User login

Ezetimibe’s ACS benefit centers on high-risk, post-CABG patients

ROME – Patients who have undergone coronary artery bypass surgery and who later have an acute coronary syndrome event gain the most from an aggressive lipid-lowering regimen, according to an exploratory analysis of data from more than 18,000 patients enrolled in the IMPROVE-IT trial that tested the incremental benefit from ezetimibe treatment when added to a statin.

Additional exploratory analyses further showed that high-risk acute coronary syndrome (ACS) patients without a history of coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) also benefited from adding ezetimibe to a background regimen of simvastatin, but the benefit from adding ezetimibe completely disappeared in low-risk ACS patients, Alon Eisen, MD, said at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

‘The benefit of adding ezetimibe to a statin was enhanced in patients with prior CABG and in other high-risk patients with no prior CABG, supporting the use of more intensive lipid-lowering therapy in these high-risk patients,” said Dr. Eisen, a cardiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. He also highlighted that ezetimibe is “a safe drug that is coming off patent.” Adding ezetimibe had a moderate effect on LDL cholesterol levels, cutting them from a median of 70 mg/dL in patients in the placebo arm to a median of 54 mg/dL in the group who received ezetimibe.

These results “show that if we pick the right patients, a very benign drug can have a great benefit,” said Eugene Braunwald, MD, a coinvestigator on the IMPROVE-IT trial and a collaborator with Dr. Eisen on the new analysis. The new findings “emphasize that the higher a patient’s risk, the more effect they get from cholesterol-lowering treatment,” said Dr. Braunwald, professor of medicine at Harvard University and a cardiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, both in Boston.

The second exploratory analysis reported by Dr. Eisen looked at the more than 16,000 patients in IMPROVE-IT without history of CABG. The analysis applied a newly developed, nine-item formula for stratifying atherothrombotic risk (Circulation. 2016 July 26;134[4];304-13) to divide these patients into low-, intermediate- and high-risk subgroups. Patients in the high-risk subgroup (20% of the IMPROVE-IT subgroup) had a 6–percentage point reduction in their primary endpoint event rate with added ezetimibe treatment, while those at intermediate risk (31%) got a 2–percentage point decrease in endpoint events, and low-risk patients (49%) actually showed a small, less than 1–percentage point increase in endpoint events with added ezetimibe, Dr. Eisen reported.

IMPROVE-IT was funded by MERCK, the company that markets ezetimibe (Zetia). Dr. Eisen had no disclosures. Dr. Braunwald has been a consultant to Merck as well as to Bayer, Daiichi Sankyo, The Medicines Company, Novartis, and Sanofi.

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

I suspect that the patients in IMPROVE-IT with a history of coronary artery bypass graft surgery were more likely than the other enrolled acute coronary syndrome patients to have more extensive and systemic atherosclerotic disease. Although coronary artery bypass addresses the most acute obstructions to coronary flow that exist at the time of surgery, the procedure does not cure the patient’s underlying vascular disease. We know that a substantial majority of coronary events occur in arteries that are not heavily stenosed.

Another important limitation to keep in mind about the IMPROVE-IT trial was that the background statin treatment all patients received was modest – 40 mg of simvastatin daily. In real-world practice, high-risk patients should go on the most potent statin regimen they can tolerate – ideally, 40 mg daily of rosuvastatin. The need for additional lipid-lowering interventions, with ezetimibe or other drugs, can then be considered as an add-on to aggressive statin therapy.

Richard A. Chazal, MD, is an invasive cardiologist and medical director of the Heart and Vascular Institute of Lee Memorial Health System in Fort Myers, Fla. He is also the current president of the American College of Cardiology. He had no disclosures. He made these comments in an interview.

I suspect that the patients in IMPROVE-IT with a history of coronary artery bypass graft surgery were more likely than the other enrolled acute coronary syndrome patients to have more extensive and systemic atherosclerotic disease. Although coronary artery bypass addresses the most acute obstructions to coronary flow that exist at the time of surgery, the procedure does not cure the patient’s underlying vascular disease. We know that a substantial majority of coronary events occur in arteries that are not heavily stenosed.

Another important limitation to keep in mind about the IMPROVE-IT trial was that the background statin treatment all patients received was modest – 40 mg of simvastatin daily. In real-world practice, high-risk patients should go on the most potent statin regimen they can tolerate – ideally, 40 mg daily of rosuvastatin. The need for additional lipid-lowering interventions, with ezetimibe or other drugs, can then be considered as an add-on to aggressive statin therapy.

Richard A. Chazal, MD, is an invasive cardiologist and medical director of the Heart and Vascular Institute of Lee Memorial Health System in Fort Myers, Fla. He is also the current president of the American College of Cardiology. He had no disclosures. He made these comments in an interview.

I suspect that the patients in IMPROVE-IT with a history of coronary artery bypass graft surgery were more likely than the other enrolled acute coronary syndrome patients to have more extensive and systemic atherosclerotic disease. Although coronary artery bypass addresses the most acute obstructions to coronary flow that exist at the time of surgery, the procedure does not cure the patient’s underlying vascular disease. We know that a substantial majority of coronary events occur in arteries that are not heavily stenosed.

Another important limitation to keep in mind about the IMPROVE-IT trial was that the background statin treatment all patients received was modest – 40 mg of simvastatin daily. In real-world practice, high-risk patients should go on the most potent statin regimen they can tolerate – ideally, 40 mg daily of rosuvastatin. The need for additional lipid-lowering interventions, with ezetimibe or other drugs, can then be considered as an add-on to aggressive statin therapy.

Richard A. Chazal, MD, is an invasive cardiologist and medical director of the Heart and Vascular Institute of Lee Memorial Health System in Fort Myers, Fla. He is also the current president of the American College of Cardiology. He had no disclosures. He made these comments in an interview.

ROME – Patients who have undergone coronary artery bypass surgery and who later have an acute coronary syndrome event gain the most from an aggressive lipid-lowering regimen, according to an exploratory analysis of data from more than 18,000 patients enrolled in the IMPROVE-IT trial that tested the incremental benefit from ezetimibe treatment when added to a statin.

Additional exploratory analyses further showed that high-risk acute coronary syndrome (ACS) patients without a history of coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) also benefited from adding ezetimibe to a background regimen of simvastatin, but the benefit from adding ezetimibe completely disappeared in low-risk ACS patients, Alon Eisen, MD, said at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

‘The benefit of adding ezetimibe to a statin was enhanced in patients with prior CABG and in other high-risk patients with no prior CABG, supporting the use of more intensive lipid-lowering therapy in these high-risk patients,” said Dr. Eisen, a cardiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. He also highlighted that ezetimibe is “a safe drug that is coming off patent.” Adding ezetimibe had a moderate effect on LDL cholesterol levels, cutting them from a median of 70 mg/dL in patients in the placebo arm to a median of 54 mg/dL in the group who received ezetimibe.

These results “show that if we pick the right patients, a very benign drug can have a great benefit,” said Eugene Braunwald, MD, a coinvestigator on the IMPROVE-IT trial and a collaborator with Dr. Eisen on the new analysis. The new findings “emphasize that the higher a patient’s risk, the more effect they get from cholesterol-lowering treatment,” said Dr. Braunwald, professor of medicine at Harvard University and a cardiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, both in Boston.

The second exploratory analysis reported by Dr. Eisen looked at the more than 16,000 patients in IMPROVE-IT without history of CABG. The analysis applied a newly developed, nine-item formula for stratifying atherothrombotic risk (Circulation. 2016 July 26;134[4];304-13) to divide these patients into low-, intermediate- and high-risk subgroups. Patients in the high-risk subgroup (20% of the IMPROVE-IT subgroup) had a 6–percentage point reduction in their primary endpoint event rate with added ezetimibe treatment, while those at intermediate risk (31%) got a 2–percentage point decrease in endpoint events, and low-risk patients (49%) actually showed a small, less than 1–percentage point increase in endpoint events with added ezetimibe, Dr. Eisen reported.

IMPROVE-IT was funded by MERCK, the company that markets ezetimibe (Zetia). Dr. Eisen had no disclosures. Dr. Braunwald has been a consultant to Merck as well as to Bayer, Daiichi Sankyo, The Medicines Company, Novartis, and Sanofi.

