User login

Biopsy can underestimate diversity, aggressiveness of basal cell carcinomas

SAN DIEGO – Histology of basal cell carcinomas removed by Mohs micrographic surgery showed that presurgical biopsies had not revealed all tumor subtypes in 64% of cases, and had underestimated the aggressiveness of the tumors 24% of the time, according to data from a large, multicenter, retrospective study.

“Unfortunately, while cheap and cost-effective, biopsies are a subsample of the full malignancy,” said Dr. Murad Alam, professor of dermatology, otolaryngology, and surgery at Northwestern University in Chicago. “Skin biopsy of basal cell carcinoma [BCC] may fail to detect all BCC subtypes, and as such may underestimate the aggressiveness of an individual BCC tumor.”

Basal cell carcinoma is the most common skin cancer worldwide, and can broadly be grouped into aggressive and indolent types, Dr. Alam said at the annual meeting of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery. But tumors often show mixed histology, and cancer treatment needs to target the most aggressive subtype present in the tumor, he added. Results of past studies suggested that biopsies of BCCs could miss tumor subtypes, but the current research is the first large, multicenter study to confirm these findings, he and his associates said.

For the study, the investigators compared biopsy reports and microscopic slides of Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) specimens from 871 consecutive cases of BCC treated at three hospitals in Illinois from 2013 to 2014. Patients first underwent biopsies, followed by complete excision of their tumors during MMS. Almost 59% of patients were male, and tumors were most commonly removed from the nose or cheek. In all, 78% of biopsies were obtained by the shave technique, but punch and excisional biopsies also were performed, the researchers noted.

Using standard definitions of BCC subtypes, the investigators compared levels of concordance between biopsy and MMS histology findings, Dr. Alam said. They also grouped tumor specimens as high risk (that is, infiltrative, morpheic, micronodular, basosquamous) or low risk (superficial or nodular), and determined whether tumor biopsy and MMS histology yielded the same or discordant risk assessments, he added.

Biopsies identified only 18% of tumors as being of mixed histology, compared with 57% of MMS specimens, said Dr. Alam. Biopsy results matched MMS histologies in only 31% of cases, while in 64% of cases, the MMS specimen yielded more tumor subtypes than the biopsy specimen. The researchers noted that biopsy yielded more subtypes than did MMS in 4% of cases, and that MMS and biopsy subtypes were fully discordant in only four cases.

Dr. Alam and his associates declared no external funding sources or conflicts of interest.

SAN DIEGO – Histology of basal cell carcinomas removed by Mohs micrographic surgery showed that presurgical biopsies had not revealed all tumor subtypes in 64% of cases, and had underestimated the aggressiveness of the tumors 24% of the time, according to data from a large, multicenter, retrospective study.

“Unfortunately, while cheap and cost-effective, biopsies are a subsample of the full malignancy,” said Dr. Murad Alam, professor of dermatology, otolaryngology, and surgery at Northwestern University in Chicago. “Skin biopsy of basal cell carcinoma [BCC] may fail to detect all BCC subtypes, and as such may underestimate the aggressiveness of an individual BCC tumor.”

Basal cell carcinoma is the most common skin cancer worldwide, and can broadly be grouped into aggressive and indolent types, Dr. Alam said at the annual meeting of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery. But tumors often show mixed histology, and cancer treatment needs to target the most aggressive subtype present in the tumor, he added. Results of past studies suggested that biopsies of BCCs could miss tumor subtypes, but the current research is the first large, multicenter study to confirm these findings, he and his associates said.

For the study, the investigators compared biopsy reports and microscopic slides of Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) specimens from 871 consecutive cases of BCC treated at three hospitals in Illinois from 2013 to 2014. Patients first underwent biopsies, followed by complete excision of their tumors during MMS. Almost 59% of patients were male, and tumors were most commonly removed from the nose or cheek. In all, 78% of biopsies were obtained by the shave technique, but punch and excisional biopsies also were performed, the researchers noted.

Using standard definitions of BCC subtypes, the investigators compared levels of concordance between biopsy and MMS histology findings, Dr. Alam said. They also grouped tumor specimens as high risk (that is, infiltrative, morpheic, micronodular, basosquamous) or low risk (superficial or nodular), and determined whether tumor biopsy and MMS histology yielded the same or discordant risk assessments, he added.

Biopsies identified only 18% of tumors as being of mixed histology, compared with 57% of MMS specimens, said Dr. Alam. Biopsy results matched MMS histologies in only 31% of cases, while in 64% of cases, the MMS specimen yielded more tumor subtypes than the biopsy specimen. The researchers noted that biopsy yielded more subtypes than did MMS in 4% of cases, and that MMS and biopsy subtypes were fully discordant in only four cases.

Dr. Alam and his associates declared no external funding sources or conflicts of interest.

SAN DIEGO – Histology of basal cell carcinomas removed by Mohs micrographic surgery showed that presurgical biopsies had not revealed all tumor subtypes in 64% of cases, and had underestimated the aggressiveness of the tumors 24% of the time, according to data from a large, multicenter, retrospective study.

“Unfortunately, while cheap and cost-effective, biopsies are a subsample of the full malignancy,” said Dr. Murad Alam, professor of dermatology, otolaryngology, and surgery at Northwestern University in Chicago. “Skin biopsy of basal cell carcinoma [BCC] may fail to detect all BCC subtypes, and as such may underestimate the aggressiveness of an individual BCC tumor.”

Basal cell carcinoma is the most common skin cancer worldwide, and can broadly be grouped into aggressive and indolent types, Dr. Alam said at the annual meeting of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery. But tumors often show mixed histology, and cancer treatment needs to target the most aggressive subtype present in the tumor, he added. Results of past studies suggested that biopsies of BCCs could miss tumor subtypes, but the current research is the first large, multicenter study to confirm these findings, he and his associates said.

For the study, the investigators compared biopsy reports and microscopic slides of Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) specimens from 871 consecutive cases of BCC treated at three hospitals in Illinois from 2013 to 2014. Patients first underwent biopsies, followed by complete excision of their tumors during MMS. Almost 59% of patients were male, and tumors were most commonly removed from the nose or cheek. In all, 78% of biopsies were obtained by the shave technique, but punch and excisional biopsies also were performed, the researchers noted.

Using standard definitions of BCC subtypes, the investigators compared levels of concordance between biopsy and MMS histology findings, Dr. Alam said. They also grouped tumor specimens as high risk (that is, infiltrative, morpheic, micronodular, basosquamous) or low risk (superficial or nodular), and determined whether tumor biopsy and MMS histology yielded the same or discordant risk assessments, he added.

Biopsies identified only 18% of tumors as being of mixed histology, compared with 57% of MMS specimens, said Dr. Alam. Biopsy results matched MMS histologies in only 31% of cases, while in 64% of cases, the MMS specimen yielded more tumor subtypes than the biopsy specimen. The researchers noted that biopsy yielded more subtypes than did MMS in 4% of cases, and that MMS and biopsy subtypes were fully discordant in only four cases.

Dr. Alam and his associates declared no external funding sources or conflicts of interest.

Key clinical point: Definitive excision by Mohs micrographic surgery reveals more information about basal cell carcinoma subtypes and tumor behavior than does biopsy.

Major finding: Compared with Mohs specimens, biopsy underestimated the diversity of tumor subtypes in 64% of cases, and underestimated tumor aggressiveness in 24% of cases.

Data source: Multicenter retrospective study of 871 basal cell carcinomas that were biopsied and then removed by Mohs micrographic surgery.

Disclosures: The investigators declared no external funding sources or conflicts of interest.

Mixed results seen for imaging skin tumors before Mohs surgery

SAN DIEGO – Dermoscopy was no better than visual clinical inspection for delineating skin tumor margins before Mohs micrographic surgery, based on data from a pooled analysis, according to Dr. Syril Que.

But her review showed that confocal microscopy and optical coherence tomography devices “may be of potential diagnostic value – both for defining BCC [basal cell carcinoma] tumor margins prior to excision and for minimizing the number of stages needed subsequently,” said Dr. Que, a dermatology resident at the University of Connecticut Health Center in Farmington. “Nevertheless, there are limitations to both imaging modalities, and adjustments that need to be made before they are incorporated as a standard of practice in Mohs surgery,” she emphasized.

In a search of PubMed, Dr. Que found 27 original research studies that compared noninvasive imaging devices for delineating skin tumor margins with Mohs histology results. The studies were published between 2004 and 2014; 26 studies included BCC specimens, 3 included squamous cell carcinomas, and only 1 looked at lentigo maligna and melanoma. When broken down by type of imaging device, 17 of the studies focused on confocal microscopy, 5 were of dermoscopy, and 5 were of optical coherence tomography, she added. The number of specimens per study ranged from 2 to 115.

Only one study found an added diagnostic benefit from dermoscopy of skin tumor margins, compared with visual inspection, and that was a report of only two cases, said Dr. Que. The larger studies of 40-60 patients showed no significant difference between clinical inspection and dermoscopy for delineating margins. “Currently available evidence shows that dermoscopy has no advantage over clinical inspection when used prior to Mohs surgery,” she concluded.

