User login

Tender, Diffuse, Edematous, and Erythematous Papules on the Face, Neck, Chest, and Extremities

The Diagnosis: Sweet Syndrome

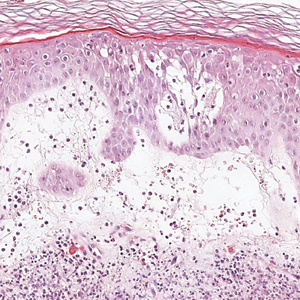

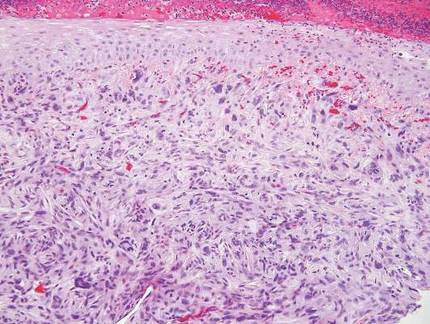

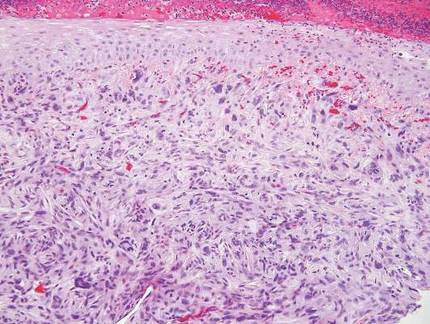

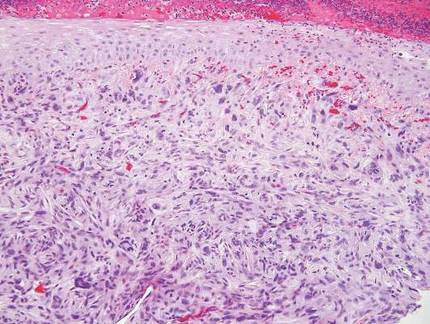

Sweet syndrome, alternatively known as acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis, typically presents with variably tender, erythematous papules, plaques, or nodules in middle-aged adults.1 Systemic symptoms such as fever, fatigue, and arthralgia often accompany these cutaneous findings.1,2 Although the pathophysiology has not been fully elucidated, this syndrome frequently is associated with infections, especially upper respiratory illnesses; medications; and malignancies. Among cases of malignancy-associated Sweet syndrome, hematologic malignancies, particularly acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome, are more common than solid organ malignancies.1,2 Sweet syndrome may precede the associated malignancy by several months; thus, patients without an identifiable trigger for Sweet syndrome should be closely followed.2 Treatment with systemic steroids typically is effective.1,3 Typical histologic features include papillary dermal edema and a brisk neutrophilic infiltrate in the superficial to mid dermis (quiz image).4 Overlying epidermal spongiosis with or without vesiculation also can be seen.4 Leukocytoclasia and endothelial swelling without fibrinoid necrosis are typical, though full-blown leukocytoclastic vasculitis can be seen.3,4 A histiocytoid variant also has been described in which the dermal infiltrate is composed of mononuclear cells reminiscent of histiocytes that are thought to be immature cells of myeloid origin. This variant histologically can simulate leukemia cutis.5

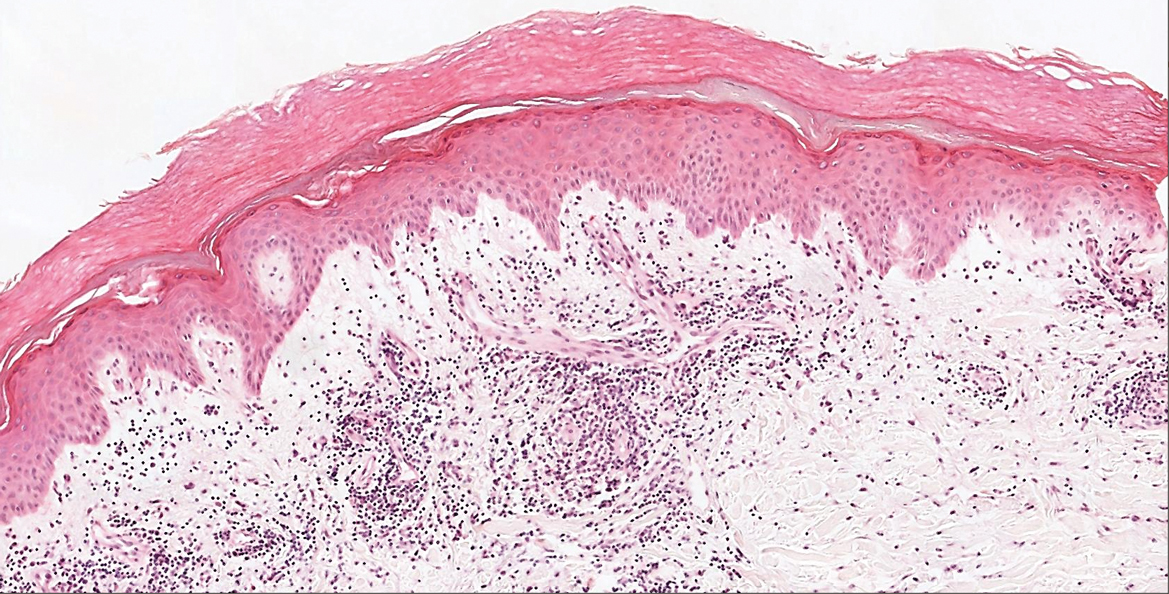

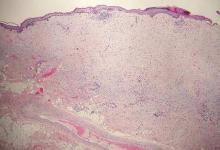

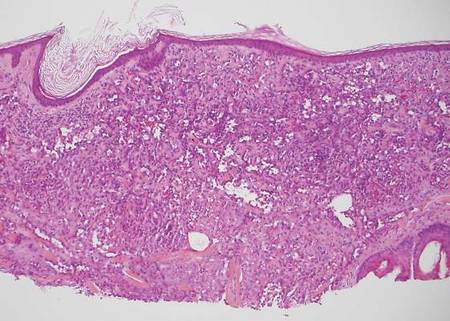

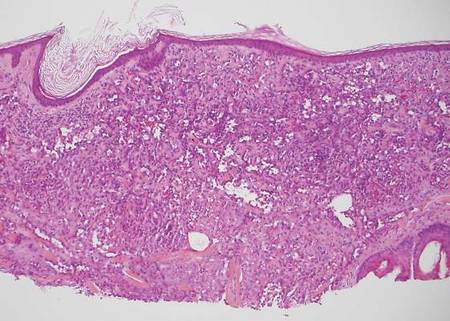

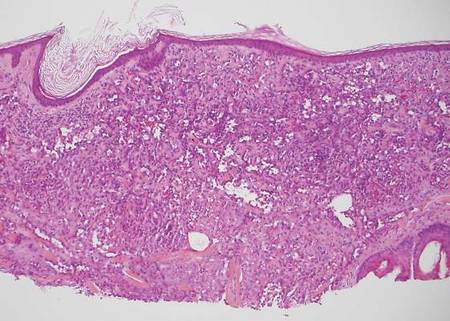

Perniosis, also known as chilblains, typically presents with red to violaceous macules or papules on acral sites, particularly the distal fingers and toes.6,7 It tends to affect young women more frequently than other demographic groups. Although the pathophysiology is not fully understood, perniosis is thought to represent an abnormal inflammatory response to cold environmental conditions. It can occur as an idiopathic disorder or in association with various systemic illnesses including lupus erythematosus.6,7 The typical histologic findings include papillary dermal edema and a lymphocytic infiltrate in the superficial to deep dermis, often with perivascular and perieccrine accentuation (Figure 1).3,6 Other less common microscopic findings include sparse keratinocyte necrosis, basal layer vacuolar change, swelling of endothelial cells, and lymphocytic vasculitis.6 The lesions typically resolve spontaneously within a few weeks, but in some cases they may be chronic.3

