User login

For MD-IQ on Family Practice News, but a regular topic for Rheumatology News

Knee OA structural defects predict pain trajectories

The presence of bone marrow lesions and cartilage defects on baseline MRI scans of knee osteoarthritis (OA) patients may help to predict moderate to severe pain trajectories, based on data from a population-based study presented here at the European Congress of Rheumatology.

Three pain trajectories were identified: 52% of the patients reported stable mild pain over time, 33% reported moderate pain over time, and 15% reported fluctuating or severe pain over time.

“Knee pain is the most prominent symptom of knee osteoarthritis,” Dr. Pan said in an interview. “It is also a main reason for people to seek joint replacement. Despite this, the causes of knee pain are poorly understood. Therapy will only improve if we understand this better.”

Dr. Pan and his colleagues studied 1,099 adults with knee OA who participated in a population-based study. The mean age was 63 years (ranging from 51 to 81 years). A total of 875 participants were assessed using the knee pain components of the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) at 2.6 years’ follow-up, 768 at 5.1 years’ follow-up, and 563 at 10.7 years’ follow-up.

Knee OA was assessed at baseline by x-ray, and T1-weighted or T2-weighted MRI scans of the right knee were used to assess knee structural pathology. The researchers applied group-based trajectory modeling to identify pain trajectories.

“We identified three distinct trajectories over time,” Dr. Pan said. “Remarkably, structural, environmental, sociodemographic, and psychological factors are associated with a more ‘severe pain’ trajectory, suggesting that pain course is determined by an integrated mix of all these factors.”

Dr. Pan added: “We already know that structural damage is a major driver in the development and maintenance of pain severity, but less is known about the other factors.”

The researchers found a significant dose-response relationship between the number of knee structural abnormalities, including cartilage defects and bone marrow lesions, and the ‘moderate pain’ and ‘severe pain’ trajectories (P less than .001 comparing both categories to the ‘mild pain’ trajectory).

Other factors that were significantly associated with both moderate and severe pain, compared with mild pain, included higher body mass index (overweight but not obese), emotional problems, and musculoskeletal diseases.

The findings provide support to the concept that “pain experience is both complex and individual in nature, suggesting the clinician should target treatments according to which of these factors predominate in the individual,” Dr. Pan said.

Future research may aim to develop “a predictive model that could be utilized in clinical practice and target therapies based on these trajectories.”

Dr. Pan had no financial conflicts to disclose.

The presence of bone marrow lesions and cartilage defects on baseline MRI scans of knee osteoarthritis (OA) patients may help to predict moderate to severe pain trajectories, based on data from a population-based study presented here at the European Congress of Rheumatology.

Three pain trajectories were identified: 52% of the patients reported stable mild pain over time, 33% reported moderate pain over time, and 15% reported fluctuating or severe pain over time.

“Knee pain is the most prominent symptom of knee osteoarthritis,” Dr. Pan said in an interview. “It is also a main reason for people to seek joint replacement. Despite this, the causes of knee pain are poorly understood. Therapy will only improve if we understand this better.”

Dr. Pan and his colleagues studied 1,099 adults with knee OA who participated in a population-based study. The mean age was 63 years (ranging from 51 to 81 years). A total of 875 participants were assessed using the knee pain components of the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) at 2.6 years’ follow-up, 768 at 5.1 years’ follow-up, and 563 at 10.7 years’ follow-up.

Knee OA was assessed at baseline by x-ray, and T1-weighted or T2-weighted MRI scans of the right knee were used to assess knee structural pathology. The researchers applied group-based trajectory modeling to identify pain trajectories.

“We identified three distinct trajectories over time,” Dr. Pan said. “Remarkably, structural, environmental, sociodemographic, and psychological factors are associated with a more ‘severe pain’ trajectory, suggesting that pain course is determined by an integrated mix of all these factors.”

Dr. Pan added: “We already know that structural damage is a major driver in the development and maintenance of pain severity, but less is known about the other factors.”

The researchers found a significant dose-response relationship between the number of knee structural abnormalities, including cartilage defects and bone marrow lesions, and the ‘moderate pain’ and ‘severe pain’ trajectories (P less than .001 comparing both categories to the ‘mild pain’ trajectory).

Other factors that were significantly associated with both moderate and severe pain, compared with mild pain, included higher body mass index (overweight but not obese), emotional problems, and musculoskeletal diseases.

The findings provide support to the concept that “pain experience is both complex and individual in nature, suggesting the clinician should target treatments according to which of these factors predominate in the individual,” Dr. Pan said.

Future research may aim to develop “a predictive model that could be utilized in clinical practice and target therapies based on these trajectories.”

Dr. Pan had no financial conflicts to disclose.

The presence of bone marrow lesions and cartilage defects on baseline MRI scans of knee osteoarthritis (OA) patients may help to predict moderate to severe pain trajectories, based on data from a population-based study presented here at the European Congress of Rheumatology.

Three pain trajectories were identified: 52% of the patients reported stable mild pain over time, 33% reported moderate pain over time, and 15% reported fluctuating or severe pain over time.

“Knee pain is the most prominent symptom of knee osteoarthritis,” Dr. Pan said in an interview. “It is also a main reason for people to seek joint replacement. Despite this, the causes of knee pain are poorly understood. Therapy will only improve if we understand this better.”

Dr. Pan and his colleagues studied 1,099 adults with knee OA who participated in a population-based study. The mean age was 63 years (ranging from 51 to 81 years). A total of 875 participants were assessed using the knee pain components of the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) at 2.6 years’ follow-up, 768 at 5.1 years’ follow-up, and 563 at 10.7 years’ follow-up.

Knee OA was assessed at baseline by x-ray, and T1-weighted or T2-weighted MRI scans of the right knee were used to assess knee structural pathology. The researchers applied group-based trajectory modeling to identify pain trajectories.

“We identified three distinct trajectories over time,” Dr. Pan said. “Remarkably, structural, environmental, sociodemographic, and psychological factors are associated with a more ‘severe pain’ trajectory, suggesting that pain course is determined by an integrated mix of all these factors.”

Dr. Pan added: “We already know that structural damage is a major driver in the development and maintenance of pain severity, but less is known about the other factors.”

The researchers found a significant dose-response relationship between the number of knee structural abnormalities, including cartilage defects and bone marrow lesions, and the ‘moderate pain’ and ‘severe pain’ trajectories (P less than .001 comparing both categories to the ‘mild pain’ trajectory).

Other factors that were significantly associated with both moderate and severe pain, compared with mild pain, included higher body mass index (overweight but not obese), emotional problems, and musculoskeletal diseases.

The findings provide support to the concept that “pain experience is both complex and individual in nature, suggesting the clinician should target treatments according to which of these factors predominate in the individual,” Dr. Pan said.

Future research may aim to develop “a predictive model that could be utilized in clinical practice and target therapies based on these trajectories.”

Dr. Pan had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM THE EULAR 2017 CONGRESS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Three pain trajectories were identified: stable mild pain (52% of patients), moderate pain (33%), and fluctuating or severe pain (15%).

Data source: Population-based cohort study of 1,099 patients with knee OA.

Disclosures: The presenter had no financial conflicts to disclose.

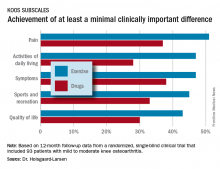

Exercise tops NSAIDs for knee osteoarthritis

LAS VEGAS – After participating in an 8-week neuromuscular exercise therapy program, patients with mild to moderate knee osteoarthritis showed significantly greater symptomatic improvement at 12 months of follow-up than if they had been instructed to treat with analgesics and anti-inflammatory agents in the randomized EXERPHARMA trial.

“Neuromuscular exercise could be the superior choice for long-term relief of symptoms such as swelling, stiffness, and catching, while avoiding the potential side effects of analgesics and anti-inflammatory drugs,” Anders Holsgaard-Larsen, MD, said in his presentation of the 1-year study results at the World Congress on Osteoarthritis.

Ninety-three patients with mild to moderate medial knee osteoarthritis – “a group we commonly see in primary care,” he noted – were randomized to the structured 8-week neuromuscular exercise therapy program or to 8 weeks of instruction in the appropriate use of NSAIDs and acetaminophen. The exercise program entailed two hour-long, physical therapist-supervised sessions per week, which included functional, proprioceptive, strength, and endurance exercises of three or four progressive degrees of difficulty.

