User login

Online Patient-Reported Reviews of Mohs Micrographic Surgery: Qualitative Analysis of Positive and Negative Experiences

Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) remains the gold standard for the removal of skin cancers in high-risk areas of the body while offering an excellent safety profile and sparing tissue.1 In the current health care environment, online patient reviews have grown in popularity and influence. More than 60% of consumers consult social media before making health care decisions.2 A recent analysis of online patient reviews of general dermatology practices demonstrated the perceived importance of physician empathy, thoroughness, and cognizance of cost in relation to patient-reported satisfaction.3 Because MMS is a well-recognized and unique outpatient-based surgical procedure, a review and analysis of online patient reviews specific to MMS can provide useful practice insights.

Materials and Methods

This study was conducted using an online platform (RealSelf [http://www.realself.com]) that connects patients and providers offering aesthetically oriented procedures; the site has 35 million unique visitors yearly.4 The community’s directory was used to identify and analyze all cumulative patient reviews from 2006 to December 20, 2015, using the search terms Mohs surgery or Mohs micrographic surgery. The study was exempt by the Northwestern University (Chicago, Illinois) institutional review board.

A standardized qualitative coding methodology was created and applied to all available comments regarding MMS. A broad list of positive and negative patient experiences was first created and agreed upon by all 3 investigators. Each individual comment was then attributed to 1 or more of these positive or negative themes. Of these comments, 10% were coded by 2 investigators (S.X. and Z.A.) to ensure internal validity; 1 investigator coded the remaining statements by patients (Z.A.). Patient-reported satisfaction ratings categorized as “worth it” or “not worth it” (as used by RealSelf to describe the patient-perceived value and utility of a given procedure) as well as cost of MMS were gathered. Cumulative patient ratings were collected for the procedure overall, physician’s bedside manner, answered questions, aftercare follow-up, time spent with patients, telephone/email responsiveness, staff professionalism/courtesy, payment process, and wait times. Patient-reported characteristics of MMS also were evaluated including physician specialty, lesion location, type of skin cancer, and type of closure. For lesion location, we graded whether the location represented a high-risk area as defined by the American Academy of Dermatology, American College of Mohs Surgery, and American Society for Dermatologic Surgery.5

Results

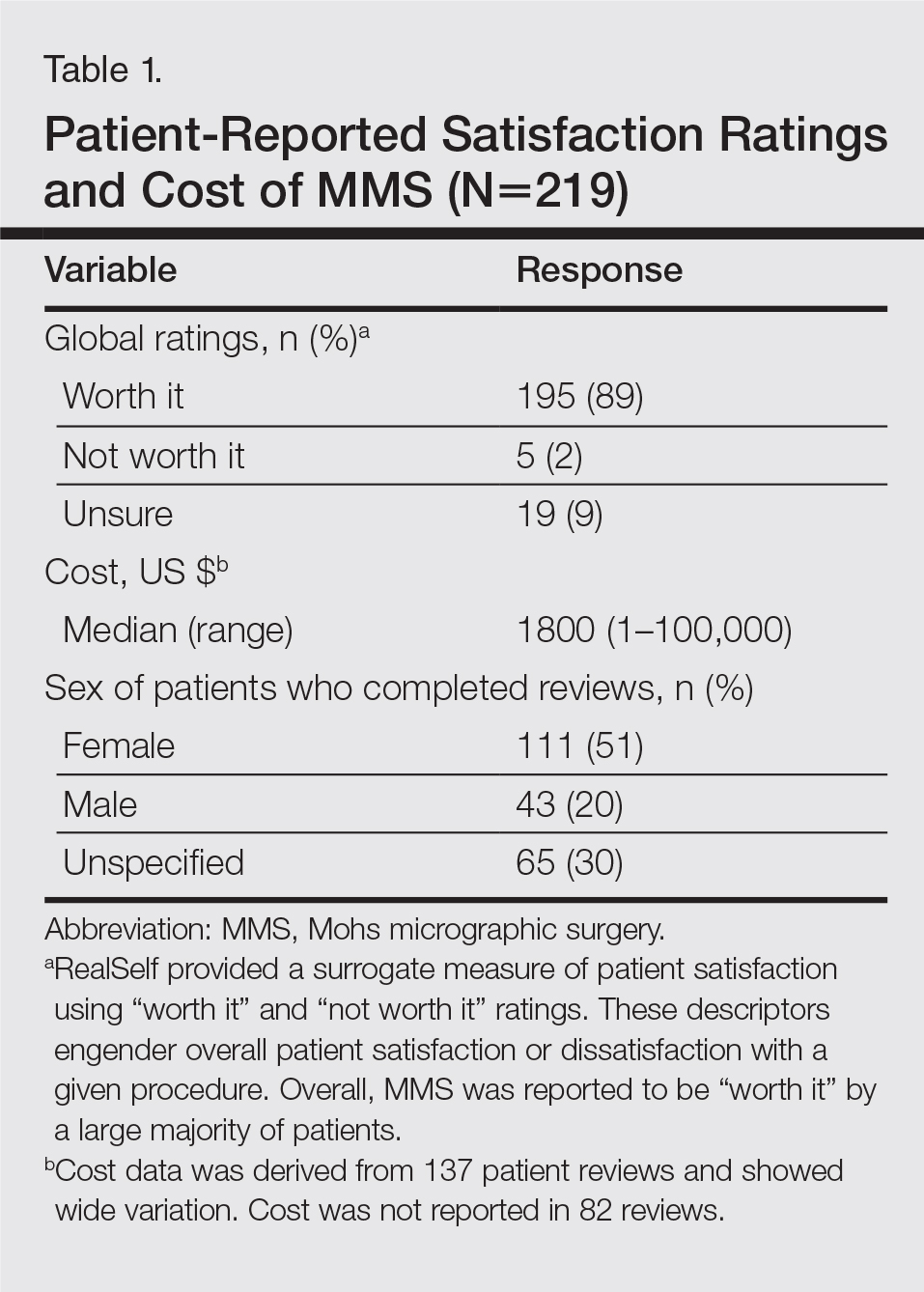

A total of 219 reviews related to MMS were collected as of December 20, 2015. Overall, MMS was considered “worth it” by 89% of patients (Table 1). Only 2% of patients described MMS as “not worth it.” There was a wide range reported for the cost of the procedure ($1–$100,000 [median, $1800]). Of those patients who reported their sex, females were 2.5-times more likely to post a review compared to males (51% vs 20%); however, 30% of reviewers did not report their sex. The mean (standard deviation) overall satisfaction rating was 4.8 (0.8). With regard to category-specific ratings (eg, bedside manner, aftercare follow-up, time spent with patients), the mean scores were all 4.7 or greater (Table 2).

Regarding the surgical aspects of the procedure, the majority of patients reported that the excision of the lesion was performed by a dermatologist (62%). However, a notable portion of patients reported that the excision was performed by a plastic surgeon (21%). Physician specialty was not reported in 16% of the reviews. For the lesion closure, the patient-reported specialty of the physician was only slightly higher for dermatologists versus plastic surgeons (46% vs 44%)(Table 3).

The majority of patients who reported the location of the lesion treated with MMS identified a high-risk location (45%), a medium-risk location (18%), or an unspecified region of the face (15%), according to the appropriate-use criteria for MMS (Table 3).5 Patients did not specify the site of surgery 17% of the time. Only 5% of reported procedures were performed on low-risk areas.

Basal cell carcinomas were the most commonly reported lesions removed by MMS (38%), though 48% of reviews did not specify the type of tumor being treated (Table 3). A large majority (76%) did not specify the type of closure performed. When specified, secondary intention was used 10% of the time, followed by either a flap (6%) or skin graft (6%). Only 5% of patients reported an estimated size of the primary lesion in our study (data not shown).

