User login

Monkeypox virus found in asymptomatic people

The findings, published in Annals of Internal Medicine, follow a similar, non–peer-reviewed report from Belgium. Researchers in both studies tested swabs for monkeypox in men who have sex with men. These swabs had been collected for routine STI screening.

It’s unclear whether asymptomatic individuals who test positive for monkeypox can spread the virus, the French team wrote. But if so, public health strategies to vaccinate those with known exposure “may not be sufficient to contain spread.”

In an editorial accompanying their paper, Stuart Isaacs, MD, associate professor at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said it “raises the question of whether asymptomatic or subclinical infections are contributing to the current worldwide outbreak.”

Historically, transmission of monkeypox and its close relative, smallpox, was thought to be greatest when a rash was present, Dr. Isaacs wrote. “Long chains of human-to-human transmission were rare” with monkeypox.

That’s changed with the current outbreak, which was first detected in May. On Aug. 17, the World Health Organization reported more than 35,000 cases in 92 countries, with 12 deaths.

Research methods

For the French study, researchers conducted polymerase chain reaction tests on 200 anorectal swabs from asymptomatic individuals that had been collected from June 5 to July 11 in order to screen for gonorrhea and chlamydia. Of those, 13 (6.5%) were positive for monkeypox.

During the study period, STI testing had been suspended in individuals with monkeypox symptoms because of safety concerns, the researchers reported.

The research team contacted the 13 monkeypox-positive patients and advised them to limit sexual activity for 21 days following their test and notify recent sexual partners. None reported having developed symptoms, but two subsequently returned to the clinic with symptoms – one had an anal rash and the other a sore throat.

In the Belgian report, posted publicly on June 21 as a preprint, 3 of 224 anal samples collected for STI screening in May tested positive for monkeypox. All three of the men who tested positive said they did not have any symptoms in the weeks before and after the sample was taken.

At follow-up testing, 21-37 days after the initial samples were taken, all patients who had previously tested positive were negative. This was “likely as a consequence of spontaneous clearance of the infection,” the authors of that paper wrote.

Clinical implications of findings are uncertain

Monica Gandhi, MD, MPH, a professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, said in an interview that the clinical implications of the findings are uncertain because it’s not known how much viral transmission results from asymptomatic individuals.

Nevertheless, Dr. Gandhi said that “vaccinating all gay men for monkeypox who will accept the vaccine is prudent,” compared with a less aggressive strategy of only vaccinating those with known exposure, which is called ring vaccination. That way, “we can be assured to provide immunity to large swaths of the at-risk population.”

Dr. Gandhi said that movement toward mass vaccination of gay men is occurring in the United States, Canada, Europe, and Australia, despite limited vaccine supply.

She added that, although monkeypox has been concentrated in communities of men who have sex with men, “anyone with multiple sexual partners should be vaccinated given the data.”

However, a WHO official recently cautioned that reports of breakthrough infections in individuals who were vaccinated against monkeypox constitute a reminder that “vaccine is not a silver bullet.”

Non-vaccine interventions are also needed

Other experts stressed the need for nonvaccine interventions.

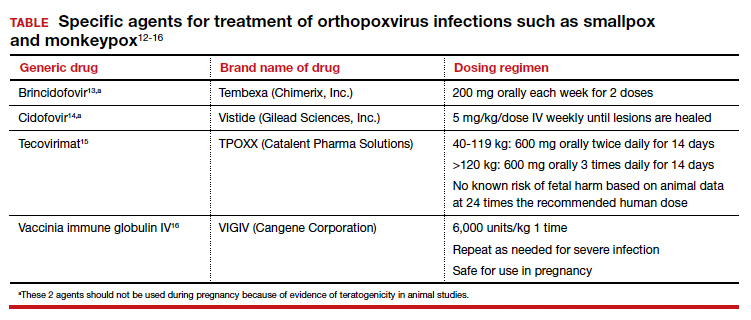

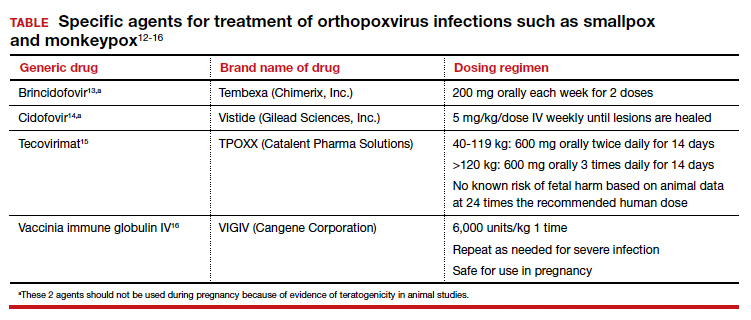

In his editorial, Dr. Isaacs said an “expanded” ring vaccination strategy in communities of high risk is likely needed, but ultimately the outbreak will only be controlled if vaccination is accompanied by other measures such as identifying and isolating cases, making treatment available, and educating individuals about how to reduce their risk.

Aileen Marty, MD, a professor of infectious diseases at Florida International University, Miami, said in an interview that the new evidence makes it “incredibly important” to inform people that they might be infected by a sex partner even if that person does not have telltale lesions.

Dr. Marty said she has been advising men who have sex with men to “reduce or eliminate situations in which they find themselves with multiple anonymous individuals.”

Although most individuals recover from monkeypox, the disease can lead to hospitalization, disfigurement, blindness, and even death, Dr. Marty noted, adding that monkeypox is “absolutely a disease to avoid.”

Authors of the French study reported financial relationships with Gilead Sciences, Viiv Healthcare, MSD, AstraZeneca, Theratechnologies, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline, and bioMérieux. Dr. Isaacs reported grants from the Department of Veterans Affairs and the National Institutes of Health and royalties from UpToDate. Dr. Gandhi and Dr. Marty reported no relevant financial interests.

The findings, published in Annals of Internal Medicine, follow a similar, non–peer-reviewed report from Belgium. Researchers in both studies tested swabs for monkeypox in men who have sex with men. These swabs had been collected for routine STI screening.

It’s unclear whether asymptomatic individuals who test positive for monkeypox can spread the virus, the French team wrote. But if so, public health strategies to vaccinate those with known exposure “may not be sufficient to contain spread.”

In an editorial accompanying their paper, Stuart Isaacs, MD, associate professor at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said it “raises the question of whether asymptomatic or subclinical infections are contributing to the current worldwide outbreak.”

Historically, transmission of monkeypox and its close relative, smallpox, was thought to be greatest when a rash was present, Dr. Isaacs wrote. “Long chains of human-to-human transmission were rare” with monkeypox.

That’s changed with the current outbreak, which was first detected in May. On Aug. 17, the World Health Organization reported more than 35,000 cases in 92 countries, with 12 deaths.

Research methods

For the French study, researchers conducted polymerase chain reaction tests on 200 anorectal swabs from asymptomatic individuals that had been collected from June 5 to July 11 in order to screen for gonorrhea and chlamydia. Of those, 13 (6.5%) were positive for monkeypox.

During the study period, STI testing had been suspended in individuals with monkeypox symptoms because of safety concerns, the researchers reported.

The research team contacted the 13 monkeypox-positive patients and advised them to limit sexual activity for 21 days following their test and notify recent sexual partners. None reported having developed symptoms, but two subsequently returned to the clinic with symptoms – one had an anal rash and the other a sore throat.

In the Belgian report, posted publicly on June 21 as a preprint, 3 of 224 anal samples collected for STI screening in May tested positive for monkeypox. All three of the men who tested positive said they did not have any symptoms in the weeks before and after the sample was taken.

At follow-up testing, 21-37 days after the initial samples were taken, all patients who had previously tested positive were negative. This was “likely as a consequence of spontaneous clearance of the infection,” the authors of that paper wrote.

Clinical implications of findings are uncertain

Monica Gandhi, MD, MPH, a professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, said in an interview that the clinical implications of the findings are uncertain because it’s not known how much viral transmission results from asymptomatic individuals.

Nevertheless, Dr. Gandhi said that “vaccinating all gay men for monkeypox who will accept the vaccine is prudent,” compared with a less aggressive strategy of only vaccinating those with known exposure, which is called ring vaccination. That way, “we can be assured to provide immunity to large swaths of the at-risk population.”

Dr. Gandhi said that movement toward mass vaccination of gay men is occurring in the United States, Canada, Europe, and Australia, despite limited vaccine supply.

She added that, although monkeypox has been concentrated in communities of men who have sex with men, “anyone with multiple sexual partners should be vaccinated given the data.”

