User login

Timing of Adverse Events Following Geriatric Hip Fracture Surgery: A Study of 19,873 Patients in the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program

ABSTRACT

This study uses a prospective surgical registry to characterize the timing of 10 postoperative adverse events following geriatric hip fracture surgery. There were 19,873 patients identified who were ≥70 years undergoing surgery for hip fracture as part of the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS-NSQIP). The median postoperative day of diagnosis (and interquartile range) for myocardial infarction was 3 (1-5), cardiac arrest requiring cardiopulmonary resuscitation 3 (0-8), stroke 3 (1-10), pneumonia 4 (2-10), pulmonary embolism 4 (2-11), urinary tract infection 7 (2-13), deep vein thrombosis 9 (4-16), sepsis 9 (4-18), mortality 11 (6-19), and surgical site infection 16 (11-22). For the earliest diagnosed adverse events, the rate of adverse events had diminished by postoperative day 30. For the later diagnosed adverse events, the rate of adverse events remained high at postoperative day 30. Findings help to enable more targeted clinical surveillance, inform patient counseling, and determine the duration of follow-up required to study specific adverse events effectively. Orthopedic surgeons should have the lowest threshold for testing for each adverse event during the time period of greatest risk.

Continue to: Geriatric hip fracture surgery is associated with...

Geriatric hip fracture surgery is associated with a higher rate of occurrence of postoperative adverse events than any other commonly performed orthopedic procedure.1-4 Indeed, the 90-day mortality rate following a geriatric hip fracture surgery may be as high as 15%2 and the 30-day morbidity rate as high as 30%.3 Furthermore, more than half of postoperative mortalities following orthopedic procedures occur after surgery for hip fracture.4 Therefore, extensive research has been conducted regarding interventions to reduce the rates of adverse events following a hip fracture surgery.5-12 For example, randomized trials have been conducted involving venous thromboembolism prophylaxis,5,6nutritional supplementation,7 delirium prevention,8-10 anemia correction,11 geriatrics consultation,9 and anesthetic technique.12

Despite these extensive research efforts, there is currently little information in the literature regarding when postoperative adverse events occur. A clear depiction of the timing of adverse events could help target clinical surveillance, inform patient counseling, and determine the duration of follow-up required for studies. The reason that the timing of adverse events has not been previously characterized may be that the sample sizes available through standard single- or multi-institutional studies may be insufficient to accurately characterize the timing of rare adverse events (eg, myocardial infarction, stroke, etc.). Moreover, although administrative datasets have become common data sources for investigation of rare postoperative adverse events,13-16 such data sources often do not contain data on the timing of diagnosis.

The American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS-NSQIP) is a relatively new and growing surgical registry.1,3,13-22 The registry follows up patients undergoing surgical procedures at several hundred community and academic institutions nationwide. Unlike the administrative datasets discussed above, the ACS-NSQIP characterizes the postoperative day of diagnosis of well-defined adverse events during the first 30 postoperative days.22

In this study, data collected by the ACS-NSQIP are used to characterize the timing of 10 specific postoperative adverse events following a geriatric hip fracture surgery.

Continue to: METHODS...

METHODS

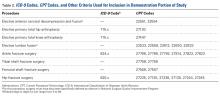

A retrospective analysis of data collected prospectively through the ACS-NSQIP was conducted. Geriatric patients who underwent hip fracture surgery during 2010 to 2013 were identified. Specific inclusion criteria were (1) International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, diagnosis code 820, (2) primary Current Procedural Terminology codes 27125, 27130, 27235, 27236, 27244, or 27245, and (3) age ≥70 years.

The ACS-NSQIP captures patient demographic, comorbidity, and procedural characteristics at baseline.22 At the end of the 30-day follow-up period, the ACS-NSQIP personnel review both inpatient and outpatient charts to characterize the occurrence vs nonoccurrence of specific postoperative adverse events.22-25 When an adverse event does occur, the postoperative day of diagnosis is recorded.

For this study, the following adverse event categories were investigated: myocardial infarction, cardiac arrest requiring cardiopulmonary resuscitation, stroke, pneumonia, pulmonary embolism, urinary tract infection, deep vein thrombosis, sepsis (either with or without shock), mortality, and surgical site infection (including superficial surgical site infection, deep surgical site infection, and organ or space surgical site infection). Detailed definitions of each adverse event are provided in ACS-NSQIP materials.22

First, the 30-day incidence (and the associated 95% confidence interval) was determined for each adverse event. Second, the median postoperative day of diagnosis (and the associated interquartile range) was determined for each adverse event. Third, the postoperative length of stay was used to estimate the proportion of diagnoses occurring prior to vs following discharge for each adverse event. Finally, multivariate Cox proportional hazards models were used to identify independent risk factors for earlier occurrence of postoperative adverse events. The final models were selected using a backward stepwise process that sequentially eliminated variables with the weakest associations until all variables had P < .05.

Because the ACS-NSQIP reports timing data in calendar days, when the postoperative length of stay was equivalent to the postoperative day of diagnosis, it was not possible to ascertain whether the diagnosis occurred prior to or following discharge. For this study, when the postoperative length of stay was equivalent to the postoperative day of diagnosis, the adverse event was considered to have been diagnosed following discharge. The rationale for this is that for most of the adverse events, it was thought to be unlikely that an inpatient would be discharged before the end of the same day as an inpatient diagnosis. However, there was one exception to this rule; when the postoperative day of discharge, the postoperative length of stay, and the postoperative day of death were all equivalent, the adverse event was considered to have occurred prior to discharge. This is because when a patient dies during the initial inpatient stay, the ACS-NSQIP considers the postoperative length of stay to be equivalent to the postoperative day of death. This makes it much more likely that a diagnosis on the final hospital day had occurred in a patient who had not been discharged.

The mandatory ACS-NSQIP statement is “The American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program and the hospitals participating in the ACS-NSQIP are the source of the data used herein; they have not verified and are not responsible for the statistical validity of the data analysis or the conclusions derived by the authors.”26

Continue to: RESULTS...

RESULTS

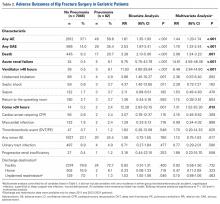

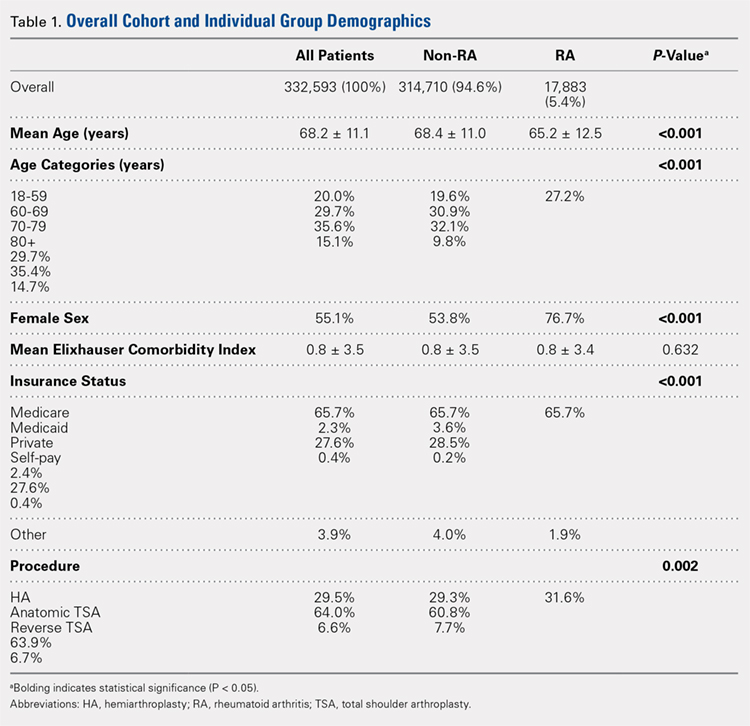

In total, 19,873 geriatric patients undergoing a hip fracture surgery were identified (Table 1). The rates of adverse events ranged from 6.7% for urinary tract infection to 0.6% for pulmonary embolism (Table 2).

Table 1. Patient Population

| Number | Percent |

Total | 19,873 | 100.0% |

Age |

|

|

70-74 years | 1852 | 9.3% |

75-79 years | 2764 | 13.9% |

80-84 years | 4328 | 21.8% |

85-89 years | 5525 | 27.8% |

≥90 years | 5404 | 27.2% |

Sex |

|

|

Male | 5359 | 27.0% |

Female | 14,514 | 73.0% |

Body mass index |

|

|

<30 kg/m2 | 17,733 | 89.2% |

≥30 kg/m2 | 2140 | 10.8% |

Functional status |

|

|

Independent | 14,348 | 72.2% |

Dependent | 5525 | 27.8% |

Diabetes | 3321 | 16.7% |

Congestive heart failure | 738 | 3.7% |

Dyspnea on exertion | 1542 | 7.8% |

Hypertension | 14,265 | 71.8% |

End-stage renal disease | 322 | 1.6% |

COPD | 2239 | 11.3% |

Current smoker | 1506 | 7.6% |

Abbreviation: COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Table 2. Patients with Adverse Events Diagnosed During the First 30 postoperative days (N = 19,873)

