User login

Cardiac rehab also slashes stroke risk

ROME – Cardiac rehabilitation programs have a previously unappreciated benefit: participants enjoy a 60% reduction in the risk of stroke, Gijs van Halewijn, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

“I think cardiologists are really focused on cardiovascular deaths, especially from MI. But we’ve shown that cardiac rehabilitation also has an effect on cerebrovascular events,” said Dr. van Halewijn of Erasmus University in Rotterdam (the Netherlands).

He presented a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of cardiac rehab conducted during 2010-2015. The purpose was to assess the value provided by cardiac rehab in the contemporary era of acute coronary syndrome management featuring primary percutaneous coronary intervention, drug-eluting stents, and potent medications for secondary cardiovascular prevention. That hadn’t previously been looked at systematically.

“The standard meta-analyses cited in the field include randomized trials from as far back as just after World War II,” Dr. van Halewijn noted in an interview.

He employed the same search and analytic methods utilized by the Cochrane Collaboration in evaluating 18 randomized controlled trials of lifestyle- or exercise-based cardiac rehab, compared with usual care, in a total of 7,691 participants.

The results of the meta-analysis indicate cardiac rehab provides powerful secondary prevention benefits above and beyond those obtained through contemporary interventional procedures and preventive medications.

Cardiovascular mortality was reduced by 58% in cardiac rehab participants compared with usual care controls. The risk of acute MI was decreased by 30%. And in a new observation, cerebrovascular events were reduced by 60% in the four randomized trials in which that was an endpoint. All of these differences were highly statistically significant.

“Interestingly, the number needed to treat was 45 for MI, so if you have 45 patients included in your cardiac rehabilitation program, you can prevent one MI. And you can prevent one cerebrovascular event with 82 participants,” according to Dr. van Halewijn.

Cardiac rehab had no effect on all-cause mortality in the overall meta-analysis. However, in the trials involving comprehensive cardiac rehab programs targeting six or more of the components of secondary cardiovascular prevention described by the British Association for Cardiac Prevention and Rehabilitation (Heart. 2013 Aug;99[15]:1069-71), participation was associated with a 37% reduction in the risk of all-cause mortality, compared with usual care.

Those components are smoking, blood pressure, cholesterol, HbA1c, exercise training, counseling about the importance of exercise, stress management, and checking medications.

In addition, Dr. van Halewijn continued, cardiac rehab programs in which a physician or nurse made sure participants were on guideline-directed cardiovascular medications had a 65% reduction in all-cause mortality, compared with usual care.

“Cardiac rehabilitation’s opportunity is to evolve into comprehensive programs addressing all aspects of lifestyle, risk factor management, and prescription of medications to reduce death and nonfatal events,” the physician concluded.

This study was supported by Erasmus University Medical Center, Imperial College London, and the Dutch Heart Foundation. Dr. van Halewijn reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

bjancin@frontlinemedcom.com

ROME – Cardiac rehabilitation programs have a previously unappreciated benefit: participants enjoy a 60% reduction in the risk of stroke, Gijs van Halewijn, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

“I think cardiologists are really focused on cardiovascular deaths, especially from MI. But we’ve shown that cardiac rehabilitation also has an effect on cerebrovascular events,” said Dr. van Halewijn of Erasmus University in Rotterdam (the Netherlands).

He presented a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of cardiac rehab conducted during 2010-2015. The purpose was to assess the value provided by cardiac rehab in the contemporary era of acute coronary syndrome management featuring primary percutaneous coronary intervention, drug-eluting stents, and potent medications for secondary cardiovascular prevention. That hadn’t previously been looked at systematically.

“The standard meta-analyses cited in the field include randomized trials from as far back as just after World War II,” Dr. van Halewijn noted in an interview.

He employed the same search and analytic methods utilized by the Cochrane Collaboration in evaluating 18 randomized controlled trials of lifestyle- or exercise-based cardiac rehab, compared with usual care, in a total of 7,691 participants.

The results of the meta-analysis indicate cardiac rehab provides powerful secondary prevention benefits above and beyond those obtained through contemporary interventional procedures and preventive medications.

Cardiovascular mortality was reduced by 58% in cardiac rehab participants compared with usual care controls. The risk of acute MI was decreased by 30%. And in a new observation, cerebrovascular events were reduced by 60% in the four randomized trials in which that was an endpoint. All of these differences were highly statistically significant.

“Interestingly, the number needed to treat was 45 for MI, so if you have 45 patients included in your cardiac rehabilitation program, you can prevent one MI. And you can prevent one cerebrovascular event with 82 participants,” according to Dr. van Halewijn.

Cardiac rehab had no effect on all-cause mortality in the overall meta-analysis. However, in the trials involving comprehensive cardiac rehab programs targeting six or more of the components of secondary cardiovascular prevention described by the British Association for Cardiac Prevention and Rehabilitation (Heart. 2013 Aug;99[15]:1069-71), participation was associated with a 37% reduction in the risk of all-cause mortality, compared with usual care.

Those components are smoking, blood pressure, cholesterol, HbA1c, exercise training, counseling about the importance of exercise, stress management, and checking medications.

In addition, Dr. van Halewijn continued, cardiac rehab programs in which a physician or nurse made sure participants were on guideline-directed cardiovascular medications had a 65% reduction in all-cause mortality, compared with usual care.

“Cardiac rehabilitation’s opportunity is to evolve into comprehensive programs addressing all aspects of lifestyle, risk factor management, and prescription of medications to reduce death and nonfatal events,” the physician concluded.

This study was supported by Erasmus University Medical Center, Imperial College London, and the Dutch Heart Foundation. Dr. van Halewijn reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

bjancin@frontlinemedcom.com

ROME – Cardiac rehabilitation programs have a previously unappreciated benefit: participants enjoy a 60% reduction in the risk of stroke, Gijs van Halewijn, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

“I think cardiologists are really focused on cardiovascular deaths, especially from MI. But we’ve shown that cardiac rehabilitation also has an effect on cerebrovascular events,” said Dr. van Halewijn of Erasmus University in Rotterdam (the Netherlands).

He presented a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of cardiac rehab conducted during 2010-2015. The purpose was to assess the value provided by cardiac rehab in the contemporary era of acute coronary syndrome management featuring primary percutaneous coronary intervention, drug-eluting stents, and potent medications for secondary cardiovascular prevention. That hadn’t previously been looked at systematically.

“The standard meta-analyses cited in the field include randomized trials from as far back as just after World War II,” Dr. van Halewijn noted in an interview.

He employed the same search and analytic methods utilized by the Cochrane Collaboration in evaluating 18 randomized controlled trials of lifestyle- or exercise-based cardiac rehab, compared with usual care, in a total of 7,691 participants.

The results of the meta-analysis indicate cardiac rehab provides powerful secondary prevention benefits above and beyond those obtained through contemporary interventional procedures and preventive medications.

Cardiovascular mortality was reduced by 58% in cardiac rehab participants compared with usual care controls. The risk of acute MI was decreased by 30%. And in a new observation, cerebrovascular events were reduced by 60% in the four randomized trials in which that was an endpoint. All of these differences were highly statistically significant.

“Interestingly, the number needed to treat was 45 for MI, so if you have 45 patients included in your cardiac rehabilitation program, you can prevent one MI. And you can prevent one cerebrovascular event with 82 participants,” according to Dr. van Halewijn.

Cardiac rehab had no effect on all-cause mortality in the overall meta-analysis. However, in the trials involving comprehensive cardiac rehab programs targeting six or more of the components of secondary cardiovascular prevention described by the British Association for Cardiac Prevention and Rehabilitation (Heart. 2013 Aug;99[15]:1069-71), participation was associated with a 37% reduction in the risk of all-cause mortality, compared with usual care.

Those components are smoking, blood pressure, cholesterol, HbA1c, exercise training, counseling about the importance of exercise, stress management, and checking medications.

In addition, Dr. van Halewijn continued, cardiac rehab programs in which a physician or nurse made sure participants were on guideline-directed cardiovascular medications had a 65% reduction in all-cause mortality, compared with usual care.

