User login

Stay Afloat

How does Martin Izakovic, MD, medical director of the hospitalist program at Mercy Hospital in Iowa City, Iowa, suggest keeping current with medical literature?

“Let your journals pile up in your office, including the free ones you never subscribed to, feel guilty about throwing any away, tell yourself you will get to them one day, and then watch as it almost never happens.”

Dr. Izakovic is kidding, of course, but it’s no joke trying to read the wealth of medical information published daily. In fact, some people call it impossible. So to stay afloat, many hospitalists go electronic or turn to journal clubs.

Electronic Resources to the Rescue

It’s not for lack of trying that you can’t get through all the literature out there. Most hospitalists we queried say they only skim through the major internal medicine-related journals, including the Annals of Internal Medicine, the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), The New England Journal of Medicine, Lancet, the Journal of General Internal Medicine, and the Journal of Hospital Medicine.

What really keeps hospitalists apprised of the latest medical news and research, they say, comes to them by way of the World Wide Web—straight to their inboxes. To start, many register for e-mails of journal tables of contents. Others subscribe to the American College of Physicians Journal Club, which reviews and critiques journal articles, rates the relevance of each article on a five-point scale, offers a customized literature updating service, and bundles mailings with the Annals.

Some physicians, like Leora Horwitz, MD, assistant professor in the division of General Internal Medicine at Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, only wish to receive information pertinent to specific topics. To make this happen, Dr. Horwitz sets up a search through Ovid or PubMed that runs about every two weeks and flags new articles that match her criteria.

“I only do this for absolutely key areas and I make the search criteria very restrictive so I only get one to two hits a month at most,” she says. “Then I set up an alert for one or two major articles in each field I am interested in.”

Dr. Horwitz also sets up alerts for her own published articles.

Hospitalists who work at academic institutions, in particular, are inundated with information via grand rounds, lectures, and formats for topics related to hospital medicine.

“We’ll take a list of top conditions relevant to our practice, to review as a working group and then take that to the rest of the group to decide how we’ll standardize care,” says Julia S. Wright, MD, director of hospital medicine and an associate professor of medicine at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison.

On top of setting up specific searches, many hospitalists use their institutions’ subscriptions to services such as:

- UpToDate, the evidence-based, peer-reviewed electronic resource for doctors;

- InfoPOEMs, Patient-Oriented Evidence that Matters from Essential Evidence Plus;

- Epocrates and Micromedex, for drug-related information;

- JournalWATCH;

- The Medical Letter;

- The Hospitalist’s “In the Literature” department; and

- PubMed.

Physicians each have their favorite subscription services. Bill Stinnette, MD, a hospitalist for the Permanente Medical Group, Inc. at Kaiser Permanente San Rafael Medical Center in northern California, recommends MedPage Today daily headlines online as “an excellent source for breaking news and studies, with subspecialty areas, interactive features, FDA alerts, and CME.”

Kenneth Patrick, MD, hospitalist and ICU director of Chestnut Hill Hospital in Philadelphia, uses Medscape as his main online update method. After having completed a personalized profile of his interests, Dr. Patrick now receives e-mail links and general articles based on his criteria. “There’s no paper, it’s done at a convenient time and location, you don’t have to remember where you put that journal you were reading when you were interrupted, and there’s online CME credits,” he says.

Gatherings Become Informative Discussions

Despite enthusiasm about getting information electronically, many hospitalists continue to benefit from—and enjoy—good old-fashioned journal clubs. For example, the quarterly “Lunch and Learn” at the Hospital of St. Raphael in New Haven, Conn., developed by hospitalist Ilona Figura, MD, “has been a real hit,” says Steven Angelo, MD, director of hospitalist services there.

“On a rotating basis, each hospitalist presents an interesting case and leads our group in a discussion of the differential diagnosis, similar to what is done in the NEJM case presentations,” Dr. Angelo says. “At the end of the meeting, the presenter then provides the relevant points from the literature.”

Valerie J. Lang, MD, and her hospitalist colleagues in the division of Hospital Medicine at the University of Rochester (N.Y.) School of Medicine and Dentistry hold their own journal club twice a month. “We include the General Medicine division [their outpatient counterparts], which adds a nice perspective to our inpatient work,” she says.

Like the physicians at the Hospital of St. Raphael, these doctors also rotate topic selection and presentation. “For example, the last time [it was my turn], I presented a meta-analysis of DVT prophylaxis in medical inpatients along with a review of how to interpret meta-analyses,” Dr. Lang says.

The General Internal Medicine division at the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey in New Brunswick, where the four-person hospital medicine group (HMG) resides, takes a slightly different approach. The group has a weekly journal club, reviewing a month’s worth of four major journals, one per week, says Gabriela S. Ferreira, MD.

The Waterbury Hospital HMG, Waterbury, Conn., has its journal club once a month—at a restaurant. “One hospitalist presents an article, and then we eat and get drunk and have a generally good time,” says Rachel Lovins, MD, director of the hospitalist program.

When pressed about whether cocktail availability interferes with information retention, Dr. Lovins admits that’s the reason the presentations are made early in the evening. But she also backs down a bit: “We don’t actually get drunk but the social stuff is so important. It’s glue.”

Although the group totals 20 hospitalists, only a core group of six to 10 usually attends the dinners. Dr. Lovins makes sure everyone gets the pertinent information. “When I present an article, I always write up a summary page and hand it out at the meeting and also e-mail to the rest of the group,” she says. “But I’m a dork and no one else really does that.”

It’s All Timing

Sometimes it’s not about the method of receiving information, but about when and where you receive it. For example, when David Pressel, MD, PhD, director of Inpatient Service, General Pediatrics at Nemours Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children in Wilmington, Del., encounters a patient with a new and different condition, he researches it immediately. “When learning is attached to a patient you see,” he says, “you’re more likely to cement that information in your mind.”

Dr. Wright uses a similar methodology. “I try to look up a couple of articles on every patient every day, with periodic reviews,” she says.

Other physicians, like Benny Gavi, MD, a hospitalist at Stanford Hospital & Clinics in California, print out articles of interest. “I take one or two articles in the pocket of my white coat to read when I have time, for example, when waiting for a meeting to start,” he says. “The pile is also near where I have lunch and I take an article when I eat.”

One hospitalist, who wishes to remain nameless, uses another time to get his literature scoop: at his daily poop, so to speak, during that block of time each day when he sits and reads. “Continuing education is a lifelong process and can happen anytime,” he says, whimsically. TH

Andrea Sattinger is a freelance writer based in North Carolina and a longtime contributor to The Hospitalist.

Reference

- Bennett, HJ. A piece of my mind. Keeping up with the literature. JAMA. 1992;267(7):920.

How does Martin Izakovic, MD, medical director of the hospitalist program at Mercy Hospital in Iowa City, Iowa, suggest keeping current with medical literature?

“Let your journals pile up in your office, including the free ones you never subscribed to, feel guilty about throwing any away, tell yourself you will get to them one day, and then watch as it almost never happens.”

Dr. Izakovic is kidding, of course, but it’s no joke trying to read the wealth of medical information published daily. In fact, some people call it impossible. So to stay afloat, many hospitalists go electronic or turn to journal clubs.

Electronic Resources to the Rescue

It’s not for lack of trying that you can’t get through all the literature out there. Most hospitalists we queried say they only skim through the major internal medicine-related journals, including the Annals of Internal Medicine, the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), The New England Journal of Medicine, Lancet, the Journal of General Internal Medicine, and the Journal of Hospital Medicine.

What really keeps hospitalists apprised of the latest medical news and research, they say, comes to them by way of the World Wide Web—straight to their inboxes. To start, many register for e-mails of journal tables of contents. Others subscribe to the American College of Physicians Journal Club, which reviews and critiques journal articles, rates the relevance of each article on a five-point scale, offers a customized literature updating service, and bundles mailings with the Annals.

