User login

Motor function restored in three men after complete paralysis from spinal cord injury

(SCI), new research shows.

The study demonstrated that an epidural electrical stimulation (EES) system developed specifically for spinal cord injuries enabled three men with complete paralysis to stand, walk, cycle, swim, and move their torso within 1 day.

“Thanks to this technology, we have been able to target individuals with the most serious spinal cord injury, meaning those with clinically complete spinal cord injury, with no sensation and no movement in the legs,” Grégoire Courtine, PhD, professor of neuroscience and neurotechnology at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, University Hospital Lausanne (Switzerland), and the University of Lausanne, told reporters attending a press briefing.

The study was published online Feb. 7, 2022, in Nature Medicine.

More rapid, precise, effective

SCIs involve severed connections between the brain and extremities. To compensate for these lost connections, researchers have investigated stem cell therapy, brain-machine interfaces, and powered exoskeletons.

However, these approaches aren’t yet ready for prime time.

In the meantime, researchers discovered even patients with a “complete” injury may have low-functioning connections and started investigating epidural stimulators designed to treat chronic pain. Recent studies – including three published in 2018 – showed promise for these pain-related stimulators in patients with incomplete SCI.

But using such “repurposed” technology meant the electrode array was relatively narrow and short, “so we could not target all the regions of the spinal cord involving control of leg and trunk movements,” said Dr. Courtine. With the newer technology “we are much more precise, effective, and more rapid in delivering therapy.”

To develop this new approach, the researchers designed a paddle lead with an arrangement of electrodes that targets sacral, lumbar, and low-thoracic dorsal roots involved in leg and trunk movements. They also established a personalized computational framework that allows for optimal surgical placement of this paddle lead.

In addition, they developed software that renders the configuration of individualized activity–dependent stimulation programs rapid, simple, and predictable.

They tested these neurotechnologies in three men with complete sensorimotor paralysis as part of an ongoing clinical trial. The participants, aged 29, 32, and 41 years, suffered an SCI from a motor bike accident 3, 9, and 1 year before enrollment.

All three patients exhibited complete sensorimotor paralysis. They were unable to take any step, and muscles remained quiescent during these attempts.

A neurosurgeon implanted electrodes along the spinal cord of study subjects. Wires from these electrodes were connected to a neurostimulator implanted under the skin in the abdomen.

The men can select different activity-based programs from a tablet that sends signals to the implanted device.

Personalized approach

Within a single day of the surgery, the participants were able to stand, walk, cycle, swim, and control trunk movements.

“It was not perfect at the very beginning, but they could train very early on to have a more fluid gait,” said study investigator neurosurgeon Joceylyne Bloch, MD, associate professor, University of Lausanne and University Hospital Lausanne.

At this stage, not all paralyzed patients are eligible for the procedure. Dr. Bloch explained that at least 6 cm of healthy spinal cord under the lesion is needed to implant the electrodes.

“There’s a huge variability of spinal cord anatomy between individuals. That’s why it’s important to study each person individually and to have individual models in order to be precise.”

Researchers envision having “a library of electrode arrays,” added Dr. Courtine. With preoperative imaging of the individual’s spinal cord, “the neurosurgeon can select the more appropriate electrode array for that specific patient.”

Dr. Courtine noted recovery of sensation with the system differs from one individual to another. One study participant, Michel Roccati, now 30, told the briefing he feels a contraction in his muscle during the stimulation.

Currently, only individuals whose injury is more than a year old are included in the study to ensure patients have “a stable lesion” and reached “a plateau of recovery,” said Dr. Bloch. However, animal models show intervening earlier might boost the benefits.

A patient’s age can influence the outcome, as younger patients are likely in better condition and more motivated than older patients, said Dr. Bloch. However, she noted patients closing in on 50 years have responded well to the therapy.

Such stimulation systems may prove useful in treating conditions typically associated with SCI, such as hypertension and bladder control, and perhaps also in patients with Parkinson’s disease, said Dr. Courtine.

The researchers plan to conduct another study that will include a next-generation pulse generator with features that make the stimulation even more effective and user friendly. A voice recognition system could eventually be connected to the system.

“The next step is a minicomputer that you implant in the body that communicates in real time with an external iPhone,” said Dr. Courtine.

ONWARD Medical, which developed the technology, has received a breakthrough device designation from the Food and Drug Administration. The company is in discussions with the FDA to carry out a clinical trial of the device in the United States.

A ‘huge step forward’

Peter J. Grahn, PhD, assistant professor, department of physical medicine and rehabilitation and department of neurologic surgery, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., an author of one of the 2018 studies, said this technology “is a huge step forward” and “really pushes the field.”

Compared with the device used in his study that’s designed to treat neuropathic pain, this new system “is much more capable of dynamic stimulation,” said Dr. Grahn. “You can tailor the stimulation based on which area of the spinal cord you want to target during a specific function.”

There has been “a lot of hope and hype” recently around stem cells and biological molecules that were supposed to be “magic pills” to cure spinal cord dysfunction, said Dr. Grahn. “I don’t think this is one of those.”

However, he questioned the researchers’ use of the word “walking.”

“They say independent stepping or walking is restored on day 1, but the graphs show day 1 function is having over 60% of their body weight supported when they’re taking these steps,” he said.

In addition, the “big question” is how this technology can “be distilled down” into an approach “applicable across rehabilitation centers,” said Dr. Grahn.

The study was supported by numerous organizations, including ONWARD Medical. Dr. Courtine and Dr. Bloch hold various patents in relation with the present work. Dr. Courtine is a consultant with ONWARD Medical, and he and Dr. Bloch are shareholders of ONWARD Medical, a company with direct relationships with the presented work. Dr. Grahn reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

(SCI), new research shows.

The study demonstrated that an epidural electrical stimulation (EES) system developed specifically for spinal cord injuries enabled three men with complete paralysis to stand, walk, cycle, swim, and move their torso within 1 day.

“Thanks to this technology, we have been able to target individuals with the most serious spinal cord injury, meaning those with clinically complete spinal cord injury, with no sensation and no movement in the legs,” Grégoire Courtine, PhD, professor of neuroscience and neurotechnology at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, University Hospital Lausanne (Switzerland), and the University of Lausanne, told reporters attending a press briefing.

The study was published online Feb. 7, 2022, in Nature Medicine.

More rapid, precise, effective

SCIs involve severed connections between the brain and extremities. To compensate for these lost connections, researchers have investigated stem cell therapy, brain-machine interfaces, and powered exoskeletons.

However, these approaches aren’t yet ready for prime time.

In the meantime, researchers discovered even patients with a “complete” injury may have low-functioning connections and started investigating epidural stimulators designed to treat chronic pain. Recent studies – including three published in 2018 – showed promise for these pain-related stimulators in patients with incomplete SCI.

But using such “repurposed” technology meant the electrode array was relatively narrow and short, “so we could not target all the regions of the spinal cord involving control of leg and trunk movements,” said Dr. Courtine. With the newer technology “we are much more precise, effective, and more rapid in delivering therapy.”

To develop this new approach, the researchers designed a paddle lead with an arrangement of electrodes that targets sacral, lumbar, and low-thoracic dorsal roots involved in leg and trunk movements. They also established a personalized computational framework that allows for optimal surgical placement of this paddle lead.

In addition, they developed software that renders the configuration of individualized activity–dependent stimulation programs rapid, simple, and predictable.

They tested these neurotechnologies in three men with complete sensorimotor paralysis as part of an ongoing clinical trial. The participants, aged 29, 32, and 41 years, suffered an SCI from a motor bike accident 3, 9, and 1 year before enrollment.

All three patients exhibited complete sensorimotor paralysis. They were unable to take any step, and muscles remained quiescent during these attempts.

A neurosurgeon implanted electrodes along the spinal cord of study subjects. Wires from these electrodes were connected to a neurostimulator implanted under the skin in the abdomen.

The men can select different activity-based programs from a tablet that sends signals to the implanted device.

Personalized approach

Within a single day of the surgery, the participants were able to stand, walk, cycle, swim, and control trunk movements.

“It was not perfect at the very beginning, but they could train very early on to have a more fluid gait,” said study investigator neurosurgeon Joceylyne Bloch, MD, associate professor, University of Lausanne and University Hospital Lausanne.

At this stage, not all paralyzed patients are eligible for the procedure. Dr. Bloch explained that at least 6 cm of healthy spinal cord under the lesion is needed to implant the electrodes.

“There’s a huge variability of spinal cord anatomy between individuals. That’s why it’s important to study each person individually and to have individual models in order to be precise.”

Researchers envision having “a library of electrode arrays,” added Dr. Courtine. With preoperative imaging of the individual’s spinal cord, “the neurosurgeon can select the more appropriate electrode array for that specific patient.”

Dr. Courtine noted recovery of sensation with the system differs from one individual to another. One study participant, Michel Roccati, now 30, told the briefing he feels a contraction in his muscle during the stimulation.

