User login

ECHO-CT: An Interdisciplinary Videoconference Model for Identifying Potential Postdischarge Transition-of-Care Events

As the population of the United States continues to age, hospitals are seeing an increasing number of older patients with significant medical and social complexity. Medicare data have shown that an increasing number require post–acute care after a hospitalization.1 Discharges to post–acute care settings are often longer and more costly compared with discharges to other settings, which suggests that targeting quality improvement efforts at this transition period may improve the value of care.2

The transition from the hospital setting to a post–acute care facility can be dangerous and complicated due to lapses in communication, medication errors, and the complexity of medical treatment plans. Suboptimal transitions in care can result in adverse events for the patient, as well as confusion in medication regimens or incomplete plans for follow-up care.3

The Project ECHO (Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes) model was first developed and launched by Sanjeev Arora, MD, in New Mexico in 2003 to expand access to subspecialist care using videoconferencing.4 We first applied this model in 2013 to evaluate the impact of this interdisciplinary videoconferencing tool on the care of patients discharged to post–acute settings.5 We found that patients participating in the Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes–Care Transitions (ECHO-CT) model experienced decreased risk of rehospitalization, decreased skilled nursing facility (SNF) length of stay, and reduced 30-day healthcare costs, compared with those patients not enrolled in this program; these outcomes were likely due to identification and correction of medication-related errors, improved care coordination, improved disease management, and clarification of goals of care.6 Though these investigations did identify some issues arising during the care transition process, they did not fully describe the types of problems uncovered. We sought to better characterize the clinical and operational issues identified through the ECHO-CT conference, hereafter known as transition-of-care events (TCEs). These issues may include new or evolving medical concerns, an adverse event, or a “near miss.” Identification and classification of TCEs that may contribute to unsafe or fractured care transitions are critical in developing systematic solutions to improve transitions of care, which can ultimately improve patient safety and potentially avoid preventable errors.

METHODS

ECHO-CT Multidisciplinary Video Conference

We conducted ECHO-CT at a large, tertiary care academic medical center. The project design for the ECHO-CT program has been previously described.5 In brief, the program is a weekly, multidisciplinary videoconference between a hospital-based team and post–acute care providers to discuss patients discharged from inpatient services to post–acute care sites, including SNFs and long-term acute care hospitals (LTACHs), during the preceding week. All patients discharged from the tertiary care inpatient site to one of the eight participating SNFs or LTACHs, from either a medical or surgical service, are eligible to be discussed at this weekly interdisciplinary conference. Long-term care facilities were not included in this study. The ECHO-CT program used HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act)-compliant videoconferencing technology to connect hospital and post–acute care providers.

During the videoconferences, each patient’s hospital course and discharge documentation are reviewed by a hospitalist, and a pharmacist performs a medication reconciliation of each patient’s admission, discharge, and post–acute care medication list. The discharging attending, primary care providers, residents, other trainees, and subspecialist providers are invited to attend. Typically, the interdisciplinary team at the post–acute care sites includes physicians, nurse practitioners, physical therapists, social workers, and case managers. Between 10 and 20 patients are discussed in a case-based format, which includes a summary of the patient’s hospital course, an update from the post–acute care team on the patient’s care, and an opportunity for a discussion regarding any concerns or questions raised by the post–acute care or inpatient care teams. The content and duration of discussion typically lasts approximately 3 to 10 minutes, depending on the needs of the patient and the care team. Each of the eight post–acute care sites participating in the project are assigned a 10- to 15-minute block. A copy of the ECHO-CT session process document is included in the Appendix.

Data Collection

At each interdisciplinary patient review, TCEs were identified and recorded. These events were categorized in real time by the ECHO-CT data collection team into the following categories: medication related, medical, discharge communication/coordination, or other, and recorded in a secured, deidentified database. For individuals whose TCEs could represent more than one category, authors reviewed the available information about the TCEs and determined the most appropriate category; if more than one category was felt to be applicable to a patient’s situation, the events were reclassified into all applicable categories. Data about individual patients, including gender, age at the time of discharge, and other demographic information, were obtained from hospital databases. Number of diagnoses included any diagnosis billed during the patient’s hospital stay, and these data were obtained from a hospital billing database. Average number of medications at discharge was obtained from a hospital pharmacy database.