Some physicians, like Leora Horwitz, MD, assistant professor in the division of General Internal Medicine at Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, only wish to receive information pertinent to specific topics. To make this happen, Dr. Horwitz sets up a search through Ovid or PubMed that runs about every two weeks and flags new articles that match her criteria.

“I only do this for absolutely key areas and I make the search criteria very restrictive so I only get one to two hits a month at most,” she says. “Then I set up an alert for one or two major articles in each field I am interested in.”

Dr. Horwitz also sets up alerts for her own published articles.

Hospitalists who work at academic institutions, in particular, are inundated with information via grand rounds, lectures, and formats for topics related to hospital medicine.

“We’ll take a list of top conditions relevant to our practice, to review as a working group and then take that to the rest of the group to decide how we’ll standardize care,” says Julia S. Wright, MD, director of hospital medicine and an associate professor of medicine at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison.

On top of setting up specific searches, many hospitalists use their institutions’ subscriptions to services such as:

- UpToDate, the evidence-based, peer-reviewed electronic resource for doctors;

- InfoPOEMs, Patient-Oriented Evidence that Matters from Essential Evidence Plus;

- Epocrates and Micromedex, for drug-related information;

- JournalWATCH;

- The Medical Letter;

- The Hospitalist’s “In the Literature” department; and

- PubMed.

Physicians each have their favorite subscription services. Bill Stinnette, MD, a hospitalist for the Permanente Medical Group, Inc. at Kaiser Permanente San Rafael Medical Center in northern California, recommends MedPage Today daily headlines online as “an excellent source for breaking news and studies, with subspecialty areas, interactive features, FDA alerts, and CME.”

Kenneth Patrick, MD, hospitalist and ICU director of Chestnut Hill Hospital in Philadelphia, uses Medscape as his main online update method. After having completed a personalized profile of his interests, Dr. Patrick now receives e-mail links and general articles based on his criteria. “There’s no paper, it’s done at a convenient time and location, you don’t have to remember where you put that journal you were reading when you were interrupted, and there’s online CME credits,” he says.

Gatherings Become Informative Discussions

Despite enthusiasm about getting information electronically, many hospitalists continue to benefit from—and enjoy—good old-fashioned journal clubs. For example, the quarterly “Lunch and Learn” at the Hospital of St. Raphael in New Haven, Conn., developed by hospitalist Ilona Figura, MD, “has been a real hit,” says Steven Angelo, MD, director of hospitalist services there.

“On a rotating basis, each hospitalist presents an interesting case and leads our group in a discussion of the differential diagnosis, similar to what is done in the NEJM case presentations,” Dr. Angelo says. “At the end of the meeting, the presenter then provides the relevant points from the literature.”

Valerie J. Lang, MD, and her hospitalist colleagues in the division of Hospital Medicine at the University of Rochester (N.Y.) School of Medicine and Dentistry hold their own journal club twice a month. “We include the General Medicine division [their outpatient counterparts], which adds a nice perspective to our inpatient work,” she says.

Like the physicians at the Hospital of St. Raphael, these doctors also rotate topic selection and presentation. “For example, the last time [it was my turn], I presented a meta-analysis of DVT prophylaxis in medical inpatients along with a review of how to interpret meta-analyses,” Dr. Lang says.

The General Internal Medicine division at the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey in New Brunswick, where the four-person hospital medicine group (HMG) resides, takes a slightly different approach. The group has a weekly journal club, reviewing a month’s worth of four major journals, one per week, says Gabriela S. Ferreira, MD.

The Waterbury Hospital HMG, Waterbury, Conn., has its journal club once a month—at a restaurant. “One hospitalist presents an article, and then we eat and get drunk and have a generally good time,” says Rachel Lovins, MD, director of the hospitalist program.

When pressed about whether cocktail availability interferes with information retention, Dr. Lovins admits that’s the reason the presentations are made early in the evening. But she also backs down a bit: “We don’t actually get drunk but the social stuff is so important. It’s glue.”

Although the group totals 20 hospitalists, only a core group of six to 10 usually attends the dinners. Dr. Lovins makes sure everyone gets the pertinent information. “When I present an article, I always write up a summary page and hand it out at the meeting and also e-mail to the rest of the group,” she says. “But I’m a dork and no one else really does that.”

It’s All Timing

Sometimes it’s not about the method of receiving information, but about when and where you receive it. For example, when David Pressel, MD, PhD, director of Inpatient Service, General Pediatrics at Nemours Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children in Wilmington, Del., encounters a patient with a new and different condition, he researches it immediately. “When learning is attached to a patient you see,” he says, “you’re more likely to cement that information in your mind.”

Dr. Wright uses a similar methodology. “I try to look up a couple of articles on every patient every day, with periodic reviews,” she says.

Other physicians, like Benny Gavi, MD, a hospitalist at Stanford Hospital & Clinics in California, print out articles of interest. “I take one or two articles in the pocket of my white coat to read when I have time, for example, when waiting for a meeting to start,” he says. “The pile is also near where I have lunch and I take an article when I eat.”

One hospitalist, who wishes to remain nameless, uses another time to get his literature scoop: at his daily poop, so to speak, during that block of time each day when he sits and reads. “Continuing education is a lifelong process and can happen anytime,” he says, whimsically. TH

Andrea Sattinger is a freelance writer based in North Carolina and a longtime contributor to The Hospitalist.

Reference

- Bennett, HJ. A piece of my mind. Keeping up with the literature. JAMA. 1992;267(7):920.

How does Martin Izakovic, MD, medical director of the hospitalist program at Mercy Hospital in Iowa City, Iowa, suggest keeping current with medical literature?

“Let your journals pile up in your office, including the free ones you never subscribed to, feel guilty about throwing any away, tell yourself you will get to them one day, and then watch as it almost never happens.”

Dr. Izakovic is kidding, of course, but it’s no joke trying to read the wealth of medical information published daily. In fact, some people call it impossible. So to stay afloat, many hospitalists go electronic or turn to journal clubs.

Electronic Resources to the Rescue

It’s not for lack of trying that you can’t get through all the literature out there. Most hospitalists we queried say they only skim through the major internal medicine-related journals, including the Annals of Internal Medicine, the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), The New England Journal of Medicine, Lancet, the Journal of General Internal Medicine, and the Journal of Hospital Medicine.

What really keeps hospitalists apprised of the latest medical news and research, they say, comes to them by way of the World Wide Web—straight to their inboxes. To start, many register for e-mails of journal tables of contents. Others subscribe to the American College of Physicians Journal Club, which reviews and critiques journal articles, rates the relevance of each article on a five-point scale, offers a customized literature updating service, and bundles mailings with the Annals.

Some physicians, like Leora Horwitz, MD, assistant professor in the division of General Internal Medicine at Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, only wish to receive information pertinent to specific topics. To make this happen, Dr. Horwitz sets up a search through Ovid or PubMed that runs about every two weeks and flags new articles that match her criteria.

“I only do this for absolutely key areas and I make the search criteria very restrictive so I only get one to two hits a month at most,” she says. “Then I set up an alert for one or two major articles in each field I am interested in.”

Dr. Horwitz also sets up alerts for her own published articles.

Hospitalists who work at academic institutions, in particular, are inundated with information via grand rounds, lectures, and formats for topics related to hospital medicine.

“We’ll take a list of top conditions relevant to our practice, to review as a working group and then take that to the rest of the group to decide how we’ll standardize care,” says Julia S. Wright, MD, director of hospital medicine and an associate professor of medicine at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison.

On top of setting up specific searches, many hospitalists use their institutions’ subscriptions to services such as:

- UpToDate, the evidence-based, peer-reviewed electronic resource for doctors;

- InfoPOEMs, Patient-Oriented Evidence that Matters from Essential Evidence Plus;

- Epocrates and Micromedex, for drug-related information;

- JournalWATCH;

- The Medical Letter;

- The Hospitalist’s “In the Literature” department; and

- PubMed.

