User login

Identifying Observation Stays in Medicare Data: Policy Implications of a Definition

Medicare observation stays are increasingly common. From 2006 to 2012, Medicare observation stays increased by 88%,1 whereas inpatient discharges decreased by 13.9%.2 In 2012, 1.7 million Medicare observation stays were recorded, and an additional 700,000 inpatient stays were preceded by observation services; the latter represented a 96% increase in status change since 2006.1 Yet no standard research methodology for identifying observation stays exists, including methods to identify and properly characterize “status change” events, which are hospital stays where initial and final inpatient or outpatient (observation) statuses differ.

With the increasing number of hospitalized patients classified as observation, a standard methodology for Medicare claims research is needed so that observation stays can be consistently identified and potentially included in future quality measures and outcomes. Existing research studies and government reports use widely varying criteria to identify observation stays, often lack detailed methods on observation stay case finding, and contain limited information on how status changes between inpatient and outpatient (observation) statuses are incorporated. This variability in approach may lead to omission and/or miscategorization of events and raises concern about the comparability of prior work.

This study aimed to determine the claims patterns of Medicare observation stays, define comprehensive claims-based methodology for future Medicare observation research and data reporting, and identify policy implications of such definition. We are poised to do this work because of our access to the nationally generalizable Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) linked Part A inpatient and outpatient data sets for 2013 and 2014, as well as our prior expertise in hospital observation research and Medicare claims studies.

METHODS

General Methods and Data Source

A 2014 national 20% random sample Part A and B Medicare data set was used. In accordance with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid (CMS) data use agreement, all included beneficiaries had at least 1 acute care inpatient hospitalization. Included beneficiaries were enrolled for 12 months prior to their first 2014 inpatient stay. Those with Medicare Advantage or railroad benefits were excluded because of incomplete data per prior methods.3 The University of Wisconsin Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Comparison of Methods

The PubMED query “Medicare AND (observation OR observation unit),” limited to English and publication between January 1, 2010 and October 1, 2017, was conducted to determine the universe of prior observation stay definitions used in research for comparison (Appendix).4-20 The Office of Inspector General report,21 the Research Data Assistance Center (ResDAC),22 and Medicare Claims Processing Manual (MCPM)23 were also included. Methods stated in each publication were used to extrapolate observation stay case finding to the study data set.

Observation Stay Case Finding

Inpatient and outpatient revenue centers were queried for observation revenue center (ORC) codes identified by ResDAC,22 including 0760 (Treatment or observation room - general classification), 0761 (Treatment or observation room - treatment room), 0762 (Treatment or observation room – observation room), and 0769 (Treatment or observation room – other) occurring within 30 days of an inpatient stay. Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) codes G0378 (Hospital observation service, per hour) and G0379 (Direct referral of patient for hospital observation care) were included per MCPM.23 A combination of these ORC and HCPCS codes was also used to identify observation stays in every Medicare claims observation study since 2010. When more than one ORC code per event was found, each ORC was recorded as part of that event. Presence of HCPCS G0378 and/or G0379 was determined for each event in association with event ORC(s), as was association of ORC codes with inpatient claims. In this manuscript, “observation stay” refers to an observation hospital stay, and “event” refers to a hospitalization that may include inpatient and/or outpatient (observation) services and ORC codes.

Status Change

All ORC codes found in the inpatient revenue center were assumed to represent status changes from outpatient (observation) to inpatient, as ORC codes may remain in claims data when the status changes to inpatient.24 Therefore, all events with ORC codes in the inpatient revenue center were considered inpatient hospitalizations.

For each ORC code found in the outpatient revenue center and also associated with an inpatient claim, timing of the ORC code in the inpatient claim was grouped into four categories to determine events with the final status of outpatient (observation stay). ResDAC defines the “From” date as “…the first day on the billing statement covering services rendered to the beneficiary.”24 For most hospitals, this is a three-day period prior to an inpatient admission where outpatient services are included in the Part A claim.25 We defined Category 1 as ORC codes occurring prior to claim “From” date; Category 2 as ORC codes on the inpatient “From” date, between the inpatient “From” date and admission date, or on the admission date; Category 3 as ORC codes between admission and discharge dates; and Category 4 as ORC codes occurring on or after the discharge date. Given that Category 4 represents the final hospitalization status, we considered Category 4 ORC codes in the outpatient revenue center associated with inpatient claims to be observation stays that had undergone a status change from inpatient to outpatient (observation).

University of Wisconsin Method

After excluding ORC codes in the inpatient revenue center as true inpatient hospitalizations, we defined an observation stay as 0760 and/or 0761 and/or 0762 and/or 0769 in the outpatient revenue center and having no association with an inpatient claim. To address a status change from inpatient to outpatient (observation), for those ORC codes in the outpatient revenue center also associated with an inpatient claim, claims with ORC codes in Category 4 were also considered observation stays.

RESULTS

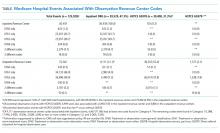

Of 1,667,660 hospital events, 125,920 (7.6%) had an ORC code within 30 days of an inpatient hospitalization, of which 50,418 (3.0%) were found in the inpatient revenue center and 75,502 (4.5%) were from the outpatient revenue center. A total of 59,529 (47.3%) ORC codes occurred with an inpatient claim (50,418 in the inpatient revenue center and 9,111 in the outpatient revenue center), 5,628 (4.5%) had more than one ORC code on a single hospitalization, and more than 90% of codes were 0761 or 0762. These results illustrated variability in claims submissions as measured by the claims themselves and demonstrated a high rate of status changes (Table).