The initial results obtained at the conclusion of the 8-week interventions – change in knee joint load while walking – have been published (Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2017 Apr;25[4]:470-80). There was no significant difference between the two study groups. But outcomes at the prespecified 12-month follow-up designed to capture any late improvement were a different story, Dr. Holsgaard-Larsen said at the congress sponsored by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International.

The neuromuscular exercise therapy group showed a significantly greater improvement on the Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Scores (KOOS) symptom subscale at 12 months: a mean 10.9-point improvement from baseline, compared with a 3.3-point improvement with drug therapy.

That being said, the prespecified primary endpoint at 12 months was change on the activities of daily living subscale – and this between-group difference didn’t reach statistical significance. So technically EXERPHARMA was a negative study, according to the investigator.

That comment caused audience member Theodore P. Pincus, MD, to rise in protest.

“I might argue that perhaps we’ve gotten too focused on P-values rather than looking at the whole picture. In my opinion, your hypothesis is more validated than you seem to think,” said Dr. Pincus, professor of rheumatology at Rush University in Chicago.

The EXERPHARMA trial was funded by the Danish Rheumatism Association and other noncommercial research support. Dr. Holsgaard-Larsen reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

LAS VEGAS – After participating in an 8-week neuromuscular exercise therapy program, patients with mild to moderate knee osteoarthritis showed significantly greater symptomatic improvement at 12 months of follow-up than if they had been instructed to treat with analgesics and anti-inflammatory agents in the randomized EXERPHARMA trial.

“Neuromuscular exercise could be the superior choice for long-term relief of symptoms such as swelling, stiffness, and catching, while avoiding the potential side effects of analgesics and anti-inflammatory drugs,” Anders Holsgaard-Larsen, MD, said in his presentation of the 1-year study results at the World Congress on Osteoarthritis.

Ninety-three patients with mild to moderate medial knee osteoarthritis – “a group we commonly see in primary care,” he noted – were randomized to the structured 8-week neuromuscular exercise therapy program or to 8 weeks of instruction in the appropriate use of NSAIDs and acetaminophen. The exercise program entailed two hour-long, physical therapist-supervised sessions per week, which included functional, proprioceptive, strength, and endurance exercises of three or four progressive degrees of difficulty.

The initial results obtained at the conclusion of the 8-week interventions – change in knee joint load while walking – have been published (Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2017 Apr;25[4]:470-80). There was no significant difference between the two study groups. But outcomes at the prespecified 12-month follow-up designed to capture any late improvement were a different story, Dr. Holsgaard-Larsen said at the congress sponsored by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International.

The neuromuscular exercise therapy group showed a significantly greater improvement on the Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Scores (KOOS) symptom subscale at 12 months: a mean 10.9-point improvement from baseline, compared with a 3.3-point improvement with drug therapy.

That being said, the prespecified primary endpoint at 12 months was change on the activities of daily living subscale – and this between-group difference didn’t reach statistical significance. So technically EXERPHARMA was a negative study, according to the investigator.

That comment caused audience member Theodore P. Pincus, MD, to rise in protest.

“I might argue that perhaps we’ve gotten too focused on P-values rather than looking at the whole picture. In my opinion, your hypothesis is more validated than you seem to think,” said Dr. Pincus, professor of rheumatology at Rush University in Chicago.

The EXERPHARMA trial was funded by the Danish Rheumatism Association and other noncommercial research support. Dr. Holsgaard-Larsen reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

LAS VEGAS – After participating in an 8-week neuromuscular exercise therapy program, patients with mild to moderate knee osteoarthritis showed significantly greater symptomatic improvement at 12 months of follow-up than if they had been instructed to treat with analgesics and anti-inflammatory agents in the randomized EXERPHARMA trial.

“Neuromuscular exercise could be the superior choice for long-term relief of symptoms such as swelling, stiffness, and catching, while avoiding the potential side effects of analgesics and anti-inflammatory drugs,” Anders Holsgaard-Larsen, MD, said in his presentation of the 1-year study results at the World Congress on Osteoarthritis.

Ninety-three patients with mild to moderate medial knee osteoarthritis – “a group we commonly see in primary care,” he noted – were randomized to the structured 8-week neuromuscular exercise therapy program or to 8 weeks of instruction in the appropriate use of NSAIDs and acetaminophen. The exercise program entailed two hour-long, physical therapist-supervised sessions per week, which included functional, proprioceptive, strength, and endurance exercises of three or four progressive degrees of difficulty.

The initial results obtained at the conclusion of the 8-week interventions – change in knee joint load while walking – have been published (Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2017 Apr;25[4]:470-80). There was no significant difference between the two study groups. But outcomes at the prespecified 12-month follow-up designed to capture any late improvement were a different story, Dr. Holsgaard-Larsen said at the congress sponsored by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International.

The neuromuscular exercise therapy group showed a significantly greater improvement on the Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Scores (KOOS) symptom subscale at 12 months: a mean 10.9-point improvement from baseline, compared with a 3.3-point improvement with drug therapy.

That being said, the prespecified primary endpoint at 12 months was change on the activities of daily living subscale – and this between-group difference didn’t reach statistical significance. So technically EXERPHARMA was a negative study, according to the investigator.

That comment caused audience member Theodore P. Pincus, MD, to rise in protest.

“I might argue that perhaps we’ve gotten too focused on P-values rather than looking at the whole picture. In my opinion, your hypothesis is more validated than you seem to think,” said Dr. Pincus, professor of rheumatology at Rush University in Chicago.

The EXERPHARMA trial was funded by the Danish Rheumatism Association and other noncommercial research support. Dr. Holsgaard-Larsen reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

AT OARSI 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: At 12 months of follow-up, patients with knee osteoarthritis who had been assigned to an 8-week structured neuromuscular exercise therapy program had a mean 10.9-point improvement on the KOOS symptom subscale, significantly better than the 3.3-point improvement in patients assigned to primary therapy with NSAIDs and acetaminophen.

Data source: This randomized, single-blind clinical trial included 93 patients with mild to moderate knee osteoarthritis.

Disclosures: The EXERPHARMA trial was funded by the Danish Rheumatism Association and other noncommercial research support. The presenter reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

EULAR program features novel treatments and targets in immune pathways and key overviews of the field

Novel treatments involving the interleukin-17, IL-23, and Janus kinase (JAK) pathways and the growing importance of early diagnosis and treatment will be some of the key themes covered in the scientific program at this year’s EULAR congress in Madrid, June 14-17.

The annual EULAR congress’ traditional spirit of giving congress attendees a thorough scientific update of the evidence published in peer-reviewed journals across the broad spectrum of rheumatic diseases is reflected in the wide range of state-of-the-art lectures, clinical and basic science symposia, practical workshops, and special interest sessions running throughout the packed 4-day congress, said João Eurico Cabral da Fonseca, MD, PhD, chair of the Scientific Programme Committee.

“Our program is driven by novelty and not by a particular area we need to cover,” said Dr. Fonseca of the rheumatology and metabolic bone disease department at the Santa Maria Hospital in Lisbon.

“There has been a lot of research in the past year on the IL-17 and IL-23 pathway, on the use of IL-6 inhibitors in vasculitis, and exploring the several diseases in rheumatology where the inhibition of the JAK pathway and other intracellular pathways will be relevant,” he said.

Some of these advances and innovation in rheumatology will be highlighted in the many “What is New” (WIN) and “How to Treat” (HOT) sessions scattered throughout the scientific program. WIN sessions are a review of the evidence that has been published during the year on a specific area of rheumatology, whereas the purpose of the HOT sessions is to update attendees on the new research in that space while also allowing experts to impart some of their hands-on experience in the area.

“For the HOT and WIN sessions, we invite people to present who are not only scientifically active but are clinically active in order to give some input, particularly for the HOT sessions. They are also usually well skilled in speaking to and engaging with large audiences.”

In WIN and HOT sessions to be held on the afternoon of Saturday, June 17, Josef Smolen, MD, of the Medical University of Vienna will update attendees on the latest developments in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis.

Dr. Smolen’s talk will be followed by a presentation from pediatric rheumatologist Nico Wulffraat, MD, PhD, of the Wilhelmina Children’s Hospital, Utrecht, the Netherlands on the latest developments in juvenile idiopathic arthritis.

