User login

VA Choice Bill Defeated in the House

A U.S. House of Representatives appropriation to fund the Veterans Choice Program surprisingly went down to defeat on Monday. The VA Choice Program is set to run out of money in September, and VA officials have been calling for Congress to provide additional funding for the program. Republican leaders, hoping to expedite the bill’s passage and thinking that it was not controversial, submitted the bill in a process that required the votes of two-thirds of the representatives. The 219-186 vote fell well short of the necessary two-thirds, and voting fell largely along party lines.

Many veterans service organizations (VSOs) were critical of the bill and called on the House to make substantial changes to it. Seven VSOs signed a joint statement calling for the bill’s defeat. “As organizations who represent and support the interests of America’s 21 million veterans, and in fulfillment of our mandate to ensure that the men and women who served are able to receive the health care and benefits they need and deserve, we are calling on Members of Congress to defeat the House vote on unacceptable choice funding legislation (S. 114, with amendments),” the statement read.

AMVETS, Disabled American Veterans , Military Officers Association of America, Military Order of the Purple Heart, Veterans of Foreign Wars, Vietnam Veterans of America, and Wounded Warrior Project all signed on to the statement. The chief complaint was that the legislation “includes funding only for the ‘choice’ program which provides additional community care options, but makes no investment in VA and uses ‘savings’ from other veterans benefits or services to ‘pay’ for the ‘choice’ program.”

The bill would have allocated $2 billion for the Veterans Choice Program, taken funding for veteran housing loan fees, and would reduce the pensions for some veterans living in nursing facilities that also could be paid for under the Medicaid program.

The fate of the bill and funding for the Veterans Choice Program remains unclear. Senate and House veterans committees seem to be far apart on how to fund the program and for efforts to make more substantive changes to the program. Although House Republicans eventually may be able to pass a bill without Democrats, in the Senate, they will need the support of at least a handful of Democrats to move the bill to the President’s desk.

A U.S. House of Representatives appropriation to fund the Veterans Choice Program surprisingly went down to defeat on Monday. The VA Choice Program is set to run out of money in September, and VA officials have been calling for Congress to provide additional funding for the program. Republican leaders, hoping to expedite the bill’s passage and thinking that it was not controversial, submitted the bill in a process that required the votes of two-thirds of the representatives. The 219-186 vote fell well short of the necessary two-thirds, and voting fell largely along party lines.

Many veterans service organizations (VSOs) were critical of the bill and called on the House to make substantial changes to it. Seven VSOs signed a joint statement calling for the bill’s defeat. “As organizations who represent and support the interests of America’s 21 million veterans, and in fulfillment of our mandate to ensure that the men and women who served are able to receive the health care and benefits they need and deserve, we are calling on Members of Congress to defeat the House vote on unacceptable choice funding legislation (S. 114, with amendments),” the statement read.

AMVETS, Disabled American Veterans , Military Officers Association of America, Military Order of the Purple Heart, Veterans of Foreign Wars, Vietnam Veterans of America, and Wounded Warrior Project all signed on to the statement. The chief complaint was that the legislation “includes funding only for the ‘choice’ program which provides additional community care options, but makes no investment in VA and uses ‘savings’ from other veterans benefits or services to ‘pay’ for the ‘choice’ program.”

The bill would have allocated $2 billion for the Veterans Choice Program, taken funding for veteran housing loan fees, and would reduce the pensions for some veterans living in nursing facilities that also could be paid for under the Medicaid program.

The fate of the bill and funding for the Veterans Choice Program remains unclear. Senate and House veterans committees seem to be far apart on how to fund the program and for efforts to make more substantive changes to the program. Although House Republicans eventually may be able to pass a bill without Democrats, in the Senate, they will need the support of at least a handful of Democrats to move the bill to the President’s desk.

A U.S. House of Representatives appropriation to fund the Veterans Choice Program surprisingly went down to defeat on Monday. The VA Choice Program is set to run out of money in September, and VA officials have been calling for Congress to provide additional funding for the program. Republican leaders, hoping to expedite the bill’s passage and thinking that it was not controversial, submitted the bill in a process that required the votes of two-thirds of the representatives. The 219-186 vote fell well short of the necessary two-thirds, and voting fell largely along party lines.

Many veterans service organizations (VSOs) were critical of the bill and called on the House to make substantial changes to it. Seven VSOs signed a joint statement calling for the bill’s defeat. “As organizations who represent and support the interests of America’s 21 million veterans, and in fulfillment of our mandate to ensure that the men and women who served are able to receive the health care and benefits they need and deserve, we are calling on Members of Congress to defeat the House vote on unacceptable choice funding legislation (S. 114, with amendments),” the statement read.

AMVETS, Disabled American Veterans , Military Officers Association of America, Military Order of the Purple Heart, Veterans of Foreign Wars, Vietnam Veterans of America, and Wounded Warrior Project all signed on to the statement. The chief complaint was that the legislation “includes funding only for the ‘choice’ program which provides additional community care options, but makes no investment in VA and uses ‘savings’ from other veterans benefits or services to ‘pay’ for the ‘choice’ program.”

The bill would have allocated $2 billion for the Veterans Choice Program, taken funding for veteran housing loan fees, and would reduce the pensions for some veterans living in nursing facilities that also could be paid for under the Medicaid program.

The fate of the bill and funding for the Veterans Choice Program remains unclear. Senate and House veterans committees seem to be far apart on how to fund the program and for efforts to make more substantive changes to the program. Although House Republicans eventually may be able to pass a bill without Democrats, in the Senate, they will need the support of at least a handful of Democrats to move the bill to the President’s desk.

Establishing a Just Culture: Implications for the Veterans Health Administration Journey to High Reliability

Medical errors are a persistent problem and leading cause of preventable death in the United States. There is considerable momentum behind the idea that implementation of a just culture is foundational to detecting and learning from errors in pursuit of zero patient harm.1-6 Just culture is a framework that fosters an environment of trust within health care organizations, aiming to achieve fair outcomes for those involved in incidents or near misses. It emphasizes openness, accountability, and learning, prioritizing the repair of harm and systemic improvement over assigning blame.7

A just culture mindset reflects a significant shift in thinking that moves from the tendency to blame and punish others toward a focus on organizational learning and continued process improvement.8,9 This systemic shift in fundamental thinking transforms how leaders approach staff errors and how they are addressed.10 In essence, just culture reflects an ethos centered on openness, a deep appreciation of human fallibility, and shared accountability at both the individual and organizational levels.

Organizational learning and innovation are stifled in the absence of a just culture, and there is a tendency for employees to avoid disclosing their own errors as well as those of their colleagues.11 The transformation to a just culture is often slowed or disrupted by personal, systemic, and cultural barriers.12 It is imperative that all executive, service line, and frontline managers recognize and execute their distinct responsibilities while adjudicating the appropriate course of action in the aftermath of adverse events or near misses. This requires a nuanced understanding of the factors that contribute to errors at the individual and organizational levels to ensure an appropriate response.

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is orchestrating an enterprise transformation to develop into a high reliability organization (HRO). This began with a single-site test in 2016, which demonstrated successful results in patient safety culture, patient safety event reporting, and patient safety outcomes.13 In 2019, the VHA formally launched its enterprise-wide HRO journey in 18 hospital facilities, followed by successive waves of 67 and 54 facilities in 2021 and 2022, respectively. The VHA journey to transform into an HRO aligns with 3 pillars, 5 principles, and 7 values. The VHA has emphasized the importance of just culture as a foundational element of the HRO framework, specifically under the pillar of leadership. To promote leadership engagement, the VHA has employed an array of approaches that include education, leader coaching, and change management strategies. Given the diversity among VHA facilities, each with local cultures and histories, some sites have more readily implemented a just culture than others.14 A deeper exploration into potential obstacles, particularly concerning leadership engagement, could be instrumental for formulating strategies that further establish a just culture across the VHA.15

There is a paucity of empirical research regarding factors that facilitate and/or impede the implementation of a just culture in health care settings.16,17 Likert scale surveys, such as the Patient Safety Culture Module for the VHA All Employee Survey and its predecessor, the Patient Safety Culture Survey, have been used to assess culture and climate.18 However, qualitative evaluations directly assessing the lived experiences of those trying to implement a just culture provide additional depth and context that can help identify specific factors that support or impede becoming an HRO. The purpose of this study was to increase understanding of factors that influence the establishment and sustainment of a just culture and to identify specific methods for improving the implementation of just culture principles and practices aligned with HRO.