However, a WHO official recently cautioned that reports of breakthrough infections in individuals who were vaccinated against monkeypox constitute a reminder that “vaccine is not a silver bullet.”

Non-vaccine interventions are also needed

Other experts stressed the need for nonvaccine interventions.

In his editorial, Dr. Isaacs said an “expanded” ring vaccination strategy in communities of high risk is likely needed, but ultimately the outbreak will only be controlled if vaccination is accompanied by other measures such as identifying and isolating cases, making treatment available, and educating individuals about how to reduce their risk.

Aileen Marty, MD, a professor of infectious diseases at Florida International University, Miami, said in an interview that the new evidence makes it “incredibly important” to inform people that they might be infected by a sex partner even if that person does not have telltale lesions.

Dr. Marty said she has been advising men who have sex with men to “reduce or eliminate situations in which they find themselves with multiple anonymous individuals.”

Although most individuals recover from monkeypox, the disease can lead to hospitalization, disfigurement, blindness, and even death, Dr. Marty noted, adding that monkeypox is “absolutely a disease to avoid.”

Authors of the French study reported financial relationships with Gilead Sciences, Viiv Healthcare, MSD, AstraZeneca, Theratechnologies, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline, and bioMérieux. Dr. Isaacs reported grants from the Department of Veterans Affairs and the National Institutes of Health and royalties from UpToDate. Dr. Gandhi and Dr. Marty reported no relevant financial interests.

The findings, published in Annals of Internal Medicine, follow a similar, non–peer-reviewed report from Belgium. Researchers in both studies tested swabs for monkeypox in men who have sex with men. These swabs had been collected for routine STI screening.

It’s unclear whether asymptomatic individuals who test positive for monkeypox can spread the virus, the French team wrote. But if so, public health strategies to vaccinate those with known exposure “may not be sufficient to contain spread.”

In an editorial accompanying their paper, Stuart Isaacs, MD, associate professor at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said it “raises the question of whether asymptomatic or subclinical infections are contributing to the current worldwide outbreak.”

Historically, transmission of monkeypox and its close relative, smallpox, was thought to be greatest when a rash was present, Dr. Isaacs wrote. “Long chains of human-to-human transmission were rare” with monkeypox.

That’s changed with the current outbreak, which was first detected in May. On Aug. 17, the World Health Organization reported more than 35,000 cases in 92 countries, with 12 deaths.

Research methods

For the French study, researchers conducted polymerase chain reaction tests on 200 anorectal swabs from asymptomatic individuals that had been collected from June 5 to July 11 in order to screen for gonorrhea and chlamydia. Of those, 13 (6.5%) were positive for monkeypox.

During the study period, STI testing had been suspended in individuals with monkeypox symptoms because of safety concerns, the researchers reported.

The research team contacted the 13 monkeypox-positive patients and advised them to limit sexual activity for 21 days following their test and notify recent sexual partners. None reported having developed symptoms, but two subsequently returned to the clinic with symptoms – one had an anal rash and the other a sore throat.

In the Belgian report, posted publicly on June 21 as a preprint, 3 of 224 anal samples collected for STI screening in May tested positive for monkeypox. All three of the men who tested positive said they did not have any symptoms in the weeks before and after the sample was taken.

At follow-up testing, 21-37 days after the initial samples were taken, all patients who had previously tested positive were negative. This was “likely as a consequence of spontaneous clearance of the infection,” the authors of that paper wrote.

Clinical implications of findings are uncertain

Monica Gandhi, MD, MPH, a professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, said in an interview that the clinical implications of the findings are uncertain because it’s not known how much viral transmission results from asymptomatic individuals.

Nevertheless, Dr. Gandhi said that “vaccinating all gay men for monkeypox who will accept the vaccine is prudent,” compared with a less aggressive strategy of only vaccinating those with known exposure, which is called ring vaccination. That way, “we can be assured to provide immunity to large swaths of the at-risk population.”

Dr. Gandhi said that movement toward mass vaccination of gay men is occurring in the United States, Canada, Europe, and Australia, despite limited vaccine supply.

She added that, although monkeypox has been concentrated in communities of men who have sex with men, “anyone with multiple sexual partners should be vaccinated given the data.”

However, a WHO official recently cautioned that reports of breakthrough infections in individuals who were vaccinated against monkeypox constitute a reminder that “vaccine is not a silver bullet.”

Non-vaccine interventions are also needed

Other experts stressed the need for nonvaccine interventions.

In his editorial, Dr. Isaacs said an “expanded” ring vaccination strategy in communities of high risk is likely needed, but ultimately the outbreak will only be controlled if vaccination is accompanied by other measures such as identifying and isolating cases, making treatment available, and educating individuals about how to reduce their risk.

Aileen Marty, MD, a professor of infectious diseases at Florida International University, Miami, said in an interview that the new evidence makes it “incredibly important” to inform people that they might be infected by a sex partner even if that person does not have telltale lesions.

Dr. Marty said she has been advising men who have sex with men to “reduce or eliminate situations in which they find themselves with multiple anonymous individuals.”

Although most individuals recover from monkeypox, the disease can lead to hospitalization, disfigurement, blindness, and even death, Dr. Marty noted, adding that monkeypox is “absolutely a disease to avoid.”

Authors of the French study reported financial relationships with Gilead Sciences, Viiv Healthcare, MSD, AstraZeneca, Theratechnologies, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline, and bioMérieux. Dr. Isaacs reported grants from the Department of Veterans Affairs and the National Institutes of Health and royalties from UpToDate. Dr. Gandhi and Dr. Marty reported no relevant financial interests.

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

Docs not talking about anal sex may put women at risk

Clinicians’ reluctance to discuss possible harms of anal sex may be letting down a generation of young women who are unaware of the risks, two researchers from the United Kingdom write in an opinion article published in The BMJ.

Failure to discuss the subject “exposes women to missed diagnoses, futile treatments, and further harm arising from a lack of medical advice,” write Tabitha Gana, MD, and Lesley Hunt, MD, with Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust and Northern General Hospital, both in Sheffield, United Kingdom.

In their opinion, health care professionals, particularly those in general practice, gastroenterology, and colorectal surgery, “have a duty to acknowledge changes in society around anal sex in young women and to meet these changes with open, neutral, and non-judgmental conversations to ensure that all women have the information they need to make informed choices about sex.”

Asking about anal sex is standard practice in genitourinary medicine clinics, but it’s less common in general practice and colorectal clinics, they point out.

No longer taboo

Anal intercourse is becoming more common among young heterosexual couples. In the United Kingdom, participation in heterosexual anal intercourse among people aged 16-24 years rose from about 13% to 29% over the last few decades, according to national survey data.

The same thing is happening in the United States, where research suggests 30%-44% of men and women report having anal sex.

Individual motivation for anal sex varies. Young women cite pleasure, curiosity, pleasing the male partners, and coercion as factors. Up to 25% of women with experience of anal sex report they have been pressured into it at least once, Dr. Gana and Dr. Hunt say.

However, because of its association with alcohol, drug use, and multiple sex partners, anal intercourse is considered a risky sexual behavior.

It’s also associated with specific health concerns, Dr. Gana and Dr. Hunt point out. These include fecal incontinence and anal sphincter injury, which have been reported in women who engage in anal intercourse. When it comes to incontinence, women are at higher risk than men because of their different anatomy and the effects of hormones, pregnancy, and childbirth on the pelvic floor.

“Women have less robust anal sphincters and lower anal canal pressures than men, and damage caused by anal penetration is therefore more consequential,” Dr. Gana and Dr. Hunt point out.

“The pain and bleeding women report after anal sex is indicative of trauma, and risks may be increased if anal sex is coerced,” they add.

Knowledge of the underlying risk factors and taking a good history are key to effective management of anorectal disorders, they say.

Dr. Gana and Dr. Hunt worry that clinicians may shy away from talking about anal sex, influenced by society’s taboos.

Currently, NHS patient information on anal sex considers only sexually transmitted infections, making no mention of anal trauma, incontinence, or the psychological aftermath of being coerced into anal sex.

“It may not be just avoidance or stigma that prevents health professionals [from] talking to young women about the risks of anal sex. There is genuine concern that the message may be seen as judgmental or even misconstrued as homophobic,” Dr. Gana and Dr. Hunt write.

“However, by avoiding these discussions, we may be failing a generation of young women who are unaware of the risks,” they add.

“With better information, women who want anal sex would be able to protect themselves more effectively from possible harm, and those who agree to anal sex reluctantly to meet society’s expectations or please partners may feel better empowered to say no,” Dr. Gana and Dr. Hunt say.