“Cardiac rehabilitation’s opportunity is to evolve into comprehensive programs addressing all aspects of lifestyle, risk factor management, and prescription of medications to reduce death and nonfatal events,” the physician concluded.

This study was supported by Erasmus University Medical Center, Imperial College London, and the Dutch Heart Foundation. Dr. van Halewijn reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

bjancin@frontlinemedcom.com

AT THE ESC CONGRESS 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The number of patients who need to participate in a cardiac rehabilitation program following an ACS in order to prevent one cerebrovascular event is 85.

Data source: This was a meta-analysis of 18 randomized trials carried out in 2010-2015 comparing contemporary cardiac rehabilitation to usual care in 7,691 patients.

Disclosures: This study was supported by Erasmus University (Rotterdam, the Netherlands) Medical Center, Imperial College London, and the Dutch Heart Foundation. The presenter reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

Diabetes drugs with cardiovascular benefits broaden cardiology’s turf

The dramatic reduction in cardiovascular death and heart failure hospitalization seen during treatment with empagliflozin (Jardiance) in the EMPA-REG OUTCOME (Empagliflozin Cardiovascular Outcome Event Trial in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients) trial, for example, has prompted some cardiologists in the year since the first EMPA-REG report to become active prescribers of the drug to their patients who have type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease. The same evidence has driven other cardiologists who may not feel fully comfortable prescribing an antidiabetic drug on their own to enter into active partnerships with endocrinologists to work as a team to put diabetes patients with cardiovascular disease on empagliflozin.

In Dr. Fitchett’s practice, “if a patient with type 2 diabetes has an endocrinologist, then I will send a letter to that physician saying I think the patient should be on one of these drugs,” empagliflozin or liraglutide, he said. “If the patient is being treated by a primary care physician, then I will prescribe empagliflozin myself because most primary care physicians are not willing to prescribe it. I think more and more cardiologists are doing this. The great thing about empagliflozin and liraglutide is that they do not cause hypoglycemia and the adverse effect profiles are relatively good. As long as drug cost is not an issue, then as cardiologists we need to adjust glycemia control with cardiovascular benefit as we did years ago with statin treatment,” explained Dr. Fitchett, a cardiologist at St. Michael’s Hospital in Toronto and a senior collaborator and coauthor on the EMPA-REG study.

When results from the 4S [Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study] came out in 1994, proving that long-term statin treatment was both safe and increased survival in patients with coronary heart disease, “cardiologists took over lipid management from endocrinologists,” he recalled. “We now have a safe and simple treatment for glucose lowering that also cuts cardiovascular disease events, so cardiologists have to also be involved, at least to some extent. Their degree of involvement depends on their practice and who provides a patient’s primary diabetes care,” he said.

Cardiologists vary on empagliflozin

Other cardiologists are mixed in their take on personally prescribing antidiabetic drugs to high-risk patients with type 2 diabetes. Greg C. Fonarow, MD, has also aggressively taken to empagliflozin over the past year, especially for his patients with heart failure or at high risk for developing heart failure. The EMPA-REG results showed that empagliflozin’s potent impact on reducing cardiovascular death in patients linked closely with a reduction in heart failure hospitalizations. In his recent experience, endocrinologists as well as other physicians who care for patients with type 2 diabetes “are often reluctant to make any changes [in a patient’s hypoglycemic regimen], and in general they have not gravitated toward the treatments that have been shown to improve cardiovascular outcomes and instead focus solely on a patient’s hemoglobin A1c,” Dr. Fonarow said in an interview at the recent annual meeting of the Heart Failure Society of America.

He said he prescribes empagliflozin to patients with type 2 diabetes if they are hospitalized for heart failure or as outpatients, and he targets it to patients diagnosed with heart failure – including heart failure with preserved ejection fraction – as well as to patients with other forms of cardiovascular disease, closely following the EMPA-REG enrollment criteria. It’s too early in the experience with empagliflozin to use it preferentially in diabetes patients without cardiovascular disease or patients who in any other way fall outside the enrollment criteria for EMPA-REG, he said.

“I am happy to consult with their endocrinologist, or I tell patients to discuss this treatment with their endocrinologist. If the endocrinologist prescribes empagliflozin, great; if not, I feel an obligation to provide the best care I can to my patients. This is not a hard medication to use. The safety profile is good. Treatment with empagliflozin obviously has renal-function considerations, but that’s true for many drugs. The biggest challenge is what is covered by the patient’s insurance. We often need preauthorization.

“So far I have seen excellent responses in patients for both metabolic control and clinical responses in patients with heart failure. Their symptoms seem to improve,” said Dr. Fonarow, professor of medicine and co-chief of cardiology at the University of Southern California , Los Angeles.

While Dr. Fonarow cautioned that he also would not start empagliflozin in a patient with a HbA1c below 7%, he would seriously consider swapping out a patient’s drug for empagliflozin if it were a sulfonylurea or a dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor. He stopped short of suggesting a substitution of empagliflozin for metformin. In Dr. Fonarow’s opinion, the evidence for empagliflozin is also “more robust” than it has been for liraglutide or semaglutide. With what’s now known about the clinical impact of these drugs, he foresees a time when a combination between a SGLT-2 inhibitor, with its effect on heart failure, and a GLP-1 analogue, with its effect on atherosclerotic disease, may seem an ideal initial drug pairing for patients with type 2 diabetes and significant cardiovascular disease risk, with metformin relegated to a second-line role.

Other cardiologists endorsed a more collaborative approach to prescribing empagliflozin and liraglutide.

Another team-approach advocate is Robert O. Bonow, MD, cardiologist and professor of medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago. “Cardiologists are comfortable prescribing metformin and telling patients about lifestyle, but when it comes to newer antidiabetic drugs, that’s a new field, and a team approach may be best,” he said in an interview. “If possible, a cardiologist should have a friendly partnership with a diabetologist or endocrinologist who is expert in treating diabetes.” Many cardiologists now work in and for hospitals, and easy access to an endocrinologist is probably available, he noted.

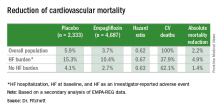

But new analyses of the EMPA-REG data reported by Dr. Fitchett at the ESC congress showed that empagliflozin treatment exerted a similar benefit of reduced cardiovascular death regardless of whether patients had prevalent heart failure at entry into the study, incident heart failure during follow-up, or no heart failure of any sort.

Impact of heart failure in EMPA-REG

Roughly 10% of the 7,020 patients enrolled in EMPA-REG had heart failure at the time they entered the trial. During a median follow-up of just over 3 years, the incidence of new-onset heart failure – tallied as either a new heart failure hospitalization or a clinical episode deemed to be heart failure by an investigator – occurred in 4.6% of patients on empagliflozin and in 6.5% of patients in the placebo arm, a 1.9-percentage-point difference and a 30% relative risk reduction linked with empagliflozin use, Dr. Fitchett reported.

The main EMPA-REG outcome was a composite of cardiovascular death, nonfatal MI, and nonfatal stroke. This positive outcome in favor of empagliflozin treatment was primarily driven by a difference in the rate of cardiovascular death. In the new analysis, the relative reduction in cardiovascular deaths with empagliflozin compared with placebo was 29% among patients with prevalent heart failure at baseline, 35% among those who had an incident heart failure hospitalization during follow-up, 27% among patients with an incident heart failure episode diagnosed by an investigator during follow-up, 33% among the combined group of trial patients with any form of heart failure at trial entry or during the trial (those with prevalent heart failure at baseline plus those with an incident event), and 37% among the large number of patients in the trial who remained free from any indication of heart failure during follow-up.

In short, treatment with empagliflozin “reduced cardiovascular mortality by the same relative amount” regardless of whether patients did or did not have heart failure during the trial,” Dr. Fitchett concluded.

Additional secondary analyses from EMPA-REG reported at the ESC congress in August also documented that the benefit from empagliflozin treatment was roughly the same regardless of the age of patients enrolled in the trial and regardless of patients’ blood level of LDL cholesterol at entry into the study. These findings provide “confidence in the consistency of the effect” by empagliflozin, Dr. Fitchett said.