METHODS

This qualitative study explored facilitators and barriers to establishing and sustaining a just culture as experienced across a subset of VHA facilities by HRO leads or staff assigned with the primary responsibilities of supporting facility-level HRO transformation. HRO leads are assigned responsibility for supporting executive leadership in planning, coordinating, implementing, and monitoring activities to ensure effective high reliability efforts, including focused efforts to establish a robust patient safety program, a culture of safety, and a culture of continuous process improvement.

Virtual focus group discussions held via Microsoft Teams generated in-depth, diverse perspectives from participants across 16 VHA facilities. Qualitative research and evaluation methods provide an enhanced depth of understanding and allow the emergence of detailed data.19 A qualitative grounded theory approach elicits complex, multifaceted phenomena that cannot be appreciated solely by numeric data.20 Grounded theory was selected to limit preconceived notions and provide a more systematic analysis, including open, axial, and thematic coding. Such methods afford opportunities to adapt to unplanned follow-up questions and thus provide a flexible approach to generate new ideas and concepts.21 Additionally, qualitative methods help overcome the tendencies of respondents to agree rather than disagree when presented with Likert-style scales, which tend to skew responses toward the positive.22

Participants must have been assigned as an HRO lead for ≥ 6 months at the same facility. Potential participants were identified through purposive sampling, considering their leadership roles in HRO and experience with just culture implementation, the size and complexity of their facility, and geographic distribution. Invitations explaining the study and encouraging voluntary participation to participate were emailed. Of 37 HRO leads invited to participate in the study, 16 agreed to participate and attended 1 of 3 hour-long focus group sessions. One session was rescheduled due to limited attendance. Participants represented a mix of VHA sites in terms of geography, facility size, and complexity.

Focus Group Procedures

Demographic data were collected prior to sessions via an online form to better understand the participant population, including facility complexity level, length of time in HRO lead role, clinical background, and facility level just culture training. Each session was led by an experienced focus group facilitator (CV) who was not directly involved with the overall HRO implementation to establish a neutral perspective. Each session was attended by 4 to 7 participants and 2 observers who took notes. The sessions were recorded and included automated transcriptions, which were edited for accuracy.

Focus group sessions began with a brief introduction and an opportunity for participants to ask questions. Participants were then asked a series of open-ended questions to elicit responses regardingfacilitators, barriers, and leadership support needed for implementing just culture. The questions were part of a facilitator guide that included an introductory script and discussion prompts to ensure consistency across focus groups.

Facilitators were defined as factors that increase the likelihood of establishing or sustaining a just culture. Barriers were defined as factors that decrease or inhibit the likelihood of establishing or sustaining just culture. The focus group facilitator encouraged all participants to share their views and provided clarification if needed, as well as prompts and examples where appropriate, but primarily sought to elicit responses to the questions.

Institutional review board review and approval were not required for this quality improvement initiative. The project adhered to ethical standards of research, including asking participants for verbal consent and preserving their confidentiality. Participation was voluntary, and prior to the focus group sessions, participants were provided information explaining the study’s purpose, procedures, and their rights. Participant identities were kept confidential, and all data were anonymized during the analysis phase. Pseudonyms or identifiers were used during data transcription to protect participant identity. All data, including recordings and transcriptions, were stored on password-protected devices accessible only to the research team. Any identifiable information was removed during data analysis to ensure confidentiality.

Analysis

Focus group recordings were transcribed verbatim, capturing all verbal interactions and nonverbal cues that may contribute to understanding the participants' perspectives. Thematic analysis was used to analyze the qualitative data from the focus group discussions.23 The transcribed data were organized, coded, and analyzed using ATLAS.ti 23 qualitative data software to identify key themes and patterns.

Results

The themes identified include the 5 facilitators, barriers, and recommendations most frequently mentioned by HRO leads across focus group sessions. The nature of each theme is described, along with commonly mentioned examples and direct quotes from participants that illustrate our understanding of their perspectives.

Facilitators

Training and coaching (26 responses). The availability of training around the Just Culture Decision Support Tool (DST) was cited as a practical aid in guiding leaders through complex just culture decisions to ensure consistency and fairness. Additionally, an executive leadership team that served as champions for just culture principles played a vital role in promoting and sustaining the approach: “Training them on the roll-out of the decision support tool with supervisors at all levels, and education for just culture and making it part of our safety forum has helped for the last 4 months.” “Having some regular training and share-out cadences embedded within the schedule as well as dynamic directors and well-trained executive leadership team (ELT) for support has been a facilitator.”

Increased transparency (16 responses). Participants consistently highlighted the importance of leadership transparency as a key facilitator for implementing just culture. Open and honest communication from top-level executives fostered an environment of trust and accountability. Approachable and physically present leadership was seen as essential for creating a culture where employees felt comfortable reporting errors and concerns without fear of retaliation: “They’re surprisingly honest with themselves about what we can do, what we cannot do, and they set the expectations exactly at that.”

Approachable leadership (15 responses). Participants frequently mentioned the importance of having dynamic leadership spearheading the implementation of just culture and leading by example. Having a leadership team that accepts accountability and reinforces consistency in the manner that near misses or mistakes are addressed is paramount to promoting the principles of just culture and increasing psychological safety: “We do have very approachable leadership, which I know is hard if you’re trying to implement that nationwide, it’s hard to implement approachability. But I do think that people raise their concerns, and they’ll stop them in the hallway and ask them questions. So, in terms of comfort level with the executive leadership, I do think that’s high, which would promote psychological safety.”

Feedback loops and follow through (13 responses). Participants emphasized the importance of taking concrete actions to address concerns and improve processes. Regular check-ins with supervisors to discuss matters related to just culture provided a structured opportunity for addressing issues and reinforcing the importance of the approach: “One thing that we’ve really focused on is not only identifying mistakes, but [taking] ownership. We continue to track it until … it’s completed and then a process of how to communicate that back and really using closed loop communication with the staff and letting them know.”

Forums and town halls (10 responses). These platforms created feedback loops that were seen as invaluable tools for sharing near misses, celebrating successes, and promoting open dialogue. Forums and town halls cultivated a culture of continuous improvement and trust: “We’ll celebrate catches, a safety story is inside that catch. So, if we celebrate the change, people feel safer to speak up.” “Truthfully, we’ve had a great relationship since establishing our safety forums and just value open lines of communication.”

Barriers

Inadequate training (30 responses). Insufficient engagement during training—limited bandwidth and availability to attend and actively participate in training—was perceived as detrimental to creating awareness and buy-in from staff, supervisors, and leadership, thereby hindering successful integration of just culture principles. Participants also identified too many conflicting priorities from VHA leadership, which contributes to training and information fatigue among staff and supervisors. “Our biggest barrier is just so many different competing priorities going on. We have so much that we’re asking people to do.” “One hundred percent training is feeling more like a ticked box than actually yielding results, I have a very hard time getting staff engaged.”

Inconsistency between executive leaders and middle managers (28 responses). A lack of consistency in the commitment to and enactment of just culture principles among leaders poses a challenge. Participants gave several examples of inconsistencies in messaging and reinforcement of just culture principles, leading to confusion among staff and hindering adoption. Likewise, the absence of standardized procedures for implementing just culture created variability: “The director coming in and trying to change things, it put a lot of resistance, we struggle with getting the other ELT members on board … some of the messages that come out at times can feel more punitive.”

Middle management resistance (22 responses). In some instances, participants reported middle managers exhibiting attitudes and behaviors that undermined the application of just culture principles and effectiveness. Such attitudes and behaviors were attributed to a lack of adequate training, coaching, and awareness. Other perceived contributions included fear of failure and a desire to distance oneself from staff who have made mistakes: “As soon as someone makes an error, they go straight to suspend them, and that’s the disconnect right there.” “There’s almost a level of working in the opposite direction in some of the mid-management.”

Cultural misalignment (18 responses). The existing culture of distancing oneself from mistakes presented a significant barrier to the adoption of just culture because it clashed with the principles of open reporting and accountability. Staff underreported errors or framed them in a way that minimized personal responsibility, thereby making it more essential to put in the necessary and difficult work to learn from mistakes: “One, you’re going to get in trouble. There’s going to be more work added to you or something of that nature."