This research had no specific funding. Dr. Gana and Dr. Hunt report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Clinicians’ reluctance to discuss possible harms of anal sex may be letting down a generation of young women who are unaware of the risks, two researchers from the United Kingdom write in an opinion article published in The BMJ.

Failure to discuss the subject “exposes women to missed diagnoses, futile treatments, and further harm arising from a lack of medical advice,” write Tabitha Gana, MD, and Lesley Hunt, MD, with Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust and Northern General Hospital, both in Sheffield, United Kingdom.

In their opinion, health care professionals, particularly those in general practice, gastroenterology, and colorectal surgery, “have a duty to acknowledge changes in society around anal sex in young women and to meet these changes with open, neutral, and non-judgmental conversations to ensure that all women have the information they need to make informed choices about sex.”

Asking about anal sex is standard practice in genitourinary medicine clinics, but it’s less common in general practice and colorectal clinics, they point out.

No longer taboo

Anal intercourse is becoming more common among young heterosexual couples. In the United Kingdom, participation in heterosexual anal intercourse among people aged 16-24 years rose from about 13% to 29% over the last few decades, according to national survey data.

The same thing is happening in the United States, where research suggests 30%-44% of men and women report having anal sex.

Individual motivation for anal sex varies. Young women cite pleasure, curiosity, pleasing the male partners, and coercion as factors. Up to 25% of women with experience of anal sex report they have been pressured into it at least once, Dr. Gana and Dr. Hunt say.

However, because of its association with alcohol, drug use, and multiple sex partners, anal intercourse is considered a risky sexual behavior.

It’s also associated with specific health concerns, Dr. Gana and Dr. Hunt point out. These include fecal incontinence and anal sphincter injury, which have been reported in women who engage in anal intercourse. When it comes to incontinence, women are at higher risk than men because of their different anatomy and the effects of hormones, pregnancy, and childbirth on the pelvic floor.

“Women have less robust anal sphincters and lower anal canal pressures than men, and damage caused by anal penetration is therefore more consequential,” Dr. Gana and Dr. Hunt point out.

“The pain and bleeding women report after anal sex is indicative of trauma, and risks may be increased if anal sex is coerced,” they add.

Knowledge of the underlying risk factors and taking a good history are key to effective management of anorectal disorders, they say.

Dr. Gana and Dr. Hunt worry that clinicians may shy away from talking about anal sex, influenced by society’s taboos.

Currently, NHS patient information on anal sex considers only sexually transmitted infections, making no mention of anal trauma, incontinence, or the psychological aftermath of being coerced into anal sex.

“It may not be just avoidance or stigma that prevents health professionals [from] talking to young women about the risks of anal sex. There is genuine concern that the message may be seen as judgmental or even misconstrued as homophobic,” Dr. Gana and Dr. Hunt write.

“However, by avoiding these discussions, we may be failing a generation of young women who are unaware of the risks,” they add.

“With better information, women who want anal sex would be able to protect themselves more effectively from possible harm, and those who agree to anal sex reluctantly to meet society’s expectations or please partners may feel better empowered to say no,” Dr. Gana and Dr. Hunt say.

This research had no specific funding. Dr. Gana and Dr. Hunt report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Clinicians’ reluctance to discuss possible harms of anal sex may be letting down a generation of young women who are unaware of the risks, two researchers from the United Kingdom write in an opinion article published in The BMJ.

Failure to discuss the subject “exposes women to missed diagnoses, futile treatments, and further harm arising from a lack of medical advice,” write Tabitha Gana, MD, and Lesley Hunt, MD, with Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust and Northern General Hospital, both in Sheffield, United Kingdom.

In their opinion, health care professionals, particularly those in general practice, gastroenterology, and colorectal surgery, “have a duty to acknowledge changes in society around anal sex in young women and to meet these changes with open, neutral, and non-judgmental conversations to ensure that all women have the information they need to make informed choices about sex.”

Asking about anal sex is standard practice in genitourinary medicine clinics, but it’s less common in general practice and colorectal clinics, they point out.

No longer taboo

Anal intercourse is becoming more common among young heterosexual couples. In the United Kingdom, participation in heterosexual anal intercourse among people aged 16-24 years rose from about 13% to 29% over the last few decades, according to national survey data.

The same thing is happening in the United States, where research suggests 30%-44% of men and women report having anal sex.

Individual motivation for anal sex varies. Young women cite pleasure, curiosity, pleasing the male partners, and coercion as factors. Up to 25% of women with experience of anal sex report they have been pressured into it at least once, Dr. Gana and Dr. Hunt say.

However, because of its association with alcohol, drug use, and multiple sex partners, anal intercourse is considered a risky sexual behavior.

It’s also associated with specific health concerns, Dr. Gana and Dr. Hunt point out. These include fecal incontinence and anal sphincter injury, which have been reported in women who engage in anal intercourse. When it comes to incontinence, women are at higher risk than men because of their different anatomy and the effects of hormones, pregnancy, and childbirth on the pelvic floor.

“Women have less robust anal sphincters and lower anal canal pressures than men, and damage caused by anal penetration is therefore more consequential,” Dr. Gana and Dr. Hunt point out.

“The pain and bleeding women report after anal sex is indicative of trauma, and risks may be increased if anal sex is coerced,” they add.

Knowledge of the underlying risk factors and taking a good history are key to effective management of anorectal disorders, they say.

Dr. Gana and Dr. Hunt worry that clinicians may shy away from talking about anal sex, influenced by society’s taboos.

Currently, NHS patient information on anal sex considers only sexually transmitted infections, making no mention of anal trauma, incontinence, or the psychological aftermath of being coerced into anal sex.

“It may not be just avoidance or stigma that prevents health professionals [from] talking to young women about the risks of anal sex. There is genuine concern that the message may be seen as judgmental or even misconstrued as homophobic,” Dr. Gana and Dr. Hunt write.

“However, by avoiding these discussions, we may be failing a generation of young women who are unaware of the risks,” they add.

“With better information, women who want anal sex would be able to protect themselves more effectively from possible harm, and those who agree to anal sex reluctantly to meet society’s expectations or please partners may feel better empowered to say no,” Dr. Gana and Dr. Hunt say.

This research had no specific funding. Dr. Gana and Dr. Hunt report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE BMJ

2022 Update on female sexual health

Many authors have commented on the lack of research into female sexual dysfunction, especially when compared with the hundreds of research publications related to male sexual health and dysfunction. Not surprisingly, very little has been published in the past year on the subject of female sexual health.

Recently, the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health (ISSWSH) published 2 important papers: a guideline on the use of testosterone for hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD) in women and a consensus document on the management of persistent genital arousal disorder (PGAD). The lack of funding and support for female sexual health leaves women’s health professionals with little education or guidance on how to identify and treat conditions that are likely as common in women as erectile dysfunction is in men. While we would like to rely on randomized trials to inform our clinical care, the very limited literature on female sexual health makes this difficult. Bringing together experienced clinicians who focus their practices on sexual health, ISSWSH has provided some much-needed recommendations for the management of difficult conditions.

ISSWSH provides clinical guidance on testosterone therapy for women with HSDD

Parish S, Simon J, Davis S, et al. International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health clinical practice guideline for the use of systemic testosterone for hypoactive sexual desire disorder in women. J Sex Med. 2021;18:849-867.

For development of the ISSWSH clinical practice guideline on testosterone therapy for women with HSDD, 16 international researchers and clinicians were convened. A modified Delphi method was used to establish consensus at the meeting on the recommended indications for testosterone treatment, formulations, and when measurement of testosterone levels is appropriate.

An extensive evidence-based literature review was performed, which included original research, meta-analyses, reviews, and clinical practice guidelines, to address the use of testosterone in women for management of HSDD. Notably, in 2019, representatives of 10 medical societies published a Global Consensus Position Statement on the Use of Testosterone Therapy for Women that reviewed the existing literature on testosterone’s effects on sexual dysfunction, mood, cognition, musculoskeletal, cardiovascular, and breast health as well as androgenic side effects and adverse events.1 Based on their review, the only evidence-based indication for testosterone use is for the treatment of HSDD.

