User login

Bipolar disorder or borderline personality disorder?

Although evidence suggests that bipolar disorder (BD) and borderline personality disorder (BPD) are distinct entities, their differential diagnosis is often challenging as a result of considerable overlap of phenotypical features. Moreover, BD and BPD frequently co-occur, which makes it even more difficult to differentiate these 2 conditions. Strategies for improving diagnostic accuracy are critical to optimizing patients’ clinical outcomes and long-term prognosis. Misdiagnosing these 2 conditions can be particularly deleterious, and failure to recognize their co-occurrence can result in additional burden to typically complex and severe clinical presentations.

This article describes key aspects of the differential diagnosis between BD and BPD, emphasizing core features and major dissimilarities between these 2 conditions, and discusses the implications of misdiagnosis. The goal is to highlight the clinical and psychopathological aspects of BD and BPD to help clinicians properly distinguish these 2 disorders.

Psychopathological and sociodemographic correlates

Bipolar disorder is a chronic and severe mental illness that is classified based on clusters of symptoms—manic, hypomanic, and depressive.1 It is among the 10 leading causes of disability worldwide, with significant morbidity arising from acute affective episodes and subacute states.2 Data suggest the lifetime prevalence of BPD is 2.1%, and subthreshold forms may affect an additional 2.4% of the US population.3 The onset of symptoms typically occurs during late adolescence or early adulthood, and mood lability and cyclothymic temperament are the most common prodromal features.4

In contrast, personality disorders, such as BPD, are characteristically pervasive and maladaptive patterns of emotional responses that usually deviate from an individual’s stage of development and cultural background.1 These disorders tend to cause significant impairment, particularly in personal, occupational, and social domains. Environmental factors, such as early childhood trauma, seem to play an important role in the genesis of personality disorders, which may be particularly relevant in BPD, a disorder characterized by marked impulsivity and a pattern of instability in personal relationships, self-image, and affect.1,5,6 Similarly to BD, BPD is also chronic and highly disabling.

According to the National Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC), approximately 15% of US adults were found to have at least one type of personality disorder, and 6% met criteria for a cluster B personality disorder (antisocial, borderline, narcissistic, and histrionic).7 The lifetime prevalence of BPD is nearly 2%, with higher estimates observed in psychiatric settings.7,8

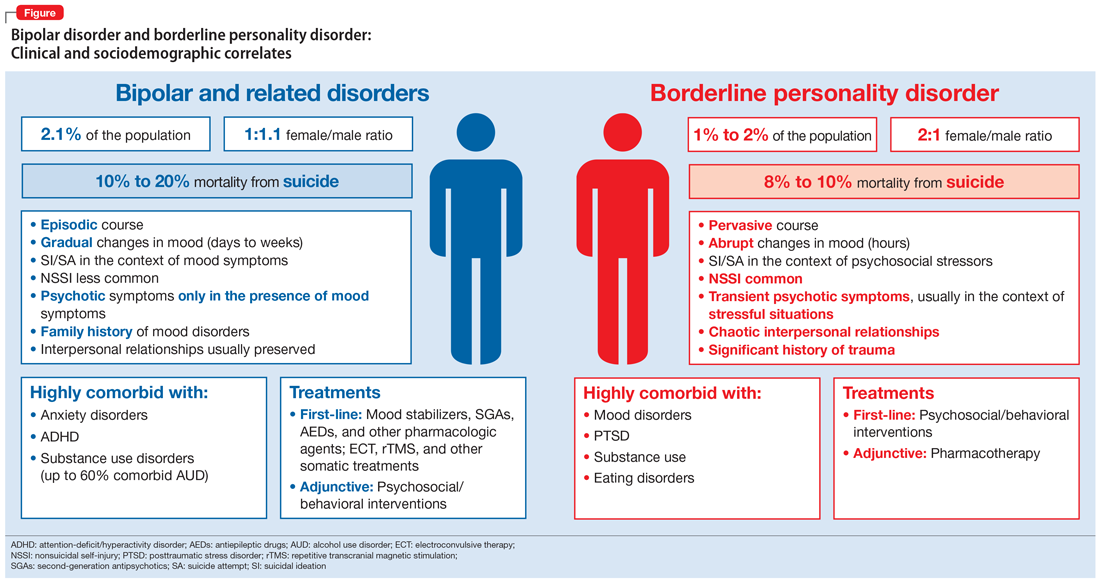

As a result of the phenotypical resemblance between BD and BPD (Figure), the differential diagnosis is often difficult. Recent studies suggest that co-occurrence of BD and BPD is common, with rates of comorbid BPD as high as 29% in BD I and 24% in BD II.8,9 On the other hand, nearly 20% of individuals with BPD seem to have comorbid BD.8,9 Several studies suggest that comorbid personality disorders represent a negative prognostic factor in the course of mood disorders, and the presence of BPD in patients with BD seems to be associated with more severe clinical presentations, greater treatment complexity, a higher number of depressive episodes, poor inter-episode functioning, and higher rates of other comorbidities, such as substance use disorders (SUDs).8-11 The effect of BD on the course of BPD is unclear and fairly unexplored, although it has been suggested that better control of mood symptoms may lead to more stable psychosocial functioning in BPD.9

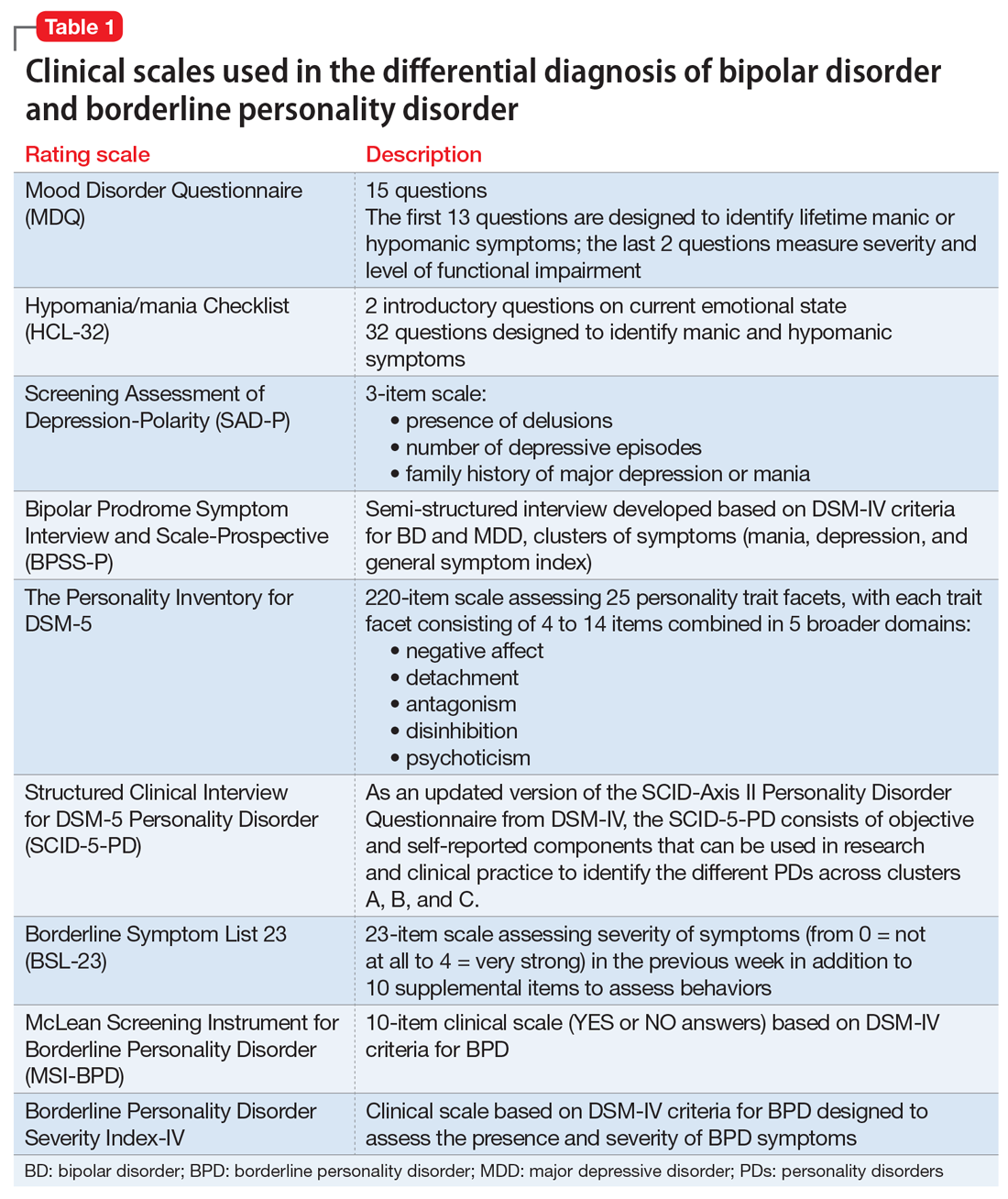

Whether BD and BPD are part of the same spectrum is a matter for debate.12-14 Multidimensional approaches have been proposed to better characterize these disorders in at-risk populations, based on structured interviews, self-administered and clinician-rated clinical scales (Table 1), neuroimaging studies, biological markers, and machine-learning models.15,16 Compelling evidence suggests that BD and BPD have distinct underlying neurobiological and psychopathological mechanisms12,13; however, the differential diagnosis still relies on phenotypical features, since the search for biological markers has not yet identified specific biomarkers that can be used in clinical practice.