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

ROME – Patients who have undergone coronary artery bypass surgery and who later have an acute coronary syndrome event gain the most from an aggressive lipid-lowering regimen, according to an exploratory analysis of data from more than 18,000 patients enrolled in the IMPROVE-IT trial that tested the incremental benefit from ezetimibe treatment when added to a statin.

Additional exploratory analyses further showed that high-risk acute coronary syndrome (ACS) patients without a history of coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) also benefited from adding ezetimibe to a background regimen of simvastatin, but the benefit from adding ezetimibe completely disappeared in low-risk ACS patients, Alon Eisen, MD, said at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

‘The benefit of adding ezetimibe to a statin was enhanced in patients with prior CABG and in other high-risk patients with no prior CABG, supporting the use of more intensive lipid-lowering therapy in these high-risk patients,” said Dr. Eisen, a cardiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. He also highlighted that ezetimibe is “a safe drug that is coming off patent.” Adding ezetimibe had a moderate effect on LDL cholesterol levels, cutting them from a median of 70 mg/dL in patients in the placebo arm to a median of 54 mg/dL in the group who received ezetimibe.

These results “show that if we pick the right patients, a very benign drug can have a great benefit,” said Eugene Braunwald, MD, a coinvestigator on the IMPROVE-IT trial and a collaborator with Dr. Eisen on the new analysis. The new findings “emphasize that the higher a patient’s risk, the more effect they get from cholesterol-lowering treatment,” said Dr. Braunwald, professor of medicine at Harvard University and a cardiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, both in Boston.

The second exploratory analysis reported by Dr. Eisen looked at the more than 16,000 patients in IMPROVE-IT without history of CABG. The analysis applied a newly developed, nine-item formula for stratifying atherothrombotic risk (Circulation. 2016 July 26;134[4];304-13) to divide these patients into low-, intermediate- and high-risk subgroups. Patients in the high-risk subgroup (20% of the IMPROVE-IT subgroup) had a 6–percentage point reduction in their primary endpoint event rate with added ezetimibe treatment, while those at intermediate risk (31%) got a 2–percentage point decrease in endpoint events, and low-risk patients (49%) actually showed a small, less than 1–percentage point increase in endpoint events with added ezetimibe, Dr. Eisen reported.

IMPROVE-IT was funded by MERCK, the company that markets ezetimibe (Zetia). Dr. Eisen had no disclosures. Dr. Braunwald has been a consultant to Merck as well as to Bayer, Daiichi Sankyo, The Medicines Company, Novartis, and Sanofi.

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT THE ESC CONGRESS 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The absolute primary-event risk reduction was 9% in post-CABG patients and 1% in all other patients.

Data source: An exploratory, post-hoc analysis of data collected in IMPROVE-IT, a multicenter trial with 18,144 patients.

Disclosures: IMPROVE-IT was funded by MERCK, the company that markets ezetimibe (Zetia). Dr. Eisen had no disclosures. Dr. Braunwald has been a consultant to Merck as well as to Bayer, Daiichi Sankyo, The Medicines Company, Novartis, and Sanofi.

Joint European atrial fibrillation guidelines break new ground

ROME – The 2016 joint European guidelines on management of atrial fibrillation break new ground by declaring as a strong Class IA recommendation that the novel oral anticoagulants are now the drugs of choice – preferred over warfarin – for stroke prevention.

The joint guidelines from the European Society of Cardiology and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery recommend that warfarin’s use be reserved for the relatively small proportion of atrial fibrillation (AF) patients who are ineligible for the four commercially available novel oral anticoagulants (NOACs). That’s mainly patients with mechanical heart valves, moderate to severe mitral stenosis, or severe chronic kidney disease.

The ESC/EACTS guidelines, taken together with the American College of Chest Physicians guidelines on antithrombotic therapy for venous thromboembolic disease released earlier in the year, suggest that the old war horse warfarin is being eased out to pasture. The ACCP guidelines recommend any of the four NOACS – apixaban, dabigatran, edoxaban, or rivaroxaban – be used preferentially over warfarin in the treatment of venous thromboembolism (Chest 2016 Feb;149[2]:315-52). Both sets of guidelines cite compelling evidence that the NOACs are significantly safer than warfarin yet equally effective.

The ESC/EACTS guidelines are a full rewrite containing numerous departures from the previous 2012 AF management guidelines as well as from current ACC/AHA guidelines. The report includes more than 1,000 references. Eighty percent of the 154 recommendations provide Class I or IIa guidance. Two-thirds of the recommendations are Level of Evidence A or B, task force chairperson Paulus Kirchhof, MD, said at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

He and co-chairperson Stefano Benussi, MD, presented some of the highlights.

The guidelines issue a strong call for greater use of targeted ECG screening in populations at risk for silent AF, including stroke survivors and the elderly. And AF should always be documented before starting treatment, given that all of the treatments carry risk, said Dr. Kirchhof, professor of cardiovascular medicine at the University of Birmingham (England).

Once the diagnosis is established, it’s essential to address in a structured way five domains of management: acute rate and rhythm control; management of precipitating factors, including underlying cardiovascular conditions such as hypertension or valvular heart disease; assessment of stroke risk using the CHA2DS2-VASc scoring system; assessment of heart rate; and evaluation of the impact of AF symptoms on the patient’s life, including fatigue and breathlessness, using a structured instrument such as the modified European Heart Rhythm Association symptom scale.

Men with a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 1 and women with a score of 2 should be considered for anticoagulation. And the treatment should be recommended – not merely considered – for men with a score of 2 or more and women with a score of 3; that’s a Class Ia recommendation, Dr. Kirchhof continued.

The use of a specific bleeding risk score is no longer recommended in AF patients on oral anticoagulation. The emphasis has shifted to reduction of modifiable bleeding risk factors, including limiting alcohol intake to fewer than 8 drinks per week, control of hypertension, and discontinuing antiplatelet and anti-inflammatory agents.

Consideration of left atrial appendage occlusion devices should be reserved for the small percentage of patients who have clear contraindications to all forms of oral anticoagulation.

The task force concluded that patients who have bleeding on oral anticoagulation can often be managed with local therapy and discontinuation of anticoagulation therapy for a day or two before resumption. However, decisions regarding resumption of a NOAC or warfarin after an intracranial bleed should be handled by an interdisciplinary panel composed of a stroke neurologist, a cardiologist, a neuroradiologist, and a neurosurgeon.

Evidence-based treatment options in patients with symptomatic AF after failed catheter ablation include minimally invasive surgery with epicardial pulmonary vein isolation, more extensive catheter ablation, and hybrid procedures, according to Dr. Benussi, who is codirector of clinical cardiovascular surgery at University Hospital in Zurich.

The guidelines state that the data supporting catheter ablation to achieve long-term rhythm control are now sufficiently strong that this intervention should be considered as a first-line option alongside antiarrhythmic drugs as a matter of patient preference in the setting of symptomatic paroxysmal AF regardless of whether the patient has CAD, heart failure, valvular heart disease, or no structural heart disease.

Catheter ablation using radiofrequency energy or cryoablation should target complete isolation of the pulmonary veins.

“Additional ablation lines do not provide demonstrable clinical benefit and increase the risk of postablation left atrial arrhythmias,” the surgeon said.

Maze surgery, preferably biatrial, received a favorable Class IIa, Level of Evidence A recommendation as worthy of consideration in patients with symptomatic AF who are already undergoing cardiac surgery. This recommendation was based upon an external review by the Cochrane group which was commissioned by the guidelines task force. The Cochrane review of eight published studies concluded that Maze surgery under such circumstances was associated with a twofold increased freedom from AF, atrial flutter, and atrial tachycardia (Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2016;8: CD012088. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012088.pub2).

The AF management guidelines are supported by the ESC Pocket Guidelines app, which includes an overall AF treatment manager developed by the European Union–funded CATCH ME (Characterizing Atrial Fibrillation by Translating its Causes Into Health Modifiers in the Elderly) project.

The multidisciplinary 17-member AF management task force was drawn from cardiology, stroke neurology, cardiac surgery, and specialist nursing. Dr. Kirchhof stressed that only recommendations supported by at least 75% of task force members made it into the guidelines (Eur Heart J. 2016 Aug 27. pii: ehw210. [Epub ahead of print] doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw210).