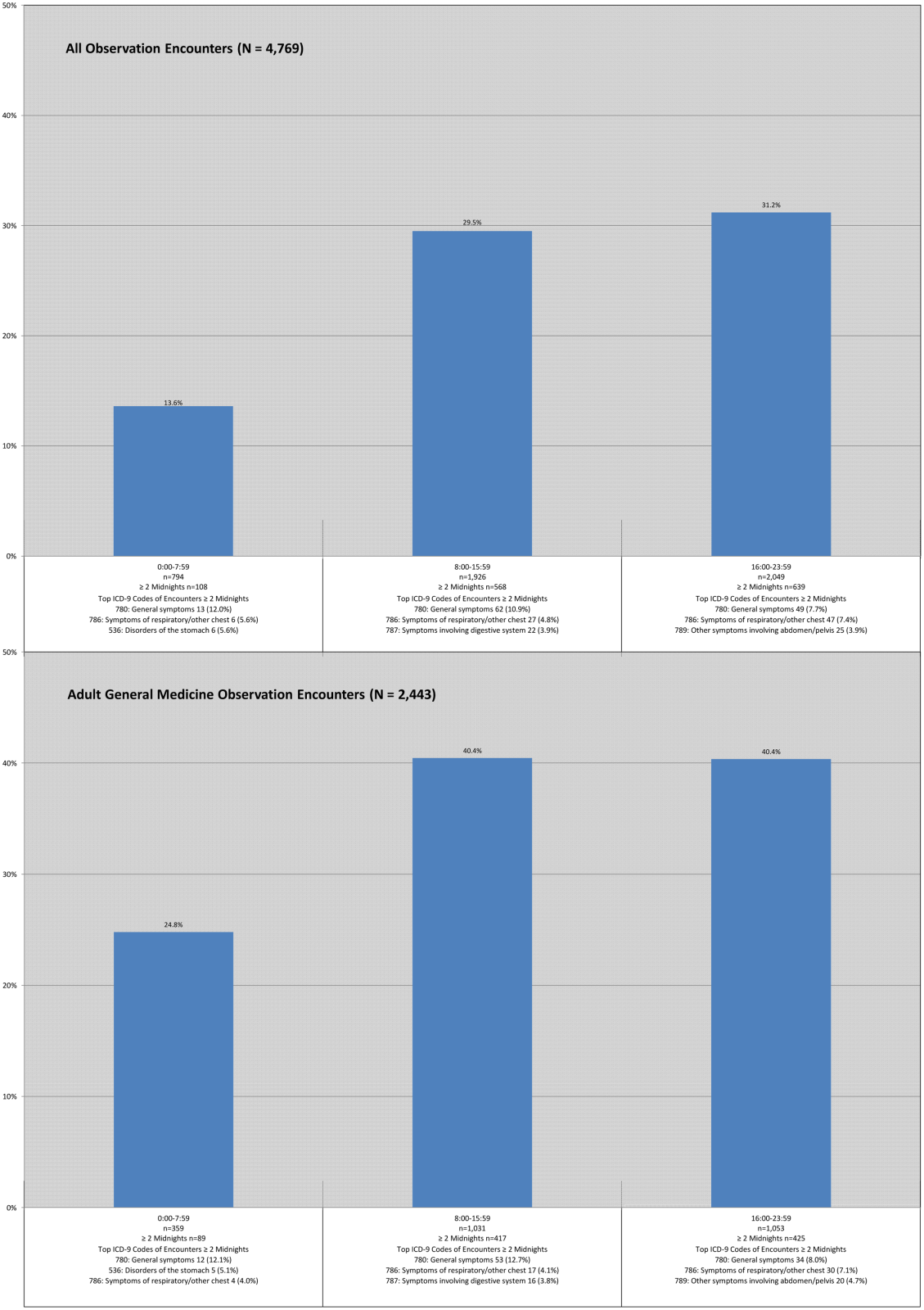

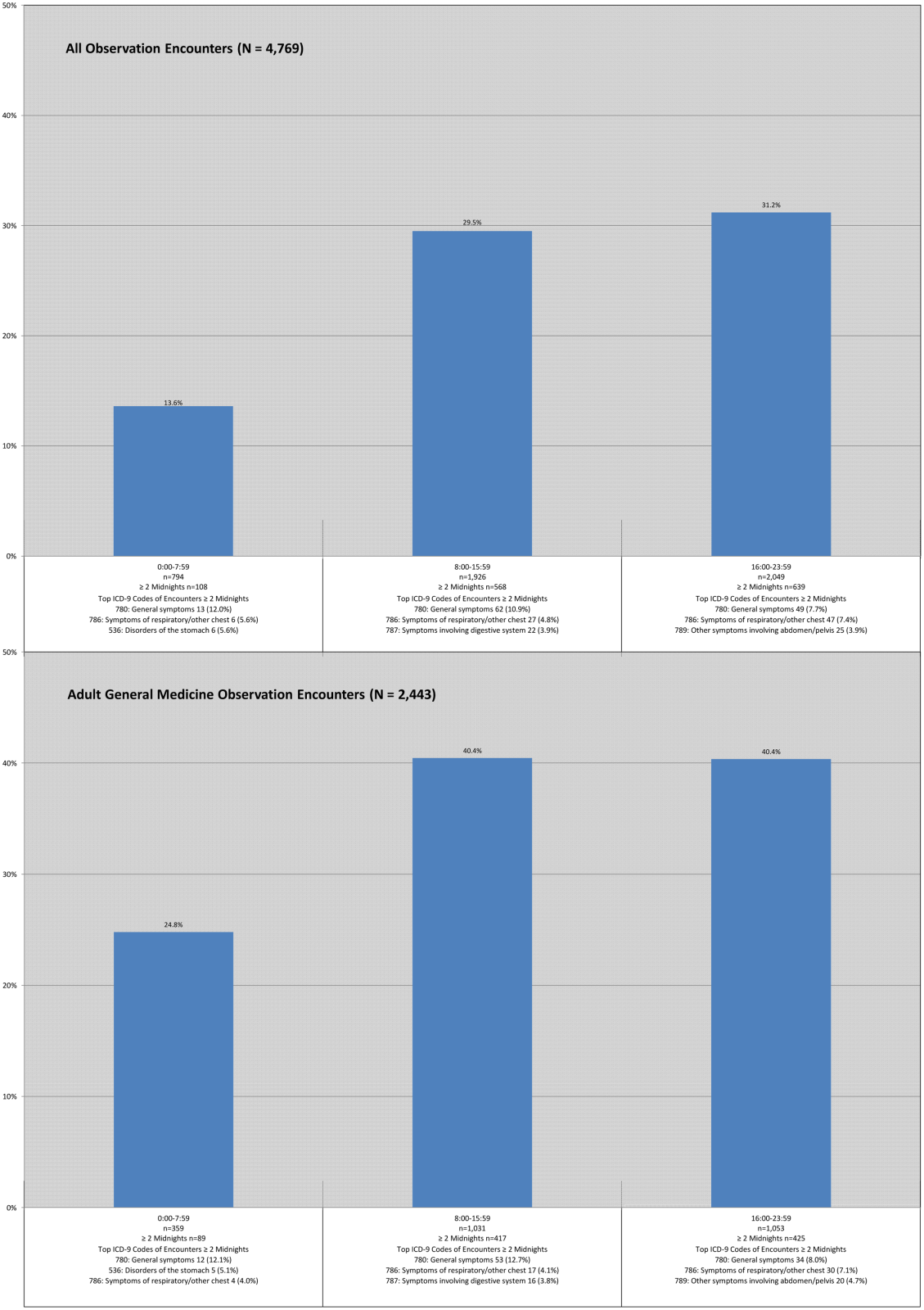

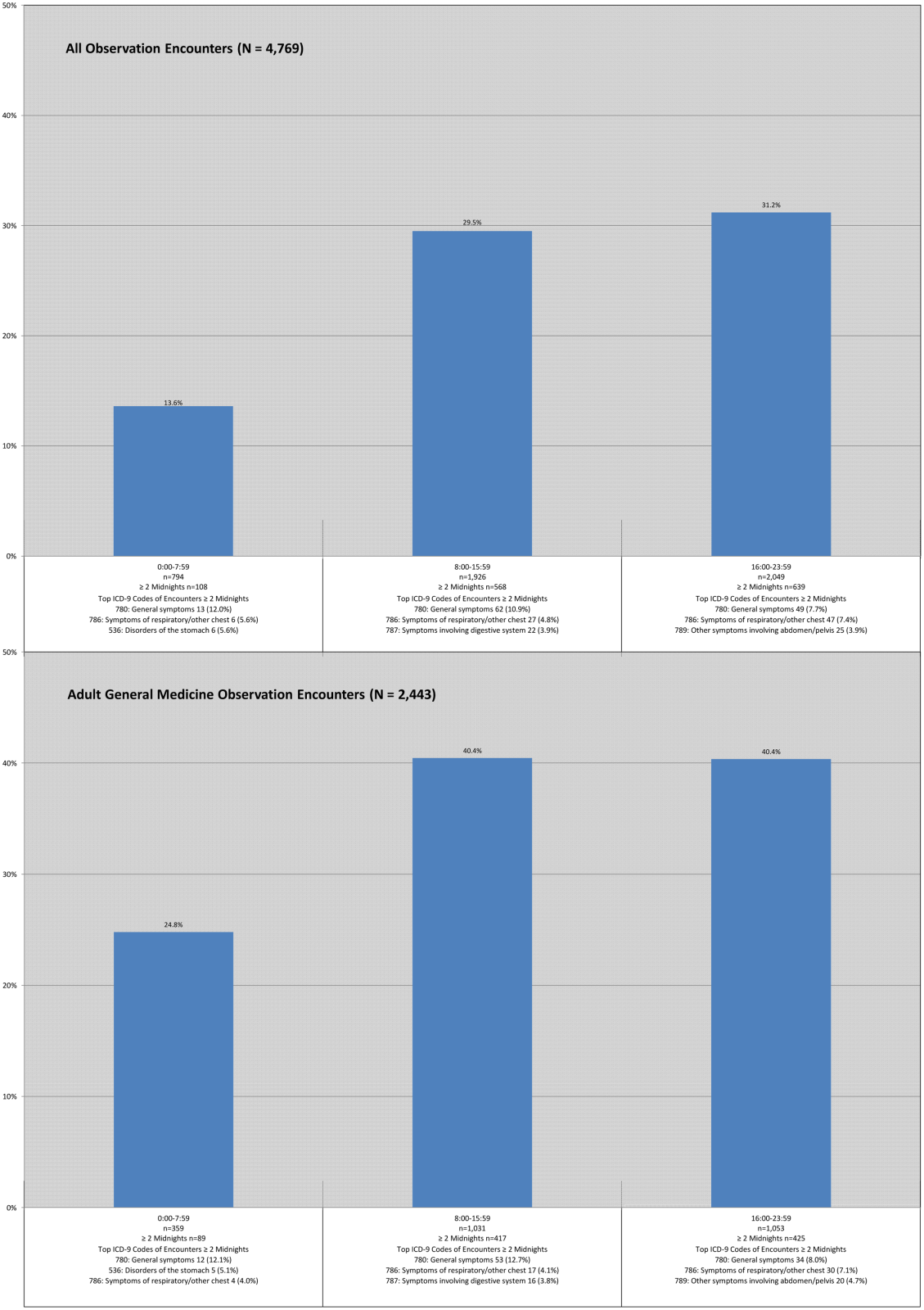

Observation stay definitions varied in the literature, with different methods capturing variable numbers of observation stays (Figure, Appendix). No methods clearly identified how to categorize events with status changes, directly addressed ORC codes in the inpatient revenue center, or discussed events with more than one ORC code. As such, some assumptions were made to extrapolate observation stay case findings as detailed in the Figure (see also Appendix). Notably, reference 4 methods were obtained via personal communication with the manuscript’s first author. The University of Wisconsin definition offers a comprehensive definition that classifies status change events, yielding 72,858 of 75,502 (96.5%) potential observation events as observation stays (Figure). These observation stays include 66,391 stays with ORC codes in the outpatient revenue center without status change or relation to inpatient claim, and 6467 (71.0%) of 9111 events with ORC codes in the outpatient revenue center were associated with an inpatient claim where ORC code(s) is located in Category 4.

CONCLUSIONS

This study confirmed the importance of a standard observation stay case finding methodology. Variability in prior methodology resulted in studies that may have included less than half of potential observation stays. In addition, most studies did not include, or were unclear, on how to address the increasing number of status changes. Others may have erroneously included hospitalizations that were ultimately billed as inpatient, and some publications lacked sufficient detailed methodology to extrapolate results with absolute certainty, a limitation of our comparative results. Although excluding some ORC codes in the outpatient revenue center associated with inpatient claims may possibly miss some observation stays, or including certain ORC codes, such as 0761 (treatment or observation room - treatment room), may erroneously include a different type of observation stay, the proposed University of Wisconsin method could be used as a comprehensive and reproducible method for observation stay case finding, including encounters with status change.

This study has other important policy implications. More than 90% of ORC codes were either 0761 or 0762, and in almost one in 20 claims, two or more distinct codes were identified. Given the lack of clinical relevance of terms “treatment” or “observation” room, and the frequency of more than 1 ORC code per claim, CMS may consider simplification to a single ORC code. Studies of observation encounter length of stay by hour may require G0378 in addition to an ORC code to define an observation stay, but doing so eliminates nearly half of observation claims. Additionally, G0379 adds minimal value to G0378 in case finding.

