User login

Eosinophilic esophagitis: A year in review

At the AGA postgraduate course in May, we highlighted recent noteworthy randomized controlled trials (RCT) using eosinophil-targeting biologic therapy, esophageal-optimized corticosteroid preparations, and dietary elimination in EoE.

Dupilumab, a monoclonal antibody that blocks interleukin-4 and IL-13 signaling, was tested in a phase 3 trial for adults and adolescents with EoE.1 In this double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial, the efficacy of subcutaneous dupilumab 300 mg weekly or every other week was compared against placebo. Stringent histologic remission (≤ 6 eosinophils/high power field) occurred in approximately 60% who received dupilumab (either dose) versus 5% in placebo. However, significant symptom improvement was seen only with 300 g weekly dupilumab.

On the topical corticosteroid front, the results of two RCTs using fluticasone orally disintegrating tablet (APT-1011) and budesonide oral suspension (BOS) were published. In the APT-1011 phase 2b trial, patients were randomized to receive 1.5 mg or 3 mg daily or b.i.d. versus placebo for 12 weeks.2 High histologic response rates and improvement in dysphagia frequency were seen with all ≥ 3-mg daily-dose APT-1011, compared with placebo. However, adverse events (that is, candidiasis) were highest among those on 3 mg b.i.d. Thus, 3 mg daily APT-1011 was thought to offer the most favorable risk-benefit profile. In the BOS phase 3 trial, patients were randomized 2:1 to received BOS 2 mg b.i.d. or placebo for 12 weeks.3 BOS was superior to placebo in histologic, symptomatic, and endoscopic outcomes.

Diet remains the only therapy targeting the cause of EoE and offers a potential drug-free remission. In the randomized, open label trial of 1- versus 6-food elimination diet, adult patients were allocated 1:1 to 1FED (animal milk) or 6FED (animal milk, wheat, egg, soy, fish/shellfish, and peanuts/tree nuts) for 6 weeks.4 No significant difference in partial or stringent remission was found between the two groups. Step-up therapy resulted in an additional 43% histologic response in those who underwent 6FED after failing 1FED and 82% histologic response in those who received swallowed fluticasone 880 mcg b.i.d after failing 6FED. Hence, eliminating animal milk alone in a step-up treatment approach is reasonable.

We have witnessed major progress to expand EoE treatment options in the last year. Long-term efficacy and side-effect data, as well as studies comparing between therapies are needed to improve shared decision-making and strategies to implement tailored care in EoE.

Dr. Chen is with the division of gastroenterology and hepatology, department of internal medicine at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. She disclosed consultancy work with Phathom Pharmaceuticals.

References

1. Dellon ES et al. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(25):2317-30.

2. Dellon ES et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(11):2485-94e15.

3. Hirano I et al. Budesonide. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(3):525-34e10.

4. Kliewer KL et al. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;8(5):408-21.

At the AGA postgraduate course in May, we highlighted recent noteworthy randomized controlled trials (RCT) using eosinophil-targeting biologic therapy, esophageal-optimized corticosteroid preparations, and dietary elimination in EoE.

Dupilumab, a monoclonal antibody that blocks interleukin-4 and IL-13 signaling, was tested in a phase 3 trial for adults and adolescents with EoE.1 In this double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial, the efficacy of subcutaneous dupilumab 300 mg weekly or every other week was compared against placebo. Stringent histologic remission (≤ 6 eosinophils/high power field) occurred in approximately 60% who received dupilumab (either dose) versus 5% in placebo. However, significant symptom improvement was seen only with 300 g weekly dupilumab.

On the topical corticosteroid front, the results of two RCTs using fluticasone orally disintegrating tablet (APT-1011) and budesonide oral suspension (BOS) were published. In the APT-1011 phase 2b trial, patients were randomized to receive 1.5 mg or 3 mg daily or b.i.d. versus placebo for 12 weeks.2 High histologic response rates and improvement in dysphagia frequency were seen with all ≥ 3-mg daily-dose APT-1011, compared with placebo. However, adverse events (that is, candidiasis) were highest among those on 3 mg b.i.d. Thus, 3 mg daily APT-1011 was thought to offer the most favorable risk-benefit profile. In the BOS phase 3 trial, patients were randomized 2:1 to received BOS 2 mg b.i.d. or placebo for 12 weeks.3 BOS was superior to placebo in histologic, symptomatic, and endoscopic outcomes.

Diet remains the only therapy targeting the cause of EoE and offers a potential drug-free remission. In the randomized, open label trial of 1- versus 6-food elimination diet, adult patients were allocated 1:1 to 1FED (animal milk) or 6FED (animal milk, wheat, egg, soy, fish/shellfish, and peanuts/tree nuts) for 6 weeks.4 No significant difference in partial or stringent remission was found between the two groups. Step-up therapy resulted in an additional 43% histologic response in those who underwent 6FED after failing 1FED and 82% histologic response in those who received swallowed fluticasone 880 mcg b.i.d after failing 6FED. Hence, eliminating animal milk alone in a step-up treatment approach is reasonable.

We have witnessed major progress to expand EoE treatment options in the last year. Long-term efficacy and side-effect data, as well as studies comparing between therapies are needed to improve shared decision-making and strategies to implement tailored care in EoE.

Dr. Chen is with the division of gastroenterology and hepatology, department of internal medicine at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. She disclosed consultancy work with Phathom Pharmaceuticals.

References

1. Dellon ES et al. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(25):2317-30.

2. Dellon ES et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(11):2485-94e15.

3. Hirano I et al. Budesonide. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(3):525-34e10.

4. Kliewer KL et al. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;8(5):408-21.

At the AGA postgraduate course in May, we highlighted recent noteworthy randomized controlled trials (RCT) using eosinophil-targeting biologic therapy, esophageal-optimized corticosteroid preparations, and dietary elimination in EoE.

Dupilumab, a monoclonal antibody that blocks interleukin-4 and IL-13 signaling, was tested in a phase 3 trial for adults and adolescents with EoE.1 In this double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial, the efficacy of subcutaneous dupilumab 300 mg weekly or every other week was compared against placebo. Stringent histologic remission (≤ 6 eosinophils/high power field) occurred in approximately 60% who received dupilumab (either dose) versus 5% in placebo. However, significant symptom improvement was seen only with 300 g weekly dupilumab.

On the topical corticosteroid front, the results of two RCTs using fluticasone orally disintegrating tablet (APT-1011) and budesonide oral suspension (BOS) were published. In the APT-1011 phase 2b trial, patients were randomized to receive 1.5 mg or 3 mg daily or b.i.d. versus placebo for 12 weeks.2 High histologic response rates and improvement in dysphagia frequency were seen with all ≥ 3-mg daily-dose APT-1011, compared with placebo. However, adverse events (that is, candidiasis) were highest among those on 3 mg b.i.d. Thus, 3 mg daily APT-1011 was thought to offer the most favorable risk-benefit profile. In the BOS phase 3 trial, patients were randomized 2:1 to received BOS 2 mg b.i.d. or placebo for 12 weeks.3 BOS was superior to placebo in histologic, symptomatic, and endoscopic outcomes.

Diet remains the only therapy targeting the cause of EoE and offers a potential drug-free remission. In the randomized, open label trial of 1- versus 6-food elimination diet, adult patients were allocated 1:1 to 1FED (animal milk) or 6FED (animal milk, wheat, egg, soy, fish/shellfish, and peanuts/tree nuts) for 6 weeks.4 No significant difference in partial or stringent remission was found between the two groups. Step-up therapy resulted in an additional 43% histologic response in those who underwent 6FED after failing 1FED and 82% histologic response in those who received swallowed fluticasone 880 mcg b.i.d after failing 6FED. Hence, eliminating animal milk alone in a step-up treatment approach is reasonable.

We have witnessed major progress to expand EoE treatment options in the last year. Long-term efficacy and side-effect data, as well as studies comparing between therapies are needed to improve shared decision-making and strategies to implement tailored care in EoE.

Dr. Chen is with the division of gastroenterology and hepatology, department of internal medicine at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. She disclosed consultancy work with Phathom Pharmaceuticals.

References

1. Dellon ES et al. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(25):2317-30.

2. Dellon ES et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(11):2485-94e15.

3. Hirano I et al. Budesonide. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(3):525-34e10.

4. Kliewer KL et al. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;8(5):408-21.

Esophageal diseases: Key new concepts

CHICAGO – These include novel care approaches for esophageal diseases that were published in recent AGA best practice updates on gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), extraesophageal reflux, and Barrett’s esophagus, as well as randomized clinical trial data examining therapeutic approaches for erosive esophagitis and eosinophilic esophagitis.

Here are a few highlights: Complications of chronic gastroesophageal reflux include erosive esophagitis for which healing and maintenance of healing is crucial to reduce further erosive sequelae. Healing is typically achieved with pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy. Potassium competitive acid blockers are active prodrugs that bind to the H+/K+ ATPase and have been demonstrated to have a more potent and faster onset in suppressing gastric acid secretion, compared with PPIs.

In a recent phase 3 randomized trial of more than 1,000 adults with erosive esophagitis, the potassium competitive acid blocker vonoprazan was found to be noninferior to lansoprazole in inducing and maintaining healing of erosive esophagitis. Overall, the proportions of subjects that achieved healing by week 8 and maintained healing up to 24 weeks were higher with vonoprazan, when compared with lansoprazole, with a greater treatment effect seen in subjects with severe erosive esophagitis (Los Angeles grade C or D) (Laine L et al. Gastroenterology. Jan 2023;164[1]:61-71).

Screening patients at risk of Barrett’s esophagus (BE), another erosive sequelae of chronic GERD, is critical for early detection and prevention of esophageal cancer. Upper GI endoscopy is standard for Barrett’s screening; however, screening rates of at-risk populations are suboptimal.

In a recent retrospective analysis of a multipractice health care network, only 39% of a screen-eligible population were noted to have undergone upper GI endoscopy. These findings highlight the critical need to improve screening for Barrett’s, including potential of the newer nonendoscopic screening modalities such as swallowable capsule devices combined with a biomarker or cell-collection devices, as well as the need for risk stratification/prediction tools and collaboration with primary care physicians (Eluri S et al. Am J Gastroenterol. Nov 2022;117[11]:1764-71).

