User login

Where women’s voices still get heard less

“Our study provides the first analysis of gender and early-career faculty disparities in speakers at hematology and medical oncology board review meetings,” the authors reported in research published in Blood Advances.

“We covered six major board reviews over the last 5 years that are either conducted yearly or every other year, [and] the general trend across all meetings showed skewness toward men speakers,” the authors reported.

Recent data from 2021 suggests a closing of the gender gap in oncology, with women making up 44.6% of oncologists in training. However, they still only represented 35.2% of practicing oncologists and are underrepresented in leadership positions in academic oncology, the authors reported.

With speaking roles at academic meetings potentially marking a key step in career advancement and improved opportunities, the authors sought to investigate the balance of gender, as well as early-career faculty among speakers at prominent hematology and/or oncology board review lecture series taking place in the United States between 2017 and 2021.

The five institutions and one society presenting the board review lecture series included Baylor College of Medicine/MD Anderson Cancer Center, both in Houston; Dana-Farber Brigham Cancer Center, Boston; George Washington University, Washington; Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York; Seattle Cancer Care Alliance; and the hematology board review series from the American Society of Hematology.

During the period in question, among 1,224 board review lectures presented, women constituted only 37.7% of the speakers. In lectures presented by American Board of Internal Medicine–certified speakers (n = 1,016, 83%), women were found to have made up fewer than 50% of speakers in five of six courses.

Men were also more likely to be recurrent speakers; across all courses, 13 men but only 2 women conducted 10 or more lectures. And while 35 men gave six or more lectures across all courses, only 12 women did so.

The lecture topics with the lowest rates of women presenters included malignant hematology (24.8%), solid tumors (38.9%), and benign hematology lectures (44.1%).

“We suspected [the imbalance in malignant hematology] since multiple recurrent roles were concentrated in the malignant hematology,” senior author Samer Al Hadidi, MD, of the Myeloma Center, Winthrop P. Rockefeller Cancer Institute, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock, AK, said in an interview.

He noted that “there are no regulations that such courses need to follow to ensure certain proportions of women and junior faculty are involved.”

Early-career faculty

In terms of early-career representation, more than 50% of lectures were given by faculty who had received their initial certifications more than 15 years earlier. The median time from initial certification was 12.5 years for hematology and 14 years for medical oncology.

The findings that more than half of the board review lectures were presented by faculty with more than 15 years’ experience since initial certification “reflects a lack of appropriate involvement of early-career faculty, who arguably may have more recent experience with board certification,” the authors wrote.

While being underrepresented in such roles is detrimental, there are no regulations that such courses follow to ensure certain proportions of women and junior faculty are involved, Dr. Al Hadidi noted.

Equal representation remains elusive

The study does suggest some notable gains. In a previous study of 181 academic conferences in the United States and Canada between 2007 and 2017, the rate of women speakers was only 15%, compared with 37.7% in the new study.

And an overall trend analysis in the study shows an approximately 10% increase in representation of women in all of the board reviews. However, only the ASH hematology board review achieved more than 50% women in their two courses.

“Overall, the proportion of women speakers is improving over the years, though it remains suboptimal,” Dr. Al Hadidi said.

The authors noted that oncology is clearly not the only specialty with gender disparities. They documented a lack of women speakers at conferences involving otolaryngology head and neck meetings, radiation oncology, emergency medicine, and research conferences.

They pointed to the work of ASH’s Women in Hematology Working Group as an important example of the needed effort to improve the balance of women hematologists.

Ariela Marshall, MD, director of women’s thrombosis and hemostasis at Penn Medicine in Philadelphia and a leader of ASH’s Women in Hematology Working Group, agreed that more efforts are needed to address both gender disparities as well as those of early career speakers. She asserted that the two disparities appear to be connected.

“If you broke down gender representation over time and the faculty/time since initial certification, the findings may mirror the percent of women in hematology-oncology at that given point in time,” Dr. Marshall said in an interview.

“If an institution is truly committed to taking action on gender equity, it needs to look at gender and experience equity of speakers,” she said. “Perhaps it’s the time to say ‘Dr. X has been doing this review course for 15 years. Let’s give someone else a chance.’

“This is not even just from a gender equity perspective but from a career development perspective overall,” she added. “Junior faculty need these speaking engagements a lot more than senior faculty.”

Meanwhile, the higher number of female trainees is a trend that ideally will be sustained as those trainees move into positions of leadership, Dr. Marshall noted.

“We do see that over time, we have achieved gender equity in the percent of women matriculating to medical school. And my hope is that, 20 years down the line, we will see the effects of this reflected in increased equity in leadership positions such as division/department chair, dean, and hospital CEO,” she said. “However, we have a lot of work to do because there are still huge inequities in the culture of medicine (institutional and more broadly), including gender-based discrimination, maternal discrimination, and high attrition rates for women physicians, compared to male physicians.

“It’s not enough to simply say ‘well, we have fixed the problem because our incoming medical student classes are now equitable in gender distribution,’ ”

The authors and Dr. Marshall had no disclosures to report.

“Our study provides the first analysis of gender and early-career faculty disparities in speakers at hematology and medical oncology board review meetings,” the authors reported in research published in Blood Advances.

“We covered six major board reviews over the last 5 years that are either conducted yearly or every other year, [and] the general trend across all meetings showed skewness toward men speakers,” the authors reported.

Recent data from 2021 suggests a closing of the gender gap in oncology, with women making up 44.6% of oncologists in training. However, they still only represented 35.2% of practicing oncologists and are underrepresented in leadership positions in academic oncology, the authors reported.

With speaking roles at academic meetings potentially marking a key step in career advancement and improved opportunities, the authors sought to investigate the balance of gender, as well as early-career faculty among speakers at prominent hematology and/or oncology board review lecture series taking place in the United States between 2017 and 2021.

The five institutions and one society presenting the board review lecture series included Baylor College of Medicine/MD Anderson Cancer Center, both in Houston; Dana-Farber Brigham Cancer Center, Boston; George Washington University, Washington; Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York; Seattle Cancer Care Alliance; and the hematology board review series from the American Society of Hematology.

During the period in question, among 1,224 board review lectures presented, women constituted only 37.7% of the speakers. In lectures presented by American Board of Internal Medicine–certified speakers (n = 1,016, 83%), women were found to have made up fewer than 50% of speakers in five of six courses.

Men were also more likely to be recurrent speakers; across all courses, 13 men but only 2 women conducted 10 or more lectures. And while 35 men gave six or more lectures across all courses, only 12 women did so.

The lecture topics with the lowest rates of women presenters included malignant hematology (24.8%), solid tumors (38.9%), and benign hematology lectures (44.1%).

“We suspected [the imbalance in malignant hematology] since multiple recurrent roles were concentrated in the malignant hematology,” senior author Samer Al Hadidi, MD, of the Myeloma Center, Winthrop P. Rockefeller Cancer Institute, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock, AK, said in an interview.

He noted that “there are no regulations that such courses need to follow to ensure certain proportions of women and junior faculty are involved.”

Early-career faculty

In terms of early-career representation, more than 50% of lectures were given by faculty who had received their initial certifications more than 15 years earlier. The median time from initial certification was 12.5 years for hematology and 14 years for medical oncology.

The findings that more than half of the board review lectures were presented by faculty with more than 15 years’ experience since initial certification “reflects a lack of appropriate involvement of early-career faculty, who arguably may have more recent experience with board certification,” the authors wrote.

While being underrepresented in such roles is detrimental, there are no regulations that such courses follow to ensure certain proportions of women and junior faculty are involved, Dr. Al Hadidi noted.

Equal representation remains elusive

The study does suggest some notable gains. In a previous study of 181 academic conferences in the United States and Canada between 2007 and 2017, the rate of women speakers was only 15%, compared with 37.7% in the new study.

And an overall trend analysis in the study shows an approximately 10% increase in representation of women in all of the board reviews. However, only the ASH hematology board review achieved more than 50% women in their two courses.

“Overall, the proportion of women speakers is improving over the years, though it remains suboptimal,” Dr. Al Hadidi said.

The authors noted that oncology is clearly not the only specialty with gender disparities. They documented a lack of women speakers at conferences involving otolaryngology head and neck meetings, radiation oncology, emergency medicine, and research conferences.

They pointed to the work of ASH’s Women in Hematology Working Group as an important example of the needed effort to improve the balance of women hematologists.