RESULTS

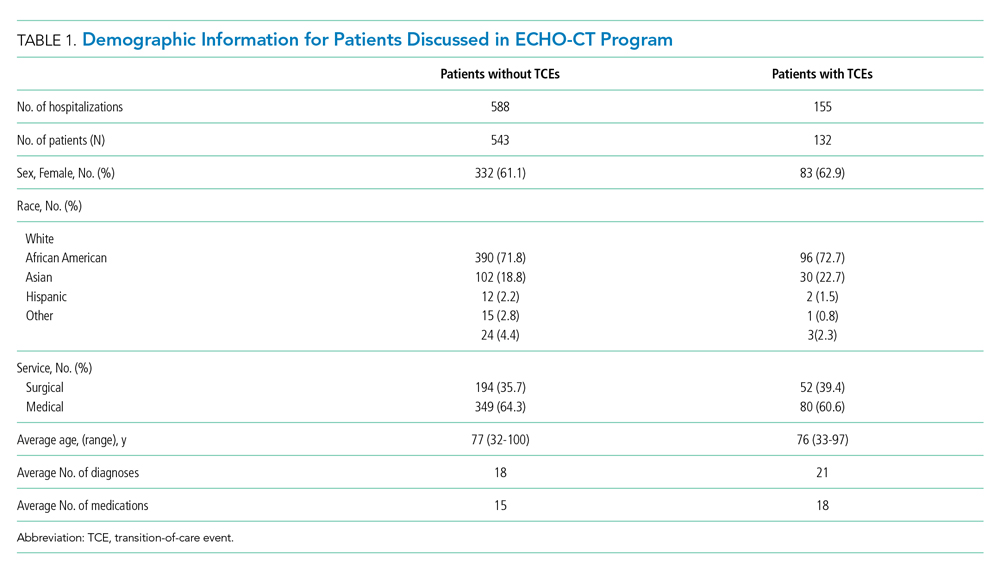

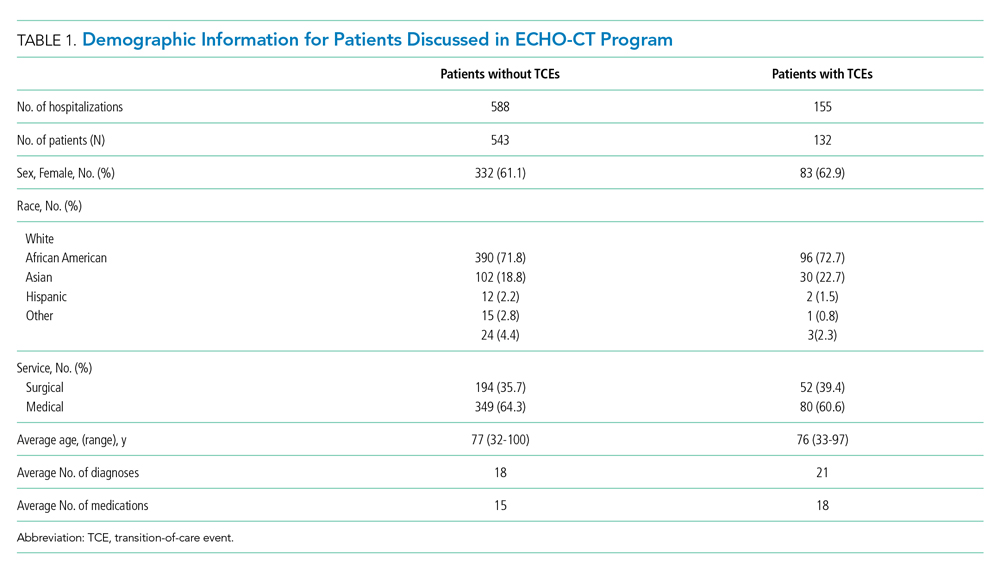

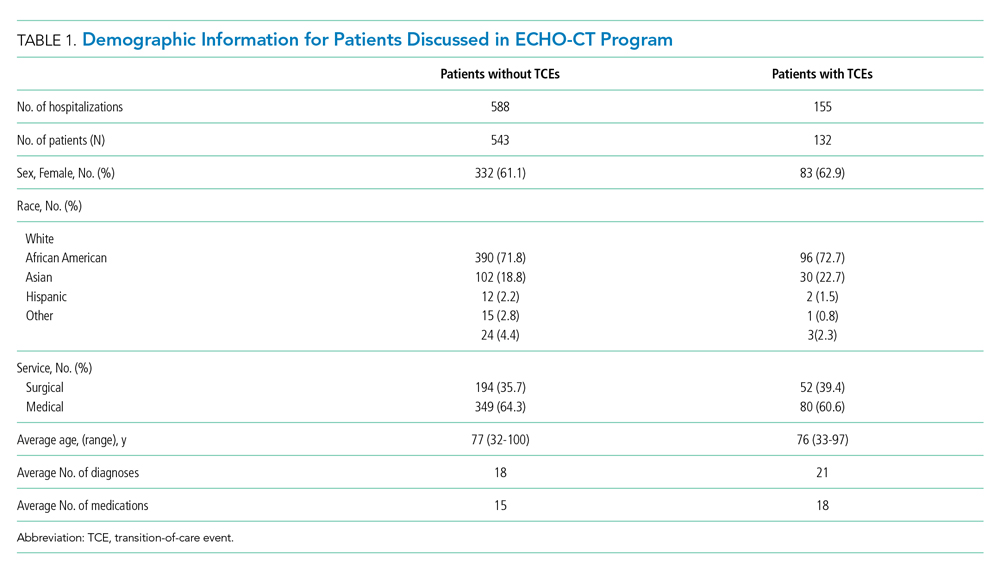

A total of 675 patients (experiencing 743 hospitalizations) were discharged from a medical or surgical service to one of the participating post–acute care sites from January 2016 to October 2018, and were discussed at the interdisciplinary conference. During that time, 139 TCEs were recorded for review, involving 132 patients (Table 1). Patients who experienced TCEs were noted to have a slightly higher average number of diagnoses than did those in the non-TCE group (21 vs 18, respectively) and number of medications (18 vs 15).

Representative examples of TCEs are provided in Table 2. Fifty-eight issues were identified as discharge communication or coordination issues (eg, discharge summary was late or missing at time of discharge to facility, transitional issues were unclear, follow-up appointments were not appropriately scheduled or documented). An additional 52 TCEs were identified as pharmacy or medication issues (eg, medications were inadvertently omitted from discharge medication list, prehospital medication list was incorrect). Medical issues accounted for an additional 27 concerns (eg, patient was hypoglycemic on arrival, inadequate pain control, discovery of new acute medical issues or medical diagnoses that were not clearly documented or communicated by the inpatient team). “Other” issues (two) included unaddressed social concerns, such as insurance issues.

DISCUSSION

The ECHO-CT model unites hospital and post–acute care providers to improve transitions of care and is unique in its focus on the transition from hospital to post–acute care rather than to home care. In 2 years of data collection, we identified several TCEs encompassing a range of concerns. Of the 675 patients discussed, 132 (20%) were noted to have a TCE. When these percentages are applied to the 140 million Medicare hospital discharges that took place during 2000 to 2015, we would estimate nearly 5.5 million TCEs, or 375,000 TCEs per year, that may have affected this population.

The majority of TCEs were communication and coordination errors. Missing or incomplete discharge paperwork, inadequate documentation of inpatient care, and confusion about medical devices or postoperative needs (eg, slings, braces, wound care, drains) were commonly reported. Follow-up appointments with specialists were often not appropriately scheduled or communicated. This may have resulted from unstandardized discharge documentation and a lower priority given to documentation in the setting of multiple clinical demands (eg, direct patient care, complex care coordination, and clinical paperwork and charting). Studies have demonstrated that fewer than one-third of discharge summaries are received by outpatient providers before postdischarge follow-up, and additionally that nearly 40% of patients did not undergo recommended workups for medical issues identified during their hospital stay.7,8 All of this is problematic because appropriate documentation in discharge summaries is associated with a decreased risk of hospital readmission.9

Pharmacy issues were the second most common TCE identified. One member of the post–acute care team noted that “omissions, additions, and replacements” relating to medications were common occurrences. Additionally, it was noted that medications were inadvertently continued for longer than planned or not adjusted appropriately with changing clinical parameters, such as renal function. The results of our analysis are consistent with current literature, which suggests that up to 60% of all medication errors occur during the period surrounding transitions of care.10

There were several limitations to this investigation. Though recording of identified TCEs occurred in real time, analysis of these identified events occurred retrospectively; therefore, investigators had limited ability to retroactively review or recategorize recorded issues, which potentially could have resulted in misclassification or misinterpretation. Additionally, the data were intended to be descriptive; therefore, outcomes such as hospital readmission and patient harm could not be linked to specific TCEs. Furthermore, it is possible that events were not detected by either the postdischarge team or the hospital-based team and, therefore, not captured in this analysis. Further work would be helpful to determine the root causes underlying the identified issues in care transitions, with the goal of improving patient safety and avoiding preventable errors during transitions of care. Although there is comprehensive literature related to errors and medication-related adverse events,11 there is not a consensus of how to classify and report, in a standardized fashion, events arising during the transition period. A validated structure for systematically identifying, monitoring, recording, and reporting issues arising during care transitions will be critical in preventing errors and ensuring patient safety during this high-risk period.

CONCLUSION

Our model is a unique intervention that uses the expertise and engagement of an interdisciplinary team and seeks to identify and remedy issues arising during transitions of care—in real time—to prevent direct harm to vulnerable patients. We have already implemented interventions to improve care based on our experiences with this videoconference-based program. For example, direct feedback was given to discharging teams to improve the discharge summary and associated documentation, and changes to the medication-ordering system were implemented to address specific medication errors discovered. The TCEs identified in this investigation highlight specific areas for improvement with the goal of providing high-quality care for patients and seamless transitions to post–acute care. As health systems and hospitals face new challenges in communication and care coordination, especially due to the recent COVID-19 pandemic, the technology and communication methods used in the ECHO-CT model may become even more relevant for promoting clear communication and patient safety during transitions of care.

Acknowledgment

The ECHO CT team thanks Sabrina Carretie for her contributions in data collection and analysis.

1. Werner RM, Konetzka RT. Trends in post-acute care use among medicare beneficiaries: 2000 to 2015. JAMA. 2018;319(15):1616–1617. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.2408

2. Tian W. An All-Payer View of Hospital Discharge to Postacute Care, 2013. Statistical Brief #205. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; May 2016. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb205-Hospital-Discharge-Postacute-Care.pdf

3. Kessler C, Williams MC, Moustoukas JN, Pappas C. Transitions of care for the geriatric patient in the emergency department. Clin Geriatr Med. 2013;29(1):49-69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cger.2012.10.005

4. Arora S, Thornton K, Jenkusky SM, Parish B, Scaletti JV. Project ECHO: linking university specialists with rural and prison-based clinicians to improve care for people with chronic hepatitis C in New Mexico. Public Health Rep. 2007;122(Suppl 2):74-77. https://doi.org/10.1177/00333549071220s214

5. Farris G, Sircar M, Bortinger J, et al. Extension for community healthcare outcomes–care transitions: enhancing geriatric care transitions through a multidisciplinary videoconference. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(3):598-602. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.14690

6. Moore AB, Krupp JE, Dufour AB, et al. Improving transitions to postacute care for elderly patients using a novel video-conferencing program: ECHO-Care transitions. Am J Med. 2017;130(10):1199-1204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.04.041

7. Kripalani S, LeFevre F, Phillips CO, Williams MV, Basaviah P, Baker DW. Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA. 2007;297(8):831–841. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.297.8.831

8. Moore C, McGinn T, Halm E. Tying up loose ends: discharging patients with unresolved medical issues. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(12):1305-1311. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.167.12.1305

9. van Walraven C, Seth R, Austin PC, Laupacis A. Effect of discharge summary availability during post-discharge visits on hospital readmission. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(3):186-192. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10741.x

10. Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, Gandhi TK, Bates DW. The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(3):161-167. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-138-3-200302040-00007

11. Claeys C, Nève J, Tulkens PM, Spinewine A. Content validity and inter-rater reliability of an instrument to characterize unintentional medication discrepancies. Drugs Aging. 2012;29(7):577-591. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf03262275

As the population of the United States continues to age, hospitals are seeing an increasing number of older patients with significant medical and social complexity. Medicare data have shown that an increasing number require post–acute care after a hospitalization.1 Discharges to post–acute care settings are often longer and more costly compared with discharges to other settings, which suggests that targeting quality improvement efforts at this transition period may improve the value of care.2

