User login

Bullied into Botched Care

Bullying, intimidation, verbal abuse—these behaviors negatively affect self-esteem, feelings of competence, and workplace morale. And they can devastate hospital professionals and their patients.

When 2,095 healthcare providers (1,565 nurses, 354 pharmacists, and 176 others) responded to an Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) survey on intimidation in their healthcare setting, remarkable data were collected.1

Perhaps the most alarming statistic in the 2003-2004 study was that 7% of respondents (n=147) reported they had been involved in a medication error allowed to occur partly because the respondents were afraid to question the prescriber’s decision. At a large urban trauma center in the northeastern United States, nurses listed intimidation as one of the barriers to implementing a sharps safety program.2

Nurses’ Perceptions

Research over the past decade has spotlighted intimidation in healthcare.3

“Bullying and harassment still happen in many areas of medicine,” says David M. Pressel, MD, PhD, hospitalist and director, Inpatient Service, Division of General Pediatrics at Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children in Wilmington, Del. “The question is, how do you monitor yourself to make sure you aren’t falling into that hierarchical frame of mind that could intervene in great teaching and learning and great patient care?”

Dr. Pressel and his partner, David I. Rappaport, MD, also a pediatric hospitalist at duPont, have focused on the literature pertaining to nurse-physician relationships. Research shows that intimidation impedes nurse recruitment, retention, and satisfaction. In one study, 90% of nurses reported experiencing at least one episode of verbal abuse.4 A 1997 study examining the effects of intimidation on 35 pediatric nurses over a three-month period found that 25 (71.4%) of them reported being yelled at or loudly admonished. Sixteen (45.7%) had been victims of insults. Thirty (85.7%) were spoken to in a condescending manner. One-third of nurses believed that such behavior was “part of the job.”

Although studies have differed as to the most common source of this abuse—patients and families or physicians—a study of pediatric nurses reported a similar incidence from both sources.5 And, nurses are often guilty of verbally abusing each other.6

When the duPont pediatric hospitalist team began performing more family-centered rounds, they began to appreciate the nurse-physician relationship. “We have worked hard to have a charge nurse and oftentimes the bedside nurse with us when we round,” Dr. Rappaport says. Speculating that rounding with hospitalists allowed nurses to feel more part of the team, Dr. Rappaport says know the medical plan, consolidate efforts such that pages to residents were reduced, and generally improve communication. They heard from participating nurses that it made a tremendous difference. This prompted them to conduct their research.

“Our study looked at the nurse-physician relationship globally, not intimidation or abuse specifically,” says Dr. Rappaport. Along with their nurse colleague Norine Watson, RN, Drs. Pressel and Rappaport are examining the relationship between nurses and different categories of physicians: how nurses perceive interactions between nurses and surgical residents, surgical attendings, community physicians, pediatric residents, and pediatric hospitalists.

“Early data suggest that hospitalists may work more effectively with nurses because they share many of the same goals,” says Dr. Rappaport. “As hospital leaders, hospitalists can also improve working conditions for nurses by providing more accessible, efficient, and effective care. Presumably, improved collaboration will also include decreased intimidation or abuse from physicians and also probably from dissatisfied patients and families.”

Avoiding the trap of communicating in a manner that is too direct and might be construed as abusive requires self-awareness and the realization that people receive information in different ways, says Dr. Pressel. Standard professional behavior is the key. Beyond that, the challenge is giving feedback constructively and in a positive manner.

“Hospitalists [may be] more in tune with the needs of nurses than nonhospitalists,” says Dr. Rappaport. “I think that is one of our strengths. We need to continue to facilitate very strong relationships between nurses and physicians because without good nursing care, hospitalists simply cannot provide good medical care.”

There is another way hospitalists can help address verbal abuse. “Studies consistently show that nurses are hesitant to report episodes of verbal abuse,” Dr. Rappaport says, “whether it is from a family, a patient, a physician, or a fellow nurse. Fewer than one in five nurses reports these episodes. One thing that hospitalists can do is work with hospital administration to create an environment that is more proactive in addressing these concerns and allowing nurses to feel more support in this area.”

Only 60% of respondents to the ISMP survey felt their organization had clearly defined an effective process for handling disagreements with a medication order’s safety. Only about a third felt the process facilitated their bypassing an intimidating prescriber or their own supervisor if necessary. Although 70% of respondents reported that they thought their organization or manager would support them if they reported intimidating behavior, only 39% of respondents believed their organization was dealing effectively with intimidating behavior.

Untapped Source

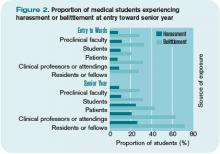

Perceptions of intimidation also occur among trainees. When 2,884 students from the class of 2003 at 16 U.S. medical schools completed questionnaires at various times during training, 27% reported having been “harassed” by house staff, 21% by faculty, and 25% by patients.7 Further, 71% reported having been “belittled” by house staff, 63% by faculty, and 43% by patients.

Mistreated students were significantly more likely to have suffered stress, be depressed or suicidal, and less likely to report being glad they trained as a physician.

—David I. Rappaport, MD, pediatric hospitalist, Alfred I. Dupont Hospital for Children, Wilmington, Del.

This may have an underlying effect on the potential to monitor for patient safety.8,9 Because errors and near misses often result from miscommunication, medical students may be adept at preventing certain types of errors. Students’ observation skills may be just as keen, if not more so, than their more clinically proficient healthcare teammates.8 In four cases from two U.S. academic health centers reported by medical students Samuel Seiden, Cynthia Galvan, and Ruth Lamm in 2006, medical students demonstrated keen attention to detail and appropriately characterized problematic situations with patients—adding another layer of defense within systems safeguarding against patient harm.8 Yet of the 76% of medical students who had observed a medical error, only about half of the students reported the errors to a resident or an attending, despite having received patient-safety training; only 7% reported having used an electronic medical error reporting system.10

By Example

Some intimidation in medical education may be the result of anger toward students and residents over a lack of medical knowledge, says Jeffery G. Wiese, MD, associate professor of Medicine at Tulane University in New Orleans and member of the SHM Board of Directors. “It is natural to feel [that anger]; people abhor in others what they most detest in themselves,’’ he says. “As physicians, a lack of medical knowledge is what we detest in ourselves. But a student’s ignorance is usually a product of where she is in her training; that’s why she is with you.”

—Jeffery G. Wiese, MD, associate professor of Medicine at Tulane University, New Orleans

Anger alienates students, absolving them of the guilt of not knowing the information, and demotivating them from learning it. “The lesson to be communicated is that it is OK not to know, but it is not OK to continue to not know,” Dr. Wiese says. “Reprimands should be reserved for the student who does not know, and then after being taught or asked to look it up, continues to not know.”

“The average physician who practices for 30 years will take care of roughly 80,000 people,” estimates Dr. Wiese. “That’s an arithmetic contribution and there is nothing wrong with that. But if you really want to change the world, teaching is the rule. The same 30 years invested in teaching will indirectly affect 400 million people,” he says. “Even better, if you can train your students and residents in the value of coaching their students and residents, well, now you’re talking about 10 billion people that you can affect over the course of a career.”

The question to ask yourself, says Dr. Wiese, is: Do you want to change the world? “If you do, this is the way to do it,” he says.

“For the 30 years in your career, focus on clinical coaching and getting others to clinically coach. That way, especially if you have the right motives in your heart, the right vision for the way you want to see the profession practiced, and the way you want patient care performed, that’s your shot at changing the world.” TH

Andrea Sattinger is a frequent contributor to The Hospitalist.

References

- Institute for Safe Medication Practice. Intimidation: practitioners speak up about this unresolved problem (Part I). Available at w.ismp.org/Newsletters/acutecare/articles/20040311_2.asp. Last accessed June 27, 2007.

- Hagstrom AM. Perceived barriers to implementation of a successful sharps safety program. AORN J. 2006;83(2):391-7.

- Porto G, Lauve R. Disruptive clinician behavior: a persistent threat to patient safety. Patient Safety Qual Healthc. 2006 Jul-Aug;3:16-24.