Lack of accountability for opposition(17 responses). Participants noted a clear lack of accountability for those who opposed or showed resistance to just culture, which allowed resistance to persist without consequences. In many instances, leaders were described as having overlooked repeated instances of unjust attitudes and behaviors (eg, inappropriate blame or punishment), which allowed those practices to continue. “Executive leadership is standing on the hill and saying we’re a just culture and we do everything correctly, and staff has the expectation that they’re going to be treated with just culture and then the middle management is setting that on fire, then we show them that that’s not just culture, and they continue to have those poor behaviors, but there’s a lack of accountability.”

Limited bandwidth and lack of coordination (14 responses). HRO leads often faced role-specific constraints in having adequate time and authority to coordinate efforts to implement or sustain just culture. This includes challenges with coordination across organizational levels (eg, between the hospital and regional Veterans Integrated Service Network [VISN] management levels) and across departments within the hospital (eg, between human resources and service lines or units). “Our VISN human resources is completely detached. They’ll not cooperate with these efforts, which is hard.” “There’s not enough bandwidth to actually support, I’m just 1 person.” “[There’s] all these mandated trainings of 8 hours when we’re already fatigued, short-staffed, taking 3 other HRO classes.”

Recommendations

Training improvements (24 responses). HRO leads recommended that comprehensive training programs be developed and implemented for staff, supervisors, and leadership to increase awareness and understanding of just culture principles. These training initiatives should focus on fostering a shared understanding of the core tenets of just culture, the importance of error reporting, and the processes involved in fair and consistent decision making (eg, training simulations on use of the Just Culture DST). “We’ve really never had any formal training on the decision support tool. I hope that what’s coming out for next year. We’ll have some more formal training for the tool because I think it would be great to really have our leadership and our supervisors and our managers use that tool.” “We can give a more directed and intentional training to leadership on the 4 foundational practices and what it means to implement those and what it means to utilize that behavioral component of HRO.”

Clear and consistent procedures toincrease accountability (22 responses). To promote a culture of accountability and consistency in the application of just culture principles, organizations should establish clear mechanisms for reporting, investigating, and addressing incidents. Standardized procedures and DSTs can aid in ensuring that responses to errors are equitable and align with just culture principles: “I recommend accountability; if it’s clearly evidenced that you’re not toeing the just culture line, then we need to be able to do something about it and not just finger wag.” “[We need to have] a templated way to approach just culture implementation. The decision support tool is great, I absolutely love having the resources and being able to find a lot of clinical examples and discussion tools like that. But when it comes down to it, not having that kind of official thing to fall back on it can be a little bit rough.”

Additional coaching and consultationsupport (15 responses). To support supervisors in effectively implementing just culture within their teams, participants recommended that organizations provide ongoing coaching and mentorship opportunities. Additionally, third-party consultants with expertise in just culture were described as offering valuable guidance, particularly in cases where internal staff resources or HRO lead bandwidth may be limited. “There are so many consulting agencies with HRO that have been contracted to do different projects, but maybe that can help with an educational program.” “I want to see my executive leadership coach the supervisors up right and then allow them to do one-on-ones and facilitate and empower the frontline staff, and it’s just a good way of transparency and communication.”

Improved leadership sponsorship (15 responses). Participants noted that leadership buy-in is crucial for the successful implementation of just culture. Facilities should actively engage and educate leadership teams on the benefits of just culture and how it aligns with broader patient safety and organizational goals. Leaders should be visible and active champions of its principles, supporting change in their daily engagements with staff. “ELT support is absolutely necessary. Why? Because they will make it important to those in their service lines. They will make it important to those supervisors and managers. If it’s not important to that ELT member, then it’s not going to be important to that manager or that supervisor.”

Improved collaboration with patient safety and human resources (6 responses). Collaborative efforts with patient safety and human resources departments were seen as instrumental in supporting just culture, emphasizing its importance, and effectively addressing issues. Coordinating with these departments specifically contributes to consistent reinforcement and expands the bandwidth of HRO leads. These departments play integral roles in supporting just culture through effective policies, procedures, and communication. “I think it would be really helpful to have common language between what human resources teaches and what is in our decision support tool.”

DISCUSSION

This study sought to collect and synthesize the experiences of leaders across a large, integrated health care system in establishing and sustaining a just culture as part of an enterprise journey to become an HRO.24 The VHA has provided enterprise-wide support (eg, training, leader coaching, and communications) for the implementation of HRO principles and practices with the goal of creating a culture of safety, which includes just culture elements. This support includes enterprise program offices, VISNs, and hospital facilities, though notably, there is variability in how HRO is implemented at the local level. The facilitators, barriers, and recommendations presented in this article are representative of the designated HRO leads at VHA hospital facilities who have direct experience with implementing and sustaining just culture. The themes presented offer specific opportunities for intervention and actionable strategies to enhance just culture initiatives, foster psychological safety and accountability, and ultimately improve the quality of care and patient outcomes.3,25

Frequently identified facilitators such as providing training and coaching, having leaders who are available and approachable, demonstrating follow-through to address identified issues, and creating venues where errors and successes can be openly discussed.26 These facilitators are aligned with enterprise HRO support strategies orchestrated by the VHA at the enterprise VISN and facility levels to support a culture of safety, continuous process improvement, and leadership commitment.

Frequently identified barriers included inadequate training, inconsistent application of just culture by middle managers vs senior leaders, a lack of accountability or corrective action when unjust corrective actions took place, time and resource constraints, and inadequate coordination across departments (eg, operational departments and human resources) and organizational levels. These factors were identified through focus groups with a limited set of HRO leads. They may reflect challenges to changing culture that may be deeply engrained in individual histories, organizational norms, and systemic practices. Improving upon these just culture initiatives requires multifaceted approaches and working through resistance to change.