Ariela Marshall, MD, director of women’s thrombosis and hemostasis at Penn Medicine in Philadelphia and a leader of ASH’s Women in Hematology Working Group, agreed that more efforts are needed to address both gender disparities as well as those of early career speakers. She asserted that the two disparities appear to be connected.

“If you broke down gender representation over time and the faculty/time since initial certification, the findings may mirror the percent of women in hematology-oncology at that given point in time,” Dr. Marshall said in an interview.

“If an institution is truly committed to taking action on gender equity, it needs to look at gender and experience equity of speakers,” she said. “Perhaps it’s the time to say ‘Dr. X has been doing this review course for 15 years. Let’s give someone else a chance.’

“This is not even just from a gender equity perspective but from a career development perspective overall,” she added. “Junior faculty need these speaking engagements a lot more than senior faculty.”

Meanwhile, the higher number of female trainees is a trend that ideally will be sustained as those trainees move into positions of leadership, Dr. Marshall noted.

“We do see that over time, we have achieved gender equity in the percent of women matriculating to medical school. And my hope is that, 20 years down the line, we will see the effects of this reflected in increased equity in leadership positions such as division/department chair, dean, and hospital CEO,” she said. “However, we have a lot of work to do because there are still huge inequities in the culture of medicine (institutional and more broadly), including gender-based discrimination, maternal discrimination, and high attrition rates for women physicians, compared to male physicians.

“It’s not enough to simply say ‘well, we have fixed the problem because our incoming medical student classes are now equitable in gender distribution,’ ”

The authors and Dr. Marshall had no disclosures to report.

“Our study provides the first analysis of gender and early-career faculty disparities in speakers at hematology and medical oncology board review meetings,” the authors reported in research published in Blood Advances.

“We covered six major board reviews over the last 5 years that are either conducted yearly or every other year, [and] the general trend across all meetings showed skewness toward men speakers,” the authors reported.

Recent data from 2021 suggests a closing of the gender gap in oncology, with women making up 44.6% of oncologists in training. However, they still only represented 35.2% of practicing oncologists and are underrepresented in leadership positions in academic oncology, the authors reported.

With speaking roles at academic meetings potentially marking a key step in career advancement and improved opportunities, the authors sought to investigate the balance of gender, as well as early-career faculty among speakers at prominent hematology and/or oncology board review lecture series taking place in the United States between 2017 and 2021.

The five institutions and one society presenting the board review lecture series included Baylor College of Medicine/MD Anderson Cancer Center, both in Houston; Dana-Farber Brigham Cancer Center, Boston; George Washington University, Washington; Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York; Seattle Cancer Care Alliance; and the hematology board review series from the American Society of Hematology.

During the period in question, among 1,224 board review lectures presented, women constituted only 37.7% of the speakers. In lectures presented by American Board of Internal Medicine–certified speakers (n = 1,016, 83%), women were found to have made up fewer than 50% of speakers in five of six courses.

Men were also more likely to be recurrent speakers; across all courses, 13 men but only 2 women conducted 10 or more lectures. And while 35 men gave six or more lectures across all courses, only 12 women did so.

The lecture topics with the lowest rates of women presenters included malignant hematology (24.8%), solid tumors (38.9%), and benign hematology lectures (44.1%).

“We suspected [the imbalance in malignant hematology] since multiple recurrent roles were concentrated in the malignant hematology,” senior author Samer Al Hadidi, MD, of the Myeloma Center, Winthrop P. Rockefeller Cancer Institute, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock, AK, said in an interview.

He noted that “there are no regulations that such courses need to follow to ensure certain proportions of women and junior faculty are involved.”

Early-career faculty

In terms of early-career representation, more than 50% of lectures were given by faculty who had received their initial certifications more than 15 years earlier. The median time from initial certification was 12.5 years for hematology and 14 years for medical oncology.

The findings that more than half of the board review lectures were presented by faculty with more than 15 years’ experience since initial certification “reflects a lack of appropriate involvement of early-career faculty, who arguably may have more recent experience with board certification,” the authors wrote.

While being underrepresented in such roles is detrimental, there are no regulations that such courses follow to ensure certain proportions of women and junior faculty are involved, Dr. Al Hadidi noted.

Equal representation remains elusive

The study does suggest some notable gains. In a previous study of 181 academic conferences in the United States and Canada between 2007 and 2017, the rate of women speakers was only 15%, compared with 37.7% in the new study.

And an overall trend analysis in the study shows an approximately 10% increase in representation of women in all of the board reviews. However, only the ASH hematology board review achieved more than 50% women in their two courses.

“Overall, the proportion of women speakers is improving over the years, though it remains suboptimal,” Dr. Al Hadidi said.

The authors noted that oncology is clearly not the only specialty with gender disparities. They documented a lack of women speakers at conferences involving otolaryngology head and neck meetings, radiation oncology, emergency medicine, and research conferences.

They pointed to the work of ASH’s Women in Hematology Working Group as an important example of the needed effort to improve the balance of women hematologists.

Ariela Marshall, MD, director of women’s thrombosis and hemostasis at Penn Medicine in Philadelphia and a leader of ASH’s Women in Hematology Working Group, agreed that more efforts are needed to address both gender disparities as well as those of early career speakers. She asserted that the two disparities appear to be connected.

“If you broke down gender representation over time and the faculty/time since initial certification, the findings may mirror the percent of women in hematology-oncology at that given point in time,” Dr. Marshall said in an interview.

“If an institution is truly committed to taking action on gender equity, it needs to look at gender and experience equity of speakers,” she said. “Perhaps it’s the time to say ‘Dr. X has been doing this review course for 15 years. Let’s give someone else a chance.’

“This is not even just from a gender equity perspective but from a career development perspective overall,” she added. “Junior faculty need these speaking engagements a lot more than senior faculty.”

Meanwhile, the higher number of female trainees is a trend that ideally will be sustained as those trainees move into positions of leadership, Dr. Marshall noted.

“We do see that over time, we have achieved gender equity in the percent of women matriculating to medical school. And my hope is that, 20 years down the line, we will see the effects of this reflected in increased equity in leadership positions such as division/department chair, dean, and hospital CEO,” she said. “However, we have a lot of work to do because there are still huge inequities in the culture of medicine (institutional and more broadly), including gender-based discrimination, maternal discrimination, and high attrition rates for women physicians, compared to male physicians.

“It’s not enough to simply say ‘well, we have fixed the problem because our incoming medical student classes are now equitable in gender distribution,’ ”

The authors and Dr. Marshall had no disclosures to report.

FROM BLOOD ADVANCES

100 coauthored papers, 10 years: Cancer transplant pioneers model 'team science'

On July 29, 2021, Sergio Giralt, MD, deputy division head of the division of hematologic malignancies and Miguel-Angel Perales, MD, chief of the adult bone marrow transplant service at MSKCC, published their 100th peer-reviewed paper as coauthors. Listing hundreds of such articles on a CV is standard for top-tier physicians, but the pair had gone one better: 100 publications written together in 10 years.

Their centenary article hit scientific newsstands almost exactly a decade after their first joint paper, which appeared in September 2011, not long after they met.

Born in Cuba, Dr. Giralt grew up in Venezuela. From the age of 14, he knew that medicine was his path, and in 1984 he earned a medical degree from the Universidad Central de Venezuela, Caracas. Next came a research position at Harvard Medical School, a residency at the Good Samaritan Hospital, Cincinnati, and a fellowship at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston. Dr. Giralt arrived at MSKCC in 2010 as the new chief of the adult bone marrow transplant service. There he was introduced to a new colleague, Dr. Perales. They soon learned that in addition to expertise in hematology, they had second language in common: Spanish.

Dr. Giralt said: “We both have a Spanish background and in a certain sense, there was an affinity there. ... We both have shared experiences.”

Dr. Perales was brought up in Belgium, a European nation with three official languages: French, Dutch, and German. He speaks five tongues in all and learned Spanish from his father, who came from Spain.

Fluency in Spanish enables both physicians to take care of the many New Yorkers who are more comfortable in that language – especially when navigating cancer treatment. However, both Dr. Giralt and Dr. Perales said that a second language is more than a professional tool. They described the enjoyable change of persona that happens when they switch to Spanish.

“People who are multilingual have different roles [as much as] different languages,” said Dr. Perales. “When I’m in Spanish, part of my brain is [thinking back to] summer vacations and hanging out with my cousins.”