The endocrinologists’ view

“Most cardiologists are not thoroughly familiar with the full palette of medications for hyperglycemia. Selection of medication should not be made solely on the basis of results from a cardiovascular outcomes trial,” said Helena W. Rodbard, MD, a clinical endocrinologist in Rockville, Md.

“The EMPA-REG OUTCOMES and LEADER results are very exciting and encouraging. When all other factors are equal, the cardiovascular results could sway the decision about which medication to use. But an endocrinologist is in the best position to balance the many factors when choosing combination therapy and to set a target level for HbA1c, fasting blood glucose, and postprandial glucose, and to adjust therapy to minimize the risk of hypoglycemia,” Dr. Rodbard said in an interview.

He called empagliflozin a drug with “interesting promise,” especially for patients with incipient heart failure. The extra cardiovascular benefit from the GLP-1 analogues is “less settled,” although the liraglutide and semaglutide trial results are important and mean these drugs need more consideration and study. The EMPA-REG results were more clearly positive, he said.

“Metformin is still the initial drug” for most patients with type 2 diabetes, echoed Dr. Levy. Drugs like empagliflozin and liraglutide are usually used in combination with metformin.

“Like many endocrinologists, I have for some time used the oral SGLT-2 inhibitors and GLP-1 analogues in combination with metformin. It made sense before the recent cardiovascular data appeared, and it makes even more sense now,” said Dr. Jellinger, professor of clinical medicine and an endocrinologist at the University of Miami.

“Endocrinologists and diabetologists are aware that cardiologists have been taking a larger role in the care of patients with diabetes,” noted Dr. Rodbard. “I favor cardiologists and endocrinologists working in concert to improve the care of patients with diabetes.”

“Over the next few years, we will need to decide whether to treat patients with type 2 diabetes with an agent with proven benefits,” said Dr. Fitchett. “Until the results from EMPA-REG and the LEADER trial came out, there was no specific glucose-lowering agent that also reduced cardiovascular events. Some cardiologists might ask when they should get involved in managing patients with type 2 diabetes. What I would do for patients with a history of cardiovascular disease who develop new type 2 diabetes is start empagliflozin as their first drug,” Dr. Fitchett said, though he admitted that no evidence yet exists to back that approach.

The EMPA-REG trial was sponsored by Boehringer Ingelheim and by Eli Lilly, the companies that market empagliflozin. The LEADER trial was sponsored in part by Novo Nordisk, the company that markets liraglutide. Dr. Fitchett and Dr. Mentz were both researchers for EMPA-REG. Dr. Fitchett has been a consultant to AstraZeneca, Merck, and Amgen. Dr. Mentz has been an adviser to Boehringer Ingelheim. Dr. Fonarow has been an adviser to Amgen, Janssen, Novartis, and ZS Pharma. Dr. Bozkurt had no disclosures. Dr. Bonow has been a consultant to Gilead. Dr. Jellinger has been a speaker on behalf of Boehringer-Ingelheim, Novo Nordisk, Merck, and Janssen. Dr. Rodbard has been a consultant to or speaker for several drug companies including Boehringer-Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, and Novo Nordisk. Dr. Levy has been a speaker on behalf of Boehringer-Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, and AstraZeneca. Dr. Hellman had no disclosures.

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

The dramatic reduction in cardiovascular death and heart failure hospitalization seen during treatment with empagliflozin (Jardiance) in the EMPA-REG OUTCOME (Empagliflozin Cardiovascular Outcome Event Trial in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients) trial, for example, has prompted some cardiologists in the year since the first EMPA-REG report to become active prescribers of the drug to their patients who have type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease. The same evidence has driven other cardiologists who may not feel fully comfortable prescribing an antidiabetic drug on their own to enter into active partnerships with endocrinologists to work as a team to put diabetes patients with cardiovascular disease on empagliflozin.

In Dr. Fitchett’s practice, “if a patient with type 2 diabetes has an endocrinologist, then I will send a letter to that physician saying I think the patient should be on one of these drugs,” empagliflozin or liraglutide, he said. “If the patient is being treated by a primary care physician, then I will prescribe empagliflozin myself because most primary care physicians are not willing to prescribe it. I think more and more cardiologists are doing this. The great thing about empagliflozin and liraglutide is that they do not cause hypoglycemia and the adverse effect profiles are relatively good. As long as drug cost is not an issue, then as cardiologists we need to adjust glycemia control with cardiovascular benefit as we did years ago with statin treatment,” explained Dr. Fitchett, a cardiologist at St. Michael’s Hospital in Toronto and a senior collaborator and coauthor on the EMPA-REG study.

When results from the 4S [Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study] came out in 1994, proving that long-term statin treatment was both safe and increased survival in patients with coronary heart disease, “cardiologists took over lipid management from endocrinologists,” he recalled. “We now have a safe and simple treatment for glucose lowering that also cuts cardiovascular disease events, so cardiologists have to also be involved, at least to some extent. Their degree of involvement depends on their practice and who provides a patient’s primary diabetes care,” he said.

Cardiologists vary on empagliflozin

Other cardiologists are mixed in their take on personally prescribing antidiabetic drugs to high-risk patients with type 2 diabetes. Greg C. Fonarow, MD, has also aggressively taken to empagliflozin over the past year, especially for his patients with heart failure or at high risk for developing heart failure. The EMPA-REG results showed that empagliflozin’s potent impact on reducing cardiovascular death in patients linked closely with a reduction in heart failure hospitalizations. In his recent experience, endocrinologists as well as other physicians who care for patients with type 2 diabetes “are often reluctant to make any changes [in a patient’s hypoglycemic regimen], and in general they have not gravitated toward the treatments that have been shown to improve cardiovascular outcomes and instead focus solely on a patient’s hemoglobin A1c,” Dr. Fonarow said in an interview at the recent annual meeting of the Heart Failure Society of America.

He said he prescribes empagliflozin to patients with type 2 diabetes if they are hospitalized for heart failure or as outpatients, and he targets it to patients diagnosed with heart failure – including heart failure with preserved ejection fraction – as well as to patients with other forms of cardiovascular disease, closely following the EMPA-REG enrollment criteria. It’s too early in the experience with empagliflozin to use it preferentially in diabetes patients without cardiovascular disease or patients who in any other way fall outside the enrollment criteria for EMPA-REG, he said.

“I am happy to consult with their endocrinologist, or I tell patients to discuss this treatment with their endocrinologist. If the endocrinologist prescribes empagliflozin, great; if not, I feel an obligation to provide the best care I can to my patients. This is not a hard medication to use. The safety profile is good. Treatment with empagliflozin obviously has renal-function considerations, but that’s true for many drugs. The biggest challenge is what is covered by the patient’s insurance. We often need preauthorization.

“So far I have seen excellent responses in patients for both metabolic control and clinical responses in patients with heart failure. Their symptoms seem to improve,” said Dr. Fonarow, professor of medicine and co-chief of cardiology at the University of Southern California , Los Angeles.

While Dr. Fonarow cautioned that he also would not start empagliflozin in a patient with a HbA1c below 7%, he would seriously consider swapping out a patient’s drug for empagliflozin if it were a sulfonylurea or a dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor. He stopped short of suggesting a substitution of empagliflozin for metformin. In Dr. Fonarow’s opinion, the evidence for empagliflozin is also “more robust” than it has been for liraglutide or semaglutide. With what’s now known about the clinical impact of these drugs, he foresees a time when a combination between a SGLT-2 inhibitor, with its effect on heart failure, and a GLP-1 analogue, with its effect on atherosclerotic disease, may seem an ideal initial drug pairing for patients with type 2 diabetes and significant cardiovascular disease risk, with metformin relegated to a second-line role.

Other cardiologists endorsed a more collaborative approach to prescribing empagliflozin and liraglutide.

Another team-approach advocate is Robert O. Bonow, MD, cardiologist and professor of medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago. “Cardiologists are comfortable prescribing metformin and telling patients about lifestyle, but when it comes to newer antidiabetic drugs, that’s a new field, and a team approach may be best,” he said in an interview. “If possible, a cardiologist should have a friendly partnership with a diabetologist or endocrinologist who is expert in treating diabetes.” Many cardiologists now work in and for hospitals, and easy access to an endocrinologist is probably available, he noted.