ROME – The 2016 joint European guidelines on management of atrial fibrillation break new ground by declaring as a strong Class IA recommendation that the novel oral anticoagulants are now the drugs of choice – preferred over warfarin – for stroke prevention.

The joint guidelines from the European Society of Cardiology and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery recommend that warfarin’s use be reserved for the relatively small proportion of atrial fibrillation (AF) patients who are ineligible for the four commercially available novel oral anticoagulants (NOACs). That’s mainly patients with mechanical heart valves, moderate to severe mitral stenosis, or severe chronic kidney disease.

The ESC/EACTS guidelines, taken together with the American College of Chest Physicians guidelines on antithrombotic therapy for venous thromboembolic disease released earlier in the year, suggest that the old war horse warfarin is being eased out to pasture. The ACCP guidelines recommend any of the four NOACS – apixaban, dabigatran, edoxaban, or rivaroxaban – be used preferentially over warfarin in the treatment of venous thromboembolism (Chest 2016 Feb;149[2]:315-52). Both sets of guidelines cite compelling evidence that the NOACs are significantly safer than warfarin yet equally effective.

The ESC/EACTS guidelines are a full rewrite containing numerous departures from the previous 2012 AF management guidelines as well as from current ACC/AHA guidelines. The report includes more than 1,000 references. Eighty percent of the 154 recommendations provide Class I or IIa guidance. Two-thirds of the recommendations are Level of Evidence A or B, task force chairperson Paulus Kirchhof, MD, said at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

He and co-chairperson Stefano Benussi, MD, presented some of the highlights.

The guidelines issue a strong call for greater use of targeted ECG screening in populations at risk for silent AF, including stroke survivors and the elderly. And AF should always be documented before starting treatment, given that all of the treatments carry risk, said Dr. Kirchhof, professor of cardiovascular medicine at the University of Birmingham (England).

Once the diagnosis is established, it’s essential to address in a structured way five domains of management: acute rate and rhythm control; management of precipitating factors, including underlying cardiovascular conditions such as hypertension or valvular heart disease; assessment of stroke risk using the CHA2DS2-VASc scoring system; assessment of heart rate; and evaluation of the impact of AF symptoms on the patient’s life, including fatigue and breathlessness, using a structured instrument such as the modified European Heart Rhythm Association symptom scale.

Men with a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 1 and women with a score of 2 should be considered for anticoagulation. And the treatment should be recommended – not merely considered – for men with a score of 2 or more and women with a score of 3; that’s a Class Ia recommendation, Dr. Kirchhof continued.

The use of a specific bleeding risk score is no longer recommended in AF patients on oral anticoagulation. The emphasis has shifted to reduction of modifiable bleeding risk factors, including limiting alcohol intake to fewer than 8 drinks per week, control of hypertension, and discontinuing antiplatelet and anti-inflammatory agents.

Consideration of left atrial appendage occlusion devices should be reserved for the small percentage of patients who have clear contraindications to all forms of oral anticoagulation.

The task force concluded that patients who have bleeding on oral anticoagulation can often be managed with local therapy and discontinuation of anticoagulation therapy for a day or two before resumption. However, decisions regarding resumption of a NOAC or warfarin after an intracranial bleed should be handled by an interdisciplinary panel composed of a stroke neurologist, a cardiologist, a neuroradiologist, and a neurosurgeon.

Evidence-based treatment options in patients with symptomatic AF after failed catheter ablation include minimally invasive surgery with epicardial pulmonary vein isolation, more extensive catheter ablation, and hybrid procedures, according to Dr. Benussi, who is codirector of clinical cardiovascular surgery at University Hospital in Zurich.

The guidelines state that the data supporting catheter ablation to achieve long-term rhythm control are now sufficiently strong that this intervention should be considered as a first-line option alongside antiarrhythmic drugs as a matter of patient preference in the setting of symptomatic paroxysmal AF regardless of whether the patient has CAD, heart failure, valvular heart disease, or no structural heart disease.

Catheter ablation using radiofrequency energy or cryoablation should target complete isolation of the pulmonary veins.

“Additional ablation lines do not provide demonstrable clinical benefit and increase the risk of postablation left atrial arrhythmias,” the surgeon said.

Maze surgery, preferably biatrial, received a favorable Class IIa, Level of Evidence A recommendation as worthy of consideration in patients with symptomatic AF who are already undergoing cardiac surgery. This recommendation was based upon an external review by the Cochrane group which was commissioned by the guidelines task force. The Cochrane review of eight published studies concluded that Maze surgery under such circumstances was associated with a twofold increased freedom from AF, atrial flutter, and atrial tachycardia (Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2016;8: CD012088. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012088.pub2).

The AF management guidelines are supported by the ESC Pocket Guidelines app, which includes an overall AF treatment manager developed by the European Union–funded CATCH ME (Characterizing Atrial Fibrillation by Translating its Causes Into Health Modifiers in the Elderly) project.

The multidisciplinary 17-member AF management task force was drawn from cardiology, stroke neurology, cardiac surgery, and specialist nursing. Dr. Kirchhof stressed that only recommendations supported by at least 75% of task force members made it into the guidelines (Eur Heart J. 2016 Aug 27. pii: ehw210. [Epub ahead of print] doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw210).

ROME – The 2016 joint European guidelines on management of atrial fibrillation break new ground by declaring as a strong Class IA recommendation that the novel oral anticoagulants are now the drugs of choice – preferred over warfarin – for stroke prevention.

The joint guidelines from the European Society of Cardiology and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery recommend that warfarin’s use be reserved for the relatively small proportion of atrial fibrillation (AF) patients who are ineligible for the four commercially available novel oral anticoagulants (NOACs). That’s mainly patients with mechanical heart valves, moderate to severe mitral stenosis, or severe chronic kidney disease.

The ESC/EACTS guidelines, taken together with the American College of Chest Physicians guidelines on antithrombotic therapy for venous thromboembolic disease released earlier in the year, suggest that the old war horse warfarin is being eased out to pasture. The ACCP guidelines recommend any of the four NOACS – apixaban, dabigatran, edoxaban, or rivaroxaban – be used preferentially over warfarin in the treatment of venous thromboembolism (Chest 2016 Feb;149[2]:315-52). Both sets of guidelines cite compelling evidence that the NOACs are significantly safer than warfarin yet equally effective.

The ESC/EACTS guidelines are a full rewrite containing numerous departures from the previous 2012 AF management guidelines as well as from current ACC/AHA guidelines. The report includes more than 1,000 references. Eighty percent of the 154 recommendations provide Class I or IIa guidance. Two-thirds of the recommendations are Level of Evidence A or B, task force chairperson Paulus Kirchhof, MD, said at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

He and co-chairperson Stefano Benussi, MD, presented some of the highlights.

The guidelines issue a strong call for greater use of targeted ECG screening in populations at risk for silent AF, including stroke survivors and the elderly. And AF should always be documented before starting treatment, given that all of the treatments carry risk, said Dr. Kirchhof, professor of cardiovascular medicine at the University of Birmingham (England).

Once the diagnosis is established, it’s essential to address in a structured way five domains of management: acute rate and rhythm control; management of precipitating factors, including underlying cardiovascular conditions such as hypertension or valvular heart disease; assessment of stroke risk using the CHA2DS2-VASc scoring system; assessment of heart rate; and evaluation of the impact of AF symptoms on the patient’s life, including fatigue and breathlessness, using a structured instrument such as the modified European Heart Rhythm Association symptom scale.

Men with a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 1 and women with a score of 2 should be considered for anticoagulation. And the treatment should be recommended – not merely considered – for men with a score of 2 or more and women with a score of 3; that’s a Class Ia recommendation, Dr. Kirchhof continued.

The use of a specific bleeding risk score is no longer recommended in AF patients on oral anticoagulation. The emphasis has shifted to reduction of modifiable bleeding risk factors, including limiting alcohol intake to fewer than 8 drinks per week, control of hypertension, and discontinuing antiplatelet and anti-inflammatory agents.

Consideration of left atrial appendage occlusion devices should be reserved for the small percentage of patients who have clear contraindications to all forms of oral anticoagulation.