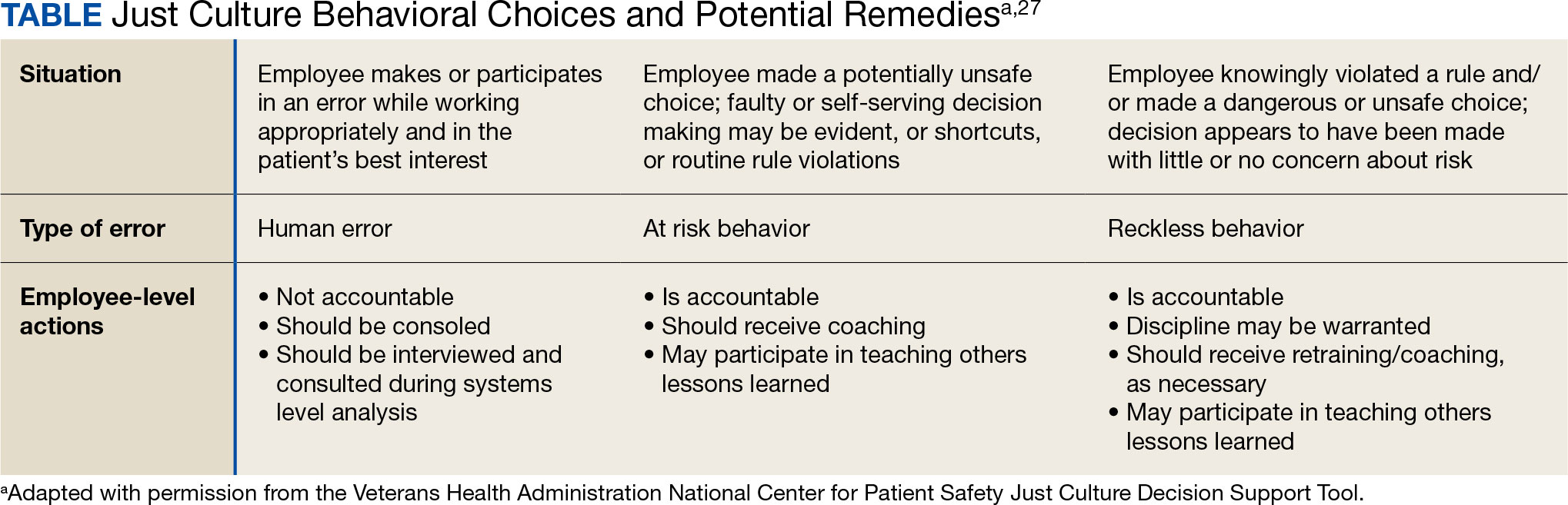

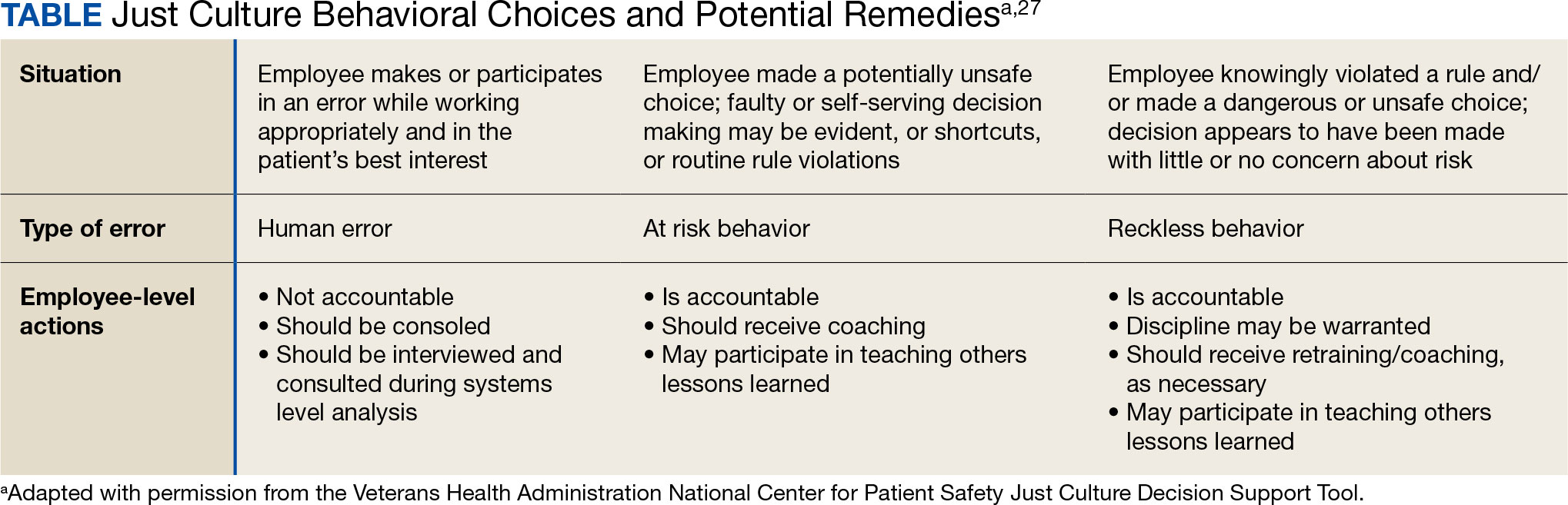

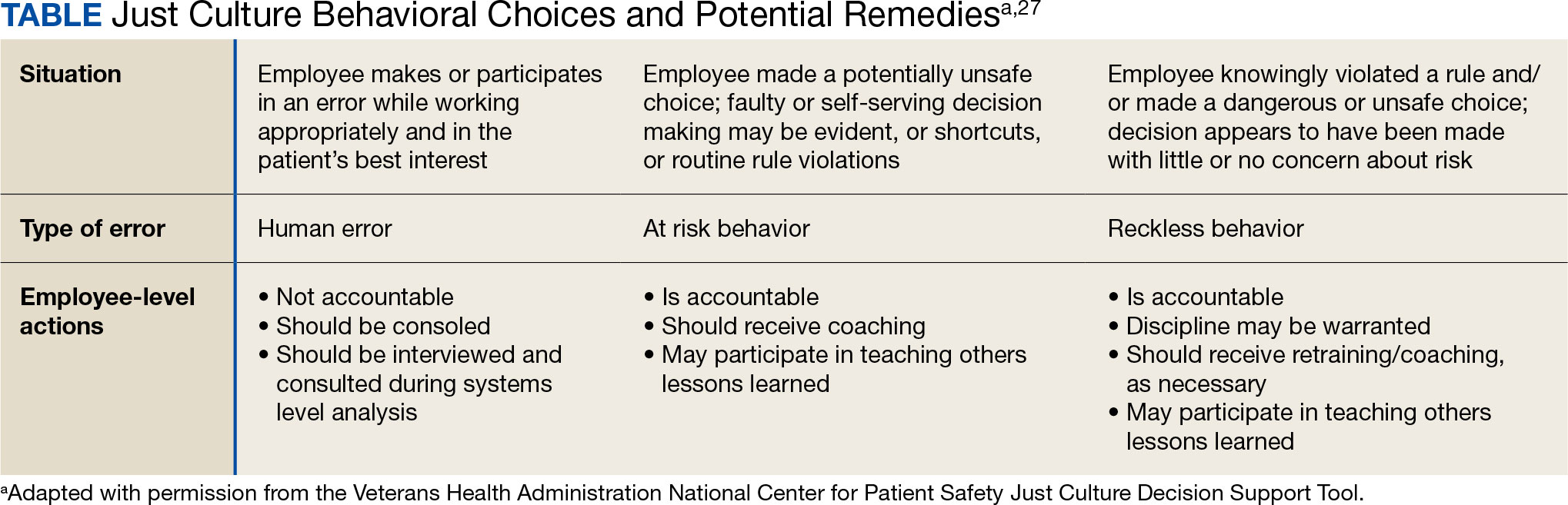

VHA HRO leads identified several actionable recommendations that may be used in pursuit of a just culture. First, improvements in training involving how to apply just culture principles and, specifically, the use of the Just Culture DST were identified as an opportunity for improvement. The VHA National Center for Patient Safety developed the DST as an aid for leaders to effectively address errors in line with just culture principles, balancing individual and system accountability.27 The DST specifically addresses human error as well as risky and reckless behavior, and it clarifies the delineation between individual and organizational accountability (Table).3

Scenario-based interactive training and simulations may prove especially useful for middle managers and frontline supervisors who are closest to errors. Clear and repeatable procedures for determining courses of action for accountability in response are needed, and support for their application must be coordinated across multiple departments (eg, patient safety and human resources) to ensure consistency and fairness. Coaching and consultation are also viewed as beneficial in supporting applications. Coaching is provided to senior leaders across most facilities, but the availability of specific, role-based coaching and training is more limited for middle managers and frontline supervisors who may benefit most from hands-on support.

Lastly, sponsorship from leaders was viewed as critical to success, but follow through to ensure support flows down from the executive suite to the frontline is variable across facilities and requires consistent effort over time. This is especially challenging given the frequent turnover in leadership roles evident in the VHA and other health care systems.

Limitations

This study employed qualitative methods and sampled a relatively small subset of experienced leaders with specific roles in implementing HRO in the VHA. Thus, it should not be considered representative of the perspectives of all leaders within the VHA or other health care systems. Future studies should assess facilitators and barriers beyond the facility level, including a focus incorporating both the VISN and VHA. More broadly, qualitative methods such as those employed in this study offer great depth and nuance but have limited ability to identify system-wide trends and differences. As such, it may be beneficial to specifically look at sites that are high- or low-performing on measures of patient safety culture to identify differences that may inform implementation strategies based on organizational maturity and readiness for change.

Conclusions

Successful implementation of these recommendations will require ongoing commitment, collaboration, and a sustained effort from all stakeholders involved at multiple levels of the health care system. Monitoring and evaluating progress should be conducted regularly to ensure that recommendations lead to improvements in implementing just culture principles. This quality improvement study adds to the knowledge base on factors that impact the just culture and broader efforts to realize HRO principles and practices in health care systems. The approach of this study may serve as a model for identifying opportunities to improve HRO implementation within the VHA and other settings, especially when paired with ongoing quantitative evaluation of organizational safety culture, just culture behaviors, and patient outcomes.