Another WIN session that has been popular with attendees in previous years is EULAR’s collaborative session with The Lancet. The purpose of the collaborative session with The Lancet is twofold: to give attendees an excellent state-of-the-art session on the latest developments in rheumatoid arthritis and also to showcase to the wider global medical community the latest developments in the field of rheumatology, Dr. Fonseca said.

“The long-term goal is to distribute the information we’re gathering in rheumatology journals and at the congress to a broader audience,” he said, noting the relevance of bringing the innovations in rheumatology to audiences outside the field.

The Lancet session this year is on Saturday morning and will focus on the pathogenesis and treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. High-profile speakers at this session include Iain McInnes, PhD, professor of experimental medicine and rheumatology at the University of Glasgow, who will be presenting a WIN session entitled “Dissecting the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis – what have therapeutics taught us?” and EULAR President Gerd Burmester, MD, director of the department of rheumatology and clinical immunology and professor of medicine at Charité University Hospital and Free University and Humboldt University of Berlin, who will present the WIN session “Don’t delay – new treatment concepts in rheumatoid arthritis.”

The importance of diagnosing and treating patients early is a message that is close to EULAR’s heart, Dr. Fonseca said.

The organization, which celebrates its 70th birthday this year, will launch its first awareness campaign‚ “Don’t delay, connect today!” at the congress. The message of the campaign is that “early diagnosis and access to treatment are the key to preventing further damage and burden on individuals and society.”

He said that while the sessions cover all the major rheumatology disciplines, there are some particularly interesting sessions on psoriatic arthritis and spondyloarthritis.

“There’s a lot more interest in these areas than compared to 5 years ago,” he said in an interview. On the morning of Thursday, June 15, there will be an abstract session titled “PsA: A fascinating disease,” followed by a session the next morning called “PsA: The options grow!”

Attendees can also join a poster tour on Thursday morning to discover exactly what progress has been made in the management of spondyloarthritis.

There are new developments in systemic diseases such as lupus and scleroderma that will be highlighted at this year’s congress. However, osteoarthritis is still waiting for its time in the sun, Dr. Landewé said.

“I would say keep an eye on OA over the next few years. ... There are not many sessions this year, but I am very certain there are many new developments on the horizon, perhaps not at this congress, but in the next couple of years,” he said.

Perhaps the pièce de résistance of the scientific program is the conference highlights session on the last day of the congress. Attendees will need to arrive early to get a seat as this session represents a huge effort by two experts who are selected by the Scientific Programme Committee to summarize the most important research published since EULAR 2016 from a clinical, translational, and basic science perspective.

This year, Loreto Carmona, MD, PhD, an epidemiologist and rheumatologist from the Musculoskeletal Health Institute in Madrid, will take the podium to present the clinical highlights. She will be followed by Thomas Dörner, MD, of the Charité University Hospital, Berlin, who will present the translational and basic science highlights.

“This session is a very useful one for delegates as it simplifies the major bits of the congress,” Dr. Fonseca said.

Novel treatments involving the interleukin-17, IL-23, and Janus kinase (JAK) pathways and the growing importance of early diagnosis and treatment will be some of the key themes covered in the scientific program at this year’s EULAR congress in Madrid, June 14-17.

The annual EULAR congress’ traditional spirit of giving congress attendees a thorough scientific update of the evidence published in peer-reviewed journals across the broad spectrum of rheumatic diseases is reflected in the wide range of state-of-the-art lectures, clinical and basic science symposia, practical workshops, and special interest sessions running throughout the packed 4-day congress, said João Eurico Cabral da Fonseca, MD, PhD, chair of the Scientific Programme Committee.

“Our program is driven by novelty and not by a particular area we need to cover,” said Dr. Fonseca of the rheumatology and metabolic bone disease department at the Santa Maria Hospital in Lisbon.

“There has been a lot of research in the past year on the IL-17 and IL-23 pathway, on the use of IL-6 inhibitors in vasculitis, and exploring the several diseases in rheumatology where the inhibition of the JAK pathway and other intracellular pathways will be relevant,” he said.

Some of these advances and innovation in rheumatology will be highlighted in the many “What is New” (WIN) and “How to Treat” (HOT) sessions scattered throughout the scientific program. WIN sessions are a review of the evidence that has been published during the year on a specific area of rheumatology, whereas the purpose of the HOT sessions is to update attendees on the new research in that space while also allowing experts to impart some of their hands-on experience in the area.

“For the HOT and WIN sessions, we invite people to present who are not only scientifically active but are clinically active in order to give some input, particularly for the HOT sessions. They are also usually well skilled in speaking to and engaging with large audiences.”

In WIN and HOT sessions to be held on the afternoon of Saturday, June 17, Josef Smolen, MD, of the Medical University of Vienna will update attendees on the latest developments in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis.

Dr. Smolen’s talk will be followed by a presentation from pediatric rheumatologist Nico Wulffraat, MD, PhD, of the Wilhelmina Children’s Hospital, Utrecht, the Netherlands on the latest developments in juvenile idiopathic arthritis.

Another WIN session that has been popular with attendees in previous years is EULAR’s collaborative session with The Lancet. The purpose of the collaborative session with The Lancet is twofold: to give attendees an excellent state-of-the-art session on the latest developments in rheumatoid arthritis and also to showcase to the wider global medical community the latest developments in the field of rheumatology, Dr. Fonseca said.

“The long-term goal is to distribute the information we’re gathering in rheumatology journals and at the congress to a broader audience,” he said, noting the relevance of bringing the innovations in rheumatology to audiences outside the field.

The Lancet session this year is on Saturday morning and will focus on the pathogenesis and treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. High-profile speakers at this session include Iain McInnes, PhD, professor of experimental medicine and rheumatology at the University of Glasgow, who will be presenting a WIN session entitled “Dissecting the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis – what have therapeutics taught us?” and EULAR President Gerd Burmester, MD, director of the department of rheumatology and clinical immunology and professor of medicine at Charité University Hospital and Free University and Humboldt University of Berlin, who will present the WIN session “Don’t delay – new treatment concepts in rheumatoid arthritis.”

The importance of diagnosing and treating patients early is a message that is close to EULAR’s heart, Dr. Fonseca said.

The organization, which celebrates its 70th birthday this year, will launch its first awareness campaign‚ “Don’t delay, connect today!” at the congress. The message of the campaign is that “early diagnosis and access to treatment are the key to preventing further damage and burden on individuals and society.”

He said that while the sessions cover all the major rheumatology disciplines, there are some particularly interesting sessions on psoriatic arthritis and spondyloarthritis.

“There’s a lot more interest in these areas than compared to 5 years ago,” he said in an interview. On the morning of Thursday, June 15, there will be an abstract session titled “PsA: A fascinating disease,” followed by a session the next morning called “PsA: The options grow!”

Attendees can also join a poster tour on Thursday morning to discover exactly what progress has been made in the management of spondyloarthritis.

There are new developments in systemic diseases such as lupus and scleroderma that will be highlighted at this year’s congress. However, osteoarthritis is still waiting for its time in the sun, Dr. Landewé said.

“I would say keep an eye on OA over the next few years. ... There are not many sessions this year, but I am very certain there are many new developments on the horizon, perhaps not at this congress, but in the next couple of years,” he said.

Perhaps the pièce de résistance of the scientific program is the conference highlights session on the last day of the congress. Attendees will need to arrive early to get a seat as this session represents a huge effort by two experts who are selected by the Scientific Programme Committee to summarize the most important research published since EULAR 2016 from a clinical, translational, and basic science perspective.

This year, Loreto Carmona, MD, PhD, an epidemiologist and rheumatologist from the Musculoskeletal Health Institute in Madrid, will take the podium to present the clinical highlights. She will be followed by Thomas Dörner, MD, of the Charité University Hospital, Berlin, who will present the translational and basic science highlights.

“This session is a very useful one for delegates as it simplifies the major bits of the congress,” Dr. Fonseca said.

Novel treatments involving the interleukin-17, IL-23, and Janus kinase (JAK) pathways and the growing importance of early diagnosis and treatment will be some of the key themes covered in the scientific program at this year’s EULAR congress in Madrid, June 14-17.