Studies of confocal microscopy of BCCs were more promising, Dr. Que noted. These papers reported sensitivities of 73%-100%, and specificities of 89%-99%. “Sensitivity and specificity tended to be lower for micronodular or infiltrative BCCs,” she added. The papers did not report sensitivity or specificity values for squamous cell carcinomas, but did state that it was difficult to use confocal microscopy alone to distinguish between these tumors and actinic keratoses, she said at the annual meeting of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery. Few studies addressed the use of confocal microscopy for melanoma or lentigo maligna, she added.

Finally, the papers on optical coherence tomography reported that the device “showed excellent correlation with histopathology, and was 84% accurate in predicting surgical margins,” said Dr. Que. “Optical coherence tomography appropriately assessed the subclinical spread of tumor, based on the close proximity of optical coherence tomography margins to the final Mohs defect,” she added.

Dr. Que said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Dermoscopy was no better than visual clinical inspection for delineating skin tumor margins before Mohs micrographic surgery, based on data from a pooled analysis, according to Dr. Syril Que.

But her review showed that confocal microscopy and optical coherence tomography devices “may be of potential diagnostic value – both for defining BCC [basal cell carcinoma] tumor margins prior to excision and for minimizing the number of stages needed subsequently,” said Dr. Que, a dermatology resident at the University of Connecticut Health Center in Farmington. “Nevertheless, there are limitations to both imaging modalities, and adjustments that need to be made before they are incorporated as a standard of practice in Mohs surgery,” she emphasized.

In a search of PubMed, Dr. Que found 27 original research studies that compared noninvasive imaging devices for delineating skin tumor margins with Mohs histology results. The studies were published between 2004 and 2014; 26 studies included BCC specimens, 3 included squamous cell carcinomas, and only 1 looked at lentigo maligna and melanoma. When broken down by type of imaging device, 17 of the studies focused on confocal microscopy, 5 were of dermoscopy, and 5 were of optical coherence tomography, she added. The number of specimens per study ranged from 2 to 115.

Only one study found an added diagnostic benefit from dermoscopy of skin tumor margins, compared with visual inspection, and that was a report of only two cases, said Dr. Que. The larger studies of 40-60 patients showed no significant difference between clinical inspection and dermoscopy for delineating margins. “Currently available evidence shows that dermoscopy has no advantage over clinical inspection when used prior to Mohs surgery,” she concluded.

Studies of confocal microscopy of BCCs were more promising, Dr. Que noted. These papers reported sensitivities of 73%-100%, and specificities of 89%-99%. “Sensitivity and specificity tended to be lower for micronodular or infiltrative BCCs,” she added. The papers did not report sensitivity or specificity values for squamous cell carcinomas, but did state that it was difficult to use confocal microscopy alone to distinguish between these tumors and actinic keratoses, she said at the annual meeting of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery. Few studies addressed the use of confocal microscopy for melanoma or lentigo maligna, she added.

Finally, the papers on optical coherence tomography reported that the device “showed excellent correlation with histopathology, and was 84% accurate in predicting surgical margins,” said Dr. Que. “Optical coherence tomography appropriately assessed the subclinical spread of tumor, based on the close proximity of optical coherence tomography margins to the final Mohs defect,” she added.

Dr. Que said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Dermoscopy was no better than visual clinical inspection for delineating skin tumor margins before Mohs micrographic surgery, based on data from a pooled analysis, according to Dr. Syril Que.

But her review showed that confocal microscopy and optical coherence tomography devices “may be of potential diagnostic value – both for defining BCC [basal cell carcinoma] tumor margins prior to excision and for minimizing the number of stages needed subsequently,” said Dr. Que, a dermatology resident at the University of Connecticut Health Center in Farmington. “Nevertheless, there are limitations to both imaging modalities, and adjustments that need to be made before they are incorporated as a standard of practice in Mohs surgery,” she emphasized.

In a search of PubMed, Dr. Que found 27 original research studies that compared noninvasive imaging devices for delineating skin tumor margins with Mohs histology results. The studies were published between 2004 and 2014; 26 studies included BCC specimens, 3 included squamous cell carcinomas, and only 1 looked at lentigo maligna and melanoma. When broken down by type of imaging device, 17 of the studies focused on confocal microscopy, 5 were of dermoscopy, and 5 were of optical coherence tomography, she added. The number of specimens per study ranged from 2 to 115.

Only one study found an added diagnostic benefit from dermoscopy of skin tumor margins, compared with visual inspection, and that was a report of only two cases, said Dr. Que. The larger studies of 40-60 patients showed no significant difference between clinical inspection and dermoscopy for delineating margins. “Currently available evidence shows that dermoscopy has no advantage over clinical inspection when used prior to Mohs surgery,” she concluded.

Studies of confocal microscopy of BCCs were more promising, Dr. Que noted. These papers reported sensitivities of 73%-100%, and specificities of 89%-99%. “Sensitivity and specificity tended to be lower for micronodular or infiltrative BCCs,” she added. The papers did not report sensitivity or specificity values for squamous cell carcinomas, but did state that it was difficult to use confocal microscopy alone to distinguish between these tumors and actinic keratoses, she said at the annual meeting of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery. Few studies addressed the use of confocal microscopy for melanoma or lentigo maligna, she added.

Finally, the papers on optical coherence tomography reported that the device “showed excellent correlation with histopathology, and was 84% accurate in predicting surgical margins,” said Dr. Que. “Optical coherence tomography appropriately assessed the subclinical spread of tumor, based on the close proximity of optical coherence tomography margins to the final Mohs defect,” she added.

Dr. Que said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

Vismodegib offers promise for basal cell carcinoma, with caveats

SAN DIEGO – Patients treated with vismodegib for locally advanced or metastatic basal cell carcinoma went a median of 15 months before their disease progressed or they stopped treatment because of side effects, according to a 30-month update of the pivotal ERIVANCE basal cell carcinoma study.

Median progression-free survival on the first-in-class oral hedgehog-pathway inhibitor was 9 months, reported Dr. Seaver Soon at the annual meeting of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery.

Data from two other trials of vismodegib resemble results from ERIVANCE, added Dr. Soon, a dermatologist in private practice in La Jolla, Calif. An expanded access study (J. Am. Acad. Dermatol 2014;70:60-9) of 119 patients with advanced basal cell carcinoma (BCC) reported comparable objective response rates (46.4% for patients with locally advanced BCC and 30.8% for patients with metastatic disease), and an interim analysis of data from the STEVIE trial had findings that were “very similar” to ERIVANCE, he said.

Thus far, vismodegib “offers a hope in treating otherwise difficult to manage, unresectable basal cell carcinoma tumors,” said Dr. Iren Kossintseva, a dermatologist in Vancouver, B.C. But the drug “may not be as tissue sparing as promised, she added. In a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia who had a large BCC on his lower eyelid and cheek, 7.5 months of vismodegib reduced the exophyticity and erosiveness of the tumor, but “likely did not substantially reduce the overall extent of necessary reconstruction,” she reported.

Vismodegib can cause potentially severe side effects. All seven patients who Dr. Kossintseva treated with 150 mg vismodegib per day during 2013-2014 developed “notable” adverse effects – including polycyclic rash, sensory and motor problems within the tumor area, bilateral edema of the lower limbs, congestive heart failure, and renal failure that has been slow to improve after stopping vismodegib, she said. “These are unique patients, and it’s often an uphill battle with these patients,” she added.

Tumors also can exhibit primary and secondary resistance to vismodegib, Dr. Soon noted. Studies have shown primary resistance characterized by tumor progression after as little as 2 months of treatment (Mol. Oncol. 2014; S1574-7891:00216-6) while secondary (or acquired) resistance occurs after an initial response to treatment and is linked to a mutation that interferes with drug binding, he said. Acquired resistance typically occurs when patients have been on vismodegib for about a year, Dr. Soon added. “Concurrent treatment with an alternative smoothened inhibitor, such as itraconazole, and downstream target inhibitors may overcome resistance,” he said. Dr. Kossintseva declared no conflicts of interest. Dr. Soon reported receiving honoraria and research grants from Genentech, the maker of vismodegib.

SAN DIEGO – Patients treated with vismodegib for locally advanced or metastatic basal cell carcinoma went a median of 15 months before their disease progressed or they stopped treatment because of side effects, according to a 30-month update of the pivotal ERIVANCE basal cell carcinoma study.

Median progression-free survival on the first-in-class oral hedgehog-pathway inhibitor was 9 months, reported Dr. Seaver Soon at the annual meeting of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery.

Data from two other trials of vismodegib resemble results from ERIVANCE, added Dr. Soon, a dermatologist in private practice in La Jolla, Calif. An expanded access study (J. Am. Acad. Dermatol 2014;70:60-9) of 119 patients with advanced basal cell carcinoma (BCC) reported comparable objective response rates (46.4% for patients with locally advanced BCC and 30.8% for patients with metastatic disease), and an interim analysis of data from the STEVIE trial had findings that were “very similar” to ERIVANCE, he said.