Physicians each have their favorite subscription services. Bill Stinnette, MD, a hospitalist for the Permanente Medical Group, Inc. at Kaiser Permanente San Rafael Medical Center in northern California, recommends MedPage Today daily headlines online as “an excellent source for breaking news and studies, with subspecialty areas, interactive features, FDA alerts, and CME.”

Kenneth Patrick, MD, hospitalist and ICU director of Chestnut Hill Hospital in Philadelphia, uses Medscape as his main online update method. After having completed a personalized profile of his interests, Dr. Patrick now receives e-mail links and general articles based on his criteria. “There’s no paper, it’s done at a convenient time and location, you don’t have to remember where you put that journal you were reading when you were interrupted, and there’s online CME credits,” he says.

Gatherings Become Informative Discussions

Despite enthusiasm about getting information electronically, many hospitalists continue to benefit from—and enjoy—good old-fashioned journal clubs. For example, the quarterly “Lunch and Learn” at the Hospital of St. Raphael in New Haven, Conn., developed by hospitalist Ilona Figura, MD, “has been a real hit,” says Steven Angelo, MD, director of hospitalist services there.

“On a rotating basis, each hospitalist presents an interesting case and leads our group in a discussion of the differential diagnosis, similar to what is done in the NEJM case presentations,” Dr. Angelo says. “At the end of the meeting, the presenter then provides the relevant points from the literature.”

Valerie J. Lang, MD, and her hospitalist colleagues in the division of Hospital Medicine at the University of Rochester (N.Y.) School of Medicine and Dentistry hold their own journal club twice a month. “We include the General Medicine division [their outpatient counterparts], which adds a nice perspective to our inpatient work,” she says.

Like the physicians at the Hospital of St. Raphael, these doctors also rotate topic selection and presentation. “For example, the last time [it was my turn], I presented a meta-analysis of DVT prophylaxis in medical inpatients along with a review of how to interpret meta-analyses,” Dr. Lang says.

The General Internal Medicine division at the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey in New Brunswick, where the four-person hospital medicine group (HMG) resides, takes a slightly different approach. The group has a weekly journal club, reviewing a month’s worth of four major journals, one per week, says Gabriela S. Ferreira, MD.

The Waterbury Hospital HMG, Waterbury, Conn., has its journal club once a month—at a restaurant. “One hospitalist presents an article, and then we eat and get drunk and have a generally good time,” says Rachel Lovins, MD, director of the hospitalist program.

When pressed about whether cocktail availability interferes with information retention, Dr. Lovins admits that’s the reason the presentations are made early in the evening. But she also backs down a bit: “We don’t actually get drunk but the social stuff is so important. It’s glue.”

Although the group totals 20 hospitalists, only a core group of six to 10 usually attends the dinners. Dr. Lovins makes sure everyone gets the pertinent information. “When I present an article, I always write up a summary page and hand it out at the meeting and also e-mail to the rest of the group,” she says. “But I’m a dork and no one else really does that.”

It’s All Timing

Sometimes it’s not about the method of receiving information, but about when and where you receive it. For example, when David Pressel, MD, PhD, director of Inpatient Service, General Pediatrics at Nemours Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children in Wilmington, Del., encounters a patient with a new and different condition, he researches it immediately. “When learning is attached to a patient you see,” he says, “you’re more likely to cement that information in your mind.”

Dr. Wright uses a similar methodology. “I try to look up a couple of articles on every patient every day, with periodic reviews,” she says.

Other physicians, like Benny Gavi, MD, a hospitalist at Stanford Hospital & Clinics in California, print out articles of interest. “I take one or two articles in the pocket of my white coat to read when I have time, for example, when waiting for a meeting to start,” he says. “The pile is also near where I have lunch and I take an article when I eat.”

One hospitalist, who wishes to remain nameless, uses another time to get his literature scoop: at his daily poop, so to speak, during that block of time each day when he sits and reads. “Continuing education is a lifelong process and can happen anytime,” he says, whimsically. TH

Andrea Sattinger is a freelance writer based in North Carolina and a longtime contributor to The Hospitalist.

Reference

- Bennett, HJ. A piece of my mind. Keeping up with the literature. JAMA. 1992;267(7):920.

Hitting the Big Time

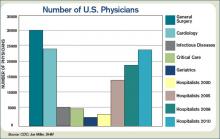

No matter how big a hospital medicine group is, the leader is likely to say “but we need a couple more.” As the fastest-growing medical specialty in the history of American medicine, there never seem to be enough hospitalists (see Figure 1, p. 28).

“The programs are getting larger and larger, ranging anywhere from 20 to 100 physicians in a hospitalist group,” says Jeffrey Hay, MD, senior vice president of medical operations for Lakeside Systems Inc. in Los Angeles.

Because of this rapid growth, two questions become apparent:

1. How is a big hospitalist group defined?

2. What does it take to manage a big group well?

How Big is Big?

Although what constitutes a big hospitalist group is relative, Leslie Flores and her partner, John Nelson, MD, of Nelson/Flores Associates, LLC, La Quinta, Calif., estimate with about 20-30 hospitalists, the role of the medical director becomes a different job than for the typical-sized practice of 10-15 hospitalists.

According to SHM Executive Advisor to the CEO Joseph Miller, this year’s “Society of Hospital Medicine 2007-08 Survey: The Authoritative Source on the State of the Hospitalist Movement” revealed only eight groups with more than 40 hospitalists (excluding the multistate hospitalist management companies). In the approximate 2,200 hospitalist groups in the U.S., Miller estimates there are perhaps 40 groups with 40 or more physicians compared with two in the previous 2005-06 survey.

Medical directors of hospital medicine groups (HMGs) ranging from 22-100 people offer varied insights about how the role of medical director changes as groups grow from big to bigger to biggest.

Big

Jeffery Kin, MD, medical director of the private-practice group Fredericks Hospitalist Group PC, manages 22 hospitalists, and about 130-140 inpatients and 45 admissions a day at Mary Washington Hospital in Fredericksburg, Va. They began as a team of three in 2000 as the outgrowth of a hospital house-doctor program.

“The medical director’s role changes and evolves with the growth of the group,” says Dr. Kin. He and other medical directors of larger groups find it more difficult to retain the informal shift arrival or departure and lunches together that were possible when the HMG was smaller. “Now that we are bigger it is more ‘protocolized,’” Dr. Kin says, “but we try to maintain a family-like atmosphere because I think it makes physicians want to stay with the group long term and not move on with every little problem or challenge that inevitably arises in the changing filed of hospital medicine.”

William Ford, MD, program medical director for Cogent Healthcare and the chief of hospital medicine at Temple University in Philadelphia, considers his group of 28 hospitalists to be a “small” big group. Dr. Ford’s group, which covers three of the four hospitals in the university health systems, grew from five hospitalists in September 2006. He devotes about half his time on personnel issues, including recruitment, retention, and staff development.

As groups grow, so does diversity, requiring more flexibility to manage leaves of absence, scheduling, and day-to-day practice. “In a large group we tend to bring on new measures,” Dr. Ford says. “We change like the wind, so if you aren’t ready for that, you will have a lot of turnover.”

Bigger

Jasen W. Gundersen, MD, MBA, division chief, hospital medicine, University of Massachusetts Memorial Medical Center, Worcester, grew his HMG from 3.6 FTEs three years ago to the 47.5 FTEs (40 physician FTEs and 7.5 FTEs nurse practitioners) they now employ. The group, which covers four hospitals ranging from a 30-bed community hospital to a 770-bed academic hospital, is the biggest HMG in New England. “Our budget numbers for charges and volume are 2.19 times what we projected in the budget,” he says.

With an average of 185 billable patient encounters per day, Dr. Gundersen attributes his successes to a management style based on a financial business model and a revision of the compensation plan. By increasing effectiveness, they reward their doctors with more free time and subsequently improved physician retention.

