User login

An Officer and a Physician

Imagine being transferred to a hospital where the temperature is 20 below outside, and 40 inches of snow fill the parking lot. Few physicians would sign on for such an assignment. For a brave few, it’s all in a day’s work.

Maj. Ramey Wilson, MD, is a U.S. Army physician who encountered such conditions during his 15-month experience in Afghanistan. “A couple of times, when we couldn’t get helicopters [for evacuation], we had to turn my aid station into a mini-hospital. There were no nurses, labs, or X-ray,” he says. “With only basic supplies and my combat medics, we had to provide all the patient care until the weather broke.”

Not quite the circumstances most hospitalists encounter in their daily practice.

Hospitalists in the military face daunting odds, and at the same time are blessed with some unexpected advantages. On the plus side, military physicians cite the camaraderie, teamwork, honor of caring for soldiers, and the opportunity to train other providers, both in traditional, U.S.-based residencies and while deployed. Among the minuses, they mention a lack of equipment and supplies when they are assigned to forward-deployed soldiers on foreign soil, the heartache of being separated from family, and lower compensation. Most military physicians, however, say that the lower compensation can be offset by generous government benefits and the absence of medical school debt.

All in all, hospitalists in the military have a unique—and sometimes adventurous—story to tell.

Challenges Met, Success Exemplified

Dr. Wilson is a hospitalist and Army physician assigned to Fort Bragg, N.C. Until this past summer, he was the chief of internal medicine at Womack Army Medical Center, one of eight full-service hospitals in the U.S. Army Medical Command. Because the Army is still familiarizing itself with the HM model and the role hospitalists play in the delivery of healthcare, resident house staff meet many of the operational needs, including night and weekend coverage. “The Army doesn’t have a good system for 24-hour continuous care at busy hospitals without residents,” Dr. Wilson says, “and we’ve worked hard to get hospitalists into our system.”

While other Army medical centers have internal-medicine residencies, Womack has only a family medicine residency program. Residents once provided extensive coverage for the hospital, but decreasing numbers (only four interns this year) and work-hour restrictions have shifted the inpatient responsibilities to the internal-medicine staff. “All of the military general internists have functionally become hospitalists to support the inpatient medicine and ICU services,” Dr. Wilson says. “Our family medicine house staff coverage has evaporated.”

The conditions he sees at Womack are similar to what he sees at FirstHealth Moore Regional Hospital, the civilian community hospital in Pinehurst, N.C., where he practices part time. Womack serves two major military populations: those on active duty and their family members, and those no longer on active duty or retired (and not a part of the Veterans Administration program).

—Col. Walt Franz, MD, U.S. Army Medical Corps, Amarah/Al Kut, Iraq

Dr. Wilson, who served in the Ghazni province in eastern Afghanistan, was the only American physician in an area of 8,800 square miles. He and his physician-assistant staff were tasked with keeping U.S. soldiers healthy, serving acute resuscitative trauma care and “basic sick call.” In addition to caring for U.S. and coalition soldiers, he partnered with the Ghazni Ministry of Health to improve the delivery of healthcare to residents of the province.

“Afghanistan has a great plan for medical care through its ‘basic’ package of health services and ‘essential’ package hospital services, developed with assistance from the U.S. Agency for International Development [USAID], and which we used as our road map for the Afghan public health service,” Dr. Wilson says. He and a nurse practitioner from the nearby provincial reconstruction team worked out of a forward operating base outside Ghazni’s provincial capital—the city of Ghazni—and the nearby provincial hospital. He says his hospitalist background was helpful when it came to working with and teaching the Afghan physicians and nurses at the hospital, which served as the referral center for several surrounding provinces.

“There was no infection-control program; their hospital and clinics were heated by wood stoves; and they were using the one endotracheal tube that had been left by the International Red Cross years earlier,” he says, noting that during his tour, the U.S. military dropped basic medical equipment and supplies—which were shared with the local hospital—into his forward operating base. “They were doing anesthesia without monitors. We trained them with an initial focus of making surgery safer. … To say that it was challenging is an understatement, and for many different reasons.”

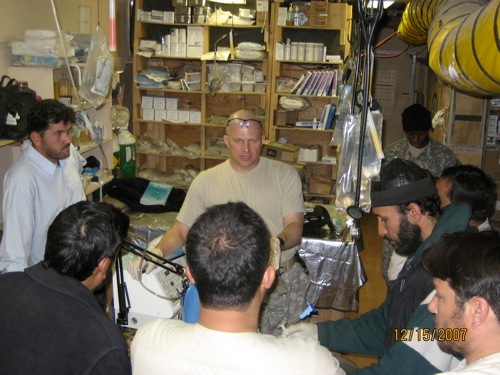

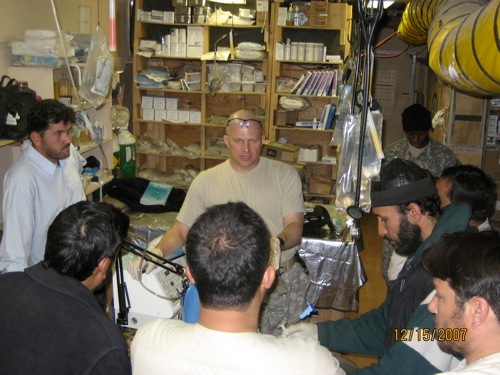

Almost every other week, Dr. Wilson hosted a medical conference at his base for 10 to 20 Afghan physicians. Due to local customs, female providers were not allowed to travel without a male relative, so Dr. Wilson’s team videotaped the classes, had them translated into the Pashto language, and arranged with the hospital directors to distribute them to female physicians.

The needs in both army and civilian circumstances are huge in Afghanistan. Most Afghan hospitals and clinics are without Internet access, so decision support and telemedicine consultative service is out of the question. Textbooks are in short supply, too. Because the Taliban decreed that no image of a human being is allowed in print, they confiscated and destroyed all of the country’s anatomy books.

In terms of training, the key to success with locals is demonstrating what success can look like.

“Most of these providers have practiced in a system that they think is as good as it can be given the lack of advanced machinery and equipment,” Dr. Wilson says.

Physicians who visit U.S. military or Western hospitals and witness the successes possible in infection control, nursing care, medication administration, and medical documentation return to Afghanistan excited about the skills introduced to them. “They see that the provision of really good medical care is more dependent on having a clean space, a well-organized system, good communication, and solid basic medical care,” Dr. Wilson says.

Contrast to Care Continuity

Col. Walt Franz, MD, of U.S. Army Medical Corps headquartered in Amarah/Al Kut, Iraq, has just begun the work of partnering with Iraqi physicians and nurses for the first time since 2003. In 2004, as a public health team leader, his primary task was helping Iraqi providers with hospital and clinic projects. The projects ranged in cost from $40,000 (for securing an X-ray machine) to $5,000 for such smaller repairs and fix-ups as securing parts to make an elevator run. In fact, patients were being carried up several flights of stairs in the local, six-story hospital.

For about five months in 2008, Dr. Franz was deputy commander for clinical services for hospital and outpatient medical care at a combat support hospital. Since the beginning of 2009, he has been the commander of the 945th Forward Surgical Team at a small forward base in Amarah, near the Iraq-Iran border. “Our mission here is to provide urgent surgical resuscitation for the critically wounded and evac[uation] by helo [helicopter],” Dr. Franz says.

When he’s at home and working at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., he practices primarily as a family physician. With nearly 30 years of clinical practice under his belt, Dr. Franz also puts in plenty of hours as a hospitalist. He has practiced during four deployments: three to Iraq and one to Germany.

“Active duty in a war zone presents experiences ranging from the inspiring to the absolutely tragic,” Dr. Franz says. “There is nothing worse than a casualty coming in on a medevac. It’s someone’s son or daughter or husband or wife, and nothing approaches the joy of helping a soldier. In fact, as a civilian, we scrupulously follow the Geneva Convention requirements.” (The treaty affords wounded and sick soldiers to be cared for and protected even though they may become prisoners of war.)