Currently, only individuals whose injury is more than a year old are included in the study to ensure patients have “a stable lesion” and reached “a plateau of recovery,” said Dr. Bloch. However, animal models show intervening earlier might boost the benefits.

A patient’s age can influence the outcome, as younger patients are likely in better condition and more motivated than older patients, said Dr. Bloch. However, she noted patients closing in on 50 years have responded well to the therapy.

Such stimulation systems may prove useful in treating conditions typically associated with SCI, such as hypertension and bladder control, and perhaps also in patients with Parkinson’s disease, said Dr. Courtine.

The researchers plan to conduct another study that will include a next-generation pulse generator with features that make the stimulation even more effective and user friendly. A voice recognition system could eventually be connected to the system.

“The next step is a minicomputer that you implant in the body that communicates in real time with an external iPhone,” said Dr. Courtine.

ONWARD Medical, which developed the technology, has received a breakthrough device designation from the Food and Drug Administration. The company is in discussions with the FDA to carry out a clinical trial of the device in the United States.

A ‘huge step forward’

Peter J. Grahn, PhD, assistant professor, department of physical medicine and rehabilitation and department of neurologic surgery, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., an author of one of the 2018 studies, said this technology “is a huge step forward” and “really pushes the field.”

Compared with the device used in his study that’s designed to treat neuropathic pain, this new system “is much more capable of dynamic stimulation,” said Dr. Grahn. “You can tailor the stimulation based on which area of the spinal cord you want to target during a specific function.”

There has been “a lot of hope and hype” recently around stem cells and biological molecules that were supposed to be “magic pills” to cure spinal cord dysfunction, said Dr. Grahn. “I don’t think this is one of those.”

However, he questioned the researchers’ use of the word “walking.”

“They say independent stepping or walking is restored on day 1, but the graphs show day 1 function is having over 60% of their body weight supported when they’re taking these steps,” he said.

In addition, the “big question” is how this technology can “be distilled down” into an approach “applicable across rehabilitation centers,” said Dr. Grahn.

The study was supported by numerous organizations, including ONWARD Medical. Dr. Courtine and Dr. Bloch hold various patents in relation with the present work. Dr. Courtine is a consultant with ONWARD Medical, and he and Dr. Bloch are shareholders of ONWARD Medical, a company with direct relationships with the presented work. Dr. Grahn reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

(SCI), new research shows.

The study demonstrated that an epidural electrical stimulation (EES) system developed specifically for spinal cord injuries enabled three men with complete paralysis to stand, walk, cycle, swim, and move their torso within 1 day.

“Thanks to this technology, we have been able to target individuals with the most serious spinal cord injury, meaning those with clinically complete spinal cord injury, with no sensation and no movement in the legs,” Grégoire Courtine, PhD, professor of neuroscience and neurotechnology at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, University Hospital Lausanne (Switzerland), and the University of Lausanne, told reporters attending a press briefing.

The study was published online Feb. 7, 2022, in Nature Medicine.

More rapid, precise, effective

SCIs involve severed connections between the brain and extremities. To compensate for these lost connections, researchers have investigated stem cell therapy, brain-machine interfaces, and powered exoskeletons.

However, these approaches aren’t yet ready for prime time.

In the meantime, researchers discovered even patients with a “complete” injury may have low-functioning connections and started investigating epidural stimulators designed to treat chronic pain. Recent studies – including three published in 2018 – showed promise for these pain-related stimulators in patients with incomplete SCI.

But using such “repurposed” technology meant the electrode array was relatively narrow and short, “so we could not target all the regions of the spinal cord involving control of leg and trunk movements,” said Dr. Courtine. With the newer technology “we are much more precise, effective, and more rapid in delivering therapy.”

To develop this new approach, the researchers designed a paddle lead with an arrangement of electrodes that targets sacral, lumbar, and low-thoracic dorsal roots involved in leg and trunk movements. They also established a personalized computational framework that allows for optimal surgical placement of this paddle lead.

In addition, they developed software that renders the configuration of individualized activity–dependent stimulation programs rapid, simple, and predictable.

They tested these neurotechnologies in three men with complete sensorimotor paralysis as part of an ongoing clinical trial. The participants, aged 29, 32, and 41 years, suffered an SCI from a motor bike accident 3, 9, and 1 year before enrollment.

All three patients exhibited complete sensorimotor paralysis. They were unable to take any step, and muscles remained quiescent during these attempts.

A neurosurgeon implanted electrodes along the spinal cord of study subjects. Wires from these electrodes were connected to a neurostimulator implanted under the skin in the abdomen.

The men can select different activity-based programs from a tablet that sends signals to the implanted device.

Personalized approach

Within a single day of the surgery, the participants were able to stand, walk, cycle, swim, and control trunk movements.

“It was not perfect at the very beginning, but they could train very early on to have a more fluid gait,” said study investigator neurosurgeon Joceylyne Bloch, MD, associate professor, University of Lausanne and University Hospital Lausanne.

At this stage, not all paralyzed patients are eligible for the procedure. Dr. Bloch explained that at least 6 cm of healthy spinal cord under the lesion is needed to implant the electrodes.

“There’s a huge variability of spinal cord anatomy between individuals. That’s why it’s important to study each person individually and to have individual models in order to be precise.”

Researchers envision having “a library of electrode arrays,” added Dr. Courtine. With preoperative imaging of the individual’s spinal cord, “the neurosurgeon can select the more appropriate electrode array for that specific patient.”

Dr. Courtine noted recovery of sensation with the system differs from one individual to another. One study participant, Michel Roccati, now 30, told the briefing he feels a contraction in his muscle during the stimulation.

Currently, only individuals whose injury is more than a year old are included in the study to ensure patients have “a stable lesion” and reached “a plateau of recovery,” said Dr. Bloch. However, animal models show intervening earlier might boost the benefits.

A patient’s age can influence the outcome, as younger patients are likely in better condition and more motivated than older patients, said Dr. Bloch. However, she noted patients closing in on 50 years have responded well to the therapy.

Such stimulation systems may prove useful in treating conditions typically associated with SCI, such as hypertension and bladder control, and perhaps also in patients with Parkinson’s disease, said Dr. Courtine.

The researchers plan to conduct another study that will include a next-generation pulse generator with features that make the stimulation even more effective and user friendly. A voice recognition system could eventually be connected to the system.

“The next step is a minicomputer that you implant in the body that communicates in real time with an external iPhone,” said Dr. Courtine.

ONWARD Medical, which developed the technology, has received a breakthrough device designation from the Food and Drug Administration. The company is in discussions with the FDA to carry out a clinical trial of the device in the United States.

A ‘huge step forward’

Peter J. Grahn, PhD, assistant professor, department of physical medicine and rehabilitation and department of neurologic surgery, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., an author of one of the 2018 studies, said this technology “is a huge step forward” and “really pushes the field.”

Compared with the device used in his study that’s designed to treat neuropathic pain, this new system “is much more capable of dynamic stimulation,” said Dr. Grahn. “You can tailor the stimulation based on which area of the spinal cord you want to target during a specific function.”

There has been “a lot of hope and hype” recently around stem cells and biological molecules that were supposed to be “magic pills” to cure spinal cord dysfunction, said Dr. Grahn. “I don’t think this is one of those.”

However, he questioned the researchers’ use of the word “walking.”

“They say independent stepping or walking is restored on day 1, but the graphs show day 1 function is having over 60% of their body weight supported when they’re taking these steps,” he said.

In addition, the “big question” is how this technology can “be distilled down” into an approach “applicable across rehabilitation centers,” said Dr. Grahn.

The study was supported by numerous organizations, including ONWARD Medical. Dr. Courtine and Dr. Bloch hold various patents in relation with the present work. Dr. Courtine is a consultant with ONWARD Medical, and he and Dr. Bloch are shareholders of ONWARD Medical, a company with direct relationships with the presented work. Dr. Grahn reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM NATURE MEDICINE

Cement found in man’s heart after spinal surgery

, according to a new report published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The 56-year-old man, who was not identified in the report, went to the emergency room after experiencing 2 days of chest pain and shortness of breath. Imaging scans showed that the chest pain was caused by a foreign object, and he was rushed to surgery.

Surgeons then located and removed a thin, sharp, cylindrical piece of cement and repaired the damage to the patient’s heart. The cement had pierced the upper right chamber of his heart and his right lung, according to the report authors from the Yale University School of Medicine.

A week before, the man had undergone a spinal surgery known as kyphoplasty. The procedure treats spine injuries by injecting a special type of medical cement into damaged vertebrae, according to USA Today. The cement had leaked into the patient’s body, hardened, and traveled to his heart.

The man has now “nearly recovered” since the heart surgery and cement removal, which occurred about a month ago, the journal report stated. He experienced no additional complications.

