User login

Coding the “Spot Check”: Part 2

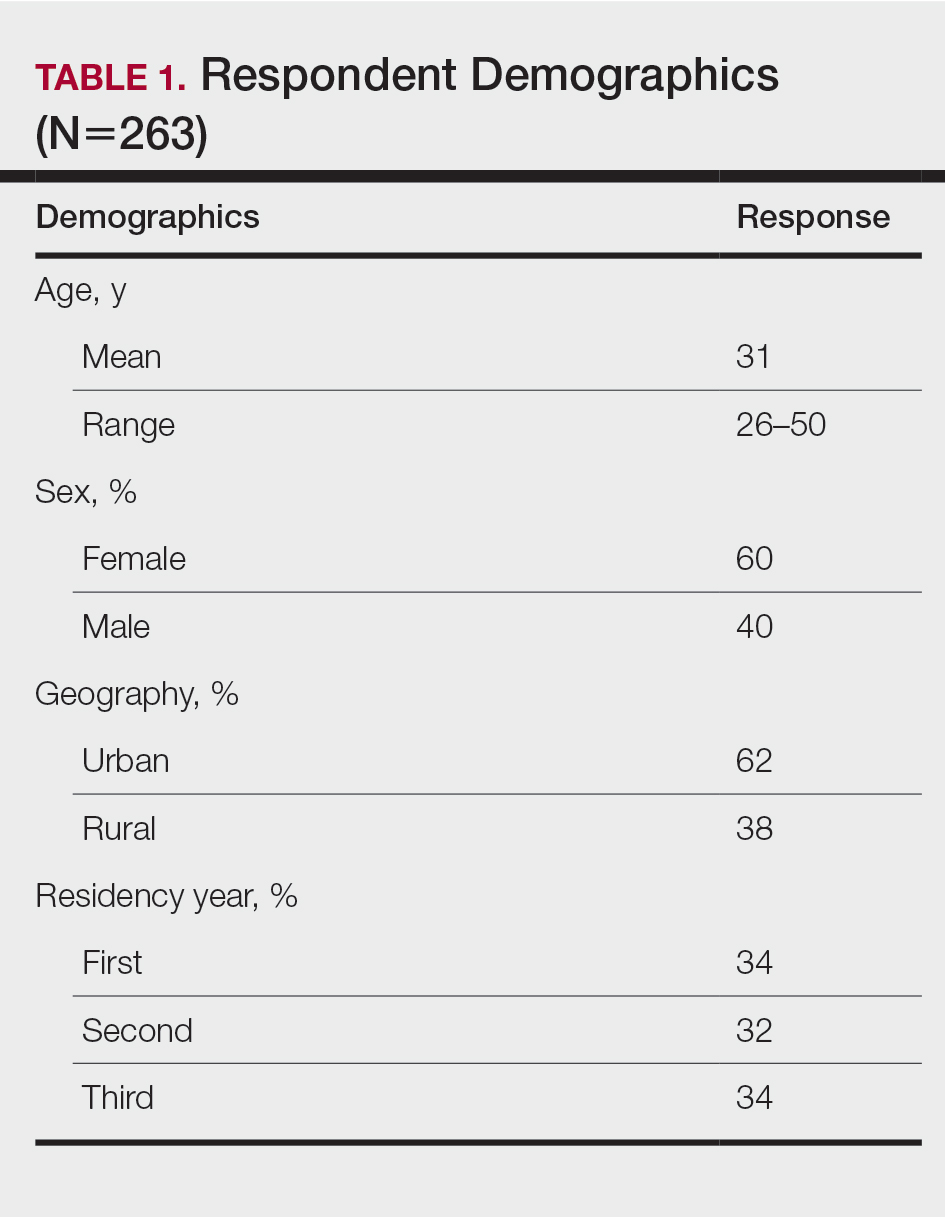

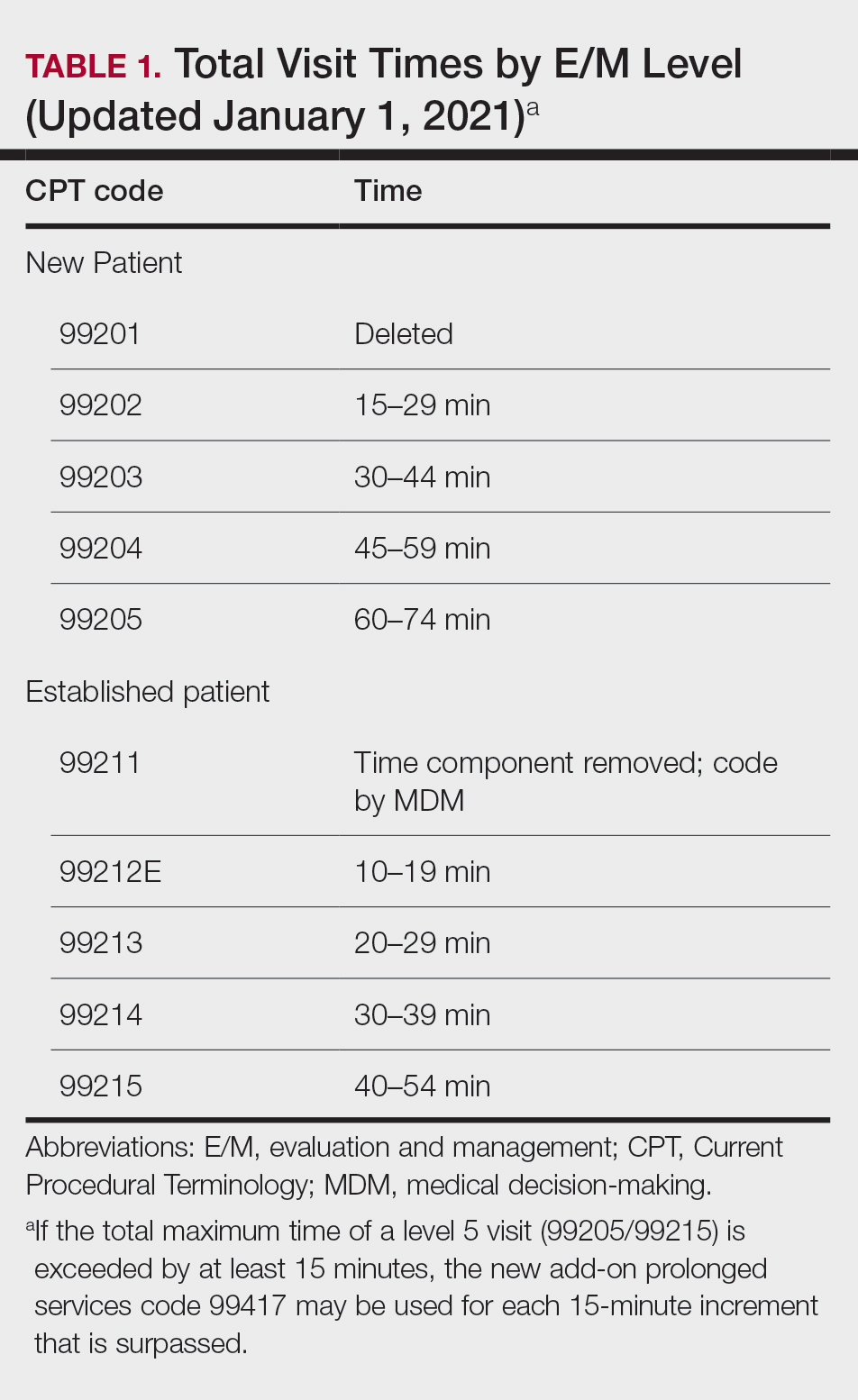

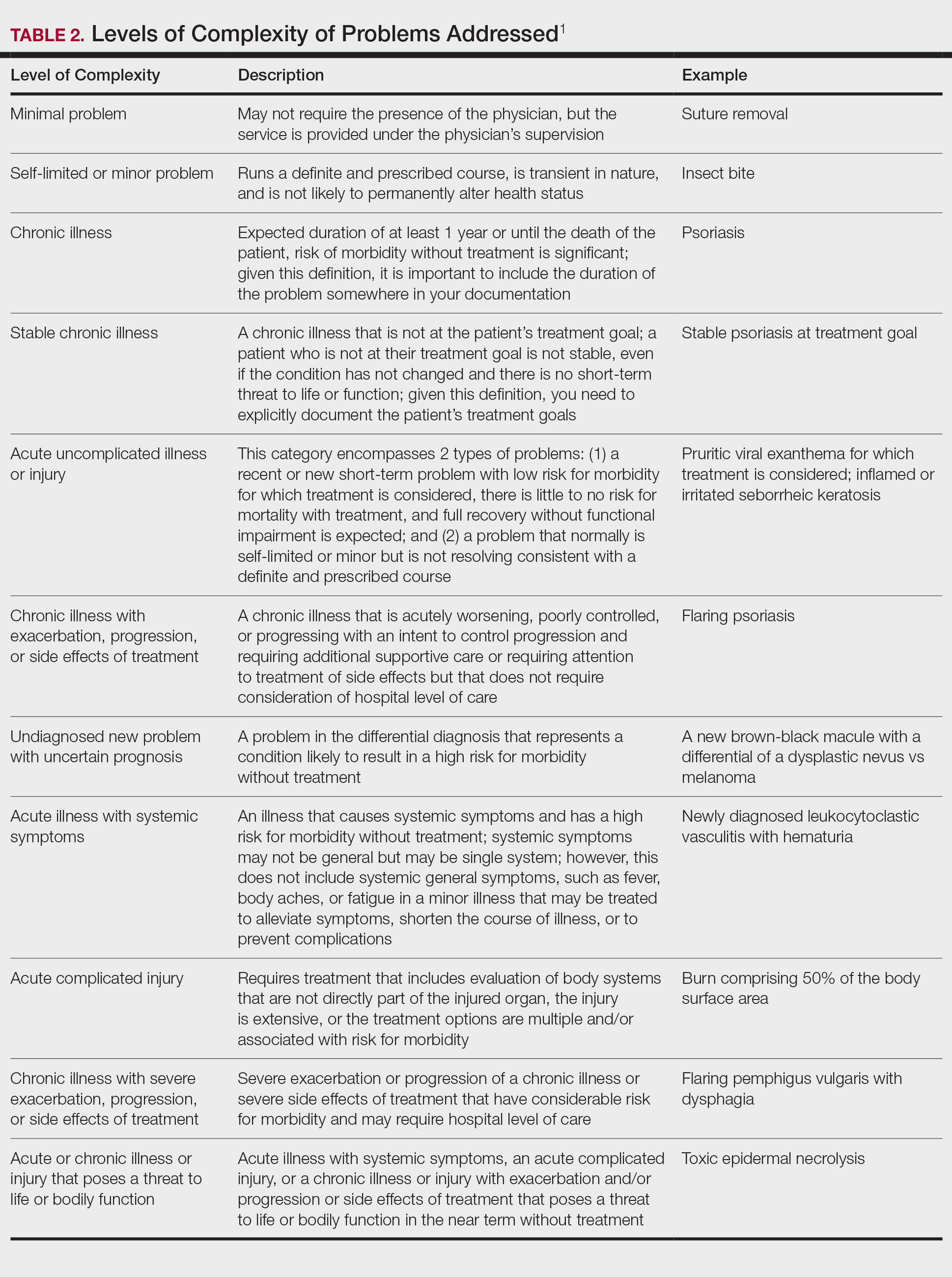

When the Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) evaluation and management (E/M) reporting rules changed dramatically in January 2021, “bullet counting” became unnecessary and the coding level became based on either the new medical decision making (MDM) table or time spent on all activities relating to the care of the patient on the day of the encounter. 1