After you eliminate the dangers of enemy fire, there are still big differences between combat versus civilian medicine, he says. One is that combat medicine is usually acute care with little or no followup in the theater of operation, Dr. Franz says. Combat medicine has a strong foundation in echelons of care and evacuations away from the initial point of care. It runs concurrent to the civilian premise of continuity, and the limited number of specialists in theater usually means the Army relies on evacuation or electronic consults.

Maysan Province, where Dr. Franz is stationed, is the poorest part of Iraq. Because of its large Shia population, its citizens were devastated during the Iran-Iraq war and brutalized by Saddam Hussein. “The docs here are very street-smart; their work ethic is great and they have done without for a long time,” Dr. Franz says. Providers at the 540-bed hospital in Al Amarah see 200 patients per day in the ED; several hundred outpatients are triaged, and senior staff physicians see 75 or more cases daily. “One young doc told me it was not unusual to have 500 patients present to a regional ED in a 24-hour period, making triage and care almost overwhelming,” he says.

The biggest problem Dr. Franz witnesses in Iraqi hospitals is the lack of specialty nurses. His teams are teaching classes and training trainers in ED triage, basic ICU care, and the ultrasound FAST (Focused Assessment with Sonography in Trauma) exam skills Iraqi providers can use anywhere in the hospital.

Other issues include a lack of continuing medical education; poor infrastructure, which chokes the supply of pharmaceuticals and other medical equipment; and paucity of specialty nursing. Dr. Franz also cites critical staffing issues, such as the large number of physicians who have fled the country and the rising prominence of the private, fee-for-service care system, which can attract physicians and nurses away from the public system.

Care for Female Soldiers

With three other OB hospitalists, also known as laborists, Brook Thomson, MD, spent the summer organizing an OB/GYN hospital medicine program at Saint Alphonsus Regional Medical Center in Boise, Idaho. A veteran of military medicine, Dr. Thomson trained at Uniformed Services University of Health Sciences (USUHS) and completed an OB/GYN residency in 1997, then was stationed in Germany for four years. From 2001 to 2004, he served as chief of obstetrics at Madigan Army Medical Center in Tacoma, Wash., during which time he was deployed to Iraq for 10 months.

The OB/GYN expertise combined with the HM practice model that Dr. Thomson offers is a growing need in the military. “The number of women in the military is increasing, and there just aren’t a lot of people who understand female soldiers’ special needs,” he says.

Supporting women’s health has become an important aspect of battlefield medicine, namely the rooting out of potential sexual abuse. Dr. Thomson has published on the subject.1

In 2003, he was deployed as a general medical officer in Kuwait and assigned to the Basra area of Iraq, treating the gamut of patient needs. Recent Army policy changes, he says, ensure that OB/GYN military physicians now practice within their specialty.

A Canadian Perspective

Brendan James Hughes, MD, CCFP, returned from his military tour of duty and became a family practitioner in Lakefield, Ontario, a small community about 100 miles north of Toronto, and medical director of first-aid services for the Ontario Zone of the Canadian Red Cross.

In 2001, when Dr. Hughes was deployed as a hospitalist to Bosnia-Herzegovina for six months, the unrest from the civil war that involved Bosnians, Croatians, and Serbs (more than 100,000 were killed, and millions were injured or displaced), had settled, and his unit returned home without any loss of life. Upon his return, he transitioned from military life to become a full-time civilian hospitalist for six years in Ontario and Alberta. He now works as a part-time hospitalist.

Dr. Hughes says Canadian military practice is more acute and trauma-based now, as compared to his 2001 deployment in Eastern Europe. He notices many more deaths and major trauma cases in reports from Afghanistan, mostly blast injuries, limb amputations, and acute brain injuries, than there would be in a traditional, nonmilitary HM practice. He also notes that a lot of time and effort was placed on rehabilitation-focused practice that the patients required in the recovery phase.

Military practice differs from civilian hospitalist practice in other ways, he says. “In the military, every patient is essentially a workplace patient where the military is the employer,” Dr. Hughes says. Although clinicians maintain patient confidentiality, they are obliged to the chain of command to provide information on patient abilities. “We are careful not to relay a specific diagnosis without patient consent, but we have to dictate any needed restrictions on duty that are important in a combat situation, for themselves and for others,” he adds.

Such privacy and disclosure concerns are particularly difficult to navigate when it comes to diagnosis and treatment of alcohol and drug abuse, depression, post-traumatic stress, and suicide risk—issues that can lead soldiers to develop such long-term problems as substance abuse, marital discord, and marital abuse. TH

Andrea Sattinger is a freelance writer based in North Carolina.

Reference

- Thomson B, Nielsen P. Women’s healthcare in Operation Iraqi Freedom: a survey of camps with echelon one or two facilities. Mil Med. 2006;171:216-219.

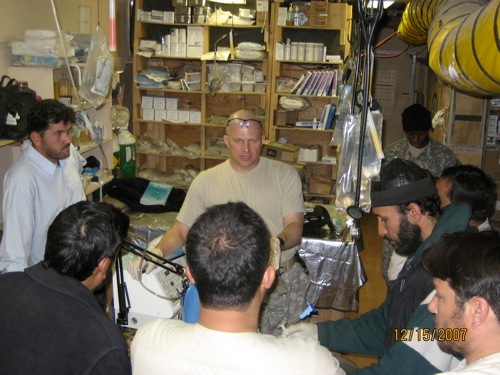

Dr. Wilson’s photos from Afghanistan

Click images to enlarge

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

PHOTOS COURTESY OF MAJ. RAMEY WILSON

Imagine being transferred to a hospital where the temperature is 20 below outside, and 40 inches of snow fill the parking lot. Few physicians would sign on for such an assignment. For a brave few, it’s all in a day’s work.

Maj. Ramey Wilson, MD, is a U.S. Army physician who encountered such conditions during his 15-month experience in Afghanistan. “A couple of times, when we couldn’t get helicopters [for evacuation], we had to turn my aid station into a mini-hospital. There were no nurses, labs, or X-ray,” he says. “With only basic supplies and my combat medics, we had to provide all the patient care until the weather broke.”

Not quite the circumstances most hospitalists encounter in their daily practice.

Hospitalists in the military face daunting odds, and at the same time are blessed with some unexpected advantages. On the plus side, military physicians cite the camaraderie, teamwork, honor of caring for soldiers, and the opportunity to train other providers, both in traditional, U.S.-based residencies and while deployed. Among the minuses, they mention a lack of equipment and supplies when they are assigned to forward-deployed soldiers on foreign soil, the heartache of being separated from family, and lower compensation. Most military physicians, however, say that the lower compensation can be offset by generous government benefits and the absence of medical school debt.

All in all, hospitalists in the military have a unique—and sometimes adventurous—story to tell.

Challenges Met, Success Exemplified

Dr. Wilson is a hospitalist and Army physician assigned to Fort Bragg, N.C. Until this past summer, he was the chief of internal medicine at Womack Army Medical Center, one of eight full-service hospitals in the U.S. Army Medical Command. Because the Army is still familiarizing itself with the HM model and the role hospitalists play in the delivery of healthcare, resident house staff meet many of the operational needs, including night and weekend coverage. “The Army doesn’t have a good system for 24-hour continuous care at busy hospitals without residents,” Dr. Wilson says, “and we’ve worked hard to get hospitalists into our system.”

While other Army medical centers have internal-medicine residencies, Womack has only a family medicine residency program. Residents once provided extensive coverage for the hospital, but decreasing numbers (only four interns this year) and work-hour restrictions have shifted the inpatient responsibilities to the internal-medicine staff. “All of the military general internists have functionally become hospitalists to support the inpatient medicine and ICU services,” Dr. Wilson says. “Our family medicine house staff coverage has evaporated.”

The conditions he sees at Womack are similar to what he sees at FirstHealth Moore Regional Hospital, the civilian community hospital in Pinehurst, N.C., where he practices part time. Womack serves two major military populations: those on active duty and their family members, and those no longer on active duty or retired (and not a part of the Veterans Administration program).