Therapeutic options for eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) have expanded over the past year. Randomized trials demonstrate the efficacy of varied therapeutic approaches including the monoclonal antibody dupilumab as well as topical corticosteroids such as fluticasone propionate orally disintegrated tablet and budesonide oral suspension.

In terms of food elimination diets, a recent multicenter randomized open-label trial identified comparable rates of partial histologic remission with both a traditional six-food elimination diet and a one-food animal milk elimination diet in patients with EoE, though those treated with a six-food elimination were more likely to achieve complete remission (< 1 eosinophil/high power field). Results suggest elimination of animal milk alone is an acceptable initial dietary therapy for EoE, with potential to convert to six-food elimination or alternative therapy when histologic response is not achieved (Kliewer K. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. [published online Feb 2023]).

Dr. Yadlapati is an associate professor in gastroenterology at the University of California, San Diego. She disclosed relationships with Medtronic (Institutional), Ironwood Pharmaceuticals (Institutional), Phathom Pharmaceuticals, and Ironwood Pharmaceuticals. She serves on the advisory board with stock options for RJS Mediagnostix.

These remarks were made during one of the AGA Postgraduate Course sessions held at DDW 2023.

DDW is sponsored by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD), the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA), the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) and The Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract (SSAT).

CHICAGO – These include novel care approaches for esophageal diseases that were published in recent AGA best practice updates on gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), extraesophageal reflux, and Barrett’s esophagus, as well as randomized clinical trial data examining therapeutic approaches for erosive esophagitis and eosinophilic esophagitis.

Here are a few highlights: Complications of chronic gastroesophageal reflux include erosive esophagitis for which healing and maintenance of healing is crucial to reduce further erosive sequelae. Healing is typically achieved with pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy. Potassium competitive acid blockers are active prodrugs that bind to the H+/K+ ATPase and have been demonstrated to have a more potent and faster onset in suppressing gastric acid secretion, compared with PPIs.

In a recent phase 3 randomized trial of more than 1,000 adults with erosive esophagitis, the potassium competitive acid blocker vonoprazan was found to be noninferior to lansoprazole in inducing and maintaining healing of erosive esophagitis. Overall, the proportions of subjects that achieved healing by week 8 and maintained healing up to 24 weeks were higher with vonoprazan, when compared with lansoprazole, with a greater treatment effect seen in subjects with severe erosive esophagitis (Los Angeles grade C or D) (Laine L et al. Gastroenterology. Jan 2023;164[1]:61-71).

Screening patients at risk of Barrett’s esophagus (BE), another erosive sequelae of chronic GERD, is critical for early detection and prevention of esophageal cancer. Upper GI endoscopy is standard for Barrett’s screening; however, screening rates of at-risk populations are suboptimal.

In a recent retrospective analysis of a multipractice health care network, only 39% of a screen-eligible population were noted to have undergone upper GI endoscopy. These findings highlight the critical need to improve screening for Barrett’s, including potential of the newer nonendoscopic screening modalities such as swallowable capsule devices combined with a biomarker or cell-collection devices, as well as the need for risk stratification/prediction tools and collaboration with primary care physicians (Eluri S et al. Am J Gastroenterol. Nov 2022;117[11]:1764-71).

Therapeutic options for eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) have expanded over the past year. Randomized trials demonstrate the efficacy of varied therapeutic approaches including the monoclonal antibody dupilumab as well as topical corticosteroids such as fluticasone propionate orally disintegrated tablet and budesonide oral suspension.

In terms of food elimination diets, a recent multicenter randomized open-label trial identified comparable rates of partial histologic remission with both a traditional six-food elimination diet and a one-food animal milk elimination diet in patients with EoE, though those treated with a six-food elimination were more likely to achieve complete remission (< 1 eosinophil/high power field). Results suggest elimination of animal milk alone is an acceptable initial dietary therapy for EoE, with potential to convert to six-food elimination or alternative therapy when histologic response is not achieved (Kliewer K. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. [published online Feb 2023]).

Dr. Yadlapati is an associate professor in gastroenterology at the University of California, San Diego. She disclosed relationships with Medtronic (Institutional), Ironwood Pharmaceuticals (Institutional), Phathom Pharmaceuticals, and Ironwood Pharmaceuticals. She serves on the advisory board with stock options for RJS Mediagnostix.

These remarks were made during one of the AGA Postgraduate Course sessions held at DDW 2023.

DDW is sponsored by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD), the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA), the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) and The Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract (SSAT).

CHICAGO – These include novel care approaches for esophageal diseases that were published in recent AGA best practice updates on gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), extraesophageal reflux, and Barrett’s esophagus, as well as randomized clinical trial data examining therapeutic approaches for erosive esophagitis and eosinophilic esophagitis.

Here are a few highlights: Complications of chronic gastroesophageal reflux include erosive esophagitis for which healing and maintenance of healing is crucial to reduce further erosive sequelae. Healing is typically achieved with pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy. Potassium competitive acid blockers are active prodrugs that bind to the H+/K+ ATPase and have been demonstrated to have a more potent and faster onset in suppressing gastric acid secretion, compared with PPIs.

In a recent phase 3 randomized trial of more than 1,000 adults with erosive esophagitis, the potassium competitive acid blocker vonoprazan was found to be noninferior to lansoprazole in inducing and maintaining healing of erosive esophagitis. Overall, the proportions of subjects that achieved healing by week 8 and maintained healing up to 24 weeks were higher with vonoprazan, when compared with lansoprazole, with a greater treatment effect seen in subjects with severe erosive esophagitis (Los Angeles grade C or D) (Laine L et al. Gastroenterology. Jan 2023;164[1]:61-71).

Screening patients at risk of Barrett’s esophagus (BE), another erosive sequelae of chronic GERD, is critical for early detection and prevention of esophageal cancer. Upper GI endoscopy is standard for Barrett’s screening; however, screening rates of at-risk populations are suboptimal.

In a recent retrospective analysis of a multipractice health care network, only 39% of a screen-eligible population were noted to have undergone upper GI endoscopy. These findings highlight the critical need to improve screening for Barrett’s, including potential of the newer nonendoscopic screening modalities such as swallowable capsule devices combined with a biomarker or cell-collection devices, as well as the need for risk stratification/prediction tools and collaboration with primary care physicians (Eluri S et al. Am J Gastroenterol. Nov 2022;117[11]:1764-71).

Therapeutic options for eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) have expanded over the past year. Randomized trials demonstrate the efficacy of varied therapeutic approaches including the monoclonal antibody dupilumab as well as topical corticosteroids such as fluticasone propionate orally disintegrated tablet and budesonide oral suspension.

In terms of food elimination diets, a recent multicenter randomized open-label trial identified comparable rates of partial histologic remission with both a traditional six-food elimination diet and a one-food animal milk elimination diet in patients with EoE, though those treated with a six-food elimination were more likely to achieve complete remission (< 1 eosinophil/high power field). Results suggest elimination of animal milk alone is an acceptable initial dietary therapy for EoE, with potential to convert to six-food elimination or alternative therapy when histologic response is not achieved (Kliewer K. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. [published online Feb 2023]).

Dr. Yadlapati is an associate professor in gastroenterology at the University of California, San Diego. She disclosed relationships with Medtronic (Institutional), Ironwood Pharmaceuticals (Institutional), Phathom Pharmaceuticals, and Ironwood Pharmaceuticals. She serves on the advisory board with stock options for RJS Mediagnostix.

These remarks were made during one of the AGA Postgraduate Course sessions held at DDW 2023.

DDW is sponsored by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD), the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA), the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) and The Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract (SSAT).

