User login

How should we diagnose and manage checkpoint inhibitor-associated colitis?

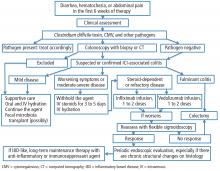

If a patient experiences diarrhea, hematochezia, or abdominal pain within the first 6 weeks of therapy with one of the anticancer drugs known as immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), the first step is to rule out infection, especially with Clostridium difficile. The next step is colonosocopy with biopsy or computed tomography.

Patients with mild ICI-associated colitis may need only supportive care, and the ICI can be continued. In moderate or severe cases, the agent may need to be stopped and corticosteroids and other colitis-targeted agents may be needed. Figure 1 shows our algorithm for diagnosing and treating ICI-associated colitis.

POWERFUL ANTICANCER DRUGS

ICIs are monoclonal antibodies used in treating metastatic melanoma, non-small-cell lung cancer, metastatic prostate cancer, Hodgkin lymphoma, renal cell carcinoma, and other advanced malignancies.1,2 They act by binding to and blocking proteins on T cells, antigen-presenting cells, and tumor cells that keep immune responses in check and prevent T cells from killing cancer cells.1 For example:

- Ipilimumab blocks cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4

- Nivolumab and pembrolizumab block programmed cell death protein 1

- Atezolizumab blocks programmed death ligand 1.1

With these proteins blocked, T cells can do their job, often producing dramatic regression of cancer. However, ICIs can cause a range of immune-related adverse effects, including endocrine and cutaneous toxicities, iridocyclitis, lymphadenopathy, neuropathy, nephritis, immune-mediated pneumonitis, pancreatitis, hepatitis, and colitis.3

ICI-ASSOCIATED COLITIS IS COMMON

ICI-associated colitis is common; it is estimated to affect about 30% of patients receiving ipilimumab, for example.4 Clinical presentations range from watery bowel movements, blood or mucus in the stool, abdominal cramping, and flatulence to ileus, colectasia, intestinal perforation, and even death.5

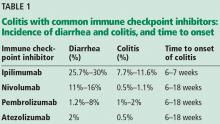

The incidence appears to increase with the dosage and duration of ICI therapy. The onset of colitis typically occurs 6 to 7 weeks after starting ipilimumab,6 and 6 to 18 weeks after starting nivolumab or pembrolizumab.7Table 1 lists the incidence of diarrhea and colitis and time of onset to colitis with common ICIs. However, colitis, like other immune-related adverse events, can occur at any point, even after ICI therapy has been discontinued.8

It is best to detect side effects of ICIs promptly, as acute inflammation can progress to chronic inflammation within 1 month of onset.9 We believe that early intervention and close monitoring may prevent complications and the need for long-term immunosuppressive treatment.

Patients, family members, and caregivers should be informed of possible gastrointestinal along with systemic side effects. Severe gastrointestinal symptoms such as increased stool frequency and change in stool consistency should trigger appropriate investigation and the withholding of ICI therapy.

COLITIS IS A SPECTRUM

The colon appears to be the gastrointestinal organ most affected by ICIs. Of patients with intestinal side effects, including diarrhea, only some develop colitis. The severity of ICI-associated colitis ranges from mild bowel illness to fulminant colitis.

Hodi et al,10 in a randomized trial in which 511 patients with melanoma received ipilimumab, reported that approximately 30% had mild diarrhea, while fewer than 10% had severe diarrhea, fever, ileus, or peritoneal signs. Five patients (1%) developed intestinal perforation, 4 (0.8%) died of complications, and 26 (5%) required hospitalization for severe enterocolitis.

The pathophysiology of ICI-mediated colitis is unclear. Most cases are diagnosed clinically.

Colitis is graded based on the Montreal classification system11:

Mild colitis is defined as passage of fewer than 4 stools per day (with or without blood) over baseline and absence of any systemic illness.

Moderate is passage of more than 4 stools per day but with minimal signs of systemic toxicity.

Severe is defined as passage of at least 6 stools per day, heart rate at least 90 beats per minute, temperature at least 37.5°C (99.5°F), hemoglobin less than 10.5 g/dL, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate at least 30 mm/h.11

RULE OUT INFECTION

If symptoms such as diarrhea or abdominal pain arise within 6 weeks of starting ICI therapy, then we should check for an infectious cause. The differential diagnosis of suspected ICI-associated colitis includes infections with C difficile, cytomegalovirus, opportunistic organisms, and other bacteria and viruses. ICI-induced celiac disease and immune hyperthyroidism should also be ruled out.4

CONSIDER COLONOSCOPY AND BIOPSY

Once infection is ruled out, colonoscopy should be considered if symptoms persist or are severe. Colonoscopy with biopsy remains the gold standard for diagnosis, and it is also helpful in assessing severity of mucosal inflammation and monitoring response to medical treatment.

Table 2 lists common endoscopic and histologic features of ICI-mediated colitis; however, none of them is specific for this disease.

Common endoscopic features are loss of vascular pattern, edema, friability, spontaneous bleeding, and deep ulcerations.12 A recent study suggested that colonic ulcerations predict a steroid-refractory course in patients with immune-mediated colitis.4

Histologically, ICI-associated colitis is characterized by both acute and chronic changes, including an increased number of neutrophils and lymphocytes in the epithelium and lamina propria, erosions, ulcers, crypt abscess, crypt apoptosis, crypt distortion, and even noncaseating granulomas.13 However, transmural disease is rare. Figure 2 compares the histopathologic features of ICI-associated colitis and a normal colon.

COMPUTED TOMOGRAPHY CAN BE USEFUL

Computed tomography (CT) can also be useful for the diagnosis and measurement of severity.

Garcia-Neuer et al14 analyzed 303 patients with advanced melanoma who developed gastrointestinal symptoms while being treated with ipilimumab. Ninety-nine (33%) of them reported diarrhea during therapy, of whom 34 underwent both CT and colonoscopy with biopsy. CT was highly predictive of colitis on biopsy, with a positive predictive value of 96% and a negative likelihood ratio of 0.2.14

TREATMENT

Supportive care may be enough when treating mild ICI-related colitis. This can include oral and intravenous hydration4 and an antidiarrheal drug such as loperamide in a low dose.

Corticosteroids. For moderate ICI-associated colitis with stool frequency of 4 or more per day, patients should be started on an oral corticosteroid such as prednisone 0.5 to 1 mg/kg per day. If symptoms do not improve within 72 hours of starting an oral corticosteroid, the patient should be admitted to the hospital for observation and escalation to higher doses or possibly intravenous corticosteroids.

Infliximab has been used in severe and steroid-refractory cases,13 although there has been concern about using anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agents such as this in patients with malignancies, especially melanoma. Since melanoma can be very aggressive and anti-TNF agents may promote it, it is prudent to try not to use this class of agents.

Other biologic agents such as vedolizumab, a gut-specific anti-integrin agent, are safer, have theoretic advantages over anti-TNF agents, and can be considered in patients with steroid-dependent or steroid-refractory ICI-associated enterocolitis. A recent study suggested that 2 to 4 infusions of vedolizumab are adequate to achieve steroid-free remission.15 Results from 6 clinical trials of vedolizumab in 2,830 patients with Crohn disease or ulcerative colitis did not show any increased risk of serious infections or malignancies over placebo.16,17 A drawback is its slow onset of action.

Surgery is an option for patients with severe colitis refractory to intravenous corticosteroids or biological agents, as severe colitis carries a risk of significant morbidity and even death. The incidence of bowel perforation leading to colectomy or death in patients receiving ICI therapy is 0.5% to 1%.18,19

Fecal microbiota transplant was associated with mucosal healing after 1 month in a case report of ICI-associated colitis.9

Follow-up. In most patients, symptoms resolve with discontinuation of the ICI and brief use of corticosteroids or biological agents. Patients with recurrent or persistent symptoms while on long-term ICI therapy may need periodic endoscopic evaluation, especially if there are chronic structural changes on histologic study.

If patients have recurrent or persistent symptoms along with chronic inflammatory structural changes on histology, a sign of an inflammatory bowel diseaselike condition, long-term maintenance therapy with an anti-inflammatory or immunosuppressant agent may be considered. However, there is no consensus on the treatment of this condition. It can be treated in the same way as classic inflammatory bowel disease in the setting of concurrent or prior history of malignancy, especially melanoma. Certain agents used in inflammatory bowel disease such as methotrexate and vedolizumab carry a lower risk of malignancy than anti-TNF agents and can be considered. A multidisciplinary approach that includes an oncologist, gastroenterologist, infectious disease specialist, and colorectal surgeon is imperative.

