User login

Vedolizumab-Induced Acne Fulminans: An Uncommon and Severe Adverse Effect

To the Editor:

Vedolizumab is an innovative monoclonal antibody targeted against the α4β7 integrin that is approved for treatment of moderate to severe ulcerative colitis and Crohn disease refractory to standard treatment.1 Vedolizumab is thought to be gut specific, blocking integrins specific to T lymphocytes destined for the gastrointestinal tract and their interaction with endothelial cells, thereby modulating the adaptive immune system in the gut without systemic immunosuppression.2 It generally is well tolerated, and acne rarely has been reported as an adverse event.3,4 We present a case of acne fulminans without systemic symptoms (AF-WOSS) as a severe side effect of vedolizumab that responded very well to systemic steroids and oral isotretinoin in addition to the discontinuation of treatment.

A 46-year-old obese man presented to our dermatology clinic with a chief complaint of rapidly progressive tender skin lesions. The patient had a long-standing history of severe fistulating and stricturing Crohn disease status post–bowel resection with ileostomy and had recently started treatment with vedolizumab after failing treatment with infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, ustekinumab, and methotrexate. Several weeks after beginning infusions of vedolizumab, the patient began to develop many erythematous papules and pustules on the face, chest (Figure 1), and buttocks that rapidly progressed into painful and coalescing nodules and cysts over the next several months. He was prescribed benzoyl peroxide wash 10% as well as several weeks of oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily with no improvement. The patient denied any other new medications or triggers, fever, chills, bone pain, headache, fatigue, or myalgia. The skin involvement continued to worsen with successive vedolizumab infusions over a period of 8 weeks, which ultimately resulted in cessation of vedolizumab.

Physical examination revealed large, tender, pink, erythematous, and indurated plaques that were heavily studded with pink papules, pustules, and nodules on the cheeks (Figure 2), central chest, and buttocks. A punch biopsy of a pustule on the cheek showed ruptured suppurative folliculitis. The patient subsequently was diagnosed with AF-WOSS.

The patient then completed a 7-day course of sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim followed by a 10-day course of amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, neither of which led to improvement of the lesions. He then was started on an oral prednisone taper (1 mg/kg starting dose) that ultimately totaled 14 weeks in length due to his frequent flares any time prednisone was decreased below 40 mg daily. After 3 weeks on the oral prednisone, the patient was started on 0.3 mg/kg of concomitant oral isotretinoin every other day, which slowly was increased as tolerated until he reached a goal dose of roughly 150 mg/kg, which resolved the acneform papules and pustules and allowed for successful tapering off the prednisone.

Many studies have been published regarding the safety and side-effect profile of vedolizumab, but most do not report acne as an adverse event.3-5 A German cohort study by Baumgart et al3 reported acne as a side effect in 15 of 212 (7.1%) patients but did not classify the severity. Another case report noted nodulocystic acne in a patient receiving vedolizumab for treatment of inflammatory bowel disease; however, this patient responded well to the use of a tetracycline antibiotic and was able to continue therapy with vedolizumab.5 Our patient demonstrated a severe and uncommon case of acne classified as AF-WOSS following initiation of therapy with vedolizumab, which required treatment with systemic steroids plus oral isotretinoin and resulted in cessation of vedolizumab.

As new therapies emerge, it is important to document new or severe adverse effects so providers can choose an appropriate therapy and adequately counsel patients regarding the side effects. Although vedolizumab was thought to have gut-specific action, there is new evidence to suggest that the principal ligand of the α4β7 integrin, mucosal addressin cell adhesion molecule-1, is not only expressed on gut endothelial cells but also on fibroblasts and melanomas, which may provide insight into the observed extraintestinal side effects of vedolizumab.6

- Smith MA, Mohammad RA. Vedolizumab: an α4β7 integrin inhibitor for inflammatory bowel diseases. Ann Pharmacother. 2014;48:1629-1635.

- Singh H, Grewal N, Arora E, et al. Vedolizumab: a novel anti-integrin drug for treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. J Nat Sci Bio Med. 2016;7:4-9.

- Baumgart DC, Bokemeyer B, Drabik A, et al. Vedolizumab induction therapy for inflammatory bowel disease in clinical practice: a nationwide consecutive German cohort study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;43:1090-1102.

- Bye WA, Jairath V, Travis SPL. Systematic review: the safety of vedolizumab for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;46:3-15.

- Gilhooley E, Doherty G, Lally A. Vedolizumab-induced acne in inflammatory bowel disease. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:752-753.

- Leung E, Kanwar RK, Kanwar JR, et al. Mucosal vascular addressin cell adhesion molecule-1 is expressed outside the endothelial lineage on fibroblasts and melanoma cells. Immunol Cell Biol. 2003;81:320-327.

To the Editor:

Vedolizumab is an innovative monoclonal antibody targeted against the α4β7 integrin that is approved for treatment of moderate to severe ulcerative colitis and Crohn disease refractory to standard treatment.1 Vedolizumab is thought to be gut specific, blocking integrins specific to T lymphocytes destined for the gastrointestinal tract and their interaction with endothelial cells, thereby modulating the adaptive immune system in the gut without systemic immunosuppression.2 It generally is well tolerated, and acne rarely has been reported as an adverse event.3,4 We present a case of acne fulminans without systemic symptoms (AF-WOSS) as a severe side effect of vedolizumab that responded very well to systemic steroids and oral isotretinoin in addition to the discontinuation of treatment.

A 46-year-old obese man presented to our dermatology clinic with a chief complaint of rapidly progressive tender skin lesions. The patient had a long-standing history of severe fistulating and stricturing Crohn disease status post–bowel resection with ileostomy and had recently started treatment with vedolizumab after failing treatment with infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, ustekinumab, and methotrexate. Several weeks after beginning infusions of vedolizumab, the patient began to develop many erythematous papules and pustules on the face, chest (Figure 1), and buttocks that rapidly progressed into painful and coalescing nodules and cysts over the next several months. He was prescribed benzoyl peroxide wash 10% as well as several weeks of oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily with no improvement. The patient denied any other new medications or triggers, fever, chills, bone pain, headache, fatigue, or myalgia. The skin involvement continued to worsen with successive vedolizumab infusions over a period of 8 weeks, which ultimately resulted in cessation of vedolizumab.

Physical examination revealed large, tender, pink, erythematous, and indurated plaques that were heavily studded with pink papules, pustules, and nodules on the cheeks (Figure 2), central chest, and buttocks. A punch biopsy of a pustule on the cheek showed ruptured suppurative folliculitis. The patient subsequently was diagnosed with AF-WOSS.

The patient then completed a 7-day course of sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim followed by a 10-day course of amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, neither of which led to improvement of the lesions. He then was started on an oral prednisone taper (1 mg/kg starting dose) that ultimately totaled 14 weeks in length due to his frequent flares any time prednisone was decreased below 40 mg daily. After 3 weeks on the oral prednisone, the patient was started on 0.3 mg/kg of concomitant oral isotretinoin every other day, which slowly was increased as tolerated until he reached a goal dose of roughly 150 mg/kg, which resolved the acneform papules and pustules and allowed for successful tapering off the prednisone.

Many studies have been published regarding the safety and side-effect profile of vedolizumab, but most do not report acne as an adverse event.3-5 A German cohort study by Baumgart et al3 reported acne as a side effect in 15 of 212 (7.1%) patients but did not classify the severity. Another case report noted nodulocystic acne in a patient receiving vedolizumab for treatment of inflammatory bowel disease; however, this patient responded well to the use of a tetracycline antibiotic and was able to continue therapy with vedolizumab.5 Our patient demonstrated a severe and uncommon case of acne classified as AF-WOSS following initiation of therapy with vedolizumab, which required treatment with systemic steroids plus oral isotretinoin and resulted in cessation of vedolizumab.

As new therapies emerge, it is important to document new or severe adverse effects so providers can choose an appropriate therapy and adequately counsel patients regarding the side effects. Although vedolizumab was thought to have gut-specific action, there is new evidence to suggest that the principal ligand of the α4β7 integrin, mucosal addressin cell adhesion molecule-1, is not only expressed on gut endothelial cells but also on fibroblasts and melanomas, which may provide insight into the observed extraintestinal side effects of vedolizumab.6

To the Editor:

Vedolizumab is an innovative monoclonal antibody targeted against the α4β7 integrin that is approved for treatment of moderate to severe ulcerative colitis and Crohn disease refractory to standard treatment.1 Vedolizumab is thought to be gut specific, blocking integrins specific to T lymphocytes destined for the gastrointestinal tract and their interaction with endothelial cells, thereby modulating the adaptive immune system in the gut without systemic immunosuppression.2 It generally is well tolerated, and acne rarely has been reported as an adverse event.3,4 We present a case of acne fulminans without systemic symptoms (AF-WOSS) as a severe side effect of vedolizumab that responded very well to systemic steroids and oral isotretinoin in addition to the discontinuation of treatment.