As the group, the budget, and the financial impact all expand, formal training becomes more important for leaders. While few HMG leaders have a background in the strategic processes of running a company, Dr. Gundersen earned his MBA and believes his training made it easier to talk to administrators, meet clients, track data, effect change, and better handle the politics inherent to the job. “The role is a lot more political than people are aware of because you are such a big presence to the hospital,” he says. “Everybody wants something from you.”

Part of that phenomenon, coined “medical creep” by one hospitalist, can best be defined as the gradual increase in workload shifted to HMGs without a proportional shift in resources to do the work. Work previously done by either surgical specialists or medical subspecialists must be shifted as they more narrowly define their workload; what is left over (more general medical care, phone calls, after-hours work, and paperwork) goes to “co-managing” hospitalists.

Asked about this phenomenon, Tom Lorence, MD, chief of hospitalist medicine for the Northwest Kaiser Permanente region, Portland, Ore., says: “The larger the hospitalist groups become, the bigger a target we are for this shifting. Most try to justify it by saying, ‘It is only a little more work.’ ”

Dr. Lorence and two colleagues began his HMG in 1990; he now manages 55 hospitalists at three facilities. “Administrators have to be convinced that it is worth the money to reshift their priorities and give more resources to the hospital medicine groups,” he says.

Mark V. Williams, MD, FACP, professor and chief, division of hospital medicine, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, moved to his current post last September. Northwestern Memorial Hospital almost doubled its hospitalists to 42 in one year. The initial challenges at Northwestern primarily include assimilating new faculty and establishing a culture of thriving on change, says Dr. Williams, who is also editor in chief of the Journal of Hospital Medicine.

Biggest

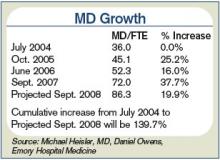

The distinction between academic and non-academic programs is an important one says Michael B. Heisler, MD, MPH, who became the interim medical director of Emory Healthcare, Atlanta, in March 2007 when Dr. Williams moved to Northwestern. Generally, the Emory group has increased in size by 20% each of the past five years. Beginning with nine hospitalists in 1999, it now exceeds 80 (see Figure 2, p. 28).

Academic hospitals have additional stakeholders and deliverables expected by those to whom the medical director reports. Whereas community hospital medicine programs are driven by patient encounters/RVUs, quality improvement, and the bottom line, academic groups also must engage in scholarly activities.

Dr. Heisler and his group have just completed a three-year strategic plan that emphasizes medical education and research and a plateau to the group’s growth.

“We can’t be the premier academic program with growth going through the roof,” Dr. Heisler says. “With some limits we are not going to increase services within our institutions and will not entertain requests to grow into any other facilities through 2010. You can’t develop faculty, define protected time, and invest in scholarly work when you are constantly in growth mode.”

Strategic planning has a different tone for Tyler Jung, MD, director of inpatient services of the multi-specialty group HealthCare Partners, who took over that position three years ago when Dr. Hay left. About 100 hospitalists are employed under the HealthCare Partners umbrella; approximately 85 are on the payroll, and 15 work in a strategic alliance. The HMG covers 14 community hospitals in Southern California, about 14 hospitals in Las Vegas, Nevada, and about five hospitals in the Tampa/Orlando area of Florida.

The full-risk California medical model drives a lot of the metrics. “We look at [relative value unit] goals for our hospitalists, but mostly to ensure proper staffing,” Dr. Jung says. “We are satisfied when our docs have 12 to 14 encounters a day. In the service market you’d go broke with that, but I’d rather have our hospitalists see our patients twice a day because it drives quality and it turns out to be more cost effective.”

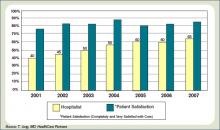

Some of the outcomes Dr. Jung regularly reviews include patient utilization per membership (admit rates, readmit data, and length of stay), and these metrics are largely unchanged as they have grown. “Additionally, maintaining high patient satisfaction can be overlooked, but is critical with the growth of any program,” he says (see Figure 3, p. 28).

Dr. Williams, who began the hospitalist group at Emory Healthcare, says the primary challenges he faced as that program grew were finding capable physicians willing to join a new or expanding program; managing the different cultures at different hospitals and working to ensure they all felt a part of the whole; having sufficient administrative support time to manage recruitment and credentialing; and keeping up constant communications with individuals and leadership at all sites. He found it helpful to occasionally rotate hospitalists, especially the more senior physicians, so they could appreciate the workload and issues at different sites.

Dr. Williams, who trained in internal medicine but later became board certified in emergency medicine, is not surprised Dr. Jung has some background in critical care, as does Dr. Heisler. He surmises they also all have well-honed administrative skills. “The experience I had in running a 65,000-visit-a-year emergency room and a 45,000-visit-a-year urgent-care center gave me the skills to run a large hospital medicine program,” Dr. Williams says. TH

Andrea M. Sattinger is a medical writer based in North Carolina.

No matter how big a hospital medicine group is, the leader is likely to say “but we need a couple more.” As the fastest-growing medical specialty in the history of American medicine, there never seem to be enough hospitalists (see Figure 1, p. 28).

“The programs are getting larger and larger, ranging anywhere from 20 to 100 physicians in a hospitalist group,” says Jeffrey Hay, MD, senior vice president of medical operations for Lakeside Systems Inc. in Los Angeles.

Because of this rapid growth, two questions become apparent:

1. How is a big hospitalist group defined?

2. What does it take to manage a big group well?

How Big is Big?

Although what constitutes a big hospitalist group is relative, Leslie Flores and her partner, John Nelson, MD, of Nelson/Flores Associates, LLC, La Quinta, Calif., estimate with about 20-30 hospitalists, the role of the medical director becomes a different job than for the typical-sized practice of 10-15 hospitalists.

According to SHM Executive Advisor to the CEO Joseph Miller, this year’s “Society of Hospital Medicine 2007-08 Survey: The Authoritative Source on the State of the Hospitalist Movement” revealed only eight groups with more than 40 hospitalists (excluding the multistate hospitalist management companies). In the approximate 2,200 hospitalist groups in the U.S., Miller estimates there are perhaps 40 groups with 40 or more physicians compared with two in the previous 2005-06 survey.

Medical directors of hospital medicine groups (HMGs) ranging from 22-100 people offer varied insights about how the role of medical director changes as groups grow from big to bigger to biggest.

Big

Jeffery Kin, MD, medical director of the private-practice group Fredericks Hospitalist Group PC, manages 22 hospitalists, and about 130-140 inpatients and 45 admissions a day at Mary Washington Hospital in Fredericksburg, Va. They began as a team of three in 2000 as the outgrowth of a hospital house-doctor program.

“The medical director’s role changes and evolves with the growth of the group,” says Dr. Kin. He and other medical directors of larger groups find it more difficult to retain the informal shift arrival or departure and lunches together that were possible when the HMG was smaller. “Now that we are bigger it is more ‘protocolized,’” Dr. Kin says, “but we try to maintain a family-like atmosphere because I think it makes physicians want to stay with the group long term and not move on with every little problem or challenge that inevitably arises in the changing filed of hospital medicine.”

William Ford, MD, program medical director for Cogent Healthcare and the chief of hospital medicine at Temple University in Philadelphia, considers his group of 28 hospitalists to be a “small” big group. Dr. Ford’s group, which covers three of the four hospitals in the university health systems, grew from five hospitalists in September 2006. He devotes about half his time on personnel issues, including recruitment, retention, and staff development.

As groups grow, so does diversity, requiring more flexibility to manage leaves of absence, scheduling, and day-to-day practice. “In a large group we tend to bring on new measures,” Dr. Ford says. “We change like the wind, so if you aren’t ready for that, you will have a lot of turnover.”