- Shih K, Arkenau HT, Infante JR. Clinical impact of checkpoint inhibitors as novel cancer therapies. Drugs 2014; 74(17):1993–2013. doi:10.1007/s40265-014-0305-6

- Mellman I, Coukos G, Dranoff G. Cancer immunotherapy comes of age. Nature 2011; 480(7378):480–489. doi:10.1038/nature10673

- Dine J, Gordon R, Shames Y, Kasler MK, Barton-Burke M. Immune checkpoint inhibitors: an innovation in immunotherapy for the treatment and management of patients with cancer. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs 2017; 4(2):127–135. doi:10.4103/apjon.apjon_4_17

- Prieux-Klotz C, Dior M, Damotte D, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced colitis: diagnosis and management. Target Oncol 2017; 12(3):301–308. doi:10.1007/s11523-017-0495-4

- Howell M, Lee R, Bowyer S, Fusi A, Lorigan P. Optimal management of immune-related toxicities associated with checkpoint inhibitors in lung cancer. Lung Cancer 2015; 88(2):117–123. doi:10.1016/j.lungcan.2015.02.007

- Weber JS, Kähler KC, Hauschild A. Management of immune-related adverse events and kinetics of response with ipilimumab. J Clin Oncol 2012; 30(21):2691–2697. doi:10.1200/JCO.2012.41.6750

- Eigentler TK, Hassel JC, Berking C, et al. Diagnosis, monitoring and management of immune-related adverse drug reactions of anti-PD-1 antibody therapy. Cancer Treat Rev 2016; 45:7–18. doi:10.1016/j.ctrv.2016.02.003

- Postow MA, Sidlow R, Hellmann MD. Immune-related adverse events associated with immune checkpoint blockade. N Engl J Med 2018; 378(2):158–168. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1703481

- Wang Y, DuPont H, Jiang ZD, Jenq R, Zuazua R, Shuttlesworth G. Fecal microbiota transplant for immune-checkpoint inhibitor-induced colitis in a 50 year old with bladder cancer. Gastroenterol 2018; 154(1 suppl). doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2017.11.075

- Hodi FS, O’Day SJ, McDermott DF, et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med 2010; 363(8):711–723. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1003466

- Satsangi J, Silverberg MS, Vermeire S, Colombel JF. The Montreal classification of inflammatory bowel disease: controversies, consensus, and implications. Gut 2006; 55(6):749–753. doi:10.1136/gut.2005.082909

- Rastogi P, Sultan M, Charabaty AJ, Atkins MB, Mattar MC. Ipilimumab associated colitis: an IpiColitis case series at MedStar Georgetown University Hospital. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(14):4373–4378. doi:10.3748/wjg.v21.i14.4373

- Pocha C, Roat J, Viskocil K. Immune-mediated colitis: important to recognize and treat. J Crohns Colitis 2014; 8(2):181–182. doi:10.1016/j.crohns.2013.09.019

- Garcia-Neuer M, Marmarelis ME, Jangi SR, et al. Diagnostic comparison of CT scans and colonoscopy for immune-related colitis in ipilimumab-treated advanced melanoma patients. Cancer Immunol Res 2017; 5(4):286–291. doi:10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-16-0302

- Bergqvist V, Hertervig E, Gedeon P, et al. Vedolizumab treatment for immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced enterocolitis. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2017; 66(5):581–592. doi:10.1007/s00262-017-1962-6

- Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Rutgeerts P, et al; GEMINI 2 Study Group. Vedolizumab as induction and maintenance therapy for Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med 2013; 369(8):711–721. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1215739

- Feagan BG, Rutgeerts P, Sands BE, et al; GEMINI 1 Study Group. Vedolizumab as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med 2013; 369(8):699–710. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1215734

- Kähler KC, Hauschild A. Treatment and side effect management of CTLA-4 antibody therapy in metastatic melanoma. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2011; 9(4):277–286. doi:10.1111/j.1610-0387.2010.07568.x

- Ibrahim RA, Berman DM, DePril V, et al. Ipilimumab safety profile: summary of findings from completed trials in advanced melanoma. J Clin Onc 2011; 29(15 suppl):8583–8583. doi:10.1200/jco.2011.29.15_suppl.8583

If a patient experiences diarrhea, hematochezia, or abdominal pain within the first 6 weeks of therapy with one of the anticancer drugs known as immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), the first step is to rule out infection, especially with Clostridium difficile. The next step is colonosocopy with biopsy or computed tomography.

Patients with mild ICI-associated colitis may need only supportive care, and the ICI can be continued. In moderate or severe cases, the agent may need to be stopped and corticosteroids and other colitis-targeted agents may be needed. Figure 1 shows our algorithm for diagnosing and treating ICI-associated colitis.

POWERFUL ANTICANCER DRUGS

ICIs are monoclonal antibodies used in treating metastatic melanoma, non-small-cell lung cancer, metastatic prostate cancer, Hodgkin lymphoma, renal cell carcinoma, and other advanced malignancies.1,2 They act by binding to and blocking proteins on T cells, antigen-presenting cells, and tumor cells that keep immune responses in check and prevent T cells from killing cancer cells.1 For example:

- Ipilimumab blocks cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4

- Nivolumab and pembrolizumab block programmed cell death protein 1

- Atezolizumab blocks programmed death ligand 1.1

With these proteins blocked, T cells can do their job, often producing dramatic regression of cancer. However, ICIs can cause a range of immune-related adverse effects, including endocrine and cutaneous toxicities, iridocyclitis, lymphadenopathy, neuropathy, nephritis, immune-mediated pneumonitis, pancreatitis, hepatitis, and colitis.3

ICI-ASSOCIATED COLITIS IS COMMON

ICI-associated colitis is common; it is estimated to affect about 30% of patients receiving ipilimumab, for example.4 Clinical presentations range from watery bowel movements, blood or mucus in the stool, abdominal cramping, and flatulence to ileus, colectasia, intestinal perforation, and even death.5

The incidence appears to increase with the dosage and duration of ICI therapy. The onset of colitis typically occurs 6 to 7 weeks after starting ipilimumab,6 and 6 to 18 weeks after starting nivolumab or pembrolizumab.7Table 1 lists the incidence of diarrhea and colitis and time of onset to colitis with common ICIs. However, colitis, like other immune-related adverse events, can occur at any point, even after ICI therapy has been discontinued.8

It is best to detect side effects of ICIs promptly, as acute inflammation can progress to chronic inflammation within 1 month of onset.9 We believe that early intervention and close monitoring may prevent complications and the need for long-term immunosuppressive treatment.

Patients, family members, and caregivers should be informed of possible gastrointestinal along with systemic side effects. Severe gastrointestinal symptoms such as increased stool frequency and change in stool consistency should trigger appropriate investigation and the withholding of ICI therapy.

COLITIS IS A SPECTRUM

The colon appears to be the gastrointestinal organ most affected by ICIs. Of patients with intestinal side effects, including diarrhea, only some develop colitis. The severity of ICI-associated colitis ranges from mild bowel illness to fulminant colitis.

Hodi et al,10 in a randomized trial in which 511 patients with melanoma received ipilimumab, reported that approximately 30% had mild diarrhea, while fewer than 10% had severe diarrhea, fever, ileus, or peritoneal signs. Five patients (1%) developed intestinal perforation, 4 (0.8%) died of complications, and 26 (5%) required hospitalization for severe enterocolitis.

The pathophysiology of ICI-mediated colitis is unclear. Most cases are diagnosed clinically.

Colitis is graded based on the Montreal classification system11:

Mild colitis is defined as passage of fewer than 4 stools per day (with or without blood) over baseline and absence of any systemic illness.

Moderate is passage of more than 4 stools per day but with minimal signs of systemic toxicity.

Severe is defined as passage of at least 6 stools per day, heart rate at least 90 beats per minute, temperature at least 37.5°C (99.5°F), hemoglobin less than 10.5 g/dL, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate at least 30 mm/h.11

RULE OUT INFECTION

If symptoms such as diarrhea or abdominal pain arise within 6 weeks of starting ICI therapy, then we should check for an infectious cause. The differential diagnosis of suspected ICI-associated colitis includes infections with C difficile, cytomegalovirus, opportunistic organisms, and other bacteria and viruses. ICI-induced celiac disease and immune hyperthyroidism should also be ruled out.4

CONSIDER COLONOSCOPY AND BIOPSY

Once infection is ruled out, colonoscopy should be considered if symptoms persist or are severe. Colonoscopy with biopsy remains the gold standard for diagnosis, and it is also helpful in assessing severity of mucosal inflammation and monitoring response to medical treatment.

Table 2 lists common endoscopic and histologic features of ICI-mediated colitis; however, none of them is specific for this disease.