A 46-year-old obese man presented to our dermatology clinic with a chief complaint of rapidly progressive tender skin lesions. The patient had a long-standing history of severe fistulating and stricturing Crohn disease status post–bowel resection with ileostomy and had recently started treatment with vedolizumab after failing treatment with infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, ustekinumab, and methotrexate. Several weeks after beginning infusions of vedolizumab, the patient began to develop many erythematous papules and pustules on the face, chest (Figure 1), and buttocks that rapidly progressed into painful and coalescing nodules and cysts over the next several months. He was prescribed benzoyl peroxide wash 10% as well as several weeks of oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily with no improvement. The patient denied any other new medications or triggers, fever, chills, bone pain, headache, fatigue, or myalgia. The skin involvement continued to worsen with successive vedolizumab infusions over a period of 8 weeks, which ultimately resulted in cessation of vedolizumab.

Physical examination revealed large, tender, pink, erythematous, and indurated plaques that were heavily studded with pink papules, pustules, and nodules on the cheeks (Figure 2), central chest, and buttocks. A punch biopsy of a pustule on the cheek showed ruptured suppurative folliculitis. The patient subsequently was diagnosed with AF-WOSS.

The patient then completed a 7-day course of sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim followed by a 10-day course of amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, neither of which led to improvement of the lesions. He then was started on an oral prednisone taper (1 mg/kg starting dose) that ultimately totaled 14 weeks in length due to his frequent flares any time prednisone was decreased below 40 mg daily. After 3 weeks on the oral prednisone, the patient was started on 0.3 mg/kg of concomitant oral isotretinoin every other day, which slowly was increased as tolerated until he reached a goal dose of roughly 150 mg/kg, which resolved the acneform papules and pustules and allowed for successful tapering off the prednisone.

Many studies have been published regarding the safety and side-effect profile of vedolizumab, but most do not report acne as an adverse event.3-5 A German cohort study by Baumgart et al3 reported acne as a side effect in 15 of 212 (7.1%) patients but did not classify the severity. Another case report noted nodulocystic acne in a patient receiving vedolizumab for treatment of inflammatory bowel disease; however, this patient responded well to the use of a tetracycline antibiotic and was able to continue therapy with vedolizumab.5 Our patient demonstrated a severe and uncommon case of acne classified as AF-WOSS following initiation of therapy with vedolizumab, which required treatment with systemic steroids plus oral isotretinoin and resulted in cessation of vedolizumab.

As new therapies emerge, it is important to document new or severe adverse effects so providers can choose an appropriate therapy and adequately counsel patients regarding the side effects. Although vedolizumab was thought to have gut-specific action, there is new evidence to suggest that the principal ligand of the α4β7 integrin, mucosal addressin cell adhesion molecule-1, is not only expressed on gut endothelial cells but also on fibroblasts and melanomas, which may provide insight into the observed extraintestinal side effects of vedolizumab.6

- Smith MA, Mohammad RA. Vedolizumab: an α4β7 integrin inhibitor for inflammatory bowel diseases. Ann Pharmacother. 2014;48:1629-1635.

- Singh H, Grewal N, Arora E, et al. Vedolizumab: a novel anti-integrin drug for treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. J Nat Sci Bio Med. 2016;7:4-9.

- Baumgart DC, Bokemeyer B, Drabik A, et al. Vedolizumab induction therapy for inflammatory bowel disease in clinical practice: a nationwide consecutive German cohort study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;43:1090-1102.

- Bye WA, Jairath V, Travis SPL. Systematic review: the safety of vedolizumab for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;46:3-15.

- Gilhooley E, Doherty G, Lally A. Vedolizumab-induced acne in inflammatory bowel disease. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:752-753.

- Leung E, Kanwar RK, Kanwar JR, et al. Mucosal vascular addressin cell adhesion molecule-1 is expressed outside the endothelial lineage on fibroblasts and melanoma cells. Immunol Cell Biol. 2003;81:320-327.

- Smith MA, Mohammad RA. Vedolizumab: an α4β7 integrin inhibitor for inflammatory bowel diseases. Ann Pharmacother. 2014;48:1629-1635.

- Singh H, Grewal N, Arora E, et al. Vedolizumab: a novel anti-integrin drug for treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. J Nat Sci Bio Med. 2016;7:4-9.

- Baumgart DC, Bokemeyer B, Drabik A, et al. Vedolizumab induction therapy for inflammatory bowel disease in clinical practice: a nationwide consecutive German cohort study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;43:1090-1102.

- Bye WA, Jairath V, Travis SPL. Systematic review: the safety of vedolizumab for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;46:3-15.

- Gilhooley E, Doherty G, Lally A. Vedolizumab-induced acne in inflammatory bowel disease. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:752-753.

- Leung E, Kanwar RK, Kanwar JR, et al. Mucosal vascular addressin cell adhesion molecule-1 is expressed outside the endothelial lineage on fibroblasts and melanoma cells. Immunol Cell Biol. 2003;81:320-327.

Practice Points

- Vedolizumab, a monoclonal antibody for the treatment of refractory inflammatory bowel disease, was found to cause acne fulminans without systemic symptoms.

- Vedolizumab previously was believed to be a gut-limited immune modulator.

- Off-target cutaneous effects may indicate wider expression of the target integrin of vedolizumab and should be recognized as the drug becomes more widely used.

Consider the mnemonic ‘CLEAR’ when counseling acne patients

to use when treating this group of patients.

During a presentation at Medscape Live’s annual Coastal Dermatology Symposium, Dr. Harper, who practices at Dermatology and Skin Care of Birmingham, Ala., elaborated on the mnemonic, as follows:

C: Communicate expectations. “I look right at the acne patient and say, ‘I know you don’t just want to be better; I know you want to be clear,’ ” she said at the meeting. “ ‘That’s my goal for you, too. That may take us more than one visit and more than one treatment, but I am on your team, and that’s what we’re shooting for.’ If you don’t communicate that, they’re going to think that their acne is not that important to you.”

L: Listen for clues to customize the patient’s treatment. “We’re quick to say, ‘my patients don’t do what I recommend,’ or ‘they didn’t do what the last doctor recommended,’ ” Dr. Harper said. “Sometimes that is true, but there may be a reason why. Maybe the medication was too expensive. Maybe it was bleaching their fabrics. Maybe the regimen was too complex. Listen for opportunities to make adjustments to get their acne closer to clear.”

E: Treat early to improve quality of life and to decrease the risk of scarring. “I have a laser in my practice that is good at treating acne scarring,” she said. “Do I ever look at my patient and say, ‘don’t worry about those scars; I can make them go away?’ No. I look at them and say, ‘we can maybe make this 40% better,’ something like that. We have to prevent acne scars, because we’re not good at treating them.”

A: Treat aggressively with more combination therapies, more hormonal therapies, more isotretinoin, and perhaps more prior authorizations. She characterized the effort to obtain a prior authorization as “our megaphone back to insurance companies that says, ‘we think it is worth taking the time to do this prior authorization because the acne patient will benefit.’ ”

R: Don’t resist isotretinoin. Dr. Harper, who began practicing dermatology more than 20 years ago, said that over time, she has gradually prescribed more isotretinoin for her patients with acne. “It’s not a first-line [treatment], but I’m not afraid of it. If I can’t get somebody clear on other oral or topical treatments, we are going to try isotretinoin.”

The goal of acne treatment, she added, is to affect four key aspects of pathogenesis: follicular epithelial hyperproliferation, inflammation, Cutibacterium acnes (C. acnes), and sebum. “That’s what we’re always shooting for,” she said.

Dr. Harper is a past president of the American Acne & Rosacea Society. She disclosed that she serves as an advisor or consultant for Almirall, BioPharmX, Cassiopeia, Cutanea, Cutera, Dermira, EPI, Galderma, LaRoche-Posay, Ortho, Vyne, Sol Gel, and Sun. She also serves as a speaker or member of a speaker’s bureau for Almirall, EPI, Galderma, Ortho, and Vyne.

Medscape Live and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

to use when treating this group of patients.

During a presentation at Medscape Live’s annual Coastal Dermatology Symposium, Dr. Harper, who practices at Dermatology and Skin Care of Birmingham, Ala., elaborated on the mnemonic, as follows:

C: Communicate expectations. “I look right at the acne patient and say, ‘I know you don’t just want to be better; I know you want to be clear,’ ” she said at the meeting. “ ‘That’s my goal for you, too. That may take us more than one visit and more than one treatment, but I am on your team, and that’s what we’re shooting for.’ If you don’t communicate that, they’re going to think that their acne is not that important to you.”

