User login

Reticular Hyperpigmentation With Keratotic Papules in the Axillae and Groin

The Diagnosis: Galli-Galli Disease

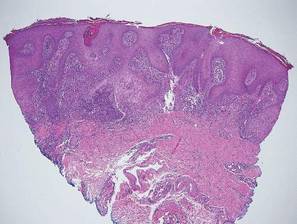

Several cutaneous conditions can present as reticulated hyperpigmentation or keratotic papules. Although genetic testing can help identify some of these dermatoses, biopsy typically is sufficient for diagnosis, and genetic testing can be considered for more clinically challenging cases. In our case, the clinical evidence and histopathologic findings were diagnostic of Galli-Galli disease (GGD), an autosomal-dominant genodermatosis with incomplete penetrance. Our patient was unaware of any family members with a diagnosis of GGD; however, she reported a great uncle with similar clinical findings.

Galli-Galli disease is a rare allelic variant of Dowling- Degos disease (DDD), both caused by a loss-of-function mutation in the keratin 5 gene, KRT5. Both conditions present as reticulated papules distributed symmetrically in the flexural regions, most commonly the axillae and groin, but also as comedolike papules, typically in patients aged 30 to 50 years.1 Cutaneous lesions primarily are of cosmetic concern but can be extremely pruritic, especially for patients with GGD. Gene mutations in protein O-fucosyltransferase 1, POFUT1; protein O-glucosyltransferase 1, POGLUT1; and presenilin enhancer 2, PSENEN, also have been discovered in cases of DDD and GGD.2,3

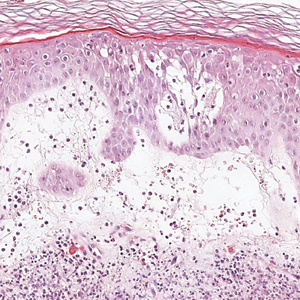

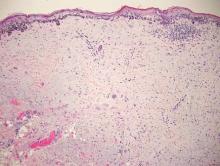

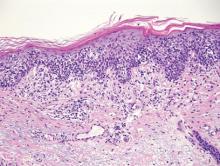

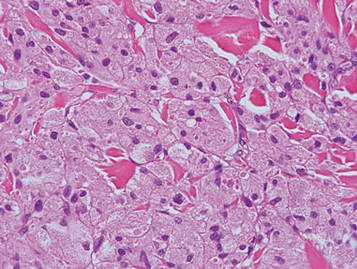

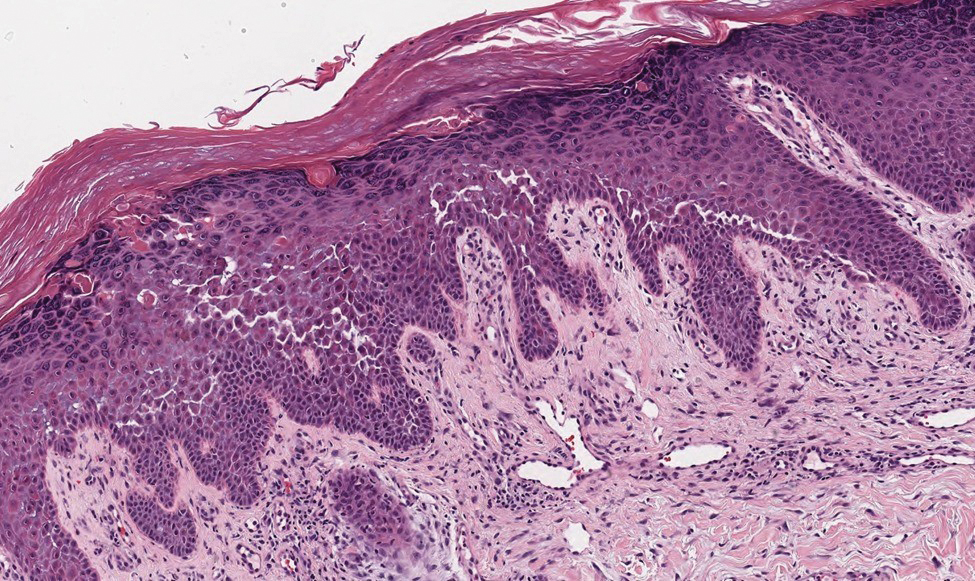

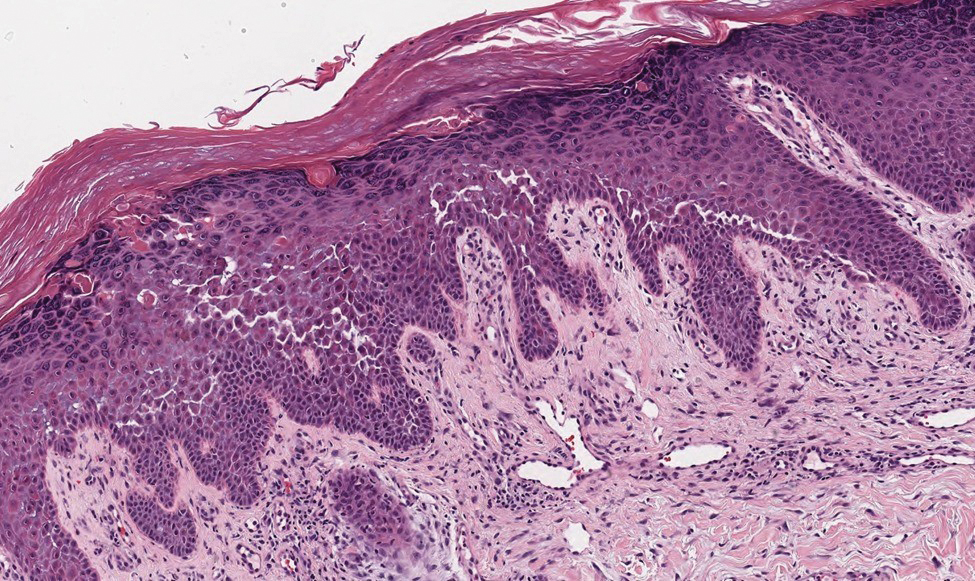

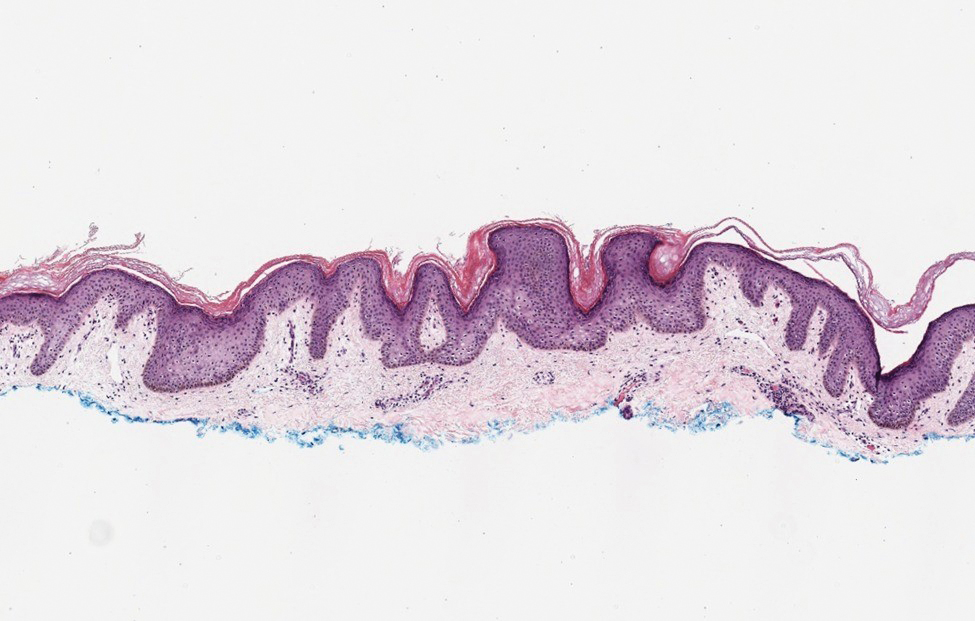

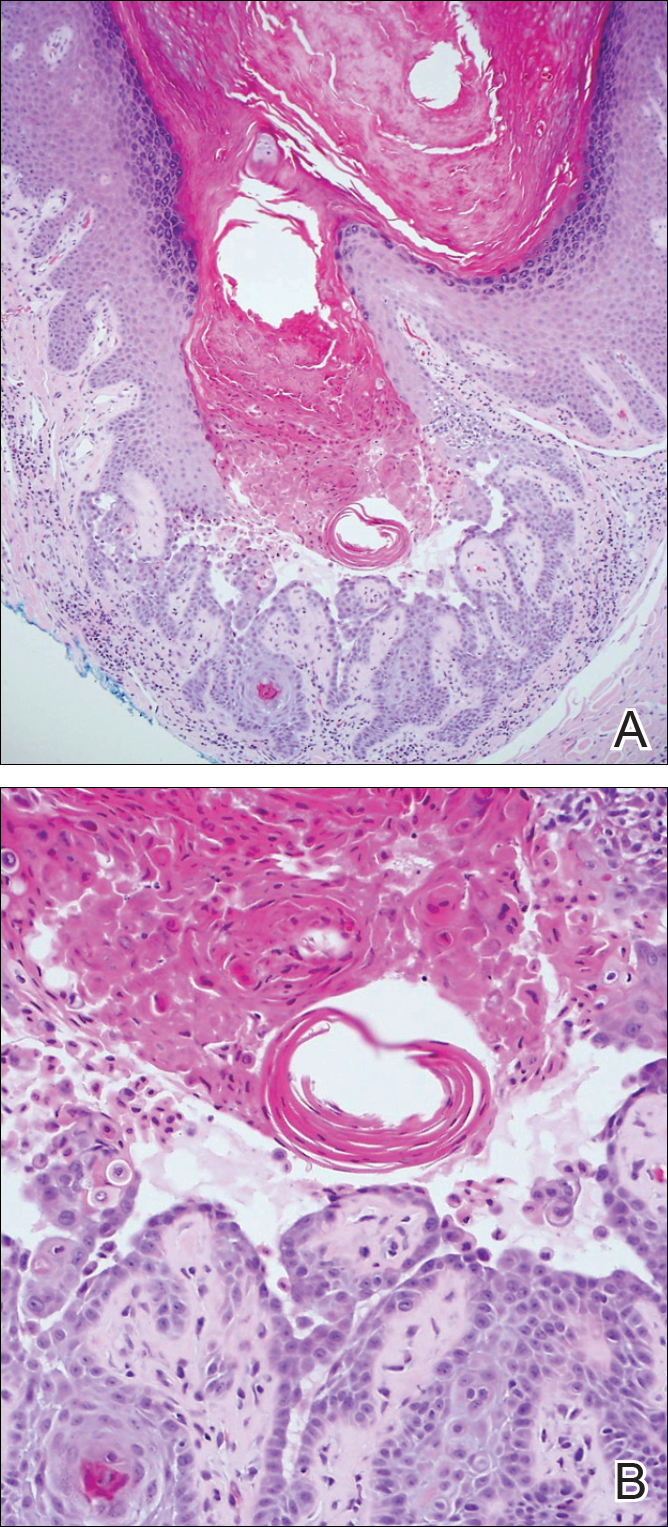

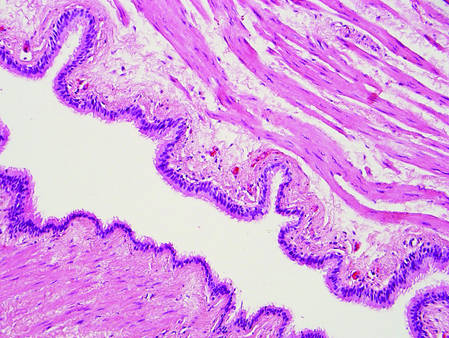

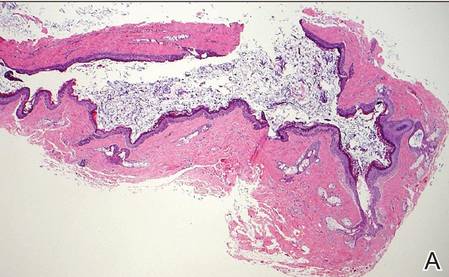

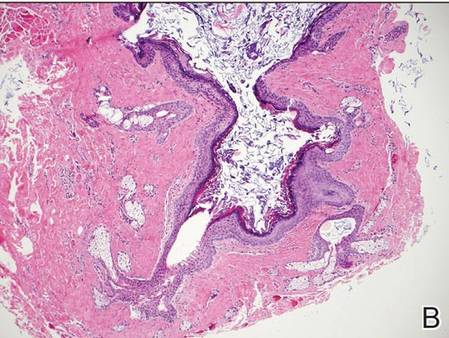

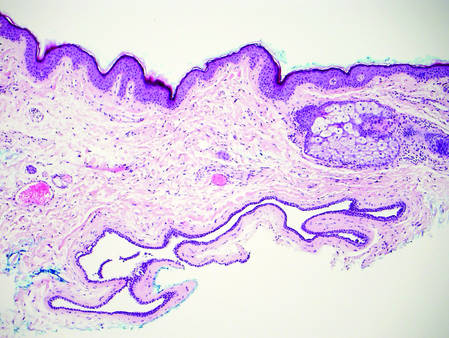

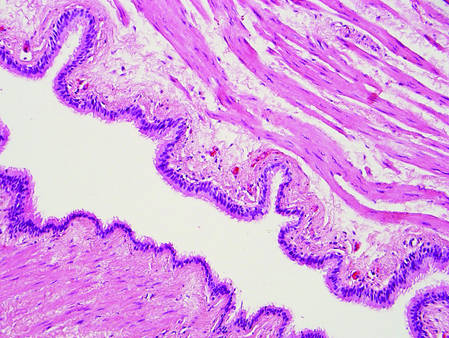

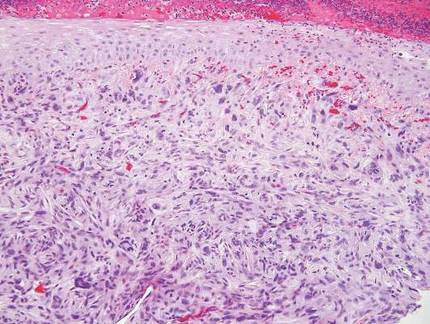

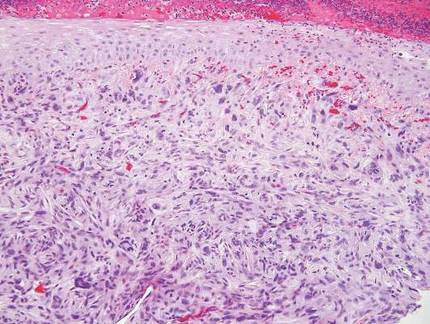

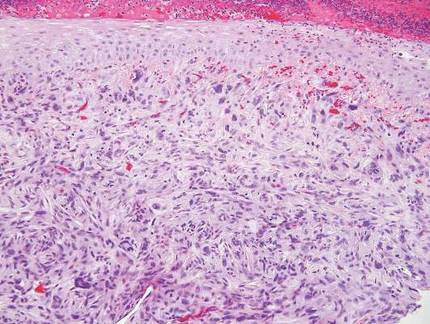

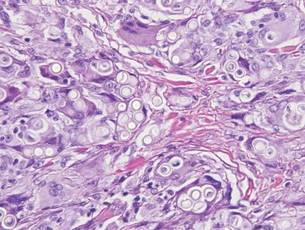

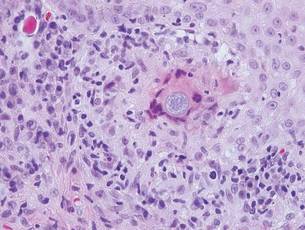

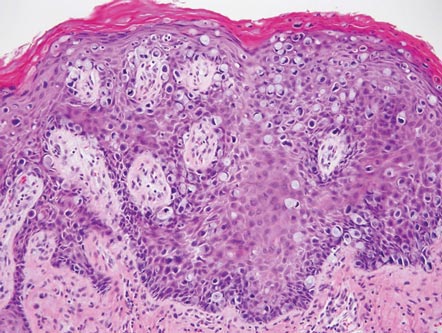

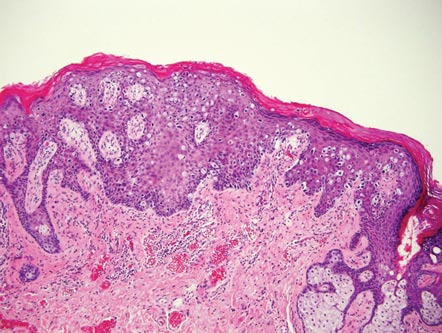

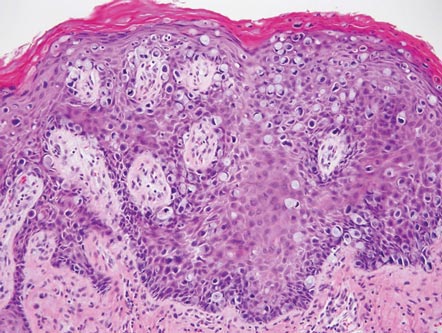

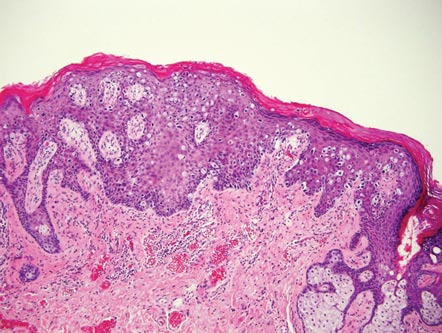

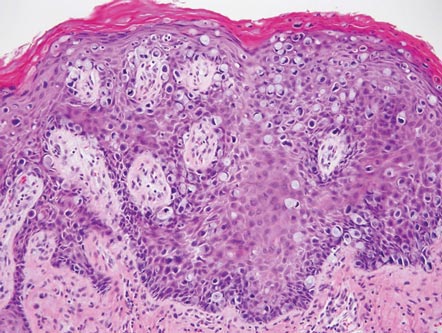

Galli-Galli disease and DDD are distinguishable by their histologic appearance. Both diseases show elongated fingerlike rete ridges and a thin suprapapillary epidermis. The basal projections often are described as bulbous or resembling antler horns.4 Galli-Galli disease can be differentiated from DDD by focal suprabasal acantholysis with minimal dyskeratosis (quiz images).5 Due to the genetic and clinical similarities, many consider GGD an acantholytic variant of DDD rather than its own entity. Indeed, some patients have shown acantholysis in one area of biopsy but not others.6