Finally, this study illustrates overall confusion with outpatient (observation) and inpatient status designations, with almost half (47.3%) of all hospitalizations with ORC codes also associated with an inpatient claim, demonstrating a high status change rate. More than 40% of all nurse case manager job postings are now for status determination work, shifting duties from patient care and quality improvement.26 We previously demonstrated a need for 5.1 FTE combined physician, attorney, and other personnel to manage the status, audit, and appeals process per institution.27 The frequency of status changes and personnel needed to maintain a two-tiered billing system argues for a single hospital status.

In summary, our study highlights the need for federal observation policy reform. We propose a standardized and reproducible approach for Medicare observation claims research, including status changes that can be used for further studies of observation stays.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jinn-ing Liou for analyst support, Jen Birstler for figure creation, and Carol Hermann for technical support. This work was supported by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01MD010243 (Dr. Kind).

Disclosures

The authors have no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose.Funding: This work was supported by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01MD010243 (

1. MedPAC Report to Congress. June 2015, Chapter 7. Hospital short-stay policy issues. http://medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/june-2015-report-to-the-congress-medicare-and-the-health-care-delivery-system.pdf?sfvrsn=0. Accessed December 21, 2017.

2. MedPAC Report to Congress. March 2017, Chapter 3. Hospital inpatient and outpatient services. http://medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/mar17_entirereport224610adfa9c665e80adff00009edf9c.pdf?sfvrsn=0. Accessed December 21, 2017.

3. Kind A, Jencks S, Crock J, et al. Neighborhood socioecomonic disadvantage and 30-day reshospitalization: a retrospective cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(11):765-774. doi: 10.7326/M13-2946. PubMed

4. Zuckerman R, Sheingold S, Orav E, Ruhter J, Epstein A. Readmissions, observation, and the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program. NEJM. 2016;374(16):1543-1551. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1513024. PubMed

5. Hockenberry J, Mutter R, Barrett M, Parlato J, Ross M. Factors associated with prolonged observation services stays and the impact of long stays on patient cost. Health Serv Res. 2014;49(3):893-909. 10.1111/1475-6773.12143. PubMed

6. Goldstein J, Zhang Z, Schwartz S, Hicks L. Observation status, poverty, and high financial liability among Medicare beneficiaries. Am J Med. 2017;131(1):e9-101.e15. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.07.013. PubMed

7. Feng Z, Wright B, Mor V. Sharp rise in Medicare enrollees being held in hospitals for observation raises concerns about causes and consequences. Health Aff. 2012;31(6):1251-1259. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0129. PubMed

8. Feng Z, Jung H-Y, Wright B, Mor V. The origin and disposition of Medicare observation stays. Med Care. 2014;52(9):796-800. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000179 PubMed

9. Wright B, Jung H-Y, Feng Z, Mor V. Hospital, patient, and local health system characteristics associated with the prevalence and duration of observation care. HSR. 2014;49(4):1088-1107. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12166. PubMed

10. Overman R, Freburger J, Assimon M, Li X, Brookhart MA. Observation stays in administrative claims databases: underestimation of hospitalized cases. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2014;23(9):902-910. doi: 10.1002/pds.3647. PubMed

11. Vashi A, Cafardi S, Powers C, Ross J, Shrank W. Observation encounters and subsequent nursing facility stays. Am J Manag Care. 2015;21(4):e276-e281. PubMed

12. Venkatesh A, Wang C, Ross J, et al. Hospital use of observation stays: cross-sectional study of the impact on readmission rates. Med Care. 2016;54(12):1070-1077. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000601 PubMed

13. Gerhardt G, Yemane A, Apostle K, Oelschlaeger A, Rollins E, Brennan N. Evaluating whether changes in utilization of hospital outpatient services contributed to lower Medicare readmission rate. MMRR. 2014;4(1):E1-E13. doi: 10.5600/mmrr2014-004-01-b03 PubMed

14. Lipitz-Snyderman A, Klotz A, Gennarelli R, Groeger J. A population-based assessment of emergency department observation status for older adults with cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2017;15(10):1234-1239. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2017.0160. PubMed

15. Kangovi S, Cafardi S, Smith R, Kulkarni R, Grande D. Patient financial responsibility for observation care. J Hosp Med. 2015;10:718-723. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2436. PubMed

16. Dharmarajan K, Qin L, Bierlein M, et al. Outcomes after observation stays among older adult Medicare beneficiaries in the USA: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2017;357:j2616. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j2616 PubMed

17. Baier R, Gardner R, Coleman E, Jencks S, Mor V, Gravenstein S. Shifting the dialogue from hospital readmissions to unplanned care. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(6):450-453. PubMed

18. Cafardi S, Pines J, Deb P, Powers C, Shrank W. Increased observation services in Medicare beneficiaries with chest pain. Am J Emergency Med. 2016;34(1):16-19. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2015.08.049. PubMed

19. Nuckols T, Fingar K, Barrett M, Steiner C, Stocks C, Owens P. The shifting landscape in utilization of inpatient, observation, and emergency department services across payors. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(6):443-446. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2751. PubMed

20. Wright B, Jung H-Y, Feng Z, Mor V. Trends in observation care among Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries at critical access hospitals, 2007-2009. J Rural Health. 2013;29(1):s1-s6. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12007 PubMed

21. Office of Inspector General. Vulnerabilites remain under Medicare’s 2-Midnight hospital policy. 12-9-2016. https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-02-15-00020.asp. Accessed December 27, 2017. PubMed

22. Research Data Assistance Center (ResDAC). Revenue center table. https://www.resdac.org/sites/resdac.umn.edu/files/Revenue%20Center%20Table.txt. Accessed December 26, 2017.

23. Medicare Claims Processing Manual, Chapter 4, Section 290, Outpatient Observation Services. https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads/clm104c04.pdf. Accessed December 26, 2017.

24. Research Data Assistance Center (ResDAC). Identifying observation stays for those beneficiaries admitted to the hospital. https://www.resdac.org/resconnect/articles/172. Accessed December 27, 2017.

25. Medicare Claims Processing Manual, Chapter 3, Section 40.B. Outpatient services treated as inpatient services. https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/Downloads/clm104c03.pdf. Accessed December 26, 2017.

26. Reynolds J. Another look at roles and functions: has hospital case management lost its way? Prof Case Manag. 2013;18(5):246-254. doi: 10.1097/NCM.0b013e31829c8aa8. PubMed

27. Sheehy A, Locke C, Engel J, et al. Recovery audit contractor audit and appeals at three academic medical centers. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(4):212-219. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2332. PubMed

Medicare observation stays are increasingly common. From 2006 to 2012, Medicare observation stays increased by 88%,1 whereas inpatient discharges decreased by 13.9%.2 In 2012, 1.7 million Medicare observation stays were recorded, and an additional 700,000 inpatient stays were preceded by observation services; the latter represented a 96% increase in status change since 2006.1 Yet no standard research methodology for identifying observation stays exists, including methods to identify and properly characterize “status change” events, which are hospital stays where initial and final inpatient or outpatient (observation) statuses differ.

With the increasing number of hospitalized patients classified as observation, a standard methodology for Medicare claims research is needed so that observation stays can be consistently identified and potentially included in future quality measures and outcomes. Existing research studies and government reports use widely varying criteria to identify observation stays, often lack detailed methods on observation stay case finding, and contain limited information on how status changes between inpatient and outpatient (observation) statuses are incorporated. This variability in approach may lead to omission and/or miscategorization of events and raises concern about the comparability of prior work.

This study aimed to determine the claims patterns of Medicare observation stays, define comprehensive claims-based methodology for future Medicare observation research and data reporting, and identify policy implications of such definition. We are poised to do this work because of our access to the nationally generalizable Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) linked Part A inpatient and outpatient data sets for 2013 and 2014, as well as our prior expertise in hospital observation research and Medicare claims studies.

METHODS

General Methods and Data Source

A 2014 national 20% random sample Part A and B Medicare data set was used. In accordance with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid (CMS) data use agreement, all included beneficiaries had at least 1 acute care inpatient hospitalization. Included beneficiaries were enrolled for 12 months prior to their first 2014 inpatient stay. Those with Medicare Advantage or railroad benefits were excluded because of incomplete data per prior methods.3 The University of Wisconsin Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Comparison of Methods

The PubMED query “Medicare AND (observation OR observation unit),” limited to English and publication between January 1, 2010 and October 1, 2017, was conducted to determine the universe of prior observation stay definitions used in research for comparison (Appendix).4-20 The Office of Inspector General report,21 the Research Data Assistance Center (ResDAC),22 and Medicare Claims Processing Manual (MCPM)23 were also included. Methods stated in each publication were used to extrapolate observation stay case finding to the study data set.

Observation Stay Case Finding

Inpatient and outpatient revenue centers were queried for observation revenue center (ORC) codes identified by ResDAC,22 including 0760 (Treatment or observation room - general classification), 0761 (Treatment or observation room - treatment room), 0762 (Treatment or observation room – observation room), and 0769 (Treatment or observation room – other) occurring within 30 days of an inpatient stay. Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) codes G0378 (Hospital observation service, per hour) and G0379 (Direct referral of patient for hospital observation care) were included per MCPM.23 A combination of these ORC and HCPCS codes was also used to identify observation stays in every Medicare claims observation study since 2010. When more than one ORC code per event was found, each ORC was recorded as part of that event. Presence of HCPCS G0378 and/or G0379 was determined for each event in association with event ORC(s), as was association of ORC codes with inpatient claims. In this manuscript, “observation stay” refers to an observation hospital stay, and “event” refers to a hospitalization that may include inpatient and/or outpatient (observation) services and ORC codes.