L: Listen for clues to customize the patient’s treatment. “We’re quick to say, ‘my patients don’t do what I recommend,’ or ‘they didn’t do what the last doctor recommended,’ ” Dr. Harper said. “Sometimes that is true, but there may be a reason why. Maybe the medication was too expensive. Maybe it was bleaching their fabrics. Maybe the regimen was too complex. Listen for opportunities to make adjustments to get their acne closer to clear.”

E: Treat early to improve quality of life and to decrease the risk of scarring. “I have a laser in my practice that is good at treating acne scarring,” she said. “Do I ever look at my patient and say, ‘don’t worry about those scars; I can make them go away?’ No. I look at them and say, ‘we can maybe make this 40% better,’ something like that. We have to prevent acne scars, because we’re not good at treating them.”

A: Treat aggressively with more combination therapies, more hormonal therapies, more isotretinoin, and perhaps more prior authorizations. She characterized the effort to obtain a prior authorization as “our megaphone back to insurance companies that says, ‘we think it is worth taking the time to do this prior authorization because the acne patient will benefit.’ ”

R: Don’t resist isotretinoin. Dr. Harper, who began practicing dermatology more than 20 years ago, said that over time, she has gradually prescribed more isotretinoin for her patients with acne. “It’s not a first-line [treatment], but I’m not afraid of it. If I can’t get somebody clear on other oral or topical treatments, we are going to try isotretinoin.”

The goal of acne treatment, she added, is to affect four key aspects of pathogenesis: follicular epithelial hyperproliferation, inflammation, Cutibacterium acnes (C. acnes), and sebum. “That’s what we’re always shooting for,” she said.

Dr. Harper is a past president of the American Acne & Rosacea Society. She disclosed that she serves as an advisor or consultant for Almirall, BioPharmX, Cassiopeia, Cutanea, Cutera, Dermira, EPI, Galderma, LaRoche-Posay, Ortho, Vyne, Sol Gel, and Sun. She also serves as a speaker or member of a speaker’s bureau for Almirall, EPI, Galderma, Ortho, and Vyne.

Medscape Live and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

to use when treating this group of patients.

During a presentation at Medscape Live’s annual Coastal Dermatology Symposium, Dr. Harper, who practices at Dermatology and Skin Care of Birmingham, Ala., elaborated on the mnemonic, as follows:

C: Communicate expectations. “I look right at the acne patient and say, ‘I know you don’t just want to be better; I know you want to be clear,’ ” she said at the meeting. “ ‘That’s my goal for you, too. That may take us more than one visit and more than one treatment, but I am on your team, and that’s what we’re shooting for.’ If you don’t communicate that, they’re going to think that their acne is not that important to you.”

L: Listen for clues to customize the patient’s treatment. “We’re quick to say, ‘my patients don’t do what I recommend,’ or ‘they didn’t do what the last doctor recommended,’ ” Dr. Harper said. “Sometimes that is true, but there may be a reason why. Maybe the medication was too expensive. Maybe it was bleaching their fabrics. Maybe the regimen was too complex. Listen for opportunities to make adjustments to get their acne closer to clear.”

E: Treat early to improve quality of life and to decrease the risk of scarring. “I have a laser in my practice that is good at treating acne scarring,” she said. “Do I ever look at my patient and say, ‘don’t worry about those scars; I can make them go away?’ No. I look at them and say, ‘we can maybe make this 40% better,’ something like that. We have to prevent acne scars, because we’re not good at treating them.”

A: Treat aggressively with more combination therapies, more hormonal therapies, more isotretinoin, and perhaps more prior authorizations. She characterized the effort to obtain a prior authorization as “our megaphone back to insurance companies that says, ‘we think it is worth taking the time to do this prior authorization because the acne patient will benefit.’ ”

R: Don’t resist isotretinoin. Dr. Harper, who began practicing dermatology more than 20 years ago, said that over time, she has gradually prescribed more isotretinoin for her patients with acne. “It’s not a first-line [treatment], but I’m not afraid of it. If I can’t get somebody clear on other oral or topical treatments, we are going to try isotretinoin.”

The goal of acne treatment, she added, is to affect four key aspects of pathogenesis: follicular epithelial hyperproliferation, inflammation, Cutibacterium acnes (C. acnes), and sebum. “That’s what we’re always shooting for,” she said.

Dr. Harper is a past president of the American Acne & Rosacea Society. She disclosed that she serves as an advisor or consultant for Almirall, BioPharmX, Cassiopeia, Cutanea, Cutera, Dermira, EPI, Galderma, LaRoche-Posay, Ortho, Vyne, Sol Gel, and Sun. She also serves as a speaker or member of a speaker’s bureau for Almirall, EPI, Galderma, Ortho, and Vyne.

Medscape Live and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

FROM MEDSCAPE LIVE COASTAL DERM

Expert calls for thoughtful approach to curbing costs in dermatology

PORTLAND, ORE. – About 10 years ago when Arash Mostaghimi, MD, MPA, MPH, became an attending physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, he noticed that some of his dermatology colleagues checked the potassium levels religiously in their female patients taking spironolactone, while others never did.

“It led to this question: Dr. Mostaghimi, director of the dermatology inpatient service at Brigham and Women’s, said at the annual meeting of the Pacific Dermatologic Association.

To find out, he and his colleagues reviewed 1,802 serum potassium measurements in a study of healthy young women with no known health conditions who were taking spironolactone, published in 2015. They discovered that 13 of those tests suggested mild hyperkalemia, defined as a level greater than 5.0 mEq/L. Of these, six were rechecked and were normal; no action was taken in the other seven patients.

“This led us to conclude that we spent $78,000 at our institution on testing that did not appear to yield clinically significant information for these patients, and that routine potassium monitoring is unnecessary for most women taking spironolactone for acne,” he said. Their findings have been validated “in many cohorts of data,” he added.

The study serves as an example of efforts dermatologists can take to curb unnecessary costs within the field to be “appropriate stewards of resources,” he continued. “We have to think about the ratio of benefit over cost. It’s not just about the cost, it’s about what you’re getting for the amount of money that you’re spending. The idea of this is not restricting or not giving people medications or access to things that they need. The idea is to do it in a thoughtful way that works across the population.”

Value thresholds

Determining the value thresholds of a particular medicine or procedure is also essential to good dermatology practice. To illustrate, Dr. Mostaghimi cited a prospective cohort study that compared treatment patterns and clinical outcomes in 1,536 consecutive patients with nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC) with and without limited life expectancy. More than two-thirds of the NMSCs (69%) were treated surgically. After adjusting for tumor and patient characteristics, the researchers found that 43% of patients with low life expectancy died within 5 years, but not from NMSC.

“Does that mean we shouldn’t do surgery for NMSC patients with low life expectancy?” he asked. “Should we do it less? Should we let the patients decide? It’s complicated. As a society, we have to decide what’s worth doing and what’s not worth doing,” he said. “What about old diseases with new treatments, like alopecia areata? Is alopecia areata a cosmetic condition? Dermatologists and patients wouldn’t classify it that way, but many insurers do. How do you negotiate that?”

In 2013, the American Academy of Dermatology identified 10 evidence-based recommendations that can support conversations between patients and dermatologists about treatments, tests, and procedures that may not be necessary. One of the recommendations was not to prescribe oral antifungal therapy for suspected nail fungus without confirmation of fungal infection.

“If a clinician thinks a patient has onychomycosis, he or she is usually right,” Dr. Mostaghimi said. “But what’s the added cost/benefit of performing a KOH followed by PAS testing if negative or performing a PAS test directly versus just treating the patient?”

In 2006, he and his colleagues published the results of a decision analysis to address these questions. They determined that the costs of testing to avoid one case of clinically apparent liver injury with terbinafine treatment was $18.2-$43.7 million for the KOH screening pathway and $37.6 to $90.2 million for the PAS testing pathway.

“Is that worth it?” he asked. “Would we get more value for spending the money elsewhere? In this case, the answer is most likely yes.”

Isotretinoin lab testing

Translating research into recommendations and standards of care is one way to help curb costs in dermatology. As an example, he cited lab monitoring for patients treated with isotretinoin for acne.

“There have been a number of papers over the years that have suggested that the number of labs we do is excessive, that the value that they provide is low, and that abnormal results do not impact our decision-making,” Dr. Mostaghimi said. “Do some patients on isotretinoin get mildly elevated [liver function tests] and hypertriglyceridemia? Yes, that happens. Does it matter? Nothing has demonstrated that it matters. Does it matter that an 18-year-old has high triglycerides for 6 months? Rarely, if ever.”

To promote a new approach, he and a panel of acne experts from five continents performed a Delphi consensus study. Based on their consensus, they proposed a simple approach: For “generally healthy patients without underlying abnormalities or preexisting conditions warranting further investigation,” check ALT and triglycerides prior to initiating isotretinoin. Then start isotretinoin.