Adverse Event | Number | Percent | 95% CI |

Urinary tract infection | 1321 | 6.7% | 6.3%-7.0% |

Mortality | 1240 | 6.2% | 5.9%-6.6% |

Pneumonia | 771 | 3.9% | 3.6%-4.2% |

Sepsis | 428 | 2.2% | 2.0%-2.4% |

Myocardial infarction | 347 | 1.8% | 1.6%-1.9% |

Surgical site infection | 247 | 1.2% | 1.1%-1.4% |

Deep vein thrombosis | 199 | 1.0% | 0.9%-1.1% |

Stroke | 144 | 0.7% | 0.6%-0.8% |

Cardiac arrest | 136 | 0.7% | 0.6%-0.8% |

Pulmonary embolism | 126 | 0.6% | 0.5%-0.7% |

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

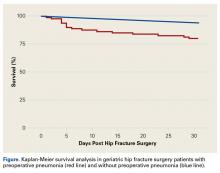

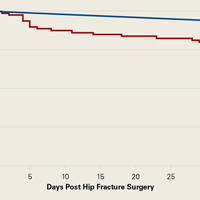

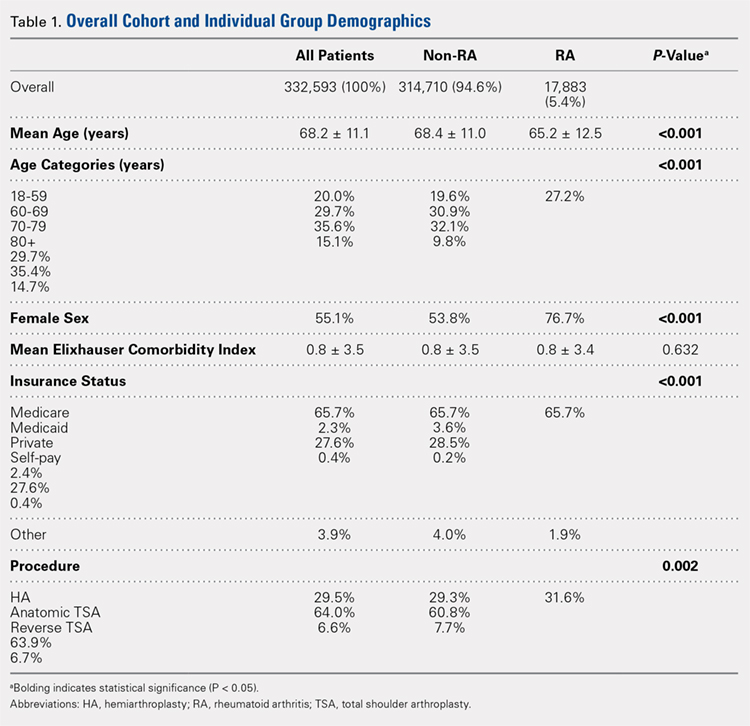

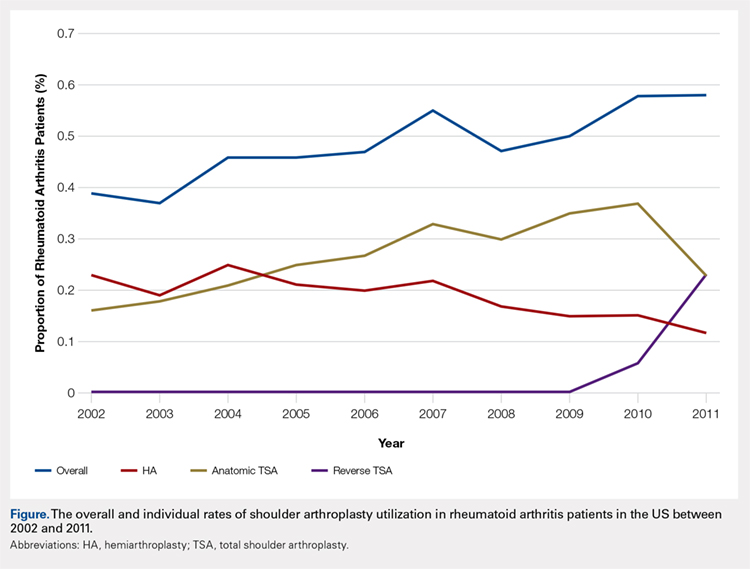

Figure 1 depicts the timing of postoperative adverse events in detail in histograms and timing curves. For the earliest diagnosed adverse events, the rate of adverse events had diminished by postoperative day 30. For the later diagnosed adverse events, the rate of adverse events remained high at postoperative day 30.

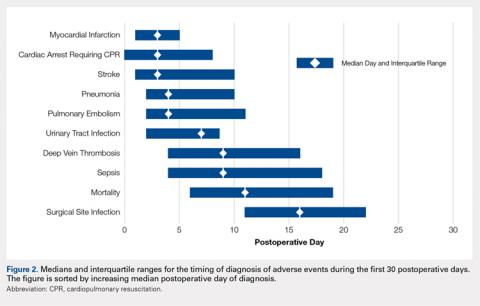

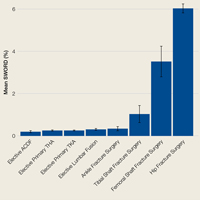

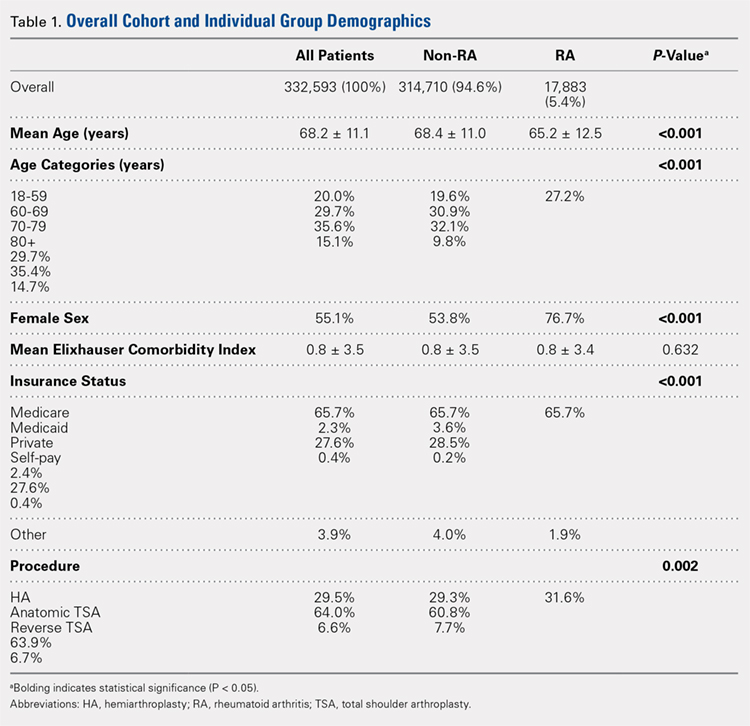

Figure 2 provides the summary statistics for adverse events diagnosed in the first 30 postoperative days. The median postoperative day of diagnosis (and the interquartile range) was 3 (1-5) for myocardial infarction, 3 (0-8) for cardiac arrest requiring cardiopulmonary resuscitation, 3 (1-10) for stroke, 4 (2-10) for pneumonia, 4 (2-11) for pulmonary embolism, 7 (2-13) for urinary tract infection, 9 (4-16) for deep vein thrombosis, 9 (4-18) for sepsis, 11 (6-19) for mortality, and 16 (11-22) for surgical site infection.

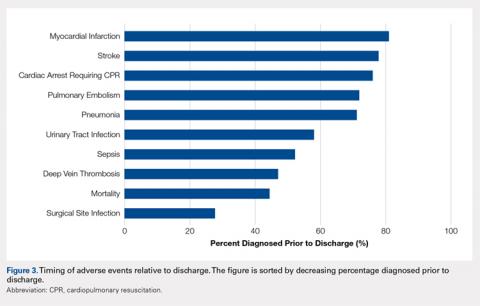

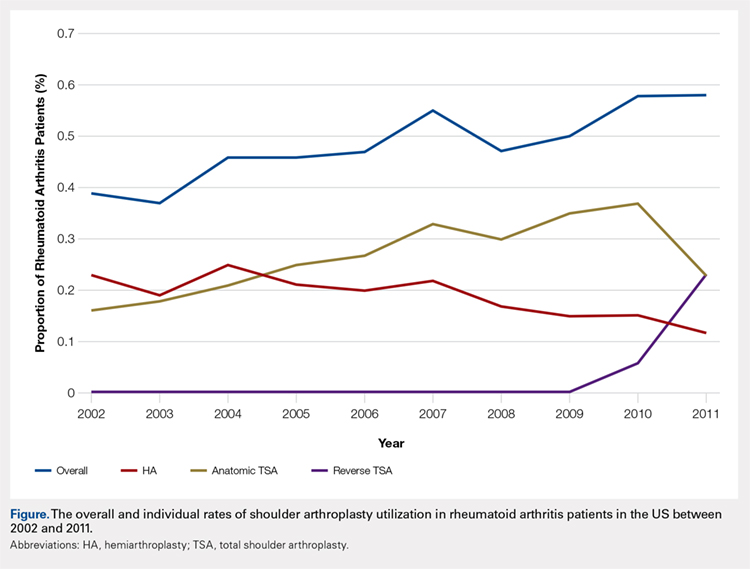

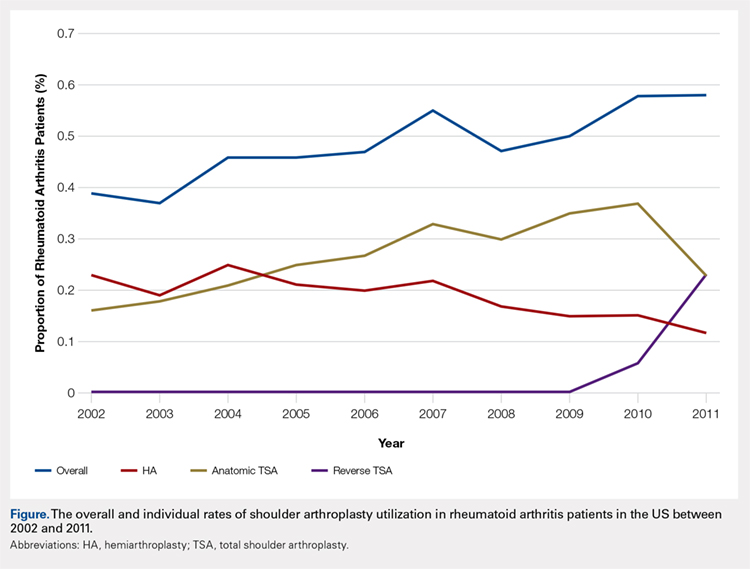

Figure 3 depicts the timing of adverse events relative to discharge. The proportions of adverse events diagnosed prior to discharge were 81.0% for myocardial infarction, 77.8% for stroke, 76.1% for cardiac arrest requiring cardiopulmonary resuscitation, 71.9% for pulmonary embolism, 71.1% for pneumonia, 58.0% for urinary tract infection, 52.1% for sepsis, 46.9% for deep vein thrombosis, 44.3% for mortality, and 27.6% for surgical site infection.