Bigger

Jasen W. Gundersen, MD, MBA, division chief, hospital medicine, University of Massachusetts Memorial Medical Center, Worcester, grew his HMG from 3.6 FTEs three years ago to the 47.5 FTEs (40 physician FTEs and 7.5 FTEs nurse practitioners) they now employ. The group, which covers four hospitals ranging from a 30-bed community hospital to a 770-bed academic hospital, is the biggest HMG in New England. “Our budget numbers for charges and volume are 2.19 times what we projected in the budget,” he says.

With an average of 185 billable patient encounters per day, Dr. Gundersen attributes his successes to a management style based on a financial business model and a revision of the compensation plan. By increasing effectiveness, they reward their doctors with more free time and subsequently improved physician retention.

As the group, the budget, and the financial impact all expand, formal training becomes more important for leaders. While few HMG leaders have a background in the strategic processes of running a company, Dr. Gundersen earned his MBA and believes his training made it easier to talk to administrators, meet clients, track data, effect change, and better handle the politics inherent to the job. “The role is a lot more political than people are aware of because you are such a big presence to the hospital,” he says. “Everybody wants something from you.”

Part of that phenomenon, coined “medical creep” by one hospitalist, can best be defined as the gradual increase in workload shifted to HMGs without a proportional shift in resources to do the work. Work previously done by either surgical specialists or medical subspecialists must be shifted as they more narrowly define their workload; what is left over (more general medical care, phone calls, after-hours work, and paperwork) goes to “co-managing” hospitalists.

Asked about this phenomenon, Tom Lorence, MD, chief of hospitalist medicine for the Northwest Kaiser Permanente region, Portland, Ore., says: “The larger the hospitalist groups become, the bigger a target we are for this shifting. Most try to justify it by saying, ‘It is only a little more work.’ ”

Dr. Lorence and two colleagues began his HMG in 1990; he now manages 55 hospitalists at three facilities. “Administrators have to be convinced that it is worth the money to reshift their priorities and give more resources to the hospital medicine groups,” he says.

Mark V. Williams, MD, FACP, professor and chief, division of hospital medicine, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, moved to his current post last September. Northwestern Memorial Hospital almost doubled its hospitalists to 42 in one year. The initial challenges at Northwestern primarily include assimilating new faculty and establishing a culture of thriving on change, says Dr. Williams, who is also editor in chief of the Journal of Hospital Medicine.

Biggest

The distinction between academic and non-academic programs is an important one says Michael B. Heisler, MD, MPH, who became the interim medical director of Emory Healthcare, Atlanta, in March 2007 when Dr. Williams moved to Northwestern. Generally, the Emory group has increased in size by 20% each of the past five years. Beginning with nine hospitalists in 1999, it now exceeds 80 (see Figure 2, p. 28).

Academic hospitals have additional stakeholders and deliverables expected by those to whom the medical director reports. Whereas community hospital medicine programs are driven by patient encounters/RVUs, quality improvement, and the bottom line, academic groups also must engage in scholarly activities.

Dr. Heisler and his group have just completed a three-year strategic plan that emphasizes medical education and research and a plateau to the group’s growth.

“We can’t be the premier academic program with growth going through the roof,” Dr. Heisler says. “With some limits we are not going to increase services within our institutions and will not entertain requests to grow into any other facilities through 2010. You can’t develop faculty, define protected time, and invest in scholarly work when you are constantly in growth mode.”

Strategic planning has a different tone for Tyler Jung, MD, director of inpatient services of the multi-specialty group HealthCare Partners, who took over that position three years ago when Dr. Hay left. About 100 hospitalists are employed under the HealthCare Partners umbrella; approximately 85 are on the payroll, and 15 work in a strategic alliance. The HMG covers 14 community hospitals in Southern California, about 14 hospitals in Las Vegas, Nevada, and about five hospitals in the Tampa/Orlando area of Florida.

The full-risk California medical model drives a lot of the metrics. “We look at [relative value unit] goals for our hospitalists, but mostly to ensure proper staffing,” Dr. Jung says. “We are satisfied when our docs have 12 to 14 encounters a day. In the service market you’d go broke with that, but I’d rather have our hospitalists see our patients twice a day because it drives quality and it turns out to be more cost effective.”

Some of the outcomes Dr. Jung regularly reviews include patient utilization per membership (admit rates, readmit data, and length of stay), and these metrics are largely unchanged as they have grown. “Additionally, maintaining high patient satisfaction can be overlooked, but is critical with the growth of any program,” he says (see Figure 3, p. 28).

Dr. Williams, who began the hospitalist group at Emory Healthcare, says the primary challenges he faced as that program grew were finding capable physicians willing to join a new or expanding program; managing the different cultures at different hospitals and working to ensure they all felt a part of the whole; having sufficient administrative support time to manage recruitment and credentialing; and keeping up constant communications with individuals and leadership at all sites. He found it helpful to occasionally rotate hospitalists, especially the more senior physicians, so they could appreciate the workload and issues at different sites.

Dr. Williams, who trained in internal medicine but later became board certified in emergency medicine, is not surprised Dr. Jung has some background in critical care, as does Dr. Heisler. He surmises they also all have well-honed administrative skills. “The experience I had in running a 65,000-visit-a-year emergency room and a 45,000-visit-a-year urgent-care center gave me the skills to run a large hospital medicine program,” Dr. Williams says. TH

Andrea M. Sattinger is a medical writer based in North Carolina.

No matter how big a hospital medicine group is, the leader is likely to say “but we need a couple more.” As the fastest-growing medical specialty in the history of American medicine, there never seem to be enough hospitalists (see Figure 1, p. 28).

“The programs are getting larger and larger, ranging anywhere from 20 to 100 physicians in a hospitalist group,” says Jeffrey Hay, MD, senior vice president of medical operations for Lakeside Systems Inc. in Los Angeles.

Because of this rapid growth, two questions become apparent:

1. How is a big hospitalist group defined?

2. What does it take to manage a big group well?

How Big is Big?

Although what constitutes a big hospitalist group is relative, Leslie Flores and her partner, John Nelson, MD, of Nelson/Flores Associates, LLC, La Quinta, Calif., estimate with about 20-30 hospitalists, the role of the medical director becomes a different job than for the typical-sized practice of 10-15 hospitalists.

According to SHM Executive Advisor to the CEO Joseph Miller, this year’s “Society of Hospital Medicine 2007-08 Survey: The Authoritative Source on the State of the Hospitalist Movement” revealed only eight groups with more than 40 hospitalists (excluding the multistate hospitalist management companies). In the approximate 2,200 hospitalist groups in the U.S., Miller estimates there are perhaps 40 groups with 40 or more physicians compared with two in the previous 2005-06 survey.

Medical directors of hospital medicine groups (HMGs) ranging from 22-100 people offer varied insights about how the role of medical director changes as groups grow from big to bigger to biggest.

Big

Jeffery Kin, MD, medical director of the private-practice group Fredericks Hospitalist Group PC, manages 22 hospitalists, and about 130-140 inpatients and 45 admissions a day at Mary Washington Hospital in Fredericksburg, Va. They began as a team of three in 2000 as the outgrowth of a hospital house-doctor program.

“The medical director’s role changes and evolves with the growth of the group,” says Dr. Kin. He and other medical directors of larger groups find it more difficult to retain the informal shift arrival or departure and lunches together that were possible when the HMG was smaller. “Now that we are bigger it is more ‘protocolized,’” Dr. Kin says, “but we try to maintain a family-like atmosphere because I think it makes physicians want to stay with the group long term and not move on with every little problem or challenge that inevitably arises in the changing filed of hospital medicine.”

William Ford, MD, program medical director for Cogent Healthcare and the chief of hospital medicine at Temple University in Philadelphia, considers his group of 28 hospitalists to be a “small” big group. Dr. Ford’s group, which covers three of the four hospitals in the university health systems, grew from five hospitalists in September 2006. He devotes about half his time on personnel issues, including recruitment, retention, and staff development.

As groups grow, so does diversity, requiring more flexibility to manage leaves of absence, scheduling, and day-to-day practice. “In a large group we tend to bring on new measures,” Dr. Ford says. “We change like the wind, so if you aren’t ready for that, you will have a lot of turnover.”