But new analyses of the EMPA-REG data reported by Dr. Fitchett at the ESC congress showed that empagliflozin treatment exerted a similar benefit of reduced cardiovascular death regardless of whether patients had prevalent heart failure at entry into the study, incident heart failure during follow-up, or no heart failure of any sort.

Impact of heart failure in EMPA-REG

Roughly 10% of the 7,020 patients enrolled in EMPA-REG had heart failure at the time they entered the trial. During a median follow-up of just over 3 years, the incidence of new-onset heart failure – tallied as either a new heart failure hospitalization or a clinical episode deemed to be heart failure by an investigator – occurred in 4.6% of patients on empagliflozin and in 6.5% of patients in the placebo arm, a 1.9-percentage-point difference and a 30% relative risk reduction linked with empagliflozin use, Dr. Fitchett reported.

The main EMPA-REG outcome was a composite of cardiovascular death, nonfatal MI, and nonfatal stroke. This positive outcome in favor of empagliflozin treatment was primarily driven by a difference in the rate of cardiovascular death. In the new analysis, the relative reduction in cardiovascular deaths with empagliflozin compared with placebo was 29% among patients with prevalent heart failure at baseline, 35% among those who had an incident heart failure hospitalization during follow-up, 27% among patients with an incident heart failure episode diagnosed by an investigator during follow-up, 33% among the combined group of trial patients with any form of heart failure at trial entry or during the trial (those with prevalent heart failure at baseline plus those with an incident event), and 37% among the large number of patients in the trial who remained free from any indication of heart failure during follow-up.

In short, treatment with empagliflozin “reduced cardiovascular mortality by the same relative amount” regardless of whether patients did or did not have heart failure during the trial,” Dr. Fitchett concluded.

Additional secondary analyses from EMPA-REG reported at the ESC congress in August also documented that the benefit from empagliflozin treatment was roughly the same regardless of the age of patients enrolled in the trial and regardless of patients’ blood level of LDL cholesterol at entry into the study. These findings provide “confidence in the consistency of the effect” by empagliflozin, Dr. Fitchett said.

The endocrinologists’ view

“Most cardiologists are not thoroughly familiar with the full palette of medications for hyperglycemia. Selection of medication should not be made solely on the basis of results from a cardiovascular outcomes trial,” said Helena W. Rodbard, MD, a clinical endocrinologist in Rockville, Md.

“The EMPA-REG OUTCOMES and LEADER results are very exciting and encouraging. When all other factors are equal, the cardiovascular results could sway the decision about which medication to use. But an endocrinologist is in the best position to balance the many factors when choosing combination therapy and to set a target level for HbA1c, fasting blood glucose, and postprandial glucose, and to adjust therapy to minimize the risk of hypoglycemia,” Dr. Rodbard said in an interview.

He called empagliflozin a drug with “interesting promise,” especially for patients with incipient heart failure. The extra cardiovascular benefit from the GLP-1 analogues is “less settled,” although the liraglutide and semaglutide trial results are important and mean these drugs need more consideration and study. The EMPA-REG results were more clearly positive, he said.

“Metformin is still the initial drug” for most patients with type 2 diabetes, echoed Dr. Levy. Drugs like empagliflozin and liraglutide are usually used in combination with metformin.

“Like many endocrinologists, I have for some time used the oral SGLT-2 inhibitors and GLP-1 analogues in combination with metformin. It made sense before the recent cardiovascular data appeared, and it makes even more sense now,” said Dr. Jellinger, professor of clinical medicine and an endocrinologist at the University of Miami.

“Endocrinologists and diabetologists are aware that cardiologists have been taking a larger role in the care of patients with diabetes,” noted Dr. Rodbard. “I favor cardiologists and endocrinologists working in concert to improve the care of patients with diabetes.”

“Over the next few years, we will need to decide whether to treat patients with type 2 diabetes with an agent with proven benefits,” said Dr. Fitchett. “Until the results from EMPA-REG and the LEADER trial came out, there was no specific glucose-lowering agent that also reduced cardiovascular events. Some cardiologists might ask when they should get involved in managing patients with type 2 diabetes. What I would do for patients with a history of cardiovascular disease who develop new type 2 diabetes is start empagliflozin as their first drug,” Dr. Fitchett said, though he admitted that no evidence yet exists to back that approach.

The EMPA-REG trial was sponsored by Boehringer Ingelheim and by Eli Lilly, the companies that market empagliflozin. The LEADER trial was sponsored in part by Novo Nordisk, the company that markets liraglutide. Dr. Fitchett and Dr. Mentz were both researchers for EMPA-REG. Dr. Fitchett has been a consultant to AstraZeneca, Merck, and Amgen. Dr. Mentz has been an adviser to Boehringer Ingelheim. Dr. Fonarow has been an adviser to Amgen, Janssen, Novartis, and ZS Pharma. Dr. Bozkurt had no disclosures. Dr. Bonow has been a consultant to Gilead. Dr. Jellinger has been a speaker on behalf of Boehringer-Ingelheim, Novo Nordisk, Merck, and Janssen. Dr. Rodbard has been a consultant to or speaker for several drug companies including Boehringer-Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, and Novo Nordisk. Dr. Levy has been a speaker on behalf of Boehringer-Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, and AstraZeneca. Dr. Hellman had no disclosures.

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

The dramatic reduction in cardiovascular death and heart failure hospitalization seen during treatment with empagliflozin (Jardiance) in the EMPA-REG OUTCOME (Empagliflozin Cardiovascular Outcome Event Trial in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients) trial, for example, has prompted some cardiologists in the year since the first EMPA-REG report to become active prescribers of the drug to their patients who have type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease. The same evidence has driven other cardiologists who may not feel fully comfortable prescribing an antidiabetic drug on their own to enter into active partnerships with endocrinologists to work as a team to put diabetes patients with cardiovascular disease on empagliflozin.

In Dr. Fitchett’s practice, “if a patient with type 2 diabetes has an endocrinologist, then I will send a letter to that physician saying I think the patient should be on one of these drugs,” empagliflozin or liraglutide, he said. “If the patient is being treated by a primary care physician, then I will prescribe empagliflozin myself because most primary care physicians are not willing to prescribe it. I think more and more cardiologists are doing this. The great thing about empagliflozin and liraglutide is that they do not cause hypoglycemia and the adverse effect profiles are relatively good. As long as drug cost is not an issue, then as cardiologists we need to adjust glycemia control with cardiovascular benefit as we did years ago with statin treatment,” explained Dr. Fitchett, a cardiologist at St. Michael’s Hospital in Toronto and a senior collaborator and coauthor on the EMPA-REG study.

When results from the 4S [Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study] came out in 1994, proving that long-term statin treatment was both safe and increased survival in patients with coronary heart disease, “cardiologists took over lipid management from endocrinologists,” he recalled. “We now have a safe and simple treatment for glucose lowering that also cuts cardiovascular disease events, so cardiologists have to also be involved, at least to some extent. Their degree of involvement depends on their practice and who provides a patient’s primary diabetes care,” he said.

Cardiologists vary on empagliflozin

Other cardiologists are mixed in their take on personally prescribing antidiabetic drugs to high-risk patients with type 2 diabetes. Greg C. Fonarow, MD, has also aggressively taken to empagliflozin over the past year, especially for his patients with heart failure or at high risk for developing heart failure. The EMPA-REG results showed that empagliflozin’s potent impact on reducing cardiovascular death in patients linked closely with a reduction in heart failure hospitalizations. In his recent experience, endocrinologists as well as other physicians who care for patients with type 2 diabetes “are often reluctant to make any changes [in a patient’s hypoglycemic regimen], and in general they have not gravitated toward the treatments that have been shown to improve cardiovascular outcomes and instead focus solely on a patient’s hemoglobin A1c,” Dr. Fonarow said in an interview at the recent annual meeting of the Heart Failure Society of America.

He said he prescribes empagliflozin to patients with type 2 diabetes if they are hospitalized for heart failure or as outpatients, and he targets it to patients diagnosed with heart failure – including heart failure with preserved ejection fraction – as well as to patients with other forms of cardiovascular disease, closely following the EMPA-REG enrollment criteria. It’s too early in the experience with empagliflozin to use it preferentially in diabetes patients without cardiovascular disease or patients who in any other way fall outside the enrollment criteria for EMPA-REG, he said.