The task force concluded that patients who have bleeding on oral anticoagulation can often be managed with local therapy and discontinuation of anticoagulation therapy for a day or two before resumption. However, decisions regarding resumption of a NOAC or warfarin after an intracranial bleed should be handled by an interdisciplinary panel composed of a stroke neurologist, a cardiologist, a neuroradiologist, and a neurosurgeon.

Evidence-based treatment options in patients with symptomatic AF after failed catheter ablation include minimally invasive surgery with epicardial pulmonary vein isolation, more extensive catheter ablation, and hybrid procedures, according to Dr. Benussi, who is codirector of clinical cardiovascular surgery at University Hospital in Zurich.

The guidelines state that the data supporting catheter ablation to achieve long-term rhythm control are now sufficiently strong that this intervention should be considered as a first-line option alongside antiarrhythmic drugs as a matter of patient preference in the setting of symptomatic paroxysmal AF regardless of whether the patient has CAD, heart failure, valvular heart disease, or no structural heart disease.

Catheter ablation using radiofrequency energy or cryoablation should target complete isolation of the pulmonary veins.

“Additional ablation lines do not provide demonstrable clinical benefit and increase the risk of postablation left atrial arrhythmias,” the surgeon said.

Maze surgery, preferably biatrial, received a favorable Class IIa, Level of Evidence A recommendation as worthy of consideration in patients with symptomatic AF who are already undergoing cardiac surgery. This recommendation was based upon an external review by the Cochrane group which was commissioned by the guidelines task force. The Cochrane review of eight published studies concluded that Maze surgery under such circumstances was associated with a twofold increased freedom from AF, atrial flutter, and atrial tachycardia (Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2016;8: CD012088. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012088.pub2).

The AF management guidelines are supported by the ESC Pocket Guidelines app, which includes an overall AF treatment manager developed by the European Union–funded CATCH ME (Characterizing Atrial Fibrillation by Translating its Causes Into Health Modifiers in the Elderly) project.

The multidisciplinary 17-member AF management task force was drawn from cardiology, stroke neurology, cardiac surgery, and specialist nursing. Dr. Kirchhof stressed that only recommendations supported by at least 75% of task force members made it into the guidelines (Eur Heart J. 2016 Aug 27. pii: ehw210. [Epub ahead of print] doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw210).

SAVR for radiation-induced aortic stenosis has high late mortality

ROME – Radiation-induced aortic stenosis is associated with markedly worse long-term outcome after surgical aortic valve replacement than when the operation is performed in patients without a history of radiotherapy, Milind Y. Desai, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

Moreover, the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) score isn’t good at risk-stratifying patients with radiation-induced aortic stenosis who are under consideration for surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR).

Radiation-induced heart disease is a late complication of thoracic radiotherapy. It’s particularly common in patients who got radiation for lymphomas or breast cancer. It can affect any cardiac structure, including the myocardium, pericardium, valves, coronary arteries, and the conduction system.

Aortic stenosis is the most common valvular manifestation, present in roughly 80% of patients with radiation-induced heart disease. At the Cleveland Clinic, the average time from radiotherapy to development of radiation-induced aortic stenosis (RIAS) is about 20 years. The condition is characterized by thickening of the junction between the base of the anterior mitral leaflet and aortic root, known as the aortomitral curtain, Dr. Desai explained.

He presented a retrospective observational cohort study involving 172 patients who underwent SAVR for RIAS and an equal number of SAVR patients with no such history. The groups were matched by age, sex, aortic valve area, and type and timing of SAVR. Of note, the group with RIAS had a mean preoperative STS score of 11, and the control group averaged a similar score of 10.

The key finding: During a mean follow-up of 6 years, the all-cause mortality rate was a hefty 48% in patients with RIAS, compared with just 7% in matched controls. Only about 5% of deaths in the group with RIAS were from recurrent malignancy. The low figure is not surprising given the average 20-year lag between radiotherapy and development of radiation-induced heart disease.

“In our experience, most of these patients develop a recurrent pleural effusion and nasty cardiopulmonary issues that result in their death,” according to Dr. Desai.

In a multivariate Cox proportional hazards analysis, a history of chest radiation therapy was by far the strongest predictor of all-cause mortality, conferring an 8.5-fold increase in risk.

The only other statistically significant predictor of mortality during follow-up in multivariate analysis was a high STS score, with an associated weak albeit statistically significant 1.15-fold increased risk. A total of 30 of 78 (39%) RIAS patients with an STS score below 4 died during follow-up, compared with none of 91 controls.

Thirty-four of 92 (37%) RIAS patients under age 65 died during follow-up, whereas none of 83 control SAVR patients did so.

Having coronary artery bypass surgery or other cardiac surgery at the time of SAVR was not associated with significantly increased risk of mortality compared with solo SAVR.

In-hospital outcomes were consistently worse after SAVR in the RIAS group. Half of the RIAS patients experienced in-hospital atrial fibrillation and 29% developed persistent atrial fibrillation, compared with 30% and 24% of controls. About 22% of RIAS patients were readmitted within 3 months after surgery, as were only 8% of controls. In-hospital mortality occurred in 2% of SAVR patients with RIAS; none of the matched controls did.

Dr. Desai reported having no financial interests relative to this study.

ROME – Radiation-induced aortic stenosis is associated with markedly worse long-term outcome after surgical aortic valve replacement than when the operation is performed in patients without a history of radiotherapy, Milind Y. Desai, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

Moreover, the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) score isn’t good at risk-stratifying patients with radiation-induced aortic stenosis who are under consideration for surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR).

Radiation-induced heart disease is a late complication of thoracic radiotherapy. It’s particularly common in patients who got radiation for lymphomas or breast cancer. It can affect any cardiac structure, including the myocardium, pericardium, valves, coronary arteries, and the conduction system.

Aortic stenosis is the most common valvular manifestation, present in roughly 80% of patients with radiation-induced heart disease. At the Cleveland Clinic, the average time from radiotherapy to development of radiation-induced aortic stenosis (RIAS) is about 20 years. The condition is characterized by thickening of the junction between the base of the anterior mitral leaflet and aortic root, known as the aortomitral curtain, Dr. Desai explained.

He presented a retrospective observational cohort study involving 172 patients who underwent SAVR for RIAS and an equal number of SAVR patients with no such history. The groups were matched by age, sex, aortic valve area, and type and timing of SAVR. Of note, the group with RIAS had a mean preoperative STS score of 11, and the control group averaged a similar score of 10.

The key finding: During a mean follow-up of 6 years, the all-cause mortality rate was a hefty 48% in patients with RIAS, compared with just 7% in matched controls. Only about 5% of deaths in the group with RIAS were from recurrent malignancy. The low figure is not surprising given the average 20-year lag between radiotherapy and development of radiation-induced heart disease.

“In our experience, most of these patients develop a recurrent pleural effusion and nasty cardiopulmonary issues that result in their death,” according to Dr. Desai.

In a multivariate Cox proportional hazards analysis, a history of chest radiation therapy was by far the strongest predictor of all-cause mortality, conferring an 8.5-fold increase in risk.

The only other statistically significant predictor of mortality during follow-up in multivariate analysis was a high STS score, with an associated weak albeit statistically significant 1.15-fold increased risk. A total of 30 of 78 (39%) RIAS patients with an STS score below 4 died during follow-up, compared with none of 91 controls.

Thirty-four of 92 (37%) RIAS patients under age 65 died during follow-up, whereas none of 83 control SAVR patients did so.

Having coronary artery bypass surgery or other cardiac surgery at the time of SAVR was not associated with significantly increased risk of mortality compared with solo SAVR.

In-hospital outcomes were consistently worse after SAVR in the RIAS group. Half of the RIAS patients experienced in-hospital atrial fibrillation and 29% developed persistent atrial fibrillation, compared with 30% and 24% of controls. About 22% of RIAS patients were readmitted within 3 months after surgery, as were only 8% of controls. In-hospital mortality occurred in 2% of SAVR patients with RIAS; none of the matched controls did.

Dr. Desai reported having no financial interests relative to this study.