“At the peak dose, recheck ALT and triglycerides – this might be at month 2,” Dr. Mostaghimi said. “Other people wait a little bit longer. No labs are required once treatment is complete. Of course, adjust this approach based on your assessment of the patient in front of you. None of these recommendations should replace your clinical judgment and intuition.”

He proposed a new paradigm where dermatologists can ask themselves three questions for every patient they see: Why is this intervention or test being done? Why is it being done in this patient? And why do it at that time? “If we think this way, we can identify some inconsistencies in our own thinking and opportunities for improvement,” he said.

Dr. Mostaghimi reported that he is a consultant to Pfizer, Concert, Lilly, and Bioniz. He is also an advisor to Him & Hers Cosmetics and Digital Diagnostics and is an associate editor for JAMA Dermatology.

PORTLAND, ORE. – About 10 years ago when Arash Mostaghimi, MD, MPA, MPH, became an attending physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, he noticed that some of his dermatology colleagues checked the potassium levels religiously in their female patients taking spironolactone, while others never did.

“It led to this question: Dr. Mostaghimi, director of the dermatology inpatient service at Brigham and Women’s, said at the annual meeting of the Pacific Dermatologic Association.

To find out, he and his colleagues reviewed 1,802 serum potassium measurements in a study of healthy young women with no known health conditions who were taking spironolactone, published in 2015. They discovered that 13 of those tests suggested mild hyperkalemia, defined as a level greater than 5.0 mEq/L. Of these, six were rechecked and were normal; no action was taken in the other seven patients.

“This led us to conclude that we spent $78,000 at our institution on testing that did not appear to yield clinically significant information for these patients, and that routine potassium monitoring is unnecessary for most women taking spironolactone for acne,” he said. Their findings have been validated “in many cohorts of data,” he added.

The study serves as an example of efforts dermatologists can take to curb unnecessary costs within the field to be “appropriate stewards of resources,” he continued. “We have to think about the ratio of benefit over cost. It’s not just about the cost, it’s about what you’re getting for the amount of money that you’re spending. The idea of this is not restricting or not giving people medications or access to things that they need. The idea is to do it in a thoughtful way that works across the population.”

Value thresholds

Determining the value thresholds of a particular medicine or procedure is also essential to good dermatology practice. To illustrate, Dr. Mostaghimi cited a prospective cohort study that compared treatment patterns and clinical outcomes in 1,536 consecutive patients with nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC) with and without limited life expectancy. More than two-thirds of the NMSCs (69%) were treated surgically. After adjusting for tumor and patient characteristics, the researchers found that 43% of patients with low life expectancy died within 5 years, but not from NMSC.

“Does that mean we shouldn’t do surgery for NMSC patients with low life expectancy?” he asked. “Should we do it less? Should we let the patients decide? It’s complicated. As a society, we have to decide what’s worth doing and what’s not worth doing,” he said. “What about old diseases with new treatments, like alopecia areata? Is alopecia areata a cosmetic condition? Dermatologists and patients wouldn’t classify it that way, but many insurers do. How do you negotiate that?”

In 2013, the American Academy of Dermatology identified 10 evidence-based recommendations that can support conversations between patients and dermatologists about treatments, tests, and procedures that may not be necessary. One of the recommendations was not to prescribe oral antifungal therapy for suspected nail fungus without confirmation of fungal infection.

“If a clinician thinks a patient has onychomycosis, he or she is usually right,” Dr. Mostaghimi said. “But what’s the added cost/benefit of performing a KOH followed by PAS testing if negative or performing a PAS test directly versus just treating the patient?”

In 2006, he and his colleagues published the results of a decision analysis to address these questions. They determined that the costs of testing to avoid one case of clinically apparent liver injury with terbinafine treatment was $18.2-$43.7 million for the KOH screening pathway and $37.6 to $90.2 million for the PAS testing pathway.

“Is that worth it?” he asked. “Would we get more value for spending the money elsewhere? In this case, the answer is most likely yes.”

Isotretinoin lab testing

Translating research into recommendations and standards of care is one way to help curb costs in dermatology. As an example, he cited lab monitoring for patients treated with isotretinoin for acne.

“There have been a number of papers over the years that have suggested that the number of labs we do is excessive, that the value that they provide is low, and that abnormal results do not impact our decision-making,” Dr. Mostaghimi said. “Do some patients on isotretinoin get mildly elevated [liver function tests] and hypertriglyceridemia? Yes, that happens. Does it matter? Nothing has demonstrated that it matters. Does it matter that an 18-year-old has high triglycerides for 6 months? Rarely, if ever.”

To promote a new approach, he and a panel of acne experts from five continents performed a Delphi consensus study. Based on their consensus, they proposed a simple approach: For “generally healthy patients without underlying abnormalities or preexisting conditions warranting further investigation,” check ALT and triglycerides prior to initiating isotretinoin. Then start isotretinoin.

“At the peak dose, recheck ALT and triglycerides – this might be at month 2,” Dr. Mostaghimi said. “Other people wait a little bit longer. No labs are required once treatment is complete. Of course, adjust this approach based on your assessment of the patient in front of you. None of these recommendations should replace your clinical judgment and intuition.”

He proposed a new paradigm where dermatologists can ask themselves three questions for every patient they see: Why is this intervention or test being done? Why is it being done in this patient? And why do it at that time? “If we think this way, we can identify some inconsistencies in our own thinking and opportunities for improvement,” he said.

Dr. Mostaghimi reported that he is a consultant to Pfizer, Concert, Lilly, and Bioniz. He is also an advisor to Him & Hers Cosmetics and Digital Diagnostics and is an associate editor for JAMA Dermatology.

PORTLAND, ORE. – About 10 years ago when Arash Mostaghimi, MD, MPA, MPH, became an attending physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, he noticed that some of his dermatology colleagues checked the potassium levels religiously in their female patients taking spironolactone, while others never did.

“It led to this question: Dr. Mostaghimi, director of the dermatology inpatient service at Brigham and Women’s, said at the annual meeting of the Pacific Dermatologic Association.

To find out, he and his colleagues reviewed 1,802 serum potassium measurements in a study of healthy young women with no known health conditions who were taking spironolactone, published in 2015. They discovered that 13 of those tests suggested mild hyperkalemia, defined as a level greater than 5.0 mEq/L. Of these, six were rechecked and were normal; no action was taken in the other seven patients.

“This led us to conclude that we spent $78,000 at our institution on testing that did not appear to yield clinically significant information for these patients, and that routine potassium monitoring is unnecessary for most women taking spironolactone for acne,” he said. Their findings have been validated “in many cohorts of data,” he added.

The study serves as an example of efforts dermatologists can take to curb unnecessary costs within the field to be “appropriate stewards of resources,” he continued. “We have to think about the ratio of benefit over cost. It’s not just about the cost, it’s about what you’re getting for the amount of money that you’re spending. The idea of this is not restricting or not giving people medications or access to things that they need. The idea is to do it in a thoughtful way that works across the population.”

Value thresholds

Determining the value thresholds of a particular medicine or procedure is also essential to good dermatology practice. To illustrate, Dr. Mostaghimi cited a prospective cohort study that compared treatment patterns and clinical outcomes in 1,536 consecutive patients with nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC) with and without limited life expectancy. More than two-thirds of the NMSCs (69%) were treated surgically. After adjusting for tumor and patient characteristics, the researchers found that 43% of patients with low life expectancy died within 5 years, but not from NMSC.

“Does that mean we shouldn’t do surgery for NMSC patients with low life expectancy?” he asked. “Should we do it less? Should we let the patients decide? It’s complicated. As a society, we have to decide what’s worth doing and what’s not worth doing,” he said. “What about old diseases with new treatments, like alopecia areata? Is alopecia areata a cosmetic condition? Dermatologists and patients wouldn’t classify it that way, but many insurers do. How do you negotiate that?”

In 2013, the American Academy of Dermatology identified 10 evidence-based recommendations that can support conversations between patients and dermatologists about treatments, tests, and procedures that may not be necessary. One of the recommendations was not to prescribe oral antifungal therapy for suspected nail fungus without confirmation of fungal infection.

“If a clinician thinks a patient has onychomycosis, he or she is usually right,” Dr. Mostaghimi said. “But what’s the added cost/benefit of performing a KOH followed by PAS testing if negative or performing a PAS test directly versus just treating the patient?”

In 2006, he and his colleagues published the results of a decision analysis to address these questions. They determined that the costs of testing to avoid one case of clinically apparent liver injury with terbinafine treatment was $18.2-$43.7 million for the KOH screening pathway and $37.6 to $90.2 million for the PAS testing pathway.

“Is that worth it?” he asked. “Would we get more value for spending the money elsewhere? In this case, the answer is most likely yes.”