The annual EULAR congress’ traditional spirit of giving congress attendees a thorough scientific update of the evidence published in peer-reviewed journals across the broad spectrum of rheumatic diseases is reflected in the wide range of state-of-the-art lectures, clinical and basic science symposia, practical workshops, and special interest sessions running throughout the packed 4-day congress, said João Eurico Cabral da Fonseca, MD, PhD, chair of the Scientific Programme Committee.

“Our program is driven by novelty and not by a particular area we need to cover,” said Dr. Fonseca of the rheumatology and metabolic bone disease department at the Santa Maria Hospital in Lisbon.

“There has been a lot of research in the past year on the IL-17 and IL-23 pathway, on the use of IL-6 inhibitors in vasculitis, and exploring the several diseases in rheumatology where the inhibition of the JAK pathway and other intracellular pathways will be relevant,” he said.

Some of these advances and innovation in rheumatology will be highlighted in the many “What is New” (WIN) and “How to Treat” (HOT) sessions scattered throughout the scientific program. WIN sessions are a review of the evidence that has been published during the year on a specific area of rheumatology, whereas the purpose of the HOT sessions is to update attendees on the new research in that space while also allowing experts to impart some of their hands-on experience in the area.

“For the HOT and WIN sessions, we invite people to present who are not only scientifically active but are clinically active in order to give some input, particularly for the HOT sessions. They are also usually well skilled in speaking to and engaging with large audiences.”

In WIN and HOT sessions to be held on the afternoon of Saturday, June 17, Josef Smolen, MD, of the Medical University of Vienna will update attendees on the latest developments in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis.

Dr. Smolen’s talk will be followed by a presentation from pediatric rheumatologist Nico Wulffraat, MD, PhD, of the Wilhelmina Children’s Hospital, Utrecht, the Netherlands on the latest developments in juvenile idiopathic arthritis.

Another WIN session that has been popular with attendees in previous years is EULAR’s collaborative session with The Lancet. The purpose of the collaborative session with The Lancet is twofold: to give attendees an excellent state-of-the-art session on the latest developments in rheumatoid arthritis and also to showcase to the wider global medical community the latest developments in the field of rheumatology, Dr. Fonseca said.

“The long-term goal is to distribute the information we’re gathering in rheumatology journals and at the congress to a broader audience,” he said, noting the relevance of bringing the innovations in rheumatology to audiences outside the field.

The Lancet session this year is on Saturday morning and will focus on the pathogenesis and treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. High-profile speakers at this session include Iain McInnes, PhD, professor of experimental medicine and rheumatology at the University of Glasgow, who will be presenting a WIN session entitled “Dissecting the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis – what have therapeutics taught us?” and EULAR President Gerd Burmester, MD, director of the department of rheumatology and clinical immunology and professor of medicine at Charité University Hospital and Free University and Humboldt University of Berlin, who will present the WIN session “Don’t delay – new treatment concepts in rheumatoid arthritis.”

The importance of diagnosing and treating patients early is a message that is close to EULAR’s heart, Dr. Fonseca said.

The organization, which celebrates its 70th birthday this year, will launch its first awareness campaign‚ “Don’t delay, connect today!” at the congress. The message of the campaign is that “early diagnosis and access to treatment are the key to preventing further damage and burden on individuals and society.”

He said that while the sessions cover all the major rheumatology disciplines, there are some particularly interesting sessions on psoriatic arthritis and spondyloarthritis.

“There’s a lot more interest in these areas than compared to 5 years ago,” he said in an interview. On the morning of Thursday, June 15, there will be an abstract session titled “PsA: A fascinating disease,” followed by a session the next morning called “PsA: The options grow!”

Attendees can also join a poster tour on Thursday morning to discover exactly what progress has been made in the management of spondyloarthritis.

There are new developments in systemic diseases such as lupus and scleroderma that will be highlighted at this year’s congress. However, osteoarthritis is still waiting for its time in the sun, Dr. Landewé said.

“I would say keep an eye on OA over the next few years. ... There are not many sessions this year, but I am very certain there are many new developments on the horizon, perhaps not at this congress, but in the next couple of years,” he said.

Perhaps the pièce de résistance of the scientific program is the conference highlights session on the last day of the congress. Attendees will need to arrive early to get a seat as this session represents a huge effort by two experts who are selected by the Scientific Programme Committee to summarize the most important research published since EULAR 2016 from a clinical, translational, and basic science perspective.

This year, Loreto Carmona, MD, PhD, an epidemiologist and rheumatologist from the Musculoskeletal Health Institute in Madrid, will take the podium to present the clinical highlights. She will be followed by Thomas Dörner, MD, of the Charité University Hospital, Berlin, who will present the translational and basic science highlights.

“This session is a very useful one for delegates as it simplifies the major bits of the congress,” Dr. Fonseca said.

EMEUNET tailors EULAR experience for young rheumatologists

Young rheumatologists and researchers will find plenty of relevant content at this year’s EULAR Congress in Madrid, June 14-17, thanks to a dedicated presentation track. Other tailored opportunities include networking events, mentorship for first-time attendees to help them make the most of their EULAR experience, and a unique opportunity for small group discussion and networking with key opinion leaders in rheumatology in the so-called mentor-mentee meetings.

The Young Rheumatologists track provides three sessions with a special focus on researchers and clinicians who are early in their careers, Sofia Ramiro, MD, PhD, explained in an interview. Dr. Ramiro chairs the steering committee of the Emerging Eular Network (EMEUNET), a network of young clinicians and researchers in the field of rheumatology in Europe.

Another session will zero in on osteoarthritis, vasculitis, spondyloarthritis, and rheumatoid arthritis, with a shorter lecture format and more time left for a question-and-answer session and discussion. With a group of younger rheumatologists in attendance, “the sessions are somewhat more informal,” promoting a comfortable and interactive environment for discussion and learning, Dr. Ramiro said.

The third session in the Young Rheumatologists track will consist of case discussions focused on how to counsel and take care of women who have rheumatoid arthritis and would like to become pregnant. Two patient cases will be presented and discussed by leaders in the field. “Again, the idea is to make these presentations as real-world as possible,” Dr. Ramiro said.

The EMEUNET booth will be in the EULAR Village, and, for the first time, the booth will be incorporated in the EULAR booth, as a “pillar” under the bigger EULAR umbrella. Dr. Ramiro said to be sure to stay tuned for a surprise associated with EULAR’s 70th anniversary. On the evening of Thursday, June 15, EMEUNET will host a networking event.

On the morning of Friday, June 16, mentor-mentee meetings organized by EMEUNET link five to six young attendees with mentors, according to area of interest. Sign up is available online, allowing small group discussion with leaders in academic rheumatology. This year, meetings will be led by Iain McInnes, PhD (Glasgow, Scotland), Josef Smolen, MD (Vienna), and William Dixon, MBBS, PhD (Manchester, England). Mentorship topics can include the incorporation of research into a clinical career, general career advice, and insight into international collaboration, Dr. Ramiro said.

“These are usually very well-attended meetings and very popular,” she said. “People who have participated in them always give us very good feedback and are very enthusiastic about how easily accessible these very famous key opinion leaders are and what good advice they give to them.”

Finally, the Ambassador program helps first-time attendees get the most out of EULAR. “I think that we all know that the first time we attend such a huge conference the experience can be daunting,” Dr. Ramiro said. Now in its third year, the ambassador program pairs an EMEUNET member with up to six first-timers. The ambassador helps the newcomers decide which sessions to attend and remains available through mobile phone, social media, and the meeting app throughout the meeting.

All of EMEUNET’s activities during EULAR support the organization’s aim of “widening collaboration and fostering collaboration among young researchers and clinicians,” Dr. Ramiro said. “The ultimate aim is to improve and promote education in the area of our diseases and to foster research collaborations,” she said of the 1,500-member strong organization.

Young rheumatologists and researchers will find plenty of relevant content at this year’s EULAR Congress in Madrid, June 14-17, thanks to a dedicated presentation track. Other tailored opportunities include networking events, mentorship for first-time attendees to help them make the most of their EULAR experience, and a unique opportunity for small group discussion and networking with key opinion leaders in rheumatology in the so-called mentor-mentee meetings.

