User login

What works best for genitourinary syndrome of menopause: vaginal estrogen, vaginal laser, or combined laser and estrogen therapy?

EXPERT COMMENTARY

GSM encompasses a constellation of symptoms involving the vulva, vagina, urethra, and bladder, and it can affect quality of life in more than half of women by 3 years past menopause.1,2 Local estrogen creams, tablets, and rings are considered the gold standard treatment for GSM.3 The rising cost of many of these pharmacologic treatments has created headlines and concerns over price gouging for drugs used to treat female sexual dysfunction.4 Recent alternatives to local estrogens include vaginal moisturizers and lubricants, vaginal dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) suppositories, oral ospemifene, and vaginal laser therapy.

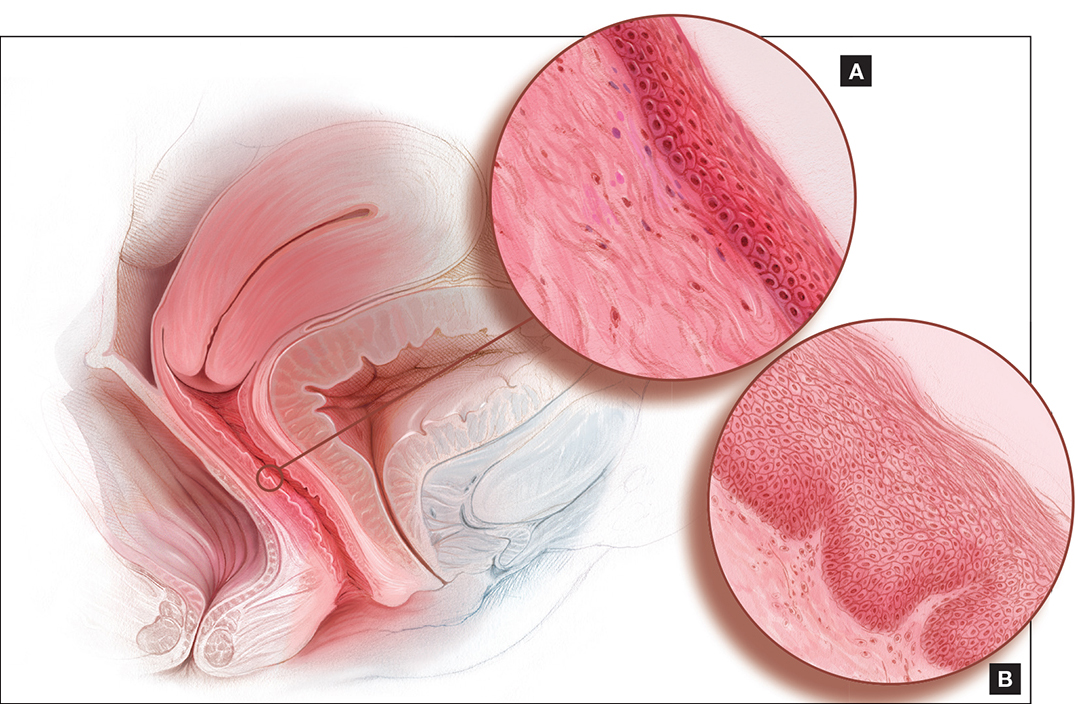

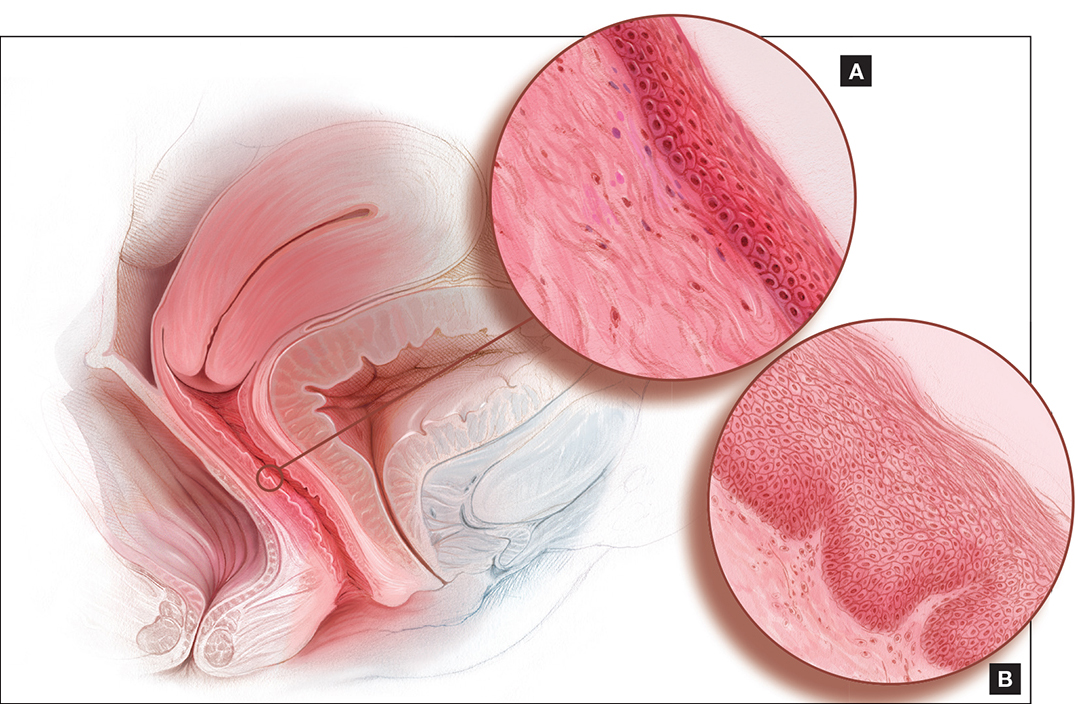

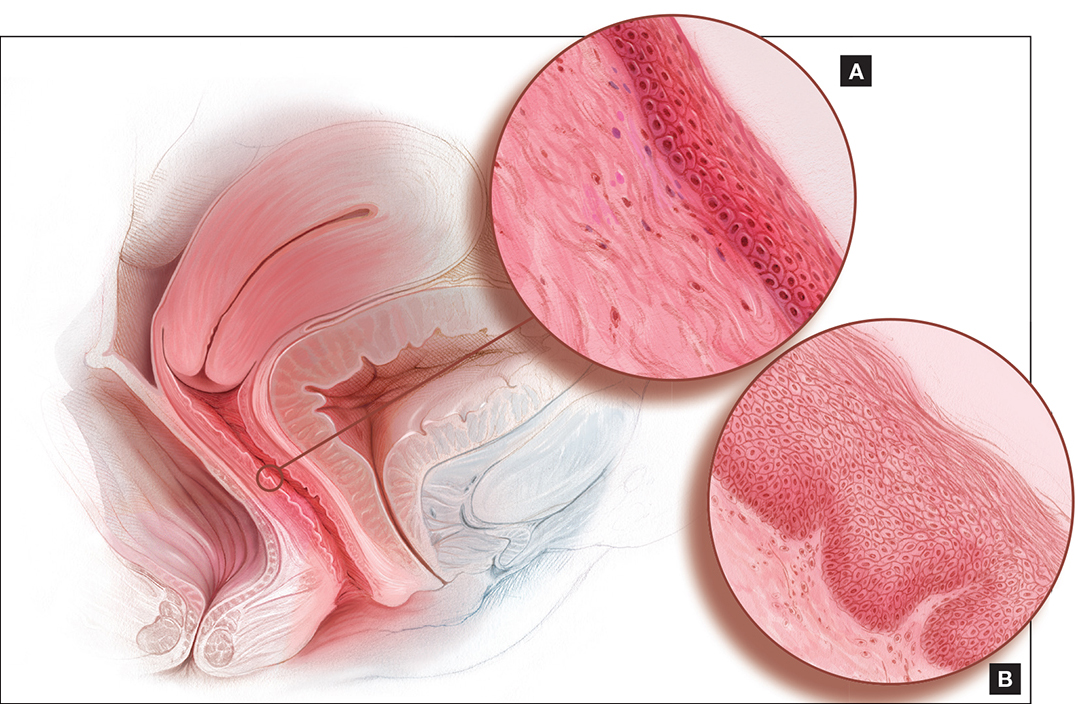

Laser treatment (with fractionated CO2, erbium, and hybrid lasers) activates heat shock proteins and tissue growth factors to stimulateneocollagenesis and neovascularization within the vaginal epithelium,but it is expensive and not covered by insurance because it is considered a cosmetic procedure.5Most evidence on laser therapy for GSM comes from prospective case series with small numbers and short-term follow-up with no comparison arms.6,7 A recent trial by Cruz and colleagues, however, is notable because it is one of the first published studies that compared vaginal laser with vaginal estrogen alone and with a combination laser plus estrogen arm. We need level 1 comparative data from studies such as this to help us counsel the millions of US women with GSM.

Details of the study

In this single-site randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial conducted in Brazil, postmenopausal women were assigned to 1 of 3 treatment groups (15 per group):

- CO2 laser (MonaLisa Touch, SmartXide 2 system; DEKA Laser; Florence, Italy): 2 treatments total, 1 month apart, plus placebo cream (laser arm)

- estriol cream (1 mg estriol 3 times per week for 20 weeks) plus sham laser (estriol arm)

- CO2 laser plus estriol cream 3 times per week (laser plus estriol combination arm).