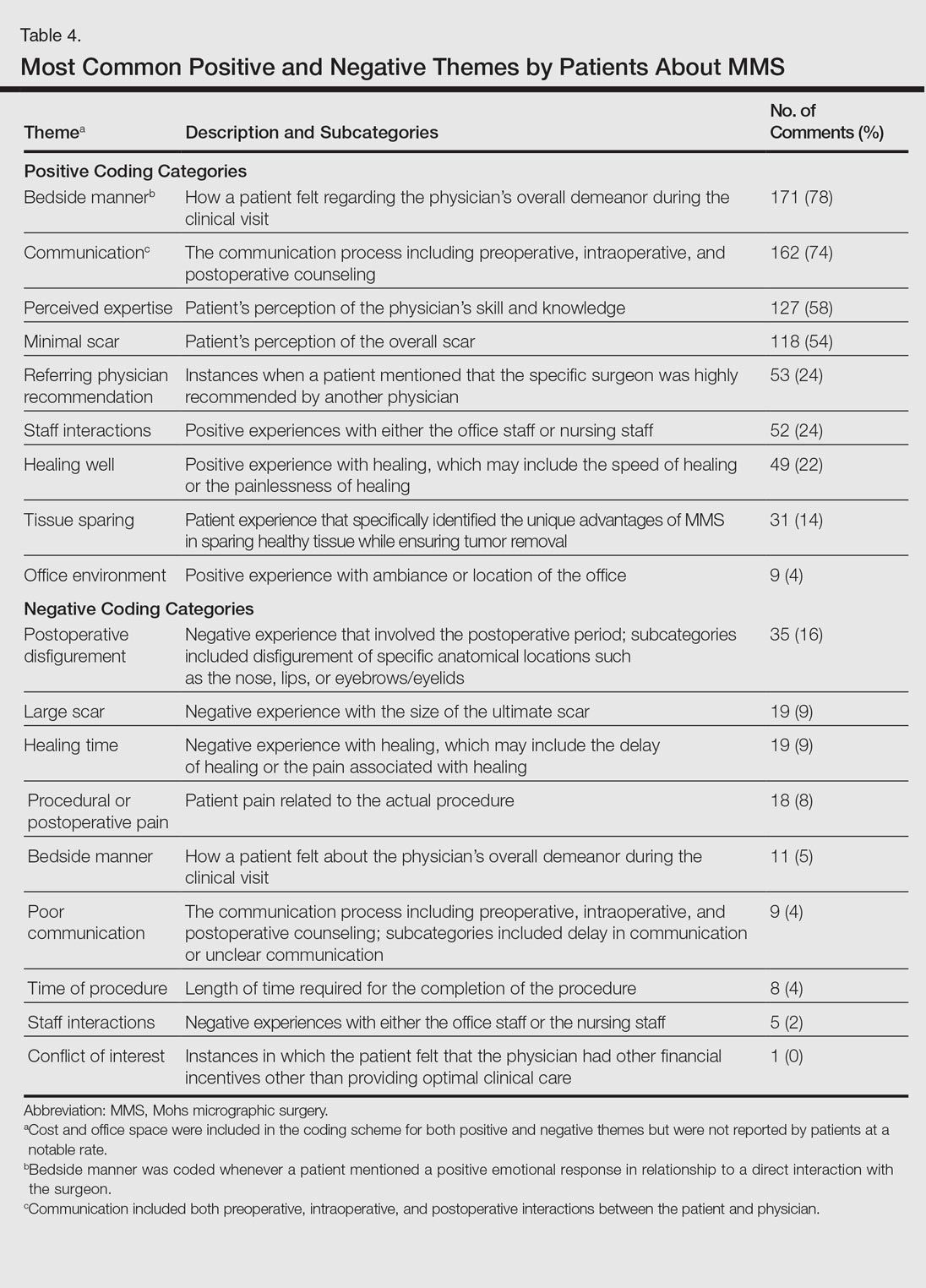

The qualitative analysis demonstrated variance in themes for positive and negative characteristics (Table 4). Surgeon characteristics encompassed the 3 most commonly cited themes of positive remarks, including bedside manner (78%), communication skills (74%), and perceived expertise (58%). Specific to MMS, the tissue-sparing nature of the technique was cited by 14% of reviews as a positive theme. The most commonly cited themes of negative remarks were intraoperative and postoperative concerns, including postoperative disfigurement (16%), large scar (9%), healing time (9%), and procedural or postoperative pain (8%). A subtheme analysis of postoperative disfigurement revealed that eyelid or eyebrow distortion was the most common concern (29%), followed by redness and swelling (23%), an open wound (14%), and nostril/nose distortion (14%)(data not shown). Themes not commonly cited as either positive or negative included office environment, cost, and procedure time (data not shown).

Comment

The overall satisfaction with MMS (89%) was one of the highest for any procedure on this online patient review site, albeit based on fewer reviews compared to other common aesthetic surgical procedures. In comparison, 78% of 13,500 reviewers rated breast augmentation as “worth it,” while 60% of 6800 reviewers rated rhinoplasty as “worth it” (as of December 2015). Overall, the online patient reviews evaluated in this study were consistent with a previously published structured data report on patient satisfaction with MMS.6

The results show a greater than expected proportion of both the MMS excision and closure being performed by plastic surgeons compared to dermatologists. In reality, the majority of MMS excisions are performed by dermatologists. Based on a survey of American College of Mohs Surgery (ACMS) members, only 6% of procedures were sent to other specialties for closure.7 Our results may reflect reporting bias or patients misconstruing true MMS with an excision and standard frozen sections, techniques that have lower cure rates. If so, there may be a need to educate patients regarding the specifics of MMS. Other possible explanations for the discrepancy between the online patient reviews and ACMS data include misinterpretation by patients on the exact definition of MMS or that a higher than expected number of procedures were performed by non-ACMS Mohs surgeons.

Our qualitative analysis revealed that patients most frequently commented on the interpersonal skills of their surgeons (eg, bedside manner, communication) as positive themes during MMS, similar to prior analyses of general dermatology practices.3 In comparison to a recent study assessing patient satisfaction with rhinoplasty on RealSelf, the final appearance of the nose represented the most common positive- and negative-cited theme.8 Mohs micrographic surgery procedures typically are done under local anesthesia, which may explain the greater importance of bedside manner and communication intraoperatively in comparison to final surgical outcomes for patient satisfaction. For negative themes, 3 of 4 most common concerns were directly related to the intraoperative and postoperative periods. Providers may be able to improve patient satisfaction by explaining the postoperative course, such as healing time and temporary physical restrictions, as well as possible sequelae in greater detail, which may be particularly pertinent for MMS involving the nose or near the eyes.

The global ratings for MMS are high, as shown in our data set of patient reviews; however, patient reviews are highly susceptible to reporting bias, recall bias, and missing information. Prior work using this online patient review website to investigate laser and light procedures also demonstrated the risk for imperfect information associated with patient reviews.9 Even so, the data does provide a glimpse into what is considered important to patients. Surgeon interpersonal skills and communication were the most frequently cited positive themes for MMS. The best surgical aspects of MMS focused on the unique tissue-sparing nature of the procedure and the removal of a cancerous lesion. Potential areas for improvement include a more thorough explanation of the intraoperative and postoperative process, specifically potential asymmetry related to the nose or the eyes, healing time, and scarring. These patient reviews underscore the importance of setting appropriate patient expectations. As patients become more connected and utilize online platforms to report their experiences, Mohs surgeons can take insights derived from online patient reviews for their own practice or geographic area to improve satisfaction and manage expectations.

- Alam M, Ibrahim O, Nodzenski M, et al. Adverse events associated with Mohs micrographic surgery: multicenter prospective cohort study of 20,821 cases at 23 centers. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1378-1385.

- Fox S. The social life of health information. Pew Research Center website. http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2014/01/15/the-social-life-of-health-information/. Published January 15, 2014. Accessed February 11, 2017.

- Smith RJ, Lipoff JB. Evaluation of dermatology practice online reviews: lessons from qualitative analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:153-157.

- Schlichte MJ, Karimkhani C, Jones T, et al. Patient use of social media to evaluate cosmetic treatments and procedures. Dermatol Online J. 2015;21. pii:13030/qt88z6r65x.

- American Academy of Dermatology; American College of Mohs Surgery; American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Association; American Society for Mohs Surgery; Ad Hoc Task Force, Connolly SM, Baker DR, Coldiron BM, et al. AAD/ACMS/ASDSA/ASMS 2012 appropriate use criteria for Mohs micrographic surgery: a report of the American Academy of Dermatology, American College of Mohs Surgery, American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Association, and the American Society for Mohs Surgery [published online September 7, 2012]. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:1582-1603.

- Asgari MM, Bertenthal D, Sen S, et al. Patient satisfaction after treatment of nonmelanoma skin cancer. Derm Surg. 2009;35:1041-1049.

- Campbell RM, Perlis CS, Malik MK, et al. Characteristics of Mohs practices in the United States: a recall survey of ACMS surgeons. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:1413-1418; discussion, 1418.

- Khansa I, Khansa L, Pearson GD. Patient satisfaction after rhinoplasty: a social media analysis. Aesthet Surg J. 2016;36:NP1-5.

- Xu S, Walter J, Bhatia A. Patient-reported online satisfaction for laser and light procedures: need for caution. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43:154-158.

Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) remains the gold standard for the removal of skin cancers in high-risk areas of the body while offering an excellent safety profile and sparing tissue.1 In the current health care environment, online patient reviews have grown in popularity and influence. More than 60% of consumers consult social media before making health care decisions.2 A recent analysis of online patient reviews of general dermatology practices demonstrated the perceived importance of physician empathy, thoroughness, and cognizance of cost in relation to patient-reported satisfaction.3 Because MMS is a well-recognized and unique outpatient-based surgical procedure, a review and analysis of online patient reviews specific to MMS can provide useful practice insights.

Materials and Methods

This study was conducted using an online platform (RealSelf [http://www.realself.com]) that connects patients and providers offering aesthetically oriented procedures; the site has 35 million unique visitors yearly.4 The community’s directory was used to identify and analyze all cumulative patient reviews from 2006 to December 20, 2015, using the search terms Mohs surgery or Mohs micrographic surgery. The study was exempt by the Northwestern University (Chicago, Illinois) institutional review board.

A standardized qualitative coding methodology was created and applied to all available comments regarding MMS. A broad list of positive and negative patient experiences was first created and agreed upon by all 3 investigators. Each individual comment was then attributed to 1 or more of these positive or negative themes. Of these comments, 10% were coded by 2 investigators (S.X. and Z.A.) to ensure internal validity; 1 investigator coded the remaining statements by patients (Z.A.). Patient-reported satisfaction ratings categorized as “worth it” or “not worth it” (as used by RealSelf to describe the patient-perceived value and utility of a given procedure) as well as cost of MMS were gathered. Cumulative patient ratings were collected for the procedure overall, physician’s bedside manner, answered questions, aftercare follow-up, time spent with patients, telephone/email responsiveness, staff professionalism/courtesy, payment process, and wait times. Patient-reported characteristics of MMS also were evaluated including physician specialty, lesion location, type of skin cancer, and type of closure. For lesion location, we graded whether the location represented a high-risk area as defined by the American Academy of Dermatology, American College of Mohs Surgery, and American Society for Dermatologic Surgery.5

Results

A total of 219 reviews related to MMS were collected as of December 20, 2015. Overall, MMS was considered “worth it” by 89% of patients (Table 1). Only 2% of patients described MMS as “not worth it.” There was a wide range reported for the cost of the procedure ($1–$100,000 [median, $1800]). Of those patients who reported their sex, females were 2.5-times more likely to post a review compared to males (51% vs 20%); however, 30% of reviewers did not report their sex. The mean (standard deviation) overall satisfaction rating was 4.8 (0.8). With regard to category-specific ratings (eg, bedside manner, aftercare follow-up, time spent with patients), the mean scores were all 4.7 or greater (Table 2).

Regarding the surgical aspects of the procedure, the majority of patients reported that the excision of the lesion was performed by a dermatologist (62%). However, a notable portion of patients reported that the excision was performed by a plastic surgeon (21%). Physician specialty was not reported in 16% of the reviews. For the lesion closure, the patient-reported specialty of the physician was only slightly higher for dermatologists versus plastic surgeons (46% vs 44%)(Table 3).

The majority of patients who reported the location of the lesion treated with MMS identified a high-risk location (45%), a medium-risk location (18%), or an unspecified region of the face (15%), according to the appropriate-use criteria for MMS (Table 3).5 Patients did not specify the site of surgery 17% of the time. Only 5% of reported procedures were performed on low-risk areas.

Basal cell carcinomas were the most commonly reported lesions removed by MMS (38%), though 48% of reviews did not specify the type of tumor being treated (Table 3). A large majority (76%) did not specify the type of closure performed. When specified, secondary intention was used 10% of the time, followed by either a flap (6%) or skin graft (6%). Only 5% of patients reported an estimated size of the primary lesion in our study (data not shown).

The qualitative analysis demonstrated variance in themes for positive and negative characteristics (Table 4). Surgeon characteristics encompassed the 3 most commonly cited themes of positive remarks, including bedside manner (78%), communication skills (74%), and perceived expertise (58%). Specific to MMS, the tissue-sparing nature of the technique was cited by 14% of reviews as a positive theme. The most commonly cited themes of negative remarks were intraoperative and postoperative concerns, including postoperative disfigurement (16%), large scar (9%), healing time (9%), and procedural or postoperative pain (8%). A subtheme analysis of postoperative disfigurement revealed that eyelid or eyebrow distortion was the most common concern (29%), followed by redness and swelling (23%), an open wound (14%), and nostril/nose distortion (14%)(data not shown). Themes not commonly cited as either positive or negative included office environment, cost, and procedure time (data not shown).

Comment

The overall satisfaction with MMS (89%) was one of the highest for any procedure on this online patient review site, albeit based on fewer reviews compared to other common aesthetic surgical procedures. In comparison, 78% of 13,500 reviewers rated breast augmentation as “worth it,” while 60% of 6800 reviewers rated rhinoplasty as “worth it” (as of December 2015). Overall, the online patient reviews evaluated in this study were consistent with a previously published structured data report on patient satisfaction with MMS.6

The results show a greater than expected proportion of both the MMS excision and closure being performed by plastic surgeons compared to dermatologists. In reality, the majority of MMS excisions are performed by dermatologists. Based on a survey of American College of Mohs Surgery (ACMS) members, only 6% of procedures were sent to other specialties for closure.7 Our results may reflect reporting bias or patients misconstruing true MMS with an excision and standard frozen sections, techniques that have lower cure rates. If so, there may be a need to educate patients regarding the specifics of MMS. Other possible explanations for the discrepancy between the online patient reviews and ACMS data include misinterpretation by patients on the exact definition of MMS or that a higher than expected number of procedures were performed by non-ACMS Mohs surgeons.

Our qualitative analysis revealed that patients most frequently commented on the interpersonal skills of their surgeons (eg, bedside manner, communication) as positive themes during MMS, similar to prior analyses of general dermatology practices.3 In comparison to a recent study assessing patient satisfaction with rhinoplasty on RealSelf, the final appearance of the nose represented the most common positive- and negative-cited theme.8 Mohs micrographic surgery procedures typically are done under local anesthesia, which may explain the greater importance of bedside manner and communication intraoperatively in comparison to final surgical outcomes for patient satisfaction. For negative themes, 3 of 4 most common concerns were directly related to the intraoperative and postoperative periods. Providers may be able to improve patient satisfaction by explaining the postoperative course, such as healing time and temporary physical restrictions, as well as possible sequelae in greater detail, which may be particularly pertinent for MMS involving the nose or near the eyes.

The global ratings for MMS are high, as shown in our data set of patient reviews; however, patient reviews are highly susceptible to reporting bias, recall bias, and missing information. Prior work using this online patient review website to investigate laser and light procedures also demonstrated the risk for imperfect information associated with patient reviews.9 Even so, the data does provide a glimpse into what is considered important to patients. Surgeon interpersonal skills and communication were the most frequently cited positive themes for MMS. The best surgical aspects of MMS focused on the unique tissue-sparing nature of the procedure and the removal of a cancerous lesion. Potential areas for improvement include a more thorough explanation of the intraoperative and postoperative process, specifically potential asymmetry related to the nose or the eyes, healing time, and scarring. These patient reviews underscore the importance of setting appropriate patient expectations. As patients become more connected and utilize online platforms to report their experiences, Mohs surgeons can take insights derived from online patient reviews for their own practice or geographic area to improve satisfaction and manage expectations.

Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) remains the gold standard for the removal of skin cancers in high-risk areas of the body while offering an excellent safety profile and sparing tissue.1 In the current health care environment, online patient reviews have grown in popularity and influence. More than 60% of consumers consult social media before making health care decisions.2 A recent analysis of online patient reviews of general dermatology practices demonstrated the perceived importance of physician empathy, thoroughness, and cognizance of cost in relation to patient-reported satisfaction.3 Because MMS is a well-recognized and unique outpatient-based surgical procedure, a review and analysis of online patient reviews specific to MMS can provide useful practice insights.

Materials and Methods

This study was conducted using an online platform (RealSelf [http://www.realself.com]) that connects patients and providers offering aesthetically oriented procedures; the site has 35 million unique visitors yearly.4 The community’s directory was used to identify and analyze all cumulative patient reviews from 2006 to December 20, 2015, using the search terms Mohs surgery or Mohs micrographic surgery. The study was exempt by the Northwestern University (Chicago, Illinois) institutional review board.