The Young Rheumatologists track provides three sessions with a special focus on researchers and clinicians who are early in their careers, Sofia Ramiro, MD, PhD, explained in an interview. Dr. Ramiro chairs the steering committee of the Emerging Eular Network (EMEUNET), a network of young clinicians and researchers in the field of rheumatology in Europe.

Another session will zero in on osteoarthritis, vasculitis, spondyloarthritis, and rheumatoid arthritis, with a shorter lecture format and more time left for a question-and-answer session and discussion. With a group of younger rheumatologists in attendance, “the sessions are somewhat more informal,” promoting a comfortable and interactive environment for discussion and learning, Dr. Ramiro said.

The third session in the Young Rheumatologists track will consist of case discussions focused on how to counsel and take care of women who have rheumatoid arthritis and would like to become pregnant. Two patient cases will be presented and discussed by leaders in the field. “Again, the idea is to make these presentations as real-world as possible,” Dr. Ramiro said.

The EMEUNET booth will be in the EULAR Village, and, for the first time, the booth will be incorporated in the EULAR booth, as a “pillar” under the bigger EULAR umbrella. Dr. Ramiro said to be sure to stay tuned for a surprise associated with EULAR’s 70th anniversary. On the evening of Thursday, June 15, EMEUNET will host a networking event.

On the morning of Friday, June 16, mentor-mentee meetings organized by EMEUNET link five to six young attendees with mentors, according to area of interest. Sign up is available online, allowing small group discussion with leaders in academic rheumatology. This year, meetings will be led by Iain McInnes, PhD (Glasgow, Scotland), Josef Smolen, MD (Vienna), and William Dixon, MBBS, PhD (Manchester, England). Mentorship topics can include the incorporation of research into a clinical career, general career advice, and insight into international collaboration, Dr. Ramiro said.

“These are usually very well-attended meetings and very popular,” she said. “People who have participated in them always give us very good feedback and are very enthusiastic about how easily accessible these very famous key opinion leaders are and what good advice they give to them.”

Finally, the Ambassador program helps first-time attendees get the most out of EULAR. “I think that we all know that the first time we attend such a huge conference the experience can be daunting,” Dr. Ramiro said. Now in its third year, the ambassador program pairs an EMEUNET member with up to six first-timers. The ambassador helps the newcomers decide which sessions to attend and remains available through mobile phone, social media, and the meeting app throughout the meeting.

All of EMEUNET’s activities during EULAR support the organization’s aim of “widening collaboration and fostering collaboration among young researchers and clinicians,” Dr. Ramiro said. “The ultimate aim is to improve and promote education in the area of our diseases and to foster research collaborations,” she said of the 1,500-member strong organization.

Young rheumatologists and researchers will find plenty of relevant content at this year’s EULAR Congress in Madrid, June 14-17, thanks to a dedicated presentation track. Other tailored opportunities include networking events, mentorship for first-time attendees to help them make the most of their EULAR experience, and a unique opportunity for small group discussion and networking with key opinion leaders in rheumatology in the so-called mentor-mentee meetings.

The Young Rheumatologists track provides three sessions with a special focus on researchers and clinicians who are early in their careers, Sofia Ramiro, MD, PhD, explained in an interview. Dr. Ramiro chairs the steering committee of the Emerging Eular Network (EMEUNET), a network of young clinicians and researchers in the field of rheumatology in Europe.

Another session will zero in on osteoarthritis, vasculitis, spondyloarthritis, and rheumatoid arthritis, with a shorter lecture format and more time left for a question-and-answer session and discussion. With a group of younger rheumatologists in attendance, “the sessions are somewhat more informal,” promoting a comfortable and interactive environment for discussion and learning, Dr. Ramiro said.

The third session in the Young Rheumatologists track will consist of case discussions focused on how to counsel and take care of women who have rheumatoid arthritis and would like to become pregnant. Two patient cases will be presented and discussed by leaders in the field. “Again, the idea is to make these presentations as real-world as possible,” Dr. Ramiro said.

The EMEUNET booth will be in the EULAR Village, and, for the first time, the booth will be incorporated in the EULAR booth, as a “pillar” under the bigger EULAR umbrella. Dr. Ramiro said to be sure to stay tuned for a surprise associated with EULAR’s 70th anniversary. On the evening of Thursday, June 15, EMEUNET will host a networking event.

On the morning of Friday, June 16, mentor-mentee meetings organized by EMEUNET link five to six young attendees with mentors, according to area of interest. Sign up is available online, allowing small group discussion with leaders in academic rheumatology. This year, meetings will be led by Iain McInnes, PhD (Glasgow, Scotland), Josef Smolen, MD (Vienna), and William Dixon, MBBS, PhD (Manchester, England). Mentorship topics can include the incorporation of research into a clinical career, general career advice, and insight into international collaboration, Dr. Ramiro said.

“These are usually very well-attended meetings and very popular,” she said. “People who have participated in them always give us very good feedback and are very enthusiastic about how easily accessible these very famous key opinion leaders are and what good advice they give to them.”

Finally, the Ambassador program helps first-time attendees get the most out of EULAR. “I think that we all know that the first time we attend such a huge conference the experience can be daunting,” Dr. Ramiro said. Now in its third year, the ambassador program pairs an EMEUNET member with up to six first-timers. The ambassador helps the newcomers decide which sessions to attend and remains available through mobile phone, social media, and the meeting app throughout the meeting.

All of EMEUNET’s activities during EULAR support the organization’s aim of “widening collaboration and fostering collaboration among young researchers and clinicians,” Dr. Ramiro said. “The ultimate aim is to improve and promote education in the area of our diseases and to foster research collaborations,” she said of the 1,500-member strong organization.

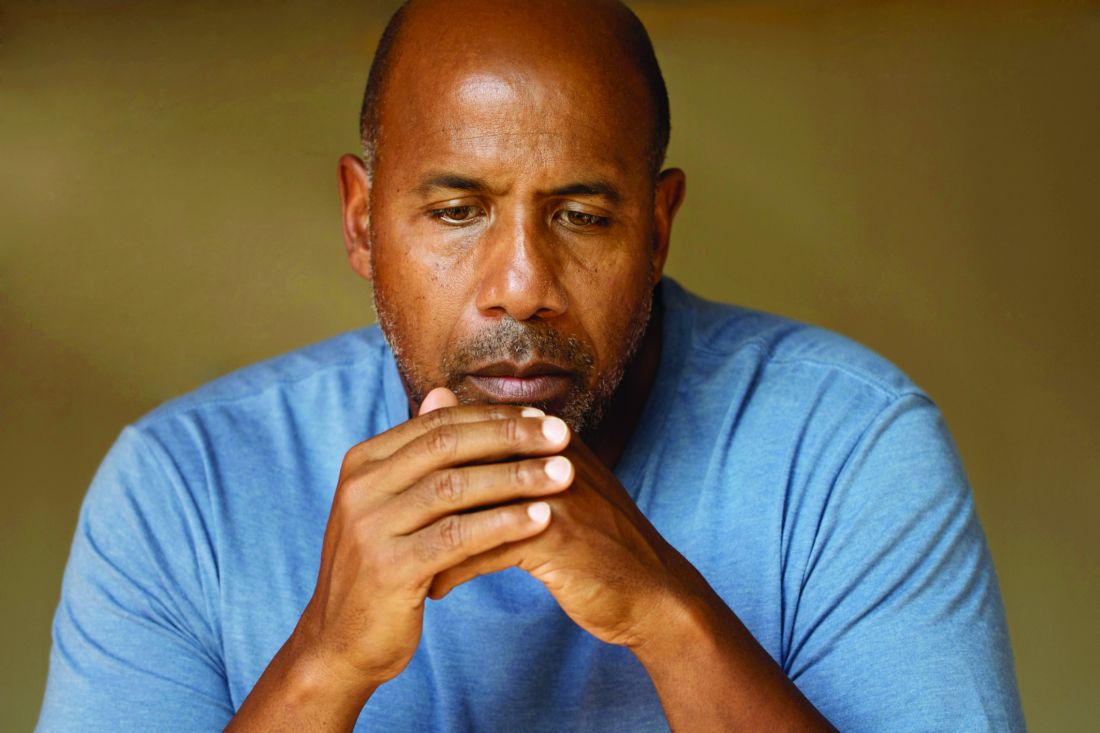

Osteoarthritis contributes more to difficulty walking than do diabetes, CVD

Hip and knee osteoarthritis on their own predict difficulty walking in adults aged 55 years and older to a greater extent than do diabetes or cardiovascular disease individually, according to findings from a Canadian population-based study.