When it comes to clinical science, however, English is the language of choice.

Global leaders in HSCT

Dr. Giralt and Dr. Perales are known worldwide in the field of allogeneic HSCT, a potentially curative treatment for an elongating list of both malignant and nonmalignant diseases.

In 1973, MSKCC conducted the first bone-marrow transplant from an unrelated donor. Fifty years on, medical oncologists in the United States conduct approximately 8,500 allogeneic transplants each year, 72% to treat acute leukemias or myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS).

However, stripping the immune system with intensive chemotherapy ‘conditioning,’ then rebuilding it with non-diseased donor hematopoietic cells is a hazardous undertaking. Older patients are less likely to survive the intensive conditioning, so historically have missed out. Also, even with a good human leukocyte antigen (HLA) match, the recipient needs often brutal immunosuppression.

Since Dr. Giralt and Dr. Perales began their partnership in 2010, the goals of their work have not changed: to develop safer, lower-intensity transplantation suitable for older, more vulnerable patients and reduce fearsome posttransplant sequelae such as graft-versus-host disease (GVHD).

Dr. Giralt’s publication list spans more than 600 peer-reviewed papers, articles and book chapters, almost exclusively on HSCT. Dr. Perales has more than 300 publication credits on the topic.

The two paired up on their first paper just months after Dr. Giralt arrived at MSKCC. That article, published in Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation, compared umbilical cord blood for HSCT with donor blood in 367 people with a variety of hematologic malignancies, including acute and chronic leukemias, MDS, and lymphoma.

The MSKCC team found that transplant-related mortality in the first 180 days was higher for the cord blood (21%), but thereafter mortality and relapse were much lower than for donated blood, with the result that 2-year progression-free survival of 55% was similar. Dr. Perales, Dr. Giralt and their coauthors concluded that the data provided “strong support” for further work on cord blood as an alternative stem-cell source.

During their first decade of collaboration, Dr. Giralt and Dr. Perales worked on any promising avenue that could improve outcomes and the experience of HSCT recipients, including reduced-intensity conditioning regimens to allow older adults to benefit from curative HSCT and donor T-cell depletion by CD34 selection, to reduce graft-versus-host disease (GVHD).

The CD34 protein is typically found on the surface of early stage and highly active stem cell types. Selecting these cell types using a range of techniques can eliminate many other potentially interfering or inactive cells. This enriches the transplant population with the most effective cells and can lower the risk of GVHD.

The 100th paper on which Dr. Giralt and Dr. Perales were coauthors was published in Blood Advances on July 27, 2021. The retrospective study examined the fate of 58 MSKCC patients with a rare form of chronic lymphocytic leukemia, CLL with Richter’s transformation (CLL-RT). It was the largest such study to date of this rare disease.

M.D. Anderson Cancer Center had shown in 2006 that, despite chemotherapy, overall survival in patients with CLL-RT was approximately 8 months. HSCT improved survival dramatically (75% at 3 years; n = 7). However, with the advent of novel targeted drugs for CLL such as ibrutinib (Imbruvica), venetoclax (Venclexta), or idelalisib (Zydelig), the MSKCC team asked themselves: What was the role of reduced-intensive conditioning HSCT? Was it even safe? Among other findings, Dr. Giralt and Dr. Perales’ 100th paper showed that reduced-intensity HSCT remained a viable alternative after a CLL-RT patient progressed on a novel agent.

Impact of the pandemic

When COVID-19 hit, the team lost many research staff and developed a huge backlog, said Dr. Giralt. He and Dr. Perales realized that they needed to be “thoughtful and careful” about which studies to continue. “For example, the CD-34 selection trials we did not close because these are our workhorse trials,” Dr. Giralt said. “We have people we need to treat, and some of the patients that we need to treat can only be treated on trial.”

The team was also able to pivot some of their work into COVID 19 itself, and they collected crucial information on HSCT in recovered COVID-19 patients, as an example.

“We were living through a critical time, but that doesn’t mean we [aren’t] obligated to continue our mission, our research mission,” said Dr. Giralt. “It really is team science. The way we look at it ... there’s a common thread: We both like to do allogeneic transplant, and we both believe in trying to make CD-34 selection better. So we’re both very much [working on] how can we improve what we call ‘the Memorial way’ of doing transplants. Where we separate is, Miguel does primarily lymphoma. He doesn’t do myeloma [like me]. So in those two areas, we’re helping develop the junior faculty in a different way.”

Something more in common

Right from the start, Dr. Perales and Dr. Giralt also shared a commitment to mentoring. Since 2010, Dr. Perales has mentored 22 up-and-coming junior faculty, including 10 from Europe (8 from Spain) and 2 from Latin America.

“[It makes] the research enterprise much more productive but [these young scientists] really increase the visibility of the program,” said Dr. Giralt.

He cited Dr. Perales’ track record of mentoring as one of the reasons for his promotion to chief of the adult bone marrow transplant service. In March 2020, Dr. Perales seamlessly stepped into Dr. Giralt’s shoes, while Dr. Giralt moved on to his present role as deputy division head of the division of hematologic malignancies.

Dr. Perales said: “The key aspect [of these promotions] is the fantastic working relationship that we’ve had over the years. ... I consider Sergio my mentor, but also a good friend and colleague. And so I think it’s this ability that we’ve had to work together and that relationship of trust, which has been key.”

“Sergio is somebody who lifts people up,” Dr. Perales added. “Many people will tell you that Sergio has helped them in their career. ... And I think that’s a lesson I’ve learned from him: training the next generation. And [that’s] not just in the U.S., but outside. I think that’s a key role that we have. And our responsibility.”

Asked to comment on their 100th-paper milestone, Dr. Perales firmly turned the spotlight from himself and Dr. Giralt to the junior investigators who have passed through the doors of the bone-marrow transplant program: “This body of work represents not just our collaboration but also the many contributions of our team at MSK ... and beyond MSK.”

This article was updated 1/26/22.

On July 29, 2021, Sergio Giralt, MD, deputy division head of the division of hematologic malignancies and Miguel-Angel Perales, MD, chief of the adult bone marrow transplant service at MSKCC, published their 100th peer-reviewed paper as coauthors. Listing hundreds of such articles on a CV is standard for top-tier physicians, but the pair had gone one better: 100 publications written together in 10 years.

Their centenary article hit scientific newsstands almost exactly a decade after their first joint paper, which appeared in September 2011, not long after they met.

Born in Cuba, Dr. Giralt grew up in Venezuela. From the age of 14, he knew that medicine was his path, and in 1984 he earned a medical degree from the Universidad Central de Venezuela, Caracas. Next came a research position at Harvard Medical School, a residency at the Good Samaritan Hospital, Cincinnati, and a fellowship at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston. Dr. Giralt arrived at MSKCC in 2010 as the new chief of the adult bone marrow transplant service. There he was introduced to a new colleague, Dr. Perales. They soon learned that in addition to expertise in hematology, they had second language in common: Spanish.

Dr. Giralt said: “We both have a Spanish background and in a certain sense, there was an affinity there. ... We both have shared experiences.”

Dr. Perales was brought up in Belgium, a European nation with three official languages: French, Dutch, and German. He speaks five tongues in all and learned Spanish from his father, who came from Spain.

Fluency in Spanish enables both physicians to take care of the many New Yorkers who are more comfortable in that language – especially when navigating cancer treatment. However, both Dr. Giralt and Dr. Perales said that a second language is more than a professional tool. They described the enjoyable change of persona that happens when they switch to Spanish.

“People who are multilingual have different roles [as much as] different languages,” said Dr. Perales. “When I’m in Spanish, part of my brain is [thinking back to] summer vacations and hanging out with my cousins.”

When it comes to clinical science, however, English is the language of choice.

Global leaders in HSCT

Dr. Giralt and Dr. Perales are known worldwide in the field of allogeneic HSCT, a potentially curative treatment for an elongating list of both malignant and nonmalignant diseases.

In 1973, MSKCC conducted the first bone-marrow transplant from an unrelated donor. Fifty years on, medical oncologists in the United States conduct approximately 8,500 allogeneic transplants each year, 72% to treat acute leukemias or myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS).

However, stripping the immune system with intensive chemotherapy ‘conditioning,’ then rebuilding it with non-diseased donor hematopoietic cells is a hazardous undertaking. Older patients are less likely to survive the intensive conditioning, so historically have missed out. Also, even with a good human leukocyte antigen (HLA) match, the recipient needs often brutal immunosuppression.