—Col. Walt Franz, MD, U.S. Army Medical Corps, Amarah/Al Kut, Iraq

Dr. Wilson, who served in the Ghazni province in eastern Afghanistan, was the only American physician in an area of 8,800 square miles. He and his physician-assistant staff were tasked with keeping U.S. soldiers healthy, serving acute resuscitative trauma care and “basic sick call.” In addition to caring for U.S. and coalition soldiers, he partnered with the Ghazni Ministry of Health to improve the delivery of healthcare to residents of the province.

“Afghanistan has a great plan for medical care through its ‘basic’ package of health services and ‘essential’ package hospital services, developed with assistance from the U.S. Agency for International Development [USAID], and which we used as our road map for the Afghan public health service,” Dr. Wilson says. He and a nurse practitioner from the nearby provincial reconstruction team worked out of a forward operating base outside Ghazni’s provincial capital—the city of Ghazni—and the nearby provincial hospital. He says his hospitalist background was helpful when it came to working with and teaching the Afghan physicians and nurses at the hospital, which served as the referral center for several surrounding provinces.

“There was no infection-control program; their hospital and clinics were heated by wood stoves; and they were using the one endotracheal tube that had been left by the International Red Cross years earlier,” he says, noting that during his tour, the U.S. military dropped basic medical equipment and supplies—which were shared with the local hospital—into his forward operating base. “They were doing anesthesia without monitors. We trained them with an initial focus of making surgery safer. … To say that it was challenging is an understatement, and for many different reasons.”

Almost every other week, Dr. Wilson hosted a medical conference at his base for 10 to 20 Afghan physicians. Due to local customs, female providers were not allowed to travel without a male relative, so Dr. Wilson’s team videotaped the classes, had them translated into the Pashto language, and arranged with the hospital directors to distribute them to female physicians.

The needs in both army and civilian circumstances are huge in Afghanistan. Most Afghan hospitals and clinics are without Internet access, so decision support and telemedicine consultative service is out of the question. Textbooks are in short supply, too. Because the Taliban decreed that no image of a human being is allowed in print, they confiscated and destroyed all of the country’s anatomy books.

In terms of training, the key to success with locals is demonstrating what success can look like.

“Most of these providers have practiced in a system that they think is as good as it can be given the lack of advanced machinery and equipment,” Dr. Wilson says.

Physicians who visit U.S. military or Western hospitals and witness the successes possible in infection control, nursing care, medication administration, and medical documentation return to Afghanistan excited about the skills introduced to them. “They see that the provision of really good medical care is more dependent on having a clean space, a well-organized system, good communication, and solid basic medical care,” Dr. Wilson says.

Contrast to Care Continuity

Col. Walt Franz, MD, of U.S. Army Medical Corps headquartered in Amarah/Al Kut, Iraq, has just begun the work of partnering with Iraqi physicians and nurses for the first time since 2003. In 2004, as a public health team leader, his primary task was helping Iraqi providers with hospital and clinic projects. The projects ranged in cost from $40,000 (for securing an X-ray machine) to $5,000 for such smaller repairs and fix-ups as securing parts to make an elevator run. In fact, patients were being carried up several flights of stairs in the local, six-story hospital.

For about five months in 2008, Dr. Franz was deputy commander for clinical services for hospital and outpatient medical care at a combat support hospital. Since the beginning of 2009, he has been the commander of the 945th Forward Surgical Team at a small forward base in Amarah, near the Iraq-Iran border. “Our mission here is to provide urgent surgical resuscitation for the critically wounded and evac[uation] by helo [helicopter],” Dr. Franz says.

When he’s at home and working at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., he practices primarily as a family physician. With nearly 30 years of clinical practice under his belt, Dr. Franz also puts in plenty of hours as a hospitalist. He has practiced during four deployments: three to Iraq and one to Germany.

“Active duty in a war zone presents experiences ranging from the inspiring to the absolutely tragic,” Dr. Franz says. “There is nothing worse than a casualty coming in on a medevac. It’s someone’s son or daughter or husband or wife, and nothing approaches the joy of helping a soldier. In fact, as a civilian, we scrupulously follow the Geneva Convention requirements.” (The treaty affords wounded and sick soldiers to be cared for and protected even though they may become prisoners of war.)

After you eliminate the dangers of enemy fire, there are still big differences between combat versus civilian medicine, he says. One is that combat medicine is usually acute care with little or no followup in the theater of operation, Dr. Franz says. Combat medicine has a strong foundation in echelons of care and evacuations away from the initial point of care. It runs concurrent to the civilian premise of continuity, and the limited number of specialists in theater usually means the Army relies on evacuation or electronic consults.

Maysan Province, where Dr. Franz is stationed, is the poorest part of Iraq. Because of its large Shia population, its citizens were devastated during the Iran-Iraq war and brutalized by Saddam Hussein. “The docs here are very street-smart; their work ethic is great and they have done without for a long time,” Dr. Franz says. Providers at the 540-bed hospital in Al Amarah see 200 patients per day in the ED; several hundred outpatients are triaged, and senior staff physicians see 75 or more cases daily. “One young doc told me it was not unusual to have 500 patients present to a regional ED in a 24-hour period, making triage and care almost overwhelming,” he says.

The biggest problem Dr. Franz witnesses in Iraqi hospitals is the lack of specialty nurses. His teams are teaching classes and training trainers in ED triage, basic ICU care, and the ultrasound FAST (Focused Assessment with Sonography in Trauma) exam skills Iraqi providers can use anywhere in the hospital.

Other issues include a lack of continuing medical education; poor infrastructure, which chokes the supply of pharmaceuticals and other medical equipment; and paucity of specialty nursing. Dr. Franz also cites critical staffing issues, such as the large number of physicians who have fled the country and the rising prominence of the private, fee-for-service care system, which can attract physicians and nurses away from the public system.

Care for Female Soldiers

With three other OB hospitalists, also known as laborists, Brook Thomson, MD, spent the summer organizing an OB/GYN hospital medicine program at Saint Alphonsus Regional Medical Center in Boise, Idaho. A veteran of military medicine, Dr. Thomson trained at Uniformed Services University of Health Sciences (USUHS) and completed an OB/GYN residency in 1997, then was stationed in Germany for four years. From 2001 to 2004, he served as chief of obstetrics at Madigan Army Medical Center in Tacoma, Wash., during which time he was deployed to Iraq for 10 months.

The OB/GYN expertise combined with the HM practice model that Dr. Thomson offers is a growing need in the military. “The number of women in the military is increasing, and there just aren’t a lot of people who understand female soldiers’ special needs,” he says.

Supporting women’s health has become an important aspect of battlefield medicine, namely the rooting out of potential sexual abuse. Dr. Thomson has published on the subject.1

In 2003, he was deployed as a general medical officer in Kuwait and assigned to the Basra area of Iraq, treating the gamut of patient needs. Recent Army policy changes, he says, ensure that OB/GYN military physicians now practice within their specialty.

A Canadian Perspective

Brendan James Hughes, MD, CCFP, returned from his military tour of duty and became a family practitioner in Lakefield, Ontario, a small community about 100 miles north of Toronto, and medical director of first-aid services for the Ontario Zone of the Canadian Red Cross.

In 2001, when Dr. Hughes was deployed as a hospitalist to Bosnia-Herzegovina for six months, the unrest from the civil war that involved Bosnians, Croatians, and Serbs (more than 100,000 were killed, and millions were injured or displaced), had settled, and his unit returned home without any loss of life. Upon his return, he transitioned from military life to become a full-time civilian hospitalist for six years in Ontario and Alberta. He now works as a part-time hospitalist.

Dr. Hughes says Canadian military practice is more acute and trauma-based now, as compared to his 2001 deployment in Eastern Europe. He notices many more deaths and major trauma cases in reports from Afghanistan, mostly blast injuries, limb amputations, and acute brain injuries, than there would be in a traditional, nonmilitary HM practice. He also notes that a lot of time and effort was placed on rehabilitation-focused practice that the patients required in the recovery phase.

Military practice differs from civilian hospitalist practice in other ways, he says. “In the military, every patient is essentially a workplace patient where the military is the employer,” Dr. Hughes says. Although clinicians maintain patient confidentiality, they are obliged to the chain of command to provide information on patient abilities. “We are careful not to relay a specific diagnosis without patient consent, but we have to dictate any needed restrictions on duty that are important in a combat situation, for themselves and for others,” he adds.