“I am happy to consult with their endocrinologist, or I tell patients to discuss this treatment with their endocrinologist. If the endocrinologist prescribes empagliflozin, great; if not, I feel an obligation to provide the best care I can to my patients. This is not a hard medication to use. The safety profile is good. Treatment with empagliflozin obviously has renal-function considerations, but that’s true for many drugs. The biggest challenge is what is covered by the patient’s insurance. We often need preauthorization.

“So far I have seen excellent responses in patients for both metabolic control and clinical responses in patients with heart failure. Their symptoms seem to improve,” said Dr. Fonarow, professor of medicine and co-chief of cardiology at the University of Southern California , Los Angeles.

While Dr. Fonarow cautioned that he also would not start empagliflozin in a patient with a HbA1c below 7%, he would seriously consider swapping out a patient’s drug for empagliflozin if it were a sulfonylurea or a dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor. He stopped short of suggesting a substitution of empagliflozin for metformin. In Dr. Fonarow’s opinion, the evidence for empagliflozin is also “more robust” than it has been for liraglutide or semaglutide. With what’s now known about the clinical impact of these drugs, he foresees a time when a combination between a SGLT-2 inhibitor, with its effect on heart failure, and a GLP-1 analogue, with its effect on atherosclerotic disease, may seem an ideal initial drug pairing for patients with type 2 diabetes and significant cardiovascular disease risk, with metformin relegated to a second-line role.

Other cardiologists endorsed a more collaborative approach to prescribing empagliflozin and liraglutide.

Another team-approach advocate is Robert O. Bonow, MD, cardiologist and professor of medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago. “Cardiologists are comfortable prescribing metformin and telling patients about lifestyle, but when it comes to newer antidiabetic drugs, that’s a new field, and a team approach may be best,” he said in an interview. “If possible, a cardiologist should have a friendly partnership with a diabetologist or endocrinologist who is expert in treating diabetes.” Many cardiologists now work in and for hospitals, and easy access to an endocrinologist is probably available, he noted.

But new analyses of the EMPA-REG data reported by Dr. Fitchett at the ESC congress showed that empagliflozin treatment exerted a similar benefit of reduced cardiovascular death regardless of whether patients had prevalent heart failure at entry into the study, incident heart failure during follow-up, or no heart failure of any sort.

Impact of heart failure in EMPA-REG

Roughly 10% of the 7,020 patients enrolled in EMPA-REG had heart failure at the time they entered the trial. During a median follow-up of just over 3 years, the incidence of new-onset heart failure – tallied as either a new heart failure hospitalization or a clinical episode deemed to be heart failure by an investigator – occurred in 4.6% of patients on empagliflozin and in 6.5% of patients in the placebo arm, a 1.9-percentage-point difference and a 30% relative risk reduction linked with empagliflozin use, Dr. Fitchett reported.

The main EMPA-REG outcome was a composite of cardiovascular death, nonfatal MI, and nonfatal stroke. This positive outcome in favor of empagliflozin treatment was primarily driven by a difference in the rate of cardiovascular death. In the new analysis, the relative reduction in cardiovascular deaths with empagliflozin compared with placebo was 29% among patients with prevalent heart failure at baseline, 35% among those who had an incident heart failure hospitalization during follow-up, 27% among patients with an incident heart failure episode diagnosed by an investigator during follow-up, 33% among the combined group of trial patients with any form of heart failure at trial entry or during the trial (those with prevalent heart failure at baseline plus those with an incident event), and 37% among the large number of patients in the trial who remained free from any indication of heart failure during follow-up.

In short, treatment with empagliflozin “reduced cardiovascular mortality by the same relative amount” regardless of whether patients did or did not have heart failure during the trial,” Dr. Fitchett concluded.

Additional secondary analyses from EMPA-REG reported at the ESC congress in August also documented that the benefit from empagliflozin treatment was roughly the same regardless of the age of patients enrolled in the trial and regardless of patients’ blood level of LDL cholesterol at entry into the study. These findings provide “confidence in the consistency of the effect” by empagliflozin, Dr. Fitchett said.

The endocrinologists’ view

“Most cardiologists are not thoroughly familiar with the full palette of medications for hyperglycemia. Selection of medication should not be made solely on the basis of results from a cardiovascular outcomes trial,” said Helena W. Rodbard, MD, a clinical endocrinologist in Rockville, Md.

“The EMPA-REG OUTCOMES and LEADER results are very exciting and encouraging. When all other factors are equal, the cardiovascular results could sway the decision about which medication to use. But an endocrinologist is in the best position to balance the many factors when choosing combination therapy and to set a target level for HbA1c, fasting blood glucose, and postprandial glucose, and to adjust therapy to minimize the risk of hypoglycemia,” Dr. Rodbard said in an interview.

He called empagliflozin a drug with “interesting promise,” especially for patients with incipient heart failure. The extra cardiovascular benefit from the GLP-1 analogues is “less settled,” although the liraglutide and semaglutide trial results are important and mean these drugs need more consideration and study. The EMPA-REG results were more clearly positive, he said.

“Metformin is still the initial drug” for most patients with type 2 diabetes, echoed Dr. Levy. Drugs like empagliflozin and liraglutide are usually used in combination with metformin.

“Like many endocrinologists, I have for some time used the oral SGLT-2 inhibitors and GLP-1 analogues in combination with metformin. It made sense before the recent cardiovascular data appeared, and it makes even more sense now,” said Dr. Jellinger, professor of clinical medicine and an endocrinologist at the University of Miami.

“Endocrinologists and diabetologists are aware that cardiologists have been taking a larger role in the care of patients with diabetes,” noted Dr. Rodbard. “I favor cardiologists and endocrinologists working in concert to improve the care of patients with diabetes.”

“Over the next few years, we will need to decide whether to treat patients with type 2 diabetes with an agent with proven benefits,” said Dr. Fitchett. “Until the results from EMPA-REG and the LEADER trial came out, there was no specific glucose-lowering agent that also reduced cardiovascular events. Some cardiologists might ask when they should get involved in managing patients with type 2 diabetes. What I would do for patients with a history of cardiovascular disease who develop new type 2 diabetes is start empagliflozin as their first drug,” Dr. Fitchett said, though he admitted that no evidence yet exists to back that approach.

The EMPA-REG trial was sponsored by Boehringer Ingelheim and by Eli Lilly, the companies that market empagliflozin. The LEADER trial was sponsored in part by Novo Nordisk, the company that markets liraglutide. Dr. Fitchett and Dr. Mentz were both researchers for EMPA-REG. Dr. Fitchett has been a consultant to AstraZeneca, Merck, and Amgen. Dr. Mentz has been an adviser to Boehringer Ingelheim. Dr. Fonarow has been an adviser to Amgen, Janssen, Novartis, and ZS Pharma. Dr. Bozkurt had no disclosures. Dr. Bonow has been a consultant to Gilead. Dr. Jellinger has been a speaker on behalf of Boehringer-Ingelheim, Novo Nordisk, Merck, and Janssen. Dr. Rodbard has been a consultant to or speaker for several drug companies including Boehringer-Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, and Novo Nordisk. Dr. Levy has been a speaker on behalf of Boehringer-Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, and AstraZeneca. Dr. Hellman had no disclosures.

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

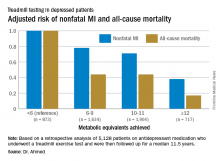

Cardiorespiratory fitness improves survival after depression

ROME – Cardiorespiratory fitness provided strong and graded protection against all-cause mortality and nonfatal MI in a study of more than 5,000 patients treated for depression, Amjad M. Ahmed, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

“These results highlight the importance of assessing fitness to identify risk as well as promoting an active lifestyle in patients with depression,” said Dr. Ahmed of Abdulaziz University for Health Sciences in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

This analysis focused on the 5,128 subjects who were on antidepressant medication at the time of their treadmill test. Their baseline cardiorespiratory fitness, as estimated by achieved peak metabolic equivalents (METs) on the treadmill, varied inversely with their risks of acute MI and all-cause mortality in the years to come. However, the less fit a patient was, the greater the burden of traditional cardiovascular risk factors. For example, the prevalence of hypertension was 86% in patients who achieved fewer than 6 METs, 75% in those who achieved 6-9 METs, 62% in depressed patients who reached 10-11 METs, and 51% in those who achieved 12 METs or more.