Since Dr. Giralt and Dr. Perales began their partnership in 2010, the goals of their work have not changed: to develop safer, lower-intensity transplantation suitable for older, more vulnerable patients and reduce fearsome posttransplant sequelae such as graft-versus-host disease (GVHD).

Dr. Giralt’s publication list spans more than 600 peer-reviewed papers, articles and book chapters, almost exclusively on HSCT. Dr. Perales has more than 300 publication credits on the topic.

The two paired up on their first paper just months after Dr. Giralt arrived at MSKCC. That article, published in Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation, compared umbilical cord blood for HSCT with donor blood in 367 people with a variety of hematologic malignancies, including acute and chronic leukemias, MDS, and lymphoma.

The MSKCC team found that transplant-related mortality in the first 180 days was higher for the cord blood (21%), but thereafter mortality and relapse were much lower than for donated blood, with the result that 2-year progression-free survival of 55% was similar. Dr. Perales, Dr. Giralt and their coauthors concluded that the data provided “strong support” for further work on cord blood as an alternative stem-cell source.

During their first decade of collaboration, Dr. Giralt and Dr. Perales worked on any promising avenue that could improve outcomes and the experience of HSCT recipients, including reduced-intensity conditioning regimens to allow older adults to benefit from curative HSCT and donor T-cell depletion by CD34 selection, to reduce graft-versus-host disease (GVHD).

The CD34 protein is typically found on the surface of early stage and highly active stem cell types. Selecting these cell types using a range of techniques can eliminate many other potentially interfering or inactive cells. This enriches the transplant population with the most effective cells and can lower the risk of GVHD.

The 100th paper on which Dr. Giralt and Dr. Perales were coauthors was published in Blood Advances on July 27, 2021. The retrospective study examined the fate of 58 MSKCC patients with a rare form of chronic lymphocytic leukemia, CLL with Richter’s transformation (CLL-RT). It was the largest such study to date of this rare disease.

M.D. Anderson Cancer Center had shown in 2006 that, despite chemotherapy, overall survival in patients with CLL-RT was approximately 8 months. HSCT improved survival dramatically (75% at 3 years; n = 7). However, with the advent of novel targeted drugs for CLL such as ibrutinib (Imbruvica), venetoclax (Venclexta), or idelalisib (Zydelig), the MSKCC team asked themselves: What was the role of reduced-intensive conditioning HSCT? Was it even safe? Among other findings, Dr. Giralt and Dr. Perales’ 100th paper showed that reduced-intensity HSCT remained a viable alternative after a CLL-RT patient progressed on a novel agent.

Impact of the pandemic

When COVID-19 hit, the team lost many research staff and developed a huge backlog, said Dr. Giralt. He and Dr. Perales realized that they needed to be “thoughtful and careful” about which studies to continue. “For example, the CD-34 selection trials we did not close because these are our workhorse trials,” Dr. Giralt said. “We have people we need to treat, and some of the patients that we need to treat can only be treated on trial.”

The team was also able to pivot some of their work into COVID 19 itself, and they collected crucial information on HSCT in recovered COVID-19 patients, as an example.

“We were living through a critical time, but that doesn’t mean we [aren’t] obligated to continue our mission, our research mission,” said Dr. Giralt. “It really is team science. The way we look at it ... there’s a common thread: We both like to do allogeneic transplant, and we both believe in trying to make CD-34 selection better. So we’re both very much [working on] how can we improve what we call ‘the Memorial way’ of doing transplants. Where we separate is, Miguel does primarily lymphoma. He doesn’t do myeloma [like me]. So in those two areas, we’re helping develop the junior faculty in a different way.”

Something more in common

Right from the start, Dr. Perales and Dr. Giralt also shared a commitment to mentoring. Since 2010, Dr. Perales has mentored 22 up-and-coming junior faculty, including 10 from Europe (8 from Spain) and 2 from Latin America.

“[It makes] the research enterprise much more productive but [these young scientists] really increase the visibility of the program,” said Dr. Giralt.

He cited Dr. Perales’ track record of mentoring as one of the reasons for his promotion to chief of the adult bone marrow transplant service. In March 2020, Dr. Perales seamlessly stepped into Dr. Giralt’s shoes, while Dr. Giralt moved on to his present role as deputy division head of the division of hematologic malignancies.

Dr. Perales said: “The key aspect [of these promotions] is the fantastic working relationship that we’ve had over the years. ... I consider Sergio my mentor, but also a good friend and colleague. And so I think it’s this ability that we’ve had to work together and that relationship of trust, which has been key.”

“Sergio is somebody who lifts people up,” Dr. Perales added. “Many people will tell you that Sergio has helped them in their career. ... And I think that’s a lesson I’ve learned from him: training the next generation. And [that’s] not just in the U.S., but outside. I think that’s a key role that we have. And our responsibility.”

Asked to comment on their 100th-paper milestone, Dr. Perales firmly turned the spotlight from himself and Dr. Giralt to the junior investigators who have passed through the doors of the bone-marrow transplant program: “This body of work represents not just our collaboration but also the many contributions of our team at MSK ... and beyond MSK.”

This article was updated 1/26/22.

On July 29, 2021, Sergio Giralt, MD, deputy division head of the division of hematologic malignancies and Miguel-Angel Perales, MD, chief of the adult bone marrow transplant service at MSKCC, published their 100th peer-reviewed paper as coauthors. Listing hundreds of such articles on a CV is standard for top-tier physicians, but the pair had gone one better: 100 publications written together in 10 years.

Their centenary article hit scientific newsstands almost exactly a decade after their first joint paper, which appeared in September 2011, not long after they met.

Born in Cuba, Dr. Giralt grew up in Venezuela. From the age of 14, he knew that medicine was his path, and in 1984 he earned a medical degree from the Universidad Central de Venezuela, Caracas. Next came a research position at Harvard Medical School, a residency at the Good Samaritan Hospital, Cincinnati, and a fellowship at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston. Dr. Giralt arrived at MSKCC in 2010 as the new chief of the adult bone marrow transplant service. There he was introduced to a new colleague, Dr. Perales. They soon learned that in addition to expertise in hematology, they had second language in common: Spanish.

Dr. Giralt said: “We both have a Spanish background and in a certain sense, there was an affinity there. ... We both have shared experiences.”

Dr. Perales was brought up in Belgium, a European nation with three official languages: French, Dutch, and German. He speaks five tongues in all and learned Spanish from his father, who came from Spain.

Fluency in Spanish enables both physicians to take care of the many New Yorkers who are more comfortable in that language – especially when navigating cancer treatment. However, both Dr. Giralt and Dr. Perales said that a second language is more than a professional tool. They described the enjoyable change of persona that happens when they switch to Spanish.

“People who are multilingual have different roles [as much as] different languages,” said Dr. Perales. “When I’m in Spanish, part of my brain is [thinking back to] summer vacations and hanging out with my cousins.”

When it comes to clinical science, however, English is the language of choice.

Global leaders in HSCT

Dr. Giralt and Dr. Perales are known worldwide in the field of allogeneic HSCT, a potentially curative treatment for an elongating list of both malignant and nonmalignant diseases.

In 1973, MSKCC conducted the first bone-marrow transplant from an unrelated donor. Fifty years on, medical oncologists in the United States conduct approximately 8,500 allogeneic transplants each year, 72% to treat acute leukemias or myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS).

However, stripping the immune system with intensive chemotherapy ‘conditioning,’ then rebuilding it with non-diseased donor hematopoietic cells is a hazardous undertaking. Older patients are less likely to survive the intensive conditioning, so historically have missed out. Also, even with a good human leukocyte antigen (HLA) match, the recipient needs often brutal immunosuppression.

Since Dr. Giralt and Dr. Perales began their partnership in 2010, the goals of their work have not changed: to develop safer, lower-intensity transplantation suitable for older, more vulnerable patients and reduce fearsome posttransplant sequelae such as graft-versus-host disease (GVHD).

Dr. Giralt’s publication list spans more than 600 peer-reviewed papers, articles and book chapters, almost exclusively on HSCT. Dr. Perales has more than 300 publication credits on the topic.

The two paired up on their first paper just months after Dr. Giralt arrived at MSKCC. That article, published in Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation, compared umbilical cord blood for HSCT with donor blood in 367 people with a variety of hematologic malignancies, including acute and chronic leukemias, MDS, and lymphoma.