ROME – Radiation-induced aortic stenosis is associated with markedly worse long-term outcome after surgical aortic valve replacement than when the operation is performed in patients without a history of radiotherapy, Milind Y. Desai, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

Moreover, the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) score isn’t good at risk-stratifying patients with radiation-induced aortic stenosis who are under consideration for surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR).

Radiation-induced heart disease is a late complication of thoracic radiotherapy. It’s particularly common in patients who got radiation for lymphomas or breast cancer. It can affect any cardiac structure, including the myocardium, pericardium, valves, coronary arteries, and the conduction system.

Aortic stenosis is the most common valvular manifestation, present in roughly 80% of patients with radiation-induced heart disease. At the Cleveland Clinic, the average time from radiotherapy to development of radiation-induced aortic stenosis (RIAS) is about 20 years. The condition is characterized by thickening of the junction between the base of the anterior mitral leaflet and aortic root, known as the aortomitral curtain, Dr. Desai explained.

He presented a retrospective observational cohort study involving 172 patients who underwent SAVR for RIAS and an equal number of SAVR patients with no such history. The groups were matched by age, sex, aortic valve area, and type and timing of SAVR. Of note, the group with RIAS had a mean preoperative STS score of 11, and the control group averaged a similar score of 10.

The key finding: During a mean follow-up of 6 years, the all-cause mortality rate was a hefty 48% in patients with RIAS, compared with just 7% in matched controls. Only about 5% of deaths in the group with RIAS were from recurrent malignancy. The low figure is not surprising given the average 20-year lag between radiotherapy and development of radiation-induced heart disease.

“In our experience, most of these patients develop a recurrent pleural effusion and nasty cardiopulmonary issues that result in their death,” according to Dr. Desai.

In a multivariate Cox proportional hazards analysis, a history of chest radiation therapy was by far the strongest predictor of all-cause mortality, conferring an 8.5-fold increase in risk.

The only other statistically significant predictor of mortality during follow-up in multivariate analysis was a high STS score, with an associated weak albeit statistically significant 1.15-fold increased risk. A total of 30 of 78 (39%) RIAS patients with an STS score below 4 died during follow-up, compared with none of 91 controls.

Thirty-four of 92 (37%) RIAS patients under age 65 died during follow-up, whereas none of 83 control SAVR patients did so.

Having coronary artery bypass surgery or other cardiac surgery at the time of SAVR was not associated with significantly increased risk of mortality compared with solo SAVR.

In-hospital outcomes were consistently worse after SAVR in the RIAS group. Half of the RIAS patients experienced in-hospital atrial fibrillation and 29% developed persistent atrial fibrillation, compared with 30% and 24% of controls. About 22% of RIAS patients were readmitted within 3 months after surgery, as were only 8% of controls. In-hospital mortality occurred in 2% of SAVR patients with RIAS; none of the matched controls did.

Dr. Desai reported having no financial interests relative to this study.

AT THE ESC CONGRESS 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: All-cause mortality occurred in 48% of 172 patients with radiation-induced severe aortic stenosis during a mean follow-up of 6 years after surgical aortic valve replacement, compared with just 7% of matched controls.

Data source: This was a retrospective observational study involving 172 closely matched pairs of surgical aortic valve replacement patients.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding this study.

Beta-blockers curb death risk in patients with primary prevention ICD

ROME – Beta-blocker therapy reduces the risks of all-cause mortality as well as cardiac death in patients with a left ventricular ejection fraction below 35% who get an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator for primary prevention, Laurent Fauchier, MD, PhD, reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

Some physicians have recently urged reconsideration of current guidelines recommending routine use of beta-blockers for prevention of cardiovascular events in certain groups of patients with coronary artery disease, including those with chronic heart failure who have received an ICD for primary prevention of sudden death. And indeed it’s true that the now–relatively old randomized trials of ICDs for primary prevention in patients with chronic heart failure don’t provide any real evidence that beta-blockers reduce mortality in this setting. In fact, the guideline recommendation for beta-blockade has been based upon expert opinion. This was the impetus for Dr. Fauchier and coinvestigators to conduct a large retrospective observational study in a contemporary cohort of heart failure patients who received an ICD for primary prevention during a recent 10-year period at the 12 largest centers in France.

Fifteen percent of the 3,975 French ICD recipients did not receive a beta-blocker. They differed from those who did in that they were on average 2 years older, had an absolute 5% lower ejection fraction, and were more likely to also receive cardiac resynchronization therapy. Propensity score matching based on these and 19 other baseline characteristics enabled investigators to assemble a cohort of 541 closely matched patient pairs, explained Dr. Fauchier, professor of cardiology at Francois Rabelais University in Tours, France.

During a mean follow-up of 3.2 years, the risk of all-cause mortality in ICD recipients not on a beta-blocker was 34% higher than in those who were. Moreover, their risk of cardiac death was 50% greater.

In contrast, beta-blocker therapy had no effect on the risks of sudden death or of appropriate or inappropriate shocks.

The finding that beta-blocker therapy doesn’t prevent sudden death in patients with an ICD for primary prevention has not previously been reported. However, it makes sense. The device prevents such events so effectively that a beta-blocker adds nothing further in that regard, according to Dr. Fauchier.

“Beta-blockers should continue to be used widely, as currently recommended, for heart failure in the specific setting of patients with prophylactic ICD implantation. You do not have the benefit for prevention of sudden death, but you still have all the benefit from preventing cardiac death,” the electrophysiologist concluded.

This study was supported by French governmental research grants. Dr. Fauchier reported serving as a consultant to Bayer, Pfizer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Medtronic, and Novartis.

ROME – Beta-blocker therapy reduces the risks of all-cause mortality as well as cardiac death in patients with a left ventricular ejection fraction below 35% who get an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator for primary prevention, Laurent Fauchier, MD, PhD, reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

Some physicians have recently urged reconsideration of current guidelines recommending routine use of beta-blockers for prevention of cardiovascular events in certain groups of patients with coronary artery disease, including those with chronic heart failure who have received an ICD for primary prevention of sudden death. And indeed it’s true that the now–relatively old randomized trials of ICDs for primary prevention in patients with chronic heart failure don’t provide any real evidence that beta-blockers reduce mortality in this setting. In fact, the guideline recommendation for beta-blockade has been based upon expert opinion. This was the impetus for Dr. Fauchier and coinvestigators to conduct a large retrospective observational study in a contemporary cohort of heart failure patients who received an ICD for primary prevention during a recent 10-year period at the 12 largest centers in France.

Fifteen percent of the 3,975 French ICD recipients did not receive a beta-blocker. They differed from those who did in that they were on average 2 years older, had an absolute 5% lower ejection fraction, and were more likely to also receive cardiac resynchronization therapy. Propensity score matching based on these and 19 other baseline characteristics enabled investigators to assemble a cohort of 541 closely matched patient pairs, explained Dr. Fauchier, professor of cardiology at Francois Rabelais University in Tours, France.

During a mean follow-up of 3.2 years, the risk of all-cause mortality in ICD recipients not on a beta-blocker was 34% higher than in those who were. Moreover, their risk of cardiac death was 50% greater.

In contrast, beta-blocker therapy had no effect on the risks of sudden death or of appropriate or inappropriate shocks.

The finding that beta-blocker therapy doesn’t prevent sudden death in patients with an ICD for primary prevention has not previously been reported. However, it makes sense. The device prevents such events so effectively that a beta-blocker adds nothing further in that regard, according to Dr. Fauchier.

“Beta-blockers should continue to be used widely, as currently recommended, for heart failure in the specific setting of patients with prophylactic ICD implantation. You do not have the benefit for prevention of sudden death, but you still have all the benefit from preventing cardiac death,” the electrophysiologist concluded.

This study was supported by French governmental research grants. Dr. Fauchier reported serving as a consultant to Bayer, Pfizer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Medtronic, and Novartis.

ROME – Beta-blocker therapy reduces the risks of all-cause mortality as well as cardiac death in patients with a left ventricular ejection fraction below 35% who get an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator for primary prevention, Laurent Fauchier, MD, PhD, reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

Some physicians have recently urged reconsideration of current guidelines recommending routine use of beta-blockers for prevention of cardiovascular events in certain groups of patients with coronary artery disease, including those with chronic heart failure who have received an ICD for primary prevention of sudden death. And indeed it’s true that the now–relatively old randomized trials of ICDs for primary prevention in patients with chronic heart failure don’t provide any real evidence that beta-blockers reduce mortality in this setting. In fact, the guideline recommendation for beta-blockade has been based upon expert opinion. This was the impetus for Dr. Fauchier and coinvestigators to conduct a large retrospective observational study in a contemporary cohort of heart failure patients who received an ICD for primary prevention during a recent 10-year period at the 12 largest centers in France.