Thus far, vismodegib “offers a hope in treating otherwise difficult to manage, unresectable basal cell carcinoma tumors,” said Dr. Iren Kossintseva, a dermatologist in Vancouver, B.C. But the drug “may not be as tissue sparing as promised, she added. In a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia who had a large BCC on his lower eyelid and cheek, 7.5 months of vismodegib reduced the exophyticity and erosiveness of the tumor, but “likely did not substantially reduce the overall extent of necessary reconstruction,” she reported.

Vismodegib can cause potentially severe side effects. All seven patients who Dr. Kossintseva treated with 150 mg vismodegib per day during 2013-2014 developed “notable” adverse effects – including polycyclic rash, sensory and motor problems within the tumor area, bilateral edema of the lower limbs, congestive heart failure, and renal failure that has been slow to improve after stopping vismodegib, she said. “These are unique patients, and it’s often an uphill battle with these patients,” she added.

Tumors also can exhibit primary and secondary resistance to vismodegib, Dr. Soon noted. Studies have shown primary resistance characterized by tumor progression after as little as 2 months of treatment (Mol. Oncol. 2014; S1574-7891:00216-6) while secondary (or acquired) resistance occurs after an initial response to treatment and is linked to a mutation that interferes with drug binding, he said. Acquired resistance typically occurs when patients have been on vismodegib for about a year, Dr. Soon added. “Concurrent treatment with an alternative smoothened inhibitor, such as itraconazole, and downstream target inhibitors may overcome resistance,” he said. Dr. Kossintseva declared no conflicts of interest. Dr. Soon reported receiving honoraria and research grants from Genentech, the maker of vismodegib.

SAN DIEGO – Patients treated with vismodegib for locally advanced or metastatic basal cell carcinoma went a median of 15 months before their disease progressed or they stopped treatment because of side effects, according to a 30-month update of the pivotal ERIVANCE basal cell carcinoma study.

Median progression-free survival on the first-in-class oral hedgehog-pathway inhibitor was 9 months, reported Dr. Seaver Soon at the annual meeting of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery.

Data from two other trials of vismodegib resemble results from ERIVANCE, added Dr. Soon, a dermatologist in private practice in La Jolla, Calif. An expanded access study (J. Am. Acad. Dermatol 2014;70:60-9) of 119 patients with advanced basal cell carcinoma (BCC) reported comparable objective response rates (46.4% for patients with locally advanced BCC and 30.8% for patients with metastatic disease), and an interim analysis of data from the STEVIE trial had findings that were “very similar” to ERIVANCE, he said.

Thus far, vismodegib “offers a hope in treating otherwise difficult to manage, unresectable basal cell carcinoma tumors,” said Dr. Iren Kossintseva, a dermatologist in Vancouver, B.C. But the drug “may not be as tissue sparing as promised, she added. In a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia who had a large BCC on his lower eyelid and cheek, 7.5 months of vismodegib reduced the exophyticity and erosiveness of the tumor, but “likely did not substantially reduce the overall extent of necessary reconstruction,” she reported.

Vismodegib can cause potentially severe side effects. All seven patients who Dr. Kossintseva treated with 150 mg vismodegib per day during 2013-2014 developed “notable” adverse effects – including polycyclic rash, sensory and motor problems within the tumor area, bilateral edema of the lower limbs, congestive heart failure, and renal failure that has been slow to improve after stopping vismodegib, she said. “These are unique patients, and it’s often an uphill battle with these patients,” she added.

Tumors also can exhibit primary and secondary resistance to vismodegib, Dr. Soon noted. Studies have shown primary resistance characterized by tumor progression after as little as 2 months of treatment (Mol. Oncol. 2014; S1574-7891:00216-6) while secondary (or acquired) resistance occurs after an initial response to treatment and is linked to a mutation that interferes with drug binding, he said. Acquired resistance typically occurs when patients have been on vismodegib for about a year, Dr. Soon added. “Concurrent treatment with an alternative smoothened inhibitor, such as itraconazole, and downstream target inhibitors may overcome resistance,” he said. Dr. Kossintseva declared no conflicts of interest. Dr. Soon reported receiving honoraria and research grants from Genentech, the maker of vismodegib.

Low-risk actinic keratosis? No such thing

AMSTERDAM – The majority of cutaneous infiltrating squamous cell carcinomas arise via direct transformation of grade 1 actinic keratoses – that is, differentiated dysplasia of the basal one-third of the epidermis – via extension of atypical keratinocytes and ultimately of tumor cells along the adnexal epithelium rather than through the classical pathway most dermatologists know, Dr. Maria Teresa Fernandez-Figueras said at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

This direct transformation by means of what pathologists call the differentiated pathway has important implications for clinical practice, she added.

“For me, this is something that should change our way of seeing these lesions. When you’re facing an actinic keratosis-1 (AK 1), I think you can no longer call it a low-grade lesion, an early lesion, or a low-risk lesion, because you don’t know if it’s going to follow the differentiated pathway. It can infiltrate at any moment. So from this point of view, all AKs carry a risk of immediate transformation – a low risk, it’s true – and thus maybe all of them require treatment,” explained Dr. Fernandez-Figueras, a pathologist at the University of Barcelona.

The classical pathway by which an AK 1 transforms into an infiltrating squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is as follows: Before an AK 1 can become a malignant lesion, it first must transition to an AK 2, marked by progression of dysplasia to the lower two-thirds of the epidermis, and then to AK 3, with full-thickness epidermal dysplasia. That’s how most dermatologists understand the process. But there are precedents elsewhere in the body for the existence of a separate differentiated pathway.

The most notable example is vulvar carcinoma. Human papillomavirus–related vulvar malignancy is known to arise from two different pathways. In the classical pathway, vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia 1 (VIN 1) must transition to VIN 2 and then VIN 3 before transformation to SCC. But the cancer can also emerge directly from areas of differentiated dysplastic VIN 1 epidermis, bypassing VINs 2 and 3 altogether.

Dr. Fernandez-Figueras sought to study the relative importance of the two pathways in the formation of cutaneous SCC. To do so, she and two other pathologists examined pathologic specimens and reports for 503 consecutive cases of cutaneous infiltrating SCC. The majority were unsuitable for thorough evaluation because they were fragmented or curettaged, leaving a final study sample of 196 cases.

Two-thirds of all the SCCs had only AK 1 overlying the cutaneous malignancy. Another 15% had overlying AK 2, and 18% had overlying AK 3. A total of 79% of the SCCs had only AK 1 in the epidermis adjacent to the SCC, while 7% had AK 2, and 8% had AK 3; the remaining 6% were unevaluable on this score.

Proliferative growth extending along the sweat ducts and hair follicles of the adnexal epithelium over the SCC was identified in 32% of the cancerous lesions with overlying AK 1, compared with 23% of cancers with overlying AK 2 and 14% with overlying AK 3. Thirty-eight percent of SCCs with AK 1 in the adjacent epithelium had differentiated dysplastic growth migrating along the adnexal epithelium, as did 25% of SCCs with adjacent AK 2 and 11% with neighboring AK 2.

These observations suggest that the differentiated pathway is by far the more common of the two mechanisms of malignant transformation, according to Dr. Fernandez-Figueras.

“Another interesting observation was that very often the areas of invasion were coincident with the focus of adnexal extension,” she continued. “We believe that this tumor advance along the adnexal structures plays a pivotal role in transformation and inversion, especially in AK 1.”

One dermatologist in the audience challenged her. “What do you want us to do – aggressively excise all AKs?”

“I’m a pathologist; I don’t have a suggestion regarding treatment,” Dr. Fernandez-Figueras replied. “I’m just saying, don’t think that AK 1 is better than AK 3, and don’t think that making this distinction gives you any security that you can tell the patient, ‘Don’t worry, nothing is going to happen, we’ll wait until it’s AK 3.’ In my own case, I know that if I had an AK 1, I would treat it. I don’t want to wait to see if it’s going to follow the classical or the differentiated pathway. All lesions can be high grade.”

Session cochair Dr. Michael Reusch pronounced her findings and interpretation of them “completely consistent” with his own experience.

“I think from a histologic point of view, I completely share your view. Still, for the dermatologist part of us, it creates a problem as to what to do. It’s a major issue. The number of AKs out there is incredible,” commented Dr. Reusch of the University Clinics of Hamburg-Eppendorf, Germany.

Dr. Fernandez-Figueras reported that her study received financial support from Almirall.

AMSTERDAM – The majority of cutaneous infiltrating squamous cell carcinomas arise via direct transformation of grade 1 actinic keratoses – that is, differentiated dysplasia of the basal one-third of the epidermis – via extension of atypical keratinocytes and ultimately of tumor cells along the adnexal epithelium rather than through the classical pathway most dermatologists know, Dr. Maria Teresa Fernandez-Figueras said at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

This direct transformation by means of what pathologists call the differentiated pathway has important implications for clinical practice, she added.