- Manderino MA, Berkey N. Verbal abuse of staff nurses by physicians. J Prof Nurs. 1997;13(1):48-55.

- Pejic AR. Verbal abuse: A problem for pediatric nurses. Pediatr Nurs. 2005;31(4):271-279.

- Rowe MM, Sherlock H. Stress and verbal abuse in nursing: do burned out nurses eat their young? J Nurs Manag. 2005May;13(3):242-248.

- Frank E, Carrera JS, Stratton T, et al. Experiences of belittlement and harassment and their correlates among medical students in the United States: longitudinal survey. BMJ. 2006 Sep 30;333(7570):682.

- Seiden SC, Galvan C, Lamm R. Role of medical students in preventing patient harm and enhancing patient safety. Qual Saf Health Care. 2006 Aug;15(4):272-276.

- Wood DF. Bullying and harassment in medical schools. BMJ. 2006 Sep 30;333(7570):664-665.

- Madigosky WS, Headrick LA, Nelson K, et al. Changing and sustaining medical students’ knowledge, skills, and attitudes about patient safety and medical fallibility. Acad Med. 2006 Jan;81(1):94-101.

- Institute for Safe Medication Practice. Intimidation: Mapping a plan for cultural change in healthcare (Part II). Available at www.ismp.org/Newsletters/acutecare/articles/20040325.asp Last accessed July 2, 2007.

Bullying, intimidation, verbal abuse—these behaviors negatively affect self-esteem, feelings of competence, and workplace morale. And they can devastate hospital professionals and their patients.

When 2,095 healthcare providers (1,565 nurses, 354 pharmacists, and 176 others) responded to an Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) survey on intimidation in their healthcare setting, remarkable data were collected.1

Perhaps the most alarming statistic in the 2003-2004 study was that 7% of respondents (n=147) reported they had been involved in a medication error allowed to occur partly because the respondents were afraid to question the prescriber’s decision. At a large urban trauma center in the northeastern United States, nurses listed intimidation as one of the barriers to implementing a sharps safety program.2

Nurses’ Perceptions

Research over the past decade has spotlighted intimidation in healthcare.3

“Bullying and harassment still happen in many areas of medicine,” says David M. Pressel, MD, PhD, hospitalist and director, Inpatient Service, Division of General Pediatrics at Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children in Wilmington, Del. “The question is, how do you monitor yourself to make sure you aren’t falling into that hierarchical frame of mind that could intervene in great teaching and learning and great patient care?”

Dr. Pressel and his partner, David I. Rappaport, MD, also a pediatric hospitalist at duPont, have focused on the literature pertaining to nurse-physician relationships. Research shows that intimidation impedes nurse recruitment, retention, and satisfaction. In one study, 90% of nurses reported experiencing at least one episode of verbal abuse.4 A 1997 study examining the effects of intimidation on 35 pediatric nurses over a three-month period found that 25 (71.4%) of them reported being yelled at or loudly admonished. Sixteen (45.7%) had been victims of insults. Thirty (85.7%) were spoken to in a condescending manner. One-third of nurses believed that such behavior was “part of the job.”

Although studies have differed as to the most common source of this abuse—patients and families or physicians—a study of pediatric nurses reported a similar incidence from both sources.5 And, nurses are often guilty of verbally abusing each other.6

When the duPont pediatric hospitalist team began performing more family-centered rounds, they began to appreciate the nurse-physician relationship. “We have worked hard to have a charge nurse and oftentimes the bedside nurse with us when we round,” Dr. Rappaport says. Speculating that rounding with hospitalists allowed nurses to feel more part of the team, Dr. Rappaport says know the medical plan, consolidate efforts such that pages to residents were reduced, and generally improve communication. They heard from participating nurses that it made a tremendous difference. This prompted them to conduct their research.

“Our study looked at the nurse-physician relationship globally, not intimidation or abuse specifically,” says Dr. Rappaport. Along with their nurse colleague Norine Watson, RN, Drs. Pressel and Rappaport are examining the relationship between nurses and different categories of physicians: how nurses perceive interactions between nurses and surgical residents, surgical attendings, community physicians, pediatric residents, and pediatric hospitalists.

“Early data suggest that hospitalists may work more effectively with nurses because they share many of the same goals,” says Dr. Rappaport. “As hospital leaders, hospitalists can also improve working conditions for nurses by providing more accessible, efficient, and effective care. Presumably, improved collaboration will also include decreased intimidation or abuse from physicians and also probably from dissatisfied patients and families.”

Avoiding the trap of communicating in a manner that is too direct and might be construed as abusive requires self-awareness and the realization that people receive information in different ways, says Dr. Pressel. Standard professional behavior is the key. Beyond that, the challenge is giving feedback constructively and in a positive manner.

“Hospitalists [may be] more in tune with the needs of nurses than nonhospitalists,” says Dr. Rappaport. “I think that is one of our strengths. We need to continue to facilitate very strong relationships between nurses and physicians because without good nursing care, hospitalists simply cannot provide good medical care.”

There is another way hospitalists can help address verbal abuse. “Studies consistently show that nurses are hesitant to report episodes of verbal abuse,” Dr. Rappaport says, “whether it is from a family, a patient, a physician, or a fellow nurse. Fewer than one in five nurses reports these episodes. One thing that hospitalists can do is work with hospital administration to create an environment that is more proactive in addressing these concerns and allowing nurses to feel more support in this area.”

Only 60% of respondents to the ISMP survey felt their organization had clearly defined an effective process for handling disagreements with a medication order’s safety. Only about a third felt the process facilitated their bypassing an intimidating prescriber or their own supervisor if necessary. Although 70% of respondents reported that they thought their organization or manager would support them if they reported intimidating behavior, only 39% of respondents believed their organization was dealing effectively with intimidating behavior.

Untapped Source

Perceptions of intimidation also occur among trainees. When 2,884 students from the class of 2003 at 16 U.S. medical schools completed questionnaires at various times during training, 27% reported having been “harassed” by house staff, 21% by faculty, and 25% by patients.7 Further, 71% reported having been “belittled” by house staff, 63% by faculty, and 43% by patients.

Mistreated students were significantly more likely to have suffered stress, be depressed or suicidal, and less likely to report being glad they trained as a physician.

—David I. Rappaport, MD, pediatric hospitalist, Alfred I. Dupont Hospital for Children, Wilmington, Del.

This may have an underlying effect on the potential to monitor for patient safety.8,9 Because errors and near misses often result from miscommunication, medical students may be adept at preventing certain types of errors. Students’ observation skills may be just as keen, if not more so, than their more clinically proficient healthcare teammates.8 In four cases from two U.S. academic health centers reported by medical students Samuel Seiden, Cynthia Galvan, and Ruth Lamm in 2006, medical students demonstrated keen attention to detail and appropriately characterized problematic situations with patients—adding another layer of defense within systems safeguarding against patient harm.8 Yet of the 76% of medical students who had observed a medical error, only about half of the students reported the errors to a resident or an attending, despite having received patient-safety training; only 7% reported having used an electronic medical error reporting system.10

By Example

Some intimidation in medical education may be the result of anger toward students and residents over a lack of medical knowledge, says Jeffery G. Wiese, MD, associate professor of Medicine at Tulane University in New Orleans and member of the SHM Board of Directors. “It is natural to feel [that anger]; people abhor in others what they most detest in themselves,’’ he says. “As physicians, a lack of medical knowledge is what we detest in ourselves. But a student’s ignorance is usually a product of where she is in her training; that’s why she is with you.”

—Jeffery G. Wiese, MD, associate professor of Medicine at Tulane University, New Orleans

Anger alienates students, absolving them of the guilt of not knowing the information, and demotivating them from learning it. “The lesson to be communicated is that it is OK not to know, but it is not OK to continue to not know,” Dr. Wiese says. “Reprimands should be reserved for the student who does not know, and then after being taught or asked to look it up, continues to not know.”

“The average physician who practices for 30 years will take care of roughly 80,000 people,” estimates Dr. Wiese. “That’s an arithmetic contribution and there is nothing wrong with that. But if you really want to change the world, teaching is the rule. The same 30 years invested in teaching will indirectly affect 400 million people,” he says. “Even better, if you can train your students and residents in the value of coaching their students and residents, well, now you’re talking about 10 billion people that you can affect over the course of a career.”