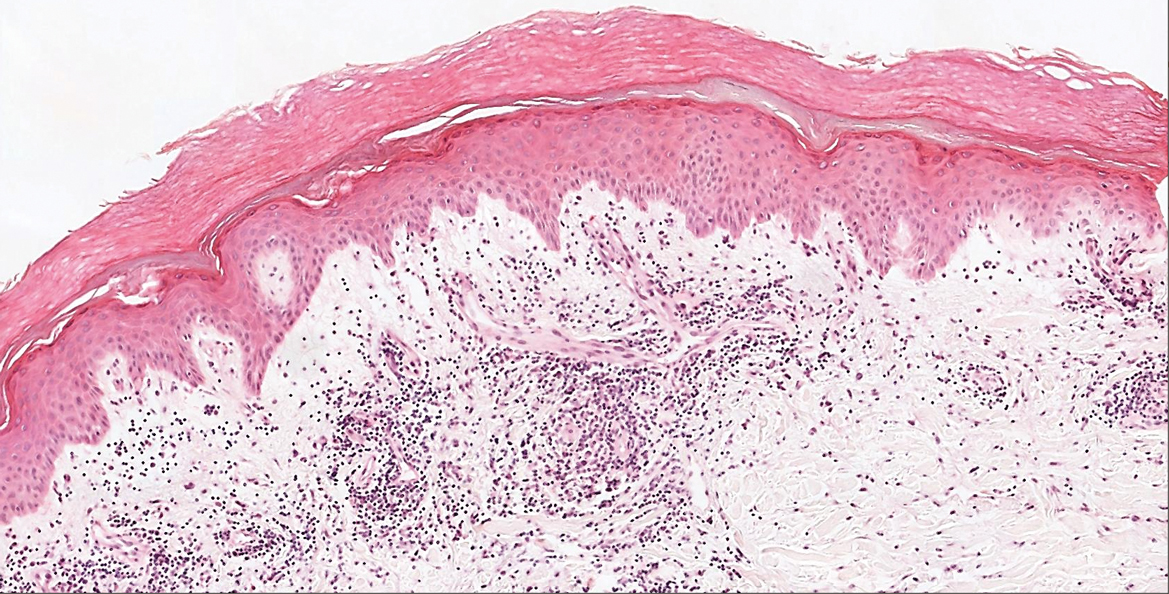

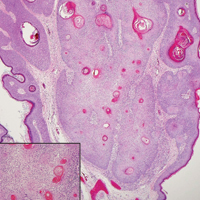

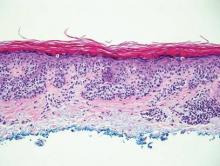

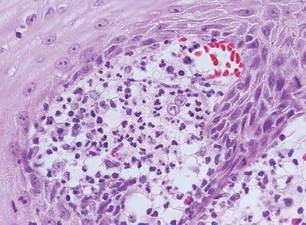

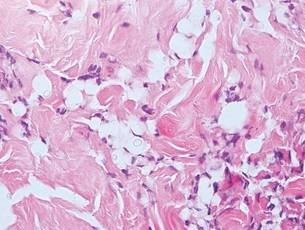

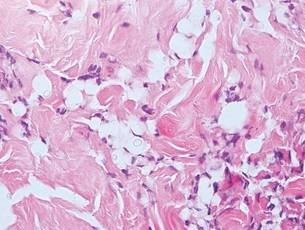

Hailey-Hailey disease (HHD)(also known as benign familial or benign chronic pemphigus) is an autosomaldominant disorder caused by mutation of the ATPase secretory pathway Ca2+ transporting 1 gene, ATP2C1. Clinically, patients tend to present at a wide age range with fragile flaccid vesicles that commonly develop on the neck, axillae, and groin. Histologically, the epidermis is acanthotic with a dilapidated brick wall– like appearance from a few persistent intercellular connections amid widespread acantholysis (Figure 1).7 Unlike in autoimmune pemphigus, direct immunofluorescence is negative, and acantholysis spares the adnexal structures. Hailey-Hailey disease does not involve reticulated hyperpigmentation or the elongated bulbous rete seen in GGD. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis is a rare, typically asymptomatic, hyperpigmented dermatosis. It presents as a conglomeration of scaly hyperpigmented macules or papillomatous papules that coalesce centrally and are reticulated toward the periphery.

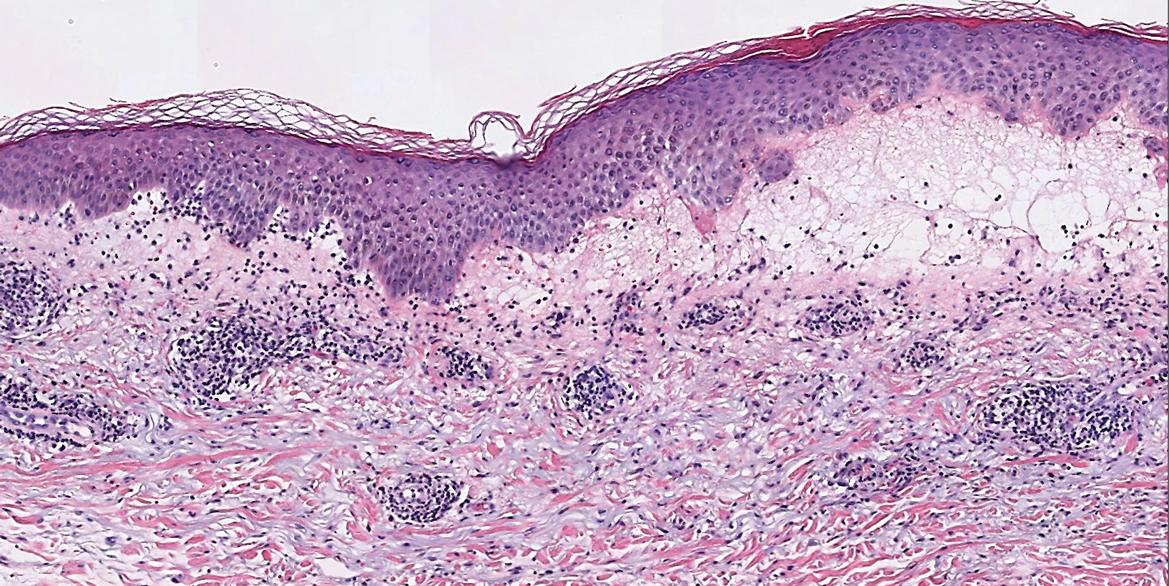

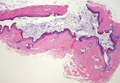

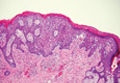

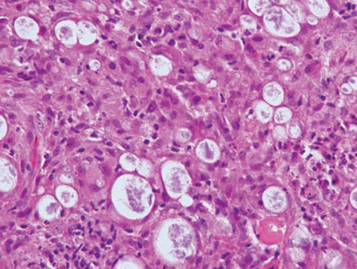

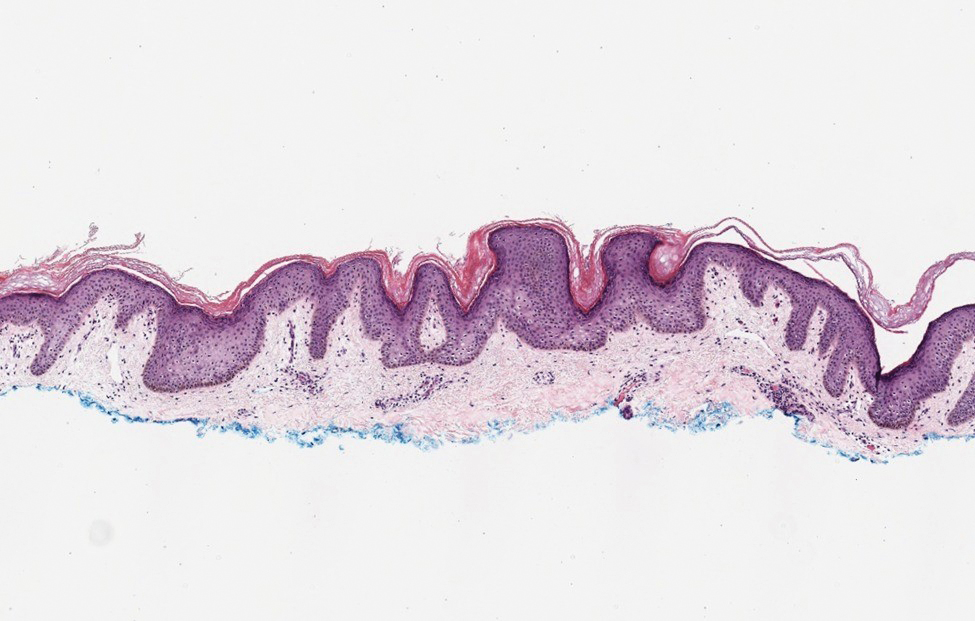

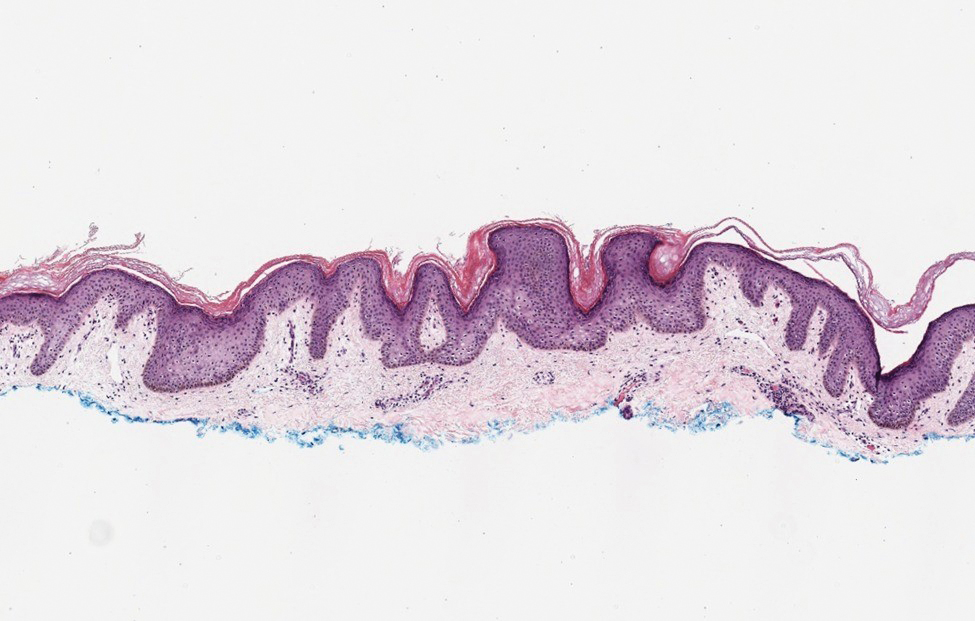

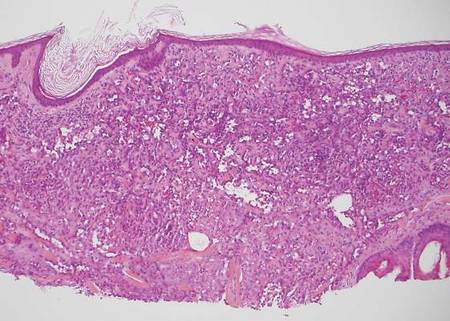

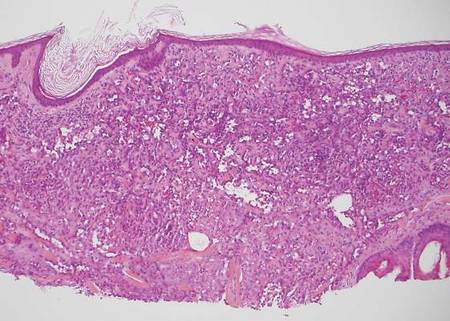

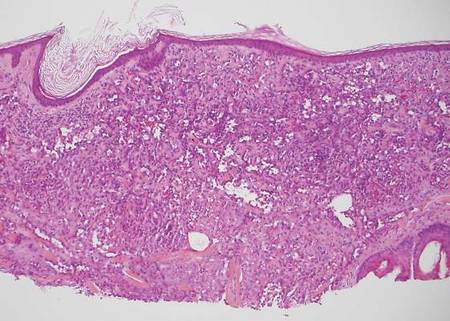

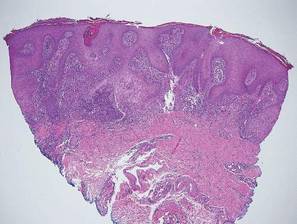

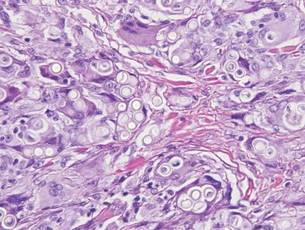

Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis most commonly is seen on the trunk, initially presenting in adolescents and young adults. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis is histologically similar to acanthosis nigricans. Histopathology will show hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, and minimal to no inflammatory infiltrate, with no elongated rete ridges or acantholysis (Figure 2).8