Such privacy and disclosure concerns are particularly difficult to navigate when it comes to diagnosis and treatment of alcohol and drug abuse, depression, post-traumatic stress, and suicide risk—issues that can lead soldiers to develop such long-term problems as substance abuse, marital discord, and marital abuse. TH

Andrea Sattinger is a freelance writer based in North Carolina.

Reference

- Thomson B, Nielsen P. Women’s healthcare in Operation Iraqi Freedom: a survey of camps with echelon one or two facilities. Mil Med. 2006;171:216-219.

Dr. Wilson’s photos from Afghanistan

Click images to enlarge

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

PHOTOS COURTESY OF MAJ. RAMEY WILSON

Imagine being transferred to a hospital where the temperature is 20 below outside, and 40 inches of snow fill the parking lot. Few physicians would sign on for such an assignment. For a brave few, it’s all in a day’s work.

Maj. Ramey Wilson, MD, is a U.S. Army physician who encountered such conditions during his 15-month experience in Afghanistan. “A couple of times, when we couldn’t get helicopters [for evacuation], we had to turn my aid station into a mini-hospital. There were no nurses, labs, or X-ray,” he says. “With only basic supplies and my combat medics, we had to provide all the patient care until the weather broke.”

Not quite the circumstances most hospitalists encounter in their daily practice.

Hospitalists in the military face daunting odds, and at the same time are blessed with some unexpected advantages. On the plus side, military physicians cite the camaraderie, teamwork, honor of caring for soldiers, and the opportunity to train other providers, both in traditional, U.S.-based residencies and while deployed. Among the minuses, they mention a lack of equipment and supplies when they are assigned to forward-deployed soldiers on foreign soil, the heartache of being separated from family, and lower compensation. Most military physicians, however, say that the lower compensation can be offset by generous government benefits and the absence of medical school debt.

All in all, hospitalists in the military have a unique—and sometimes adventurous—story to tell.

Challenges Met, Success Exemplified

Dr. Wilson is a hospitalist and Army physician assigned to Fort Bragg, N.C. Until this past summer, he was the chief of internal medicine at Womack Army Medical Center, one of eight full-service hospitals in the U.S. Army Medical Command. Because the Army is still familiarizing itself with the HM model and the role hospitalists play in the delivery of healthcare, resident house staff meet many of the operational needs, including night and weekend coverage. “The Army doesn’t have a good system for 24-hour continuous care at busy hospitals without residents,” Dr. Wilson says, “and we’ve worked hard to get hospitalists into our system.”

While other Army medical centers have internal-medicine residencies, Womack has only a family medicine residency program. Residents once provided extensive coverage for the hospital, but decreasing numbers (only four interns this year) and work-hour restrictions have shifted the inpatient responsibilities to the internal-medicine staff. “All of the military general internists have functionally become hospitalists to support the inpatient medicine and ICU services,” Dr. Wilson says. “Our family medicine house staff coverage has evaporated.”

The conditions he sees at Womack are similar to what he sees at FirstHealth Moore Regional Hospital, the civilian community hospital in Pinehurst, N.C., where he practices part time. Womack serves two major military populations: those on active duty and their family members, and those no longer on active duty or retired (and not a part of the Veterans Administration program).

—Col. Walt Franz, MD, U.S. Army Medical Corps, Amarah/Al Kut, Iraq

Dr. Wilson, who served in the Ghazni province in eastern Afghanistan, was the only American physician in an area of 8,800 square miles. He and his physician-assistant staff were tasked with keeping U.S. soldiers healthy, serving acute resuscitative trauma care and “basic sick call.” In addition to caring for U.S. and coalition soldiers, he partnered with the Ghazni Ministry of Health to improve the delivery of healthcare to residents of the province.

“Afghanistan has a great plan for medical care through its ‘basic’ package of health services and ‘essential’ package hospital services, developed with assistance from the U.S. Agency for International Development [USAID], and which we used as our road map for the Afghan public health service,” Dr. Wilson says. He and a nurse practitioner from the nearby provincial reconstruction team worked out of a forward operating base outside Ghazni’s provincial capital—the city of Ghazni—and the nearby provincial hospital. He says his hospitalist background was helpful when it came to working with and teaching the Afghan physicians and nurses at the hospital, which served as the referral center for several surrounding provinces.

“There was no infection-control program; their hospital and clinics were heated by wood stoves; and they were using the one endotracheal tube that had been left by the International Red Cross years earlier,” he says, noting that during his tour, the U.S. military dropped basic medical equipment and supplies—which were shared with the local hospital—into his forward operating base. “They were doing anesthesia without monitors. We trained them with an initial focus of making surgery safer. … To say that it was challenging is an understatement, and for many different reasons.”

Almost every other week, Dr. Wilson hosted a medical conference at his base for 10 to 20 Afghan physicians. Due to local customs, female providers were not allowed to travel without a male relative, so Dr. Wilson’s team videotaped the classes, had them translated into the Pashto language, and arranged with the hospital directors to distribute them to female physicians.

The needs in both army and civilian circumstances are huge in Afghanistan. Most Afghan hospitals and clinics are without Internet access, so decision support and telemedicine consultative service is out of the question. Textbooks are in short supply, too. Because the Taliban decreed that no image of a human being is allowed in print, they confiscated and destroyed all of the country’s anatomy books.

In terms of training, the key to success with locals is demonstrating what success can look like.

“Most of these providers have practiced in a system that they think is as good as it can be given the lack of advanced machinery and equipment,” Dr. Wilson says.

Physicians who visit U.S. military or Western hospitals and witness the successes possible in infection control, nursing care, medication administration, and medical documentation return to Afghanistan excited about the skills introduced to them. “They see that the provision of really good medical care is more dependent on having a clean space, a well-organized system, good communication, and solid basic medical care,” Dr. Wilson says.

Contrast to Care Continuity

Col. Walt Franz, MD, of U.S. Army Medical Corps headquartered in Amarah/Al Kut, Iraq, has just begun the work of partnering with Iraqi physicians and nurses for the first time since 2003. In 2004, as a public health team leader, his primary task was helping Iraqi providers with hospital and clinic projects. The projects ranged in cost from $40,000 (for securing an X-ray machine) to $5,000 for such smaller repairs and fix-ups as securing parts to make an elevator run. In fact, patients were being carried up several flights of stairs in the local, six-story hospital.

For about five months in 2008, Dr. Franz was deputy commander for clinical services for hospital and outpatient medical care at a combat support hospital. Since the beginning of 2009, he has been the commander of the 945th Forward Surgical Team at a small forward base in Amarah, near the Iraq-Iran border. “Our mission here is to provide urgent surgical resuscitation for the critically wounded and evac[uation] by helo [helicopter],” Dr. Franz says.

When he’s at home and working at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., he practices primarily as a family physician. With nearly 30 years of clinical practice under his belt, Dr. Franz also puts in plenty of hours as a hospitalist. He has practiced during four deployments: three to Iraq and one to Germany.

“Active duty in a war zone presents experiences ranging from the inspiring to the absolutely tragic,” Dr. Franz says. “There is nothing worse than a casualty coming in on a medevac. It’s someone’s son or daughter or husband or wife, and nothing approaches the joy of helping a soldier. In fact, as a civilian, we scrupulously follow the Geneva Convention requirements.” (The treaty affords wounded and sick soldiers to be cared for and protected even though they may become prisoners of war.)

After you eliminate the dangers of enemy fire, there are still big differences between combat versus civilian medicine, he says. One is that combat medicine is usually acute care with little or no followup in the theater of operation, Dr. Franz says. Combat medicine has a strong foundation in echelons of care and evacuations away from the initial point of care. It runs concurrent to the civilian premise of continuity, and the limited number of specialists in theater usually means the Army relies on evacuation or electronic consults.