A standardized qualitative coding methodology was created and applied to all available comments regarding MMS. A broad list of positive and negative patient experiences was first created and agreed upon by all 3 investigators. Each individual comment was then attributed to 1 or more of these positive or negative themes. Of these comments, 10% were coded by 2 investigators (S.X. and Z.A.) to ensure internal validity; 1 investigator coded the remaining statements by patients (Z.A.). Patient-reported satisfaction ratings categorized as “worth it” or “not worth it” (as used by RealSelf to describe the patient-perceived value and utility of a given procedure) as well as cost of MMS were gathered. Cumulative patient ratings were collected for the procedure overall, physician’s bedside manner, answered questions, aftercare follow-up, time spent with patients, telephone/email responsiveness, staff professionalism/courtesy, payment process, and wait times. Patient-reported characteristics of MMS also were evaluated including physician specialty, lesion location, type of skin cancer, and type of closure. For lesion location, we graded whether the location represented a high-risk area as defined by the American Academy of Dermatology, American College of Mohs Surgery, and American Society for Dermatologic Surgery.5

Results

A total of 219 reviews related to MMS were collected as of December 20, 2015. Overall, MMS was considered “worth it” by 89% of patients (Table 1). Only 2% of patients described MMS as “not worth it.” There was a wide range reported for the cost of the procedure ($1–$100,000 [median, $1800]). Of those patients who reported their sex, females were 2.5-times more likely to post a review compared to males (51% vs 20%); however, 30% of reviewers did not report their sex. The mean (standard deviation) overall satisfaction rating was 4.8 (0.8). With regard to category-specific ratings (eg, bedside manner, aftercare follow-up, time spent with patients), the mean scores were all 4.7 or greater (Table 2).

Regarding the surgical aspects of the procedure, the majority of patients reported that the excision of the lesion was performed by a dermatologist (62%). However, a notable portion of patients reported that the excision was performed by a plastic surgeon (21%). Physician specialty was not reported in 16% of the reviews. For the lesion closure, the patient-reported specialty of the physician was only slightly higher for dermatologists versus plastic surgeons (46% vs 44%)(Table 3).

The majority of patients who reported the location of the lesion treated with MMS identified a high-risk location (45%), a medium-risk location (18%), or an unspecified region of the face (15%), according to the appropriate-use criteria for MMS (Table 3).5 Patients did not specify the site of surgery 17% of the time. Only 5% of reported procedures were performed on low-risk areas.

Basal cell carcinomas were the most commonly reported lesions removed by MMS (38%), though 48% of reviews did not specify the type of tumor being treated (Table 3). A large majority (76%) did not specify the type of closure performed. When specified, secondary intention was used 10% of the time, followed by either a flap (6%) or skin graft (6%). Only 5% of patients reported an estimated size of the primary lesion in our study (data not shown).

The qualitative analysis demonstrated variance in themes for positive and negative characteristics (Table 4). Surgeon characteristics encompassed the 3 most commonly cited themes of positive remarks, including bedside manner (78%), communication skills (74%), and perceived expertise (58%). Specific to MMS, the tissue-sparing nature of the technique was cited by 14% of reviews as a positive theme. The most commonly cited themes of negative remarks were intraoperative and postoperative concerns, including postoperative disfigurement (16%), large scar (9%), healing time (9%), and procedural or postoperative pain (8%). A subtheme analysis of postoperative disfigurement revealed that eyelid or eyebrow distortion was the most common concern (29%), followed by redness and swelling (23%), an open wound (14%), and nostril/nose distortion (14%)(data not shown). Themes not commonly cited as either positive or negative included office environment, cost, and procedure time (data not shown).

Comment

The overall satisfaction with MMS (89%) was one of the highest for any procedure on this online patient review site, albeit based on fewer reviews compared to other common aesthetic surgical procedures. In comparison, 78% of 13,500 reviewers rated breast augmentation as “worth it,” while 60% of 6800 reviewers rated rhinoplasty as “worth it” (as of December 2015). Overall, the online patient reviews evaluated in this study were consistent with a previously published structured data report on patient satisfaction with MMS.6

The results show a greater than expected proportion of both the MMS excision and closure being performed by plastic surgeons compared to dermatologists. In reality, the majority of MMS excisions are performed by dermatologists. Based on a survey of American College of Mohs Surgery (ACMS) members, only 6% of procedures were sent to other specialties for closure.7 Our results may reflect reporting bias or patients misconstruing true MMS with an excision and standard frozen sections, techniques that have lower cure rates. If so, there may be a need to educate patients regarding the specifics of MMS. Other possible explanations for the discrepancy between the online patient reviews and ACMS data include misinterpretation by patients on the exact definition of MMS or that a higher than expected number of procedures were performed by non-ACMS Mohs surgeons.

Our qualitative analysis revealed that patients most frequently commented on the interpersonal skills of their surgeons (eg, bedside manner, communication) as positive themes during MMS, similar to prior analyses of general dermatology practices.3 In comparison to a recent study assessing patient satisfaction with rhinoplasty on RealSelf, the final appearance of the nose represented the most common positive- and negative-cited theme.8 Mohs micrographic surgery procedures typically are done under local anesthesia, which may explain the greater importance of bedside manner and communication intraoperatively in comparison to final surgical outcomes for patient satisfaction. For negative themes, 3 of 4 most common concerns were directly related to the intraoperative and postoperative periods. Providers may be able to improve patient satisfaction by explaining the postoperative course, such as healing time and temporary physical restrictions, as well as possible sequelae in greater detail, which may be particularly pertinent for MMS involving the nose or near the eyes.

The global ratings for MMS are high, as shown in our data set of patient reviews; however, patient reviews are highly susceptible to reporting bias, recall bias, and missing information. Prior work using this online patient review website to investigate laser and light procedures also demonstrated the risk for imperfect information associated with patient reviews.9 Even so, the data does provide a glimpse into what is considered important to patients. Surgeon interpersonal skills and communication were the most frequently cited positive themes for MMS. The best surgical aspects of MMS focused on the unique tissue-sparing nature of the procedure and the removal of a cancerous lesion. Potential areas for improvement include a more thorough explanation of the intraoperative and postoperative process, specifically potential asymmetry related to the nose or the eyes, healing time, and scarring. These patient reviews underscore the importance of setting appropriate patient expectations. As patients become more connected and utilize online platforms to report their experiences, Mohs surgeons can take insights derived from online patient reviews for their own practice or geographic area to improve satisfaction and manage expectations.

- Alam M, Ibrahim O, Nodzenski M, et al. Adverse events associated with Mohs micrographic surgery: multicenter prospective cohort study of 20,821 cases at 23 centers. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1378-1385.

- Fox S. The social life of health information. Pew Research Center website. http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2014/01/15/the-social-life-of-health-information/. Published January 15, 2014. Accessed February 11, 2017.

- Smith RJ, Lipoff JB. Evaluation of dermatology practice online reviews: lessons from qualitative analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:153-157.

- Schlichte MJ, Karimkhani C, Jones T, et al. Patient use of social media to evaluate cosmetic treatments and procedures. Dermatol Online J. 2015;21. pii:13030/qt88z6r65x.

- American Academy of Dermatology; American College of Mohs Surgery; American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Association; American Society for Mohs Surgery; Ad Hoc Task Force, Connolly SM, Baker DR, Coldiron BM, et al. AAD/ACMS/ASDSA/ASMS 2012 appropriate use criteria for Mohs micrographic surgery: a report of the American Academy of Dermatology, American College of Mohs Surgery, American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Association, and the American Society for Mohs Surgery [published online September 7, 2012]. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:1582-1603.

- Asgari MM, Bertenthal D, Sen S, et al. Patient satisfaction after treatment of nonmelanoma skin cancer. Derm Surg. 2009;35:1041-1049.

- Campbell RM, Perlis CS, Malik MK, et al. Characteristics of Mohs practices in the United States: a recall survey of ACMS surgeons. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:1413-1418; discussion, 1418.

- Khansa I, Khansa L, Pearson GD. Patient satisfaction after rhinoplasty: a social media analysis. Aesthet Surg J. 2016;36:NP1-5.

- Xu S, Walter J, Bhatia A. Patient-reported online satisfaction for laser and light procedures: need for caution. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43:154-158.

- Alam M, Ibrahim O, Nodzenski M, et al. Adverse events associated with Mohs micrographic surgery: multicenter prospective cohort study of 20,821 cases at 23 centers. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1378-1385.

- Fox S. The social life of health information. Pew Research Center website. http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2014/01/15/the-social-life-of-health-information/. Published January 15, 2014. Accessed February 11, 2017.

- Smith RJ, Lipoff JB. Evaluation of dermatology practice online reviews: lessons from qualitative analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:153-157.