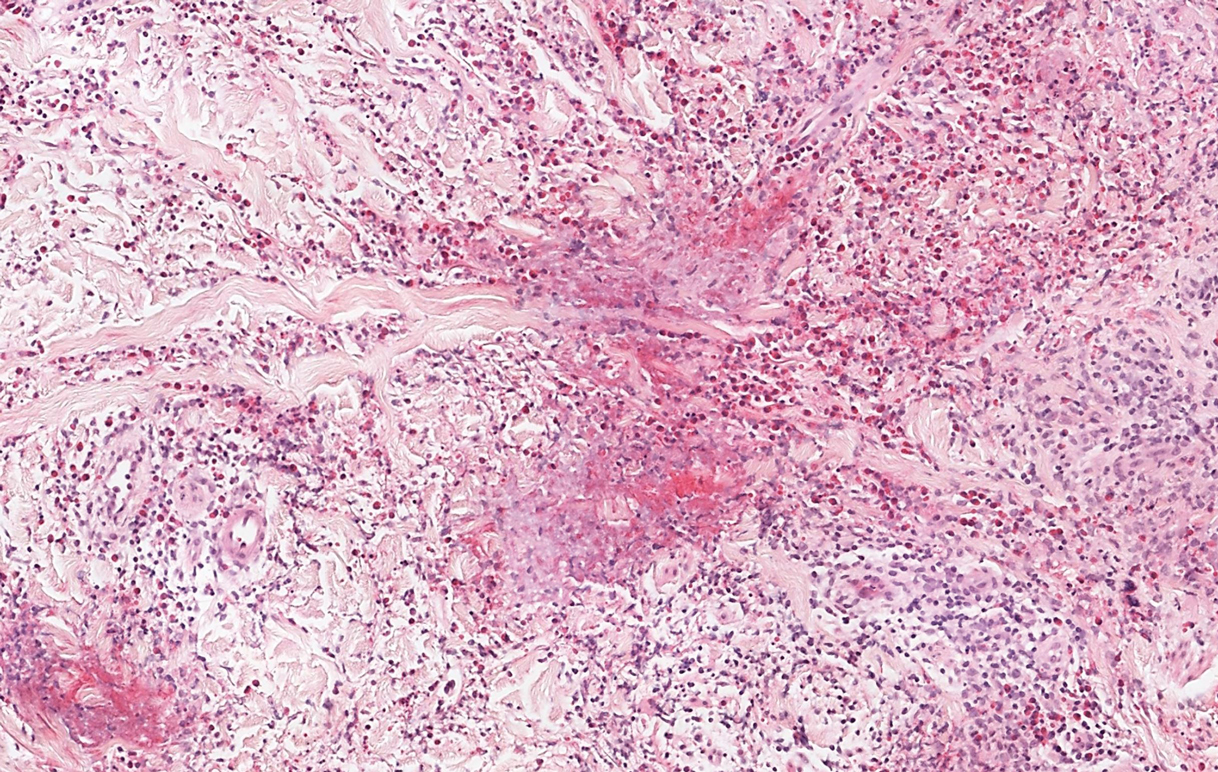

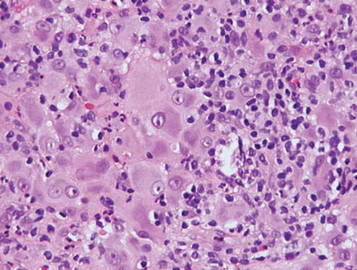

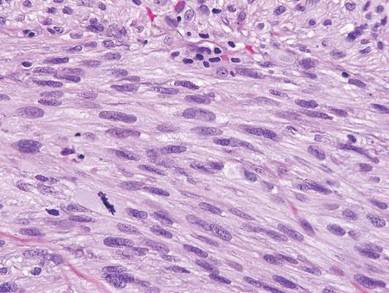

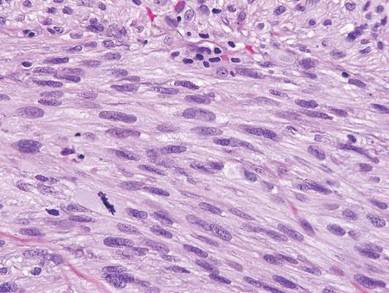

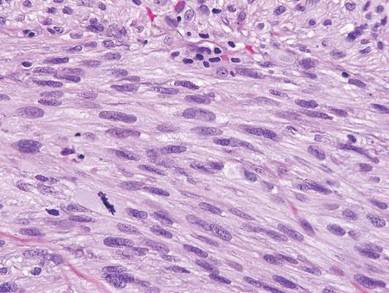

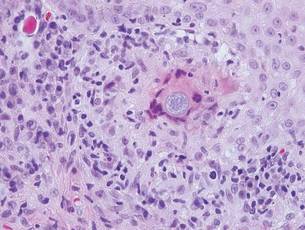

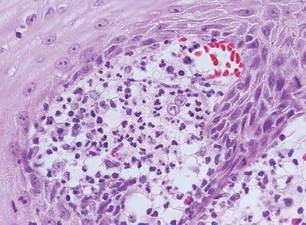

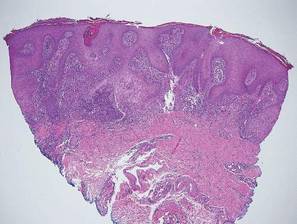

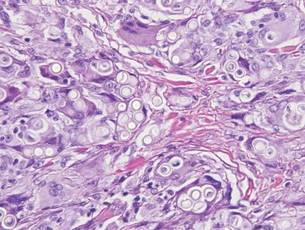

Pemphigus vulgaris is a blistering disease resulting from the development of autoantibodies against desmogleins 1 and 3. Similar to GGD, there is suprabasal acantholysis, which often results in a tombstonelike appearance consisting of separation between the basal layer cells of the epidermis but with maintained attachment to the underlying basement membrane zone. Unlike HHD, the acantholysis tends to involve the follicular epithelium in pemphigus vulgaris (Figure 3). Clinically, the blisters are positive for Nikolsky sign and can be both cutaneous or mucosal, commonly arising initially in the mouth during the fourth or fifth decades of life. Ruptured blisters can result in painful and hemorrhagic erosions.9 Direct immunofluorescence exhibits a classic chicken wire–like deposition of IgG and C3 between keratinocytes of the epidermis. Although sometimes difficult to appreciate, the deposition can be more prominent in the lower epidermis, in contrast to pemphigus foliaceus, which can have more prominent deposition in the upper epidermis.

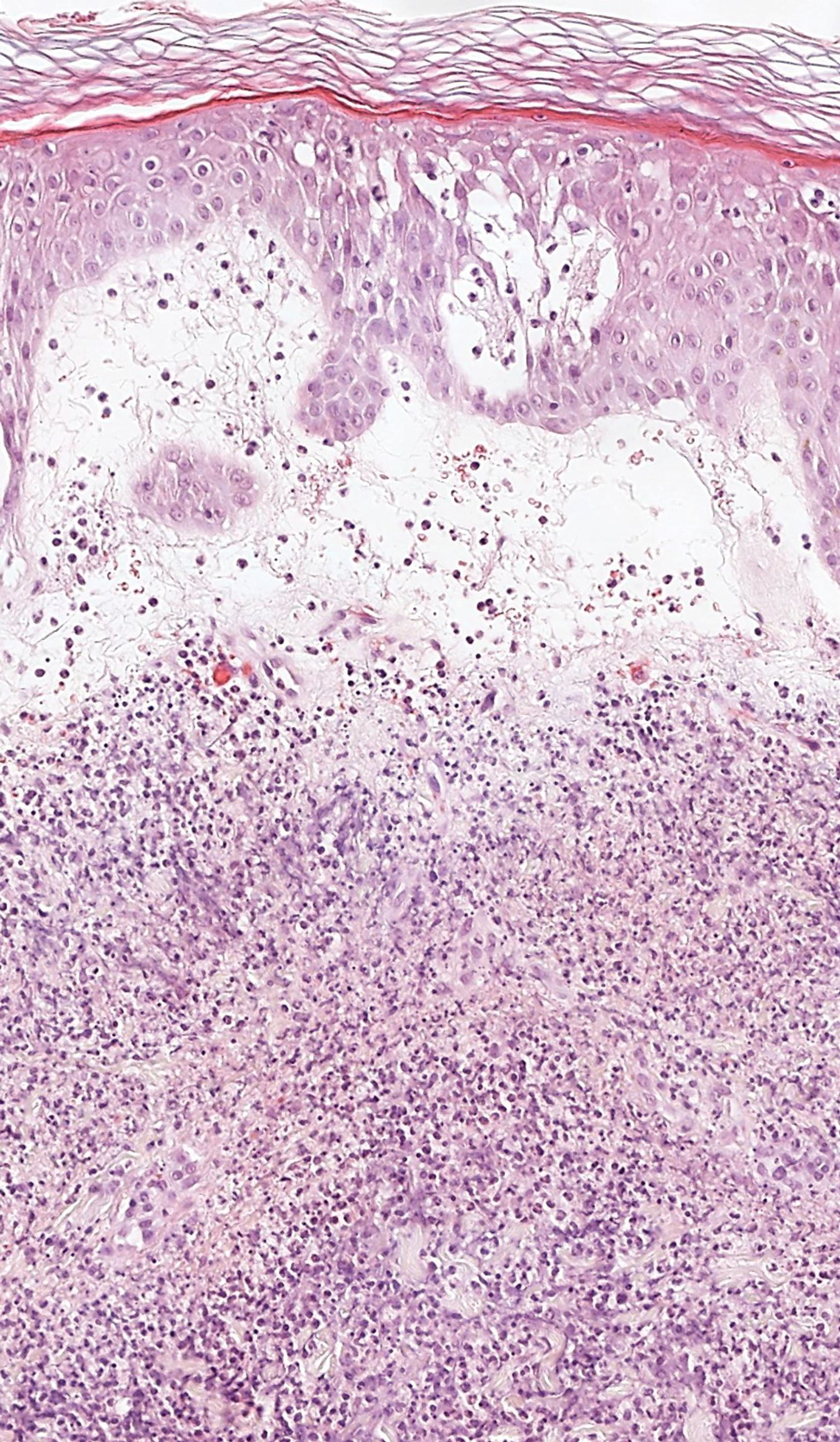

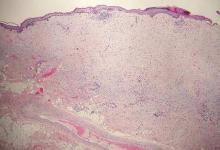

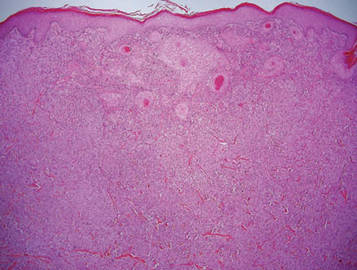

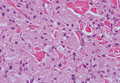

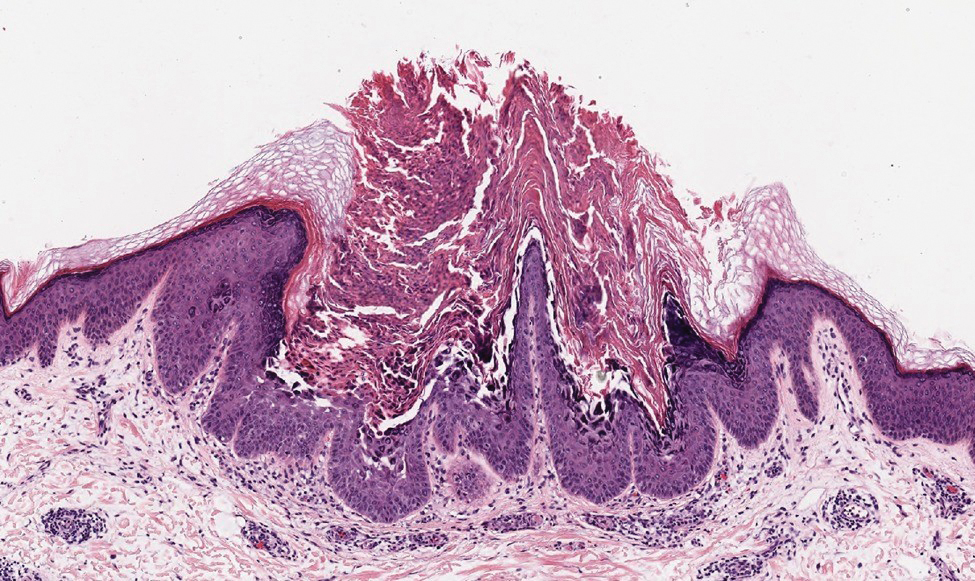

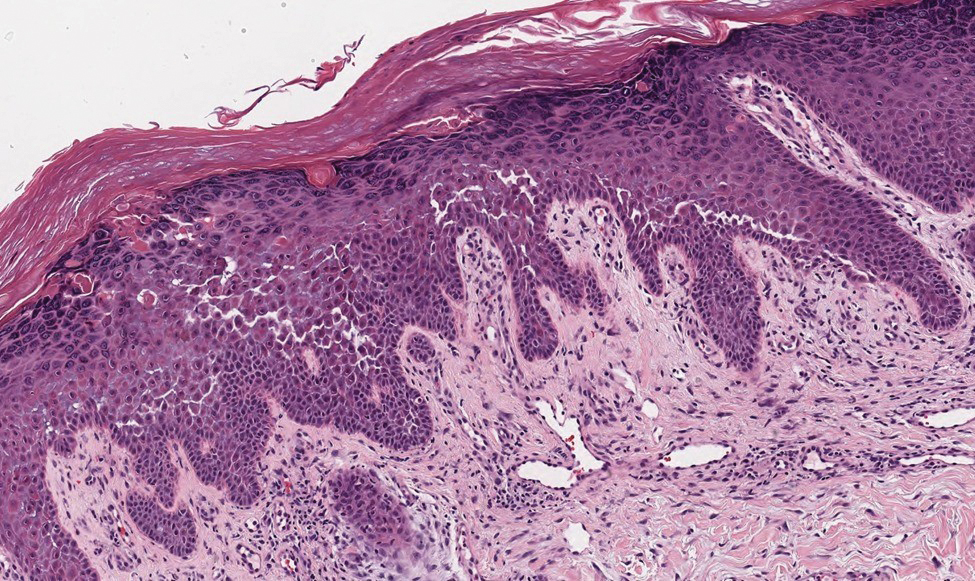

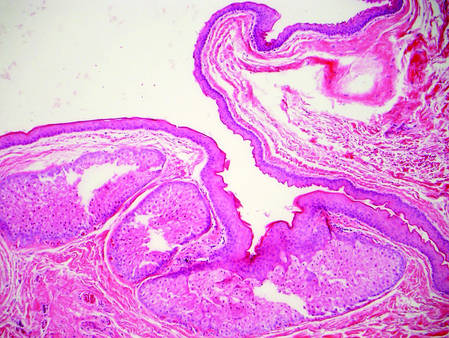

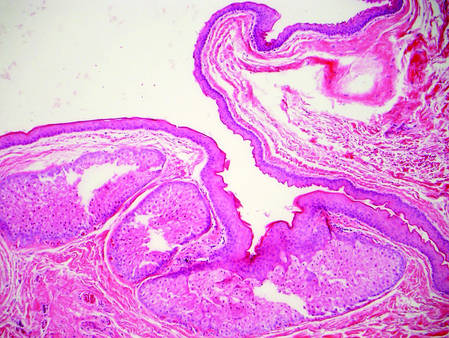

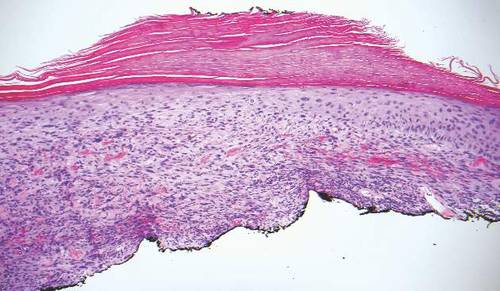

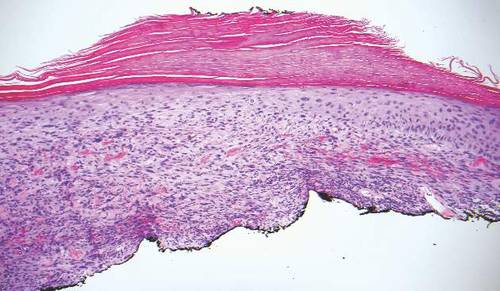

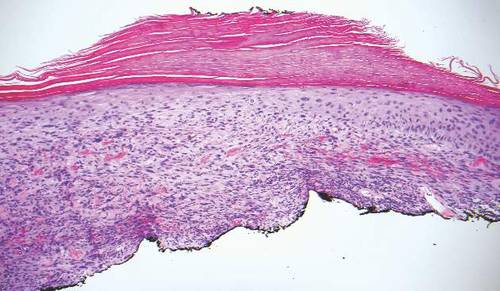

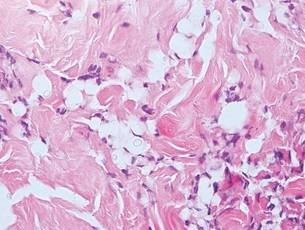

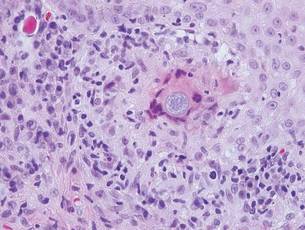

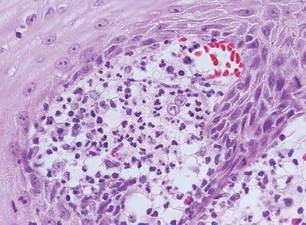

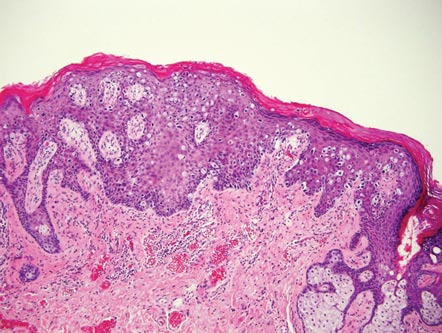

Darier disease (or dyskeratosis follicularis) is an autosomal-dominant genodermatosis caused by mutation of the ATPase sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ transporting 2 gene, ATP2A2. Clinically, this disorder arises in adolescents as red-brown, greasy, crusted papules in seborrheic areas that may coalesce into papillomatous clusters. Palmar punctate keratoses and pits also are common. Histologically, Darier disease can appear similar to GGD, as both can show acantholysis and dyskeratosis. Darier disease will tend to show more prominent dyskeratosis with corps ronds and grains, as well as thicker villilike projections of keratinocytes into the papillary dermis, in contrast to the thinner, fingerlike or bulbous projections that hang down from the epidermis in GGD (Figure 4).10

- Hanneken S, Rütten A, Eigelshoven S, et al. Morbus Galli-Galli. Hautarzt. 2013;64:282.

- Wilson NJ, Cole C, Kroboth K, et al. Mutations in POGLUT1 in Galli- Galli/Dowling-Degos disease. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:270-274.

- Ralser DJ, Basmanav FB, Tafazzoli A, et al. Mutations in γ-secretase subunit–encoding PSENEN underlie Dowling-Degos disease associated with acne inversa. J Clin Invest. 2017;127:1485-1490.

- Desai CA, Virmani N, Sakhiya J, et al. An uncommon presentation of Galli-Galli disease. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2016; 82:720-723.