The ability of hip and knee osteoarthritis (OA) to predict difficulty walking also increased with the number of joints affected and acted additively with either diabetes or cardiovascular disease (CVD) or both to raise the odds for walking problems, reported Lauren K. King, MBBS, of the University of Toronto, and colleagues.

To determine the impact of hip and knee OA on difficulty walking, the researchers reviewed data from 18,490 adults recruited between 1996 and 1998. The average age of the participants was 68 years, 60% were women, and 25% reported difficulty with walking during the past 3 months (Arthritis Care Res. 2017 May 17 doi: 10.1002/acr.23250). They completed questionnaires about their health conditions, and the researchers developed a clinical nomogram using their final multivariate logistic model.

The researchers calculated that the predicted probability of difficulty walking for a 60-year-old, middle-income, normal-weight woman with no health conditions was 5%-10%. However, the probability of walking problems was 10%-20% for the same woman with diabetes and CVD; 40% with osteoarthritis in two hips/knees; 60%-70% with diabetes, CVD, and osteoarthritis in two hips/knees; and 80% with diabetes, CVD, and osteoarthritis in all hips/knees.

Overall, 10% of the participants met criteria for hip OA and 15% met criteria for knee OA. The most common chronic conditions were hypertension (43%), diabetes (11%), and CVD (11%).

In a multivariate analysis, individuals with knee or hip OA had the highest odds of reporting walking difficulty, and the odds increased with the number of joints affected.

The results were limited by the cross-sectional nature of the study and the use of self-reports, the researchers noted.

However, “Given the high prevalence of OA and the substantial physical, social, and psychological consequences of walking difficulty, we believe our findings have high clinical relevance to primary care physicians and internal medicine specialists beyond rheumatology,” they said.

“Further research is warranted to understand the mechanisms by which chronic conditions affect mobility, physical activity, and sedentary behavior, and to elucidate safe and effective management approaches to reduce OA-related walking difficulty,” they added.

None of the investigators had relevant financial disclosures to report.

Hip and knee osteoarthritis on their own predict difficulty walking in adults aged 55 years and older to a greater extent than do diabetes or cardiovascular disease individually, according to findings from a Canadian population-based study.

The ability of hip and knee osteoarthritis (OA) to predict difficulty walking also increased with the number of joints affected and acted additively with either diabetes or cardiovascular disease (CVD) or both to raise the odds for walking problems, reported Lauren K. King, MBBS, of the University of Toronto, and colleagues.

To determine the impact of hip and knee OA on difficulty walking, the researchers reviewed data from 18,490 adults recruited between 1996 and 1998. The average age of the participants was 68 years, 60% were women, and 25% reported difficulty with walking during the past 3 months (Arthritis Care Res. 2017 May 17 doi: 10.1002/acr.23250). They completed questionnaires about their health conditions, and the researchers developed a clinical nomogram using their final multivariate logistic model.

The researchers calculated that the predicted probability of difficulty walking for a 60-year-old, middle-income, normal-weight woman with no health conditions was 5%-10%. However, the probability of walking problems was 10%-20% for the same woman with diabetes and CVD; 40% with osteoarthritis in two hips/knees; 60%-70% with diabetes, CVD, and osteoarthritis in two hips/knees; and 80% with diabetes, CVD, and osteoarthritis in all hips/knees.

Overall, 10% of the participants met criteria for hip OA and 15% met criteria for knee OA. The most common chronic conditions were hypertension (43%), diabetes (11%), and CVD (11%).

In a multivariate analysis, individuals with knee or hip OA had the highest odds of reporting walking difficulty, and the odds increased with the number of joints affected.

The results were limited by the cross-sectional nature of the study and the use of self-reports, the researchers noted.

However, “Given the high prevalence of OA and the substantial physical, social, and psychological consequences of walking difficulty, we believe our findings have high clinical relevance to primary care physicians and internal medicine specialists beyond rheumatology,” they said.

“Further research is warranted to understand the mechanisms by which chronic conditions affect mobility, physical activity, and sedentary behavior, and to elucidate safe and effective management approaches to reduce OA-related walking difficulty,” they added.

None of the investigators had relevant financial disclosures to report.

Hip and knee osteoarthritis on their own predict difficulty walking in adults aged 55 years and older to a greater extent than do diabetes or cardiovascular disease individually, according to findings from a Canadian population-based study.

The ability of hip and knee osteoarthritis (OA) to predict difficulty walking also increased with the number of joints affected and acted additively with either diabetes or cardiovascular disease (CVD) or both to raise the odds for walking problems, reported Lauren K. King, MBBS, of the University of Toronto, and colleagues.

To determine the impact of hip and knee OA on difficulty walking, the researchers reviewed data from 18,490 adults recruited between 1996 and 1998. The average age of the participants was 68 years, 60% were women, and 25% reported difficulty with walking during the past 3 months (Arthritis Care Res. 2017 May 17 doi: 10.1002/acr.23250). They completed questionnaires about their health conditions, and the researchers developed a clinical nomogram using their final multivariate logistic model.

The researchers calculated that the predicted probability of difficulty walking for a 60-year-old, middle-income, normal-weight woman with no health conditions was 5%-10%. However, the probability of walking problems was 10%-20% for the same woman with diabetes and CVD; 40% with osteoarthritis in two hips/knees; 60%-70% with diabetes, CVD, and osteoarthritis in two hips/knees; and 80% with diabetes, CVD, and osteoarthritis in all hips/knees.

Overall, 10% of the participants met criteria for hip OA and 15% met criteria for knee OA. The most common chronic conditions were hypertension (43%), diabetes (11%), and CVD (11%).

In a multivariate analysis, individuals with knee or hip OA had the highest odds of reporting walking difficulty, and the odds increased with the number of joints affected.

The results were limited by the cross-sectional nature of the study and the use of self-reports, the researchers noted.

However, “Given the high prevalence of OA and the substantial physical, social, and psychological consequences of walking difficulty, we believe our findings have high clinical relevance to primary care physicians and internal medicine specialists beyond rheumatology,” they said.

“Further research is warranted to understand the mechanisms by which chronic conditions affect mobility, physical activity, and sedentary behavior, and to elucidate safe and effective management approaches to reduce OA-related walking difficulty,” they added.

None of the investigators had relevant financial disclosures to report.

FROM ARTHRITIS CARE & RESEARCH

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The probability of difficulty walking was 40% for a 60-year-old, middle-income, normal-weight woman with OA in two hips or knees vs. 5% in the same woman with no health conditions.

Data source: A population-based cohort study of 18,490 adults aged 55 years and older.

Disclosures: None of the investigators had relevant financial disclosures to report.

Experts bust common sports medicine myths

SAN DIEGO – Is it okay for pregnant women to attend CrossFit classes? Are patients who run for fun at increased risk for osteoarthritis? Does stretching before exercise provide any benefits to athletes?

Experts discussed these topics during a session titled “Mythbusters in sports medicine” at the annual meeting of the American Medical Society for Sports Medicine.

Does exercise negatively impact pregnancy?

The idea that strenuous exercise during pregnancy can harm a baby’s health is a myth, according to Elizabeth A. Joy, MD.

“Women having healthy, uncomplicated pregnancies should be encouraged to be physically active throughout pregnancy, with a goal of achieving 150 minutes per week of moderate-intensity activity,” she said. “Fit pregnant women who were habitually performing high-intensity exercise before pregnancy can continue to do so during pregnancy, assuming an otherwise healthy, uncomplicated pregnancy.”

Results from more than 600 studies in the medical literature indicate that exercise during pregnancy is safe for moms and babies, noted Dr. Joy, medical director for community health and food and nutrition at Intermountain Healthcare in Salt Lake City, Utah.

In fact, the 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans state that pregnant women who habitually engage in vigorous-intensity aerobic activity or who are highly active “can continue physical activity during pregnancy and the postpartum period, provided that they remain healthy and discuss with their health care provider how and when activity should be adjusted over time.”

Such advice wasn’t always supported by the medical profession. In fact, 1985 guidelines from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommended that women limit exercise to no more than 15 minutes at a time during pregnancy and keep their maternal heart rate less than 140 beats per minute. ACOG also discouraged previously sedentary women from beginning an exercise program during pregnancy.