“For me, this is something that should change our way of seeing these lesions. When you’re facing an actinic keratosis-1 (AK 1), I think you can no longer call it a low-grade lesion, an early lesion, or a low-risk lesion, because you don’t know if it’s going to follow the differentiated pathway. It can infiltrate at any moment. So from this point of view, all AKs carry a risk of immediate transformation – a low risk, it’s true – and thus maybe all of them require treatment,” explained Dr. Fernandez-Figueras, a pathologist at the University of Barcelona.

The classical pathway by which an AK 1 transforms into an infiltrating squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is as follows: Before an AK 1 can become a malignant lesion, it first must transition to an AK 2, marked by progression of dysplasia to the lower two-thirds of the epidermis, and then to AK 3, with full-thickness epidermal dysplasia. That’s how most dermatologists understand the process. But there are precedents elsewhere in the body for the existence of a separate differentiated pathway.

The most notable example is vulvar carcinoma. Human papillomavirus–related vulvar malignancy is known to arise from two different pathways. In the classical pathway, vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia 1 (VIN 1) must transition to VIN 2 and then VIN 3 before transformation to SCC. But the cancer can also emerge directly from areas of differentiated dysplastic VIN 1 epidermis, bypassing VINs 2 and 3 altogether.

Dr. Fernandez-Figueras sought to study the relative importance of the two pathways in the formation of cutaneous SCC. To do so, she and two other pathologists examined pathologic specimens and reports for 503 consecutive cases of cutaneous infiltrating SCC. The majority were unsuitable for thorough evaluation because they were fragmented or curettaged, leaving a final study sample of 196 cases.

Two-thirds of all the SCCs had only AK 1 overlying the cutaneous malignancy. Another 15% had overlying AK 2, and 18% had overlying AK 3. A total of 79% of the SCCs had only AK 1 in the epidermis adjacent to the SCC, while 7% had AK 2, and 8% had AK 3; the remaining 6% were unevaluable on this score.

Proliferative growth extending along the sweat ducts and hair follicles of the adnexal epithelium over the SCC was identified in 32% of the cancerous lesions with overlying AK 1, compared with 23% of cancers with overlying AK 2 and 14% with overlying AK 3. Thirty-eight percent of SCCs with AK 1 in the adjacent epithelium had differentiated dysplastic growth migrating along the adnexal epithelium, as did 25% of SCCs with adjacent AK 2 and 11% with neighboring AK 2.

These observations suggest that the differentiated pathway is by far the more common of the two mechanisms of malignant transformation, according to Dr. Fernandez-Figueras.

“Another interesting observation was that very often the areas of invasion were coincident with the focus of adnexal extension,” she continued. “We believe that this tumor advance along the adnexal structures plays a pivotal role in transformation and inversion, especially in AK 1.”

One dermatologist in the audience challenged her. “What do you want us to do – aggressively excise all AKs?”

“I’m a pathologist; I don’t have a suggestion regarding treatment,” Dr. Fernandez-Figueras replied. “I’m just saying, don’t think that AK 1 is better than AK 3, and don’t think that making this distinction gives you any security that you can tell the patient, ‘Don’t worry, nothing is going to happen, we’ll wait until it’s AK 3.’ In my own case, I know that if I had an AK 1, I would treat it. I don’t want to wait to see if it’s going to follow the classical or the differentiated pathway. All lesions can be high grade.”

Session cochair Dr. Michael Reusch pronounced her findings and interpretation of them “completely consistent” with his own experience.

“I think from a histologic point of view, I completely share your view. Still, for the dermatologist part of us, it creates a problem as to what to do. It’s a major issue. The number of AKs out there is incredible,” commented Dr. Reusch of the University Clinics of Hamburg-Eppendorf, Germany.

Dr. Fernandez-Figueras reported that her study received financial support from Almirall.

AMSTERDAM – The majority of cutaneous infiltrating squamous cell carcinomas arise via direct transformation of grade 1 actinic keratoses – that is, differentiated dysplasia of the basal one-third of the epidermis – via extension of atypical keratinocytes and ultimately of tumor cells along the adnexal epithelium rather than through the classical pathway most dermatologists know, Dr. Maria Teresa Fernandez-Figueras said at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

This direct transformation by means of what pathologists call the differentiated pathway has important implications for clinical practice, she added.

“For me, this is something that should change our way of seeing these lesions. When you’re facing an actinic keratosis-1 (AK 1), I think you can no longer call it a low-grade lesion, an early lesion, or a low-risk lesion, because you don’t know if it’s going to follow the differentiated pathway. It can infiltrate at any moment. So from this point of view, all AKs carry a risk of immediate transformation – a low risk, it’s true – and thus maybe all of them require treatment,” explained Dr. Fernandez-Figueras, a pathologist at the University of Barcelona.

The classical pathway by which an AK 1 transforms into an infiltrating squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is as follows: Before an AK 1 can become a malignant lesion, it first must transition to an AK 2, marked by progression of dysplasia to the lower two-thirds of the epidermis, and then to AK 3, with full-thickness epidermal dysplasia. That’s how most dermatologists understand the process. But there are precedents elsewhere in the body for the existence of a separate differentiated pathway.

The most notable example is vulvar carcinoma. Human papillomavirus–related vulvar malignancy is known to arise from two different pathways. In the classical pathway, vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia 1 (VIN 1) must transition to VIN 2 and then VIN 3 before transformation to SCC. But the cancer can also emerge directly from areas of differentiated dysplastic VIN 1 epidermis, bypassing VINs 2 and 3 altogether.

Dr. Fernandez-Figueras sought to study the relative importance of the two pathways in the formation of cutaneous SCC. To do so, she and two other pathologists examined pathologic specimens and reports for 503 consecutive cases of cutaneous infiltrating SCC. The majority were unsuitable for thorough evaluation because they were fragmented or curettaged, leaving a final study sample of 196 cases.

Two-thirds of all the SCCs had only AK 1 overlying the cutaneous malignancy. Another 15% had overlying AK 2, and 18% had overlying AK 3. A total of 79% of the SCCs had only AK 1 in the epidermis adjacent to the SCC, while 7% had AK 2, and 8% had AK 3; the remaining 6% were unevaluable on this score.

Proliferative growth extending along the sweat ducts and hair follicles of the adnexal epithelium over the SCC was identified in 32% of the cancerous lesions with overlying AK 1, compared with 23% of cancers with overlying AK 2 and 14% with overlying AK 3. Thirty-eight percent of SCCs with AK 1 in the adjacent epithelium had differentiated dysplastic growth migrating along the adnexal epithelium, as did 25% of SCCs with adjacent AK 2 and 11% with neighboring AK 2.

These observations suggest that the differentiated pathway is by far the more common of the two mechanisms of malignant transformation, according to Dr. Fernandez-Figueras.

“Another interesting observation was that very often the areas of invasion were coincident with the focus of adnexal extension,” she continued. “We believe that this tumor advance along the adnexal structures plays a pivotal role in transformation and inversion, especially in AK 1.”

One dermatologist in the audience challenged her. “What do you want us to do – aggressively excise all AKs?”

“I’m a pathologist; I don’t have a suggestion regarding treatment,” Dr. Fernandez-Figueras replied. “I’m just saying, don’t think that AK 1 is better than AK 3, and don’t think that making this distinction gives you any security that you can tell the patient, ‘Don’t worry, nothing is going to happen, we’ll wait until it’s AK 3.’ In my own case, I know that if I had an AK 1, I would treat it. I don’t want to wait to see if it’s going to follow the classical or the differentiated pathway. All lesions can be high grade.”

Session cochair Dr. Michael Reusch pronounced her findings and interpretation of them “completely consistent” with his own experience.

“I think from a histologic point of view, I completely share your view. Still, for the dermatologist part of us, it creates a problem as to what to do. It’s a major issue. The number of AKs out there is incredible,” commented Dr. Reusch of the University Clinics of Hamburg-Eppendorf, Germany.

Dr. Fernandez-Figueras reported that her study received financial support from Almirall.

AT THE EADV CONGRESS

Key clinical point: Actinic keratoses traditionally considered low-risk AK 1s with dysplasia confined to the basal one-third of the epidermis can undergo immediate transformation to infiltrating squamous cell carcinoma without mandatory sequential passage through AK 2 and 3.

Major finding: Two-thirds of SCCs had only AK 1 overlying the malignancy, 15% had overlying AK 2, and only 8% had AK 3.

Data source: A retrospective study, in which three pathologists examined the pathologic specimens and supporting reports for 196 cutaneous infiltrating SCCs.

Disclosures: The study received funding support from Almirall.