Maysan Province, where Dr. Franz is stationed, is the poorest part of Iraq. Because of its large Shia population, its citizens were devastated during the Iran-Iraq war and brutalized by Saddam Hussein. “The docs here are very street-smart; their work ethic is great and they have done without for a long time,” Dr. Franz says. Providers at the 540-bed hospital in Al Amarah see 200 patients per day in the ED; several hundred outpatients are triaged, and senior staff physicians see 75 or more cases daily. “One young doc told me it was not unusual to have 500 patients present to a regional ED in a 24-hour period, making triage and care almost overwhelming,” he says.

The biggest problem Dr. Franz witnesses in Iraqi hospitals is the lack of specialty nurses. His teams are teaching classes and training trainers in ED triage, basic ICU care, and the ultrasound FAST (Focused Assessment with Sonography in Trauma) exam skills Iraqi providers can use anywhere in the hospital.

Other issues include a lack of continuing medical education; poor infrastructure, which chokes the supply of pharmaceuticals and other medical equipment; and paucity of specialty nursing. Dr. Franz also cites critical staffing issues, such as the large number of physicians who have fled the country and the rising prominence of the private, fee-for-service care system, which can attract physicians and nurses away from the public system.

Care for Female Soldiers

With three other OB hospitalists, also known as laborists, Brook Thomson, MD, spent the summer organizing an OB/GYN hospital medicine program at Saint Alphonsus Regional Medical Center in Boise, Idaho. A veteran of military medicine, Dr. Thomson trained at Uniformed Services University of Health Sciences (USUHS) and completed an OB/GYN residency in 1997, then was stationed in Germany for four years. From 2001 to 2004, he served as chief of obstetrics at Madigan Army Medical Center in Tacoma, Wash., during which time he was deployed to Iraq for 10 months.

The OB/GYN expertise combined with the HM practice model that Dr. Thomson offers is a growing need in the military. “The number of women in the military is increasing, and there just aren’t a lot of people who understand female soldiers’ special needs,” he says.

Supporting women’s health has become an important aspect of battlefield medicine, namely the rooting out of potential sexual abuse. Dr. Thomson has published on the subject.1

In 2003, he was deployed as a general medical officer in Kuwait and assigned to the Basra area of Iraq, treating the gamut of patient needs. Recent Army policy changes, he says, ensure that OB/GYN military physicians now practice within their specialty.

A Canadian Perspective

Brendan James Hughes, MD, CCFP, returned from his military tour of duty and became a family practitioner in Lakefield, Ontario, a small community about 100 miles north of Toronto, and medical director of first-aid services for the Ontario Zone of the Canadian Red Cross.

In 2001, when Dr. Hughes was deployed as a hospitalist to Bosnia-Herzegovina for six months, the unrest from the civil war that involved Bosnians, Croatians, and Serbs (more than 100,000 were killed, and millions were injured or displaced), had settled, and his unit returned home without any loss of life. Upon his return, he transitioned from military life to become a full-time civilian hospitalist for six years in Ontario and Alberta. He now works as a part-time hospitalist.

Dr. Hughes says Canadian military practice is more acute and trauma-based now, as compared to his 2001 deployment in Eastern Europe. He notices many more deaths and major trauma cases in reports from Afghanistan, mostly blast injuries, limb amputations, and acute brain injuries, than there would be in a traditional, nonmilitary HM practice. He also notes that a lot of time and effort was placed on rehabilitation-focused practice that the patients required in the recovery phase.

Military practice differs from civilian hospitalist practice in other ways, he says. “In the military, every patient is essentially a workplace patient where the military is the employer,” Dr. Hughes says. Although clinicians maintain patient confidentiality, they are obliged to the chain of command to provide information on patient abilities. “We are careful not to relay a specific diagnosis without patient consent, but we have to dictate any needed restrictions on duty that are important in a combat situation, for themselves and for others,” he adds.

Such privacy and disclosure concerns are particularly difficult to navigate when it comes to diagnosis and treatment of alcohol and drug abuse, depression, post-traumatic stress, and suicide risk—issues that can lead soldiers to develop such long-term problems as substance abuse, marital discord, and marital abuse. TH

Andrea Sattinger is a freelance writer based in North Carolina.

Reference

- Thomson B, Nielsen P. Women’s healthcare in Operation Iraqi Freedom: a survey of camps with echelon one or two facilities. Mil Med. 2006;171:216-219.

Dr. Wilson’s photos from Afghanistan

Click images to enlarge

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

PHOTOS COURTESY OF MAJ. RAMEY WILSON

ONLINE EXCLUSIVE: Training in Two Cultures: Medicine and Soldiering

Undergrads who choose the military and attend USUHS receive free tuition, books and other supplies; hand-held devices and related subscriptions, and basic medical equipment such as stethoscopes. In addition, USUHS medical students are paid as an active-duty second lieutenant (the going rate for the U.S. Army is about $1,900 per month).

Once they graduate, military residents work in uniform at military facilities and are afforded housing allowances. The government also covers the cost of medical malpractice insurance and supports them in any litigation while they are on active service. If they complete 20 years in active service, military physicians receive a generous retirement package, including a retained 40% to 50% pension for the rest of their lives, and they can seek work in the civilian sector after their military career.

For those who choose the military from the outset, the Department of Defense offers sign-on bonuses of $20,000 and a Health Service Professional Scholarship (HPSP) program for qualified applicants. It covers all medical school costs at a civilian medical school of the student’s choice. (Recent studies show the typical medical school grad has $120,000 of school load debt; $160,000 if they attended a private school.) The caveat is that after graduation, whether from USUHS or a civilian medical school, the physician works in uniform as a military physician for a pre-determined payback period (e.g., the Army obligation is one year of service for every year of scholarship).

The military offers training programs in medical, dental, optometry, veterinary, psychiatric nurse practitioner, and clinical and counseling psychology. Training at USUHS or with an HPSP requires each student before matriculation to choose his or her preferred branch of military service for the payback period. Whichever route a student takes, USUHS or HPSP, the student will end up as a doctor and a trained service member knowledgeable about areas including rank structure, military administration, and personal physical fitness.

Undergrads who choose the military and attend USUHS receive free tuition, books and other supplies; hand-held devices and related subscriptions, and basic medical equipment such as stethoscopes. In addition, USUHS medical students are paid as an active-duty second lieutenant (the going rate for the U.S. Army is about $1,900 per month).

Once they graduate, military residents work in uniform at military facilities and are afforded housing allowances. The government also covers the cost of medical malpractice insurance and supports them in any litigation while they are on active service. If they complete 20 years in active service, military physicians receive a generous retirement package, including a retained 40% to 50% pension for the rest of their lives, and they can seek work in the civilian sector after their military career.

For those who choose the military from the outset, the Department of Defense offers sign-on bonuses of $20,000 and a Health Service Professional Scholarship (HPSP) program for qualified applicants. It covers all medical school costs at a civilian medical school of the student’s choice. (Recent studies show the typical medical school grad has $120,000 of school load debt; $160,000 if they attended a private school.) The caveat is that after graduation, whether from USUHS or a civilian medical school, the physician works in uniform as a military physician for a pre-determined payback period (e.g., the Army obligation is one year of service for every year of scholarship).

The military offers training programs in medical, dental, optometry, veterinary, psychiatric nurse practitioner, and clinical and counseling psychology. Training at USUHS or with an HPSP requires each student before matriculation to choose his or her preferred branch of military service for the payback period. Whichever route a student takes, USUHS or HPSP, the student will end up as a doctor and a trained service member knowledgeable about areas including rank structure, military administration, and personal physical fitness.

Undergrads who choose the military and attend USUHS receive free tuition, books and other supplies; hand-held devices and related subscriptions, and basic medical equipment such as stethoscopes. In addition, USUHS medical students are paid as an active-duty second lieutenant (the going rate for the U.S. Army is about $1,900 per month).

Once they graduate, military residents work in uniform at military facilities and are afforded housing allowances. The government also covers the cost of medical malpractice insurance and supports them in any litigation while they are on active service. If they complete 20 years in active service, military physicians receive a generous retirement package, including a retained 40% to 50% pension for the rest of their lives, and they can seek work in the civilian sector after their military career.