The MSKCC team found that transplant-related mortality in the first 180 days was higher for the cord blood (21%), but thereafter mortality and relapse were much lower than for donated blood, with the result that 2-year progression-free survival of 55% was similar. Dr. Perales, Dr. Giralt and their coauthors concluded that the data provided “strong support” for further work on cord blood as an alternative stem-cell source.

During their first decade of collaboration, Dr. Giralt and Dr. Perales worked on any promising avenue that could improve outcomes and the experience of HSCT recipients, including reduced-intensity conditioning regimens to allow older adults to benefit from curative HSCT and donor T-cell depletion by CD34 selection, to reduce graft-versus-host disease (GVHD).

The CD34 protein is typically found on the surface of early stage and highly active stem cell types. Selecting these cell types using a range of techniques can eliminate many other potentially interfering or inactive cells. This enriches the transplant population with the most effective cells and can lower the risk of GVHD.

The 100th paper on which Dr. Giralt and Dr. Perales were coauthors was published in Blood Advances on July 27, 2021. The retrospective study examined the fate of 58 MSKCC patients with a rare form of chronic lymphocytic leukemia, CLL with Richter’s transformation (CLL-RT). It was the largest such study to date of this rare disease.

M.D. Anderson Cancer Center had shown in 2006 that, despite chemotherapy, overall survival in patients with CLL-RT was approximately 8 months. HSCT improved survival dramatically (75% at 3 years; n = 7). However, with the advent of novel targeted drugs for CLL such as ibrutinib (Imbruvica), venetoclax (Venclexta), or idelalisib (Zydelig), the MSKCC team asked themselves: What was the role of reduced-intensive conditioning HSCT? Was it even safe? Among other findings, Dr. Giralt and Dr. Perales’ 100th paper showed that reduced-intensity HSCT remained a viable alternative after a CLL-RT patient progressed on a novel agent.

Impact of the pandemic

When COVID-19 hit, the team lost many research staff and developed a huge backlog, said Dr. Giralt. He and Dr. Perales realized that they needed to be “thoughtful and careful” about which studies to continue. “For example, the CD-34 selection trials we did not close because these are our workhorse trials,” Dr. Giralt said. “We have people we need to treat, and some of the patients that we need to treat can only be treated on trial.”

The team was also able to pivot some of their work into COVID 19 itself, and they collected crucial information on HSCT in recovered COVID-19 patients, as an example.

“We were living through a critical time, but that doesn’t mean we [aren’t] obligated to continue our mission, our research mission,” said Dr. Giralt. “It really is team science. The way we look at it ... there’s a common thread: We both like to do allogeneic transplant, and we both believe in trying to make CD-34 selection better. So we’re both very much [working on] how can we improve what we call ‘the Memorial way’ of doing transplants. Where we separate is, Miguel does primarily lymphoma. He doesn’t do myeloma [like me]. So in those two areas, we’re helping develop the junior faculty in a different way.”

Something more in common

Right from the start, Dr. Perales and Dr. Giralt also shared a commitment to mentoring. Since 2010, Dr. Perales has mentored 22 up-and-coming junior faculty, including 10 from Europe (8 from Spain) and 2 from Latin America.

“[It makes] the research enterprise much more productive but [these young scientists] really increase the visibility of the program,” said Dr. Giralt.

He cited Dr. Perales’ track record of mentoring as one of the reasons for his promotion to chief of the adult bone marrow transplant service. In March 2020, Dr. Perales seamlessly stepped into Dr. Giralt’s shoes, while Dr. Giralt moved on to his present role as deputy division head of the division of hematologic malignancies.

Dr. Perales said: “The key aspect [of these promotions] is the fantastic working relationship that we’ve had over the years. ... I consider Sergio my mentor, but also a good friend and colleague. And so I think it’s this ability that we’ve had to work together and that relationship of trust, which has been key.”

“Sergio is somebody who lifts people up,” Dr. Perales added. “Many people will tell you that Sergio has helped them in their career. ... And I think that’s a lesson I’ve learned from him: training the next generation. And [that’s] not just in the U.S., but outside. I think that’s a key role that we have. And our responsibility.”

Asked to comment on their 100th-paper milestone, Dr. Perales firmly turned the spotlight from himself and Dr. Giralt to the junior investigators who have passed through the doors of the bone-marrow transplant program: “This body of work represents not just our collaboration but also the many contributions of our team at MSK ... and beyond MSK.”

This article was updated 1/26/22.

Will TP53-mutated AML respond to immunotherapy?

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. – New research has shown increased immune infiltration in patients with TP53-mutated acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

Patients with TP53-mutated AML had higher levels of T-cell infiltration, immune checkpoint molecules, and interferon (IFN)–gamma signaling than patients with wild-type TP53.

These findings may indicate that patients with TP53-mutated AML will respond to T-cell targeting immunotherapies, but more investigation is needed, according to Sergio Rutella, MD, PhD, of Nottingham (England) Trent University.

Dr. Rutella described the findings at the annual meeting of the Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer.

He and his colleagues recently identified subgroups of AML, called “immune infiltrated” and “immune depleted,” that can predict chemotherapy resistance and response to flotetuzumab (ASH 2019, Abstract 460). However, the team has not determined the genetic drivers of immune infiltration in AML.*

With the current study, Dr. Rutella and his colleagues wanted to determine if TP53 mutations are associated with the AML immune milieu and see if TP53-mutated patients might benefit from immunotherapy.

Discovery cohort

The researchers first analyzed 147 patients with non-promyelocytic AML from the Cancer Genome Atlas. In total, 9% of these patients (n = 13) had TP53-mutated AML. The researchers assessed how 45 immune gene and biological activity signatures correlated with prognostic molecular lesions (TP53 mutations, FLT3-ITD, etc.) and clinical outcomes in this cohort.

The data showed that immune subtypes were associated with overall survival (OS). The median OS was 11.8 months in patients with immune-infiltrated AML, 16.4 months in patients with intermediate AML, and 25.8 months in patients with immune-depleted AML.

The inflammatory chemokine score (P = .011), IDO1 score (P = .027), IFN-gamma score (P = .036), and B7H3 score (P = .045) were all significantly associated with OS. In fact, these factors were all better predictors of OS than cytogenetic risk score (P = .049).

The IFN-gamma score, inflammatory chemokine score, and lymphoid score were all significantly higher in TP53-mutated patients than in patients with RUNX1 mutations, NPM1 mutations, FLT3-ITD (with or without NPM1 mutations), and TET2/DNMT3A/ASXL1 mutations (P values ranging from less than .0001 to .05).

Likewise, the tumor inflammation signature score was significantly higher among TP53-mutated patients than among patients with NPM1 mutations, FLT3-ITD (with or without NPM1 mutations), and TET2/DNMT3A/ASXL1 mutations (P values ranging from less than .0001 to .01).

Validation cohort and bone marrow samples

The researchers also looked at data from a validation cohort, which consisted of 140 patients with non-promyelocytic AML in the Beat AML Master Trial. Twelve percent of these patients (n = 17) had TP53 mutations.

Data in this cohort showed that CD3G messenger RNA (mRNA) was significantly higher in TP53-mutated AML than in TP53-wild-type AML (P = .04). The same was true for CD8A mRNA (P = .0002) and GZMB mRNA (P = .0005).

Likewise, IFN-gamma mRNA (P = .0052), IFIT2 mRNA (P = .0064), and IFIT3 mRNA (P = .003) were all significantly higher in patients with TP53-mutated AML.

Lastly, the researchers analyzed gene expression profiles of bone marrow samples from patients with AML, 36 with mutated TP53 and 24 with wild-type TP53.

The team found that IFN-gamma–induced genes (IFNG and IRF1), markers of T-cell infiltration (CD8A and CD3G) and senescence (EOMES, KLRD1, and HRAS), immune checkpoint molecules (IDO1, LAG3, PDL1, and VISTA), effector function molecules (GZMB, GZMK, and GZMM), and proinflammatory cytokines (IL17A and TNF) were all significantly overexpressed in TP53-mutated AML.

Among the top overexpressed genes in TP53-mutated AML were genes associated with IFN signaling and inflammation pathways – IL-33, IL-6, IFN-gamma, OASL, RIPK2, TNFAIP3, CSF1, and PTGER4. The IL-17 and TNF signaling pathways were the most enriched pathways in TP53-mutated AML.