The transition from the hospital setting to a post–acute care facility can be dangerous and complicated due to lapses in communication, medication errors, and the complexity of medical treatment plans. Suboptimal transitions in care can result in adverse events for the patient, as well as confusion in medication regimens or incomplete plans for follow-up care.3

The Project ECHO (Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes) model was first developed and launched by Sanjeev Arora, MD, in New Mexico in 2003 to expand access to subspecialist care using videoconferencing.4 We first applied this model in 2013 to evaluate the impact of this interdisciplinary videoconferencing tool on the care of patients discharged to post–acute settings.5 We found that patients participating in the Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes–Care Transitions (ECHO-CT) model experienced decreased risk of rehospitalization, decreased skilled nursing facility (SNF) length of stay, and reduced 30-day healthcare costs, compared with those patients not enrolled in this program; these outcomes were likely due to identification and correction of medication-related errors, improved care coordination, improved disease management, and clarification of goals of care.6 Though these investigations did identify some issues arising during the care transition process, they did not fully describe the types of problems uncovered. We sought to better characterize the clinical and operational issues identified through the ECHO-CT conference, hereafter known as transition-of-care events (TCEs). These issues may include new or evolving medical concerns, an adverse event, or a “near miss.” Identification and classification of TCEs that may contribute to unsafe or fractured care transitions are critical in developing systematic solutions to improve transitions of care, which can ultimately improve patient safety and potentially avoid preventable errors.

METHODS

ECHO-CT Multidisciplinary Video Conference

We conducted ECHO-CT at a large, tertiary care academic medical center. The project design for the ECHO-CT program has been previously described.5 In brief, the program is a weekly, multidisciplinary videoconference between a hospital-based team and post–acute care providers to discuss patients discharged from inpatient services to post–acute care sites, including SNFs and long-term acute care hospitals (LTACHs), during the preceding week. All patients discharged from the tertiary care inpatient site to one of the eight participating SNFs or LTACHs, from either a medical or surgical service, are eligible to be discussed at this weekly interdisciplinary conference. Long-term care facilities were not included in this study. The ECHO-CT program used HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act)-compliant videoconferencing technology to connect hospital and post–acute care providers.

During the videoconferences, each patient’s hospital course and discharge documentation are reviewed by a hospitalist, and a pharmacist performs a medication reconciliation of each patient’s admission, discharge, and post–acute care medication list. The discharging attending, primary care providers, residents, other trainees, and subspecialist providers are invited to attend. Typically, the interdisciplinary team at the post–acute care sites includes physicians, nurse practitioners, physical therapists, social workers, and case managers. Between 10 and 20 patients are discussed in a case-based format, which includes a summary of the patient’s hospital course, an update from the post–acute care team on the patient’s care, and an opportunity for a discussion regarding any concerns or questions raised by the post–acute care or inpatient care teams. The content and duration of discussion typically lasts approximately 3 to 10 minutes, depending on the needs of the patient and the care team. Each of the eight post–acute care sites participating in the project are assigned a 10- to 15-minute block. A copy of the ECHO-CT session process document is included in the Appendix.

Data Collection

At each interdisciplinary patient review, TCEs were identified and recorded. These events were categorized in real time by the ECHO-CT data collection team into the following categories: medication related, medical, discharge communication/coordination, or other, and recorded in a secured, deidentified database. For individuals whose TCEs could represent more than one category, authors reviewed the available information about the TCEs and determined the most appropriate category; if more than one category was felt to be applicable to a patient’s situation, the events were reclassified into all applicable categories. Data about individual patients, including gender, age at the time of discharge, and other demographic information, were obtained from hospital databases. Number of diagnoses included any diagnosis billed during the patient’s hospital stay, and these data were obtained from a hospital billing database. Average number of medications at discharge was obtained from a hospital pharmacy database.

RESULTS

A total of 675 patients (experiencing 743 hospitalizations) were discharged from a medical or surgical service to one of the participating post–acute care sites from January 2016 to October 2018, and were discussed at the interdisciplinary conference. During that time, 139 TCEs were recorded for review, involving 132 patients (Table 1). Patients who experienced TCEs were noted to have a slightly higher average number of diagnoses than did those in the non-TCE group (21 vs 18, respectively) and number of medications (18 vs 15).

Representative examples of TCEs are provided in Table 2. Fifty-eight issues were identified as discharge communication or coordination issues (eg, discharge summary was late or missing at time of discharge to facility, transitional issues were unclear, follow-up appointments were not appropriately scheduled or documented). An additional 52 TCEs were identified as pharmacy or medication issues (eg, medications were inadvertently omitted from discharge medication list, prehospital medication list was incorrect). Medical issues accounted for an additional 27 concerns (eg, patient was hypoglycemic on arrival, inadequate pain control, discovery of new acute medical issues or medical diagnoses that were not clearly documented or communicated by the inpatient team). “Other” issues (two) included unaddressed social concerns, such as insurance issues.

DISCUSSION

The ECHO-CT model unites hospital and post–acute care providers to improve transitions of care and is unique in its focus on the transition from hospital to post–acute care rather than to home care. In 2 years of data collection, we identified several TCEs encompassing a range of concerns. Of the 675 patients discussed, 132 (20%) were noted to have a TCE. When these percentages are applied to the 140 million Medicare hospital discharges that took place during 2000 to 2015, we would estimate nearly 5.5 million TCEs, or 375,000 TCEs per year, that may have affected this population.

The majority of TCEs were communication and coordination errors. Missing or incomplete discharge paperwork, inadequate documentation of inpatient care, and confusion about medical devices or postoperative needs (eg, slings, braces, wound care, drains) were commonly reported. Follow-up appointments with specialists were often not appropriately scheduled or communicated. This may have resulted from unstandardized discharge documentation and a lower priority given to documentation in the setting of multiple clinical demands (eg, direct patient care, complex care coordination, and clinical paperwork and charting). Studies have demonstrated that fewer than one-third of discharge summaries are received by outpatient providers before postdischarge follow-up, and additionally that nearly 40% of patients did not undergo recommended workups for medical issues identified during their hospital stay.7,8 All of this is problematic because appropriate documentation in discharge summaries is associated with a decreased risk of hospital readmission.9

Pharmacy issues were the second most common TCE identified. One member of the post–acute care team noted that “omissions, additions, and replacements” relating to medications were common occurrences. Additionally, it was noted that medications were inadvertently continued for longer than planned or not adjusted appropriately with changing clinical parameters, such as renal function. The results of our analysis are consistent with current literature, which suggests that up to 60% of all medication errors occur during the period surrounding transitions of care.10

There were several limitations to this investigation. Though recording of identified TCEs occurred in real time, analysis of these identified events occurred retrospectively; therefore, investigators had limited ability to retroactively review or recategorize recorded issues, which potentially could have resulted in misclassification or misinterpretation. Additionally, the data were intended to be descriptive; therefore, outcomes such as hospital readmission and patient harm could not be linked to specific TCEs. Furthermore, it is possible that events were not detected by either the postdischarge team or the hospital-based team and, therefore, not captured in this analysis. Further work would be helpful to determine the root causes underlying the identified issues in care transitions, with the goal of improving patient safety and avoiding preventable errors during transitions of care. Although there is comprehensive literature related to errors and medication-related adverse events,11 there is not a consensus of how to classify and report, in a standardized fashion, events arising during the transition period. A validated structure for systematically identifying, monitoring, recording, and reporting issues arising during care transitions will be critical in preventing errors and ensuring patient safety during this high-risk period.

CONCLUSION

Our model is a unique intervention that uses the expertise and engagement of an interdisciplinary team and seeks to identify and remedy issues arising during transitions of care—in real time—to prevent direct harm to vulnerable patients. We have already implemented interventions to improve care based on our experiences with this videoconference-based program. For example, direct feedback was given to discharging teams to improve the discharge summary and associated documentation, and changes to the medication-ordering system were implemented to address specific medication errors discovered. The TCEs identified in this investigation highlight specific areas for improvement with the goal of providing high-quality care for patients and seamless transitions to post–acute care. As health systems and hospitals face new challenges in communication and care coordination, especially due to the recent COVID-19 pandemic, the technology and communication methods used in the ECHO-CT model may become even more relevant for promoting clear communication and patient safety during transitions of care.

Acknowledgment

The ECHO CT team thanks Sabrina Carretie for her contributions in data collection and analysis.