The question to ask yourself, says Dr. Wiese, is: Do you want to change the world? “If you do, this is the way to do it,” he says.

“For the 30 years in your career, focus on clinical coaching and getting others to clinically coach. That way, especially if you have the right motives in your heart, the right vision for the way you want to see the profession practiced, and the way you want patient care performed, that’s your shot at changing the world.” TH

Andrea Sattinger is a frequent contributor to The Hospitalist.

References

- Institute for Safe Medication Practice. Intimidation: practitioners speak up about this unresolved problem (Part I). Available at w.ismp.org/Newsletters/acutecare/articles/20040311_2.asp. Last accessed June 27, 2007.

- Hagstrom AM. Perceived barriers to implementation of a successful sharps safety program. AORN J. 2006;83(2):391-7.

- Porto G, Lauve R. Disruptive clinician behavior: a persistent threat to patient safety. Patient Safety Qual Healthc. 2006 Jul-Aug;3:16-24.

- Manderino MA, Berkey N. Verbal abuse of staff nurses by physicians. J Prof Nurs. 1997;13(1):48-55.

- Pejic AR. Verbal abuse: A problem for pediatric nurses. Pediatr Nurs. 2005;31(4):271-279.

- Rowe MM, Sherlock H. Stress and verbal abuse in nursing: do burned out nurses eat their young? J Nurs Manag. 2005May;13(3):242-248.

- Frank E, Carrera JS, Stratton T, et al. Experiences of belittlement and harassment and their correlates among medical students in the United States: longitudinal survey. BMJ. 2006 Sep 30;333(7570):682.

- Seiden SC, Galvan C, Lamm R. Role of medical students in preventing patient harm and enhancing patient safety. Qual Saf Health Care. 2006 Aug;15(4):272-276.

- Wood DF. Bullying and harassment in medical schools. BMJ. 2006 Sep 30;333(7570):664-665.

- Madigosky WS, Headrick LA, Nelson K, et al. Changing and sustaining medical students’ knowledge, skills, and attitudes about patient safety and medical fallibility. Acad Med. 2006 Jan;81(1):94-101.

- Institute for Safe Medication Practice. Intimidation: Mapping a plan for cultural change in healthcare (Part II). Available at www.ismp.org/Newsletters/acutecare/articles/20040325.asp Last accessed July 2, 2007.

Bullying, intimidation, verbal abuse—these behaviors negatively affect self-esteem, feelings of competence, and workplace morale. And they can devastate hospital professionals and their patients.

When 2,095 healthcare providers (1,565 nurses, 354 pharmacists, and 176 others) responded to an Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) survey on intimidation in their healthcare setting, remarkable data were collected.1

Perhaps the most alarming statistic in the 2003-2004 study was that 7% of respondents (n=147) reported they had been involved in a medication error allowed to occur partly because the respondents were afraid to question the prescriber’s decision. At a large urban trauma center in the northeastern United States, nurses listed intimidation as one of the barriers to implementing a sharps safety program.2

Nurses’ Perceptions

Research over the past decade has spotlighted intimidation in healthcare.3

“Bullying and harassment still happen in many areas of medicine,” says David M. Pressel, MD, PhD, hospitalist and director, Inpatient Service, Division of General Pediatrics at Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children in Wilmington, Del. “The question is, how do you monitor yourself to make sure you aren’t falling into that hierarchical frame of mind that could intervene in great teaching and learning and great patient care?”

Dr. Pressel and his partner, David I. Rappaport, MD, also a pediatric hospitalist at duPont, have focused on the literature pertaining to nurse-physician relationships. Research shows that intimidation impedes nurse recruitment, retention, and satisfaction. In one study, 90% of nurses reported experiencing at least one episode of verbal abuse.4 A 1997 study examining the effects of intimidation on 35 pediatric nurses over a three-month period found that 25 (71.4%) of them reported being yelled at or loudly admonished. Sixteen (45.7%) had been victims of insults. Thirty (85.7%) were spoken to in a condescending manner. One-third of nurses believed that such behavior was “part of the job.”

Although studies have differed as to the most common source of this abuse—patients and families or physicians—a study of pediatric nurses reported a similar incidence from both sources.5 And, nurses are often guilty of verbally abusing each other.6

When the duPont pediatric hospitalist team began performing more family-centered rounds, they began to appreciate the nurse-physician relationship. “We have worked hard to have a charge nurse and oftentimes the bedside nurse with us when we round,” Dr. Rappaport says. Speculating that rounding with hospitalists allowed nurses to feel more part of the team, Dr. Rappaport says know the medical plan, consolidate efforts such that pages to residents were reduced, and generally improve communication. They heard from participating nurses that it made a tremendous difference. This prompted them to conduct their research.

“Our study looked at the nurse-physician relationship globally, not intimidation or abuse specifically,” says Dr. Rappaport. Along with their nurse colleague Norine Watson, RN, Drs. Pressel and Rappaport are examining the relationship between nurses and different categories of physicians: how nurses perceive interactions between nurses and surgical residents, surgical attendings, community physicians, pediatric residents, and pediatric hospitalists.

“Early data suggest that hospitalists may work more effectively with nurses because they share many of the same goals,” says Dr. Rappaport. “As hospital leaders, hospitalists can also improve working conditions for nurses by providing more accessible, efficient, and effective care. Presumably, improved collaboration will also include decreased intimidation or abuse from physicians and also probably from dissatisfied patients and families.”

Avoiding the trap of communicating in a manner that is too direct and might be construed as abusive requires self-awareness and the realization that people receive information in different ways, says Dr. Pressel. Standard professional behavior is the key. Beyond that, the challenge is giving feedback constructively and in a positive manner.

“Hospitalists [may be] more in tune with the needs of nurses than nonhospitalists,” says Dr. Rappaport. “I think that is one of our strengths. We need to continue to facilitate very strong relationships between nurses and physicians because without good nursing care, hospitalists simply cannot provide good medical care.”

There is another way hospitalists can help address verbal abuse. “Studies consistently show that nurses are hesitant to report episodes of verbal abuse,” Dr. Rappaport says, “whether it is from a family, a patient, a physician, or a fellow nurse. Fewer than one in five nurses reports these episodes. One thing that hospitalists can do is work with hospital administration to create an environment that is more proactive in addressing these concerns and allowing nurses to feel more support in this area.”

Only 60% of respondents to the ISMP survey felt their organization had clearly defined an effective process for handling disagreements with a medication order’s safety. Only about a third felt the process facilitated their bypassing an intimidating prescriber or their own supervisor if necessary. Although 70% of respondents reported that they thought their organization or manager would support them if they reported intimidating behavior, only 39% of respondents believed their organization was dealing effectively with intimidating behavior.

Untapped Source

Perceptions of intimidation also occur among trainees. When 2,884 students from the class of 2003 at 16 U.S. medical schools completed questionnaires at various times during training, 27% reported having been “harassed” by house staff, 21% by faculty, and 25% by patients.7 Further, 71% reported having been “belittled” by house staff, 63% by faculty, and 43% by patients.

Mistreated students were significantly more likely to have suffered stress, be depressed or suicidal, and less likely to report being glad they trained as a physician.

—David I. Rappaport, MD, pediatric hospitalist, Alfred I. Dupont Hospital for Children, Wilmington, Del.

This may have an underlying effect on the potential to monitor for patient safety.8,9 Because errors and near misses often result from miscommunication, medical students may be adept at preventing certain types of errors. Students’ observation skills may be just as keen, if not more so, than their more clinically proficient healthcare teammates.8 In four cases from two U.S. academic health centers reported by medical students Samuel Seiden, Cynthia Galvan, and Ruth Lamm in 2006, medical students demonstrated keen attention to detail and appropriately characterized problematic situations with patients—adding another layer of defense within systems safeguarding against patient harm.8 Yet of the 76% of medical students who had observed a medical error, only about half of the students reported the errors to a resident or an attending, despite having received patient-safety training; only 7% reported having used an electronic medical error reporting system.10

By Example

Some intimidation in medical education may be the result of anger toward students and residents over a lack of medical knowledge, says Jeffery G. Wiese, MD, associate professor of Medicine at Tulane University in New Orleans and member of the SHM Board of Directors. “It is natural to feel [that anger]; people abhor in others what they most detest in themselves,’’ he says. “As physicians, a lack of medical knowledge is what we detest in ourselves. But a student’s ignorance is usually a product of where she is in her training; that’s why she is with you.”