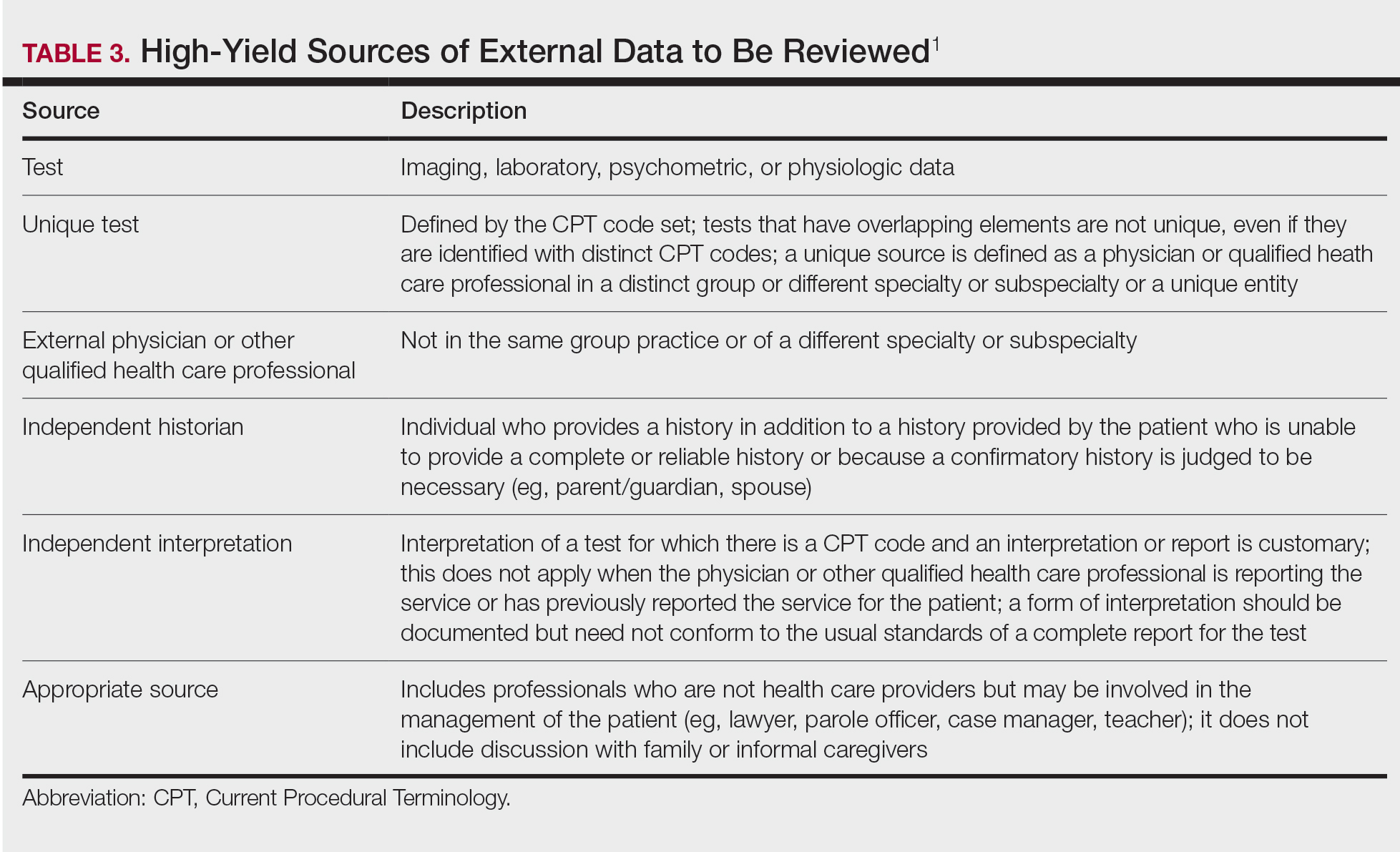

To make your documentation more likely to pass audits, explicitly link parts of your documentation to CPT MDM descriptors. Part 1 of this series discussed how to approach the “spot check,” a commonly encountered chief concern (CC) within dermatology, with 2 scenarios presented.2 The American Medical Association3 and American Academy of Dermatology4 have provided education that focuses on how to report a given vignette, but specific examples of documentation with commentary are uncommon. In part 2, we describe how to best code an encounter that includes a “spot check” with other concerns.

Scenario 3: By the Way, Doc

A 34-year-old presents with a new spot on the left cheek that seems to be growing and changing shape rapidly. You examine the patient and discuss treatment options. The documentation reads as follows:

- CC: New spot on left cheek that seems to be growing and changing shape rapidly.

- History: No family history of skin cancer; concerned about scarring, no blood thinner.

- Examination: Irregular tan to brown to black 8-mm macule. No lymphadenopathy.

- Impression: Rule out melanoma (undiagnosed new problem with uncertain prognosis).

- Plan: Discuss risks, benefits, and alternatives, including biopsy (decision regarding minor surgery with identified patient or procedure risk factors) vs a noninvasive gene expression profiling (GEP) melanoma rule-out test. (Based on the decision you and the patient make, you also would document which option was chosen, so a biopsy would include your standard documentation, and if the GEP is chosen, you would simply state that this was chosen and performed.)

As you turn to leave the room, the patient says:“By the way, Doc, can you do anything about these

How would it be best to approach this scenario? It depends on which treatment option the patient chooses.

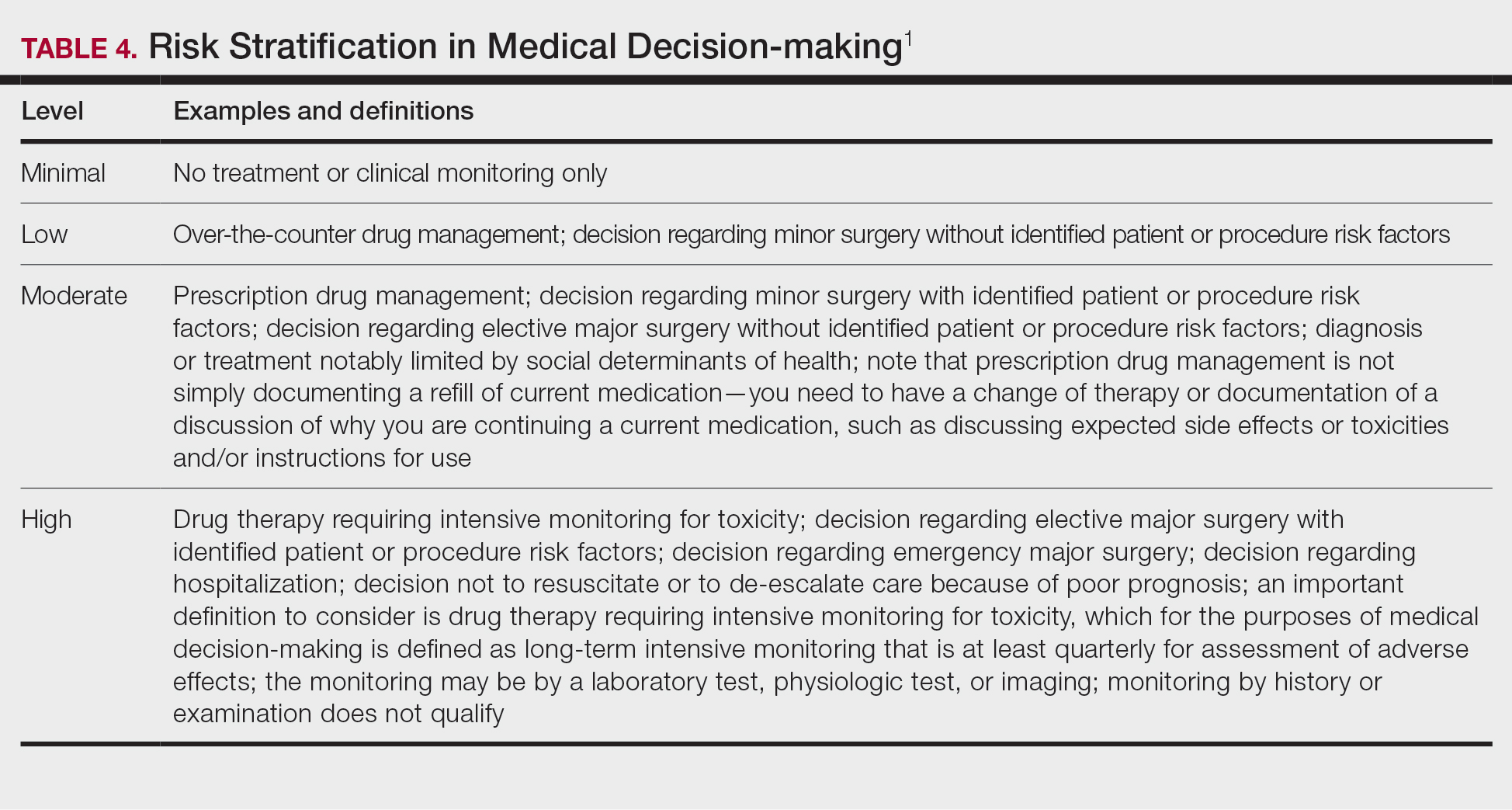

If you performed a noninvasive GEP melanoma rule-out test, the CPT reporting does not change with the addition of the new problem, and only the codes 99204 (new patient office or other outpatient visit) or 99214 (established patient office or other outpatient visit) would be reported. This would be because, with the original documentation, the number and complexity of problems would be an “undiagnosed new problem with uncertain prognosis,” which would be moderate complexity (column 1, level 4). There are no data that are reviewed or analyzed, which would be straightforward (column 2, level 2). For risk, the discussion of the biopsy as a diagnostic choice should include possible scarring, bleeding, pain, and infection, which would be best described as a decision regarding minor surgery with identified patient or procedure risk factors, given the identified patient concerns, making this of moderate complexity (column 3, level 4).1

Importantly, even if the procedure is not chosen as the final treatment plan, the discussion regarding the surgery, including the risks, benefits, and alternatives, can still count toward this category in the MDM table. Therefore, in this scenario, documentation would best fit with CPT code 99204 for a new patient or 99214 for an established patient. The addition of the psoriasis diagnosis would not change the level of service but also should include documentation of the psoriasis as medically necessary.