Isotretinoin lab testing

Translating research into recommendations and standards of care is one way to help curb costs in dermatology. As an example, he cited lab monitoring for patients treated with isotretinoin for acne.

“There have been a number of papers over the years that have suggested that the number of labs we do is excessive, that the value that they provide is low, and that abnormal results do not impact our decision-making,” Dr. Mostaghimi said. “Do some patients on isotretinoin get mildly elevated [liver function tests] and hypertriglyceridemia? Yes, that happens. Does it matter? Nothing has demonstrated that it matters. Does it matter that an 18-year-old has high triglycerides for 6 months? Rarely, if ever.”

To promote a new approach, he and a panel of acne experts from five continents performed a Delphi consensus study. Based on their consensus, they proposed a simple approach: For “generally healthy patients without underlying abnormalities or preexisting conditions warranting further investigation,” check ALT and triglycerides prior to initiating isotretinoin. Then start isotretinoin.

“At the peak dose, recheck ALT and triglycerides – this might be at month 2,” Dr. Mostaghimi said. “Other people wait a little bit longer. No labs are required once treatment is complete. Of course, adjust this approach based on your assessment of the patient in front of you. None of these recommendations should replace your clinical judgment and intuition.”

He proposed a new paradigm where dermatologists can ask themselves three questions for every patient they see: Why is this intervention or test being done? Why is it being done in this patient? And why do it at that time? “If we think this way, we can identify some inconsistencies in our own thinking and opportunities for improvement,” he said.

Dr. Mostaghimi reported that he is a consultant to Pfizer, Concert, Lilly, and Bioniz. He is also an advisor to Him & Hers Cosmetics and Digital Diagnostics and is an associate editor for JAMA Dermatology.

AT PDA 2022

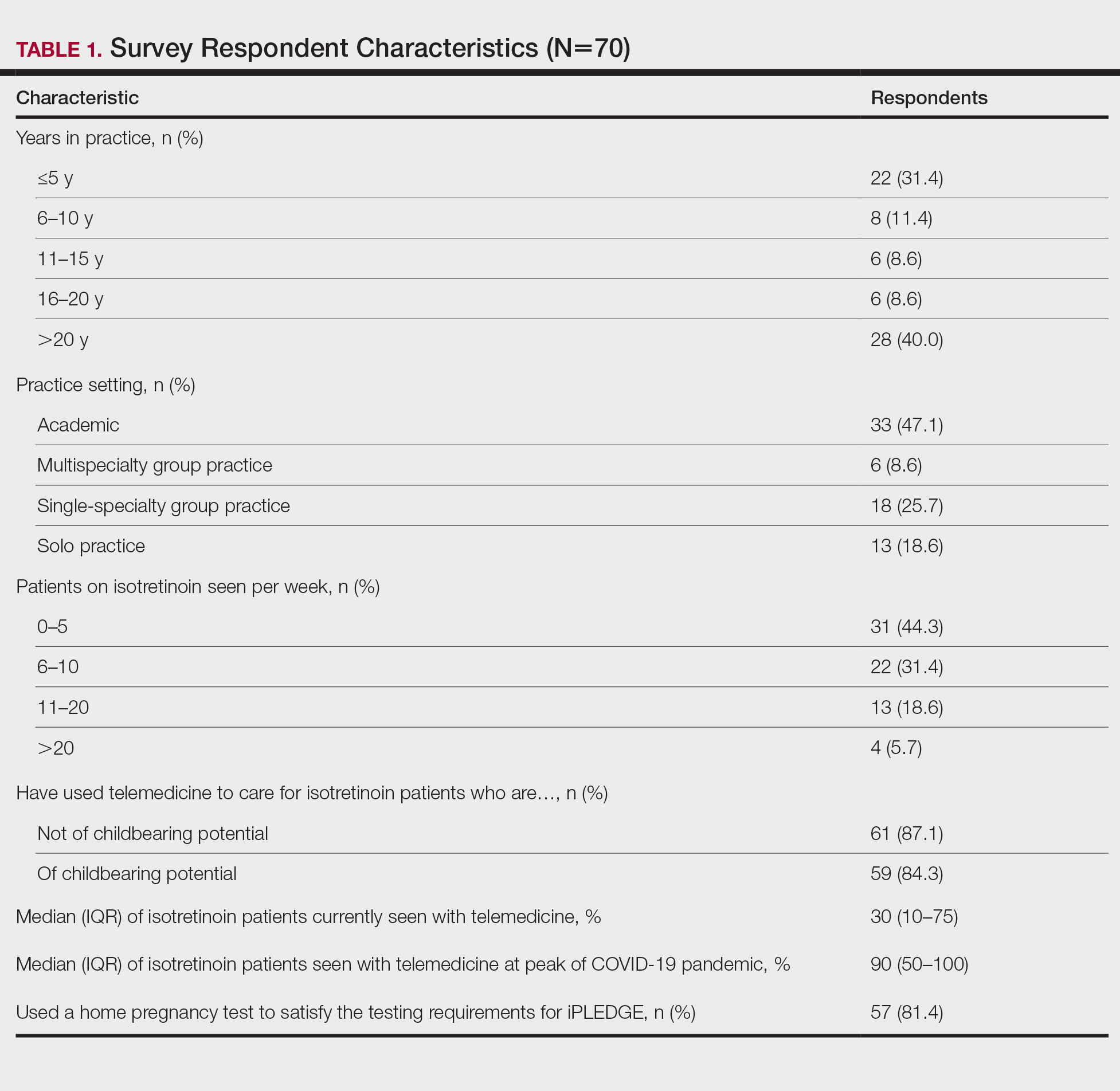

Isotretinoin prescribers need better education on emergency contraception

, in a survey of 57 clinicians.

Pregnancies among patients on isotretinoin have declined since the iPLEDGE risk management program was introduced in 2005, but from 2011 to 2017, 210 to 310 pregnancies were reported to the Food and Drug Administration every year, wrote Catherine E. Smiley of Penn State University, Hershey, Pa., and coauthors Melissa Butt, DrPH, and Andrea L. Zaenglein, MD, of Penn State.

For patients on isotretinoin, EC “becomes critical when abstinence fails or contraception is not used properly,” but EC merits only a brief mention in iPLEDGE materials for patients and providers, they noted.

Patients on isotretinoin who choose abstinence as their form of birth control are the group at greatest risk for pregnancy, Dr. Zaenglein, professor of dermatology and pediatric dermatology, Penn State University, said in an interview. “However, the iPLEDGE program fails to educate patients adequately on emergency contraception,” she explained.

To assess pediatric dermatologists’ understanding of EC and their contraception counseling practices for isotretinoin patients, the researchers surveyed 57 pediatric dermatologists who prescribed isotretinoin as part of their practices. The findings were published in Pediatric Dermatology.Respondents included 53 practicing dermatologists, 2 residents, and 2 fellows. Approximately one-third (31.6%) had been in practice for 6-10 years, almost 23% had been in practice for 3-5 years, and almost 20% had been in practice for 21 or more years. Almost two-thirds practiced pediatric dermatology only.

Overall, 58% of the respondents strongly agreed that they provided contraception counseling to patients at their initial visit for isotretinoin, but only 7% and 3.5% reported providing EC counseling at initial and follow-up visits, respectively. More than half (58%) said they did not counsel patients on the side effects of EC.

As for provider education, 7.1% of respondents said they had received formal education on EC counseling, 25% reported receiving informal education on EC counseling, and 68% said they received no education on EC counseling.

A total of 32% of respondents said they were at least somewhat confident in how to obtain EC in their state.

EC is an effective form of contraception if used after unprotected intercourse, and discounts can reduce the price to as low as $9.69, the researchers wrote in their discussion. “Given that most providers in this study did not receive formal education on EC, and most do not provide EC counseling to their patients of reproductive potential on isotretinoin, EC education should be a core competency in dermatology residency education on isotretinoin prescribing,” the researchers noted. In addition, EC counseling in the iPLEDGE program should be improved by including more information in education materials and reminding patients that EC is an option, they said.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the small sample size and the multiple-choice format that prevented respondents to share rationales for their responses, the researchers noted.

However, the results highlight the need to improve EC education among pediatric dermatologists to better inform patients considering isotretinoin, especially those choosing abstinence as a method of birth control, they emphasized.

“This study is very important at this specific time for two reasons,” Dr. Zaenglein said in an interview. “The first is that with the recent disastrous rollout of the new iPLEDGE changes, there have been many calls to reform the REMS program. For the first time in the 22-year history of the program, the isotretinoin manufacturers, who manage the iPLEDGE program as an unidentified group (the IPMG), have been forced by the FDA to meet with the AAD iPLEDGE Task Force,” said Dr. Zaenglein, a member of the task force.

