User login

Heart failure targets African Americans

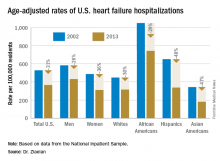

ORLANDO – The disparity in U.S. heart failure incidence continued undiminished during 2002-2013, with African Americans maintaining a steady 2.3-fold increased rate of heart failure, compared with whites, based on national levels of heart failure hospitalizations, a reasonable surrogate for incidence rates, Boback Ziaeian, MD, reported at the annual scientific meeting of the Heart Failure Society of America.

The same period also showed a substantial relative improvement in the heart failure hospitalization rates among U.S. Hispanics, compared with whites, so that, by 2013, the ethnic disparity seen in 2002 between Hispanics and whites largely disappeared, reported Dr. Ziaeian, a cardiologist at the University of California, Los Angeles. The data he analyzed also showed that Asian Americans had the lowest heart failure hospitalization rates of any racial or ethnic group throughout the 11-year period, and that the incidence of heart failure fell more sharply in women than in men during the period, based on the hospitalization numbers.

Age-adjusted heart failure hospitalizations among whites dropped by 30%, and among African Americans by a nearly identical 29%. But this maintained a greater than twofold disparity in rates between the two groups. Among whites, the rate per 100,000 fell from 448 to 315; among African Americans, it dropped from 1,048 to 741. In 2013, the rate of heart failure hospitalizations was 2.4-fold higher in African Americans, compared with whites.

Heart failure hospitalizations fell among Hispanics from 650 per 100,000 to 337 per 100,000 in 2013, a 48% drop that brought the rate among Hispanics to nearly the same as among whites. Asian Americans remained the group with the least heart failure throughout the period, falling from 343 hospitalizations per 100,000 in 2002 to 181 per 100,000 in 2013, a 47% drop.

Among women, the age-adjusted rate per 100,000 fell from 486 to 311, a 36% drop, compared with a decrease from 582 to 431 per 100,000 in men, a 26% reduction. Lower incidence in women may reflect better risk factor control during the study period, compared with men, such as a higher rate of quiting smoking and better treatment compliance, Dr. Ziaeian suggested.

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

ORLANDO – The disparity in U.S. heart failure incidence continued undiminished during 2002-2013, with African Americans maintaining a steady 2.3-fold increased rate of heart failure, compared with whites, based on national levels of heart failure hospitalizations, a reasonable surrogate for incidence rates, Boback Ziaeian, MD, reported at the annual scientific meeting of the Heart Failure Society of America.

The same period also showed a substantial relative improvement in the heart failure hospitalization rates among U.S. Hispanics, compared with whites, so that, by 2013, the ethnic disparity seen in 2002 between Hispanics and whites largely disappeared, reported Dr. Ziaeian, a cardiologist at the University of California, Los Angeles. The data he analyzed also showed that Asian Americans had the lowest heart failure hospitalization rates of any racial or ethnic group throughout the 11-year period, and that the incidence of heart failure fell more sharply in women than in men during the period, based on the hospitalization numbers.

Age-adjusted heart failure hospitalizations among whites dropped by 30%, and among African Americans by a nearly identical 29%. But this maintained a greater than twofold disparity in rates between the two groups. Among whites, the rate per 100,000 fell from 448 to 315; among African Americans, it dropped from 1,048 to 741. In 2013, the rate of heart failure hospitalizations was 2.4-fold higher in African Americans, compared with whites.

Heart failure hospitalizations fell among Hispanics from 650 per 100,000 to 337 per 100,000 in 2013, a 48% drop that brought the rate among Hispanics to nearly the same as among whites. Asian Americans remained the group with the least heart failure throughout the period, falling from 343 hospitalizations per 100,000 in 2002 to 181 per 100,000 in 2013, a 47% drop.

Among women, the age-adjusted rate per 100,000 fell from 486 to 311, a 36% drop, compared with a decrease from 582 to 431 per 100,000 in men, a 26% reduction. Lower incidence in women may reflect better risk factor control during the study period, compared with men, such as a higher rate of quiting smoking and better treatment compliance, Dr. Ziaeian suggested.

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

ORLANDO – The disparity in U.S. heart failure incidence continued undiminished during 2002-2013, with African Americans maintaining a steady 2.3-fold increased rate of heart failure, compared with whites, based on national levels of heart failure hospitalizations, a reasonable surrogate for incidence rates, Boback Ziaeian, MD, reported at the annual scientific meeting of the Heart Failure Society of America.

The same period also showed a substantial relative improvement in the heart failure hospitalization rates among U.S. Hispanics, compared with whites, so that, by 2013, the ethnic disparity seen in 2002 between Hispanics and whites largely disappeared, reported Dr. Ziaeian, a cardiologist at the University of California, Los Angeles. The data he analyzed also showed that Asian Americans had the lowest heart failure hospitalization rates of any racial or ethnic group throughout the 11-year period, and that the incidence of heart failure fell more sharply in women than in men during the period, based on the hospitalization numbers.

Age-adjusted heart failure hospitalizations among whites dropped by 30%, and among African Americans by a nearly identical 29%. But this maintained a greater than twofold disparity in rates between the two groups. Among whites, the rate per 100,000 fell from 448 to 315; among African Americans, it dropped from 1,048 to 741. In 2013, the rate of heart failure hospitalizations was 2.4-fold higher in African Americans, compared with whites.

Heart failure hospitalizations fell among Hispanics from 650 per 100,000 to 337 per 100,000 in 2013, a 48% drop that brought the rate among Hispanics to nearly the same as among whites. Asian Americans remained the group with the least heart failure throughout the period, falling from 343 hospitalizations per 100,000 in 2002 to 181 per 100,000 in 2013, a 47% drop.

Among women, the age-adjusted rate per 100,000 fell from 486 to 311, a 36% drop, compared with a decrease from 582 to 431 per 100,000 in men, a 26% reduction. Lower incidence in women may reflect better risk factor control during the study period, compared with men, such as a higher rate of quiting smoking and better treatment compliance, Dr. Ziaeian suggested.

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT THE HFSA ANNUAL SCIENTIFIC MEETING

Key clinical point:

Major finding: In 2013, age-adjusted heart failure hospitalization was 741/100,000 in African Americans and 315/100,000 in whites.

Data source: The National Inpatient Sample and U.S. Census data.

Disclosures: Dr. Ziaeian had no disclosures.

Adaptive servo ventilation cuts atrial fib burden

ORLANDO – Adaptive servo ventilation produced a significant and clinically meaningful reduction in atrial fibrillation burden in patients with heart failure and sleep apnea in results from an exploratory, prospective, randomized study with 35 patients.

Adaptive servo ventilation (ASV) “may be an effective antiarrhythmic treatment producing a significant reduction in atrial fibrillation without clear evidence of being proarrhythmogenic,” Jonathan P. Piccini, MD, said at the annual scientific meeting of the Heart Failure Society of America. “Given the potential importance of this finding further studies should validate and quantify the efficacy of ASV for reducing atrial fibrillation in patients with or without heart failure.”

“A mound of data has shown that treating sleep apnea reduced arrhythmias, but until now it’s all been observational and retrospective,” Dr. Piccini, an electrophysiologist at Duke University in Durham, N.C., said in an interview. The study he reported is “the first time” the arrhythmia effects of a sleep apnea intervention, in this case ASV, was studied in a prospective, randomized way while using implanted devices to measure the antiarrhythmic effect of the treatment.

The new finding means that additional, larger studies are now needed, he said. “If patients have sleep apnea, treating the apnea may be an incredibly important way to prevent AF or reduce its burden”

The CAT-HF (Cardiovascular Improvements With Minute Ventilation-Targeted ASV Therapy in Heart Failure) trial was originally designed to randomize 215 heart failure patients with sleep disordered breathing – and who were hospitalized for heart failure – to optimal medical therapy with or without ASV at any of 15 centers in the United States and Germany. But in August 2015, results from the SERVE-HF (Treatment of Sleep-Disordered Breathing with Predominant Central Sleep Apnea by Adaptive Servo Ventilation in Patients with Heart Failure) trial, which generally had a similar design to CAT-HF, showed an unexpected danger from ASV in patients with central sleep apnea and heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (N Engl J Med. 2015 Sept 17;373[12]:1095-105). In SERVE-HF, ASV was associated with significant increases in all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. As a result, enrollment into CAT-HF stopped prematurely with just 126 patients entered, and ASV treatment of patients already enrolled came to a halt.