However, if you perform the biopsy, then the documentation above would only allow reporting the biopsy, as the decision to perform a 0- or 10-day global procedure is “bundled” with the procedure if performed on the same date of service. Therefore, with the addition of the psoriasis diagnosis, you would now use a separate E/M code to report the psoriasis. You must append a modifier −25 to the E/M code to certify that you are dealing with a separate and discrete problem with no overlap in physician work.

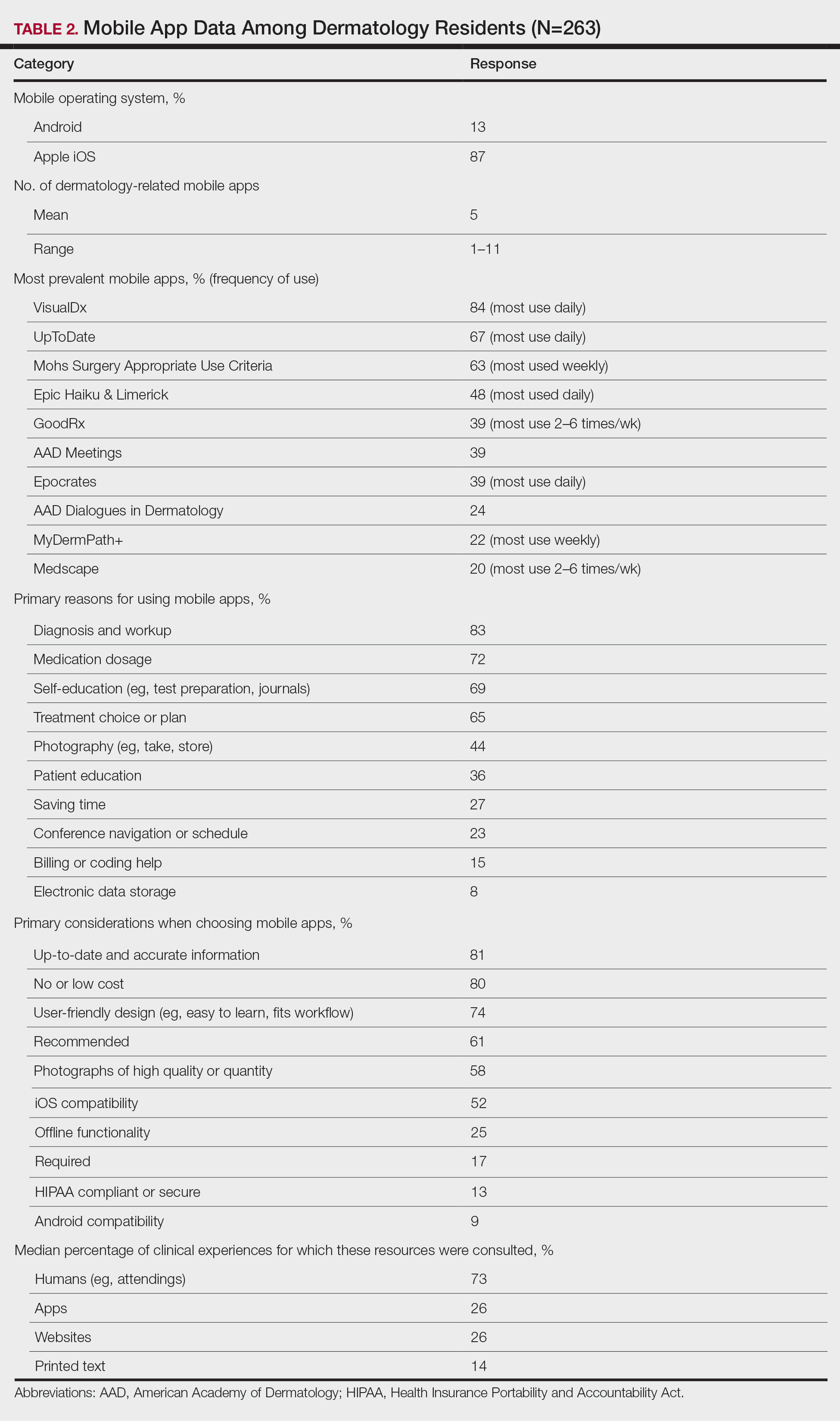

Clearly you also have an E/M to report. But what level? Is this chronic? Yes, as CPT clearly defines chronic as “[a] problem with an expected duration of at least one year or until the death of the patient.”1,5

But is this stable progressive or showing side effects of treatment? “‘Stable’ for the purposes of categorizing MDM is defined by the specific treatment goals for an individual patient. A patient who is not at his or her treatment goal is not stable, even if the condition has not changed and there is no short-term threat to life or function,” according to the CPT descriptors. Therefore, in this scenario, the documentation would best fit a chronic illness with exacerbation, progression, or side effects of treatment (column 1, level 4), which is of moderate complexity.1

But what about column 3, where we look at risks of testing and treatment? This would depend on the type of treatment given. If an over-the-counter product such as a tar gel is recommended, this is a low risk (column 3, level 3), which would mean this lower value determines the E/M code to be 99213 or 99203 depending on whether this is an established or new patient, respectively. If we treat with a prescription medication such as a topical corticosteroid, we are providing prescription drug management (column 3, level 4), which is moderate risk, and we would use codes 99204 or 99214, assuming we document appropriately. Again, including the CPT terminology of “not at treatment goal” in your impression and “prescription drug management” in your plan tells an auditor what you are thinking and doing.1,5

The Takeaway—Clearly if a GEP is performed, there is a single CPT code used—99204 or 99214. If the biopsy is performed, there would be a biopsy code and an E/M code with a modifier −25 attached to the latter. For the documentation below, a 99204 or 99214 would be the chosen E/M code:

- CC: (1) New spot on left cheek that seems to be growing and changing shape rapidly; (2) Silvery spots on elbows, knees, and buttocks for which patient desires treatment.

- History: No family history of skin cancer; concerned about scarring, no blood thinner. Mom has psoriasis. Tried petroleum jelly on scaly areas but no better.

- Examination: Irregular tan to brown to black 8-mm macule. No lymphadenopathy. Silver scaly erythematous plaques on elbows, knees, sacrum.

- Impression: (1) Rule out melanoma (undiagnosed new problem with uncertain prognosis); (2) Psoriasis (chronic disease not at treatment goal).

- Plan: (1) Discuss risks, benefits, and alternatives, including biopsy (decision regarding minor surgery with identified patient or procedure risk factors) vs a noninvasive GEP melanoma rule-out test. Patient wants biopsy. Consent, biopsy via shave technique. Lidocaine hydrochloride 1% with epinephrine 1 cc, prepare and drape, aluminum chloride for hemostasis, ointment and bandage applied, care instructions provided; (2) Discuss options. Calcipotriene cream daily; triamcinolone ointment 0.1% twice a day (prescription drug management). Review bathing, avoiding trauma to site, no picking.