Fifteen percent of the 3,975 French ICD recipients did not receive a beta-blocker. They differed from those who did in that they were on average 2 years older, had an absolute 5% lower ejection fraction, and were more likely to also receive cardiac resynchronization therapy. Propensity score matching based on these and 19 other baseline characteristics enabled investigators to assemble a cohort of 541 closely matched patient pairs, explained Dr. Fauchier, professor of cardiology at Francois Rabelais University in Tours, France.

During a mean follow-up of 3.2 years, the risk of all-cause mortality in ICD recipients not on a beta-blocker was 34% higher than in those who were. Moreover, their risk of cardiac death was 50% greater.

In contrast, beta-blocker therapy had no effect on the risks of sudden death or of appropriate or inappropriate shocks.

The finding that beta-blocker therapy doesn’t prevent sudden death in patients with an ICD for primary prevention has not previously been reported. However, it makes sense. The device prevents such events so effectively that a beta-blocker adds nothing further in that regard, according to Dr. Fauchier.

“Beta-blockers should continue to be used widely, as currently recommended, for heart failure in the specific setting of patients with prophylactic ICD implantation. You do not have the benefit for prevention of sudden death, but you still have all the benefit from preventing cardiac death,” the electrophysiologist concluded.

This study was supported by French governmental research grants. Dr. Fauchier reported serving as a consultant to Bayer, Pfizer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Medtronic, and Novartis.

AT THE ESC CONGRESS 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction who received an ICD for primary prevention and were not on a beta-blocker were at an adjusted 50% increased risk for cardiac death and 34% increased risk for all-cause mortality during 3.2 years of follow-up, but they were at no increased risk for sudden death.

Data source: A retrospective observational study of all of the nearly 4,000 patients who received a primary prevention ICD at the 12 largest French centers during a recent 10-year period.

Disclosures: This study was supported by French governmental research funds. The presenter reported serving as a consultant to Bayer, Pfizer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Medtronic, and Novartis.

Algorithm for suspected pulmonary embolism safely cut CT rate

ROME – A newly validated, simplified algorithm for the management of patients with suspected acute pulmonary embolism enables physicians to safely exclude the disorder in roughly half of patients without resorting to CT pulmonary angiography, Tom van der Hulle, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

“This is the largest study ever performed in the diagnostic management of suspected pulmonary embolism. Based on our results, I think the YEARS algorithm is ready to be used in daily clinical practice,” declared Dr. van der Hulle of the department of thrombosis and hemostasis at Leiden (the Netherlands) University Medical Center.

Using the YEARS algorithm, PE was reliably ruled out without need for CT pulmonary angiography – considered the standard in the diagnosis of PE – in 48% of patients. In contrast, adherence to the Wells rule would have meant that 62% of patients would have gotten a CT scan to rule out PE with a comparably high degree of accuracy.

But that 62% figure underestimates the actual CT rate in clinical practice. The reality is that although the guideline-recommended Wells rule and revised Geneva score have been shown to be safe and accurate, they are so complex, cumbersome, and out of sync with the flow of routine clinical practice that many physicians skip the algorithms and go straight to CT, Dr. van der Hulle said. This approach results in many unnecessary CTs, needlessly exposing patients to the risks of radiation and intravenous contrast material while driving up health care costs, he added.

Using the Wells rule or revised Geneva score, the patient evaluation begins with an assessment of the clinical probability of PE based upon a risk score involving seven or eight factors. Only patients with a low or intermediate clinical probability of PE get a D-dimer test; those with a high clinical probability go straight to CT.

The YEARS algorithm is much simpler than that, Dr. van der Hulle explained. Everyone who presents with suspected acute PE gets a D-dimer test while the physician simultaneously applies a brief, three-item clinical prediction rule. These three items were selected by the Dutch investigators because they were the three strongest predictors of PE out of the original seven in the Wells rule. They are hemoptysis, clinical signs of deep vein thrombosis such as leg swelling or hyperpigmentation, and the clinician’s global impression of PE as being the most likely diagnosis.

In the YEARS algorithm, the threshold for a positive D-dimer test warranting CT pulmonary angiography depends upon whether any of the three clinical predictors is present. If none is present, the threshold is 1,000 ng/mL or above; if one or more is present, the threshold for a positive D-dimer test drops to 500 ng/mL.

Using these criteria, PE was excluded without resort to CT in 1,306 patients with none of the three YEARS items and a D-dimer test result below 1,000 ng/mL, as well as in another 327 patients with one or more YEARS items present but a D-dimer below 500 ng/mL. Those two groups were left untreated and followed prospectively for 3 months.

The 964 patients with one or more YEARS predictors present and a D-dimer score of at least 500 ng/mL underwent CT imaging, as did the 352 with no YEARS items and a D-dimer of at least 1,000 ng/mL.

The prevalence of CT-confirmed PE in the study was 13.2%. Affected patients were treated with anticoagulants.

The primary study endpoint was the total rate of deep vein thrombosis during 3 months of follow-up after PE had been excluded. The rate was 0.61%, including a fatal PE rate of 0.20%. The rate in patients managed without CT was 0.43%, including a 0.12% rate of fatal PE. In patients managed with diagnostic CT, the deep vein thrombosis rate was 0.84%, with a fatal PE rate of 0.30%.

“I think these results are completely comparable to those in previous studies using the standard algorithms,” Dr. van der Hulle commented.

The study’s main limitation is that it wasn’t a randomized, controlled trial. But given the tiny event rates, detecting any small differences between management strategies would require an unrealistically huge sample size, he added.

Asked if he thinks physicians will actually use the new tool, Dr. van der Hulle replied that some physicians feel driven to be 100% sure that a patient doesn’t have PE, and they will probably keep overordering CT scans. But others will embrace the YEARS algorithm because it reduces wasted resources and minimizes radiation exposure, a particularly compelling consideration in young female patients.

Discussant Marion Delcroix, MD, had reservations. She said she appreciated the appeal of a simple algorithm, but she asked, “Couldn’t we do better with a bit more sophistication, perhaps by adjusting the D-dimer cutoff for age and also adding some other items, like oxygen saturation and estrogen use?

“My concern is about the applicability. The age of the study cohort is relatively young, at a mean of 53 years. The peak age of PE in a very large contemporary German database is 70-80 years. We don’t know if the YEARS score is any good in this older population,” asserted Dr. Delcroix, professor of medicine and respiratory physiology and head of the center for pulmonary vascular diseases at University Hospital in Leuven, Belgium.

“If the aim is to decrease the number of CT pulmonary angiograms for safety reasons, why not reintroduce compression ultrasound of the lower limbs in the diagnostic algorithm?” she continued. “It has been shown to effectively reduce the need for further imaging.”

Dr. Delcroix predicted that the YEARS algorithm study will prove “too optimistic” regarding the number of CT scans avoided, particularly in elderly patients.

The YEARS study was funded by the trial’s 12 participating Dutch hospitals. Dr. van der Hulle reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

ROME – A newly validated, simplified algorithm for the management of patients with suspected acute pulmonary embolism enables physicians to safely exclude the disorder in roughly half of patients without resorting to CT pulmonary angiography, Tom van der Hulle, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

“This is the largest study ever performed in the diagnostic management of suspected pulmonary embolism. Based on our results, I think the YEARS algorithm is ready to be used in daily clinical practice,” declared Dr. van der Hulle of the department of thrombosis and hemostasis at Leiden (the Netherlands) University Medical Center.

Using the YEARS algorithm, PE was reliably ruled out without need for CT pulmonary angiography – considered the standard in the diagnosis of PE – in 48% of patients. In contrast, adherence to the Wells rule would have meant that 62% of patients would have gotten a CT scan to rule out PE with a comparably high degree of accuracy.