The primary endpoint in the underpowered and shortened CAT-HF study, survival without cardiovascular hospitalization and with improved functional capacity measured on a 6-minute walk test, showed similar outcomes in both the ASV and control arms. But in a prespecified subgroup analysis by baseline ejection fraction, the 24 patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (19% of the CAT-HF enrollment) showed a statistically significant, 62% relative improvement in the primary endpoint linked with ASV treatment compared with similar patients who did not receive ASV, Christopher M. O’Connor, MD, professor of medicine at Duke University, reported in May 2016 at the European Heart Failure meeting in Florence.

Dr. Piccini’s report focused on a prespecified subgroup analysis of CAT-HF designed to examine the impact of ASV on arrhythmias. Assessment of the impact of ASV on atrial fibrillation was possible in 35 of the 126 patients in CAT-HF who had an implanted cardiac device (pacemaker, defibrillator, or cardiac resynchronization device) with an atrial lead, and assessment of ventricular arrhythmias occurred in 46 of the CAT-HF patients with an implanted high-voltage device (a defibrillator or resynchronization device) that allowed monitoring of ventricular arrhythmias.

For the atrial fibrillation analysis, the 35 patients averaged 60 years of age, and about 90% had a reduced ejection fraction. About two-thirds had an apnea-hypopnea index greater than 30.

The results showed that the 19 patients randomized to receive ASV had an average atrial fibrillation burden of 30% at baseline that dropped to 14% after 6 months of treatment. In contrast, the 16 patients in the control arm had a AF burden of 6% at baseline and 8% after 6 months. The between-group difference for change in AF burden was statistically significant, Dr. Piccini reported, with a burden that decreased by a relative 21% with ASV treatment and increased by a relative 31% in the control arm.

Analysis of the ventricular arrhythmia subgroup showed that ASV had no statistically significant impact for either lowering or raising ventricular tachyarrhythmias or fibrillations.

Trying to reconcile this AF benefit and lack of ventricular arrhythmia harm from ASV in CAT-HF with the excess in cardiovascular deaths seen with ASV in SERVE-HF, Dr. Piccini speculated that some of the SERVE-HF deaths may not have been related to arrhythmia.

“Sudden cardiac death adjudication is profoundly difficult, and does not always equal ventricular arrhythmia,” he said. “We need to consider that some of the adverse events in patients with severe central sleep apnea and low left ventricular ejection fraction [enrolled in SERVE-HF] may have been due to causes other than arrhythmias. The CAT-HF results should motivate investigations of alternative mechanisms of death in SERVE-HF.”

The CAT-HF trial was funded by ResMed, a company that markets adaptive servo ventilation equipment. Dr. Piccini has received research support from ResMed and from Janssen, Gilead, St. Jude, Spectranetics, and he has been a consultant to Janssen, Spectranetics, Medtronic, GSK and BMS-Pfizer. Dr. O’Connor has been a consultant to ResMed and to several other drug and device companies.

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

A small prespecified sub-group of patients in the CAT-HF (Cardiovascuar improvements with minute ventilation-targeted ASV therapy in heart failure) trial randomized to adaptive servo ventilation (ASV) showed a 21% relative reduction in atrial fibrillation burden as compared to the control arm which had only 31% relative reduction. While the CAT-HF study was discontinued following results of SERVE-HF trial, this subgroup analysis included 35 patients (19 ASV arm; 16 control arm), the majority of whom had a reduced ejection fraction. This report poses interesting questions about effects of ASV on atrial fibrillation burden in those with reduced EF given the finding that central sleep apnea and Cheyne-Stokes respiration are shown to be associated with incident atrial fibrillation in older men (May et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2016).

A small prespecified sub-group of patients in the CAT-HF (Cardiovascuar improvements with minute ventilation-targeted ASV therapy in heart failure) trial randomized to adaptive servo ventilation (ASV) showed a 21% relative reduction in atrial fibrillation burden as compared to the control arm which had only 31% relative reduction. While the CAT-HF study was discontinued following results of SERVE-HF trial, this subgroup analysis included 35 patients (19 ASV arm; 16 control arm), the majority of whom had a reduced ejection fraction. This report poses interesting questions about effects of ASV on atrial fibrillation burden in those with reduced EF given the finding that central sleep apnea and Cheyne-Stokes respiration are shown to be associated with incident atrial fibrillation in older men (May et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2016).

A small prespecified sub-group of patients in the CAT-HF (Cardiovascuar improvements with minute ventilation-targeted ASV therapy in heart failure) trial randomized to adaptive servo ventilation (ASV) showed a 21% relative reduction in atrial fibrillation burden as compared to the control arm which had only 31% relative reduction. While the CAT-HF study was discontinued following results of SERVE-HF trial, this subgroup analysis included 35 patients (19 ASV arm; 16 control arm), the majority of whom had a reduced ejection fraction. This report poses interesting questions about effects of ASV on atrial fibrillation burden in those with reduced EF given the finding that central sleep apnea and Cheyne-Stokes respiration are shown to be associated with incident atrial fibrillation in older men (May et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2016).

ORLANDO – Adaptive servo ventilation produced a significant and clinically meaningful reduction in atrial fibrillation burden in patients with heart failure and sleep apnea in results from an exploratory, prospective, randomized study with 35 patients.

Adaptive servo ventilation (ASV) “may be an effective antiarrhythmic treatment producing a significant reduction in atrial fibrillation without clear evidence of being proarrhythmogenic,” Jonathan P. Piccini, MD, said at the annual scientific meeting of the Heart Failure Society of America. “Given the potential importance of this finding further studies should validate and quantify the efficacy of ASV for reducing atrial fibrillation in patients with or without heart failure.”

“A mound of data has shown that treating sleep apnea reduced arrhythmias, but until now it’s all been observational and retrospective,” Dr. Piccini, an electrophysiologist at Duke University in Durham, N.C., said in an interview. The study he reported is “the first time” the arrhythmia effects of a sleep apnea intervention, in this case ASV, was studied in a prospective, randomized way while using implanted devices to measure the antiarrhythmic effect of the treatment.

The new finding means that additional, larger studies are now needed, he said. “If patients have sleep apnea, treating the apnea may be an incredibly important way to prevent AF or reduce its burden”

The CAT-HF (Cardiovascular Improvements With Minute Ventilation-Targeted ASV Therapy in Heart Failure) trial was originally designed to randomize 215 heart failure patients with sleep disordered breathing – and who were hospitalized for heart failure – to optimal medical therapy with or without ASV at any of 15 centers in the United States and Germany. But in August 2015, results from the SERVE-HF (Treatment of Sleep-Disordered Breathing with Predominant Central Sleep Apnea by Adaptive Servo Ventilation in Patients with Heart Failure) trial, which generally had a similar design to CAT-HF, showed an unexpected danger from ASV in patients with central sleep apnea and heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (N Engl J Med. 2015 Sept 17;373[12]:1095-105). In SERVE-HF, ASV was associated with significant increases in all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. As a result, enrollment into CAT-HF stopped prematurely with just 126 patients entered, and ASV treatment of patients already enrolled came to a halt.

The primary endpoint in the underpowered and shortened CAT-HF study, survival without cardiovascular hospitalization and with improved functional capacity measured on a 6-minute walk test, showed similar outcomes in both the ASV and control arms. But in a prespecified subgroup analysis by baseline ejection fraction, the 24 patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (19% of the CAT-HF enrollment) showed a statistically significant, 62% relative improvement in the primary endpoint linked with ASV treatment compared with similar patients who did not receive ASV, Christopher M. O’Connor, MD, professor of medicine at Duke University, reported in May 2016 at the European Heart Failure meeting in Florence.