—Jeffery G. Wiese, MD, associate professor of Medicine at Tulane University, New Orleans

Anger alienates students, absolving them of the guilt of not knowing the information, and demotivating them from learning it. “The lesson to be communicated is that it is OK not to know, but it is not OK to continue to not know,” Dr. Wiese says. “Reprimands should be reserved for the student who does not know, and then after being taught or asked to look it up, continues to not know.”

“The average physician who practices for 30 years will take care of roughly 80,000 people,” estimates Dr. Wiese. “That’s an arithmetic contribution and there is nothing wrong with that. But if you really want to change the world, teaching is the rule. The same 30 years invested in teaching will indirectly affect 400 million people,” he says. “Even better, if you can train your students and residents in the value of coaching their students and residents, well, now you’re talking about 10 billion people that you can affect over the course of a career.”

The question to ask yourself, says Dr. Wiese, is: Do you want to change the world? “If you do, this is the way to do it,” he says.

“For the 30 years in your career, focus on clinical coaching and getting others to clinically coach. That way, especially if you have the right motives in your heart, the right vision for the way you want to see the profession practiced, and the way you want patient care performed, that’s your shot at changing the world.” TH

Andrea Sattinger is a frequent contributor to The Hospitalist.

References

- Institute for Safe Medication Practice. Intimidation: practitioners speak up about this unresolved problem (Part I). Available at w.ismp.org/Newsletters/acutecare/articles/20040311_2.asp. Last accessed June 27, 2007.

- Hagstrom AM. Perceived barriers to implementation of a successful sharps safety program. AORN J. 2006;83(2):391-7.

- Porto G, Lauve R. Disruptive clinician behavior: a persistent threat to patient safety. Patient Safety Qual Healthc. 2006 Jul-Aug;3:16-24.

- Manderino MA, Berkey N. Verbal abuse of staff nurses by physicians. J Prof Nurs. 1997;13(1):48-55.

- Pejic AR. Verbal abuse: A problem for pediatric nurses. Pediatr Nurs. 2005;31(4):271-279.

- Rowe MM, Sherlock H. Stress and verbal abuse in nursing: do burned out nurses eat their young? J Nurs Manag. 2005May;13(3):242-248.

- Frank E, Carrera JS, Stratton T, et al. Experiences of belittlement and harassment and their correlates among medical students in the United States: longitudinal survey. BMJ. 2006 Sep 30;333(7570):682.

- Seiden SC, Galvan C, Lamm R. Role of medical students in preventing patient harm and enhancing patient safety. Qual Saf Health Care. 2006 Aug;15(4):272-276.

- Wood DF. Bullying and harassment in medical schools. BMJ. 2006 Sep 30;333(7570):664-665.

- Madigosky WS, Headrick LA, Nelson K, et al. Changing and sustaining medical students’ knowledge, skills, and attitudes about patient safety and medical fallibility. Acad Med. 2006 Jan;81(1):94-101.

- Institute for Safe Medication Practice. Intimidation: Mapping a plan for cultural change in healthcare (Part II). Available at www.ismp.org/Newsletters/acutecare/articles/20040325.asp Last accessed July 2, 2007.

The Gray Zone

In part 1 of this two-part series (July 2007, p. 16), hospitalists and emergency medicine physicians expressed their views on the relationship between their two specialties. In part 2, we look at how those relationships intersect—and what issues are at stake when they do.

One area where there is a bit of overlap between hospital medicine and emergency medicine is observational medicine,” says James W. Hoekstra, MD, professor and chairman, Department of Emergency Medicine, Wake Forest University Health Sciences Center, Winston-Salem, N.C.

Those patients who require a short stay for observation, he says, are neither in the ED or admitted to the hospital—they are in a zone of their own.

“That’s a gray zone in terms of who takes care of those patients,” he says, “and it depends on the hospital. It will be interesting to see how that works out, or whether that is ever worked out. It may just stay a shared area.”

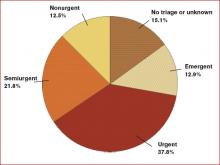

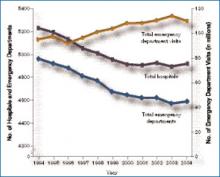

The observation conundrum is complicated by the fact that many people use emergency departments for primary care. (See Figure 1, p. 33) “ True emergencies make up only some of the patient [cases] in the ED,” says Debra L. Burgy, MD, a hospitalist at Abbott Northwestern Hospital in Minneapolis. “We do have a 23-hour observation unit of 10 beds, and, frankly, could use 10 more to [handle unpredictable volumes of patients and insufficient support staff. That unit] has certainly helped to alleviate unnecessary admissions.”

Collaboration between hospitalists and emergency medicine physicians happens a number of ways at the University of Colorado at Denver and Health Sciences Center, where Jeff Glasheen, MD, is director of both the hospital medicine program and inpatient clinical services in the department of medicine.

“One way we work closely with the ED—because we think it is the right thing to do—is by building a much more comprehensive observation unit,” Dr. Glasheen says. “In some settings the observation unit lives in the ED and is run by the ED and in others, it is run by hospitalists. The hospitalists [here] will now run the unit, but we want to help solve some of the ED’s throughput issues.”

When Dr. Glasheen arrived at his institution, the observation unit was limited to patients with chest pain. “I didn’t understand why we would get chest pain patients through efficiently and not all patients,” he says.

A team that began operating in July will be available for all patients under the admission status of observation. The team will be hospitalist-led and aim to reduce length of stay and increase quality of care for those patients.

“Right now those patients are very scattered throughout the system and they may be [covered by] six to eight different teams,” Dr. Glasheen explains. One team of caregivers will be more efficient and reduce length of stay, he says.

By nurturing their working relationship with the emergency department, hospitalists will be able to more easily say: “We understand that that workup’s not complete, but we also understand that they’re going to come into the hospital and let us know what things need to be done. We’ll be happy to take that patient a little earlier than we did in the past to get them out of the ED.”

That’s a tricky thing to do, he says, “because the benefit to us isn’t huge, we’re self-sacrificing to help the ED, and that’s what I want hospitalist groups nationally to be thinking: how we can make the whole system better and not just make our own job better.”

Dr. Glasheen believes the professional structure in his institution is representative of what other hospitals will function like in the next 10 years.

“You have a backbone structure of basically four types of physicians: emergency medicine docs, hospitalists, intensivists, and a surgical team,” Dr. Glasheen says. “Everyone else, more and more, is serving in a consultative role.” Having that backbone allows you to tackle the issues, which are primarily complex, systems-based issues, he says. “It is no longer [a matter of just] the ED trying to deal with capacity issues. Now they have an ally on the inpatient side.”

An excess of patients for the number of beds means some patients spend a disproportionate amount of their stay in the ED, and that challenges communication and efficiency. “The challenges may be simple things, such as it being harder for a hospitalist to get to the ED to see a patient than it is upstairs,” Dr. Glasheen says. “[Or] it’s harder to decide who really has ownership of that patient.” In his hospital, as soon as a patient is assigned to a hospitalist, the primary responsibility for that patient is seen as the hospitalist’s.

But there are other issues. “Even if we are able to get down [to the ED] and write orders, that is problematic for the ED and the hospitalist; as a hospitalist we don’t have the nurses with staffing ratios and skills in the ED that they have on floors and in the ICU,” says Dr. Glasheen. “It is not always possible to get things done as efficiently as they probably could if the patients were in a proper unit. Locally and globally in my experience, the biggest issue is: How do you take care of these patients who now spend their inpatient stay in the ED?”

Collaborations, Models, and Solutions

A number of hospitalists raise the issue of managing internal medicine residents doing rotations in the ED.