- Schlichte MJ, Karimkhani C, Jones T, et al. Patient use of social media to evaluate cosmetic treatments and procedures. Dermatol Online J. 2015;21. pii:13030/qt88z6r65x.

- American Academy of Dermatology; American College of Mohs Surgery; American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Association; American Society for Mohs Surgery; Ad Hoc Task Force, Connolly SM, Baker DR, Coldiron BM, et al. AAD/ACMS/ASDSA/ASMS 2012 appropriate use criteria for Mohs micrographic surgery: a report of the American Academy of Dermatology, American College of Mohs Surgery, American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Association, and the American Society for Mohs Surgery [published online September 7, 2012]. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:1582-1603.

- Asgari MM, Bertenthal D, Sen S, et al. Patient satisfaction after treatment of nonmelanoma skin cancer. Derm Surg. 2009;35:1041-1049.

- Campbell RM, Perlis CS, Malik MK, et al. Characteristics of Mohs practices in the United States: a recall survey of ACMS surgeons. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:1413-1418; discussion, 1418.

- Khansa I, Khansa L, Pearson GD. Patient satisfaction after rhinoplasty: a social media analysis. Aesthet Surg J. 2016;36:NP1-5.

- Xu S, Walter J, Bhatia A. Patient-reported online satisfaction for laser and light procedures: need for caution. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43:154-158.

Resident Pearl

Patients are posting reviews online now more than ever regarding their experiences with dermatologic surgical procedures. Mohs micrographic surgery is rated highly by patients but suspect to missing information and a higher than expected attribution of the procedure to plastic surgeons.

Accuracy and Sources of Images From Direct Google Image Searches for Common Dermatology Terms

To the Editor:

Prior studies have assessed the quality of text-based dermatology information on the Internet using traditional search engine queries.1 However, little is understood about the sources, accuracy, and quality of online dermatology images derived from direct image searches. Previous work has shown that direct search engine image queries were largely accurate for 3 pediatric dermatology diagnosis searches: atopic dermatitis, lichen striatus, and subcutaneous fat necrosis.2 We assessed images obtained for common dermatologic conditions from a Google image search (GIS) compared to a traditional text-based Google web search (GWS).

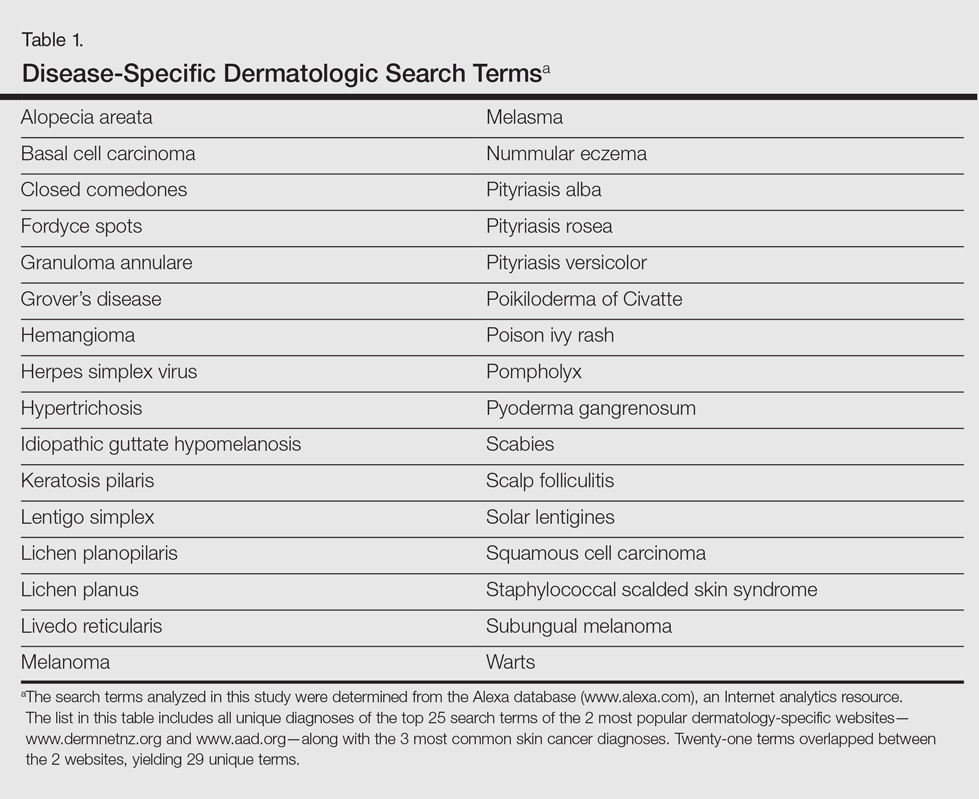

Image results for 32 unique dermatologic search terms were analyzed (Table 1). These search terms were selected using the results of a prior study that identified the most common dermatologic diagnoses that led users to the 2 most popular dermatology-specific websites worldwide: the American Academy of Dermatology (www.aad.org) and DermNet New Zealand (www.dermnetnz.org).3 The Alexa directory (www.alexa.com), a large publicly available Internet analytics resource, was used to determine the most common dermatology search terms that led a user to either www.dermnetnz.org or www.aad.org. In addition, searches for the 3 most common types of skin cancer—melanoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and basal cell carcinoma—were included. Each term was entered into a GIS and a GWS. The first 10 results, which represent 92% of the websites ultimately visited by users,4 were analyzed. The source, diagnostic accuracy, and Fitzpatrick skin type of the images was determined. Website sources were organized into 11 categories. All data collection occurred within a 1-week period in August 2015.

A total of 320 images were analyzed. In the GIS, private websites (36%), dermatology association websites (28%), and general health information websites (10%) were the 3 most common sources. In the GWS, health information websites (35%), private websites (21%), and dermatology association websites (20%) accounted for the most common sources (Table 2). The majority of images were of Fitzpatrick skin types I and II (89%) and nearly all images were diagnostically accurate (98%). There was no statistically significant difference in accuracy of diagnosis between physician-associated websites (100% accuracy) versus nonphysician-associated sites (98% accuracy, P=.25).

Our results showed high diagnostic accuracy among the top GIS results for common dermatology search terms. Diagnostic accuracy did not vary between websites that were physician associated versus those that were not. Our results are comparable to the reported accuracy of online dermatologic health information.1 In GIS results, the majority of images were provided by private websites, whereas the top websites in GWS results were health information websites.

Only 1% of images were of Fitzpatrick skin types VI and VII. Presentation of skin diseases is remarkably different based on the patient’s skin type.5 The shortage of readily accessible images of skin of color is in line with the lack of familiarity physicians and trainees have with dermatologic conditions in ethnic skin.6

Based on the results from this analysis, providers and patients searching for dermatologic conditions via a direct GIS should be cognizant of several considerations. Although our results showed that GIS was accurate, the searcher should note that image-based searches are not accompanied by relevant text that can help confirm relevancy and accuracy. Image searches depend on textual tags added by the source website. Websites that represent dermatological associations and academic centers can add an additional layer of confidence for users. Patients and clinicians also should be aware that the consideration of a patient’s Fitzpatrick skin type is critical when assessing the relevancy of a GIS result. In conclusion, search results via GIS queries are accurate for the dermatological diagnoses tested but may be lacking in skin of color variations, suggesting a potential unmet need based on our growing ethnic skin population.

- Jensen JD, Dunnick CA, Arbuckle HA, et al. Dermatology information on the Internet: an appraisal by dermatologists and dermatology residents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:1101-1103.

- Cutrone M, Grimalt R. Dermatological image search engines on the Internet: do they work? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:175-177.

- Xu S, Nault A, Bhatia A. Search and engagement analysis of association websites representing dermatologists—implications and opportunities for web visibility and patient education: website rankings of dermatology associations. Pract Dermatol. In press.

- comScore releases July 2015 U.S. desktop search engine rankings [press release]. Reston, VA: comScore, Inc; August 14, 2015. http://www.comscore.com/Insights/Market-Rankings/comScore-Releases-July-2015-U.S.-Desktop-Search-Engine-Rankings. Accessed October 18, 2016.

- Kundu RV, Patterson S. Dermatologic conditions in skin of color: part I. special considerations for common skin disorders. Am Fam Physician. 2013;87:850-856.

- Nijhawan RI, Jacob SE, Woolery-Lloyd H. Skin of color education in dermatology residency programs: does residency training reflect the changing demographics of the United States? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:615-618.