- Aljabari S, Kadhim Z. Common barriers to reporting medical errors. ScientificWorldJournal. 2021;2021:6494889. doi:10.1155/2021/6494889

- Arnal-Velasco D, Heras-Hernando V. Learning from errors and resilience. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2023;36(3):376-381. doi:10.1097/ACO.0000000000001257

- Murray JS, Clifford J, Larson S, Lee JK, Sculli GL. Implementing just culture to improve patient safety. Mil Med. doi:10.1093/milmed/usac115

- Murray JS, Kelly S, Hanover C. Promoting psychological safety in healthcare organizations. Mil Med. 2022;187(7-8):808-810. doi:10.1093/milmed/usac041

- van Baarle E, Hartman L, Rooijakkers S, et al. Fostering a just culture in healthcare organizations: experiences in practice. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22(1):1035. doi:10.1186/s12913-022-08418-z

- Weenink JW, Wallenburg I, Hartman L, et al. Role of the regulator in enabling a just culture: a qualitative study in mental health and hospital care. BMJ Open. 2022;12(7):e061321. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2022-061321

- White RM, Delacroix R. Second victim phenomenon: is ‘just culture’ a reality? An integrative review. Appl Nurs Res. 2020;56:151319. doi:10.1016/j.apnr.2020.151319

- Cribb A, O’Hara JK, Waring J. Improving responses to safety incidents: we need to talk about justice. BMJ Qual Saf. 2022;31(4):327-330. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2021-014333

- Rocco C, Rodríguez AM, Noya B. Elimination of punitive outcomes and criminalization of medical errors. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2022;35(6):728-732. doi:10.1097/ACO.0000000000001197

- Dekker S, Rafferty J, Oates A. Restorative Just Culture in Practice: Implementation and Evaluation. Routledge; 2022.

- Brattebø G, Flaatten HK. Errors in medicine: punishment versus learning medical adverse events revisited - expanding the frame. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2023;36(2):240-245. doi:10.1097/ACO.0000000000001235

- Shabel W, Dennis JL. Missouri’s just culture collaborative. J Healthc Risk Manag. 2012;32(2):38-43. doi:10.1002/jhrm.21093

- Sculli GL, Pendley-Louis R, Neily J, et al. A high-reliability organization framework for health care: a multiyear implementation strategy and associated outcomes. J Patient Saf. 2022;18(1):64-70. doi:10.1097/PTS.0000000000000788

- Martin G, Chew S, McCarthy I, Dawson J, Dixon-Woods M. Encouraging openness in health care: policy and practice implications of a mixed-methods study in the English National Health Service. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2023;28(1):14-24. doi:10.1177/13558196221109053

- Siewert B, Brook OR, Swedeen S, Eisenberg RL, Hochman M. Overcoming human barriers to safety event reporting in radiology. Radiographics. 2019;39(1):251-263. doi:10.1148/rg.2019180135

- Barkell NP, Snyder SS. Just culture in healthcare: an integrative review. Nurs Forum. 2021;56(1):103-111. doi:10.1111/nuf.12525

- Murray JS, Lee J, Larson S, Range A, Scott D, Clifford J. Requirements for implementing a ‘just culture’ within healthcare organisations: an integrative review. BMJ Open Qual. 2023;12(2)e002237. doi:10.1136/bmjoq-2022-002237

- Mohr DC, Chen C, Sullivan J, Gunnar W, Damschroder L. Development and validation of the Veterans Health Administration patient safety culture survey. J Patient Saf. 2022;18(6):539-545. doi:10.1097/PTS.0000000000001027

- Creswell JW. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. 4th ed. SAGE Publications, Inc.; 2014.

- Patton MQ. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods: Integrating Theory and Practice. 4th ed. SAGE Publications, Inc.; 2015.

- Maxwell JA. Qualitative Research Design: An Interactive Approach. 3rd ed. SAGE Publications, Inc.; 2013.

- Krumpal I. Determinants of social desirability bias in sensitive surveys: a literature review. Qual Quant. 2013;47(4):2025-2047. doi:10.1007/s11135-011-9640-9

- Braun V, Clarke V. Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide. SAGE Publications, Inc; 2021.

- Cox GR, Starr LM. VHA’s movement for change: implementing high-reliability principles and practices. J Healthc Manag. 2023;68(3):151-157. doi:10.1097/JDM-D-23-00056

- Dietl JE, Derksen C, Keller FM, Lippke S. Interdisciplinary and interprofessional communication intervention: how psychological safety fosters communication and increases patient safety. Front Psychol. 2023;14:1164288. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1164288

- Eng DM, Schweikart SJ. Why accountability sharing in health care organizational cultures means patients are probably safer. AMA J Ethics. 2020;22(9):E779-E783. doi:10.1001/amajethics.2020.779

- Veterans Health Administration National Center for Patient Safety. Just Culture Decision Support Tool. Revised May 2021. Accessed August 5, 2024.https://www.patientsafety.va.gov/docs/Just-Culture-Decision-Support-Tool-2022.pdf

Medical errors are a persistent problem and leading cause of preventable death in the United States. There is considerable momentum behind the idea that implementation of a just culture is foundational to detecting and learning from errors in pursuit of zero patient harm.1-6 Just culture is a framework that fosters an environment of trust within health care organizations, aiming to achieve fair outcomes for those involved in incidents or near misses. It emphasizes openness, accountability, and learning, prioritizing the repair of harm and systemic improvement over assigning blame.7

A just culture mindset reflects a significant shift in thinking that moves from the tendency to blame and punish others toward a focus on organizational learning and continued process improvement.8,9 This systemic shift in fundamental thinking transforms how leaders approach staff errors and how they are addressed.10 In essence, just culture reflects an ethos centered on openness, a deep appreciation of human fallibility, and shared accountability at both the individual and organizational levels.

Organizational learning and innovation are stifled in the absence of a just culture, and there is a tendency for employees to avoid disclosing their own errors as well as those of their colleagues.11 The transformation to a just culture is often slowed or disrupted by personal, systemic, and cultural barriers.12 It is imperative that all executive, service line, and frontline managers recognize and execute their distinct responsibilities while adjudicating the appropriate course of action in the aftermath of adverse events or near misses. This requires a nuanced understanding of the factors that contribute to errors at the individual and organizational levels to ensure an appropriate response.

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is orchestrating an enterprise transformation to develop into a high reliability organization (HRO). This began with a single-site test in 2016, which demonstrated successful results in patient safety culture, patient safety event reporting, and patient safety outcomes.13 In 2019, the VHA formally launched its enterprise-wide HRO journey in 18 hospital facilities, followed by successive waves of 67 and 54 facilities in 2021 and 2022, respectively. The VHA journey to transform into an HRO aligns with 3 pillars, 5 principles, and 7 values. The VHA has emphasized the importance of just culture as a foundational element of the HRO framework, specifically under the pillar of leadership. To promote leadership engagement, the VHA has employed an array of approaches that include education, leader coaching, and change management strategies. Given the diversity among VHA facilities, each with local cultures and histories, some sites have more readily implemented a just culture than others.14 A deeper exploration into potential obstacles, particularly concerning leadership engagement, could be instrumental for formulating strategies that further establish a just culture across the VHA.15

There is a paucity of empirical research regarding factors that facilitate and/or impede the implementation of a just culture in health care settings.16,17 Likert scale surveys, such as the Patient Safety Culture Module for the VHA All Employee Survey and its predecessor, the Patient Safety Culture Survey, have been used to assess culture and climate.18 However, qualitative evaluations directly assessing the lived experiences of those trying to implement a just culture provide additional depth and context that can help identify specific factors that support or impede becoming an HRO. The purpose of this study was to increase understanding of factors that influence the establishment and sustainment of a just culture and to identify specific methods for improving the implementation of just culture principles and practices aligned with HRO.

METHODS

This qualitative study explored facilitators and barriers to establishing and sustaining a just culture as experienced across a subset of VHA facilities by HRO leads or staff assigned with the primary responsibilities of supporting facility-level HRO transformation. HRO leads are assigned responsibility for supporting executive leadership in planning, coordinating, implementing, and monitoring activities to ensure effective high reliability efforts, including focused efforts to establish a robust patient safety program, a culture of safety, and a culture of continuous process improvement.