“The task force is currently advocating for common sense changes to iPLEDGE and I think enhancing education on emergency contraception is vital to the goal of the program, stated as ‘to manage the risk of isotretinoin’s teratogenicity and to minimize fetal exposure,’ ” she added. For many patients who previously became pregnant on isotretinoin, Plan B, an over-the-counter, FDA-approved form of contraception, might have prevented that pregnancy if the patients received adequate education on EC, she said.

The current study is especially relevant now, said Dr. Zaenglein. “With the reversal of Roe v. Wade, access to abortion is restricted or completely banned in many states, which makes educating our patients on how to prevent pregnancy even more important.”

Dr. Zaenglein said she was “somewhat surprised” by how many respondents were not educating their isotretinoin patients on EC. “However, these results follow a known trend among dermatologists. Only 50% of dermatologists prescribe oral contraceptives for acne, despite its being an FDA-approved treatment for the most common dermatologic condition we see in adolescents and young adults,” she noted.

“In general, dermatologists, and subsequently dermatology residents, are poorly educated on issues of reproductive health and how they are relevant to dermatologic care,” she added.

Dr. Zaenglein’s take home message: “Dermatologists should educate all patients of childbearing potential taking isotretinoin on how to acquire and use emergency contraception at every visit.” As for additional research, she said that since the study was conducted with pediatric dermatologists, “it would be very interesting to see if general dermatologists had the same lack of comfort in educating patients on emergency contraception and what their standard counseling practices are.”

The study received no outside funding. Dr. Zaenglein is a member of the AAD’s iPLEDGE Work Group and serves as an editor-in-chief of Pediatric Dermatology.

, in a survey of 57 clinicians.

Pregnancies among patients on isotretinoin have declined since the iPLEDGE risk management program was introduced in 2005, but from 2011 to 2017, 210 to 310 pregnancies were reported to the Food and Drug Administration every year, wrote Catherine E. Smiley of Penn State University, Hershey, Pa., and coauthors Melissa Butt, DrPH, and Andrea L. Zaenglein, MD, of Penn State.

For patients on isotretinoin, EC “becomes critical when abstinence fails or contraception is not used properly,” but EC merits only a brief mention in iPLEDGE materials for patients and providers, they noted.

Patients on isotretinoin who choose abstinence as their form of birth control are the group at greatest risk for pregnancy, Dr. Zaenglein, professor of dermatology and pediatric dermatology, Penn State University, said in an interview. “However, the iPLEDGE program fails to educate patients adequately on emergency contraception,” she explained.

To assess pediatric dermatologists’ understanding of EC and their contraception counseling practices for isotretinoin patients, the researchers surveyed 57 pediatric dermatologists who prescribed isotretinoin as part of their practices. The findings were published in Pediatric Dermatology.Respondents included 53 practicing dermatologists, 2 residents, and 2 fellows. Approximately one-third (31.6%) had been in practice for 6-10 years, almost 23% had been in practice for 3-5 years, and almost 20% had been in practice for 21 or more years. Almost two-thirds practiced pediatric dermatology only.

Overall, 58% of the respondents strongly agreed that they provided contraception counseling to patients at their initial visit for isotretinoin, but only 7% and 3.5% reported providing EC counseling at initial and follow-up visits, respectively. More than half (58%) said they did not counsel patients on the side effects of EC.

As for provider education, 7.1% of respondents said they had received formal education on EC counseling, 25% reported receiving informal education on EC counseling, and 68% said they received no education on EC counseling.

A total of 32% of respondents said they were at least somewhat confident in how to obtain EC in their state.

EC is an effective form of contraception if used after unprotected intercourse, and discounts can reduce the price to as low as $9.69, the researchers wrote in their discussion. “Given that most providers in this study did not receive formal education on EC, and most do not provide EC counseling to their patients of reproductive potential on isotretinoin, EC education should be a core competency in dermatology residency education on isotretinoin prescribing,” the researchers noted. In addition, EC counseling in the iPLEDGE program should be improved by including more information in education materials and reminding patients that EC is an option, they said.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the small sample size and the multiple-choice format that prevented respondents to share rationales for their responses, the researchers noted.

However, the results highlight the need to improve EC education among pediatric dermatologists to better inform patients considering isotretinoin, especially those choosing abstinence as a method of birth control, they emphasized.

“This study is very important at this specific time for two reasons,” Dr. Zaenglein said in an interview. “The first is that with the recent disastrous rollout of the new iPLEDGE changes, there have been many calls to reform the REMS program. For the first time in the 22-year history of the program, the isotretinoin manufacturers, who manage the iPLEDGE program as an unidentified group (the IPMG), have been forced by the FDA to meet with the AAD iPLEDGE Task Force,” said Dr. Zaenglein, a member of the task force.

“The task force is currently advocating for common sense changes to iPLEDGE and I think enhancing education on emergency contraception is vital to the goal of the program, stated as ‘to manage the risk of isotretinoin’s teratogenicity and to minimize fetal exposure,’ ” she added. For many patients who previously became pregnant on isotretinoin, Plan B, an over-the-counter, FDA-approved form of contraception, might have prevented that pregnancy if the patients received adequate education on EC, she said.

The current study is especially relevant now, said Dr. Zaenglein. “With the reversal of Roe v. Wade, access to abortion is restricted or completely banned in many states, which makes educating our patients on how to prevent pregnancy even more important.”

Dr. Zaenglein said she was “somewhat surprised” by how many respondents were not educating their isotretinoin patients on EC. “However, these results follow a known trend among dermatologists. Only 50% of dermatologists prescribe oral contraceptives for acne, despite its being an FDA-approved treatment for the most common dermatologic condition we see in adolescents and young adults,” she noted.

“In general, dermatologists, and subsequently dermatology residents, are poorly educated on issues of reproductive health and how they are relevant to dermatologic care,” she added.

Dr. Zaenglein’s take home message: “Dermatologists should educate all patients of childbearing potential taking isotretinoin on how to acquire and use emergency contraception at every visit.” As for additional research, she said that since the study was conducted with pediatric dermatologists, “it would be very interesting to see if general dermatologists had the same lack of comfort in educating patients on emergency contraception and what their standard counseling practices are.”

The study received no outside funding. Dr. Zaenglein is a member of the AAD’s iPLEDGE Work Group and serves as an editor-in-chief of Pediatric Dermatology.

, in a survey of 57 clinicians.

Pregnancies among patients on isotretinoin have declined since the iPLEDGE risk management program was introduced in 2005, but from 2011 to 2017, 210 to 310 pregnancies were reported to the Food and Drug Administration every year, wrote Catherine E. Smiley of Penn State University, Hershey, Pa., and coauthors Melissa Butt, DrPH, and Andrea L. Zaenglein, MD, of Penn State.

For patients on isotretinoin, EC “becomes critical when abstinence fails or contraception is not used properly,” but EC merits only a brief mention in iPLEDGE materials for patients and providers, they noted.

Patients on isotretinoin who choose abstinence as their form of birth control are the group at greatest risk for pregnancy, Dr. Zaenglein, professor of dermatology and pediatric dermatology, Penn State University, said in an interview. “However, the iPLEDGE program fails to educate patients adequately on emergency contraception,” she explained.

To assess pediatric dermatologists’ understanding of EC and their contraception counseling practices for isotretinoin patients, the researchers surveyed 57 pediatric dermatologists who prescribed isotretinoin as part of their practices. The findings were published in Pediatric Dermatology.Respondents included 53 practicing dermatologists, 2 residents, and 2 fellows. Approximately one-third (31.6%) had been in practice for 6-10 years, almost 23% had been in practice for 3-5 years, and almost 20% had been in practice for 21 or more years. Almost two-thirds practiced pediatric dermatology only.

Overall, 58% of the respondents strongly agreed that they provided contraception counseling to patients at their initial visit for isotretinoin, but only 7% and 3.5% reported providing EC counseling at initial and follow-up visits, respectively. More than half (58%) said they did not counsel patients on the side effects of EC.

As for provider education, 7.1% of respondents said they had received formal education on EC counseling, 25% reported receiving informal education on EC counseling, and 68% said they received no education on EC counseling.

A total of 32% of respondents said they were at least somewhat confident in how to obtain EC in their state.

EC is an effective form of contraception if used after unprotected intercourse, and discounts can reduce the price to as low as $9.69, the researchers wrote in their discussion. “Given that most providers in this study did not receive formal education on EC, and most do not provide EC counseling to their patients of reproductive potential on isotretinoin, EC education should be a core competency in dermatology residency education on isotretinoin prescribing,” the researchers noted. In addition, EC counseling in the iPLEDGE program should be improved by including more information in education materials and reminding patients that EC is an option, they said.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the small sample size and the multiple-choice format that prevented respondents to share rationales for their responses, the researchers noted.