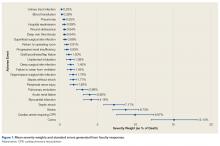

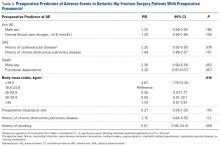

Table 3 shows the independent risk factors for earlier occurrence of adverse events. Following multivariate stepwise selection of final models, at least 1 patient characteristic was independently associated with the timing of cardiac arrest, stroke, urinary tract infection, deep vein thrombosis, and death. In contrast, no patient characteristics were independently associated with the timing of myocardial infarction, pneumonia, pulmonary embolism, sepsis, and surgical site infection.

Table 3. Timing of Diagnosis of Adverse Eventsa

Adverse events and associated baseline characteristic(s) | Median postoperative day of diagnosis with vs without baseline characteristic | P-valueb |

Cardiac arrest |

|

|

End-stage renal disease | 1 vs 3 | .005 |

Stroke |

|

|

Hypertension | 4 vs 2 | .025 |

Dependent functional status | 2 vs 4 | .027 |

Urinary tract infection |

|

|

Female sex | 6 vs 8 | .009 |

Deep vein thrombosis |

|

|

Body mass index ≥30 kg/m2 | 5 vs 10 | .015 |

Death |

|

|

End-stage renal disease | 10 vs 11 | .031 |

aBaseline characteristics that were independently associated with the timing of each adverse event were identified through a backwards stepwise selection process initially including all characteristics listed in Table 1, and sequentially excluding characteristics with the weakest associations until only characteristics with P < .05 remained. Independent associations with the timing of cardiac arrest, stroke, urinary tract infection, deep vein thrombosis, and death are shown. There were no characteristics independently associated with timing of myocardial infarction, pneumonia, pulmonary embolism, sepsis, or surgical site infection; hence, these adverse events are not listed in the table.

bFrom final Cox proportional hazards models identified through multivariate stepwise selection.

Continue to: DISCUSSION...

DISCUSSION

Adverse events are extremely common following a geriatric hip fracture surgery.1-4 Despite extensive investigation regarding methods to prevent these events,5-12 there is limited published description of the timing at which such events occur. This study used a large prospectively followed up cohort of geriatric patients undergoing a hip fracture surgery to deliver a better description of the timing of adverse events than was previously available. The findings of this study should enable more targeted clinical surveillance, inform patient counseling, and help determine the duration of follow-up required for studies on adverse events.

There was wide variability in the timing at which the different postoperative adverse events were diagnosed (Figures 1, 2). Myocardial infarction was diagnosed the earliest, with more than three-fourth of diagnoses in the first postoperative week. Other relatively early-diagnosed adverse events included cardiac arrest requiring cardiopulmonary resuscitation, stroke, pneumonia, and pulmonary embolism.

The latest-diagnosed adverse event was surgical site infection (Figures 1, 2). Surgical site infection was actually the only adverse event with a rate of diagnosis during the first week that was lower than the rate of diagnosis later in the month (as can be seen by the inflection in the timing curve for surgical site infection in Figure 1). Mortality showed a relatively consistent rate of diagnosis throughout the entire first postoperative month. Other relatively late-diagnosed postoperative events, including sepsis, deep vein thrombosis, and urinary tract infection, showed varying degrees of decreased rate of diagnosis near the end of the first postoperative month. Of note, for the later-diagnosed adverse events, the estimated median and interquartile ranges (Figure 2) were presumably quite biased toward earlier diagnosis, as the 30-day follow-up period clearly failed to capture a large proportion of later-occurring adverse events (Figure 1).

Certain risk factors were independently associated with earlier occurrence of adverse events. Perhaps most strikingly, body mass index in the obese range was associated with substantially earlier occurrence of deep vein thrombosis (median of 5 vs 10 days). This finding suggests that clinical monitoring for deep vein thrombosis should be performed earlier in patients with greater body mass index. Also notable is the earlier occurrence of cardiac arrest and death among patients with end-stage renal disease than among those without. Patients with end-stage renal disease may have a greater risk for these adverse events immediately following the cardiac stresses of surgery.27 Similarly, such patients may be more prone to early electrolyte abnormalities and arrhythmia.

Continue to: In addition to its clinical implications, this study...

In addition to its clinical implications, this study informs about the interpretation of the many studies of adverse events following hip fracture procedures that have been conducted using retrospective data. Several such studies have relied on inpatient-only administrative databases.4,13,14,28-35 As clearly demonstrated in Figure 3, for most of the commonly studied adverse events, inpatient-only databases failed to capture a large proportion of adverse events occurring in the first postoperative month. This highlights a substantial limitation of this commonly published type of study that is often not emphasized in the literature.

There has also been an increase in the publication of studies of adverse events following a hip fracture surgery using the ACS-NSQIP data.3,13,14,17,18,21 As discussed, the ACS-NSQIP provides data on 30-days of follow-up. This relatively extended follow-up is often touted as a distinct advantage. However, this study demonstrates that even the 30-day follow-up afforded by the ACS-NSQIP is limited in its ability to enable investigation of the later-occurring adverse events (Figure 1). In particular, the rate of surgical site infection shows little sign of slowing by postoperative day 30. Similarly, the rates of mortality, sepsis, deep vein thrombosis, and urinary tract infection remain substantial.

This study does have limitations. First, as discussed, the duration of follow-up is a limitation of any ACS-NSQIP-based investigation, including this study. Second, the ACS-NSQIP does not capture relevant orthopedic-specific outcomes (eg, screw cutout). In addition, it could not be determined with certainty whether adverse events occurring on the final hospital day occurred prior to or following discharge. However, only a small proportion of most of the adverse events was diagnosed on the final hospital day. Finally, the ACS-NSQIP reports on days from the operation until diagnosis of the adverse event. Although some adverse events are probably diagnosed quickly after they have occurred (eg, myocardial infarction and cardiac arrest), other adverse events may have a delayed diagnosis (eg, surgical site infection may be identified days after its initial occurrence during a follow-up examination). Therefore, it is important to note the subtle distinction between occurrence and diagnosis throughout the article. This article reports on the timing of diagnosis, not actual occurrence.

CONCLUSION

The timing of postoperative adverse events has been understudied in the past. This may be due to an inability of standard single- or multi-institutional investigations to achieve sample sizes adequate to study the less commonly occurring adverse events. Using a relatively new prospective surgical registry, this study provides a far more detailed description of the timing of adverse events following surgery than was previously available. The authors anticipate that these data can be used to inform patient counseling, target clinical surveillance, and direct clinical research. The authors chose to study the timing of postoperative adverse events following geriatric hip fracture surgery because of the high rate of adverse events associated with the procedure. However, future ACS-NSQIP studies may involve characterization of the timing of adverse events following other orthopedic and non-orthopedic procedures.

This paper will be judged for the Resident Writer’s Award.

1. Schilling PL, Hallstrom BR, Birkmeyer JD, Carpenter JE. Prioritizing perioperative quality improvement in orthopaedic surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(9):1884-1889. doi:10.2106/jbjs.i.00735.

2. Forte ML, Virnig BA, Swiontkowski MF, et al. Ninety-day mortality after intertrochanteric hip fracture: does provider volume matter? J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(4):799-806. doi:10.2106/jbjs.h.01204.

3. Pugely AJ, Martin CT, Gao Y, Klocke NF, Callaghan JJ, Marsh JL. A risk calculator for short-term morbidity and mortality after hip fracture surgery. J Orthop Trauma.2014;28(2):63-69. doi:10.1097/BOT.0b013e3182a22744.

4. Bhattacharyya T, Iorio R, Healy WL. Rate of and risk factors for acute inpatient mortality after orthopaedic surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84-a(4):562-572.

5. Eriksson BI, Lassen MR. Duration of prophylaxis against venous thromboembolism with fondaparinux after hip fracture surgery: a multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(11):1337-1342. doi:10.1001/archinte.163.11.1337.

6. Handoll HH, Farrar MJ, McBirnie J, Tytherleigh-Strong G, Milne AA, Gillespie WJ. Heparin, low molecular weight heparin and physical methods for preventing deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism following surgery for hip fractures. Cochrane Database Syst Rev.2002;(4):Cd000305. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd000305.

7. Avenell A, Handoll HH. Nutritional supplementation for hip fracture aftercare in the elderly. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(1):Cd001880. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001880.pub2.

8. Marcantonio ER, Flacker JM, Wright RJ, Resnick NM. Reducing delirium after hip fracture: a randomized trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49(5):516-522. doi:10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49108.x.

9. Deschodt M, Braes T, Flamaing J, et al. Preventing delirium in older adults with recent hip fracture through multidisciplinary geriatric consultation. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(4):733-739. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03899.x.

10. Marcantonio ER, Palihnich K, Appleton P, Davis RB. Pilot randomized trial of donepezil hydrochloride for delirium after hip fracture. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59 Suppl 2:S282-S288. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03691.x.

11. Parker MJ. Iron supplementation for anemia after hip fracture surgery: a randomized trial of 300 patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(2):265-269. doi:10.2106/jbjs.i.00883.

12. Urwin SC, Parker MJ, Griffiths R. General versus regional anaesthesia for hip fracture surgery: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Br J Anaesth. 2000;84(4):450-455. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.bja.a013468.

13. Bohl DD, Basques BA, Golinvaux NS, Baumgaertner MR, Grauer JN. Nationwide Inpatient Sample and National Surgical Quality Improvement Program give different results in hip fracture studies. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(6):1672-1680. doi:10.1007/s11999-014-3559-0.

14. Bohl DD, Grauer JN, Leopold SS. Editor's spotlight/Take 5: nationwide inpatient sample and national surgical quality improvement program give different results in hip fracture studies. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(6):1667-1671. doi:10.1007/s11999-014-3595-9.