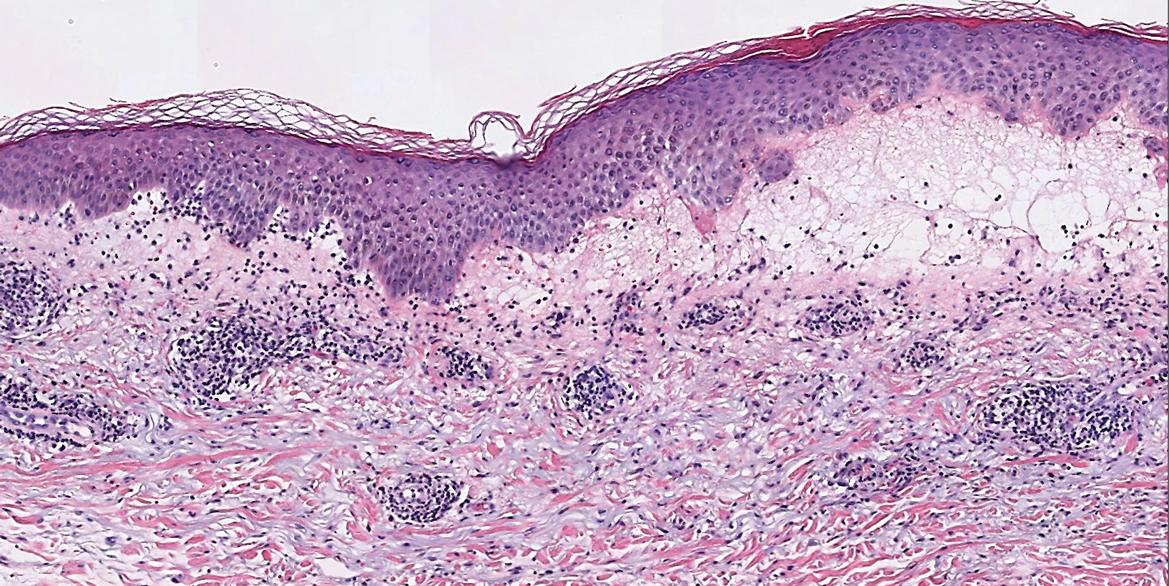

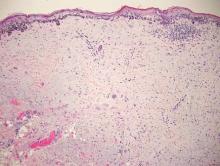

Polymorphous light eruption, a common photodermatosis induced by UV light exposure, typically presents in adolescence or early adulthood with a female predominance. Patients usually develop this pruritic rash on sun-exposed skin other than the face and dorsal aspects of the hands in the spring or early summer upon increased sun exposure after the winter season.3,8 Consistent sunlight exposure throughout the summer months results in decreased flares. Various cutaneous morphologies including papules, vesicles, and plaques can be seen.3,8 Histologic findings include papillary dermal edema and a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate in the superficial to deep dermis (Figure 2).4