“Our analysis of primary bone marrow samples showed that TP53-mutated samples are enriched in IL-17, TNF, and IFN signaling molecules, and show higher levels of T-cell infiltrations and immune checkpoints relative to their wild-type counterparts,” Dr. Rutella said.

“The in silico analysis indicated that TP53-mutated cases will show higher levels of T-cell infiltration, immune checkpoints, and IFN-gamma signaling, compared with AML subgroups without risk-defining molecular lesions,” he added. “This is speculative. Whether TP53-mutated AML can be amenable to respond to T-cell targeting immunotherapies is still to be determined.”

Dr. Rutella reported research support from NanoString Technologies, MacroGenics, and Kura Oncology.

SOURCE: Rutella S et al. SITC 2019. Abstract O3.

*This article was updated on 11/19/2019.

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. – New research has shown increased immune infiltration in patients with TP53-mutated acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

Patients with TP53-mutated AML had higher levels of T-cell infiltration, immune checkpoint molecules, and interferon (IFN)–gamma signaling than patients with wild-type TP53.

These findings may indicate that patients with TP53-mutated AML will respond to T-cell targeting immunotherapies, but more investigation is needed, according to Sergio Rutella, MD, PhD, of Nottingham (England) Trent University.

Dr. Rutella described the findings at the annual meeting of the Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer.

He and his colleagues recently identified subgroups of AML, called “immune infiltrated” and “immune depleted,” that can predict chemotherapy resistance and response to flotetuzumab (ASH 2019, Abstract 460). However, the team has not determined the genetic drivers of immune infiltration in AML.*

With the current study, Dr. Rutella and his colleagues wanted to determine if TP53 mutations are associated with the AML immune milieu and see if TP53-mutated patients might benefit from immunotherapy.

Discovery cohort

The researchers first analyzed 147 patients with non-promyelocytic AML from the Cancer Genome Atlas. In total, 9% of these patients (n = 13) had TP53-mutated AML. The researchers assessed how 45 immune gene and biological activity signatures correlated with prognostic molecular lesions (TP53 mutations, FLT3-ITD, etc.) and clinical outcomes in this cohort.

The data showed that immune subtypes were associated with overall survival (OS). The median OS was 11.8 months in patients with immune-infiltrated AML, 16.4 months in patients with intermediate AML, and 25.8 months in patients with immune-depleted AML.

The inflammatory chemokine score (P = .011), IDO1 score (P = .027), IFN-gamma score (P = .036), and B7H3 score (P = .045) were all significantly associated with OS. In fact, these factors were all better predictors of OS than cytogenetic risk score (P = .049).

The IFN-gamma score, inflammatory chemokine score, and lymphoid score were all significantly higher in TP53-mutated patients than in patients with RUNX1 mutations, NPM1 mutations, FLT3-ITD (with or without NPM1 mutations), and TET2/DNMT3A/ASXL1 mutations (P values ranging from less than .0001 to .05).

Likewise, the tumor inflammation signature score was significantly higher among TP53-mutated patients than among patients with NPM1 mutations, FLT3-ITD (with or without NPM1 mutations), and TET2/DNMT3A/ASXL1 mutations (P values ranging from less than .0001 to .01).

Validation cohort and bone marrow samples

The researchers also looked at data from a validation cohort, which consisted of 140 patients with non-promyelocytic AML in the Beat AML Master Trial. Twelve percent of these patients (n = 17) had TP53 mutations.

Data in this cohort showed that CD3G messenger RNA (mRNA) was significantly higher in TP53-mutated AML than in TP53-wild-type AML (P = .04). The same was true for CD8A mRNA (P = .0002) and GZMB mRNA (P = .0005).

Likewise, IFN-gamma mRNA (P = .0052), IFIT2 mRNA (P = .0064), and IFIT3 mRNA (P = .003) were all significantly higher in patients with TP53-mutated AML.

Lastly, the researchers analyzed gene expression profiles of bone marrow samples from patients with AML, 36 with mutated TP53 and 24 with wild-type TP53.

The team found that IFN-gamma–induced genes (IFNG and IRF1), markers of T-cell infiltration (CD8A and CD3G) and senescence (EOMES, KLRD1, and HRAS), immune checkpoint molecules (IDO1, LAG3, PDL1, and VISTA), effector function molecules (GZMB, GZMK, and GZMM), and proinflammatory cytokines (IL17A and TNF) were all significantly overexpressed in TP53-mutated AML.

Among the top overexpressed genes in TP53-mutated AML were genes associated with IFN signaling and inflammation pathways – IL-33, IL-6, IFN-gamma, OASL, RIPK2, TNFAIP3, CSF1, and PTGER4. The IL-17 and TNF signaling pathways were the most enriched pathways in TP53-mutated AML.

“Our analysis of primary bone marrow samples showed that TP53-mutated samples are enriched in IL-17, TNF, and IFN signaling molecules, and show higher levels of T-cell infiltrations and immune checkpoints relative to their wild-type counterparts,” Dr. Rutella said.

“The in silico analysis indicated that TP53-mutated cases will show higher levels of T-cell infiltration, immune checkpoints, and IFN-gamma signaling, compared with AML subgroups without risk-defining molecular lesions,” he added. “This is speculative. Whether TP53-mutated AML can be amenable to respond to T-cell targeting immunotherapies is still to be determined.”

Dr. Rutella reported research support from NanoString Technologies, MacroGenics, and Kura Oncology.

SOURCE: Rutella S et al. SITC 2019. Abstract O3.

*This article was updated on 11/19/2019.

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. – New research has shown increased immune infiltration in patients with TP53-mutated acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

Patients with TP53-mutated AML had higher levels of T-cell infiltration, immune checkpoint molecules, and interferon (IFN)–gamma signaling than patients with wild-type TP53.

These findings may indicate that patients with TP53-mutated AML will respond to T-cell targeting immunotherapies, but more investigation is needed, according to Sergio Rutella, MD, PhD, of Nottingham (England) Trent University.

Dr. Rutella described the findings at the annual meeting of the Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer.

He and his colleagues recently identified subgroups of AML, called “immune infiltrated” and “immune depleted,” that can predict chemotherapy resistance and response to flotetuzumab (ASH 2019, Abstract 460). However, the team has not determined the genetic drivers of immune infiltration in AML.*

With the current study, Dr. Rutella and his colleagues wanted to determine if TP53 mutations are associated with the AML immune milieu and see if TP53-mutated patients might benefit from immunotherapy.

Discovery cohort

The researchers first analyzed 147 patients with non-promyelocytic AML from the Cancer Genome Atlas. In total, 9% of these patients (n = 13) had TP53-mutated AML. The researchers assessed how 45 immune gene and biological activity signatures correlated with prognostic molecular lesions (TP53 mutations, FLT3-ITD, etc.) and clinical outcomes in this cohort.

The data showed that immune subtypes were associated with overall survival (OS). The median OS was 11.8 months in patients with immune-infiltrated AML, 16.4 months in patients with intermediate AML, and 25.8 months in patients with immune-depleted AML.

The inflammatory chemokine score (P = .011), IDO1 score (P = .027), IFN-gamma score (P = .036), and B7H3 score (P = .045) were all significantly associated with OS. In fact, these factors were all better predictors of OS than cytogenetic risk score (P = .049).

The IFN-gamma score, inflammatory chemokine score, and lymphoid score were all significantly higher in TP53-mutated patients than in patients with RUNX1 mutations, NPM1 mutations, FLT3-ITD (with or without NPM1 mutations), and TET2/DNMT3A/ASXL1 mutations (P values ranging from less than .0001 to .05).

Likewise, the tumor inflammation signature score was significantly higher among TP53-mutated patients than among patients with NPM1 mutations, FLT3-ITD (with or without NPM1 mutations), and TET2/DNMT3A/ASXL1 mutations (P values ranging from less than .0001 to .01).

Validation cohort and bone marrow samples

The researchers also looked at data from a validation cohort, which consisted of 140 patients with non-promyelocytic AML in the Beat AML Master Trial. Twelve percent of these patients (n = 17) had TP53 mutations.

Data in this cohort showed that CD3G messenger RNA (mRNA) was significantly higher in TP53-mutated AML than in TP53-wild-type AML (P = .04). The same was true for CD8A mRNA (P = .0002) and GZMB mRNA (P = .0005).

Likewise, IFN-gamma mRNA (P = .0052), IFIT2 mRNA (P = .0064), and IFIT3 mRNA (P = .003) were all significantly higher in patients with TP53-mutated AML.