Bigger

Jasen W. Gundersen, MD, MBA, division chief, hospital medicine, University of Massachusetts Memorial Medical Center, Worcester, grew his HMG from 3.6 FTEs three years ago to the 47.5 FTEs (40 physician FTEs and 7.5 FTEs nurse practitioners) they now employ. The group, which covers four hospitals ranging from a 30-bed community hospital to a 770-bed academic hospital, is the biggest HMG in New England. “Our budget numbers for charges and volume are 2.19 times what we projected in the budget,” he says.

With an average of 185 billable patient encounters per day, Dr. Gundersen attributes his successes to a management style based on a financial business model and a revision of the compensation plan. By increasing effectiveness, they reward their doctors with more free time and subsequently improved physician retention.

As the group, the budget, and the financial impact all expand, formal training becomes more important for leaders. While few HMG leaders have a background in the strategic processes of running a company, Dr. Gundersen earned his MBA and believes his training made it easier to talk to administrators, meet clients, track data, effect change, and better handle the politics inherent to the job. “The role is a lot more political than people are aware of because you are such a big presence to the hospital,” he says. “Everybody wants something from you.”

Part of that phenomenon, coined “medical creep” by one hospitalist, can best be defined as the gradual increase in workload shifted to HMGs without a proportional shift in resources to do the work. Work previously done by either surgical specialists or medical subspecialists must be shifted as they more narrowly define their workload; what is left over (more general medical care, phone calls, after-hours work, and paperwork) goes to “co-managing” hospitalists.

Asked about this phenomenon, Tom Lorence, MD, chief of hospitalist medicine for the Northwest Kaiser Permanente region, Portland, Ore., says: “The larger the hospitalist groups become, the bigger a target we are for this shifting. Most try to justify it by saying, ‘It is only a little more work.’ ”

Dr. Lorence and two colleagues began his HMG in 1990; he now manages 55 hospitalists at three facilities. “Administrators have to be convinced that it is worth the money to reshift their priorities and give more resources to the hospital medicine groups,” he says.

Mark V. Williams, MD, FACP, professor and chief, division of hospital medicine, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, moved to his current post last September. Northwestern Memorial Hospital almost doubled its hospitalists to 42 in one year. The initial challenges at Northwestern primarily include assimilating new faculty and establishing a culture of thriving on change, says Dr. Williams, who is also editor in chief of the Journal of Hospital Medicine.

Biggest

The distinction between academic and non-academic programs is an important one says Michael B. Heisler, MD, MPH, who became the interim medical director of Emory Healthcare, Atlanta, in March 2007 when Dr. Williams moved to Northwestern. Generally, the Emory group has increased in size by 20% each of the past five years. Beginning with nine hospitalists in 1999, it now exceeds 80 (see Figure 2, p. 28).

Academic hospitals have additional stakeholders and deliverables expected by those to whom the medical director reports. Whereas community hospital medicine programs are driven by patient encounters/RVUs, quality improvement, and the bottom line, academic groups also must engage in scholarly activities.

Dr. Heisler and his group have just completed a three-year strategic plan that emphasizes medical education and research and a plateau to the group’s growth.

“We can’t be the premier academic program with growth going through the roof,” Dr. Heisler says. “With some limits we are not going to increase services within our institutions and will not entertain requests to grow into any other facilities through 2010. You can’t develop faculty, define protected time, and invest in scholarly work when you are constantly in growth mode.”

Strategic planning has a different tone for Tyler Jung, MD, director of inpatient services of the multi-specialty group HealthCare Partners, who took over that position three years ago when Dr. Hay left. About 100 hospitalists are employed under the HealthCare Partners umbrella; approximately 85 are on the payroll, and 15 work in a strategic alliance. The HMG covers 14 community hospitals in Southern California, about 14 hospitals in Las Vegas, Nevada, and about five hospitals in the Tampa/Orlando area of Florida.

The full-risk California medical model drives a lot of the metrics. “We look at [relative value unit] goals for our hospitalists, but mostly to ensure proper staffing,” Dr. Jung says. “We are satisfied when our docs have 12 to 14 encounters a day. In the service market you’d go broke with that, but I’d rather have our hospitalists see our patients twice a day because it drives quality and it turns out to be more cost effective.”

Some of the outcomes Dr. Jung regularly reviews include patient utilization per membership (admit rates, readmit data, and length of stay), and these metrics are largely unchanged as they have grown. “Additionally, maintaining high patient satisfaction can be overlooked, but is critical with the growth of any program,” he says (see Figure 3, p. 28).

Dr. Williams, who began the hospitalist group at Emory Healthcare, says the primary challenges he faced as that program grew were finding capable physicians willing to join a new or expanding program; managing the different cultures at different hospitals and working to ensure they all felt a part of the whole; having sufficient administrative support time to manage recruitment and credentialing; and keeping up constant communications with individuals and leadership at all sites. He found it helpful to occasionally rotate hospitalists, especially the more senior physicians, so they could appreciate the workload and issues at different sites.

Dr. Williams, who trained in internal medicine but later became board certified in emergency medicine, is not surprised Dr. Jung has some background in critical care, as does Dr. Heisler. He surmises they also all have well-honed administrative skills. “The experience I had in running a 65,000-visit-a-year emergency room and a 45,000-visit-a-year urgent-care center gave me the skills to run a large hospital medicine program,” Dr. Williams says. TH

Andrea M. Sattinger is a medical writer based in North Carolina.

How Am I Doing?

How hospitalists assess their performance and hone their skills is critical to patient care. Continuing medical education (CME), relicensure, specialty recertification, and lifelong learning are all linked to hospitalists’ abilities to assess and meet their learning needs.

But the preponderance of evidence suggests physicians have limited ability to accurately assess their performance, according to a physician self-assessment literature review published in September 2006 in JAMA.1

“Self-assessment should be guided by tools designed by experts, based on standards, and aimed at filling gaps in knowledge, skills, and competencies—not simply the internally based self-rating of individual practitioners,” says C. Michael Fordis, MD, senior associate dean for con-

tinuing medical education at the Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, and one of the authors of the study.

“Hospitalists and other physicians are not doing themselves a service to rely on their own internal self-rated judgments of knowledge and performance,” Dr. Fordis says. “There’s too much to know, too much that’s changing, and too much that affects the implementation into practice of the knowledge that you have for any one person to be able to take care of patients and at the same time have some sense of whether there are gaps along that implementation pathway.”

“Guided” self-assessment represents the thinking of many experts who ask questions, consider guidelines, and suggest tools that can help physicians pursue the best ways of identifying those gaps that reflect differences in what they think they are doing and their actual performance.

Regular, consistent self-assessment is imperative for a self-regulating profession such as medicine. How well are hospitalists doing—and what mechanisms or tools do they use?

Group Assessment

Hospital medicine groups are increasingly able to measure their clinical competence against other hospitals’ and hospitalist groups. SHM’s Benchmarks Committee has been working on performance assessment at a program level.

“When the JCAHO [Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations] Core Measures were coming out a few years back, as a whole most docs when reflecting on their practice would say they do a fine job within these measures,” says Burke T. Kealey, MD, chairman of the Benchmarks Committee from 2006-07. “For instance, [they might say] ‘I always send people out on ACE inhibitors and beta-blockers,’ or, ‘We always start people on aspirin when they come into the ER,’ but when you looked at the data, you found that their self-assessment was not as accurate as we hoped it would be.”

A lot of hard work went into discovering why their self-assessment was inaccurate. “We found there were documentation problems that they didn’t really incorporate a lot of the contraindications when giving their answer about self-assessment,” says Dr. Kealey, who leads the hospital medicine program at Regions Hospital and HealthPartners Medical Group in St. Paul, Minn.

If patients had kidney dysfunction or kidney failure, they were not discharged on ACE inhibitors.