Common endoscopic features are loss of vascular pattern, edema, friability, spontaneous bleeding, and deep ulcerations.12 A recent study suggested that colonic ulcerations predict a steroid-refractory course in patients with immune-mediated colitis.4

Histologically, ICI-associated colitis is characterized by both acute and chronic changes, including an increased number of neutrophils and lymphocytes in the epithelium and lamina propria, erosions, ulcers, crypt abscess, crypt apoptosis, crypt distortion, and even noncaseating granulomas.13 However, transmural disease is rare. Figure 2 compares the histopathologic features of ICI-associated colitis and a normal colon.

COMPUTED TOMOGRAPHY CAN BE USEFUL

Computed tomography (CT) can also be useful for the diagnosis and measurement of severity.

Garcia-Neuer et al14 analyzed 303 patients with advanced melanoma who developed gastrointestinal symptoms while being treated with ipilimumab. Ninety-nine (33%) of them reported diarrhea during therapy, of whom 34 underwent both CT and colonoscopy with biopsy. CT was highly predictive of colitis on biopsy, with a positive predictive value of 96% and a negative likelihood ratio of 0.2.14

TREATMENT

Supportive care may be enough when treating mild ICI-related colitis. This can include oral and intravenous hydration4 and an antidiarrheal drug such as loperamide in a low dose.

Corticosteroids. For moderate ICI-associated colitis with stool frequency of 4 or more per day, patients should be started on an oral corticosteroid such as prednisone 0.5 to 1 mg/kg per day. If symptoms do not improve within 72 hours of starting an oral corticosteroid, the patient should be admitted to the hospital for observation and escalation to higher doses or possibly intravenous corticosteroids.

Infliximab has been used in severe and steroid-refractory cases,13 although there has been concern about using anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agents such as this in patients with malignancies, especially melanoma. Since melanoma can be very aggressive and anti-TNF agents may promote it, it is prudent to try not to use this class of agents.

Other biologic agents such as vedolizumab, a gut-specific anti-integrin agent, are safer, have theoretic advantages over anti-TNF agents, and can be considered in patients with steroid-dependent or steroid-refractory ICI-associated enterocolitis. A recent study suggested that 2 to 4 infusions of vedolizumab are adequate to achieve steroid-free remission.15 Results from 6 clinical trials of vedolizumab in 2,830 patients with Crohn disease or ulcerative colitis did not show any increased risk of serious infections or malignancies over placebo.16,17 A drawback is its slow onset of action.

Surgery is an option for patients with severe colitis refractory to intravenous corticosteroids or biological agents, as severe colitis carries a risk of significant morbidity and even death. The incidence of bowel perforation leading to colectomy or death in patients receiving ICI therapy is 0.5% to 1%.18,19

Fecal microbiota transplant was associated with mucosal healing after 1 month in a case report of ICI-associated colitis.9

Follow-up. In most patients, symptoms resolve with discontinuation of the ICI and brief use of corticosteroids or biological agents. Patients with recurrent or persistent symptoms while on long-term ICI therapy may need periodic endoscopic evaluation, especially if there are chronic structural changes on histologic study.

If patients have recurrent or persistent symptoms along with chronic inflammatory structural changes on histology, a sign of an inflammatory bowel diseaselike condition, long-term maintenance therapy with an anti-inflammatory or immunosuppressant agent may be considered. However, there is no consensus on the treatment of this condition. It can be treated in the same way as classic inflammatory bowel disease in the setting of concurrent or prior history of malignancy, especially melanoma. Certain agents used in inflammatory bowel disease such as methotrexate and vedolizumab carry a lower risk of malignancy than anti-TNF agents and can be considered. A multidisciplinary approach that includes an oncologist, gastroenterologist, infectious disease specialist, and colorectal surgeon is imperative.

If a patient experiences diarrhea, hematochezia, or abdominal pain within the first 6 weeks of therapy with one of the anticancer drugs known as immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), the first step is to rule out infection, especially with Clostridium difficile. The next step is colonosocopy with biopsy or computed tomography.

Patients with mild ICI-associated colitis may need only supportive care, and the ICI can be continued. In moderate or severe cases, the agent may need to be stopped and corticosteroids and other colitis-targeted agents may be needed. Figure 1 shows our algorithm for diagnosing and treating ICI-associated colitis.

POWERFUL ANTICANCER DRUGS

ICIs are monoclonal antibodies used in treating metastatic melanoma, non-small-cell lung cancer, metastatic prostate cancer, Hodgkin lymphoma, renal cell carcinoma, and other advanced malignancies.1,2 They act by binding to and blocking proteins on T cells, antigen-presenting cells, and tumor cells that keep immune responses in check and prevent T cells from killing cancer cells.1 For example:

- Ipilimumab blocks cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4

- Nivolumab and pembrolizumab block programmed cell death protein 1

- Atezolizumab blocks programmed death ligand 1.1

With these proteins blocked, T cells can do their job, often producing dramatic regression of cancer. However, ICIs can cause a range of immune-related adverse effects, including endocrine and cutaneous toxicities, iridocyclitis, lymphadenopathy, neuropathy, nephritis, immune-mediated pneumonitis, pancreatitis, hepatitis, and colitis.3

ICI-ASSOCIATED COLITIS IS COMMON

ICI-associated colitis is common; it is estimated to affect about 30% of patients receiving ipilimumab, for example.4 Clinical presentations range from watery bowel movements, blood or mucus in the stool, abdominal cramping, and flatulence to ileus, colectasia, intestinal perforation, and even death.5

The incidence appears to increase with the dosage and duration of ICI therapy. The onset of colitis typically occurs 6 to 7 weeks after starting ipilimumab,6 and 6 to 18 weeks after starting nivolumab or pembrolizumab.7Table 1 lists the incidence of diarrhea and colitis and time of onset to colitis with common ICIs. However, colitis, like other immune-related adverse events, can occur at any point, even after ICI therapy has been discontinued.8

It is best to detect side effects of ICIs promptly, as acute inflammation can progress to chronic inflammation within 1 month of onset.9 We believe that early intervention and close monitoring may prevent complications and the need for long-term immunosuppressive treatment.

Patients, family members, and caregivers should be informed of possible gastrointestinal along with systemic side effects. Severe gastrointestinal symptoms such as increased stool frequency and change in stool consistency should trigger appropriate investigation and the withholding of ICI therapy.

COLITIS IS A SPECTRUM

The colon appears to be the gastrointestinal organ most affected by ICIs. Of patients with intestinal side effects, including diarrhea, only some develop colitis. The severity of ICI-associated colitis ranges from mild bowel illness to fulminant colitis.

Hodi et al,10 in a randomized trial in which 511 patients with melanoma received ipilimumab, reported that approximately 30% had mild diarrhea, while fewer than 10% had severe diarrhea, fever, ileus, or peritoneal signs. Five patients (1%) developed intestinal perforation, 4 (0.8%) died of complications, and 26 (5%) required hospitalization for severe enterocolitis.

The pathophysiology of ICI-mediated colitis is unclear. Most cases are diagnosed clinically.

Colitis is graded based on the Montreal classification system11:

Mild colitis is defined as passage of fewer than 4 stools per day (with or without blood) over baseline and absence of any systemic illness.

Moderate is passage of more than 4 stools per day but with minimal signs of systemic toxicity.

Severe is defined as passage of at least 6 stools per day, heart rate at least 90 beats per minute, temperature at least 37.5°C (99.5°F), hemoglobin less than 10.5 g/dL, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate at least 30 mm/h.11

RULE OUT INFECTION

If symptoms such as diarrhea or abdominal pain arise within 6 weeks of starting ICI therapy, then we should check for an infectious cause. The differential diagnosis of suspected ICI-associated colitis includes infections with C difficile, cytomegalovirus, opportunistic organisms, and other bacteria and viruses. ICI-induced celiac disease and immune hyperthyroidism should also be ruled out.4

CONSIDER COLONOSCOPY AND BIOPSY

Once infection is ruled out, colonoscopy should be considered if symptoms persist or are severe. Colonoscopy with biopsy remains the gold standard for diagnosis, and it is also helpful in assessing severity of mucosal inflammation and monitoring response to medical treatment.

Table 2 lists common endoscopic and histologic features of ICI-mediated colitis; however, none of them is specific for this disease.

Common endoscopic features are loss of vascular pattern, edema, friability, spontaneous bleeding, and deep ulcerations.12 A recent study suggested that colonic ulcerations predict a steroid-refractory course in patients with immune-mediated colitis.4

Histologically, ICI-associated colitis is characterized by both acute and chronic changes, including an increased number of neutrophils and lymphocytes in the epithelium and lamina propria, erosions, ulcers, crypt abscess, crypt apoptosis, crypt distortion, and even noncaseating granulomas.13 However, transmural disease is rare. Figure 2 compares the histopathologic features of ICI-associated colitis and a normal colon.

COMPUTED TOMOGRAPHY CAN BE USEFUL

Computed tomography (CT) can also be useful for the diagnosis and measurement of severity.