For those who choose the military from the outset, the Department of Defense offers sign-on bonuses of $20,000 and a Health Service Professional Scholarship (HPSP) program for qualified applicants. It covers all medical school costs at a civilian medical school of the student’s choice. (Recent studies show the typical medical school grad has $120,000 of school load debt; $160,000 if they attended a private school.) The caveat is that after graduation, whether from USUHS or a civilian medical school, the physician works in uniform as a military physician for a pre-determined payback period (e.g., the Army obligation is one year of service for every year of scholarship).

The military offers training programs in medical, dental, optometry, veterinary, psychiatric nurse practitioner, and clinical and counseling psychology. Training at USUHS or with an HPSP requires each student before matriculation to choose his or her preferred branch of military service for the payback period. Whichever route a student takes, USUHS or HPSP, the student will end up as a doctor and a trained service member knowledgeable about areas including rank structure, military administration, and personal physical fitness.

The Big One

In March 2005 the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and the HHS Office of Public Health Emergency Preparedness published a report of guidelines for officials on how to plan for delivering health and medical care in a mass casualty event.1

After federal, state, and local authorities’ failure to supply desperately needed assistance following Hurricane Katrina, that report of recommendations from a 39-member panel of experts in bioethics, emergency medicine, emergency management, health administration, health law, and policy is more crucial than ever. This report offers a framework for providing optimal medical care during a potential bioterrorist attack or other public health emergency.

How well do you know your institutions’ plans and protocols for these types of events? How personally prepared are you and your families? Overall, what should your highest concerns be in order to prepare yourself now and in the future?

Definitions

The term disaster is defined many ways, but typically all definitions involve some sort of impact on the community and interruption of services from business as usual beyond the point where outside assistance is needed. Defining what is meant by a mass casualty incident (MCI), on the other hand, is more relative to the location in which it is being declared.

“Typically a mass casualty event is thought of as one in which the number of patients exceeds the amount of resources that are routinely available,” says Andrew Garrett, MD, FAAP, the director of disaster response and pediatric preparedness programs at the National Center for Disaster Preparedness at Columbia University’s Joseph L. Mailman School of Public Health, New York. “But that is a dynamic definition because in Chicago a bus accident with 15 patients might not be a mass casualty incident, but in rural Cody, Wyoming, a car accident with four people might be. It’s where you exceed the resources that are available locally that is important.”

The difference between an emergency, a disaster, or an MCI revolves more around semantics, the environment in which you will work, and the short-term goals of patient care. “We’re not asking people to reinvent the way in which they practice medicine,” says Dr. Garrett “but a disaster or MCI changes the paradigm in which they do it—to do the most good for the most people.”

Who’s in Charge?

The Hospital Emergency Incident Command System (HEICS) was adapted from a plan to coordinate and improve the safety of the wildland firefighting system in California. It was transitioned to serve as a model in hospitals to meet the same goals of staff accountability and safety during a disaster response. HEICS places one “incident commander” at the top of the pyramid in charge of all the separate areas of responsibility, such as logistics, finance, operations, medical care, safety, and so on.

“The way the system works,” says Dr. Garrett, “is that everyone working in a hospital response is supervised by only one person who answers to the command staff. The goal is that there’s one incident commander who knows everything that’s going on at the incident to avoid the trap of multiple people making command decisions at the same time.”

Redundant command structure is a common problem in a large-scale response to disaster. That was certainly the case in Hurricane Katrina, he says, where multiple agencies—federal, state, and local—did not follow this model of disaster response.

“It’s a simple concept,” says Dr. Garrett, “but unless responders practice it, it is difficult to utilize in a real emergency.”

Every hospital should have a HEICS or similar structure set up and the key emergency response roles pre-identified by job title, he says. And while knowledge of weapons of mass destruction (WMD) and incident command is improving, says Stephen V. Cantrill, MD, FACEP, associate director, Department of Emergency Medicine at Denver Health Medical Center, “Some hospitals have taken it seriously; others wish the whole thing would go away.”

More than likely, in the event of a disaster, the HEICS organizational tree is outlined all the way to the top commander in your hospital’s plan. Your role, in general, may have already been determined in this plan, but the conventional wisdom in your hospital (as in most) may be: You’ll learn your roles and responsibilities when the time comes. In fact, depending on your setting, the hospitalist may hold the most senior position in-house overnight or on the weekend—especially if there is not an emergency department at the hospital.

“The thing is, at first people are going to look to the most senior clinician to be in charge during a crisis,” says Dr. Garrett. Perhaps the smaller the hospital, the more you need to know what to do and what is expected of you to fit into the larger picture in the community. “And even if it is a smaller hospital the system and the needs are the same.”

What Types of Care?

Although many types of events can be handled the same way, some involve additional concerns. “With WMD or a contagious disease outbreak, there is the added issue of ‘What’s the risk to me as a provider in the hospital?’” says Dr. Garrett. “And if it’s a community or statewide or national event, ‘What’s the risk to my family?’ Then you’re dealing with issues that aren’t business as usual.”

The hospitalist and the administration will then have to think about other complex issues such as how many people are not going to come to work. Added to that, with a smaller staff, you may need to ask, “What will the scope of my practice be if I’m called to the front of the hospital to help do triage? Roles and responsibilities can change very quickly,” he says.

“Hospitalists are invaluable resources in an institution and in fact [in disaster events] they will be pressed into service because of their location,” says Dr. Cantrill, who with colleagues has trained 15,000 healthcare providers throughout Colorado as one of 17 centers to receive a three-year grant from the Health Resources Services Administration (HRSA) to conduct WMD training. “Especially in the private sector when it hits the fan, the hospitalist is going to be one of the first people to be called.”

In most disasters, the hospitalist’s medical practice will be a departure from the details of daily practice. “Because the majority of hospitalists have internal medicine as their background … they tend to be very detail oriented, which is really their strength,” says Dr. Cantrill. “But in a case like this, they may not have that luxury.”

Another major consideration and “probably the stickiest one,” is altering your standards of care in terms of providing efficiency care or austere care as opposed to what you normally consider appropriate medical care.

What hospitalists will do in any disaster depends on the event—natural, biological, chemical, or use of weaponry—and how your metropolitan or rural area is set up. If it is a biological or bioterrorist event, the pathogen involved may make a difference. Although anthrax is not contagious, for instance, in the event of a large-scale airborne anthrax attack, the need for ventilators will quickly overwhelm resources.2 “That’s one of our largest areas of vulnerability,” says Dr. Cantrill, “whether we’re talking influenza or pneumonic plague, it still is an important factor: How many people can I support?”

The issue of limited ventilators may not be completely soluble, he explains. In ordinary circumstances hospitals can get, say, ventilators from a strategic national stockpile from which equipment can be flown out within 12 hours. Yet if an influenza pandemic breaks out, then the entire country may be involved, rendering that plan inoperable. And even if you have extra ventilators, do you have extra respiratory techs to administer them?

Dr. Cantrill’s institution, with a grant received from HRSA, offers a two-hour course to train people with some medical knowledge to be respiratory assistants who can manage ventilated patients in an emergency.

Injuries may increase exponentially in the case of a disaster. Other needs include vaccinations, treatment for dehydration, serious heat- and cold-related illness, or threats from floodwater (i.e., water laced with toxic chemicals, human waste, fire ants, rats, and snakes).3

Kate Rathbun, MD, MPH, family physician in Baton Rouge, La., is certified in disaster management and knows well the problems that can arise in providing medical care in such an event.4 When Hurricane Katrina hit in 2005, everyone in range of the winds, rain, and destruction, “hunkered down to weather the storm.” The day after the storm, Dr. Rathbun joined other providers and administrators, opened their clinic, and readied themselves to treat trauma and lacerations. It soon became obvious that their biggest health issue was the inability of the displaced to manage their chronic diseases. (Baton Rouge’s normal population of 600,000 exceeded a million within days.)

In cases of diabetes, cardiac disease, HIV infection, or tuberculosis, for example, being without medications might mean lethal disease exacerbations.3 In many cases, patients have no prior history documentation on presentation, and with computers often shut down the provider is faced with prescribing for or actually putting a stock of medications into patients’ hands.