Lastly, the researchers analyzed gene expression profiles of bone marrow samples from patients with AML, 36 with mutated TP53 and 24 with wild-type TP53.

The team found that IFN-gamma–induced genes (IFNG and IRF1), markers of T-cell infiltration (CD8A and CD3G) and senescence (EOMES, KLRD1, and HRAS), immune checkpoint molecules (IDO1, LAG3, PDL1, and VISTA), effector function molecules (GZMB, GZMK, and GZMM), and proinflammatory cytokines (IL17A and TNF) were all significantly overexpressed in TP53-mutated AML.

Among the top overexpressed genes in TP53-mutated AML were genes associated with IFN signaling and inflammation pathways – IL-33, IL-6, IFN-gamma, OASL, RIPK2, TNFAIP3, CSF1, and PTGER4. The IL-17 and TNF signaling pathways were the most enriched pathways in TP53-mutated AML.

“Our analysis of primary bone marrow samples showed that TP53-mutated samples are enriched in IL-17, TNF, and IFN signaling molecules, and show higher levels of T-cell infiltrations and immune checkpoints relative to their wild-type counterparts,” Dr. Rutella said.

“The in silico analysis indicated that TP53-mutated cases will show higher levels of T-cell infiltration, immune checkpoints, and IFN-gamma signaling, compared with AML subgroups without risk-defining molecular lesions,” he added. “This is speculative. Whether TP53-mutated AML can be amenable to respond to T-cell targeting immunotherapies is still to be determined.”

Dr. Rutella reported research support from NanoString Technologies, MacroGenics, and Kura Oncology.

SOURCE: Rutella S et al. SITC 2019. Abstract O3.

*This article was updated on 11/19/2019.

REPORTING FROM SITC 2019

TP53 double hit predicts aggressive myeloma

Relapsed multiple myeloma becomes increasingly aggressive and difficult to treat with each additional TP53 alteration, according to investigators.

Findings from the study help illuminate the mechanics of myeloma disease progression and demonstrate the value of clonal competition assays, reported lead author Umair Munawar of the University Hospital Würzburg (Germany) and colleagues.

“The implications of mono-allelic TP53 lesions for the clinical outcome remain controversial, but clonal selection and evolution is a common feature of myeloma progression, and patients with TP53 wild-type or mono-allelic inactivation may present a double hit on relapse,” the investigators wrote in Blood. “Here, we addressed the hypothesis that sequential acquisition of TP53 hits lead to a gain of proliferative fitness of [multiple myeloma] cancer cells, inducing the expansion and domination of the affected clones within the patient’s bone marrow.”

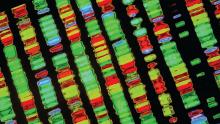

The investigators used sleeping beauty and CRISPR/Cas9 techniques to create double- and single-hit multiple myeloma cell lines that were stably transfected with fluorescent proteins. By observing coculture pairings of wild-type, single-hit, and double-hit cells, the investigators found a hierarchy of proliferation that depended on the number of TP53 alterations. For instance, when double-hit cells were cocultured with wild-type cells in a 1:3 ratio, it took 21 days for the double-hit cells to reach 50% of the total culture population. Similarly, single-hit cells outcompeted wild-type cells after 38 days, while double-hit cells took 35 days to overcome the single-hit population.

Further testing showed that comparatively smaller initial populations of TP53-aberrant cells required longer to outcompete larger wild-type populations, which could explain why deeper responses in the clinic are often followed by longer periods without disease progression, the investigators suggested.

A comparison of transcriptomes between wild-type cells and TP53 mutants revealed differences in about 900 genes, including 14 signaling pathways. Specifically, downregulation impacted antigen processing and presentation, chemokine signaling, and oxidative phosphorylation.

“These differences on the transcriptomic level well reflect the biology of ultra–high risk disease,” the investigators wrote, referring to increased glucose uptake on PET, resistance to immunotherapies, and extramedullary disease.

“[This study] underscores the power of clonal competition assays to decipher the effect of genomic lesions in tumors to better understand their impact on progression and disease relapse in [multiple myeloma],” the investigators concluded.

The study was funded by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, the CDW Stiftung, and the IZKF Würzburg. The investigators reported additional support from the CRIS foundation, the German Cancer Aid, and the University of Würzburg.

SOURCE: Munawar U et al. Blood. 2019 Jul 24. doi: 10.1182/blood.2019000080.

Relapsed multiple myeloma becomes increasingly aggressive and difficult to treat with each additional TP53 alteration, according to investigators.

Findings from the study help illuminate the mechanics of myeloma disease progression and demonstrate the value of clonal competition assays, reported lead author Umair Munawar of the University Hospital Würzburg (Germany) and colleagues.

“The implications of mono-allelic TP53 lesions for the clinical outcome remain controversial, but clonal selection and evolution is a common feature of myeloma progression, and patients with TP53 wild-type or mono-allelic inactivation may present a double hit on relapse,” the investigators wrote in Blood. “Here, we addressed the hypothesis that sequential acquisition of TP53 hits lead to a gain of proliferative fitness of [multiple myeloma] cancer cells, inducing the expansion and domination of the affected clones within the patient’s bone marrow.”

The investigators used sleeping beauty and CRISPR/Cas9 techniques to create double- and single-hit multiple myeloma cell lines that were stably transfected with fluorescent proteins. By observing coculture pairings of wild-type, single-hit, and double-hit cells, the investigators found a hierarchy of proliferation that depended on the number of TP53 alterations. For instance, when double-hit cells were cocultured with wild-type cells in a 1:3 ratio, it took 21 days for the double-hit cells to reach 50% of the total culture population. Similarly, single-hit cells outcompeted wild-type cells after 38 days, while double-hit cells took 35 days to overcome the single-hit population.

Further testing showed that comparatively smaller initial populations of TP53-aberrant cells required longer to outcompete larger wild-type populations, which could explain why deeper responses in the clinic are often followed by longer periods without disease progression, the investigators suggested.

A comparison of transcriptomes between wild-type cells and TP53 mutants revealed differences in about 900 genes, including 14 signaling pathways. Specifically, downregulation impacted antigen processing and presentation, chemokine signaling, and oxidative phosphorylation.

“These differences on the transcriptomic level well reflect the biology of ultra–high risk disease,” the investigators wrote, referring to increased glucose uptake on PET, resistance to immunotherapies, and extramedullary disease.

“[This study] underscores the power of clonal competition assays to decipher the effect of genomic lesions in tumors to better understand their impact on progression and disease relapse in [multiple myeloma],” the investigators concluded.

The study was funded by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, the CDW Stiftung, and the IZKF Würzburg. The investigators reported additional support from the CRIS foundation, the German Cancer Aid, and the University of Würzburg.

SOURCE: Munawar U et al. Blood. 2019 Jul 24. doi: 10.1182/blood.2019000080.

Relapsed multiple myeloma becomes increasingly aggressive and difficult to treat with each additional TP53 alteration, according to investigators.

Findings from the study help illuminate the mechanics of myeloma disease progression and demonstrate the value of clonal competition assays, reported lead author Umair Munawar of the University Hospital Würzburg (Germany) and colleagues.

“The implications of mono-allelic TP53 lesions for the clinical outcome remain controversial, but clonal selection and evolution is a common feature of myeloma progression, and patients with TP53 wild-type or mono-allelic inactivation may present a double hit on relapse,” the investigators wrote in Blood. “Here, we addressed the hypothesis that sequential acquisition of TP53 hits lead to a gain of proliferative fitness of [multiple myeloma] cancer cells, inducing the expansion and domination of the affected clones within the patient’s bone marrow.”

The investigators used sleeping beauty and CRISPR/Cas9 techniques to create double- and single-hit multiple myeloma cell lines that were stably transfected with fluorescent proteins. By observing coculture pairings of wild-type, single-hit, and double-hit cells, the investigators found a hierarchy of proliferation that depended on the number of TP53 alterations. For instance, when double-hit cells were cocultured with wild-type cells in a 1:3 ratio, it took 21 days for the double-hit cells to reach 50% of the total culture population. Similarly, single-hit cells outcompeted wild-type cells after 38 days, while double-hit cells took 35 days to overcome the single-hit population.

Further testing showed that comparatively smaller initial populations of TP53-aberrant cells required longer to outcompete larger wild-type populations, which could explain why deeper responses in the clinic are often followed by longer periods without disease progression, the investigators suggested.