To the Editor:

Prior studies have assessed the quality of text-based dermatology information on the Internet using traditional search engine queries.1 However, little is understood about the sources, accuracy, and quality of online dermatology images derived from direct image searches. Previous work has shown that direct search engine image queries were largely accurate for 3 pediatric dermatology diagnosis searches: atopic dermatitis, lichen striatus, and subcutaneous fat necrosis.2 We assessed images obtained for common dermatologic conditions from a Google image search (GIS) compared to a traditional text-based Google web search (GWS).

Image results for 32 unique dermatologic search terms were analyzed (Table 1). These search terms were selected using the results of a prior study that identified the most common dermatologic diagnoses that led users to the 2 most popular dermatology-specific websites worldwide: the American Academy of Dermatology (www.aad.org) and DermNet New Zealand (www.dermnetnz.org).3 The Alexa directory (www.alexa.com), a large publicly available Internet analytics resource, was used to determine the most common dermatology search terms that led a user to either www.dermnetnz.org or www.aad.org. In addition, searches for the 3 most common types of skin cancer—melanoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and basal cell carcinoma—were included. Each term was entered into a GIS and a GWS. The first 10 results, which represent 92% of the websites ultimately visited by users,4 were analyzed. The source, diagnostic accuracy, and Fitzpatrick skin type of the images was determined. Website sources were organized into 11 categories. All data collection occurred within a 1-week period in August 2015.

A total of 320 images were analyzed. In the GIS, private websites (36%), dermatology association websites (28%), and general health information websites (10%) were the 3 most common sources. In the GWS, health information websites (35%), private websites (21%), and dermatology association websites (20%) accounted for the most common sources (Table 2). The majority of images were of Fitzpatrick skin types I and II (89%) and nearly all images were diagnostically accurate (98%). There was no statistically significant difference in accuracy of diagnosis between physician-associated websites (100% accuracy) versus nonphysician-associated sites (98% accuracy, P=.25).

Our results showed high diagnostic accuracy among the top GIS results for common dermatology search terms. Diagnostic accuracy did not vary between websites that were physician associated versus those that were not. Our results are comparable to the reported accuracy of online dermatologic health information.1 In GIS results, the majority of images were provided by private websites, whereas the top websites in GWS results were health information websites.

Only 1% of images were of Fitzpatrick skin types VI and VII. Presentation of skin diseases is remarkably different based on the patient’s skin type.5 The shortage of readily accessible images of skin of color is in line with the lack of familiarity physicians and trainees have with dermatologic conditions in ethnic skin.6

Based on the results from this analysis, providers and patients searching for dermatologic conditions via a direct GIS should be cognizant of several considerations. Although our results showed that GIS was accurate, the searcher should note that image-based searches are not accompanied by relevant text that can help confirm relevancy and accuracy. Image searches depend on textual tags added by the source website. Websites that represent dermatological associations and academic centers can add an additional layer of confidence for users. Patients and clinicians also should be aware that the consideration of a patient’s Fitzpatrick skin type is critical when assessing the relevancy of a GIS result. In conclusion, search results via GIS queries are accurate for the dermatological diagnoses tested but may be lacking in skin of color variations, suggesting a potential unmet need based on our growing ethnic skin population.

To the Editor:

Prior studies have assessed the quality of text-based dermatology information on the Internet using traditional search engine queries.1 However, little is understood about the sources, accuracy, and quality of online dermatology images derived from direct image searches. Previous work has shown that direct search engine image queries were largely accurate for 3 pediatric dermatology diagnosis searches: atopic dermatitis, lichen striatus, and subcutaneous fat necrosis.2 We assessed images obtained for common dermatologic conditions from a Google image search (GIS) compared to a traditional text-based Google web search (GWS).

Image results for 32 unique dermatologic search terms were analyzed (Table 1). These search terms were selected using the results of a prior study that identified the most common dermatologic diagnoses that led users to the 2 most popular dermatology-specific websites worldwide: the American Academy of Dermatology (www.aad.org) and DermNet New Zealand (www.dermnetnz.org).3 The Alexa directory (www.alexa.com), a large publicly available Internet analytics resource, was used to determine the most common dermatology search terms that led a user to either www.dermnetnz.org or www.aad.org. In addition, searches for the 3 most common types of skin cancer—melanoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and basal cell carcinoma—were included. Each term was entered into a GIS and a GWS. The first 10 results, which represent 92% of the websites ultimately visited by users,4 were analyzed. The source, diagnostic accuracy, and Fitzpatrick skin type of the images was determined. Website sources were organized into 11 categories. All data collection occurred within a 1-week period in August 2015.

A total of 320 images were analyzed. In the GIS, private websites (36%), dermatology association websites (28%), and general health information websites (10%) were the 3 most common sources. In the GWS, health information websites (35%), private websites (21%), and dermatology association websites (20%) accounted for the most common sources (Table 2). The majority of images were of Fitzpatrick skin types I and II (89%) and nearly all images were diagnostically accurate (98%). There was no statistically significant difference in accuracy of diagnosis between physician-associated websites (100% accuracy) versus nonphysician-associated sites (98% accuracy, P=.25).

Our results showed high diagnostic accuracy among the top GIS results for common dermatology search terms. Diagnostic accuracy did not vary between websites that were physician associated versus those that were not. Our results are comparable to the reported accuracy of online dermatologic health information.1 In GIS results, the majority of images were provided by private websites, whereas the top websites in GWS results were health information websites.

Only 1% of images were of Fitzpatrick skin types VI and VII. Presentation of skin diseases is remarkably different based on the patient’s skin type.5 The shortage of readily accessible images of skin of color is in line with the lack of familiarity physicians and trainees have with dermatologic conditions in ethnic skin.6

Based on the results from this analysis, providers and patients searching for dermatologic conditions via a direct GIS should be cognizant of several considerations. Although our results showed that GIS was accurate, the searcher should note that image-based searches are not accompanied by relevant text that can help confirm relevancy and accuracy. Image searches depend on textual tags added by the source website. Websites that represent dermatological associations and academic centers can add an additional layer of confidence for users. Patients and clinicians also should be aware that the consideration of a patient’s Fitzpatrick skin type is critical when assessing the relevancy of a GIS result. In conclusion, search results via GIS queries are accurate for the dermatological diagnoses tested but may be lacking in skin of color variations, suggesting a potential unmet need based on our growing ethnic skin population.

- Jensen JD, Dunnick CA, Arbuckle HA, et al. Dermatology information on the Internet: an appraisal by dermatologists and dermatology residents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:1101-1103.

- Cutrone M, Grimalt R. Dermatological image search engines on the Internet: do they work? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:175-177.

- Xu S, Nault A, Bhatia A. Search and engagement analysis of association websites representing dermatologists—implications and opportunities for web visibility and patient education: website rankings of dermatology associations. Pract Dermatol. In press.

- comScore releases July 2015 U.S. desktop search engine rankings [press release]. Reston, VA: comScore, Inc; August 14, 2015. http://www.comscore.com/Insights/Market-Rankings/comScore-Releases-July-2015-U.S.-Desktop-Search-Engine-Rankings. Accessed October 18, 2016.

- Kundu RV, Patterson S. Dermatologic conditions in skin of color: part I. special considerations for common skin disorders. Am Fam Physician. 2013;87:850-856.

- Nijhawan RI, Jacob SE, Woolery-Lloyd H. Skin of color education in dermatology residency programs: does residency training reflect the changing demographics of the United States? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:615-618.

- Jensen JD, Dunnick CA, Arbuckle HA, et al. Dermatology information on the Internet: an appraisal by dermatologists and dermatology residents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:1101-1103.

- Cutrone M, Grimalt R. Dermatological image search engines on the Internet: do they work? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:175-177.

- Xu S, Nault A, Bhatia A. Search and engagement analysis of association websites representing dermatologists—implications and opportunities for web visibility and patient education: website rankings of dermatology associations. Pract Dermatol. In press.

- comScore releases July 2015 U.S. desktop search engine rankings [press release]. Reston, VA: comScore, Inc; August 14, 2015. http://www.comscore.com/Insights/Market-Rankings/comScore-Releases-July-2015-U.S.-Desktop-Search-Engine-Rankings. Accessed October 18, 2016.

- Kundu RV, Patterson S. Dermatologic conditions in skin of color: part I. special considerations for common skin disorders. Am Fam Physician. 2013;87:850-856.

- Nijhawan RI, Jacob SE, Woolery-Lloyd H. Skin of color education in dermatology residency programs: does residency training reflect the changing demographics of the United States? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:615-618.

Practice Points

- Direct Google image searches largely deliver accurate results for common dermatological diagnoses.

- Greater effort should be made to include more publicly available images for dermatological diseases in darker skin types.

Nevus Spilus: Is the Presence of Hair Associated With an Increased Risk for Melanoma?