- Joshi TP, Shaver S, Tschen J. Exacerbation of Galli-Galli disease following dialysis treatment: a case report and review of aggravating factors. Cureus. 2021;13:E15401.

- Muller CS, Pfohler C, Tilgen W. Changing a concept—controversy on the confusion spectrum of the reticulate pigmented disorders of the skin. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;36:44-48.

- Dai Y, Yu L, Wang Y, et al. Case report: a case of Hailey-Hailey disease mimicking condyloma acuminatum and a novel splice-site mutation of ATP2C1 gene. Front Genet. 2021;12:777630.

- Banjar TA, Abdulwahab RA, Al Hawsawi KA. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis of Gougerot and Carteaud: a case report and review of the literature. Cureus. 2022;14:E24557.

- Porro AM, Seque CA, Ferreira MCC, et al. Pemphigus vulgaris. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94:264-278.

- Bachar-Wikström E, Wikström JD. Darier disease—a multi-organ condition? Acta Derm Venereol. 2021;101:adv00430.

The Diagnosis: Galli-Galli Disease

Several cutaneous conditions can present as reticulated hyperpigmentation or keratotic papules. Although genetic testing can help identify some of these dermatoses, biopsy typically is sufficient for diagnosis, and genetic testing can be considered for more clinically challenging cases. In our case, the clinical evidence and histopathologic findings were diagnostic of Galli-Galli disease (GGD), an autosomal-dominant genodermatosis with incomplete penetrance. Our patient was unaware of any family members with a diagnosis of GGD; however, she reported a great uncle with similar clinical findings.

Galli-Galli disease is a rare allelic variant of Dowling- Degos disease (DDD), both caused by a loss-of-function mutation in the keratin 5 gene, KRT5. Both conditions present as reticulated papules distributed symmetrically in the flexural regions, most commonly the axillae and groin, but also as comedolike papules, typically in patients aged 30 to 50 years.1 Cutaneous lesions primarily are of cosmetic concern but can be extremely pruritic, especially for patients with GGD. Gene mutations in protein O-fucosyltransferase 1, POFUT1; protein O-glucosyltransferase 1, POGLUT1; and presenilin enhancer 2, PSENEN, also have been discovered in cases of DDD and GGD.2,3

Galli-Galli disease and DDD are distinguishable by their histologic appearance. Both diseases show elongated fingerlike rete ridges and a thin suprapapillary epidermis. The basal projections often are described as bulbous or resembling antler horns.4 Galli-Galli disease can be differentiated from DDD by focal suprabasal acantholysis with minimal dyskeratosis (quiz images).5 Due to the genetic and clinical similarities, many consider GGD an acantholytic variant of DDD rather than its own entity. Indeed, some patients have shown acantholysis in one area of biopsy but not others.6

Hailey-Hailey disease (HHD)(also known as benign familial or benign chronic pemphigus) is an autosomaldominant disorder caused by mutation of the ATPase secretory pathway Ca2+ transporting 1 gene, ATP2C1. Clinically, patients tend to present at a wide age range with fragile flaccid vesicles that commonly develop on the neck, axillae, and groin. Histologically, the epidermis is acanthotic with a dilapidated brick wall– like appearance from a few persistent intercellular connections amid widespread acantholysis (Figure 1).7 Unlike in autoimmune pemphigus, direct immunofluorescence is negative, and acantholysis spares the adnexal structures. Hailey-Hailey disease does not involve reticulated hyperpigmentation or the elongated bulbous rete seen in GGD. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis is a rare, typically asymptomatic, hyperpigmented dermatosis. It presents as a conglomeration of scaly hyperpigmented macules or papillomatous papules that coalesce centrally and are reticulated toward the periphery.

Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis most commonly is seen on the trunk, initially presenting in adolescents and young adults. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis is histologically similar to acanthosis nigricans. Histopathology will show hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, and minimal to no inflammatory infiltrate, with no elongated rete ridges or acantholysis (Figure 2).8

Pemphigus vulgaris is a blistering disease resulting from the development of autoantibodies against desmogleins 1 and 3. Similar to GGD, there is suprabasal acantholysis, which often results in a tombstonelike appearance consisting of separation between the basal layer cells of the epidermis but with maintained attachment to the underlying basement membrane zone. Unlike HHD, the acantholysis tends to involve the follicular epithelium in pemphigus vulgaris (Figure 3). Clinically, the blisters are positive for Nikolsky sign and can be both cutaneous or mucosal, commonly arising initially in the mouth during the fourth or fifth decades of life. Ruptured blisters can result in painful and hemorrhagic erosions.9 Direct immunofluorescence exhibits a classic chicken wire–like deposition of IgG and C3 between keratinocytes of the epidermis. Although sometimes difficult to appreciate, the deposition can be more prominent in the lower epidermis, in contrast to pemphigus foliaceus, which can have more prominent deposition in the upper epidermis.

Darier disease (or dyskeratosis follicularis) is an autosomal-dominant genodermatosis caused by mutation of the ATPase sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ transporting 2 gene, ATP2A2. Clinically, this disorder arises in adolescents as red-brown, greasy, crusted papules in seborrheic areas that may coalesce into papillomatous clusters. Palmar punctate keratoses and pits also are common. Histologically, Darier disease can appear similar to GGD, as both can show acantholysis and dyskeratosis. Darier disease will tend to show more prominent dyskeratosis with corps ronds and grains, as well as thicker villilike projections of keratinocytes into the papillary dermis, in contrast to the thinner, fingerlike or bulbous projections that hang down from the epidermis in GGD (Figure 4).10

The Diagnosis: Galli-Galli Disease

Several cutaneous conditions can present as reticulated hyperpigmentation or keratotic papules. Although genetic testing can help identify some of these dermatoses, biopsy typically is sufficient for diagnosis, and genetic testing can be considered for more clinically challenging cases. In our case, the clinical evidence and histopathologic findings were diagnostic of Galli-Galli disease (GGD), an autosomal-dominant genodermatosis with incomplete penetrance. Our patient was unaware of any family members with a diagnosis of GGD; however, she reported a great uncle with similar clinical findings.

Galli-Galli disease is a rare allelic variant of Dowling- Degos disease (DDD), both caused by a loss-of-function mutation in the keratin 5 gene, KRT5. Both conditions present as reticulated papules distributed symmetrically in the flexural regions, most commonly the axillae and groin, but also as comedolike papules, typically in patients aged 30 to 50 years.1 Cutaneous lesions primarily are of cosmetic concern but can be extremely pruritic, especially for patients with GGD. Gene mutations in protein O-fucosyltransferase 1, POFUT1; protein O-glucosyltransferase 1, POGLUT1; and presenilin enhancer 2, PSENEN, also have been discovered in cases of DDD and GGD.2,3

Galli-Galli disease and DDD are distinguishable by their histologic appearance. Both diseases show elongated fingerlike rete ridges and a thin suprapapillary epidermis. The basal projections often are described as bulbous or resembling antler horns.4 Galli-Galli disease can be differentiated from DDD by focal suprabasal acantholysis with minimal dyskeratosis (quiz images).5 Due to the genetic and clinical similarities, many consider GGD an acantholytic variant of DDD rather than its own entity. Indeed, some patients have shown acantholysis in one area of biopsy but not others.6

Hailey-Hailey disease (HHD)(also known as benign familial or benign chronic pemphigus) is an autosomaldominant disorder caused by mutation of the ATPase secretory pathway Ca2+ transporting 1 gene, ATP2C1. Clinically, patients tend to present at a wide age range with fragile flaccid vesicles that commonly develop on the neck, axillae, and groin. Histologically, the epidermis is acanthotic with a dilapidated brick wall– like appearance from a few persistent intercellular connections amid widespread acantholysis (Figure 1).7 Unlike in autoimmune pemphigus, direct immunofluorescence is negative, and acantholysis spares the adnexal structures. Hailey-Hailey disease does not involve reticulated hyperpigmentation or the elongated bulbous rete seen in GGD. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis is a rare, typically asymptomatic, hyperpigmented dermatosis. It presents as a conglomeration of scaly hyperpigmented macules or papillomatous papules that coalesce centrally and are reticulated toward the periphery.

Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis most commonly is seen on the trunk, initially presenting in adolescents and young adults. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis is histologically similar to acanthosis nigricans. Histopathology will show hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, and minimal to no inflammatory infiltrate, with no elongated rete ridges or acantholysis (Figure 2).8

Pemphigus vulgaris is a blistering disease resulting from the development of autoantibodies against desmogleins 1 and 3. Similar to GGD, there is suprabasal acantholysis, which often results in a tombstonelike appearance consisting of separation between the basal layer cells of the epidermis but with maintained attachment to the underlying basement membrane zone. Unlike HHD, the acantholysis tends to involve the follicular epithelium in pemphigus vulgaris (Figure 3). Clinically, the blisters are positive for Nikolsky sign and can be both cutaneous or mucosal, commonly arising initially in the mouth during the fourth or fifth decades of life. Ruptured blisters can result in painful and hemorrhagic erosions.9 Direct immunofluorescence exhibits a classic chicken wire–like deposition of IgG and C3 between keratinocytes of the epidermis. Although sometimes difficult to appreciate, the deposition can be more prominent in the lower epidermis, in contrast to pemphigus foliaceus, which can have more prominent deposition in the upper epidermis.

Darier disease (or dyskeratosis follicularis) is an autosomal-dominant genodermatosis caused by mutation of the ATPase sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ transporting 2 gene, ATP2A2. Clinically, this disorder arises in adolescents as red-brown, greasy, crusted papules in seborrheic areas that may coalesce into papillomatous clusters. Palmar punctate keratoses and pits also are common. Histologically, Darier disease can appear similar to GGD, as both can show acantholysis and dyskeratosis. Darier disease will tend to show more prominent dyskeratosis with corps ronds and grains, as well as thicker villilike projections of keratinocytes into the papillary dermis, in contrast to the thinner, fingerlike or bulbous projections that hang down from the epidermis in GGD (Figure 4).10

- Hanneken S, Rütten A, Eigelshoven S, et al. Morbus Galli-Galli. Hautarzt. 2013;64:282.

- Wilson NJ, Cole C, Kroboth K, et al. Mutations in POGLUT1 in Galli- Galli/Dowling-Degos disease. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:270-274.

- Ralser DJ, Basmanav FB, Tafazzoli A, et al. Mutations in γ-secretase subunit–encoding PSENEN underlie Dowling-Degos disease associated with acne inversa. J Clin Invest. 2017;127:1485-1490.

- Desai CA, Virmani N, Sakhiya J, et al. An uncommon presentation of Galli-Galli disease. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2016; 82:720-723.

- Joshi TP, Shaver S, Tschen J. Exacerbation of Galli-Galli disease following dialysis treatment: a case report and review of aggravating factors. Cureus. 2021;13:E15401.

- Muller CS, Pfohler C, Tilgen W. Changing a concept—controversy on the confusion spectrum of the reticulate pigmented disorders of the skin. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;36:44-48.

- Dai Y, Yu L, Wang Y, et al. Case report: a case of Hailey-Hailey disease mimicking condyloma acuminatum and a novel splice-site mutation of ATP2C1 gene. Front Genet. 2021;12:777630.

- Banjar TA, Abdulwahab RA, Al Hawsawi KA. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis of Gougerot and Carteaud: a case report and review of the literature. Cureus. 2022;14:E24557.

- Porro AM, Seque CA, Ferreira MCC, et al. Pemphigus vulgaris. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94:264-278.

- Bachar-Wikström E, Wikström JD. Darier disease—a multi-organ condition? Acta Derm Venereol. 2021;101:adv00430.

- Hanneken S, Rütten A, Eigelshoven S, et al. Morbus Galli-Galli. Hautarzt. 2013;64:282.

- Wilson NJ, Cole C, Kroboth K, et al. Mutations in POGLUT1 in Galli- Galli/Dowling-Degos disease. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:270-274.

- Ralser DJ, Basmanav FB, Tafazzoli A, et al. Mutations in γ-secretase subunit–encoding PSENEN underlie Dowling-Degos disease associated with acne inversa. J Clin Invest. 2017;127:1485-1490.

- Desai CA, Virmani N, Sakhiya J, et al. An uncommon presentation of Galli-Galli disease. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2016; 82:720-723.

- Joshi TP, Shaver S, Tschen J. Exacerbation of Galli-Galli disease following dialysis treatment: a case report and review of aggravating factors. Cureus. 2021;13:E15401.

- Muller CS, Pfohler C, Tilgen W. Changing a concept—controversy on the confusion spectrum of the reticulate pigmented disorders of the skin. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;36:44-48.

- Dai Y, Yu L, Wang Y, et al. Case report: a case of Hailey-Hailey disease mimicking condyloma acuminatum and a novel splice-site mutation of ATP2C1 gene. Front Genet. 2021;12:777630.

- Banjar TA, Abdulwahab RA, Al Hawsawi KA. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis of Gougerot and Carteaud: a case report and review of the literature. Cureus. 2022;14:E24557.

- Porro AM, Seque CA, Ferreira MCC, et al. Pemphigus vulgaris. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94:264-278.

- Bachar-Wikström E, Wikström JD. Darier disease—a multi-organ condition? Acta Derm Venereol. 2021;101:adv00430.

A 37-year-old woman presented with multiple hyperkeratotic small papules in the axillae and groin of 1 year’s duration. She reported pruritus and occasional sleep disruption. Subtle background reticulated hyperpigmentation was present. The patient reported that she had a great uncle with similar findings.

Tender, Diffuse, Edematous, and Erythematous Papules on the Face, Neck, Chest, and Extremities

The Diagnosis: Sweet Syndrome

Sweet syndrome, alternatively known as acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis, typically presents with variably tender, erythematous papules, plaques, or nodules in middle-aged adults.1 Systemic symptoms such as fever, fatigue, and arthralgia often accompany these cutaneous findings.1,2 Although the pathophysiology has not been fully elucidated, this syndrome frequently is associated with infections, especially upper respiratory illnesses; medications; and malignancies. Among cases of malignancy-associated Sweet syndrome, hematologic malignancies, particularly acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome, are more common than solid organ malignancies.1,2 Sweet syndrome may precede the associated malignancy by several months; thus, patients without an identifiable trigger for Sweet syndrome should be closely followed.2 Treatment with systemic steroids typically is effective.1,3 Typical histologic features include papillary dermal edema and a brisk neutrophilic infiltrate in the superficial to mid dermis (quiz image).4 Overlying epidermal spongiosis with or without vesiculation also can be seen.4 Leukocytoclasia and endothelial swelling without fibrinoid necrosis are typical, though full-blown leukocytoclastic vasculitis can be seen.3,4 A histiocytoid variant also has been described in which the dermal infiltrate is composed of mononuclear cells reminiscent of histiocytes that are thought to be immature cells of myeloid origin. This variant histologically can simulate leukemia cutis.5

Perniosis, also known as chilblains, typically presents with red to violaceous macules or papules on acral sites, particularly the distal fingers and toes.6,7 It tends to affect young women more frequently than other demographic groups. Although the pathophysiology is not fully understood, perniosis is thought to represent an abnormal inflammatory response to cold environmental conditions. It can occur as an idiopathic disorder or in association with various systemic illnesses including lupus erythematosus.6,7 The typical histologic findings include papillary dermal edema and a lymphocytic infiltrate in the superficial to deep dermis, often with perivascular and perieccrine accentuation (Figure 1).3,6 Other less common microscopic findings include sparse keratinocyte necrosis, basal layer vacuolar change, swelling of endothelial cells, and lymphocytic vasculitis.6 The lesions typically resolve spontaneously within a few weeks, but in some cases they may be chronic.3

Polymorphous light eruption, a common photodermatosis induced by UV light exposure, typically presents in adolescence or early adulthood with a female predominance. Patients usually develop this pruritic rash on sun-exposed skin other than the face and dorsal aspects of the hands in the spring or early summer upon increased sun exposure after the winter season.3,8 Consistent sunlight exposure throughout the summer months results in decreased flares. Various cutaneous morphologies including papules, vesicles, and plaques can be seen.3,8 Histologic findings include papillary dermal edema and a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate in the superficial to deep dermis (Figure 2).4

Tinea corporis, a superficial cutaneous dermatophyte infection, typically presents as annular scaly plaques with central clearing. Vesicles and pustules also can be seen.3 The diagnosis can be confirmed via fungal culture, identification of hyphae on microscopic examination of skin scrapings using potassium hydroxide, or cutaneous biopsy. Histologic clues to diagnosis include a "compact stratum corneum (either uniform or forming a layer beneath a basket weave stratum corneum), parakeratosis, mild spongiosis, and neutrophils in the stratum corneum" (Figure 3).9 Papillary dermal edema also may be present, though this finding less commonly is reported.9,10 Because fungal hyphae can be difficult to identify on hematoxylin and eosin-stained slides, special stains such as periodic acid-Schiff or Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver may be helpful.9 These infections are managed with topical or oral antifungal medications.