As the population of the United States continues to age, hospitals are seeing an increasing number of older patients with significant medical and social complexity. Medicare data have shown that an increasing number require post–acute care after a hospitalization.1 Discharges to post–acute care settings are often longer and more costly compared with discharges to other settings, which suggests that targeting quality improvement efforts at this transition period may improve the value of care.2

The transition from the hospital setting to a post–acute care facility can be dangerous and complicated due to lapses in communication, medication errors, and the complexity of medical treatment plans. Suboptimal transitions in care can result in adverse events for the patient, as well as confusion in medication regimens or incomplete plans for follow-up care.3

The Project ECHO (Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes) model was first developed and launched by Sanjeev Arora, MD, in New Mexico in 2003 to expand access to subspecialist care using videoconferencing.4 We first applied this model in 2013 to evaluate the impact of this interdisciplinary videoconferencing tool on the care of patients discharged to post–acute settings.5 We found that patients participating in the Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes–Care Transitions (ECHO-CT) model experienced decreased risk of rehospitalization, decreased skilled nursing facility (SNF) length of stay, and reduced 30-day healthcare costs, compared with those patients not enrolled in this program; these outcomes were likely due to identification and correction of medication-related errors, improved care coordination, improved disease management, and clarification of goals of care.6 Though these investigations did identify some issues arising during the care transition process, they did not fully describe the types of problems uncovered. We sought to better characterize the clinical and operational issues identified through the ECHO-CT conference, hereafter known as transition-of-care events (TCEs). These issues may include new or evolving medical concerns, an adverse event, or a “near miss.” Identification and classification of TCEs that may contribute to unsafe or fractured care transitions are critical in developing systematic solutions to improve transitions of care, which can ultimately improve patient safety and potentially avoid preventable errors.

METHODS

ECHO-CT Multidisciplinary Video Conference

We conducted ECHO-CT at a large, tertiary care academic medical center. The project design for the ECHO-CT program has been previously described.5 In brief, the program is a weekly, multidisciplinary videoconference between a hospital-based team and post–acute care providers to discuss patients discharged from inpatient services to post–acute care sites, including SNFs and long-term acute care hospitals (LTACHs), during the preceding week. All patients discharged from the tertiary care inpatient site to one of the eight participating SNFs or LTACHs, from either a medical or surgical service, are eligible to be discussed at this weekly interdisciplinary conference. Long-term care facilities were not included in this study. The ECHO-CT program used HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act)-compliant videoconferencing technology to connect hospital and post–acute care providers.

During the videoconferences, each patient’s hospital course and discharge documentation are reviewed by a hospitalist, and a pharmacist performs a medication reconciliation of each patient’s admission, discharge, and post–acute care medication list. The discharging attending, primary care providers, residents, other trainees, and subspecialist providers are invited to attend. Typically, the interdisciplinary team at the post–acute care sites includes physicians, nurse practitioners, physical therapists, social workers, and case managers. Between 10 and 20 patients are discussed in a case-based format, which includes a summary of the patient’s hospital course, an update from the post–acute care team on the patient’s care, and an opportunity for a discussion regarding any concerns or questions raised by the post–acute care or inpatient care teams. The content and duration of discussion typically lasts approximately 3 to 10 minutes, depending on the needs of the patient and the care team. Each of the eight post–acute care sites participating in the project are assigned a 10- to 15-minute block. A copy of the ECHO-CT session process document is included in the Appendix.

Data Collection

At each interdisciplinary patient review, TCEs were identified and recorded. These events were categorized in real time by the ECHO-CT data collection team into the following categories: medication related, medical, discharge communication/coordination, or other, and recorded in a secured, deidentified database. For individuals whose TCEs could represent more than one category, authors reviewed the available information about the TCEs and determined the most appropriate category; if more than one category was felt to be applicable to a patient’s situation, the events were reclassified into all applicable categories. Data about individual patients, including gender, age at the time of discharge, and other demographic information, were obtained from hospital databases. Number of diagnoses included any diagnosis billed during the patient’s hospital stay, and these data were obtained from a hospital billing database. Average number of medications at discharge was obtained from a hospital pharmacy database.

RESULTS

A total of 675 patients (experiencing 743 hospitalizations) were discharged from a medical or surgical service to one of the participating post–acute care sites from January 2016 to October 2018, and were discussed at the interdisciplinary conference. During that time, 139 TCEs were recorded for review, involving 132 patients (Table 1). Patients who experienced TCEs were noted to have a slightly higher average number of diagnoses than did those in the non-TCE group (21 vs 18, respectively) and number of medications (18 vs 15).

Representative examples of TCEs are provided in Table 2. Fifty-eight issues were identified as discharge communication or coordination issues (eg, discharge summary was late or missing at time of discharge to facility, transitional issues were unclear, follow-up appointments were not appropriately scheduled or documented). An additional 52 TCEs were identified as pharmacy or medication issues (eg, medications were inadvertently omitted from discharge medication list, prehospital medication list was incorrect). Medical issues accounted for an additional 27 concerns (eg, patient was hypoglycemic on arrival, inadequate pain control, discovery of new acute medical issues or medical diagnoses that were not clearly documented or communicated by the inpatient team). “Other” issues (two) included unaddressed social concerns, such as insurance issues.

DISCUSSION

The ECHO-CT model unites hospital and post–acute care providers to improve transitions of care and is unique in its focus on the transition from hospital to post–acute care rather than to home care. In 2 years of data collection, we identified several TCEs encompassing a range of concerns. Of the 675 patients discussed, 132 (20%) were noted to have a TCE. When these percentages are applied to the 140 million Medicare hospital discharges that took place during 2000 to 2015, we would estimate nearly 5.5 million TCEs, or 375,000 TCEs per year, that may have affected this population.

The majority of TCEs were communication and coordination errors. Missing or incomplete discharge paperwork, inadequate documentation of inpatient care, and confusion about medical devices or postoperative needs (eg, slings, braces, wound care, drains) were commonly reported. Follow-up appointments with specialists were often not appropriately scheduled or communicated. This may have resulted from unstandardized discharge documentation and a lower priority given to documentation in the setting of multiple clinical demands (eg, direct patient care, complex care coordination, and clinical paperwork and charting). Studies have demonstrated that fewer than one-third of discharge summaries are received by outpatient providers before postdischarge follow-up, and additionally that nearly 40% of patients did not undergo recommended workups for medical issues identified during their hospital stay.7,8 All of this is problematic because appropriate documentation in discharge summaries is associated with a decreased risk of hospital readmission.9

Pharmacy issues were the second most common TCE identified. One member of the post–acute care team noted that “omissions, additions, and replacements” relating to medications were common occurrences. Additionally, it was noted that medications were inadvertently continued for longer than planned or not adjusted appropriately with changing clinical parameters, such as renal function. The results of our analysis are consistent with current literature, which suggests that up to 60% of all medication errors occur during the period surrounding transitions of care.10

There were several limitations to this investigation. Though recording of identified TCEs occurred in real time, analysis of these identified events occurred retrospectively; therefore, investigators had limited ability to retroactively review or recategorize recorded issues, which potentially could have resulted in misclassification or misinterpretation. Additionally, the data were intended to be descriptive; therefore, outcomes such as hospital readmission and patient harm could not be linked to specific TCEs. Furthermore, it is possible that events were not detected by either the postdischarge team or the hospital-based team and, therefore, not captured in this analysis. Further work would be helpful to determine the root causes underlying the identified issues in care transitions, with the goal of improving patient safety and avoiding preventable errors during transitions of care. Although there is comprehensive literature related to errors and medication-related adverse events,11 there is not a consensus of how to classify and report, in a standardized fashion, events arising during the transition period. A validated structure for systematically identifying, monitoring, recording, and reporting issues arising during care transitions will be critical in preventing errors and ensuring patient safety during this high-risk period.

CONCLUSION

Our model is a unique intervention that uses the expertise and engagement of an interdisciplinary team and seeks to identify and remedy issues arising during transitions of care—in real time—to prevent direct harm to vulnerable patients. We have already implemented interventions to improve care based on our experiences with this videoconference-based program. For example, direct feedback was given to discharging teams to improve the discharge summary and associated documentation, and changes to the medication-ordering system were implemented to address specific medication errors discovered. The TCEs identified in this investigation highlight specific areas for improvement with the goal of providing high-quality care for patients and seamless transitions to post–acute care. As health systems and hospitals face new challenges in communication and care coordination, especially due to the recent COVID-19 pandemic, the technology and communication methods used in the ECHO-CT model may become even more relevant for promoting clear communication and patient safety during transitions of care.

Acknowledgment

The ECHO CT team thanks Sabrina Carretie for her contributions in data collection and analysis.