Testosterone formulations, HSDD diagnosis, and sex steroid physiology

More than 10 years ago, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) reviewed an application for the use of a transdermal testosterone patch (Intrinsa) in women for the treatment of HSDD. Efficacy of treatment was clearly demonstrated, and no safety signals were found in the placebo-controlled trial. Based, however, on the opinions of regulators who were “concerned” about the potential for cardiovascular adverse outcomes and worry that the peripheral conversion of testosterone to estradiol might lead to an increase in breast cancer—worry generated from the findings of the Women’s Health Initiative (which did not demonstrate an increase in breast cancer risk with estrogen alone but only when estrogen was combined with medroxyprogesterone acetate)—the FDA declined to approve the testosterone patch for women.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition (DSM-IV) defined HSDD as “persistent or recurrent deficiency or absence of sexual fantasies and desire for sexual activity with marked distress or interpersonal difficulty.” The guideline authors noted that although the DSM-5 edition merged female arousal disorder with desire disorder into a single diagnosis, they used the DSM-IV definition as it had been the basis for the studies and literature reviewed. HSDD is a prevalent condition worldwide that affects between 12% and 53% of peri- and postmenopausal women.

The consensus guideline authors extensively reviewed the physiology and mechanism of action of sex steroids in women, particularly their impact on sexual function and the biologic alterations that occur during peri- and postmenopause.

Continue to: Consensus position and recommendations...

Consensus position and recommendations

The ISSWSH consensus guideline concluded that there is a moderate therapeutic benefit in adding testosterone therapy to achieve up to premenopausal levels in postmenopausal women with self-reported reduction in sexual desire that is causing distress as determined by a validated instrument.

The authors advise baseline hormone testing to rule out androgen excess and baseline renal, lipid, liver, and metabolic testing, even though transdermal testosterone therapy was not shown to alter these parameters in randomized trials of more than 3,000 women. Laboratory assays for both total and free testosterone are “highly unreliable” in the female range as they have been calibrated for male levels of hormone.

FDA-approved testosterone treatments for men with hypogonadism include transdermal gels, patches, intramuscular injection, and an oral formulation. Dosing for women is approximately one-tenth the dosage for treatment of men. Patients should be informed that this treatment is off-label and that long-term studies to establish safety are not available. The authors advised against the use of compounded formulations based on the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine guidelines, but they went on to say that if compounded products are used, the pharmacy should adhere to Good Manufacturing Practice and Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients standards.

Transdermal testosterone is beneficial for the treatment of HSDD in postmenopausal women after other causes of decreased desire, such as dyspareunia, relationship issues, and other general medical conditions, have been ruled out. There is no diagnostic laboratory test to confirm HSDD or to use as a therapeutic target in treatment (for total or free testosterone, as these are highly unreliable laboratory values). Although large trials have identified no safety signals, they were generally limited to 6 months in duration. Prescribing one-tenth the dose indicated for male hypogonadism results in premenopausal testosterone levels for most women. If there is no benefit after 6 months of treatment, testosterone should be discontinued.

Rare, complex sexual function disorder requires integrated biopsychosocial approach, says ISSWSH

Goldstein I, Komisaruk BR, Pukall CF, et al. International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health (ISSWSH) review of epidemiology and pathophysiology, and a consensus nomenclature and process of care for the management of persistent genital arousal disorder/genito-pelvic dyesthesia (PGAD/GPD). J Sex Med. 2021;18:665-697.

Persistent genital arousal disorder is a poorly understood and relatively rare sexual dysfunction in women. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) Practice Bulletin on Female Sexual Dysfunction does not mention this condition, leaving women’s health practitioners with little guidance as to diagnosis or management.2 Prevalence for the condition is estimated at 1% to 3%. The symptoms may be intermittent or continuous.

In a recent ISSWSH review, a consensus panel defined 5 criteria for this disorder: the perception of genital arousal that is involuntary, unrelated to sexual desire, without any identified cause, not relieved with orgasm, and distressing to the patient. The panel made a clear distinction between PGAD/ genito-pelvic dysesthesia (GPD) and Compulsive Sexual Behavior Disorder (defined by the International Classification of Diseases revision 11 as “a persistent pattern of failure to control intense, repetitive sexual impulses or urges). Because there is considerable overlap with syndromes of genital dysesthesia—itching, burning, tingling, or pain— the consensus panel elected to expand the nomenclature to describe both persistent genital arousal and genito-pelvic dysesthesia as a single syndrome, namely, PGAD/GPD.

Continue to: Negative impact of PGAD/GPD...

Negative impact of PGAD/GPD

The consensus panel identified several contributors to the overall morbidity of this complex disorder, including end organ pathology, peripheral nerve, spinal cord and central sensory processing malfunction, and significant psychological issues. PGAD/GPD also may be associated with spinal cysts, cauda equina pathology, and withdrawal from selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). Functional magnetic resonance imaging has identified specific brain regions (for example, the paracentral lobule) that are active during clitoral stimulation and that also activate during patients’ experience of persistent genital arousal.

PGAD/GPD negatively impacts sexual function, mental health, and ability to function in daily life. Of major importance is that a large proportion of people with this disorder have significant mental health disorders; in a survey, 54% of patients with PGAD reported suicidal ideation, compared with 25% of participants in a control group.

Evaluation and management recommendations

Diagnosis and management of PGAD/GPD are directed at the 5 areas of evaluation:

- end organ

- pelvis and perineum (assess for pelvic floor tension myalgia, pudendal neuropathy, pelvic congestion syndrome, or pelvic arteriovenous malformation)

- cauda equina (evaluate for neurologic deficits related to cysts compressing S2-S3 nerve roots)

- spinal cord (serotonin and norepinephrine pathways modulate nociceptive sensory activity; either SSRI/serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) withdrawal or treatment could impact PGAD/ GPD based on their actions in the spinal cord)

- brain.

The consensus panel recommends an integrated biopsychosocial model for evaluation and treatment of PGAD/GPD. Comorbid mental health conditions, such as depression and anxiety, are common. Small studies suggest that a history of sexual trauma may contribute to catastrophizing and the experience of distressing persistent genital sensations, either arousal or dyesthesia, with 46.7% to 52.6% of patients reporting childhood sexual abuse.3

PGAD/GPD is a poorly recognized source of major distress to a small but significant group of patients. Diagnosis and management require a multidisciplinary team to identify end organ, pharmacologic, neurologic, vascular, and emotional components that contribute to the syndrome. Treatment requires a biopsychosocial approach that addresses the various sources of aberrant sensory processing, including end organ disease, neuropathic signaling, spinal cord pathways, and brain signal processing. Recognizing the existence of, and approaches to, this disorder will help gynecologists understand the considerable distress and potential life-threatening consequences our patients with PGAD/GPD experience.

Future possibilities and current actualities for patient care

Research dollars and investment in female sexual dysfunction remain inadequate to address the considerable gaps that exist in evidence-based clinical guidelines. ISSWSH is working to help clinicians approach these evidence gaps with guidelines and consensus statements to help women’s health professionals identify and manage our patients with sexual concerns and symptoms. An expert consensus guideline on the assessment and management of female orgasmic disorder is currently under development (personal communication, Dr. Sheryl Kingsberg). In addition, a phase 2b trial is underway to assess the impact of topical sildenafil cream for the treatment of female arousal disorder. Stay tuned for the results of these studies.

For now, women’s health professionals have 2 FDA-approved treatment options for premenopausal women with arousal disorder, flibanserin (a daily oral medication that requires abstinence from alcohol) and bremelanotide (an injectable medication that can be used just prior to a sexual encounter). For postmenopausal women, there are no FDA-approved therapies; however, based on the ISSWSH guideline summarized above, transdermal testosterone may be offered to postmenopausal women with distressing loss of sexual desire in doses approximately one-tenth those used to treat men with androgen deficiency. These small doses are challenging to achieve consistently with the delivery systems available for FDA-approved products sold for men.

The National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine advise against the use of compounded hormonal products due to the potential for inconsistency and lack of FDA oversight in the manufacturing/compounding process. I have found and used some compounding pharmacies that are dedicated to safety, quality control, and compliance; test their products; and provide consistent, reliable compounded drugs for my patients. Consideration of compounded testosterone should be discussed with patients, and they should be informed of the current professional association guidelines. Testosterone creams may be compounded to a 1% product—20 mg/mL. Researchers in Australia have demonstrated that 5 mg of transdermal testosterone cream (one-quarter of a mL) results in typical premenopausal testosterone levels.4 When prescribing testosterone for postmenopausal women, check in with them after 6 weeks of treatment to assess impact and check blood levels to ensure that levels are not too high.

Testosterone pellets and intramuscular testosterone are not recommended and in fact should be actively avoided. These methods of administration are associated with extreme variation in hormone levels over time. There are typically supraphysiologic and quite high levels immediately after implantation or injection, followed by fairly significant drop-offs and rapid return of symptoms over time. This may lead to more and more frequent dosing and markedly elevated serum levels.