Cement leakage after kyphoplasty can happen but is an extremely rare complication. Less than 2% of patients who undergo the procedure for osteoporosis or brittle bones have complications, according to patient information from the American Association of Neurological Surgeons.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

, according to a new report published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The 56-year-old man, who was not identified in the report, went to the emergency room after experiencing 2 days of chest pain and shortness of breath. Imaging scans showed that the chest pain was caused by a foreign object, and he was rushed to surgery.

Surgeons then located and removed a thin, sharp, cylindrical piece of cement and repaired the damage to the patient’s heart. The cement had pierced the upper right chamber of his heart and his right lung, according to the report authors from the Yale University School of Medicine.

A week before, the man had undergone a spinal surgery known as kyphoplasty. The procedure treats spine injuries by injecting a special type of medical cement into damaged vertebrae, according to USA Today. The cement had leaked into the patient’s body, hardened, and traveled to his heart.

The man has now “nearly recovered” since the heart surgery and cement removal, which occurred about a month ago, the journal report stated. He experienced no additional complications.

Cement leakage after kyphoplasty can happen but is an extremely rare complication. Less than 2% of patients who undergo the procedure for osteoporosis or brittle bones have complications, according to patient information from the American Association of Neurological Surgeons.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

, according to a new report published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The 56-year-old man, who was not identified in the report, went to the emergency room after experiencing 2 days of chest pain and shortness of breath. Imaging scans showed that the chest pain was caused by a foreign object, and he was rushed to surgery.

Surgeons then located and removed a thin, sharp, cylindrical piece of cement and repaired the damage to the patient’s heart. The cement had pierced the upper right chamber of his heart and his right lung, according to the report authors from the Yale University School of Medicine.

A week before, the man had undergone a spinal surgery known as kyphoplasty. The procedure treats spine injuries by injecting a special type of medical cement into damaged vertebrae, according to USA Today. The cement had leaked into the patient’s body, hardened, and traveled to his heart.

The man has now “nearly recovered” since the heart surgery and cement removal, which occurred about a month ago, the journal report stated. He experienced no additional complications.

Cement leakage after kyphoplasty can happen but is an extremely rare complication. Less than 2% of patients who undergo the procedure for osteoporosis or brittle bones have complications, according to patient information from the American Association of Neurological Surgeons.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Near-hanging injuries: Critical care, psychiatric management

Suicide by hanging results in many deaths, and half of those survivors who are admitted later die from cardiac arrest.

Although hanging is a common form of suicide, studies of the clinical outcomes of near-hanging injury are rare. To address this void, Louise de Charentenay, MD, of the Medical-Surgical Intensive Care Unit, Centre Hospitalier de Versailles (France) and colleagues examined the vital and functional outcomes of more than 800 patients with suicidal near-hanging injury over 2 decades. Despite the high in-hospital mortality rate among survivors, those who do survive have an excellent chance of a full neurocognitive recovery. The investigators published their findings in Chest.

New data on near-hanging injuries

Near hanging refers to strangulation or hanging that doesn’t immediately lead to death. Little data have been available on this subject, particularly on the morbidity and mortality of patients admitted to the ICU following near-hanging injuries. In a retrospective analysis spanning 23 years (1992-2014), researchers looked at outcomes and early predictors of hospital deaths in patients with this injury. The study included 886 adult patients who were admitted to 31 university or university-affiliated ICUs in France and Belgium following successful resuscitation of suicidal near-hanging injury.

Investigators used logistic multivariate regression to report vital and functional outcomes at hospital discharge as a primary objective. They also aimed to identify predictors of hospital mortality in these patients.

Among all patients, 450 (50.8%) had hanging-induced cardiac arrest and of these, 371 (95.4%) eventually died. Although the rate of crude hospital deaths decreased over the 23-year period, hanging-induced cardiac arrest emerged as the strongest predictor of hospital mortality, followed by high blood lactate and hyperglycemia at ICU admission. “Hanging-induced cardiac arrest and worse consciousness impairment at ICU admission are directly related to the hanging, whereas higher glycemia and lactate levels at ICU admission represent biochemical markers of physiologic perturbation and injury severity that may suggest avenues for improvement in prehospital care,” wrote the investigators.

More than 56% of the patients survived to discharge, with a majority achieving favorable outcomes (a Glasgow Outcome Scale scores of 4 or 5 at discharge).

‘COVID-lateral’ damage and ICU management

Casey D. Bryant, MD, of the department of anesthesiology and the department of emergency medicine at Wake Forest Baptist Health, Winston-Salem, N.C., has treated these patients in the ICU and is prepared to see more of them in light of the current situation. He said in an interview, “The “COVID-lateral” damage being unleashed on the population as a result of increased isolation, lack of access to resources, higher unemployment, and increased substance abuse was detailed recently in an article by one of my colleagues, Dr. Seth Hawkins (Emerg Med News. 2020 Jun;42[6]:1,31-2). According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, hanging is the second leading cause of suicide in the United States, and one can only assume that with increased mental health crises there will also be an increased number of hanging attempts.”

Dr. Bryant suggested that the first task of doctors who learn that a near-hanging patient has been admitted is to “recover from the gut-punch you feel when you learn that a fellow human has tried to take their own life.” Once one is composed, he said, the first order of business is to come up with a treatment plan, one that typically begins with the airway. “These patients are at a high risk for cervical vertebrae injury (e.g., hangman’s fracture), spinal cord injury, tracheal injury, and neck vessel injury or dissection, so care must be taken to maintain in-line stabilization and limit movement of the neck during intubation while also being prepared for all manner of airway disasters. After airway management, addressing traumatic injuries, and initial stabilization, the focus then shifts to ‘bread and butter’ critical care, including optimization of ventilator management, titration of analgosedation, providing adequate nutrition, and strict avoidance of hypoxia, hypotension, fever, and either hyper- or hypoglycemia.”

Dr. Bryant noted that targeted temperature management prescriptions remain an area of debate in those with comatose state after hanging, but fever should absolutely be avoided. He added: “As the path to recovery begins to be forged, the full gamut of mental health resources should be provided to the patients in order to give them the best chance for success once they leave the ICU, and ultimately the hospital.”

The different hospitals seemed to have varying degrees of success in saving these patients, which is surprising, Mangala Narasimhan, DO, FCCP, regional director of critical care, director of the acute lung injury/ECMO center at Northwell and a professor of medicine at the Hofstra/Northwell School of Medicine, New York, said in an interview. “Usually, the death rate for cardiac arrest is high and the death rate for hanging is high. But here, it was high in some places and low in others.” Different time frames from presenting from hanging and different treatments may explain this, said Dr. Narasimhan.

Patient characteristics

Consistent with previous research, near-hanging patients are predominantly male, have at least one psychiatric diagnosis and a previous suicidal attempt (rarely by hanging), and abuse substances such as an alcohol, Stéphane Legriel, MD, PhD, the study’s corresponding author, said in an interview. Overall, 67.7% of the patients had a diagnosed mental illness and 30% had previously attempted suicide. Most of the hangings took place at home (79%), while some took place in a hospital ward (6%), a correctional facility (7%), or outside (5%).

The study had several limitations: It applied only to near-hanging patients admitted to the ICU, and its long duration may have resulted in heterogeneity of the population and therapeutic interventions, and in some missing data. “However, the multivariate analysis was adjusted for the time period and we carried out a sensitivity analysis after multiple imputation for missing data by means of chained equations, which reinforces confidence in our findings,” Dr. Legriel said. Next steps are to conduct a prospective data collection.

Postdischarge recovery and psychiatric follow-up

Those left to treat survivors of near-hangings are psychiatrists and other mental health clinicians, Eric M. Plakun, MD, said in an interview.

“Some of these survivors will regret they survived and remain high suicide risks. Some will feel their lives are transformed or at least no longer as intensely drawn to suicide as a solution to a life filled with the impact of adversity, trauma, comorbidity, and other struggles – but even these individuals will still have to face the often complex underlying issues that led them to choose suicide as a solution,” said Dr. Plakun, medical director and CEO of the Austen Riggs Center in Stockbridge, Mass.

Patients with medically serious suicide attempts are seen a lot at Austen Riggs, he said, because acute inpatient settings are designed for brief, crisis-focused treatment of those for whom safety is an issue. After the crisis has been stabilized, patients are discharged, and then must begin to achieve recovery as outpatients, he said.

John Kruse, MD, PhD, a psychiatrist who practices in San Francisco, praised the size and the breath of the study. “One limitation was the reliance on hospital records, without an opportunity to directly evaluate or interview the patients involved.”

The authors disclosed no conflicts of interest. The study received grant support from the French public funding agency, Délégation la Recherche Clinique et de l’Innovation in Versailles, France.

SOURCE: de Charentenay L et al. 2020 Aug 3. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.07.064

Suicide by hanging results in many deaths, and half of those survivors who are admitted later die from cardiac arrest.