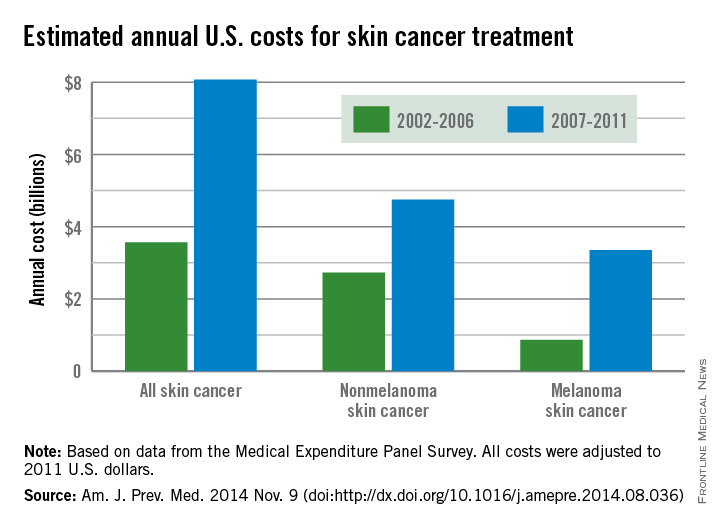

Skin cancer treatment costs skyrocket over past decade

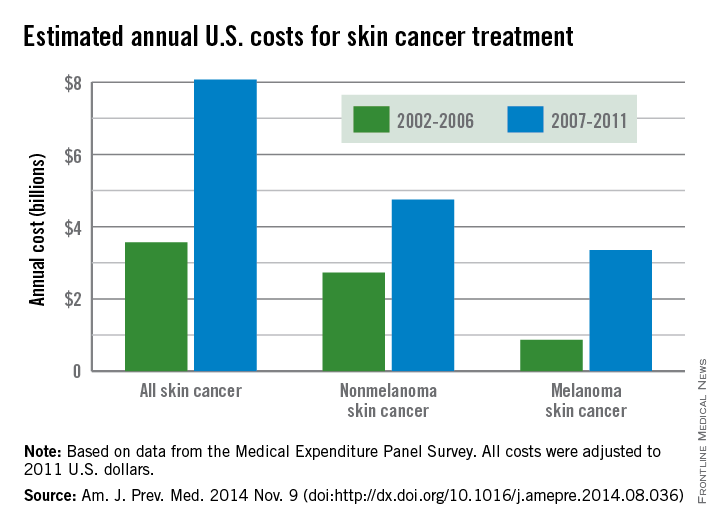

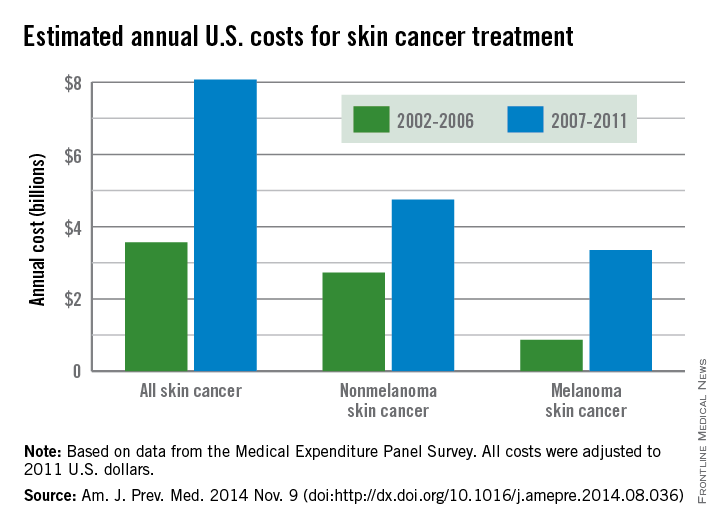

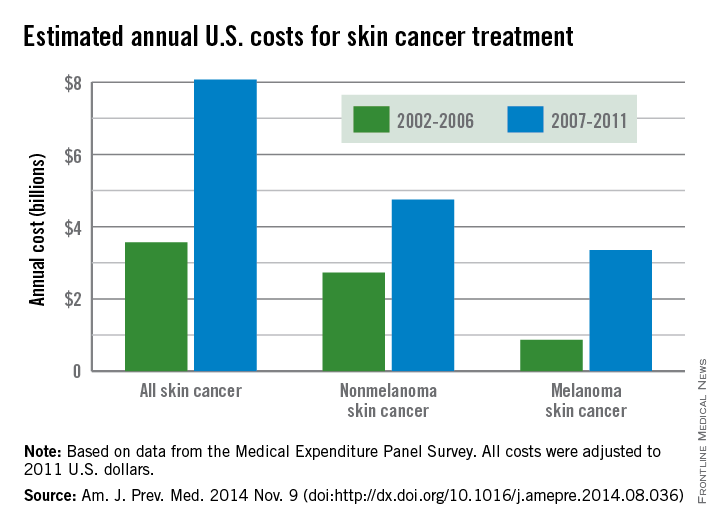

The average annual cost for skin cancer treatment more than doubled from 2002 to 2011, a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found.

From 2002 to 2006, the average annual skin cancer treatment cost was $3.6 billion, while for 2007-2011, the average annual cost was $8.1 billion, an increase of about 126%. The cost of nonmelanoma skin cancers increased 74%, from $2.7 billion to $4.8 billion, but the average annual cost for melanoma cancers increased about 280%, from $864 million to $3.3 billion, according to the CDC (Am. J. Prev. Med. 2014 Nov. 9 [doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2014.08.036]).

From 2002 to 2006, the average annual number of adults treated for skin cancer was 3.4 million, which increased to an average annual number of 4.9 million for 2007-2011. The average annual cost per person for all skin cancers increased by 57%, from $1,044 for 2002-2006 to $1,643 for 2007-2011, while the average cost for melanomas more than doubled from $2,320 to $4,780. The increase in annual cost for nonmelanoma skin cancers was more modest; only a 25% increase, from $882 to $1,105, was noted between the two time periods, the CDC reported.

The average annual cost for all cancer treatment rose from $67.3 billion for 2002-2006 to $87.8 billion for 2007-2011, an increase of $20.5 billion. While skin cancer treatment costs represented only 5% of all treatment costs in 2002-2006, the increase in skin cancer costs was 22% of the total increase, so from 2007 to 2011, skin cancer represented 9% of all treatment costs, according to data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey.

The average annual cost for skin cancer treatment more than doubled from 2002 to 2011, a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found.

From 2002 to 2006, the average annual skin cancer treatment cost was $3.6 billion, while for 2007-2011, the average annual cost was $8.1 billion, an increase of about 126%. The cost of nonmelanoma skin cancers increased 74%, from $2.7 billion to $4.8 billion, but the average annual cost for melanoma cancers increased about 280%, from $864 million to $3.3 billion, according to the CDC (Am. J. Prev. Med. 2014 Nov. 9 [doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2014.08.036]).

From 2002 to 2006, the average annual number of adults treated for skin cancer was 3.4 million, which increased to an average annual number of 4.9 million for 2007-2011. The average annual cost per person for all skin cancers increased by 57%, from $1,044 for 2002-2006 to $1,643 for 2007-2011, while the average cost for melanomas more than doubled from $2,320 to $4,780. The increase in annual cost for nonmelanoma skin cancers was more modest; only a 25% increase, from $882 to $1,105, was noted between the two time periods, the CDC reported.

The average annual cost for all cancer treatment rose from $67.3 billion for 2002-2006 to $87.8 billion for 2007-2011, an increase of $20.5 billion. While skin cancer treatment costs represented only 5% of all treatment costs in 2002-2006, the increase in skin cancer costs was 22% of the total increase, so from 2007 to 2011, skin cancer represented 9% of all treatment costs, according to data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey.

The average annual cost for skin cancer treatment more than doubled from 2002 to 2011, a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found.

From 2002 to 2006, the average annual skin cancer treatment cost was $3.6 billion, while for 2007-2011, the average annual cost was $8.1 billion, an increase of about 126%. The cost of nonmelanoma skin cancers increased 74%, from $2.7 billion to $4.8 billion, but the average annual cost for melanoma cancers increased about 280%, from $864 million to $3.3 billion, according to the CDC (Am. J. Prev. Med. 2014 Nov. 9 [doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2014.08.036]).

From 2002 to 2006, the average annual number of adults treated for skin cancer was 3.4 million, which increased to an average annual number of 4.9 million for 2007-2011. The average annual cost per person for all skin cancers increased by 57%, from $1,044 for 2002-2006 to $1,643 for 2007-2011, while the average cost for melanomas more than doubled from $2,320 to $4,780. The increase in annual cost for nonmelanoma skin cancers was more modest; only a 25% increase, from $882 to $1,105, was noted between the two time periods, the CDC reported.

The average annual cost for all cancer treatment rose from $67.3 billion for 2002-2006 to $87.8 billion for 2007-2011, an increase of $20.5 billion. While skin cancer treatment costs represented only 5% of all treatment costs in 2002-2006, the increase in skin cancer costs was 22% of the total increase, so from 2007 to 2011, skin cancer represented 9% of all treatment costs, according to data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey.