Management of PGAD/GPD is difficult, but knowing it exists as a valid syndrome will help clinicians validate patients’ symptoms and begin to approach appropriate evaluation and workup targeted to the 5 domains suggested by the ISSWSH expert panel. It is useful to understand the possible relationship to initiation or withdrawal from SSRIs or SNRIs and how aberrant norepinephrine signaling along the sensory pathways may contribute to genital dysesthesia or chronic sensations of arousal. Nonpharmacologic therapies, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy and others, are essential components of the multifaceted approach to treatment. Finally, many complex problems, such as chronic pelvic pain, vestibulodynia, vulvodynia, and chronic fatigue syndrome, are associated with childhood adverse experiences and sexual trauma. Approaching these patients with trauma-informed care is important to create the trust and therapeutic environment they need for successful multidisciplinary care. ●

- Davis SR, Baber R, Panay N, et al. Global consensus position statement on the use of testosterone therapy for women. J Sex Med. 2019;16:1331-1337.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Practice Bulletins—Gynecology. ACOG practice bulletin no. 213: Female sexual dysfunction: clinical management guidelines for obstetrician-gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134:e1-e18.

- Leiblum S, Seehuus M, Goldmeier D, et al. Psychological, medical, and pharmacological correlates of persistent genital arousal disorder. J Sex Med. 2007;4:1358-1366.

- Fooladi E, Reuter SE, Bell RJ, et al. Pharmacokinetics of a transdermal testosterone cream in healthy postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2015;22:44-49.

Many authors have commented on the lack of research into female sexual dysfunction, especially when compared with the hundreds of research publications related to male sexual health and dysfunction. Not surprisingly, very little has been published in the past year on the subject of female sexual health.

Recently, the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health (ISSWSH) published 2 important papers: a guideline on the use of testosterone for hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD) in women and a consensus document on the management of persistent genital arousal disorder (PGAD). The lack of funding and support for female sexual health leaves women’s health professionals with little education or guidance on how to identify and treat conditions that are likely as common in women as erectile dysfunction is in men. While we would like to rely on randomized trials to inform our clinical care, the very limited literature on female sexual health makes this difficult. Bringing together experienced clinicians who focus their practices on sexual health, ISSWSH has provided some much-needed recommendations for the management of difficult conditions.

ISSWSH provides clinical guidance on testosterone therapy for women with HSDD

Parish S, Simon J, Davis S, et al. International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health clinical practice guideline for the use of systemic testosterone for hypoactive sexual desire disorder in women. J Sex Med. 2021;18:849-867.

For development of the ISSWSH clinical practice guideline on testosterone therapy for women with HSDD, 16 international researchers and clinicians were convened. A modified Delphi method was used to establish consensus at the meeting on the recommended indications for testosterone treatment, formulations, and when measurement of testosterone levels is appropriate.

An extensive evidence-based literature review was performed, which included original research, meta-analyses, reviews, and clinical practice guidelines, to address the use of testosterone in women for management of HSDD. Notably, in 2019, representatives of 10 medical societies published a Global Consensus Position Statement on the Use of Testosterone Therapy for Women that reviewed the existing literature on testosterone’s effects on sexual dysfunction, mood, cognition, musculoskeletal, cardiovascular, and breast health as well as androgenic side effects and adverse events.1 Based on their review, the only evidence-based indication for testosterone use is for the treatment of HSDD.

Testosterone formulations, HSDD diagnosis, and sex steroid physiology

More than 10 years ago, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) reviewed an application for the use of a transdermal testosterone patch (Intrinsa) in women for the treatment of HSDD. Efficacy of treatment was clearly demonstrated, and no safety signals were found in the placebo-controlled trial. Based, however, on the opinions of regulators who were “concerned” about the potential for cardiovascular adverse outcomes and worry that the peripheral conversion of testosterone to estradiol might lead to an increase in breast cancer—worry generated from the findings of the Women’s Health Initiative (which did not demonstrate an increase in breast cancer risk with estrogen alone but only when estrogen was combined with medroxyprogesterone acetate)—the FDA declined to approve the testosterone patch for women.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition (DSM-IV) defined HSDD as “persistent or recurrent deficiency or absence of sexual fantasies and desire for sexual activity with marked distress or interpersonal difficulty.” The guideline authors noted that although the DSM-5 edition merged female arousal disorder with desire disorder into a single diagnosis, they used the DSM-IV definition as it had been the basis for the studies and literature reviewed. HSDD is a prevalent condition worldwide that affects between 12% and 53% of peri- and postmenopausal women.

The consensus guideline authors extensively reviewed the physiology and mechanism of action of sex steroids in women, particularly their impact on sexual function and the biologic alterations that occur during peri- and postmenopause.

Continue to: Consensus position and recommendations...

Consensus position and recommendations

The ISSWSH consensus guideline concluded that there is a moderate therapeutic benefit in adding testosterone therapy to achieve up to premenopausal levels in postmenopausal women with self-reported reduction in sexual desire that is causing distress as determined by a validated instrument.

The authors advise baseline hormone testing to rule out androgen excess and baseline renal, lipid, liver, and metabolic testing, even though transdermal testosterone therapy was not shown to alter these parameters in randomized trials of more than 3,000 women. Laboratory assays for both total and free testosterone are “highly unreliable” in the female range as they have been calibrated for male levels of hormone.

FDA-approved testosterone treatments for men with hypogonadism include transdermal gels, patches, intramuscular injection, and an oral formulation. Dosing for women is approximately one-tenth the dosage for treatment of men. Patients should be informed that this treatment is off-label and that long-term studies to establish safety are not available. The authors advised against the use of compounded formulations based on the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine guidelines, but they went on to say that if compounded products are used, the pharmacy should adhere to Good Manufacturing Practice and Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients standards.

Transdermal testosterone is beneficial for the treatment of HSDD in postmenopausal women after other causes of decreased desire, such as dyspareunia, relationship issues, and other general medical conditions, have been ruled out. There is no diagnostic laboratory test to confirm HSDD or to use as a therapeutic target in treatment (for total or free testosterone, as these are highly unreliable laboratory values). Although large trials have identified no safety signals, they were generally limited to 6 months in duration. Prescribing one-tenth the dose indicated for male hypogonadism results in premenopausal testosterone levels for most women. If there is no benefit after 6 months of treatment, testosterone should be discontinued.

Rare, complex sexual function disorder requires integrated biopsychosocial approach, says ISSWSH

Goldstein I, Komisaruk BR, Pukall CF, et al. International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health (ISSWSH) review of epidemiology and pathophysiology, and a consensus nomenclature and process of care for the management of persistent genital arousal disorder/genito-pelvic dyesthesia (PGAD/GPD). J Sex Med. 2021;18:665-697.

Persistent genital arousal disorder is a poorly understood and relatively rare sexual dysfunction in women. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) Practice Bulletin on Female Sexual Dysfunction does not mention this condition, leaving women’s health practitioners with little guidance as to diagnosis or management.2 Prevalence for the condition is estimated at 1% to 3%. The symptoms may be intermittent or continuous.

In a recent ISSWSH review, a consensus panel defined 5 criteria for this disorder: the perception of genital arousal that is involuntary, unrelated to sexual desire, without any identified cause, not relieved with orgasm, and distressing to the patient. The panel made a clear distinction between PGAD/ genito-pelvic dysesthesia (GPD) and Compulsive Sexual Behavior Disorder (defined by the International Classification of Diseases revision 11 as “a persistent pattern of failure to control intense, repetitive sexual impulses or urges). Because there is considerable overlap with syndromes of genital dysesthesia—itching, burning, tingling, or pain— the consensus panel elected to expand the nomenclature to describe both persistent genital arousal and genito-pelvic dysesthesia as a single syndrome, namely, PGAD/GPD.

Continue to: Negative impact of PGAD/GPD...

Negative impact of PGAD/GPD

The consensus panel identified several contributors to the overall morbidity of this complex disorder, including end organ pathology, peripheral nerve, spinal cord and central sensory processing malfunction, and significant psychological issues. PGAD/GPD also may be associated with spinal cysts, cauda equina pathology, and withdrawal from selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). Functional magnetic resonance imaging has identified specific brain regions (for example, the paracentral lobule) that are active during clitoral stimulation and that also activate during patients’ experience of persistent genital arousal.