Garcia-Neuer et al14 analyzed 303 patients with advanced melanoma who developed gastrointestinal symptoms while being treated with ipilimumab. Ninety-nine (33%) of them reported diarrhea during therapy, of whom 34 underwent both CT and colonoscopy with biopsy. CT was highly predictive of colitis on biopsy, with a positive predictive value of 96% and a negative likelihood ratio of 0.2.14

TREATMENT

Supportive care may be enough when treating mild ICI-related colitis. This can include oral and intravenous hydration4 and an antidiarrheal drug such as loperamide in a low dose.

Corticosteroids. For moderate ICI-associated colitis with stool frequency of 4 or more per day, patients should be started on an oral corticosteroid such as prednisone 0.5 to 1 mg/kg per day. If symptoms do not improve within 72 hours of starting an oral corticosteroid, the patient should be admitted to the hospital for observation and escalation to higher doses or possibly intravenous corticosteroids.

Infliximab has been used in severe and steroid-refractory cases,13 although there has been concern about using anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agents such as this in patients with malignancies, especially melanoma. Since melanoma can be very aggressive and anti-TNF agents may promote it, it is prudent to try not to use this class of agents.

Other biologic agents such as vedolizumab, a gut-specific anti-integrin agent, are safer, have theoretic advantages over anti-TNF agents, and can be considered in patients with steroid-dependent or steroid-refractory ICI-associated enterocolitis. A recent study suggested that 2 to 4 infusions of vedolizumab are adequate to achieve steroid-free remission.15 Results from 6 clinical trials of vedolizumab in 2,830 patients with Crohn disease or ulcerative colitis did not show any increased risk of serious infections or malignancies over placebo.16,17 A drawback is its slow onset of action.

Surgery is an option for patients with severe colitis refractory to intravenous corticosteroids or biological agents, as severe colitis carries a risk of significant morbidity and even death. The incidence of bowel perforation leading to colectomy or death in patients receiving ICI therapy is 0.5% to 1%.18,19

Fecal microbiota transplant was associated with mucosal healing after 1 month in a case report of ICI-associated colitis.9

Follow-up. In most patients, symptoms resolve with discontinuation of the ICI and brief use of corticosteroids or biological agents. Patients with recurrent or persistent symptoms while on long-term ICI therapy may need periodic endoscopic evaluation, especially if there are chronic structural changes on histologic study.

If patients have recurrent or persistent symptoms along with chronic inflammatory structural changes on histology, a sign of an inflammatory bowel diseaselike condition, long-term maintenance therapy with an anti-inflammatory or immunosuppressant agent may be considered. However, there is no consensus on the treatment of this condition. It can be treated in the same way as classic inflammatory bowel disease in the setting of concurrent or prior history of malignancy, especially melanoma. Certain agents used in inflammatory bowel disease such as methotrexate and vedolizumab carry a lower risk of malignancy than anti-TNF agents and can be considered. A multidisciplinary approach that includes an oncologist, gastroenterologist, infectious disease specialist, and colorectal surgeon is imperative.

- Shih K, Arkenau HT, Infante JR. Clinical impact of checkpoint inhibitors as novel cancer therapies. Drugs 2014; 74(17):1993–2013. doi:10.1007/s40265-014-0305-6

- Mellman I, Coukos G, Dranoff G. Cancer immunotherapy comes of age. Nature 2011; 480(7378):480–489. doi:10.1038/nature10673

- Dine J, Gordon R, Shames Y, Kasler MK, Barton-Burke M. Immune checkpoint inhibitors: an innovation in immunotherapy for the treatment and management of patients with cancer. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs 2017; 4(2):127–135. doi:10.4103/apjon.apjon_4_17

- Prieux-Klotz C, Dior M, Damotte D, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced colitis: diagnosis and management. Target Oncol 2017; 12(3):301–308. doi:10.1007/s11523-017-0495-4

- Howell M, Lee R, Bowyer S, Fusi A, Lorigan P. Optimal management of immune-related toxicities associated with checkpoint inhibitors in lung cancer. Lung Cancer 2015; 88(2):117–123. doi:10.1016/j.lungcan.2015.02.007

- Weber JS, Kähler KC, Hauschild A. Management of immune-related adverse events and kinetics of response with ipilimumab. J Clin Oncol 2012; 30(21):2691–2697. doi:10.1200/JCO.2012.41.6750

- Eigentler TK, Hassel JC, Berking C, et al. Diagnosis, monitoring and management of immune-related adverse drug reactions of anti-PD-1 antibody therapy. Cancer Treat Rev 2016; 45:7–18. doi:10.1016/j.ctrv.2016.02.003

- Postow MA, Sidlow R, Hellmann MD. Immune-related adverse events associated with immune checkpoint blockade. N Engl J Med 2018; 378(2):158–168. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1703481

- Wang Y, DuPont H, Jiang ZD, Jenq R, Zuazua R, Shuttlesworth G. Fecal microbiota transplant for immune-checkpoint inhibitor-induced colitis in a 50 year old with bladder cancer. Gastroenterol 2018; 154(1 suppl). doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2017.11.075

- Hodi FS, O’Day SJ, McDermott DF, et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med 2010; 363(8):711–723. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1003466

- Satsangi J, Silverberg MS, Vermeire S, Colombel JF. The Montreal classification of inflammatory bowel disease: controversies, consensus, and implications. Gut 2006; 55(6):749–753. doi:10.1136/gut.2005.082909

- Rastogi P, Sultan M, Charabaty AJ, Atkins MB, Mattar MC. Ipilimumab associated colitis: an IpiColitis case series at MedStar Georgetown University Hospital. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(14):4373–4378. doi:10.3748/wjg.v21.i14.4373

- Pocha C, Roat J, Viskocil K. Immune-mediated colitis: important to recognize and treat. J Crohns Colitis 2014; 8(2):181–182. doi:10.1016/j.crohns.2013.09.019

- Garcia-Neuer M, Marmarelis ME, Jangi SR, et al. Diagnostic comparison of CT scans and colonoscopy for immune-related colitis in ipilimumab-treated advanced melanoma patients. Cancer Immunol Res 2017; 5(4):286–291. doi:10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-16-0302

- Bergqvist V, Hertervig E, Gedeon P, et al. Vedolizumab treatment for immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced enterocolitis. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2017; 66(5):581–592. doi:10.1007/s00262-017-1962-6

- Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Rutgeerts P, et al; GEMINI 2 Study Group. Vedolizumab as induction and maintenance therapy for Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med 2013; 369(8):711–721. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1215739

- Feagan BG, Rutgeerts P, Sands BE, et al; GEMINI 1 Study Group. Vedolizumab as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med 2013; 369(8):699–710. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1215734

- Kähler KC, Hauschild A. Treatment and side effect management of CTLA-4 antibody therapy in metastatic melanoma. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2011; 9(4):277–286. doi:10.1111/j.1610-0387.2010.07568.x

- Ibrahim RA, Berman DM, DePril V, et al. Ipilimumab safety profile: summary of findings from completed trials in advanced melanoma. J Clin Onc 2011; 29(15 suppl):8583–8583. doi:10.1200/jco.2011.29.15_suppl.8583

- Shih K, Arkenau HT, Infante JR. Clinical impact of checkpoint inhibitors as novel cancer therapies. Drugs 2014; 74(17):1993–2013. doi:10.1007/s40265-014-0305-6

- Mellman I, Coukos G, Dranoff G. Cancer immunotherapy comes of age. Nature 2011; 480(7378):480–489. doi:10.1038/nature10673

- Dine J, Gordon R, Shames Y, Kasler MK, Barton-Burke M. Immune checkpoint inhibitors: an innovation in immunotherapy for the treatment and management of patients with cancer. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs 2017; 4(2):127–135. doi:10.4103/apjon.apjon_4_17

- Prieux-Klotz C, Dior M, Damotte D, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced colitis: diagnosis and management. Target Oncol 2017; 12(3):301–308. doi:10.1007/s11523-017-0495-4

- Howell M, Lee R, Bowyer S, Fusi A, Lorigan P. Optimal management of immune-related toxicities associated with checkpoint inhibitors in lung cancer. Lung Cancer 2015; 88(2):117–123. doi:10.1016/j.lungcan.2015.02.007

- Weber JS, Kähler KC, Hauschild A. Management of immune-related adverse events and kinetics of response with ipilimumab. J Clin Oncol 2012; 30(21):2691–2697. doi:10.1200/JCO.2012.41.6750

- Eigentler TK, Hassel JC, Berking C, et al. Diagnosis, monitoring and management of immune-related adverse drug reactions of anti-PD-1 antibody therapy. Cancer Treat Rev 2016; 45:7–18. doi:10.1016/j.ctrv.2016.02.003

- Postow MA, Sidlow R, Hellmann MD. Immune-related adverse events associated with immune checkpoint blockade. N Engl J Med 2018; 378(2):158–168. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1703481