“We were approached recently by the ED because most of our admissions are called in directly to the medical residents,” says Jason R. Orlinick, MD, PhD, head of the section of Hospital Medicine at Norwalk Hospital, Conn. “I think the ED would like to talk directly with the medical attending assuming care for the patient. One of the things we haven’t done well is meet on a regular basis to discuss communication issues.”

The hospitalists and emergency medicine group at Dr. Orlinick’s institution have entertained the idea of setting up a direct triage system whereby medical residents are taken out of the picture. “The emergency medicine docs would page us directly—at least during the busiest hours of the day. Eventually, the hope is to make it a 24-hour, seven-days-a-week, 365 [days-a-year process],” says Dr. Orlinick. By bringing this to the emergency medicine physicians, the intent was to send the message that hospitalists recognize ED overcrowding as an institutional issue and want to improve communication with their ED colleagues to improve patient care.

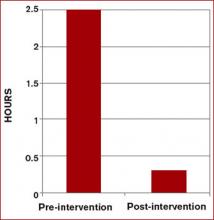

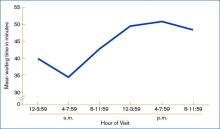

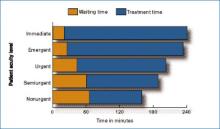

This model, devised at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center in Baltimore, enabled communication between ED doctors and hospitalists, and reduced wait times by more than two hours when a bed was available.2 This triage and direct-admission protocol was not associated with increased mortality and resulted in improved patient and physician satisfaction. (See Figure 2 at right). Once the ED attending decides to admit a patient, direct communication is facilitated with a hospitalist. The approach includes monthly meetings between the department of medicine and the ED to continue to discuss improvements in admissions.

At Norwalk Hospital, the administration asked the hospitalist group to intervene in that throughput process. But Dr. Orlinick, also a clinical instructor of medicine at Yale University in New Haven, Conn., says they’ve hesitated out of sensitivity to their ED colleagues.

“We as a group have really struggled with that concept because [although] we feel like that is something we can do well, this is really within the purview of the emergency medicine docs,” says Dr. Orlinick. Adopting the Johns Hopkins model is a win-win solution where each specialty is providing its best skills to solve mutual issues. “What we can do well is look at the patients … on the floor[s], look at flow through the hospital systems in terms of getting testing; make sure that all that—and consults—happen in a timely manner, and that people leave the hospital when they’ve reached their goals of hospitalization,” he says. “It’s afterload as opposed to preload.”

Hospitalists see committee collaboration as important to solving the complex multidisciplinary systemic issues. Jasen W. Gundersen, MD, participates on a pneumonia task force with several hospitalists, a pulmonologist, and one of the heads of the ED. “We address the whole gamut from when patients come in to when they go through the hospital,” says Dr. Gundersen, head of the Hospital Medicine Division, University of Massachusetts Memorial Medical Center, Worcester. “We can learn from each other as we go through the process.”

Many of the ways hospitalists and ED physicians tackle systems-related issues are new to Dr. Glasheen’s institution because the hospital medicine program was begun in 2004. It is now common to see higher-level leadership from different specialties and areas all in the same room—talking about issues of capacity, for instance. There are also many more instances of hospitalists and ED physicians sitting on the same committees. Further, “It is relatively common for our ED to call our hospitalists to say, ‘Can you help see this patient? I’m not sure what to do,’ or, ‘I’ve got this situation with this patient, this needs to be done and I need help getting that done,’ ” Dr. Glasheen says. Even though he concedes that is more of a workaround as opposed to a solution for a faulty system, it still represents ED physicians and hospitalists co-managing that workaround.

The Future

Because he “sits on both sides of the fence” between emergency medicine and hospital medicine, Dr. Gundersen thinks it is especially important for hospitalists to train in all the different areas—including emergency medicine—when they are medical students and residents.

Emergency medicine physicians Dr. Hoekstra and Benjamin Honigman, MD, professor of surgery and head of the Division of Emergency Medicine at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, Denver, believe hospital medicine will be integral to that training. Dr. Glasheen, also the director of the longest-running internal medicine hospitalist-training program in the U.S., expects greater attention to hospitalist training. “My sense is that many hospitalists groups are in a growth phase and are trying to solve their own problems,” he says. Basically, their primary focus is staffing the hospital with good people and retaining them. He believes that once groups have been around for three to five years, they are more likely to take on bigger issues, such as hospital efficiency and capacity management.

“One of the reasons we started a hospitalist training program is that I didn’t want hospitalists to fall into the same mistakes, barriers, or issues that we’ve had in the past,” Dr. Glasheen says. He fears “this sort of continued balkanization of hospital care, where everyone silos everything out and considers such issues as throughput and ED divert as outside of their [jurisdiction]. I want to get to the place where hospitalists are looking at the whole hospital system and are justly rewarded for that either by financial incentives or time to [work on systemic issues].”

Dr. Glasheen and his team remind themselves of where their commitment resides: “This hospital is where we live—and with everything between the front door to the back door, our primary job is to make this a better place.” TH

Andrea Sattinger is a frequent contributor to The Hospitalist.

References

- Burt CW, McCaig LF. Staffing, capacity, and ambulance diversion in emergency departments: United States, 2003-04. Adv Data; US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, Hyattsville, Md. Sept. 27, 2006. Available at: www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ad/ad376.pdf. Last accessed June 25, 2007.

- Howell EE, Bessman ES, Rubin HR. Hospitalists and an innovative emergency department admission process. J Gen Intern Med. 2004 Mar;19(3):266-268.

In part 1 of this two-part series (July 2007, p. 16), hospitalists and emergency medicine physicians expressed their views on the relationship between their two specialties. In part 2, we look at how those relationships intersect—and what issues are at stake when they do.

One area where there is a bit of overlap between hospital medicine and emergency medicine is observational medicine,” says James W. Hoekstra, MD, professor and chairman, Department of Emergency Medicine, Wake Forest University Health Sciences Center, Winston-Salem, N.C.

Those patients who require a short stay for observation, he says, are neither in the ED or admitted to the hospital—they are in a zone of their own.

“That’s a gray zone in terms of who takes care of those patients,” he says, “and it depends on the hospital. It will be interesting to see how that works out, or whether that is ever worked out. It may just stay a shared area.”

The observation conundrum is complicated by the fact that many people use emergency departments for primary care. (See Figure 1, p. 33) “ True emergencies make up only some of the patient [cases] in the ED,” says Debra L. Burgy, MD, a hospitalist at Abbott Northwestern Hospital in Minneapolis. “We do have a 23-hour observation unit of 10 beds, and, frankly, could use 10 more to [handle unpredictable volumes of patients and insufficient support staff. That unit] has certainly helped to alleviate unnecessary admissions.”

Collaboration between hospitalists and emergency medicine physicians happens a number of ways at the University of Colorado at Denver and Health Sciences Center, where Jeff Glasheen, MD, is director of both the hospital medicine program and inpatient clinical services in the department of medicine.

“One way we work closely with the ED—because we think it is the right thing to do—is by building a much more comprehensive observation unit,” Dr. Glasheen says. “In some settings the observation unit lives in the ED and is run by the ED and in others, it is run by hospitalists. The hospitalists [here] will now run the unit, but we want to help solve some of the ED’s throughput issues.”

When Dr. Glasheen arrived at his institution, the observation unit was limited to patients with chest pain. “I didn’t understand why we would get chest pain patients through efficiently and not all patients,” he says.

A team that began operating in July will be available for all patients under the admission status of observation. The team will be hospitalist-led and aim to reduce length of stay and increase quality of care for those patients.

“Right now those patients are very scattered throughout the system and they may be [covered by] six to eight different teams,” Dr. Glasheen explains. One team of caregivers will be more efficient and reduce length of stay, he says.

By nurturing their working relationship with the emergency department, hospitalists will be able to more easily say: “We understand that that workup’s not complete, but we also understand that they’re going to come into the hospital and let us know what things need to be done. We’ll be happy to take that patient a little earlier than we did in the past to get them out of the ED.”