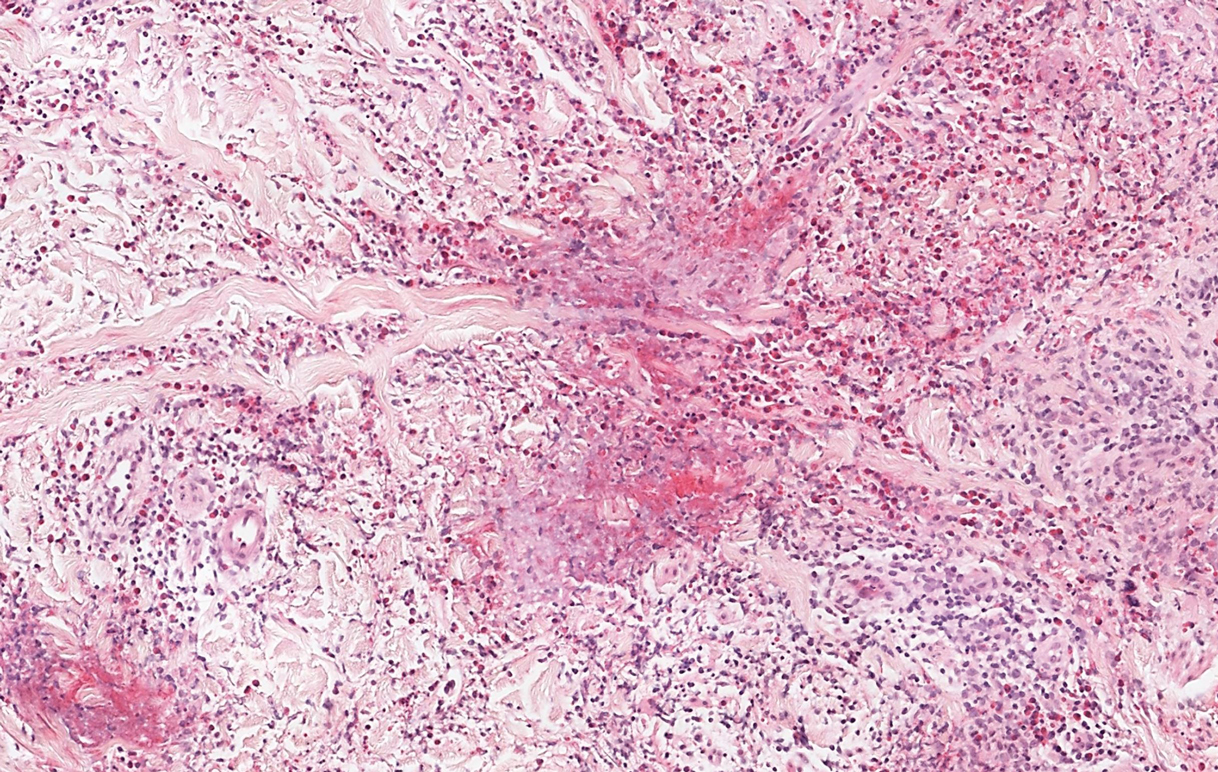

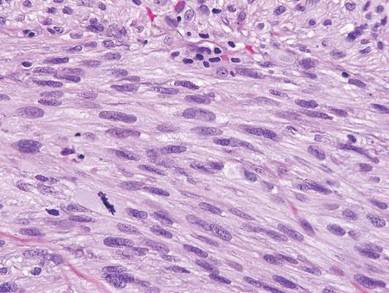

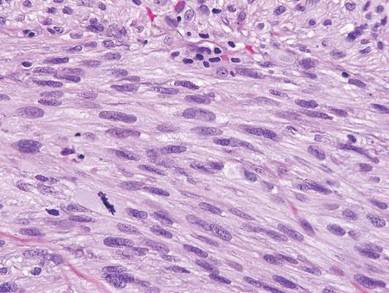

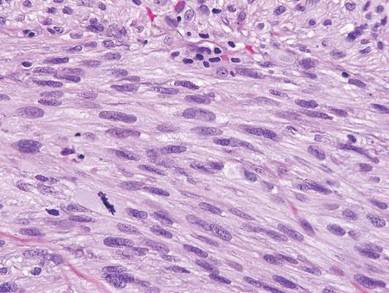

Tinea corporis, a superficial cutaneous dermatophyte infection, typically presents as annular scaly plaques with central clearing. Vesicles and pustules also can be seen.3 The diagnosis can be confirmed via fungal culture, identification of hyphae on microscopic examination of skin scrapings using potassium hydroxide, or cutaneous biopsy. Histologic clues to diagnosis include a "compact stratum corneum (either uniform or forming a layer beneath a basket weave stratum corneum), parakeratosis, mild spongiosis, and neutrophils in the stratum corneum" (Figure 3).9 Papillary dermal edema also may be present, though this finding less commonly is reported.9,10 Because fungal hyphae can be difficult to identify on hematoxylin and eosin-stained slides, special stains such as periodic acid-Schiff or Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver may be helpful.9 These infections are managed with topical or oral antifungal medications.

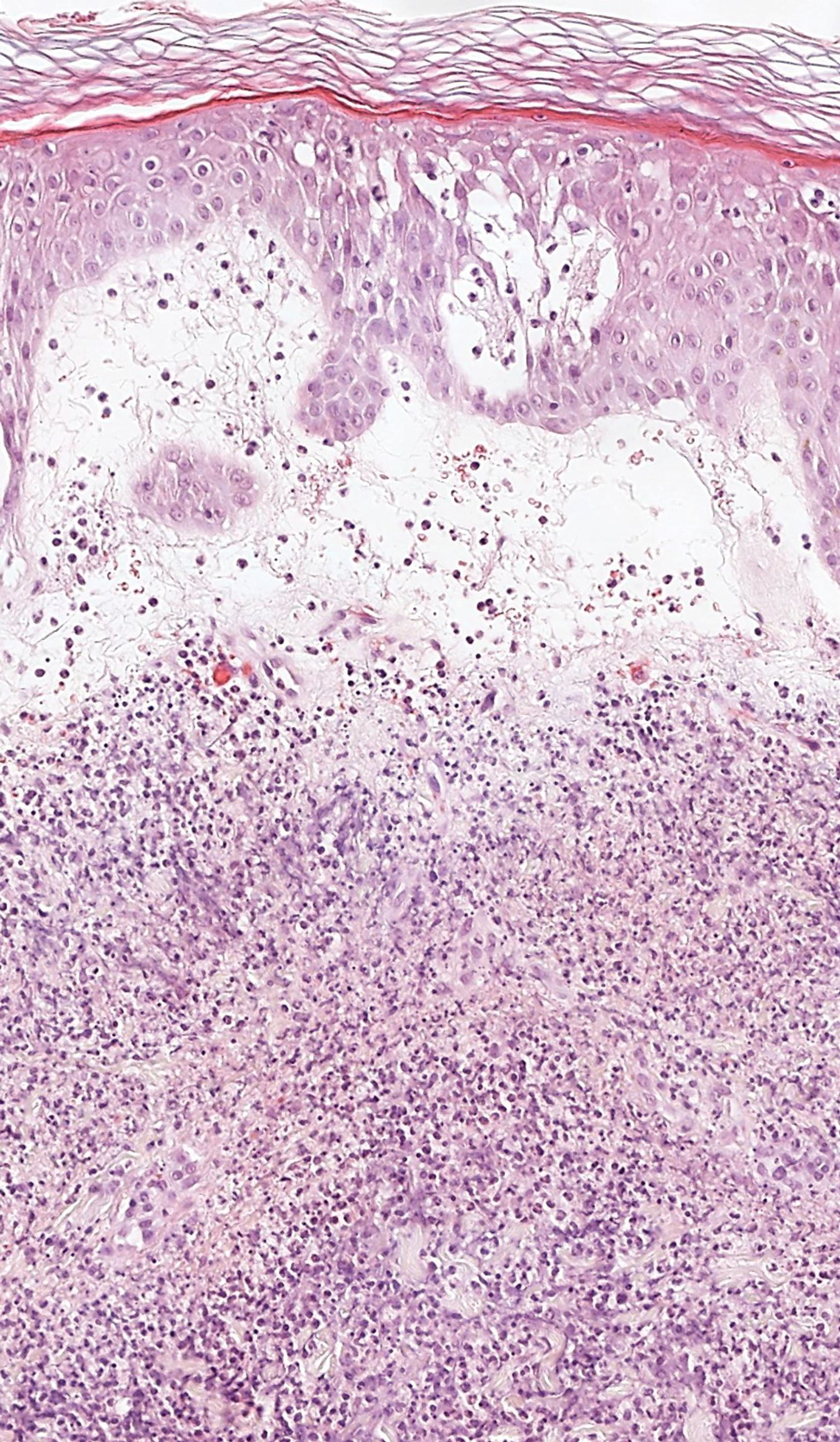

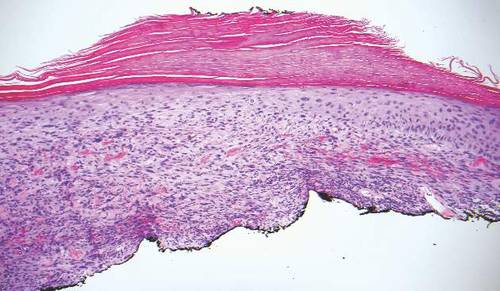

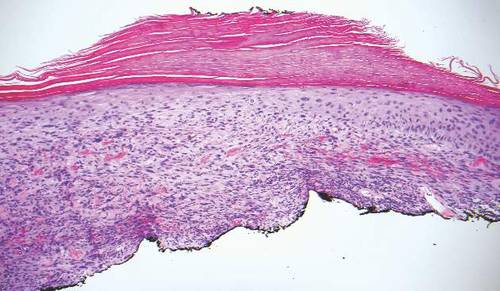

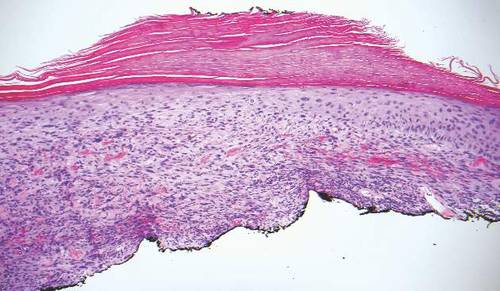

Wells syndrome, also known as eosinophilic cellulitis, presents with an acute eruption that can clinically resemble bacterial cellulitis.3 It has been described in children and adults with various clinical morphologies including plaques, bullae, papulovesicles, and papulonodules. Peripheral eosinophilia may be present.11 The clinical lesions usually resolve spontaneously in a few weeks to months, but recurrences are typical.3,11 Histologic findings include papillary dermal edema with or without subepidermal bulla formation and epidermal spongiosis as well as a mixed inflammatory infiltrate with a predominance of eosinophils and flame figures (Figure 4).4 Flame figures are collagen fibers coated with major basic protein and other constituents of degranulated eosinophils.3 Although flame figures often are present in Wells syndrome, they are not specific to this condition.3,4 Some consider Wells syndrome an exaggerated reaction pattern rather than a specific entity.3

- Rochet N, Chavan R, Cappel M, et al. Sweet syndrome: clinical presentation, associations, and response to treatment in 77 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:557-564.