- Wang Y, DuPont H, Jiang ZD, Jenq R, Zuazua R, Shuttlesworth G. Fecal microbiota transplant for immune-checkpoint inhibitor-induced colitis in a 50 year old with bladder cancer. Gastroenterol 2018; 154(1 suppl). doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2017.11.075

- Hodi FS, O’Day SJ, McDermott DF, et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med 2010; 363(8):711–723. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1003466

- Satsangi J, Silverberg MS, Vermeire S, Colombel JF. The Montreal classification of inflammatory bowel disease: controversies, consensus, and implications. Gut 2006; 55(6):749–753. doi:10.1136/gut.2005.082909

- Rastogi P, Sultan M, Charabaty AJ, Atkins MB, Mattar MC. Ipilimumab associated colitis: an IpiColitis case series at MedStar Georgetown University Hospital. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(14):4373–4378. doi:10.3748/wjg.v21.i14.4373

- Pocha C, Roat J, Viskocil K. Immune-mediated colitis: important to recognize and treat. J Crohns Colitis 2014; 8(2):181–182. doi:10.1016/j.crohns.2013.09.019

- Garcia-Neuer M, Marmarelis ME, Jangi SR, et al. Diagnostic comparison of CT scans and colonoscopy for immune-related colitis in ipilimumab-treated advanced melanoma patients. Cancer Immunol Res 2017; 5(4):286–291. doi:10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-16-0302

- Bergqvist V, Hertervig E, Gedeon P, et al. Vedolizumab treatment for immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced enterocolitis. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2017; 66(5):581–592. doi:10.1007/s00262-017-1962-6

- Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Rutgeerts P, et al; GEMINI 2 Study Group. Vedolizumab as induction and maintenance therapy for Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med 2013; 369(8):711–721. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1215739

- Feagan BG, Rutgeerts P, Sands BE, et al; GEMINI 1 Study Group. Vedolizumab as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med 2013; 369(8):699–710. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1215734

- Kähler KC, Hauschild A. Treatment and side effect management of CTLA-4 antibody therapy in metastatic melanoma. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2011; 9(4):277–286. doi:10.1111/j.1610-0387.2010.07568.x

- Ibrahim RA, Berman DM, DePril V, et al. Ipilimumab safety profile: summary of findings from completed trials in advanced melanoma. J Clin Onc 2011; 29(15 suppl):8583–8583. doi:10.1200/jco.2011.29.15_suppl.8583

Which bowel preparation should be used for colonoscopy in patients who have had bariatric surgery?

We routinely use low-volume (2-L) polyethylene glycol electrolyte preparations such as Moviprep and Miralax in split-dose regimens, in which patients drink half of the preparation the day before the procedure and the other half the day of the procedure. In our experience, these are well tolerated by patients with a history of bariatric surgery and provide adequate colon cleansing before colonoscopy.

RATIONALE

Adequate bowel preparation by the ingestion of a cleansing agent is extremely important before colonoscopy: the quality of colon preparation affects the diagnostic accuracy and safety of the procedure, as inadequate bowel preparation has been associated with failure to detect polyps and with a higher rate of adverse events during the procedure.1–3

The most commonly used bowel preparations can be divided into high-volume (which require drinking at least 4 L of a cathartic solution) and low-volume (which require drinking about 2 L).4 Polyethylene glycol electrolyte solutions are among the most commonly used and are available in both high-volume (eg, Golytely, Nulytely) and low-volume (eg, Moviprep, Miralax) forms.

Other low-volume preparations include sodium picosulfate (Prepopik), magnesium citrate, and sodium phosphate tablets. However, these should be avoided in patients with renal insufficiency.4

Prices for bowel preparations vary. For example, the average reported wholesale price of Golytely is $24.56, Moviprep $81.17, and Miralax $10.08.4 However, the final cost depends on the patient’s insurance coverage. Generic formulations are available for some preparations.

After bariatric surgery, patients have a smaller stomach

After bariatric surgery, patients have significantly reduced stomach volume, due either to resection of a part of the stomach (such as in partial gastrectomy) or to diversion of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract to bypass most of the stomach (such as in Roux-en-Y gastric bypass). This causes early satiety with smaller amounts of food and leads to weight loss. However, this restriction in stomach volume also makes it more difficult for the patient to tolerate the intake of large volumes of fluids for bowel cleansing before colonoscopy.

Bariatric surgery patients may require colonoscopy for indications such as colorectal cancer screening, chronic diarrhea, or GI bleeding, all of which are commonly encountered during routine clinical practice.

Guidelines are available

Currently, there are no published data available to support the use of one preparation over another in patients with a history of bariatric surgery. However, for patients who have had bariatric surgery, guidelines from the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer—endorsed by the three major American gastroenterology societies, ie, the American Gastroenterological Association, the American College of Gastroenterology, and the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy—recommend either a low-volume solution or, if a high-volume solution is used, extending the duration over which the preparation is consumed.5 In addition, it is recommended that patients consume sugar-free drinks and liquids to avoid dumping syndrome from high sugar content.6

The use of split-dose regimens is also strongly recommended for elective colonoscopy by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer.5

Our clinical experience has been in line with the above recommendations.

- Chokshi RV, Hovis CE, Hollander T, Early DS, Wang JS. Prevalence of missed adenomas in patients with inadequate bowel preparation on screening colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc 2012; 75:1197–1203.

- Rex DK, Schoenfeld PS, Cohen J, et al. Quality indicators for colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc 2015; 81:31–53.

- Wexner SD, Beck DE, Baron TH, et al; American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons; American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy; Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons. A consensus document on bowel preparation before colonoscopy: prepared by a task force from the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons (ASCRS), the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE), and the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgerons (SAGES). Gastrointest Endosc 2006; 63:894–909.

- ASGE Standards of Practice Committee; Saltzman JR, Cash BD, Pasha SF, et al. Bowel preparation before colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc 2015; 81:781–794.

- Johnson DA, Barkun AN, Cohen LB, et al; US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Optimizing adequacy of bowel cleansing for colonoscopy: recommendations from the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology 2014; 147:903–924.

- Heber D, Greenway FL, Kaplan LM, Livingston E, Salvador J, Still C; Endocrine Society. Endocrine and nutritional management of the post-bariatric surgery patient: an Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2010; 95:4823–4843.

We routinely use low-volume (2-L) polyethylene glycol electrolyte preparations such as Moviprep and Miralax in split-dose regimens, in which patients drink half of the preparation the day before the procedure and the other half the day of the procedure. In our experience, these are well tolerated by patients with a history of bariatric surgery and provide adequate colon cleansing before colonoscopy.

RATIONALE

Adequate bowel preparation by the ingestion of a cleansing agent is extremely important before colonoscopy: the quality of colon preparation affects the diagnostic accuracy and safety of the procedure, as inadequate bowel preparation has been associated with failure to detect polyps and with a higher rate of adverse events during the procedure.1–3

The most commonly used bowel preparations can be divided into high-volume (which require drinking at least 4 L of a cathartic solution) and low-volume (which require drinking about 2 L).4 Polyethylene glycol electrolyte solutions are among the most commonly used and are available in both high-volume (eg, Golytely, Nulytely) and low-volume (eg, Moviprep, Miralax) forms.

Other low-volume preparations include sodium picosulfate (Prepopik), magnesium citrate, and sodium phosphate tablets. However, these should be avoided in patients with renal insufficiency.4

Prices for bowel preparations vary. For example, the average reported wholesale price of Golytely is $24.56, Moviprep $81.17, and Miralax $10.08.4 However, the final cost depends on the patient’s insurance coverage. Generic formulations are available for some preparations.

After bariatric surgery, patients have a smaller stomach

After bariatric surgery, patients have significantly reduced stomach volume, due either to resection of a part of the stomach (such as in partial gastrectomy) or to diversion of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract to bypass most of the stomach (such as in Roux-en-Y gastric bypass). This causes early satiety with smaller amounts of food and leads to weight loss. However, this restriction in stomach volume also makes it more difficult for the patient to tolerate the intake of large volumes of fluids for bowel cleansing before colonoscopy.

Bariatric surgery patients may require colonoscopy for indications such as colorectal cancer screening, chronic diarrhea, or GI bleeding, all of which are commonly encountered during routine clinical practice.

Guidelines are available

Currently, there are no published data available to support the use of one preparation over another in patients with a history of bariatric surgery. However, for patients who have had bariatric surgery, guidelines from the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer—endorsed by the three major American gastroenterology societies, ie, the American Gastroenterological Association, the American College of Gastroenterology, and the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy—recommend either a low-volume solution or, if a high-volume solution is used, extending the duration over which the preparation is consumed.5 In addition, it is recommended that patients consume sugar-free drinks and liquids to avoid dumping syndrome from high sugar content.6

The use of split-dose regimens is also strongly recommended for elective colonoscopy by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer.5

Our clinical experience has been in line with the above recommendations.