That’s a tricky thing to do, he says, “because the benefit to us isn’t huge, we’re self-sacrificing to help the ED, and that’s what I want hospitalist groups nationally to be thinking: how we can make the whole system better and not just make our own job better.”

Dr. Glasheen believes the professional structure in his institution is representative of what other hospitals will function like in the next 10 years.

“You have a backbone structure of basically four types of physicians: emergency medicine docs, hospitalists, intensivists, and a surgical team,” Dr. Glasheen says. “Everyone else, more and more, is serving in a consultative role.” Having that backbone allows you to tackle the issues, which are primarily complex, systems-based issues, he says. “It is no longer [a matter of just] the ED trying to deal with capacity issues. Now they have an ally on the inpatient side.”

An excess of patients for the number of beds means some patients spend a disproportionate amount of their stay in the ED, and that challenges communication and efficiency. “The challenges may be simple things, such as it being harder for a hospitalist to get to the ED to see a patient than it is upstairs,” Dr. Glasheen says. “[Or] it’s harder to decide who really has ownership of that patient.” In his hospital, as soon as a patient is assigned to a hospitalist, the primary responsibility for that patient is seen as the hospitalist’s.

But there are other issues. “Even if we are able to get down [to the ED] and write orders, that is problematic for the ED and the hospitalist; as a hospitalist we don’t have the nurses with staffing ratios and skills in the ED that they have on floors and in the ICU,” says Dr. Glasheen. “It is not always possible to get things done as efficiently as they probably could if the patients were in a proper unit. Locally and globally in my experience, the biggest issue is: How do you take care of these patients who now spend their inpatient stay in the ED?”

Collaborations, Models, and Solutions

A number of hospitalists raise the issue of managing internal medicine residents doing rotations in the ED.

“We were approached recently by the ED because most of our admissions are called in directly to the medical residents,” says Jason R. Orlinick, MD, PhD, head of the section of Hospital Medicine at Norwalk Hospital, Conn. “I think the ED would like to talk directly with the medical attending assuming care for the patient. One of the things we haven’t done well is meet on a regular basis to discuss communication issues.”

The hospitalists and emergency medicine group at Dr. Orlinick’s institution have entertained the idea of setting up a direct triage system whereby medical residents are taken out of the picture. “The emergency medicine docs would page us directly—at least during the busiest hours of the day. Eventually, the hope is to make it a 24-hour, seven-days-a-week, 365 [days-a-year process],” says Dr. Orlinick. By bringing this to the emergency medicine physicians, the intent was to send the message that hospitalists recognize ED overcrowding as an institutional issue and want to improve communication with their ED colleagues to improve patient care.

This model, devised at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center in Baltimore, enabled communication between ED doctors and hospitalists, and reduced wait times by more than two hours when a bed was available.2 This triage and direct-admission protocol was not associated with increased mortality and resulted in improved patient and physician satisfaction. (See Figure 2 at right). Once the ED attending decides to admit a patient, direct communication is facilitated with a hospitalist. The approach includes monthly meetings between the department of medicine and the ED to continue to discuss improvements in admissions.

At Norwalk Hospital, the administration asked the hospitalist group to intervene in that throughput process. But Dr. Orlinick, also a clinical instructor of medicine at Yale University in New Haven, Conn., says they’ve hesitated out of sensitivity to their ED colleagues.

“We as a group have really struggled with that concept because [although] we feel like that is something we can do well, this is really within the purview of the emergency medicine docs,” says Dr. Orlinick. Adopting the Johns Hopkins model is a win-win solution where each specialty is providing its best skills to solve mutual issues. “What we can do well is look at the patients … on the floor[s], look at flow through the hospital systems in terms of getting testing; make sure that all that—and consults—happen in a timely manner, and that people leave the hospital when they’ve reached their goals of hospitalization,” he says. “It’s afterload as opposed to preload.”

Hospitalists see committee collaboration as important to solving the complex multidisciplinary systemic issues. Jasen W. Gundersen, MD, participates on a pneumonia task force with several hospitalists, a pulmonologist, and one of the heads of the ED. “We address the whole gamut from when patients come in to when they go through the hospital,” says Dr. Gundersen, head of the Hospital Medicine Division, University of Massachusetts Memorial Medical Center, Worcester. “We can learn from each other as we go through the process.”

Many of the ways hospitalists and ED physicians tackle systems-related issues are new to Dr. Glasheen’s institution because the hospital medicine program was begun in 2004. It is now common to see higher-level leadership from different specialties and areas all in the same room—talking about issues of capacity, for instance. There are also many more instances of hospitalists and ED physicians sitting on the same committees. Further, “It is relatively common for our ED to call our hospitalists to say, ‘Can you help see this patient? I’m not sure what to do,’ or, ‘I’ve got this situation with this patient, this needs to be done and I need help getting that done,’ ” Dr. Glasheen says. Even though he concedes that is more of a workaround as opposed to a solution for a faulty system, it still represents ED physicians and hospitalists co-managing that workaround.

The Future

Because he “sits on both sides of the fence” between emergency medicine and hospital medicine, Dr. Gundersen thinks it is especially important for hospitalists to train in all the different areas—including emergency medicine—when they are medical students and residents.

Emergency medicine physicians Dr. Hoekstra and Benjamin Honigman, MD, professor of surgery and head of the Division of Emergency Medicine at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, Denver, believe hospital medicine will be integral to that training. Dr. Glasheen, also the director of the longest-running internal medicine hospitalist-training program in the U.S., expects greater attention to hospitalist training. “My sense is that many hospitalists groups are in a growth phase and are trying to solve their own problems,” he says. Basically, their primary focus is staffing the hospital with good people and retaining them. He believes that once groups have been around for three to five years, they are more likely to take on bigger issues, such as hospital efficiency and capacity management.

“One of the reasons we started a hospitalist training program is that I didn’t want hospitalists to fall into the same mistakes, barriers, or issues that we’ve had in the past,” Dr. Glasheen says. He fears “this sort of continued balkanization of hospital care, where everyone silos everything out and considers such issues as throughput and ED divert as outside of their [jurisdiction]. I want to get to the place where hospitalists are looking at the whole hospital system and are justly rewarded for that either by financial incentives or time to [work on systemic issues].”

Dr. Glasheen and his team remind themselves of where their commitment resides: “This hospital is where we live—and with everything between the front door to the back door, our primary job is to make this a better place.” TH

Andrea Sattinger is a frequent contributor to The Hospitalist.

References

- Burt CW, McCaig LF. Staffing, capacity, and ambulance diversion in emergency departments: United States, 2003-04. Adv Data; US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, Hyattsville, Md. Sept. 27, 2006. Available at: www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ad/ad376.pdf. Last accessed June 25, 2007.

- Howell EE, Bessman ES, Rubin HR. Hospitalists and an innovative emergency department admission process. J Gen Intern Med. 2004 Mar;19(3):266-268.

In part 1 of this two-part series (July 2007, p. 16), hospitalists and emergency medicine physicians expressed their views on the relationship between their two specialties. In part 2, we look at how those relationships intersect—and what issues are at stake when they do.

One area where there is a bit of overlap between hospital medicine and emergency medicine is observational medicine,” says James W. Hoekstra, MD, professor and chairman, Department of Emergency Medicine, Wake Forest University Health Sciences Center, Winston-Salem, N.C.

Those patients who require a short stay for observation, he says, are neither in the ED or admitted to the hospital—they are in a zone of their own.

“That’s a gray zone in terms of who takes care of those patients,” he says, “and it depends on the hospital. It will be interesting to see how that works out, or whether that is ever worked out. It may just stay a shared area.”

The observation conundrum is complicated by the fact that many people use emergency departments for primary care. (See Figure 1, p. 33) “ True emergencies make up only some of the patient [cases] in the ED,” says Debra L. Burgy, MD, a hospitalist at Abbott Northwestern Hospital in Minneapolis. “We do have a 23-hour observation unit of 10 beds, and, frankly, could use 10 more to [handle unpredictable volumes of patients and insufficient support staff. That unit] has certainly helped to alleviate unnecessary admissions.”