Dr. Piccini’s report focused on a prespecified subgroup analysis of CAT-HF designed to examine the impact of ASV on arrhythmias. Assessment of the impact of ASV on atrial fibrillation was possible in 35 of the 126 patients in CAT-HF who had an implanted cardiac device (pacemaker, defibrillator, or cardiac resynchronization device) with an atrial lead, and assessment of ventricular arrhythmias occurred in 46 of the CAT-HF patients with an implanted high-voltage device (a defibrillator or resynchronization device) that allowed monitoring of ventricular arrhythmias.

For the atrial fibrillation analysis, the 35 patients averaged 60 years of age, and about 90% had a reduced ejection fraction. About two-thirds had an apnea-hypopnea index greater than 30.

The results showed that the 19 patients randomized to receive ASV had an average atrial fibrillation burden of 30% at baseline that dropped to 14% after 6 months of treatment. In contrast, the 16 patients in the control arm had a AF burden of 6% at baseline and 8% after 6 months. The between-group difference for change in AF burden was statistically significant, Dr. Piccini reported, with a burden that decreased by a relative 21% with ASV treatment and increased by a relative 31% in the control arm.

Analysis of the ventricular arrhythmia subgroup showed that ASV had no statistically significant impact for either lowering or raising ventricular tachyarrhythmias or fibrillations.

Trying to reconcile this AF benefit and lack of ventricular arrhythmia harm from ASV in CAT-HF with the excess in cardiovascular deaths seen with ASV in SERVE-HF, Dr. Piccini speculated that some of the SERVE-HF deaths may not have been related to arrhythmia.

“Sudden cardiac death adjudication is profoundly difficult, and does not always equal ventricular arrhythmia,” he said. “We need to consider that some of the adverse events in patients with severe central sleep apnea and low left ventricular ejection fraction [enrolled in SERVE-HF] may have been due to causes other than arrhythmias. The CAT-HF results should motivate investigations of alternative mechanisms of death in SERVE-HF.”

The CAT-HF trial was funded by ResMed, a company that markets adaptive servo ventilation equipment. Dr. Piccini has received research support from ResMed and from Janssen, Gilead, St. Jude, Spectranetics, and he has been a consultant to Janssen, Spectranetics, Medtronic, GSK and BMS-Pfizer. Dr. O’Connor has been a consultant to ResMed and to several other drug and device companies.

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

ORLANDO – Adaptive servo ventilation produced a significant and clinically meaningful reduction in atrial fibrillation burden in patients with heart failure and sleep apnea in results from an exploratory, prospective, randomized study with 35 patients.

Adaptive servo ventilation (ASV) “may be an effective antiarrhythmic treatment producing a significant reduction in atrial fibrillation without clear evidence of being proarrhythmogenic,” Jonathan P. Piccini, MD, said at the annual scientific meeting of the Heart Failure Society of America. “Given the potential importance of this finding further studies should validate and quantify the efficacy of ASV for reducing atrial fibrillation in patients with or without heart failure.”

“A mound of data has shown that treating sleep apnea reduced arrhythmias, but until now it’s all been observational and retrospective,” Dr. Piccini, an electrophysiologist at Duke University in Durham, N.C., said in an interview. The study he reported is “the first time” the arrhythmia effects of a sleep apnea intervention, in this case ASV, was studied in a prospective, randomized way while using implanted devices to measure the antiarrhythmic effect of the treatment.

The new finding means that additional, larger studies are now needed, he said. “If patients have sleep apnea, treating the apnea may be an incredibly important way to prevent AF or reduce its burden”

The CAT-HF (Cardiovascular Improvements With Minute Ventilation-Targeted ASV Therapy in Heart Failure) trial was originally designed to randomize 215 heart failure patients with sleep disordered breathing – and who were hospitalized for heart failure – to optimal medical therapy with or without ASV at any of 15 centers in the United States and Germany. But in August 2015, results from the SERVE-HF (Treatment of Sleep-Disordered Breathing with Predominant Central Sleep Apnea by Adaptive Servo Ventilation in Patients with Heart Failure) trial, which generally had a similar design to CAT-HF, showed an unexpected danger from ASV in patients with central sleep apnea and heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (N Engl J Med. 2015 Sept 17;373[12]:1095-105). In SERVE-HF, ASV was associated with significant increases in all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. As a result, enrollment into CAT-HF stopped prematurely with just 126 patients entered, and ASV treatment of patients already enrolled came to a halt.

The primary endpoint in the underpowered and shortened CAT-HF study, survival without cardiovascular hospitalization and with improved functional capacity measured on a 6-minute walk test, showed similar outcomes in both the ASV and control arms. But in a prespecified subgroup analysis by baseline ejection fraction, the 24 patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (19% of the CAT-HF enrollment) showed a statistically significant, 62% relative improvement in the primary endpoint linked with ASV treatment compared with similar patients who did not receive ASV, Christopher M. O’Connor, MD, professor of medicine at Duke University, reported in May 2016 at the European Heart Failure meeting in Florence.

Dr. Piccini’s report focused on a prespecified subgroup analysis of CAT-HF designed to examine the impact of ASV on arrhythmias. Assessment of the impact of ASV on atrial fibrillation was possible in 35 of the 126 patients in CAT-HF who had an implanted cardiac device (pacemaker, defibrillator, or cardiac resynchronization device) with an atrial lead, and assessment of ventricular arrhythmias occurred in 46 of the CAT-HF patients with an implanted high-voltage device (a defibrillator or resynchronization device) that allowed monitoring of ventricular arrhythmias.

For the atrial fibrillation analysis, the 35 patients averaged 60 years of age, and about 90% had a reduced ejection fraction. About two-thirds had an apnea-hypopnea index greater than 30.

The results showed that the 19 patients randomized to receive ASV had an average atrial fibrillation burden of 30% at baseline that dropped to 14% after 6 months of treatment. In contrast, the 16 patients in the control arm had a AF burden of 6% at baseline and 8% after 6 months. The between-group difference for change in AF burden was statistically significant, Dr. Piccini reported, with a burden that decreased by a relative 21% with ASV treatment and increased by a relative 31% in the control arm.

Analysis of the ventricular arrhythmia subgroup showed that ASV had no statistically significant impact for either lowering or raising ventricular tachyarrhythmias or fibrillations.

Trying to reconcile this AF benefit and lack of ventricular arrhythmia harm from ASV in CAT-HF with the excess in cardiovascular deaths seen with ASV in SERVE-HF, Dr. Piccini speculated that some of the SERVE-HF deaths may not have been related to arrhythmia.

“Sudden cardiac death adjudication is profoundly difficult, and does not always equal ventricular arrhythmia,” he said. “We need to consider that some of the adverse events in patients with severe central sleep apnea and low left ventricular ejection fraction [enrolled in SERVE-HF] may have been due to causes other than arrhythmias. The CAT-HF results should motivate investigations of alternative mechanisms of death in SERVE-HF.”

The CAT-HF trial was funded by ResMed, a company that markets adaptive servo ventilation equipment. Dr. Piccini has received research support from ResMed and from Janssen, Gilead, St. Jude, Spectranetics, and he has been a consultant to Janssen, Spectranetics, Medtronic, GSK and BMS-Pfizer. Dr. O’Connor has been a consultant to ResMed and to several other drug and device companies.

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

Key clinical point:

Major finding: After 6 months, ASV produced a relative 21% drop in atrial fibrillation burden, compared with increased burden in control patients.

Data source: CAT-HF, a multicenter randomized trial that enrolled 126 heart failure patients with sleep apnea.

Disclosures: The CAT-HF trial was funded by ResMed, a company that markets adaptive servo ventilation equipment. Dr. Piccini has received research support and/or consultant fees from ResMed, Janssen, Gilead, St. Jude, Spectranetics, Medtronic, GSK and BMS-Pfizer.

Advanced heart failure symptoms linked to mortality

ORLANDO – Advanced heart failure patients who are hospitalized for heart failure and have a higher symptom burden at discharge have a significantly increased rate of death or rehospitalization over the next 6 months, based on an analysis of 393 patients enrolled in a heart failure trial.