We routinely use low-volume (2-L) polyethylene glycol electrolyte preparations such as Moviprep and Miralax in split-dose regimens, in which patients drink half of the preparation the day before the procedure and the other half the day of the procedure. In our experience, these are well tolerated by patients with a history of bariatric surgery and provide adequate colon cleansing before colonoscopy.

RATIONALE

Adequate bowel preparation by the ingestion of a cleansing agent is extremely important before colonoscopy: the quality of colon preparation affects the diagnostic accuracy and safety of the procedure, as inadequate bowel preparation has been associated with failure to detect polyps and with a higher rate of adverse events during the procedure.1–3

The most commonly used bowel preparations can be divided into high-volume (which require drinking at least 4 L of a cathartic solution) and low-volume (which require drinking about 2 L).4 Polyethylene glycol electrolyte solutions are among the most commonly used and are available in both high-volume (eg, Golytely, Nulytely) and low-volume (eg, Moviprep, Miralax) forms.

Other low-volume preparations include sodium picosulfate (Prepopik), magnesium citrate, and sodium phosphate tablets. However, these should be avoided in patients with renal insufficiency.4

Prices for bowel preparations vary. For example, the average reported wholesale price of Golytely is $24.56, Moviprep $81.17, and Miralax $10.08.4 However, the final cost depends on the patient’s insurance coverage. Generic formulations are available for some preparations.

After bariatric surgery, patients have a smaller stomach

After bariatric surgery, patients have significantly reduced stomach volume, due either to resection of a part of the stomach (such as in partial gastrectomy) or to diversion of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract to bypass most of the stomach (such as in Roux-en-Y gastric bypass). This causes early satiety with smaller amounts of food and leads to weight loss. However, this restriction in stomach volume also makes it more difficult for the patient to tolerate the intake of large volumes of fluids for bowel cleansing before colonoscopy.

Bariatric surgery patients may require colonoscopy for indications such as colorectal cancer screening, chronic diarrhea, or GI bleeding, all of which are commonly encountered during routine clinical practice.

Guidelines are available

Currently, there are no published data available to support the use of one preparation over another in patients with a history of bariatric surgery. However, for patients who have had bariatric surgery, guidelines from the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer—endorsed by the three major American gastroenterology societies, ie, the American Gastroenterological Association, the American College of Gastroenterology, and the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy—recommend either a low-volume solution or, if a high-volume solution is used, extending the duration over which the preparation is consumed.5 In addition, it is recommended that patients consume sugar-free drinks and liquids to avoid dumping syndrome from high sugar content.6

The use of split-dose regimens is also strongly recommended for elective colonoscopy by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer.5

Our clinical experience has been in line with the above recommendations.

- Chokshi RV, Hovis CE, Hollander T, Early DS, Wang JS. Prevalence of missed adenomas in patients with inadequate bowel preparation on screening colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc 2012; 75:1197–1203.

- Rex DK, Schoenfeld PS, Cohen J, et al. Quality indicators for colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc 2015; 81:31–53.

- Wexner SD, Beck DE, Baron TH, et al; American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons; American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy; Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons. A consensus document on bowel preparation before colonoscopy: prepared by a task force from the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons (ASCRS), the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE), and the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgerons (SAGES). Gastrointest Endosc 2006; 63:894–909.

- ASGE Standards of Practice Committee; Saltzman JR, Cash BD, Pasha SF, et al. Bowel preparation before colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc 2015; 81:781–794.

- Johnson DA, Barkun AN, Cohen LB, et al; US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Optimizing adequacy of bowel cleansing for colonoscopy: recommendations from the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology 2014; 147:903–924.

- Heber D, Greenway FL, Kaplan LM, Livingston E, Salvador J, Still C; Endocrine Society. Endocrine and nutritional management of the post-bariatric surgery patient: an Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2010; 95:4823–4843.

- Chokshi RV, Hovis CE, Hollander T, Early DS, Wang JS. Prevalence of missed adenomas in patients with inadequate bowel preparation on screening colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc 2012; 75:1197–1203.

- Rex DK, Schoenfeld PS, Cohen J, et al. Quality indicators for colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc 2015; 81:31–53.

- Wexner SD, Beck DE, Baron TH, et al; American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons; American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy; Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons. A consensus document on bowel preparation before colonoscopy: prepared by a task force from the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons (ASCRS), the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE), and the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgerons (SAGES). Gastrointest Endosc 2006; 63:894–909.

- ASGE Standards of Practice Committee; Saltzman JR, Cash BD, Pasha SF, et al. Bowel preparation before colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc 2015; 81:781–794.

- Johnson DA, Barkun AN, Cohen LB, et al; US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Optimizing adequacy of bowel cleansing for colonoscopy: recommendations from the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology 2014; 147:903–924.

- Heber D, Greenway FL, Kaplan LM, Livingston E, Salvador J, Still C; Endocrine Society. Endocrine and nutritional management of the post-bariatric surgery patient: an Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2010; 95:4823–4843.

What are the caveats to using sodium phosphate agents for bowel preparation?

Sodium phosphate (NaP) agents were introduced to provide a gentler alternative to polyethylene glycol (PEG) bowel preparations, which require patients to drink up to 4 liters of fluid over a few hours.

However, in May 2006 the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued an alert that NaP products for bowel cleansing may, in some patients, pose a risk of acute phosphate nephropathy, a rare form of acute renal failure.

Although NaP preparations are generally safe and well tolerated, they can cause significant fluid shifts and electrolyte abnormalities. As such, they should not be used in patients with baseline electrolyte imbalances, renal or hepatic dysfunction, or a number of other comorbidities.

CURRENT BOWEL-CLEANSING OPTIONS

For many years the standard preparation for bowel cleansing was a 4-liter or a 2-liter PEG electrolyte solution plus a laxative (eg, magnesium citrate, bisacodyl, or senna).1–3 The most frequent complaint heard from patients was that “the preparation is worse than the colonoscopy,” attributable to the taste and volume of the fluid they had to consume. Thus, compliance was often a significant issue with patients presenting for colonoscopy. In fact, inadequate bowel preparation is one of the most common reasons polyps are missed during colonoscopy.

Aqueous and tablet forms of NaP (sometimes with a laxative) have become a widely used alternative to PEG solutions because they require much less volume and as a result are more palatable, thereby improving compliance.4,5

NaP agents cleanse the colon by osmotically drawing plasma water into the bowel lumen. The patient must drink significant amounts of water or other oral solutions to prevent dehydration.

NaP-based bowel-cleansing agents are available in two forms: aqueous solution and tablet. Aqueous NaP (such as Fleet Phospho-soda) is a low-volume hyperosmotic solution containing 48 g of monobasic NaP and 18 g of dibasic NaP per 100 mL.6 An oral tablet form (such as Visicol and OsmoPrep) was developed to improve patient tolerance.7 Each 2-g tablet of Visicol contains 1,500 mg of active ingredients (monobasic and dibasic NaP) and 460 mg of microcrystalline cellulose, an inert polymer. Each OsmoPrep tablet contains 1,500 mg of the same active ingredients as Visicol, but the inert ingredients include PEG and magnesium stearate.

At first, the regimen was 40 tablets such as Visicol to be taken with water and bisacodyl. Subsequent regimens such as OsmoPrep with fewer tablets have been shown to be as effective and better tolerated.8 Microcrystalline cellulose in the tablet can produce a residue that may obscure the bowel mucosa. Newer preparations contain lower amounts of this inert ingredient, allowing for improved visualization of the colonic mucosa during colonoscopy.9

ADVANTAGES OF SODIUM PHOSPHATE BOWEL CLEANSERS

In a recent review article, Burke and Church10 noted that NaP cleansing regimens have been shown to be superior to PEG-electrolyte lavage solution with respect to tolerability and acceptance by patients, improved quality of bowel preparation, better mucosal visualization, and more efficient endoscopic examination. In addition, the volume of the preparation may also help decrease the risk of aspiration in some patients.2,3

DISADVANTAGES OF SODIUM PHOSPHATE AGENTS

Despite their comparable or better efficacy and their better tolerability, NaP agents have certain disadvantages.

Effects on the colonic mucosa

In rare cases NaP agents have been shown to alter the microscopic and macroscopic features of the colonic mucosa, and they can induce aphthoid erosions that may mimic those seen in inflammatory bowel disease and enteropathy or colopathy associated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).11–13 Therefore, NaP agents should not be used prior to the initial endoscopic evaluation of patients with suspected inflammatory bowel disease, microscopic colitis, or NSAID-induced colonopathy.