AT DDW 2023

AGA clinical practice update: Extraesophageal gastroesophageal reflux disease

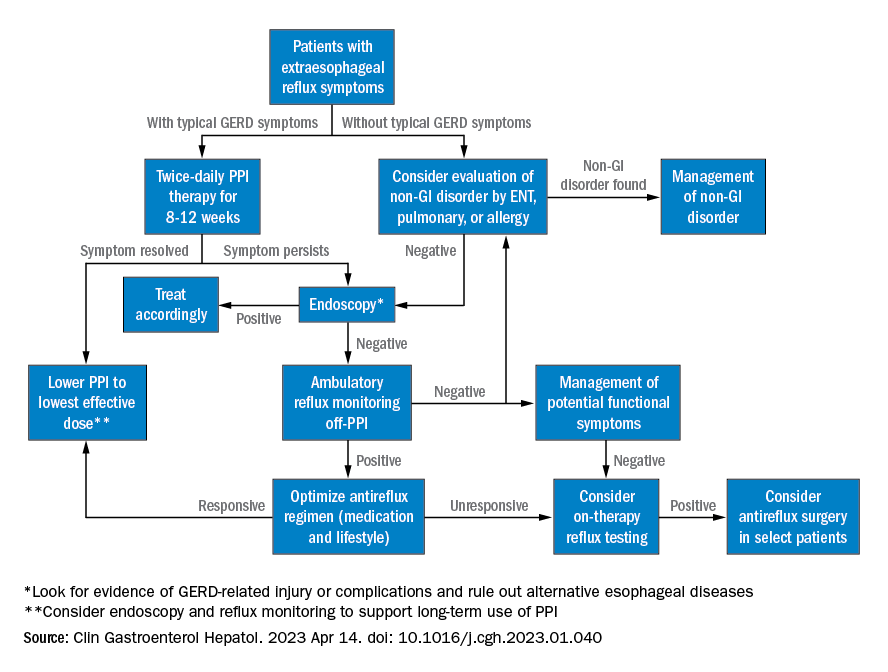

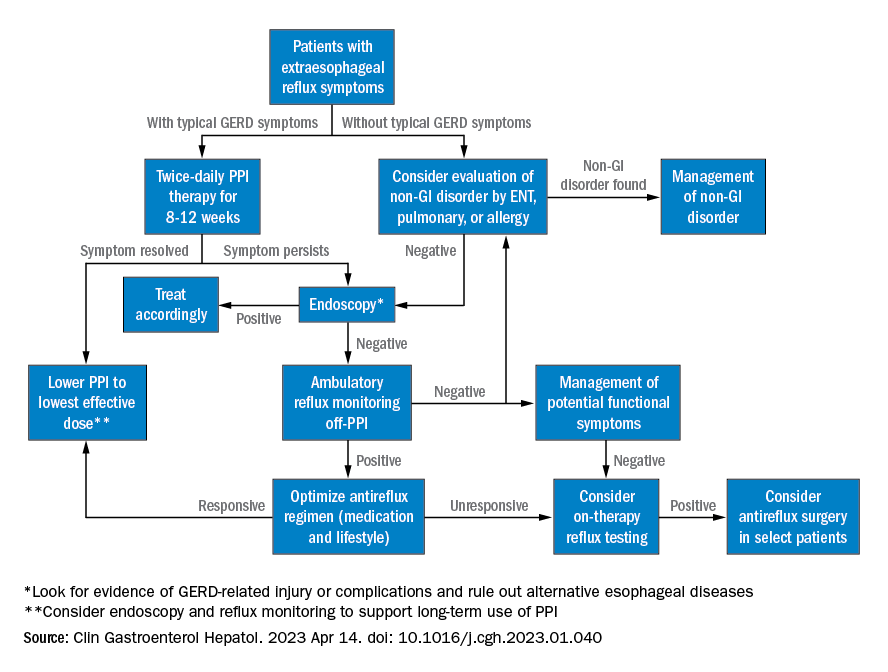

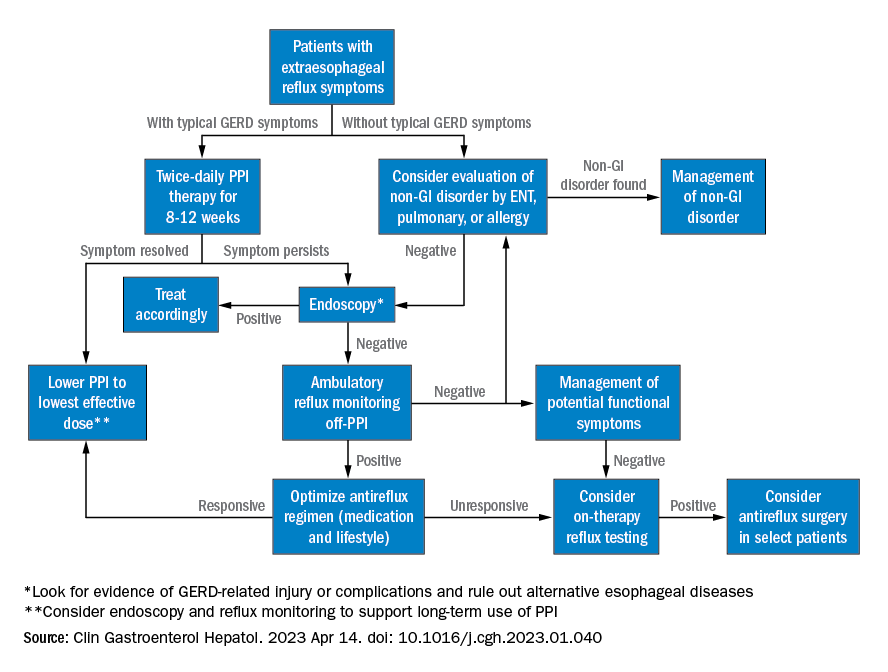

Extraesophageal reflux (EER) symptoms are a subset of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) that can be difficult to diagnose because of its heterogeneous nature and symptoms that overlap with other conditions.

That puts the onus on physicians to take all symptoms into account and work across disciplines to diagnose, manage, and treat the condition, according to a new clinical practice update from the American Gastroenterological Association, which was published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

GERD is becoming increasingly common, which in turn has led to greater awareness and consideration of EER symptoms. EER symptoms can present a challenge because they may vary considerably and are not unique to GERD. The symptoms often do not respond well to proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy.

EER symptoms can include cough, laryngeal hoarseness, dysphonia, pulmonary fibrosis, asthma, dental erosions/caries, sinus disease, ear disease, postnasal drip, and throat clearing. Some patients with EER symptoms do not report heartburn or regurgitation, which leaves it up to the physician to determine if acid reflux is present and contributing to symptoms.

“The concept of extraesophageal symptoms secondary to GERD is complex and often controversial, leading to diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. Several extraesophageal symptoms have been associated with GERD, although the strength of evidence to support a causal relation varies,” wrote the authors, who were led by Joan W. Chen, MD, MS, a gastroenterologist with the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

There is also debate over whether fluid refluxate is the source of damage that causes EER symptoms, and if so, whether it is sufficient that the fluid be acidic or that pepsin be present, or if the cause is related to neurogenic signaling and resulting inflammation. Because of these questions, a PPI trial will not necessarily provide insight into the role of acid reflux in EER symptoms.

Best practice advice 1: The authors emphasized that gastroenterologists need to be aware of the potential extraesophageal symptoms of GERD. They should inquire with GERD patients to determine if laryngitis, chronic cough, asthma, and dental erosions are present.

Best practice advice 2: Consider a multidisciplinary approach to EER manifestations. Cases may require input from non-GI specialties. Tests performed by other specialists, such as bronchoscopy, thoracic imaging, or laryngoscopy, should be taken into account, since patients will also seek out multiple specialists to address their symptoms.

Best practice advice 3: There is no specific diagnostic test available to determine if GER is the cause of EER symptoms. Instead, physicians should interpret patient symptoms, response to GER therapy, and input from endoscopy and reflux tests.

Best practice advice 4: Rather than subject the patient to the cost and potential for even rare adverse events of a PPI trial, physicians should first consider conducting reflux testing. A PPI trial has clinical value but is insufficient on its own to help diagnose or manage EER. Initial single-dose PPI trial, titrating up to twice daily in those with typical GERD symptoms, is reasonable.

Best practice advice 5: The inconsistent therapeutic response to PPI therapy means that positive effects of PPI therapy on EER symptoms can’t confirm a GERD diagnosis because a placebo effect may be involved, and because symptom improvement can occur through mechanisms other than acid suppression. A meta-analysis found that a PPI trial has a sensitivity of 71%-78% and a specificity of 41%-54% with typical symptoms of heartburn and regurgitation. “Considering the greater variation expected with PPI response for extraesophageal symptoms, the diagnostic performance of empiric PPI trial for a diagnosis of EER would be anticipated to be substantially lower,” the authors wrote.

Best practice advice 6: When EER symptoms related to GERD are suspected and a PPI trial of up to 12 weeks does not lead to adequate improvement, the physician should consider testing for pathologic GER. Additional trials employing other PPIs are unlikely to succeed.

Best practice advice 7: Initial testing to evaluate for reflux should be tailored to patients’ clinical presentation. Potential methods to evaluate reflux include upper endoscopy and ambulatory reflux monitoring studies of acid suppressive therapy, which can assist with a GERD diagnosis, particularly when nonerosive reflux is present.

Best practice advice 8: About 50%-60% of patients with EER symptoms will not have GERD. Testing can be considered for those with an established objective diagnosis of GERD who do not respond well to high doses of acid suppression. Cost-effectiveness studies have confirmed the value of starting with ambulatory reflux monitoring, which can include a catheter-based pH sensor, pH impedance, or wireless pH capsule.

Ambulatory esophageal pH monitoring can also assist in making a GERD diagnosis, but it does not indicate whether GERD may be contributing to EER symptoms.

“Whichever the reflux testing modality, the strongest confidence for EER is achieved after ambulatory reflux testing showing pathologic acid exposure and a positive symptom-reflux association for EER symptoms,” the authors wrote. They also pointed out that ambulatory reflux monitoring in EER patients should be done in the absence of acid suppression unless there is already objective evidence for the presence of GERD.

Best practice advice 9: Aside from acid suppression, EER symptoms can also be managed through other means, including lifestyle modifications, such as eating avoidance prior to lying down, elevation of the head of the bed, sleeping on the left side, and weight loss. Or, alginate containing antacids, external upper esophageal sphincter compression device, cognitive behavioral therapy, and neuromodulators.

Best practice advice 10: In cases where the EER patient has objectively defined evidence of GERD, physicians should employ shared decision-making before considering anti-reflux surgery. If the patient did not respond to PPI therapy, this predicts a lack of response to antireflux surgery.

All four authors reported financial ties to multiple pharmaceutical companies.

Extraesophageal reflux (EER) symptoms are a subset of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) that can be difficult to diagnose because of its heterogeneous nature and symptoms that overlap with other conditions.

That puts the onus on physicians to take all symptoms into account and work across disciplines to diagnose, manage, and treat the condition, according to a new clinical practice update from the American Gastroenterological Association, which was published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

GERD is becoming increasingly common, which in turn has led to greater awareness and consideration of EER symptoms. EER symptoms can present a challenge because they may vary considerably and are not unique to GERD. The symptoms often do not respond well to proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy.

EER symptoms can include cough, laryngeal hoarseness, dysphonia, pulmonary fibrosis, asthma, dental erosions/caries, sinus disease, ear disease, postnasal drip, and throat clearing. Some patients with EER symptoms do not report heartburn or regurgitation, which leaves it up to the physician to determine if acid reflux is present and contributing to symptoms.

“The concept of extraesophageal symptoms secondary to GERD is complex and often controversial, leading to diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. Several extraesophageal symptoms have been associated with GERD, although the strength of evidence to support a causal relation varies,” wrote the authors, who were led by Joan W. Chen, MD, MS, a gastroenterologist with the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

There is also debate over whether fluid refluxate is the source of damage that causes EER symptoms, and if so, whether it is sufficient that the fluid be acidic or that pepsin be present, or if the cause is related to neurogenic signaling and resulting inflammation. Because of these questions, a PPI trial will not necessarily provide insight into the role of acid reflux in EER symptoms.