- Marcoval J, Martín-Callizo C, Valentí-Medina F, et al. Sweet syndrome: long-term follow-up of 138 patients. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2016;41:741-746.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Shaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2012.

- Calonje JE, Brenn T, Lazar AJ, et al. McKee's Pathology of the Skin. 4th ed. Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

- Alegría-Landa V, Rodríguez-Pinilla S, Santos-Briz A, et al. Clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular features of histiocytoid Sweet syndrome. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:651-659.

- Boada A, Bielsa I, Fernández-Figueras M, et al. Perniosis: clinical and histopathological analysis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:19-23.

- Takci Z, Vahaboglu G, Eksioglu H. Epidemiological patterns of perniosis, and its association with systemic disorder. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37:844-849.

- Gruber-Wackernagel A, Byrne S, Wolf P. Polymorphous light eruption: clinic aspects and pathogenesis. Dermatol Clin. 2014;32:315-334.

- Elbendary A, Valdebran M, Gad A, et al. When to suspect tinea; a histopathologic study of 103 cases of PAS-positive tinea. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;46:852-857.

- Hoss D, Berke A, Kerr P, et al. Prominent papillary dermal edema in dermatophytosis (tinea corporis). J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:237-242.

- Caputo R, Marzano A, Vezzoli P, et al. Wells syndrome in adults and children: a report of 19 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1157-1161.

The Diagnosis: Sweet Syndrome

Sweet syndrome, alternatively known as acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis, typically presents with variably tender, erythematous papules, plaques, or nodules in middle-aged adults.1 Systemic symptoms such as fever, fatigue, and arthralgia often accompany these cutaneous findings.1,2 Although the pathophysiology has not been fully elucidated, this syndrome frequently is associated with infections, especially upper respiratory illnesses; medications; and malignancies. Among cases of malignancy-associated Sweet syndrome, hematologic malignancies, particularly acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome, are more common than solid organ malignancies.1,2 Sweet syndrome may precede the associated malignancy by several months; thus, patients without an identifiable trigger for Sweet syndrome should be closely followed.2 Treatment with systemic steroids typically is effective.1,3 Typical histologic features include papillary dermal edema and a brisk neutrophilic infiltrate in the superficial to mid dermis (quiz image).4 Overlying epidermal spongiosis with or without vesiculation also can be seen.4 Leukocytoclasia and endothelial swelling without fibrinoid necrosis are typical, though full-blown leukocytoclastic vasculitis can be seen.3,4 A histiocytoid variant also has been described in which the dermal infiltrate is composed of mononuclear cells reminiscent of histiocytes that are thought to be immature cells of myeloid origin. This variant histologically can simulate leukemia cutis.5

Perniosis, also known as chilblains, typically presents with red to violaceous macules or papules on acral sites, particularly the distal fingers and toes.6,7 It tends to affect young women more frequently than other demographic groups. Although the pathophysiology is not fully understood, perniosis is thought to represent an abnormal inflammatory response to cold environmental conditions. It can occur as an idiopathic disorder or in association with various systemic illnesses including lupus erythematosus.6,7 The typical histologic findings include papillary dermal edema and a lymphocytic infiltrate in the superficial to deep dermis, often with perivascular and perieccrine accentuation (Figure 1).3,6 Other less common microscopic findings include sparse keratinocyte necrosis, basal layer vacuolar change, swelling of endothelial cells, and lymphocytic vasculitis.6 The lesions typically resolve spontaneously within a few weeks, but in some cases they may be chronic.3

Polymorphous light eruption, a common photodermatosis induced by UV light exposure, typically presents in adolescence or early adulthood with a female predominance. Patients usually develop this pruritic rash on sun-exposed skin other than the face and dorsal aspects of the hands in the spring or early summer upon increased sun exposure after the winter season.3,8 Consistent sunlight exposure throughout the summer months results in decreased flares. Various cutaneous morphologies including papules, vesicles, and plaques can be seen.3,8 Histologic findings include papillary dermal edema and a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate in the superficial to deep dermis (Figure 2).4

Tinea corporis, a superficial cutaneous dermatophyte infection, typically presents as annular scaly plaques with central clearing. Vesicles and pustules also can be seen.3 The diagnosis can be confirmed via fungal culture, identification of hyphae on microscopic examination of skin scrapings using potassium hydroxide, or cutaneous biopsy. Histologic clues to diagnosis include a "compact stratum corneum (either uniform or forming a layer beneath a basket weave stratum corneum), parakeratosis, mild spongiosis, and neutrophils in the stratum corneum" (Figure 3).9 Papillary dermal edema also may be present, though this finding less commonly is reported.9,10 Because fungal hyphae can be difficult to identify on hematoxylin and eosin-stained slides, special stains such as periodic acid-Schiff or Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver may be helpful.9 These infections are managed with topical or oral antifungal medications.

Wells syndrome, also known as eosinophilic cellulitis, presents with an acute eruption that can clinically resemble bacterial cellulitis.3 It has been described in children and adults with various clinical morphologies including plaques, bullae, papulovesicles, and papulonodules. Peripheral eosinophilia may be present.11 The clinical lesions usually resolve spontaneously in a few weeks to months, but recurrences are typical.3,11 Histologic findings include papillary dermal edema with or without subepidermal bulla formation and epidermal spongiosis as well as a mixed inflammatory infiltrate with a predominance of eosinophils and flame figures (Figure 4).4 Flame figures are collagen fibers coated with major basic protein and other constituents of degranulated eosinophils.3 Although flame figures often are present in Wells syndrome, they are not specific to this condition.3,4 Some consider Wells syndrome an exaggerated reaction pattern rather than a specific entity.3

The Diagnosis: Sweet Syndrome

Sweet syndrome, alternatively known as acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis, typically presents with variably tender, erythematous papules, plaques, or nodules in middle-aged adults.1 Systemic symptoms such as fever, fatigue, and arthralgia often accompany these cutaneous findings.1,2 Although the pathophysiology has not been fully elucidated, this syndrome frequently is associated with infections, especially upper respiratory illnesses; medications; and malignancies. Among cases of malignancy-associated Sweet syndrome, hematologic malignancies, particularly acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome, are more common than solid organ malignancies.1,2 Sweet syndrome may precede the associated malignancy by several months; thus, patients without an identifiable trigger for Sweet syndrome should be closely followed.2 Treatment with systemic steroids typically is effective.1,3 Typical histologic features include papillary dermal edema and a brisk neutrophilic infiltrate in the superficial to mid dermis (quiz image).4 Overlying epidermal spongiosis with or without vesiculation also can be seen.4 Leukocytoclasia and endothelial swelling without fibrinoid necrosis are typical, though full-blown leukocytoclastic vasculitis can be seen.3,4 A histiocytoid variant also has been described in which the dermal infiltrate is composed of mononuclear cells reminiscent of histiocytes that are thought to be immature cells of myeloid origin. This variant histologically can simulate leukemia cutis.5