Fluid and electrolyte shifts

Because NaP acts by drawing plasma water into the bowel lumen, significant volume and electrolyte shifts may occur.14,15 These can cause hypokalemia, hyperphosphatemia, hypocalcemia, hyponatremia or hypernatremia, hypomagnesemia, elevated blood urea nitrogen levels, decreased exercise capacity, increased plasma osmolarity,15–17 seizures,18 and acute renal failure with or without nephrocalcinosis.17,19–21

Thus, patients with significant comorbidities—such as a recent history of myocardial infarction, renal or hepatic insufficiency, or malnutrition—should not use NaP agents.22

Pivotal study of adverse events

In May 2006, the FDA issued an alert outlining the concerns of using oral NaP in specific patient populations. Of note were documented cases of acute phosphate nephropathy in 21 patients who used aqueous NaP (Fleet Phospho-Soda or Fleet Accu-Prep), and in 1 patient who used NaP tablets (Visicol).23 Acute renal injury was not limited to patients with preexisting renal insufficiency. It is uncertain whether this means that otherwise healthy people suffered renal injury or had risk factors besides renal insufficiency, since the data cited by the FDA report do not elucidate the possible risk factors for the development of nephropathy in patients with no preexisting renal insufficiency. So far, no cases of acute phosphate nephropathy or acute renal failure have been reported with OsmoPrep, a NaP tablet bowel preparation recently approved by the FDA.24 The long-term safety of OsmoPrep needs further evaluation.

PROCEED WITH CAUTION

Certain situations such as advanced age and cardiac, renal, and hepatic dysfunction call for extreme caution in the use of NaP bowel preparation agents. Therefore, it is recommended that patients with the following conditions should avoid using NaP agents for colon preparation:

- Hepatic or renal insufficiency (there are no data as to the degree of hepatic or renal insufficiency)

- Congestive heart failure

- Over age 65

- Dehydration or hypercalcemia

- Chronic use of drugs that affect renal perfusion, such as NSAIDs, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, or diuretics for hypertension.

Patients who take diuretics should not take them while they are using NaP for bowel preparation because of the risk of electrolyte abnormalities such as hypokalemia. In patients who have no alternative but to proceed with NaP preparation, our recommendation would be that the patient hold off taking diuretics, ACE inhibitors, and angiotensin receptor blockers while using the NaP prep. Given the importance of these medications in controlling diseases such as hypertension, the physician and the patient should jointly determine whether the benefits of using an NaP agent justify holding these drugs. We believe that patients taking these drugs should try using a PEG solution before considering NaP.

TASK FORCE GUIDELINES

Guidelines for using NaP bowel preparation agents, published by a task force of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons, the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, and the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons,25 include the following caveats:

- Aqueous and tablet NaP colonic preparations are an alternative to PEG solutions, except in pediatric populations, patients over age 65, and those with bowel obstruction or other structural intestinal disorder, gut dysmotility, renal or hepatic insufficiency, congestive heart failure, or seizure disorder.

- Dosing should be 45 mL in divided doses, 10 to 12 hours apart, with at least one dose taken on the morning of the procedure.25

- The significant volume contraction and resulting dehydration seen in some patients using NaP preparations may be lessened by encouraging patients to drink fluids liberally during the days leading up to their procedure, and especially during NaP bowel preparation.26

- NaP tablets should be dosed as 32 to 40 tablets. On the evening before the procedure the patient should take 20 tablets and then 12 to 20 tablets approximately 3 to 5 hours before undergoing endoscopy. The tablets should be taken four at a time every 15 minutes with approximately 8 oz of clear liquid.25

- Sharma VK, Chockalingham SK, Ugheoke EA, et al. Prospective, randomized, controlled comparison of the use of polyethylene glycol electrolyte lavage solution in four-liter versus two-liter volumes and pretreatment with either magnesium citrate or bisacodyl for colonoscopy preparation. Gastrointest Endosc 1998; 47:167–171.

- Frommer D. Cleansing ability and tolerance of three bowel preparations for colonoscopy. Dis Colon Rectum 1997; 40:100–104.

- Hsu CW, Imperiale TF. Meta-analysis and cost comparison of polyethylene glycol lavage versus sodium phosphate for colonoscopy preparation. Gastrointest Endosc 1998; 48:276–282.

- Poon CM, Lee DWH, Mak SK, et al. Two liters of polyethylene glycol-electrolyte solution versus sodium phosphate as bowel cleansing regimen for colonoscopy: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Endoscopy 2002; 34:560–563.

- Afridi SA, Barthel JS, King PD, et al. Prospective, randomized trial comparing a new sodium phosphate-bisacodyl regimen with conventional PEG-ES lavage for outpatient colonoscopy preparation. Gastrointest Endosc 1995; 41:485–489.

- Schiller LR. Clinical pharmacology and use of laxatives and lavage solutions. J Clin Gastroenterol 1988; 28:11–18.

- Kastenberg D, Chasen R, Choudhary C, et al. Efficacy and safety of sodium phosphate tablets compared with PEG solution in colon cleansing. Two identically designed, randomized, controlled, parallel group multicenter phase III trials. Gastrointest Endosc 2001; 54:705–713.

- Rex DK, Chasen R, Pushpin MB. Safety and efficacy of two reduced dosing regimens of sodium phosphate tablets for preparation prior to colonoscopy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2002; 16:937–944.

- Rex DK, Khashab M. Efficacy and tolerability of a new formulation of sodium phosphate tablets and a reduced sodium phosphate dose, in colon cleansing: a single-center open-label pilot trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2005; 21:465–468.

- Burke CA, Church JM. Enhancing the quality of colonoscopy: the importance of bowel purgatives. Gastrointest Endosc 2007; 66:565–573.

- Rejchrt S, Bures J, Siroky M, et al. A prospective, observational study of colonic mucosal abnormalities associated with orally administered sodium phosphate for colon cleansing before colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc 2004; 59:651–654.

- Hixson LJ. Colorectal ulcers associated with sodium phosphate catharsis. Gastrointest Endosc 1995; 42:101–102.

- Zwas FR, Cirillo NW, El-Serag HB, Eisen RN. Colonic mucosal abnormalities associated with oral sodium phosphate solution. Gastrointest Endosc 1996; 43:463–466.

- Clarkston WK, Tsen TN, Dies DF, Schratz CL, Vaswani SK, Bjerregaard P. Oral sodium phosphate versus sulfate-free polyethylene glycol electrolyte lavage solution in outpatient preparation for colonoscopy: a prospective comparison. Gastrointest Endosc 1996; 43:42–48.

- Kolts BE, Lyles WE, Achem SR, et al. A comparison of the effectiveness and patient tolerance of oral sodium phosphate, castor oil, and standard electrolyte lavage for colonoscopy or sigmoidoscopy preparations. Am J Gastroenterol 1993; 88:1218–1223.

- Holte K, Neilsen KG, Madsen JL, Kehlet H. Physiologic effects of bowel preparation. Dis Colon Rectum 2004; 47:1397–1402.

- Clarkston WK, Tsen TN, Dies DF, et al. Oral sodium phosphate versus sulfate-free polyethylene glycol electrolyte lavage solution in outpatient preparation for colonoscopy: a prospective comparison. Gastrointest Endosc 1996; 43:42–48.

- Frizelle FA, Colls BM. Hyponatremia and seizures after bowel preparation: report of three cases. Dis Colon Rectum 2005; 48:393–396.

- Markowitz GS, Nasr SH, Klein P, et al. Renal failure due to acute nephrocalcinosis following oral sodium phosphate bowel cleansing. Hum Pathol 2004; 35:675–684.

- Lieberman DA, Ghormley J, Flora K. Effect of oral sodium phosphate colon preparation on serum electrolytes in patients with normal serum creatinine. Gastrointest Endosc 1996; 43:467–469.

- Gremse DA, Sacks AI, Raines S. Comparison of oral sodium phosphate to polyethylene-glycol-based solution for bowel preparation in children. J Pediatric Gastroenterol Nutr 1996; 23:586–590.

- Curran MP, Plosker GL. Oral sodium phosphate solution: a review of its use as a colonic cleanser. Drugs 2004; 64:1697–1714.

- Markowitz GS, Stokes MB, Radhakrishnan J, D’Agati VD. Acute phosphate nephropathy following oral sodium phosphate bowel purgative: an underrecognized cause of chronic renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol 2005; 16:3389–3396.

- FDA Alert. Patient information sheet. Oral sodium phosphate (OSP) products for bowel cleansing. 2006 May, Accessed January 8, 2008. www.fda.gov/CDER/drug/InfoSheets/patient/OSP_solutionPIS.htm.

- Wexner SD, Beck DE, Baron TH, et al. A consensus document on bowel preparation before colonoscopy prepared by a task force from the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons (ASCRS), the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE), and the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES). Gastrointest Endosc 2006; 63:894–909.