15. Bohl DD, Russo GS, Basques BA, et al. Variations in data collection methods between national databases affect study results: a comparison of the nationwide inpatient sample and national surgical quality improvement program databases for lumbar spine fusion procedures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(23):e193. doi:10.2106/jbjs.m.01490.

16. Levin PE. Apples, oranges, and national databases: commentary on an article by Daniel D. Bohl, MPH, et al.: "Variations in data collection methods between national databases affect study results: a comparison of the nationwide inpatient sample and national surgical quality improvement program databases for lumbar spine fusion procedures.” J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(23):e198. doi:10.2106/jbjs.n.00890.

17. Basques BA, Bohl DD, Golinvaux NS, Leslie MP, Baumgaertner MR, Grauer JN. Postoperative length of stay and thirty-day readmission following geriatric hip fracture: an analysis of 8,434 patients. J Orthop Trauma. 2015;29(3):e115-e120. doi:10.1097/bot.0000000000000222.

18. Golinvaux NS, Bohl DD, Basques BA, Baumgaertner MR, Grauer JN. Diabetes confers little to no increased risk of postoperative complications after hip fracture surgery in geriatric patients. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(3):1043-1051. doi:10.1007/s11999-014-3945-7.

19. Maciejewski ML, Radcliff TA, Henderson WG, et al. Determinants of postsurgical discharge setting for male hip fracture patients. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2013;50(9):1267-1276. doi:10.1682/jrrd.2013.02.0041.

20. Molina CS, Thakore RV, Blumer A, Obremskey WT, Sethi MK. Use of the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program in orthopaedic surgery. Clin Orthop Relat Res.2015;473(5):1574-1581. doi:10.1007/s11999-014-3597-7.

21. Bohl DD, Basques BA, Golinvaux NS, Miller CP, Baumgaertner MR, Grauer JN. Extramedullary compared with intramedullary implants for intertrochanteric hip fractures: thirty-day outcomes of 4432 procedures from the ACS NSQIP database. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(22):1871-1877. doi:10.2106/jbjs.n.00041.

22. Alosh H, Riley LH 3rd, Skolasky RL. Insurance status, geography, race, and ethnicity as predictors of anterior cervical spine surgery rates and in-hospital mortality: an examination of United States trends from 1992 to 2005. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;34(18):1956-1962. doi:10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181ab930e.

23. Cahill KS, Chi JH, Day A, Claus EB. Prevalence, complications, and hospital charges associated with use of bone-morphogenetic proteins in spinal fusion procedures. JAMA.2009;302(1):58-66. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.956.

24. Ingraham AM, Richards KE, Hall BL, Ko CY. Quality improvement in surgery: the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program approach. Adv Surg. 2010;44(1):251-267. doi:10.1016/j.yasu.2010.05.003.

25. Shiloach M, Frencher SK Jr, Steeger JE, et al. Toward robust information: data quality and inter-rater reliability in the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210(1):6-16. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.09.031.

26. ACS-NSQIP. Data Use Agreement. American College of Surgeons Web site. https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/acs-nsqip/participant-use/puf-form. Accessed September 20, 2018.

27. Blacher J, Guerin AP, Pannier B, Marchais SJ, London GM. Arterial calcifications, arterial stiffness, and cardiovascular risk in end-stage renal disease. Hypertension. 2001;38(4):938-942. doi:10.1161/hy1001.096358.

28. Browne JA, Cook C, Olson SA, Bolognesi MP. Resident duty-hour reform associated with increased morbidity following hip fracture. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(9):2079-2085. doi:10.2106/jbjs.h.01240.

29. Browne JA, Pietrobon R, Olson SA. Hip fracture outcomes: does surgeon or hospital volume really matter? J Trauma. 2009;66(3):809-814. doi:10.1097/TA.0b013e31816166bb.

30. Menendez ME, Ring D. Failure to rescue after proximal femur fracture surgery. J Orthop Trauma. 2015;29(3):e96-e102. doi:10.1097/bot.0000000000000234.

31. Nikkel LE, Fox EJ, Black KP, Davis C, Andersen L, Hollenbeak CS. Impact of comorbidities on hospitalization costs following hip fracture. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(1):9-17. doi:10.2106/jbjs.j.01077.

32. Anderson KL, Koval KJ, Spratt KF. Hip fracture outcome: is there a “July effect”? Am J Orthop. 2009;38(12):606-611.

33. Koval KJ, Rust CL, Spratt KF. The effect of hospital setting and teaching status on outcomes after hip fracture. Am J Orthop. 2011;40(1):19-28.

34. Bacon WE. Secular trends in hip fracture occurrence and survival: age and sex differences. J Aging Health. 1996;8(4):538-553. doi:10.1177/089826439600800404.

35. Orces CH. In-hospital hip fracture mortality trends in older adults: the National Hospital Discharge Survey, 1988-2007. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(12):2248-2249. doi:10.1111/jgs.12567.

ABSTRACT

This study uses a prospective surgical registry to characterize the timing of 10 postoperative adverse events following geriatric hip fracture surgery. There were 19,873 patients identified who were ≥70 years undergoing surgery for hip fracture as part of the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS-NSQIP). The median postoperative day of diagnosis (and interquartile range) for myocardial infarction was 3 (1-5), cardiac arrest requiring cardiopulmonary resuscitation 3 (0-8), stroke 3 (1-10), pneumonia 4 (2-10), pulmonary embolism 4 (2-11), urinary tract infection 7 (2-13), deep vein thrombosis 9 (4-16), sepsis 9 (4-18), mortality 11 (6-19), and surgical site infection 16 (11-22). For the earliest diagnosed adverse events, the rate of adverse events had diminished by postoperative day 30. For the later diagnosed adverse events, the rate of adverse events remained high at postoperative day 30. Findings help to enable more targeted clinical surveillance, inform patient counseling, and determine the duration of follow-up required to study specific adverse events effectively. Orthopedic surgeons should have the lowest threshold for testing for each adverse event during the time period of greatest risk.

Continue to: Geriatric hip fracture surgery is associated with...

Geriatric hip fracture surgery is associated with a higher rate of occurrence of postoperative adverse events than any other commonly performed orthopedic procedure.1-4 Indeed, the 90-day mortality rate following a geriatric hip fracture surgery may be as high as 15%2 and the 30-day morbidity rate as high as 30%.3 Furthermore, more than half of postoperative mortalities following orthopedic procedures occur after surgery for hip fracture.4 Therefore, extensive research has been conducted regarding interventions to reduce the rates of adverse events following a hip fracture surgery.5-12 For example, randomized trials have been conducted involving venous thromboembolism prophylaxis,5,6nutritional supplementation,7 delirium prevention,8-10 anemia correction,11 geriatrics consultation,9 and anesthetic technique.12

Despite these extensive research efforts, there is currently little information in the literature regarding when postoperative adverse events occur. A clear depiction of the timing of adverse events could help target clinical surveillance, inform patient counseling, and determine the duration of follow-up required for studies. The reason that the timing of adverse events has not been previously characterized may be that the sample sizes available through standard single- or multi-institutional studies may be insufficient to accurately characterize the timing of rare adverse events (eg, myocardial infarction, stroke, etc.). Moreover, although administrative datasets have become common data sources for investigation of rare postoperative adverse events,13-16 such data sources often do not contain data on the timing of diagnosis.

The American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS-NSQIP) is a relatively new and growing surgical registry.1,3,13-22 The registry follows up patients undergoing surgical procedures at several hundred community and academic institutions nationwide. Unlike the administrative datasets discussed above, the ACS-NSQIP characterizes the postoperative day of diagnosis of well-defined adverse events during the first 30 postoperative days.22

In this study, data collected by the ACS-NSQIP are used to characterize the timing of 10 specific postoperative adverse events following a geriatric hip fracture surgery.

Continue to: METHODS...

METHODS

A retrospective analysis of data collected prospectively through the ACS-NSQIP was conducted. Geriatric patients who underwent hip fracture surgery during 2010 to 2013 were identified. Specific inclusion criteria were (1) International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, diagnosis code 820, (2) primary Current Procedural Terminology codes 27125, 27130, 27235, 27236, 27244, or 27245, and (3) age ≥70 years.

The ACS-NSQIP captures patient demographic, comorbidity, and procedural characteristics at baseline.22 At the end of the 30-day follow-up period, the ACS-NSQIP personnel review both inpatient and outpatient charts to characterize the occurrence vs nonoccurrence of specific postoperative adverse events.22-25 When an adverse event does occur, the postoperative day of diagnosis is recorded.

For this study, the following adverse event categories were investigated: myocardial infarction, cardiac arrest requiring cardiopulmonary resuscitation, stroke, pneumonia, pulmonary embolism, urinary tract infection, deep vein thrombosis, sepsis (either with or without shock), mortality, and surgical site infection (including superficial surgical site infection, deep surgical site infection, and organ or space surgical site infection). Detailed definitions of each adverse event are provided in ACS-NSQIP materials.22

First, the 30-day incidence (and the associated 95% confidence interval) was determined for each adverse event. Second, the median postoperative day of diagnosis (and the associated interquartile range) was determined for each adverse event. Third, the postoperative length of stay was used to estimate the proportion of diagnoses occurring prior to vs following discharge for each adverse event. Finally, multivariate Cox proportional hazards models were used to identify independent risk factors for earlier occurrence of postoperative adverse events. The final models were selected using a backward stepwise process that sequentially eliminated variables with the weakest associations until all variables had P < .05.

Because the ACS-NSQIP reports timing data in calendar days, when the postoperative length of stay was equivalent to the postoperative day of diagnosis, it was not possible to ascertain whether the diagnosis occurred prior to or following discharge. For this study, when the postoperative length of stay was equivalent to the postoperative day of diagnosis, the adverse event was considered to have been diagnosed following discharge. The rationale for this is that for most of the adverse events, it was thought to be unlikely that an inpatient would be discharged before the end of the same day as an inpatient diagnosis. However, there was one exception to this rule; when the postoperative day of discharge, the postoperative length of stay, and the postoperative day of death were all equivalent, the adverse event was considered to have occurred prior to discharge. This is because when a patient dies during the initial inpatient stay, the ACS-NSQIP considers the postoperative length of stay to be equivalent to the postoperative day of death. This makes it much more likely that a diagnosis on the final hospital day had occurred in a patient who had not been discharged.