PGAD/GPD negatively impacts sexual function, mental health, and ability to function in daily life. Of major importance is that a large proportion of people with this disorder have significant mental health disorders; in a survey, 54% of patients with PGAD reported suicidal ideation, compared with 25% of participants in a control group.

Evaluation and management recommendations

Diagnosis and management of PGAD/GPD are directed at the 5 areas of evaluation:

- end organ

- pelvis and perineum (assess for pelvic floor tension myalgia, pudendal neuropathy, pelvic congestion syndrome, or pelvic arteriovenous malformation)

- cauda equina (evaluate for neurologic deficits related to cysts compressing S2-S3 nerve roots)

- spinal cord (serotonin and norepinephrine pathways modulate nociceptive sensory activity; either SSRI/serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) withdrawal or treatment could impact PGAD/ GPD based on their actions in the spinal cord)

- brain.

The consensus panel recommends an integrated biopsychosocial model for evaluation and treatment of PGAD/GPD. Comorbid mental health conditions, such as depression and anxiety, are common. Small studies suggest that a history of sexual trauma may contribute to catastrophizing and the experience of distressing persistent genital sensations, either arousal or dyesthesia, with 46.7% to 52.6% of patients reporting childhood sexual abuse.3

PGAD/GPD is a poorly recognized source of major distress to a small but significant group of patients. Diagnosis and management require a multidisciplinary team to identify end organ, pharmacologic, neurologic, vascular, and emotional components that contribute to the syndrome. Treatment requires a biopsychosocial approach that addresses the various sources of aberrant sensory processing, including end organ disease, neuropathic signaling, spinal cord pathways, and brain signal processing. Recognizing the existence of, and approaches to, this disorder will help gynecologists understand the considerable distress and potential life-threatening consequences our patients with PGAD/GPD experience.

Future possibilities and current actualities for patient care

Research dollars and investment in female sexual dysfunction remain inadequate to address the considerable gaps that exist in evidence-based clinical guidelines. ISSWSH is working to help clinicians approach these evidence gaps with guidelines and consensus statements to help women’s health professionals identify and manage our patients with sexual concerns and symptoms. An expert consensus guideline on the assessment and management of female orgasmic disorder is currently under development (personal communication, Dr. Sheryl Kingsberg). In addition, a phase 2b trial is underway to assess the impact of topical sildenafil cream for the treatment of female arousal disorder. Stay tuned for the results of these studies.

For now, women’s health professionals have 2 FDA-approved treatment options for premenopausal women with arousal disorder, flibanserin (a daily oral medication that requires abstinence from alcohol) and bremelanotide (an injectable medication that can be used just prior to a sexual encounter). For postmenopausal women, there are no FDA-approved therapies; however, based on the ISSWSH guideline summarized above, transdermal testosterone may be offered to postmenopausal women with distressing loss of sexual desire in doses approximately one-tenth those used to treat men with androgen deficiency. These small doses are challenging to achieve consistently with the delivery systems available for FDA-approved products sold for men.

The National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine advise against the use of compounded hormonal products due to the potential for inconsistency and lack of FDA oversight in the manufacturing/compounding process. I have found and used some compounding pharmacies that are dedicated to safety, quality control, and compliance; test their products; and provide consistent, reliable compounded drugs for my patients. Consideration of compounded testosterone should be discussed with patients, and they should be informed of the current professional association guidelines. Testosterone creams may be compounded to a 1% product—20 mg/mL. Researchers in Australia have demonstrated that 5 mg of transdermal testosterone cream (one-quarter of a mL) results in typical premenopausal testosterone levels.4 When prescribing testosterone for postmenopausal women, check in with them after 6 weeks of treatment to assess impact and check blood levels to ensure that levels are not too high.

Testosterone pellets and intramuscular testosterone are not recommended and in fact should be actively avoided. These methods of administration are associated with extreme variation in hormone levels over time. There are typically supraphysiologic and quite high levels immediately after implantation or injection, followed by fairly significant drop-offs and rapid return of symptoms over time. This may lead to more and more frequent dosing and markedly elevated serum levels.

Management of PGAD/GPD is difficult, but knowing it exists as a valid syndrome will help clinicians validate patients’ symptoms and begin to approach appropriate evaluation and workup targeted to the 5 domains suggested by the ISSWSH expert panel. It is useful to understand the possible relationship to initiation or withdrawal from SSRIs or SNRIs and how aberrant norepinephrine signaling along the sensory pathways may contribute to genital dysesthesia or chronic sensations of arousal. Nonpharmacologic therapies, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy and others, are essential components of the multifaceted approach to treatment. Finally, many complex problems, such as chronic pelvic pain, vestibulodynia, vulvodynia, and chronic fatigue syndrome, are associated with childhood adverse experiences and sexual trauma. Approaching these patients with trauma-informed care is important to create the trust and therapeutic environment they need for successful multidisciplinary care. ●

Many authors have commented on the lack of research into female sexual dysfunction, especially when compared with the hundreds of research publications related to male sexual health and dysfunction. Not surprisingly, very little has been published in the past year on the subject of female sexual health.

Recently, the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health (ISSWSH) published 2 important papers: a guideline on the use of testosterone for hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD) in women and a consensus document on the management of persistent genital arousal disorder (PGAD). The lack of funding and support for female sexual health leaves women’s health professionals with little education or guidance on how to identify and treat conditions that are likely as common in women as erectile dysfunction is in men. While we would like to rely on randomized trials to inform our clinical care, the very limited literature on female sexual health makes this difficult. Bringing together experienced clinicians who focus their practices on sexual health, ISSWSH has provided some much-needed recommendations for the management of difficult conditions.

ISSWSH provides clinical guidance on testosterone therapy for women with HSDD

Parish S, Simon J, Davis S, et al. International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health clinical practice guideline for the use of systemic testosterone for hypoactive sexual desire disorder in women. J Sex Med. 2021;18:849-867.

For development of the ISSWSH clinical practice guideline on testosterone therapy for women with HSDD, 16 international researchers and clinicians were convened. A modified Delphi method was used to establish consensus at the meeting on the recommended indications for testosterone treatment, formulations, and when measurement of testosterone levels is appropriate.

An extensive evidence-based literature review was performed, which included original research, meta-analyses, reviews, and clinical practice guidelines, to address the use of testosterone in women for management of HSDD. Notably, in 2019, representatives of 10 medical societies published a Global Consensus Position Statement on the Use of Testosterone Therapy for Women that reviewed the existing literature on testosterone’s effects on sexual dysfunction, mood, cognition, musculoskeletal, cardiovascular, and breast health as well as androgenic side effects and adverse events.1 Based on their review, the only evidence-based indication for testosterone use is for the treatment of HSDD.

Testosterone formulations, HSDD diagnosis, and sex steroid physiology

More than 10 years ago, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) reviewed an application for the use of a transdermal testosterone patch (Intrinsa) in women for the treatment of HSDD. Efficacy of treatment was clearly demonstrated, and no safety signals were found in the placebo-controlled trial. Based, however, on the opinions of regulators who were “concerned” about the potential for cardiovascular adverse outcomes and worry that the peripheral conversion of testosterone to estradiol might lead to an increase in breast cancer—worry generated from the findings of the Women’s Health Initiative (which did not demonstrate an increase in breast cancer risk with estrogen alone but only when estrogen was combined with medroxyprogesterone acetate)—the FDA declined to approve the testosterone patch for women.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition (DSM-IV) defined HSDD as “persistent or recurrent deficiency or absence of sexual fantasies and desire for sexual activity with marked distress or interpersonal difficulty.” The guideline authors noted that although the DSM-5 edition merged female arousal disorder with desire disorder into a single diagnosis, they used the DSM-IV definition as it had been the basis for the studies and literature reviewed. HSDD is a prevalent condition worldwide that affects between 12% and 53% of peri- and postmenopausal women.

The consensus guideline authors extensively reviewed the physiology and mechanism of action of sex steroids in women, particularly their impact on sexual function and the biologic alterations that occur during peri- and postmenopause.

Continue to: Consensus position and recommendations...

Consensus position and recommendations

The ISSWSH consensus guideline concluded that there is a moderate therapeutic benefit in adding testosterone therapy to achieve up to premenopausal levels in postmenopausal women with self-reported reduction in sexual desire that is causing distress as determined by a validated instrument.

The authors advise baseline hormone testing to rule out androgen excess and baseline renal, lipid, liver, and metabolic testing, even though transdermal testosterone therapy was not shown to alter these parameters in randomized trials of more than 3,000 women. Laboratory assays for both total and free testosterone are “highly unreliable” in the female range as they have been calibrated for male levels of hormone.