The primary outcome included a change in visual analog scale (VAS) score for symptoms related to vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA), including dyspareunia, dryness, and burning (0–10 scale with 0 = no symptoms and 10 = most severe symptoms), and change in the objective Vaginal Health Index (VHI). Assessments were made at baseline and at 8 and 20 weeks. Participants were included if they were menopausal for at least 2 years and had at least 1 moderately bothersome VVA symptom (based on a VAS score of 4 or greater).

Secondary outcomes included the objective FSFI questionnaire evaluating desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, and pain. FSFI scores can range from 2 (severe dysfunction) to 36 (no dysfunction). A total FSFI score less than 26 was deemed equivalent to dysfunction. Cytologic smear evaluation using a vaginal maturation index was included in all 3 treatment arms. Sample size calculation of 45 patients (15 per arm) for this trial was based on a 3-point difference in the VHI.

The baseline characteristics for participants in each treatment arm were similar, except that participants in the vaginal estriol group were less symptomatic at baseline. This group had less burning at baseline based on the FSFI and less dyspareunia based on the VAS.

On July 30, 2018, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a safety warning against the use of energy-based devices for vaginal "rejuvenation"1 and sent warning letters to 7 companies--Alma Lasers; BTL Aesthetics; BTL Industries, Inc; Cynosure, Inc; InMode MD; Sciton, Inc; and Thermigen, Inc.2 The concern relates to marketing claims made on many of these companies' websites on the use of radiofrequency and laser technology for such specific conditions as vaginal laxity, vaginal dryness, urinary incontinence, and sexual function and response. These devices are neither cleared nor approved by the FDA for these specific indications; they are rather approved for general gynecologic conditions, such as the treatment of genital warts and precancerous conditions.

The FDA sent the safety warning related to energy-based vaginal therapies to patients and providers and have encouraged them to submit any adverse events to MedWatch, the FDA Safety Information and Adverse Event Reporting system.1 The "It has come to our attention letters" issued by the FDA to the above manufacturers request additional information and FDA clearance or approval numbers for claims made on their websites--specifically, referenced benefits of energy-based devices for vaginal, vulvar, and sexual health.2 This information is requested from manufacturers in writing by August 30, 2018 (30 days).

References

- FDA warns against use of energy-based devices to perform vaginal 'rejuvenation' or vaginal cosmetic procedures: FDA safety communication. US Food and Drug Administration website. https://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/Safety/AlertsandNotices/ucm615013.htm. Updated July 30, 2018. Accessed July 30, 2018.

- Letters to industry. US Food and Drug Administration website. https://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/ResourcesforYou/Industry/ucm111104.htm. Updated July 30, 2018. Accessed July 30, 2018.

Laser treatment improved dryness, burning, and dyspareunia but caused more pain

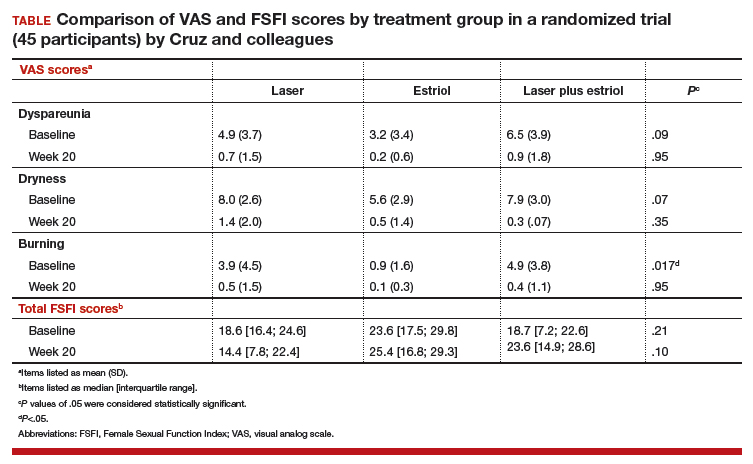

All 3 treatment groups showed statistically significant improvement in vaginal dryness at 20 weeks, but only the laser-alone arm and the laser plus estriol arms showed improvement in dyspareunia and burning. The total FSFI scores improved significantly only in the laser plus estriol arm (TABLE). No difference in the vaginal maturation index was noted between groups; however, improved numbers of parabasal cells were found in participants in the laser treatment arms.

While participants in the laser treatment arms (alone and in combination with estriol) showed significant improvement in the VAS domains of dyspareunia and burning compared with those treated with estriol alone, there was a contradictory finding of more pain in both laser arms at 20 weeks compared with the estriol-alone group, based on the FSFI. The FSFI is a validated, objective quality-of-life questionnaire, and the finding of more pain with laser treatment is a concern.

Exercise caution when interpreting these study findings. While this preliminary study showed that fractionated CO2 laser treatment had favorable outcomes for dyspareunia, dryness, and burning, the propensity for increased vaginal pain with this treatment is a concern. This study was not adequately powered to analyze multiple comparisons in postmenopausal women with GSM symptoms. There were significant baseline differences, with less bothersome burning and sexual complaints based on the FSFI and VAS, in the vaginal estriol arm. The finding of more pain in the laser treatment arms at 20 weeks compared with that in the vaginal estriol arm is of concern and warrants further investigation.

-- Cheryl B. Iglesia, MD

Study strengths and weaknesses

This study is one of the first of its kind to compare laser therapy alone and in combination with local estriol to vaginal estriol alone for the treatment of GSM. The trial’s strength is in its design as a double-blind, placebo-controlled block randomized trial, which adds to the prospective cohort trials that generally show favorable outcomes for fractionated laser for the treatment of GSM.

The study’s weaknesses include its small sample size, single trial site, and short-term follow-up. Findings from this trial should be considered preliminary and not generalizable. Other weaknesses are the 3 of 45 participants lost to follow-up and the significant baseline differences among the women, with lower bothersome baseline VAS scores in the estriol arm.

Furthermore, this study was not powered for multiple comparisons, and conclusions favoring laser therapy cannot be overinflated. Lasers such as CO2 target the chromophore water, and indiscriminate use in severely dry vaginal epithelium may cause more pain or scarring. Longer-term follow-up is needed.

More research also is needed to develop guidelines related to pre-laser treatment to achieve optimal vaginal pH and ideal vaginal maturation, including, for example, vaginal priming with estrogen, DHEA, or other moisturizers.

This study also suggests the use of vaginal laser therapy as a drug delivery mechanism for combination therapy. Many vaginal estrogen treatments are expensive (despite prescription drug coverage), and laser treatments are very expensive (and not covered by insurance), so research to optimize outcomes and minimize patient expense is needed.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Kingsberg SA, Wysocki S, Magnus L, Krychman ML. Vulvar and vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women: findings from the REVIVE (REal Women’s VIews of Treatment Options for Menopausal Vaginal ChangEs) survey. J Sex Med. 2013;10(7):1790–1799.

- Portman DJ, Gass ML; Vulvovaginal Atrophy Terminology Consensus Conference Panel. Genitourinary syndrome of menopause: new terminology for vulvovaginal atrophy from the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health and the North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2014;21(10):1063–1068.

- The NAMS 2017 Hormone Therapy Position Statement Advisory Panel. The 2017 hormone therapy position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2017;24(7):728–753.

- Thomas K. Prices keep rising for drugs treating painful sex in women. New York Times. June 3, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/06/03/health/vagina-womens-health-drug-prices.html. Accessed July 15, 2018.

- Tadir Y, Gaspar A, Lev-Sagie A, et al. Light and energy based therapeutics for genitourinary syndrome of meno-pause: consensus and controversies. Lasers Surg Med. 2017;49(2):137–159.

- Athanasiou S, Pitsouni E, Antonopoulou S, et al. The effect of microablative fractional CO2 laser on vaginal flora of postmenopausal women. Climacteric. 2016;19(5):512–518.

- Sokol ER, Karram MM. Use of a novel fractional CO2 laser for the treatment of genitourinary syndrome of menopause: 1-year outcomes. Menopause. 2017;24(7):810–814.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

GSM encompasses a constellation of symptoms involving the vulva, vagina, urethra, and bladder, and it can affect quality of life in more than half of women by 3 years past menopause.1,2 Local estrogen creams, tablets, and rings are considered the gold standard treatment for GSM.3 The rising cost of many of these pharmacologic treatments has created headlines and concerns over price gouging for drugs used to treat female sexual dysfunction.4 Recent alternatives to local estrogens include vaginal moisturizers and lubricants, vaginal dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) suppositories, oral ospemifene, and vaginal laser therapy.

Laser treatment (with fractionated CO2, erbium, and hybrid lasers) activates heat shock proteins and tissue growth factors to stimulateneocollagenesis and neovascularization within the vaginal epithelium,but it is expensive and not covered by insurance because it is considered a cosmetic procedure.5Most evidence on laser therapy for GSM comes from prospective case series with small numbers and short-term follow-up with no comparison arms.6,7 A recent trial by Cruz and colleagues, however, is notable because it is one of the first published studies that compared vaginal laser with vaginal estrogen alone and with a combination laser plus estrogen arm. We need level 1 comparative data from studies such as this to help us counsel the millions of US women with GSM.