- Huynh T, Vanner S, Paterson W. Safety profile of 5-h oral sodium phosphate regimen for colonoscopy cleansing: lack of clinically significant hypocalcemia or hypovolemia. Am J Gastroenterol 1995; 90:104–107.

Sodium phosphate (NaP) agents were introduced to provide a gentler alternative to polyethylene glycol (PEG) bowel preparations, which require patients to drink up to 4 liters of fluid over a few hours.

However, in May 2006 the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued an alert that NaP products for bowel cleansing may, in some patients, pose a risk of acute phosphate nephropathy, a rare form of acute renal failure.

Although NaP preparations are generally safe and well tolerated, they can cause significant fluid shifts and electrolyte abnormalities. As such, they should not be used in patients with baseline electrolyte imbalances, renal or hepatic dysfunction, or a number of other comorbidities.

CURRENT BOWEL-CLEANSING OPTIONS

For many years the standard preparation for bowel cleansing was a 4-liter or a 2-liter PEG electrolyte solution plus a laxative (eg, magnesium citrate, bisacodyl, or senna).1–3 The most frequent complaint heard from patients was that “the preparation is worse than the colonoscopy,” attributable to the taste and volume of the fluid they had to consume. Thus, compliance was often a significant issue with patients presenting for colonoscopy. In fact, inadequate bowel preparation is one of the most common reasons polyps are missed during colonoscopy.

Aqueous and tablet forms of NaP (sometimes with a laxative) have become a widely used alternative to PEG solutions because they require much less volume and as a result are more palatable, thereby improving compliance.4,5

NaP agents cleanse the colon by osmotically drawing plasma water into the bowel lumen. The patient must drink significant amounts of water or other oral solutions to prevent dehydration.

NaP-based bowel-cleansing agents are available in two forms: aqueous solution and tablet. Aqueous NaP (such as Fleet Phospho-soda) is a low-volume hyperosmotic solution containing 48 g of monobasic NaP and 18 g of dibasic NaP per 100 mL.6 An oral tablet form (such as Visicol and OsmoPrep) was developed to improve patient tolerance.7 Each 2-g tablet of Visicol contains 1,500 mg of active ingredients (monobasic and dibasic NaP) and 460 mg of microcrystalline cellulose, an inert polymer. Each OsmoPrep tablet contains 1,500 mg of the same active ingredients as Visicol, but the inert ingredients include PEG and magnesium stearate.

At first, the regimen was 40 tablets such as Visicol to be taken with water and bisacodyl. Subsequent regimens such as OsmoPrep with fewer tablets have been shown to be as effective and better tolerated.8 Microcrystalline cellulose in the tablet can produce a residue that may obscure the bowel mucosa. Newer preparations contain lower amounts of this inert ingredient, allowing for improved visualization of the colonic mucosa during colonoscopy.9

ADVANTAGES OF SODIUM PHOSPHATE BOWEL CLEANSERS

In a recent review article, Burke and Church10 noted that NaP cleansing regimens have been shown to be superior to PEG-electrolyte lavage solution with respect to tolerability and acceptance by patients, improved quality of bowel preparation, better mucosal visualization, and more efficient endoscopic examination. In addition, the volume of the preparation may also help decrease the risk of aspiration in some patients.2,3

DISADVANTAGES OF SODIUM PHOSPHATE AGENTS

Despite their comparable or better efficacy and their better tolerability, NaP agents have certain disadvantages.

Effects on the colonic mucosa

In rare cases NaP agents have been shown to alter the microscopic and macroscopic features of the colonic mucosa, and they can induce aphthoid erosions that may mimic those seen in inflammatory bowel disease and enteropathy or colopathy associated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).11–13 Therefore, NaP agents should not be used prior to the initial endoscopic evaluation of patients with suspected inflammatory bowel disease, microscopic colitis, or NSAID-induced colonopathy.

Fluid and electrolyte shifts

Because NaP acts by drawing plasma water into the bowel lumen, significant volume and electrolyte shifts may occur.14,15 These can cause hypokalemia, hyperphosphatemia, hypocalcemia, hyponatremia or hypernatremia, hypomagnesemia, elevated blood urea nitrogen levels, decreased exercise capacity, increased plasma osmolarity,15–17 seizures,18 and acute renal failure with or without nephrocalcinosis.17,19–21

Thus, patients with significant comorbidities—such as a recent history of myocardial infarction, renal or hepatic insufficiency, or malnutrition—should not use NaP agents.22

Pivotal study of adverse events

In May 2006, the FDA issued an alert outlining the concerns of using oral NaP in specific patient populations. Of note were documented cases of acute phosphate nephropathy in 21 patients who used aqueous NaP (Fleet Phospho-Soda or Fleet Accu-Prep), and in 1 patient who used NaP tablets (Visicol).23 Acute renal injury was not limited to patients with preexisting renal insufficiency. It is uncertain whether this means that otherwise healthy people suffered renal injury or had risk factors besides renal insufficiency, since the data cited by the FDA report do not elucidate the possible risk factors for the development of nephropathy in patients with no preexisting renal insufficiency. So far, no cases of acute phosphate nephropathy or acute renal failure have been reported with OsmoPrep, a NaP tablet bowel preparation recently approved by the FDA.24 The long-term safety of OsmoPrep needs further evaluation.

PROCEED WITH CAUTION

Certain situations such as advanced age and cardiac, renal, and hepatic dysfunction call for extreme caution in the use of NaP bowel preparation agents. Therefore, it is recommended that patients with the following conditions should avoid using NaP agents for colon preparation:

- Hepatic or renal insufficiency (there are no data as to the degree of hepatic or renal insufficiency)

- Congestive heart failure

- Over age 65

- Dehydration or hypercalcemia

- Chronic use of drugs that affect renal perfusion, such as NSAIDs, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, or diuretics for hypertension.

Patients who take diuretics should not take them while they are using NaP for bowel preparation because of the risk of electrolyte abnormalities such as hypokalemia. In patients who have no alternative but to proceed with NaP preparation, our recommendation would be that the patient hold off taking diuretics, ACE inhibitors, and angiotensin receptor blockers while using the NaP prep. Given the importance of these medications in controlling diseases such as hypertension, the physician and the patient should jointly determine whether the benefits of using an NaP agent justify holding these drugs. We believe that patients taking these drugs should try using a PEG solution before considering NaP.

TASK FORCE GUIDELINES

Guidelines for using NaP bowel preparation agents, published by a task force of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons, the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, and the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons,25 include the following caveats:

- Aqueous and tablet NaP colonic preparations are an alternative to PEG solutions, except in pediatric populations, patients over age 65, and those with bowel obstruction or other structural intestinal disorder, gut dysmotility, renal or hepatic insufficiency, congestive heart failure, or seizure disorder.

- Dosing should be 45 mL in divided doses, 10 to 12 hours apart, with at least one dose taken on the morning of the procedure.25

- The significant volume contraction and resulting dehydration seen in some patients using NaP preparations may be lessened by encouraging patients to drink fluids liberally during the days leading up to their procedure, and especially during NaP bowel preparation.26

- NaP tablets should be dosed as 32 to 40 tablets. On the evening before the procedure the patient should take 20 tablets and then 12 to 20 tablets approximately 3 to 5 hours before undergoing endoscopy. The tablets should be taken four at a time every 15 minutes with approximately 8 oz of clear liquid.25

Sodium phosphate (NaP) agents were introduced to provide a gentler alternative to polyethylene glycol (PEG) bowel preparations, which require patients to drink up to 4 liters of fluid over a few hours.

However, in May 2006 the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued an alert that NaP products for bowel cleansing may, in some patients, pose a risk of acute phosphate nephropathy, a rare form of acute renal failure.

Although NaP preparations are generally safe and well tolerated, they can cause significant fluid shifts and electrolyte abnormalities. As such, they should not be used in patients with baseline electrolyte imbalances, renal or hepatic dysfunction, or a number of other comorbidities.

CURRENT BOWEL-CLEANSING OPTIONS

For many years the standard preparation for bowel cleansing was a 4-liter or a 2-liter PEG electrolyte solution plus a laxative (eg, magnesium citrate, bisacodyl, or senna).1–3 The most frequent complaint heard from patients was that “the preparation is worse than the colonoscopy,” attributable to the taste and volume of the fluid they had to consume. Thus, compliance was often a significant issue with patients presenting for colonoscopy. In fact, inadequate bowel preparation is one of the most common reasons polyps are missed during colonoscopy.

Aqueous and tablet forms of NaP (sometimes with a laxative) have become a widely used alternative to PEG solutions because they require much less volume and as a result are more palatable, thereby improving compliance.4,5

NaP agents cleanse the colon by osmotically drawing plasma water into the bowel lumen. The patient must drink significant amounts of water or other oral solutions to prevent dehydration.