1. Werner RM, Konetzka RT. Trends in post-acute care use among medicare beneficiaries: 2000 to 2015. JAMA. 2018;319(15):1616–1617. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.2408

2. Tian W. An All-Payer View of Hospital Discharge to Postacute Care, 2013. Statistical Brief #205. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; May 2016. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb205-Hospital-Discharge-Postacute-Care.pdf

3. Kessler C, Williams MC, Moustoukas JN, Pappas C. Transitions of care for the geriatric patient in the emergency department. Clin Geriatr Med. 2013;29(1):49-69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cger.2012.10.005

4. Arora S, Thornton K, Jenkusky SM, Parish B, Scaletti JV. Project ECHO: linking university specialists with rural and prison-based clinicians to improve care for people with chronic hepatitis C in New Mexico. Public Health Rep. 2007;122(Suppl 2):74-77. https://doi.org/10.1177/00333549071220s214

5. Farris G, Sircar M, Bortinger J, et al. Extension for community healthcare outcomes–care transitions: enhancing geriatric care transitions through a multidisciplinary videoconference. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(3):598-602. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.14690

6. Moore AB, Krupp JE, Dufour AB, et al. Improving transitions to postacute care for elderly patients using a novel video-conferencing program: ECHO-Care transitions. Am J Med. 2017;130(10):1199-1204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.04.041

7. Kripalani S, LeFevre F, Phillips CO, Williams MV, Basaviah P, Baker DW. Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA. 2007;297(8):831–841. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.297.8.831

8. Moore C, McGinn T, Halm E. Tying up loose ends: discharging patients with unresolved medical issues. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(12):1305-1311. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.167.12.1305

9. van Walraven C, Seth R, Austin PC, Laupacis A. Effect of discharge summary availability during post-discharge visits on hospital readmission. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(3):186-192. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10741.x

10. Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, Gandhi TK, Bates DW. The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(3):161-167. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-138-3-200302040-00007

11. Claeys C, Nève J, Tulkens PM, Spinewine A. Content validity and inter-rater reliability of an instrument to characterize unintentional medication discrepancies. Drugs Aging. 2012;29(7):577-591. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf03262275

1. Werner RM, Konetzka RT. Trends in post-acute care use among medicare beneficiaries: 2000 to 2015. JAMA. 2018;319(15):1616–1617. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.2408

2. Tian W. An All-Payer View of Hospital Discharge to Postacute Care, 2013. Statistical Brief #205. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; May 2016. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb205-Hospital-Discharge-Postacute-Care.pdf

3. Kessler C, Williams MC, Moustoukas JN, Pappas C. Transitions of care for the geriatric patient in the emergency department. Clin Geriatr Med. 2013;29(1):49-69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cger.2012.10.005

4. Arora S, Thornton K, Jenkusky SM, Parish B, Scaletti JV. Project ECHO: linking university specialists with rural and prison-based clinicians to improve care for people with chronic hepatitis C in New Mexico. Public Health Rep. 2007;122(Suppl 2):74-77. https://doi.org/10.1177/00333549071220s214

5. Farris G, Sircar M, Bortinger J, et al. Extension for community healthcare outcomes–care transitions: enhancing geriatric care transitions through a multidisciplinary videoconference. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(3):598-602. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.14690

6. Moore AB, Krupp JE, Dufour AB, et al. Improving transitions to postacute care for elderly patients using a novel video-conferencing program: ECHO-Care transitions. Am J Med. 2017;130(10):1199-1204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.04.041

7. Kripalani S, LeFevre F, Phillips CO, Williams MV, Basaviah P, Baker DW. Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA. 2007;297(8):831–841. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.297.8.831

8. Moore C, McGinn T, Halm E. Tying up loose ends: discharging patients with unresolved medical issues. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(12):1305-1311. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.167.12.1305

9. van Walraven C, Seth R, Austin PC, Laupacis A. Effect of discharge summary availability during post-discharge visits on hospital readmission. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(3):186-192. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10741.x

10. Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, Gandhi TK, Bates DW. The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(3):161-167. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-138-3-200302040-00007

11. Claeys C, Nève J, Tulkens PM, Spinewine A. Content validity and inter-rater reliability of an instrument to characterize unintentional medication discrepancies. Drugs Aging. 2012;29(7):577-591. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf03262275

© 2021 Society of Hospital Medicine

Inpatient management of opioid use disorder: A review for hospitalists

The United States is experiencing an epidemic of nonmedical opioid use. A concerted effort to better address pain increased the provision of prescription narcotics in the late 1990s and early 2000s.1 Since then, there has been significant growth of opioid use and acorresponding increase in overdose-related deaths.1-3 Public health officials have responded with initiatives to secure the opioid supply and improve outpatient treatment resources. However, the role of hospitalists in addressing opioid use disorder (OUD) is not well established. The inpatient needs for these individuals are complex and require a collaborative approach with input from outpatient clinicians, inpatient clinicians, addiction specialists, social workers, and case managers. Hospitals are often under-resourced to provide such comprehensive services. This frequently results in the hospitalist bearing significant responsibility for inpatient addiction management despite often insufficient addiction education or experience.4,5

Therefore, there is a need for hospitalists to become leaders in the inpatient management of OUD. In this review, we will discuss the hospitalist’s role in the inpatient management of individuals with OUD.

INPATIENT MANAGEMENT OF OPIOID USE DISORDER

Opioid use disorder is a medical illness resulting from neurobiological changes that cause drug tolerance, dependence, and cravings.6 It should be considered a treatable chronic medical condition, comparable to hypertension or diabetes,7 which requires a multifaceted treatment approach, including psychosocial, educational, and medical interventions.

Psychosocial Interventions

Individuals with OUD often have complicated social issues including stigmatization, involvement in the criminal justice system, unemployment, and homelessness,5,8-10 in addition to frequent comorbid mental health issues.11,12 Failure to address social or mental health barriers may lead to a lack of engagement in the treatment of OUD. The long-term management of OUD should involve outpatient psychotherapy and may include individual or group therapy, behavioral therapy, family counseling, or support groups.13 In the inpatient setting, hospitalists should use a collaborative approach to address psychosocial barriers. The authors recommend social work and case management consultations and consideration of psychiatric consultation when appropriate.

Management of Opioid Withdrawal

The prompt recognition and management of withdrawal is essential in hospitalized patients with OUD. The signs and symptoms of withdrawal can be evaluated by using the Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale or the Clinical Institute Narcotics Assessment, and may include lacrimation, rhinorrhea, diaphoresis, yawning, restlessness, insomnia, piloerection, myalgia, arthralgia, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.4 Individuals using short-acting opioids, such as oxycodone or heroin, may develop withdrawal symptoms 8 to 12 hours after cessation of the opioid. Symptoms often peak on days 1 to 3 and can last for up to 10 days.14 Individuals taking long-acting opioids, such as methadone, may experience withdrawal symptoms for up to 21 days.14

While the goal of withdrawal treatment is to reduce the uncomfortable symptoms of withdrawal, there may be additional benefits. Around 16% of people who inject drugs will misuse drugs during their hospitalization, and 25% to 30% will be discharged against medical advice.15,16 In hospitalizations when patients are administered methadone for management of withdrawal, there is a significant reduction in discharges against medical advice.16 This may suggest that treatment of withdrawal has the added benefit of preventing discharges against medical advice, and the authors postulate that treatment may decrease surreptitious drug use during hospitalizations, although this has not been studied.

There are 2 approaches to treating opioid withdrawal—opioid substitution treatment and alpha2-adrenergic agonist treatment (Table 1).4,17-20 Of note, opioid substitution treatment, especially when using buprenorphine, should be started only when a patient has at least mild withdrawal symptoms.20

An important exception to the treatment approach listed in Table 1 occurs when a patient is already taking methadone or buprenorphine maintenance therapy. In this circumstance, the outpatient dose should be continued after confirmation of dose and timing of last administration with outpatient clinicians. It is important that clear communication with the patient’s addiction clinician occurs at admission and discharge to prevent an inadvertently duplicated, or missed, dose.

Factors to consider when selecting a withdrawal treatment regimen include comorbidities, anticipated length of stay, anticipated discharge setting, medications, interest in long-term addiction treatment, and other patient-specific factors. In general, treatment with methadone or buprenorphine is preferred, because they are better tolerated and may be more effective than clonidine.21-24 The selection of methadone or buprenorphine is often based on physician or patient preference, presence of contraindications, or formulary restrictions, as they have similar efficacy in the treatment of opioid withdrawal.23 In cases where opioid replacement therapy is contraindicated, such as in an individual who has received naltrexone, clonidine should be used.24

Methadone and buprenorphine are controlled substances that can be prescribed only in outpatients by certified clinicians. Therefore, hospitalists are prohibited from prescribing these medications at discharge for the treatment of OUD. However, inpatient clinicians are exempt from these regulations and may provide both medications for maintenance and withdrawal treatment in the inpatient setting.