However, the results highlight the need to improve EC education among pediatric dermatologists to better inform patients considering isotretinoin, especially those choosing abstinence as a method of birth control, they emphasized.

“This study is very important at this specific time for two reasons,” Dr. Zaenglein said in an interview. “The first is that with the recent disastrous rollout of the new iPLEDGE changes, there have been many calls to reform the REMS program. For the first time in the 22-year history of the program, the isotretinoin manufacturers, who manage the iPLEDGE program as an unidentified group (the IPMG), have been forced by the FDA to meet with the AAD iPLEDGE Task Force,” said Dr. Zaenglein, a member of the task force.

“The task force is currently advocating for common sense changes to iPLEDGE and I think enhancing education on emergency contraception is vital to the goal of the program, stated as ‘to manage the risk of isotretinoin’s teratogenicity and to minimize fetal exposure,’ ” she added. For many patients who previously became pregnant on isotretinoin, Plan B, an over-the-counter, FDA-approved form of contraception, might have prevented that pregnancy if the patients received adequate education on EC, she said.

The current study is especially relevant now, said Dr. Zaenglein. “With the reversal of Roe v. Wade, access to abortion is restricted or completely banned in many states, which makes educating our patients on how to prevent pregnancy even more important.”

Dr. Zaenglein said she was “somewhat surprised” by how many respondents were not educating their isotretinoin patients on EC. “However, these results follow a known trend among dermatologists. Only 50% of dermatologists prescribe oral contraceptives for acne, despite its being an FDA-approved treatment for the most common dermatologic condition we see in adolescents and young adults,” she noted.

“In general, dermatologists, and subsequently dermatology residents, are poorly educated on issues of reproductive health and how they are relevant to dermatologic care,” she added.

Dr. Zaenglein’s take home message: “Dermatologists should educate all patients of childbearing potential taking isotretinoin on how to acquire and use emergency contraception at every visit.” As for additional research, she said that since the study was conducted with pediatric dermatologists, “it would be very interesting to see if general dermatologists had the same lack of comfort in educating patients on emergency contraception and what their standard counseling practices are.”

The study received no outside funding. Dr. Zaenglein is a member of the AAD’s iPLEDGE Work Group and serves as an editor-in-chief of Pediatric Dermatology.

FROM PEDIATRIC DERMATOLOGY

Hormonal therapy a safe, long term option for older women with recalcitrant acne

PORTLAND, ORE. – During her dermatology residency training at the University of California, Irvine, Medical Center, Jenny Murase, MD, remembers hearing a colleague say that her most angry patients of the day were adult women with recalcitrant acne who present to the clinic with questions like, “My skin has been clear my whole life! What’s going on?”

Such . In fact, 82% fail multiple courses of systemic antibiotics and 32% relapse after using isotretinoin, Dr. Murase, director of medical dermatology consultative services and patch testing at the Palo Alto Foundation Medical Group, said at the annual meeting of the Pacific Dermatologic Association.

In her clinical experience, hormonal therapy is a safe long-term option for recalcitrant acne in postmenarcheal females over the age of 14. “Although oral antibiotics are going to be superior to hormonal therapy in the first month or two, when you get to about six months, they have equivalent efficacy,” she said.

Telltale signs of acne associated with androgen excess include the development of nodulocystic papules along the jawline and small comedones over the forehead. Female patients with acne may request that labs be ordered to check their hormone levels, but that often is not necessary, according to Dr. Murase, who is also associate clinical professor of dermatology at the University of California, San Francisco. “There aren’t strict guidelines to indicate when you should perform hormonal testing, but warning signs that warrant further evaluation include hirsutism, androgenetic alopecia, virilization, infertility, oligomenorrhea or amenorrhea, and sudden onset of severe acne. The most common situation that warrants hormonal testing is polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS).”

When there is a strong suspicion for hyperandrogenism, essential labs include free and total testosterone. Free testosterone is commonly elevated in patients with PCOS and total testosterone levels over 200 ng/dL is suggestive of an ovarian tumor. Other essential labs include 17-hyydroxyprogesterone (values greater than 200 ng/dL indicate congenital adrenal hyperplasia), and dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEA-S); levels over 8,000 mcg/dL indicate an adrenal tumor, while levels in the 4,000-8,000 mcg/dL range indicate congenital adrenal hyperplasia.

Helpful lab tests to consider include the ratio of luteinizing hormone to follicle-stimulating hormone; a 3:1 ratio or greater is suggestive for PCOS. “Ordering a prolactin level can also help, especially if patients are describing issues with headaches, which could indicate a pituitary tumor,” Dr. Murase added. Measuring sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG) levels can also be helpful. “If a patient has been on oral contraceptives for a long time, it increases their SHBG,” which, in older women, she said, “is inversely related to the development of type 2 diabetes.”

All labs for hyperandrogenism should be performed early in the morning on day 3 of the patient’s menstrual cycle. “If patients are on some kind of hormonal therapy, they need to be off of it for at least 6 weeks in order for you get a relevant test,” she said. Other relevant labs to consider include fasting glucose and lipids, cortisol, and thyroid-stimulating hormone.

Oral contraceptives

Estrogen contained in oral contraceptives (OCs) provides the most benefit to acne patients. “It reduces sebum production, decreases free testosterone and DHEA-S by stimulating SHBG synthesis in the liver, inhibits 5-alpha-reductase, which decreases peripheral testosterone conversion, and it decreases the production of ovarian and adrenal androgens,” Dr. Murase explained. “On average, you can get about 40%-70% reduction of lesion count, which is pretty good.”

Progestins with low androgenetic activity are the most helpful for acne, including norgestimate, desogestrel, and drospirenone. FDA-approved OC options include Ortho Tri-Cyclen, EstroStep, Yaz, and Beyaz. None has data showing superior efficacy.

No Pap smear or pelvic exam is required when prescribing OCs, but the risk of clotting should be discussed with patients. According to Dr. Murase, the risk of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) at baseline is about 1 per 10,000 woman-years, while the risk of DVT after 1 year on an OC is 3.4 per 10,000 years.

“This is a very mild increased risk that we’re talking about, but it is relevant in smokers, in those with hypertension, and in those who are diabetic,” she said. As for the risk of cancer associated with the use of OCs, a large collaborative study found a relative risk of 1.24 for developing breast cancer (not dose or duration related), but a risk reduction for endometrial, colorectal, and ovarian cancer.

The most common side effects associated with OCs are unscheduled bleeding, nausea, breast tenderness, and possible weight gain. Concomitant antibiotics can be used, with the exception of CYP3A4 inducers, such as rifampin. “That’s the main antibiotic we have to worry about that could affect the efficacy of the birth control pill,” she said. “It accounts for about three-quarters of pregnancies on antibiotics.”

Tetracyclines do not appear to increase the rate of birth defects with incidental first-trimester exposure, and data are reassuring but “tetracycline should be stopped within the first trimester as soon as the patient discovers she is pregnant,” Dr. Murase said.

Contraindications for OCs include being pregnant or breastfeeding; history of stroke, venous thromboembolism, or MI; history of smoking and being over age 35; uncontrolled hypertension; migraines with focal symptoms/aura; current or past breast cancer; hypercholesterolemia; diabetes with end-organ damage or having diabetes over age 35; liver issues such as a tumor, viral hepatitis, or cirrhosis; and a history of major surgery with prolonged immobilization.

Spironolactone

Another treatment option is spironolactone, a potassium-sparing diuretic that blocks aldosterone at a dose of 25 mg/day. At doses of 50-100 mg/day, it blocks androgen. “It can be used in combination with an oral contraceptive, with the rates of efficacy reported to range between 33% and 85%,” Dr. Murase said.

Spironolactone can also reduce hirsutism, improve androgenetic alopecia, and lower blood pressure by about 5 mm Hg systolic and 2.5 mm Hg diastolic. Dr. Murase usually checks blood pressure in patients, and “only if they’re really low I’ll talk about the potential for postural hypotension and the fact that you can get a little bit dizzy when going from a position of lying down to standing up.” Potassium levels should be checked at baseline and 4 weeks in patients older than age 46, in those with cardiac and/or renal disease, or in those on concomitant drospirenone or a third-generation progestin.

Spironolactone is classified as a pregnancy category D drug that could compromise the genital development of a male fetus. “So the onus is on us as providers to have the conversation with our patient,” she said. “If you’re putting a patient on spironolactone and they are of child-bearing age, you need to make sure that you’ve had the conversation with them about the fact that they should not get pregnant while on the medicine.”

Spironolactone also has a boxed warning citing the development of benign tumors in animal studies. That warning is based on studies in rats at doses of 10-150 mg/kg per day, “which is an extremely high dose and would never be given in humans,” said Dr. Murase, who has coauthored CME content regarding the safety of dermatologic medications in pregnancy and lactation.