But that 62% figure underestimates the actual CT rate in clinical practice. The reality is that although the guideline-recommended Wells rule and revised Geneva score have been shown to be safe and accurate, they are so complex, cumbersome, and out of sync with the flow of routine clinical practice that many physicians skip the algorithms and go straight to CT, Dr. van der Hulle said. This approach results in many unnecessary CTs, needlessly exposing patients to the risks of radiation and intravenous contrast material while driving up health care costs, he added.

Using the Wells rule or revised Geneva score, the patient evaluation begins with an assessment of the clinical probability of PE based upon a risk score involving seven or eight factors. Only patients with a low or intermediate clinical probability of PE get a D-dimer test; those with a high clinical probability go straight to CT.

The YEARS algorithm is much simpler than that, Dr. van der Hulle explained. Everyone who presents with suspected acute PE gets a D-dimer test while the physician simultaneously applies a brief, three-item clinical prediction rule. These three items were selected by the Dutch investigators because they were the three strongest predictors of PE out of the original seven in the Wells rule. They are hemoptysis, clinical signs of deep vein thrombosis such as leg swelling or hyperpigmentation, and the clinician’s global impression of PE as being the most likely diagnosis.

In the YEARS algorithm, the threshold for a positive D-dimer test warranting CT pulmonary angiography depends upon whether any of the three clinical predictors is present. If none is present, the threshold is 1,000 ng/mL or above; if one or more is present, the threshold for a positive D-dimer test drops to 500 ng/mL.

Using these criteria, PE was excluded without resort to CT in 1,306 patients with none of the three YEARS items and a D-dimer test result below 1,000 ng/mL, as well as in another 327 patients with one or more YEARS items present but a D-dimer below 500 ng/mL. Those two groups were left untreated and followed prospectively for 3 months.

The 964 patients with one or more YEARS predictors present and a D-dimer score of at least 500 ng/mL underwent CT imaging, as did the 352 with no YEARS items and a D-dimer of at least 1,000 ng/mL.

The prevalence of CT-confirmed PE in the study was 13.2%. Affected patients were treated with anticoagulants.

The primary study endpoint was the total rate of deep vein thrombosis during 3 months of follow-up after PE had been excluded. The rate was 0.61%, including a fatal PE rate of 0.20%. The rate in patients managed without CT was 0.43%, including a 0.12% rate of fatal PE. In patients managed with diagnostic CT, the deep vein thrombosis rate was 0.84%, with a fatal PE rate of 0.30%.

“I think these results are completely comparable to those in previous studies using the standard algorithms,” Dr. van der Hulle commented.

The study’s main limitation is that it wasn’t a randomized, controlled trial. But given the tiny event rates, detecting any small differences between management strategies would require an unrealistically huge sample size, he added.

Asked if he thinks physicians will actually use the new tool, Dr. van der Hulle replied that some physicians feel driven to be 100% sure that a patient doesn’t have PE, and they will probably keep overordering CT scans. But others will embrace the YEARS algorithm because it reduces wasted resources and minimizes radiation exposure, a particularly compelling consideration in young female patients.

Discussant Marion Delcroix, MD, had reservations. She said she appreciated the appeal of a simple algorithm, but she asked, “Couldn’t we do better with a bit more sophistication, perhaps by adjusting the D-dimer cutoff for age and also adding some other items, like oxygen saturation and estrogen use?

“My concern is about the applicability. The age of the study cohort is relatively young, at a mean of 53 years. The peak age of PE in a very large contemporary German database is 70-80 years. We don’t know if the YEARS score is any good in this older population,” asserted Dr. Delcroix, professor of medicine and respiratory physiology and head of the center for pulmonary vascular diseases at University Hospital in Leuven, Belgium.

“If the aim is to decrease the number of CT pulmonary angiograms for safety reasons, why not reintroduce compression ultrasound of the lower limbs in the diagnostic algorithm?” she continued. “It has been shown to effectively reduce the need for further imaging.”

Dr. Delcroix predicted that the YEARS algorithm study will prove “too optimistic” regarding the number of CT scans avoided, particularly in elderly patients.

The YEARS study was funded by the trial’s 12 participating Dutch hospitals. Dr. van der Hulle reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

ROME – A newly validated, simplified algorithm for the management of patients with suspected acute pulmonary embolism enables physicians to safely exclude the disorder in roughly half of patients without resorting to CT pulmonary angiography, Tom van der Hulle, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

“This is the largest study ever performed in the diagnostic management of suspected pulmonary embolism. Based on our results, I think the YEARS algorithm is ready to be used in daily clinical practice,” declared Dr. van der Hulle of the department of thrombosis and hemostasis at Leiden (the Netherlands) University Medical Center.

Using the YEARS algorithm, PE was reliably ruled out without need for CT pulmonary angiography – considered the standard in the diagnosis of PE – in 48% of patients. In contrast, adherence to the Wells rule would have meant that 62% of patients would have gotten a CT scan to rule out PE with a comparably high degree of accuracy.

But that 62% figure underestimates the actual CT rate in clinical practice. The reality is that although the guideline-recommended Wells rule and revised Geneva score have been shown to be safe and accurate, they are so complex, cumbersome, and out of sync with the flow of routine clinical practice that many physicians skip the algorithms and go straight to CT, Dr. van der Hulle said. This approach results in many unnecessary CTs, needlessly exposing patients to the risks of radiation and intravenous contrast material while driving up health care costs, he added.

Using the Wells rule or revised Geneva score, the patient evaluation begins with an assessment of the clinical probability of PE based upon a risk score involving seven or eight factors. Only patients with a low or intermediate clinical probability of PE get a D-dimer test; those with a high clinical probability go straight to CT.

The YEARS algorithm is much simpler than that, Dr. van der Hulle explained. Everyone who presents with suspected acute PE gets a D-dimer test while the physician simultaneously applies a brief, three-item clinical prediction rule. These three items were selected by the Dutch investigators because they were the three strongest predictors of PE out of the original seven in the Wells rule. They are hemoptysis, clinical signs of deep vein thrombosis such as leg swelling or hyperpigmentation, and the clinician’s global impression of PE as being the most likely diagnosis.

In the YEARS algorithm, the threshold for a positive D-dimer test warranting CT pulmonary angiography depends upon whether any of the three clinical predictors is present. If none is present, the threshold is 1,000 ng/mL or above; if one or more is present, the threshold for a positive D-dimer test drops to 500 ng/mL.

Using these criteria, PE was excluded without resort to CT in 1,306 patients with none of the three YEARS items and a D-dimer test result below 1,000 ng/mL, as well as in another 327 patients with one or more YEARS items present but a D-dimer below 500 ng/mL. Those two groups were left untreated and followed prospectively for 3 months.

The 964 patients with one or more YEARS predictors present and a D-dimer score of at least 500 ng/mL underwent CT imaging, as did the 352 with no YEARS items and a D-dimer of at least 1,000 ng/mL.

The prevalence of CT-confirmed PE in the study was 13.2%. Affected patients were treated with anticoagulants.

The primary study endpoint was the total rate of deep vein thrombosis during 3 months of follow-up after PE had been excluded. The rate was 0.61%, including a fatal PE rate of 0.20%. The rate in patients managed without CT was 0.43%, including a 0.12% rate of fatal PE. In patients managed with diagnostic CT, the deep vein thrombosis rate was 0.84%, with a fatal PE rate of 0.30%.

“I think these results are completely comparable to those in previous studies using the standard algorithms,” Dr. van der Hulle commented.

The study’s main limitation is that it wasn’t a randomized, controlled trial. But given the tiny event rates, detecting any small differences between management strategies would require an unrealistically huge sample size, he added.

Asked if he thinks physicians will actually use the new tool, Dr. van der Hulle replied that some physicians feel driven to be 100% sure that a patient doesn’t have PE, and they will probably keep overordering CT scans. But others will embrace the YEARS algorithm because it reduces wasted resources and minimizes radiation exposure, a particularly compelling consideration in young female patients.

Discussant Marion Delcroix, MD, had reservations. She said she appreciated the appeal of a simple algorithm, but she asked, “Couldn’t we do better with a bit more sophistication, perhaps by adjusting the D-dimer cutoff for age and also adding some other items, like oxygen saturation and estrogen use?