The mandatory ACS-NSQIP statement is “The American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program and the hospitals participating in the ACS-NSQIP are the source of the data used herein; they have not verified and are not responsible for the statistical validity of the data analysis or the conclusions derived by the authors.”26

Continue to: RESULTS...

RESULTS

In total, 19,873 geriatric patients undergoing a hip fracture surgery were identified (Table 1). The rates of adverse events ranged from 6.7% for urinary tract infection to 0.6% for pulmonary embolism (Table 2).

Table 1. Patient Population

| Number | Percent |

Total | 19,873 | 100.0% |

Age |

|

|

70-74 years | 1852 | 9.3% |

75-79 years | 2764 | 13.9% |

80-84 years | 4328 | 21.8% |

85-89 years | 5525 | 27.8% |

≥90 years | 5404 | 27.2% |

Sex |

|

|

Male | 5359 | 27.0% |

Female | 14,514 | 73.0% |

Body mass index |

|

|

<30 kg/m2 | 17,733 | 89.2% |

≥30 kg/m2 | 2140 | 10.8% |

Functional status |

|

|

Independent | 14,348 | 72.2% |

Dependent | 5525 | 27.8% |

Diabetes | 3321 | 16.7% |

Congestive heart failure | 738 | 3.7% |

Dyspnea on exertion | 1542 | 7.8% |

Hypertension | 14,265 | 71.8% |

End-stage renal disease | 322 | 1.6% |

COPD | 2239 | 11.3% |

Current smoker | 1506 | 7.6% |

Abbreviation: COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Table 2. Patients with Adverse Events Diagnosed During the First 30 postoperative days (N = 19,873)

Adverse Event | Number | Percent | 95% CI |

Urinary tract infection | 1321 | 6.7% | 6.3%-7.0% |

Mortality | 1240 | 6.2% | 5.9%-6.6% |

Pneumonia | 771 | 3.9% | 3.6%-4.2% |

Sepsis | 428 | 2.2% | 2.0%-2.4% |

Myocardial infarction | 347 | 1.8% | 1.6%-1.9% |

Surgical site infection | 247 | 1.2% | 1.1%-1.4% |

Deep vein thrombosis | 199 | 1.0% | 0.9%-1.1% |

Stroke | 144 | 0.7% | 0.6%-0.8% |

Cardiac arrest | 136 | 0.7% | 0.6%-0.8% |

Pulmonary embolism | 126 | 0.6% | 0.5%-0.7% |

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

Figure 1 depicts the timing of postoperative adverse events in detail in histograms and timing curves. For the earliest diagnosed adverse events, the rate of adverse events had diminished by postoperative day 30. For the later diagnosed adverse events, the rate of adverse events remained high at postoperative day 30.

Figure 2 provides the summary statistics for adverse events diagnosed in the first 30 postoperative days. The median postoperative day of diagnosis (and the interquartile range) was 3 (1-5) for myocardial infarction, 3 (0-8) for cardiac arrest requiring cardiopulmonary resuscitation, 3 (1-10) for stroke, 4 (2-10) for pneumonia, 4 (2-11) for pulmonary embolism, 7 (2-13) for urinary tract infection, 9 (4-16) for deep vein thrombosis, 9 (4-18) for sepsis, 11 (6-19) for mortality, and 16 (11-22) for surgical site infection.

Figure 3 depicts the timing of adverse events relative to discharge. The proportions of adverse events diagnosed prior to discharge were 81.0% for myocardial infarction, 77.8% for stroke, 76.1% for cardiac arrest requiring cardiopulmonary resuscitation, 71.9% for pulmonary embolism, 71.1% for pneumonia, 58.0% for urinary tract infection, 52.1% for sepsis, 46.9% for deep vein thrombosis, 44.3% for mortality, and 27.6% for surgical site infection.

Table 3 shows the independent risk factors for earlier occurrence of adverse events. Following multivariate stepwise selection of final models, at least 1 patient characteristic was independently associated with the timing of cardiac arrest, stroke, urinary tract infection, deep vein thrombosis, and death. In contrast, no patient characteristics were independently associated with the timing of myocardial infarction, pneumonia, pulmonary embolism, sepsis, and surgical site infection.

Table 3. Timing of Diagnosis of Adverse Eventsa

Adverse events and associated baseline characteristic(s) | Median postoperative day of diagnosis with vs without baseline characteristic | P-valueb |

Cardiac arrest |

|

|

End-stage renal disease | 1 vs 3 | .005 |

Stroke |

|

|

Hypertension | 4 vs 2 | .025 |

Dependent functional status | 2 vs 4 | .027 |

Urinary tract infection |

|

|

Female sex | 6 vs 8 | .009 |

Deep vein thrombosis |

|

|

Body mass index ≥30 kg/m2 | 5 vs 10 | .015 |

Death |

|

|

End-stage renal disease | 10 vs 11 | .031 |

aBaseline characteristics that were independently associated with the timing of each adverse event were identified through a backwards stepwise selection process initially including all characteristics listed in Table 1, and sequentially excluding characteristics with the weakest associations until only characteristics with P < .05 remained. Independent associations with the timing of cardiac arrest, stroke, urinary tract infection, deep vein thrombosis, and death are shown. There were no characteristics independently associated with timing of myocardial infarction, pneumonia, pulmonary embolism, sepsis, or surgical site infection; hence, these adverse events are not listed in the table.

bFrom final Cox proportional hazards models identified through multivariate stepwise selection.

Continue to: DISCUSSION...

DISCUSSION

Adverse events are extremely common following a geriatric hip fracture surgery.1-4 Despite extensive investigation regarding methods to prevent these events,5-12 there is limited published description of the timing at which such events occur. This study used a large prospectively followed up cohort of geriatric patients undergoing a hip fracture surgery to deliver a better description of the timing of adverse events than was previously available. The findings of this study should enable more targeted clinical surveillance, inform patient counseling, and help determine the duration of follow-up required for studies on adverse events.

There was wide variability in the timing at which the different postoperative adverse events were diagnosed (Figures 1, 2). Myocardial infarction was diagnosed the earliest, with more than three-fourth of diagnoses in the first postoperative week. Other relatively early-diagnosed adverse events included cardiac arrest requiring cardiopulmonary resuscitation, stroke, pneumonia, and pulmonary embolism.

The latest-diagnosed adverse event was surgical site infection (Figures 1, 2). Surgical site infection was actually the only adverse event with a rate of diagnosis during the first week that was lower than the rate of diagnosis later in the month (as can be seen by the inflection in the timing curve for surgical site infection in Figure 1). Mortality showed a relatively consistent rate of diagnosis throughout the entire first postoperative month. Other relatively late-diagnosed postoperative events, including sepsis, deep vein thrombosis, and urinary tract infection, showed varying degrees of decreased rate of diagnosis near the end of the first postoperative month. Of note, for the later-diagnosed adverse events, the estimated median and interquartile ranges (Figure 2) were presumably quite biased toward earlier diagnosis, as the 30-day follow-up period clearly failed to capture a large proportion of later-occurring adverse events (Figure 1).

Certain risk factors were independently associated with earlier occurrence of adverse events. Perhaps most strikingly, body mass index in the obese range was associated with substantially earlier occurrence of deep vein thrombosis (median of 5 vs 10 days). This finding suggests that clinical monitoring for deep vein thrombosis should be performed earlier in patients with greater body mass index. Also notable is the earlier occurrence of cardiac arrest and death among patients with end-stage renal disease than among those without. Patients with end-stage renal disease may have a greater risk for these adverse events immediately following the cardiac stresses of surgery.27 Similarly, such patients may be more prone to early electrolyte abnormalities and arrhythmia.

Continue to: In addition to its clinical implications, this study...

In addition to its clinical implications, this study informs about the interpretation of the many studies of adverse events following hip fracture procedures that have been conducted using retrospective data. Several such studies have relied on inpatient-only administrative databases.4,13,14,28-35 As clearly demonstrated in Figure 3, for most of the commonly studied adverse events, inpatient-only databases failed to capture a large proportion of adverse events occurring in the first postoperative month. This highlights a substantial limitation of this commonly published type of study that is often not emphasized in the literature.

There has also been an increase in the publication of studies of adverse events following a hip fracture surgery using the ACS-NSQIP data.3,13,14,17,18,21 As discussed, the ACS-NSQIP provides data on 30-days of follow-up. This relatively extended follow-up is often touted as a distinct advantage. However, this study demonstrates that even the 30-day follow-up afforded by the ACS-NSQIP is limited in its ability to enable investigation of the later-occurring adverse events (Figure 1). In particular, the rate of surgical site infection shows little sign of slowing by postoperative day 30. Similarly, the rates of mortality, sepsis, deep vein thrombosis, and urinary tract infection remain substantial.

This study does have limitations. First, as discussed, the duration of follow-up is a limitation of any ACS-NSQIP-based investigation, including this study. Second, the ACS-NSQIP does not capture relevant orthopedic-specific outcomes (eg, screw cutout). In addition, it could not be determined with certainty whether adverse events occurring on the final hospital day occurred prior to or following discharge. However, only a small proportion of most of the adverse events was diagnosed on the final hospital day. Finally, the ACS-NSQIP reports on days from the operation until diagnosis of the adverse event. Although some adverse events are probably diagnosed quickly after they have occurred (eg, myocardial infarction and cardiac arrest), other adverse events may have a delayed diagnosis (eg, surgical site infection may be identified days after its initial occurrence during a follow-up examination). Therefore, it is important to note the subtle distinction between occurrence and diagnosis throughout the article. This article reports on the timing of diagnosis, not actual occurrence.