Scenario 4: Here for a Total-Body Screening Examination

Medicare does not cover skin cancer screenings as a primary CC. Being worried or knowing someone with melanoma are not CCs that are covered. However, “spot of concern,” “changing mole,” or ”new growth” would be. Conversely, if the patient has a history of skin cancer, actinic keratoses, or other premalignant lesions, and/or is immunosuppressed or has a high-risk genetic syndrome, the visit may be covered if these factors are documented in the note.6

For the diagnosis, the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, code Z12.83—“encounter for screening for malignant neoplasm of skin”—is not an appropriate primary billing code. However, D48.5—“neoplasm of behavior of skin”—can be, unless there is a specific diagnosis you are able to make (eg, melanocytic nevus, seborrheic keratosis).6

Let’s look at documentation examples:

- CC: 1-year follow-up on basal cell carcinoma (BCC) excision and concern about a new spot on the nose.

- History: Notice new spot on the nose; due for annual follow-up and came early for nose lesion.

- Examination: Left ala with flesh-colored papule dermoscopically banal. Prior left back BCC excision site soft and supple. Total-body examination performed, except perianal and external genitalia, and is unremarkable.

- Impression: Fibrous papule of nose and prior BCC treatment site with no sign of recurrence.

- Plan: Reassure. Annual surveillance in 1 year.

Using what we have previously discussed, this would likely be considered CPT code 99212 (established patient office visit). However, it is important to ensure all concerns and treatment interventions are fully documented. Consider this fuller documentation with bolded additions:

- CC: 1-year follow-up on BCC excision and concern about a new spot on the nose.

- History: Notice new spot on the nose; due for annual follow-up and came early for nose lesion. Also unhappy with generally looking older.

- Examination: Left ala with flesh-colored papule dermoscopically banal. Prior left back BCC excision site soft and supple. Diffuse changes of chronic sun damage. Total-body examination performed, except perianal and external genitalia, and is unremarkable.

- Impression: Fibrous papule of nose and prior BCC treatment site with no sign of recurrence and heliodermatosis/chronic sun damage not at treat-ment goal.

- Plan: Reassure. Annual surveillance in 1 year. Over-the-counter broad-spectrum sun protection factor 30+ sunscreen daily.

This is better but still possibly confusing to an auditor. Consider instead with bolded additions to the changes to the impression:

- CC: 1-year follow-up on BCC excision and concern about a new spot on the nose.

- History: Notice new spot on the nose; due for annual follow-up and came early for nose lesion. Also unhappy with generally looking older.

- Examination: Left ala with flesh-colored papule dermoscopically banal. Prior left back BCC excision site soft and supple. Diffuse changes of chronic sun damage. Total-body examination performed, except perianal and external genitalia, and is unremarkable.

- Impression: Fibrous papule of nose (D22.39)7 and prior BCC treatment site with no sign of recurrence (Z85.828: “personal history of other malignant neoplasm of skin) and heliodermatosis/chronic sun damage not at treatment goal (L57.8: “other skin changes due to chronic exposure to nonionizing radiation”).

- Plan: Reassure. Annual surveillance 1 year. Over-the-counter broad-spectrum sun protection factor 30+ sunscreen daily.

We now have chronic heliodermatitis not at treatment goal, which is moderate (column 1, level 4), and the over-the-counter broad-spectrum sun protection factor 30+ sunscreen (column 1, low) would be best coded as CPT code 99213.

Final Thoughts

“Spot check” encounters are common dermatologic visits, both on their own and in combination with other concerns. With the updated E/M guidelines, it is crucial to clarify and streamline your documentation. In particular, utilize language clearly defining the number and complexity of problems, data to be reviewed and/or analyzed, and appropriate risk stratification to ensure appropriate reimbursement and minimize your difficulties with audits.

- American Medical Association. CPT evaluation and management (E/M) code and guideline changes; 2023. Accessed May 15, 2023. https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2023-e-m-descriptors-guidelines.pdf

- Flamm A, Siegel DM. Coding the “spot check”: part 1. Cutis. 2023;111:224-226. doi:10.12788/cutis.0762

- American Medical Association. Evaluation and management (E/M) coding. Accessed May 15, 2023. https://www.ama-assn.org/topics/evaluation-and-management-em-coding

- American Academy of Dermatology Association. Coding resource center. Accessed May 15, 2023. https://www.aad.org/member/practice/coding

- American Medical Association. CPT Professional Edition 2023. American Medical Association; 2022.

- Elizey Coding Solutions, Inc. Dermatology preventive/screening exam visit caution. Updated September 18, 2016. Accessed May 2, 2023. https://www.ellzeycodingsolutions.com/kb_results.asp?ID=9

- 2023 ICD-10-CM diagnosis code D22.39: melanocytic nevi of other parts of the face. Accessed May 2, 2023. https://www.icd10data.com/ICD10CM/Codes/C00-D49/D10-D36/D22-/D22.39

When the Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) evaluation and management (E/M) reporting rules changed dramatically in January 2021, “bullet counting” became unnecessary and the coding level became based on either the new medical decision making (MDM) table or time spent on all activities relating to the care of the patient on the day of the encounter. 1

To make your documentation more likely to pass audits, explicitly link parts of your documentation to CPT MDM descriptors. Part 1 of this series discussed how to approach the “spot check,” a commonly encountered chief concern (CC) within dermatology, with 2 scenarios presented.2 The American Medical Association3 and American Academy of Dermatology4 have provided education that focuses on how to report a given vignette, but specific examples of documentation with commentary are uncommon. In part 2, we describe how to best code an encounter that includes a “spot check” with other concerns.

Scenario 3: By the Way, Doc

A 34-year-old presents with a new spot on the left cheek that seems to be growing and changing shape rapidly. You examine the patient and discuss treatment options. The documentation reads as follows:

- CC: New spot on left cheek that seems to be growing and changing shape rapidly.

- History: No family history of skin cancer; concerned about scarring, no blood thinner.

- Examination: Irregular tan to brown to black 8-mm macule. No lymphadenopathy.

- Impression: Rule out melanoma (undiagnosed new problem with uncertain prognosis).

- Plan: Discuss risks, benefits, and alternatives, including biopsy (decision regarding minor surgery with identified patient or procedure risk factors) vs a noninvasive gene expression profiling (GEP) melanoma rule-out test. (Based on the decision you and the patient make, you also would document which option was chosen, so a biopsy would include your standard documentation, and if the GEP is chosen, you would simply state that this was chosen and performed.)

As you turn to leave the room, the patient says:“By the way, Doc, can you do anything about these

How would it be best to approach this scenario? It depends on which treatment option the patient chooses.