Details of the study

In this single-site randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial conducted in Brazil, postmenopausal women were assigned to 1 of 3 treatment groups (15 per group):

- CO2 laser (MonaLisa Touch, SmartXide 2 system; DEKA Laser; Florence, Italy): 2 treatments total, 1 month apart, plus placebo cream (laser arm)

- estriol cream (1 mg estriol 3 times per week for 20 weeks) plus sham laser (estriol arm)

- CO2 laser plus estriol cream 3 times per week (laser plus estriol combination arm).

The primary outcome included a change in visual analog scale (VAS) score for symptoms related to vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA), including dyspareunia, dryness, and burning (0–10 scale with 0 = no symptoms and 10 = most severe symptoms), and change in the objective Vaginal Health Index (VHI). Assessments were made at baseline and at 8 and 20 weeks. Participants were included if they were menopausal for at least 2 years and had at least 1 moderately bothersome VVA symptom (based on a VAS score of 4 or greater).

Secondary outcomes included the objective FSFI questionnaire evaluating desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, and pain. FSFI scores can range from 2 (severe dysfunction) to 36 (no dysfunction). A total FSFI score less than 26 was deemed equivalent to dysfunction. Cytologic smear evaluation using a vaginal maturation index was included in all 3 treatment arms. Sample size calculation of 45 patients (15 per arm) for this trial was based on a 3-point difference in the VHI.

The baseline characteristics for participants in each treatment arm were similar, except that participants in the vaginal estriol group were less symptomatic at baseline. This group had less burning at baseline based on the FSFI and less dyspareunia based on the VAS.

On July 30, 2018, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a safety warning against the use of energy-based devices for vaginal "rejuvenation"1 and sent warning letters to 7 companies--Alma Lasers; BTL Aesthetics; BTL Industries, Inc; Cynosure, Inc; InMode MD; Sciton, Inc; and Thermigen, Inc.2 The concern relates to marketing claims made on many of these companies' websites on the use of radiofrequency and laser technology for such specific conditions as vaginal laxity, vaginal dryness, urinary incontinence, and sexual function and response. These devices are neither cleared nor approved by the FDA for these specific indications; they are rather approved for general gynecologic conditions, such as the treatment of genital warts and precancerous conditions.

The FDA sent the safety warning related to energy-based vaginal therapies to patients and providers and have encouraged them to submit any adverse events to MedWatch, the FDA Safety Information and Adverse Event Reporting system.1 The "It has come to our attention letters" issued by the FDA to the above manufacturers request additional information and FDA clearance or approval numbers for claims made on their websites--specifically, referenced benefits of energy-based devices for vaginal, vulvar, and sexual health.2 This information is requested from manufacturers in writing by August 30, 2018 (30 days).

References

- FDA warns against use of energy-based devices to perform vaginal 'rejuvenation' or vaginal cosmetic procedures: FDA safety communication. US Food and Drug Administration website. https://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/Safety/AlertsandNotices/ucm615013.htm. Updated July 30, 2018. Accessed July 30, 2018.

- Letters to industry. US Food and Drug Administration website. https://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/ResourcesforYou/Industry/ucm111104.htm. Updated July 30, 2018. Accessed July 30, 2018.

Laser treatment improved dryness, burning, and dyspareunia but caused more pain

All 3 treatment groups showed statistically significant improvement in vaginal dryness at 20 weeks, but only the laser-alone arm and the laser plus estriol arms showed improvement in dyspareunia and burning. The total FSFI scores improved significantly only in the laser plus estriol arm (TABLE). No difference in the vaginal maturation index was noted between groups; however, improved numbers of parabasal cells were found in participants in the laser treatment arms.

While participants in the laser treatment arms (alone and in combination with estriol) showed significant improvement in the VAS domains of dyspareunia and burning compared with those treated with estriol alone, there was a contradictory finding of more pain in both laser arms at 20 weeks compared with the estriol-alone group, based on the FSFI. The FSFI is a validated, objective quality-of-life questionnaire, and the finding of more pain with laser treatment is a concern.

Exercise caution when interpreting these study findings. While this preliminary study showed that fractionated CO2 laser treatment had favorable outcomes for dyspareunia, dryness, and burning, the propensity for increased vaginal pain with this treatment is a concern. This study was not adequately powered to analyze multiple comparisons in postmenopausal women with GSM symptoms. There were significant baseline differences, with less bothersome burning and sexual complaints based on the FSFI and VAS, in the vaginal estriol arm. The finding of more pain in the laser treatment arms at 20 weeks compared with that in the vaginal estriol arm is of concern and warrants further investigation.

-- Cheryl B. Iglesia, MD

Study strengths and weaknesses

This study is one of the first of its kind to compare laser therapy alone and in combination with local estriol to vaginal estriol alone for the treatment of GSM. The trial’s strength is in its design as a double-blind, placebo-controlled block randomized trial, which adds to the prospective cohort trials that generally show favorable outcomes for fractionated laser for the treatment of GSM.

The study’s weaknesses include its small sample size, single trial site, and short-term follow-up. Findings from this trial should be considered preliminary and not generalizable. Other weaknesses are the 3 of 45 participants lost to follow-up and the significant baseline differences among the women, with lower bothersome baseline VAS scores in the estriol arm.

Furthermore, this study was not powered for multiple comparisons, and conclusions favoring laser therapy cannot be overinflated. Lasers such as CO2 target the chromophore water, and indiscriminate use in severely dry vaginal epithelium may cause more pain or scarring. Longer-term follow-up is needed.

More research also is needed to develop guidelines related to pre-laser treatment to achieve optimal vaginal pH and ideal vaginal maturation, including, for example, vaginal priming with estrogen, DHEA, or other moisturizers.

This study also suggests the use of vaginal laser therapy as a drug delivery mechanism for combination therapy. Many vaginal estrogen treatments are expensive (despite prescription drug coverage), and laser treatments are very expensive (and not covered by insurance), so research to optimize outcomes and minimize patient expense is needed.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

GSM encompasses a constellation of symptoms involving the vulva, vagina, urethra, and bladder, and it can affect quality of life in more than half of women by 3 years past menopause.1,2 Local estrogen creams, tablets, and rings are considered the gold standard treatment for GSM.3 The rising cost of many of these pharmacologic treatments has created headlines and concerns over price gouging for drugs used to treat female sexual dysfunction.4 Recent alternatives to local estrogens include vaginal moisturizers and lubricants, vaginal dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) suppositories, oral ospemifene, and vaginal laser therapy.

Laser treatment (with fractionated CO2, erbium, and hybrid lasers) activates heat shock proteins and tissue growth factors to stimulateneocollagenesis and neovascularization within the vaginal epithelium,but it is expensive and not covered by insurance because it is considered a cosmetic procedure.5Most evidence on laser therapy for GSM comes from prospective case series with small numbers and short-term follow-up with no comparison arms.6,7 A recent trial by Cruz and colleagues, however, is notable because it is one of the first published studies that compared vaginal laser with vaginal estrogen alone and with a combination laser plus estrogen arm. We need level 1 comparative data from studies such as this to help us counsel the millions of US women with GSM.

Details of the study

In this single-site randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial conducted in Brazil, postmenopausal women were assigned to 1 of 3 treatment groups (15 per group):

- CO2 laser (MonaLisa Touch, SmartXide 2 system; DEKA Laser; Florence, Italy): 2 treatments total, 1 month apart, plus placebo cream (laser arm)

- estriol cream (1 mg estriol 3 times per week for 20 weeks) plus sham laser (estriol arm)

- CO2 laser plus estriol cream 3 times per week (laser plus estriol combination arm).

The primary outcome included a change in visual analog scale (VAS) score for symptoms related to vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA), including dyspareunia, dryness, and burning (0–10 scale with 0 = no symptoms and 10 = most severe symptoms), and change in the objective Vaginal Health Index (VHI). Assessments were made at baseline and at 8 and 20 weeks. Participants were included if they were menopausal for at least 2 years and had at least 1 moderately bothersome VVA symptom (based on a VAS score of 4 or greater).

Secondary outcomes included the objective FSFI questionnaire evaluating desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, and pain. FSFI scores can range from 2 (severe dysfunction) to 36 (no dysfunction). A total FSFI score less than 26 was deemed equivalent to dysfunction. Cytologic smear evaluation using a vaginal maturation index was included in all 3 treatment arms. Sample size calculation of 45 patients (15 per arm) for this trial was based on a 3-point difference in the VHI.

The baseline characteristics for participants in each treatment arm were similar, except that participants in the vaginal estriol group were less symptomatic at baseline. This group had less burning at baseline based on the FSFI and less dyspareunia based on the VAS.

On July 30, 2018, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a safety warning against the use of energy-based devices for vaginal "rejuvenation"1 and sent warning letters to 7 companies--Alma Lasers; BTL Aesthetics; BTL Industries, Inc; Cynosure, Inc; InMode MD; Sciton, Inc; and Thermigen, Inc.2 The concern relates to marketing claims made on many of these companies' websites on the use of radiofrequency and laser technology for such specific conditions as vaginal laxity, vaginal dryness, urinary incontinence, and sexual function and response. These devices are neither cleared nor approved by the FDA for these specific indications; they are rather approved for general gynecologic conditions, such as the treatment of genital warts and precancerous conditions.