The term nevus spilus (NS), also known as speckled lentiginous nevus, was first used in the 19th century to describe lesions with background café au lait–like lentiginous melanocytic hyperplasia speckled with small, 1- to 3-mm, darker foci. The dark spots reflect lentigines; junctional, compound, and intradermal nevus cell nests; and more rarely Spitz and blue nevi. Both macular and papular subtypes have been described.1 This birthmark is quite common, occurring in 1.3% to 2.3% of the adult population worldwide.2 Hypertrichosis has been described in NS.3-9 Two subsequent cases of malignant melanoma in hairy NS suggested that lesions may be particularly prone to malignant degeneration.4,8 We report an additional case of hairy NS that was not associated with melanoma and consider whether dermatologists should warn their patients about this association.

Case Report

A 26-year-old woman presented with a stable 7×8-cm, tan-brown, macular, pigmented birthmark studded with darker 1- to 2-mm, irregular, brown-black and blue, confettilike macules on the left proximal lateral thigh that had been present since birth (Figure 1). Dark terminal hairs were present, arising from both the darker and lighter pigmented areas but not the surrounding normal skin.

A 4-mm punch biopsy from one of the dark blue macules demonstrated uniform lentiginous melanocytic hyperplasia and nevus cell nests adjacent to the sweat glands extending into the mid dermis (Figure 2). No clinical evidence of malignant degeneration was present.

Comment

The risk for melanoma is increased in classic nonspeckled congenital nevi and the risk correlates with the size of the lesion and most probably the number of nevus cells in the lesion that increase the risk for a random mutation.8,10,11 It is likely that NS with or without hair presages a small increased risk for melanoma,6,9,12 which is not surprising because NS is a subtype of congenital melanocytic nevus (CMN), a condition that is present at birth and results from a proliferation of melanocytes.6 Nevus spilus, however, appears to have a notably lower risk for malignant degeneration than other classic CMN of the same size. The following support for this hypothesis is offered: First, CMN have nevus cells broadly filling the dermis that extend more deeply into the dermis than NS (Figure 2A).10 In our estimation, CMN have at least 100 times the number of nevus cells per square centimeter compared to NS. The potential for malignant degeneration of any one melanocyte is greater when more are present. Second, although some NS lesions evolve, classic CMN are universally more proliferative than NS.10,13 The involved skin in CMN thickens over time with increased numbers of melanocytes and marked overgrowth of adjacent tissue. Melanocytes in a proliferative phase may be more likely to undergo malignant degeneration.10

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search term nevus spilus and melanoma yielded 2 cases4,8 of melanoma arising among 15 cases of hairy NS in the literature, which led to the suggestion that the presence of hair could be associated with an increased risk for malignant degeneration in NS (Table). This apparent high incidence of melanoma most likely reflects referral/publication bias rather than a statistically significant association. In fact, the clinical lesion most clinically similar to hairy NS is Becker nevus, with tan macules demonstrating lentiginous melanocytic hyperplasia associated with numerous coarse terminal hairs. There is no indication that Becker nevi have a considerable premalignant potential, though one case of melanoma arising in a Becker nevus has been reported.9 There is no evidence to suggest that classic CMN with hypertrichosis has a greater premalignant potential than similar lesions without hypertrichosis.

We noticed the presence of hair in our patient’s lesion only after reports in the literature caused us to look for this phenomenon.9 This occurrence may actually be quite common. We do not recommend prophylactic excision of NS and believe the risk for malignant degeneration is low in NS with or without hair, though larger NS (>4 cm), especially giant, zosteriform, or segmental lesions, may have a greater risk.1,6,9,10 It is prudent for physicians to carefully examine NS and sample suspicious foci, especially when patients describe a lesion as changing.

- Vidaurri-de la Cruz H, Happle R. Two distinct types of speckled lentiginous nevi characterized by macular versus papular speckles. Dermatology. 2006;212:53-58.

- Ly L, Christie M, Swain S, et al. Melanoma(s) arising in large segmental speckled lentiginous nevi: a case series. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:1190-1193.

- Prose NS, Heilman E, Felman YM, et al. Multiple benign juvenile melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;9:236-242.

- Grinspan D, Casala A, Abulafia J, et al. Melanoma on dysplastic nevus spilus. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36:499-502 .

- Langenbach N, Pfau A, Landthaler M, et al. Naevi spili, café-au-lait spots and melanocytic naevi aggregated alongside Blaschko’s lines, with a review of segmental melanocytic lesions. Acta Derm Venereol. 1998;78:378-380.

- Schaffer JV, Orlow SJ, Lazova R, et al. Speckled lentiginous nevus: within the spectrum of congenital melanocytic nevi. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:172-178.

- Saraswat A, Dogra S, Bansali A, et al. Phakomatosis pigmentokeratotica associated with hypophosphataemic vitamin D–resistant rickets: improvement in phosphate homeostasis after partial laser ablation. Br J Dermatol. 2003;148:1074-1076.

- Zeren-Bilgin

i , Gür S, Aydın O, et al. Melanoma arising in a hairy nevus spilus. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1362-1364. - Singh S, Jain N, Khanna N, et al. Hairy nevus spilus: a case series. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:100-104.

- Price HN, Schaffer JV. Congenital melanocytic nevi—when to worry and how to treat: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2010;28:293-302.

- Alikhan Ali, Ibrahimi OA, Eisen DB. Congenital melanocytic nevi: where are we now? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:495.e1-495.e17.

- Haenssle HA, Kaune KM, Buhl T, et al. Melanoma arising in segmental nevus spilus: detection by sequential digital dermatoscopy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:337-341.

- Cohen LM. Nevus spilus: congenital or acquired? Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:215-216.

The term nevus spilus (NS), also known as speckled lentiginous nevus, was first used in the 19th century to describe lesions with background café au lait–like lentiginous melanocytic hyperplasia speckled with small, 1- to 3-mm, darker foci. The dark spots reflect lentigines; junctional, compound, and intradermal nevus cell nests; and more rarely Spitz and blue nevi. Both macular and papular subtypes have been described.1 This birthmark is quite common, occurring in 1.3% to 2.3% of the adult population worldwide.2 Hypertrichosis has been described in NS.3-9 Two subsequent cases of malignant melanoma in hairy NS suggested that lesions may be particularly prone to malignant degeneration.4,8 We report an additional case of hairy NS that was not associated with melanoma and consider whether dermatologists should warn their patients about this association.

Case Report

A 26-year-old woman presented with a stable 7×8-cm, tan-brown, macular, pigmented birthmark studded with darker 1- to 2-mm, irregular, brown-black and blue, confettilike macules on the left proximal lateral thigh that had been present since birth (Figure 1). Dark terminal hairs were present, arising from both the darker and lighter pigmented areas but not the surrounding normal skin.

A 4-mm punch biopsy from one of the dark blue macules demonstrated uniform lentiginous melanocytic hyperplasia and nevus cell nests adjacent to the sweat glands extending into the mid dermis (Figure 2). No clinical evidence of malignant degeneration was present.

Comment

The risk for melanoma is increased in classic nonspeckled congenital nevi and the risk correlates with the size of the lesion and most probably the number of nevus cells in the lesion that increase the risk for a random mutation.8,10,11 It is likely that NS with or without hair presages a small increased risk for melanoma,6,9,12 which is not surprising because NS is a subtype of congenital melanocytic nevus (CMN), a condition that is present at birth and results from a proliferation of melanocytes.6 Nevus spilus, however, appears to have a notably lower risk for malignant degeneration than other classic CMN of the same size. The following support for this hypothesis is offered: First, CMN have nevus cells broadly filling the dermis that extend more deeply into the dermis than NS (Figure 2A).10 In our estimation, CMN have at least 100 times the number of nevus cells per square centimeter compared to NS. The potential for malignant degeneration of any one melanocyte is greater when more are present. Second, although some NS lesions evolve, classic CMN are universally more proliferative than NS.10,13 The involved skin in CMN thickens over time with increased numbers of melanocytes and marked overgrowth of adjacent tissue. Melanocytes in a proliferative phase may be more likely to undergo malignant degeneration.10

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search term nevus spilus and melanoma yielded 2 cases4,8 of melanoma arising among 15 cases of hairy NS in the literature, which led to the suggestion that the presence of hair could be associated with an increased risk for malignant degeneration in NS (Table). This apparent high incidence of melanoma most likely reflects referral/publication bias rather than a statistically significant association. In fact, the clinical lesion most clinically similar to hairy NS is Becker nevus, with tan macules demonstrating lentiginous melanocytic hyperplasia associated with numerous coarse terminal hairs. There is no indication that Becker nevi have a considerable premalignant potential, though one case of melanoma arising in a Becker nevus has been reported.9 There is no evidence to suggest that classic CMN with hypertrichosis has a greater premalignant potential than similar lesions without hypertrichosis.