FDA-approved testosterone treatments for men with hypogonadism include transdermal gels, patches, intramuscular injection, and an oral formulation. Dosing for women is approximately one-tenth the dosage for treatment of men. Patients should be informed that this treatment is off-label and that long-term studies to establish safety are not available. The authors advised against the use of compounded formulations based on the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine guidelines, but they went on to say that if compounded products are used, the pharmacy should adhere to Good Manufacturing Practice and Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients standards.

Transdermal testosterone is beneficial for the treatment of HSDD in postmenopausal women after other causes of decreased desire, such as dyspareunia, relationship issues, and other general medical conditions, have been ruled out. There is no diagnostic laboratory test to confirm HSDD or to use as a therapeutic target in treatment (for total or free testosterone, as these are highly unreliable laboratory values). Although large trials have identified no safety signals, they were generally limited to 6 months in duration. Prescribing one-tenth the dose indicated for male hypogonadism results in premenopausal testosterone levels for most women. If there is no benefit after 6 months of treatment, testosterone should be discontinued.

Rare, complex sexual function disorder requires integrated biopsychosocial approach, says ISSWSH

Goldstein I, Komisaruk BR, Pukall CF, et al. International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health (ISSWSH) review of epidemiology and pathophysiology, and a consensus nomenclature and process of care for the management of persistent genital arousal disorder/genito-pelvic dyesthesia (PGAD/GPD). J Sex Med. 2021;18:665-697.

Persistent genital arousal disorder is a poorly understood and relatively rare sexual dysfunction in women. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) Practice Bulletin on Female Sexual Dysfunction does not mention this condition, leaving women’s health practitioners with little guidance as to diagnosis or management.2 Prevalence for the condition is estimated at 1% to 3%. The symptoms may be intermittent or continuous.

In a recent ISSWSH review, a consensus panel defined 5 criteria for this disorder: the perception of genital arousal that is involuntary, unrelated to sexual desire, without any identified cause, not relieved with orgasm, and distressing to the patient. The panel made a clear distinction between PGAD/ genito-pelvic dysesthesia (GPD) and Compulsive Sexual Behavior Disorder (defined by the International Classification of Diseases revision 11 as “a persistent pattern of failure to control intense, repetitive sexual impulses or urges). Because there is considerable overlap with syndromes of genital dysesthesia—itching, burning, tingling, or pain— the consensus panel elected to expand the nomenclature to describe both persistent genital arousal and genito-pelvic dysesthesia as a single syndrome, namely, PGAD/GPD.

Continue to: Negative impact of PGAD/GPD...

Negative impact of PGAD/GPD

The consensus panel identified several contributors to the overall morbidity of this complex disorder, including end organ pathology, peripheral nerve, spinal cord and central sensory processing malfunction, and significant psychological issues. PGAD/GPD also may be associated with spinal cysts, cauda equina pathology, and withdrawal from selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). Functional magnetic resonance imaging has identified specific brain regions (for example, the paracentral lobule) that are active during clitoral stimulation and that also activate during patients’ experience of persistent genital arousal.

PGAD/GPD negatively impacts sexual function, mental health, and ability to function in daily life. Of major importance is that a large proportion of people with this disorder have significant mental health disorders; in a survey, 54% of patients with PGAD reported suicidal ideation, compared with 25% of participants in a control group.

Evaluation and management recommendations

Diagnosis and management of PGAD/GPD are directed at the 5 areas of evaluation:

- end organ

- pelvis and perineum (assess for pelvic floor tension myalgia, pudendal neuropathy, pelvic congestion syndrome, or pelvic arteriovenous malformation)

- cauda equina (evaluate for neurologic deficits related to cysts compressing S2-S3 nerve roots)

- spinal cord (serotonin and norepinephrine pathways modulate nociceptive sensory activity; either SSRI/serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) withdrawal or treatment could impact PGAD/ GPD based on their actions in the spinal cord)

- brain.

The consensus panel recommends an integrated biopsychosocial model for evaluation and treatment of PGAD/GPD. Comorbid mental health conditions, such as depression and anxiety, are common. Small studies suggest that a history of sexual trauma may contribute to catastrophizing and the experience of distressing persistent genital sensations, either arousal or dyesthesia, with 46.7% to 52.6% of patients reporting childhood sexual abuse.3

PGAD/GPD is a poorly recognized source of major distress to a small but significant group of patients. Diagnosis and management require a multidisciplinary team to identify end organ, pharmacologic, neurologic, vascular, and emotional components that contribute to the syndrome. Treatment requires a biopsychosocial approach that addresses the various sources of aberrant sensory processing, including end organ disease, neuropathic signaling, spinal cord pathways, and brain signal processing. Recognizing the existence of, and approaches to, this disorder will help gynecologists understand the considerable distress and potential life-threatening consequences our patients with PGAD/GPD experience.

Future possibilities and current actualities for patient care

Research dollars and investment in female sexual dysfunction remain inadequate to address the considerable gaps that exist in evidence-based clinical guidelines. ISSWSH is working to help clinicians approach these evidence gaps with guidelines and consensus statements to help women’s health professionals identify and manage our patients with sexual concerns and symptoms. An expert consensus guideline on the assessment and management of female orgasmic disorder is currently under development (personal communication, Dr. Sheryl Kingsberg). In addition, a phase 2b trial is underway to assess the impact of topical sildenafil cream for the treatment of female arousal disorder. Stay tuned for the results of these studies.

For now, women’s health professionals have 2 FDA-approved treatment options for premenopausal women with arousal disorder, flibanserin (a daily oral medication that requires abstinence from alcohol) and bremelanotide (an injectable medication that can be used just prior to a sexual encounter). For postmenopausal women, there are no FDA-approved therapies; however, based on the ISSWSH guideline summarized above, transdermal testosterone may be offered to postmenopausal women with distressing loss of sexual desire in doses approximately one-tenth those used to treat men with androgen deficiency. These small doses are challenging to achieve consistently with the delivery systems available for FDA-approved products sold for men.

The National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine advise against the use of compounded hormonal products due to the potential for inconsistency and lack of FDA oversight in the manufacturing/compounding process. I have found and used some compounding pharmacies that are dedicated to safety, quality control, and compliance; test their products; and provide consistent, reliable compounded drugs for my patients. Consideration of compounded testosterone should be discussed with patients, and they should be informed of the current professional association guidelines. Testosterone creams may be compounded to a 1% product—20 mg/mL. Researchers in Australia have demonstrated that 5 mg of transdermal testosterone cream (one-quarter of a mL) results in typical premenopausal testosterone levels.4 When prescribing testosterone for postmenopausal women, check in with them after 6 weeks of treatment to assess impact and check blood levels to ensure that levels are not too high.

Testosterone pellets and intramuscular testosterone are not recommended and in fact should be actively avoided. These methods of administration are associated with extreme variation in hormone levels over time. There are typically supraphysiologic and quite high levels immediately after implantation or injection, followed by fairly significant drop-offs and rapid return of symptoms over time. This may lead to more and more frequent dosing and markedly elevated serum levels.

Management of PGAD/GPD is difficult, but knowing it exists as a valid syndrome will help clinicians validate patients’ symptoms and begin to approach appropriate evaluation and workup targeted to the 5 domains suggested by the ISSWSH expert panel. It is useful to understand the possible relationship to initiation or withdrawal from SSRIs or SNRIs and how aberrant norepinephrine signaling along the sensory pathways may contribute to genital dysesthesia or chronic sensations of arousal. Nonpharmacologic therapies, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy and others, are essential components of the multifaceted approach to treatment. Finally, many complex problems, such as chronic pelvic pain, vestibulodynia, vulvodynia, and chronic fatigue syndrome, are associated with childhood adverse experiences and sexual trauma. Approaching these patients with trauma-informed care is important to create the trust and therapeutic environment they need for successful multidisciplinary care. ●

- Davis SR, Baber R, Panay N, et al. Global consensus position statement on the use of testosterone therapy for women. J Sex Med. 2019;16:1331-1337.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Practice Bulletins—Gynecology. ACOG practice bulletin no. 213: Female sexual dysfunction: clinical management guidelines for obstetrician-gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134:e1-e18.

- Leiblum S, Seehuus M, Goldmeier D, et al. Psychological, medical, and pharmacological correlates of persistent genital arousal disorder. J Sex Med. 2007;4:1358-1366.

- Fooladi E, Reuter SE, Bell RJ, et al. Pharmacokinetics of a transdermal testosterone cream in healthy postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2015;22:44-49.