“Sadly, women are still getting this advice,” said Dr. Joy, who is also president of the American College of Sports Medicine. According to the 2005-2010 National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, only 18% of pregnant women reported receiving counseling to be physically active during their pregnancies (Matern Child Health J. 2014 Sep;18[7]:1610-18). “That is just unacceptable,” she said.

In a prospective study of the association between vigorous physical activity during pregnancy and length of gestation and birth weight, researchers evaluated 1,647 births among primiparous women (Matern Child Health J. 2012 Jul;16[5]:1031-44).

They conducted telephone interviews with the women between 7-20 weeks gestation and assigned metabolic equivalent of task values to self-reported levels of physical activity. Of the 1,647 births, 7% were preterm.

Slightly more than one-third of the women (35%) performed first-trimester vigorous physical activity. The average total vigorous activity reported was 76 minutes per week, 38% of which was vigorous recreational activity.

Women who performed first-trimester vigorous recreational physical activity tended to have lower odds of preterm birth. They also tended to have lighter-weight babies, but this did not reach statistical significance (P = .08). The authors concluded that first-trimester vigorous physical activity “does not appear to be detrimental to the timing of birth or birth weight.”

In a separate analysis, researchers evaluated acute fetal responses to individually prescribed exercise according to existing physical activity guidelines in active and inactive pregnant women (Obstet Gynecol. 2012 Mar;119[3]:603-10).

Of the 45 study participants, 15 were classified as nonexercisers, 15 were regularly active, and 15 were highly active. The women underwent treadmill assessment between 28 weeks and 33 weeks, while fetal assessment included umbilical artery Doppler, fetal heart tracing and rate, and biophysical profile at rest and immediately post exercise.

The researchers observed no differences between the groups in mode of delivery, birth weight, and Apgar scores. During vigorous-intensity exercise, all umbilical artery indices showed decreases post exercise.

“Although statistically significant, this decrease is likely not clinically significant,” the researchers wrote. “We did not identify any adverse acute fetal responses to current exercise recommendations.” They went on to conclude that the potential health benefits of exercise “are too great for [physicians] to miss the opportunity to effectively counsel pregnant women about this important heath-enhancing behavior.”

In a more recent randomized study, Swedish researchers evaluated the efficacy of moderate-to-vigorous resistance exercise in 92 pregnant women (Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2015 Jan; 94[1]:35-42).

The intervention group received supervised resistance exercise twice per week at moderate-to-vigorous intensity between 14-25 weeks of their pregnancy, while the control group received a generalized home exercise program. Outcome measures included health-related quality of life, physical strength, pain, weight, blood pressure, functional status, activity level, and perinatal data.

The researchers found no significant differences between the two groups and concluded that “supervised regular, moderate-to-vigorous resistance exercise performed twice per week does not adversely impact childbirth outcome, pain, or blood pressure.”

Despite all that’s known about exercise during pregnancy, a few practice and research gaps remain.

For one, Dr. Joy said, the relationship between performing physically demanding work during pregnancy in combination with moderate-to-vigorous exercise remains largely unknown.

“Even within health care, you have residents, nurses, and others working in hospitals,” she said. “That’s demanding work, but we don’t know whether or not moderate-to-vigorous exercise in combination with that kind of work is safe. Also, although women tend to thermoregulate better during pregnancy, we still don’t fully understand the impact of elevated core body temperature, which may occur with regularly performed vigorous-intensity exercise over the course of pregnancy.”

Does running cause knee OA?

During another talk at the meeting, William O. Roberts, MD, characterized the notion that running causes knee osteoarthritis as largely a myth for recreational runners. However, elite runners and athletes who participate in other sports may face an increased risk of developing the condition.

Well-established risk factors for knee OA include post–joint injury proteases and cytokines and injury load stress on articular cartilage. “Other risk factors include overweight and obesity, a family history of OA, exercise, heavy work that involved squatting and kneeling, and being female,” said Dr. Roberts, professor of family medicine and community health at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis.

He discussed three articles on the topic drawn from medical literature. One was a retrospective cross-sectional analysis of 2,637 Osteoarthritis Initiative participants, 45-79 years of age, who had knee-specific pain or knee x-ray data 4 years into the 10-year–long study (Arthritis Care Res. 2017 Feb;69[2]:183-91).

More than half of the participants (56%) were female, their mean body mass index was 28.5 kg/m2, only 20% reported more than 2,000 bouts of running during their lifetime, and about 5% had run competitively.

Adjusted odds ratios of pain, radiographic OA, and symptomatic OA for those prior runners and current runners, compared with those who never ran, were 0.82 and 0.76 (P for trend = .02), 0.98 and 0.91 (P for trend = .05), and 0.88 and 0.71 (P for trend = .03), respectively.

The authors concluded that running does not appear to be detrimental to the knees, and the strength of recommendation taxonomy was rated as 2B.

In a separate analysis, researchers performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of 11 cohort (6 retrospective) and 4 case-control studies related to running and knee arthritis (Am J Sports Med. 2016 May;45[6]:1447-57). The mean ages of subjects at outcome assessment ranged from 27 years to 69 years, and the sample size ranged from 15 to 1,279 participants. The four case control studies assessed exposure by mailed questionnaire or by personal interview.

The meta-analysis suggests that runners have a 50% reduced odds of requiring a total knee replacement because of OA.

“It contradicts some previous studies, and there were confounders,” Dr. Roberts said of the analysis. “The one that I noticed is that people would delay surgery to keep running. That’s what I find in my practice.”

The researchers were unable to link running to knee OA development. Moderate- to low-quality evidence suggests a positive association with OA diagnosis but a negative association with requirement for a total knee replacement.

Based on published evidence, they concluded there is no clear advice to give regarding the potential effect of running on musculoskeletal health and rated the strength of evidence as 1A.

A third study Dr. Roberts discussed investigated the association between specific sports participation and knee OA (J Athl Train. 2015 Jan. 9. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-50.2.08). After locating nearly 18,000 articles on the topic, the researchers limited their meta-analysis to 17 published studies.

They found that the overall risk of knee OA prevalence in sports participants was 7.7%, compared with 7.3% among nonexposed controls (odds ratio, 0.9). However, risks for knee OA were elevated among those who participated in the following sports: soccer (OR, 3.5), elite long-distance running (OR, 3.3), competitive weightlifting (OR, 6.9), and wrestling (OR, 3.8). The researchers concluded that athletes who participate in those sports “should be targeted for risk-reduction strategies.”

“So, does running cause knee OA? It depends,” said Dr. Roberts, who is also medical director of Twin Cities in Motion. “There is a potential risk to high-volume, high-intensity, and long-distance runners, but there does not appear to be a risk in fitness or recreational runners. Of course, you can’t erase your genetics.”

He called for more research on the topic, including prospective longitudinal outcomes studies, those that study the role of genetics/epigenetics in runners and nonrunners who develop knee OA and those focused on the knee joint “chemical environment,” referring to recent work that suggests that running appears to decrease knee intra-articular proinflammatory cytokine concentration (Eur J Appl Physiol. 2016 Dec;116[11-12]:2305-14).

“It’s okay to run for fitness, because the health benefits far outweigh the risk of knee OA,” Dr. Roberts said. “If you run hard and long, it could be a problem. We probably should be screening for neuromuscular control to reduce anterior cruciate ligament disruption.”

Does it help to stretch before exercise?

Stretching before engaging in exercise is a common practice often recommended by coaches and clinicians – but it appears to have no role in preventing injuries during exercise itself.

Several decades ago, investigators subscribed to muscle spasm theory, which held that unaccustomed exercise caused muscle spasms.

“The thought was that muscle spasms impeded blood flow to the muscle, causing ischemic pain and further spasm,” Valerie E. Cothran, MD, said during a presentation at the meeting. “Stretching the muscle was thought to restore blood flow to the muscle and interrupt the pain-spasm-pain cycle. This theory has been discredited for 40 years, but the practice of stretching before exercise persists.”

According to Dr. Cothran, of the department of family and community medicine at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, a limited number of randomized, controlled trials exist on the topic – and many are fraught with limitations, such as the evaluation of multiple stretching methods and variable types of sports activities and the inclusion of multiple cointerventions.