A comparison of transcriptomes between wild-type cells and TP53 mutants revealed differences in about 900 genes, including 14 signaling pathways. Specifically, downregulation impacted antigen processing and presentation, chemokine signaling, and oxidative phosphorylation.

“These differences on the transcriptomic level well reflect the biology of ultra–high risk disease,” the investigators wrote, referring to increased glucose uptake on PET, resistance to immunotherapies, and extramedullary disease.

“[This study] underscores the power of clonal competition assays to decipher the effect of genomic lesions in tumors to better understand their impact on progression and disease relapse in [multiple myeloma],” the investigators concluded.

The study was funded by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, the CDW Stiftung, and the IZKF Würzburg. The investigators reported additional support from the CRIS foundation, the German Cancer Aid, and the University of Würzburg.

SOURCE: Munawar U et al. Blood. 2019 Jul 24. doi: 10.1182/blood.2019000080.

FROM BLOOD

BET inhibitors may target oncogene in ABC-like DLBCL

(ABC-like DLBCL).

Researchers found the TCF4 (E2-2) transcription factor is an oncogene in ABC-like DLBCL, and TCF4 can be targeted via BET inhibition.

The BET protein degrader ARV771 reduced TCF4 expression and exhibited activity against ABC-like DLBCL in vitro and in vivo.

Neeraj Jain, PhD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston and colleagues reported these findings in Science Translational Medicine.

The researchers performed a genomic analysis of 1,000 DLBCL tumors and discovered that gains of 18q21.2 were the most frequent genetic alteration in ABC-like DLBCL. In analyzing another 249 tumors, the researchers found that TCF4 was the target of the 18q21.2 gains.

Additional experiments with primary DLBCL tumors and DLBCL cell lines indicated that TCF4 regulates IGHM and MYC expression. The researchers also found that the TCF4 gene was “one of the most highly BRD4-loaded genes in DLBCL,” and knocking down BRD4 in DLBCL cell lines reduced TCF4 expression.

These findings prompted the team to test small-molecule BET inhibitors – JQ1 and OTX015 – and a BET protein degrader – ARV771 – in ABC-like DLBCL cell lines with a high TCF4 copy number.

Treatment with JQ1 and OTX015 resulted in upregulation of BRD4, but ARV771 treatment did not. As a result, subsequent experiments were performed with ARV771.

The researchers found that ARV771 induced apoptosis in the cell lines and reduced the expression of TCF4, IgM, and MYC. However, enforced TCF4 expression during ARV771 treatment rescued IgM and MYC expression. This suggests that “reduction of TCF4 is one of the mechanisms by which BET inhibition reduces IgM and MYC expression and induces apoptosis,” according to the researchers.

The team also tested ARV771 in mouse models of ABC-like DLBCL with high TCF4 expression. ARV771 significantly reduced tumor growth and prolonged survival (P less than .05 for both), and there were no signs of toxicity in ARV771-treated mice.

“Our data provide a clear functional rationale for BET inhibition in ABC-like DLBCL,” the researchers wrote. They did note, however, that BCL2 overexpression is associated with resistance to BET inhibitors, and most of the 18q DNA copy number gains the researchers observed in DLBCL encompass TCF4 and BCL2. The team therefore theorized that combining a BET inhibitor with a BCL2 inhibitor could be a promising treatment approach in ABC-like DLBCL and is worthy of further investigation.

This research was supported by the Nebraska Department of Health & Human Services, the Schweitzer Family Fund, the Fred & Pamela Buffet Cancer Center Support Grant, and the MD Anderson Cancer Center NCI CORE Grant. The authors reported having no conflicts of interest related to the study.

SOURCE: Jain N et al. Sci. Transl. Med. 2019 Jun 19. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aav5599.

(ABC-like DLBCL).

Researchers found the TCF4 (E2-2) transcription factor is an oncogene in ABC-like DLBCL, and TCF4 can be targeted via BET inhibition.

The BET protein degrader ARV771 reduced TCF4 expression and exhibited activity against ABC-like DLBCL in vitro and in vivo.

Neeraj Jain, PhD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston and colleagues reported these findings in Science Translational Medicine.

The researchers performed a genomic analysis of 1,000 DLBCL tumors and discovered that gains of 18q21.2 were the most frequent genetic alteration in ABC-like DLBCL. In analyzing another 249 tumors, the researchers found that TCF4 was the target of the 18q21.2 gains.

Additional experiments with primary DLBCL tumors and DLBCL cell lines indicated that TCF4 regulates IGHM and MYC expression. The researchers also found that the TCF4 gene was “one of the most highly BRD4-loaded genes in DLBCL,” and knocking down BRD4 in DLBCL cell lines reduced TCF4 expression.

These findings prompted the team to test small-molecule BET inhibitors – JQ1 and OTX015 – and a BET protein degrader – ARV771 – in ABC-like DLBCL cell lines with a high TCF4 copy number.

Treatment with JQ1 and OTX015 resulted in upregulation of BRD4, but ARV771 treatment did not. As a result, subsequent experiments were performed with ARV771.

The researchers found that ARV771 induced apoptosis in the cell lines and reduced the expression of TCF4, IgM, and MYC. However, enforced TCF4 expression during ARV771 treatment rescued IgM and MYC expression. This suggests that “reduction of TCF4 is one of the mechanisms by which BET inhibition reduces IgM and MYC expression and induces apoptosis,” according to the researchers.

The team also tested ARV771 in mouse models of ABC-like DLBCL with high TCF4 expression. ARV771 significantly reduced tumor growth and prolonged survival (P less than .05 for both), and there were no signs of toxicity in ARV771-treated mice.

“Our data provide a clear functional rationale for BET inhibition in ABC-like DLBCL,” the researchers wrote. They did note, however, that BCL2 overexpression is associated with resistance to BET inhibitors, and most of the 18q DNA copy number gains the researchers observed in DLBCL encompass TCF4 and BCL2. The team therefore theorized that combining a BET inhibitor with a BCL2 inhibitor could be a promising treatment approach in ABC-like DLBCL and is worthy of further investigation.

This research was supported by the Nebraska Department of Health & Human Services, the Schweitzer Family Fund, the Fred & Pamela Buffet Cancer Center Support Grant, and the MD Anderson Cancer Center NCI CORE Grant. The authors reported having no conflicts of interest related to the study.

SOURCE: Jain N et al. Sci. Transl. Med. 2019 Jun 19. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aav5599.

(ABC-like DLBCL).

Researchers found the TCF4 (E2-2) transcription factor is an oncogene in ABC-like DLBCL, and TCF4 can be targeted via BET inhibition.

The BET protein degrader ARV771 reduced TCF4 expression and exhibited activity against ABC-like DLBCL in vitro and in vivo.

Neeraj Jain, PhD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston and colleagues reported these findings in Science Translational Medicine.

The researchers performed a genomic analysis of 1,000 DLBCL tumors and discovered that gains of 18q21.2 were the most frequent genetic alteration in ABC-like DLBCL. In analyzing another 249 tumors, the researchers found that TCF4 was the target of the 18q21.2 gains.

Additional experiments with primary DLBCL tumors and DLBCL cell lines indicated that TCF4 regulates IGHM and MYC expression. The researchers also found that the TCF4 gene was “one of the most highly BRD4-loaded genes in DLBCL,” and knocking down BRD4 in DLBCL cell lines reduced TCF4 expression.

These findings prompted the team to test small-molecule BET inhibitors – JQ1 and OTX015 – and a BET protein degrader – ARV771 – in ABC-like DLBCL cell lines with a high TCF4 copy number.

Treatment with JQ1 and OTX015 resulted in upregulation of BRD4, but ARV771 treatment did not. As a result, subsequent experiments were performed with ARV771.

The researchers found that ARV771 induced apoptosis in the cell lines and reduced the expression of TCF4, IgM, and MYC. However, enforced TCF4 expression during ARV771 treatment rescued IgM and MYC expression. This suggests that “reduction of TCF4 is one of the mechanisms by which BET inhibition reduces IgM and MYC expression and induces apoptosis,” according to the researchers.

The team also tested ARV771 in mouse models of ABC-like DLBCL with high TCF4 expression. ARV771 significantly reduced tumor growth and prolonged survival (P less than .05 for both), and there were no signs of toxicity in ARV771-treated mice.