The FDA sent the safety warning related to energy-based vaginal therapies to patients and providers and have encouraged them to submit any adverse events to MedWatch, the FDA Safety Information and Adverse Event Reporting system.1 The "It has come to our attention letters" issued by the FDA to the above manufacturers request additional information and FDA clearance or approval numbers for claims made on their websites--specifically, referenced benefits of energy-based devices for vaginal, vulvar, and sexual health.2 This information is requested from manufacturers in writing by August 30, 2018 (30 days).

References

- FDA warns against use of energy-based devices to perform vaginal 'rejuvenation' or vaginal cosmetic procedures: FDA safety communication. US Food and Drug Administration website. https://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/Safety/AlertsandNotices/ucm615013.htm. Updated July 30, 2018. Accessed July 30, 2018.

- Letters to industry. US Food and Drug Administration website. https://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/ResourcesforYou/Industry/ucm111104.htm. Updated July 30, 2018. Accessed July 30, 2018.

Laser treatment improved dryness, burning, and dyspareunia but caused more pain

All 3 treatment groups showed statistically significant improvement in vaginal dryness at 20 weeks, but only the laser-alone arm and the laser plus estriol arms showed improvement in dyspareunia and burning. The total FSFI scores improved significantly only in the laser plus estriol arm (TABLE). No difference in the vaginal maturation index was noted between groups; however, improved numbers of parabasal cells were found in participants in the laser treatment arms.

While participants in the laser treatment arms (alone and in combination with estriol) showed significant improvement in the VAS domains of dyspareunia and burning compared with those treated with estriol alone, there was a contradictory finding of more pain in both laser arms at 20 weeks compared with the estriol-alone group, based on the FSFI. The FSFI is a validated, objective quality-of-life questionnaire, and the finding of more pain with laser treatment is a concern.

Exercise caution when interpreting these study findings. While this preliminary study showed that fractionated CO2 laser treatment had favorable outcomes for dyspareunia, dryness, and burning, the propensity for increased vaginal pain with this treatment is a concern. This study was not adequately powered to analyze multiple comparisons in postmenopausal women with GSM symptoms. There were significant baseline differences, with less bothersome burning and sexual complaints based on the FSFI and VAS, in the vaginal estriol arm. The finding of more pain in the laser treatment arms at 20 weeks compared with that in the vaginal estriol arm is of concern and warrants further investigation.

-- Cheryl B. Iglesia, MD

Study strengths and weaknesses

This study is one of the first of its kind to compare laser therapy alone and in combination with local estriol to vaginal estriol alone for the treatment of GSM. The trial’s strength is in its design as a double-blind, placebo-controlled block randomized trial, which adds to the prospective cohort trials that generally show favorable outcomes for fractionated laser for the treatment of GSM.

The study’s weaknesses include its small sample size, single trial site, and short-term follow-up. Findings from this trial should be considered preliminary and not generalizable. Other weaknesses are the 3 of 45 participants lost to follow-up and the significant baseline differences among the women, with lower bothersome baseline VAS scores in the estriol arm.

Furthermore, this study was not powered for multiple comparisons, and conclusions favoring laser therapy cannot be overinflated. Lasers such as CO2 target the chromophore water, and indiscriminate use in severely dry vaginal epithelium may cause more pain or scarring. Longer-term follow-up is needed.

More research also is needed to develop guidelines related to pre-laser treatment to achieve optimal vaginal pH and ideal vaginal maturation, including, for example, vaginal priming with estrogen, DHEA, or other moisturizers.

This study also suggests the use of vaginal laser therapy as a drug delivery mechanism for combination therapy. Many vaginal estrogen treatments are expensive (despite prescription drug coverage), and laser treatments are very expensive (and not covered by insurance), so research to optimize outcomes and minimize patient expense is needed.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Kingsberg SA, Wysocki S, Magnus L, Krychman ML. Vulvar and vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women: findings from the REVIVE (REal Women’s VIews of Treatment Options for Menopausal Vaginal ChangEs) survey. J Sex Med. 2013;10(7):1790–1799.

- Portman DJ, Gass ML; Vulvovaginal Atrophy Terminology Consensus Conference Panel. Genitourinary syndrome of menopause: new terminology for vulvovaginal atrophy from the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health and the North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2014;21(10):1063–1068.

- The NAMS 2017 Hormone Therapy Position Statement Advisory Panel. The 2017 hormone therapy position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2017;24(7):728–753.

- Thomas K. Prices keep rising for drugs treating painful sex in women. New York Times. June 3, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/06/03/health/vagina-womens-health-drug-prices.html. Accessed July 15, 2018.

- Tadir Y, Gaspar A, Lev-Sagie A, et al. Light and energy based therapeutics for genitourinary syndrome of meno-pause: consensus and controversies. Lasers Surg Med. 2017;49(2):137–159.

- Athanasiou S, Pitsouni E, Antonopoulou S, et al. The effect of microablative fractional CO2 laser on vaginal flora of postmenopausal women. Climacteric. 2016;19(5):512–518.

- Sokol ER, Karram MM. Use of a novel fractional CO2 laser for the treatment of genitourinary syndrome of menopause: 1-year outcomes. Menopause. 2017;24(7):810–814.

- Kingsberg SA, Wysocki S, Magnus L, Krychman ML. Vulvar and vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women: findings from the REVIVE (REal Women’s VIews of Treatment Options for Menopausal Vaginal ChangEs) survey. J Sex Med. 2013;10(7):1790–1799.

- Portman DJ, Gass ML; Vulvovaginal Atrophy Terminology Consensus Conference Panel. Genitourinary syndrome of menopause: new terminology for vulvovaginal atrophy from the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health and the North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2014;21(10):1063–1068.

- The NAMS 2017 Hormone Therapy Position Statement Advisory Panel. The 2017 hormone therapy position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2017;24(7):728–753.

- Thomas K. Prices keep rising for drugs treating painful sex in women. New York Times. June 3, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/06/03/health/vagina-womens-health-drug-prices.html. Accessed July 15, 2018.

- Tadir Y, Gaspar A, Lev-Sagie A, et al. Light and energy based therapeutics for genitourinary syndrome of meno-pause: consensus and controversies. Lasers Surg Med. 2017;49(2):137–159.

- Athanasiou S, Pitsouni E, Antonopoulou S, et al. The effect of microablative fractional CO2 laser on vaginal flora of postmenopausal women. Climacteric. 2016;19(5):512–518.

- Sokol ER, Karram MM. Use of a novel fractional CO2 laser for the treatment of genitourinary syndrome of menopause: 1-year outcomes. Menopause. 2017;24(7):810–814.

A multimodal treatment for vestibulodynia: TENS plus diazepam

and with placebo in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial.

In the TENS/diazepam and TENS/placebo groups, participants reported significant improvements from baseline in pain and sexual functioning by questionnaire and visual analog scale. They also improved in measurements of pelvic floor muscle tone and vestibular nerve fiber current perception threshold.

The study had two groups of 21 women each, all aged 18 years or older and diagnosed (by physical exam) with moderate or severe pelvic floor hypertonic dysfunction. The diazepam was a tablet inserted vaginally daily before bed.

The TENS therapy was also self-administered (after six or seven supervised trial sessions), a recommended three times per week. The device is a 20-mm diameter plastic vaginal probe with gold metallic transversal rings as electrodes, inserted 20 mm, with 30 minutes of electrical stimulation increased slowly until sensation “reached a level described as the maximum tolerable without experiencing pain.” Vulvar pain was assessed on a on a 10-cm visual analog scale and dyspareunia on the Marinoff dyspareunia scale.

At the primary endpoint, the mean change from baseline to 60 days, the diazepam combination improved from 7.5 on the visual scale to 4.7, while the placebo combination improved from 7.2 to 4.3 (P not significant between the groups). Marinoff dyspareunia scores, however, improved from 2.5 to 1.6 and from 2.0 to 1.3, respectively (P less than .01).

Though “very few statistically significant differences in outcomes between the two groups were observed ... our results indicate that diazepam is able to positively change the functions of the pelvic floor muscle often highlighted” in women with vestibulodynia, reported Filippo Murina, MD, of the University of Milan and his coauthors. This conclusion followed from the Marinoff scores and from vaginal surface electromyography. In the latter measure, the diazepam group showed a significantly greater ability to relax the pelvic floor muscle after contraction (3.8 vs. 2.4 microvolts; P = .01), compared with the placebo group.

“We also observed that TENS itself is essential in reducing vulvar pain and the action of diazepam is useful but not decisive. ... It is possible that vaginal diazepam alone is insufficient to resolve the symptoms related to pelvic floor muscle dysfunction, while vaginal diazepam and TENS together provide a synergistic benefit in vestibulodynia patients,” wrote Dr. Murina and his coauthors.

This study was supported by the Associazione Italiana Vulvodinia. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Murina F et al. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2018 Jun;228:148-53.

and with placebo in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial.

In the TENS/diazepam and TENS/placebo groups, participants reported significant improvements from baseline in pain and sexual functioning by questionnaire and visual analog scale. They also improved in measurements of pelvic floor muscle tone and vestibular nerve fiber current perception threshold.