“My concern is about the applicability. The age of the study cohort is relatively young, at a mean of 53 years. The peak age of PE in a very large contemporary German database is 70-80 years. We don’t know if the YEARS score is any good in this older population,” asserted Dr. Delcroix, professor of medicine and respiratory physiology and head of the center for pulmonary vascular diseases at University Hospital in Leuven, Belgium.

“If the aim is to decrease the number of CT pulmonary angiograms for safety reasons, why not reintroduce compression ultrasound of the lower limbs in the diagnostic algorithm?” she continued. “It has been shown to effectively reduce the need for further imaging.”

Dr. Delcroix predicted that the YEARS algorithm study will prove “too optimistic” regarding the number of CT scans avoided, particularly in elderly patients.

The YEARS study was funded by the trial’s 12 participating Dutch hospitals. Dr. van der Hulle reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Applying the YEARS algorithm to a large population of patients with suspected PE, the 3-month incidence of deep vein thrombosis after PE had been excluded was 0.61%.

Data source: This was a prospective study of clinical outcomes in nearly 3,000 consecutive Dutch patients who presented with suspected acute PE and were managed in accord with the YEARS algorithm.

Disclosures: The YEARS algorithm validation study was funded by the trial’s 12 participating Dutch hospitals. The study presenter reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

CABG best for diabetes patients with CKD – or is it?

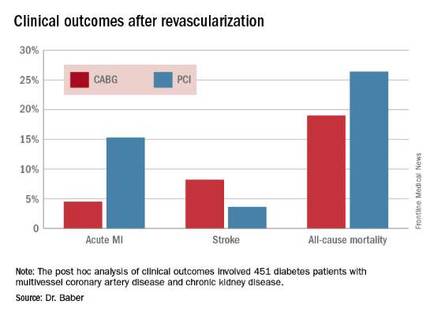

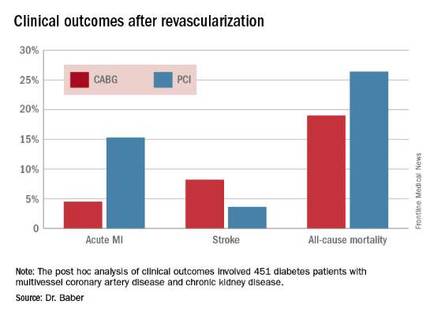

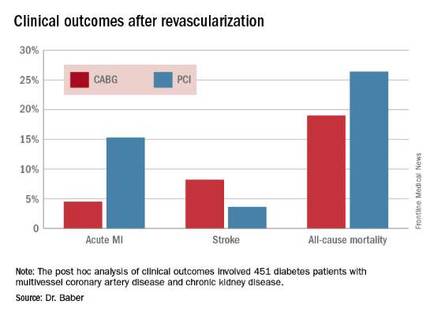

ROME – The use of coronary artery bypass graft surgery for revascularization in patients with multivessel CAD and comorbid diabetes plus chronic kidney disease was associated with a significantly lower risk of major cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events than was PCI with first-generation drug-eluting stents in a new secondary analysis from the landmark FREEDOM trial.

“The reason for this presentation is that even though chronic kidney disease is common in patients with diabetes, until now there has not been a large study of the efficacy and safety of coronary revascularization with drug-eluting stents versus CABG in this population in a randomized trial cohort,” explained Usman Baber, MD, who reported the results at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

FREEDOM (Future Revascularization Evaluation in Patients with Diabetes Mellitus: Optimal Management of Multivessel Disease) randomized 1,900 diabetic patients with multivessel CAD to PCI or CABG. As previously reported, CABG proved superior to PCI, with a significantly lower rate of the composite primary endpoint composed of all-cause mortality, MI, or stroke (N Engl J Med. 2012 Dec 20;367[25]:2375-84).

Dr. Baber presented a post hoc analysis of the 451 FREEDOM participants with baseline comorbid chronic kidney disease (CKD). Their mean SYNTAX score was 27, and their mean baseline estimated glomerular filtration rate was 44 mL/min per 1.73 m2, indicative of mild to moderate CKD.

“Only 28 patients in the FREEDOM trial had an estimated GFR below 30, therefore we can’t make any inferences about revascularization in that setting, which I think is a completely different population,” he noted.

The 5-year rate of major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events in patients with CKD was 26% in the CABG group, an absolute 9.4% less than the 35.6% rate in subjects randomized to PCI.

Roughly one-quarter of FREEDOM participants had CKD. They fared significantly worse than did those without CKD. The 5-year incidence of major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events was 30.8% in patients with CKD and 20.1% in patients without renal impairment. In a multivariate analysis adjusted for age, gender, hypertension, peripheral vascular disease, and other potential confounders, the risk of all-cause mortality was twofold higher in the CKD group. Their risk of cardiac death was increased 1.8-fold, and they were at 1.9-fold increased risk for stroke. Interestingly, however, the acute MI risk did not differ between patients with or without CKD, Dr. Baber observed.

Drilling deeper into the data, the cardiologist reported that CABG was associated with significantly lower rates of MI and a nonsignificant trend for fewer deaths, but with a significantly higher stroke rate than PCI.

One audience member rose to complain that this information won’t be helpful in counseling his diabetic patients with CKD and multivessel CAD because the choices look so grim: a higher risk of MI with percutaneous therapy, and a greater risk of stroke with surgery.

Dr. Baber replied by pointing out that the 10.8% absolute reduction in the risk of MI with CABG compared with PCI was more than twice as large as the absolute 4.6% increase in stroke risk with surgery.

“Most people would say that a heart attack is an inconvenience, and a stroke is a life-changing experience for them and their family,” said session cochair Kim A. Williams, MD, professor of medicine and chairman of cardiology at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago.

At that, Dr. Baber backtracked a bit, observing that since this was a post hoc analysis, the FREEDOM findings in patients with CKD must be viewed as hypothesis-generating rather than definitive. And, of course, contemporary second-generation drug-eluting stents have a better risk/benefit profile than do those used in FREEDOM.

“The number needed to treat/number needed to harm ratio for CABG and PCI probably ends up being roughly equal. The pertinence of an analysis like this is if you look at real-world registry-based data, you find a therapeutic nihilism that’s highly prevalent in CKD patients, where many patients who might benefit are not provided with revascularization therapy. It’s clear that we as clinicians – either because we don’t know there is a benefit or we are too concerned about potential harm – deprive patients of a treatment that might be beneficial. This analysis makes clinicians who might be concerned feel somewhat comforted that there is not unacceptable harm and that there is benefit,” Dr. Baber said.

Follow-up of FREEDOM participants continues and will be the subject of future reports, he added.

The FREEDOM trial was sponsored by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. Dr. Baber reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

ROME – The use of coronary artery bypass graft surgery for revascularization in patients with multivessel CAD and comorbid diabetes plus chronic kidney disease was associated with a significantly lower risk of major cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events than was PCI with first-generation drug-eluting stents in a new secondary analysis from the landmark FREEDOM trial.

“The reason for this presentation is that even though chronic kidney disease is common in patients with diabetes, until now there has not been a large study of the efficacy and safety of coronary revascularization with drug-eluting stents versus CABG in this population in a randomized trial cohort,” explained Usman Baber, MD, who reported the results at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

FREEDOM (Future Revascularization Evaluation in Patients with Diabetes Mellitus: Optimal Management of Multivessel Disease) randomized 1,900 diabetic patients with multivessel CAD to PCI or CABG. As previously reported, CABG proved superior to PCI, with a significantly lower rate of the composite primary endpoint composed of all-cause mortality, MI, or stroke (N Engl J Med. 2012 Dec 20;367[25]:2375-84).

Dr. Baber presented a post hoc analysis of the 451 FREEDOM participants with baseline comorbid chronic kidney disease (CKD). Their mean SYNTAX score was 27, and their mean baseline estimated glomerular filtration rate was 44 mL/min per 1.73 m2, indicative of mild to moderate CKD.

“Only 28 patients in the FREEDOM trial had an estimated GFR below 30, therefore we can’t make any inferences about revascularization in that setting, which I think is a completely different population,” he noted.

The 5-year rate of major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events in patients with CKD was 26% in the CABG group, an absolute 9.4% less than the 35.6% rate in subjects randomized to PCI.