Although hanging is a common form of suicide, studies of the clinical outcomes of near-hanging injury are rare. To address this void, Louise de Charentenay, MD, of the Medical-Surgical Intensive Care Unit, Centre Hospitalier de Versailles (France) and colleagues examined the vital and functional outcomes of more than 800 patients with suicidal near-hanging injury over 2 decades. Despite the high in-hospital mortality rate among survivors, those who do survive have an excellent chance of a full neurocognitive recovery. The investigators published their findings in Chest.

New data on near-hanging injuries

Near hanging refers to strangulation or hanging that doesn’t immediately lead to death. Little data have been available on this subject, particularly on the morbidity and mortality of patients admitted to the ICU following near-hanging injuries. In a retrospective analysis spanning 23 years (1992-2014), researchers looked at outcomes and early predictors of hospital deaths in patients with this injury. The study included 886 adult patients who were admitted to 31 university or university-affiliated ICUs in France and Belgium following successful resuscitation of suicidal near-hanging injury.

Investigators used logistic multivariate regression to report vital and functional outcomes at hospital discharge as a primary objective. They also aimed to identify predictors of hospital mortality in these patients.

Among all patients, 450 (50.8%) had hanging-induced cardiac arrest and of these, 371 (95.4%) eventually died. Although the rate of crude hospital deaths decreased over the 23-year period, hanging-induced cardiac arrest emerged as the strongest predictor of hospital mortality, followed by high blood lactate and hyperglycemia at ICU admission. “Hanging-induced cardiac arrest and worse consciousness impairment at ICU admission are directly related to the hanging, whereas higher glycemia and lactate levels at ICU admission represent biochemical markers of physiologic perturbation and injury severity that may suggest avenues for improvement in prehospital care,” wrote the investigators.

More than 56% of the patients survived to discharge, with a majority achieving favorable outcomes (a Glasgow Outcome Scale scores of 4 or 5 at discharge).

‘COVID-lateral’ damage and ICU management

Casey D. Bryant, MD, of the department of anesthesiology and the department of emergency medicine at Wake Forest Baptist Health, Winston-Salem, N.C., has treated these patients in the ICU and is prepared to see more of them in light of the current situation. He said in an interview, “The “COVID-lateral” damage being unleashed on the population as a result of increased isolation, lack of access to resources, higher unemployment, and increased substance abuse was detailed recently in an article by one of my colleagues, Dr. Seth Hawkins (Emerg Med News. 2020 Jun;42[6]:1,31-2). According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, hanging is the second leading cause of suicide in the United States, and one can only assume that with increased mental health crises there will also be an increased number of hanging attempts.”

Dr. Bryant suggested that the first task of doctors who learn that a near-hanging patient has been admitted is to “recover from the gut-punch you feel when you learn that a fellow human has tried to take their own life.” Once one is composed, he said, the first order of business is to come up with a treatment plan, one that typically begins with the airway. “These patients are at a high risk for cervical vertebrae injury (e.g., hangman’s fracture), spinal cord injury, tracheal injury, and neck vessel injury or dissection, so care must be taken to maintain in-line stabilization and limit movement of the neck during intubation while also being prepared for all manner of airway disasters. After airway management, addressing traumatic injuries, and initial stabilization, the focus then shifts to ‘bread and butter’ critical care, including optimization of ventilator management, titration of analgosedation, providing adequate nutrition, and strict avoidance of hypoxia, hypotension, fever, and either hyper- or hypoglycemia.”

Dr. Bryant noted that targeted temperature management prescriptions remain an area of debate in those with comatose state after hanging, but fever should absolutely be avoided. He added: “As the path to recovery begins to be forged, the full gamut of mental health resources should be provided to the patients in order to give them the best chance for success once they leave the ICU, and ultimately the hospital.”

The different hospitals seemed to have varying degrees of success in saving these patients, which is surprising, Mangala Narasimhan, DO, FCCP, regional director of critical care, director of the acute lung injury/ECMO center at Northwell and a professor of medicine at the Hofstra/Northwell School of Medicine, New York, said in an interview. “Usually, the death rate for cardiac arrest is high and the death rate for hanging is high. But here, it was high in some places and low in others.” Different time frames from presenting from hanging and different treatments may explain this, said Dr. Narasimhan.

Patient characteristics

Consistent with previous research, near-hanging patients are predominantly male, have at least one psychiatric diagnosis and a previous suicidal attempt (rarely by hanging), and abuse substances such as an alcohol, Stéphane Legriel, MD, PhD, the study’s corresponding author, said in an interview. Overall, 67.7% of the patients had a diagnosed mental illness and 30% had previously attempted suicide. Most of the hangings took place at home (79%), while some took place in a hospital ward (6%), a correctional facility (7%), or outside (5%).

The study had several limitations: It applied only to near-hanging patients admitted to the ICU, and its long duration may have resulted in heterogeneity of the population and therapeutic interventions, and in some missing data. “However, the multivariate analysis was adjusted for the time period and we carried out a sensitivity analysis after multiple imputation for missing data by means of chained equations, which reinforces confidence in our findings,” Dr. Legriel said. Next steps are to conduct a prospective data collection.

Postdischarge recovery and psychiatric follow-up

Those left to treat survivors of near-hangings are psychiatrists and other mental health clinicians, Eric M. Plakun, MD, said in an interview.

“Some of these survivors will regret they survived and remain high suicide risks. Some will feel their lives are transformed or at least no longer as intensely drawn to suicide as a solution to a life filled with the impact of adversity, trauma, comorbidity, and other struggles – but even these individuals will still have to face the often complex underlying issues that led them to choose suicide as a solution,” said Dr. Plakun, medical director and CEO of the Austen Riggs Center in Stockbridge, Mass.

Patients with medically serious suicide attempts are seen a lot at Austen Riggs, he said, because acute inpatient settings are designed for brief, crisis-focused treatment of those for whom safety is an issue. After the crisis has been stabilized, patients are discharged, and then must begin to achieve recovery as outpatients, he said.

John Kruse, MD, PhD, a psychiatrist who practices in San Francisco, praised the size and the breath of the study. “One limitation was the reliance on hospital records, without an opportunity to directly evaluate or interview the patients involved.”

The authors disclosed no conflicts of interest. The study received grant support from the French public funding agency, Délégation la Recherche Clinique et de l’Innovation in Versailles, France.

SOURCE: de Charentenay L et al. 2020 Aug 3. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.07.064

Suicide by hanging results in many deaths, and half of those survivors who are admitted later die from cardiac arrest.

Although hanging is a common form of suicide, studies of the clinical outcomes of near-hanging injury are rare. To address this void, Louise de Charentenay, MD, of the Medical-Surgical Intensive Care Unit, Centre Hospitalier de Versailles (France) and colleagues examined the vital and functional outcomes of more than 800 patients with suicidal near-hanging injury over 2 decades. Despite the high in-hospital mortality rate among survivors, those who do survive have an excellent chance of a full neurocognitive recovery. The investigators published their findings in Chest.

New data on near-hanging injuries

Near hanging refers to strangulation or hanging that doesn’t immediately lead to death. Little data have been available on this subject, particularly on the morbidity and mortality of patients admitted to the ICU following near-hanging injuries. In a retrospective analysis spanning 23 years (1992-2014), researchers looked at outcomes and early predictors of hospital deaths in patients with this injury. The study included 886 adult patients who were admitted to 31 university or university-affiliated ICUs in France and Belgium following successful resuscitation of suicidal near-hanging injury.

Investigators used logistic multivariate regression to report vital and functional outcomes at hospital discharge as a primary objective. They also aimed to identify predictors of hospital mortality in these patients.

Among all patients, 450 (50.8%) had hanging-induced cardiac arrest and of these, 371 (95.4%) eventually died. Although the rate of crude hospital deaths decreased over the 23-year period, hanging-induced cardiac arrest emerged as the strongest predictor of hospital mortality, followed by high blood lactate and hyperglycemia at ICU admission. “Hanging-induced cardiac arrest and worse consciousness impairment at ICU admission are directly related to the hanging, whereas higher glycemia and lactate levels at ICU admission represent biochemical markers of physiologic perturbation and injury severity that may suggest avenues for improvement in prehospital care,” wrote the investigators.

More than 56% of the patients survived to discharge, with a majority achieving favorable outcomes (a Glasgow Outcome Scale scores of 4 or 5 at discharge).

‘COVID-lateral’ damage and ICU management

Casey D. Bryant, MD, of the department of anesthesiology and the department of emergency medicine at Wake Forest Baptist Health, Winston-Salem, N.C., has treated these patients in the ICU and is prepared to see more of them in light of the current situation. He said in an interview, “The “COVID-lateral” damage being unleashed on the population as a result of increased isolation, lack of access to resources, higher unemployment, and increased substance abuse was detailed recently in an article by one of my colleagues, Dr. Seth Hawkins (Emerg Med News. 2020 Jun;42[6]:1,31-2). According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, hanging is the second leading cause of suicide in the United States, and one can only assume that with increased mental health crises there will also be an increased number of hanging attempts.”