The study had two groups of 21 women each, all aged 18 years or older and diagnosed (by physical exam) with moderate or severe pelvic floor hypertonic dysfunction. The diazepam was a tablet inserted vaginally daily before bed.

The TENS therapy was also self-administered (after six or seven supervised trial sessions), a recommended three times per week. The device is a 20-mm diameter plastic vaginal probe with gold metallic transversal rings as electrodes, inserted 20 mm, with 30 minutes of electrical stimulation increased slowly until sensation “reached a level described as the maximum tolerable without experiencing pain.” Vulvar pain was assessed on a on a 10-cm visual analog scale and dyspareunia on the Marinoff dyspareunia scale.

At the primary endpoint, the mean change from baseline to 60 days, the diazepam combination improved from 7.5 on the visual scale to 4.7, while the placebo combination improved from 7.2 to 4.3 (P not significant between the groups). Marinoff dyspareunia scores, however, improved from 2.5 to 1.6 and from 2.0 to 1.3, respectively (P less than .01).

Though “very few statistically significant differences in outcomes between the two groups were observed ... our results indicate that diazepam is able to positively change the functions of the pelvic floor muscle often highlighted” in women with vestibulodynia, reported Filippo Murina, MD, of the University of Milan and his coauthors. This conclusion followed from the Marinoff scores and from vaginal surface electromyography. In the latter measure, the diazepam group showed a significantly greater ability to relax the pelvic floor muscle after contraction (3.8 vs. 2.4 microvolts; P = .01), compared with the placebo group.

“We also observed that TENS itself is essential in reducing vulvar pain and the action of diazepam is useful but not decisive. ... It is possible that vaginal diazepam alone is insufficient to resolve the symptoms related to pelvic floor muscle dysfunction, while vaginal diazepam and TENS together provide a synergistic benefit in vestibulodynia patients,” wrote Dr. Murina and his coauthors.

This study was supported by the Associazione Italiana Vulvodinia. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Murina F et al. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2018 Jun;228:148-53.

and with placebo in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial.

In the TENS/diazepam and TENS/placebo groups, participants reported significant improvements from baseline in pain and sexual functioning by questionnaire and visual analog scale. They also improved in measurements of pelvic floor muscle tone and vestibular nerve fiber current perception threshold.

The study had two groups of 21 women each, all aged 18 years or older and diagnosed (by physical exam) with moderate or severe pelvic floor hypertonic dysfunction. The diazepam was a tablet inserted vaginally daily before bed.

The TENS therapy was also self-administered (after six or seven supervised trial sessions), a recommended three times per week. The device is a 20-mm diameter plastic vaginal probe with gold metallic transversal rings as electrodes, inserted 20 mm, with 30 minutes of electrical stimulation increased slowly until sensation “reached a level described as the maximum tolerable without experiencing pain.” Vulvar pain was assessed on a on a 10-cm visual analog scale and dyspareunia on the Marinoff dyspareunia scale.

At the primary endpoint, the mean change from baseline to 60 days, the diazepam combination improved from 7.5 on the visual scale to 4.7, while the placebo combination improved from 7.2 to 4.3 (P not significant between the groups). Marinoff dyspareunia scores, however, improved from 2.5 to 1.6 and from 2.0 to 1.3, respectively (P less than .01).

Though “very few statistically significant differences in outcomes between the two groups were observed ... our results indicate that diazepam is able to positively change the functions of the pelvic floor muscle often highlighted” in women with vestibulodynia, reported Filippo Murina, MD, of the University of Milan and his coauthors. This conclusion followed from the Marinoff scores and from vaginal surface electromyography. In the latter measure, the diazepam group showed a significantly greater ability to relax the pelvic floor muscle after contraction (3.8 vs. 2.4 microvolts; P = .01), compared with the placebo group.

“We also observed that TENS itself is essential in reducing vulvar pain and the action of diazepam is useful but not decisive. ... It is possible that vaginal diazepam alone is insufficient to resolve the symptoms related to pelvic floor muscle dysfunction, while vaginal diazepam and TENS together provide a synergistic benefit in vestibulodynia patients,” wrote Dr. Murina and his coauthors.

This study was supported by the Associazione Italiana Vulvodinia. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Murina F et al. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2018 Jun;228:148-53.

FROM THE EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY AND REPRODUCTIVE BIOLOGY

2018 Update on menopause

Our knowledge regarding the benefits and risks of systemic menopausal hormone therapy (HT) has continued to evolve since the 2002 publication of the initial findings of the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI). In late 2017, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) issued its recommendation against the use of menopausal HT for the prevention of chronic conditions. In this Menopause Update, Dr. JoAnn Manson, Dr. JoAnn Pinkerton, and I detail why we do not support the Task Force’s recommendation. In a sidebar discussion, Dr. Manson also reviews the results of 2 WHI HT trials, published in September 2017, that analyzed mortality in trial participants over an 18-year follow-up.

In addition, I summarize an observational study that assessed the association of HT and Alzheimer disease (AD) as well as a clinical trial that compared the impact of oral versus transdermal estrogen on sexuality in recently menopausal women.

What's the impact of long-term use of systemic HT on Alzheimer disease risk?

Imtiaz B, Tuppurainen M, Rikkonen T, et al. Postmenopausal hormone therapy and Alzheimer disease: a prospective cohort study. Neurology. 2017;88(11):1062-1068.

Data from the WHI HT randomized trials have clarified that initiation of oral HT among women aged 65 and older increases the risk of cognitive decline. By contrast, an analysis of younger WHI participants found that oral HT had no impact on cognitive function. Recently, Imtiaz and colleagues conducted a prospective cohort study of postmenopausal HT and AD in women residing in a Finnish county, with 25 years of follow-up. A diagnosis of AD was based on administrative health records and use of medications prescribed specifically to treat dementia. Use of systemic HT was identified via self-report. Overall, among more than 8,000 women followed, 227 cases of AD (mean age, 72 years) were identified.

In an analysis that controlled for factors including age, body mass index, alcohol use, smoking, physical activity, occupation status, and parity, up to 5 years of HT use was not associated with a risk of being diagnosed with AD. Five to 10 years of HT use was associated with a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.89, an 11% risk reduction that did not achieve statistical significance. By contrast, more than 10 years' use of systemic HT was associated with an HR of 0.53, a statistically significant 47% reduction in risk of AD.1

Other studies found conflicting results

Three large randomized trials found that HT initiated early in menopause and continued for less than 7 years had no impact on cognitive function.2-4 The Cache County (Utah) long-term prospective cohort study, however, found that HT started early in menopause and continued for 10 years or longer was associated with a significant reduction in risk of AD.5

Of note are results from the 2017 report of 18-year cumulative mortality among WHI participants (see the box on page 30). In that study, mortality from AD and other dementia was lower among participants who were randomly assigned to treatment with estrogen alone versus placebo (HR, 0.74; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.59-0.94). With estrogen-progestin therapy, the HR was 0.93 (95% CI, 0.77-1.11), and the pooled HR for the 2 trials was 0.85 (95% CI, 0.74-0.98).6

NAMS guidance

The North American Menopause Society (NAMS) HT position statement recommends that prevention of dementia should not be considered an indication for HT use since definitive data are not available.7 The statement indicates also that estrogen therapy may have positive cognitive benefits when initiated immediately after early surgical menopause and taken until the average age of menopause to prevent health risks seen with early loss of hormones.

Definitive data from long-term randomized clinical trials are not likely to become available. Observational trials continue to have methodologic issues, such as "healthy user bias," but the studies are reassuring that initiating HT close to menopause does not increase the risk of dementia. The long-term Finnish study by Imtiaz and colleagues and the Cache County study provide tentative observational data support for a "critical window" hypothesis, leaving open the possibility that initiating systemic HT soon after menopause onset and continuing it long term may reduce the risk of AD. Discussion is needed on individual patient characteristics, potential benefits and risks, and ongoing assessment over time.

Read Dr. Manson’s discussion of 18 years of follow-up data on menopause.

JoAnn E. Manson, MD, DrPH, NCMP

A new analysis from the Women's Health Initiative (WHI) randomized trials examined all-cause and cause-specific mortality during the intervention and postintervention follow-up periods.1 We followed more than 27,000 postmenopausal women aged 50 to 79 (mean age, 63) who were recruited to 2 randomized WHI trials of HT between 1993 and 1998. The trials continued until 2002 for the estrogen-progestin trial and to 2004 for the estrogen-alone trial. The trials ran for 5 to 7 years' duration, with post-stopping follow-up for an additional 10 to 12 years (total cumulative follow-up of 18 years).

The participants were randomly assigned to receive active treatment or placebo. The interventions were conjugated equine estrogens (CEE) plus medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) versus placebo for women with an intact uterus and CEE alone versus placebo for women who had a hysterectomy.

All-cause mortality did not increase with HT use

The primary outcome measure was all-cause mortality in the 2 pooled trials and in each trial individually. We found that there was no link between HT and all-cause mortality in the overall study population (ages 50-79) in either trial. However, there was a trend toward lower all-cause mortality among the younger women in both trials. In women aged 50 to 59, there was a statistically significant 31% lower risk of mortality in the pooled trials among women taking active HT compared with those taking placebo, but no reduction in mortality with HT among older women (P for trend by age = .01).