For this reason, Dr. Ahmed and coinvestigators performed a Cox multivariate regression analysis adjusted extensively for potential confounders, including age, sex, race, cardiovascular risk factors, known coronary artery disease, the use of cardiovascular medications, and the reason for the referral for stress testing.

When an achieved MET below 6 was used as the reference standard, for every 1 MET above 6 that patients achieved, their adjusted risk of all-cause mortality decreased by 18%, and the risk of nonfatal MI fell by 8%.

Session cochair Martin Halle, MD, pointed out what he viewed as a major limitation of the study.

“You didn’t follow their physical fitness over time, so you can’t say that increasing their METs would bring a better prognosis,” said Dr. Halle, professor and chairman of the department of preventive and rehabilitative sports medicine at the Technical University of Munich.

Dr. Ahmed reported having no financial conflicts of interest related to the Henry Ford FIT Project.

ROME – Cardiorespiratory fitness provided strong and graded protection against all-cause mortality and nonfatal MI in a study of more than 5,000 patients treated for depression, Amjad M. Ahmed, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

“These results highlight the importance of assessing fitness to identify risk as well as promoting an active lifestyle in patients with depression,” said Dr. Ahmed of Abdulaziz University for Health Sciences in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

This analysis focused on the 5,128 subjects who were on antidepressant medication at the time of their treadmill test. Their baseline cardiorespiratory fitness, as estimated by achieved peak metabolic equivalents (METs) on the treadmill, varied inversely with their risks of acute MI and all-cause mortality in the years to come. However, the less fit a patient was, the greater the burden of traditional cardiovascular risk factors. For example, the prevalence of hypertension was 86% in patients who achieved fewer than 6 METs, 75% in those who achieved 6-9 METs, 62% in depressed patients who reached 10-11 METs, and 51% in those who achieved 12 METs or more.

For this reason, Dr. Ahmed and coinvestigators performed a Cox multivariate regression analysis adjusted extensively for potential confounders, including age, sex, race, cardiovascular risk factors, known coronary artery disease, the use of cardiovascular medications, and the reason for the referral for stress testing.

When an achieved MET below 6 was used as the reference standard, for every 1 MET above 6 that patients achieved, their adjusted risk of all-cause mortality decreased by 18%, and the risk of nonfatal MI fell by 8%.

Session cochair Martin Halle, MD, pointed out what he viewed as a major limitation of the study.

“You didn’t follow their physical fitness over time, so you can’t say that increasing their METs would bring a better prognosis,” said Dr. Halle, professor and chairman of the department of preventive and rehabilitative sports medicine at the Technical University of Munich.

Dr. Ahmed reported having no financial conflicts of interest related to the Henry Ford FIT Project.

ROME – Cardiorespiratory fitness provided strong and graded protection against all-cause mortality and nonfatal MI in a study of more than 5,000 patients treated for depression, Amjad M. Ahmed, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

“These results highlight the importance of assessing fitness to identify risk as well as promoting an active lifestyle in patients with depression,” said Dr. Ahmed of Abdulaziz University for Health Sciences in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

This analysis focused on the 5,128 subjects who were on antidepressant medication at the time of their treadmill test. Their baseline cardiorespiratory fitness, as estimated by achieved peak metabolic equivalents (METs) on the treadmill, varied inversely with their risks of acute MI and all-cause mortality in the years to come. However, the less fit a patient was, the greater the burden of traditional cardiovascular risk factors. For example, the prevalence of hypertension was 86% in patients who achieved fewer than 6 METs, 75% in those who achieved 6-9 METs, 62% in depressed patients who reached 10-11 METs, and 51% in those who achieved 12 METs or more.

For this reason, Dr. Ahmed and coinvestigators performed a Cox multivariate regression analysis adjusted extensively for potential confounders, including age, sex, race, cardiovascular risk factors, known coronary artery disease, the use of cardiovascular medications, and the reason for the referral for stress testing.

When an achieved MET below 6 was used as the reference standard, for every 1 MET above 6 that patients achieved, their adjusted risk of all-cause mortality decreased by 18%, and the risk of nonfatal MI fell by 8%.

Session cochair Martin Halle, MD, pointed out what he viewed as a major limitation of the study.

“You didn’t follow their physical fitness over time, so you can’t say that increasing their METs would bring a better prognosis,” said Dr. Halle, professor and chairman of the department of preventive and rehabilitative sports medicine at the Technical University of Munich.

Dr. Ahmed reported having no financial conflicts of interest related to the Henry Ford FIT Project.

AT THE ESC CONGRESS 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: For every 1-MET increase a patient on antidepressant medication achieved above 6 METs during a Bruce protocol treadmill exercise test, the risk of all-cause mortality during the subsequent 11.5 years decreased by an adjusted 18%.

Data source: A retrospective analysis of 5,128 patients on antidepressant medication who underwent a treadmill exercise test as part of the Henry Ford Exercise Testing Project and were then followed up for a median of 11.5 years.

Disclosures: The study presenter reported having no relevant financial conflicts.

Scoring formula consolidates stroke, bleeding risk in atrial fib patients

ROME – A new risk-stratification formula for atrial fibrillation patients starting oral anticoagulant therapy helps sort out their potential net benefit on edoxaban, compared with warfarin.

This risk score “could help guide selection of treatment” with a vitamin K antagonist such as warfarin or a new oral anticoagulant (NOAC) such as edoxaban, Christina L. Fanola, MD, said at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

“It’s a great time to think about this type of score, because so many more patients are being diagnosed with atrial fibrillation and there is a lot of clinical equipoise” over which anticoagulant to start patients on, said Dr. Fanola, a cardiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. She said she and her associates hope to externally validate the score and test it in cohorts that received other NOACs, such as apixaban (Eliquis), dabigatran (Pradaxa), or rivaroxaban (Xarelto), but it is very possible that scoring might differ from one NOAC to the next. “Each NOAC may need its own scoring formula,” Dr. Fanola said in an interview.

A Cox proportional hazards model identified 10 demographic, clinical, and laboratory features that had significant, independent correlations to a primary outcome of disabling stroke, life-threatening bleeding, or death. After weighing the point allocation for each item by the strength of its association, the researchers developed a scoring formula in a model that could account for about 69% of the three combined adverse outcomes.

An analysis that applied the scoring formula back to the ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 database showed that a low-risk score of 0-6 correlated with a 4% per year rate of disabling stroke, life-threatening bleed, or death; an intermediate-risk score of 7-9 correlated with a 10% per year incidence of this combined outcome, and a high-risk score of 10 or greater linked with a 21% annual event rate.

Dr. Fanola and her associates ran a further analysis that evaluated the efficacy of edoxaban, compared with warfarin, among the patients in each of these risk strata. The high-risk patients received a major benefit from edoxaban, with a 30% overall incidence of the combined endpoint during 3 years of follow-up, compared with a 51% rate among patients on warfarin, a 21-percentage-point reduction in adverse events. Intermediate-risk patients also received a significant benefit, with a 26% event rate on warfarin and an 18% rate on edoxaban. But low-risk patients had identical 10% event rates with either treatment.

These findings suggest that atrial fibrillation patients with a TIMI AF score that is high or intermediate would have a better chance for a good outcome on edoxaban, or perhaps a different NOAC, than on warfarin. Low-risk patients seem to have similar outcomes on edoxaban or warfarin, so other considerations can come into play for choosing between these drug options, such as the cost of treatment and the inconvenience of regular warfarin monitoring, Dr. Fanola said.

ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 was sponsored by Daiichi Sankyo, the company that markets edoxaban. Dr. Fanola had no relevant financial disclosures.

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

ROME – A new risk-stratification formula for atrial fibrillation patients starting oral anticoagulant therapy helps sort out their potential net benefit on edoxaban, compared with warfarin.