Wells syndrome, also known as eosinophilic cellulitis, presents with an acute eruption that can clinically resemble bacterial cellulitis.3 It has been described in children and adults with various clinical morphologies including plaques, bullae, papulovesicles, and papulonodules. Peripheral eosinophilia may be present.11 The clinical lesions usually resolve spontaneously in a few weeks to months, but recurrences are typical.3,11 Histologic findings include papillary dermal edema with or without subepidermal bulla formation and epidermal spongiosis as well as a mixed inflammatory infiltrate with a predominance of eosinophils and flame figures (Figure 4).4 Flame figures are collagen fibers coated with major basic protein and other constituents of degranulated eosinophils.3 Although flame figures often are present in Wells syndrome, they are not specific to this condition.3,4 Some consider Wells syndrome an exaggerated reaction pattern rather than a specific entity.3

- Rochet N, Chavan R, Cappel M, et al. Sweet syndrome: clinical presentation, associations, and response to treatment in 77 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:557-564.

- Marcoval J, Martín-Callizo C, Valentí-Medina F, et al. Sweet syndrome: long-term follow-up of 138 patients. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2016;41:741-746.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Shaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2012.

- Calonje JE, Brenn T, Lazar AJ, et al. McKee's Pathology of the Skin. 4th ed. Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

- Alegría-Landa V, Rodríguez-Pinilla S, Santos-Briz A, et al. Clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular features of histiocytoid Sweet syndrome. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:651-659.

- Boada A, Bielsa I, Fernández-Figueras M, et al. Perniosis: clinical and histopathological analysis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:19-23.

- Takci Z, Vahaboglu G, Eksioglu H. Epidemiological patterns of perniosis, and its association with systemic disorder. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37:844-849.

- Gruber-Wackernagel A, Byrne S, Wolf P. Polymorphous light eruption: clinic aspects and pathogenesis. Dermatol Clin. 2014;32:315-334.

- Elbendary A, Valdebran M, Gad A, et al. When to suspect tinea; a histopathologic study of 103 cases of PAS-positive tinea. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;46:852-857.

- Hoss D, Berke A, Kerr P, et al. Prominent papillary dermal edema in dermatophytosis (tinea corporis). J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:237-242.

- Caputo R, Marzano A, Vezzoli P, et al. Wells syndrome in adults and children: a report of 19 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1157-1161.

The Diagnosis: Sweet Syndrome

Sweet syndrome, alternatively known as acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis, typically presents with variably tender, erythematous papules, plaques, or nodules in middle-aged adults.1 Systemic symptoms such as fever, fatigue, and arthralgia often accompany these cutaneous findings.1,2 Although the pathophysiology has not been fully elucidated, this syndrome frequently is associated with infections, especially upper respiratory illnesses; medications; and malignancies. Among cases of malignancy-associated Sweet syndrome, hematologic malignancies, particularly acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome, are more common than solid organ malignancies.1,2 Sweet syndrome may precede the associated malignancy by several months; thus, patients without an identifiable trigger for Sweet syndrome should be closely followed.2 Treatment with systemic steroids typically is effective.1,3 Typical histologic features include papillary dermal edema and a brisk neutrophilic infiltrate in the superficial to mid dermis (quiz image).4 Overlying epidermal spongiosis with or without vesiculation also can be seen.4 Leukocytoclasia and endothelial swelling without fibrinoid necrosis are typical, though full-blown leukocytoclastic vasculitis can be seen.3,4 A histiocytoid variant also has been described in which the dermal infiltrate is composed of mononuclear cells reminiscent of histiocytes that are thought to be immature cells of myeloid origin. This variant histologically can simulate leukemia cutis.5

Perniosis, also known as chilblains, typically presents with red to violaceous macules or papules on acral sites, particularly the distal fingers and toes.6,7 It tends to affect young women more frequently than other demographic groups. Although the pathophysiology is not fully understood, perniosis is thought to represent an abnormal inflammatory response to cold environmental conditions. It can occur as an idiopathic disorder or in association with various systemic illnesses including lupus erythematosus.6,7 The typical histologic findings include papillary dermal edema and a lymphocytic infiltrate in the superficial to deep dermis, often with perivascular and perieccrine accentuation (Figure 1).3,6 Other less common microscopic findings include sparse keratinocyte necrosis, basal layer vacuolar change, swelling of endothelial cells, and lymphocytic vasculitis.6 The lesions typically resolve spontaneously within a few weeks, but in some cases they may be chronic.3

Polymorphous light eruption, a common photodermatosis induced by UV light exposure, typically presents in adolescence or early adulthood with a female predominance. Patients usually develop this pruritic rash on sun-exposed skin other than the face and dorsal aspects of the hands in the spring or early summer upon increased sun exposure after the winter season.3,8 Consistent sunlight exposure throughout the summer months results in decreased flares. Various cutaneous morphologies including papules, vesicles, and plaques can be seen.3,8 Histologic findings include papillary dermal edema and a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate in the superficial to deep dermis (Figure 2).4

Tinea corporis, a superficial cutaneous dermatophyte infection, typically presents as annular scaly plaques with central clearing. Vesicles and pustules also can be seen.3 The diagnosis can be confirmed via fungal culture, identification of hyphae on microscopic examination of skin scrapings using potassium hydroxide, or cutaneous biopsy. Histologic clues to diagnosis include a "compact stratum corneum (either uniform or forming a layer beneath a basket weave stratum corneum), parakeratosis, mild spongiosis, and neutrophils in the stratum corneum" (Figure 3).9 Papillary dermal edema also may be present, though this finding less commonly is reported.9,10 Because fungal hyphae can be difficult to identify on hematoxylin and eosin-stained slides, special stains such as periodic acid-Schiff or Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver may be helpful.9 These infections are managed with topical or oral antifungal medications.

Wells syndrome, also known as eosinophilic cellulitis, presents with an acute eruption that can clinically resemble bacterial cellulitis.3 It has been described in children and adults with various clinical morphologies including plaques, bullae, papulovesicles, and papulonodules. Peripheral eosinophilia may be present.11 The clinical lesions usually resolve spontaneously in a few weeks to months, but recurrences are typical.3,11 Histologic findings include papillary dermal edema with or without subepidermal bulla formation and epidermal spongiosis as well as a mixed inflammatory infiltrate with a predominance of eosinophils and flame figures (Figure 4).4 Flame figures are collagen fibers coated with major basic protein and other constituents of degranulated eosinophils.3 Although flame figures often are present in Wells syndrome, they are not specific to this condition.3,4 Some consider Wells syndrome an exaggerated reaction pattern rather than a specific entity.3

The Diagnosis: Sweet Syndrome

Sweet syndrome, alternatively known as acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis, typically presents with variably tender, erythematous papules, plaques, or nodules in middle-aged adults.1 Systemic symptoms such as fever, fatigue, and arthralgia often accompany these cutaneous findings.1,2 Although the pathophysiology has not been fully elucidated, this syndrome frequently is associated with infections, especially upper respiratory illnesses; medications; and malignancies. Among cases of malignancy-associated Sweet syndrome, hematologic malignancies, particularly acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome, are more common than solid organ malignancies.1,2 Sweet syndrome may precede the associated malignancy by several months; thus, patients without an identifiable trigger for Sweet syndrome should be closely followed.2 Treatment with systemic steroids typically is effective.1,3 Typical histologic features include papillary dermal edema and a brisk neutrophilic infiltrate in the superficial to mid dermis (quiz image).4 Overlying epidermal spongiosis with or without vesiculation also can be seen.4 Leukocytoclasia and endothelial swelling without fibrinoid necrosis are typical, though full-blown leukocytoclastic vasculitis can be seen.3,4 A histiocytoid variant also has been described in which the dermal infiltrate is composed of mononuclear cells reminiscent of histiocytes that are thought to be immature cells of myeloid origin. This variant histologically can simulate leukemia cutis.5

Perniosis, also known as chilblains, typically presents with red to violaceous macules or papules on acral sites, particularly the distal fingers and toes.6,7 It tends to affect young women more frequently than other demographic groups. Although the pathophysiology is not fully understood, perniosis is thought to represent an abnormal inflammatory response to cold environmental conditions. It can occur as an idiopathic disorder or in association with various systemic illnesses including lupus erythematosus.6,7 The typical histologic findings include papillary dermal edema and a lymphocytic infiltrate in the superficial to deep dermis, often with perivascular and perieccrine accentuation (Figure 1).3,6 Other less common microscopic findings include sparse keratinocyte necrosis, basal layer vacuolar change, swelling of endothelial cells, and lymphocytic vasculitis.6 The lesions typically resolve spontaneously within a few weeks, but in some cases they may be chronic.3

Polymorphous light eruption, a common photodermatosis induced by UV light exposure, typically presents in adolescence or early adulthood with a female predominance. Patients usually develop this pruritic rash on sun-exposed skin other than the face and dorsal aspects of the hands in the spring or early summer upon increased sun exposure after the winter season.3,8 Consistent sunlight exposure throughout the summer months results in decreased flares. Various cutaneous morphologies including papules, vesicles, and plaques can be seen.3,8 Histologic findings include papillary dermal edema and a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate in the superficial to deep dermis (Figure 2).4

Tinea corporis, a superficial cutaneous dermatophyte infection, typically presents as annular scaly plaques with central clearing. Vesicles and pustules also can be seen.3 The diagnosis can be confirmed via fungal culture, identification of hyphae on microscopic examination of skin scrapings using potassium hydroxide, or cutaneous biopsy. Histologic clues to diagnosis include a "compact stratum corneum (either uniform or forming a layer beneath a basket weave stratum corneum), parakeratosis, mild spongiosis, and neutrophils in the stratum corneum" (Figure 3).9 Papillary dermal edema also may be present, though this finding less commonly is reported.9,10 Because fungal hyphae can be difficult to identify on hematoxylin and eosin-stained slides, special stains such as periodic acid-Schiff or Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver may be helpful.9 These infections are managed with topical or oral antifungal medications.

Wells syndrome, also known as eosinophilic cellulitis, presents with an acute eruption that can clinically resemble bacterial cellulitis.3 It has been described in children and adults with various clinical morphologies including plaques, bullae, papulovesicles, and papulonodules. Peripheral eosinophilia may be present.11 The clinical lesions usually resolve spontaneously in a few weeks to months, but recurrences are typical.3,11 Histologic findings include papillary dermal edema with or without subepidermal bulla formation and epidermal spongiosis as well as a mixed inflammatory infiltrate with a predominance of eosinophils and flame figures (Figure 4).4 Flame figures are collagen fibers coated with major basic protein and other constituents of degranulated eosinophils.3 Although flame figures often are present in Wells syndrome, they are not specific to this condition.3,4 Some consider Wells syndrome an exaggerated reaction pattern rather than a specific entity.3

- Rochet N, Chavan R, Cappel M, et al. Sweet syndrome: clinical presentation, associations, and response to treatment in 77 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:557-564.

- Marcoval J, Martín-Callizo C, Valentí-Medina F, et al. Sweet syndrome: long-term follow-up of 138 patients. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2016;41:741-746.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Shaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2012.

- Calonje JE, Brenn T, Lazar AJ, et al. McKee's Pathology of the Skin. 4th ed. Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

- Alegría-Landa V, Rodríguez-Pinilla S, Santos-Briz A, et al. Clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular features of histiocytoid Sweet syndrome. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:651-659.

- Boada A, Bielsa I, Fernández-Figueras M, et al. Perniosis: clinical and histopathological analysis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:19-23.

- Takci Z, Vahaboglu G, Eksioglu H. Epidemiological patterns of perniosis, and its association with systemic disorder. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37:844-849.

- Gruber-Wackernagel A, Byrne S, Wolf P. Polymorphous light eruption: clinic aspects and pathogenesis. Dermatol Clin. 2014;32:315-334.

- Elbendary A, Valdebran M, Gad A, et al. When to suspect tinea; a histopathologic study of 103 cases of PAS-positive tinea. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;46:852-857.

- Hoss D, Berke A, Kerr P, et al. Prominent papillary dermal edema in dermatophytosis (tinea corporis). J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:237-242.

- Caputo R, Marzano A, Vezzoli P, et al. Wells syndrome in adults and children: a report of 19 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1157-1161.

- Rochet N, Chavan R, Cappel M, et al. Sweet syndrome: clinical presentation, associations, and response to treatment in 77 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:557-564.

- Marcoval J, Martín-Callizo C, Valentí-Medina F, et al. Sweet syndrome: long-term follow-up of 138 patients. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2016;41:741-746.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Shaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2012.

- Calonje JE, Brenn T, Lazar AJ, et al. McKee's Pathology of the Skin. 4th ed. Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

- Alegría-Landa V, Rodríguez-Pinilla S, Santos-Briz A, et al. Clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular features of histiocytoid Sweet syndrome. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:651-659.

- Boada A, Bielsa I, Fernández-Figueras M, et al. Perniosis: clinical and histopathological analysis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:19-23.

- Takci Z, Vahaboglu G, Eksioglu H. Epidemiological patterns of perniosis, and its association with systemic disorder. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37:844-849.

- Gruber-Wackernagel A, Byrne S, Wolf P. Polymorphous light eruption: clinic aspects and pathogenesis. Dermatol Clin. 2014;32:315-334.

- Elbendary A, Valdebran M, Gad A, et al. When to suspect tinea; a histopathologic study of 103 cases of PAS-positive tinea. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;46:852-857.

- Hoss D, Berke A, Kerr P, et al. Prominent papillary dermal edema in dermatophytosis (tinea corporis). J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:237-242.

- Caputo R, Marzano A, Vezzoli P, et al. Wells syndrome in adults and children: a report of 19 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1157-1161.

A 62-year-old woman presented with a tender diffuse eruption of erythematous and edematous papules and plaques on the face, neck, chest, and extremities, some appearing vesiculopustular.