Virtual focus group discussions held via Microsoft Teams generated in-depth, diverse perspectives from participants across 16 VHA facilities. Qualitative research and evaluation methods provide an enhanced depth of understanding and allow the emergence of detailed data.19 A qualitative grounded theory approach elicits complex, multifaceted phenomena that cannot be appreciated solely by numeric data.20 Grounded theory was selected to limit preconceived notions and provide a more systematic analysis, including open, axial, and thematic coding. Such methods afford opportunities to adapt to unplanned follow-up questions and thus provide a flexible approach to generate new ideas and concepts.21 Additionally, qualitative methods help overcome the tendencies of respondents to agree rather than disagree when presented with Likert-style scales, which tend to skew responses toward the positive.22

Participants must have been assigned as an HRO lead for ≥ 6 months at the same facility. Potential participants were identified through purposive sampling, considering their leadership roles in HRO and experience with just culture implementation, the size and complexity of their facility, and geographic distribution. Invitations explaining the study and encouraging voluntary participation to participate were emailed. Of 37 HRO leads invited to participate in the study, 16 agreed to participate and attended 1 of 3 hour-long focus group sessions. One session was rescheduled due to limited attendance. Participants represented a mix of VHA sites in terms of geography, facility size, and complexity.

Focus Group Procedures

Demographic data were collected prior to sessions via an online form to better understand the participant population, including facility complexity level, length of time in HRO lead role, clinical background, and facility level just culture training. Each session was led by an experienced focus group facilitator (CV) who was not directly involved with the overall HRO implementation to establish a neutral perspective. Each session was attended by 4 to 7 participants and 2 observers who took notes. The sessions were recorded and included automated transcriptions, which were edited for accuracy.

Focus group sessions began with a brief introduction and an opportunity for participants to ask questions. Participants were then asked a series of open-ended questions to elicit responses regardingfacilitators, barriers, and leadership support needed for implementing just culture. The questions were part of a facilitator guide that included an introductory script and discussion prompts to ensure consistency across focus groups.

Facilitators were defined as factors that increase the likelihood of establishing or sustaining a just culture. Barriers were defined as factors that decrease or inhibit the likelihood of establishing or sustaining just culture. The focus group facilitator encouraged all participants to share their views and provided clarification if needed, as well as prompts and examples where appropriate, but primarily sought to elicit responses to the questions.

Institutional review board review and approval were not required for this quality improvement initiative. The project adhered to ethical standards of research, including asking participants for verbal consent and preserving their confidentiality. Participation was voluntary, and prior to the focus group sessions, participants were provided information explaining the study’s purpose, procedures, and their rights. Participant identities were kept confidential, and all data were anonymized during the analysis phase. Pseudonyms or identifiers were used during data transcription to protect participant identity. All data, including recordings and transcriptions, were stored on password-protected devices accessible only to the research team. Any identifiable information was removed during data analysis to ensure confidentiality.

Analysis

Focus group recordings were transcribed verbatim, capturing all verbal interactions and nonverbal cues that may contribute to understanding the participants' perspectives. Thematic analysis was used to analyze the qualitative data from the focus group discussions.23 The transcribed data were organized, coded, and analyzed using ATLAS.ti 23 qualitative data software to identify key themes and patterns.

Results

The themes identified include the 5 facilitators, barriers, and recommendations most frequently mentioned by HRO leads across focus group sessions. The nature of each theme is described, along with commonly mentioned examples and direct quotes from participants that illustrate our understanding of their perspectives.

Facilitators

Training and coaching (26 responses). The availability of training around the Just Culture Decision Support Tool (DST) was cited as a practical aid in guiding leaders through complex just culture decisions to ensure consistency and fairness. Additionally, an executive leadership team that served as champions for just culture principles played a vital role in promoting and sustaining the approach: “Training them on the roll-out of the decision support tool with supervisors at all levels, and education for just culture and making it part of our safety forum has helped for the last 4 months.” “Having some regular training and share-out cadences embedded within the schedule as well as dynamic directors and well-trained executive leadership team (ELT) for support has been a facilitator.”

Increased transparency (16 responses). Participants consistently highlighted the importance of leadership transparency as a key facilitator for implementing just culture. Open and honest communication from top-level executives fostered an environment of trust and accountability. Approachable and physically present leadership was seen as essential for creating a culture where employees felt comfortable reporting errors and concerns without fear of retaliation: “They’re surprisingly honest with themselves about what we can do, what we cannot do, and they set the expectations exactly at that.”

Approachable leadership (15 responses). Participants frequently mentioned the importance of having dynamic leadership spearheading the implementation of just culture and leading by example. Having a leadership team that accepts accountability and reinforces consistency in the manner that near misses or mistakes are addressed is paramount to promoting the principles of just culture and increasing psychological safety: “We do have very approachable leadership, which I know is hard if you’re trying to implement that nationwide, it’s hard to implement approachability. But I do think that people raise their concerns, and they’ll stop them in the hallway and ask them questions. So, in terms of comfort level with the executive leadership, I do think that’s high, which would promote psychological safety.”

Feedback loops and follow through (13 responses). Participants emphasized the importance of taking concrete actions to address concerns and improve processes. Regular check-ins with supervisors to discuss matters related to just culture provided a structured opportunity for addressing issues and reinforcing the importance of the approach: “One thing that we’ve really focused on is not only identifying mistakes, but [taking] ownership. We continue to track it until … it’s completed and then a process of how to communicate that back and really using closed loop communication with the staff and letting them know.”

Forums and town halls (10 responses). These platforms created feedback loops that were seen as invaluable tools for sharing near misses, celebrating successes, and promoting open dialogue. Forums and town halls cultivated a culture of continuous improvement and trust: “We’ll celebrate catches, a safety story is inside that catch. So, if we celebrate the change, people feel safer to speak up.” “Truthfully, we’ve had a great relationship since establishing our safety forums and just value open lines of communication.”

Barriers

Inadequate training (30 responses). Insufficient engagement during training—limited bandwidth and availability to attend and actively participate in training—was perceived as detrimental to creating awareness and buy-in from staff, supervisors, and leadership, thereby hindering successful integration of just culture principles. Participants also identified too many conflicting priorities from VHA leadership, which contributes to training and information fatigue among staff and supervisors. “Our biggest barrier is just so many different competing priorities going on. We have so much that we’re asking people to do.” “One hundred percent training is feeling more like a ticked box than actually yielding results, I have a very hard time getting staff engaged.”

Inconsistency between executive leaders and middle managers (28 responses). A lack of consistency in the commitment to and enactment of just culture principles among leaders poses a challenge. Participants gave several examples of inconsistencies in messaging and reinforcement of just culture principles, leading to confusion among staff and hindering adoption. Likewise, the absence of standardized procedures for implementing just culture created variability: “The director coming in and trying to change things, it put a lot of resistance, we struggle with getting the other ELT members on board … some of the messages that come out at times can feel more punitive.”

Middle management resistance (22 responses). In some instances, participants reported middle managers exhibiting attitudes and behaviors that undermined the application of just culture principles and effectiveness. Such attitudes and behaviors were attributed to a lack of adequate training, coaching, and awareness. Other perceived contributions included fear of failure and a desire to distance oneself from staff who have made mistakes: “As soon as someone makes an error, they go straight to suspend them, and that’s the disconnect right there.” “There’s almost a level of working in the opposite direction in some of the mid-management.”

Cultural misalignment (18 responses). The existing culture of distancing oneself from mistakes presented a significant barrier to the adoption of just culture because it clashed with the principles of open reporting and accountability. Staff underreported errors or framed them in a way that minimized personal responsibility, thereby making it more essential to put in the necessary and difficult work to learn from mistakes: “One, you’re going to get in trouble. There’s going to be more work added to you or something of that nature."

Lack of accountability for opposition(17 responses). Participants noted a clear lack of accountability for those who opposed or showed resistance to just culture, which allowed resistance to persist without consequences. In many instances, leaders were described as having overlooked repeated instances of unjust attitudes and behaviors (eg, inappropriate blame or punishment), which allowed those practices to continue. “Executive leadership is standing on the hill and saying we’re a just culture and we do everything correctly, and staff has the expectation that they’re going to be treated with just culture and then the middle management is setting that on fire, then we show them that that’s not just culture, and they continue to have those poor behaviors, but there’s a lack of accountability.”

Limited bandwidth and lack of coordination (14 responses). HRO leads often faced role-specific constraints in having adequate time and authority to coordinate efforts to implement or sustain just culture. This includes challenges with coordination across organizational levels (eg, between the hospital and regional Veterans Integrated Service Network [VISN] management levels) and across departments within the hospital (eg, between human resources and service lines or units). “Our VISN human resources is completely detached. They’ll not cooperate with these efforts, which is hard.” “There’s not enough bandwidth to actually support, I’m just 1 person.” “[There’s] all these mandated trainings of 8 hours when we’re already fatigued, short-staffed, taking 3 other HRO classes.”