This risk score “could help guide selection of treatment” with a vitamin K antagonist such as warfarin or a new oral anticoagulant (NOAC) such as edoxaban, Christina L. Fanola, MD, said at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

“It’s a great time to think about this type of score, because so many more patients are being diagnosed with atrial fibrillation and there is a lot of clinical equipoise” over which anticoagulant to start patients on, said Dr. Fanola, a cardiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. She said she and her associates hope to externally validate the score and test it in cohorts that received other NOACs, such as apixaban (Eliquis), dabigatran (Pradaxa), or rivaroxaban (Xarelto), but it is very possible that scoring might differ from one NOAC to the next. “Each NOAC may need its own scoring formula,” Dr. Fanola said in an interview.

A Cox proportional hazards model identified 10 demographic, clinical, and laboratory features that had significant, independent correlations to a primary outcome of disabling stroke, life-threatening bleeding, or death. After weighing the point allocation for each item by the strength of its association, the researchers developed a scoring formula in a model that could account for about 69% of the three combined adverse outcomes.

An analysis that applied the scoring formula back to the ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 database showed that a low-risk score of 0-6 correlated with a 4% per year rate of disabling stroke, life-threatening bleed, or death; an intermediate-risk score of 7-9 correlated with a 10% per year incidence of this combined outcome, and a high-risk score of 10 or greater linked with a 21% annual event rate.

Dr. Fanola and her associates ran a further analysis that evaluated the efficacy of edoxaban, compared with warfarin, among the patients in each of these risk strata. The high-risk patients received a major benefit from edoxaban, with a 30% overall incidence of the combined endpoint during 3 years of follow-up, compared with a 51% rate among patients on warfarin, a 21-percentage-point reduction in adverse events. Intermediate-risk patients also received a significant benefit, with a 26% event rate on warfarin and an 18% rate on edoxaban. But low-risk patients had identical 10% event rates with either treatment.

These findings suggest that atrial fibrillation patients with a TIMI AF score that is high or intermediate would have a better chance for a good outcome on edoxaban, or perhaps a different NOAC, than on warfarin. Low-risk patients seem to have similar outcomes on edoxaban or warfarin, so other considerations can come into play for choosing between these drug options, such as the cost of treatment and the inconvenience of regular warfarin monitoring, Dr. Fanola said.

ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 was sponsored by Daiichi Sankyo, the company that markets edoxaban. Dr. Fanola had no relevant financial disclosures.

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

ROME – A new risk-stratification formula for atrial fibrillation patients starting oral anticoagulant therapy helps sort out their potential net benefit on edoxaban, compared with warfarin.

This risk score “could help guide selection of treatment” with a vitamin K antagonist such as warfarin or a new oral anticoagulant (NOAC) such as edoxaban, Christina L. Fanola, MD, said at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

“It’s a great time to think about this type of score, because so many more patients are being diagnosed with atrial fibrillation and there is a lot of clinical equipoise” over which anticoagulant to start patients on, said Dr. Fanola, a cardiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. She said she and her associates hope to externally validate the score and test it in cohorts that received other NOACs, such as apixaban (Eliquis), dabigatran (Pradaxa), or rivaroxaban (Xarelto), but it is very possible that scoring might differ from one NOAC to the next. “Each NOAC may need its own scoring formula,” Dr. Fanola said in an interview.

A Cox proportional hazards model identified 10 demographic, clinical, and laboratory features that had significant, independent correlations to a primary outcome of disabling stroke, life-threatening bleeding, or death. After weighing the point allocation for each item by the strength of its association, the researchers developed a scoring formula in a model that could account for about 69% of the three combined adverse outcomes.

An analysis that applied the scoring formula back to the ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 database showed that a low-risk score of 0-6 correlated with a 4% per year rate of disabling stroke, life-threatening bleed, or death; an intermediate-risk score of 7-9 correlated with a 10% per year incidence of this combined outcome, and a high-risk score of 10 or greater linked with a 21% annual event rate.

Dr. Fanola and her associates ran a further analysis that evaluated the efficacy of edoxaban, compared with warfarin, among the patients in each of these risk strata. The high-risk patients received a major benefit from edoxaban, with a 30% overall incidence of the combined endpoint during 3 years of follow-up, compared with a 51% rate among patients on warfarin, a 21-percentage-point reduction in adverse events. Intermediate-risk patients also received a significant benefit, with a 26% event rate on warfarin and an 18% rate on edoxaban. But low-risk patients had identical 10% event rates with either treatment.

These findings suggest that atrial fibrillation patients with a TIMI AF score that is high or intermediate would have a better chance for a good outcome on edoxaban, or perhaps a different NOAC, than on warfarin. Low-risk patients seem to have similar outcomes on edoxaban or warfarin, so other considerations can come into play for choosing between these drug options, such as the cost of treatment and the inconvenience of regular warfarin monitoring, Dr. Fanola said.

ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 was sponsored by Daiichi Sankyo, the company that markets edoxaban. Dr. Fanola had no relevant financial disclosures.

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT THE ESC CONGRESS 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Among high-risk patients, edoxaban cut adverse events by 21 percentage points, compared with warfarin.

Data source: ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48, a multicenter trial with 21,105 patients.

Disclosures: ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 was sponsored by Daiichi Sankyo, the company that markets edoxaban (Savaysa). Dr. Fanola had no relevant financial disclosures.

Carotid stenting tied to cardiovascular events in real-world study

ROME – Carotid stenting was associated with a roughly 30% higher risk of cardiovascular events than that of carotid endarterectomy during 12 years of follow-up in a large, real-world, population-based cohort study, Mohamad A. Hussain, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

“Our data raise concerns about the external validity of randomized controlled trials of carotid endarterectomy versus stenting and question the potential interchangeability of carotid endarterectomy and stenting as stated in clinical practice guidelines,” said Dr. Hussain of the University of Toronto.

Major practice guidelines cite randomized trial evidence in suggesting that CEA and stenting can be used interchangeably in treating low- or average-risk patients with significant carotid artery disease. Dr. Hussain and his coinvestigators, suspicious that the generalizability of the randomized trial findings may be limited because of operator and institutional selection bias, decided to conduct a retrospective cohort study of all patients over age 40 years who underwent CEA or carotid stenting in the province of Ontario from April 2002 through March 2013.

Using validated chart abstraction software, they identified 12,529 patients who had CEA and 1,935 with carotid stenting. The two groups were similar in terms of most baseline characteristics. Notably, however, stent recipients were significantly more likely to have symptomatic carotid disease and also had more comorbid conditions as reflected in a higher Charlson Comorbidity Index score.

The primary outcome in the study was the 12-year rate of a composite comprising ischemic stroke, transient ischemic attack (TIA), MI, or death. The rate was 35.4% in the CEA group and 44.5% in the stent group. After adjustment for the baseline differences, the stent group still had a statistically significant 28% greater risk of the primary outcome.

“We found the difference remained significant in all of our subgroup analyses, regardless of age, sex, year of procedure, symptomatic or asymptomatic carotid artery disease, CAD [coronary artery disease] or no CAD, diabetes (type 1 or 2) or no diabetes. Outcomes with endarterectomy were always significantly better,” said Dr. Hussain.

“I think our study shows that in clinical practice we’re not quite seeing the outcomes reported in the clinical trials,” he added.

As for the individual components of the composite endpoint, the 12-year rate of ischemic stroke or TIA was 9% in the CEA group and 14% with stenting, for an adjusted 40% increased risk in the stent group. The 12-year all-cause mortality rate was 26% in the CEA group and 34% with stenting, for an adjusted 28% increased risk. The incidence of MI was 8% in both groups.

The investigators next conducted a confirmatory propensity-matched analysis in which 1,927 of the stented patients were closely matched to 3,844 surgical patients, eliminating baseline differences in the prevalence of symptomatic carotid artery disease and other disparities. In this matched cohort, the primary outcome occurred in 37.4% of the CEA group and 44.3% of stent patients, for an adjusted 32% increase in risk in the stented group.

The differences in outcome were driven by sharply higher periprocedural risk in the stented group. After the periprocedural period, the outcome curves remained parallel in the two treatment groups.