The strong link between severe symptom burden and poor near-term outcomes persisted despite adjustment for various markers of heart failure severity, suggesting that treatment aimed at reducing symptoms may be able to reduce mortality or heart failure hospitalization in advanced heart failure patients, Ellen K. Hummel, MD, said at the annual scientific meeting of the Heart Failure Society of America.

In her analysis, a severe symptom burden at the time of hospital discharge linked with an adjusted 2.9-fold increased mortality rate and a 2.5-fold increased rate of days dead or hospitalized during the next 6 months, said Dr. Hummel, a geriatric and palliative care specialist at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. These elevated rate ratios for patients with severe symptoms at hospital discharge were in comparison to the ratios for advanced heart failure patients in the study with no symptoms at discharge.

Three symptoms contributed to the symptom score she used in her analysis: fatigue, scored on a scale of 0-3; dyspnea, also scored 0-3; and gastrointestinal distress, scored as 0-2, creating a maximum score of 8. Her analysis categorized mild as a total score of 1-4 and severe as 5 or greater. In the study population she used for her analysis, patients enrolled in the multicenter ESCAPE (Evaluation Study of Congestive Heart Failure and Pulmonary Artery Catheterization Effectiveness) trial, 111 of the 393 evaluable patients (28%) had none of these symptoms, 239 (61%) had mild symptoms, and 43 (11%) had severe symptoms. Scoring was done by patients based on their subjective self-assessment at the time of hospital discharge.

The absolute, observed 6-month mortality rates were roughly 45% among patients with severe symptoms, about 17% in patients with mild symptoms, and about 12% in those with no symptoms.

The primary purpose of ESCAPE was to assess the impact that routine collection of data from a pulmonary artery catheter during hospitalization has on outcomes; the results showed no significant link between improved outcomes and getting these data (JAMA. 2005 Oct 5;294[13]:1625-33). The study ran during 2000-2003 at 26 centers in the United States and Canada. Of the 433 advanced heart failure patients enrolled in ESCAPE, 393 had complete records to allow the current analysis.

The adjustments that Dr. Hummel made in the proportional hazard analysis took into account New York Heart Association class, and severity of disease at the time of hospital discharge measured by the ESCAPE Discharge Risk Score. This score takes into account age, 6-minute walk distance, blood urea nitrogen, brain natriuretic peptide levels, blood pressure, selected drug treatments, sodium level, and history of cardiopulmonary resuscitation or mechanical ventilation.

Dr. Hummel had no relevant financial disclosures.

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

ORLANDO – Advanced heart failure patients who are hospitalized for heart failure and have a higher symptom burden at discharge have a significantly increased rate of death or rehospitalization over the next 6 months, based on an analysis of 393 patients enrolled in a heart failure trial.

The strong link between severe symptom burden and poor near-term outcomes persisted despite adjustment for various markers of heart failure severity, suggesting that treatment aimed at reducing symptoms may be able to reduce mortality or heart failure hospitalization in advanced heart failure patients, Ellen K. Hummel, MD, said at the annual scientific meeting of the Heart Failure Society of America.

In her analysis, a severe symptom burden at the time of hospital discharge linked with an adjusted 2.9-fold increased mortality rate and a 2.5-fold increased rate of days dead or hospitalized during the next 6 months, said Dr. Hummel, a geriatric and palliative care specialist at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. These elevated rate ratios for patients with severe symptoms at hospital discharge were in comparison to the ratios for advanced heart failure patients in the study with no symptoms at discharge.

Three symptoms contributed to the symptom score she used in her analysis: fatigue, scored on a scale of 0-3; dyspnea, also scored 0-3; and gastrointestinal distress, scored as 0-2, creating a maximum score of 8. Her analysis categorized mild as a total score of 1-4 and severe as 5 or greater. In the study population she used for her analysis, patients enrolled in the multicenter ESCAPE (Evaluation Study of Congestive Heart Failure and Pulmonary Artery Catheterization Effectiveness) trial, 111 of the 393 evaluable patients (28%) had none of these symptoms, 239 (61%) had mild symptoms, and 43 (11%) had severe symptoms. Scoring was done by patients based on their subjective self-assessment at the time of hospital discharge.

The absolute, observed 6-month mortality rates were roughly 45% among patients with severe symptoms, about 17% in patients with mild symptoms, and about 12% in those with no symptoms.

The primary purpose of ESCAPE was to assess the impact that routine collection of data from a pulmonary artery catheter during hospitalization has on outcomes; the results showed no significant link between improved outcomes and getting these data (JAMA. 2005 Oct 5;294[13]:1625-33). The study ran during 2000-2003 at 26 centers in the United States and Canada. Of the 433 advanced heart failure patients enrolled in ESCAPE, 393 had complete records to allow the current analysis.

The adjustments that Dr. Hummel made in the proportional hazard analysis took into account New York Heart Association class, and severity of disease at the time of hospital discharge measured by the ESCAPE Discharge Risk Score. This score takes into account age, 6-minute walk distance, blood urea nitrogen, brain natriuretic peptide levels, blood pressure, selected drug treatments, sodium level, and history of cardiopulmonary resuscitation or mechanical ventilation.

Dr. Hummel had no relevant financial disclosures.

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

ORLANDO – Advanced heart failure patients who are hospitalized for heart failure and have a higher symptom burden at discharge have a significantly increased rate of death or rehospitalization over the next 6 months, based on an analysis of 393 patients enrolled in a heart failure trial.

The strong link between severe symptom burden and poor near-term outcomes persisted despite adjustment for various markers of heart failure severity, suggesting that treatment aimed at reducing symptoms may be able to reduce mortality or heart failure hospitalization in advanced heart failure patients, Ellen K. Hummel, MD, said at the annual scientific meeting of the Heart Failure Society of America.

In her analysis, a severe symptom burden at the time of hospital discharge linked with an adjusted 2.9-fold increased mortality rate and a 2.5-fold increased rate of days dead or hospitalized during the next 6 months, said Dr. Hummel, a geriatric and palliative care specialist at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. These elevated rate ratios for patients with severe symptoms at hospital discharge were in comparison to the ratios for advanced heart failure patients in the study with no symptoms at discharge.

Three symptoms contributed to the symptom score she used in her analysis: fatigue, scored on a scale of 0-3; dyspnea, also scored 0-3; and gastrointestinal distress, scored as 0-2, creating a maximum score of 8. Her analysis categorized mild as a total score of 1-4 and severe as 5 or greater. In the study population she used for her analysis, patients enrolled in the multicenter ESCAPE (Evaluation Study of Congestive Heart Failure and Pulmonary Artery Catheterization Effectiveness) trial, 111 of the 393 evaluable patients (28%) had none of these symptoms, 239 (61%) had mild symptoms, and 43 (11%) had severe symptoms. Scoring was done by patients based on their subjective self-assessment at the time of hospital discharge.

The absolute, observed 6-month mortality rates were roughly 45% among patients with severe symptoms, about 17% in patients with mild symptoms, and about 12% in those with no symptoms.

The primary purpose of ESCAPE was to assess the impact that routine collection of data from a pulmonary artery catheter during hospitalization has on outcomes; the results showed no significant link between improved outcomes and getting these data (JAMA. 2005 Oct 5;294[13]:1625-33). The study ran during 2000-2003 at 26 centers in the United States and Canada. Of the 433 advanced heart failure patients enrolled in ESCAPE, 393 had complete records to allow the current analysis.

The adjustments that Dr. Hummel made in the proportional hazard analysis took into account New York Heart Association class, and severity of disease at the time of hospital discharge measured by the ESCAPE Discharge Risk Score. This score takes into account age, 6-minute walk distance, blood urea nitrogen, brain natriuretic peptide levels, blood pressure, selected drug treatments, sodium level, and history of cardiopulmonary resuscitation or mechanical ventilation.

Dr. Hummel had no relevant financial disclosures.

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT THE HFSA ANNUAL SCIENTIFIC MEETING

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Patients with severe symptoms at discharge had a 2.9-fold increased rate of death, compared with those with no symptoms.