Status Change

All ORC codes found in the inpatient revenue center were assumed to represent status changes from outpatient (observation) to inpatient, as ORC codes may remain in claims data when the status changes to inpatient.24 Therefore, all events with ORC codes in the inpatient revenue center were considered inpatient hospitalizations.

For each ORC code found in the outpatient revenue center and also associated with an inpatient claim, timing of the ORC code in the inpatient claim was grouped into four categories to determine events with the final status of outpatient (observation stay). ResDAC defines the “From” date as “…the first day on the billing statement covering services rendered to the beneficiary.”24 For most hospitals, this is a three-day period prior to an inpatient admission where outpatient services are included in the Part A claim.25 We defined Category 1 as ORC codes occurring prior to claim “From” date; Category 2 as ORC codes on the inpatient “From” date, between the inpatient “From” date and admission date, or on the admission date; Category 3 as ORC codes between admission and discharge dates; and Category 4 as ORC codes occurring on or after the discharge date. Given that Category 4 represents the final hospitalization status, we considered Category 4 ORC codes in the outpatient revenue center associated with inpatient claims to be observation stays that had undergone a status change from inpatient to outpatient (observation).

University of Wisconsin Method

After excluding ORC codes in the inpatient revenue center as true inpatient hospitalizations, we defined an observation stay as 0760 and/or 0761 and/or 0762 and/or 0769 in the outpatient revenue center and having no association with an inpatient claim. To address a status change from inpatient to outpatient (observation), for those ORC codes in the outpatient revenue center also associated with an inpatient claim, claims with ORC codes in Category 4 were also considered observation stays.

RESULTS

Of 1,667,660 hospital events, 125,920 (7.6%) had an ORC code within 30 days of an inpatient hospitalization, of which 50,418 (3.0%) were found in the inpatient revenue center and 75,502 (4.5%) were from the outpatient revenue center. A total of 59,529 (47.3%) ORC codes occurred with an inpatient claim (50,418 in the inpatient revenue center and 9,111 in the outpatient revenue center), 5,628 (4.5%) had more than one ORC code on a single hospitalization, and more than 90% of codes were 0761 or 0762. These results illustrated variability in claims submissions as measured by the claims themselves and demonstrated a high rate of status changes (Table).

Observation stay definitions varied in the literature, with different methods capturing variable numbers of observation stays (Figure, Appendix). No methods clearly identified how to categorize events with status changes, directly addressed ORC codes in the inpatient revenue center, or discussed events with more than one ORC code. As such, some assumptions were made to extrapolate observation stay case findings as detailed in the Figure (see also Appendix). Notably, reference 4 methods were obtained via personal communication with the manuscript’s first author. The University of Wisconsin definition offers a comprehensive definition that classifies status change events, yielding 72,858 of 75,502 (96.5%) potential observation events as observation stays (Figure). These observation stays include 66,391 stays with ORC codes in the outpatient revenue center without status change or relation to inpatient claim, and 6467 (71.0%) of 9111 events with ORC codes in the outpatient revenue center were associated with an inpatient claim where ORC code(s) is located in Category 4.

CONCLUSIONS

This study confirmed the importance of a standard observation stay case finding methodology. Variability in prior methodology resulted in studies that may have included less than half of potential observation stays. In addition, most studies did not include, or were unclear, on how to address the increasing number of status changes. Others may have erroneously included hospitalizations that were ultimately billed as inpatient, and some publications lacked sufficient detailed methodology to extrapolate results with absolute certainty, a limitation of our comparative results. Although excluding some ORC codes in the outpatient revenue center associated with inpatient claims may possibly miss some observation stays, or including certain ORC codes, such as 0761 (treatment or observation room - treatment room), may erroneously include a different type of observation stay, the proposed University of Wisconsin method could be used as a comprehensive and reproducible method for observation stay case finding, including encounters with status change.

This study has other important policy implications. More than 90% of ORC codes were either 0761 or 0762, and in almost one in 20 claims, two or more distinct codes were identified. Given the lack of clinical relevance of terms “treatment” or “observation” room, and the frequency of more than 1 ORC code per claim, CMS may consider simplification to a single ORC code. Studies of observation encounter length of stay by hour may require G0378 in addition to an ORC code to define an observation stay, but doing so eliminates nearly half of observation claims. Additionally, G0379 adds minimal value to G0378 in case finding.

Finally, this study illustrates overall confusion with outpatient (observation) and inpatient status designations, with almost half (47.3%) of all hospitalizations with ORC codes also associated with an inpatient claim, demonstrating a high status change rate. More than 40% of all nurse case manager job postings are now for status determination work, shifting duties from patient care and quality improvement.26 We previously demonstrated a need for 5.1 FTE combined physician, attorney, and other personnel to manage the status, audit, and appeals process per institution.27 The frequency of status changes and personnel needed to maintain a two-tiered billing system argues for a single hospital status.

In summary, our study highlights the need for federal observation policy reform. We propose a standardized and reproducible approach for Medicare observation claims research, including status changes that can be used for further studies of observation stays.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jinn-ing Liou for analyst support, Jen Birstler for figure creation, and Carol Hermann for technical support. This work was supported by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01MD010243 (Dr. Kind).

Disclosures

The authors have no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose.Funding: This work was supported by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01MD010243 (

Medicare observation stays are increasingly common. From 2006 to 2012, Medicare observation stays increased by 88%,1 whereas inpatient discharges decreased by 13.9%.2 In 2012, 1.7 million Medicare observation stays were recorded, and an additional 700,000 inpatient stays were preceded by observation services; the latter represented a 96% increase in status change since 2006.1 Yet no standard research methodology for identifying observation stays exists, including methods to identify and properly characterize “status change” events, which are hospital stays where initial and final inpatient or outpatient (observation) statuses differ.

With the increasing number of hospitalized patients classified as observation, a standard methodology for Medicare claims research is needed so that observation stays can be consistently identified and potentially included in future quality measures and outcomes. Existing research studies and government reports use widely varying criteria to identify observation stays, often lack detailed methods on observation stay case finding, and contain limited information on how status changes between inpatient and outpatient (observation) statuses are incorporated. This variability in approach may lead to omission and/or miscategorization of events and raises concern about the comparability of prior work.

This study aimed to determine the claims patterns of Medicare observation stays, define comprehensive claims-based methodology for future Medicare observation research and data reporting, and identify policy implications of such definition. We are poised to do this work because of our access to the nationally generalizable Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) linked Part A inpatient and outpatient data sets for 2013 and 2014, as well as our prior expertise in hospital observation research and Medicare claims studies.

METHODS

General Methods and Data Source

A 2014 national 20% random sample Part A and B Medicare data set was used. In accordance with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid (CMS) data use agreement, all included beneficiaries had at least 1 acute care inpatient hospitalization. Included beneficiaries were enrolled for 12 months prior to their first 2014 inpatient stay. Those with Medicare Advantage or railroad benefits were excluded because of incomplete data per prior methods.3 The University of Wisconsin Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Comparison of Methods

The PubMED query “Medicare AND (observation OR observation unit),” limited to English and publication between January 1, 2010 and October 1, 2017, was conducted to determine the universe of prior observation stay definitions used in research for comparison (Appendix).4-20 The Office of Inspector General report,21 the Research Data Assistance Center (ResDAC),22 and Medicare Claims Processing Manual (MCPM)23 were also included. Methods stated in each publication were used to extrapolate observation stay case finding to the study data set.

Observation Stay Case Finding

Inpatient and outpatient revenue centers were queried for observation revenue center (ORC) codes identified by ResDAC,22 including 0760 (Treatment or observation room - general classification), 0761 (Treatment or observation room - treatment room), 0762 (Treatment or observation room – observation room), and 0769 (Treatment or observation room – other) occurring within 30 days of an inpatient stay. Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) codes G0378 (Hospital observation service, per hour) and G0379 (Direct referral of patient for hospital observation care) were included per MCPM.23 A combination of these ORC and HCPCS codes was also used to identify observation stays in every Medicare claims observation study since 2010. When more than one ORC code per event was found, each ORC was recorded as part of that event. Presence of HCPCS G0378 and/or G0379 was determined for each event in association with event ORC(s), as was association of ORC codes with inpatient claims. In this manuscript, “observation stay” refers to an observation hospital stay, and “event” refers to a hospitalization that may include inpatient and/or outpatient (observation) services and ORC codes.

Status Change

All ORC codes found in the inpatient revenue center were assumed to represent status changes from outpatient (observation) to inpatient, as ORC codes may remain in claims data when the status changes to inpatient.24 Therefore, all events with ORC codes in the inpatient revenue center were considered inpatient hospitalizations.

For each ORC code found in the outpatient revenue center and also associated with an inpatient claim, timing of the ORC code in the inpatient claim was grouped into four categories to determine events with the final status of outpatient (observation stay). ResDAC defines the “From” date as “…the first day on the billing statement covering services rendered to the beneficiary.”24 For most hospitals, this is a three-day period prior to an inpatient admission where outpatient services are included in the Part A claim.25 We defined Category 1 as ORC codes occurring prior to claim “From” date; Category 2 as ORC codes on the inpatient “From” date, between the inpatient “From” date and admission date, or on the admission date; Category 3 as ORC codes between admission and discharge dates; and Category 4 as ORC codes occurring on or after the discharge date. Given that Category 4 represents the final hospitalization status, we considered Category 4 ORC codes in the outpatient revenue center associated with inpatient claims to be observation stays that had undergone a status change from inpatient to outpatient (observation).