Dr. Bryant suggested that the first task of doctors who learn that a near-hanging patient has been admitted is to “recover from the gut-punch you feel when you learn that a fellow human has tried to take their own life.” Once one is composed, he said, the first order of business is to come up with a treatment plan, one that typically begins with the airway. “These patients are at a high risk for cervical vertebrae injury (e.g., hangman’s fracture), spinal cord injury, tracheal injury, and neck vessel injury or dissection, so care must be taken to maintain in-line stabilization and limit movement of the neck during intubation while also being prepared for all manner of airway disasters. After airway management, addressing traumatic injuries, and initial stabilization, the focus then shifts to ‘bread and butter’ critical care, including optimization of ventilator management, titration of analgosedation, providing adequate nutrition, and strict avoidance of hypoxia, hypotension, fever, and either hyper- or hypoglycemia.”

Dr. Bryant noted that targeted temperature management prescriptions remain an area of debate in those with comatose state after hanging, but fever should absolutely be avoided. He added: “As the path to recovery begins to be forged, the full gamut of mental health resources should be provided to the patients in order to give them the best chance for success once they leave the ICU, and ultimately the hospital.”

The different hospitals seemed to have varying degrees of success in saving these patients, which is surprising, Mangala Narasimhan, DO, FCCP, regional director of critical care, director of the acute lung injury/ECMO center at Northwell and a professor of medicine at the Hofstra/Northwell School of Medicine, New York, said in an interview. “Usually, the death rate for cardiac arrest is high and the death rate for hanging is high. But here, it was high in some places and low in others.” Different time frames from presenting from hanging and different treatments may explain this, said Dr. Narasimhan.

Patient characteristics

Consistent with previous research, near-hanging patients are predominantly male, have at least one psychiatric diagnosis and a previous suicidal attempt (rarely by hanging), and abuse substances such as an alcohol, Stéphane Legriel, MD, PhD, the study’s corresponding author, said in an interview. Overall, 67.7% of the patients had a diagnosed mental illness and 30% had previously attempted suicide. Most of the hangings took place at home (79%), while some took place in a hospital ward (6%), a correctional facility (7%), or outside (5%).

The study had several limitations: It applied only to near-hanging patients admitted to the ICU, and its long duration may have resulted in heterogeneity of the population and therapeutic interventions, and in some missing data. “However, the multivariate analysis was adjusted for the time period and we carried out a sensitivity analysis after multiple imputation for missing data by means of chained equations, which reinforces confidence in our findings,” Dr. Legriel said. Next steps are to conduct a prospective data collection.

Postdischarge recovery and psychiatric follow-up

Those left to treat survivors of near-hangings are psychiatrists and other mental health clinicians, Eric M. Plakun, MD, said in an interview.

“Some of these survivors will regret they survived and remain high suicide risks. Some will feel their lives are transformed or at least no longer as intensely drawn to suicide as a solution to a life filled with the impact of adversity, trauma, comorbidity, and other struggles – but even these individuals will still have to face the often complex underlying issues that led them to choose suicide as a solution,” said Dr. Plakun, medical director and CEO of the Austen Riggs Center in Stockbridge, Mass.

Patients with medically serious suicide attempts are seen a lot at Austen Riggs, he said, because acute inpatient settings are designed for brief, crisis-focused treatment of those for whom safety is an issue. After the crisis has been stabilized, patients are discharged, and then must begin to achieve recovery as outpatients, he said.

John Kruse, MD, PhD, a psychiatrist who practices in San Francisco, praised the size and the breath of the study. “One limitation was the reliance on hospital records, without an opportunity to directly evaluate or interview the patients involved.”

The authors disclosed no conflicts of interest. The study received grant support from the French public funding agency, Délégation la Recherche Clinique et de l’Innovation in Versailles, France.

SOURCE: de Charentenay L et al. 2020 Aug 3. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.07.064

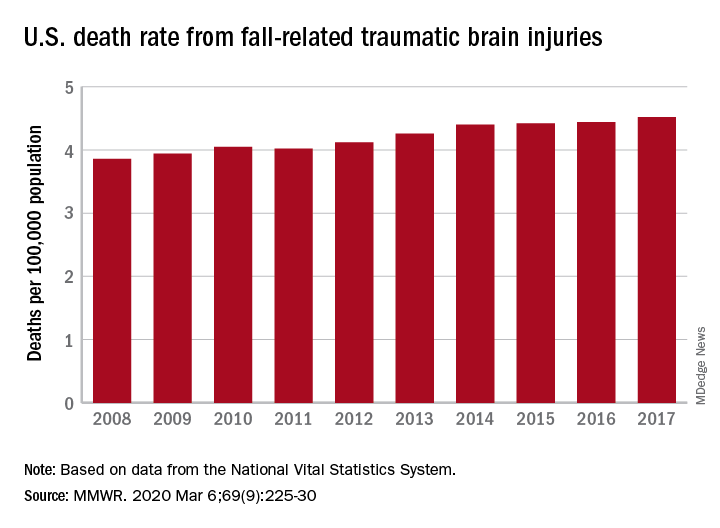

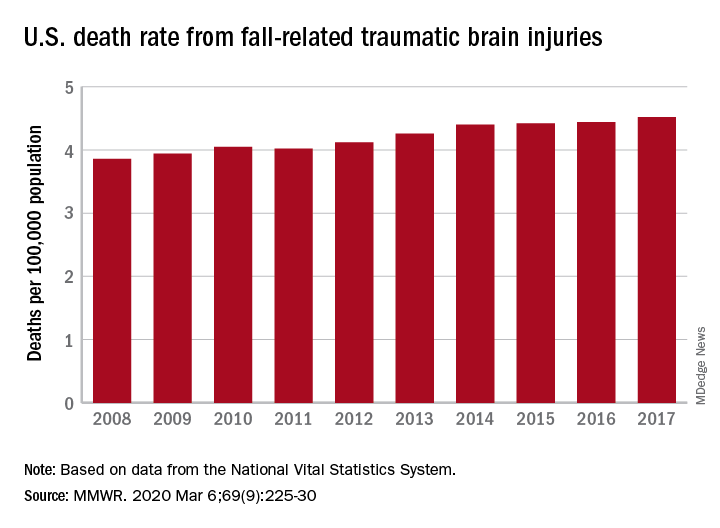

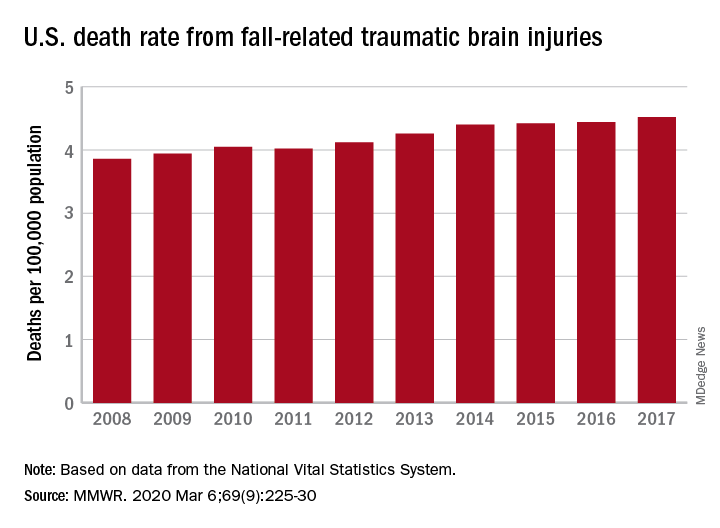

TBI deaths from falls on the rise

A 17% surge in mortality from fall-related traumatic brain injuries from 2008 to 2017 was driven largely by increases among those aged 75 years and older, according to investigators from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Nationally, the rate of deaths from traumatic brain injuries (TBIs) caused by unintentional falls rose from 3.86 per 100,000 population in 2008 to 4.52 per 100,000 in 2017, as the number of deaths went from 12,311 to 17,408, said Alexis B. Peterson, PhD, and Scott R. Kegler, PhD, of the CDC’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control in Atlanta.

“This increase might be explained by longer survival following the onset of common diseases such as stroke, cancer, and heart disease or be attributable to the increasing population of older adults in the United States,” they suggested in the Mortality and Morbidity Weekly Report.

The rate of fall-related TBI among Americans aged 75 years and older increased by an average of 2.6% per year from 2008 to 2017, compared with 1.8% in those aged 55-74. Over that same time, death rates dropped for those aged 35-44 (–0.3%), 18-34 (–1.1%), and 0-17 (–4.3%), they said, based on data from the National Vital Statistics System’s multiple cause-of-death database.