Additional concerns pertain to those who cannot receive hemodialysis or seizure prophylaxis; or disrupted care for those with special needs such as hospice patients, the mentally and physically disabled, the elderly, and individuals in detox programs.

When Dr. Rathbun and her coworkers put a couple of nurses on the phones to handle incoming requests for drugs, she gave them some standards: If it’s for chronic disease medications, prescribe a 30-day supply and three refills (to ensure that 30 days later they would not once again be inundated with calls). When patients requested narcotics or scheduled drugs, they were told they would have to be seen by a provider.

Branching Points and Skill Sets

What will your community expect your institution to respond to and provide in the event of disaster? Here is where hospitalists can delineate what they can do when the time comes, says Erin Stucky, MD, a pediatric hospitalist at Children’s Hospital, San Diego.

“Most disaster preparedness algorithms have roles based on ‘hospital-based providers,’” she says, “but when it comes down to medical administration, many of them stop at the emergency department.”

From that point on they are likely to say “I don’t know”—that is, the rest of that decision tree is left in the hands of whoever is in the lead positions of physician, administrator, and nurse.

“That’s where the hospitalist can say, ‘Let me tell you my skill set,’” says Dr. Stucky, such as “I can triage patients; I can help to coordinate and disseminate information or help to outside providers who are calling; I can help to coordinate provider groups to go to different areas within our hospital to coordinate staffing … because I know operating rooms or I know this subset of patient types.”

At some institutions where hospitalists have been around for a longer time the disaster plan’s algorithm has branching points that don’t end in the emergency department. “Each [branch] has separate blocks that are horizontally equivalent,” says Dr. Stucky, “and the bleed-down [recognizes] the hospitalist as the major ward medical officer responsible for ensuring that floor 6, that’s neuro, and floor 5, hem-onc, and so on, have the correct staffing and are responsible for people reporting to them as well as dividing them as a labor pool into who’s available to go where.”

In general, however, regardless of setting, she says, a “hospitalist knows intimately the structure of the hospital, the flow between units, and can help other patients to get to different parts of the institution where care is still safe, such as observation areas.”

Communications: Up and Down, Out and In

Part of the global-facility thought process must include what communications will be for everything from the county medical system and EMS response to, within an institution, the communication between floors and between people on horizontal lines of authority. In addition, information in and out of the hospital from workers to their families is crucial so that workers can concentrate on the tasks at hand.

Questions must be considered ahead of time: How do I communicate to those people outside whom I need to have come in? How do I get response to the appropriate people who are calling in to find out how many patients we’re caring for? There may be other calls from someone who says, for example, that the ventilator has stopped working for her elderly mother.

And hospitalists must also be ready to support the urgent care or primary care satellite clinics and communicate what’s going on at the hospital, says Dr. Rathbun, “so that someone like me, who is a primary care practitioner in the community, can know that if I call this number or this person, I’m going to be able to say, ‘I’m down here at the [clinic] and here’s what I’ve got,’ or “I know things are terrible, but I have a diabetic you had in the hospital three weeks ago who’s crashed again, and you’ve got to find him a bed.’”

Communication plans might include the provision of satellite phones or two-way radios, says Dr. Stucky, and this will affect concrete issues, such as staffing and allowances for who can come and leave.

“In our institution we make this [communication] a unit-specific responsibility of the nurse team leader,” she says. “The nurses each have a phone and those nurse phones are freed up for any person available on that unit to be used to communicate with the outside world.”

Personal Disaster Plans

“I think another vitally important—and I mean vital importance in the same manner as vital signs—is for each hospitalist to have a personal disaster plan for their family/personal life,” says Mitchell Wilson, MD, medical director, FirstHealth of the Carolinas Hospitalist Services and section chief of Hospital Medicine in the Department of Medicine at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. “As the front line ‘foot soldier,’ the potential to harm our families during a pandemic is enormous.”

Dr. Garrett agrees. “One of the things that we’re not so good at in this country is coming up with emergency plans for our own family—even those of us who are in the medical business and take care of others,” he says. “Taking this step just makes good sense—and serves to be able to maximize your own availability and also be confident that you have the ways and means to know that your family is safe and secure and given the best opportunity to survive in a disaster.”

According to Dr. Wilson, families with vulnerable members, such as the young, elderly, and infirm, must have a plan in place to minimize the risk to them. “The hospitalist who comes home sick [or] infected is a danger to the very safe place [to] which [hospitalists and their families] seek refuge,” he says.

Preparedness includes delineating in your family what your points of contact will be. “Part of the stress that’s involved in being a physician and being expected to report to work [may involve] worrying where your family is or whether they have a safe meeting place; who’s picking up the children from school; does the school for my children have a plan, etc.,” says Dr. Garrett.

If you know that your children’s school has an emergency plan, your spouse’s workplace has a plan, and any relative in a long-term care facility has a plan, you’ll be much more likely to stay on the job and care for patients.

“And if my child is on a school bus that needs to be evacuated somewhere out of town,” he says, “I want to know there’s a phone number that my whole family knows to reconnect somehow.”

No Assumptions

Losing utility power is always a concern in emergencies and disasters. “After 9/11 in New York City, lots of people flooded into emergency departments,” says Ann Waller, ScD, an associate professor in the Department of Emergency Medicine at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the UNC director for NC DETECT. (See “Disease Surveillance,” p. 20.)

“The emergency departments abandoned their electronic systems and went back to paper and pencil because it was faster to just do the bare minimum … and get them into each team than to enter all the information required,” she explains. “That was a real eye-opener for those of us who rely on electronic data.”

Preparing for crisis involves imagining the inaccessibility of all electronic communications and records, including data collection and surveillance, pharmacy, e-mail, and historical documentation and other medical records.

The general rule in disaster preparedness is to plan for 72-hour capacity: How and what do I need to exist for 72 hours? “And the standard is that you should try to do that for your average daily census plus 100 patients,” says Dr. Stucky.

Scheduling and staffing is another issue. “Be prepared to provide flex staffing and scheduling to provide surge capacity,” says Dr. Wilson.

Think on Your Feet: Training

If they are so inclined, hospitalists can become involved in disaster response, through disaster medical assistance teams, community emergency response teams, or through the Red Cross—to name a few. And there are plenty of ways to take advantage of free training, some of which provide CME.

Another important question to ask of your institution, says Dr. Stucky (who co-presented on the topic of disaster preparedness at this year’s SHM Annual Meeting) is whether they have run any mock disasters.

“You have to do that,” she says. “Half of disaster response is preparedness, but the other half is thinking on your feet. And there’s no way to do that without mocking a drill.”

While there can be value in computer-run mock-ups, “there’s nothing like doing it,” she says. “We learn at least 25 things every time we do it.” And though one drill does not a totally prepared institution make, “it does mean at least you have the right people in those strategic positions [and they] are people who can think on their feet.”

A valuable training resource from AHRQ is listed in the resources at the end of this article.5

Be Prepared

With the vast amount of information on disaster preparedness available, one clear goal is to narrow it to avoid feeling overwhelmed.

“I think that is a real challenge,” says Dr. Cantrill, “but the first step is the motivation to at least look.”

Take for example the motivation of a flu pandemic. “It’s going to happen sooner or later, one of these days, but we know it this time,” says Waller. “We have the ability to be more prepared. … This is a huge opportunity to see it coming and to do as much as we can [correctly]. Which is not to say we can avoid everything, but at least we can be as prepared as we’ve ever been able to be.”

Conclusion

For hospitalists, there are several key techniques for individuals to be able to increase their readiness for disaster in the workplace. The first is to avoid relying initially or entirely on external help to supply a response, says Dr. Garrett: “You are the medical response, and there may be a delay until outside assistance is available.”

A second key is to visualize—as well as possible—any circumstances you might face personally and professionally and to formulate questions, seek answers, and talk to colleagues and supervisors about what your role will be. A third factor is to participate in training in the form of drills and tabletop exercises for your hospital. An unpracticed disaster plan may be more dangerous than no plan at all. TH

Andrea Sattinger also writes the “Alliances” department in this issue.