CONCLUSION

The timing of postoperative adverse events has been understudied in the past. This may be due to an inability of standard single- or multi-institutional investigations to achieve sample sizes adequate to study the less commonly occurring adverse events. Using a relatively new prospective surgical registry, this study provides a far more detailed description of the timing of adverse events following surgery than was previously available. The authors anticipate that these data can be used to inform patient counseling, target clinical surveillance, and direct clinical research. The authors chose to study the timing of postoperative adverse events following geriatric hip fracture surgery because of the high rate of adverse events associated with the procedure. However, future ACS-NSQIP studies may involve characterization of the timing of adverse events following other orthopedic and non-orthopedic procedures.

This paper will be judged for the Resident Writer’s Award.

ABSTRACT

This study uses a prospective surgical registry to characterize the timing of 10 postoperative adverse events following geriatric hip fracture surgery. There were 19,873 patients identified who were ≥70 years undergoing surgery for hip fracture as part of the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS-NSQIP). The median postoperative day of diagnosis (and interquartile range) for myocardial infarction was 3 (1-5), cardiac arrest requiring cardiopulmonary resuscitation 3 (0-8), stroke 3 (1-10), pneumonia 4 (2-10), pulmonary embolism 4 (2-11), urinary tract infection 7 (2-13), deep vein thrombosis 9 (4-16), sepsis 9 (4-18), mortality 11 (6-19), and surgical site infection 16 (11-22). For the earliest diagnosed adverse events, the rate of adverse events had diminished by postoperative day 30. For the later diagnosed adverse events, the rate of adverse events remained high at postoperative day 30. Findings help to enable more targeted clinical surveillance, inform patient counseling, and determine the duration of follow-up required to study specific adverse events effectively. Orthopedic surgeons should have the lowest threshold for testing for each adverse event during the time period of greatest risk.

Continue to: Geriatric hip fracture surgery is associated with...

Geriatric hip fracture surgery is associated with a higher rate of occurrence of postoperative adverse events than any other commonly performed orthopedic procedure.1-4 Indeed, the 90-day mortality rate following a geriatric hip fracture surgery may be as high as 15%2 and the 30-day morbidity rate as high as 30%.3 Furthermore, more than half of postoperative mortalities following orthopedic procedures occur after surgery for hip fracture.4 Therefore, extensive research has been conducted regarding interventions to reduce the rates of adverse events following a hip fracture surgery.5-12 For example, randomized trials have been conducted involving venous thromboembolism prophylaxis,5,6nutritional supplementation,7 delirium prevention,8-10 anemia correction,11 geriatrics consultation,9 and anesthetic technique.12

Despite these extensive research efforts, there is currently little information in the literature regarding when postoperative adverse events occur. A clear depiction of the timing of adverse events could help target clinical surveillance, inform patient counseling, and determine the duration of follow-up required for studies. The reason that the timing of adverse events has not been previously characterized may be that the sample sizes available through standard single- or multi-institutional studies may be insufficient to accurately characterize the timing of rare adverse events (eg, myocardial infarction, stroke, etc.). Moreover, although administrative datasets have become common data sources for investigation of rare postoperative adverse events,13-16 such data sources often do not contain data on the timing of diagnosis.

The American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS-NSQIP) is a relatively new and growing surgical registry.1,3,13-22 The registry follows up patients undergoing surgical procedures at several hundred community and academic institutions nationwide. Unlike the administrative datasets discussed above, the ACS-NSQIP characterizes the postoperative day of diagnosis of well-defined adverse events during the first 30 postoperative days.22

In this study, data collected by the ACS-NSQIP are used to characterize the timing of 10 specific postoperative adverse events following a geriatric hip fracture surgery.

Continue to: METHODS...

METHODS

A retrospective analysis of data collected prospectively through the ACS-NSQIP was conducted. Geriatric patients who underwent hip fracture surgery during 2010 to 2013 were identified. Specific inclusion criteria were (1) International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, diagnosis code 820, (2) primary Current Procedural Terminology codes 27125, 27130, 27235, 27236, 27244, or 27245, and (3) age ≥70 years.

The ACS-NSQIP captures patient demographic, comorbidity, and procedural characteristics at baseline.22 At the end of the 30-day follow-up period, the ACS-NSQIP personnel review both inpatient and outpatient charts to characterize the occurrence vs nonoccurrence of specific postoperative adverse events.22-25 When an adverse event does occur, the postoperative day of diagnosis is recorded.

For this study, the following adverse event categories were investigated: myocardial infarction, cardiac arrest requiring cardiopulmonary resuscitation, stroke, pneumonia, pulmonary embolism, urinary tract infection, deep vein thrombosis, sepsis (either with or without shock), mortality, and surgical site infection (including superficial surgical site infection, deep surgical site infection, and organ or space surgical site infection). Detailed definitions of each adverse event are provided in ACS-NSQIP materials.22

First, the 30-day incidence (and the associated 95% confidence interval) was determined for each adverse event. Second, the median postoperative day of diagnosis (and the associated interquartile range) was determined for each adverse event. Third, the postoperative length of stay was used to estimate the proportion of diagnoses occurring prior to vs following discharge for each adverse event. Finally, multivariate Cox proportional hazards models were used to identify independent risk factors for earlier occurrence of postoperative adverse events. The final models were selected using a backward stepwise process that sequentially eliminated variables with the weakest associations until all variables had P < .05.

Because the ACS-NSQIP reports timing data in calendar days, when the postoperative length of stay was equivalent to the postoperative day of diagnosis, it was not possible to ascertain whether the diagnosis occurred prior to or following discharge. For this study, when the postoperative length of stay was equivalent to the postoperative day of diagnosis, the adverse event was considered to have been diagnosed following discharge. The rationale for this is that for most of the adverse events, it was thought to be unlikely that an inpatient would be discharged before the end of the same day as an inpatient diagnosis. However, there was one exception to this rule; when the postoperative day of discharge, the postoperative length of stay, and the postoperative day of death were all equivalent, the adverse event was considered to have occurred prior to discharge. This is because when a patient dies during the initial inpatient stay, the ACS-NSQIP considers the postoperative length of stay to be equivalent to the postoperative day of death. This makes it much more likely that a diagnosis on the final hospital day had occurred in a patient who had not been discharged.

The mandatory ACS-NSQIP statement is “The American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program and the hospitals participating in the ACS-NSQIP are the source of the data used herein; they have not verified and are not responsible for the statistical validity of the data analysis or the conclusions derived by the authors.”26

Continue to: RESULTS...

RESULTS

In total, 19,873 geriatric patients undergoing a hip fracture surgery were identified (Table 1). The rates of adverse events ranged from 6.7% for urinary tract infection to 0.6% for pulmonary embolism (Table 2).

Table 1. Patient Population

| Number | Percent |

Total | 19,873 | 100.0% |

Age |

|

|

70-74 years | 1852 | 9.3% |

75-79 years | 2764 | 13.9% |

80-84 years | 4328 | 21.8% |

85-89 years | 5525 | 27.8% |

≥90 years | 5404 | 27.2% |

Sex |

|

|

Male | 5359 | 27.0% |

Female | 14,514 | 73.0% |

Body mass index |

|

|

<30 kg/m2 | 17,733 | 89.2% |

≥30 kg/m2 | 2140 | 10.8% |

Functional status |

|

|

Independent | 14,348 | 72.2% |

Dependent | 5525 | 27.8% |

Diabetes | 3321 | 16.7% |

Congestive heart failure | 738 | 3.7% |

Dyspnea on exertion | 1542 | 7.8% |

Hypertension | 14,265 | 71.8% |

End-stage renal disease | 322 | 1.6% |

COPD | 2239 | 11.3% |

Current smoker | 1506 | 7.6% |

Abbreviation: COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Table 2. Patients with Adverse Events Diagnosed During the First 30 postoperative days (N = 19,873)

Adverse Event | Number | Percent | 95% CI |

Urinary tract infection | 1321 | 6.7% | 6.3%-7.0% |

Mortality | 1240 | 6.2% | 5.9%-6.6% |

Pneumonia | 771 | 3.9% | 3.6%-4.2% |

Sepsis | 428 | 2.2% | 2.0%-2.4% |

Myocardial infarction | 347 | 1.8% | 1.6%-1.9% |

Surgical site infection | 247 | 1.2% | 1.1%-1.4% |

Deep vein thrombosis | 199 | 1.0% | 0.9%-1.1% |

Stroke | 144 | 0.7% | 0.6%-0.8% |

Cardiac arrest | 136 | 0.7% | 0.6%-0.8% |

Pulmonary embolism | 126 | 0.6% | 0.5%-0.7% |

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

Figure 1 depicts the timing of postoperative adverse events in detail in histograms and timing curves. For the earliest diagnosed adverse events, the rate of adverse events had diminished by postoperative day 30. For the later diagnosed adverse events, the rate of adverse events remained high at postoperative day 30.

Figure 2 provides the summary statistics for adverse events diagnosed in the first 30 postoperative days. The median postoperative day of diagnosis (and the interquartile range) was 3 (1-5) for myocardial infarction, 3 (0-8) for cardiac arrest requiring cardiopulmonary resuscitation, 3 (1-10) for stroke, 4 (2-10) for pneumonia, 4 (2-11) for pulmonary embolism, 7 (2-13) for urinary tract infection, 9 (4-16) for deep vein thrombosis, 9 (4-18) for sepsis, 11 (6-19) for mortality, and 16 (11-22) for surgical site infection.

Figure 3 depicts the timing of adverse events relative to discharge. The proportions of adverse events diagnosed prior to discharge were 81.0% for myocardial infarction, 77.8% for stroke, 76.1% for cardiac arrest requiring cardiopulmonary resuscitation, 71.9% for pulmonary embolism, 71.1% for pneumonia, 58.0% for urinary tract infection, 52.1% for sepsis, 46.9% for deep vein thrombosis, 44.3% for mortality, and 27.6% for surgical site infection.

Table 3 shows the independent risk factors for earlier occurrence of adverse events. Following multivariate stepwise selection of final models, at least 1 patient characteristic was independently associated with the timing of cardiac arrest, stroke, urinary tract infection, deep vein thrombosis, and death. In contrast, no patient characteristics were independently associated with the timing of myocardial infarction, pneumonia, pulmonary embolism, sepsis, and surgical site infection.