Notably, all-cause mortality provides a critically important summary measure for interventions such as HT that have a complex matrix of benefits and risks. We know that HT has a number of benefits in menopausal women. It reduces hot flashes and other menopausal symptoms. It lowers the risk of hip fracture, other types of bone fractures, and type 2 diabetes. However, HT increases the risk of venous thrombosis, stroke, and some forms of cancer.

A summary measure that assesses the net effect of a medication on serious and life-threatening health outcomes is very important. As such, all-cause mortality is the ultimate bottom line for the balance of benefits and risks. This speaks to why we conducted the mortality analysis--WHI is the largest randomized trial of HT with long-term follow-up, allowing detailed analyses by age group. Although there have been previous reports on individual health outcomes in the WHI trials, no previous report had specifically focused on all-cause and cause-specific mortality with HT, stratified by age group, over long-term follow-up.

Hopefully the results of this study will alleviate some of the anxiety associated with HT because, as mentioned, there was no increase in overall total mortality or specific major causes of death. In addition, the younger women had a trend toward benefit for all-cause mortality.

We think that these findings support the recommendations from The North American Menopause Society and other professional societies that endorse the use of HT for managing bothersome menopausal symptoms, especially when started in early menopause. These results should be reassuring that there is no increase in mortality with HT use. Although these findings do not support prescribing HT for the express purpose of trying to prevent cardiovascular disease, dementia, or other chronic diseases (due to some potential risks), they do support an important role of HT for management of bothersome hot flashes, especially in early menopause.

Cause-specific mortality

Regarding cause-specific mortality and HT use, we looked in detail at deaths from cardiovascular causes, cancer, dementia, and other major illness. Overall, we observed no increase or decrease in cardiovascular or cancer deaths. In the estrogen-alone trial, there was a surprising finding of a 26% reduction in dementia deaths. In the estrogen-progestin trial, the results were neutral for dementia deaths.

Overall, the cause-specific mortality results were neutral. This is surprising because even for total cancer deaths there was no increase or decrease, despite a great deal of anxiety about cancer risk with HT. It appears that for cancer, HT has complex effects: it increases some types of cancer, such as breast cancer, and decreases others, such as endometrial cancer (in the estrogen-progestin group), and possibly colorectal cancer. Moreover, CEE alone was associated with a reduction in breast cancer mortality, but it remains unclear if this applies to other formulations. HT's net effect on total cancer mortality was neutral in both trials, that is, no increase or decrease.

Cautions and takeaways

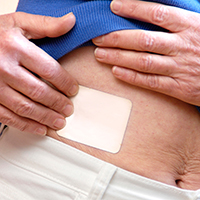

We need to keep in mind that in current clinical practice, lower doses and different formulations and routes of administration of HT are now often used, including transdermal estradiol patches, gels, sprays, and micronized progesterone. These formulations, and the lower doses, may have an even more favorable benefit-risk profile. We need additional research on the long-term benefits and risks of these newer formulations and lower dosages.

Generally, these findings from the WHI trials indicate that for women who have significant hot flashes, night sweats, or other bothersome menopausal symptoms, it's important to discuss their symptoms with their health care provider and understand that hormone therapy may be an option for them. If it's not an option, many other treatments are available, including nonhormonal prescription medications, nonprescription medications, and behavioral approaches.

These findings should alleviate some fear about HT use, especially in younger women who have an overall favorable trend in terms of all-cause mortality with treatment, plus a much lower absolute risk of adverse events than older women. In a woman in early menopause who has bothersome hot flashes or other symptoms that disrupt her sleep or impair her quality of life, it's likely that the benefits of HT will outweigh the risks.

Reference

- Manson JE, Aragaki AK, Rossouw JE, et al; for the WHI Investigators. Menopausal hormone therapy and long-term all-cause and cause-specific mortality: the Women's Health Initiative randomized trials. JAMA. 2017;318(10):927-938.

Read how the route of HT may affect sexuality outcomes.

Oral vs transdermal estrogen therapy: Is one preferable regarding sexuality?

Taylor HS, Tal A, Pal L, et al. Effects of oral vs transdermal estrogen therapy on sexual function in early post menopause: ancillary study of the Kronos Early Estrogen Prevention Study (KEEPS). JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(10):1471-1479.

If route of administration of systemic HT influences sexuality outcomes in menopausal women, this would inform how we counsel our patients regarding HT.

Recently, Taylor and colleagues conducted a randomized clinical trial to examine the effects of HT's route of administration on sexual function.8 The 4-year Kronos Early Estrogen Prevention Study (KEEPS) ancillary sexual study randomly assigned 670 recently menopausal women to 0.45 mg of oral conjugated equine estrogens (CEE), an 0.05-mg estradiol transdermal patch, or placebo (with oral micronized progesterone for those on active treatment). The participants were aged 42 to 58 years and were within 36 months from their last menstrual period.

Participants were evaluated using the Female Sexual Function Inventory (FSFI) questionnaire, which assessed desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, and pain. The FSFI is scored using a point range of 0 to 36. A higher FSFI score indicates better sexual function. An FSFI score less than 26.55 depicts low sexual function (LSF).

Transdermal estrogen improved sexual function scores

Treatment with oral CEE was associated with no significant change in FSFI score compared with placebo, although benefits were seen for lubrication. By contrast, estrogen patch use improved the FSFI score (mean improvement, 2.6). Although improvement in FSFI score with transdermal estrogen was limited to participants with baseline LSF, most participants in fact had LSF at baseline.

Oral estrogen increases the liver's production of sex hormone-binding globulin, resulting in lower free (bioavailable) testosterone. Transdermal estrogen does not produce this effect. Accordingly, sexuality concerns may represent a reason to prefer the use of transdermal as opposed to oral estrogen.

Read about the authors’ concern over new USPSTF guidance.

The USPSTF recommendation against menopausal HT use for prevention of chronic conditions: Guidance that may confuse--and mislead

US Preventive Services Task Force; Grossman DC, CurrySJ, Owens DK, et al. Hormone therapy for the primary prevention of chronic conditions in postmenopausal women: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2017;318(22):2224-2233.

In late 2017, the USPSTF issued its recommendation against the use of menopausal HT for prevention of chronic conditions.9 We are concerned that this recommendation will be misconstrued as suggesting that the use of HT is not appropriate for any indication, including treatment of bothersome menopausal symptoms.

Although the Task Force's report briefly indicated that the guidance does not refer to HT use for treatment of symptoms, this important disclaimer likely will be overlooked or ignored by many readers. The result may be increased uncertainty and anxiety in decision making regarding HT use. Thus, we might see a further decline in the proportion of menopausal women who are prescribed appropriate treatment for symptoms that impair quality of life.

HT use improves menopausal symptoms

According to the 2017 NAMS Position Statement, for symptomatic women in early menopause (that is, younger than age 60 or within 10 years of menopause onset) and free of contraindications to treatment, use of systemic HT is appropriate.7 Currently, clinicians are reluctant to prescribe HT, and women are apprehensive regarding its use.10 Unfortunately, the USPSTF guidance may further discourage appropriate treatment of menopausal symptoms.

Findings from randomized clinical trials, as well as preclinical, clinical, and epidemiologic studies, clarify the favorable benefit-risk profile for HT use by recently menopausal women with bothersome vasomotor and related menopausal symptoms.7,10-12

Notably, the USPSTF guidance does not address women with premature or early menopause, those with persistent (long-duration) vasomotor symptoms, or women at increased risk for osteoporosis and related fractures. Furthermore, the prevalent and undertreated condition, genitourinary syndrome of menopause, deserves but does not receive attention.

In recent decades, our understanding regarding HT's benefits and risks has advanced substantially. Guidance for clinicians and women should reflect this evolution and underscore the individualization and shared decision making that facilitates appropriate decisions regarding the use of HT.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Imtiaz B, Tuppurainen M, Rikkonen T, et al. Postmenopausal hormone therapy and Alzheimer disease: a prospective cohort study. Neurology. 2017;88(11):1062–1068.

- Espeland MA, Shumaker SA, Leng I, et al; WHIMSY Study Group. Long-term effects on cognitive function of postmenopausal hormone therapy prescribed to women aged 50 to 55 years. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(15):1429–1436.

- Gleason CE, Dowling NM, Wharton W, et al. Effects of hormone therapy on cognition and mood in recently postmenopausal women: findings from the randomized, controlled KEEPS-Cognitive and Affective Study. PLoS Med. 2015;12(6):e1001833;discussion e1001833.

- Henderson VW, St John JA, Hodis HN, et al. Cognitive effects of estradiol after menopause: a randomized trial of the timing hypothesis. Neurology. 2016;87(7):699–708.

- Shao H, Breitner JC, Whitmer RA, et al; Cache County Investigators. Hormone therapy and Alzheimer disease dementia: new findings from the Cache County Study. Neurology. 2012;79(18):1846–1852.

- Manson JE, Aragaki AK, Rossouw JE, et al; the WHI Investigators. Menopausal hormone therapy and long-term all-cause and cause-specific mortality: the Women’s Health Initiative randomized trials. JAMA. 2017;318(10):927–938.

- NAMS 2017 Hormone Therapy Position Statement Advisory Panel. The 2017 hormone therapy position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2017;24(7):728–753.