Collaboration between hospitalists and emergency medicine physicians happens a number of ways at the University of Colorado at Denver and Health Sciences Center, where Jeff Glasheen, MD, is director of both the hospital medicine program and inpatient clinical services in the department of medicine.

“One way we work closely with the ED—because we think it is the right thing to do—is by building a much more comprehensive observation unit,” Dr. Glasheen says. “In some settings the observation unit lives in the ED and is run by the ED and in others, it is run by hospitalists. The hospitalists [here] will now run the unit, but we want to help solve some of the ED’s throughput issues.”

When Dr. Glasheen arrived at his institution, the observation unit was limited to patients with chest pain. “I didn’t understand why we would get chest pain patients through efficiently and not all patients,” he says.

A team that began operating in July will be available for all patients under the admission status of observation. The team will be hospitalist-led and aim to reduce length of stay and increase quality of care for those patients.

“Right now those patients are very scattered throughout the system and they may be [covered by] six to eight different teams,” Dr. Glasheen explains. One team of caregivers will be more efficient and reduce length of stay, he says.

By nurturing their working relationship with the emergency department, hospitalists will be able to more easily say: “We understand that that workup’s not complete, but we also understand that they’re going to come into the hospital and let us know what things need to be done. We’ll be happy to take that patient a little earlier than we did in the past to get them out of the ED.”

That’s a tricky thing to do, he says, “because the benefit to us isn’t huge, we’re self-sacrificing to help the ED, and that’s what I want hospitalist groups nationally to be thinking: how we can make the whole system better and not just make our own job better.”

Dr. Glasheen believes the professional structure in his institution is representative of what other hospitals will function like in the next 10 years.

“You have a backbone structure of basically four types of physicians: emergency medicine docs, hospitalists, intensivists, and a surgical team,” Dr. Glasheen says. “Everyone else, more and more, is serving in a consultative role.” Having that backbone allows you to tackle the issues, which are primarily complex, systems-based issues, he says. “It is no longer [a matter of just] the ED trying to deal with capacity issues. Now they have an ally on the inpatient side.”

An excess of patients for the number of beds means some patients spend a disproportionate amount of their stay in the ED, and that challenges communication and efficiency. “The challenges may be simple things, such as it being harder for a hospitalist to get to the ED to see a patient than it is upstairs,” Dr. Glasheen says. “[Or] it’s harder to decide who really has ownership of that patient.” In his hospital, as soon as a patient is assigned to a hospitalist, the primary responsibility for that patient is seen as the hospitalist’s.

But there are other issues. “Even if we are able to get down [to the ED] and write orders, that is problematic for the ED and the hospitalist; as a hospitalist we don’t have the nurses with staffing ratios and skills in the ED that they have on floors and in the ICU,” says Dr. Glasheen. “It is not always possible to get things done as efficiently as they probably could if the patients were in a proper unit. Locally and globally in my experience, the biggest issue is: How do you take care of these patients who now spend their inpatient stay in the ED?”

Collaborations, Models, and Solutions

A number of hospitalists raise the issue of managing internal medicine residents doing rotations in the ED.

“We were approached recently by the ED because most of our admissions are called in directly to the medical residents,” says Jason R. Orlinick, MD, PhD, head of the section of Hospital Medicine at Norwalk Hospital, Conn. “I think the ED would like to talk directly with the medical attending assuming care for the patient. One of the things we haven’t done well is meet on a regular basis to discuss communication issues.”

The hospitalists and emergency medicine group at Dr. Orlinick’s institution have entertained the idea of setting up a direct triage system whereby medical residents are taken out of the picture. “The emergency medicine docs would page us directly—at least during the busiest hours of the day. Eventually, the hope is to make it a 24-hour, seven-days-a-week, 365 [days-a-year process],” says Dr. Orlinick. By bringing this to the emergency medicine physicians, the intent was to send the message that hospitalists recognize ED overcrowding as an institutional issue and want to improve communication with their ED colleagues to improve patient care.

This model, devised at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center in Baltimore, enabled communication between ED doctors and hospitalists, and reduced wait times by more than two hours when a bed was available.2 This triage and direct-admission protocol was not associated with increased mortality and resulted in improved patient and physician satisfaction. (See Figure 2 at right). Once the ED attending decides to admit a patient, direct communication is facilitated with a hospitalist. The approach includes monthly meetings between the department of medicine and the ED to continue to discuss improvements in admissions.

At Norwalk Hospital, the administration asked the hospitalist group to intervene in that throughput process. But Dr. Orlinick, also a clinical instructor of medicine at Yale University in New Haven, Conn., says they’ve hesitated out of sensitivity to their ED colleagues.

“We as a group have really struggled with that concept because [although] we feel like that is something we can do well, this is really within the purview of the emergency medicine docs,” says Dr. Orlinick. Adopting the Johns Hopkins model is a win-win solution where each specialty is providing its best skills to solve mutual issues. “What we can do well is look at the patients … on the floor[s], look at flow through the hospital systems in terms of getting testing; make sure that all that—and consults—happen in a timely manner, and that people leave the hospital when they’ve reached their goals of hospitalization,” he says. “It’s afterload as opposed to preload.”

Hospitalists see committee collaboration as important to solving the complex multidisciplinary systemic issues. Jasen W. Gundersen, MD, participates on a pneumonia task force with several hospitalists, a pulmonologist, and one of the heads of the ED. “We address the whole gamut from when patients come in to when they go through the hospital,” says Dr. Gundersen, head of the Hospital Medicine Division, University of Massachusetts Memorial Medical Center, Worcester. “We can learn from each other as we go through the process.”

Many of the ways hospitalists and ED physicians tackle systems-related issues are new to Dr. Glasheen’s institution because the hospital medicine program was begun in 2004. It is now common to see higher-level leadership from different specialties and areas all in the same room—talking about issues of capacity, for instance. There are also many more instances of hospitalists and ED physicians sitting on the same committees. Further, “It is relatively common for our ED to call our hospitalists to say, ‘Can you help see this patient? I’m not sure what to do,’ or, ‘I’ve got this situation with this patient, this needs to be done and I need help getting that done,’ ” Dr. Glasheen says. Even though he concedes that is more of a workaround as opposed to a solution for a faulty system, it still represents ED physicians and hospitalists co-managing that workaround.

The Future

Because he “sits on both sides of the fence” between emergency medicine and hospital medicine, Dr. Gundersen thinks it is especially important for hospitalists to train in all the different areas—including emergency medicine—when they are medical students and residents.

Emergency medicine physicians Dr. Hoekstra and Benjamin Honigman, MD, professor of surgery and head of the Division of Emergency Medicine at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, Denver, believe hospital medicine will be integral to that training. Dr. Glasheen, also the director of the longest-running internal medicine hospitalist-training program in the U.S., expects greater attention to hospitalist training. “My sense is that many hospitalists groups are in a growth phase and are trying to solve their own problems,” he says. Basically, their primary focus is staffing the hospital with good people and retaining them. He believes that once groups have been around for three to five years, they are more likely to take on bigger issues, such as hospital efficiency and capacity management.

“One of the reasons we started a hospitalist training program is that I didn’t want hospitalists to fall into the same mistakes, barriers, or issues that we’ve had in the past,” Dr. Glasheen says. He fears “this sort of continued balkanization of hospital care, where everyone silos everything out and considers such issues as throughput and ED divert as outside of their [jurisdiction]. I want to get to the place where hospitalists are looking at the whole hospital system and are justly rewarded for that either by financial incentives or time to [work on systemic issues].”

Dr. Glasheen and his team remind themselves of where their commitment resides: “This hospital is where we live—and with everything between the front door to the back door, our primary job is to make this a better place.” TH

Andrea Sattinger is a frequent contributor to The Hospitalist.

References

- Burt CW, McCaig LF. Staffing, capacity, and ambulance diversion in emergency departments: United States, 2003-04. Adv Data; US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, Hyattsville, Md. Sept. 27, 2006. Available at: www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ad/ad376.pdf. Last accessed June 25, 2007.

- Howell EE, Bessman ES, Rubin HR. Hospitalists and an innovative emergency department admission process. J Gen Intern Med. 2004 Mar;19(3):266-268.