Data source: A post hoc analysis of data collected from 393 patients enrolled in the ESCAPE trial.

Disclosures: Dr. Hummel had no relevant financial disclosures.

TOPCAT, a third time around

Shakespeare, in Romeo and Juliet, refers to the proverb, “A cat has nine lives. For three he plays, for three he strays, and for the last he stays.”

TOPCAT is back again, having randomized its first patient with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) almost 10 years ago for its treatment with spironolactone (SPIRO), a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist.

The first report of the results of TOPCAT in 2014 indicated that there was no benefit associate with SPIRO therapy tested in the 3,445 patients randomized in 244 sites around the world (N Engl J Med. 2014 Apr 10;370[15]:1383-92). A subsequent analysis of data carried out in 2015 reported a striking regional difference in the outcome of patients randomized in the 1,767 patients in the Americas, compared with the 1,678 randomized in Russia and Georgia (Circulation. 2015 Jan 6;131[1]:34-42). In the Americas, there was an 18% decrease in the primary event of death and heart failure rehospitalization (3.6% in the SPIRO vs. 4.9% in the placebo; hazard ratio, 0.82; P = .026). There was essentially no difference in the groups randomized in Russia and Georgia, which had a 1.6% placebo event rate.

And now in 2016, at the recent meeting of the Heart Failure Society of America, we were informed that there was no detectable level of blood canrenone, a metabolite of SPIRO, in 30% of the 66 randomized patients in Russia and Georgia, compared with 3% of the patients randomized in the Americas (Cardiology News. Oct 2016. p 8). These data tend to confirm that the patients randomized in Russia and Georgia were either undertreated or not treated. In fact, after examination of the baseline characteristics of the two groups it is possible that many of the patients may not have had heart failure at all.

So what are we left with? One thing that is clear is that the management of TOPCAT was flawed and constitutes an example of how not to run an international clinical trial. Can we make any conclusion about the benefit of SPIRO? TOPCAT initially was powered for over 3,515 patients and 630 events in order to achieve a 85% benefit. The current analysis has now narrowed the population down to 1,787 patients with 522 events with an 18% decrease (P = .02) in the primary end point. During the mean follow-up of 3.3 years there was a placebo mortality of 4.9%, which is impressive in the setting of concomitant beta-blocker and renin angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor therapy. The only significant adverse observation was a threefold occurrence in hyperkalemia (potassium greater than 5.5 mmols/L) in the 25.2% in the Americas group treated with SPIRO, compared with the Russian-Georgian patients

Unfortunately the answer is not entirely clear. We all know who HFpEF patients are when they walk into the clinic but identifying them for a clinical trial has been difficult if not impossible. As for me, I will choose to treat their hypertension aggressively (not an easy task) and prevent or suppress their arrhythmias. In that project I will use beta-blockers and SPIRO to prevent their next heart failure episode and hope for the best.

Dr. Goldstein, medical editor of Cardiology News, is professor of medicine at Wayne State University and division head emeritus of cardiovascular medicine at Henry Ford Hospital, both in Detroit. He is on data safety monitoring committees for the National Institutes of Health and several pharmaceutical companies.

Shakespeare, in Romeo and Juliet, refers to the proverb, “A cat has nine lives. For three he plays, for three he strays, and for the last he stays.”

TOPCAT is back again, having randomized its first patient with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) almost 10 years ago for its treatment with spironolactone (SPIRO), a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist.

The first report of the results of TOPCAT in 2014 indicated that there was no benefit associate with SPIRO therapy tested in the 3,445 patients randomized in 244 sites around the world (N Engl J Med. 2014 Apr 10;370[15]:1383-92). A subsequent analysis of data carried out in 2015 reported a striking regional difference in the outcome of patients randomized in the 1,767 patients in the Americas, compared with the 1,678 randomized in Russia and Georgia (Circulation. 2015 Jan 6;131[1]:34-42). In the Americas, there was an 18% decrease in the primary event of death and heart failure rehospitalization (3.6% in the SPIRO vs. 4.9% in the placebo; hazard ratio, 0.82; P = .026). There was essentially no difference in the groups randomized in Russia and Georgia, which had a 1.6% placebo event rate.

And now in 2016, at the recent meeting of the Heart Failure Society of America, we were informed that there was no detectable level of blood canrenone, a metabolite of SPIRO, in 30% of the 66 randomized patients in Russia and Georgia, compared with 3% of the patients randomized in the Americas (Cardiology News. Oct 2016. p 8). These data tend to confirm that the patients randomized in Russia and Georgia were either undertreated or not treated. In fact, after examination of the baseline characteristics of the two groups it is possible that many of the patients may not have had heart failure at all.

So what are we left with? One thing that is clear is that the management of TOPCAT was flawed and constitutes an example of how not to run an international clinical trial. Can we make any conclusion about the benefit of SPIRO? TOPCAT initially was powered for over 3,515 patients and 630 events in order to achieve a 85% benefit. The current analysis has now narrowed the population down to 1,787 patients with 522 events with an 18% decrease (P = .02) in the primary end point. During the mean follow-up of 3.3 years there was a placebo mortality of 4.9%, which is impressive in the setting of concomitant beta-blocker and renin angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor therapy. The only significant adverse observation was a threefold occurrence in hyperkalemia (potassium greater than 5.5 mmols/L) in the 25.2% in the Americas group treated with SPIRO, compared with the Russian-Georgian patients

Unfortunately the answer is not entirely clear. We all know who HFpEF patients are when they walk into the clinic but identifying them for a clinical trial has been difficult if not impossible. As for me, I will choose to treat their hypertension aggressively (not an easy task) and prevent or suppress their arrhythmias. In that project I will use beta-blockers and SPIRO to prevent their next heart failure episode and hope for the best.

Dr. Goldstein, medical editor of Cardiology News, is professor of medicine at Wayne State University and division head emeritus of cardiovascular medicine at Henry Ford Hospital, both in Detroit. He is on data safety monitoring committees for the National Institutes of Health and several pharmaceutical companies.

Shakespeare, in Romeo and Juliet, refers to the proverb, “A cat has nine lives. For three he plays, for three he strays, and for the last he stays.”

TOPCAT is back again, having randomized its first patient with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) almost 10 years ago for its treatment with spironolactone (SPIRO), a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist.

The first report of the results of TOPCAT in 2014 indicated that there was no benefit associate with SPIRO therapy tested in the 3,445 patients randomized in 244 sites around the world (N Engl J Med. 2014 Apr 10;370[15]:1383-92). A subsequent analysis of data carried out in 2015 reported a striking regional difference in the outcome of patients randomized in the 1,767 patients in the Americas, compared with the 1,678 randomized in Russia and Georgia (Circulation. 2015 Jan 6;131[1]:34-42). In the Americas, there was an 18% decrease in the primary event of death and heart failure rehospitalization (3.6% in the SPIRO vs. 4.9% in the placebo; hazard ratio, 0.82; P = .026). There was essentially no difference in the groups randomized in Russia and Georgia, which had a 1.6% placebo event rate.

And now in 2016, at the recent meeting of the Heart Failure Society of America, we were informed that there was no detectable level of blood canrenone, a metabolite of SPIRO, in 30% of the 66 randomized patients in Russia and Georgia, compared with 3% of the patients randomized in the Americas (Cardiology News. Oct 2016. p 8). These data tend to confirm that the patients randomized in Russia and Georgia were either undertreated or not treated. In fact, after examination of the baseline characteristics of the two groups it is possible that many of the patients may not have had heart failure at all.