Table 3. Timing of Diagnosis of Adverse Eventsa

Adverse events and associated baseline characteristic(s) | Median postoperative day of diagnosis with vs without baseline characteristic | P-valueb |

Cardiac arrest |

|

|

End-stage renal disease | 1 vs 3 | .005 |

Stroke |

|

|

Hypertension | 4 vs 2 | .025 |

Dependent functional status | 2 vs 4 | .027 |

Urinary tract infection |

|

|

Female sex | 6 vs 8 | .009 |

Deep vein thrombosis |

|

|

Body mass index ≥30 kg/m2 | 5 vs 10 | .015 |

Death |

|

|

End-stage renal disease | 10 vs 11 | .031 |

aBaseline characteristics that were independently associated with the timing of each adverse event were identified through a backwards stepwise selection process initially including all characteristics listed in Table 1, and sequentially excluding characteristics with the weakest associations until only characteristics with P < .05 remained. Independent associations with the timing of cardiac arrest, stroke, urinary tract infection, deep vein thrombosis, and death are shown. There were no characteristics independently associated with timing of myocardial infarction, pneumonia, pulmonary embolism, sepsis, or surgical site infection; hence, these adverse events are not listed in the table.

bFrom final Cox proportional hazards models identified through multivariate stepwise selection.

Continue to: DISCUSSION...

DISCUSSION

Adverse events are extremely common following a geriatric hip fracture surgery.1-4 Despite extensive investigation regarding methods to prevent these events,5-12 there is limited published description of the timing at which such events occur. This study used a large prospectively followed up cohort of geriatric patients undergoing a hip fracture surgery to deliver a better description of the timing of adverse events than was previously available. The findings of this study should enable more targeted clinical surveillance, inform patient counseling, and help determine the duration of follow-up required for studies on adverse events.

There was wide variability in the timing at which the different postoperative adverse events were diagnosed (Figures 1, 2). Myocardial infarction was diagnosed the earliest, with more than three-fourth of diagnoses in the first postoperative week. Other relatively early-diagnosed adverse events included cardiac arrest requiring cardiopulmonary resuscitation, stroke, pneumonia, and pulmonary embolism.

The latest-diagnosed adverse event was surgical site infection (Figures 1, 2). Surgical site infection was actually the only adverse event with a rate of diagnosis during the first week that was lower than the rate of diagnosis later in the month (as can be seen by the inflection in the timing curve for surgical site infection in Figure 1). Mortality showed a relatively consistent rate of diagnosis throughout the entire first postoperative month. Other relatively late-diagnosed postoperative events, including sepsis, deep vein thrombosis, and urinary tract infection, showed varying degrees of decreased rate of diagnosis near the end of the first postoperative month. Of note, for the later-diagnosed adverse events, the estimated median and interquartile ranges (Figure 2) were presumably quite biased toward earlier diagnosis, as the 30-day follow-up period clearly failed to capture a large proportion of later-occurring adverse events (Figure 1).

Certain risk factors were independently associated with earlier occurrence of adverse events. Perhaps most strikingly, body mass index in the obese range was associated with substantially earlier occurrence of deep vein thrombosis (median of 5 vs 10 days). This finding suggests that clinical monitoring for deep vein thrombosis should be performed earlier in patients with greater body mass index. Also notable is the earlier occurrence of cardiac arrest and death among patients with end-stage renal disease than among those without. Patients with end-stage renal disease may have a greater risk for these adverse events immediately following the cardiac stresses of surgery.27 Similarly, such patients may be more prone to early electrolyte abnormalities and arrhythmia.

Continue to: In addition to its clinical implications, this study...

In addition to its clinical implications, this study informs about the interpretation of the many studies of adverse events following hip fracture procedures that have been conducted using retrospective data. Several such studies have relied on inpatient-only administrative databases.4,13,14,28-35 As clearly demonstrated in Figure 3, for most of the commonly studied adverse events, inpatient-only databases failed to capture a large proportion of adverse events occurring in the first postoperative month. This highlights a substantial limitation of this commonly published type of study that is often not emphasized in the literature.

There has also been an increase in the publication of studies of adverse events following a hip fracture surgery using the ACS-NSQIP data.3,13,14,17,18,21 As discussed, the ACS-NSQIP provides data on 30-days of follow-up. This relatively extended follow-up is often touted as a distinct advantage. However, this study demonstrates that even the 30-day follow-up afforded by the ACS-NSQIP is limited in its ability to enable investigation of the later-occurring adverse events (Figure 1). In particular, the rate of surgical site infection shows little sign of slowing by postoperative day 30. Similarly, the rates of mortality, sepsis, deep vein thrombosis, and urinary tract infection remain substantial.

This study does have limitations. First, as discussed, the duration of follow-up is a limitation of any ACS-NSQIP-based investigation, including this study. Second, the ACS-NSQIP does not capture relevant orthopedic-specific outcomes (eg, screw cutout). In addition, it could not be determined with certainty whether adverse events occurring on the final hospital day occurred prior to or following discharge. However, only a small proportion of most of the adverse events was diagnosed on the final hospital day. Finally, the ACS-NSQIP reports on days from the operation until diagnosis of the adverse event. Although some adverse events are probably diagnosed quickly after they have occurred (eg, myocardial infarction and cardiac arrest), other adverse events may have a delayed diagnosis (eg, surgical site infection may be identified days after its initial occurrence during a follow-up examination). Therefore, it is important to note the subtle distinction between occurrence and diagnosis throughout the article. This article reports on the timing of diagnosis, not actual occurrence.

CONCLUSION

The timing of postoperative adverse events has been understudied in the past. This may be due to an inability of standard single- or multi-institutional investigations to achieve sample sizes adequate to study the less commonly occurring adverse events. Using a relatively new prospective surgical registry, this study provides a far more detailed description of the timing of adverse events following surgery than was previously available. The authors anticipate that these data can be used to inform patient counseling, target clinical surveillance, and direct clinical research. The authors chose to study the timing of postoperative adverse events following geriatric hip fracture surgery because of the high rate of adverse events associated with the procedure. However, future ACS-NSQIP studies may involve characterization of the timing of adverse events following other orthopedic and non-orthopedic procedures.

This paper will be judged for the Resident Writer’s Award.

1. Schilling PL, Hallstrom BR, Birkmeyer JD, Carpenter JE. Prioritizing perioperative quality improvement in orthopaedic surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(9):1884-1889. doi:10.2106/jbjs.i.00735.

2. Forte ML, Virnig BA, Swiontkowski MF, et al. Ninety-day mortality after intertrochanteric hip fracture: does provider volume matter? J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(4):799-806. doi:10.2106/jbjs.h.01204.

3. Pugely AJ, Martin CT, Gao Y, Klocke NF, Callaghan JJ, Marsh JL. A risk calculator for short-term morbidity and mortality after hip fracture surgery. J Orthop Trauma.2014;28(2):63-69. doi:10.1097/BOT.0b013e3182a22744.

4. Bhattacharyya T, Iorio R, Healy WL. Rate of and risk factors for acute inpatient mortality after orthopaedic surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84-a(4):562-572.

5. Eriksson BI, Lassen MR. Duration of prophylaxis against venous thromboembolism with fondaparinux after hip fracture surgery: a multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(11):1337-1342. doi:10.1001/archinte.163.11.1337.

6. Handoll HH, Farrar MJ, McBirnie J, Tytherleigh-Strong G, Milne AA, Gillespie WJ. Heparin, low molecular weight heparin and physical methods for preventing deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism following surgery for hip fractures. Cochrane Database Syst Rev.2002;(4):Cd000305. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd000305.

7. Avenell A, Handoll HH. Nutritional supplementation for hip fracture aftercare in the elderly. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(1):Cd001880. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001880.pub2.

8. Marcantonio ER, Flacker JM, Wright RJ, Resnick NM. Reducing delirium after hip fracture: a randomized trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49(5):516-522. doi:10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49108.x.

9. Deschodt M, Braes T, Flamaing J, et al. Preventing delirium in older adults with recent hip fracture through multidisciplinary geriatric consultation. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(4):733-739. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03899.x.

10. Marcantonio ER, Palihnich K, Appleton P, Davis RB. Pilot randomized trial of donepezil hydrochloride for delirium after hip fracture. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59 Suppl 2:S282-S288. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03691.x.

11. Parker MJ. Iron supplementation for anemia after hip fracture surgery: a randomized trial of 300 patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(2):265-269. doi:10.2106/jbjs.i.00883.

12. Urwin SC, Parker MJ, Griffiths R. General versus regional anaesthesia for hip fracture surgery: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Br J Anaesth. 2000;84(4):450-455. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.bja.a013468.

13. Bohl DD, Basques BA, Golinvaux NS, Baumgaertner MR, Grauer JN. Nationwide Inpatient Sample and National Surgical Quality Improvement Program give different results in hip fracture studies. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(6):1672-1680. doi:10.1007/s11999-014-3559-0.

14. Bohl DD, Grauer JN, Leopold SS. Editor's spotlight/Take 5: nationwide inpatient sample and national surgical quality improvement program give different results in hip fracture studies. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(6):1667-1671. doi:10.1007/s11999-014-3595-9.

15. Bohl DD, Russo GS, Basques BA, et al. Variations in data collection methods between national databases affect study results: a comparison of the nationwide inpatient sample and national surgical quality improvement program databases for lumbar spine fusion procedures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(23):e193. doi:10.2106/jbjs.m.01490.

16. Levin PE. Apples, oranges, and national databases: commentary on an article by Daniel D. Bohl, MPH, et al.: "Variations in data collection methods between national databases affect study results: a comparison of the nationwide inpatient sample and national surgical quality improvement program databases for lumbar spine fusion procedures.” J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(23):e198. doi:10.2106/jbjs.n.00890.

17. Basques BA, Bohl DD, Golinvaux NS, Leslie MP, Baumgaertner MR, Grauer JN. Postoperative length of stay and thirty-day readmission following geriatric hip fracture: an analysis of 8,434 patients. J Orthop Trauma. 2015;29(3):e115-e120. doi:10.1097/bot.0000000000000222.

