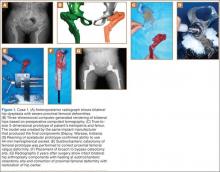

Plain radiographs showed advanced degenerative joint disease (DJD) of both hips with dysplastic acetabuli and evidence of healed osteotomies (Figure 1). Femoral deformities, noted bilaterally, consisted of marked valgus proximally and varus distally. Preoperative CT was used to create a 3-D model of the pelvis and femur. The model was created by the same implant manufacturer that produced the final components (Depuy, Warsaw, Indiana). Corrective femoral osteotomy was performed on the model to allow for design and use of a custom implant, while the modeled pelvis confirmed the ability to reproduce the normal hip center with a 44-mm conventional hemispherical socket.

After surgery, the patient was able to ambulate without a limp and return to work. Her hip ROM was pain-free passively and actively with flexion to 100°, internal rotation to 35°, external rotation to 20°, and abduction to 30°.

Case 2

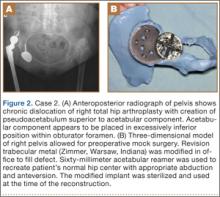

A 48-year-old woman with a history of Crowe IV hip dysplasia presented to our clinic with a chronically dislocated right total hip arthroplasty (THA) (Figure 2). Her initial THA was revised 1 year later because of acetabular component failure. Two years later, she was diagnosed with a deep periprosthetic infection, which was ultimately treated with 2-stage reimplantation. She subsequently dislocated and underwent re-revision of the S-ROM body and stem (DePuy Synthes, Warsaw, Indiana). At a visit after that revision, she was noted to be chronically dislocated, and was sent to our clinic for further management.