In that first 30 days post procedure, the primary composite outcome occurred in 5.4% of the CEA group and 10% of stented patients, for an adjusted 40% increase in relative risk in percutaneously treated patients. The 30-day rate of ischemic stroke or TIA was 3.4% in the surgical group compared with 6.4% in stented patients. Thirty-day mortality was 0.9% with CEA versus 3.3% with stenting.

Asked by the award panel for his thoughts on the disparity between the results of his real-world study and the major randomized trials of CEA versus stenting, Dr. Hussain replied, “It may be because the trials had high-volume operators at high-volume centers who are really experts in carotid stenting, while in the real world many physicians may not be selecting the right people for carotid stenting.”

Differences in sample size may also figure in the disparity, he continued. He noted that in the recent 10-year report from the Carotid Revascularization Endarterectomy versus Stenting Trial (CREST), the composite endpoint of stroke, MI, or death occurred in 9.9% of the CEA group compared with 11.8% of the stenting group (N Engl J Med. 2016 Mar 17;374[11]:1021-31), but this difference in favor of CEA didn’t achieve statistical significance because of the wide confidence intervals resulting from a smaller sample size than in the Ontario study.

Looking to the future, Dr. Hussain said he thinks the ongoing CREST-2 trial is “very important.” It is randomizing patients with asymptomatic high-grade carotid stenosis to uniform intensive medical management either alone or in combination with CEA or stenting with embolic protection.

“That study might end up showing us that medical therapy is as good as or even better than stenting or CEA, especially in asymptomatic patients,” he said.

Dr. Hussain reported having no financial conflicts regarding his academically funded study.

ROME – Carotid stenting was associated with a roughly 30% higher risk of cardiovascular events than that of carotid endarterectomy during 12 years of follow-up in a large, real-world, population-based cohort study, Mohamad A. Hussain, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

“Our data raise concerns about the external validity of randomized controlled trials of carotid endarterectomy versus stenting and question the potential interchangeability of carotid endarterectomy and stenting as stated in clinical practice guidelines,” said Dr. Hussain of the University of Toronto.

Major practice guidelines cite randomized trial evidence in suggesting that CEA and stenting can be used interchangeably in treating low- or average-risk patients with significant carotid artery disease. Dr. Hussain and his coinvestigators, suspicious that the generalizability of the randomized trial findings may be limited because of operator and institutional selection bias, decided to conduct a retrospective cohort study of all patients over age 40 years who underwent CEA or carotid stenting in the province of Ontario from April 2002 through March 2013.

Using validated chart abstraction software, they identified 12,529 patients who had CEA and 1,935 with carotid stenting. The two groups were similar in terms of most baseline characteristics. Notably, however, stent recipients were significantly more likely to have symptomatic carotid disease and also had more comorbid conditions as reflected in a higher Charlson Comorbidity Index score.

The primary outcome in the study was the 12-year rate of a composite comprising ischemic stroke, transient ischemic attack (TIA), MI, or death. The rate was 35.4% in the CEA group and 44.5% in the stent group. After adjustment for the baseline differences, the stent group still had a statistically significant 28% greater risk of the primary outcome.

“We found the difference remained significant in all of our subgroup analyses, regardless of age, sex, year of procedure, symptomatic or asymptomatic carotid artery disease, CAD [coronary artery disease] or no CAD, diabetes (type 1 or 2) or no diabetes. Outcomes with endarterectomy were always significantly better,” said Dr. Hussain.

“I think our study shows that in clinical practice we’re not quite seeing the outcomes reported in the clinical trials,” he added.

As for the individual components of the composite endpoint, the 12-year rate of ischemic stroke or TIA was 9% in the CEA group and 14% with stenting, for an adjusted 40% increased risk in the stent group. The 12-year all-cause mortality rate was 26% in the CEA group and 34% with stenting, for an adjusted 28% increased risk. The incidence of MI was 8% in both groups.

The investigators next conducted a confirmatory propensity-matched analysis in which 1,927 of the stented patients were closely matched to 3,844 surgical patients, eliminating baseline differences in the prevalence of symptomatic carotid artery disease and other disparities. In this matched cohort, the primary outcome occurred in 37.4% of the CEA group and 44.3% of stent patients, for an adjusted 32% increase in risk in the stented group.

The differences in outcome were driven by sharply higher periprocedural risk in the stented group. After the periprocedural period, the outcome curves remained parallel in the two treatment groups.

In that first 30 days post procedure, the primary composite outcome occurred in 5.4% of the CEA group and 10% of stented patients, for an adjusted 40% increase in relative risk in percutaneously treated patients. The 30-day rate of ischemic stroke or TIA was 3.4% in the surgical group compared with 6.4% in stented patients. Thirty-day mortality was 0.9% with CEA versus 3.3% with stenting.

Asked by the award panel for his thoughts on the disparity between the results of his real-world study and the major randomized trials of CEA versus stenting, Dr. Hussain replied, “It may be because the trials had high-volume operators at high-volume centers who are really experts in carotid stenting, while in the real world many physicians may not be selecting the right people for carotid stenting.”

Differences in sample size may also figure in the disparity, he continued. He noted that in the recent 10-year report from the Carotid Revascularization Endarterectomy versus Stenting Trial (CREST), the composite endpoint of stroke, MI, or death occurred in 9.9% of the CEA group compared with 11.8% of the stenting group (N Engl J Med. 2016 Mar 17;374[11]:1021-31), but this difference in favor of CEA didn’t achieve statistical significance because of the wide confidence intervals resulting from a smaller sample size than in the Ontario study.

Looking to the future, Dr. Hussain said he thinks the ongoing CREST-2 trial is “very important.” It is randomizing patients with asymptomatic high-grade carotid stenosis to uniform intensive medical management either alone or in combination with CEA or stenting with embolic protection.

“That study might end up showing us that medical therapy is as good as or even better than stenting or CEA, especially in asymptomatic patients,” he said.

Dr. Hussain reported having no financial conflicts regarding his academically funded study.

ROME – Carotid stenting was associated with a roughly 30% higher risk of cardiovascular events than that of carotid endarterectomy during 12 years of follow-up in a large, real-world, population-based cohort study, Mohamad A. Hussain, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

“Our data raise concerns about the external validity of randomized controlled trials of carotid endarterectomy versus stenting and question the potential interchangeability of carotid endarterectomy and stenting as stated in clinical practice guidelines,” said Dr. Hussain of the University of Toronto.

Major practice guidelines cite randomized trial evidence in suggesting that CEA and stenting can be used interchangeably in treating low- or average-risk patients with significant carotid artery disease. Dr. Hussain and his coinvestigators, suspicious that the generalizability of the randomized trial findings may be limited because of operator and institutional selection bias, decided to conduct a retrospective cohort study of all patients over age 40 years who underwent CEA or carotid stenting in the province of Ontario from April 2002 through March 2013.

Using validated chart abstraction software, they identified 12,529 patients who had CEA and 1,935 with carotid stenting. The two groups were similar in terms of most baseline characteristics. Notably, however, stent recipients were significantly more likely to have symptomatic carotid disease and also had more comorbid conditions as reflected in a higher Charlson Comorbidity Index score.

The primary outcome in the study was the 12-year rate of a composite comprising ischemic stroke, transient ischemic attack (TIA), MI, or death. The rate was 35.4% in the CEA group and 44.5% in the stent group. After adjustment for the baseline differences, the stent group still had a statistically significant 28% greater risk of the primary outcome.

“We found the difference remained significant in all of our subgroup analyses, regardless of age, sex, year of procedure, symptomatic or asymptomatic carotid artery disease, CAD [coronary artery disease] or no CAD, diabetes (type 1 or 2) or no diabetes. Outcomes with endarterectomy were always significantly better,” said Dr. Hussain.

“I think our study shows that in clinical practice we’re not quite seeing the outcomes reported in the clinical trials,” he added.

As for the individual components of the composite endpoint, the 12-year rate of ischemic stroke or TIA was 9% in the CEA group and 14% with stenting, for an adjusted 40% increased risk in the stent group. The 12-year all-cause mortality rate was 26% in the CEA group and 34% with stenting, for an adjusted 28% increased risk. The incidence of MI was 8% in both groups.