Perniosis, also known as chilblains, typically presents with red to violaceous macules or papules on acral sites, particularly the distal fingers and toes.6,7 It tends to affect young women more frequently than other demographic groups. Although the pathophysiology is not fully understood, perniosis is thought to represent an abnormal inflammatory response to cold environmental conditions. It can occur as an idiopathic disorder or in association with various systemic illnesses including lupus erythematosus.6,7 The typical histologic findings include papillary dermal edema and a lymphocytic infiltrate in the superficial to deep dermis, often with perivascular and perieccrine accentuation (Figure 1).3,6 Other less common microscopic findings include sparse keratinocyte necrosis, basal layer vacuolar change, swelling of endothelial cells, and lymphocytic vasculitis.6 The lesions typically resolve spontaneously within a few weeks, but in some cases they may be chronic.3

Polymorphous light eruption, a common photodermatosis induced by UV light exposure, typically presents in adolescence or early adulthood with a female predominance. Patients usually develop this pruritic rash on sun-exposed skin other than the face and dorsal aspects of the hands in the spring or early summer upon increased sun exposure after the winter season.3,8 Consistent sunlight exposure throughout the summer months results in decreased flares. Various cutaneous morphologies including papules, vesicles, and plaques can be seen.3,8 Histologic findings include papillary dermal edema and a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate in the superficial to deep dermis (Figure 2).4

Tinea corporis, a superficial cutaneous dermatophyte infection, typically presents as annular scaly plaques with central clearing. Vesicles and pustules also can be seen.3 The diagnosis can be confirmed via fungal culture, identification of hyphae on microscopic examination of skin scrapings using potassium hydroxide, or cutaneous biopsy. Histologic clues to diagnosis include a "compact stratum corneum (either uniform or forming a layer beneath a basket weave stratum corneum), parakeratosis, mild spongiosis, and neutrophils in the stratum corneum" (Figure 3).9 Papillary dermal edema also may be present, though this finding less commonly is reported.9,10 Because fungal hyphae can be difficult to identify on hematoxylin and eosin-stained slides, special stains such as periodic acid-Schiff or Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver may be helpful.9 These infections are managed with topical or oral antifungal medications.

Wells syndrome, also known as eosinophilic cellulitis, presents with an acute eruption that can clinically resemble bacterial cellulitis.3 It has been described in children and adults with various clinical morphologies including plaques, bullae, papulovesicles, and papulonodules. Peripheral eosinophilia may be present.11 The clinical lesions usually resolve spontaneously in a few weeks to months, but recurrences are typical.3,11 Histologic findings include papillary dermal edema with or without subepidermal bulla formation and epidermal spongiosis as well as a mixed inflammatory infiltrate with a predominance of eosinophils and flame figures (Figure 4).4 Flame figures are collagen fibers coated with major basic protein and other constituents of degranulated eosinophils.3 Although flame figures often are present in Wells syndrome, they are not specific to this condition.3,4 Some consider Wells syndrome an exaggerated reaction pattern rather than a specific entity.3

- Rochet N, Chavan R, Cappel M, et al. Sweet syndrome: clinical presentation, associations, and response to treatment in 77 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:557-564.

- Marcoval J, Martín-Callizo C, Valentí-Medina F, et al. Sweet syndrome: long-term follow-up of 138 patients. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2016;41:741-746.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Shaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2012.

- Calonje JE, Brenn T, Lazar AJ, et al. McKee's Pathology of the Skin. 4th ed. Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

- Alegría-Landa V, Rodríguez-Pinilla S, Santos-Briz A, et al. Clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular features of histiocytoid Sweet syndrome. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:651-659.

- Boada A, Bielsa I, Fernández-Figueras M, et al. Perniosis: clinical and histopathological analysis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:19-23.

- Takci Z, Vahaboglu G, Eksioglu H. Epidemiological patterns of perniosis, and its association with systemic disorder. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37:844-849.

- Gruber-Wackernagel A, Byrne S, Wolf P. Polymorphous light eruption: clinic aspects and pathogenesis. Dermatol Clin. 2014;32:315-334.

- Elbendary A, Valdebran M, Gad A, et al. When to suspect tinea; a histopathologic study of 103 cases of PAS-positive tinea. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;46:852-857.

- Hoss D, Berke A, Kerr P, et al. Prominent papillary dermal edema in dermatophytosis (tinea corporis). J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:237-242.

- Caputo R, Marzano A, Vezzoli P, et al. Wells syndrome in adults and children: a report of 19 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1157-1161.

- Rochet N, Chavan R, Cappel M, et al. Sweet syndrome: clinical presentation, associations, and response to treatment in 77 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:557-564.

- Marcoval J, Martín-Callizo C, Valentí-Medina F, et al. Sweet syndrome: long-term follow-up of 138 patients. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2016;41:741-746.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Shaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2012.

- Calonje JE, Brenn T, Lazar AJ, et al. McKee's Pathology of the Skin. 4th ed. Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

- Alegría-Landa V, Rodríguez-Pinilla S, Santos-Briz A, et al. Clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular features of histiocytoid Sweet syndrome. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:651-659.

- Boada A, Bielsa I, Fernández-Figueras M, et al. Perniosis: clinical and histopathological analysis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:19-23.

- Takci Z, Vahaboglu G, Eksioglu H. Epidemiological patterns of perniosis, and its association with systemic disorder. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37:844-849.

- Gruber-Wackernagel A, Byrne S, Wolf P. Polymorphous light eruption: clinic aspects and pathogenesis. Dermatol Clin. 2014;32:315-334.

- Elbendary A, Valdebran M, Gad A, et al. When to suspect tinea; a histopathologic study of 103 cases of PAS-positive tinea. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;46:852-857.

- Hoss D, Berke A, Kerr P, et al. Prominent papillary dermal edema in dermatophytosis (tinea corporis). J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:237-242.

- Caputo R, Marzano A, Vezzoli P, et al. Wells syndrome in adults and children: a report of 19 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1157-1161.

A 62-year-old woman presented with a tender diffuse eruption of erythematous and edematous papules and plaques on the face, neck, chest, and extremities, some appearing vesiculopustular.