So what are we left with? One thing that is clear is that the management of TOPCAT was flawed and constitutes an example of how not to run an international clinical trial. Can we make any conclusion about the benefit of SPIRO? TOPCAT initially was powered for over 3,515 patients and 630 events in order to achieve a 85% benefit. The current analysis has now narrowed the population down to 1,787 patients with 522 events with an 18% decrease (P = .02) in the primary end point. During the mean follow-up of 3.3 years there was a placebo mortality of 4.9%, which is impressive in the setting of concomitant beta-blocker and renin angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor therapy. The only significant adverse observation was a threefold occurrence in hyperkalemia (potassium greater than 5.5 mmols/L) in the 25.2% in the Americas group treated with SPIRO, compared with the Russian-Georgian patients

Unfortunately the answer is not entirely clear. We all know who HFpEF patients are when they walk into the clinic but identifying them for a clinical trial has been difficult if not impossible. As for me, I will choose to treat their hypertension aggressively (not an easy task) and prevent or suppress their arrhythmias. In that project I will use beta-blockers and SPIRO to prevent their next heart failure episode and hope for the best.

Dr. Goldstein, medical editor of Cardiology News, is professor of medicine at Wayne State University and division head emeritus of cardiovascular medicine at Henry Ford Hospital, both in Detroit. He is on data safety monitoring committees for the National Institutes of Health and several pharmaceutical companies.

Beta-blockers curb death risk in patients with primary prevention ICD

ROME – Beta-blocker therapy reduces the risks of all-cause mortality as well as cardiac death in patients with a left ventricular ejection fraction below 35% who get an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator for primary prevention, Laurent Fauchier, MD, PhD, reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

Some physicians have recently urged reconsideration of current guidelines recommending routine use of beta-blockers for prevention of cardiovascular events in certain groups of patients with coronary artery disease, including those with chronic heart failure who have received an ICD for primary prevention of sudden death. And indeed it’s true that the now–relatively old randomized trials of ICDs for primary prevention in patients with chronic heart failure don’t provide any real evidence that beta-blockers reduce mortality in this setting. In fact, the guideline recommendation for beta-blockade has been based upon expert opinion. This was the impetus for Dr. Fauchier and coinvestigators to conduct a large retrospective observational study in a contemporary cohort of heart failure patients who received an ICD for primary prevention during a recent 10-year period at the 12 largest centers in France.

Fifteen percent of the 3,975 French ICD recipients did not receive a beta-blocker. They differed from those who did in that they were on average 2 years older, had an absolute 5% lower ejection fraction, and were more likely to also receive cardiac resynchronization therapy. Propensity score matching based on these and 19 other baseline characteristics enabled investigators to assemble a cohort of 541 closely matched patient pairs, explained Dr. Fauchier, professor of cardiology at Francois Rabelais University in Tours, France.

During a mean follow-up of 3.2 years, the risk of all-cause mortality in ICD recipients not on a beta-blocker was 34% higher than in those who were. Moreover, their risk of cardiac death was 50% greater.

In contrast, beta-blocker therapy had no effect on the risks of sudden death or of appropriate or inappropriate shocks.

The finding that beta-blocker therapy doesn’t prevent sudden death in patients with an ICD for primary prevention has not previously been reported. However, it makes sense. The device prevents such events so effectively that a beta-blocker adds nothing further in that regard, according to Dr. Fauchier.

“Beta-blockers should continue to be used widely, as currently recommended, for heart failure in the specific setting of patients with prophylactic ICD implantation. You do not have the benefit for prevention of sudden death, but you still have all the benefit from preventing cardiac death,” the electrophysiologist concluded.

This study was supported by French governmental research grants. Dr. Fauchier reported serving as a consultant to Bayer, Pfizer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Medtronic, and Novartis.

ROME – Beta-blocker therapy reduces the risks of all-cause mortality as well as cardiac death in patients with a left ventricular ejection fraction below 35% who get an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator for primary prevention, Laurent Fauchier, MD, PhD, reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

Some physicians have recently urged reconsideration of current guidelines recommending routine use of beta-blockers for prevention of cardiovascular events in certain groups of patients with coronary artery disease, including those with chronic heart failure who have received an ICD for primary prevention of sudden death. And indeed it’s true that the now–relatively old randomized trials of ICDs for primary prevention in patients with chronic heart failure don’t provide any real evidence that beta-blockers reduce mortality in this setting. In fact, the guideline recommendation for beta-blockade has been based upon expert opinion. This was the impetus for Dr. Fauchier and coinvestigators to conduct a large retrospective observational study in a contemporary cohort of heart failure patients who received an ICD for primary prevention during a recent 10-year period at the 12 largest centers in France.

Fifteen percent of the 3,975 French ICD recipients did not receive a beta-blocker. They differed from those who did in that they were on average 2 years older, had an absolute 5% lower ejection fraction, and were more likely to also receive cardiac resynchronization therapy. Propensity score matching based on these and 19 other baseline characteristics enabled investigators to assemble a cohort of 541 closely matched patient pairs, explained Dr. Fauchier, professor of cardiology at Francois Rabelais University in Tours, France.

During a mean follow-up of 3.2 years, the risk of all-cause mortality in ICD recipients not on a beta-blocker was 34% higher than in those who were. Moreover, their risk of cardiac death was 50% greater.

In contrast, beta-blocker therapy had no effect on the risks of sudden death or of appropriate or inappropriate shocks.

The finding that beta-blocker therapy doesn’t prevent sudden death in patients with an ICD for primary prevention has not previously been reported. However, it makes sense. The device prevents such events so effectively that a beta-blocker adds nothing further in that regard, according to Dr. Fauchier.

“Beta-blockers should continue to be used widely, as currently recommended, for heart failure in the specific setting of patients with prophylactic ICD implantation. You do not have the benefit for prevention of sudden death, but you still have all the benefit from preventing cardiac death,” the electrophysiologist concluded.

This study was supported by French governmental research grants. Dr. Fauchier reported serving as a consultant to Bayer, Pfizer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Medtronic, and Novartis.

ROME – Beta-blocker therapy reduces the risks of all-cause mortality as well as cardiac death in patients with a left ventricular ejection fraction below 35% who get an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator for primary prevention, Laurent Fauchier, MD, PhD, reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

Some physicians have recently urged reconsideration of current guidelines recommending routine use of beta-blockers for prevention of cardiovascular events in certain groups of patients with coronary artery disease, including those with chronic heart failure who have received an ICD for primary prevention of sudden death. And indeed it’s true that the now–relatively old randomized trials of ICDs for primary prevention in patients with chronic heart failure don’t provide any real evidence that beta-blockers reduce mortality in this setting. In fact, the guideline recommendation for beta-blockade has been based upon expert opinion. This was the impetus for Dr. Fauchier and coinvestigators to conduct a large retrospective observational study in a contemporary cohort of heart failure patients who received an ICD for primary prevention during a recent 10-year period at the 12 largest centers in France.

Fifteen percent of the 3,975 French ICD recipients did not receive a beta-blocker. They differed from those who did in that they were on average 2 years older, had an absolute 5% lower ejection fraction, and were more likely to also receive cardiac resynchronization therapy. Propensity score matching based on these and 19 other baseline characteristics enabled investigators to assemble a cohort of 541 closely matched patient pairs, explained Dr. Fauchier, professor of cardiology at Francois Rabelais University in Tours, France.

During a mean follow-up of 3.2 years, the risk of all-cause mortality in ICD recipients not on a beta-blocker was 34% higher than in those who were. Moreover, their risk of cardiac death was 50% greater.

In contrast, beta-blocker therapy had no effect on the risks of sudden death or of appropriate or inappropriate shocks.

The finding that beta-blocker therapy doesn’t prevent sudden death in patients with an ICD for primary prevention has not previously been reported. However, it makes sense. The device prevents such events so effectively that a beta-blocker adds nothing further in that regard, according to Dr. Fauchier.

“Beta-blockers should continue to be used widely, as currently recommended, for heart failure in the specific setting of patients with prophylactic ICD implantation. You do not have the benefit for prevention of sudden death, but you still have all the benefit from preventing cardiac death,” the electrophysiologist concluded.

This study was supported by French governmental research grants. Dr. Fauchier reported serving as a consultant to Bayer, Pfizer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Medtronic, and Novartis.

AT THE ESC CONGRESS 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction who received an ICD for primary prevention and were not on a beta-blocker were at an adjusted 50% increased risk for cardiac death and 34% increased risk for all-cause mortality during 3.2 years of follow-up, but they were at no increased risk for sudden death.