Recommendations

Training improvements (24 responses). HRO leads recommended that comprehensive training programs be developed and implemented for staff, supervisors, and leadership to increase awareness and understanding of just culture principles. These training initiatives should focus on fostering a shared understanding of the core tenets of just culture, the importance of error reporting, and the processes involved in fair and consistent decision making (eg, training simulations on use of the Just Culture DST). “We’ve really never had any formal training on the decision support tool. I hope that what’s coming out for next year. We’ll have some more formal training for the tool because I think it would be great to really have our leadership and our supervisors and our managers use that tool.” “We can give a more directed and intentional training to leadership on the 4 foundational practices and what it means to implement those and what it means to utilize that behavioral component of HRO.”

Clear and consistent procedures toincrease accountability (22 responses). To promote a culture of accountability and consistency in the application of just culture principles, organizations should establish clear mechanisms for reporting, investigating, and addressing incidents. Standardized procedures and DSTs can aid in ensuring that responses to errors are equitable and align with just culture principles: “I recommend accountability; if it’s clearly evidenced that you’re not toeing the just culture line, then we need to be able to do something about it and not just finger wag.” “[We need to have] a templated way to approach just culture implementation. The decision support tool is great, I absolutely love having the resources and being able to find a lot of clinical examples and discussion tools like that. But when it comes down to it, not having that kind of official thing to fall back on it can be a little bit rough.”

Additional coaching and consultationsupport (15 responses). To support supervisors in effectively implementing just culture within their teams, participants recommended that organizations provide ongoing coaching and mentorship opportunities. Additionally, third-party consultants with expertise in just culture were described as offering valuable guidance, particularly in cases where internal staff resources or HRO lead bandwidth may be limited. “There are so many consulting agencies with HRO that have been contracted to do different projects, but maybe that can help with an educational program.” “I want to see my executive leadership coach the supervisors up right and then allow them to do one-on-ones and facilitate and empower the frontline staff, and it’s just a good way of transparency and communication.”

Improved leadership sponsorship (15 responses). Participants noted that leadership buy-in is crucial for the successful implementation of just culture. Facilities should actively engage and educate leadership teams on the benefits of just culture and how it aligns with broader patient safety and organizational goals. Leaders should be visible and active champions of its principles, supporting change in their daily engagements with staff. “ELT support is absolutely necessary. Why? Because they will make it important to those in their service lines. They will make it important to those supervisors and managers. If it’s not important to that ELT member, then it’s not going to be important to that manager or that supervisor.”

Improved collaboration with patient safety and human resources (6 responses). Collaborative efforts with patient safety and human resources departments were seen as instrumental in supporting just culture, emphasizing its importance, and effectively addressing issues. Coordinating with these departments specifically contributes to consistent reinforcement and expands the bandwidth of HRO leads. These departments play integral roles in supporting just culture through effective policies, procedures, and communication. “I think it would be really helpful to have common language between what human resources teaches and what is in our decision support tool.”

DISCUSSION

This study sought to collect and synthesize the experiences of leaders across a large, integrated health care system in establishing and sustaining a just culture as part of an enterprise journey to become an HRO.24 The VHA has provided enterprise-wide support (eg, training, leader coaching, and communications) for the implementation of HRO principles and practices with the goal of creating a culture of safety, which includes just culture elements. This support includes enterprise program offices, VISNs, and hospital facilities, though notably, there is variability in how HRO is implemented at the local level. The facilitators, barriers, and recommendations presented in this article are representative of the designated HRO leads at VHA hospital facilities who have direct experience with implementing and sustaining just culture. The themes presented offer specific opportunities for intervention and actionable strategies to enhance just culture initiatives, foster psychological safety and accountability, and ultimately improve the quality of care and patient outcomes.3,25

Frequently identified facilitators such as providing training and coaching, having leaders who are available and approachable, demonstrating follow-through to address identified issues, and creating venues where errors and successes can be openly discussed.26 These facilitators are aligned with enterprise HRO support strategies orchestrated by the VHA at the enterprise VISN and facility levels to support a culture of safety, continuous process improvement, and leadership commitment.

Frequently identified barriers included inadequate training, inconsistent application of just culture by middle managers vs senior leaders, a lack of accountability or corrective action when unjust corrective actions took place, time and resource constraints, and inadequate coordination across departments (eg, operational departments and human resources) and organizational levels. These factors were identified through focus groups with a limited set of HRO leads. They may reflect challenges to changing culture that may be deeply engrained in individual histories, organizational norms, and systemic practices. Improving upon these just culture initiatives requires multifaceted approaches and working through resistance to change.

VHA HRO leads identified several actionable recommendations that may be used in pursuit of a just culture. First, improvements in training involving how to apply just culture principles and, specifically, the use of the Just Culture DST were identified as an opportunity for improvement. The VHA National Center for Patient Safety developed the DST as an aid for leaders to effectively address errors in line with just culture principles, balancing individual and system accountability.27 The DST specifically addresses human error as well as risky and reckless behavior, and it clarifies the delineation between individual and organizational accountability (Table).3

Scenario-based interactive training and simulations may prove especially useful for middle managers and frontline supervisors who are closest to errors. Clear and repeatable procedures for determining courses of action for accountability in response are needed, and support for their application must be coordinated across multiple departments (eg, patient safety and human resources) to ensure consistency and fairness. Coaching and consultation are also viewed as beneficial in supporting applications. Coaching is provided to senior leaders across most facilities, but the availability of specific, role-based coaching and training is more limited for middle managers and frontline supervisors who may benefit most from hands-on support.

Lastly, sponsorship from leaders was viewed as critical to success, but follow through to ensure support flows down from the executive suite to the frontline is variable across facilities and requires consistent effort over time. This is especially challenging given the frequent turnover in leadership roles evident in the VHA and other health care systems.

Limitations

This study employed qualitative methods and sampled a relatively small subset of experienced leaders with specific roles in implementing HRO in the VHA. Thus, it should not be considered representative of the perspectives of all leaders within the VHA or other health care systems. Future studies should assess facilitators and barriers beyond the facility level, including a focus incorporating both the VISN and VHA. More broadly, qualitative methods such as those employed in this study offer great depth and nuance but have limited ability to identify system-wide trends and differences. As such, it may be beneficial to specifically look at sites that are high- or low-performing on measures of patient safety culture to identify differences that may inform implementation strategies based on organizational maturity and readiness for change.

Conclusions

Successful implementation of these recommendations will require ongoing commitment, collaboration, and a sustained effort from all stakeholders involved at multiple levels of the health care system. Monitoring and evaluating progress should be conducted regularly to ensure that recommendations lead to improvements in implementing just culture principles. This quality improvement study adds to the knowledge base on factors that impact the just culture and broader efforts to realize HRO principles and practices in health care systems. The approach of this study may serve as a model for identifying opportunities to improve HRO implementation within the VHA and other settings, especially when paired with ongoing quantitative evaluation of organizational safety culture, just culture behaviors, and patient outcomes.

Medical errors are a persistent problem and leading cause of preventable death in the United States. There is considerable momentum behind the idea that implementation of a just culture is foundational to detecting and learning from errors in pursuit of zero patient harm.1-6 Just culture is a framework that fosters an environment of trust within health care organizations, aiming to achieve fair outcomes for those involved in incidents or near misses. It emphasizes openness, accountability, and learning, prioritizing the repair of harm and systemic improvement over assigning blame.7

A just culture mindset reflects a significant shift in thinking that moves from the tendency to blame and punish others toward a focus on organizational learning and continued process improvement.8,9 This systemic shift in fundamental thinking transforms how leaders approach staff errors and how they are addressed.10 In essence, just culture reflects an ethos centered on openness, a deep appreciation of human fallibility, and shared accountability at both the individual and organizational levels.

Organizational learning and innovation are stifled in the absence of a just culture, and there is a tendency for employees to avoid disclosing their own errors as well as those of their colleagues.11 The transformation to a just culture is often slowed or disrupted by personal, systemic, and cultural barriers.12 It is imperative that all executive, service line, and frontline managers recognize and execute their distinct responsibilities while adjudicating the appropriate course of action in the aftermath of adverse events or near misses. This requires a nuanced understanding of the factors that contribute to errors at the individual and organizational levels to ensure an appropriate response.