We noticed the presence of hair in our patient’s lesion only after reports in the literature caused us to look for this phenomenon.9 This occurrence may actually be quite common. We do not recommend prophylactic excision of NS and believe the risk for malignant degeneration is low in NS with or without hair, though larger NS (>4 cm), especially giant, zosteriform, or segmental lesions, may have a greater risk.1,6,9,10 It is prudent for physicians to carefully examine NS and sample suspicious foci, especially when patients describe a lesion as changing.

The term nevus spilus (NS), also known as speckled lentiginous nevus, was first used in the 19th century to describe lesions with background café au lait–like lentiginous melanocytic hyperplasia speckled with small, 1- to 3-mm, darker foci. The dark spots reflect lentigines; junctional, compound, and intradermal nevus cell nests; and more rarely Spitz and blue nevi. Both macular and papular subtypes have been described.1 This birthmark is quite common, occurring in 1.3% to 2.3% of the adult population worldwide.2 Hypertrichosis has been described in NS.3-9 Two subsequent cases of malignant melanoma in hairy NS suggested that lesions may be particularly prone to malignant degeneration.4,8 We report an additional case of hairy NS that was not associated with melanoma and consider whether dermatologists should warn their patients about this association.

Case Report

A 26-year-old woman presented with a stable 7×8-cm, tan-brown, macular, pigmented birthmark studded with darker 1- to 2-mm, irregular, brown-black and blue, confettilike macules on the left proximal lateral thigh that had been present since birth (Figure 1). Dark terminal hairs were present, arising from both the darker and lighter pigmented areas but not the surrounding normal skin.

A 4-mm punch biopsy from one of the dark blue macules demonstrated uniform lentiginous melanocytic hyperplasia and nevus cell nests adjacent to the sweat glands extending into the mid dermis (Figure 2). No clinical evidence of malignant degeneration was present.

Comment

The risk for melanoma is increased in classic nonspeckled congenital nevi and the risk correlates with the size of the lesion and most probably the number of nevus cells in the lesion that increase the risk for a random mutation.8,10,11 It is likely that NS with or without hair presages a small increased risk for melanoma,6,9,12 which is not surprising because NS is a subtype of congenital melanocytic nevus (CMN), a condition that is present at birth and results from a proliferation of melanocytes.6 Nevus spilus, however, appears to have a notably lower risk for malignant degeneration than other classic CMN of the same size. The following support for this hypothesis is offered: First, CMN have nevus cells broadly filling the dermis that extend more deeply into the dermis than NS (Figure 2A).10 In our estimation, CMN have at least 100 times the number of nevus cells per square centimeter compared to NS. The potential for malignant degeneration of any one melanocyte is greater when more are present. Second, although some NS lesions evolve, classic CMN are universally more proliferative than NS.10,13 The involved skin in CMN thickens over time with increased numbers of melanocytes and marked overgrowth of adjacent tissue. Melanocytes in a proliferative phase may be more likely to undergo malignant degeneration.10

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search term nevus spilus and melanoma yielded 2 cases4,8 of melanoma arising among 15 cases of hairy NS in the literature, which led to the suggestion that the presence of hair could be associated with an increased risk for malignant degeneration in NS (Table). This apparent high incidence of melanoma most likely reflects referral/publication bias rather than a statistically significant association. In fact, the clinical lesion most clinically similar to hairy NS is Becker nevus, with tan macules demonstrating lentiginous melanocytic hyperplasia associated with numerous coarse terminal hairs. There is no indication that Becker nevi have a considerable premalignant potential, though one case of melanoma arising in a Becker nevus has been reported.9 There is no evidence to suggest that classic CMN with hypertrichosis has a greater premalignant potential than similar lesions without hypertrichosis.

We noticed the presence of hair in our patient’s lesion only after reports in the literature caused us to look for this phenomenon.9 This occurrence may actually be quite common. We do not recommend prophylactic excision of NS and believe the risk for malignant degeneration is low in NS with or without hair, though larger NS (>4 cm), especially giant, zosteriform, or segmental lesions, may have a greater risk.1,6,9,10 It is prudent for physicians to carefully examine NS and sample suspicious foci, especially when patients describe a lesion as changing.

- Vidaurri-de la Cruz H, Happle R. Two distinct types of speckled lentiginous nevi characterized by macular versus papular speckles. Dermatology. 2006;212:53-58.

- Ly L, Christie M, Swain S, et al. Melanoma(s) arising in large segmental speckled lentiginous nevi: a case series. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:1190-1193.

- Prose NS, Heilman E, Felman YM, et al. Multiple benign juvenile melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;9:236-242.

- Grinspan D, Casala A, Abulafia J, et al. Melanoma on dysplastic nevus spilus. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36:499-502 .

- Langenbach N, Pfau A, Landthaler M, et al. Naevi spili, café-au-lait spots and melanocytic naevi aggregated alongside Blaschko’s lines, with a review of segmental melanocytic lesions. Acta Derm Venereol. 1998;78:378-380.

- Schaffer JV, Orlow SJ, Lazova R, et al. Speckled lentiginous nevus: within the spectrum of congenital melanocytic nevi. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:172-178.

- Saraswat A, Dogra S, Bansali A, et al. Phakomatosis pigmentokeratotica associated with hypophosphataemic vitamin D–resistant rickets: improvement in phosphate homeostasis after partial laser ablation. Br J Dermatol. 2003;148:1074-1076.

- Zeren-Bilgin

i , Gür S, Aydın O, et al. Melanoma arising in a hairy nevus spilus. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1362-1364. - Singh S, Jain N, Khanna N, et al. Hairy nevus spilus: a case series. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:100-104.

- Price HN, Schaffer JV. Congenital melanocytic nevi—when to worry and how to treat: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2010;28:293-302.

- Alikhan Ali, Ibrahimi OA, Eisen DB. Congenital melanocytic nevi: where are we now? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:495.e1-495.e17.

- Haenssle HA, Kaune KM, Buhl T, et al. Melanoma arising in segmental nevus spilus: detection by sequential digital dermatoscopy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:337-341.

- Cohen LM. Nevus spilus: congenital or acquired? Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:215-216.

- Vidaurri-de la Cruz H, Happle R. Two distinct types of speckled lentiginous nevi characterized by macular versus papular speckles. Dermatology. 2006;212:53-58.

- Ly L, Christie M, Swain S, et al. Melanoma(s) arising in large segmental speckled lentiginous nevi: a case series. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:1190-1193.

- Prose NS, Heilman E, Felman YM, et al. Multiple benign juvenile melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;9:236-242.

- Grinspan D, Casala A, Abulafia J, et al. Melanoma on dysplastic nevus spilus. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36:499-502 .

- Langenbach N, Pfau A, Landthaler M, et al. Naevi spili, café-au-lait spots and melanocytic naevi aggregated alongside Blaschko’s lines, with a review of segmental melanocytic lesions. Acta Derm Venereol. 1998;78:378-380.

- Schaffer JV, Orlow SJ, Lazova R, et al. Speckled lentiginous nevus: within the spectrum of congenital melanocytic nevi. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:172-178.

- Saraswat A, Dogra S, Bansali A, et al. Phakomatosis pigmentokeratotica associated with hypophosphataemic vitamin D–resistant rickets: improvement in phosphate homeostasis after partial laser ablation. Br J Dermatol. 2003;148:1074-1076.

- Zeren-Bilgin

i , Gür S, Aydın O, et al. Melanoma arising in a hairy nevus spilus. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1362-1364. - Singh S, Jain N, Khanna N, et al. Hairy nevus spilus: a case series. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:100-104.

- Price HN, Schaffer JV. Congenital melanocytic nevi—when to worry and how to treat: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2010;28:293-302.

- Alikhan Ali, Ibrahimi OA, Eisen DB. Congenital melanocytic nevi: where are we now? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:495.e1-495.e17.

- Haenssle HA, Kaune KM, Buhl T, et al. Melanoma arising in segmental nevus spilus: detection by sequential digital dermatoscopy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:337-341.

- Cohen LM. Nevus spilus: congenital or acquired? Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:215-216.

Practice Points

- Nevus spilus (NS) appears as a café au lait macule studded with darker brown “moles.”

- Although melanoma has been described in NS, it is rare.

- There is no evidence that hairy NS are predisposed to melanoma.