Best practice advice 1: The authors emphasized that gastroenterologists need to be aware of the potential extraesophageal symptoms of GERD. They should inquire with GERD patients to determine if laryngitis, chronic cough, asthma, and dental erosions are present.

Best practice advice 2: Consider a multidisciplinary approach to EER manifestations. Cases may require input from non-GI specialties. Tests performed by other specialists, such as bronchoscopy, thoracic imaging, or laryngoscopy, should be taken into account, since patients will also seek out multiple specialists to address their symptoms.

Best practice advice 3: There is no specific diagnostic test available to determine if GER is the cause of EER symptoms. Instead, physicians should interpret patient symptoms, response to GER therapy, and input from endoscopy and reflux tests.

Best practice advice 4: Rather than subject the patient to the cost and potential for even rare adverse events of a PPI trial, physicians should first consider conducting reflux testing. A PPI trial has clinical value but is insufficient on its own to help diagnose or manage EER. Initial single-dose PPI trial, titrating up to twice daily in those with typical GERD symptoms, is reasonable.

Best practice advice 5: The inconsistent therapeutic response to PPI therapy means that positive effects of PPI therapy on EER symptoms can’t confirm a GERD diagnosis because a placebo effect may be involved, and because symptom improvement can occur through mechanisms other than acid suppression. A meta-analysis found that a PPI trial has a sensitivity of 71%-78% and a specificity of 41%-54% with typical symptoms of heartburn and regurgitation. “Considering the greater variation expected with PPI response for extraesophageal symptoms, the diagnostic performance of empiric PPI trial for a diagnosis of EER would be anticipated to be substantially lower,” the authors wrote.

Best practice advice 6: When EER symptoms related to GERD are suspected and a PPI trial of up to 12 weeks does not lead to adequate improvement, the physician should consider testing for pathologic GER. Additional trials employing other PPIs are unlikely to succeed.

Best practice advice 7: Initial testing to evaluate for reflux should be tailored to patients’ clinical presentation. Potential methods to evaluate reflux include upper endoscopy and ambulatory reflux monitoring studies of acid suppressive therapy, which can assist with a GERD diagnosis, particularly when nonerosive reflux is present.

Best practice advice 8: About 50%-60% of patients with EER symptoms will not have GERD. Testing can be considered for those with an established objective diagnosis of GERD who do not respond well to high doses of acid suppression. Cost-effectiveness studies have confirmed the value of starting with ambulatory reflux monitoring, which can include a catheter-based pH sensor, pH impedance, or wireless pH capsule.

Ambulatory esophageal pH monitoring can also assist in making a GERD diagnosis, but it does not indicate whether GERD may be contributing to EER symptoms.

“Whichever the reflux testing modality, the strongest confidence for EER is achieved after ambulatory reflux testing showing pathologic acid exposure and a positive symptom-reflux association for EER symptoms,” the authors wrote. They also pointed out that ambulatory reflux monitoring in EER patients should be done in the absence of acid suppression unless there is already objective evidence for the presence of GERD.

Best practice advice 9: Aside from acid suppression, EER symptoms can also be managed through other means, including lifestyle modifications, such as eating avoidance prior to lying down, elevation of the head of the bed, sleeping on the left side, and weight loss. Or, alginate containing antacids, external upper esophageal sphincter compression device, cognitive behavioral therapy, and neuromodulators.

Best practice advice 10: In cases where the EER patient has objectively defined evidence of GERD, physicians should employ shared decision-making before considering anti-reflux surgery. If the patient did not respond to PPI therapy, this predicts a lack of response to antireflux surgery.

All four authors reported financial ties to multiple pharmaceutical companies.

Extraesophageal reflux (EER) symptoms are a subset of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) that can be difficult to diagnose because of its heterogeneous nature and symptoms that overlap with other conditions.

That puts the onus on physicians to take all symptoms into account and work across disciplines to diagnose, manage, and treat the condition, according to a new clinical practice update from the American Gastroenterological Association, which was published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

GERD is becoming increasingly common, which in turn has led to greater awareness and consideration of EER symptoms. EER symptoms can present a challenge because they may vary considerably and are not unique to GERD. The symptoms often do not respond well to proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy.

EER symptoms can include cough, laryngeal hoarseness, dysphonia, pulmonary fibrosis, asthma, dental erosions/caries, sinus disease, ear disease, postnasal drip, and throat clearing. Some patients with EER symptoms do not report heartburn or regurgitation, which leaves it up to the physician to determine if acid reflux is present and contributing to symptoms.

“The concept of extraesophageal symptoms secondary to GERD is complex and often controversial, leading to diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. Several extraesophageal symptoms have been associated with GERD, although the strength of evidence to support a causal relation varies,” wrote the authors, who were led by Joan W. Chen, MD, MS, a gastroenterologist with the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

There is also debate over whether fluid refluxate is the source of damage that causes EER symptoms, and if so, whether it is sufficient that the fluid be acidic or that pepsin be present, or if the cause is related to neurogenic signaling and resulting inflammation. Because of these questions, a PPI trial will not necessarily provide insight into the role of acid reflux in EER symptoms.

Best practice advice 1: The authors emphasized that gastroenterologists need to be aware of the potential extraesophageal symptoms of GERD. They should inquire with GERD patients to determine if laryngitis, chronic cough, asthma, and dental erosions are present.

Best practice advice 2: Consider a multidisciplinary approach to EER manifestations. Cases may require input from non-GI specialties. Tests performed by other specialists, such as bronchoscopy, thoracic imaging, or laryngoscopy, should be taken into account, since patients will also seek out multiple specialists to address their symptoms.

Best practice advice 3: There is no specific diagnostic test available to determine if GER is the cause of EER symptoms. Instead, physicians should interpret patient symptoms, response to GER therapy, and input from endoscopy and reflux tests.

Best practice advice 4: Rather than subject the patient to the cost and potential for even rare adverse events of a PPI trial, physicians should first consider conducting reflux testing. A PPI trial has clinical value but is insufficient on its own to help diagnose or manage EER. Initial single-dose PPI trial, titrating up to twice daily in those with typical GERD symptoms, is reasonable.

Best practice advice 5: The inconsistent therapeutic response to PPI therapy means that positive effects of PPI therapy on EER symptoms can’t confirm a GERD diagnosis because a placebo effect may be involved, and because symptom improvement can occur through mechanisms other than acid suppression. A meta-analysis found that a PPI trial has a sensitivity of 71%-78% and a specificity of 41%-54% with typical symptoms of heartburn and regurgitation. “Considering the greater variation expected with PPI response for extraesophageal symptoms, the diagnostic performance of empiric PPI trial for a diagnosis of EER would be anticipated to be substantially lower,” the authors wrote.

Best practice advice 6: When EER symptoms related to GERD are suspected and a PPI trial of up to 12 weeks does not lead to adequate improvement, the physician should consider testing for pathologic GER. Additional trials employing other PPIs are unlikely to succeed.

Best practice advice 7: Initial testing to evaluate for reflux should be tailored to patients’ clinical presentation. Potential methods to evaluate reflux include upper endoscopy and ambulatory reflux monitoring studies of acid suppressive therapy, which can assist with a GERD diagnosis, particularly when nonerosive reflux is present.

Best practice advice 8: About 50%-60% of patients with EER symptoms will not have GERD. Testing can be considered for those with an established objective diagnosis of GERD who do not respond well to high doses of acid suppression. Cost-effectiveness studies have confirmed the value of starting with ambulatory reflux monitoring, which can include a catheter-based pH sensor, pH impedance, or wireless pH capsule.

Ambulatory esophageal pH monitoring can also assist in making a GERD diagnosis, but it does not indicate whether GERD may be contributing to EER symptoms.

“Whichever the reflux testing modality, the strongest confidence for EER is achieved after ambulatory reflux testing showing pathologic acid exposure and a positive symptom-reflux association for EER symptoms,” the authors wrote. They also pointed out that ambulatory reflux monitoring in EER patients should be done in the absence of acid suppression unless there is already objective evidence for the presence of GERD.

Best practice advice 9: Aside from acid suppression, EER symptoms can also be managed through other means, including lifestyle modifications, such as eating avoidance prior to lying down, elevation of the head of the bed, sleeping on the left side, and weight loss. Or, alginate containing antacids, external upper esophageal sphincter compression device, cognitive behavioral therapy, and neuromodulators.

Best practice advice 10: In cases where the EER patient has objectively defined evidence of GERD, physicians should employ shared decision-making before considering anti-reflux surgery. If the patient did not respond to PPI therapy, this predicts a lack of response to antireflux surgery.