Continue to: Core features of BPD...

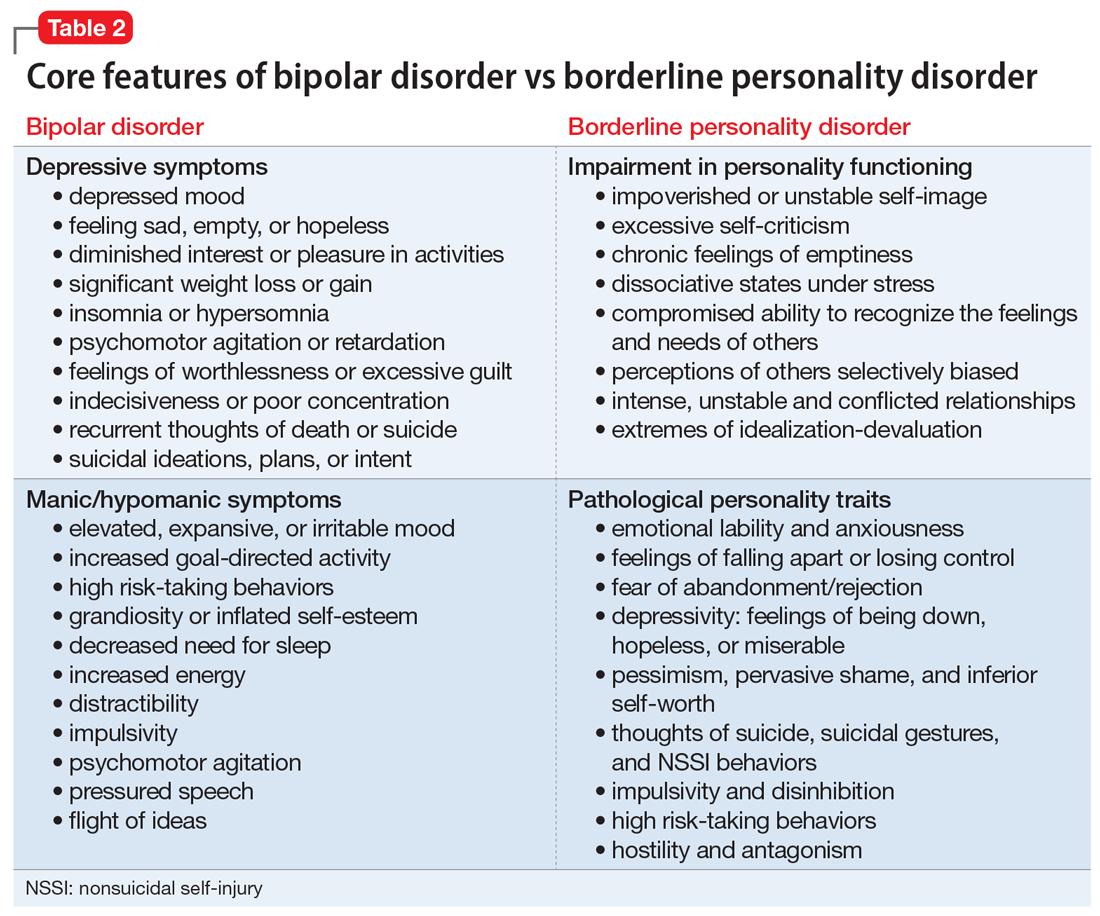

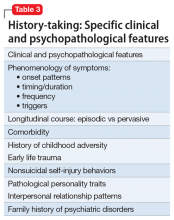

Core features of BPD, such as mood lability, impulsivity, and risk-taking behaviors, are also part of the diagnostic criteria for BD (Table 2).1 Similarly, depressive symptoms prevail in the course of BD.17,18 This adds complexity to the differential because “depressivity” is also part of the diagnostic criteria for BPD.1 Therefore, comprehensive psychiatric assessments and longitudinal observations are critical to diagnostic accuracy and treatment planning. Further characterization of symptoms, such as onset patterns, clinical course, phenomenology of symptoms (eg, timing, frequency, duration, triggers), and personality traits, will provide information to properly distinguish these 2 syndromes when, for example, it is unclear if the “mood swings” and impulsivity are part of a mood or a personality disorder (Table 3).

Clinical features: A closer look

Borderline personality disorder. Affect dysregulation, emotional instability, impoverished and unstable self-image, and chronic feelings of emptiness are core features of BPD.1,5,19 These characteristics, when combined with a fear of abandonment or rejection, a compromised ability to recognize the feelings and needs of others, and extremes of idealization-devaluation, tend to culminate in problematic and chaotic relationships.6,19 Individuals with BPD may become suspicious or paranoid under stressful situations. Under these circumstances, individuals with BPD may also experience depersonalization and other dissociative symptoms.6,20 The mood lability and emotional instability observed in patients with BPD usually are in response to environmental factors, and although generally intense and out of proportion, they tend to be ephemeral and short-lived, typically lasting a few hours.1,5 The anxiety and depressive symptoms reported by patients with BPD frequently are associated with feelings of “falling apart” or “losing control,” pessimism, shame, and low self-esteem. Coping strategies tend to be poorly developed and/or maladaptive, and individuals with BPD usually display a hostile and antagonistic demeanor and engage in suicidal or nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI) behaviors as means to alleviate overwhelming emotional distress. Impulsivity, disinhibition, poor tolerance to frustration, and risk-taking behaviors are also characteristic of BPD.1,5 As a result, BPD is usually associated with significant impairment in functioning, multiple hospitalizations, and high rates of comorbid mood disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), SUDs, and death by suicide.

Bipolar disorder. Conversely, the fluctuations in mood and affect observed in patients with BD are usually episodic rather than pervasive, and tend to last longer (typically days to weeks) compared with the transient mood shifts observed in patients with BPD.4,17,18 The impulsivity, psychomotor agitation, and increased goal-directed activity reported by patients with BD are usually seen in the context of an acute affective episode, and are far less common during periods of stability or euthymic affect.4,17,18 Grandiosity and inflated self-esteem—hallmarks of a manic or hypomanic state—seem to oppose the unstable self-image observed in BPD, although indecisiveness and low self-worth may be observed in individuals with BD during depressive episodes. Antidepressant-induced mania or hypomania, atypical depressive episodes, and disruptions in sleep and circadian rhythms may be predictors of BD.4,21 Furthermore, although psychosocial stressors may be associated with acute affective episodes in early stages of bipolar illness, over time minimal stressors are necessary to ignite new affective episodes.22,23 Although BD is associated with high rates of suicide, suicide attempts are usually seen in the context of an acute depressive episode, and NSSI behaviors are less common among patients with BD.24

Lastly, other biographical data, such as a history of early life trauma, comorbidity, and a family history of psychiatric illnesses, can be particularly helpful in establishing the differential diagnosis between BD and BPD.25 For instance, evidence suggests that the heritability of BD may be as high as 70%, which usually translates into an extensive family history of bipolar and related disorders.26 In addition, studies suggest a high co-occurrence of anxiety disorders, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and SUDs in patients with BD, whereas PTSD, SUDs, and eating disorders tend to be highly comorbid with BPD.27 Childhood adversity (ie, a history of physical, sexual, or emotional abuse, or neglect) seems to be pivotal in the genesis of BPD and may predispose these individuals to psychotic and dissociative symptoms, particularly those with a history of sexual abuse, while playing a more secondary role in BD.28-31

Implications of misdiagnosis

In the view of the limitations of the existing models, multidimensional approaches are necessary to improve diagnostic accuracy. Presently, the differential diagnosis of BD and BPD continues to rely on clinical findings and syndromic classifications. Misdiagnosing BD and BPD has adverse therapeutic and prognostic implications.32 For instance, while psychotropic medications and neuromodulatory therapies (eg, electroconvulsive therapy, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation) are considered first-line treatments for patients with BD, psychosocial interventions tend to be adjunctive treatments in BD.33 Conversely, although pharmacotherapy might be helpful for patients with BPD, psychosocial and behavioral interventions are the mainstay treatment for this disorder, with the strongest evidence supporting cognitive-behavioral therapy, dialectical behavioral therapy, mentalization-based therapy, and transference-focused therapy.34-36 Thus, misdiagnosing BD as BPD with comorbid depression may result in the use of antidepressants, which can be detrimental in BD. Antidepressant treatment of BD, particularly as monotherapy, has been associated with manic or hypomanic switch, mixed states, and frequent cycling.21 Moreover, delays in diagnosis and proper treatment of BD may result in protracted mood symptoms, prolonged affective episodes, higher rates of disability, functional impairment, and overall worse clinical outcomes.24 In addition, because behavioral and psychosocial interventions are usually adjunctive therapies rather than first-line interventions for patients with BD, misdiagnosing BPD as BD may ultimately prevent these individuals from receiving proper treatment, likely resulting in more severe functional impairment, multiple hospitalizations, self-inflicted injuries, and suicide attempts, since psychotropic medications are not particularly effective for improving self-efficacy and coping strategies, nor for correcting cognitive distortions, particularly in self-image, and pathological personality traits, all of which are critical aspects of BPD treatment.

Continue to: Several factors might...