If you performed a noninvasive GEP melanoma rule-out test, the CPT reporting does not change with the addition of the new problem, and only the codes 99204 (new patient office or other outpatient visit) or 99214 (established patient office or other outpatient visit) would be reported. This would be because, with the original documentation, the number and complexity of problems would be an “undiagnosed new problem with uncertain prognosis,” which would be moderate complexity (column 1, level 4). There are no data that are reviewed or analyzed, which would be straightforward (column 2, level 2). For risk, the discussion of the biopsy as a diagnostic choice should include possible scarring, bleeding, pain, and infection, which would be best described as a decision regarding minor surgery with identified patient or procedure risk factors, given the identified patient concerns, making this of moderate complexity (column 3, level 4).1

Importantly, even if the procedure is not chosen as the final treatment plan, the discussion regarding the surgery, including the risks, benefits, and alternatives, can still count toward this category in the MDM table. Therefore, in this scenario, documentation would best fit with CPT code 99204 for a new patient or 99214 for an established patient. The addition of the psoriasis diagnosis would not change the level of service but also should include documentation of the psoriasis as medically necessary.

However, if you perform the biopsy, then the documentation above would only allow reporting the biopsy, as the decision to perform a 0- or 10-day global procedure is “bundled” with the procedure if performed on the same date of service. Therefore, with the addition of the psoriasis diagnosis, you would now use a separate E/M code to report the psoriasis. You must append a modifier −25 to the E/M code to certify that you are dealing with a separate and discrete problem with no overlap in physician work.

Clearly you also have an E/M to report. But what level? Is this chronic? Yes, as CPT clearly defines chronic as “[a] problem with an expected duration of at least one year or until the death of the patient.”1,5

But is this stable progressive or showing side effects of treatment? “‘Stable’ for the purposes of categorizing MDM is defined by the specific treatment goals for an individual patient. A patient who is not at his or her treatment goal is not stable, even if the condition has not changed and there is no short-term threat to life or function,” according to the CPT descriptors. Therefore, in this scenario, the documentation would best fit a chronic illness with exacerbation, progression, or side effects of treatment (column 1, level 4), which is of moderate complexity.1

But what about column 3, where we look at risks of testing and treatment? This would depend on the type of treatment given. If an over-the-counter product such as a tar gel is recommended, this is a low risk (column 3, level 3), which would mean this lower value determines the E/M code to be 99213 or 99203 depending on whether this is an established or new patient, respectively. If we treat with a prescription medication such as a topical corticosteroid, we are providing prescription drug management (column 3, level 4), which is moderate risk, and we would use codes 99204 or 99214, assuming we document appropriately. Again, including the CPT terminology of “not at treatment goal” in your impression and “prescription drug management” in your plan tells an auditor what you are thinking and doing.1,5

The Takeaway—Clearly if a GEP is performed, there is a single CPT code used—99204 or 99214. If the biopsy is performed, there would be a biopsy code and an E/M code with a modifier −25 attached to the latter. For the documentation below, a 99204 or 99214 would be the chosen E/M code:

- CC: (1) New spot on left cheek that seems to be growing and changing shape rapidly; (2) Silvery spots on elbows, knees, and buttocks for which patient desires treatment.

- History: No family history of skin cancer; concerned about scarring, no blood thinner. Mom has psoriasis. Tried petroleum jelly on scaly areas but no better.

- Examination: Irregular tan to brown to black 8-mm macule. No lymphadenopathy. Silver scaly erythematous plaques on elbows, knees, sacrum.

- Impression: (1) Rule out melanoma (undiagnosed new problem with uncertain prognosis); (2) Psoriasis (chronic disease not at treatment goal).

- Plan: (1) Discuss risks, benefits, and alternatives, including biopsy (decision regarding minor surgery with identified patient or procedure risk factors) vs a noninvasive GEP melanoma rule-out test. Patient wants biopsy. Consent, biopsy via shave technique. Lidocaine hydrochloride 1% with epinephrine 1 cc, prepare and drape, aluminum chloride for hemostasis, ointment and bandage applied, care instructions provided; (2) Discuss options. Calcipotriene cream daily; triamcinolone ointment 0.1% twice a day (prescription drug management). Review bathing, avoiding trauma to site, no picking.

Scenario 4: Here for a Total-Body Screening Examination

Medicare does not cover skin cancer screenings as a primary CC. Being worried or knowing someone with melanoma are not CCs that are covered. However, “spot of concern,” “changing mole,” or ”new growth” would be. Conversely, if the patient has a history of skin cancer, actinic keratoses, or other premalignant lesions, and/or is immunosuppressed or has a high-risk genetic syndrome, the visit may be covered if these factors are documented in the note.6

For the diagnosis, the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, code Z12.83—“encounter for screening for malignant neoplasm of skin”—is not an appropriate primary billing code. However, D48.5—“neoplasm of behavior of skin”—can be, unless there is a specific diagnosis you are able to make (eg, melanocytic nevus, seborrheic keratosis).6

Let’s look at documentation examples:

- CC: 1-year follow-up on basal cell carcinoma (BCC) excision and concern about a new spot on the nose.

- History: Notice new spot on the nose; due for annual follow-up and came early for nose lesion.

- Examination: Left ala with flesh-colored papule dermoscopically banal. Prior left back BCC excision site soft and supple. Total-body examination performed, except perianal and external genitalia, and is unremarkable.

- Impression: Fibrous papule of nose and prior BCC treatment site with no sign of recurrence.

- Plan: Reassure. Annual surveillance in 1 year.

Using what we have previously discussed, this would likely be considered CPT code 99212 (established patient office visit). However, it is important to ensure all concerns and treatment interventions are fully documented. Consider this fuller documentation with bolded additions:

- CC: 1-year follow-up on BCC excision and concern about a new spot on the nose.

- History: Notice new spot on the nose; due for annual follow-up and came early for nose lesion. Also unhappy with generally looking older.

- Examination: Left ala with flesh-colored papule dermoscopically banal. Prior left back BCC excision site soft and supple. Diffuse changes of chronic sun damage. Total-body examination performed, except perianal and external genitalia, and is unremarkable.

- Impression: Fibrous papule of nose and prior BCC treatment site with no sign of recurrence and heliodermatosis/chronic sun damage not at treat-ment goal.

- Plan: Reassure. Annual surveillance in 1 year. Over-the-counter broad-spectrum sun protection factor 30+ sunscreen daily.

This is better but still possibly confusing to an auditor. Consider instead with bolded additions to the changes to the impression:

- CC: 1-year follow-up on BCC excision and concern about a new spot on the nose.

- History: Notice new spot on the nose; due for annual follow-up and came early for nose lesion. Also unhappy with generally looking older.

- Examination: Left ala with flesh-colored papule dermoscopically banal. Prior left back BCC excision site soft and supple. Diffuse changes of chronic sun damage. Total-body examination performed, except perianal and external genitalia, and is unremarkable.

- Impression: Fibrous papule of nose (D22.39)7 and prior BCC treatment site with no sign of recurrence (Z85.828: “personal history of other malignant neoplasm of skin) and heliodermatosis/chronic sun damage not at treatment goal (L57.8: “other skin changes due to chronic exposure to nonionizing radiation”).

- Plan: Reassure. Annual surveillance 1 year. Over-the-counter broad-spectrum sun protection factor 30+ sunscreen daily.

We now have chronic heliodermatitis not at treatment goal, which is moderate (column 1, level 4), and the over-the-counter broad-spectrum sun protection factor 30+ sunscreen (column 1, low) would be best coded as CPT code 99213.