The death rate increased fastest in residents of rural areas (2.9% per year), but deaths from fall-related TBI were up at all levels of urbanization. The largest central cities and fringe metro areas were up by 1.4% a year, with larger annual increases seen in medium-size cities (2.1%), small cities (2.2%), and small towns (2.1%), Dr. Peterson and Dr. Kegler said.

Rates of TBI-related mortality in general are higher in rural areas, they noted, and “heterogeneity in the availability and accessibility of resources (e.g., access to high-level trauma centers and rehabilitative services) can result in disparities in postinjury outcomes.”

State-specific rates increased in 45 states, although Alaska was excluded from the analysis because of its small number of cases (less than 20). Increases were significant in 29 states, but none of the changes were significant in the 4 states with lower rates at the end of the study period, the investigators reported.

“In older adults, evidence-based fall prevention strategies can prevent falls and avert costly medical expenditures,” Dr. Peterson and Dr. Kegler said, suggesting that health care providers “consider prescribing exercises that incorporate balance, strength and gait activities, such as tai chi, and reviewing and managing medications linked to falls.”

SOURCE: Peterson AB, Kegler SR. MMWR. 2019 Mar 6;69(9):225-30.

A 17% surge in mortality from fall-related traumatic brain injuries from 2008 to 2017 was driven largely by increases among those aged 75 years and older, according to investigators from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Nationally, the rate of deaths from traumatic brain injuries (TBIs) caused by unintentional falls rose from 3.86 per 100,000 population in 2008 to 4.52 per 100,000 in 2017, as the number of deaths went from 12,311 to 17,408, said Alexis B. Peterson, PhD, and Scott R. Kegler, PhD, of the CDC’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control in Atlanta.

“This increase might be explained by longer survival following the onset of common diseases such as stroke, cancer, and heart disease or be attributable to the increasing population of older adults in the United States,” they suggested in the Mortality and Morbidity Weekly Report.

The rate of fall-related TBI among Americans aged 75 years and older increased by an average of 2.6% per year from 2008 to 2017, compared with 1.8% in those aged 55-74. Over that same time, death rates dropped for those aged 35-44 (–0.3%), 18-34 (–1.1%), and 0-17 (–4.3%), they said, based on data from the National Vital Statistics System’s multiple cause-of-death database.

The death rate increased fastest in residents of rural areas (2.9% per year), but deaths from fall-related TBI were up at all levels of urbanization. The largest central cities and fringe metro areas were up by 1.4% a year, with larger annual increases seen in medium-size cities (2.1%), small cities (2.2%), and small towns (2.1%), Dr. Peterson and Dr. Kegler said.

Rates of TBI-related mortality in general are higher in rural areas, they noted, and “heterogeneity in the availability and accessibility of resources (e.g., access to high-level trauma centers and rehabilitative services) can result in disparities in postinjury outcomes.”

State-specific rates increased in 45 states, although Alaska was excluded from the analysis because of its small number of cases (less than 20). Increases were significant in 29 states, but none of the changes were significant in the 4 states with lower rates at the end of the study period, the investigators reported.

“In older adults, evidence-based fall prevention strategies can prevent falls and avert costly medical expenditures,” Dr. Peterson and Dr. Kegler said, suggesting that health care providers “consider prescribing exercises that incorporate balance, strength and gait activities, such as tai chi, and reviewing and managing medications linked to falls.”

SOURCE: Peterson AB, Kegler SR. MMWR. 2019 Mar 6;69(9):225-30.

A 17% surge in mortality from fall-related traumatic brain injuries from 2008 to 2017 was driven largely by increases among those aged 75 years and older, according to investigators from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Nationally, the rate of deaths from traumatic brain injuries (TBIs) caused by unintentional falls rose from 3.86 per 100,000 population in 2008 to 4.52 per 100,000 in 2017, as the number of deaths went from 12,311 to 17,408, said Alexis B. Peterson, PhD, and Scott R. Kegler, PhD, of the CDC’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control in Atlanta.

“This increase might be explained by longer survival following the onset of common diseases such as stroke, cancer, and heart disease or be attributable to the increasing population of older adults in the United States,” they suggested in the Mortality and Morbidity Weekly Report.

The rate of fall-related TBI among Americans aged 75 years and older increased by an average of 2.6% per year from 2008 to 2017, compared with 1.8% in those aged 55-74. Over that same time, death rates dropped for those aged 35-44 (–0.3%), 18-34 (–1.1%), and 0-17 (–4.3%), they said, based on data from the National Vital Statistics System’s multiple cause-of-death database.

The death rate increased fastest in residents of rural areas (2.9% per year), but deaths from fall-related TBI were up at all levels of urbanization. The largest central cities and fringe metro areas were up by 1.4% a year, with larger annual increases seen in medium-size cities (2.1%), small cities (2.2%), and small towns (2.1%), Dr. Peterson and Dr. Kegler said.

Rates of TBI-related mortality in general are higher in rural areas, they noted, and “heterogeneity in the availability and accessibility of resources (e.g., access to high-level trauma centers and rehabilitative services) can result in disparities in postinjury outcomes.”

State-specific rates increased in 45 states, although Alaska was excluded from the analysis because of its small number of cases (less than 20). Increases were significant in 29 states, but none of the changes were significant in the 4 states with lower rates at the end of the study period, the investigators reported.

“In older adults, evidence-based fall prevention strategies can prevent falls and avert costly medical expenditures,” Dr. Peterson and Dr. Kegler said, suggesting that health care providers “consider prescribing exercises that incorporate balance, strength and gait activities, such as tai chi, and reviewing and managing medications linked to falls.”

SOURCE: Peterson AB, Kegler SR. MMWR. 2019 Mar 6;69(9):225-30.

FROM MMWR

Staged hemispheric embolization: How to treat hemimegalencephaly within days of birth

BALTIMORE – About one in 4,000 children are born with hemimegalencephaly, meaning one brain hemisphere is abnormally formed and larger than the other.

The abnormal hemisphere causes seizures, and when they become intractable, the standard of care is to remove it as soon as possible; the longer the abnormal hemisphere is left in, the worse children do developmentally, and the less likely hemispherectomy will stop the seizures.

A problem comes up, however, when children become intractable before they’re 3 months old: “Neurosurgeons won’t touch them,” said Taeun Chang, MD, a neonatal neurointensivist at Children’s National Medical Center in Washington.

Newborns’ coagulation systems aren’t fully developed, and the risk of fatal hemorrhage is too high, she explained.

Out of what she said was a sense of “desperation” to address the situation, Dr. Chang has spearheaded a new approach for newborns at Children’s National, serial glue embolization to induce targeted strokes in the affected hemisphere. She reported on the first five cases at the American Epilepsy Society annual meeting.

At this point, “I feel like we’ve pretty much figured out the technique in terms of minimizing the complications. There’s no reason to wait anymore” for surgery as newborns get worse and worse, she said.

The technique

In two or three stages over several days, the major branches of the affected hemisphere’s anterior, middle, and posterior cerebral arteries are embolized. “You have to glue a long area and put in a lot of glue and glue up the secondary branches because [newborns] are so good at forming collaterals,” Dr. Chang said.

Fresh frozen plasma is given before and after each embolization session to boost coagulation proteins. Nicardipine is given during the procedure to prevent vasospasms. The one death in the series, case four, was in an 11-day old girl who vasospasmed, ruptured an artery over the tip of the guidewire, and hemorrhaged.

After the procedure, body temperature is kept at 36° C to prevent fever; sodium is kept high, and ins and outs are matched, to reduce brain edema; and blood pressure is tightly controlled. Children are kept on EEG during embolization and for days afterwards, and seizures, if any, are treated. The next embolization comes after peak swelling has passed in about 48-72 hours.

“The reason we can get away with this without herniation is that newborns’ skulls are soft, and their sutures are open,” so cerebral edema is manageable, Dr. Chang said.

Learning curve and outcomes

“What we learned in the first two cases” – a 23-day-old boy and 49-day-old girl – “was to create effective strokes. That’s not something any of us are taught to do,” she said.

“We were not trying to destroy the whole hemisphere, just the area that was seizing on EEG.” That was a mistake, she said: Adjacent areas began seizing and both children went on to anatomical hemispherectomies and needed shunts.

They are 5 years old now, and both on four seizure medications. The boy is in a wheelchair, fed by a G-tube, and has fewer than 20 words. The girl has a gait trainer, is fed mostly by G-tube, and has more than 50 words.

The third patient had her middle and posterior cerebral arteries embolized beginning when she was 43 days old. She was seizure free when she left the NICU, but eventually had a functional hemispherectomy. She’s 2 years old now, eating by mouth, in a gait trainer, and speaks in one- or two-word sentences. She’s on three seizure medications.