All four authors reported financial ties to multiple pharmaceutical companies.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Approach to dysphagia

Introduction

Dysphagia is the sensation of difficulty swallowing food or liquid in the acute or chronic setting. The prevalence of dysphagia ranges based on the type and etiology but may impact up to one in six adults.1,2 Dysphagia can cause a significant impact on a patient’s health and overall quality of life. A recent study found that only 50% of symptomatic adults seek medical care despite modifying their eating habits by either eating slowly or changing to softer foods or liquids.1 The most common, serious complications of dysphagia include aspiration pneumonia, malnutrition, and dehydration.3 According to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, dysphagia may be responsible for up to 60,000 deaths annually.3

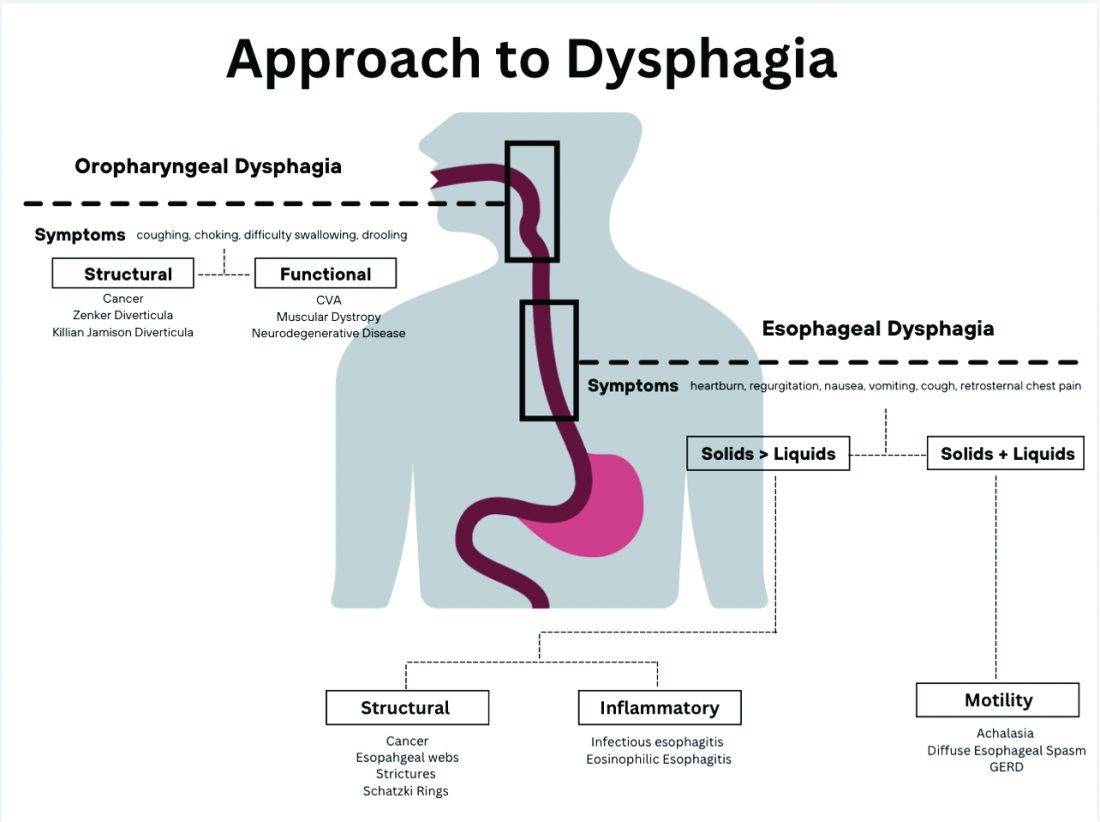

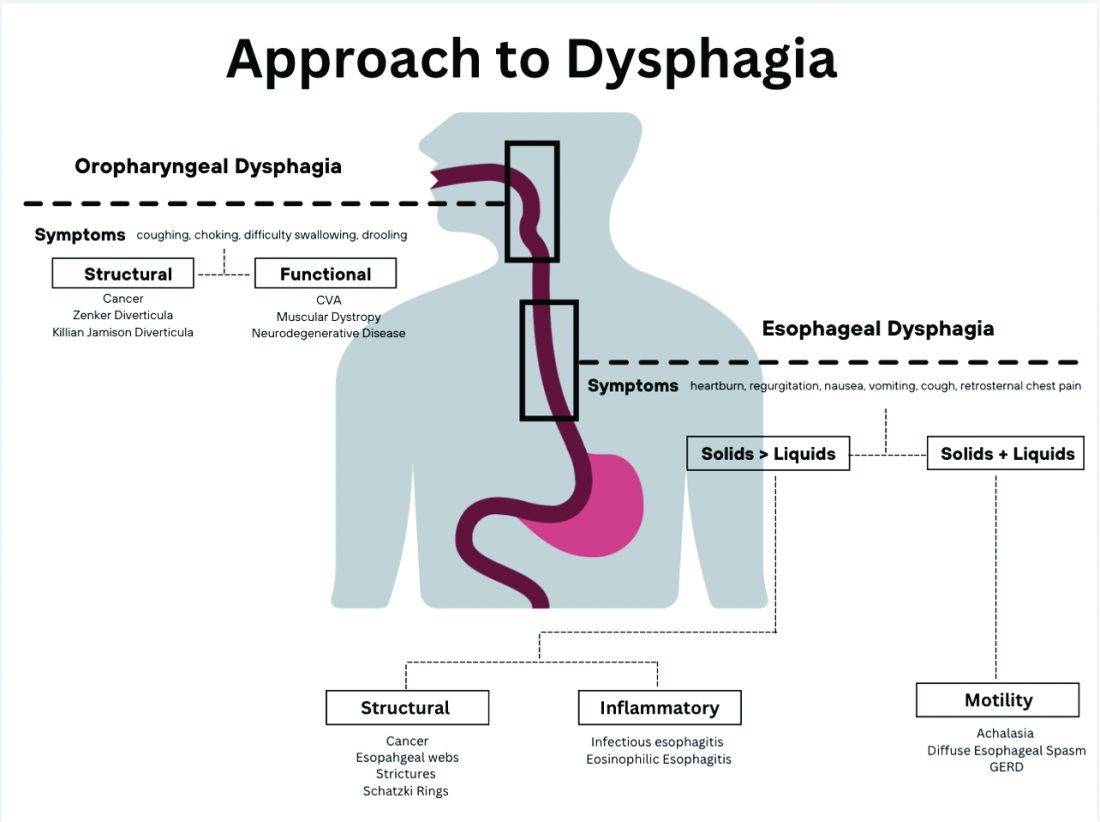

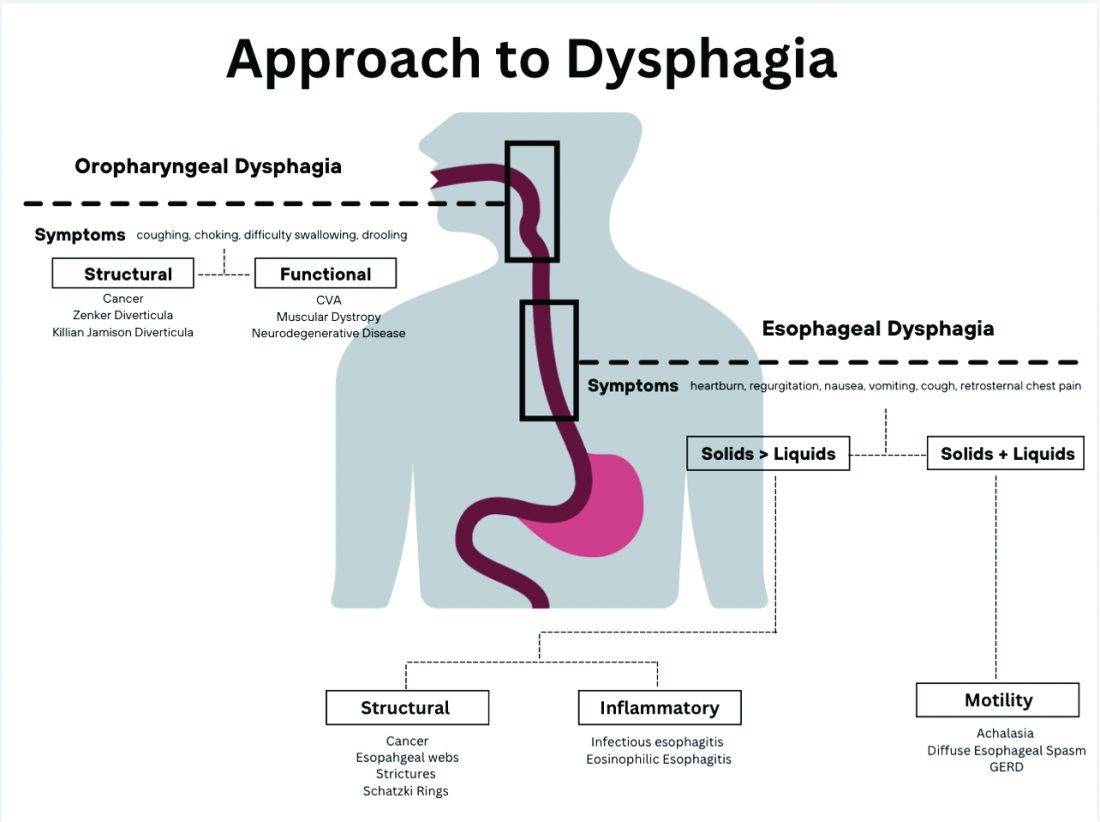

The diagnosis of esophageal dysphagia can be challenging. An initial, thorough history is essential to delineate between oropharyngeal and esophageal dysphagia and guide subsequent diagnostic testing. In recent years, there have been a number of advances in the approach to diagnosing dysphagia, including novel diagnostic modalities. The goal of this review article is to discuss the current approach to esophageal dysphagia and future direction to allow for timely diagnosis and management.

History

The diagnosis of dysphagia begins with a thorough history. Questions about the timing, onset, progression, localization of symptoms, and types of food that are difficult to swallow are essential in differentiating oropharyngeal and esophageal dysphagia.3,4 Further history taking must include medication and allergy review, smoking history, and review of prior radiation or surgical therapies to the head and neck.

Briefly, oropharyngeal dysphagia is difficulty initiating a swallow or passing food from the mouth or throat and can be caused by structural or functional etiologies.5 Clinical presentations include a sensation of food stuck in the back of the throat, coughing or choking while eating, or drooling. Structural causes include head and neck cancer, Zenker diverticulum, Killian Jamieson diverticula, prolonged intubation, or changes secondary to prior surgery or radiation.3 Functional causes may include neurologic, rheumatologic, or muscular disorders.6

Esophageal dysphagia refers to difficulty transporting food or liquid down the esophagus and can be caused by structural, inflammatory, or functional disorders.5 Patients typically localize symptoms of heartburn, regurgitation, nausea, vomiting, cough, or chest pain along the sternum or epigastric region. Alarm signs concerning for malignancy include unintentional weight loss, fevers, or night sweats.3,7 Aside from symptoms, medication review is essential, as dysphagia is a common side effect of antipsychotics, anticholinergics, antimuscarinics, narcotics, and immunosuppressant drugs.8 Larger pills such as NSAIDs, antibiotics, bisphosphonates, potassium supplements, and methylxanthines can cause drug-induced esophagitis, which can initially present as dysphagia.8 Inflammatory causes can be elucidated by obtaining a history about allergies, tobacco use, and recent infections such as thrush or pneumonia. Patients with a history of recurrent pneumonias may be silently aspirating, a complication of dysphagia.3 Once esophageal dysphagia is clinically suspected based on history, workup can begin.