As such, while a 10 to 14-day taper may be optimal in preventing relapse and minimizing withdrawal, patients are often medically ready to leave the hospital before their taper is completed. In these cases, a rapid taper over 3 to 5 days can be considered. The disadvantage of a rapid taper is the potential for recrudescence of withdrawal symptoms after discharge. Individuals who do not tolerate a rapid taper should be treated with a slower taper, or transitioned to a clonidine taper.

Many hospitals have protocols to help guide the inpatient management of withdrawal, and in many cases, subspecialist consultation is not necessary. However, the authors recommend involvement of an addiction specialist for patients in whom management of withdrawal may be complicated. Further, we strongly encourage hospitalists to be involved in creation and maintenance of withdrawal treatment protocols.

Medication-Assisted Treatment

It is important to recognize that treatment of withdrawal is not adequate to prevent long-term opioid misuse.25 The optimal long-term management of OUD includes the use of medication-assisted treatment (MAT). The initiation and titration of MAT should always be done in conjunction with an addiction specialist or buprenorphine-waivered physician who will ensure continuation of MAT as an outpatient. This means that, while hospitalists may be critical in facilitating linkage to MAT, in general, they will not have a significant role in the long-term management of OUD. However, hospitalists should be knowledgeable about MAT because it is relatively common and can complicate hospitalizations.

There are two types of MAT: opioid-agonist treatment (OAT) and opioid-antagonist treatment. Opioid-agonist treatment involves the use of methadone, a long-acting opioid agonist, or buprenorphine, a long-acting partial opioid agonist. These medications decrease the amount and severity of cravings and limit the euphoric effects of subsequent opioid use.17 Compared to abstinence-based treatment, OAT has been associated with increased retention in addiction treatment and employment, and reductions in incarceration, human immunodeficiency virus transmission, illicit drug use, opioid-overdose events, and mortality.26-32An alternative to OAT is naltrexone, an opioid antagonist. Naltrexone for OUD is administered as a monthly depot injection that prevents the user from experiencing opioid intoxication or dependence, and is associated with sustained abstinence.17,33,34 The authors strongly recommend that hospitalists discuss the benefits of MAT with hospitalized individuals with OUD. In addition, when appropriate, patients should receive consultation with, or referral to, an addiction specialist.

Adverse Effects of Methadone, Buprenorphine, and Naltrexone

The benefits of MAT are substantial, but there are adverse effects, potential drug-to-drug interactions, and patient-specific characteristics that may impact the inpatient management of individuals on MAT. Selected adverse effects of OAT are listed in Table 1. The adverse effects of naltrexone include nausea, vomiting, and transaminitis. It should also be noted that the initiation of buprenorphine and naltrexone may induce opioid withdrawal when administered to an opioid-dependent patient with recent opioid use. To avoid precipitating withdrawal, buprenorphine should be used only in individuals who have at least mild withdrawal symptoms or have completed detoxification,20 and naltrexone should be used only in patients who have abstained from opioids for at least 7 to 10 days.35

Opioid-agonist treatments are primarily metabolized by the cytochrome P450 3A4 isoenzyme system. Medications that inhibit cytochrome P450 3A4 metabolism such as fluconazole can result in OAT toxicity, while medications that induce cytochrome P450 3A4 metabolism such as dexamethasone can lead to withdrawal symptoms.18 If these interactions are unavoidable, the dose of methadone or buprenorphine should be adjusted to prevent toxicity or withdrawal symptoms. The major drug interaction with naltrexone is ineffective analgesia from opioids.

Another major concern with MAT is the risk of overdose-related deaths. As an opioid agonist, large doses of methadone can result in respiratory depression, while buprenorphine alone, due to its partial agonist effect, is unlikely to result in respiratory depression. When methadone or buprenorphine are taken with other substances that cause respiratory depression, such as benzodiazepines or alcohol, the risk of respiratory depression and overdose is significantly increased.36,37 Overdose-related death with naltrexone usually occurs after the medication has metabolized and results from a loss of opioid tolerance.38

Special Populations

Medication-assisted treatment in individuals with acute pain. Maintenance treatment with OAT does not provide sufficient analgesia to treat episodes of acute pain.39 In patients on methadone maintenance, the maintenance dose should be continued and adjunctive analgesia should be provided with nonopioid analgesics or short-acting opioids.39 The management of acute pain in individuals on buprenorphine maintenance is more complicated since buprenorphine is a partial opioid agonist with high affinity to the opioid receptor, which limits the impact of adjunctive opioids. The options for analgesia in buprenorphine maintenance treatment include 1) continuing daily dosing of buprenorphine and providing nonopioid or opioid analgesics, 2) dividing buprenorphine dosing into a 3 or 4 times a day medication, 3) discontinuing buprenorphine and treating with opioid analgesics, 4) discontinuing buprenorphine and starting methadone with nonopioid or opioid analgesics.39 In cases where buprenorphine is discontinued, it should be restarted before discharge upon resolution of the acute pain episode. An individual with acute pain on naltrexone may require nonopioid analgesia or regional blocks. In these patients, adequate pain control may be challenging and require the consultation of an acute pain specialist.

Pregnant or breastfeeding individuals. Opioid misuse puts the individual and fetus at risk of complications, and abrupt discontinuation can cause preterm labor, fetal distress, or fetal demise.40 The current standard is to initiate methadone in consultation with an addiction specialist.40 There is evidence that buprenorphine can be used during pregnancy; however, buprenorphine-naloxone is discouraged.18,40 Of note, use of OAT in pregnancy can result in neonatal abstinence syndrome, an expected complication that can be managed by a pediatrician.40

Methadone and buprenorphine can be found in low concentrations in breast milk.41 However, according to the Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine’s clinical guidelines, women on stable doses of methadone and buprenorphine should be encouraged to breastfeed.41 Naltrexone enters breast milk and has potential adverse effects for the newborn. Either the mother should discontinue naltrexone or should not breastfeed.35

Treatment of polysubstance misuse. Individuals with OUD may also misuse other substances. The concomitant use of opioids and other central nervous system depressants, such as alcohol and benzodiazepines, is especially worrisome as they can potentiate respiratory depression. The presence of polysubstance misuse does not preclude the use of MAT for the treatment of OUD. In those with comorbid alcohol use disorder, the use of naltrexone may be appealing as it can treat both alcohol use disorder and OUD. Given the complexities of managing polysubstance misuse, addiction specialists should be involved in the care of these patients.42 In addition, patients should be educated on the risks of polysubstance misuse, especially when it involves 2 central nervous system depressants.

Comorbid medical disease. In general, medical comorbidities do not significantly affect the treatment of OUD; however, dysfunction of certain organ systems may necessitate a dose reduction or discontinuation of MAT. Severe liver disease may result in decreased hepatic metabolism of OAT.35,42 Prolonged QTc, or history of arrhythmia, may preclude the use of methadone.17,35,42 In addition, chronic hypercapnic respiratory failure or severe asthma may be contraindications for the use of methadone in an unmonitored setting.35 Kidney failure is not known to be a contraindication to MAT, and there is no consensus on the need for dose reduction of MAT with decreasing glomerular filtration rate; however, some authors recommend a 25% to 50% dose reduction of methadone when the glomerular filtration rate is less than 10 milliliters per minute.43 There is no such recommendation with buprenorphine, although it has not been adequately studied in individuals with renal failure. Close monitoring for evidence of toxicity is prudent in individuals on MAT with acute or chronic renal failure.35

Rural or resource-limited areas. There is a significant shortage of addiction treatment options in many regions of the United States. As of 2012, there were an estimated 2.3 million individuals with OUD; however, more than 1 million of these individuals do not have access to treatment.44 As a result, many addiction treatment programs have wait lists that can last months or even years.45 These shortages are especially apparent in rural areas, where individuals with OUD are particularly reliant upon buprenorphine treatment because of prohibitive travel times to urban-based programs.46 To address this problem, new models of care delivery are being developed, including models incorporating telemedicine to support rural primary care management of OUD.47

The Future of Medication-Assisted Treatment

Currently, MAT is initiated and managed by outpatient addiction specialists. However, evidence supports initiation of MAT as an inpatient.48 A recent study compared inpatient buprenorphine detoxification to inpatient buprenorphine induction, dose stabilization, and postdischarge linkage-of-care to outpatient opioid treatment clinics. Patients who received inpatient buprenorphine initiation and linkage-of-care had improved buprenorphine treatment retention and reported less illicit opioid use.48 The development of partnerships between hospitals, inpatient clinicians, and outpatient addiction specialists is essential and could lead to significant advances in treating hospitalized patients with OUD.