Outcomes have been best for patient five. Her posterior, middle, and anterior cerebral arteries were embolized starting at 14 days. She’s 1 year old now, seizure free on three medications, eating by G-tube and mouth, and has three-five words.

Dr. Chang said that newborns with hemimegalencephaly at Children’s National aren’t lingering as long on failing drug regimens these days. “We go to intervention now that we have this option” after they fail just two or three medications.

Given that the fifth patient, treated at 2 weeks old, is the only one who has been seizure free, she suspects it’s probably best to do embolization sooner rather than later, just as with anatomical hemispherectomy in older children. “We’ve got the sense that even a couple of weeks makes a difference. People need to come to us sooner,” Dr. Chang said.

It’s possible embolization could be a sound alternative to surgery even after 3 months of age. Focal embolization might also be a viable alternative to surgery to knock out epileptogenic lesions in children with tuberous sclerosis. Dr. Chang and her colleagues are interested in those and other possibilities, and plan to continue to develop the approach, she said.

There was no funding, and the investigators didn’t have any relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Chang T et al. AES 2019, Abstract 1.225.

BALTIMORE – About one in 4,000 children are born with hemimegalencephaly, meaning one brain hemisphere is abnormally formed and larger than the other.

The abnormal hemisphere causes seizures, and when they become intractable, the standard of care is to remove it as soon as possible; the longer the abnormal hemisphere is left in, the worse children do developmentally, and the less likely hemispherectomy will stop the seizures.

A problem comes up, however, when children become intractable before they’re 3 months old: “Neurosurgeons won’t touch them,” said Taeun Chang, MD, a neonatal neurointensivist at Children’s National Medical Center in Washington.

Newborns’ coagulation systems aren’t fully developed, and the risk of fatal hemorrhage is too high, she explained.

Out of what she said was a sense of “desperation” to address the situation, Dr. Chang has spearheaded a new approach for newborns at Children’s National, serial glue embolization to induce targeted strokes in the affected hemisphere. She reported on the first five cases at the American Epilepsy Society annual meeting.

At this point, “I feel like we’ve pretty much figured out the technique in terms of minimizing the complications. There’s no reason to wait anymore” for surgery as newborns get worse and worse, she said.

The technique

In two or three stages over several days, the major branches of the affected hemisphere’s anterior, middle, and posterior cerebral arteries are embolized. “You have to glue a long area and put in a lot of glue and glue up the secondary branches because [newborns] are so good at forming collaterals,” Dr. Chang said.

Fresh frozen plasma is given before and after each embolization session to boost coagulation proteins. Nicardipine is given during the procedure to prevent vasospasms. The one death in the series, case four, was in an 11-day old girl who vasospasmed, ruptured an artery over the tip of the guidewire, and hemorrhaged.

After the procedure, body temperature is kept at 36° C to prevent fever; sodium is kept high, and ins and outs are matched, to reduce brain edema; and blood pressure is tightly controlled. Children are kept on EEG during embolization and for days afterwards, and seizures, if any, are treated. The next embolization comes after peak swelling has passed in about 48-72 hours.

“The reason we can get away with this without herniation is that newborns’ skulls are soft, and their sutures are open,” so cerebral edema is manageable, Dr. Chang said.

Learning curve and outcomes

“What we learned in the first two cases” – a 23-day-old boy and 49-day-old girl – “was to create effective strokes. That’s not something any of us are taught to do,” she said.

“We were not trying to destroy the whole hemisphere, just the area that was seizing on EEG.” That was a mistake, she said: Adjacent areas began seizing and both children went on to anatomical hemispherectomies and needed shunts.

They are 5 years old now, and both on four seizure medications. The boy is in a wheelchair, fed by a G-tube, and has fewer than 20 words. The girl has a gait trainer, is fed mostly by G-tube, and has more than 50 words.

The third patient had her middle and posterior cerebral arteries embolized beginning when she was 43 days old. She was seizure free when she left the NICU, but eventually had a functional hemispherectomy. She’s 2 years old now, eating by mouth, in a gait trainer, and speaks in one- or two-word sentences. She’s on three seizure medications.

Outcomes have been best for patient five. Her posterior, middle, and anterior cerebral arteries were embolized starting at 14 days. She’s 1 year old now, seizure free on three medications, eating by G-tube and mouth, and has three-five words.

Dr. Chang said that newborns with hemimegalencephaly at Children’s National aren’t lingering as long on failing drug regimens these days. “We go to intervention now that we have this option” after they fail just two or three medications.

Given that the fifth patient, treated at 2 weeks old, is the only one who has been seizure free, she suspects it’s probably best to do embolization sooner rather than later, just as with anatomical hemispherectomy in older children. “We’ve got the sense that even a couple of weeks makes a difference. People need to come to us sooner,” Dr. Chang said.

It’s possible embolization could be a sound alternative to surgery even after 3 months of age. Focal embolization might also be a viable alternative to surgery to knock out epileptogenic lesions in children with tuberous sclerosis. Dr. Chang and her colleagues are interested in those and other possibilities, and plan to continue to develop the approach, she said.

There was no funding, and the investigators didn’t have any relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Chang T et al. AES 2019, Abstract 1.225.

BALTIMORE – About one in 4,000 children are born with hemimegalencephaly, meaning one brain hemisphere is abnormally formed and larger than the other.

The abnormal hemisphere causes seizures, and when they become intractable, the standard of care is to remove it as soon as possible; the longer the abnormal hemisphere is left in, the worse children do developmentally, and the less likely hemispherectomy will stop the seizures.

A problem comes up, however, when children become intractable before they’re 3 months old: “Neurosurgeons won’t touch them,” said Taeun Chang, MD, a neonatal neurointensivist at Children’s National Medical Center in Washington.

Newborns’ coagulation systems aren’t fully developed, and the risk of fatal hemorrhage is too high, she explained.

Out of what she said was a sense of “desperation” to address the situation, Dr. Chang has spearheaded a new approach for newborns at Children’s National, serial glue embolization to induce targeted strokes in the affected hemisphere. She reported on the first five cases at the American Epilepsy Society annual meeting.

At this point, “I feel like we’ve pretty much figured out the technique in terms of minimizing the complications. There’s no reason to wait anymore” for surgery as newborns get worse and worse, she said.

The technique

In two or three stages over several days, the major branches of the affected hemisphere’s anterior, middle, and posterior cerebral arteries are embolized. “You have to glue a long area and put in a lot of glue and glue up the secondary branches because [newborns] are so good at forming collaterals,” Dr. Chang said.

Fresh frozen plasma is given before and after each embolization session to boost coagulation proteins. Nicardipine is given during the procedure to prevent vasospasms. The one death in the series, case four, was in an 11-day old girl who vasospasmed, ruptured an artery over the tip of the guidewire, and hemorrhaged.

After the procedure, body temperature is kept at 36° C to prevent fever; sodium is kept high, and ins and outs are matched, to reduce brain edema; and blood pressure is tightly controlled. Children are kept on EEG during embolization and for days afterwards, and seizures, if any, are treated. The next embolization comes after peak swelling has passed in about 48-72 hours.

“The reason we can get away with this without herniation is that newborns’ skulls are soft, and their sutures are open,” so cerebral edema is manageable, Dr. Chang said.

Learning curve and outcomes

“What we learned in the first two cases” – a 23-day-old boy and 49-day-old girl – “was to create effective strokes. That’s not something any of us are taught to do,” she said.

“We were not trying to destroy the whole hemisphere, just the area that was seizing on EEG.” That was a mistake, she said: Adjacent areas began seizing and both children went on to anatomical hemispherectomies and needed shunts.

They are 5 years old now, and both on four seizure medications. The boy is in a wheelchair, fed by a G-tube, and has fewer than 20 words. The girl has a gait trainer, is fed mostly by G-tube, and has more than 50 words.

The third patient had her middle and posterior cerebral arteries embolized beginning when she was 43 days old. She was seizure free when she left the NICU, but eventually had a functional hemispherectomy. She’s 2 years old now, eating by mouth, in a gait trainer, and speaks in one- or two-word sentences. She’s on three seizure medications.

Outcomes have been best for patient five. Her posterior, middle, and anterior cerebral arteries were embolized starting at 14 days. She’s 1 year old now, seizure free on three medications, eating by G-tube and mouth, and has three-five words.

Dr. Chang said that newborns with hemimegalencephaly at Children’s National aren’t lingering as long on failing drug regimens these days. “We go to intervention now that we have this option” after they fail just two or three medications.

Given that the fifth patient, treated at 2 weeks old, is the only one who has been seizure free, she suspects it’s probably best to do embolization sooner rather than later, just as with anatomical hemispherectomy in older children. “We’ve got the sense that even a couple of weeks makes a difference. People need to come to us sooner,” Dr. Chang said.