Verrucoid Lesion on the Eyelid

The Diagnosis: Inverted Follicular Keratosis

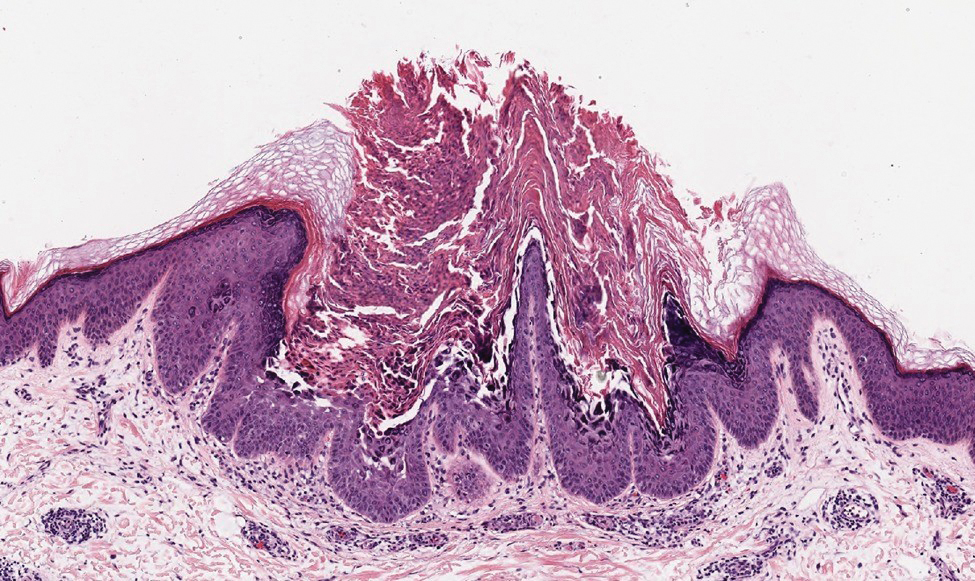

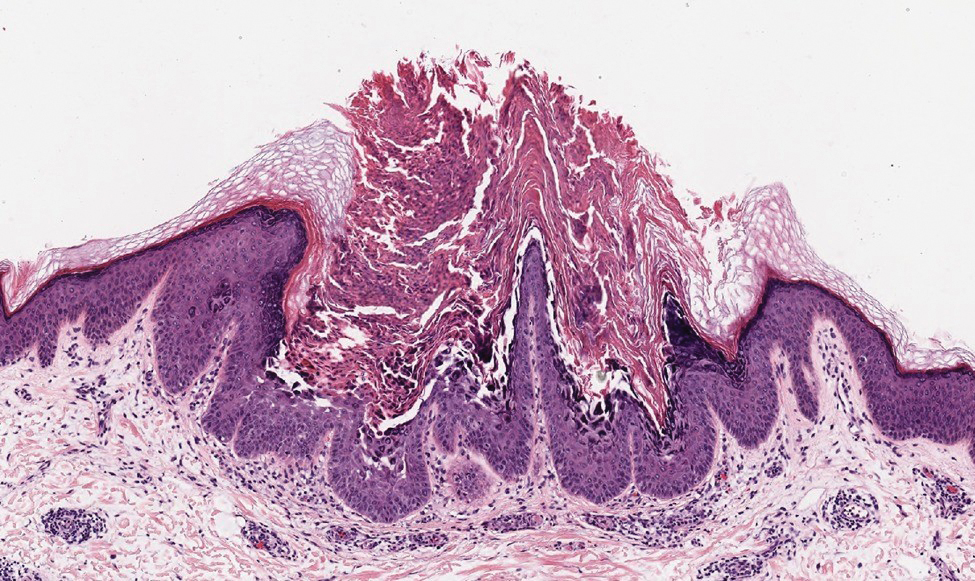

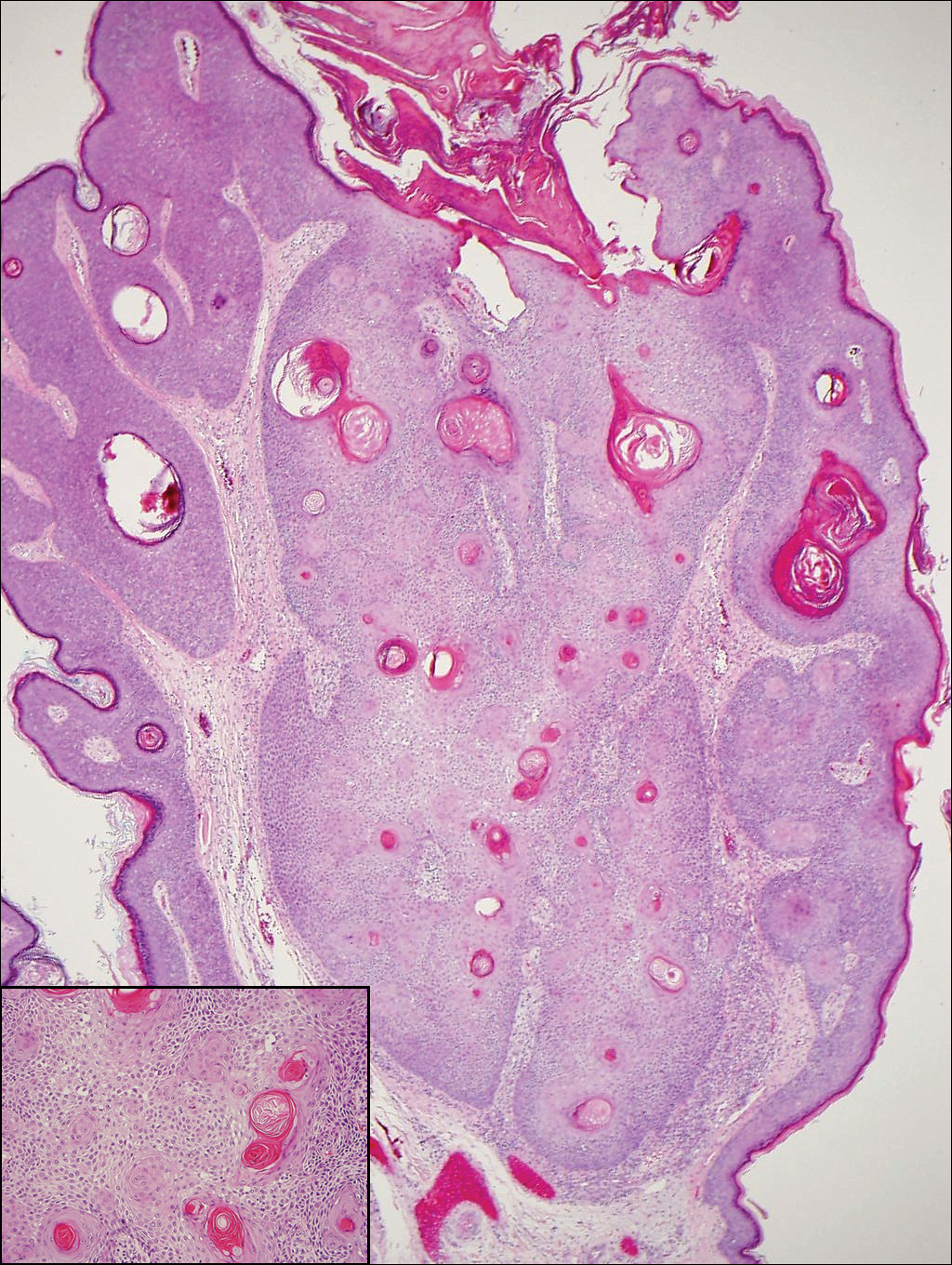

The differential diagnosis for endophytic squamous neoplasms encompasses benign and malignant entities. The histologic findings of our patient's lesion were compatible with the diagnosis of inverted follicular keratosis (IFK), a benign neoplasm that usually presents as a keratotic papule on the head or neck. Histologically, IFK is characterized by an endophytic growth pattern with squamous eddies (quiz images). Inverted follicular keratosis may represent an irritated seborrheic keratosis or a distinct neoplasm derived from the infundibular portion of the hair follicle; the exact etiology is uncertain.1,2 No relationship between IFK and human papillomavirus (HPV) has been established.3 Inverted follicular keratosis can mimic squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Important clues to the diagnosis of IFK are the presence of squamous eddies and the lack of squamous pearls or cytologic atypia.4 Squamous eddies consist of whorled keratinocytes without keratinization or atypia. Superficial shave biopsies may fail to demonstrate the characteristic well-circumscribed architecture and may lead to an erroneous diagnosis.

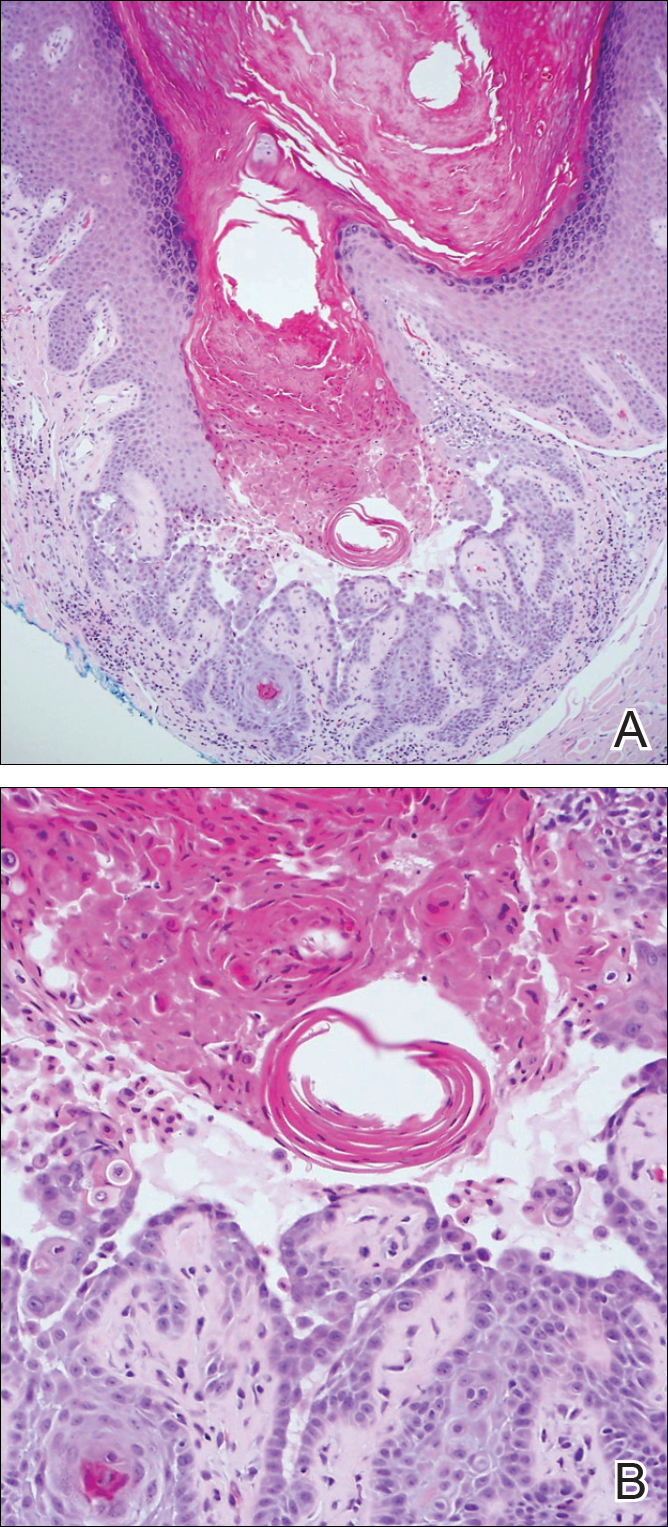

Acantholytic SCC is characterized by atypical keratinocytes that have lost cohesive properties, resulting in acantholysis (Figure 1).5 This histologic variant was once categorized as an aggressive variant of SCC, but studies have failed to support this assertion.5,6 Acantholytic SCC has a discohesive nature producing a pseudoglandular appearance sometimes mistaken for adenosquamous carcinoma or metastatic carcinoma. Recent literature has suggested that acantholytic SCCs, similar to IFKs, are derived from the follicular infundibulum.5,6 Also similar to IFKs, acantholytic SCCs often are located on the face. The invasive architecture and atypical cytology of acantholytic SCCs can differentiate them from IFKs. Acantholytic SCCs can contain keratin pearls with concentric keratinocytes showing incomplete keratinization centrally, often with retained nuclei, but rare to no squamous eddies unless irritated.

Trichilemmoma is an endophytic benign neoplasm derived from the outer sheath of the pilosebaceous follicle characterized by lobules of clear cells hanging from the epidermis.7 A study investigating the relationship between HPV and trichilemmomas failed to definitively detect HPV in trichilemmomas and this relationship remains unclear.8 Desmoplastic trichilemmoma is a subtype histologically characterized by jagged islands of epithelial cells separated by dense pink stroma and encased in a glassy basement membrane (Figure 2). The presence of desmoplasia and a jagged growth pattern can mimic invasive SCC, but the absence of cytologic atypia and the surrounding basement membrane differs from SCC.4,7 Trichilemmomas typically are solitary, but multiple lesions are associated with Cowden syndrome. Cowden syndrome is a rare autosomal-dominant condition characterized by the presence of benign hamartomas and a predisposition to the development of malignancies including breast, endometrial, and thyroid cancers.9,10 There is no such association with desmoplastic trichilemmomas.11

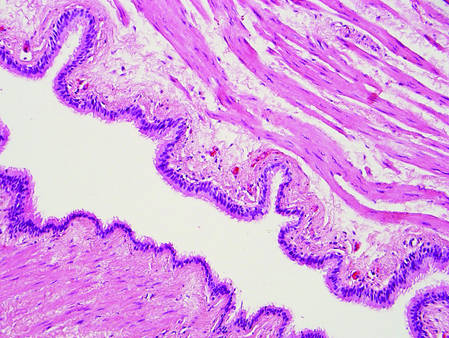

Pilar sheath acanthoma is a benign neoplasm that clinically presents as a solitary flesh-colored nodule with a central pore containing keratin.12 Histologically, pilar sheath acanthoma is similar to a dilated pore of Winer with the addition of acanthotic epidermal projections (Figure 3).

Warty dyskeratoma (WD) is a benign endophytic neoplasm traditionally seen as a solitary lesion histologically similar to Darier disease. Warty dyskeratomas are known to occur both on the skin and oral mucosa.13 Histologically, WD is characterized as a cup-shaped lesion with numerous villi at the base of the lesion along with acantholysis and dyskeratosis (Figure 4). The dyskeratotic cells in WD consist of corps ronds, which are cells with abundant pink cytoplasm, and small nuclei along with grains, which are flattened basophilic cells. These dyskeratotic cells help differentiate WD from IFK. Although they are endophytic neoplasms, WDs are well circumscribed and should not be confused with SCC. Despite this entity's name and histologic similarity to verrucae, no relationship with HPV has been established.14

- Ruhoy SM, Thomas D, Nuovo GJ. Multiple inverted follicular keratoses as a presenting sign of Cowden's syndrome: case report with human papillomavirus studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:411-415.

- Lever WF. Inverted follicular keratosis is an irritated seborrheic keratosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 1983;5:474.

- Kambiz KH, Kaveh D, Maede D, et al. Human papillomavirus deoxyribonucleic acid may not be detected in non-genital benign papillomatous skin lesions by polymerase chain reaction. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:334-338.

- Tan KB, Tan SH, Aw DC, et al. Simulators of squamous cell carcinoma of the skin: diagnostic challenges on small biopsies and clinicopathological correlation [published online June 25, 2013]. J Skin Cancer. 2013;2013:752864.

- Ogawa T, Kiuru M, Konia TH, et al. Acantholytic squamous cell carcinoma is usually associated with hair follicles, not acantholytic actinic keratosis, and is not "high risk": diagnosis, management, and clinical outcomes in a series of 115 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:327-333.

- Motaparthi K, Kapil JP, Velazquez EF. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: review of the eighth edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging guidelines, prognostic factors, and histopathologic variants. Adv Anat Pathol. 2017;24:171-194.

- Sano DT, Yang JJ, Tebcherani AJ, et al. A rare clinical presentation of desmoplastic trichilemmoma mimicking invasive carcinoma. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:796-798.

- Stierman S, Chen S, Nuovo G, et al. Detection of human papillomavirus infection in trichilemmomas and verrucae using in situ hybridization. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:75-80.

- Ngeow J, Eng C. PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome: clinical risk assessment and management protocol [published online October 22, 2014]. Methods. 2015;77-78:11-19.

- Molvi M, Sharma YK, Dash K. Cowden syndrome: case report, update and proposed diagnostic and surveillance routines. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:255-259.

- Jin M, Hampel H, Pilarski R, et al. Phosphatase and tensin homolog immunohistochemical staining and clinical criteria for Cowden syndrome in patients with trichilemmoma or associated lesions. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:637-640.

- Mehregan AH, Brownstein MH. Pilar sheath acanthoma. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114:1495-1497.

- Newland JR, Leventon GS. Warty dyskeratoma of the oral mucosa. correlated light and electron microscopic study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1984;58:176-183.

- Kaddu S, Dong H, Mayer G, et al. Warty dyskeratoma--"follicular dyskeratoma": analysis of clinicopathologic features of a distinctive follicular adnexal neoplasm. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:423-428.

The Diagnosis: Inverted Follicular Keratosis

The differential diagnosis for endophytic squamous neoplasms encompasses benign and malignant entities. The histologic findings of our patient's lesion were compatible with the diagnosis of inverted follicular keratosis (IFK), a benign neoplasm that usually presents as a keratotic papule on the head or neck. Histologically, IFK is characterized by an endophytic growth pattern with squamous eddies (quiz images). Inverted follicular keratosis may represent an irritated seborrheic keratosis or a distinct neoplasm derived from the infundibular portion of the hair follicle; the exact etiology is uncertain.1,2 No relationship between IFK and human papillomavirus (HPV) has been established.3 Inverted follicular keratosis can mimic squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Important clues to the diagnosis of IFK are the presence of squamous eddies and the lack of squamous pearls or cytologic atypia.4 Squamous eddies consist of whorled keratinocytes without keratinization or atypia. Superficial shave biopsies may fail to demonstrate the characteristic well-circumscribed architecture and may lead to an erroneous diagnosis.

Acantholytic SCC is characterized by atypical keratinocytes that have lost cohesive properties, resulting in acantholysis (Figure 1).5 This histologic variant was once categorized as an aggressive variant of SCC, but studies have failed to support this assertion.5,6 Acantholytic SCC has a discohesive nature producing a pseudoglandular appearance sometimes mistaken for adenosquamous carcinoma or metastatic carcinoma. Recent literature has suggested that acantholytic SCCs, similar to IFKs, are derived from the follicular infundibulum.5,6 Also similar to IFKs, acantholytic SCCs often are located on the face. The invasive architecture and atypical cytology of acantholytic SCCs can differentiate them from IFKs. Acantholytic SCCs can contain keratin pearls with concentric keratinocytes showing incomplete keratinization centrally, often with retained nuclei, but rare to no squamous eddies unless irritated.

Trichilemmoma is an endophytic benign neoplasm derived from the outer sheath of the pilosebaceous follicle characterized by lobules of clear cells hanging from the epidermis.7 A study investigating the relationship between HPV and trichilemmomas failed to definitively detect HPV in trichilemmomas and this relationship remains unclear.8 Desmoplastic trichilemmoma is a subtype histologically characterized by jagged islands of epithelial cells separated by dense pink stroma and encased in a glassy basement membrane (Figure 2). The presence of desmoplasia and a jagged growth pattern can mimic invasive SCC, but the absence of cytologic atypia and the surrounding basement membrane differs from SCC.4,7 Trichilemmomas typically are solitary, but multiple lesions are associated with Cowden syndrome. Cowden syndrome is a rare autosomal-dominant condition characterized by the presence of benign hamartomas and a predisposition to the development of malignancies including breast, endometrial, and thyroid cancers.9,10 There is no such association with desmoplastic trichilemmomas.11

Pilar sheath acanthoma is a benign neoplasm that clinically presents as a solitary flesh-colored nodule with a central pore containing keratin.12 Histologically, pilar sheath acanthoma is similar to a dilated pore of Winer with the addition of acanthotic epidermal projections (Figure 3).