- Taylor HS, Tal A, Pal L, et al. Effects of oral vs transdermal estrogen therapy on sexual function in early post menopause: ancillary study of the Kronos Early Estrogen Prevention Study (KEEPS). JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(10):1471–1479.

- US Preventive Services Task Force; Grossman DC, Curry SJ, Owens DK, et al. Hormone therapy for the primary prevention of chronic conditions in postmenopausal women: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2017;318(22):2224–2233.

- Manson JE, Kaunitz AM. Menopause management—getting clinical care back on track. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(9):803–806.

- Kaunitz AM, Manson JE. Management of menopausal symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 2015; 126(4):859–876.

- Manson JE, Chlebowski RT, Stefanick ML, et al. Menopausal hormone therapy and health outcomes during the intervention and extended poststopping phases of the Women’s Health Initiative randomized trials. JAMA. 2013;310(13):1353–1368.

Our knowledge regarding the benefits and risks of systemic menopausal hormone therapy (HT) has continued to evolve since the 2002 publication of the initial findings of the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI). In late 2017, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) issued its recommendation against the use of menopausal HT for the prevention of chronic conditions. In this Menopause Update, Dr. JoAnn Manson, Dr. JoAnn Pinkerton, and I detail why we do not support the Task Force’s recommendation. In a sidebar discussion, Dr. Manson also reviews the results of 2 WHI HT trials, published in September 2017, that analyzed mortality in trial participants over an 18-year follow-up.

In addition, I summarize an observational study that assessed the association of HT and Alzheimer disease (AD) as well as a clinical trial that compared the impact of oral versus transdermal estrogen on sexuality in recently menopausal women.

What's the impact of long-term use of systemic HT on Alzheimer disease risk?

Imtiaz B, Tuppurainen M, Rikkonen T, et al. Postmenopausal hormone therapy and Alzheimer disease: a prospective cohort study. Neurology. 2017;88(11):1062-1068.

Data from the WHI HT randomized trials have clarified that initiation of oral HT among women aged 65 and older increases the risk of cognitive decline. By contrast, an analysis of younger WHI participants found that oral HT had no impact on cognitive function. Recently, Imtiaz and colleagues conducted a prospective cohort study of postmenopausal HT and AD in women residing in a Finnish county, with 25 years of follow-up. A diagnosis of AD was based on administrative health records and use of medications prescribed specifically to treat dementia. Use of systemic HT was identified via self-report. Overall, among more than 8,000 women followed, 227 cases of AD (mean age, 72 years) were identified.

In an analysis that controlled for factors including age, body mass index, alcohol use, smoking, physical activity, occupation status, and parity, up to 5 years of HT use was not associated with a risk of being diagnosed with AD. Five to 10 years of HT use was associated with a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.89, an 11% risk reduction that did not achieve statistical significance. By contrast, more than 10 years' use of systemic HT was associated with an HR of 0.53, a statistically significant 47% reduction in risk of AD.1

Other studies found conflicting results

Three large randomized trials found that HT initiated early in menopause and continued for less than 7 years had no impact on cognitive function.2-4 The Cache County (Utah) long-term prospective cohort study, however, found that HT started early in menopause and continued for 10 years or longer was associated with a significant reduction in risk of AD.5

Of note are results from the 2017 report of 18-year cumulative mortality among WHI participants (see the box on page 30). In that study, mortality from AD and other dementia was lower among participants who were randomly assigned to treatment with estrogen alone versus placebo (HR, 0.74; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.59-0.94). With estrogen-progestin therapy, the HR was 0.93 (95% CI, 0.77-1.11), and the pooled HR for the 2 trials was 0.85 (95% CI, 0.74-0.98).6

NAMS guidance

The North American Menopause Society (NAMS) HT position statement recommends that prevention of dementia should not be considered an indication for HT use since definitive data are not available.7 The statement indicates also that estrogen therapy may have positive cognitive benefits when initiated immediately after early surgical menopause and taken until the average age of menopause to prevent health risks seen with early loss of hormones.

Definitive data from long-term randomized clinical trials are not likely to become available. Observational trials continue to have methodologic issues, such as "healthy user bias," but the studies are reassuring that initiating HT close to menopause does not increase the risk of dementia. The long-term Finnish study by Imtiaz and colleagues and the Cache County study provide tentative observational data support for a "critical window" hypothesis, leaving open the possibility that initiating systemic HT soon after menopause onset and continuing it long term may reduce the risk of AD. Discussion is needed on individual patient characteristics, potential benefits and risks, and ongoing assessment over time.

Read Dr. Manson’s discussion of 18 years of follow-up data on menopause.

JoAnn E. Manson, MD, DrPH, NCMP

A new analysis from the Women's Health Initiative (WHI) randomized trials examined all-cause and cause-specific mortality during the intervention and postintervention follow-up periods.1 We followed more than 27,000 postmenopausal women aged 50 to 79 (mean age, 63) who were recruited to 2 randomized WHI trials of HT between 1993 and 1998. The trials continued until 2002 for the estrogen-progestin trial and to 2004 for the estrogen-alone trial. The trials ran for 5 to 7 years' duration, with post-stopping follow-up for an additional 10 to 12 years (total cumulative follow-up of 18 years).

The participants were randomly assigned to receive active treatment or placebo. The interventions were conjugated equine estrogens (CEE) plus medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) versus placebo for women with an intact uterus and CEE alone versus placebo for women who had a hysterectomy.

All-cause mortality did not increase with HT use

The primary outcome measure was all-cause mortality in the 2 pooled trials and in each trial individually. We found that there was no link between HT and all-cause mortality in the overall study population (ages 50-79) in either trial. However, there was a trend toward lower all-cause mortality among the younger women in both trials. In women aged 50 to 59, there was a statistically significant 31% lower risk of mortality in the pooled trials among women taking active HT compared with those taking placebo, but no reduction in mortality with HT among older women (P for trend by age = .01).

Notably, all-cause mortality provides a critically important summary measure for interventions such as HT that have a complex matrix of benefits and risks. We know that HT has a number of benefits in menopausal women. It reduces hot flashes and other menopausal symptoms. It lowers the risk of hip fracture, other types of bone fractures, and type 2 diabetes. However, HT increases the risk of venous thrombosis, stroke, and some forms of cancer.

A summary measure that assesses the net effect of a medication on serious and life-threatening health outcomes is very important. As such, all-cause mortality is the ultimate bottom line for the balance of benefits and risks. This speaks to why we conducted the mortality analysis--WHI is the largest randomized trial of HT with long-term follow-up, allowing detailed analyses by age group. Although there have been previous reports on individual health outcomes in the WHI trials, no previous report had specifically focused on all-cause and cause-specific mortality with HT, stratified by age group, over long-term follow-up.

Hopefully the results of this study will alleviate some of the anxiety associated with HT because, as mentioned, there was no increase in overall total mortality or specific major causes of death. In addition, the younger women had a trend toward benefit for all-cause mortality.

We think that these findings support the recommendations from The North American Menopause Society and other professional societies that endorse the use of HT for managing bothersome menopausal symptoms, especially when started in early menopause. These results should be reassuring that there is no increase in mortality with HT use. Although these findings do not support prescribing HT for the express purpose of trying to prevent cardiovascular disease, dementia, or other chronic diseases (due to some potential risks), they do support an important role of HT for management of bothersome hot flashes, especially in early menopause.

Cause-specific mortality

Regarding cause-specific mortality and HT use, we looked in detail at deaths from cardiovascular causes, cancer, dementia, and other major illness. Overall, we observed no increase or decrease in cardiovascular or cancer deaths. In the estrogen-alone trial, there was a surprising finding of a 26% reduction in dementia deaths. In the estrogen-progestin trial, the results were neutral for dementia deaths.

Overall, the cause-specific mortality results were neutral. This is surprising because even for total cancer deaths there was no increase or decrease, despite a great deal of anxiety about cancer risk with HT. It appears that for cancer, HT has complex effects: it increases some types of cancer, such as breast cancer, and decreases others, such as endometrial cancer (in the estrogen-progestin group), and possibly colorectal cancer. Moreover, CEE alone was associated with a reduction in breast cancer mortality, but it remains unclear if this applies to other formulations. HT's net effect on total cancer mortality was neutral in both trials, that is, no increase or decrease.

Cautions and takeaways

We need to keep in mind that in current clinical practice, lower doses and different formulations and routes of administration of HT are now often used, including transdermal estradiol patches, gels, sprays, and micronized progesterone. These formulations, and the lower doses, may have an even more favorable benefit-risk profile. We need additional research on the long-term benefits and risks of these newer formulations and lower dosages.

Generally, these findings from the WHI trials indicate that for women who have significant hot flashes, night sweats, or other bothersome menopausal symptoms, it's important to discuss their symptoms with their health care provider and understand that hormone therapy may be an option for them. If it's not an option, many other treatments are available, including nonhormonal prescription medications, nonprescription medications, and behavioral approaches.

These findings should alleviate some fear about HT use, especially in younger women who have an overall favorable trend in terms of all-cause mortality with treatment, plus a much lower absolute risk of adverse events than older women. In a woman in early menopause who has bothersome hot flashes or other symptoms that disrupt her sleep or impair her quality of life, it's likely that the benefits of HT will outweigh the risks.