Data source: A retrospective observational study of all of the nearly 4,000 patients who received a primary prevention ICD at the 12 largest French centers during a recent 10-year period.

Disclosures: This study was supported by French governmental research funds. The presenter reported serving as a consultant to Bayer, Pfizer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Medtronic, and Novartis.

Palliative care boosts heart failure patient outcomes

ORLANDO – Systematic introduction of palliative care interventions for patients with advanced heart failure improved patients’ quality of life and spurred their development of advanced-care preferences in a pair of independently performed, controlled, pilot studies.

But, despite demonstrating the ability of palliative-care interventions to help heart failure patients during their final months of life, the findings raised questions about the generalizability and reproducibility of palliative-care interventions that may depend on the skills and experience of the individual specialists who deliver the palliative care.

“Palliative care for patients with cardiovascular disease is in desperate need of good-quality evidence,” commented Larry A, Allen, MD, a heart failure cardiologist at the University of Colorado in Aurora and designated discussant for one of the two studies presented at the meeting. “We need large, randomized trials with clinical outcomes to look at patient outcomes from palliative-care interventions.”

The patients average 71 years old, about half were women, and about 40% were African Americans. They had been diagnosed with heart failure for an average of more than 5 years, all had advanced heart failure, about 60% spent at least half of their time awake immobilized in a bed or chair, and they had average NT-proBNP blood levels of greater than 10,000 pg/mL.

After 24 weeks of intervention, the palliative-care program produced both statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvements in two different measures of health-related quality of life, the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ) and the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy – Palliative Care (FACIT-PAL). The KCCQ showed the palliative care intervention linked with an average rise of more than 9 points compared with patients in the control arm after adjustment for age and sex, a statistically significant increase on a scale where a 5-point rise is considered clinically meaningful. The FACIT-PAL showed an average, adjusted 11-point rise linked with the intervention, a statistically significant increase on a scale where an increase of at least 10 is judged clinically meaningful, reported Dr. Rogers, a heart failure cardiologist and professor of medicine at Duke University.

The palliative-care intervention also led to significant improvements in measures of spirituality, depression, and anxiety, but intervention had no impact on mortality.

“I like these endpoints and the idea that we can make quality-of-life better. These are very sick patients, with a predicted 6-month mortality of 50%. Patients reach a time when they don’t want to live longer but want better life quality for the days they still have,” he said in an interview.

The second report came from a single-center pilot study of 50 patients enrolled when they were hospitalized for acute decompensated heart failure and had at least one addition risk factor for poor prognosis such as age of at least 81 years, renal dysfunction, or a prior heart failure hospitalization within the past year. Patients randomized to the intervention arm underwent a structured evaluation based on the Serious Illness Conversation Guide and performed by a social worker experienced in palliative care and embedded in the heart failure clinical team. The primary endpoint of the SWAP-HF (Social Worker–Aided Palliative Care Intervention in High Risk Patients with Heart Failure) study was clinical-level documentation of advanced-care preferences by 6 months after the program began.

“Although more comprehensive, multidisciplinary palliative care interventions may also be effective, the focused approach [used in this study] may represent a cost-effective and scalable method for shepherding limited specialty resources to enhance the delivery of patient-centered care,” Dr. Desai said. In other words, a program with a social worker costs less than a two-person staff with a palliative-care physician and nurse practitioner.

Despite its relative simplicity, the SWAP-HF intervention had some unique aspects that make it generalizability uncertain, commented Dr. Allen. The embedding of a social worker on the heart failure team placed a professional with a “good understanding of social context” right on the scene with everyone else delivering care to the heart failure patient, a good strategy for minimizing fragmentation, he said. In addition, the place where the study was done, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, “is not your average hospital,” he noted,

In addition, the timing of the intervention studied during hospitalization may be problematic. Clinicians need to “be careful about patients making long-term decisions” about their care while they are hospitalized, a time when patients can be “ill, confused, and scared.” He cited recent findings from a study of hospital-based palliative-care interventions for family members of patients with chronic critical illness that did not reduce anxiety or depression symptoms among the treated family members and may have increased symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (JAMA. 2016 July 5;374[1]:51-62).

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

It’s very exciting to have these two studies presented at the Heart Failure Society of America’s annual meeting. Palliative-care research now receives funding from the National Institutes of Health, but consistently and successfully integrating palliative care into heart failure management still has a long way to go. In 2004, my colleagues and I published a set of consensus recommendations on how to apply palliative care methods to patients with advanced heart failure and what research needs existed for the field (J Card Fail. 2004 June;10[3]:200-9). Today, 12 years later, many of those research needs remain inadequately addressed.

Sarah J. Goodlin, MD , is chief of geriatrics at the Portland (Ore.) VA Medical Center. She had no disclosures. She made these comments as the designated discussant for Dr. Rogers’ report.

It’s very exciting to have these two studies presented at the Heart Failure Society of America’s annual meeting. Palliative-care research now receives funding from the National Institutes of Health, but consistently and successfully integrating palliative care into heart failure management still has a long way to go. In 2004, my colleagues and I published a set of consensus recommendations on how to apply palliative care methods to patients with advanced heart failure and what research needs existed for the field (J Card Fail. 2004 June;10[3]:200-9). Today, 12 years later, many of those research needs remain inadequately addressed.

Sarah J. Goodlin, MD , is chief of geriatrics at the Portland (Ore.) VA Medical Center. She had no disclosures. She made these comments as the designated discussant for Dr. Rogers’ report.

It’s very exciting to have these two studies presented at the Heart Failure Society of America’s annual meeting. Palliative-care research now receives funding from the National Institutes of Health, but consistently and successfully integrating palliative care into heart failure management still has a long way to go. In 2004, my colleagues and I published a set of consensus recommendations on how to apply palliative care methods to patients with advanced heart failure and what research needs existed for the field (J Card Fail. 2004 June;10[3]:200-9). Today, 12 years later, many of those research needs remain inadequately addressed.

Sarah J. Goodlin, MD , is chief of geriatrics at the Portland (Ore.) VA Medical Center. She had no disclosures. She made these comments as the designated discussant for Dr. Rogers’ report.

ORLANDO – Systematic introduction of palliative care interventions for patients with advanced heart failure improved patients’ quality of life and spurred their development of advanced-care preferences in a pair of independently performed, controlled, pilot studies.

But, despite demonstrating the ability of palliative-care interventions to help heart failure patients during their final months of life, the findings raised questions about the generalizability and reproducibility of palliative-care interventions that may depend on the skills and experience of the individual specialists who deliver the palliative care.

“Palliative care for patients with cardiovascular disease is in desperate need of good-quality evidence,” commented Larry A, Allen, MD, a heart failure cardiologist at the University of Colorado in Aurora and designated discussant for one of the two studies presented at the meeting. “We need large, randomized trials with clinical outcomes to look at patient outcomes from palliative-care interventions.”

The patients average 71 years old, about half were women, and about 40% were African Americans. They had been diagnosed with heart failure for an average of more than 5 years, all had advanced heart failure, about 60% spent at least half of their time awake immobilized in a bed or chair, and they had average NT-proBNP blood levels of greater than 10,000 pg/mL.

After 24 weeks of intervention, the palliative-care program produced both statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvements in two different measures of health-related quality of life, the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ) and the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy – Palliative Care (FACIT-PAL). The KCCQ showed the palliative care intervention linked with an average rise of more than 9 points compared with patients in the control arm after adjustment for age and sex, a statistically significant increase on a scale where a 5-point rise is considered clinically meaningful. The FACIT-PAL showed an average, adjusted 11-point rise linked with the intervention, a statistically significant increase on a scale where an increase of at least 10 is judged clinically meaningful, reported Dr. Rogers, a heart failure cardiologist and professor of medicine at Duke University.

The palliative-care intervention also led to significant improvements in measures of spirituality, depression, and anxiety, but intervention had no impact on mortality.

“I like these endpoints and the idea that we can make quality-of-life better. These are very sick patients, with a predicted 6-month mortality of 50%. Patients reach a time when they don’t want to live longer but want better life quality for the days they still have,” he said in an interview.