The initiation of MAT in hospitalized patients with immediate linkage-of-care shows great promise; however, at this point, the initiation of MAT should be done only in conjunction with addiction specialists in patients with confirmed outpatient follow-up. In cases where inpatient MAT initiation is pursued, education of staff including nurses and pharmacists is essential.

Harm Reduction Interventions

Ideally, management of OUD results in abstinence from opioid misuse; however, some individuals are not ready for treatment or, despite MAT, have relapses of opioid misuse. Given this, a secondary goal in the management of OUD is the reduction of harm that can result from opioid misuse.

Many individuals inject opioids, which is associated with increased rates of viral and bacterial infections secondary to nonsterile injection practices.49 Educating patients on sterile injection methods (Table 2),50 including the importance of sterile-injecting equipment and water, and cleaning the skin prior to injection, may mitigate the risk of infections and should be provided for all hospitalized people who inject drugs.

Syringe-exchange programs provide sterile-injecting equipment in exchange for used needles, with a goal of increasing access to sterile supplies and removing contaminated syringes from circulation.51 While controversial, these programs may reduce the incidence of human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis C virus, and hepatitis B virus.51

In addition, syringe-exchange programs often provide addiction treatment referrals, counseling, testing, and prevention education for human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis C virus, and sexually transmitted infections.49 In the United States, there are 226 programs in 33 states (see https://nasen.org/directory for a list of programs and locations. Inpatient clinicians should provide a list of local resources including syringe-exchange programs at the time of discharge for any people who inject drugs. In addition, individuals with OUD are at increased risk for overdose, especially in the postdischarge setting due to decreased opioid tolerance.52 In 2014, there were 28,647 opioid overdose-related deaths in the United States.2 To address this troubling epidemic, opioid overdose education and naloxone distribution has been championed to educate patients at risk of opioid overdose and potential first responders on how to counteract an overdose by using naloxone, an opioid antagonist (see Table 2 for more information on opioid overdose education). The use of opioid overdose education and naloxone distribution has been observed to reduce opioid overdose-related death rates.53

Hospitalists should provide opioid overdose education and naloxone to all individuals at risk of opioid overdose (including those with OUD), as well as potential first responders where the law allows (more information including individual state laws can be found at http://prescribetoprevent.org).20

Considerations at Discharge

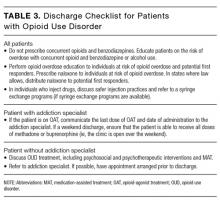

There are a number of considerations for the hospitalist at discharge (see Table 3 for a recommended discharge checklist). In addition, it is important to appreciate, and minimize, the ways that hospitalists contribute to the opioid epidemic. For instance, prescribing opioids at discharge in opioid-naïve patients increases the risk of chronic opioid use.54 It is also essential to recognize that increased doses of opioids are associated with increased rates of opioid overdose-related deaths.55 As such, hospitalists should maximize the use of nonopioid analgesics, prescribe opioids only when necessary, use the smallest effective dose of opioids, limit the number of opioid pills distributed to patients, and check prescription-monitoring programs for evidence of misuse.

CONCLUSION

Hospitalization serves as an important opportunity to address addiction in individuals with OUD. In addressing addiction, hospitalists should identify and intervene on psychosocial and mental health barriers, treat opioid withdrawal, and propagate harm reduction strategies. In addition, there is a growing role for hospitalists to be involved in the initiation of MAT and linkage-of-care to outpatient addiction treatment. If hospitalists become leaders in the inpatient management of OUD, they will significantly improve the care provided to this vulnerable patient population.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial conflicts of interest.

1. Hall AJ, Logan JE, Toblin RL, et al. Patterns of abuse among unintentional pharmaceutical overdose fatalities. JAMA. 2008;300(22):2613-2620. PubMed

2. Rudd RA, Aleshire N, Zibbell JE, Gladden RM. Increases in drug and opioid overdose deaths—United States, 2000-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;64(50-51):1378-1382. PubMed

3. Jones CM, Logan J, Gladden RM, Bohm MK. Vital signs: demographic and substance use trends among heroin users – United States, 2002-2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(26):719-725. PubMed

4. Haber PS, Demirkol A, Lange K, Murnion B. Management of injecting drug users admitted to hospital. Lancet. 2009;374(9697):1284-1293. PubMed

5. Miller NS, Sheppard LM, Colenda CC, Magen J. Why physicians are unprepared to treat patients who have alcohol- and drug-related disorders. Acad Med. 2001;76(5):410-418. PubMed

6. Cami J, Farré M. Drug addiction. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(10):975-986. PubMed

7. McLellan AT, Lewis DC, O’Brien CP, Kleber HD. Drug dependence, a chronic medical illness: implications for treatment, insurance and outcome evaluation. JAMA. 2000;284(13):1689-1695. PubMed

8. Reno RR, Aiken LS. Life activities and life quality of heroin addicts in and out of methadone treatment. Int J Addict. 1993;28(3):211-232. PubMed

9. Maddux JF, Desmond DP. Heroin addicts and nonaddicted brothers. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 1984;10(2):237-248. PubMed

10. Galea S, Vlahov D. Social determinants and the health of drug users; socioeconomic status, homelessness, and incarceration. Public Health Rep. 2002;117(suppl 1):S135-S145. PubMed

11. Brooner RK, King VL, Kidorf M, Schmidt CW Jr, Bigelow GF. Psychiatric and substance use comorbidity among treatment-seeking opioid abusers. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54(1):71-80. PubMed

12.Darke S, Ross J. Polydrug dependence and psychiatric comorbidity among heroin injectors. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1997;48(2):135-141. PubMed

13. Treating opiate addiction, Part II: alternatives to maintenance. Harv Ment Health Lett. 2005;21(7):4-6. PubMed

14. Choo C. Medications used in opioid maintenance treatment. US Pharm. 2009;34:40-53.

15. Marks M, Pollock E, Armstrong M, et al. Needles and the damage done: reasons for admission and financial costs associated with injecting drug use in a Central London teaching hospital. J Infect. 2012;66(1):95-102. PubMed

16. Chan AC, Palepu A, Guh DP, et al. HIV-positive injection drug users who leave the hospital against medical advice: the mitigating role of methadone and social support. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;35(1):56-59. PubMed

17. Strain E. Pharmacotherapy for opioid use disorder. In: UpToDate, Herman R, ed. UpToDate, Waltham, MA. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/pharmacotherapy-for-opioid-use-disorderAccessed September 28, 2015.

18. Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. Clinical guidelines for the use of buprenorphine in the treatment of opioid addiction. Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series 40. DHHS Publication No. (SMA) 04-3939. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2004. PubMed

19. Weaver MF, Hopper JA. Medically supervised opioid withdrawal during treatment for addiction. In: UpToDate, Herman R, ed. UpToDate, Waltham, MA. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/medically-supervised-opioid-withdrawal-during-treatment-for-addiction Accessed on September 28, 2015.

20. Kampman K, Jarvis M. American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) national practice guideline for the use of medications in the treatment of addiction involving opioid use. J Addict Med. 2015;9(5):358-367. PubMed

21. NICE Clinical Guidelines and National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health. Drug Misuse: Opioid Detoxification. British Psychological Society. 2008. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg52/evidence/drug-misuse-opioid-detoxification-full-guideline-196515037. Accessed April 12, 2017.