Final Thoughts

“Spot check” encounters are common dermatologic visits, both on their own and in combination with other concerns. With the updated E/M guidelines, it is crucial to clarify and streamline your documentation. In particular, utilize language clearly defining the number and complexity of problems, data to be reviewed and/or analyzed, and appropriate risk stratification to ensure appropriate reimbursement and minimize your difficulties with audits.

When the Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) evaluation and management (E/M) reporting rules changed dramatically in January 2021, “bullet counting” became unnecessary and the coding level became based on either the new medical decision making (MDM) table or time spent on all activities relating to the care of the patient on the day of the encounter. 1

To make your documentation more likely to pass audits, explicitly link parts of your documentation to CPT MDM descriptors. Part 1 of this series discussed how to approach the “spot check,” a commonly encountered chief concern (CC) within dermatology, with 2 scenarios presented.2 The American Medical Association3 and American Academy of Dermatology4 have provided education that focuses on how to report a given vignette, but specific examples of documentation with commentary are uncommon. In part 2, we describe how to best code an encounter that includes a “spot check” with other concerns.

Scenario 3: By the Way, Doc

A 34-year-old presents with a new spot on the left cheek that seems to be growing and changing shape rapidly. You examine the patient and discuss treatment options. The documentation reads as follows:

- CC: New spot on left cheek that seems to be growing and changing shape rapidly.

- History: No family history of skin cancer; concerned about scarring, no blood thinner.

- Examination: Irregular tan to brown to black 8-mm macule. No lymphadenopathy.

- Impression: Rule out melanoma (undiagnosed new problem with uncertain prognosis).

- Plan: Discuss risks, benefits, and alternatives, including biopsy (decision regarding minor surgery with identified patient or procedure risk factors) vs a noninvasive gene expression profiling (GEP) melanoma rule-out test. (Based on the decision you and the patient make, you also would document which option was chosen, so a biopsy would include your standard documentation, and if the GEP is chosen, you would simply state that this was chosen and performed.)

As you turn to leave the room, the patient says:“By the way, Doc, can you do anything about these

How would it be best to approach this scenario? It depends on which treatment option the patient chooses.

If you performed a noninvasive GEP melanoma rule-out test, the CPT reporting does not change with the addition of the new problem, and only the codes 99204 (new patient office or other outpatient visit) or 99214 (established patient office or other outpatient visit) would be reported. This would be because, with the original documentation, the number and complexity of problems would be an “undiagnosed new problem with uncertain prognosis,” which would be moderate complexity (column 1, level 4). There are no data that are reviewed or analyzed, which would be straightforward (column 2, level 2). For risk, the discussion of the biopsy as a diagnostic choice should include possible scarring, bleeding, pain, and infection, which would be best described as a decision regarding minor surgery with identified patient or procedure risk factors, given the identified patient concerns, making this of moderate complexity (column 3, level 4).1

Importantly, even if the procedure is not chosen as the final treatment plan, the discussion regarding the surgery, including the risks, benefits, and alternatives, can still count toward this category in the MDM table. Therefore, in this scenario, documentation would best fit with CPT code 99204 for a new patient or 99214 for an established patient. The addition of the psoriasis diagnosis would not change the level of service but also should include documentation of the psoriasis as medically necessary.

However, if you perform the biopsy, then the documentation above would only allow reporting the biopsy, as the decision to perform a 0- or 10-day global procedure is “bundled” with the procedure if performed on the same date of service. Therefore, with the addition of the psoriasis diagnosis, you would now use a separate E/M code to report the psoriasis. You must append a modifier −25 to the E/M code to certify that you are dealing with a separate and discrete problem with no overlap in physician work.

Clearly you also have an E/M to report. But what level? Is this chronic? Yes, as CPT clearly defines chronic as “[a] problem with an expected duration of at least one year or until the death of the patient.”1,5

But is this stable progressive or showing side effects of treatment? “‘Stable’ for the purposes of categorizing MDM is defined by the specific treatment goals for an individual patient. A patient who is not at his or her treatment goal is not stable, even if the condition has not changed and there is no short-term threat to life or function,” according to the CPT descriptors. Therefore, in this scenario, the documentation would best fit a chronic illness with exacerbation, progression, or side effects of treatment (column 1, level 4), which is of moderate complexity.1

But what about column 3, where we look at risks of testing and treatment? This would depend on the type of treatment given. If an over-the-counter product such as a tar gel is recommended, this is a low risk (column 3, level 3), which would mean this lower value determines the E/M code to be 99213 or 99203 depending on whether this is an established or new patient, respectively. If we treat with a prescription medication such as a topical corticosteroid, we are providing prescription drug management (column 3, level 4), which is moderate risk, and we would use codes 99204 or 99214, assuming we document appropriately. Again, including the CPT terminology of “not at treatment goal” in your impression and “prescription drug management” in your plan tells an auditor what you are thinking and doing.1,5

The Takeaway—Clearly if a GEP is performed, there is a single CPT code used—99204 or 99214. If the biopsy is performed, there would be a biopsy code and an E/M code with a modifier −25 attached to the latter. For the documentation below, a 99204 or 99214 would be the chosen E/M code:

- CC: (1) New spot on left cheek that seems to be growing and changing shape rapidly; (2) Silvery spots on elbows, knees, and buttocks for which patient desires treatment.

- History: No family history of skin cancer; concerned about scarring, no blood thinner. Mom has psoriasis. Tried petroleum jelly on scaly areas but no better.

- Examination: Irregular tan to brown to black 8-mm macule. No lymphadenopathy. Silver scaly erythematous plaques on elbows, knees, sacrum.

- Impression: (1) Rule out melanoma (undiagnosed new problem with uncertain prognosis); (2) Psoriasis (chronic disease not at treatment goal).

- Plan: (1) Discuss risks, benefits, and alternatives, including biopsy (decision regarding minor surgery with identified patient or procedure risk factors) vs a noninvasive GEP melanoma rule-out test. Patient wants biopsy. Consent, biopsy via shave technique. Lidocaine hydrochloride 1% with epinephrine 1 cc, prepare and drape, aluminum chloride for hemostasis, ointment and bandage applied, care instructions provided; (2) Discuss options. Calcipotriene cream daily; triamcinolone ointment 0.1% twice a day (prescription drug management). Review bathing, avoiding trauma to site, no picking.

Scenario 4: Here for a Total-Body Screening Examination

Medicare does not cover skin cancer screenings as a primary CC. Being worried or knowing someone with melanoma are not CCs that are covered. However, “spot of concern,” “changing mole,” or ”new growth” would be. Conversely, if the patient has a history of skin cancer, actinic keratoses, or other premalignant lesions, and/or is immunosuppressed or has a high-risk genetic syndrome, the visit may be covered if these factors are documented in the note.6

For the diagnosis, the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, code Z12.83—“encounter for screening for malignant neoplasm of skin”—is not an appropriate primary billing code. However, D48.5—“neoplasm of behavior of skin”—can be, unless there is a specific diagnosis you are able to make (eg, melanocytic nevus, seborrheic keratosis).6

Let’s look at documentation examples:

- CC: 1-year follow-up on basal cell carcinoma (BCC) excision and concern about a new spot on the nose.

- History: Notice new spot on the nose; due for annual follow-up and came early for nose lesion.