University of Wisconsin Method

After excluding ORC codes in the inpatient revenue center as true inpatient hospitalizations, we defined an observation stay as 0760 and/or 0761 and/or 0762 and/or 0769 in the outpatient revenue center and having no association with an inpatient claim. To address a status change from inpatient to outpatient (observation), for those ORC codes in the outpatient revenue center also associated with an inpatient claim, claims with ORC codes in Category 4 were also considered observation stays.

RESULTS

Of 1,667,660 hospital events, 125,920 (7.6%) had an ORC code within 30 days of an inpatient hospitalization, of which 50,418 (3.0%) were found in the inpatient revenue center and 75,502 (4.5%) were from the outpatient revenue center. A total of 59,529 (47.3%) ORC codes occurred with an inpatient claim (50,418 in the inpatient revenue center and 9,111 in the outpatient revenue center), 5,628 (4.5%) had more than one ORC code on a single hospitalization, and more than 90% of codes were 0761 or 0762. These results illustrated variability in claims submissions as measured by the claims themselves and demonstrated a high rate of status changes (Table).

Observation stay definitions varied in the literature, with different methods capturing variable numbers of observation stays (Figure, Appendix). No methods clearly identified how to categorize events with status changes, directly addressed ORC codes in the inpatient revenue center, or discussed events with more than one ORC code. As such, some assumptions were made to extrapolate observation stay case findings as detailed in the Figure (see also Appendix). Notably, reference 4 methods were obtained via personal communication with the manuscript’s first author. The University of Wisconsin definition offers a comprehensive definition that classifies status change events, yielding 72,858 of 75,502 (96.5%) potential observation events as observation stays (Figure). These observation stays include 66,391 stays with ORC codes in the outpatient revenue center without status change or relation to inpatient claim, and 6467 (71.0%) of 9111 events with ORC codes in the outpatient revenue center were associated with an inpatient claim where ORC code(s) is located in Category 4.

CONCLUSIONS

This study confirmed the importance of a standard observation stay case finding methodology. Variability in prior methodology resulted in studies that may have included less than half of potential observation stays. In addition, most studies did not include, or were unclear, on how to address the increasing number of status changes. Others may have erroneously included hospitalizations that were ultimately billed as inpatient, and some publications lacked sufficient detailed methodology to extrapolate results with absolute certainty, a limitation of our comparative results. Although excluding some ORC codes in the outpatient revenue center associated with inpatient claims may possibly miss some observation stays, or including certain ORC codes, such as 0761 (treatment or observation room - treatment room), may erroneously include a different type of observation stay, the proposed University of Wisconsin method could be used as a comprehensive and reproducible method for observation stay case finding, including encounters with status change.

This study has other important policy implications. More than 90% of ORC codes were either 0761 or 0762, and in almost one in 20 claims, two or more distinct codes were identified. Given the lack of clinical relevance of terms “treatment” or “observation” room, and the frequency of more than 1 ORC code per claim, CMS may consider simplification to a single ORC code. Studies of observation encounter length of stay by hour may require G0378 in addition to an ORC code to define an observation stay, but doing so eliminates nearly half of observation claims. Additionally, G0379 adds minimal value to G0378 in case finding.

Finally, this study illustrates overall confusion with outpatient (observation) and inpatient status designations, with almost half (47.3%) of all hospitalizations with ORC codes also associated with an inpatient claim, demonstrating a high status change rate. More than 40% of all nurse case manager job postings are now for status determination work, shifting duties from patient care and quality improvement.26 We previously demonstrated a need for 5.1 FTE combined physician, attorney, and other personnel to manage the status, audit, and appeals process per institution.27 The frequency of status changes and personnel needed to maintain a two-tiered billing system argues for a single hospital status.

In summary, our study highlights the need for federal observation policy reform. We propose a standardized and reproducible approach for Medicare observation claims research, including status changes that can be used for further studies of observation stays.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jinn-ing Liou for analyst support, Jen Birstler for figure creation, and Carol Hermann for technical support. This work was supported by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01MD010243 (Dr. Kind).

Disclosures

The authors have no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose.Funding: This work was supported by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01MD010243 (

1. MedPAC Report to Congress. June 2015, Chapter 7. Hospital short-stay policy issues. http://medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/june-2015-report-to-the-congress-medicare-and-the-health-care-delivery-system.pdf?sfvrsn=0. Accessed December 21, 2017.

2. MedPAC Report to Congress. March 2017, Chapter 3. Hospital inpatient and outpatient services. http://medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/mar17_entirereport224610adfa9c665e80adff00009edf9c.pdf?sfvrsn=0. Accessed December 21, 2017.

3. Kind A, Jencks S, Crock J, et al. Neighborhood socioecomonic disadvantage and 30-day reshospitalization: a retrospective cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(11):765-774. doi: 10.7326/M13-2946. PubMed

4. Zuckerman R, Sheingold S, Orav E, Ruhter J, Epstein A. Readmissions, observation, and the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program. NEJM. 2016;374(16):1543-1551. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1513024. PubMed

5. Hockenberry J, Mutter R, Barrett M, Parlato J, Ross M. Factors associated with prolonged observation services stays and the impact of long stays on patient cost. Health Serv Res. 2014;49(3):893-909. 10.1111/1475-6773.12143. PubMed

6. Goldstein J, Zhang Z, Schwartz S, Hicks L. Observation status, poverty, and high financial liability among Medicare beneficiaries. Am J Med. 2017;131(1):e9-101.e15. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.07.013. PubMed

7. Feng Z, Wright B, Mor V. Sharp rise in Medicare enrollees being held in hospitals for observation raises concerns about causes and consequences. Health Aff. 2012;31(6):1251-1259. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0129. PubMed

8. Feng Z, Jung H-Y, Wright B, Mor V. The origin and disposition of Medicare observation stays. Med Care. 2014;52(9):796-800. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000179 PubMed

9. Wright B, Jung H-Y, Feng Z, Mor V. Hospital, patient, and local health system characteristics associated with the prevalence and duration of observation care. HSR. 2014;49(4):1088-1107. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12166. PubMed

10. Overman R, Freburger J, Assimon M, Li X, Brookhart MA. Observation stays in administrative claims databases: underestimation of hospitalized cases. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2014;23(9):902-910. doi: 10.1002/pds.3647. PubMed

11. Vashi A, Cafardi S, Powers C, Ross J, Shrank W. Observation encounters and subsequent nursing facility stays. Am J Manag Care. 2015;21(4):e276-e281. PubMed

12. Venkatesh A, Wang C, Ross J, et al. Hospital use of observation stays: cross-sectional study of the impact on readmission rates. Med Care. 2016;54(12):1070-1077. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000601 PubMed

13. Gerhardt G, Yemane A, Apostle K, Oelschlaeger A, Rollins E, Brennan N. Evaluating whether changes in utilization of hospital outpatient services contributed to lower Medicare readmission rate. MMRR. 2014;4(1):E1-E13. doi: 10.5600/mmrr2014-004-01-b03 PubMed

14. Lipitz-Snyderman A, Klotz A, Gennarelli R, Groeger J. A population-based assessment of emergency department observation status for older adults with cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2017;15(10):1234-1239. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2017.0160. PubMed

15. Kangovi S, Cafardi S, Smith R, Kulkarni R, Grande D. Patient financial responsibility for observation care. J Hosp Med. 2015;10:718-723. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2436. PubMed

16. Dharmarajan K, Qin L, Bierlein M, et al. Outcomes after observation stays among older adult Medicare beneficiaries in the USA: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2017;357:j2616. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j2616 PubMed

17. Baier R, Gardner R, Coleman E, Jencks S, Mor V, Gravenstein S. Shifting the dialogue from hospital readmissions to unplanned care. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(6):450-453. PubMed

18. Cafardi S, Pines J, Deb P, Powers C, Shrank W. Increased observation services in Medicare beneficiaries with chest pain. Am J Emergency Med. 2016;34(1):16-19. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2015.08.049. PubMed

19. Nuckols T, Fingar K, Barrett M, Steiner C, Stocks C, Owens P. The shifting landscape in utilization of inpatient, observation, and emergency department services across payors. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(6):443-446. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2751. PubMed

20. Wright B, Jung H-Y, Feng Z, Mor V. Trends in observation care among Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries at critical access hospitals, 2007-2009. J Rural Health. 2013;29(1):s1-s6. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12007 PubMed

21. Office of Inspector General. Vulnerabilites remain under Medicare’s 2-Midnight hospital policy. 12-9-2016. https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-02-15-00020.asp. Accessed December 27, 2017. PubMed

22. Research Data Assistance Center (ResDAC). Revenue center table. https://www.resdac.org/sites/resdac.umn.edu/files/Revenue%20Center%20Table.txt. Accessed December 26, 2017.

23. Medicare Claims Processing Manual, Chapter 4, Section 290, Outpatient Observation Services. https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads/clm104c04.pdf. Accessed December 26, 2017.

24. Research Data Assistance Center (ResDAC). Identifying observation stays for those beneficiaries admitted to the hospital. https://www.resdac.org/resconnect/articles/172. Accessed December 27, 2017.

25. Medicare Claims Processing Manual, Chapter 3, Section 40.B. Outpatient services treated as inpatient services. https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/Downloads/clm104c03.pdf. Accessed December 26, 2017.

26. Reynolds J. Another look at roles and functions: has hospital case management lost its way? Prof Case Manag. 2013;18(5):246-254. doi: 10.1097/NCM.0b013e31829c8aa8. PubMed

27. Sheehy A, Locke C, Engel J, et al. Recovery audit contractor audit and appeals at three academic medical centers. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(4):212-219. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2332. PubMed

1. MedPAC Report to Congress. June 2015, Chapter 7. Hospital short-stay policy issues. http://medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/june-2015-report-to-the-congress-medicare-and-the-health-care-delivery-system.pdf?sfvrsn=0. Accessed December 21, 2017.