Several factors might make clinicians reluctant to diagnose BPD, or bias them to diagnose BD more frequently. These include a lack of familiarity with the diagnostic criteria for BPD, the phenotypical resemblance between BP and BPD, or even concerns about the stigma and negative implications that are associated with a BPD diagnosis.32,37,38

Whereas BD is currently perceived as a condition with a strong biological basis, there are considerable misconceptions regarding BPD and its nature.4-6,22,26 As a consequence, individuals with BPD tend to be perceived as “difficult-to-treat,” “uncooperative,” or “attention-seeking.” These misconceptions may result in poor clinician-patient relationships, unmet clinical and psychiatric needs, and frustration for both clinicians and patients.37

Through advances in biological psychiatry, precision medicine may someday be a part of psychiatric practice. Biological “signatures” may eventually help clinicians in diagnosing and treating psychiatric disorders. Presently, however, rigorous history-taking and comprehensive clinical assessments are still the most powerful tools a clinician can use to accomplish these goals. Finally, destigmatizing psychiatric disorders and educating patients and clinicians are also critical to improving clinical outcomes and promoting mental health in a compassionate and empathetic fashion.

Bottom Line

Despite the phenotypical resemblance between bipolar disorder (BP) and borderline personality disorder (BPD), the 2 are independent conditions with distinct neurobiological and psychopathological underpinnings. Clinicians can use a rigorous assessment of pathological personality traits and characterization of symptoms, such as onset patterns, clinical course, and phenomenology, to properly distinguish between BP and BPD.

Related Resources

- Fiedorowicz JG, Black DW. Borderline, bipolar, or both? Frame your diagnosis on the patient history. Current Psychiatry. 2010; 9(1):21-24,29-32.

- Zimmerman M. Improving the recognition of borderline personality disorder. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(10):13-19.

- National Institute of Mental Health. Overview on bipolar disorder. www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/bipolar-disorder/index.shtml. Revised October 2018.

- National Institute of Mental Health. Overview on borderline personality disorder. www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/borderline-personality-disorder-fact-sheet/index.shtml.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Whiteford HA, Degenhardt L, Rehm J, et al. Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2013;382(9904):1575-1586.

3. Merikangas KR, Akiskal HS, Angst J, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of bipolar spectrum disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(5):543-552.

4. Malhi GS, Bargh DM, Coulston CM, et al. Predicting bipolar disorder on the basis of phenomenology: implications for prevention and early intervention. Bipolar Disord. 2014;16(5):455-470.

5. Skodol AE, Gunderson JG, Pfohl B, et al. The borderline diagnosis I: psychopathology. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;51(12):936-950.

6. Skodol AE, Siever LJ, Livesley WJ, et al. The borderline diagnosis II: biology, genetics, and clinical course. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;51(12):951-963.

7. Hasin DS, Grant BF. The National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) Waves 1 and 2: review and summary of findings. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2015;50(11):1609-1640.

8. McDermid J, Sareen J, El-Gabalawy R, et al. Co-morbidity of bipolar disorder and borderline personality disorder: findings from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Compr Psychiatry. 2015;58:18-28.

9. Gunderson JG, Weinberg I, Daversa MT, et al. Descriptive and longitudinal observations on the relationship of borderline personality disorder and bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(7):1173-1178.

10. Swartz HA, Pilkonis PA, Frank E, et al. Acute treatment outcomes in patients with bipolar I disorder and co-morbid borderline personality disorder receiving medication and psychotherapy. Bipolar Disord. 2005;7(2):192-197.

11. Riemann G, Weisscher N, Post RM, et al. The relationship between self-reported borderline personality features and prospective illness course in bipolar disorder. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2017;5(1):31.

12. de la Rosa I, Oquendo MA, García G, et al. Determining if borderline personality disorder and bipolar disorder are alternative expressions of the same disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2017;778(8):e994-e999. doi: 10.4088/JCP.16m11190.

13. di Giacomo E, Aspesi F, Fotiadou M, et al. Unblending borderline personality and bipolar disorders. J Psychiatr Res. 2017;91:90-97.

14. Parker G, Bayes A, McClure G, et al. Clinical status of comorbid bipolar disorder and borderline personality disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 2016;209(3):209-215.

15. Perez Arribas I, Goodwin GM, Geddes JR, et al. A signature-based machine learning model for distinguishing bipolar disorder and borderline personality disorder. Transl Psychiatry. 2018;8(1):274.

16. Insel T, Cuthbert B, Garvey M, et al. Research Domain Criteria (RDoC): toward a new classification framework for research on mental disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(7):748-751.

17. Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, et al. The long-term natural history of the weekly symptomatic status of bipolar I disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(6):530-537.

18. Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, et al. A prospective investigation of the natural history of the long-term weekly symptomatic status of bipolar II disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(3):261-269.

19. Oldham JM, Skodol AE, Bender DS. A current integrative perspective on personality disorders. American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc. 2005.

20. Herzog JI, Schmahl C. Adverse childhood experiences and the consequences on neurobiological, psychosocial, and somatic conditions across the lifespan. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:420.

21. Barbuti M, Pacchiarotti I, Vieta E, et al. Antidepressant-induced hypomania/mania in patients with major depression: evidence from the BRIDGE-II-MIX study. J Affect Disord. 2017;219:187-192.

22. Post RM. Mechanisms of illness progression in the recurrent affective disorders. Neurotox Res. 2010;18(3-4):256-271.

23. da Costa SC, Passos IC, Lowri C, et al. Refractory bipolar disorder and neuroprogression. Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacology Biol Psychiatry. 2016;70:103-110.

24. Crump C, Sundquist K, Winkleby MA, et al. Comorbidities and mortality in bipolar disorder: a Swedish national cohort study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(9):931-939.

25. Zimmerman M, Martinez JH, Morgan TA, et al. Distinguishing bipolar II depression from major depressive disorder with comorbid borderline personality disorder: demographic, clinical, and family history differences. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(9):880-886.

26. Hasler G, Drevets WC, Gould TD, et al. Toward constructing an endophenotype strategy for bipolar disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60(2):93-105.

27. Brieger P, Ehrt U, Marneros A. Frequency of comorbid personality disorders in bipolar and unipolar affective disorders. Compr Psychiatry. 2003;44(1):28-34.

28. Leverich GS, McElroy SL, Suppes T, et al. Early physical and sexual abuse associated with an adverse course of bipolar illness. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;51(4):288-297.

29. Leverich GS, Post RM. Course of bipolar illness after history of childhood trauma. Lancet. 2006;367(9516):1040-1042.

30. Golier JA, Yehuda R, Bierer LM, et al. The relationship of borderline personality disorder to posttraumatic stress disorder and traumatic events. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(11):2018-2024.

31. Nicol K, Pope M, Romaniuk L, et al. Childhood trauma, midbrain activation and psychotic symptoms in borderline personality disorder. Transl Psychiatry. 2015;5:e559. doi:10.1038/tp.2015.53.

32. Ruggero CJ, Zimmerman M, Chelminski I, et al. Borderline personality disorder and the misdiagnosis of bipolar disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 2010;44(6):405-408.

33. Geddes JR, Miklowitz DJ. Treatment of bipolar disorder. Lancet. 2013;381(9878):1672-1682.

34. McMain S, Korman LM, Dimeff L. Dialectical behavior therapy and the treatment of emotion dysregulation. J Clin Psychol. 2001;57(2):183-196.

35. Cristea IA, Gentili C, Cotet CD, et al. Efficacy of psychotherapies for borderline personality disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(4):319-328.

36. Linehan MM, Korslund KE, Harned MS, et al. Dialectical behavior therapy for high suicide risk in individuals with borderline personality disorder. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(75);475-482.

37. LeQuesne ER, Hersh RG. Disclosure of a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder. J Psychiatr Pract. 2004:10(3):170-176.

38. Young AH. Bipolar disorder: diagnostic conundrums and associated comorbidities. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(8):e26. doi:10.4088/jcp.7067br6c.

Although evidence suggests that bipolar disorder (BD) and borderline personality disorder (BPD) are distinct entities, their differential diagnosis is often challenging as a result of considerable overlap of phenotypical features. Moreover, BD and BPD frequently co-occur, which makes it even more difficult to differentiate these 2 conditions. Strategies for improving diagnostic accuracy are critical to optimizing patients’ clinical outcomes and long-term prognosis. Misdiagnosing these 2 conditions can be particularly deleterious, and failure to recognize their co-occurrence can result in additional burden to typically complex and severe clinical presentations.

This article describes key aspects of the differential diagnosis between BD and BPD, emphasizing core features and major dissimilarities between these 2 conditions, and discusses the implications of misdiagnosis. The goal is to highlight the clinical and psychopathological aspects of BD and BPD to help clinicians properly distinguish these 2 disorders.

Psychopathological and sociodemographic correlates

Bipolar disorder is a chronic and severe mental illness that is classified based on clusters of symptoms—manic, hypomanic, and depressive.1 It is among the 10 leading causes of disability worldwide, with significant morbidity arising from acute affective episodes and subacute states.2 Data suggest the lifetime prevalence of BPD is 2.1%, and subthreshold forms may affect an additional 2.4% of the US population.3 The onset of symptoms typically occurs during late adolescence or early adulthood, and mood lability and cyclothymic temperament are the most common prodromal features.4

In contrast, personality disorders, such as BPD, are characteristically pervasive and maladaptive patterns of emotional responses that usually deviate from an individual’s stage of development and cultural background.1 These disorders tend to cause significant impairment, particularly in personal, occupational, and social domains. Environmental factors, such as early childhood trauma, seem to play an important role in the genesis of personality disorders, which may be particularly relevant in BPD, a disorder characterized by marked impulsivity and a pattern of instability in personal relationships, self-image, and affect.1,5,6 Similarly to BD, BPD is also chronic and highly disabling.