Reference

- Manson JE, Aragaki AK, Rossouw JE, et al; for the WHI Investigators. Menopausal hormone therapy and long-term all-cause and cause-specific mortality: the Women's Health Initiative randomized trials. JAMA. 2017;318(10):927-938.

Read how the route of HT may affect sexuality outcomes.

Oral vs transdermal estrogen therapy: Is one preferable regarding sexuality?

Taylor HS, Tal A, Pal L, et al. Effects of oral vs transdermal estrogen therapy on sexual function in early post menopause: ancillary study of the Kronos Early Estrogen Prevention Study (KEEPS). JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(10):1471-1479.

If route of administration of systemic HT influences sexuality outcomes in menopausal women, this would inform how we counsel our patients regarding HT.

Recently, Taylor and colleagues conducted a randomized clinical trial to examine the effects of HT's route of administration on sexual function.8 The 4-year Kronos Early Estrogen Prevention Study (KEEPS) ancillary sexual study randomly assigned 670 recently menopausal women to 0.45 mg of oral conjugated equine estrogens (CEE), an 0.05-mg estradiol transdermal patch, or placebo (with oral micronized progesterone for those on active treatment). The participants were aged 42 to 58 years and were within 36 months from their last menstrual period.

Participants were evaluated using the Female Sexual Function Inventory (FSFI) questionnaire, which assessed desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, and pain. The FSFI is scored using a point range of 0 to 36. A higher FSFI score indicates better sexual function. An FSFI score less than 26.55 depicts low sexual function (LSF).

Transdermal estrogen improved sexual function scores

Treatment with oral CEE was associated with no significant change in FSFI score compared with placebo, although benefits were seen for lubrication. By contrast, estrogen patch use improved the FSFI score (mean improvement, 2.6). Although improvement in FSFI score with transdermal estrogen was limited to participants with baseline LSF, most participants in fact had LSF at baseline.

Oral estrogen increases the liver's production of sex hormone-binding globulin, resulting in lower free (bioavailable) testosterone. Transdermal estrogen does not produce this effect. Accordingly, sexuality concerns may represent a reason to prefer the use of transdermal as opposed to oral estrogen.

Read about the authors’ concern over new USPSTF guidance.

The USPSTF recommendation against menopausal HT use for prevention of chronic conditions: Guidance that may confuse--and mislead

US Preventive Services Task Force; Grossman DC, CurrySJ, Owens DK, et al. Hormone therapy for the primary prevention of chronic conditions in postmenopausal women: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2017;318(22):2224-2233.

In late 2017, the USPSTF issued its recommendation against the use of menopausal HT for prevention of chronic conditions.9 We are concerned that this recommendation will be misconstrued as suggesting that the use of HT is not appropriate for any indication, including treatment of bothersome menopausal symptoms.

Although the Task Force's report briefly indicated that the guidance does not refer to HT use for treatment of symptoms, this important disclaimer likely will be overlooked or ignored by many readers. The result may be increased uncertainty and anxiety in decision making regarding HT use. Thus, we might see a further decline in the proportion of menopausal women who are prescribed appropriate treatment for symptoms that impair quality of life.

HT use improves menopausal symptoms

According to the 2017 NAMS Position Statement, for symptomatic women in early menopause (that is, younger than age 60 or within 10 years of menopause onset) and free of contraindications to treatment, use of systemic HT is appropriate.7 Currently, clinicians are reluctant to prescribe HT, and women are apprehensive regarding its use.10 Unfortunately, the USPSTF guidance may further discourage appropriate treatment of menopausal symptoms.

Findings from randomized clinical trials, as well as preclinical, clinical, and epidemiologic studies, clarify the favorable benefit-risk profile for HT use by recently menopausal women with bothersome vasomotor and related menopausal symptoms.7,10-12

Notably, the USPSTF guidance does not address women with premature or early menopause, those with persistent (long-duration) vasomotor symptoms, or women at increased risk for osteoporosis and related fractures. Furthermore, the prevalent and undertreated condition, genitourinary syndrome of menopause, deserves but does not receive attention.

In recent decades, our understanding regarding HT's benefits and risks has advanced substantially. Guidance for clinicians and women should reflect this evolution and underscore the individualization and shared decision making that facilitates appropriate decisions regarding the use of HT.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Our knowledge regarding the benefits and risks of systemic menopausal hormone therapy (HT) has continued to evolve since the 2002 publication of the initial findings of the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI). In late 2017, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) issued its recommendation against the use of menopausal HT for the prevention of chronic conditions. In this Menopause Update, Dr. JoAnn Manson, Dr. JoAnn Pinkerton, and I detail why we do not support the Task Force’s recommendation. In a sidebar discussion, Dr. Manson also reviews the results of 2 WHI HT trials, published in September 2017, that analyzed mortality in trial participants over an 18-year follow-up.

In addition, I summarize an observational study that assessed the association of HT and Alzheimer disease (AD) as well as a clinical trial that compared the impact of oral versus transdermal estrogen on sexuality in recently menopausal women.

What's the impact of long-term use of systemic HT on Alzheimer disease risk?

Imtiaz B, Tuppurainen M, Rikkonen T, et al. Postmenopausal hormone therapy and Alzheimer disease: a prospective cohort study. Neurology. 2017;88(11):1062-1068.

Data from the WHI HT randomized trials have clarified that initiation of oral HT among women aged 65 and older increases the risk of cognitive decline. By contrast, an analysis of younger WHI participants found that oral HT had no impact on cognitive function. Recently, Imtiaz and colleagues conducted a prospective cohort study of postmenopausal HT and AD in women residing in a Finnish county, with 25 years of follow-up. A diagnosis of AD was based on administrative health records and use of medications prescribed specifically to treat dementia. Use of systemic HT was identified via self-report. Overall, among more than 8,000 women followed, 227 cases of AD (mean age, 72 years) were identified.

In an analysis that controlled for factors including age, body mass index, alcohol use, smoking, physical activity, occupation status, and parity, up to 5 years of HT use was not associated with a risk of being diagnosed with AD. Five to 10 years of HT use was associated with a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.89, an 11% risk reduction that did not achieve statistical significance. By contrast, more than 10 years' use of systemic HT was associated with an HR of 0.53, a statistically significant 47% reduction in risk of AD.1

Other studies found conflicting results

Three large randomized trials found that HT initiated early in menopause and continued for less than 7 years had no impact on cognitive function.2-4 The Cache County (Utah) long-term prospective cohort study, however, found that HT started early in menopause and continued for 10 years or longer was associated with a significant reduction in risk of AD.5

Of note are results from the 2017 report of 18-year cumulative mortality among WHI participants (see the box on page 30). In that study, mortality from AD and other dementia was lower among participants who were randomly assigned to treatment with estrogen alone versus placebo (HR, 0.74; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.59-0.94). With estrogen-progestin therapy, the HR was 0.93 (95% CI, 0.77-1.11), and the pooled HR for the 2 trials was 0.85 (95% CI, 0.74-0.98).6

NAMS guidance

The North American Menopause Society (NAMS) HT position statement recommends that prevention of dementia should not be considered an indication for HT use since definitive data are not available.7 The statement indicates also that estrogen therapy may have positive cognitive benefits when initiated immediately after early surgical menopause and taken until the average age of menopause to prevent health risks seen with early loss of hormones.

Definitive data from long-term randomized clinical trials are not likely to become available. Observational trials continue to have methodologic issues, such as "healthy user bias," but the studies are reassuring that initiating HT close to menopause does not increase the risk of dementia. The long-term Finnish study by Imtiaz and colleagues and the Cache County study provide tentative observational data support for a "critical window" hypothesis, leaving open the possibility that initiating systemic HT soon after menopause onset and continuing it long term may reduce the risk of AD. Discussion is needed on individual patient characteristics, potential benefits and risks, and ongoing assessment over time.

Read Dr. Manson’s discussion of 18 years of follow-up data on menopause.

JoAnn E. Manson, MD, DrPH, NCMP

A new analysis from the Women's Health Initiative (WHI) randomized trials examined all-cause and cause-specific mortality during the intervention and postintervention follow-up periods.1 We followed more than 27,000 postmenopausal women aged 50 to 79 (mean age, 63) who were recruited to 2 randomized WHI trials of HT between 1993 and 1998. The trials continued until 2002 for the estrogen-progestin trial and to 2004 for the estrogen-alone trial. The trials ran for 5 to 7 years' duration, with post-stopping follow-up for an additional 10 to 12 years (total cumulative follow-up of 18 years).

The participants were randomly assigned to receive active treatment or placebo. The interventions were conjugated equine estrogens (CEE) plus medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) versus placebo for women with an intact uterus and CEE alone versus placebo for women who had a hysterectomy.

All-cause mortality did not increase with HT use

The primary outcome measure was all-cause mortality in the 2 pooled trials and in each trial individually. We found that there was no link between HT and all-cause mortality in the overall study population (ages 50-79) in either trial. However, there was a trend toward lower all-cause mortality among the younger women in both trials. In women aged 50 to 59, there was a statistically significant 31% lower risk of mortality in the pooled trials among women taking active HT compared with those taking placebo, but no reduction in mortality with HT among older women (P for trend by age = .01).