22. Amato L, Davoli M, Minozzi S, Ferroni E, Ali R, Ferri M. Methadone at tapered doses for the management of opioid withdrawal. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;2:CD003409. PubMed

23. Gowing L, Ali R, White J. Buprenorphine for the management of opioid withdrawal. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;3:CD002025. PubMed

24. Gowing L, Farrell M, Ali R, White JM. Alpha2-adrenergic agonists for the management of opioid withdrawal. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;5:CD002024. PubMed

25. Gossop M, Stewart D, Brown N, Marsden J. Factors associated with abstinence, lapse or relapse to heroin use after residential treatment: protective effect of coping responses. Addiction. 2002;97(10):1259-1267. PubMed

26. Farrell M, Ward J, Mattick R, et al. Methadone maintenance treatment in opiate dependence: a review. BMJ. 1994;309(6960):997-1001. PubMed

27. Connock M, Juarez Garcia A, Jowett S, et al. Methadone and buprenorphine for the management of opioid dependence: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2007;11(9):1–171. PubMed

28. Mattick RP, Breen C, Kimber J, Davoli M. Methadone maintenance therapy versus no opioid replacement therapy for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;3:CD002209. PubMed

29. Mattick RP, Breen C, Kimber J, Davoli M. Buprenorphine maintenance versus placebo or methadone maintenance for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2:CD002207. PubMed

30. Gowing LR, Farrell M, Bornemann R, Sullivan LE, Ali RL. Brief report: methadone treatment of injecting opioid users for prevention of HIV infection. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(2):193-195. PubMed

31. Nurco DN, Ball JC, Shaffer JW, Hanlon TE. The criminality of narcotic addicts. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1985;173(2):94-102. PubMed

32. Gibson A, Degenhardt L, Mattick RP, Ali R, White J, O’Brien S. Exposure to opioid maintenance treatment reduces long-term mortality. Addiction. 2008;103(3):462-468. PubMed

33. Minozzi S, Amato L, Vecchi S, Davoli M, Kirchmayer U, Verster A. Oral naltrexone maintenance treatment for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;4:CD001333. PubMed

34. Krupitsky E, Nunes EV, Ling W, Illeperuma A, Gastfriend DR, Silverman BL. Injectable extended-release naltrexone for opioid dependence: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;377(9776):1506-1513. PubMed

35. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Clinical Use of Extended-Release Injectable Naltrexone in the Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder: A Brief Guide. HHS Publication No. 14-4892R. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2015.

36. Caplehorn JR, Drummer OH. Fatal methadone toxicity: signs and circumstances, and the role of benzodiazepines. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2002;26(4):358-362. PubMed

37. Tracqui A, Kintz P, Ludes B. Buprenorphine-related deaths among drug addicts in France: a report on 20 fatalities. J Anal Toxicol. 1998;22(6):430-434. PubMed

38. Kelty E, Hulse G. Examination of mortality rates in a retrospective cohort of patients treated with oral or implant naltrexone for problematic opiate use. Addiction. 2012;107(1):1817-1824. PubMed

39. Alford DP, Compton P, Samet JH. Acute pain management for patients receiving maintenance methadone or buprenorphine therapy. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(2):127-134. PubMed

40. ACOG Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women: American Society of Addiction Medicine. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 524: Opioid abuse, dependence, and addiction in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119(5):1070-1076. PubMed

41. Reece-Stremtan S, Marinelli KA. ABM clinical protocol #21: guidelines for breastfeeding and substance use or substance use disorder, revised 2015. Breastfeed Med. 2015;10(3):135-141. PubMed

42. Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. Medication-Assisted Treatment for Opioid Addiction in Opioid Treatment Programs. Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series 43. HHS Publication No. 12-4214. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2005.

43. Brier ME, Aronoff GR (eds). Drug Prescribing in Renal Failure. 5thedition. Philadelphia, PA: American College of Physicians; 2007.

44. Jones CM, Campopiano M, Baldwin G, McCance-Katz E. National and state treatment need and capacity for opioid agonist medication-assisted treatment. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(8):e55-E63. PubMed

45. Sigmon SC. Access to treatment for opioid dependence in rural America: challenges and future directions. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(4):359-360. PubMed

46. Rosenblatt RA, Andrilla CH, Catlin M, Larson EH. Geographic and specialty distribution of US physicians trained to treat opioid use disorder. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13(1):23-26. PubMed

47. Komaromy M, Duhigg D, Metcalf A, et al. Project ECHO (Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes): A new model for educating primary care providers about treatment of substance use disorders. Subst Abus. 2016;37(1):20-24. PubMed

48. Liebschutz JM, Crooks D, Herman D, et al. Buprenorphine treatment for hospitalized, opioid-dependent patients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(8):1369-1376. PubMed

49. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Syringe exchange programs – United States, 2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59(45):1488-1491. PubMed

50. Harm Reduction Coalition. Getting off right: A safety manual for injection drug users. New York, NY: Harm Reduction Coalition; 1998.

51. Vlahov D, Junge B. The role of needle exchange programs in HIV prevention. Public Health Rep. 1998.113(suppl 1):75-80. PubMed

52. Strang J, McCambridge J, Best D, et al. Loss of tolerance and overdose mortality after inpatient opiate detoxification: follow up study. BMJ. 2003;326(7396):959-960. PubMed

53. Walley AY, Xuan Z, Hackman HH, et al. Opioid overdose rates and implementation of overdose education and nasal naloxone distribution in Massachusetts: interrupted time series analysis. BMJ. 2013;346:f174. PubMed

54. Calcaterra SL, Yamashita TE, Min SJ, Keniston A, Frank JW, Binswnager IA. Opioid prescribing at hospital discharge contributes to chronic opioid use. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(5):478-485. PubMed

55. Dunn KM, Saunders KW, Rutter CM, Banta-Green CJ, Merrill JO, Sullivan MD, et al. Opioid prescriptions for chronic pain and overdose: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(2):85-92. PubMed

The United States is experiencing an epidemic of nonmedical opioid use. A concerted effort to better address pain increased the provision of prescription narcotics in the late 1990s and early 2000s.1 Since then, there has been significant growth of opioid use and acorresponding increase in overdose-related deaths.1-3 Public health officials have responded with initiatives to secure the opioid supply and improve outpatient treatment resources. However, the role of hospitalists in addressing opioid use disorder (OUD) is not well established. The inpatient needs for these individuals are complex and require a collaborative approach with input from outpatient clinicians, inpatient clinicians, addiction specialists, social workers, and case managers. Hospitals are often under-resourced to provide such comprehensive services. This frequently results in the hospitalist bearing significant responsibility for inpatient addiction management despite often insufficient addiction education or experience.4,5

Therefore, there is a need for hospitalists to become leaders in the inpatient management of OUD. In this review, we will discuss the hospitalist’s role in the inpatient management of individuals with OUD.

INPATIENT MANAGEMENT OF OPIOID USE DISORDER

Opioid use disorder is a medical illness resulting from neurobiological changes that cause drug tolerance, dependence, and cravings.6 It should be considered a treatable chronic medical condition, comparable to hypertension or diabetes,7 which requires a multifaceted treatment approach, including psychosocial, educational, and medical interventions.

Psychosocial Interventions

Individuals with OUD often have complicated social issues including stigmatization, involvement in the criminal justice system, unemployment, and homelessness,5,8-10 in addition to frequent comorbid mental health issues.11,12 Failure to address social or mental health barriers may lead to a lack of engagement in the treatment of OUD. The long-term management of OUD should involve outpatient psychotherapy and may include individual or group therapy, behavioral therapy, family counseling, or support groups.13 In the inpatient setting, hospitalists should use a collaborative approach to address psychosocial barriers. The authors recommend social work and case management consultations and consideration of psychiatric consultation when appropriate.

Management of Opioid Withdrawal

The prompt recognition and management of withdrawal is essential in hospitalized patients with OUD. The signs and symptoms of withdrawal can be evaluated by using the Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale or the Clinical Institute Narcotics Assessment, and may include lacrimation, rhinorrhea, diaphoresis, yawning, restlessness, insomnia, piloerection, myalgia, arthralgia, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.4 Individuals using short-acting opioids, such as oxycodone or heroin, may develop withdrawal symptoms 8 to 12 hours after cessation of the opioid. Symptoms often peak on days 1 to 3 and can last for up to 10 days.14 Individuals taking long-acting opioids, such as methadone, may experience withdrawal symptoms for up to 21 days.14

While the goal of withdrawal treatment is to reduce the uncomfortable symptoms of withdrawal, there may be additional benefits. Around 16% of people who inject drugs will misuse drugs during their hospitalization, and 25% to 30% will be discharged against medical advice.15,16 In hospitalizations when patients are administered methadone for management of withdrawal, there is a significant reduction in discharges against medical advice.16 This may suggest that treatment of withdrawal has the added benefit of preventing discharges against medical advice, and the authors postulate that treatment may decrease surreptitious drug use during hospitalizations, although this has not been studied.

There are 2 approaches to treating opioid withdrawal—opioid substitution treatment and alpha2-adrenergic agonist treatment (Table 1).4,17-20 Of note, opioid substitution treatment, especially when using buprenorphine, should be started only when a patient has at least mild withdrawal symptoms.20