According to the National Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC), approximately 15% of US adults were found to have at least one type of personality disorder, and 6% met criteria for a cluster B personality disorder (antisocial, borderline, narcissistic, and histrionic).7 The lifetime prevalence of BPD is nearly 2%, with higher estimates observed in psychiatric settings.7,8

As a result of the phenotypical resemblance between BD and BPD (Figure), the differential diagnosis is often difficult. Recent studies suggest that co-occurrence of BD and BPD is common, with rates of comorbid BPD as high as 29% in BD I and 24% in BD II.8,9 On the other hand, nearly 20% of individuals with BPD seem to have comorbid BD.8,9 Several studies suggest that comorbid personality disorders represent a negative prognostic factor in the course of mood disorders, and the presence of BPD in patients with BD seems to be associated with more severe clinical presentations, greater treatment complexity, a higher number of depressive episodes, poor inter-episode functioning, and higher rates of other comorbidities, such as substance use disorders (SUDs).8-11 The effect of BD on the course of BPD is unclear and fairly unexplored, although it has been suggested that better control of mood symptoms may lead to more stable psychosocial functioning in BPD.9

Whether BD and BPD are part of the same spectrum is a matter for debate.12-14 Multidimensional approaches have been proposed to better characterize these disorders in at-risk populations, based on structured interviews, self-administered and clinician-rated clinical scales (Table 1), neuroimaging studies, biological markers, and machine-learning models.15,16 Compelling evidence suggests that BD and BPD have distinct underlying neurobiological and psychopathological mechanisms12,13; however, the differential diagnosis still relies on phenotypical features, since the search for biological markers has not yet identified specific biomarkers that can be used in clinical practice.

Continue to: Core features of BPD...

Core features of BPD, such as mood lability, impulsivity, and risk-taking behaviors, are also part of the diagnostic criteria for BD (Table 2).1 Similarly, depressive symptoms prevail in the course of BD.17,18 This adds complexity to the differential because “depressivity” is also part of the diagnostic criteria for BPD.1 Therefore, comprehensive psychiatric assessments and longitudinal observations are critical to diagnostic accuracy and treatment planning. Further characterization of symptoms, such as onset patterns, clinical course, phenomenology of symptoms (eg, timing, frequency, duration, triggers), and personality traits, will provide information to properly distinguish these 2 syndromes when, for example, it is unclear if the “mood swings” and impulsivity are part of a mood or a personality disorder (Table 3).

Clinical features: A closer look

Borderline personality disorder. Affect dysregulation, emotional instability, impoverished and unstable self-image, and chronic feelings of emptiness are core features of BPD.1,5,19 These characteristics, when combined with a fear of abandonment or rejection, a compromised ability to recognize the feelings and needs of others, and extremes of idealization-devaluation, tend to culminate in problematic and chaotic relationships.6,19 Individuals with BPD may become suspicious or paranoid under stressful situations. Under these circumstances, individuals with BPD may also experience depersonalization and other dissociative symptoms.6,20 The mood lability and emotional instability observed in patients with BPD usually are in response to environmental factors, and although generally intense and out of proportion, they tend to be ephemeral and short-lived, typically lasting a few hours.1,5 The anxiety and depressive symptoms reported by patients with BPD frequently are associated with feelings of “falling apart” or “losing control,” pessimism, shame, and low self-esteem. Coping strategies tend to be poorly developed and/or maladaptive, and individuals with BPD usually display a hostile and antagonistic demeanor and engage in suicidal or nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI) behaviors as means to alleviate overwhelming emotional distress. Impulsivity, disinhibition, poor tolerance to frustration, and risk-taking behaviors are also characteristic of BPD.1,5 As a result, BPD is usually associated with significant impairment in functioning, multiple hospitalizations, and high rates of comorbid mood disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), SUDs, and death by suicide.

Bipolar disorder. Conversely, the fluctuations in mood and affect observed in patients with BD are usually episodic rather than pervasive, and tend to last longer (typically days to weeks) compared with the transient mood shifts observed in patients with BPD.4,17,18 The impulsivity, psychomotor agitation, and increased goal-directed activity reported by patients with BD are usually seen in the context of an acute affective episode, and are far less common during periods of stability or euthymic affect.4,17,18 Grandiosity and inflated self-esteem—hallmarks of a manic or hypomanic state—seem to oppose the unstable self-image observed in BPD, although indecisiveness and low self-worth may be observed in individuals with BD during depressive episodes. Antidepressant-induced mania or hypomania, atypical depressive episodes, and disruptions in sleep and circadian rhythms may be predictors of BD.4,21 Furthermore, although psychosocial stressors may be associated with acute affective episodes in early stages of bipolar illness, over time minimal stressors are necessary to ignite new affective episodes.22,23 Although BD is associated with high rates of suicide, suicide attempts are usually seen in the context of an acute depressive episode, and NSSI behaviors are less common among patients with BD.24

Lastly, other biographical data, such as a history of early life trauma, comorbidity, and a family history of psychiatric illnesses, can be particularly helpful in establishing the differential diagnosis between BD and BPD.25 For instance, evidence suggests that the heritability of BD may be as high as 70%, which usually translates into an extensive family history of bipolar and related disorders.26 In addition, studies suggest a high co-occurrence of anxiety disorders, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and SUDs in patients with BD, whereas PTSD, SUDs, and eating disorders tend to be highly comorbid with BPD.27 Childhood adversity (ie, a history of physical, sexual, or emotional abuse, or neglect) seems to be pivotal in the genesis of BPD and may predispose these individuals to psychotic and dissociative symptoms, particularly those with a history of sexual abuse, while playing a more secondary role in BD.28-31

Implications of misdiagnosis

In the view of the limitations of the existing models, multidimensional approaches are necessary to improve diagnostic accuracy. Presently, the differential diagnosis of BD and BPD continues to rely on clinical findings and syndromic classifications. Misdiagnosing BD and BPD has adverse therapeutic and prognostic implications.32 For instance, while psychotropic medications and neuromodulatory therapies (eg, electroconvulsive therapy, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation) are considered first-line treatments for patients with BD, psychosocial interventions tend to be adjunctive treatments in BD.33 Conversely, although pharmacotherapy might be helpful for patients with BPD, psychosocial and behavioral interventions are the mainstay treatment for this disorder, with the strongest evidence supporting cognitive-behavioral therapy, dialectical behavioral therapy, mentalization-based therapy, and transference-focused therapy.34-36 Thus, misdiagnosing BD as BPD with comorbid depression may result in the use of antidepressants, which can be detrimental in BD. Antidepressant treatment of BD, particularly as monotherapy, has been associated with manic or hypomanic switch, mixed states, and frequent cycling.21 Moreover, delays in diagnosis and proper treatment of BD may result in protracted mood symptoms, prolonged affective episodes, higher rates of disability, functional impairment, and overall worse clinical outcomes.24 In addition, because behavioral and psychosocial interventions are usually adjunctive therapies rather than first-line interventions for patients with BD, misdiagnosing BPD as BD may ultimately prevent these individuals from receiving proper treatment, likely resulting in more severe functional impairment, multiple hospitalizations, self-inflicted injuries, and suicide attempts, since psychotropic medications are not particularly effective for improving self-efficacy and coping strategies, nor for correcting cognitive distortions, particularly in self-image, and pathological personality traits, all of which are critical aspects of BPD treatment.

Continue to: Several factors might...

Several factors might make clinicians reluctant to diagnose BPD, or bias them to diagnose BD more frequently. These include a lack of familiarity with the diagnostic criteria for BPD, the phenotypical resemblance between BP and BPD, or even concerns about the stigma and negative implications that are associated with a BPD diagnosis.32,37,38

Whereas BD is currently perceived as a condition with a strong biological basis, there are considerable misconceptions regarding BPD and its nature.4-6,22,26 As a consequence, individuals with BPD tend to be perceived as “difficult-to-treat,” “uncooperative,” or “attention-seeking.” These misconceptions may result in poor clinician-patient relationships, unmet clinical and psychiatric needs, and frustration for both clinicians and patients.37

Through advances in biological psychiatry, precision medicine may someday be a part of psychiatric practice. Biological “signatures” may eventually help clinicians in diagnosing and treating psychiatric disorders. Presently, however, rigorous history-taking and comprehensive clinical assessments are still the most powerful tools a clinician can use to accomplish these goals. Finally, destigmatizing psychiatric disorders and educating patients and clinicians are also critical to improving clinical outcomes and promoting mental health in a compassionate and empathetic fashion.

Bottom Line

Despite the phenotypical resemblance between bipolar disorder (BP) and borderline personality disorder (BPD), the 2 are independent conditions with distinct neurobiological and psychopathological underpinnings. Clinicians can use a rigorous assessment of pathological personality traits and characterization of symptoms, such as onset patterns, clinical course, and phenomenology, to properly distinguish between BP and BPD.