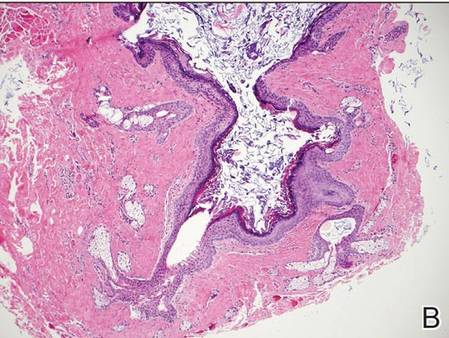

Warty dyskeratoma (WD) is a benign endophytic neoplasm traditionally seen as a solitary lesion histologically similar to Darier disease. Warty dyskeratomas are known to occur both on the skin and oral mucosa.13 Histologically, WD is characterized as a cup-shaped lesion with numerous villi at the base of the lesion along with acantholysis and dyskeratosis (Figure 4). The dyskeratotic cells in WD consist of corps ronds, which are cells with abundant pink cytoplasm, and small nuclei along with grains, which are flattened basophilic cells. These dyskeratotic cells help differentiate WD from IFK. Although they are endophytic neoplasms, WDs are well circumscribed and should not be confused with SCC. Despite this entity's name and histologic similarity to verrucae, no relationship with HPV has been established.14

The Diagnosis: Inverted Follicular Keratosis

The differential diagnosis for endophytic squamous neoplasms encompasses benign and malignant entities. The histologic findings of our patient's lesion were compatible with the diagnosis of inverted follicular keratosis (IFK), a benign neoplasm that usually presents as a keratotic papule on the head or neck. Histologically, IFK is characterized by an endophytic growth pattern with squamous eddies (quiz images). Inverted follicular keratosis may represent an irritated seborrheic keratosis or a distinct neoplasm derived from the infundibular portion of the hair follicle; the exact etiology is uncertain.1,2 No relationship between IFK and human papillomavirus (HPV) has been established.3 Inverted follicular keratosis can mimic squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Important clues to the diagnosis of IFK are the presence of squamous eddies and the lack of squamous pearls or cytologic atypia.4 Squamous eddies consist of whorled keratinocytes without keratinization or atypia. Superficial shave biopsies may fail to demonstrate the characteristic well-circumscribed architecture and may lead to an erroneous diagnosis.

Acantholytic SCC is characterized by atypical keratinocytes that have lost cohesive properties, resulting in acantholysis (Figure 1).5 This histologic variant was once categorized as an aggressive variant of SCC, but studies have failed to support this assertion.5,6 Acantholytic SCC has a discohesive nature producing a pseudoglandular appearance sometimes mistaken for adenosquamous carcinoma or metastatic carcinoma. Recent literature has suggested that acantholytic SCCs, similar to IFKs, are derived from the follicular infundibulum.5,6 Also similar to IFKs, acantholytic SCCs often are located on the face. The invasive architecture and atypical cytology of acantholytic SCCs can differentiate them from IFKs. Acantholytic SCCs can contain keratin pearls with concentric keratinocytes showing incomplete keratinization centrally, often with retained nuclei, but rare to no squamous eddies unless irritated.

Trichilemmoma is an endophytic benign neoplasm derived from the outer sheath of the pilosebaceous follicle characterized by lobules of clear cells hanging from the epidermis.7 A study investigating the relationship between HPV and trichilemmomas failed to definitively detect HPV in trichilemmomas and this relationship remains unclear.8 Desmoplastic trichilemmoma is a subtype histologically characterized by jagged islands of epithelial cells separated by dense pink stroma and encased in a glassy basement membrane (Figure 2). The presence of desmoplasia and a jagged growth pattern can mimic invasive SCC, but the absence of cytologic atypia and the surrounding basement membrane differs from SCC.4,7 Trichilemmomas typically are solitary, but multiple lesions are associated with Cowden syndrome. Cowden syndrome is a rare autosomal-dominant condition characterized by the presence of benign hamartomas and a predisposition to the development of malignancies including breast, endometrial, and thyroid cancers.9,10 There is no such association with desmoplastic trichilemmomas.11

Pilar sheath acanthoma is a benign neoplasm that clinically presents as a solitary flesh-colored nodule with a central pore containing keratin.12 Histologically, pilar sheath acanthoma is similar to a dilated pore of Winer with the addition of acanthotic epidermal projections (Figure 3).

Warty dyskeratoma (WD) is a benign endophytic neoplasm traditionally seen as a solitary lesion histologically similar to Darier disease. Warty dyskeratomas are known to occur both on the skin and oral mucosa.13 Histologically, WD is characterized as a cup-shaped lesion with numerous villi at the base of the lesion along with acantholysis and dyskeratosis (Figure 4). The dyskeratotic cells in WD consist of corps ronds, which are cells with abundant pink cytoplasm, and small nuclei along with grains, which are flattened basophilic cells. These dyskeratotic cells help differentiate WD from IFK. Although they are endophytic neoplasms, WDs are well circumscribed and should not be confused with SCC. Despite this entity's name and histologic similarity to verrucae, no relationship with HPV has been established.14

- Ruhoy SM, Thomas D, Nuovo GJ. Multiple inverted follicular keratoses as a presenting sign of Cowden's syndrome: case report with human papillomavirus studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:411-415.

- Lever WF. Inverted follicular keratosis is an irritated seborrheic keratosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 1983;5:474.

- Kambiz KH, Kaveh D, Maede D, et al. Human papillomavirus deoxyribonucleic acid may not be detected in non-genital benign papillomatous skin lesions by polymerase chain reaction. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:334-338.

- Tan KB, Tan SH, Aw DC, et al. Simulators of squamous cell carcinoma of the skin: diagnostic challenges on small biopsies and clinicopathological correlation [published online June 25, 2013]. J Skin Cancer. 2013;2013:752864.

- Ogawa T, Kiuru M, Konia TH, et al. Acantholytic squamous cell carcinoma is usually associated with hair follicles, not acantholytic actinic keratosis, and is not "high risk": diagnosis, management, and clinical outcomes in a series of 115 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:327-333.

- Motaparthi K, Kapil JP, Velazquez EF. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: review of the eighth edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging guidelines, prognostic factors, and histopathologic variants. Adv Anat Pathol. 2017;24:171-194.

- Sano DT, Yang JJ, Tebcherani AJ, et al. A rare clinical presentation of desmoplastic trichilemmoma mimicking invasive carcinoma. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:796-798.

- Stierman S, Chen S, Nuovo G, et al. Detection of human papillomavirus infection in trichilemmomas and verrucae using in situ hybridization. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:75-80.

- Ngeow J, Eng C. PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome: clinical risk assessment and management protocol [published online October 22, 2014]. Methods. 2015;77-78:11-19.

- Molvi M, Sharma YK, Dash K. Cowden syndrome: case report, update and proposed diagnostic and surveillance routines. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:255-259.

- Jin M, Hampel H, Pilarski R, et al. Phosphatase and tensin homolog immunohistochemical staining and clinical criteria for Cowden syndrome in patients with trichilemmoma or associated lesions. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:637-640.

- Mehregan AH, Brownstein MH. Pilar sheath acanthoma. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114:1495-1497.

- Newland JR, Leventon GS. Warty dyskeratoma of the oral mucosa. correlated light and electron microscopic study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1984;58:176-183.

- Kaddu S, Dong H, Mayer G, et al. Warty dyskeratoma--"follicular dyskeratoma": analysis of clinicopathologic features of a distinctive follicular adnexal neoplasm. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:423-428.

- Ruhoy SM, Thomas D, Nuovo GJ. Multiple inverted follicular keratoses as a presenting sign of Cowden's syndrome: case report with human papillomavirus studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:411-415.

- Lever WF. Inverted follicular keratosis is an irritated seborrheic keratosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 1983;5:474.

- Kambiz KH, Kaveh D, Maede D, et al. Human papillomavirus deoxyribonucleic acid may not be detected in non-genital benign papillomatous skin lesions by polymerase chain reaction. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:334-338.

- Tan KB, Tan SH, Aw DC, et al. Simulators of squamous cell carcinoma of the skin: diagnostic challenges on small biopsies and clinicopathological correlation [published online June 25, 2013]. J Skin Cancer. 2013;2013:752864.

- Ogawa T, Kiuru M, Konia TH, et al. Acantholytic squamous cell carcinoma is usually associated with hair follicles, not acantholytic actinic keratosis, and is not "high risk": diagnosis, management, and clinical outcomes in a series of 115 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:327-333.

- Motaparthi K, Kapil JP, Velazquez EF. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: review of the eighth edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging guidelines, prognostic factors, and histopathologic variants. Adv Anat Pathol. 2017;24:171-194.

- Sano DT, Yang JJ, Tebcherani AJ, et al. A rare clinical presentation of desmoplastic trichilemmoma mimicking invasive carcinoma. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:796-798.

- Stierman S, Chen S, Nuovo G, et al. Detection of human papillomavirus infection in trichilemmomas and verrucae using in situ hybridization. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:75-80.

- Ngeow J, Eng C. PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome: clinical risk assessment and management protocol [published online October 22, 2014]. Methods. 2015;77-78:11-19.

- Molvi M, Sharma YK, Dash K. Cowden syndrome: case report, update and proposed diagnostic and surveillance routines. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:255-259.

- Jin M, Hampel H, Pilarski R, et al. Phosphatase and tensin homolog immunohistochemical staining and clinical criteria for Cowden syndrome in patients with trichilemmoma or associated lesions. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:637-640.

- Mehregan AH, Brownstein MH. Pilar sheath acanthoma. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114:1495-1497.

- Newland JR, Leventon GS. Warty dyskeratoma of the oral mucosa. correlated light and electron microscopic study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1984;58:176-183.

- Kaddu S, Dong H, Mayer G, et al. Warty dyskeratoma--"follicular dyskeratoma": analysis of clinicopathologic features of a distinctive follicular adnexal neoplasm. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:423-428.

A 60-year-old man presented with a 3-mm verrucous papule on the right upper eyelid of 2 years' duration.

Cyst on the Eyebrow

The best diagnosis is:

a. bronchogenic cyst

b. dermoid cyst

c. epidermal inclusion cyst

d. hidrocystoma

e. steatocystoma

|

|

| H&E, original magnification ×40. |

|

| H&E, original magnification ×100. |

Continue to the next page for the diagnosis >>

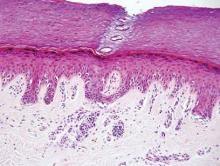

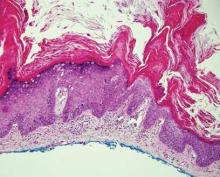

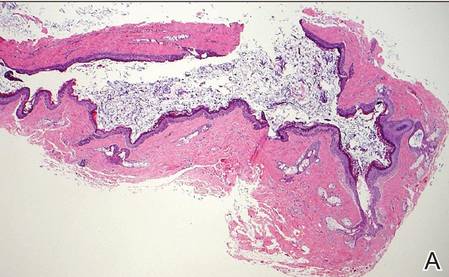

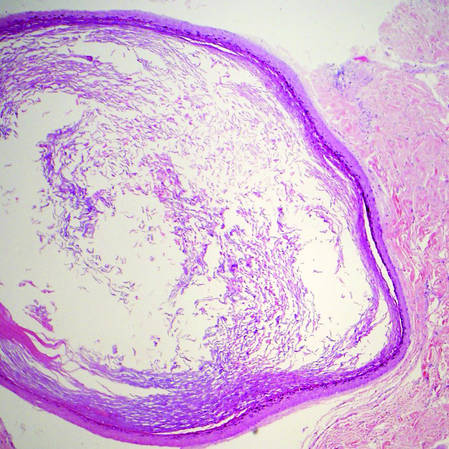

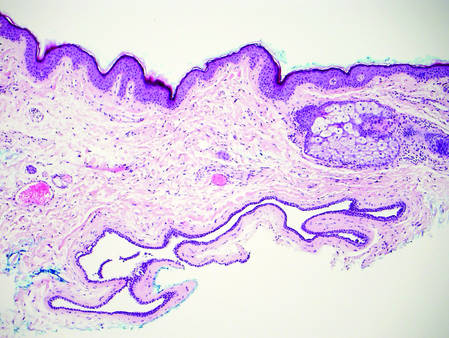

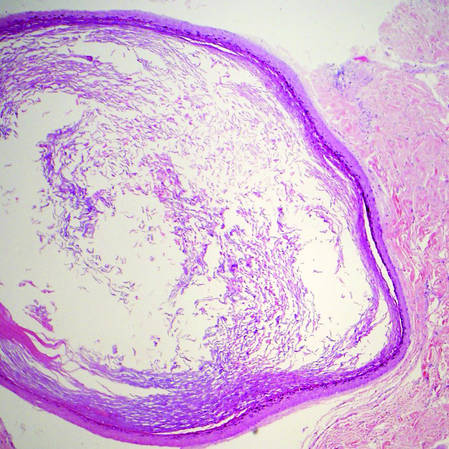

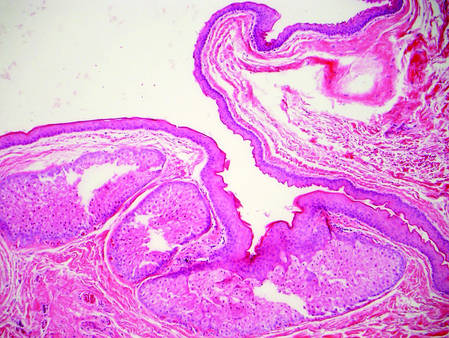

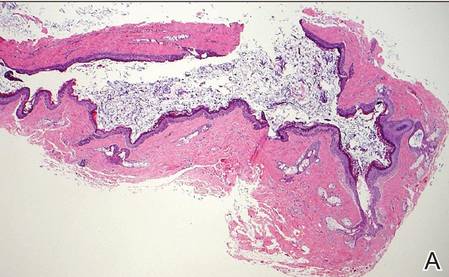

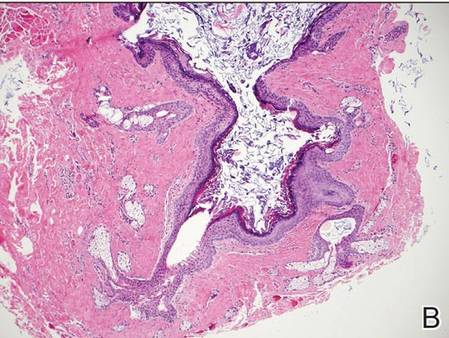

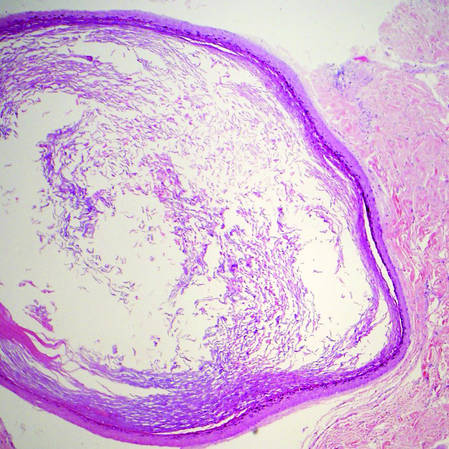

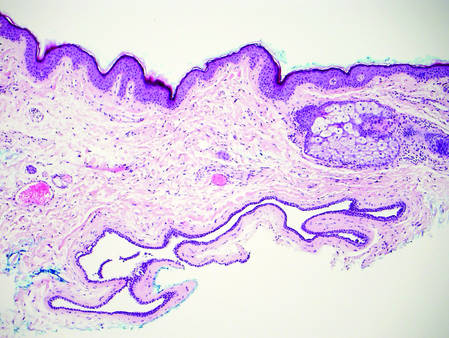

Dermoid Cyst

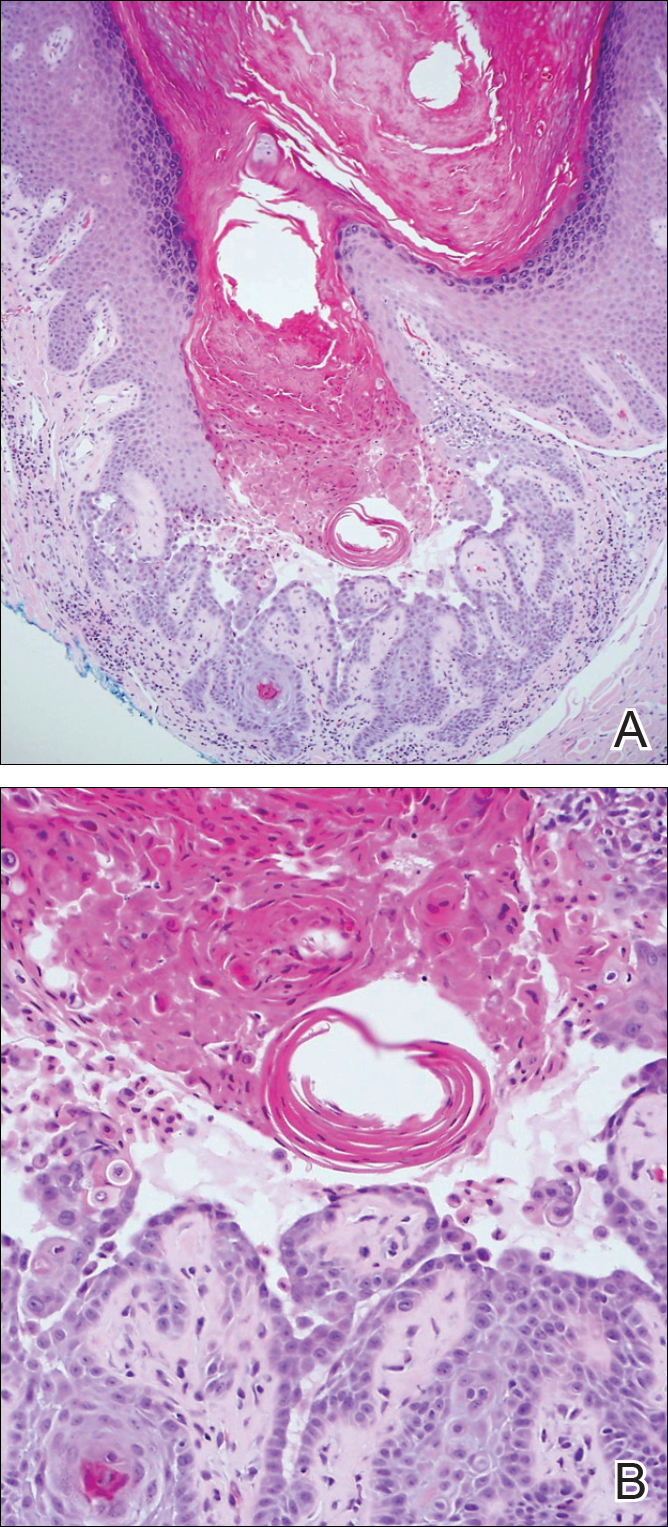

Dermoid cysts often present clinically as firm subcutaneous nodules on the head or neck in young children. They tend to arise along the lateral aspect of the eyebrow but also can occur on the nose, forehead, neck, chest, or scalp.1 Dermoid cysts are thought to arise from the sequestration of ectodermal tissues along the embryonic fusion planes during development.2 As such, they represent congenital defects and often are identified at birth; however, some are not noticed until much later when they enlarge or become inflamed or infected. Midline dermoid cysts may be associated with underlying dysraphism or intracranial extension.3,4 Thus, any midline lesion warrants evaluation that incorporates imaging with computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging.4,5 Histologically, dermoid cysts are lined by a keratinizing stratified squamous epithelium (quiz image A), but the lining may be brightly eosinophilic and wavy resembling shark teeth.1,3 The wall of a dermoid cyst commonly contains mature adnexal structures such as terminal hair follicles, sebaceous glands, apocrine glands, and/or eccrine glands (quiz image B).1 Smooth muscle also may be seen within the lining; however, bone and cartilage are not commonly reported in dermoid cysts.2 Lamellar keratin is typical of the cyst contents, and terminal hair shafts also are sometimes noted within the cystic space (quiz image B).1,2 Treatment options include excision at the time of diagnosis or close clinical monitoring with subsequent excision if the lesion grows or becomes symptomatic.4,5 Many practitioners opt to excise these cysts at diagnosis, as untreated lesions are at risk for infection and/or inflammation or may be cosmetically deforming.6,7 Surgical resection, including removal of the wall of the cyst, is curative and reoccurrence is rare.5

| |

Figure 1. Bronchogenic cyst demonstrating a ciliated pseudostratified epithelial lining encircled by smooth muscle (H&E, original magnification ×200). | |

| |

| Figure 2. Epidermal inclusion cyst containing loose lamellar keratin and a lining that closely resembles the surface epidermis (H&E, original magnification ×40). |

|

Bronchogenic cysts demonstrate an epithelial lining that often is pseudostratified cuboidal or columnar as well as ciliated (Figure 1). Goblet cells are present in the lining in approximately 50% of cases. Smooth muscle may be seen circumferentially surrounding the cyst lining, and rare cases also contain cartilage.1 In contrast to dermoid cysts, other types of adnexal structures are not found within the lining. Bronchogenic cysts that arise in the skin are extremely rare.2 These cysts are thought to arise from respiratory epithelium that has been sequestered during embryologic formation of the tracheobronchial tree. They often are seen overlying the suprasternal notch and occasionally are found on the anterior aspect of the neck or chin. These cysts also are present at birth, similar to dermoid cysts.3

Epidermal inclusion cysts have a lining that histologically bears close resemblance to the surface epidermis. These cysts contain loose lamellar keratin, similar to a dermoid cyst. In contrast, the lining of an epidermal inclusion cyst will lack adnexal structures (Figure 2).1 Clinically, epidermal inclusion cysts often present as smooth, dome-shaped papules and nodules with a central punctum. They are classically found on the face, neck, and trunk. These cysts are thought to arise after a traumatic insult to the pilosebaceous unit.2

Hidrocystomas can be apocrine or eccrine.3 Eccrine hidrocystomas are unilocular cysts that are lined by 2 layers of flattened to cuboidal epithelial cells (Figure 3). The cysts are filled with clear fluid and often are found adjacent to normal eccrine glands.1 Apocrine hidrocystomas are unilocular or multilocular cysts that are lined by 1 to several layers of epithelial cells. The lining of an apocrine hidrocystoma will often exhibit luminal decapitation secretion.3 Apocrine and eccrine hidrocystomas are clinically identical and appear as blue translucent papules on the cheeks or eyelids of adults.1-3 They usually occur periorbitally but also can be seen on the trunk, popliteal fossa, external ears, or vulva. Eccrine hidrocystomas can wax and wane in accordance with the amount of sweat produced; thus, they often expand in size during the summer months.2

Steatocystomas, or simple sebaceous duct cysts, histologically demonstrate a characteristically wavy and eosinophilic cuticle resembling shark teeth (Figure 4) similar to the lining of the sebaceous duct where it enters the follicle.1 Sebaceous glands are an almost invariable feature, either present within the lining of the cyst (Figure 4) or in the adjacent tissue.2 In comparison, dermoid cysts may have a red wavy cuticle but also will usually have terminal hair follicles or eccrine or apocrine glands within the wall of the cyst. Steatocystomas typically are collapsed and empty or only contain sebaceous debris (Figure 4) rather than the lamellar keratin seen in dermoid and epidermoid inclusion cysts. Steatocystomas can occur as solitary (steatocystoma simplex) or multiple (steatocystoma multiplex) lesions.1,3 They are clinically comprised of small dome-shaped papules that often are translucent and yellow. These cysts are commonly found on the sternum of males and the axillae or groin of females.2

|  | |

Figure 3. Eccrine hidrocystoma with clear contents and lined by 2 layers of cuboidal epithelial cells (H&E, original magnification ×100). | Figure 4. Steatocystoma with a red wavy cuticle, sparse sebaceous contents, and sebaceous glands within the lining (H&E, original magnification ×100). |

|

1. Elston DM, Ferringer TC, Ko C, et al. Dermatopathology: Requisites in Dermatology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2014.

2. Calonje JE, Brenn T, Lazar AJ, et al. McKee’s Pathology of the Skin. 4th ed. St Louis, MO: Elsevier/Saunders; 2012.

3. Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Shaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2012.

4. Orozco-Covarrubias L, Lara-Carpio R, Saez-De-Ocariz M, et al. Dermoid cysts: a report of 75 pediatric patients. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:706-711.

5. Sorenson EP, Powel JE, Rozzelle CJ, et al. Scalp dermoids: a review of their anatomy, diagnosis, and treatment. Childs Nerv Syst. 2013;29:375-380.

6. Pryor SG, Lewis JE, Weaver AL, et al. Pediatric dermoid cysts of the head and neck. Otolarynol Head Neck Surg. 2005;132:938-942.

7. Abou-Rayyah Y, Rose GE, Konrad H, et al. Clinical, radiological and pathological examination of periocular dermoid cysts: evidence of inflammation from an early age. Eye (Lond). 2002;16:507-512.

The best diagnosis is:

a. bronchogenic cyst

b. dermoid cyst

c. epidermal inclusion cyst

d. hidrocystoma

e. steatocystoma

|

|

| H&E, original magnification ×40. |

|

| H&E, original magnification ×100. |

Continue to the next page for the diagnosis >>

Dermoid Cyst

Dermoid cysts often present clinically as firm subcutaneous nodules on the head or neck in young children. They tend to arise along the lateral aspect of the eyebrow but also can occur on the nose, forehead, neck, chest, or scalp.1 Dermoid cysts are thought to arise from the sequestration of ectodermal tissues along the embryonic fusion planes during development.2 As such, they represent congenital defects and often are identified at birth; however, some are not noticed until much later when they enlarge or become inflamed or infected. Midline dermoid cysts may be associated with underlying dysraphism or intracranial extension.3,4 Thus, any midline lesion warrants evaluation that incorporates imaging with computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging.4,5 Histologically, dermoid cysts are lined by a keratinizing stratified squamous epithelium (quiz image A), but the lining may be brightly eosinophilic and wavy resembling shark teeth.1,3 The wall of a dermoid cyst commonly contains mature adnexal structures such as terminal hair follicles, sebaceous glands, apocrine glands, and/or eccrine glands (quiz image B).1 Smooth muscle also may be seen within the lining; however, bone and cartilage are not commonly reported in dermoid cysts.2 Lamellar keratin is typical of the cyst contents, and terminal hair shafts also are sometimes noted within the cystic space (quiz image B).1,2 Treatment options include excision at the time of diagnosis or close clinical monitoring with subsequent excision if the lesion grows or becomes symptomatic.4,5 Many practitioners opt to excise these cysts at diagnosis, as untreated lesions are at risk for infection and/or inflammation or may be cosmetically deforming.6,7 Surgical resection, including removal of the wall of the cyst, is curative and reoccurrence is rare.5

| |

Figure 1. Bronchogenic cyst demonstrating a ciliated pseudostratified epithelial lining encircled by smooth muscle (H&E, original magnification ×200). | |

| |

| Figure 2. Epidermal inclusion cyst containing loose lamellar keratin and a lining that closely resembles the surface epidermis (H&E, original magnification ×40). |

|

Bronchogenic cysts demonstrate an epithelial lining that often is pseudostratified cuboidal or columnar as well as ciliated (Figure 1). Goblet cells are present in the lining in approximately 50% of cases. Smooth muscle may be seen circumferentially surrounding the cyst lining, and rare cases also contain cartilage.1 In contrast to dermoid cysts, other types of adnexal structures are not found within the lining. Bronchogenic cysts that arise in the skin are extremely rare.2 These cysts are thought to arise from respiratory epithelium that has been sequestered during embryologic formation of the tracheobronchial tree. They often are seen overlying the suprasternal notch and occasionally are found on the anterior aspect of the neck or chin. These cysts also are present at birth, similar to dermoid cysts.3

Epidermal inclusion cysts have a lining that histologically bears close resemblance to the surface epidermis. These cysts contain loose lamellar keratin, similar to a dermoid cyst. In contrast, the lining of an epidermal inclusion cyst will lack adnexal structures (Figure 2).1 Clinically, epidermal inclusion cysts often present as smooth, dome-shaped papules and nodules with a central punctum. They are classically found on the face, neck, and trunk. These cysts are thought to arise after a traumatic insult to the pilosebaceous unit.2

Hidrocystomas can be apocrine or eccrine.3 Eccrine hidrocystomas are unilocular cysts that are lined by 2 layers of flattened to cuboidal epithelial cells (Figure 3). The cysts are filled with clear fluid and often are found adjacent to normal eccrine glands.1 Apocrine hidrocystomas are unilocular or multilocular cysts that are lined by 1 to several layers of epithelial cells. The lining of an apocrine hidrocystoma will often exhibit luminal decapitation secretion.3 Apocrine and eccrine hidrocystomas are clinically identical and appear as blue translucent papules on the cheeks or eyelids of adults.1-3 They usually occur periorbitally but also can be seen on the trunk, popliteal fossa, external ears, or vulva. Eccrine hidrocystomas can wax and wane in accordance with the amount of sweat produced; thus, they often expand in size during the summer months.2

Steatocystomas, or simple sebaceous duct cysts, histologically demonstrate a characteristically wavy and eosinophilic cuticle resembling shark teeth (Figure 4) similar to the lining of the sebaceous duct where it enters the follicle.1 Sebaceous glands are an almost invariable feature, either present within the lining of the cyst (Figure 4) or in the adjacent tissue.2 In comparison, dermoid cysts may have a red wavy cuticle but also will usually have terminal hair follicles or eccrine or apocrine glands within the wall of the cyst. Steatocystomas typically are collapsed and empty or only contain sebaceous debris (Figure 4) rather than the lamellar keratin seen in dermoid and epidermoid inclusion cysts. Steatocystomas can occur as solitary (steatocystoma simplex) or multiple (steatocystoma multiplex) lesions.1,3 They are clinically comprised of small dome-shaped papules that often are translucent and yellow. These cysts are commonly found on the sternum of males and the axillae or groin of females.2

|  | |

Figure 3. Eccrine hidrocystoma with clear contents and lined by 2 layers of cuboidal epithelial cells (H&E, original magnification ×100). | Figure 4. Steatocystoma with a red wavy cuticle, sparse sebaceous contents, and sebaceous glands within the lining (H&E, original magnification ×100). |

|

The best diagnosis is:

a. bronchogenic cyst

b. dermoid cyst

c. epidermal inclusion cyst

d. hidrocystoma

e. steatocystoma

|

|

| H&E, original magnification ×40. |

|

| H&E, original magnification ×100. |

Continue to the next page for the diagnosis >>

Dermoid Cyst

Dermoid cysts often present clinically as firm subcutaneous nodules on the head or neck in young children. They tend to arise along the lateral aspect of the eyebrow but also can occur on the nose, forehead, neck, chest, or scalp.1 Dermoid cysts are thought to arise from the sequestration of ectodermal tissues along the embryonic fusion planes during development.2 As such, they represent congenital defects and often are identified at birth; however, some are not noticed until much later when they enlarge or become inflamed or infected. Midline dermoid cysts may be associated with underlying dysraphism or intracranial extension.3,4 Thus, any midline lesion warrants evaluation that incorporates imaging with computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging.4,5 Histologically, dermoid cysts are lined by a keratinizing stratified squamous epithelium (quiz image A), but the lining may be brightly eosinophilic and wavy resembling shark teeth.1,3 The wall of a dermoid cyst commonly contains mature adnexal structures such as terminal hair follicles, sebaceous glands, apocrine glands, and/or eccrine glands (quiz image B).1 Smooth muscle also may be seen within the lining; however, bone and cartilage are not commonly reported in dermoid cysts.2 Lamellar keratin is typical of the cyst contents, and terminal hair shafts also are sometimes noted within the cystic space (quiz image B).1,2 Treatment options include excision at the time of diagnosis or close clinical monitoring with subsequent excision if the lesion grows or becomes symptomatic.4,5 Many practitioners opt to excise these cysts at diagnosis, as untreated lesions are at risk for infection and/or inflammation or may be cosmetically deforming.6,7 Surgical resection, including removal of the wall of the cyst, is curative and reoccurrence is rare.5

| |

Figure 1. Bronchogenic cyst demonstrating a ciliated pseudostratified epithelial lining encircled by smooth muscle (H&E, original magnification ×200). | |

| |

| Figure 2. Epidermal inclusion cyst containing loose lamellar keratin and a lining that closely resembles the surface epidermis (H&E, original magnification ×40). |

|

Bronchogenic cysts demonstrate an epithelial lining that often is pseudostratified cuboidal or columnar as well as ciliated (Figure 1). Goblet cells are present in the lining in approximately 50% of cases. Smooth muscle may be seen circumferentially surrounding the cyst lining, and rare cases also contain cartilage.1 In contrast to dermoid cysts, other types of adnexal structures are not found within the lining. Bronchogenic cysts that arise in the skin are extremely rare.2 These cysts are thought to arise from respiratory epithelium that has been sequestered during embryologic formation of the tracheobronchial tree. They often are seen overlying the suprasternal notch and occasionally are found on the anterior aspect of the neck or chin. These cysts also are present at birth, similar to dermoid cysts.3

Epidermal inclusion cysts have a lining that histologically bears close resemblance to the surface epidermis. These cysts contain loose lamellar keratin, similar to a dermoid cyst. In contrast, the lining of an epidermal inclusion cyst will lack adnexal structures (Figure 2).1 Clinically, epidermal inclusion cysts often present as smooth, dome-shaped papules and nodules with a central punctum. They are classically found on the face, neck, and trunk. These cysts are thought to arise after a traumatic insult to the pilosebaceous unit.2