The second report came from a single-center pilot study of 50 patients enrolled when they were hospitalized for acute decompensated heart failure and had at least one addition risk factor for poor prognosis such as age of at least 81 years, renal dysfunction, or a prior heart failure hospitalization within the past year. Patients randomized to the intervention arm underwent a structured evaluation based on the Serious Illness Conversation Guide and performed by a social worker experienced in palliative care and embedded in the heart failure clinical team. The primary endpoint of the SWAP-HF (Social Worker–Aided Palliative Care Intervention in High Risk Patients with Heart Failure) study was clinical-level documentation of advanced-care preferences by 6 months after the program began.

“Although more comprehensive, multidisciplinary palliative care interventions may also be effective, the focused approach [used in this study] may represent a cost-effective and scalable method for shepherding limited specialty resources to enhance the delivery of patient-centered care,” Dr. Desai said. In other words, a program with a social worker costs less than a two-person staff with a palliative-care physician and nurse practitioner.

Despite its relative simplicity, the SWAP-HF intervention had some unique aspects that make it generalizability uncertain, commented Dr. Allen. The embedding of a social worker on the heart failure team placed a professional with a “good understanding of social context” right on the scene with everyone else delivering care to the heart failure patient, a good strategy for minimizing fragmentation, he said. In addition, the place where the study was done, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, “is not your average hospital,” he noted,

In addition, the timing of the intervention studied during hospitalization may be problematic. Clinicians need to “be careful about patients making long-term decisions” about their care while they are hospitalized, a time when patients can be “ill, confused, and scared.” He cited recent findings from a study of hospital-based palliative-care interventions for family members of patients with chronic critical illness that did not reduce anxiety or depression symptoms among the treated family members and may have increased symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (JAMA. 2016 July 5;374[1]:51-62).

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

ORLANDO – Systematic introduction of palliative care interventions for patients with advanced heart failure improved patients’ quality of life and spurred their development of advanced-care preferences in a pair of independently performed, controlled, pilot studies.

But, despite demonstrating the ability of palliative-care interventions to help heart failure patients during their final months of life, the findings raised questions about the generalizability and reproducibility of palliative-care interventions that may depend on the skills and experience of the individual specialists who deliver the palliative care.

“Palliative care for patients with cardiovascular disease is in desperate need of good-quality evidence,” commented Larry A, Allen, MD, a heart failure cardiologist at the University of Colorado in Aurora and designated discussant for one of the two studies presented at the meeting. “We need large, randomized trials with clinical outcomes to look at patient outcomes from palliative-care interventions.”

The patients average 71 years old, about half were women, and about 40% were African Americans. They had been diagnosed with heart failure for an average of more than 5 years, all had advanced heart failure, about 60% spent at least half of their time awake immobilized in a bed or chair, and they had average NT-proBNP blood levels of greater than 10,000 pg/mL.

After 24 weeks of intervention, the palliative-care program produced both statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvements in two different measures of health-related quality of life, the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ) and the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy – Palliative Care (FACIT-PAL). The KCCQ showed the palliative care intervention linked with an average rise of more than 9 points compared with patients in the control arm after adjustment for age and sex, a statistically significant increase on a scale where a 5-point rise is considered clinically meaningful. The FACIT-PAL showed an average, adjusted 11-point rise linked with the intervention, a statistically significant increase on a scale where an increase of at least 10 is judged clinically meaningful, reported Dr. Rogers, a heart failure cardiologist and professor of medicine at Duke University.

The palliative-care intervention also led to significant improvements in measures of spirituality, depression, and anxiety, but intervention had no impact on mortality.

“I like these endpoints and the idea that we can make quality-of-life better. These are very sick patients, with a predicted 6-month mortality of 50%. Patients reach a time when they don’t want to live longer but want better life quality for the days they still have,” he said in an interview.

The second report came from a single-center pilot study of 50 patients enrolled when they were hospitalized for acute decompensated heart failure and had at least one addition risk factor for poor prognosis such as age of at least 81 years, renal dysfunction, or a prior heart failure hospitalization within the past year. Patients randomized to the intervention arm underwent a structured evaluation based on the Serious Illness Conversation Guide and performed by a social worker experienced in palliative care and embedded in the heart failure clinical team. The primary endpoint of the SWAP-HF (Social Worker–Aided Palliative Care Intervention in High Risk Patients with Heart Failure) study was clinical-level documentation of advanced-care preferences by 6 months after the program began.

“Although more comprehensive, multidisciplinary palliative care interventions may also be effective, the focused approach [used in this study] may represent a cost-effective and scalable method for shepherding limited specialty resources to enhance the delivery of patient-centered care,” Dr. Desai said. In other words, a program with a social worker costs less than a two-person staff with a palliative-care physician and nurse practitioner.

Despite its relative simplicity, the SWAP-HF intervention had some unique aspects that make it generalizability uncertain, commented Dr. Allen. The embedding of a social worker on the heart failure team placed a professional with a “good understanding of social context” right on the scene with everyone else delivering care to the heart failure patient, a good strategy for minimizing fragmentation, he said. In addition, the place where the study was done, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, “is not your average hospital,” he noted,

In addition, the timing of the intervention studied during hospitalization may be problematic. Clinicians need to “be careful about patients making long-term decisions” about their care while they are hospitalized, a time when patients can be “ill, confused, and scared.” He cited recent findings from a study of hospital-based palliative-care interventions for family members of patients with chronic critical illness that did not reduce anxiety or depression symptoms among the treated family members and may have increased symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (JAMA. 2016 July 5;374[1]:51-62).

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT THE HFSA ANNUAL SCIENTIFIC MEETING

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Palliative care measures boosted patients’ Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire score by an average of 9 points over that of controls.

Data source: PAL-HF, a single-center study with 150 randomized patients with heart failure and SWAP-HF, a single-center study with 50 randomized patients.

Disclosures: Dr. Rogers, Dr. Allen, and Dr. Desai had no relevant disclosures.

Elevated troponins are serious business, even without an MI

Sometimes it seems like cardiac troponin testing has become nearly as ubiquitous as the CBC and the BMP. Concern over atypical presentations of MI has contributed to widespread use in emergency departments and hospitalized patients. But once the test comes back elevated, what do you do with that information?

Typically, the next step is to consult Cardiology, which is a reasonable request with or without a suspicion of MI. Frequently, invasive management is not an option; or perhaps the diagnosis is “type 2 MI.”1

A growing body of evidence is making it clear that any elevation in cardiac troponin is a serious predictor of risk and that the risk is highest if the patient is not having an MI.2 My colleagues and I recently conducted a cohort study of more than 700 veterans at our VA Medical Center addressing this question. We evaluated long-term mortality (6 years) comparing veterans who were diagnosed with MI with those who had troponin elevation and no clinical MI. The diagnostic determination was made for all subjects prospectively as part of a quality improvement project that sought to better care for MI patients at our facility. (In some cases, only single troponin values were measured so we cannot say that all patients in our investigation had a true type 2 MI.)

We found that veterans with an elevation in troponin that was not caused by MI had higher risk of mortality risk than did MI patients.3 The risk started to diverge at 30 days and was 42.0% at 1 year, compared with 29.0% for those with MI (odds ratio, 0.56; 95% confidence interval, 0.41-0.78). This risk continued to separate and, at 6 years, was 77.7% vs. 58.7% (OR, 0.41; 95% CI 0.30-0.56). Our observations agree with other recent publications; what we tried to do in advancing the literature was to construct a robust Cox proportional hazard model to try to better understand if the risk seen in these patients is just because of their being “sicker.”

We tried to capture a number of other acute illness states with variables including TIMI score, being in hospice care, having a “do not resuscitate” order, being in the ICU, receiving CPR, and having a fever or leukocytosis, etc. Despite this modeling, elevated troponin remained a significant predictor of risk. While several variables we modeled remained significant predictors of mortality, their distribution between our two cohorts did not explain the excess mortality risk associated with non-MI troponin.