Heinous Crimes

By the time a mortician in the northeast British town of Hyde, Greater Manchester, United Kingdom, noticed Dr. Harold Shipman’s patients were dying at an exorbitant rate, the doctor had probably killed close to 300 of them, according to Kenneth V. Iserson, MD, MBA, professor of emergency medicine at the University of Arizona College of Medicine and author of “Demon Doctors: Physicians as Serial Killers.”

Shipman, labeled ‘‘the most prolific serial killer in the history of the United Kingdom—and probably the world,’’ was officially convicted of killing 15 patients in 2000 and sentenced to 15 consecutive life sentences.1 In January 2004 he was found hanged in his prison cell.

Sometimes referred to as caregiver-associated serial killings, these incidents generate profound shock in the healthcare community. As repellent and relatively rare as this behavior is, and as controversial as the topic is, neither individuals nor institutions can afford to disassociate themselves from the subject. Hospitalists should not hide from this issue and should not feel they will be accused of “treason” if they educate themselves and bring suspicious behavior to the awareness of superiors, says Beatrice Crofts Yorker, JD, RN, MS, FAAN, dean of the College of Health and Human Services at California State University, Los Angeles. On the contrary, she says, “first, do no harm” also entails ensuring everyone else around you follows the same ethic.

Dr. Yorker, who has been studying this phenomenon since 1986, published the first examination of cases of serial murder by nurses in the American Journal of Nursing (AJN) in 1988. “It is a serious problem that has been under-recognized, and it is the right thing to blow the whistle when adverse patient incidents are associated with the presence of a specific healthcare provider,” says Dr. Yorker. “In fact, most of the cases came to the attention of authorities because a nurse blew the whistle. The sad thing is that some of the nurses were disciplined for their protective actions; however, they were ultimately vindicated.”

A veteran of the phenomenon urges continued vigilance. “As a general caveat, there needs to be a higher index of suspicion for these incidents,” says Kenneth W. Kizer, MD, MPH, the former head of the veterans healthcare system who had to deal with three incidents of serial murder at Veterans Affairs (VA) hospitals in the 1990s. “These incidents are grossly underreported.”

Incidence and Cause of Death

Drs. Kizer and Yorker were two of the investigators who reviewed epidemiologic studies, toxicology evidence, and court transcripts for data on healthcare professionals prosecuted between 1970 and 2006.

“Dr. Robert Forrest, who was a forensic toxicologist getting a law degree and wrote his dissertation on the topic of serial murder by healthcare providers, contacted me after the AJN article came out,” says Dr. Yorker. Dr. Forrest has been the testifying expert in most of the U.K. cases. “After the Charles Cullen case hit the news, The New York Times and Modern Healthcare contacted me regarding my study in AJN and the Journal of Nursing Law. That is how Ken Kizer and Paula Lampe found me.” (Cullen, a registered nurse, received 11 consecutive life sentences in 2006 after pleading guilty to administering lethal doses of medication to more than 40 patients in New Jersey and Pennsylvania.)

Lampe, an author, had been studying cases in Europe. “Because both Robert and Paula provided additional data on some cases, they were co-authors—as was Ken—who provided data on the VA cases and an important public policy perspective,” says Dr. Yorker.

The search showed 90 criminal prosecutions of healthcare providers who met the criteria of serial murder of patients. Of those, 54 have been convicted—45 for serial murder, four for attempted murder, and five on lesser charges. Since the publication of their study, one more of the accused has received a sentence of life in prison, another has been convicted and sentenced to 20 years, one committed suicide in prison, and two additional nurses in Germany and the Czech Republic have been arrested and confessed to serial murder of patients. In addition, Dr. Yorker is continuing to follow two large-scale murder-for-profit prosecutions. There are four defendants in each case. Further, three individuals have been found liable for wrongful death in the amounts of $27 million, $8 million, and $450,000 in damages.

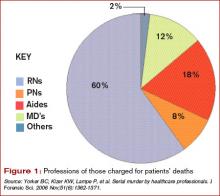

Injection was the main method used by healthcare killers, followed by suffocation, poisoning, and tampering with equipment. Prosecutions were reported in 20 countries, with 40% of the incidents taking place in the United States. Nursing personnel were 86% of the healthcare providers prosecuted; 12% were physicians, and 2% were allied health professionals. The number of patient deaths that resulted in a murder conviction is 317, and the number of suspicious patient deaths attributed to the 54 convicted caregivers is 2,113.

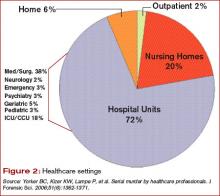

“Physicians as serial killers are remarkably uncommon,” says Dr. Iserson, who is also director of the Arizona Bioethics Program at the University of Arizona College of Medicine in Tucson. “Nurses [who are serial killers] are much more common, but of course there are more nurses in the hospital, just as there are ancillary people.” (See Figure 1, left.) Dr. Iserson, who practices emergency medicine and consults nationally on bioethics, advises maintaining caution when examining data of charges or suspicions that were never proved.

Most of these crimes (70%) occur in hospital units. (See Figure 2, left.) Victims are almost always female, as are almost half (49%) of convicted serial killers and 55% of the total number of prosecuted healthcare providers. Males are disproportionately represented among prosecuted nurses.

Motives: Who Is Always There?

Although the motives are complex, some common threads connect these crimes. “There are some classical signs, if you will,” says Dr. Kizer.

When the same person repeatedly calls a code and always seems to be in the thick of it, that is one prime indicator. These people are usually legitimately present in those settings and circumstances—for example, they are on call or working a shift—which makes it more difficult to discern when something is awry. Commonly, the perpetrators have easy access to high-alert drugs without sufficient accountability. Sometimes, once an investigation has been launched it is discovered the person has falsified his or her credentials.

In hospitals, experts say, the “rescuer” or “hero” personality is often on display in those who kill patients—the first person there to give the patient drugs or attempt to save the patient.

“What you are going to see as a pattern,” says Dr. Iserson, “is that they need to be near death.” Codes or calls for respiratory arrest are the most common; patients who have cardiac arrests are much harder to save. Being the hero is not always the motive; the converse can also apply.

Such is the case with nurse Orville Lynn Majors, LPN, convicted of six murders at the Vermillion county hospital in Clinton, Ind. The deaths were consistent with injections of potassium chloride and epinephrine according to prosecutors. Majors’ coworkers were concerned that patients were coding in alarming numbers while in his care. Although this information did not come out until after he was apprehended, his coworkers had a good idea which of his patients would not survive: Patients who were whiny, demanding, or required a lot of work. “The scuttlebutt or rumor among his coworkers,” says Dr. Kizer, “is that they could almost predict which patients would have a demise under his care.”

Although a typical profile of the serial healthcare murderer has been demonstrated in many cases, in many other cases the demographics and behaviors of these killers have deviated widely from generalized assumptions.2 Therefore, before looking at people, look at the numbers.

An unusual number of calls and codes may occur in a particular area of the hospital. “In ICUs you expect a lot of [codes and calls], but not on general post-op wards or the pediatrics MICU,” Dr. Kizer says. “When this happens in these settings it should raise a red flag.”

Unfortunately, most hospitals don’t track mortality on a monthly basis per unit or ward or ICU, so they may not recognize when something is out of line in a timely manner. Also, the hospital committee assigned to review deaths may be remiss in its duty to meet regularly or otherwise perform according to policy.

Another factor that should raise a red flag is a disproportionate number of codes or deaths on the same shift—most often the night shift. Often, someone says, “Gee, it seems like there’s an awful lot of codes lately,” explains Dr. Kizer. An unusually high rate of successful codes is another sign.

For example, in the 1995-1996 case of Kristen Gilbert, an RN convicted of four murders at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Northampton, Mass., she was having an extramarital affair with a hospital security guard who worked the evening shift. Protocol required that security be called to all cardiopulmonary arrests. Gilbert used stimulant epinephrine to make their hearts race out of control. The epidemiologic data later showed that suspicious codes occurred when both were on duty. “The patients always seemed to recover and she was the hero,” says Dr. Kizer. “She wanted to look good for her boyfriend.”