FROM THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF PREVENTIVE MEDICINE

Efficacy of Cryosurgery and 5-Fluorouracil Cream 0.5% Combination Therapy for the Treatment of Actinic Keratosis

Actinic keratosis (AK) is regarded as a lesion on a continuum of progression to squamous cell carcinoma (SCC).1 Studies have estimated that 44% to 97% of SCCs were associated with AK lesions either in contiguous skin or within the same histologic section and that AK lesions progress to SCCs at a rate of 0.6% at 1 year.2 In 1993-1994 there were 3.7 million reported office visits for AK lesions, while in 2002 alone there were 8.2 million office visits.3,4 As the burden of disease from AKs has increased, so has the associated costs from office-based visits, treatments, and subsequent surveillance.

There are a number of highly effective approaches to AK treatment that are based on several factors such as the number of and extent of the lesions, history of skin cancer, provider practice characteristics (eg, location, appointment availability), patient preferences, cost, and tolerability. Cryosurgery is the most commonly used lesion-directed modality in the treatment of individual AKs based on its effectiveness and relative ease of use. Cryosurgery alone has been shown to have a success rate of 67% on AK lesions.5 Patients often experience erythema, edema, pain, and crusting at treated sites; there also is potential for ulceration, scarring, hypopigmentation, hyperpigmentation, and secondary infection, but these effects are less common. Recurrence may be an indicator of treatment-resistant lesions or new lesions appearing in the field.

A field-directed approach with topical 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) may be preferred in patients with a history of substantial photodamage, AKs that are resistant to cryosurgery, or multiple AKs. Field-directed treatments address multiple AKs simultaneously and treat subclinical lesions. Fluorouracil is a common therapy for AKs that often is implemented by dermatologists due to its efficacy and well-understood mechanism of action. Fluorouracil inhibits thymidylate synthase during DNA synthesis, thereby halting cellular proliferation. 5-Fluorouracil cream 0.5% has been approved for 1-, 2-, and 4-week treatment periods. In one study, resolution of AK lesions was greatest in the 4-week treatment group; however, side effects also were greatest in this group.6 Patients commonly may experience a range of local reactions including erythema, pruritus, erosions, ulcerations, scabbing, crusting, and facial irritation. For patients with substantial photodamage and AKs, a robust response can lead to perceived adverse events (AEs) and considerable downtime, possibly affecting patient satisfaction and treatment compliance.7

Many alternative and combination approaches have been studied to decrease AEs and improve compliance and efficacy in the treatment of AKs. In this study, we examined the efficacy and perceived side effects of cryosurgery and 5-FU cream 0.5% combination therapy in the treatment of AKs.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

This single-blind, single-center, comparator cream–controlled pilot study was parallel designed with a balanced randomization (1:1 frequency). The study protocol and consent form were approved by the Wake Forest University Health Sciences institutional review board (Winston-Salem, North Carolina). Participants were 18 years or older with 8 clinically typical, visible, and discrete AK lesions on the face (forehead and temples) or balding scalp. Typical inclusion and exclusion criteria were observed. No other topical agents or therapies were permitted to be applied to the affected areas at least 4 weeks prior to treatment, depending on the treatment modality.

Assessment

During the screening (baseline) visit, eligible participants provided informed consent, baseline lesion counts and investigator global assessments (IGAs) were performed, and cryosurgery was administered to all visible AK lesions in the study areas. Participants returned at weeks 3, 4, 8, and 26. Three weeks following cryosurgery, participants were randomized according to standard randomization tables into 1 of 2 treatment groups to receive once-daily treatment with either 5-FU cream 0.5% or a moisturizing comparator cream. The cream was applied at bedtime to the affected sites for 1 week. Randomization was investigator blinded, but participants and the study administrators were not blinded. Participants were instructed to record their treatment compliance in daily diary entries, which were reviewed at week 4 using the medication tolerability assessment rating for burning, stinging, and ulceration. Investigator global assessment, IGA of improvement, lesion counts, and quality of life (QOL) survey responses were gathered at weeks 3, 8, and 26. The IGA measured the overall severity of AK disease involvement on a 6-point scale (clear; very severe). The IGA of improvement measured the overall improvement from baseline on a 6-point scale (clear; worse). Adverse events were measured at each visit.

Efficacy End Points

The primary end point was 100% clearance of all AK lesions at the end of the study (week 26) relative to the baseline AK lesion count. Secondary end points included comparisons between the groups for the number of participants with greater than 75% reduction of baseline lesion counts at the end of the study as well as differences at each visit in medication tolerability assessments, QOL measures, IGA improvement scores, and medication adherence based on diary entries at week 4.

Statistical Analysis

An intention-to-treat analysis was performed. The number of participants with 100% or greater than 75% clearance of AK lesions by specified time points were compared using relative risks and risk differences with Poisson regression analysis log and identity link functions, respectively, to obtain robust error variance 95% confidence intervals. Medication tolerability assessment, QOL, and IGA improvement scores were compared between the 2 groups using the Mann-Whitney U test. The significance level was set at α=.05. All analyses were performed using SAS data analysis software.

Results

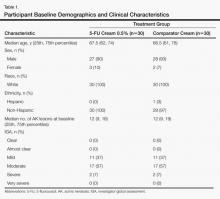

Sixty age-eligible participants were enrolled in the study with 30 participants in each treatment group. All of the participants completed the 26-week study period and were included in the intention-to-treat analysis. All of the participants were white with a median age of 67 years; the median number of baseline AK lesions was 12. Participant baseline demographics and clinical characteristics are provided in Table 1. Treatment compliance in both groups was good with only a few participants reporting missed doses.

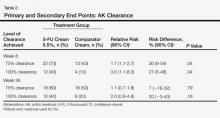

In our evaluation of the rate of change in the number of AK lesions at week 8 compared to baseline, the 5-FU cream 0.5% group showed an 84% reduction in the number of AK lesions versus a 69% reduction in the control group. At week 26, the 5-FU cream 0.5% group showed a 72% reduction in the number of lesions versus 73% in the control group. There was no significant difference between 5-FU cream 0.5% and the comparator cream for either 100% or 75% clearance of AK lesions by the end of the study; however, comparing the AK lesion count from baseline to 8 weeks following the initiation of the study, participants in the 5-FU cream 0.5% group were more likely than the control group to achieve 75% or 100% clearance on the relative risk and risk difference scales (Table 2).

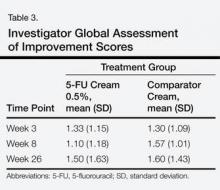

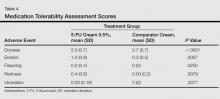

There were no significant differences between the 2 groups for the IGA of improvement at any time point (Table 3). On average, participants in the 5-FU cream 0.5% group experienced more dryness, erosion, fissuring, and redness than the control group but not more ulcerations by the end of week 4 (Table 4). All other QOL measures were statistically comparable between the 2 treatment groups for all time points.

A total of 25 AEs were reported throughout the study but none were considered to be serious. One AE (redness, burning, and itching over the eyebrow) was considered to be related to the study drug. No participants withdrew from the study due to AEs. A total of 12 participants in the 5-FU cream 0.5% group and 10 in the control group reported AEs.

Comment

After a 1-week course of 5-FU cream 0.5% following cryosurgery, a greater reduction in the number of AK lesions for a period of 2 months was noted in the treatment group compared to the control group. These findings are consistent with a similar study from 2006 that used 5-FU cream 0.5% or a vehicle 1 week prior to cryosurgery and then counted the number of AK lesions that remained.8 In the 2006 study, remarkable improvement out to week 26 was noted,8 unlike our study; however, there was insufficient power in our study to demonstrate a continued effect out to week 26.

Both the 2006 study and our current study support the benefit of using a combination treatment to clear AK lesions versus either treatment alone. Of note, these studies also show that combination treatments are equally effective, regardless of the order of treatments, in lowering AK lesion counts compared to cryosurgery alone.

Although participants in the 5-FU cream 0.5% group reported slightly more AEs on average at week 4, the rate of side effects was lower than those reported in a study documenting the side effects of a 4-week course of 5-FU.6 This rate of side effects must be considered in light of the added benefits this combination treatment has demonstrated.

Results of this pilot study suggest that a larger sample size would yield a difference in the study arms for all time periods (weeks 8 and 26). In an effort to maintain exchangeability of the study arms, patients were randomized at baseline treatment, but behaviors of patients in the 6 months following treatment, such as variation in sun exposure or other habits that promote AK lesion development, may have attenuated the results.

Key strengths of this study include no loss to follow-up and high medication adherence rates. The key limitation was the small sample size, which did not demonstrate a statistical advantage of the 5-FU cream 0.5% at 26 weeks; however, our study does show promise for larger future studies in illustrating this difference. A study by Krawtchenko et al9 noted that long-term efficacy of field therapy with 5-FU may ultimately be less than imiquimod cream 5%, suggesting that a possible alteration of the study protocol to compare the efficacy of different forms of field therapy may ultimately achieve better outcomes.