Differentiating etiologies of esophageal dysphagia

The next step in diagnosing esophageal dysphagia is differentiating between structural, inflammatory, or dysmotility etiology (Figure 1).

Patients with a structural cause typically have difficulty swallowing solids but are able to swallow liquids unless the disease progresses. Symptoms can rapidly worsen and lead to odynophagia, weight loss, and vomiting. In comparison, patients with motility disorders typically have difficulty swallowing both solids and liquids initially, and symptoms can be constant or intermittent.5

Prior to diagnostic studies, a 4-week trial of a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) is appropriate for patients with reflux symptoms who are younger than 50 with no alarm features concerning for malignancy.7,9 If symptoms persist after a PPI trial, then an upper endoscopy (EGD) is indicated. An EGD allows for visualization of structural etiologies, obtaining biopsies to rule out inflammatory etiologies, and the option to therapeutically treat reduced luminal diameter with dilatation.10 The most common structural and inflammatory etiologies noted on EGD include strictures, webs, carcinomas, Schatzki rings, and gastroesophageal reflux or eosinophilic esophagitis.4

If upper endoscopy is normal and clinical suspicion for an obstructive cause remains high, barium esophagram can be utilized as an adjunctive study. Previously, barium esophagram was the initial test to distinguish between structural and motility disorders. The benefits of endoscopy over barium esophagram as the first diagnostic study include higher diagnostic yield, higher sensitivity and specificity, and lower costs.7 However, barium studies may be more sensitive for lower esophageal rings or extrinsic esophageal compression.3

Evaluation of esophageal motility disorder

If a structural or inflammatory etiology of dysphagia is not identified, investigation for an esophageal motility disorder (EMD) is warranted. Examples of motility disorders include achalasia, ineffective esophageal motility, hypercontractility, spasticity, or esophagogastric junction outflow obstruction (EGJOO).10,11 High-resolution esophageal manometry (HRM) remains the gold standard in diagnosis of EMD.12 An HRM catheter utilizes 36 sensors placed two centimeters apart and is placed in the esophagus to evaluate pressure and peristalsis between the upper and lower esophageal sphincters.13 In 2009, the Chicago Classification System was developed to provide a diagnostic algorithm that categorizes EMD based on HRM testing, with the most recent version (4.0) being published in 2020.12,14 Motility diagnoses are divided into two general classifications of disorders of body peristalsis and disorders of EGJ outflow. The most recent updates also include changes in swallow protocols, patient positioning, targeted symptoms, addition of impedance sensors, and consideration of supplemental testing when HRM is inconclusive based on the clinical context.12 There are some limitations of HRM to highlight. One of the main diagnostic values used with HRM is the integrated relaxation pressure (IRP). Despite standardization, IRP measurements vary based on the recorder and patient position. A minority of patients with achalasia may have IRP that does not approach the accepted cutoff and, therefore, the EGJ is not accurately assessed on HRM.15,16 In addition, some swallow protocols have lower sensitivity and specificity for certain motility disorders, and the test can result as inconclusive.14 In these scenarios, supplemental testing with timed barium esophagram or functional luminal imaging probe (EndoFLIP) is indicated.10,11

Over the past decade, EndoFLIP has emerged as a novel diagnostic tool in evaluating EMD. EndoFLIP is usually completed during an upper endoscopy and utilizes impedance planimetry to measure cross-sectional area and esophageal distensibility and evaluate contractile patterns.16 During the procedure, a small catheter with an inflatable balloon is inserted into the esophagus with the distal end in the stomach, traversing the esophagogastric junction (EGJ). The pressure transducer has electrodes every centimeter to allow for a three-dimensional construction of the esophagus and EGJ.17 EndoFLIP has been shown to accurately measure pyloric diameter, pressure, and distensibility at certain balloon volumes.18 In addition, FLIP is being used to further identify aspects of esophageal dysmotility in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis, thought primarily to be an inflammatory disorder.19 However, limitations include minimal accessibility of EndoFLIP within clinical practice and a specific computer program needed to generate the topographic plots.20

When used in conjunction with HRM, EndoFLIP provides complementary data that can be used to better detect major motility disorders.15,20,21 Each study adds unique information about the different physiologic events comprising the esophageal response to distention. Overall, the benefits of EndoFLIP include expediting workup during index endoscopy, patient comfort with sedation, and real-time diagnostic data that supplement results obtained during HRM.10,16,20,2223

Of note, if the diagnostic evaluation for structural, inflammatory, and motility disorders are unrevealing, investigating for atypical reflux symptoms can be pursued for patients with persistent dysphagia. Studies investigating pH, or acidity in the esophagus, in relation to symptoms, can be conducted wirelessly via a capsule fixed to the mucosa or with a nasal catheter.3

Normal workup – hypervigilance

In a subset of patients, all diagnostic testing for structural, inflammatory, or motility disorders is normal. These patients are classified as having a functional esophageal disorder. Despite normal testing, patients still have significant symptoms including epigastric pain, chest pain, globus sensation, or difficulty swallowing. It is theorized that a degree of visceral hypersensitivity between the brain-gut axis contributes to ongoing symptoms.24 Studies for effective treatments are ongoing but typically include cognitive-behavioral therapy, brain-gut behavioral therapy, swallow therapy antidepressants, or short courses of proton pump inhibitors.9

Conclusion

In this review article, we discussed the diagnostic approach for esophageal dysphagia. Initial assessment requires a thorough history, differentiation between oropharyngeal and esophageal dysphagia, and determination of who warrants an upper endoscopy. Upper endoscopy may reveal structural or inflammatory causes of dysphagia, including strictures, masses, or esophagitis, to name a few. If a structural or inflammatory cause is ruled out, this warrants investigation for esophageal motility disorders. The current gold standard for diagnosing EMD is manometry, and supplemental studies, including EndoFLIP, barium esophagram, and pH studies, may provide complimentary data. If workup for dysphagia is normal, evaluation for esophageal hypervigilance causing increased sensitivity to normal or mild sensations may be warranted. In conclusion, the diagnosis of dysphagia is challenging and requires investigation with a systematic approach to ensure timely diagnosis and treatment

Dr. Ronnie and Dr. Bloomberg are in the department of internal medicine at Loyola University Chicago, Maywood, Ill. Dr. Venu is in the division of gastroenterology at Loyola. He is on the speakers bureau at Medtronic.

References

1. Adkins C et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18(9):1970-9.e2.

2. Bhattacharyya N. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;151(5):765-9.

3. McCarty EB and Chao TN. Med Clin North Am. 2021;105(5):939-54.

4. Thiyagalingam S et al. Mayo Clin Proc. 2021;96(2):488-97.

5. Malagelada JR et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2015;49(5):370-8.

6. Rommel, N and Hamdy S. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;13(1):49-59.

7. Liu LWC et al. J Can Assoc Gastroenterol. 2018;1(1):5-19.

8. Schwemmle C et al. HNO. 2015;63(7):504-10.

9. Moayyedi P et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112(7):988-1013.

10. Triggs J and Pandolfino J. F1000Res. 2019 Aug 29. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.18900.1.

11. Yadlapati R et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021;33(1):e14058.

12. Yadlapati R et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021;33(1):e14053.

13. Fox M et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2004;16(5):533-42.

14. Sweis R and Fox M. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2020;22(10):49.

15. Carlson DA et al. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(7):1742-51.

16. Donnan EN and Pandolfino JE. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2020;49(3):427-35.

17. Carlson DA. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2016;32(4):310-8.

18. Zheng T et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2022;34(10):e14386.

19. Carlson DA et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(8):1719-28.e3.

20. Carlson DA et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111(12):1726-35.

21. Carlson DA et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021;33(10):e14116.

22. Carlson DA et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2019;90(6):915-923.e1.

23. Fox MR et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021;33(4):e14120.

24. Aziz Q et al. Gastroenterology. 2016 Feb 15. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.012.

Introduction

Dysphagia is the sensation of difficulty swallowing food or liquid in the acute or chronic setting. The prevalence of dysphagia ranges based on the type and etiology but may impact up to one in six adults.1,2 Dysphagia can cause a significant impact on a patient’s health and overall quality of life. A recent study found that only 50% of symptomatic adults seek medical care despite modifying their eating habits by either eating slowly or changing to softer foods or liquids.1 The most common, serious complications of dysphagia include aspiration pneumonia, malnutrition, and dehydration.3 According to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, dysphagia may be responsible for up to 60,000 deaths annually.3

The diagnosis of esophageal dysphagia can be challenging. An initial, thorough history is essential to delineate between oropharyngeal and esophageal dysphagia and guide subsequent diagnostic testing. In recent years, there have been a number of advances in the approach to diagnosing dysphagia, including novel diagnostic modalities. The goal of this review article is to discuss the current approach to esophageal dysphagia and future direction to allow for timely diagnosis and management.

History

The diagnosis of dysphagia begins with a thorough history. Questions about the timing, onset, progression, localization of symptoms, and types of food that are difficult to swallow are essential in differentiating oropharyngeal and esophageal dysphagia.3,4 Further history taking must include medication and allergy review, smoking history, and review of prior radiation or surgical therapies to the head and neck.