Desmoplastic Melanoma

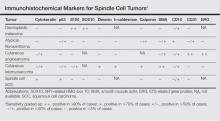

Desmoplastic melanoma, an uncommon variant of melanoma, poses a diagnostic challenge to the clinician because the tumors frequently appear as nonspecific flesh-colored or amelanotic plaques or nodules. They are more common in men than in women and are frequently found on the head and neck.1,2 Their innocuous appearance may lead to a delay in diagnosis and may explain why desmoplastic melanomas often are deeply infiltrative at the time of biopsy. Desmoplastic melanoma arises de novo in approximately one-third of cases.1 In the remainder of cases, it is seen in conjunction with overlying melanoma in situ, most commonly lentigo maligna melanoma.1 Histologically, desmoplastic melanomas are characterized by malignant spindle cells within a densely fibrotic stroma (Figure 1). Adjacent lymphoid aggregates and perineural involvement are common features,2 while pigment and atypical mitoses can be infrequent. Desmoplastic melanoma can be classified as mixed or pure based on the degree of desmoplasia and cellularity. Within mixed desmoplastic melanomas, there are areas that have histologic features of conventional melanomas while others demonstrate more typical desmoplastic characteristics. Pure desmoplastic melanoma has a higher degree of desmoplasia and fewer tumor cells than the mixed type.1 The pure subtype tends to be less aggressive and is less likely to metastasize to the lymph nodes.1 In the absence of an in situ component (Figure 2), desmoplastic melanoma may be indistinguishable from other spindle cell tumors on routine hematoxylin and eosin staining; thus, immunohistochemical staining generally is required. The most reliable stains in confirming a diagnosis of desmoplastic melanoma are S100 and SOX10 (SRY-related HMG-box 10)(Figure 3)(eTable).3

Atypical fibroxathoma typically presents as a nodule in the head and neck region or other sun-exposed areas in elderly individuals and is more commonly seen in men than in women.4 Histologically, atypical fibroxanthomas are composed of pleomorphic spindle, epithelioid, and multinucleated giant cells with numerous and atypical mitoses (Figure 4).5 Atypical fibroxanthoma is considered a diagnosis of exclusion; therefore, other dermal spindle cell tumors need to be ruled out before diagnosis can be made. Atypical fibroxanthomas generally stain negative for cytokeratin, S100, SOX10, and desmin, but in some cases there is positive focal staining for smooth muscle actin.4 Multiple immunohistochemical markers, including CD10, have shown reactivity in atypical fibroxanthomas,4 but none of these markers has a high specificity for this tumor; thus, it remains a diagnosis of exclusion.

Cutaneous angiosarcomas are aggressive tumors associated with a high mortality rate despite appropriate treatment with surgical resection and postoperative radiation treatment. They typically present as ecchymotic macules or nodules on the face or scalp of elderly patients.6,7 Ionizing radiation and chronic lymphedema are risk factors for cutaneous angiosarcoma.6 Histologically, well-differentiated cutaneous angiosarcomas are composed of irregular, anastomosing vascular channels that dissect through the dermis (Figure 5).6,7 Less well-differentiated tumors may contain spindle cells and lack obvious vascular structures; thus immunohistochemistry is essential for making the correct diagnosis in these cases. Cutaneous angiosarcomas typically stain positive for ERG (ETS-related gene) protein, CD31, CD34, and factor VIII.6,8 Unfortunately these tumors may also occasionally stain with cytokeratin, which may lead to the erroneous diagnosis of a carcinoma.6

|  | |

| Figure 4. Pleomorphic spindle, epithelioid, and multinucleate giant cells with atypical mitoses filling the dermis in atypical fibroxanthoma (H&E, original magnification ×200). | Figure 5. Anastamosing vascular channels dissecting through collagen bundles and consuming the epidermis in cutaneous angiosarcoma (H&E, original magnification ×100). |

Cutaneous leiomyosarcoma is a smooth muscle neoplasm that arises from arrector pili muscles, genital smooth muscles, or vascular smooth muscles. It typically presents as a single plaque or nodule on the arms and legs of individuals older than 50 years of age.9 Cutaneous leiomyosarcomas can be classified as either dermal, in which at least 90% of the tumor is confined to the dermis, or subcutaneous; this distinction is important because the latter type has a higher rate of metastasis and a poorer prognosis.9 Because of this tumor’s smooth muscle derivation, well-differentiated tumors may retain features of typical smooth muscle cells, including cigar-shaped nuclei with adjacent glycogen vacuoles (Figure 6). If fascicle formation is observed, this may be an additional clue to the diagnosis. In poorly differentiated tumors, immunohistochemistry is invaluable. Leiomyosarcoma often stains positive for smooth muscle actin, muscle specific actin, h-caldesmon, desmin, and calponin.9-11

Spindle cell squamous cell carcinomas often present as ulcerated nodules on sun-exposed skin or on sites of prior ionizing radiation.2,12 Like desmoplastic melanoma, spindle cell squamous cell carcinomas are characterized by spindle cells in the dermis. Helpful diagnostic clues may include evidence of squamous differentiation, including keratin pearls or overlying actinic keratosis (Figure 7). However, actinic keratosis is common on sun-damaged skin and cannot be used to definitively confirm this diagnosis. There also may be areas of the tumor with more typical epithelioid cells that are easily identified as squamous cell carcinoma.2 Spindle cell squamous cell carcinoma stains positive for high–molecular weight cytokeratin antibodies and p63,2 which can help to differentiate it from the other spindle cell tumors in the differential.

|  | |

| Figure 6. Spindle cells of leiomyosarcoma with cigar-shaped nuclei and adjacent glycogen vacuoles (H&E, original magnification ×600). | Figure 7. Spindle cell squamous cell carcinoma with overlying epidermal atypia that blends with the underlying dermal spindle cells (H&E, original magnification ×100). |

1. Chen LL, Jaimes N, Barker CA, et al. Desmoplastic melanoma: a review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:825-833.

2. Calonje JE, Brenn T, Lazar AJ, et al. McKee’s Pathology of the Skin. 4th ed. St Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

3. Elston DM, Ferringer TC, Ko C, et al. Dermatopathology: Requisites in Dermatology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2014.

4. Luzar B, Calonje E. Morphological and immunohistochemical characteristics of atypical fibroxanthoma with a special emphasis on potential diagnostic pitfalls: a review. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:301-309.

5. Iorizzo LJ III, Brown MD. Atypical fibroxanthoma: a review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37:146-157.

6. Luca DR. Angiosarcoma, radiation-associated angiosarcoma, and atypical vascular lesion. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:1804-1809.

7. Mendenhall WM, Mendenhall CM, Werning JW, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma. Am J Oncol. 2006;29:524-528.

8. Thum C, Husain EA, Mulholland K, et al. Atypical fibroxanthoma with pseudoangiomatous features: a histological and immunohistochemical mimic of cutaneous angiosarcoma. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2013;17:502-507.

9. Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Shaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2012.

10. Hall BJ, Grossmann AH, Webber NP, et al. Atypical intradermal smooth muscle neoplasms (formerly cutaneous leiomyosarcomas): case series, immunohistochemical profile and review of the literature. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2013;21:132-138.

11. Perez-Montiel MD, Plaza JA, Dominguez-Malagon H, et al. Differential expression of smooth muscle myosin, smooth muscle actin, h-caldesmon, and calponin in the diagnosis of myofibroblastic and smooth muscle lesions of skin and soft tissue. Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:105-111.

12. Cassarino DS, DeRienzo DP, Barr RJ. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a comprehensive clinicopathologic classification. part one. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:191-205.