Related Resources

- Fiedorowicz JG, Black DW. Borderline, bipolar, or both? Frame your diagnosis on the patient history. Current Psychiatry. 2010; 9(1):21-24,29-32.

- Zimmerman M. Improving the recognition of borderline personality disorder. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(10):13-19.

- National Institute of Mental Health. Overview on bipolar disorder. www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/bipolar-disorder/index.shtml. Revised October 2018.

- National Institute of Mental Health. Overview on borderline personality disorder. www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/borderline-personality-disorder-fact-sheet/index.shtml.

Although evidence suggests that bipolar disorder (BD) and borderline personality disorder (BPD) are distinct entities, their differential diagnosis is often challenging as a result of considerable overlap of phenotypical features. Moreover, BD and BPD frequently co-occur, which makes it even more difficult to differentiate these 2 conditions. Strategies for improving diagnostic accuracy are critical to optimizing patients’ clinical outcomes and long-term prognosis. Misdiagnosing these 2 conditions can be particularly deleterious, and failure to recognize their co-occurrence can result in additional burden to typically complex and severe clinical presentations.

This article describes key aspects of the differential diagnosis between BD and BPD, emphasizing core features and major dissimilarities between these 2 conditions, and discusses the implications of misdiagnosis. The goal is to highlight the clinical and psychopathological aspects of BD and BPD to help clinicians properly distinguish these 2 disorders.

Psychopathological and sociodemographic correlates

Bipolar disorder is a chronic and severe mental illness that is classified based on clusters of symptoms—manic, hypomanic, and depressive.1 It is among the 10 leading causes of disability worldwide, with significant morbidity arising from acute affective episodes and subacute states.2 Data suggest the lifetime prevalence of BPD is 2.1%, and subthreshold forms may affect an additional 2.4% of the US population.3 The onset of symptoms typically occurs during late adolescence or early adulthood, and mood lability and cyclothymic temperament are the most common prodromal features.4

In contrast, personality disorders, such as BPD, are characteristically pervasive and maladaptive patterns of emotional responses that usually deviate from an individual’s stage of development and cultural background.1 These disorders tend to cause significant impairment, particularly in personal, occupational, and social domains. Environmental factors, such as early childhood trauma, seem to play an important role in the genesis of personality disorders, which may be particularly relevant in BPD, a disorder characterized by marked impulsivity and a pattern of instability in personal relationships, self-image, and affect.1,5,6 Similarly to BD, BPD is also chronic and highly disabling.

According to the National Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC), approximately 15% of US adults were found to have at least one type of personality disorder, and 6% met criteria for a cluster B personality disorder (antisocial, borderline, narcissistic, and histrionic).7 The lifetime prevalence of BPD is nearly 2%, with higher estimates observed in psychiatric settings.7,8

As a result of the phenotypical resemblance between BD and BPD (Figure), the differential diagnosis is often difficult. Recent studies suggest that co-occurrence of BD and BPD is common, with rates of comorbid BPD as high as 29% in BD I and 24% in BD II.8,9 On the other hand, nearly 20% of individuals with BPD seem to have comorbid BD.8,9 Several studies suggest that comorbid personality disorders represent a negative prognostic factor in the course of mood disorders, and the presence of BPD in patients with BD seems to be associated with more severe clinical presentations, greater treatment complexity, a higher number of depressive episodes, poor inter-episode functioning, and higher rates of other comorbidities, such as substance use disorders (SUDs).8-11 The effect of BD on the course of BPD is unclear and fairly unexplored, although it has been suggested that better control of mood symptoms may lead to more stable psychosocial functioning in BPD.9

Whether BD and BPD are part of the same spectrum is a matter for debate.12-14 Multidimensional approaches have been proposed to better characterize these disorders in at-risk populations, based on structured interviews, self-administered and clinician-rated clinical scales (Table 1), neuroimaging studies, biological markers, and machine-learning models.15,16 Compelling evidence suggests that BD and BPD have distinct underlying neurobiological and psychopathological mechanisms12,13; however, the differential diagnosis still relies on phenotypical features, since the search for biological markers has not yet identified specific biomarkers that can be used in clinical practice.

Continue to: Core features of BPD...

Core features of BPD, such as mood lability, impulsivity, and risk-taking behaviors, are also part of the diagnostic criteria for BD (Table 2).1 Similarly, depressive symptoms prevail in the course of BD.17,18 This adds complexity to the differential because “depressivity” is also part of the diagnostic criteria for BPD.1 Therefore, comprehensive psychiatric assessments and longitudinal observations are critical to diagnostic accuracy and treatment planning. Further characterization of symptoms, such as onset patterns, clinical course, phenomenology of symptoms (eg, timing, frequency, duration, triggers), and personality traits, will provide information to properly distinguish these 2 syndromes when, for example, it is unclear if the “mood swings” and impulsivity are part of a mood or a personality disorder (Table 3).

Clinical features: A closer look

Borderline personality disorder. Affect dysregulation, emotional instability, impoverished and unstable self-image, and chronic feelings of emptiness are core features of BPD.1,5,19 These characteristics, when combined with a fear of abandonment or rejection, a compromised ability to recognize the feelings and needs of others, and extremes of idealization-devaluation, tend to culminate in problematic and chaotic relationships.6,19 Individuals with BPD may become suspicious or paranoid under stressful situations. Under these circumstances, individuals with BPD may also experience depersonalization and other dissociative symptoms.6,20 The mood lability and emotional instability observed in patients with BPD usually are in response to environmental factors, and although generally intense and out of proportion, they tend to be ephemeral and short-lived, typically lasting a few hours.1,5 The anxiety and depressive symptoms reported by patients with BPD frequently are associated with feelings of “falling apart” or “losing control,” pessimism, shame, and low self-esteem. Coping strategies tend to be poorly developed and/or maladaptive, and individuals with BPD usually display a hostile and antagonistic demeanor and engage in suicidal or nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI) behaviors as means to alleviate overwhelming emotional distress. Impulsivity, disinhibition, poor tolerance to frustration, and risk-taking behaviors are also characteristic of BPD.1,5 As a result, BPD is usually associated with significant impairment in functioning, multiple hospitalizations, and high rates of comorbid mood disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), SUDs, and death by suicide.

Bipolar disorder. Conversely, the fluctuations in mood and affect observed in patients with BD are usually episodic rather than pervasive, and tend to last longer (typically days to weeks) compared with the transient mood shifts observed in patients with BPD.4,17,18 The impulsivity, psychomotor agitation, and increased goal-directed activity reported by patients with BD are usually seen in the context of an acute affective episode, and are far less common during periods of stability or euthymic affect.4,17,18 Grandiosity and inflated self-esteem—hallmarks of a manic or hypomanic state—seem to oppose the unstable self-image observed in BPD, although indecisiveness and low self-worth may be observed in individuals with BD during depressive episodes. Antidepressant-induced mania or hypomania, atypical depressive episodes, and disruptions in sleep and circadian rhythms may be predictors of BD.4,21 Furthermore, although psychosocial stressors may be associated with acute affective episodes in early stages of bipolar illness, over time minimal stressors are necessary to ignite new affective episodes.22,23 Although BD is associated with high rates of suicide, suicide attempts are usually seen in the context of an acute depressive episode, and NSSI behaviors are less common among patients with BD.24

Lastly, other biographical data, such as a history of early life trauma, comorbidity, and a family history of psychiatric illnesses, can be particularly helpful in establishing the differential diagnosis between BD and BPD.25 For instance, evidence suggests that the heritability of BD may be as high as 70%, which usually translates into an extensive family history of bipolar and related disorders.26 In addition, studies suggest a high co-occurrence of anxiety disorders, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and SUDs in patients with BD, whereas PTSD, SUDs, and eating disorders tend to be highly comorbid with BPD.27 Childhood adversity (ie, a history of physical, sexual, or emotional abuse, or neglect) seems to be pivotal in the genesis of BPD and may predispose these individuals to psychotic and dissociative symptoms, particularly those with a history of sexual abuse, while playing a more secondary role in BD.28-31

Implications of misdiagnosis

In the view of the limitations of the existing models, multidimensional approaches are necessary to improve diagnostic accuracy. Presently, the differential diagnosis of BD and BPD continues to rely on clinical findings and syndromic classifications. Misdiagnosing BD and BPD has adverse therapeutic and prognostic implications.32 For instance, while psychotropic medications and neuromodulatory therapies (eg, electroconvulsive therapy, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation) are considered first-line treatments for patients with BD, psychosocial interventions tend to be adjunctive treatments in BD.33 Conversely, although pharmacotherapy might be helpful for patients with BPD, psychosocial and behavioral interventions are the mainstay treatment for this disorder, with the strongest evidence supporting cognitive-behavioral therapy, dialectical behavioral therapy, mentalization-based therapy, and transference-focused therapy.34-36 Thus, misdiagnosing BD as BPD with comorbid depression may result in the use of antidepressants, which can be detrimental in BD. Antidepressant treatment of BD, particularly as monotherapy, has been associated with manic or hypomanic switch, mixed states, and frequent cycling.21 Moreover, delays in diagnosis and proper treatment of BD may result in protracted mood symptoms, prolonged affective episodes, higher rates of disability, functional impairment, and overall worse clinical outcomes.24 In addition, because behavioral and psychosocial interventions are usually adjunctive therapies rather than first-line interventions for patients with BD, misdiagnosing BPD as BD may ultimately prevent these individuals from receiving proper treatment, likely resulting in more severe functional impairment, multiple hospitalizations, self-inflicted injuries, and suicide attempts, since psychotropic medications are not particularly effective for improving self-efficacy and coping strategies, nor for correcting cognitive distortions, particularly in self-image, and pathological personality traits, all of which are critical aspects of BPD treatment.