2. MedPAC Report to Congress. March 2017, Chapter 3. Hospital inpatient and outpatient services. http://medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/mar17_entirereport224610adfa9c665e80adff00009edf9c.pdf?sfvrsn=0. Accessed December 21, 2017.

3. Kind A, Jencks S, Crock J, et al. Neighborhood socioecomonic disadvantage and 30-day reshospitalization: a retrospective cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(11):765-774. doi: 10.7326/M13-2946. PubMed

4. Zuckerman R, Sheingold S, Orav E, Ruhter J, Epstein A. Readmissions, observation, and the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program. NEJM. 2016;374(16):1543-1551. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1513024. PubMed

5. Hockenberry J, Mutter R, Barrett M, Parlato J, Ross M. Factors associated with prolonged observation services stays and the impact of long stays on patient cost. Health Serv Res. 2014;49(3):893-909. 10.1111/1475-6773.12143. PubMed

6. Goldstein J, Zhang Z, Schwartz S, Hicks L. Observation status, poverty, and high financial liability among Medicare beneficiaries. Am J Med. 2017;131(1):e9-101.e15. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.07.013. PubMed

7. Feng Z, Wright B, Mor V. Sharp rise in Medicare enrollees being held in hospitals for observation raises concerns about causes and consequences. Health Aff. 2012;31(6):1251-1259. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0129. PubMed

8. Feng Z, Jung H-Y, Wright B, Mor V. The origin and disposition of Medicare observation stays. Med Care. 2014;52(9):796-800. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000179 PubMed

9. Wright B, Jung H-Y, Feng Z, Mor V. Hospital, patient, and local health system characteristics associated with the prevalence and duration of observation care. HSR. 2014;49(4):1088-1107. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12166. PubMed

10. Overman R, Freburger J, Assimon M, Li X, Brookhart MA. Observation stays in administrative claims databases: underestimation of hospitalized cases. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2014;23(9):902-910. doi: 10.1002/pds.3647. PubMed

11. Vashi A, Cafardi S, Powers C, Ross J, Shrank W. Observation encounters and subsequent nursing facility stays. Am J Manag Care. 2015;21(4):e276-e281. PubMed

12. Venkatesh A, Wang C, Ross J, et al. Hospital use of observation stays: cross-sectional study of the impact on readmission rates. Med Care. 2016;54(12):1070-1077. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000601 PubMed

13. Gerhardt G, Yemane A, Apostle K, Oelschlaeger A, Rollins E, Brennan N. Evaluating whether changes in utilization of hospital outpatient services contributed to lower Medicare readmission rate. MMRR. 2014;4(1):E1-E13. doi: 10.5600/mmrr2014-004-01-b03 PubMed

14. Lipitz-Snyderman A, Klotz A, Gennarelli R, Groeger J. A population-based assessment of emergency department observation status for older adults with cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2017;15(10):1234-1239. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2017.0160. PubMed

15. Kangovi S, Cafardi S, Smith R, Kulkarni R, Grande D. Patient financial responsibility for observation care. J Hosp Med. 2015;10:718-723. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2436. PubMed

16. Dharmarajan K, Qin L, Bierlein M, et al. Outcomes after observation stays among older adult Medicare beneficiaries in the USA: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2017;357:j2616. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j2616 PubMed

17. Baier R, Gardner R, Coleman E, Jencks S, Mor V, Gravenstein S. Shifting the dialogue from hospital readmissions to unplanned care. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(6):450-453. PubMed

18. Cafardi S, Pines J, Deb P, Powers C, Shrank W. Increased observation services in Medicare beneficiaries with chest pain. Am J Emergency Med. 2016;34(1):16-19. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2015.08.049. PubMed

19. Nuckols T, Fingar K, Barrett M, Steiner C, Stocks C, Owens P. The shifting landscape in utilization of inpatient, observation, and emergency department services across payors. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(6):443-446. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2751. PubMed

20. Wright B, Jung H-Y, Feng Z, Mor V. Trends in observation care among Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries at critical access hospitals, 2007-2009. J Rural Health. 2013;29(1):s1-s6. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12007 PubMed

21. Office of Inspector General. Vulnerabilites remain under Medicare’s 2-Midnight hospital policy. 12-9-2016. https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-02-15-00020.asp. Accessed December 27, 2017. PubMed

22. Research Data Assistance Center (ResDAC). Revenue center table. https://www.resdac.org/sites/resdac.umn.edu/files/Revenue%20Center%20Table.txt. Accessed December 26, 2017.

23. Medicare Claims Processing Manual, Chapter 4, Section 290, Outpatient Observation Services. https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads/clm104c04.pdf. Accessed December 26, 2017.

24. Research Data Assistance Center (ResDAC). Identifying observation stays for those beneficiaries admitted to the hospital. https://www.resdac.org/resconnect/articles/172. Accessed December 27, 2017.

25. Medicare Claims Processing Manual, Chapter 3, Section 40.B. Outpatient services treated as inpatient services. https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/Downloads/clm104c03.pdf. Accessed December 26, 2017.

26. Reynolds J. Another look at roles and functions: has hospital case management lost its way? Prof Case Manag. 2013;18(5):246-254. doi: 10.1097/NCM.0b013e31829c8aa8. PubMed

27. Sheehy A, Locke C, Engel J, et al. Recovery audit contractor audit and appeals at three academic medical centers. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(4):212-219. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2332. PubMed

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine

In Reference to “The Weekend Effect in Hospitalized Patients: A Meta-Analysis”

The prevalent reason offered for increased mortality rates during weekend hours are shortages in staffing and services. The “weekend effect,” elucidated by Pauls et al.1 in their recent meta-analysis, and the accompanying editorial by Quinn and Bell,2 highlight these and other potential causes for this anomaly.

Pauls et al.1 also cite patient selection bias as a possible explanation for the uptick in deaths during this span (off-hour admissions may be sicker). It is due to the latter that we wish to highlight additional studies published after mid-2013 when the authors concluded their search.

Recent disputes within the UK’s National Health Service3 concerning health system funding spurred timely papers in BMJ4 and Lancet5 on the uncertainty. They both discovered a stronger signal from patient characteristics admitted during this time rather than on-hand resources and workforce. These new investigations strengthen the support for patient acuity as a determinant in explaining worse outcomes.

We highlight these manuscripts so investigators will continue their attempts to understand the weekend phenomena as suggested by both Pauls et al.1 and the editorialists.2 To allow for the delivery of correct interventions, we must understand its root causes. In this case, it may be the unique features of patients presenting on Saturdays and Sundays and, hence, would require a different set of process changes.

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

1. Pauls L, Johnson-Paben R, McGready J, Murphy J, Pronovost P, Wu C. The weekend effect in hospitalized patients: A meta-analysis. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(9):760-766. PubMed

2. Quinn K, Bell C. Does the week-end justify the means? J Hosp Med. 2017;12(9):779-780. PubMed

3. Weaver M. Junior Doctors: Jeremy Hunt says five-day strike will be ‘worst in NHS history.’ The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2016/sep/01/jeremy-hunt-five-day-doctors-strike-worst-in-nhs-history. Accessed September 20, 2017.

4. Freemantle N, Ray D, McNulty D, et al. Increased mortality associated with weekend hospital admission: a case for expanded seven day services? BMJ. 2015;351:h4596. doi:10.1136/bmj.h4598. PubMed

5. Walker S, Mason A, Phuong Quan T, et al. Mortality risks associated with emergency admissions during weekends and public holidays: an analysis of electronic health records. The Lancet. 2017;390(10089):62-72. PubMed

The prevalent reason offered for increased mortality rates during weekend hours are shortages in staffing and services. The “weekend effect,” elucidated by Pauls et al.1 in their recent meta-analysis, and the accompanying editorial by Quinn and Bell,2 highlight these and other potential causes for this anomaly.

Pauls et al.1 also cite patient selection bias as a possible explanation for the uptick in deaths during this span (off-hour admissions may be sicker). It is due to the latter that we wish to highlight additional studies published after mid-2013 when the authors concluded their search.

Recent disputes within the UK’s National Health Service3 concerning health system funding spurred timely papers in BMJ4 and Lancet5 on the uncertainty. They both discovered a stronger signal from patient characteristics admitted during this time rather than on-hand resources and workforce. These new investigations strengthen the support for patient acuity as a determinant in explaining worse outcomes.

We highlight these manuscripts so investigators will continue their attempts to understand the weekend phenomena as suggested by both Pauls et al.1 and the editorialists.2 To allow for the delivery of correct interventions, we must understand its root causes. In this case, it may be the unique features of patients presenting on Saturdays and Sundays and, hence, would require a different set of process changes.

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

The prevalent reason offered for increased mortality rates during weekend hours are shortages in staffing and services. The “weekend effect,” elucidated by Pauls et al.1 in their recent meta-analysis, and the accompanying editorial by Quinn and Bell,2 highlight these and other potential causes for this anomaly.

Pauls et al.1 also cite patient selection bias as a possible explanation for the uptick in deaths during this span (off-hour admissions may be sicker). It is due to the latter that we wish to highlight additional studies published after mid-2013 when the authors concluded their search.

Recent disputes within the UK’s National Health Service3 concerning health system funding spurred timely papers in BMJ4 and Lancet5 on the uncertainty. They both discovered a stronger signal from patient characteristics admitted during this time rather than on-hand resources and workforce. These new investigations strengthen the support for patient acuity as a determinant in explaining worse outcomes.