Briefly, oropharyngeal dysphagia is difficulty initiating a swallow or passing food from the mouth or throat and can be caused by structural or functional etiologies.5 Clinical presentations include a sensation of food stuck in the back of the throat, coughing or choking while eating, or drooling. Structural causes include head and neck cancer, Zenker diverticulum, Killian Jamieson diverticula, prolonged intubation, or changes secondary to prior surgery or radiation.3 Functional causes may include neurologic, rheumatologic, or muscular disorders.6

Esophageal dysphagia refers to difficulty transporting food or liquid down the esophagus and can be caused by structural, inflammatory, or functional disorders.5 Patients typically localize symptoms of heartburn, regurgitation, nausea, vomiting, cough, or chest pain along the sternum or epigastric region. Alarm signs concerning for malignancy include unintentional weight loss, fevers, or night sweats.3,7 Aside from symptoms, medication review is essential, as dysphagia is a common side effect of antipsychotics, anticholinergics, antimuscarinics, narcotics, and immunosuppressant drugs.8 Larger pills such as NSAIDs, antibiotics, bisphosphonates, potassium supplements, and methylxanthines can cause drug-induced esophagitis, which can initially present as dysphagia.8 Inflammatory causes can be elucidated by obtaining a history about allergies, tobacco use, and recent infections such as thrush or pneumonia. Patients with a history of recurrent pneumonias may be silently aspirating, a complication of dysphagia.3 Once esophageal dysphagia is clinically suspected based on history, workup can begin.

Differentiating etiologies of esophageal dysphagia

The next step in diagnosing esophageal dysphagia is differentiating between structural, inflammatory, or dysmotility etiology (Figure 1).

Patients with a structural cause typically have difficulty swallowing solids but are able to swallow liquids unless the disease progresses. Symptoms can rapidly worsen and lead to odynophagia, weight loss, and vomiting. In comparison, patients with motility disorders typically have difficulty swallowing both solids and liquids initially, and symptoms can be constant or intermittent.5

Prior to diagnostic studies, a 4-week trial of a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) is appropriate for patients with reflux symptoms who are younger than 50 with no alarm features concerning for malignancy.7,9 If symptoms persist after a PPI trial, then an upper endoscopy (EGD) is indicated. An EGD allows for visualization of structural etiologies, obtaining biopsies to rule out inflammatory etiologies, and the option to therapeutically treat reduced luminal diameter with dilatation.10 The most common structural and inflammatory etiologies noted on EGD include strictures, webs, carcinomas, Schatzki rings, and gastroesophageal reflux or eosinophilic esophagitis.4

If upper endoscopy is normal and clinical suspicion for an obstructive cause remains high, barium esophagram can be utilized as an adjunctive study. Previously, barium esophagram was the initial test to distinguish between structural and motility disorders. The benefits of endoscopy over barium esophagram as the first diagnostic study include higher diagnostic yield, higher sensitivity and specificity, and lower costs.7 However, barium studies may be more sensitive for lower esophageal rings or extrinsic esophageal compression.3

Evaluation of esophageal motility disorder

If a structural or inflammatory etiology of dysphagia is not identified, investigation for an esophageal motility disorder (EMD) is warranted. Examples of motility disorders include achalasia, ineffective esophageal motility, hypercontractility, spasticity, or esophagogastric junction outflow obstruction (EGJOO).10,11 High-resolution esophageal manometry (HRM) remains the gold standard in diagnosis of EMD.12 An HRM catheter utilizes 36 sensors placed two centimeters apart and is placed in the esophagus to evaluate pressure and peristalsis between the upper and lower esophageal sphincters.13 In 2009, the Chicago Classification System was developed to provide a diagnostic algorithm that categorizes EMD based on HRM testing, with the most recent version (4.0) being published in 2020.12,14 Motility diagnoses are divided into two general classifications of disorders of body peristalsis and disorders of EGJ outflow. The most recent updates also include changes in swallow protocols, patient positioning, targeted symptoms, addition of impedance sensors, and consideration of supplemental testing when HRM is inconclusive based on the clinical context.12 There are some limitations of HRM to highlight. One of the main diagnostic values used with HRM is the integrated relaxation pressure (IRP). Despite standardization, IRP measurements vary based on the recorder and patient position. A minority of patients with achalasia may have IRP that does not approach the accepted cutoff and, therefore, the EGJ is not accurately assessed on HRM.15,16 In addition, some swallow protocols have lower sensitivity and specificity for certain motility disorders, and the test can result as inconclusive.14 In these scenarios, supplemental testing with timed barium esophagram or functional luminal imaging probe (EndoFLIP) is indicated.10,11

Over the past decade, EndoFLIP has emerged as a novel diagnostic tool in evaluating EMD. EndoFLIP is usually completed during an upper endoscopy and utilizes impedance planimetry to measure cross-sectional area and esophageal distensibility and evaluate contractile patterns.16 During the procedure, a small catheter with an inflatable balloon is inserted into the esophagus with the distal end in the stomach, traversing the esophagogastric junction (EGJ). The pressure transducer has electrodes every centimeter to allow for a three-dimensional construction of the esophagus and EGJ.17 EndoFLIP has been shown to accurately measure pyloric diameter, pressure, and distensibility at certain balloon volumes.18 In addition, FLIP is being used to further identify aspects of esophageal dysmotility in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis, thought primarily to be an inflammatory disorder.19 However, limitations include minimal accessibility of EndoFLIP within clinical practice and a specific computer program needed to generate the topographic plots.20

When used in conjunction with HRM, EndoFLIP provides complementary data that can be used to better detect major motility disorders.15,20,21 Each study adds unique information about the different physiologic events comprising the esophageal response to distention. Overall, the benefits of EndoFLIP include expediting workup during index endoscopy, patient comfort with sedation, and real-time diagnostic data that supplement results obtained during HRM.10,16,20,2223

Of note, if the diagnostic evaluation for structural, inflammatory, and motility disorders are unrevealing, investigating for atypical reflux symptoms can be pursued for patients with persistent dysphagia. Studies investigating pH, or acidity in the esophagus, in relation to symptoms, can be conducted wirelessly via a capsule fixed to the mucosa or with a nasal catheter.3

Normal workup – hypervigilance

In a subset of patients, all diagnostic testing for structural, inflammatory, or motility disorders is normal. These patients are classified as having a functional esophageal disorder. Despite normal testing, patients still have significant symptoms including epigastric pain, chest pain, globus sensation, or difficulty swallowing. It is theorized that a degree of visceral hypersensitivity between the brain-gut axis contributes to ongoing symptoms.24 Studies for effective treatments are ongoing but typically include cognitive-behavioral therapy, brain-gut behavioral therapy, swallow therapy antidepressants, or short courses of proton pump inhibitors.9

Conclusion

In this review article, we discussed the diagnostic approach for esophageal dysphagia. Initial assessment requires a thorough history, differentiation between oropharyngeal and esophageal dysphagia, and determination of who warrants an upper endoscopy. Upper endoscopy may reveal structural or inflammatory causes of dysphagia, including strictures, masses, or esophagitis, to name a few. If a structural or inflammatory cause is ruled out, this warrants investigation for esophageal motility disorders. The current gold standard for diagnosing EMD is manometry, and supplemental studies, including EndoFLIP, barium esophagram, and pH studies, may provide complimentary data. If workup for dysphagia is normal, evaluation for esophageal hypervigilance causing increased sensitivity to normal or mild sensations may be warranted. In conclusion, the diagnosis of dysphagia is challenging and requires investigation with a systematic approach to ensure timely diagnosis and treatment

Dr. Ronnie and Dr. Bloomberg are in the department of internal medicine at Loyola University Chicago, Maywood, Ill. Dr. Venu is in the division of gastroenterology at Loyola. He is on the speakers bureau at Medtronic.

References

1. Adkins C et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18(9):1970-9.e2.

2. Bhattacharyya N. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;151(5):765-9.

3. McCarty EB and Chao TN. Med Clin North Am. 2021;105(5):939-54.

4. Thiyagalingam S et al. Mayo Clin Proc. 2021;96(2):488-97.

5. Malagelada JR et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2015;49(5):370-8.

6. Rommel, N and Hamdy S. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;13(1):49-59.

7. Liu LWC et al. J Can Assoc Gastroenterol. 2018;1(1):5-19.

8. Schwemmle C et al. HNO. 2015;63(7):504-10.

9. Moayyedi P et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112(7):988-1013.

10. Triggs J and Pandolfino J. F1000Res. 2019 Aug 29. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.18900.1.

11. Yadlapati R et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021;33(1):e14058.

12. Yadlapati R et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021;33(1):e14053.

13. Fox M et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2004;16(5):533-42.

14. Sweis R and Fox M. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2020;22(10):49.

15. Carlson DA et al. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(7):1742-51.

16. Donnan EN and Pandolfino JE. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2020;49(3):427-35.

17. Carlson DA. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2016;32(4):310-8.

18. Zheng T et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2022;34(10):e14386.

19. Carlson DA et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(8):1719-28.e3.

20. Carlson DA et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111(12):1726-35.

21. Carlson DA et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021;33(10):e14116.

22. Carlson DA et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2019;90(6):915-923.e1.

23. Fox MR et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021;33(4):e14120.

24. Aziz Q et al. Gastroenterology. 2016 Feb 15. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.012.

Introduction

Dysphagia is the sensation of difficulty swallowing food or liquid in the acute or chronic setting. The prevalence of dysphagia ranges based on the type and etiology but may impact up to one in six adults.1,2 Dysphagia can cause a significant impact on a patient’s health and overall quality of life. A recent study found that only 50% of symptomatic adults seek medical care despite modifying their eating habits by either eating slowly or changing to softer foods or liquids.1 The most common, serious complications of dysphagia include aspiration pneumonia, malnutrition, and dehydration.3 According to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, dysphagia may be responsible for up to 60,000 deaths annually.3

The diagnosis of esophageal dysphagia can be challenging. An initial, thorough history is essential to delineate between oropharyngeal and esophageal dysphagia and guide subsequent diagnostic testing. In recent years, there have been a number of advances in the approach to diagnosing dysphagia, including novel diagnostic modalities. The goal of this review article is to discuss the current approach to esophageal dysphagia and future direction to allow for timely diagnosis and management.

History

The diagnosis of dysphagia begins with a thorough history. Questions about the timing, onset, progression, localization of symptoms, and types of food that are difficult to swallow are essential in differentiating oropharyngeal and esophageal dysphagia.3,4 Further history taking must include medication and allergy review, smoking history, and review of prior radiation or surgical therapies to the head and neck.