Continue to: Several factors might...

Several factors might make clinicians reluctant to diagnose BPD, or bias them to diagnose BD more frequently. These include a lack of familiarity with the diagnostic criteria for BPD, the phenotypical resemblance between BP and BPD, or even concerns about the stigma and negative implications that are associated with a BPD diagnosis.32,37,38

Whereas BD is currently perceived as a condition with a strong biological basis, there are considerable misconceptions regarding BPD and its nature.4-6,22,26 As a consequence, individuals with BPD tend to be perceived as “difficult-to-treat,” “uncooperative,” or “attention-seeking.” These misconceptions may result in poor clinician-patient relationships, unmet clinical and psychiatric needs, and frustration for both clinicians and patients.37

Through advances in biological psychiatry, precision medicine may someday be a part of psychiatric practice. Biological “signatures” may eventually help clinicians in diagnosing and treating psychiatric disorders. Presently, however, rigorous history-taking and comprehensive clinical assessments are still the most powerful tools a clinician can use to accomplish these goals. Finally, destigmatizing psychiatric disorders and educating patients and clinicians are also critical to improving clinical outcomes and promoting mental health in a compassionate and empathetic fashion.

Bottom Line

Despite the phenotypical resemblance between bipolar disorder (BP) and borderline personality disorder (BPD), the 2 are independent conditions with distinct neurobiological and psychopathological underpinnings. Clinicians can use a rigorous assessment of pathological personality traits and characterization of symptoms, such as onset patterns, clinical course, and phenomenology, to properly distinguish between BP and BPD.

Related Resources

- Fiedorowicz JG, Black DW. Borderline, bipolar, or both? Frame your diagnosis on the patient history. Current Psychiatry. 2010; 9(1):21-24,29-32.

- Zimmerman M. Improving the recognition of borderline personality disorder. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(10):13-19.

- National Institute of Mental Health. Overview on bipolar disorder. www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/bipolar-disorder/index.shtml. Revised October 2018.

- National Institute of Mental Health. Overview on borderline personality disorder. www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/borderline-personality-disorder-fact-sheet/index.shtml.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Whiteford HA, Degenhardt L, Rehm J, et al. Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2013;382(9904):1575-1586.

3. Merikangas KR, Akiskal HS, Angst J, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of bipolar spectrum disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(5):543-552.

4. Malhi GS, Bargh DM, Coulston CM, et al. Predicting bipolar disorder on the basis of phenomenology: implications for prevention and early intervention. Bipolar Disord. 2014;16(5):455-470.

5. Skodol AE, Gunderson JG, Pfohl B, et al. The borderline diagnosis I: psychopathology. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;51(12):936-950.

6. Skodol AE, Siever LJ, Livesley WJ, et al. The borderline diagnosis II: biology, genetics, and clinical course. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;51(12):951-963.

7. Hasin DS, Grant BF. The National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) Waves 1 and 2: review and summary of findings. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2015;50(11):1609-1640.

8. McDermid J, Sareen J, El-Gabalawy R, et al. Co-morbidity of bipolar disorder and borderline personality disorder: findings from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Compr Psychiatry. 2015;58:18-28.

9. Gunderson JG, Weinberg I, Daversa MT, et al. Descriptive and longitudinal observations on the relationship of borderline personality disorder and bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(7):1173-1178.

10. Swartz HA, Pilkonis PA, Frank E, et al. Acute treatment outcomes in patients with bipolar I disorder and co-morbid borderline personality disorder receiving medication and psychotherapy. Bipolar Disord. 2005;7(2):192-197.

11. Riemann G, Weisscher N, Post RM, et al. The relationship between self-reported borderline personality features and prospective illness course in bipolar disorder. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2017;5(1):31.

12. de la Rosa I, Oquendo MA, García G, et al. Determining if borderline personality disorder and bipolar disorder are alternative expressions of the same disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2017;778(8):e994-e999. doi: 10.4088/JCP.16m11190.

13. di Giacomo E, Aspesi F, Fotiadou M, et al. Unblending borderline personality and bipolar disorders. J Psychiatr Res. 2017;91:90-97.

14. Parker G, Bayes A, McClure G, et al. Clinical status of comorbid bipolar disorder and borderline personality disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 2016;209(3):209-215.

15. Perez Arribas I, Goodwin GM, Geddes JR, et al. A signature-based machine learning model for distinguishing bipolar disorder and borderline personality disorder. Transl Psychiatry. 2018;8(1):274.

16. Insel T, Cuthbert B, Garvey M, et al. Research Domain Criteria (RDoC): toward a new classification framework for research on mental disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(7):748-751.

17. Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, et al. The long-term natural history of the weekly symptomatic status of bipolar I disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(6):530-537.

18. Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, et al. A prospective investigation of the natural history of the long-term weekly symptomatic status of bipolar II disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(3):261-269.

19. Oldham JM, Skodol AE, Bender DS. A current integrative perspective on personality disorders. American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc. 2005.

20. Herzog JI, Schmahl C. Adverse childhood experiences and the consequences on neurobiological, psychosocial, and somatic conditions across the lifespan. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:420.

21. Barbuti M, Pacchiarotti I, Vieta E, et al. Antidepressant-induced hypomania/mania in patients with major depression: evidence from the BRIDGE-II-MIX study. J Affect Disord. 2017;219:187-192.

22. Post RM. Mechanisms of illness progression in the recurrent affective disorders. Neurotox Res. 2010;18(3-4):256-271.

23. da Costa SC, Passos IC, Lowri C, et al. Refractory bipolar disorder and neuroprogression. Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacology Biol Psychiatry. 2016;70:103-110.

24. Crump C, Sundquist K, Winkleby MA, et al. Comorbidities and mortality in bipolar disorder: a Swedish national cohort study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(9):931-939.

25. Zimmerman M, Martinez JH, Morgan TA, et al. Distinguishing bipolar II depression from major depressive disorder with comorbid borderline personality disorder: demographic, clinical, and family history differences. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(9):880-886.

26. Hasler G, Drevets WC, Gould TD, et al. Toward constructing an endophenotype strategy for bipolar disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60(2):93-105.

27. Brieger P, Ehrt U, Marneros A. Frequency of comorbid personality disorders in bipolar and unipolar affective disorders. Compr Psychiatry. 2003;44(1):28-34.

28. Leverich GS, McElroy SL, Suppes T, et al. Early physical and sexual abuse associated with an adverse course of bipolar illness. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;51(4):288-297.

29. Leverich GS, Post RM. Course of bipolar illness after history of childhood trauma. Lancet. 2006;367(9516):1040-1042.

30. Golier JA, Yehuda R, Bierer LM, et al. The relationship of borderline personality disorder to posttraumatic stress disorder and traumatic events. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(11):2018-2024.

31. Nicol K, Pope M, Romaniuk L, et al. Childhood trauma, midbrain activation and psychotic symptoms in borderline personality disorder. Transl Psychiatry. 2015;5:e559. doi:10.1038/tp.2015.53.

32. Ruggero CJ, Zimmerman M, Chelminski I, et al. Borderline personality disorder and the misdiagnosis of bipolar disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 2010;44(6):405-408.

33. Geddes JR, Miklowitz DJ. Treatment of bipolar disorder. Lancet. 2013;381(9878):1672-1682.

34. McMain S, Korman LM, Dimeff L. Dialectical behavior therapy and the treatment of emotion dysregulation. J Clin Psychol. 2001;57(2):183-196.

35. Cristea IA, Gentili C, Cotet CD, et al. Efficacy of psychotherapies for borderline personality disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(4):319-328.

36. Linehan MM, Korslund KE, Harned MS, et al. Dialectical behavior therapy for high suicide risk in individuals with borderline personality disorder. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(75);475-482.

37. LeQuesne ER, Hersh RG. Disclosure of a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder. J Psychiatr Pract. 2004:10(3):170-176.

38. Young AH. Bipolar disorder: diagnostic conundrums and associated comorbidities. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(8):e26. doi:10.4088/jcp.7067br6c.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Whiteford HA, Degenhardt L, Rehm J, et al. Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2013;382(9904):1575-1586.

3. Merikangas KR, Akiskal HS, Angst J, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of bipolar spectrum disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(5):543-552.

4. Malhi GS, Bargh DM, Coulston CM, et al. Predicting bipolar disorder on the basis of phenomenology: implications for prevention and early intervention. Bipolar Disord. 2014;16(5):455-470.

5. Skodol AE, Gunderson JG, Pfohl B, et al. The borderline diagnosis I: psychopathology. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;51(12):936-950.

6. Skodol AE, Siever LJ, Livesley WJ, et al. The borderline diagnosis II: biology, genetics, and clinical course. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;51(12):951-963.

7. Hasin DS, Grant BF. The National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) Waves 1 and 2: review and summary of findings. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2015;50(11):1609-1640.