Desmoplastic melanoma, an uncommon variant of melanoma, poses a diagnostic challenge to the clinician because the tumors frequently appear as nonspecific flesh-colored or amelanotic plaques or nodules. They are more common in men than in women and are frequently found on the head and neck.1,2 Their innocuous appearance may lead to a delay in diagnosis and may explain why desmoplastic melanomas often are deeply infiltrative at the time of biopsy. Desmoplastic melanoma arises de novo in approximately one-third of cases.1 In the remainder of cases, it is seen in conjunction with overlying melanoma in situ, most commonly lentigo maligna melanoma.1 Histologically, desmoplastic melanomas are characterized by malignant spindle cells within a densely fibrotic stroma (Figure 1). Adjacent lymphoid aggregates and perineural involvement are common features,2 while pigment and atypical mitoses can be infrequent. Desmoplastic melanoma can be classified as mixed or pure based on the degree of desmoplasia and cellularity. Within mixed desmoplastic melanomas, there are areas that have histologic features of conventional melanomas while others demonstrate more typical desmoplastic characteristics. Pure desmoplastic melanoma has a higher degree of desmoplasia and fewer tumor cells than the mixed type.1 The pure subtype tends to be less aggressive and is less likely to metastasize to the lymph nodes.1 In the absence of an in situ component (Figure 2), desmoplastic melanoma may be indistinguishable from other spindle cell tumors on routine hematoxylin and eosin staining; thus, immunohistochemical staining generally is required. The most reliable stains in confirming a diagnosis of desmoplastic melanoma are S100 and SOX10 (SRY-related HMG-box 10)(Figure 3)(eTable).3

Atypical fibroxathoma typically presents as a nodule in the head and neck region or other sun-exposed areas in elderly individuals and is more commonly seen in men than in women.4 Histologically, atypical fibroxanthomas are composed of pleomorphic spindle, epithelioid, and multinucleated giant cells with numerous and atypical mitoses (Figure 4).5 Atypical fibroxanthoma is considered a diagnosis of exclusion; therefore, other dermal spindle cell tumors need to be ruled out before diagnosis can be made. Atypical fibroxanthomas generally stain negative for cytokeratin, S100, SOX10, and desmin, but in some cases there is positive focal staining for smooth muscle actin.4 Multiple immunohistochemical markers, including CD10, have shown reactivity in atypical fibroxanthomas,4 but none of these markers has a high specificity for this tumor; thus, it remains a diagnosis of exclusion.

Cutaneous angiosarcomas are aggressive tumors associated with a high mortality rate despite appropriate treatment with surgical resection and postoperative radiation treatment. They typically present as ecchymotic macules or nodules on the face or scalp of elderly patients.6,7 Ionizing radiation and chronic lymphedema are risk factors for cutaneous angiosarcoma.6 Histologically, well-differentiated cutaneous angiosarcomas are composed of irregular, anastomosing vascular channels that dissect through the dermis (Figure 5).6,7 Less well-differentiated tumors may contain spindle cells and lack obvious vascular structures; thus immunohistochemistry is essential for making the correct diagnosis in these cases. Cutaneous angiosarcomas typically stain positive for ERG (ETS-related gene) protein, CD31, CD34, and factor VIII.6,8 Unfortunately these tumors may also occasionally stain with cytokeratin, which may lead to the erroneous diagnosis of a carcinoma.6

|  | |

| Figure 4. Pleomorphic spindle, epithelioid, and multinucleate giant cells with atypical mitoses filling the dermis in atypical fibroxanthoma (H&E, original magnification ×200). | Figure 5. Anastamosing vascular channels dissecting through collagen bundles and consuming the epidermis in cutaneous angiosarcoma (H&E, original magnification ×100). |

Cutaneous leiomyosarcoma is a smooth muscle neoplasm that arises from arrector pili muscles, genital smooth muscles, or vascular smooth muscles. It typically presents as a single plaque or nodule on the arms and legs of individuals older than 50 years of age.9 Cutaneous leiomyosarcomas can be classified as either dermal, in which at least 90% of the tumor is confined to the dermis, or subcutaneous; this distinction is important because the latter type has a higher rate of metastasis and a poorer prognosis.9 Because of this tumor’s smooth muscle derivation, well-differentiated tumors may retain features of typical smooth muscle cells, including cigar-shaped nuclei with adjacent glycogen vacuoles (Figure 6). If fascicle formation is observed, this may be an additional clue to the diagnosis. In poorly differentiated tumors, immunohistochemistry is invaluable. Leiomyosarcoma often stains positive for smooth muscle actin, muscle specific actin, h-caldesmon, desmin, and calponin.9-11

Spindle cell squamous cell carcinomas often present as ulcerated nodules on sun-exposed skin or on sites of prior ionizing radiation.2,12 Like desmoplastic melanoma, spindle cell squamous cell carcinomas are characterized by spindle cells in the dermis. Helpful diagnostic clues may include evidence of squamous differentiation, including keratin pearls or overlying actinic keratosis (Figure 7). However, actinic keratosis is common on sun-damaged skin and cannot be used to definitively confirm this diagnosis. There also may be areas of the tumor with more typical epithelioid cells that are easily identified as squamous cell carcinoma.2 Spindle cell squamous cell carcinoma stains positive for high–molecular weight cytokeratin antibodies and p63,2 which can help to differentiate it from the other spindle cell tumors in the differential.

|  | |

| Figure 6. Spindle cells of leiomyosarcoma with cigar-shaped nuclei and adjacent glycogen vacuoles (H&E, original magnification ×600). | Figure 7. Spindle cell squamous cell carcinoma with overlying epidermal atypia that blends with the underlying dermal spindle cells (H&E, original magnification ×100). |

Desmoplastic melanoma, an uncommon variant of melanoma, poses a diagnostic challenge to the clinician because the tumors frequently appear as nonspecific flesh-colored or amelanotic plaques or nodules. They are more common in men than in women and are frequently found on the head and neck.1,2 Their innocuous appearance may lead to a delay in diagnosis and may explain why desmoplastic melanomas often are deeply infiltrative at the time of biopsy. Desmoplastic melanoma arises de novo in approximately one-third of cases.1 In the remainder of cases, it is seen in conjunction with overlying melanoma in situ, most commonly lentigo maligna melanoma.1 Histologically, desmoplastic melanomas are characterized by malignant spindle cells within a densely fibrotic stroma (Figure 1). Adjacent lymphoid aggregates and perineural involvement are common features,2 while pigment and atypical mitoses can be infrequent. Desmoplastic melanoma can be classified as mixed or pure based on the degree of desmoplasia and cellularity. Within mixed desmoplastic melanomas, there are areas that have histologic features of conventional melanomas while others demonstrate more typical desmoplastic characteristics. Pure desmoplastic melanoma has a higher degree of desmoplasia and fewer tumor cells than the mixed type.1 The pure subtype tends to be less aggressive and is less likely to metastasize to the lymph nodes.1 In the absence of an in situ component (Figure 2), desmoplastic melanoma may be indistinguishable from other spindle cell tumors on routine hematoxylin and eosin staining; thus, immunohistochemical staining generally is required. The most reliable stains in confirming a diagnosis of desmoplastic melanoma are S100 and SOX10 (SRY-related HMG-box 10)(Figure 3)(eTable).3

Atypical fibroxathoma typically presents as a nodule in the head and neck region or other sun-exposed areas in elderly individuals and is more commonly seen in men than in women.4 Histologically, atypical fibroxanthomas are composed of pleomorphic spindle, epithelioid, and multinucleated giant cells with numerous and atypical mitoses (Figure 4).5 Atypical fibroxanthoma is considered a diagnosis of exclusion; therefore, other dermal spindle cell tumors need to be ruled out before diagnosis can be made. Atypical fibroxanthomas generally stain negative for cytokeratin, S100, SOX10, and desmin, but in some cases there is positive focal staining for smooth muscle actin.4 Multiple immunohistochemical markers, including CD10, have shown reactivity in atypical fibroxanthomas,4 but none of these markers has a high specificity for this tumor; thus, it remains a diagnosis of exclusion.