- Davis SR, Baber R, Panay N, et al. Global consensus position statement on the use of testosterone therapy for women. J Sex Med. 2019;16:1331-1337.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Practice Bulletins—Gynecology. ACOG practice bulletin no. 213: Female sexual dysfunction: clinical management guidelines for obstetrician-gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134:e1-e18.

- Leiblum S, Seehuus M, Goldmeier D, et al. Psychological, medical, and pharmacological correlates of persistent genital arousal disorder. J Sex Med. 2007;4:1358-1366.

- Fooladi E, Reuter SE, Bell RJ, et al. Pharmacokinetics of a transdermal testosterone cream in healthy postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2015;22:44-49.

Monkeypox: Another emerging threat?

CASE Pregnant woman’s husband is ill after traveling

A 29-year-old primigravid woman at 18 weeks’ gestation just returned from a 10-day trip to Nigeria with her husband. While in Nigeria, the couple went on safari. On several occasions during the safari, they consumed bushmeat prepared by their guides. Her husband now has severe malaise, fever, chills, myalgias, cough, and prominent submandibular, cervical, and inguinal adenopathy. In addition, he has developed a diffuse papular-vesicular rash on his trunk and extremities.

- What is the most likely diagnosis?

- Does this condition pose a danger to his wife?

- What treatment is indicated for his wife?

What we know

In recent weeks, the specter of another poorly understood biological threat has emerged in the medical literature and lay press: monkeypox. This article will first review the epidemiology, clinical manifestations, and diagnosis of this infection, followed by a discussion of how to prevent and treat the condition, with special emphasis on the risks that this infection poses in pregnant women.

Virology

The monkeypox virus is a member of the orthopoxvirus genus. The variola (smallpox) virus and vaccinia virus are included in this genus. It is one of the largest of all viruses, measuring 200-250 nm. It is enveloped and contains double-stranded DNA. Its natural reservoir is probably African rodents. Two distinct strains of monkeypox exist in different geographical regions of Africa: the Central African clade and the West African clade. The Central African clade is significantly more virulent than the latter, with a mortality rate approaching 10%, versus 1% in the West African clade. The incubation period of the virus ranges from 4-20 days and averages 12 days.1,2

Epidemiology

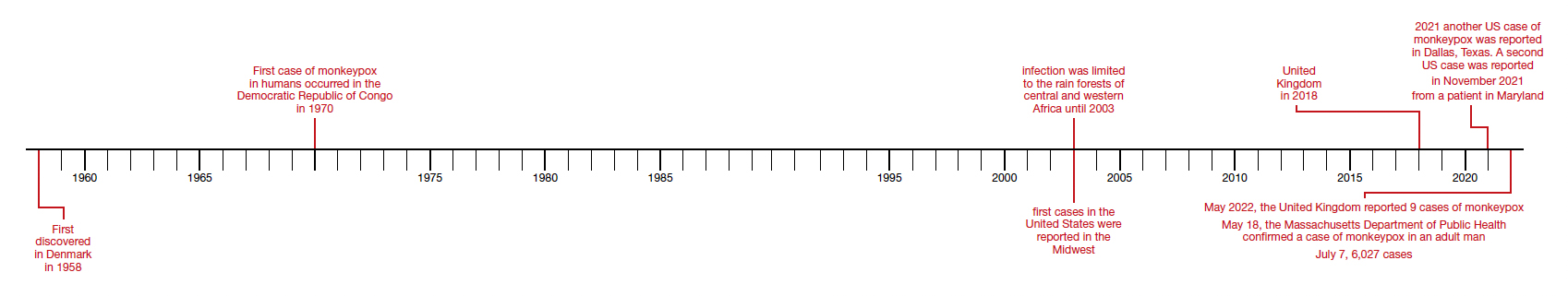

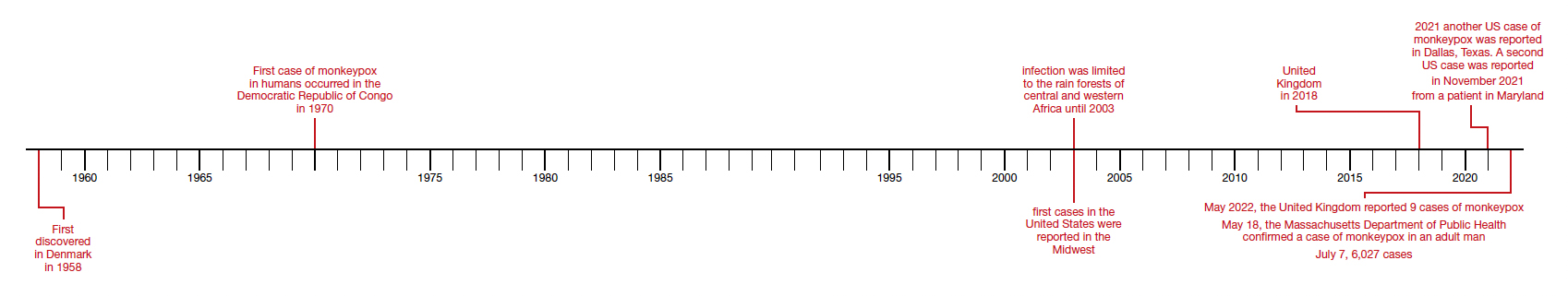

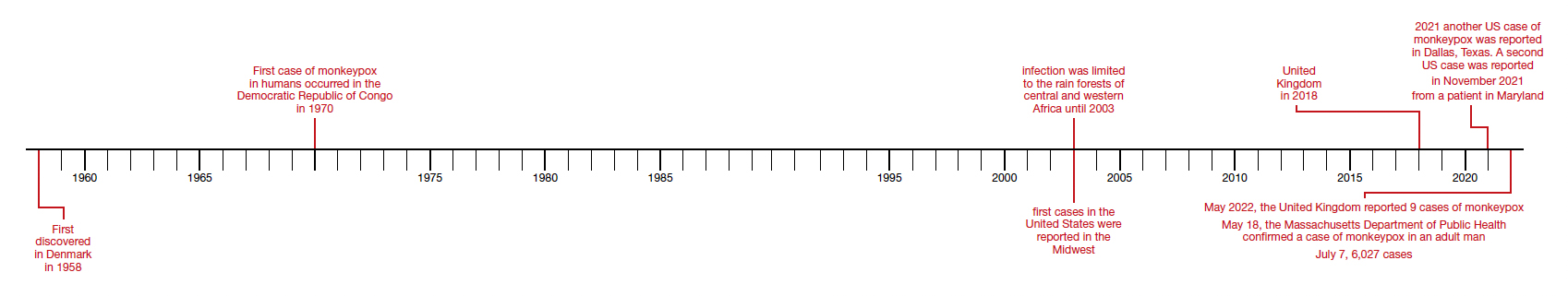

Monkeypox was first discovered in 1958 by Preben von Magnus in a colony of research monkeys in Copenhagen, Denmark. The first case of monkeypox in humans occurred in the Democratic Republic of Congo in 1970 in a 9-year-old boy. Subsequently, cases were reported in the Ivory Coast, Liberia, Nigeria, and Sierra Leone. The infection was limited to the rain forests of central and western Africa until 2003. At that time, the first cases in the United States were reported. The US cases occurred in the Midwest and were traced to exposure to pet prairie dogs. These animals all came from a single distributor, and they apparently were infected when they were housed in the same space with Gambian rats, which are well recognized reservoirs of monkeypox in their native habitat in Africa.1-3

A limited outbreak of monkeypox occurred in the United Kingdom in 2018. Seventy-one cases, with no fatalities, were reported. In 2021 another US case of monkeypox was reported in Dallas, Texas, in an individual who had recently traveled to the United States from Nigeria. A second US case was reported in November 2021 from a patient in Maryland who had returned from a visit to Nigeria. Those were the only 2 reported cases of monkeypox in the United States in 2021.1-3

Then in early May 2022, the United Kingdom reported 9 cases of monkeypox. The first infected patient had recently traveled to Nigeria and, subsequently, infected 2 members of his family.4 On May 18, the Massachusetts Department of Public Health confirmed a case of monkeypox in an adult man who had recently traveled to Canada. As of July 7, 6,027 cases have been reported from at least 39 countries.

The current outbreak is unusual in that, previously, almost all cases occurred in western and central Africa in remote tropical rain forests. Infection usually resulted from close exposure to rats, rabbits, squirrels, monkeys, porcupines, and gazelles. Exposure occurred when persons captured, slaughtered, prepared, and then ate these animals for food without properly cooking the flesh.