It’s possible embolization could be a sound alternative to surgery even after 3 months of age. Focal embolization might also be a viable alternative to surgery to knock out epileptogenic lesions in children with tuberous sclerosis. Dr. Chang and her colleagues are interested in those and other possibilities, and plan to continue to develop the approach, she said.

There was no funding, and the investigators didn’t have any relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Chang T et al. AES 2019, Abstract 1.225.

REPORTING FROM AES 2019

Hyperphosphorylated tau visible in TBI survivors decades after brain injury

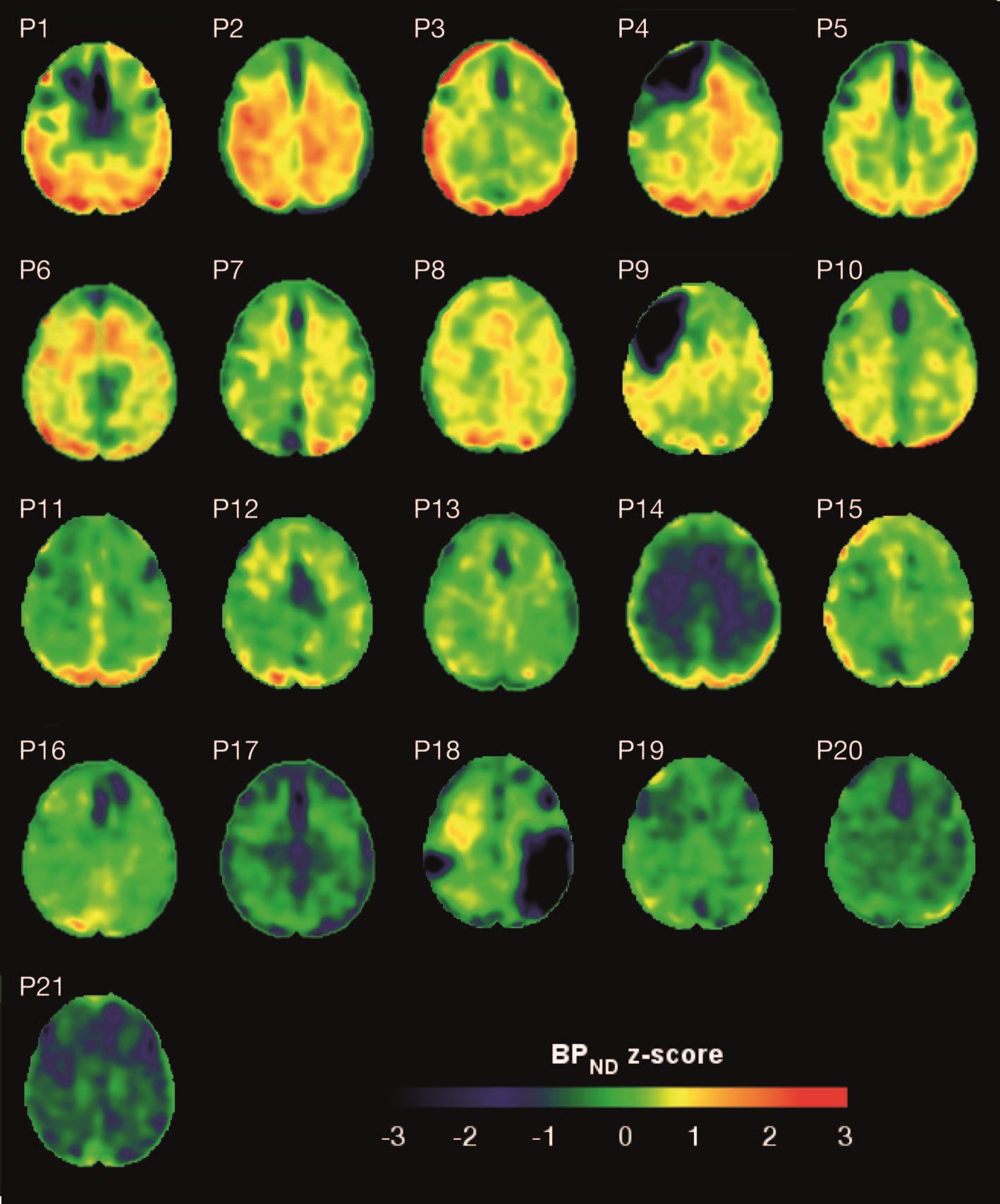

Brain deposits of hyperphosphorylated tau are detectable in traumatic brain injury (TBI) patients 18-51 years after a single moderate to severe incident occurred, researchers reported Sept. 4 in Science Translational Medicine.

Imaging with the tau-specific PET radioligand flortaucipir showed that the protein was most apparent in the right occipital cortex, and was associated with changes in cognitive scores, tau and beta amyloid in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and white matter density, Nikos Gorgoraptis, PhD, of Imperial College London and his colleagues wrote.

“The ability to detect tau pathology in vivo after TBI has major potential implications for diagnosis and prognostication of clinical outcomes after TBI,” the researchers explained. “It is also likely to assist in patient selection and stratification for future treatment trials targeting tau.”

The cohort study comprised 21 subjects (median age, 49 years) who had experienced a single moderate to severe TBI a median of 32 years (range, 18-51 years) before enrollment. A control group comprised 11 noninjured adults who were matched for age and other demographic factors. Everyone underwent a PET scan with flortaucipir, brain MRI, CSF sampling, apolipoprotein E genotyping, and neuropsychological testing.

TBI subjects were grouped according to recovery status: good and disabled. Overall, they showed impairments on multiple cognitive domains (processing speed, executive function, motivation, inhibition, and verbal and visual memory), compared with controls. These findings were largely driven by the disabled group.

Eight TBI subjects had elevated tau binding greater than 2,000 voxels above the threshold of detection (equivalent to 16 cm3 of brain volume), and seven had an increase of 249-1,999 voxels above threshold. Tau binding in the remainder was similar to that in controls. Recovery status didn’t correlate with the tau-binding strength.

Overall, the tau-binding signal appeared most strongly in the right lateral occipital cortex, regardless of functional recovery status.

In TBI subjects, CSF total tau correlated significantly with flortaucipir uptake in cortical gray matter, but not white matter. CSF phosphorylated tau correlated with uptake in white matter, but not gray matter.

The investigators also examined fractional anisotropy, a measure of fiber density, axonal diameter, and myelination in white matter. In TBI subjects, there was more flortaucipir uptake in areas of decreased fractional anisotropy, including association, commissural, and projection tracts.

“Correlations were observed in the genu and body of the corpus callosum, as well as in several association tracts within the ipsilateral (right) hemisphere, including the cingulum bundle, inferior longitudinal fasciculus, uncinate fasciculus, and anterior thalamic radiation, but not in the contralateral hemisphere. Higher cortical flortaucipir [signal] was associated with reduced tissue density in remote white matter regions including the corpus callosum and right prefrontal white matter. The same analysis for gray matter density did not show an association.”

The increased tau signal in TBI subjects “is in keeping with a causative role for traumatic axonal injury in the pathophysiology of posttraumatic tau pathology,” the authors said. “Mechanical forces exerted at the time of head injury are thought to disrupt axonal organization, producing damage to microtubule structure and associated axonal tau. This damage may lead to hyperphosphorylation of tau, misfolding, and neurofibrillary tangle formation, which eventually causes neurodegeneration. Mechanical forces are maximal in points of geometric inflection such as the base of cortical sulci, where tau pathology is seen in chronic traumatic encephalopathy.”

These patterns suggest that tau imaging could provide valuable diagnostic information about the type of posttraumatic neurodegeneration, they said.

The work was supported by the Medical Research Council and UK Dementia Research Institute. None of the authors declared having any competing interests related to the current study. Some authors reported financial ties to pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Gorgoraptis N et al. Sci Transl Med. 2019;11:eaaw1993. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaw1993.

Brain deposits of hyperphosphorylated tau are detectable in traumatic brain injury (TBI) patients 18-51 years after a single moderate to severe incident occurred, researchers reported Sept. 4 in Science Translational Medicine.

Imaging with the tau-specific PET radioligand flortaucipir showed that the protein was most apparent in the right occipital cortex, and was associated with changes in cognitive scores, tau and beta amyloid in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and white matter density, Nikos Gorgoraptis, PhD, of Imperial College London and his colleagues wrote.

“The ability to detect tau pathology in vivo after TBI has major potential implications for diagnosis and prognostication of clinical outcomes after TBI,” the researchers explained. “It is also likely to assist in patient selection and stratification for future treatment trials targeting tau.”

The cohort study comprised 21 subjects (median age, 49 years) who had experienced a single moderate to severe TBI a median of 32 years (range, 18-51 years) before enrollment. A control group comprised 11 noninjured adults who were matched for age and other demographic factors. Everyone underwent a PET scan with flortaucipir, brain MRI, CSF sampling, apolipoprotein E genotyping, and neuropsychological testing.