“But we as doctors didn’t do a great job of explaining why we weren’t doing that,” Dr. Kealey says. “We were not transparent in our reasoning, but the core measures caused us to become more transparent, to explain what we were thinking and what we were doing in a way that the public could see.”

At SHM’s annual meeting in May, the Benchmarks Committee released the white paper “Measuring Hospitalist Performance: Metrics, Reports, and Dashboards” with the intent of assisting hospitals and hospital medicine programs develop or improve their performance monitoring and reporting.

“Hospitalists in general could do a better job of assessing themselves,” says Arpana Vidyarthi, MD, an assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF). “Self-assessment for those of us in cognitive specialties, like internists, is more complicated than in procedural specialties like surgery, partly because these procedural specialties have very specific outcomes that are linked to the procedure and that level of skill. With the new drivers of quality improvement and patient safety, and the dramatic increase of quality indicators for hospitals overall, this is now trickling down to thinking about how we truly assess the doctors themselves.”

The quality indicators that hospitalist groups are benchmarking may not be linked to the individual, she says. Dr. Vidyarthi, also director of quality for the Inpatient General Medicine Service at UCSF Medical Center, provides an example. “Pneumovax as a quality indicator is part of the Joint Commission core measures,” says Dr. Vidyarthi. “You can go online where it is publicly reported and choose this or other indicators to compare one hospital to another. That is the sort of benchmarking that some hospitalists groups are doing.”

But using that kind of evaluation for individual assessment misses the mark.

“Does the fact that the patient does not get Pneumovax reflect upon me and my abilities as a hospitalist? Not at all,” she says, “because my institution and those institutions who have done well with this specific indicator have taken it out of the hands of the doctors. It’s an automated sort of thing. At our hospital, the pharmacists do it.”

Although the American Board of Internal Medicine asks that the individual physician assess his or her own care as part of recredentialing, it’s more difficult for a hospitalist than for an outpatient internist. Hospitalists don’t have a panel of diabetic patients, for instance, for which the outcomes data can be easily analyzed.

Hospitalists as a group also haven’t had a tradition of self-assessment or peer assessment. Further, hospitalist groups differ as to how they handle assessments of individual physicians.

“In general if you ask our [UCSF] hospitalists, the way that we assess competency is generally through hospital privileging,” Dr. Vidyarthi says. Because the hospital as a whole reviews the competency of all the doctors that work there, the process known as “privileging” has consisted of asking a couple of colleagues to write letters of recommendation. “The division is changing this, but that is just on the cusp.

“We’ve built a new system for our quality committee in which one layer is peer assessment, looking at just the individual cases that bubble up from an incident report or a root-cause analysis or other sources. We’re looking at and identifying both systems issues and individual issues and trying to build a way to feed back those assessments.”

But that’s just half the equation, she says, the flip side being continual self-assessment for what a hospitalist is doing well.

To Dr. Kealey, self-assessment plays a significant role in helping physicians with their career goals and ensuring that their careers are on track and on target.

At HealthPartners, physicians fill out a self-evaluation form on which they list all activities they’ve been involved in over the previous year. Then they are asked what they got out of these activities, what their career goals are, and whether they are meeting them. They’re also asked how the group can help them reach those goals.

“We ask them to pause and reflect on where they’re headed with their career and their life, and put it down in writing so that in that moment they take the time to ask, ‘What is it that I’m ultimately after?’ ” says Dr. Kealey.

Day to day, they are immersed in patient care and focused on doing a good job. “But in the trajectory of where they are headed—the committees, projects, and educational activities they are involved in—are they all aligned and pointing in the same direction and the right direction?” Dr Kealey asks.

The process, which HealthPartners hospitalists have been using for about 10 years, was modified from the American College of Physician Executives course “Managing Physician Performance.”

“It is a tool to help hospitalists pause and reflect on their career and how to move it forward,” Dr. Kealey says.

Marc B. Westle, DO, FACP, president and managing partner of the Asheville Hospitalist Group, PA, in Asheville, N.C., relies on ongoing conversations. This group also uses Crimson’s Physician Management Software to track various group quality and cost indicators, looking at data from as many angles as possible.

“It’s an excellent tool to look at a group, it is a poor tool to look at an individual,” Dr. Westle says. “Although the insurance companies like to say you can apply it to the individual, in reality there is no good way to attribute that data down to the physician level.”

Within the group data, it may be possible to recognize underperformers, but still it is anecdotal, based on experience and interaction.

“Under, ‘How am I doing?’ there is an objective category in the software where there are hard end-points and measures you can look at,” says Dr. Westle

On the subjective side, Dr. Westle collects data on relative value units (RVUs), non-monetary, numeric values Medicare uses to represent the relative amount of physician time, resources, and expertise needed to provide various services to patients. They review total RVUs as well as individual-components that make up total RVUs.

“I’ll track how many simple, moderate, or complex follow-up visits were made, how many simple or moderate histories and physicals or consultations, how many procedures are they doing.” Dr. Westle says. “I’ll track every statistic that way for every individual and give them that feedback so they can see how they’re doing from a performance and a work standard, compared to their peers within the group, and nationally as published by Medicare.”

Dr. Westle uses charts and graphs to drive his points home.

“It just gives them an idea about where they are,’’ he says. “It doesn’t mean they’re doing a bad job. Our patients may be sicker than some other patients. And that is why we do it as a group, too, because their patients should be similar to the group’s patients and the group’s patients may be different than the average Medicare patient.”

They also look at hospitalists’ quality of life, their schedules, and the quantity of work the average physician is doing compared with those around the country. They discuss scheduling, income, disposable income, and the kind of work they’re doing in the hospital. “All this comes into a discussion of where they are in their lives and are they happy with what they’re doing,” Dr. Westle says. TH

Andrea Sattinger is a medical writer based in North Carolina.

Reference

- Davis DA, Mazmanian PE, Fordis M, et al. Accuracy of physician self-assessment compared with observed measures of competence: a systematic review. JAMA. 2006;296(9):1094-1102.

How hospitalists assess their performance and hone their skills is critical to patient care. Continuing medical education (CME), relicensure, specialty recertification, and lifelong learning are all linked to hospitalists’ abilities to assess and meet their learning needs.

But the preponderance of evidence suggests physicians have limited ability to accurately assess their performance, according to a physician self-assessment literature review published in September 2006 in JAMA.1

“Self-assessment should be guided by tools designed by experts, based on standards, and aimed at filling gaps in knowledge, skills, and competencies—not simply the internally based self-rating of individual practitioners,” says C. Michael Fordis, MD, senior associate dean for con-

tinuing medical education at the Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, and one of the authors of the study.

“Hospitalists and other physicians are not doing themselves a service to rely on their own internal self-rated judgments of knowledge and performance,” Dr. Fordis says. “There’s too much to know, too much that’s changing, and too much that affects the implementation into practice of the knowledge that you have for any one person to be able to take care of patients and at the same time have some sense of whether there are gaps along that implementation pathway.”

“Guided” self-assessment represents the thinking of many experts who ask questions, consider guidelines, and suggest tools that can help physicians pursue the best ways of identifying those gaps that reflect differences in what they think they are doing and their actual performance.

Regular, consistent self-assessment is imperative for a self-regulating profession such as medicine. How well are hospitalists doing—and what mechanisms or tools do they use?

Group Assessment

Hospital medicine groups are increasingly able to measure their clinical competence against other hospitals’ and hospitalist groups. SHM’s Benchmarks Committee has been working on performance assessment at a program level.

“When the JCAHO [Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations] Core Measures were coming out a few years back, as a whole most docs when reflecting on their practice would say they do a fine job within these measures,” says Burke T. Kealey, MD, chairman of the Benchmarks Committee from 2006-07. “For instance, [they might say] ‘I always send people out on ACE inhibitors and beta-blockers,’ or, ‘We always start people on aspirin when they come into the ER,’ but when you looked at the data, you found that their self-assessment was not as accurate as we hoped it would be.”