References

- AHRQ. Altered Standards of Care in Mass Casualty Events. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; April 2005:Health Systems Research Inc. under Contract No. 290-04-0010.

- Hick JL, Hanfling D, Burstein JL, et al. Health care facility and community strategies for patient care surge capacity. Ann Emerg Med. 2004 Sep;44(3):253-261.

- Greenough PG, Kirsch TD. Hurricane Katrina. Public health response—assessing needs. N Engl J Med. 2005 Oct 13;353(15):1544-1546.

- Rathbun KC, Cranmer H. Hurricane Katrina and disaster medical care. N Engl J Med. 2006 Feb 16;354:772-773.

- Hsu EB, Jenckes MW, Catlett CL, et al. Training of hospital staff to respond to a mass casualty incident. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 95. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Prepared by the Johns Hopkins University Evidence-based Practice Center under Contract No. 290-02-0018; June 2004: AHRQ Publication No. 04-E015-2. Accessible at: www.ahrq.gov/downloads/pub/evidence/pdf/hospmci/hospmci.pdf. Last accessed June 1, 2006.

Resources

National Links

- Centers for Disease Control, Emergency Preparedness and Response: www.bt.cdc.gov/

- The Hospital Emergency Incident Command System (HEICS) is an emergency management system that employs a logical management structure, defined responsibilities, clear reporting channels, and a common nomenclature to help unify hospitals with other emergency responders: www.emsa.cahwnet.gov/dms2/heics3.htm

- State, local, and tribal public health departments have their own public health preparedness and response plans.

- The National Center for Environmental Health (NCEH): www.cdc.gov/nceh/emergency.htm.

- Two other CDC resources contain materials to address public health preparedness needs: the Division of Emergency and Environmental Health Services (EEHS) and the Environmental Public Health Readiness Branch (EPHRB). See all-hazards public health emergency response guide): www.cdc.gov/nceh/eehs/

- U.S. Department of Homeland Security, for family preparedness: www.ready.gov/

- AHRQ bioterrorism link: www.ahrq.gov/news/pubcat/c_biot.htm#biot002

- George Washington University Institute for Crisis, Disaster, and Risk Management offers programs, including training, in the area of crisis, emergency and risk management: www.gwu.edu/~icdrm/

- North Carolina Links—North Carolina Office of Public Health Preparedness and Response (NC PHPR): www.epi.state.nc.us/epi/phpr/provides information and resources regarding the threat of bioterrorism and other emerging infectious diseases within the state and around the nation.

- The Health Alert Network (HAN) system is designed to immediately alert key health officials and care providers in North Carolina to acts of bioterrorism as well as other types of emerging disease threats: www.nchan.org/

- DPH Immunization branch: www.immunizenc.com/

- State Web sites, such as San Diego Country Office of Emergency Systems: www.co.sandiego.ca.us/oes/ or the County of San Diego Health and Human Services Terrorism Preparedness: www.co.san-diego.ca.us/terrorism/links.html

In March 2005 the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and the HHS Office of Public Health Emergency Preparedness published a report of guidelines for officials on how to plan for delivering health and medical care in a mass casualty event.1

After federal, state, and local authorities’ failure to supply desperately needed assistance following Hurricane Katrina, that report of recommendations from a 39-member panel of experts in bioethics, emergency medicine, emergency management, health administration, health law, and policy is more crucial than ever. This report offers a framework for providing optimal medical care during a potential bioterrorist attack or other public health emergency.

How well do you know your institutions’ plans and protocols for these types of events? How personally prepared are you and your families? Overall, what should your highest concerns be in order to prepare yourself now and in the future?

Definitions

The term disaster is defined many ways, but typically all definitions involve some sort of impact on the community and interruption of services from business as usual beyond the point where outside assistance is needed. Defining what is meant by a mass casualty incident (MCI), on the other hand, is more relative to the location in which it is being declared.

“Typically a mass casualty event is thought of as one in which the number of patients exceeds the amount of resources that are routinely available,” says Andrew Garrett, MD, FAAP, the director of disaster response and pediatric preparedness programs at the National Center for Disaster Preparedness at Columbia University’s Joseph L. Mailman School of Public Health, New York. “But that is a dynamic definition because in Chicago a bus accident with 15 patients might not be a mass casualty incident, but in rural Cody, Wyoming, a car accident with four people might be. It’s where you exceed the resources that are available locally that is important.”

The difference between an emergency, a disaster, or an MCI revolves more around semantics, the environment in which you will work, and the short-term goals of patient care. “We’re not asking people to reinvent the way in which they practice medicine,” says Dr. Garrett “but a disaster or MCI changes the paradigm in which they do it—to do the most good for the most people.”

Who’s in Charge?

The Hospital Emergency Incident Command System (HEICS) was adapted from a plan to coordinate and improve the safety of the wildland firefighting system in California. It was transitioned to serve as a model in hospitals to meet the same goals of staff accountability and safety during a disaster response. HEICS places one “incident commander” at the top of the pyramid in charge of all the separate areas of responsibility, such as logistics, finance, operations, medical care, safety, and so on.

“The way the system works,” says Dr. Garrett, “is that everyone working in a hospital response is supervised by only one person who answers to the command staff. The goal is that there’s one incident commander who knows everything that’s going on at the incident to avoid the trap of multiple people making command decisions at the same time.”

Redundant command structure is a common problem in a large-scale response to disaster. That was certainly the case in Hurricane Katrina, he says, where multiple agencies—federal, state, and local—did not follow this model of disaster response.

“It’s a simple concept,” says Dr. Garrett, “but unless responders practice it, it is difficult to utilize in a real emergency.”

Every hospital should have a HEICS or similar structure set up and the key emergency response roles pre-identified by job title, he says. And while knowledge of weapons of mass destruction (WMD) and incident command is improving, says Stephen V. Cantrill, MD, FACEP, associate director, Department of Emergency Medicine at Denver Health Medical Center, “Some hospitals have taken it seriously; others wish the whole thing would go away.”

More than likely, in the event of a disaster, the HEICS organizational tree is outlined all the way to the top commander in your hospital’s plan. Your role, in general, may have already been determined in this plan, but the conventional wisdom in your hospital (as in most) may be: You’ll learn your roles and responsibilities when the time comes. In fact, depending on your setting, the hospitalist may hold the most senior position in-house overnight or on the weekend—especially if there is not an emergency department at the hospital.

“The thing is, at first people are going to look to the most senior clinician to be in charge during a crisis,” says Dr. Garrett. Perhaps the smaller the hospital, the more you need to know what to do and what is expected of you to fit into the larger picture in the community. “And even if it is a smaller hospital the system and the needs are the same.”

What Types of Care?

Although many types of events can be handled the same way, some involve additional concerns. “With WMD or a contagious disease outbreak, there is the added issue of ‘What’s the risk to me as a provider in the hospital?’” says Dr. Garrett. “And if it’s a community or statewide or national event, ‘What’s the risk to my family?’ Then you’re dealing with issues that aren’t business as usual.”

The hospitalist and the administration will then have to think about other complex issues such as how many people are not going to come to work. Added to that, with a smaller staff, you may need to ask, “What will the scope of my practice be if I’m called to the front of the hospital to help do triage? Roles and responsibilities can change very quickly,” he says.

“Hospitalists are invaluable resources in an institution and in fact [in disaster events] they will be pressed into service because of their location,” says Dr. Cantrill, who with colleagues has trained 15,000 healthcare providers throughout Colorado as one of 17 centers to receive a three-year grant from the Health Resources Services Administration (HRSA) to conduct WMD training. “Especially in the private sector when it hits the fan, the hospitalist is going to be one of the first people to be called.”

In most disasters, the hospitalist’s medical practice will be a departure from the details of daily practice. “Because the majority of hospitalists have internal medicine as their background … they tend to be very detail oriented, which is really their strength,” says Dr. Cantrill. “But in a case like this, they may not have that luxury.”

Another major consideration and “probably the stickiest one,” is altering your standards of care in terms of providing efficiency care or austere care as opposed to what you normally consider appropriate medical care.