We highlight these manuscripts so investigators will continue their attempts to understand the weekend phenomena as suggested by both Pauls et al.1 and the editorialists.2 To allow for the delivery of correct interventions, we must understand its root causes. In this case, it may be the unique features of patients presenting on Saturdays and Sundays and, hence, would require a different set of process changes.

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

1. Pauls L, Johnson-Paben R, McGready J, Murphy J, Pronovost P, Wu C. The weekend effect in hospitalized patients: A meta-analysis. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(9):760-766. PubMed

2. Quinn K, Bell C. Does the week-end justify the means? J Hosp Med. 2017;12(9):779-780. PubMed

3. Weaver M. Junior Doctors: Jeremy Hunt says five-day strike will be ‘worst in NHS history.’ The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2016/sep/01/jeremy-hunt-five-day-doctors-strike-worst-in-nhs-history. Accessed September 20, 2017.

4. Freemantle N, Ray D, McNulty D, et al. Increased mortality associated with weekend hospital admission: a case for expanded seven day services? BMJ. 2015;351:h4596. doi:10.1136/bmj.h4598. PubMed

5. Walker S, Mason A, Phuong Quan T, et al. Mortality risks associated with emergency admissions during weekends and public holidays: an analysis of electronic health records. The Lancet. 2017;390(10089):62-72. PubMed

1. Pauls L, Johnson-Paben R, McGready J, Murphy J, Pronovost P, Wu C. The weekend effect in hospitalized patients: A meta-analysis. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(9):760-766. PubMed

2. Quinn K, Bell C. Does the week-end justify the means? J Hosp Med. 2017;12(9):779-780. PubMed

3. Weaver M. Junior Doctors: Jeremy Hunt says five-day strike will be ‘worst in NHS history.’ The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2016/sep/01/jeremy-hunt-five-day-doctors-strike-worst-in-nhs-history. Accessed September 20, 2017.

4. Freemantle N, Ray D, McNulty D, et al. Increased mortality associated with weekend hospital admission: a case for expanded seven day services? BMJ. 2015;351:h4596. doi:10.1136/bmj.h4598. PubMed

5. Walker S, Mason A, Phuong Quan T, et al. Mortality risks associated with emergency admissions during weekends and public holidays: an analysis of electronic health records. The Lancet. 2017;390(10089):62-72. PubMed

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

Hospitalizations with observation services and the Medicare Part A complex appeals process at three academic medical centers

Hospitalists and other inpatient providers are familiar with hospitalizations classified observation. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) uses the “2-midnight rule” to distinguish between outpatient services (which include all observation stays) and inpatient services for most hospitalizations. The rule states that “inpatient admissions will generally be payable … if the admitting practitioner expected the patient to require a hospital stay that crossed two midnights and the medical record supports that reasonable expectation.”1

Hospitalization under inpatient versus outpatient status is a billing distinction that can have significant financial consequences for patients, providers, and hospitals. The inpatient or outpatient observation orders written by hospitalists and other hospital-based providers direct billing based on CMS and other third-party regulation. However, providers may have variable expertise writing such orders. To audit the correct use of the visit-status orders by hospital providers, CMS uses recovery auditors (RAs), also referred to as recovery audit contractors.2,3

Historically, RAs had up to 3 years from date of service (DOS) to perform an audit, which involves asking a hospital for a medical record for a particular stay. The audit timeline includes 45 days for hospitals to produce such documentation, and 60 days for the RA either to agree with the hospital’s billing or to make an “overpayment determination” that the hospital should have billed Medicare Part B (outpatient) instead of Part A (inpatient).3,4 The hospital may either accept the RA decision, or contest it by using the pre-appeals discussion period or by directly entering the 5-level Medicare administrative appeals process.3,4 Level 1 and Level 2 appeals are heard by a government contractor, Level 3 by an administrative law judge (ALJ), Level 4 by a Medicare appeals council, and Level 5 by a federal district court. These different appeal types have different deadlines (Appendix 1). The deadlines for hospitals and government responses beyond Level 1 are set by Congress and enforced by CMS,3,4 and CMS sets discussion period timelines. Hospitals that miss an appeals deadline automatically default their appeals request, but there are no penalties for missed government deadlines.

Recently, there has been increased scrutiny of the audit-and-appeals process of outpatient and inpatient status determinations.5 Despite the 2-midnight rule, the Medicare Benefit Policy Manual (MBPM) retains the passage: “Physicians should use a 24-hour period as a benchmark, i.e., they should order admission for patients who are expected to need hospital care for 24 hours or more, and treat other patients on an outpatient basis.”6 Auditors often cite “medical necessity” in their decisions, which is not well defined in the MBPM and can be open to different interpretation. This lack of clarity likely contributed to the large number of status determination discrepancies between providers and RAs, thereby creating a federal appeals backlog that caused the Office of Medicare Hearings and Appeals to halt hospital appeals assignments7 and prompted an ongoing lawsuit against CMS regarding the lengthy appeals process.4 To address these problems and clear the appeals backlog, CMS proposed a “$0.68 settlement offer.”4 The settlement “offered an administrative agreement to any hospital willing to withdraw their pending appeals in exchange for timely partial payment (68% of the net allowable amount)”8 and paid out almost $1.5 billion to the third of eligible hospitals that accepted the offer.9 CMS also made programmatic improvements to the RA program.10

Despite these efforts, problems remain. On June 9, 2016, the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) published Medicare Fee-for-Service: Opportunities Remain to Improve Appeals Process, citing an approximate 2000% increase in hospital inpatient appeals during the period 2010–2014 and the concern that appeals requests will continue to exceed adjudication capabilities.11 On July 5, 2016, CMS issued its proposed rule for appeals reform that allows the Medicare Appeals Council (Level 4) to set precedents which would be binding at lower levels and allows senior attorneys to handle some cases and effectively increase manpower at the Level 3 (ALJ). In addition, CMS proposes to revise the method for calculating dollars at risk needed to schedule an ALJ hearing, and develop methods to better adjudicate similar claims, and other process improvements aimed at decreasing the more than 750,000 current claims awaiting ALJ decisions.12

We conducted a study to better understand the Medicare appeals process in the context of the proposed CMS reforms by investigating all appeals reaching Level 3 at Johns Hopkins Hospital (JHH), University of Wisconsin Hospitals and Clinics (UWHC), and University of Utah Hospital (UU). Because relatively few cases nationally are appealed beyond Level 3, the study focused on most-relevant data.3 We examined time spent at each appeal Level and whether it met federally mandated deadlines, as well as the percentage accountable to hospitals versus government contractors or ALJs. We also recorded the overturn rate at Level 3 and evaluated standardized text in de-identified decision letters to determine criteria cited by contractors in their decisions to deny hospital appeal requests.

METHODS

The JHH, UWHC, and UU Institutional Review Boards did not require a review. The study included all complex Part A appeals involving DOS before October 1, 2013 and reaching Level 3 (ALJ) as of May 1, 2016.

Our general methods were described previously.2 Briefly, the 3 academic medical centers are geographically diverse. JHH is in region A, UWHC in region B, and UU in region D (3 of the 4 RA regions are represented). The hospitals had different Medicare administrative contractors but the same qualified independent contractor until March 1, 2015 (Appendix 2).

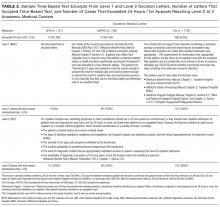

For this paper, time spent in the discussion period, if applicable, is included in appeals time, except as specified (Table 1). The term partially favorable is used for UU cases only, based on the O’Connor Hospital decision13 (Table 1). Reflecting ambiguity in the MBPM, for time-based encounter length of stay (LOS) statements, JHH and UU used time between admission order and discharge order, whereas UWHC used time between decision to admit (for emergency department patients) or time care began (direct admissions) and time patient stopped receiving care (Table 2). Although CMS now defines when a hospital encounter begins under the 2-midnight rule,14 there was no standard definition when the cases in this study were audited.

We reviewed de-identified standardized text in Level 1 and Level 2 decision letters. Each hospital designated an analyst to search letters for Medicare Benefit Policy Manual chapter 1, which references the 24-hour benchmark, or the MBPM statement regarding use of the 24-hour period as a benchmark to guide inpatient admission orders.6 Associated paragraphs that included these terms were coded and reviewed by Drs. Sheehy, Engel, and Locke to confirm that the 24-hour time-based benchmark was mentioned, as per the MBPM statement (Table 2, Appendix 3).

Descriptive statistics are used to describe the data, and representative de-identified standardized text is included.

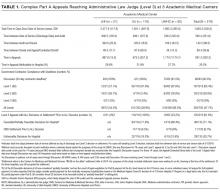

RESULTS

Of 219 Level 3 cases, 135 (61.6%) concluded at Level 3. Of these 135 cases, 96 (71.1%) were decided in favor of the hospital, 11 (8.1%) were settled in the CMS $0.68 settlement offer, and 28 (20.7%) were unfavorable to the hospital (Table 1).

Mean total days since DOS was 1,663.3 (536.8) (mean [SD]), with median 1708 days. This included 560.4 (351.6) days between DOS and audit (median 556 days) and 891.3 (320.3) days in appeal (median 979 days). The hospitals were responsible for 29.3% of that time (260.7 [68.2] days) while government contractors were responsible for 70.7% (630.6 [277.2] days). Government contractors and ALJs met deadlines 47.7% of the time, meeting appeals deadlines 92.5% of the time for Discussion, 85.4% for Level 1, 38.8% for Level 2, and 0% for Level 3 (Table 1).