In humans, there has been no evidence of the development of benign tumors associated with spironolactone therapy, and “there has been a decreased risk of prostate cancer and no association with its use and the development of breast, ovarian, bladder, kidney, gastric, or esophageal cancer,” she said.

Dr. Murase noted that during pregnancy, first-line oral antibiotics include amoxicillin for acne rosacea and cefadroxil for acne vulgaris. Macrolides are a second-line choice because of an increase in atrial/ventricular septal defects and pyloric stenosis that have been reported with first-trimester exposure.

“Erythromycin is the preferred choice over azithromycin and clarithromycin because it has the most data, [but] erythromycin estolate has been associated with increased AST levels in the second trimester,” she said. “It occurs in about 10% of cases and is reversible. Erythromycin base and erythromycin ethylsuccinate do not have this risk, and those are preferable.”

Dr. Murase disclosed that she has been a paid speaker of unbranded medical content for Regeneron and UCB. She is also a member of the advisory board for Leo Pharma, Eli Lilly, UCB, and Genzyme/Sanofi.

PORTLAND, ORE. – During her dermatology residency training at the University of California, Irvine, Medical Center, Jenny Murase, MD, remembers hearing a colleague say that her most angry patients of the day were adult women with recalcitrant acne who present to the clinic with questions like, “My skin has been clear my whole life! What’s going on?”

Such . In fact, 82% fail multiple courses of systemic antibiotics and 32% relapse after using isotretinoin, Dr. Murase, director of medical dermatology consultative services and patch testing at the Palo Alto Foundation Medical Group, said at the annual meeting of the Pacific Dermatologic Association.

In her clinical experience, hormonal therapy is a safe long-term option for recalcitrant acne in postmenarcheal females over the age of 14. “Although oral antibiotics are going to be superior to hormonal therapy in the first month or two, when you get to about six months, they have equivalent efficacy,” she said.

Telltale signs of acne associated with androgen excess include the development of nodulocystic papules along the jawline and small comedones over the forehead. Female patients with acne may request that labs be ordered to check their hormone levels, but that often is not necessary, according to Dr. Murase, who is also associate clinical professor of dermatology at the University of California, San Francisco. “There aren’t strict guidelines to indicate when you should perform hormonal testing, but warning signs that warrant further evaluation include hirsutism, androgenetic alopecia, virilization, infertility, oligomenorrhea or amenorrhea, and sudden onset of severe acne. The most common situation that warrants hormonal testing is polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS).”

When there is a strong suspicion for hyperandrogenism, essential labs include free and total testosterone. Free testosterone is commonly elevated in patients with PCOS and total testosterone levels over 200 ng/dL is suggestive of an ovarian tumor. Other essential labs include 17-hyydroxyprogesterone (values greater than 200 ng/dL indicate congenital adrenal hyperplasia), and dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEA-S); levels over 8,000 mcg/dL indicate an adrenal tumor, while levels in the 4,000-8,000 mcg/dL range indicate congenital adrenal hyperplasia.

Helpful lab tests to consider include the ratio of luteinizing hormone to follicle-stimulating hormone; a 3:1 ratio or greater is suggestive for PCOS. “Ordering a prolactin level can also help, especially if patients are describing issues with headaches, which could indicate a pituitary tumor,” Dr. Murase added. Measuring sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG) levels can also be helpful. “If a patient has been on oral contraceptives for a long time, it increases their SHBG,” which, in older women, she said, “is inversely related to the development of type 2 diabetes.”

All labs for hyperandrogenism should be performed early in the morning on day 3 of the patient’s menstrual cycle. “If patients are on some kind of hormonal therapy, they need to be off of it for at least 6 weeks in order for you get a relevant test,” she said. Other relevant labs to consider include fasting glucose and lipids, cortisol, and thyroid-stimulating hormone.

Oral contraceptives

Estrogen contained in oral contraceptives (OCs) provides the most benefit to acne patients. “It reduces sebum production, decreases free testosterone and DHEA-S by stimulating SHBG synthesis in the liver, inhibits 5-alpha-reductase, which decreases peripheral testosterone conversion, and it decreases the production of ovarian and adrenal androgens,” Dr. Murase explained. “On average, you can get about 40%-70% reduction of lesion count, which is pretty good.”

Progestins with low androgenetic activity are the most helpful for acne, including norgestimate, desogestrel, and drospirenone. FDA-approved OC options include Ortho Tri-Cyclen, EstroStep, Yaz, and Beyaz. None has data showing superior efficacy.

No Pap smear or pelvic exam is required when prescribing OCs, but the risk of clotting should be discussed with patients. According to Dr. Murase, the risk of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) at baseline is about 1 per 10,000 woman-years, while the risk of DVT after 1 year on an OC is 3.4 per 10,000 years.

“This is a very mild increased risk that we’re talking about, but it is relevant in smokers, in those with hypertension, and in those who are diabetic,” she said. As for the risk of cancer associated with the use of OCs, a large collaborative study found a relative risk of 1.24 for developing breast cancer (not dose or duration related), but a risk reduction for endometrial, colorectal, and ovarian cancer.

The most common side effects associated with OCs are unscheduled bleeding, nausea, breast tenderness, and possible weight gain. Concomitant antibiotics can be used, with the exception of CYP3A4 inducers, such as rifampin. “That’s the main antibiotic we have to worry about that could affect the efficacy of the birth control pill,” she said. “It accounts for about three-quarters of pregnancies on antibiotics.”

Tetracyclines do not appear to increase the rate of birth defects with incidental first-trimester exposure, and data are reassuring but “tetracycline should be stopped within the first trimester as soon as the patient discovers she is pregnant,” Dr. Murase said.

Contraindications for OCs include being pregnant or breastfeeding; history of stroke, venous thromboembolism, or MI; history of smoking and being over age 35; uncontrolled hypertension; migraines with focal symptoms/aura; current or past breast cancer; hypercholesterolemia; diabetes with end-organ damage or having diabetes over age 35; liver issues such as a tumor, viral hepatitis, or cirrhosis; and a history of major surgery with prolonged immobilization.

Spironolactone

Another treatment option is spironolactone, a potassium-sparing diuretic that blocks aldosterone at a dose of 25 mg/day. At doses of 50-100 mg/day, it blocks androgen. “It can be used in combination with an oral contraceptive, with the rates of efficacy reported to range between 33% and 85%,” Dr. Murase said.

Spironolactone can also reduce hirsutism, improve androgenetic alopecia, and lower blood pressure by about 5 mm Hg systolic and 2.5 mm Hg diastolic. Dr. Murase usually checks blood pressure in patients, and “only if they’re really low I’ll talk about the potential for postural hypotension and the fact that you can get a little bit dizzy when going from a position of lying down to standing up.” Potassium levels should be checked at baseline and 4 weeks in patients older than age 46, in those with cardiac and/or renal disease, or in those on concomitant drospirenone or a third-generation progestin.

Spironolactone is classified as a pregnancy category D drug that could compromise the genital development of a male fetus. “So the onus is on us as providers to have the conversation with our patient,” she said. “If you’re putting a patient on spironolactone and they are of child-bearing age, you need to make sure that you’ve had the conversation with them about the fact that they should not get pregnant while on the medicine.”

Spironolactone also has a boxed warning citing the development of benign tumors in animal studies. That warning is based on studies in rats at doses of 10-150 mg/kg per day, “which is an extremely high dose and would never be given in humans,” said Dr. Murase, who has coauthored CME content regarding the safety of dermatologic medications in pregnancy and lactation.

In humans, there has been no evidence of the development of benign tumors associated with spironolactone therapy, and “there has been a decreased risk of prostate cancer and no association with its use and the development of breast, ovarian, bladder, kidney, gastric, or esophageal cancer,” she said.

Dr. Murase noted that during pregnancy, first-line oral antibiotics include amoxicillin for acne rosacea and cefadroxil for acne vulgaris. Macrolides are a second-line choice because of an increase in atrial/ventricular septal defects and pyloric stenosis that have been reported with first-trimester exposure.

“Erythromycin is the preferred choice over azithromycin and clarithromycin because it has the most data, [but] erythromycin estolate has been associated with increased AST levels in the second trimester,” she said. “It occurs in about 10% of cases and is reversible. Erythromycin base and erythromycin ethylsuccinate do not have this risk, and those are preferable.”

Dr. Murase disclosed that she has been a paid speaker of unbranded medical content for Regeneron and UCB. She is also a member of the advisory board for Leo Pharma, Eli Lilly, UCB, and Genzyme/Sanofi.

PORTLAND, ORE. – During her dermatology residency training at the University of California, Irvine, Medical Center, Jenny Murase, MD, remembers hearing a colleague say that her most angry patients of the day were adult women with recalcitrant acne who present to the clinic with questions like, “My skin has been clear my whole life! What’s going on?”