18. Golinvaux NS, Bohl DD, Basques BA, Baumgaertner MR, Grauer JN. Diabetes confers little to no increased risk of postoperative complications after hip fracture surgery in geriatric patients. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(3):1043-1051. doi:10.1007/s11999-014-3945-7.

19. Maciejewski ML, Radcliff TA, Henderson WG, et al. Determinants of postsurgical discharge setting for male hip fracture patients. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2013;50(9):1267-1276. doi:10.1682/jrrd.2013.02.0041.

20. Molina CS, Thakore RV, Blumer A, Obremskey WT, Sethi MK. Use of the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program in orthopaedic surgery. Clin Orthop Relat Res.2015;473(5):1574-1581. doi:10.1007/s11999-014-3597-7.

21. Bohl DD, Basques BA, Golinvaux NS, Miller CP, Baumgaertner MR, Grauer JN. Extramedullary compared with intramedullary implants for intertrochanteric hip fractures: thirty-day outcomes of 4432 procedures from the ACS NSQIP database. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(22):1871-1877. doi:10.2106/jbjs.n.00041.

22. Alosh H, Riley LH 3rd, Skolasky RL. Insurance status, geography, race, and ethnicity as predictors of anterior cervical spine surgery rates and in-hospital mortality: an examination of United States trends from 1992 to 2005. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;34(18):1956-1962. doi:10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181ab930e.

23. Cahill KS, Chi JH, Day A, Claus EB. Prevalence, complications, and hospital charges associated with use of bone-morphogenetic proteins in spinal fusion procedures. JAMA.2009;302(1):58-66. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.956.

24. Ingraham AM, Richards KE, Hall BL, Ko CY. Quality improvement in surgery: the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program approach. Adv Surg. 2010;44(1):251-267. doi:10.1016/j.yasu.2010.05.003.

25. Shiloach M, Frencher SK Jr, Steeger JE, et al. Toward robust information: data quality and inter-rater reliability in the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210(1):6-16. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.09.031.

26. ACS-NSQIP. Data Use Agreement. American College of Surgeons Web site. https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/acs-nsqip/participant-use/puf-form. Accessed September 20, 2018.

27. Blacher J, Guerin AP, Pannier B, Marchais SJ, London GM. Arterial calcifications, arterial stiffness, and cardiovascular risk in end-stage renal disease. Hypertension. 2001;38(4):938-942. doi:10.1161/hy1001.096358.

28. Browne JA, Cook C, Olson SA, Bolognesi MP. Resident duty-hour reform associated with increased morbidity following hip fracture. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(9):2079-2085. doi:10.2106/jbjs.h.01240.

29. Browne JA, Pietrobon R, Olson SA. Hip fracture outcomes: does surgeon or hospital volume really matter? J Trauma. 2009;66(3):809-814. doi:10.1097/TA.0b013e31816166bb.

30. Menendez ME, Ring D. Failure to rescue after proximal femur fracture surgery. J Orthop Trauma. 2015;29(3):e96-e102. doi:10.1097/bot.0000000000000234.

31. Nikkel LE, Fox EJ, Black KP, Davis C, Andersen L, Hollenbeak CS. Impact of comorbidities on hospitalization costs following hip fracture. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(1):9-17. doi:10.2106/jbjs.j.01077.

32. Anderson KL, Koval KJ, Spratt KF. Hip fracture outcome: is there a “July effect”? Am J Orthop. 2009;38(12):606-611.

33. Koval KJ, Rust CL, Spratt KF. The effect of hospital setting and teaching status on outcomes after hip fracture. Am J Orthop. 2011;40(1):19-28.

34. Bacon WE. Secular trends in hip fracture occurrence and survival: age and sex differences. J Aging Health. 1996;8(4):538-553. doi:10.1177/089826439600800404.

35. Orces CH. In-hospital hip fracture mortality trends in older adults: the National Hospital Discharge Survey, 1988-2007. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(12):2248-2249. doi:10.1111/jgs.12567.

1. Schilling PL, Hallstrom BR, Birkmeyer JD, Carpenter JE. Prioritizing perioperative quality improvement in orthopaedic surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(9):1884-1889. doi:10.2106/jbjs.i.00735.

2. Forte ML, Virnig BA, Swiontkowski MF, et al. Ninety-day mortality after intertrochanteric hip fracture: does provider volume matter? J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(4):799-806. doi:10.2106/jbjs.h.01204.

3. Pugely AJ, Martin CT, Gao Y, Klocke NF, Callaghan JJ, Marsh JL. A risk calculator for short-term morbidity and mortality after hip fracture surgery. J Orthop Trauma.2014;28(2):63-69. doi:10.1097/BOT.0b013e3182a22744.

4. Bhattacharyya T, Iorio R, Healy WL. Rate of and risk factors for acute inpatient mortality after orthopaedic surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84-a(4):562-572.

5. Eriksson BI, Lassen MR. Duration of prophylaxis against venous thromboembolism with fondaparinux after hip fracture surgery: a multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(11):1337-1342. doi:10.1001/archinte.163.11.1337.

6. Handoll HH, Farrar MJ, McBirnie J, Tytherleigh-Strong G, Milne AA, Gillespie WJ. Heparin, low molecular weight heparin and physical methods for preventing deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism following surgery for hip fractures. Cochrane Database Syst Rev.2002;(4):Cd000305. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd000305.

7. Avenell A, Handoll HH. Nutritional supplementation for hip fracture aftercare in the elderly. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(1):Cd001880. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001880.pub2.

8. Marcantonio ER, Flacker JM, Wright RJ, Resnick NM. Reducing delirium after hip fracture: a randomized trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49(5):516-522. doi:10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49108.x.

9. Deschodt M, Braes T, Flamaing J, et al. Preventing delirium in older adults with recent hip fracture through multidisciplinary geriatric consultation. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(4):733-739. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03899.x.

10. Marcantonio ER, Palihnich K, Appleton P, Davis RB. Pilot randomized trial of donepezil hydrochloride for delirium after hip fracture. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59 Suppl 2:S282-S288. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03691.x.

11. Parker MJ. Iron supplementation for anemia after hip fracture surgery: a randomized trial of 300 patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(2):265-269. doi:10.2106/jbjs.i.00883.

12. Urwin SC, Parker MJ, Griffiths R. General versus regional anaesthesia for hip fracture surgery: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Br J Anaesth. 2000;84(4):450-455. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.bja.a013468.

13. Bohl DD, Basques BA, Golinvaux NS, Baumgaertner MR, Grauer JN. Nationwide Inpatient Sample and National Surgical Quality Improvement Program give different results in hip fracture studies. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(6):1672-1680. doi:10.1007/s11999-014-3559-0.

14. Bohl DD, Grauer JN, Leopold SS. Editor's spotlight/Take 5: nationwide inpatient sample and national surgical quality improvement program give different results in hip fracture studies. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(6):1667-1671. doi:10.1007/s11999-014-3595-9.

15. Bohl DD, Russo GS, Basques BA, et al. Variations in data collection methods between national databases affect study results: a comparison of the nationwide inpatient sample and national surgical quality improvement program databases for lumbar spine fusion procedures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(23):e193. doi:10.2106/jbjs.m.01490.

16. Levin PE. Apples, oranges, and national databases: commentary on an article by Daniel D. Bohl, MPH, et al.: "Variations in data collection methods between national databases affect study results: a comparison of the nationwide inpatient sample and national surgical quality improvement program databases for lumbar spine fusion procedures.” J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(23):e198. doi:10.2106/jbjs.n.00890.

17. Basques BA, Bohl DD, Golinvaux NS, Leslie MP, Baumgaertner MR, Grauer JN. Postoperative length of stay and thirty-day readmission following geriatric hip fracture: an analysis of 8,434 patients. J Orthop Trauma. 2015;29(3):e115-e120. doi:10.1097/bot.0000000000000222.

18. Golinvaux NS, Bohl DD, Basques BA, Baumgaertner MR, Grauer JN. Diabetes confers little to no increased risk of postoperative complications after hip fracture surgery in geriatric patients. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(3):1043-1051. doi:10.1007/s11999-014-3945-7.

19. Maciejewski ML, Radcliff TA, Henderson WG, et al. Determinants of postsurgical discharge setting for male hip fracture patients. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2013;50(9):1267-1276. doi:10.1682/jrrd.2013.02.0041.

20. Molina CS, Thakore RV, Blumer A, Obremskey WT, Sethi MK. Use of the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program in orthopaedic surgery. Clin Orthop Relat Res.2015;473(5):1574-1581. doi:10.1007/s11999-014-3597-7.

21. Bohl DD, Basques BA, Golinvaux NS, Miller CP, Baumgaertner MR, Grauer JN. Extramedullary compared with intramedullary implants for intertrochanteric hip fractures: thirty-day outcomes of 4432 procedures from the ACS NSQIP database. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(22):1871-1877. doi:10.2106/jbjs.n.00041.

22. Alosh H, Riley LH 3rd, Skolasky RL. Insurance status, geography, race, and ethnicity as predictors of anterior cervical spine surgery rates and in-hospital mortality: an examination of United States trends from 1992 to 2005. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;34(18):1956-1962. doi:10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181ab930e.

23. Cahill KS, Chi JH, Day A, Claus EB. Prevalence, complications, and hospital charges associated with use of bone-morphogenetic proteins in spinal fusion procedures. JAMA.2009;302(1):58-66. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.956.

24. Ingraham AM, Richards KE, Hall BL, Ko CY. Quality improvement in surgery: the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program approach. Adv Surg. 2010;44(1):251-267. doi:10.1016/j.yasu.2010.05.003.

25. Shiloach M, Frencher SK Jr, Steeger JE, et al. Toward robust information: data quality and inter-rater reliability in the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210(1):6-16. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.09.031.

26. ACS-NSQIP. Data Use Agreement. American College of Surgeons Web site. https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/acs-nsqip/participant-use/puf-form. Accessed September 20, 2018.

27. Blacher J, Guerin AP, Pannier B, Marchais SJ, London GM. Arterial calcifications, arterial stiffness, and cardiovascular risk in end-stage renal disease. Hypertension. 2001;38(4):938-942. doi:10.1161/hy1001.096358.