All “redetermination” (level 1 appeals letters) received at UU and UWHC, and all “reconsideration” (level 2 appeals letters) received by UU, UWHC, and JHH contained standardized time-based 24–hour benchmark text directly or referencing the MBPM containing such text, to describe criteria for inpatient status (Table 2 and Appendix 3).6 In total, 417 of 438 (95.2%) of Level 1 and Level 2 appeals results letters contained time-based 24-hour benchmark criteria for inpatient status despite 154 of 219 (70.3%) of denied cases exceeding a 24-hour LOS.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated process and timeliness concerns in the Medicare RA program for Level 3 cases at 3 academic medical centers. Although hospitals forfeit any appeal for which they miss a filing deadline, government contractors and ALJs met their deadlines less than half the time without default or penalty. Average time from the rendering of services to the conclusion of the audit-and-appeals process exceeded 4.5 years, which included an average 560 days between hospital stay and initial RA audit, and almost 900 days in appeals, with more than 70% of that time attributable to government contractors and ALJs.

Objective time-based 24-hour inpatient status criteria were referenced in 95% of decision letters, even though LOS exceeded 24 hours in more than 70% of these cases, suggesting that objective LOS data played only a small role in contractor decisions, or that contractors did not actually audit for LOS when reviewing cases. Unclear criteria likely contributed to payment denials and improper payments, despite admitting providers’ best efforts to comply with Medicare rules when writing visit-status orders. There was also a significant cost to hospitals; our prior study found that navigating the appeals process required 5 full-time equivalents per institution.2

At the 2 study hospitals with Level 3 decisions, more than two thirds of the decisions favored the hospital, suggesting the hospitals were justified in appealing RA Level 1 and Level 2 determinations. This proportion is consistent with the 43% ALJ overturn rate (including RA- and non-RA-derived appeals) cited in the recent U.S. Court of Appeals for the DC Circuit decision.9

This study potentially was limited by contractor and hospital use of the nonstandardized LOS calculation during the study period. That the majority of JHH and UU cases cited the 24-hour benchmark in their letters but nevertheless exceeded 24-hour LOS (using the most conservative definition of LOS) suggests contractors did not audit for or consider LOS in their decisions.

Our results support recent steps taken by CMS to reform the appeals process, including shortening the RA “look-back period” from 3 years to 6 months,10 which will markedly shorten the 560-day lag between DOS and audit found in this study. In addition, CMS has replaced RAs with beneficiary and family-centered care quality improvement organizations (BFCC-QIOs)1,8 for initial status determination audits. Although it is too soon to tell, the hope is that BFCC-QIOs will decrease the volume of audits and denials that have overwhelmed the system and most probably contributed to process delays and the appeals backlog.

However, our data demonstrate several areas of concern not addressed in the recent GAO report11 or in the rule proposed by CMS.12 Most important, CMS could consider an appeals deadline missed by a government contractor as a decision for the hospital, in the same way a hospital’s missed deadline defaults its appeal. Such equity would ensure due process and prevent another appeals backlog. In addition, the large number of Level 3 decisions favoring hospitals suggests a need for process improvement at the Medicare administrative contractor and qualified independent contractor Level of appeals—such as mandatory review of Level 1 and Level 2 decision letters for appeals overturned at Level 3, accountability for Level 1 and Level 2 contractors with high rates of Level 3 overturn, and clarification of criteria used to judge determinations.

Medicare fraud cannot be tolerated, and a robust auditing process is essential to the integrity of the Medicare program. CMS’s current and proposed reforms may not be enough to eliminate the appeals backlog and restore a timely and fair appeals process. As CMS explores bundled payments and other reimbursement reforms, perhaps the need to distinguish observation hospital care will be eliminated. Short of that, additional actions must be taken so that a just and efficient Medicare appeals system can be realized for observation hospitalizations.

Acknowledgments

For invaluable assistance in data preparation and presentation, the authors thank Becky Borchert, RN, MS, MBA, Program Manager for Medicare/Medicaid Utilization Review, University of Wisconsin Hospital and Clinics; Carol Duhaney, Calvin Young, and Joan Kratz, RN, Johns Hopkins Hospital; and Morgan Walker and Lisa Whittaker, RN, University of Utah.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

1. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, US Dept of Health and Human Services. Fact sheet: 2-midnight rule. https://www.cms.gov/Newsroom/MediaReleaseDatabase/Fact-sheets/2015-Fact-sheets-items/2015-07-01-2.html. Published July 1, 2015. Accessed August 9, 2016.

2. Sheehy AM, Locke C, Engel JZ, et al. Recovery Audit Contractor audits and appeals at three academic medical centers. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(4):212-219. PubMed

3. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, US Dept of Health and Human Services. Recovery auditing in Medicare for fiscal year 2014. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Monitoring-Programs/Medicare-FFS-Compliance-Programs/Recovery-Audit-Program/Downloads/RAC-RTC-FY2014.pdf. Accessed August 9, 2016.

4. American Hospital Association vs Burwell. No 15-5015. Circuit court decision. https://www.cadc.uscourts.gov/internet/opinions.nsf/CDFE9734F0D36C2185257F540052A39D/$file/15-5015-1597907.pdf. Decided February 9, 2016. Accessed August 9, 2016

5. AMA news: Payment recovery audit program needs overhaul: Doctors to CMS. https://wire.ama-assn.org/ama-news/payment-recovery-audit-program-needs-overhaul-doctors-cms. Accessed March 17, 2017.

6. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, US Dept of Health and Human Services. Inpatient hospital services covered under Part A. In: Medicare Benefit Policy Manual. Chapter 1. Publication 100-02. https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads/bp102c01.pdf. Accessed August 9, 2016.

7. Griswold NJ; Office of Medicare Hearings and Appeals, US Dept of Health and Human Services. Memorandum to OMHA Medicare appellants. http://www.modernhealthcare.com/assets/pdf/CH92573110.pdf. Accessed August 9, 2016.

8. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, US Dept of Health and Human Services. Inpatient hospital reviews. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Monitoring-Programs/Medicare-FFS-Compliance-Programs/Medical-Review/InpatientHospitalReviews.html. Accessed August 9, 2016.

9. Galewitz P. CMS identifies hospitals paid nearly $1.5B in 2015 Medicare billing settlement. Kaiser Health News. http://khn.org/news/cms-identifies-hospitals-paid-nearly-1-5b-in-2015-medicare-billing-settlement/. Published August 23, 2016. Accessed October 14, 2016.

10. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, US Dept of Health and Human Services. Recovery audit program improvements. https://www.cms.gov/research-statistics-data-and-systems/monitoring-programs/medicare-ffs-compliance-programs/recovery-audit-program/downloads/RAC-program-improvements.pdf. Accessed August 9, 2016.

11. US Government Accountability Office. Medicare Fee-for-Service: Opportunities Remain to Improve Appeals Process. http://www.gao.gov/assets/680/677034.pdf. Publication GAO-16-366. Published May 10, 2016. Accessed August 9, 2016.

12. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, US Dept of Health and Human Services. Changes to the Medicare Claims and Entitlement, Medicare Advantage Organization Determination, and Medicare Prescription Drug Coverage Determination Appeals Procedures. https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2016-07-05/pdf/2016-15192.pdf. Accessed August 9, 2016.

13. Departmental Appeals Board, US Dept of Health and Human Services. Action and Order of Medicare Appeals Council: in the case of O’Connor Hospital. http://www.hhs.gov/dab/divisions/medicareoperations/macdecisions/oconnorhospital.pdf. Accessed August 9, 2016.

14. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, US Dept of Health and Human Services. Frequently asked questions: 2 midnight inpatient admission guidance & patient status reviews for admissions on or after October 1, 2013. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Monitoring-Programs/Medical-Review/Downloads/QAsforWebsitePosting_110413-v2-CLEAN.pdf. Accessed August 9, 2016.

Hospitalists and other inpatient providers are familiar with hospitalizations classified observation. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) uses the “2-midnight rule” to distinguish between outpatient services (which include all observation stays) and inpatient services for most hospitalizations. The rule states that “inpatient admissions will generally be payable … if the admitting practitioner expected the patient to require a hospital stay that crossed two midnights and the medical record supports that reasonable expectation.”1

Hospitalization under inpatient versus outpatient status is a billing distinction that can have significant financial consequences for patients, providers, and hospitals. The inpatient or outpatient observation orders written by hospitalists and other hospital-based providers direct billing based on CMS and other third-party regulation. However, providers may have variable expertise writing such orders. To audit the correct use of the visit-status orders by hospital providers, CMS uses recovery auditors (RAs), also referred to as recovery audit contractors.2,3

Historically, RAs had up to 3 years from date of service (DOS) to perform an audit, which involves asking a hospital for a medical record for a particular stay. The audit timeline includes 45 days for hospitals to produce such documentation, and 60 days for the RA either to agree with the hospital’s billing or to make an “overpayment determination” that the hospital should have billed Medicare Part B (outpatient) instead of Part A (inpatient).3,4 The hospital may either accept the RA decision, or contest it by using the pre-appeals discussion period or by directly entering the 5-level Medicare administrative appeals process.3,4 Level 1 and Level 2 appeals are heard by a government contractor, Level 3 by an administrative law judge (ALJ), Level 4 by a Medicare appeals council, and Level 5 by a federal district court. These different appeal types have different deadlines (Appendix 1). The deadlines for hospitals and government responses beyond Level 1 are set by Congress and enforced by CMS,3,4 and CMS sets discussion period timelines. Hospitals that miss an appeals deadline automatically default their appeals request, but there are no penalties for missed government deadlines.