Cutaneous angiosarcomas are aggressive tumors associated with a high mortality rate despite appropriate treatment with surgical resection and postoperative radiation treatment. They typically present as ecchymotic macules or nodules on the face or scalp of elderly patients.6,7 Ionizing radiation and chronic lymphedema are risk factors for cutaneous angiosarcoma.6 Histologically, well-differentiated cutaneous angiosarcomas are composed of irregular, anastomosing vascular channels that dissect through the dermis (Figure 5).6,7 Less well-differentiated tumors may contain spindle cells and lack obvious vascular structures; thus immunohistochemistry is essential for making the correct diagnosis in these cases. Cutaneous angiosarcomas typically stain positive for ERG (ETS-related gene) protein, CD31, CD34, and factor VIII.6,8 Unfortunately these tumors may also occasionally stain with cytokeratin, which may lead to the erroneous diagnosis of a carcinoma.6

|  | |

| Figure 4. Pleomorphic spindle, epithelioid, and multinucleate giant cells with atypical mitoses filling the dermis in atypical fibroxanthoma (H&E, original magnification ×200). | Figure 5. Anastamosing vascular channels dissecting through collagen bundles and consuming the epidermis in cutaneous angiosarcoma (H&E, original magnification ×100). |

Cutaneous leiomyosarcoma is a smooth muscle neoplasm that arises from arrector pili muscles, genital smooth muscles, or vascular smooth muscles. It typically presents as a single plaque or nodule on the arms and legs of individuals older than 50 years of age.9 Cutaneous leiomyosarcomas can be classified as either dermal, in which at least 90% of the tumor is confined to the dermis, or subcutaneous; this distinction is important because the latter type has a higher rate of metastasis and a poorer prognosis.9 Because of this tumor’s smooth muscle derivation, well-differentiated tumors may retain features of typical smooth muscle cells, including cigar-shaped nuclei with adjacent glycogen vacuoles (Figure 6). If fascicle formation is observed, this may be an additional clue to the diagnosis. In poorly differentiated tumors, immunohistochemistry is invaluable. Leiomyosarcoma often stains positive for smooth muscle actin, muscle specific actin, h-caldesmon, desmin, and calponin.9-11

Spindle cell squamous cell carcinomas often present as ulcerated nodules on sun-exposed skin or on sites of prior ionizing radiation.2,12 Like desmoplastic melanoma, spindle cell squamous cell carcinomas are characterized by spindle cells in the dermis. Helpful diagnostic clues may include evidence of squamous differentiation, including keratin pearls or overlying actinic keratosis (Figure 7). However, actinic keratosis is common on sun-damaged skin and cannot be used to definitively confirm this diagnosis. There also may be areas of the tumor with more typical epithelioid cells that are easily identified as squamous cell carcinoma.2 Spindle cell squamous cell carcinoma stains positive for high–molecular weight cytokeratin antibodies and p63,2 which can help to differentiate it from the other spindle cell tumors in the differential.

|  | |

| Figure 6. Spindle cells of leiomyosarcoma with cigar-shaped nuclei and adjacent glycogen vacuoles (H&E, original magnification ×600). | Figure 7. Spindle cell squamous cell carcinoma with overlying epidermal atypia that blends with the underlying dermal spindle cells (H&E, original magnification ×100). |

1. Chen LL, Jaimes N, Barker CA, et al. Desmoplastic melanoma: a review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:825-833.

2. Calonje JE, Brenn T, Lazar AJ, et al. McKee’s Pathology of the Skin. 4th ed. St Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

3. Elston DM, Ferringer TC, Ko C, et al. Dermatopathology: Requisites in Dermatology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2014.

4. Luzar B, Calonje E. Morphological and immunohistochemical characteristics of atypical fibroxanthoma with a special emphasis on potential diagnostic pitfalls: a review. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:301-309.

5. Iorizzo LJ III, Brown MD. Atypical fibroxanthoma: a review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37:146-157.

6. Luca DR. Angiosarcoma, radiation-associated angiosarcoma, and atypical vascular lesion. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:1804-1809.

7. Mendenhall WM, Mendenhall CM, Werning JW, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma. Am J Oncol. 2006;29:524-528.

8. Thum C, Husain EA, Mulholland K, et al. Atypical fibroxanthoma with pseudoangiomatous features: a histological and immunohistochemical mimic of cutaneous angiosarcoma. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2013;17:502-507.

9. Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Shaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2012.

10. Hall BJ, Grossmann AH, Webber NP, et al. Atypical intradermal smooth muscle neoplasms (formerly cutaneous leiomyosarcomas): case series, immunohistochemical profile and review of the literature. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2013;21:132-138.

11. Perez-Montiel MD, Plaza JA, Dominguez-Malagon H, et al. Differential expression of smooth muscle myosin, smooth muscle actin, h-caldesmon, and calponin in the diagnosis of myofibroblastic and smooth muscle lesions of skin and soft tissue. Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:105-111.

12. Cassarino DS, DeRienzo DP, Barr RJ. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a comprehensive clinicopathologic classification. part one. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:191-205.

1. Chen LL, Jaimes N, Barker CA, et al. Desmoplastic melanoma: a review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:825-833.

2. Calonje JE, Brenn T, Lazar AJ, et al. McKee’s Pathology of the Skin. 4th ed. St Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

3. Elston DM, Ferringer TC, Ko C, et al. Dermatopathology: Requisites in Dermatology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2014.

4. Luzar B, Calonje E. Morphological and immunohistochemical characteristics of atypical fibroxanthoma with a special emphasis on potential diagnostic pitfalls: a review. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:301-309.

5. Iorizzo LJ III, Brown MD. Atypical fibroxanthoma: a review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37:146-157.

6. Luca DR. Angiosarcoma, radiation-associated angiosarcoma, and atypical vascular lesion. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:1804-1809.

7. Mendenhall WM, Mendenhall CM, Werning JW, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma. Am J Oncol. 2006;29:524-528.

8. Thum C, Husain EA, Mulholland K, et al. Atypical fibroxanthoma with pseudoangiomatous features: a histological and immunohistochemical mimic of cutaneous angiosarcoma. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2013;17:502-507.

9. Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Shaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2012.

10. Hall BJ, Grossmann AH, Webber NP, et al. Atypical intradermal smooth muscle neoplasms (formerly cutaneous leiomyosarcomas): case series, immunohistochemical profile and review of the literature. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2013;21:132-138.

11. Perez-Montiel MD, Plaza JA, Dominguez-Malagon H, et al. Differential expression of smooth muscle myosin, smooth muscle actin, h-caldesmon, and calponin in the diagnosis of myofibroblastic and smooth muscle lesions of skin and soft tissue. Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:105-111.

12. Cassarino DS, DeRienzo DP, Barr RJ. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a comprehensive clinicopathologic classification. part one. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:191-205.