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is orchestrating an enterprise transformation to develop into a high reliability organization (HRO). This began with a single-site test in 2016, which demonstrated successful results in patient safety culture, patient safety event reporting, and patient safety outcomes.13 In 2019, the VHA formally launched its enterprise-wide HRO journey in 18 hospital facilities, followed by successive waves of 67 and 54 facilities in 2021 and 2022, respectively. The VHA journey to transform into an HRO aligns with 3 pillars, 5 principles, and 7 values. The VHA has emphasized the importance of just culture as a foundational element of the HRO framework, specifically under the pillar of leadership. To promote leadership engagement, the VHA has employed an array of approaches that include education, leader coaching, and change management strategies. Given the diversity among VHA facilities, each with local cultures and histories, some sites have more readily implemented a just culture than others.14 A deeper exploration into potential obstacles, particularly concerning leadership engagement, could be instrumental for formulating strategies that further establish a just culture across the VHA.15

There is a paucity of empirical research regarding factors that facilitate and/or impede the implementation of a just culture in health care settings.16,17 Likert scale surveys, such as the Patient Safety Culture Module for the VHA All Employee Survey and its predecessor, the Patient Safety Culture Survey, have been used to assess culture and climate.18 However, qualitative evaluations directly assessing the lived experiences of those trying to implement a just culture provide additional depth and context that can help identify specific factors that support or impede becoming an HRO. The purpose of this study was to increase understanding of factors that influence the establishment and sustainment of a just culture and to identify specific methods for improving the implementation of just culture principles and practices aligned with HRO.

METHODS

This qualitative study explored facilitators and barriers to establishing and sustaining a just culture as experienced across a subset of VHA facilities by HRO leads or staff assigned with the primary responsibilities of supporting facility-level HRO transformation. HRO leads are assigned responsibility for supporting executive leadership in planning, coordinating, implementing, and monitoring activities to ensure effective high reliability efforts, including focused efforts to establish a robust patient safety program, a culture of safety, and a culture of continuous process improvement.

Virtual focus group discussions held via Microsoft Teams generated in-depth, diverse perspectives from participants across 16 VHA facilities. Qualitative research and evaluation methods provide an enhanced depth of understanding and allow the emergence of detailed data.19 A qualitative grounded theory approach elicits complex, multifaceted phenomena that cannot be appreciated solely by numeric data.20 Grounded theory was selected to limit preconceived notions and provide a more systematic analysis, including open, axial, and thematic coding. Such methods afford opportunities to adapt to unplanned follow-up questions and thus provide a flexible approach to generate new ideas and concepts.21 Additionally, qualitative methods help overcome the tendencies of respondents to agree rather than disagree when presented with Likert-style scales, which tend to skew responses toward the positive.22

Participants must have been assigned as an HRO lead for ≥ 6 months at the same facility. Potential participants were identified through purposive sampling, considering their leadership roles in HRO and experience with just culture implementation, the size and complexity of their facility, and geographic distribution. Invitations explaining the study and encouraging voluntary participation to participate were emailed. Of 37 HRO leads invited to participate in the study, 16 agreed to participate and attended 1 of 3 hour-long focus group sessions. One session was rescheduled due to limited attendance. Participants represented a mix of VHA sites in terms of geography, facility size, and complexity.

Focus Group Procedures

Demographic data were collected prior to sessions via an online form to better understand the participant population, including facility complexity level, length of time in HRO lead role, clinical background, and facility level just culture training. Each session was led by an experienced focus group facilitator (CV) who was not directly involved with the overall HRO implementation to establish a neutral perspective. Each session was attended by 4 to 7 participants and 2 observers who took notes. The sessions were recorded and included automated transcriptions, which were edited for accuracy.

Focus group sessions began with a brief introduction and an opportunity for participants to ask questions. Participants were then asked a series of open-ended questions to elicit responses regardingfacilitators, barriers, and leadership support needed for implementing just culture. The questions were part of a facilitator guide that included an introductory script and discussion prompts to ensure consistency across focus groups.

Facilitators were defined as factors that increase the likelihood of establishing or sustaining a just culture. Barriers were defined as factors that decrease or inhibit the likelihood of establishing or sustaining just culture. The focus group facilitator encouraged all participants to share their views and provided clarification if needed, as well as prompts and examples where appropriate, but primarily sought to elicit responses to the questions.

Institutional review board review and approval were not required for this quality improvement initiative. The project adhered to ethical standards of research, including asking participants for verbal consent and preserving their confidentiality. Participation was voluntary, and prior to the focus group sessions, participants were provided information explaining the study’s purpose, procedures, and their rights. Participant identities were kept confidential, and all data were anonymized during the analysis phase. Pseudonyms or identifiers were used during data transcription to protect participant identity. All data, including recordings and transcriptions, were stored on password-protected devices accessible only to the research team. Any identifiable information was removed during data analysis to ensure confidentiality.

Analysis

Focus group recordings were transcribed verbatim, capturing all verbal interactions and nonverbal cues that may contribute to understanding the participants' perspectives. Thematic analysis was used to analyze the qualitative data from the focus group discussions.23 The transcribed data were organized, coded, and analyzed using ATLAS.ti 23 qualitative data software to identify key themes and patterns.

Results

The themes identified include the 5 facilitators, barriers, and recommendations most frequently mentioned by HRO leads across focus group sessions. The nature of each theme is described, along with commonly mentioned examples and direct quotes from participants that illustrate our understanding of their perspectives.

Facilitators

Training and coaching (26 responses). The availability of training around the Just Culture Decision Support Tool (DST) was cited as a practical aid in guiding leaders through complex just culture decisions to ensure consistency and fairness. Additionally, an executive leadership team that served as champions for just culture principles played a vital role in promoting and sustaining the approach: “Training them on the roll-out of the decision support tool with supervisors at all levels, and education for just culture and making it part of our safety forum has helped for the last 4 months.” “Having some regular training and share-out cadences embedded within the schedule as well as dynamic directors and well-trained executive leadership team (ELT) for support has been a facilitator.”

Increased transparency (16 responses). Participants consistently highlighted the importance of leadership transparency as a key facilitator for implementing just culture. Open and honest communication from top-level executives fostered an environment of trust and accountability. Approachable and physically present leadership was seen as essential for creating a culture where employees felt comfortable reporting errors and concerns without fear of retaliation: “They’re surprisingly honest with themselves about what we can do, what we cannot do, and they set the expectations exactly at that.”

Approachable leadership (15 responses). Participants frequently mentioned the importance of having dynamic leadership spearheading the implementation of just culture and leading by example. Having a leadership team that accepts accountability and reinforces consistency in the manner that near misses or mistakes are addressed is paramount to promoting the principles of just culture and increasing psychological safety: “We do have very approachable leadership, which I know is hard if you’re trying to implement that nationwide, it’s hard to implement approachability. But I do think that people raise their concerns, and they’ll stop them in the hallway and ask them questions. So, in terms of comfort level with the executive leadership, I do think that’s high, which would promote psychological safety.”

Feedback loops and follow through (13 responses). Participants emphasized the importance of taking concrete actions to address concerns and improve processes. Regular check-ins with supervisors to discuss matters related to just culture provided a structured opportunity for addressing issues and reinforcing the importance of the approach: “One thing that we’ve really focused on is not only identifying mistakes, but [taking] ownership. We continue to track it until … it’s completed and then a process of how to communicate that back and really using closed loop communication with the staff and letting them know.”

Forums and town halls (10 responses). These platforms created feedback loops that were seen as invaluable tools for sharing near misses, celebrating successes, and promoting open dialogue. Forums and town halls cultivated a culture of continuous improvement and trust: “We’ll celebrate catches, a safety story is inside that catch. So, if we celebrate the change, people feel safer to speak up.” “Truthfully, we’ve had a great relationship since establishing our safety forums and just value open lines of communication.”

Barriers

Inadequate training (30 responses). Insufficient engagement during training—limited bandwidth and availability to attend and actively participate in training—was perceived as detrimental to creating awareness and buy-in from staff, supervisors, and leadership, thereby hindering successful integration of just culture principles. Participants also identified too many conflicting priorities from VHA leadership, which contributes to training and information fatigue among staff and supervisors. “Our biggest barrier is just so many different competing priorities going on. We have so much that we’re asking people to do.” “One hundred percent training is feeling more like a ticked box than actually yielding results, I have a very hard time getting staff engaged.”