Briefly, oropharyngeal dysphagia is difficulty initiating a swallow or passing food from the mouth or throat and can be caused by structural or functional etiologies.5 Clinical presentations include a sensation of food stuck in the back of the throat, coughing or choking while eating, or drooling. Structural causes include head and neck cancer, Zenker diverticulum, Killian Jamieson diverticula, prolonged intubation, or changes secondary to prior surgery or radiation.3 Functional causes may include neurologic, rheumatologic, or muscular disorders.6

Esophageal dysphagia refers to difficulty transporting food or liquid down the esophagus and can be caused by structural, inflammatory, or functional disorders.5 Patients typically localize symptoms of heartburn, regurgitation, nausea, vomiting, cough, or chest pain along the sternum or epigastric region. Alarm signs concerning for malignancy include unintentional weight loss, fevers, or night sweats.3,7 Aside from symptoms, medication review is essential, as dysphagia is a common side effect of antipsychotics, anticholinergics, antimuscarinics, narcotics, and immunosuppressant drugs.8 Larger pills such as NSAIDs, antibiotics, bisphosphonates, potassium supplements, and methylxanthines can cause drug-induced esophagitis, which can initially present as dysphagia.8 Inflammatory causes can be elucidated by obtaining a history about allergies, tobacco use, and recent infections such as thrush or pneumonia. Patients with a history of recurrent pneumonias may be silently aspirating, a complication of dysphagia.3 Once esophageal dysphagia is clinically suspected based on history, workup can begin.

Differentiating etiologies of esophageal dysphagia

The next step in diagnosing esophageal dysphagia is differentiating between structural, inflammatory, or dysmotility etiology (Figure 1).

Patients with a structural cause typically have difficulty swallowing solids but are able to swallow liquids unless the disease progresses. Symptoms can rapidly worsen and lead to odynophagia, weight loss, and vomiting. In comparison, patients with motility disorders typically have difficulty swallowing both solids and liquids initially, and symptoms can be constant or intermittent.5

Prior to diagnostic studies, a 4-week trial of a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) is appropriate for patients with reflux symptoms who are younger than 50 with no alarm features concerning for malignancy.7,9 If symptoms persist after a PPI trial, then an upper endoscopy (EGD) is indicated. An EGD allows for visualization of structural etiologies, obtaining biopsies to rule out inflammatory etiologies, and the option to therapeutically treat reduced luminal diameter with dilatation.10 The most common structural and inflammatory etiologies noted on EGD include strictures, webs, carcinomas, Schatzki rings, and gastroesophageal reflux or eosinophilic esophagitis.4

If upper endoscopy is normal and clinical suspicion for an obstructive cause remains high, barium esophagram can be utilized as an adjunctive study. Previously, barium esophagram was the initial test to distinguish between structural and motility disorders. The benefits of endoscopy over barium esophagram as the first diagnostic study include higher diagnostic yield, higher sensitivity and specificity, and lower costs.7 However, barium studies may be more sensitive for lower esophageal rings or extrinsic esophageal compression.3

Evaluation of esophageal motility disorder

If a structural or inflammatory etiology of dysphagia is not identified, investigation for an esophageal motility disorder (EMD) is warranted. Examples of motility disorders include achalasia, ineffective esophageal motility, hypercontractility, spasticity, or esophagogastric junction outflow obstruction (EGJOO).10,11 High-resolution esophageal manometry (HRM) remains the gold standard in diagnosis of EMD.12 An HRM catheter utilizes 36 sensors placed two centimeters apart and is placed in the esophagus to evaluate pressure and peristalsis between the upper and lower esophageal sphincters.13 In 2009, the Chicago Classification System was developed to provide a diagnostic algorithm that categorizes EMD based on HRM testing, with the most recent version (4.0) being published in 2020.12,14 Motility diagnoses are divided into two general classifications of disorders of body peristalsis and disorders of EGJ outflow. The most recent updates also include changes in swallow protocols, patient positioning, targeted symptoms, addition of impedance sensors, and consideration of supplemental testing when HRM is inconclusive based on the clinical context.12 There are some limitations of HRM to highlight. One of the main diagnostic values used with HRM is the integrated relaxation pressure (IRP). Despite standardization, IRP measurements vary based on the recorder and patient position. A minority of patients with achalasia may have IRP that does not approach the accepted cutoff and, therefore, the EGJ is not accurately assessed on HRM.15,16 In addition, some swallow protocols have lower sensitivity and specificity for certain motility disorders, and the test can result as inconclusive.14 In these scenarios, supplemental testing with timed barium esophagram or functional luminal imaging probe (EndoFLIP) is indicated.10,11

Over the past decade, EndoFLIP has emerged as a novel diagnostic tool in evaluating EMD. EndoFLIP is usually completed during an upper endoscopy and utilizes impedance planimetry to measure cross-sectional area and esophageal distensibility and evaluate contractile patterns.16 During the procedure, a small catheter with an inflatable balloon is inserted into the esophagus with the distal end in the stomach, traversing the esophagogastric junction (EGJ). The pressure transducer has electrodes every centimeter to allow for a three-dimensional construction of the esophagus and EGJ.17 EndoFLIP has been shown to accurately measure pyloric diameter, pressure, and distensibility at certain balloon volumes.18 In addition, FLIP is being used to further identify aspects of esophageal dysmotility in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis, thought primarily to be an inflammatory disorder.19 However, limitations include minimal accessibility of EndoFLIP within clinical practice and a specific computer program needed to generate the topographic plots.20

When used in conjunction with HRM, EndoFLIP provides complementary data that can be used to better detect major motility disorders.15,20,21 Each study adds unique information about the different physiologic events comprising the esophageal response to distention. Overall, the benefits of EndoFLIP include expediting workup during index endoscopy, patient comfort with sedation, and real-time diagnostic data that supplement results obtained during HRM.10,16,20,2223

Of note, if the diagnostic evaluation for structural, inflammatory, and motility disorders are unrevealing, investigating for atypical reflux symptoms can be pursued for patients with persistent dysphagia. Studies investigating pH, or acidity in the esophagus, in relation to symptoms, can be conducted wirelessly via a capsule fixed to the mucosa or with a nasal catheter.3

Normal workup – hypervigilance

In a subset of patients, all diagnostic testing for structural, inflammatory, or motility disorders is normal. These patients are classified as having a functional esophageal disorder. Despite normal testing, patients still have significant symptoms including epigastric pain, chest pain, globus sensation, or difficulty swallowing. It is theorized that a degree of visceral hypersensitivity between the brain-gut axis contributes to ongoing symptoms.24 Studies for effective treatments are ongoing but typically include cognitive-behavioral therapy, brain-gut behavioral therapy, swallow therapy antidepressants, or short courses of proton pump inhibitors.9

Conclusion

In this review article, we discussed the diagnostic approach for esophageal dysphagia. Initial assessment requires a thorough history, differentiation between oropharyngeal and esophageal dysphagia, and determination of who warrants an upper endoscopy. Upper endoscopy may reveal structural or inflammatory causes of dysphagia, including strictures, masses, or esophagitis, to name a few. If a structural or inflammatory cause is ruled out, this warrants investigation for esophageal motility disorders. The current gold standard for diagnosing EMD is manometry, and supplemental studies, including EndoFLIP, barium esophagram, and pH studies, may provide complimentary data. If workup for dysphagia is normal, evaluation for esophageal hypervigilance causing increased sensitivity to normal or mild sensations may be warranted. In conclusion, the diagnosis of dysphagia is challenging and requires investigation with a systematic approach to ensure timely diagnosis and treatment

Dr. Ronnie and Dr. Bloomberg are in the department of internal medicine at Loyola University Chicago, Maywood, Ill. Dr. Venu is in the division of gastroenterology at Loyola. He is on the speakers bureau at Medtronic.

References

1. Adkins C et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18(9):1970-9.e2.

2. Bhattacharyya N. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;151(5):765-9.

3. McCarty EB and Chao TN. Med Clin North Am. 2021;105(5):939-54.

4. Thiyagalingam S et al. Mayo Clin Proc. 2021;96(2):488-97.

5. Malagelada JR et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2015;49(5):370-8.

6. Rommel, N and Hamdy S. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;13(1):49-59.

7. Liu LWC et al. J Can Assoc Gastroenterol. 2018;1(1):5-19.

8. Schwemmle C et al. HNO. 2015;63(7):504-10.

9. Moayyedi P et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112(7):988-1013.

10. Triggs J and Pandolfino J. F1000Res. 2019 Aug 29. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.18900.1.

11. Yadlapati R et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021;33(1):e14058.

12. Yadlapati R et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021;33(1):e14053.

13. Fox M et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2004;16(5):533-42.

14. Sweis R and Fox M. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2020;22(10):49.

15. Carlson DA et al. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(7):1742-51.

16. Donnan EN and Pandolfino JE. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2020;49(3):427-35.

17. Carlson DA. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2016;32(4):310-8.

18. Zheng T et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2022;34(10):e14386.

19. Carlson DA et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(8):1719-28.e3.

20. Carlson DA et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111(12):1726-35.

21. Carlson DA et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021;33(10):e14116.

22. Carlson DA et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2019;90(6):915-923.e1.

23. Fox MR et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021;33(4):e14120.

24. Aziz Q et al. Gastroenterology. 2016 Feb 15. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.012.

COVID raises risk for long-term GI complications

, a large new study indicates.

The researchers estimate that, so far, SARS-CoV-2 infections have contributed to more than 6 million new cases of GI disorders in the United States and 42 million new cases worldwide.

The diagnoses more common among patients who’ve had COVID ranged from stomach upset to acute pancreatitis, say the researchers, led by Evan Xu, a data analyst at the Clinical Epidemiology Center, Research and Development Service, VA St. Louis Health Care System.

Signs and symptoms of GI problems, such as constipation and diarrhea, also were more common among patients who had had the virus, the study found.

“Altogether, our results show that people with SARS-CoV-2 infection are at increased risk of gastrointestinal disorders in the post-acute phase of COVID-19,” the researchers write. “Post-COVID care should involve attention to gastrointestinal health and disease.”

The results were published online in Nature Communications.

Disease risks jump