Conclusion

Overall, individuals with AK may benefit from a combination of treatment with cryosurgery and topical 5-FU to resolve lesions for longer periods than with cryosurgery alone. Although prior studies have found statistically significant differences in short-term and long-term treatment efficacy when cryosurgery is combined with an active field therapy versus a placebo vehicle,8,9 the current study aimed to find the best combination of efficacy with the fewest side effects. Therefore, the results of prior literature studies only further the feelings of the authors that with a protocol that looks at a slightly different treatment regimen within the treatment arm, the results can be extremely beneficial to patients. Further studies should be implemented to confirm the longer-term benefits of this combination therapy.

1. Lebwohl M. Actinic keratosis: epidemiology and progression to squamous cell carcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149(suppl 66):31-33.

2. Criscione VD, Weinstock MA, Naylor MF, et al. Actinic keratoses: natural history and risk of malignant transformation in the Veterans Affairs Topical Tretinoin Chemoprevention Trial. Cancer. 2009;115:2523-2530.

3. Smith ES, Feldman SR, Fleischer AB Jr, et al. Characteristics of office-based visits for skin cancer. dermatologists have more experience than other physicians in managing malignant and premalignant skin conditions. Dermatol Surg. 1998;24:981-985.

4. Shoimer I, Rosen N, Muhn C. Current management of actinic keratoses. Skin Therapy Lett. 2010;15:5-7.

5. Thai KE, Fergin P, Freeman M, et al. A prospective study of the use of cryosurgery for the treatment of actinic keratoses. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:687-692.

6. Weiss J, Menter A, Hevia O, et al. Effective treatment of actinic keratosis with 0.5% fluorouracil cream for 1, 2, or 4 weeks. Cutis. 2002;70(suppl 2):22-29.

7. Jorizzo JL, Carney PS, Ko WT, et al. Treatment options in the management of actinic keratosis. Cutis. 2004;74 (suppl 6):9-17.

8. Jorizzo J, Weiss J, Vamvakias G. One-week treatment with 0.5% fluorouracil cream prior to cryosurgery in patients with actinic keratoses: a double-blind, vehicle-controlled, long-term study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2006;5:133-139.

9. Krawtchenko N, Roewert-Huber J, Ulrich M, et al. A randomised study of topical 5% imiquimod vs. topical 5-fluorouracil vs. cryosurgery in immunocompetent patients with actinic keratoses: a comparison of clinical and histological outcomes including 1-year follow-up. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157(suppl 2):34-40.

Actinic keratosis (AK) is regarded as a lesion on a continuum of progression to squamous cell carcinoma (SCC).1 Studies have estimated that 44% to 97% of SCCs were associated with AK lesions either in contiguous skin or within the same histologic section and that AK lesions progress to SCCs at a rate of 0.6% at 1 year.2 In 1993-1994 there were 3.7 million reported office visits for AK lesions, while in 2002 alone there were 8.2 million office visits.3,4 As the burden of disease from AKs has increased, so has the associated costs from office-based visits, treatments, and subsequent surveillance.

There are a number of highly effective approaches to AK treatment that are based on several factors such as the number of and extent of the lesions, history of skin cancer, provider practice characteristics (eg, location, appointment availability), patient preferences, cost, and tolerability. Cryosurgery is the most commonly used lesion-directed modality in the treatment of individual AKs based on its effectiveness and relative ease of use. Cryosurgery alone has been shown to have a success rate of 67% on AK lesions.5 Patients often experience erythema, edema, pain, and crusting at treated sites; there also is potential for ulceration, scarring, hypopigmentation, hyperpigmentation, and secondary infection, but these effects are less common. Recurrence may be an indicator of treatment-resistant lesions or new lesions appearing in the field.

A field-directed approach with topical 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) may be preferred in patients with a history of substantial photodamage, AKs that are resistant to cryosurgery, or multiple AKs. Field-directed treatments address multiple AKs simultaneously and treat subclinical lesions. Fluorouracil is a common therapy for AKs that often is implemented by dermatologists due to its efficacy and well-understood mechanism of action. Fluorouracil inhibits thymidylate synthase during DNA synthesis, thereby halting cellular proliferation. 5-Fluorouracil cream 0.5% has been approved for 1-, 2-, and 4-week treatment periods. In one study, resolution of AK lesions was greatest in the 4-week treatment group; however, side effects also were greatest in this group.6 Patients commonly may experience a range of local reactions including erythema, pruritus, erosions, ulcerations, scabbing, crusting, and facial irritation. For patients with substantial photodamage and AKs, a robust response can lead to perceived adverse events (AEs) and considerable downtime, possibly affecting patient satisfaction and treatment compliance.7

Many alternative and combination approaches have been studied to decrease AEs and improve compliance and efficacy in the treatment of AKs. In this study, we examined the efficacy and perceived side effects of cryosurgery and 5-FU cream 0.5% combination therapy in the treatment of AKs.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

This single-blind, single-center, comparator cream–controlled pilot study was parallel designed with a balanced randomization (1:1 frequency). The study protocol and consent form were approved by the Wake Forest University Health Sciences institutional review board (Winston-Salem, North Carolina). Participants were 18 years or older with 8 clinically typical, visible, and discrete AK lesions on the face (forehead and temples) or balding scalp. Typical inclusion and exclusion criteria were observed. No other topical agents or therapies were permitted to be applied to the affected areas at least 4 weeks prior to treatment, depending on the treatment modality.

Assessment

During the screening (baseline) visit, eligible participants provided informed consent, baseline lesion counts and investigator global assessments (IGAs) were performed, and cryosurgery was administered to all visible AK lesions in the study areas. Participants returned at weeks 3, 4, 8, and 26. Three weeks following cryosurgery, participants were randomized according to standard randomization tables into 1 of 2 treatment groups to receive once-daily treatment with either 5-FU cream 0.5% or a moisturizing comparator cream. The cream was applied at bedtime to the affected sites for 1 week. Randomization was investigator blinded, but participants and the study administrators were not blinded. Participants were instructed to record their treatment compliance in daily diary entries, which were reviewed at week 4 using the medication tolerability assessment rating for burning, stinging, and ulceration. Investigator global assessment, IGA of improvement, lesion counts, and quality of life (QOL) survey responses were gathered at weeks 3, 8, and 26. The IGA measured the overall severity of AK disease involvement on a 6-point scale (clear; very severe). The IGA of improvement measured the overall improvement from baseline on a 6-point scale (clear; worse). Adverse events were measured at each visit.

Efficacy End Points

The primary end point was 100% clearance of all AK lesions at the end of the study (week 26) relative to the baseline AK lesion count. Secondary end points included comparisons between the groups for the number of participants with greater than 75% reduction of baseline lesion counts at the end of the study as well as differences at each visit in medication tolerability assessments, QOL measures, IGA improvement scores, and medication adherence based on diary entries at week 4.

Statistical Analysis

An intention-to-treat analysis was performed. The number of participants with 100% or greater than 75% clearance of AK lesions by specified time points were compared using relative risks and risk differences with Poisson regression analysis log and identity link functions, respectively, to obtain robust error variance 95% confidence intervals. Medication tolerability assessment, QOL, and IGA improvement scores were compared between the 2 groups using the Mann-Whitney U test. The significance level was set at α=.05. All analyses were performed using SAS data analysis software.

Results

Sixty age-eligible participants were enrolled in the study with 30 participants in each treatment group. All of the participants completed the 26-week study period and were included in the intention-to-treat analysis. All of the participants were white with a median age of 67 years; the median number of baseline AK lesions was 12. Participant baseline demographics and clinical characteristics are provided in Table 1. Treatment compliance in both groups was good with only a few participants reporting missed doses.

In our evaluation of the rate of change in the number of AK lesions at week 8 compared to baseline, the 5-FU cream 0.5% group showed an 84% reduction in the number of AK lesions versus a 69% reduction in the control group. At week 26, the 5-FU cream 0.5% group showed a 72% reduction in the number of lesions versus 73% in the control group. There was no significant difference between 5-FU cream 0.5% and the comparator cream for either 100% or 75% clearance of AK lesions by the end of the study; however, comparing the AK lesion count from baseline to 8 weeks following the initiation of the study, participants in the 5-FU cream 0.5% group were more likely than the control group to achieve 75% or 100% clearance on the relative risk and risk difference scales (Table 2).

There were no significant differences between the 2 groups for the IGA of improvement at any time point (Table 3). On average, participants in the 5-FU cream 0.5% group experienced more dryness, erosion, fissuring, and redness than the control group but not more ulcerations by the end of week 4 (Table 4). All other QOL measures were statistically comparable between the 2 treatment groups for all time points.

A total of 25 AEs were reported throughout the study but none were considered to be serious. One AE (redness, burning, and itching over the eyebrow) was considered to be related to the study drug. No participants withdrew from the study due to AEs. A total of 12 participants in the 5-FU cream 0.5% group and 10 in the control group reported AEs.