A lot of hard work went into discovering why their self-assessment was inaccurate. “We found there were documentation problems that they didn’t really incorporate a lot of the contraindications when giving their answer about self-assessment,” says Dr. Kealey, who leads the hospital medicine program at Regions Hospital and HealthPartners Medical Group in St. Paul, Minn.

If patients had kidney dysfunction or kidney failure, they were not discharged on ACE inhibitors.

“But we as doctors didn’t do a great job of explaining why we weren’t doing that,” Dr. Kealey says. “We were not transparent in our reasoning, but the core measures caused us to become more transparent, to explain what we were thinking and what we were doing in a way that the public could see.”

At SHM’s annual meeting in May, the Benchmarks Committee released the white paper “Measuring Hospitalist Performance: Metrics, Reports, and Dashboards” with the intent of assisting hospitals and hospital medicine programs develop or improve their performance monitoring and reporting.

“Hospitalists in general could do a better job of assessing themselves,” says Arpana Vidyarthi, MD, an assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF). “Self-assessment for those of us in cognitive specialties, like internists, is more complicated than in procedural specialties like surgery, partly because these procedural specialties have very specific outcomes that are linked to the procedure and that level of skill. With the new drivers of quality improvement and patient safety, and the dramatic increase of quality indicators for hospitals overall, this is now trickling down to thinking about how we truly assess the doctors themselves.”

The quality indicators that hospitalist groups are benchmarking may not be linked to the individual, she says. Dr. Vidyarthi, also director of quality for the Inpatient General Medicine Service at UCSF Medical Center, provides an example. “Pneumovax as a quality indicator is part of the Joint Commission core measures,” says Dr. Vidyarthi. “You can go online where it is publicly reported and choose this or other indicators to compare one hospital to another. That is the sort of benchmarking that some hospitalists groups are doing.”

But using that kind of evaluation for individual assessment misses the mark.

“Does the fact that the patient does not get Pneumovax reflect upon me and my abilities as a hospitalist? Not at all,” she says, “because my institution and those institutions who have done well with this specific indicator have taken it out of the hands of the doctors. It’s an automated sort of thing. At our hospital, the pharmacists do it.”

Although the American Board of Internal Medicine asks that the individual physician assess his or her own care as part of recredentialing, it’s more difficult for a hospitalist than for an outpatient internist. Hospitalists don’t have a panel of diabetic patients, for instance, for which the outcomes data can be easily analyzed.

Hospitalists as a group also haven’t had a tradition of self-assessment or peer assessment. Further, hospitalist groups differ as to how they handle assessments of individual physicians.

“In general if you ask our [UCSF] hospitalists, the way that we assess competency is generally through hospital privileging,” Dr. Vidyarthi says. Because the hospital as a whole reviews the competency of all the doctors that work there, the process known as “privileging” has consisted of asking a couple of colleagues to write letters of recommendation. “The division is changing this, but that is just on the cusp.

“We’ve built a new system for our quality committee in which one layer is peer assessment, looking at just the individual cases that bubble up from an incident report or a root-cause analysis or other sources. We’re looking at and identifying both systems issues and individual issues and trying to build a way to feed back those assessments.”

But that’s just half the equation, she says, the flip side being continual self-assessment for what a hospitalist is doing well.

To Dr. Kealey, self-assessment plays a significant role in helping physicians with their career goals and ensuring that their careers are on track and on target.

At HealthPartners, physicians fill out a self-evaluation form on which they list all activities they’ve been involved in over the previous year. Then they are asked what they got out of these activities, what their career goals are, and whether they are meeting them. They’re also asked how the group can help them reach those goals.

“We ask them to pause and reflect on where they’re headed with their career and their life, and put it down in writing so that in that moment they take the time to ask, ‘What is it that I’m ultimately after?’ ” says Dr. Kealey.

Day to day, they are immersed in patient care and focused on doing a good job. “But in the trajectory of where they are headed—the committees, projects, and educational activities they are involved in—are they all aligned and pointing in the same direction and the right direction?” Dr Kealey asks.

The process, which HealthPartners hospitalists have been using for about 10 years, was modified from the American College of Physician Executives course “Managing Physician Performance.”

“It is a tool to help hospitalists pause and reflect on their career and how to move it forward,” Dr. Kealey says.

Marc B. Westle, DO, FACP, president and managing partner of the Asheville Hospitalist Group, PA, in Asheville, N.C., relies on ongoing conversations. This group also uses Crimson’s Physician Management Software to track various group quality and cost indicators, looking at data from as many angles as possible.

“It’s an excellent tool to look at a group, it is a poor tool to look at an individual,” Dr. Westle says. “Although the insurance companies like to say you can apply it to the individual, in reality there is no good way to attribute that data down to the physician level.”

Within the group data, it may be possible to recognize underperformers, but still it is anecdotal, based on experience and interaction.

“Under, ‘How am I doing?’ there is an objective category in the software where there are hard end-points and measures you can look at,” says Dr. Westle

On the subjective side, Dr. Westle collects data on relative value units (RVUs), non-monetary, numeric values Medicare uses to represent the relative amount of physician time, resources, and expertise needed to provide various services to patients. They review total RVUs as well as individual-components that make up total RVUs.

“I’ll track how many simple, moderate, or complex follow-up visits were made, how many simple or moderate histories and physicals or consultations, how many procedures are they doing.” Dr. Westle says. “I’ll track every statistic that way for every individual and give them that feedback so they can see how they’re doing from a performance and a work standard, compared to their peers within the group, and nationally as published by Medicare.”

Dr. Westle uses charts and graphs to drive his points home.

“It just gives them an idea about where they are,’’ he says. “It doesn’t mean they’re doing a bad job. Our patients may be sicker than some other patients. And that is why we do it as a group, too, because their patients should be similar to the group’s patients and the group’s patients may be different than the average Medicare patient.”

They also look at hospitalists’ quality of life, their schedules, and the quantity of work the average physician is doing compared with those around the country. They discuss scheduling, income, disposable income, and the kind of work they’re doing in the hospital. “All this comes into a discussion of where they are in their lives and are they happy with what they’re doing,” Dr. Westle says. TH

Andrea Sattinger is a medical writer based in North Carolina.

Reference

- Davis DA, Mazmanian PE, Fordis M, et al. Accuracy of physician self-assessment compared with observed measures of competence: a systematic review. JAMA. 2006;296(9):1094-1102.

How hospitalists assess their performance and hone their skills is critical to patient care. Continuing medical education (CME), relicensure, specialty recertification, and lifelong learning are all linked to hospitalists’ abilities to assess and meet their learning needs.

But the preponderance of evidence suggests physicians have limited ability to accurately assess their performance, according to a physician self-assessment literature review published in September 2006 in JAMA.1

“Self-assessment should be guided by tools designed by experts, based on standards, and aimed at filling gaps in knowledge, skills, and competencies—not simply the internally based self-rating of individual practitioners,” says C. Michael Fordis, MD, senior associate dean for con-

tinuing medical education at the Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, and one of the authors of the study.

“Hospitalists and other physicians are not doing themselves a service to rely on their own internal self-rated judgments of knowledge and performance,” Dr. Fordis says. “There’s too much to know, too much that’s changing, and too much that affects the implementation into practice of the knowledge that you have for any one person to be able to take care of patients and at the same time have some sense of whether there are gaps along that implementation pathway.”

“Guided” self-assessment represents the thinking of many experts who ask questions, consider guidelines, and suggest tools that can help physicians pursue the best ways of identifying those gaps that reflect differences in what they think they are doing and their actual performance.

Regular, consistent self-assessment is imperative for a self-regulating profession such as medicine. How well are hospitalists doing—and what mechanisms or tools do they use?

Group Assessment

Hospital medicine groups are increasingly able to measure their clinical competence against other hospitals’ and hospitalist groups. SHM’s Benchmarks Committee has been working on performance assessment at a program level.