One systematic review evaluated 361 randomized, controlled trials and cohort studies of interventions that included stretching and that appeared in the medical literature from 1966 to 2002 (Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004 Mar;36[3]:371-8). Studies with no controls were excluded from the analysis, as were those in which stretching could not be assessed independently or those that did not include people engaged in sports or fitness activities.

The researchers determined that stretching was not significantly associated with a reduction in total injuries (OR, 0.93). “There is not sufficient evidence to endorse or discontinue routine stretching before or after exercise to prevent injury among competitive or recreational athletes,” they concluded.

The following year, Lawrence Hart, MBBch, of McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., assessed the same set of data but eliminated some of the confounding factors of the previous analysis, including studies that had limited statistical power (Clin J Sport Med. 2005 Mar;15[2]:113). The final meta-analysis included six studies.

Dr. Hart found that neither stretching of specific leg-muscle groups or multiple muscle groups led to a reduction in total injuries, such as shin splints, tibial stress reaction, or sprains/strains (OR, 0.93). In addition, reduction in injuries was not significantly greater for stretching of specific muscles or multiple muscle groups (OR, 0.80, and OR, 0.96, respectively). “Limited evidence showed stretching had no effects on injuries,” he concluded.

A more recent systematic review analyzed the efficacy of static stretching as part of a warm-up for the prevention of exercise-related injury (Res Sports Med. 2008;16[3]:213-31). The researchers reviewed 364 studies published after 1990 but before 2008, and they included seven in the final analysis: four randomized, controlled trials and three controlled trials.

All four randomized, controlled trials concluded that static stretching was ineffective in reducing the incidence of exercise-related injury, and only one of the three controlled trials concluded that static stretching reduced the incidence of exercise-related injury. In addition, three of the seven studies reported significant reductions in musculotendinous and ligament injuries following a static stretching protocol.

“There is moderate to strong evidence that routine application of static stretching does not reduce overall injury rates,” the researchers concluded. “There is preliminary evidence, however, that static stretching may reduce musculotendinous injuries.”

The final study Dr. Cothran discussed was a systematic review of two randomized, controlled trials and two prospective cohort studies on the effect of stretching in sports injury prevention that appeared in the literature between 1998 and 2008 (J Comm Health Sci. 2008;3[1]:51-8).

One cohort study found that stretching reduced the incidence of exercise-related injuries, while two randomized, controlled trials and one cohort study found that stretching did not produce a practical reduction on the occurrence of injuries. The researchers concluded that stretching exercises “do not give a practical, useful reduction in the risk of injuries.”

Some studies have demonstrated that explosive athletic performance such as sprinting may be compromised by acute stretching, noted Dr. Cothran, who is also program director of the primary care sports medicine fellowship at the University of Maryland, Baltimore. Current practice and research gaps include few recent randomized, controlled trials; few studies isolating stretching alone; and few that compare the different forms of stretching, such as dynamic and static stretching, she added.

“There is moderate to strong evidence that routine stretching before exercise will not reduce injury rates,” she concluded. “There is evidence that stretching before exercise may negatively affect performance. Flexibility training can be beneficial but should take place at alternative times and not before exercise.”

Dr. Joy disclosed that she receives funding from Savvysherpa and Dexcom for a project on the prevention of gestational diabetes. Dr. Roberts and Dr. Cothran reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Is it okay for pregnant women to attend CrossFit classes? Are patients who run for fun at increased risk for osteoarthritis? Does stretching before exercise provide any benefits to athletes?

Experts discussed these topics during a session titled “Mythbusters in sports medicine” at the annual meeting of the American Medical Society for Sports Medicine.

Does exercise negatively impact pregnancy?

The idea that strenuous exercise during pregnancy can harm a baby’s health is a myth, according to Elizabeth A. Joy, MD.

“Women having healthy, uncomplicated pregnancies should be encouraged to be physically active throughout pregnancy, with a goal of achieving 150 minutes per week of moderate-intensity activity,” she said. “Fit pregnant women who were habitually performing high-intensity exercise before pregnancy can continue to do so during pregnancy, assuming an otherwise healthy, uncomplicated pregnancy.”

Results from more than 600 studies in the medical literature indicate that exercise during pregnancy is safe for moms and babies, noted Dr. Joy, medical director for community health and food and nutrition at Intermountain Healthcare in Salt Lake City, Utah.

In fact, the 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans state that pregnant women who habitually engage in vigorous-intensity aerobic activity or who are highly active “can continue physical activity during pregnancy and the postpartum period, provided that they remain healthy and discuss with their health care provider how and when activity should be adjusted over time.”

Such advice wasn’t always supported by the medical profession. In fact, 1985 guidelines from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommended that women limit exercise to no more than 15 minutes at a time during pregnancy and keep their maternal heart rate less than 140 beats per minute. ACOG also discouraged previously sedentary women from beginning an exercise program during pregnancy.

“Sadly, women are still getting this advice,” said Dr. Joy, who is also president of the American College of Sports Medicine. According to the 2005-2010 National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, only 18% of pregnant women reported receiving counseling to be physically active during their pregnancies (Matern Child Health J. 2014 Sep;18[7]:1610-18). “That is just unacceptable,” she said.

In a prospective study of the association between vigorous physical activity during pregnancy and length of gestation and birth weight, researchers evaluated 1,647 births among primiparous women (Matern Child Health J. 2012 Jul;16[5]:1031-44).

They conducted telephone interviews with the women between 7-20 weeks gestation and assigned metabolic equivalent of task values to self-reported levels of physical activity. Of the 1,647 births, 7% were preterm.

Slightly more than one-third of the women (35%) performed first-trimester vigorous physical activity. The average total vigorous activity reported was 76 minutes per week, 38% of which was vigorous recreational activity.

Women who performed first-trimester vigorous recreational physical activity tended to have lower odds of preterm birth. They also tended to have lighter-weight babies, but this did not reach statistical significance (P = .08). The authors concluded that first-trimester vigorous physical activity “does not appear to be detrimental to the timing of birth or birth weight.”

In a separate analysis, researchers evaluated acute fetal responses to individually prescribed exercise according to existing physical activity guidelines in active and inactive pregnant women (Obstet Gynecol. 2012 Mar;119[3]:603-10).

Of the 45 study participants, 15 were classified as nonexercisers, 15 were regularly active, and 15 were highly active. The women underwent treadmill assessment between 28 weeks and 33 weeks, while fetal assessment included umbilical artery Doppler, fetal heart tracing and rate, and biophysical profile at rest and immediately post exercise.

The researchers observed no differences between the groups in mode of delivery, birth weight, and Apgar scores. During vigorous-intensity exercise, all umbilical artery indices showed decreases post exercise.

“Although statistically significant, this decrease is likely not clinically significant,” the researchers wrote. “We did not identify any adverse acute fetal responses to current exercise recommendations.” They went on to conclude that the potential health benefits of exercise “are too great for [physicians] to miss the opportunity to effectively counsel pregnant women about this important heath-enhancing behavior.”

In a more recent randomized study, Swedish researchers evaluated the efficacy of moderate-to-vigorous resistance exercise in 92 pregnant women (Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2015 Jan; 94[1]:35-42).

The intervention group received supervised resistance exercise twice per week at moderate-to-vigorous intensity between 14-25 weeks of their pregnancy, while the control group received a generalized home exercise program. Outcome measures included health-related quality of life, physical strength, pain, weight, blood pressure, functional status, activity level, and perinatal data.

The researchers found no significant differences between the two groups and concluded that “supervised regular, moderate-to-vigorous resistance exercise performed twice per week does not adversely impact childbirth outcome, pain, or blood pressure.”

Despite all that’s known about exercise during pregnancy, a few practice and research gaps remain.

For one, Dr. Joy said, the relationship between performing physically demanding work during pregnancy in combination with moderate-to-vigorous exercise remains largely unknown.

“Even within health care, you have residents, nurses, and others working in hospitals,” she said. “That’s demanding work, but we don’t know whether or not moderate-to-vigorous exercise in combination with that kind of work is safe. Also, although women tend to thermoregulate better during pregnancy, we still don’t fully understand the impact of elevated core body temperature, which may occur with regularly performed vigorous-intensity exercise over the course of pregnancy.”

Does running cause knee OA?