Comment

After a 1-week course of 5-FU cream 0.5% following cryosurgery, a greater reduction in the number of AK lesions for a period of 2 months was noted in the treatment group compared to the control group. These findings are consistent with a similar study from 2006 that used 5-FU cream 0.5% or a vehicle 1 week prior to cryosurgery and then counted the number of AK lesions that remained.8 In the 2006 study, remarkable improvement out to week 26 was noted,8 unlike our study; however, there was insufficient power in our study to demonstrate a continued effect out to week 26.

Both the 2006 study and our current study support the benefit of using a combination treatment to clear AK lesions versus either treatment alone. Of note, these studies also show that combination treatments are equally effective, regardless of the order of treatments, in lowering AK lesion counts compared to cryosurgery alone.

Although participants in the 5-FU cream 0.5% group reported slightly more AEs on average at week 4, the rate of side effects was lower than those reported in a study documenting the side effects of a 4-week course of 5-FU.6 This rate of side effects must be considered in light of the added benefits this combination treatment has demonstrated.

Results of this pilot study suggest that a larger sample size would yield a difference in the study arms for all time periods (weeks 8 and 26). In an effort to maintain exchangeability of the study arms, patients were randomized at baseline treatment, but behaviors of patients in the 6 months following treatment, such as variation in sun exposure or other habits that promote AK lesion development, may have attenuated the results.

Key strengths of this study include no loss to follow-up and high medication adherence rates. The key limitation was the small sample size, which did not demonstrate a statistical advantage of the 5-FU cream 0.5% at 26 weeks; however, our study does show promise for larger future studies in illustrating this difference. A study by Krawtchenko et al9 noted that long-term efficacy of field therapy with 5-FU may ultimately be less than imiquimod cream 5%, suggesting that a possible alteration of the study protocol to compare the efficacy of different forms of field therapy may ultimately achieve better outcomes.

Conclusion

Overall, individuals with AK may benefit from a combination of treatment with cryosurgery and topical 5-FU to resolve lesions for longer periods than with cryosurgery alone. Although prior studies have found statistically significant differences in short-term and long-term treatment efficacy when cryosurgery is combined with an active field therapy versus a placebo vehicle,8,9 the current study aimed to find the best combination of efficacy with the fewest side effects. Therefore, the results of prior literature studies only further the feelings of the authors that with a protocol that looks at a slightly different treatment regimen within the treatment arm, the results can be extremely beneficial to patients. Further studies should be implemented to confirm the longer-term benefits of this combination therapy.

Actinic keratosis (AK) is regarded as a lesion on a continuum of progression to squamous cell carcinoma (SCC).1 Studies have estimated that 44% to 97% of SCCs were associated with AK lesions either in contiguous skin or within the same histologic section and that AK lesions progress to SCCs at a rate of 0.6% at 1 year.2 In 1993-1994 there were 3.7 million reported office visits for AK lesions, while in 2002 alone there were 8.2 million office visits.3,4 As the burden of disease from AKs has increased, so has the associated costs from office-based visits, treatments, and subsequent surveillance.

There are a number of highly effective approaches to AK treatment that are based on several factors such as the number of and extent of the lesions, history of skin cancer, provider practice characteristics (eg, location, appointment availability), patient preferences, cost, and tolerability. Cryosurgery is the most commonly used lesion-directed modality in the treatment of individual AKs based on its effectiveness and relative ease of use. Cryosurgery alone has been shown to have a success rate of 67% on AK lesions.5 Patients often experience erythema, edema, pain, and crusting at treated sites; there also is potential for ulceration, scarring, hypopigmentation, hyperpigmentation, and secondary infection, but these effects are less common. Recurrence may be an indicator of treatment-resistant lesions or new lesions appearing in the field.

A field-directed approach with topical 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) may be preferred in patients with a history of substantial photodamage, AKs that are resistant to cryosurgery, or multiple AKs. Field-directed treatments address multiple AKs simultaneously and treat subclinical lesions. Fluorouracil is a common therapy for AKs that often is implemented by dermatologists due to its efficacy and well-understood mechanism of action. Fluorouracil inhibits thymidylate synthase during DNA synthesis, thereby halting cellular proliferation. 5-Fluorouracil cream 0.5% has been approved for 1-, 2-, and 4-week treatment periods. In one study, resolution of AK lesions was greatest in the 4-week treatment group; however, side effects also were greatest in this group.6 Patients commonly may experience a range of local reactions including erythema, pruritus, erosions, ulcerations, scabbing, crusting, and facial irritation. For patients with substantial photodamage and AKs, a robust response can lead to perceived adverse events (AEs) and considerable downtime, possibly affecting patient satisfaction and treatment compliance.7

Many alternative and combination approaches have been studied to decrease AEs and improve compliance and efficacy in the treatment of AKs. In this study, we examined the efficacy and perceived side effects of cryosurgery and 5-FU cream 0.5% combination therapy in the treatment of AKs.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

This single-blind, single-center, comparator cream–controlled pilot study was parallel designed with a balanced randomization (1:1 frequency). The study protocol and consent form were approved by the Wake Forest University Health Sciences institutional review board (Winston-Salem, North Carolina). Participants were 18 years or older with 8 clinically typical, visible, and discrete AK lesions on the face (forehead and temples) or balding scalp. Typical inclusion and exclusion criteria were observed. No other topical agents or therapies were permitted to be applied to the affected areas at least 4 weeks prior to treatment, depending on the treatment modality.

Assessment

During the screening (baseline) visit, eligible participants provided informed consent, baseline lesion counts and investigator global assessments (IGAs) were performed, and cryosurgery was administered to all visible AK lesions in the study areas. Participants returned at weeks 3, 4, 8, and 26. Three weeks following cryosurgery, participants were randomized according to standard randomization tables into 1 of 2 treatment groups to receive once-daily treatment with either 5-FU cream 0.5% or a moisturizing comparator cream. The cream was applied at bedtime to the affected sites for 1 week. Randomization was investigator blinded, but participants and the study administrators were not blinded. Participants were instructed to record their treatment compliance in daily diary entries, which were reviewed at week 4 using the medication tolerability assessment rating for burning, stinging, and ulceration. Investigator global assessment, IGA of improvement, lesion counts, and quality of life (QOL) survey responses were gathered at weeks 3, 8, and 26. The IGA measured the overall severity of AK disease involvement on a 6-point scale (clear; very severe). The IGA of improvement measured the overall improvement from baseline on a 6-point scale (clear; worse). Adverse events were measured at each visit.

Efficacy End Points

The primary end point was 100% clearance of all AK lesions at the end of the study (week 26) relative to the baseline AK lesion count. Secondary end points included comparisons between the groups for the number of participants with greater than 75% reduction of baseline lesion counts at the end of the study as well as differences at each visit in medication tolerability assessments, QOL measures, IGA improvement scores, and medication adherence based on diary entries at week 4.

Statistical Analysis

An intention-to-treat analysis was performed. The number of participants with 100% or greater than 75% clearance of AK lesions by specified time points were compared using relative risks and risk differences with Poisson regression analysis log and identity link functions, respectively, to obtain robust error variance 95% confidence intervals. Medication tolerability assessment, QOL, and IGA improvement scores were compared between the 2 groups using the Mann-Whitney U test. The significance level was set at α=.05. All analyses were performed using SAS data analysis software.

Results

Sixty age-eligible participants were enrolled in the study with 30 participants in each treatment group. All of the participants completed the 26-week study period and were included in the intention-to-treat analysis. All of the participants were white with a median age of 67 years; the median number of baseline AK lesions was 12. Participant baseline demographics and clinical characteristics are provided in Table 1. Treatment compliance in both groups was good with only a few participants reporting missed doses.

In our evaluation of the rate of change in the number of AK lesions at week 8 compared to baseline, the 5-FU cream 0.5% group showed an 84% reduction in the number of AK lesions versus a 69% reduction in the control group. At week 26, the 5-FU cream 0.5% group showed a 72% reduction in the number of lesions versus 73% in the control group. There was no significant difference between 5-FU cream 0.5% and the comparator cream for either 100% or 75% clearance of AK lesions by the end of the study; however, comparing the AK lesion count from baseline to 8 weeks following the initiation of the study, participants in the 5-FU cream 0.5% group were more likely than the control group to achieve 75% or 100% clearance on the relative risk and risk difference scales (Table 2).

There were no significant differences between the 2 groups for the IGA of improvement at any time point (Table 3). On average, participants in the 5-FU cream 0.5% group experienced more dryness, erosion, fissuring, and redness than the control group but not more ulcerations by the end of week 4 (Table 4). All other QOL measures were statistically comparable between the 2 treatment groups for all time points.

A total of 25 AEs were reported throughout the study but none were considered to be serious. One AE (redness, burning, and itching over the eyebrow) was considered to be related to the study drug. No participants withdrew from the study due to AEs. A total of 12 participants in the 5-FU cream 0.5% group and 10 in the control group reported AEs.

Comment