8. McDermid J, Sareen J, El-Gabalawy R, et al. Co-morbidity of bipolar disorder and borderline personality disorder: findings from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Compr Psychiatry. 2015;58:18-28.

9. Gunderson JG, Weinberg I, Daversa MT, et al. Descriptive and longitudinal observations on the relationship of borderline personality disorder and bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(7):1173-1178.

10. Swartz HA, Pilkonis PA, Frank E, et al. Acute treatment outcomes in patients with bipolar I disorder and co-morbid borderline personality disorder receiving medication and psychotherapy. Bipolar Disord. 2005;7(2):192-197.

11. Riemann G, Weisscher N, Post RM, et al. The relationship between self-reported borderline personality features and prospective illness course in bipolar disorder. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2017;5(1):31.

12. de la Rosa I, Oquendo MA, García G, et al. Determining if borderline personality disorder and bipolar disorder are alternative expressions of the same disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2017;778(8):e994-e999. doi: 10.4088/JCP.16m11190.

13. di Giacomo E, Aspesi F, Fotiadou M, et al. Unblending borderline personality and bipolar disorders. J Psychiatr Res. 2017;91:90-97.

14. Parker G, Bayes A, McClure G, et al. Clinical status of comorbid bipolar disorder and borderline personality disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 2016;209(3):209-215.

15. Perez Arribas I, Goodwin GM, Geddes JR, et al. A signature-based machine learning model for distinguishing bipolar disorder and borderline personality disorder. Transl Psychiatry. 2018;8(1):274.

16. Insel T, Cuthbert B, Garvey M, et al. Research Domain Criteria (RDoC): toward a new classification framework for research on mental disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(7):748-751.

17. Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, et al. The long-term natural history of the weekly symptomatic status of bipolar I disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(6):530-537.

18. Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, et al. A prospective investigation of the natural history of the long-term weekly symptomatic status of bipolar II disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(3):261-269.

19. Oldham JM, Skodol AE, Bender DS. A current integrative perspective on personality disorders. American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc. 2005.

20. Herzog JI, Schmahl C. Adverse childhood experiences and the consequences on neurobiological, psychosocial, and somatic conditions across the lifespan. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:420.

21. Barbuti M, Pacchiarotti I, Vieta E, et al. Antidepressant-induced hypomania/mania in patients with major depression: evidence from the BRIDGE-II-MIX study. J Affect Disord. 2017;219:187-192.

22. Post RM. Mechanisms of illness progression in the recurrent affective disorders. Neurotox Res. 2010;18(3-4):256-271.

23. da Costa SC, Passos IC, Lowri C, et al. Refractory bipolar disorder and neuroprogression. Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacology Biol Psychiatry. 2016;70:103-110.

24. Crump C, Sundquist K, Winkleby MA, et al. Comorbidities and mortality in bipolar disorder: a Swedish national cohort study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(9):931-939.

25. Zimmerman M, Martinez JH, Morgan TA, et al. Distinguishing bipolar II depression from major depressive disorder with comorbid borderline personality disorder: demographic, clinical, and family history differences. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(9):880-886.

26. Hasler G, Drevets WC, Gould TD, et al. Toward constructing an endophenotype strategy for bipolar disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60(2):93-105.

27. Brieger P, Ehrt U, Marneros A. Frequency of comorbid personality disorders in bipolar and unipolar affective disorders. Compr Psychiatry. 2003;44(1):28-34.

28. Leverich GS, McElroy SL, Suppes T, et al. Early physical and sexual abuse associated with an adverse course of bipolar illness. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;51(4):288-297.

29. Leverich GS, Post RM. Course of bipolar illness after history of childhood trauma. Lancet. 2006;367(9516):1040-1042.

30. Golier JA, Yehuda R, Bierer LM, et al. The relationship of borderline personality disorder to posttraumatic stress disorder and traumatic events. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(11):2018-2024.

31. Nicol K, Pope M, Romaniuk L, et al. Childhood trauma, midbrain activation and psychotic symptoms in borderline personality disorder. Transl Psychiatry. 2015;5:e559. doi:10.1038/tp.2015.53.

32. Ruggero CJ, Zimmerman M, Chelminski I, et al. Borderline personality disorder and the misdiagnosis of bipolar disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 2010;44(6):405-408.

33. Geddes JR, Miklowitz DJ. Treatment of bipolar disorder. Lancet. 2013;381(9878):1672-1682.

34. McMain S, Korman LM, Dimeff L. Dialectical behavior therapy and the treatment of emotion dysregulation. J Clin Psychol. 2001;57(2):183-196.

35. Cristea IA, Gentili C, Cotet CD, et al. Efficacy of psychotherapies for borderline personality disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(4):319-328.

36. Linehan MM, Korslund KE, Harned MS, et al. Dialectical behavior therapy for high suicide risk in individuals with borderline personality disorder. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(75);475-482.

37. LeQuesne ER, Hersh RG. Disclosure of a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder. J Psychiatr Pract. 2004:10(3):170-176.

38. Young AH. Bipolar disorder: diagnostic conundrums and associated comorbidities. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(8):e26. doi:10.4088/jcp.7067br6c.

Increased Parkinson’s disease risk seen with bipolar disorder

Patients with bipolar disorder may be at increased risk of Parkinson’s disease in later life, according to a systematic review and meta-analysis published in JAMA Neurology.

Patrícia R. Faustino, MD, from the faculty of medicine at the University of Lisboa (Portgual), and coauthors reviewed and analyzed seven articles – four cohort studies and three cross-sectional studies – that reported data on idiopathic Parkinson’s disease in patients with bipolar disorder, compared with those without. The meta-analysis found that individuals with a previous diagnosis of bipolar disorder had a 235% higher risk of being later diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease. Even after removing studies with a high risk of bias, the risk was still 3.21 times higher in those with bipolar disorder, compared with those without.

“The pathophysiological rationale between bipolar disorder and Parkinson’s disease might be explained by the dopamine dysregulation hypothesis, which states that the cyclical process of bipolar disorder in manic states leads to a down-regulation of dopamine receptor sensitivity (depression phase), which is later compensated by up-regulation (manic state),” the authors wrote. “Over time, this phenomenon may lead to an overall reduction of dopaminergic activity, the prototypical Parkinson’s disease state.”

Subgroup analysis revealed that subgroups with shorter follow-up periods – less than 9 years – had a greater increase in the risk of a later Parkinson’s disease diagnosis. The authors noted that this could represent misdiagnosis of parkinsonism – possibly drug induced – as Parkinson’s disease. The researchers also raised the possibility that the increased risk of Parkinson’s disease in patients with bipolar disorder could relate to long-term lithium use, rather than being a causal relationship. “However, treatment with lithium is foundational in bipolar disorder, and so to separate the causal effect from a potential confounder would be particularly difficult,” they wrote.

One of the studies included did explore the use of lithium, and found that lithium monotherapy was associated with a significant increase in the risk of being diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease or taking antiparkinsonism medication, compared with antidepressant therapy. However the authors commented that the diagnostic code may not differentiate Parkinson’s disease from other causes of parkinsonism.

Given their findings, the authors suggested that, if patients with bipolar disorder present with parkinsonism features, it may not necessarily be drug induced. In these patients, they recommended an investigation for Parkinson’s disease, perhaps using functional neuroimaging “as Parkinson’s disease classically presents with nigrostriatal degeneration while drug-induced parkinsonism does not.”

Two authors declared grants and personal fees from the pharmaceutical sector. No other conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Faustino PR et al. JAMA Neurol. 2019 Oct 14. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.3446.

Patients with bipolar disorder may be at increased risk of Parkinson’s disease in later life, according to a systematic review and meta-analysis published in JAMA Neurology.

Patrícia R. Faustino, MD, from the faculty of medicine at the University of Lisboa (Portgual), and coauthors reviewed and analyzed seven articles – four cohort studies and three cross-sectional studies – that reported data on idiopathic Parkinson’s disease in patients with bipolar disorder, compared with those without. The meta-analysis found that individuals with a previous diagnosis of bipolar disorder had a 235% higher risk of being later diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease. Even after removing studies with a high risk of bias, the risk was still 3.21 times higher in those with bipolar disorder, compared with those without.

“The pathophysiological rationale between bipolar disorder and Parkinson’s disease might be explained by the dopamine dysregulation hypothesis, which states that the cyclical process of bipolar disorder in manic states leads to a down-regulation of dopamine receptor sensitivity (depression phase), which is later compensated by up-regulation (manic state),” the authors wrote. “Over time, this phenomenon may lead to an overall reduction of dopaminergic activity, the prototypical Parkinson’s disease state.”

Subgroup analysis revealed that subgroups with shorter follow-up periods – less than 9 years – had a greater increase in the risk of a later Parkinson’s disease diagnosis. The authors noted that this could represent misdiagnosis of parkinsonism – possibly drug induced – as Parkinson’s disease. The researchers also raised the possibility that the increased risk of Parkinson’s disease in patients with bipolar disorder could relate to long-term lithium use, rather than being a causal relationship. “However, treatment with lithium is foundational in bipolar disorder, and so to separate the causal effect from a potential confounder would be particularly difficult,” they wrote.

One of the studies included did explore the use of lithium, and found that lithium monotherapy was associated with a significant increase in the risk of being diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease or taking antiparkinsonism medication, compared with antidepressant therapy. However the authors commented that the diagnostic code may not differentiate Parkinson’s disease from other causes of parkinsonism.

Given their findings, the authors suggested that, if patients with bipolar disorder present with parkinsonism features, it may not necessarily be drug induced. In these patients, they recommended an investigation for Parkinson’s disease, perhaps using functional neuroimaging “as Parkinson’s disease classically presents with nigrostriatal degeneration while drug-induced parkinsonism does not.”

Two authors declared grants and personal fees from the pharmaceutical sector. No other conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Faustino PR et al. JAMA Neurol. 2019 Oct 14. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.3446.

Patients with bipolar disorder may be at increased risk of Parkinson’s disease in later life, according to a systematic review and meta-analysis published in JAMA Neurology.

Patrícia R. Faustino, MD, from the faculty of medicine at the University of Lisboa (Portgual), and coauthors reviewed and analyzed seven articles – four cohort studies and three cross-sectional studies – that reported data on idiopathic Parkinson’s disease in patients with bipolar disorder, compared with those without. The meta-analysis found that individuals with a previous diagnosis of bipolar disorder had a 235% higher risk of being later diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease. Even after removing studies with a high risk of bias, the risk was still 3.21 times higher in those with bipolar disorder, compared with those without.

“The pathophysiological rationale between bipolar disorder and Parkinson’s disease might be explained by the dopamine dysregulation hypothesis, which states that the cyclical process of bipolar disorder in manic states leads to a down-regulation of dopamine receptor sensitivity (depression phase), which is later compensated by up-regulation (manic state),” the authors wrote. “Over time, this phenomenon may lead to an overall reduction of dopaminergic activity, the prototypical Parkinson’s disease state.”

Subgroup analysis revealed that subgroups with shorter follow-up periods – less than 9 years – had a greater increase in the risk of a later Parkinson’s disease diagnosis. The authors noted that this could represent misdiagnosis of parkinsonism – possibly drug induced – as Parkinson’s disease. The researchers also raised the possibility that the increased risk of Parkinson’s disease in patients with bipolar disorder could relate to long-term lithium use, rather than being a causal relationship. “However, treatment with lithium is foundational in bipolar disorder, and so to separate the causal effect from a potential confounder would be particularly difficult,” they wrote.

One of the studies included did explore the use of lithium, and found that lithium monotherapy was associated with a significant increase in the risk of being diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease or taking antiparkinsonism medication, compared with antidepressant therapy. However the authors commented that the diagnostic code may not differentiate Parkinson’s disease from other causes of parkinsonism.

Given their findings, the authors suggested that, if patients with bipolar disorder present with parkinsonism features, it may not necessarily be drug induced. In these patients, they recommended an investigation for Parkinson’s disease, perhaps using functional neuroimaging “as Parkinson’s disease classically presents with nigrostriatal degeneration while drug-induced parkinsonism does not.”

Two authors declared grants and personal fees from the pharmaceutical sector. No other conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Faustino PR et al. JAMA Neurol. 2019 Oct 14. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.3446.

FROM JAMA NEUROLOGY

#MomsNeedToKnow mental health awareness campaign set to launch

One goal is to use social media to encourage women to let go of stigma

Pregnancy-related mental health conditions are the most common complication of pregnancy, yet half of all women suffering will not be treated.

I wanted to address the stigma associated with these conditions as well as the rampant misinformation online. So, I reached out to Jen Schwartz, patient advocate and founder of Motherhood Understand, an online community for moms impacted by maternal mental health conditions. Together, we conceived the idea for the #MomsNeedToKnow maternal mental health awareness campaign, which will run from Oct. 14 to 25. This is an evidence-based campaign, complete with references and citations, that speaks to patients where they are at, i.e., social media.

With my clinical expertise and Jen’s reach, we felt like it was a natural partnership, as well as an innovative approach to empowering women to take control of their mental health during the perinatal period. We teamed up with Jamina Bone, an illustrator, and developed 2 weeks of Instagram posts, focused on the themes of lesser-known diagnoses, maternal mental health myths, and treatment options. This campaign is designed to help women understand risk factors for perinatal mood and anxiety disorders, as well as the signs of these conditions. It will cover lesser-known diagnoses like postpartum obsessive-compulsive disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder, and will address topics such as the impact of infertility on mental health and clarify the roles of different clinicians who can help.

Moreover, the campaign aims to address stigma and myths around psychiatric treatment during pregnancy – and also provides resources.

Dr. Lakshmin, a perinatal psychiatrist, is clinical assistant professor of psychiatry at George Washington University in Washington.

This article was updated 10/12/19.

One goal is to use social media to encourage women to let go of stigma

One goal is to use social media to encourage women to let go of stigma

Pregnancy-related mental health conditions are the most common complication of pregnancy, yet half of all women suffering will not be treated.

I wanted to address the stigma associated with these conditions as well as the rampant misinformation online. So, I reached out to Jen Schwartz, patient advocate and founder of Motherhood Understand, an online community for moms impacted by maternal mental health conditions. Together, we conceived the idea for the #MomsNeedToKnow maternal mental health awareness campaign, which will run from Oct. 14 to 25. This is an evidence-based campaign, complete with references and citations, that speaks to patients where they are at, i.e., social media.

With my clinical expertise and Jen’s reach, we felt like it was a natural partnership, as well as an innovative approach to empowering women to take control of their mental health during the perinatal period. We teamed up with Jamina Bone, an illustrator, and developed 2 weeks of Instagram posts, focused on the themes of lesser-known diagnoses, maternal mental health myths, and treatment options. This campaign is designed to help women understand risk factors for perinatal mood and anxiety disorders, as well as the signs of these conditions. It will cover lesser-known diagnoses like postpartum obsessive-compulsive disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder, and will address topics such as the impact of infertility on mental health and clarify the roles of different clinicians who can help.

Moreover, the campaign aims to address stigma and myths around psychiatric treatment during pregnancy – and also provides resources.

Dr. Lakshmin, a perinatal psychiatrist, is clinical assistant professor of psychiatry at George Washington University in Washington.

This article was updated 10/12/19.

Pregnancy-related mental health conditions are the most common complication of pregnancy, yet half of all women suffering will not be treated.

I wanted to address the stigma associated with these conditions as well as the rampant misinformation online. So, I reached out to Jen Schwartz, patient advocate and founder of Motherhood Understand, an online community for moms impacted by maternal mental health conditions. Together, we conceived the idea for the #MomsNeedToKnow maternal mental health awareness campaign, which will run from Oct. 14 to 25. This is an evidence-based campaign, complete with references and citations, that speaks to patients where they are at, i.e., social media.

With my clinical expertise and Jen’s reach, we felt like it was a natural partnership, as well as an innovative approach to empowering women to take control of their mental health during the perinatal period. We teamed up with Jamina Bone, an illustrator, and developed 2 weeks of Instagram posts, focused on the themes of lesser-known diagnoses, maternal mental health myths, and treatment options. This campaign is designed to help women understand risk factors for perinatal mood and anxiety disorders, as well as the signs of these conditions. It will cover lesser-known diagnoses like postpartum obsessive-compulsive disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder, and will address topics such as the impact of infertility on mental health and clarify the roles of different clinicians who can help.

Moreover, the campaign aims to address stigma and myths around psychiatric treatment during pregnancy – and also provides resources.

Dr. Lakshmin, a perinatal psychiatrist, is clinical assistant professor of psychiatry at George Washington University in Washington.

This article was updated 10/12/19.

Regional brain activation lower in bipolar disorder patients after multiple manic episodes

Patients with bipolar disorder who had undergone multiple manic episodes had significantly lower regional activation in the prefrontal‐striatal‐amygdala networks than single-episode patients, according to Logan Borgelt of the department of psychiatry and behavioral neuroscience at the University of Cincinnati and associates.

For the study, the investigators collected functional MRI data from 57 first‐episode manic patients (mean age, 19 years; mean Young Mania Rating Scale [YMRS] score, 26) and 50 multiepisode patients (mean age, 32 years; mean YMRS score, 21) who performed a continuous task with emotional distractions, as well as MR spectroscopy from 52 first-episode patients (mean age, 19 years; mean YMRS score, 26) and 54 multiepisode patients (mean age, 32 years; mean YMRS, 22). The study was published in Bipolar Disorders.

The investigation found that activation of the bilateral ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (P = .0122 for left; P = .0007 for right), anterior cingulate cortex (P less than .0001), orbitofrontal cortex (P = .0133), putamen (P = .0032), caudate (P = .0008), and amygdala (P = .0215) was significantly lower in multiepisode patients than in single-episode patients. Glutamate and N‐acetylaspartate concentration in the anterior cingulate cortex was also lower in multiepisode patients.

The age of multiepisode patients was, in general, not heavily associated with worse activation; only the right putamen (r = 0.30) and right thalamus (r = 0.30) reached a moderate effect size.

“Our findings are consistent with a hypothesized vicious cycle in which progressive atrophic changes in the prefrontal cortex are associated with functional decrements in affective networks, which in turn contribute to both further neuronal loss and clinical observations of accelerating symptomatic recurrence. ,” the investigators wrote.

Mr. Borgelt reported no conflicts. Three coauthors reported consulting with, receiving support and honoraria from, or serving on the speaker’s bureaus for numerous sources. The remaining coauthors did not report any conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Borgelt L et al. Bipolar Disord. 2019 Apr 26. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12782.