- Examination: Left ala with flesh-colored papule dermoscopically banal. Prior left back BCC excision site soft and supple. Total-body examination performed, except perianal and external genitalia, and is unremarkable.

- Impression: Fibrous papule of nose and prior BCC treatment site with no sign of recurrence.

- Plan: Reassure. Annual surveillance in 1 year.

Using what we have previously discussed, this would likely be considered CPT code 99212 (established patient office visit). However, it is important to ensure all concerns and treatment interventions are fully documented. Consider this fuller documentation with bolded additions:

- CC: 1-year follow-up on BCC excision and concern about a new spot on the nose.

- History: Notice new spot on the nose; due for annual follow-up and came early for nose lesion. Also unhappy with generally looking older.

- Examination: Left ala with flesh-colored papule dermoscopically banal. Prior left back BCC excision site soft and supple. Diffuse changes of chronic sun damage. Total-body examination performed, except perianal and external genitalia, and is unremarkable.

- Impression: Fibrous papule of nose and prior BCC treatment site with no sign of recurrence and heliodermatosis/chronic sun damage not at treat-ment goal.

- Plan: Reassure. Annual surveillance in 1 year. Over-the-counter broad-spectrum sun protection factor 30+ sunscreen daily.

This is better but still possibly confusing to an auditor. Consider instead with bolded additions to the changes to the impression:

- CC: 1-year follow-up on BCC excision and concern about a new spot on the nose.

- History: Notice new spot on the nose; due for annual follow-up and came early for nose lesion. Also unhappy with generally looking older.

- Examination: Left ala with flesh-colored papule dermoscopically banal. Prior left back BCC excision site soft and supple. Diffuse changes of chronic sun damage. Total-body examination performed, except perianal and external genitalia, and is unremarkable.

- Impression: Fibrous papule of nose (D22.39)7 and prior BCC treatment site with no sign of recurrence (Z85.828: “personal history of other malignant neoplasm of skin) and heliodermatosis/chronic sun damage not at treatment goal (L57.8: “other skin changes due to chronic exposure to nonionizing radiation”).

- Plan: Reassure. Annual surveillance 1 year. Over-the-counter broad-spectrum sun protection factor 30+ sunscreen daily.

We now have chronic heliodermatitis not at treatment goal, which is moderate (column 1, level 4), and the over-the-counter broad-spectrum sun protection factor 30+ sunscreen (column 1, low) would be best coded as CPT code 99213.

Final Thoughts

“Spot check” encounters are common dermatologic visits, both on their own and in combination with other concerns. With the updated E/M guidelines, it is crucial to clarify and streamline your documentation. In particular, utilize language clearly defining the number and complexity of problems, data to be reviewed and/or analyzed, and appropriate risk stratification to ensure appropriate reimbursement and minimize your difficulties with audits.

- American Medical Association. CPT evaluation and management (E/M) code and guideline changes; 2023. Accessed May 15, 2023. https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2023-e-m-descriptors-guidelines.pdf

- Flamm A, Siegel DM. Coding the “spot check”: part 1. Cutis. 2023;111:224-226. doi:10.12788/cutis.0762

- American Medical Association. Evaluation and management (E/M) coding. Accessed May 15, 2023. https://www.ama-assn.org/topics/evaluation-and-management-em-coding

- American Academy of Dermatology Association. Coding resource center. Accessed May 15, 2023. https://www.aad.org/member/practice/coding

- American Medical Association. CPT Professional Edition 2023. American Medical Association; 2022.

- Elizey Coding Solutions, Inc. Dermatology preventive/screening exam visit caution. Updated September 18, 2016. Accessed May 2, 2023. https://www.ellzeycodingsolutions.com/kb_results.asp?ID=9

- 2023 ICD-10-CM diagnosis code D22.39: melanocytic nevi of other parts of the face. Accessed May 2, 2023. https://www.icd10data.com/ICD10CM/Codes/C00-D49/D10-D36/D22-/D22.39

- American Medical Association. CPT evaluation and management (E/M) code and guideline changes; 2023. Accessed May 15, 2023. https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2023-e-m-descriptors-guidelines.pdf

- Flamm A, Siegel DM. Coding the “spot check”: part 1. Cutis. 2023;111:224-226. doi:10.12788/cutis.0762

- American Medical Association. Evaluation and management (E/M) coding. Accessed May 15, 2023. https://www.ama-assn.org/topics/evaluation-and-management-em-coding

- American Academy of Dermatology Association. Coding resource center. Accessed May 15, 2023. https://www.aad.org/member/practice/coding

- American Medical Association. CPT Professional Edition 2023. American Medical Association; 2022.

- Elizey Coding Solutions, Inc. Dermatology preventive/screening exam visit caution. Updated September 18, 2016. Accessed May 2, 2023. https://www.ellzeycodingsolutions.com/kb_results.asp?ID=9

- 2023 ICD-10-CM diagnosis code D22.39: melanocytic nevi of other parts of the face. Accessed May 2, 2023. https://www.icd10data.com/ICD10CM/Codes/C00-D49/D10-D36/D22-/D22.39

Practice Points

- Clear documentation that reflects your thought process is an important component of effective coding and billing.

- Include Current Procedural Terminology–defined language within documentation to help ensure appropriate reimbursement and decrease the risk of audits.

Coding the “Spot Check”: Part 1

On January 1, 2021, the Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) evaluation and management (E/M) reporting rules changed dramatically, with “bullet counting” no longer necessary and the coding level now based on either the new medical decision making (MDM) table or time spent on all activities relating to the care of the patient on the day of the encounter.1 This is described in the CPT Professional Edition 2023, a book every practitioner should review annually.2 In particular, every provider should read and reread pages 1 to 14—and beyond if you provide services beyond standard office visits. These changes were made with the intent to simplify the process of documentation and allow a provider to spend more time with patients, though there is still a paucity of data related to whether the new system achieves these aims.

The general rule of reporting work with CPT codes can be simply stated—“Document what you did, do what you documented, and report that which is medically necessary” (David McCafferey, MD, personal communication)—and you should never have any difficulty with audits. Unfortunately, the new system does not let an auditor, who typically lacks a medical degree, audit effectively unless they have a clear understanding of diseases and their stages. Many medical societies, including the American Medical Association3 and American Academy of Dermatology,4 have provided education that focuses on how to report a given vignette, but specific examples of documentation with commentary are uncommon.

To make your documentation more likely to pass audits, explicitly link parts of your documentation to CPT MDM descriptors. We offer scenarios and tips. In part 1 of this series, we discuss how to approach the “spot check,” a commonly encountered chief concern (CC) within dermatology.

A 34-year-old presents with a new spot on the left cheek that seems to be growing and changing shape rapidly. You examine the patient and discuss treatment options. The documentation reads as follows:

• CC: New spot on left cheek that seems to be growing and changing shape rapidly

• History: No family history of skin cancer; concerned about scarring, no blood thinner

• Examination: Irregular tan to brown to black 8-mm macule. No lymphadenopathy

• Impression: rule out melanoma.

• Plan:

As was the case before 2021, you still need a CC, along with a medically (and medicolegally) appropriate history and physical examination. A diagnostic impression and treatment plan also should be included.

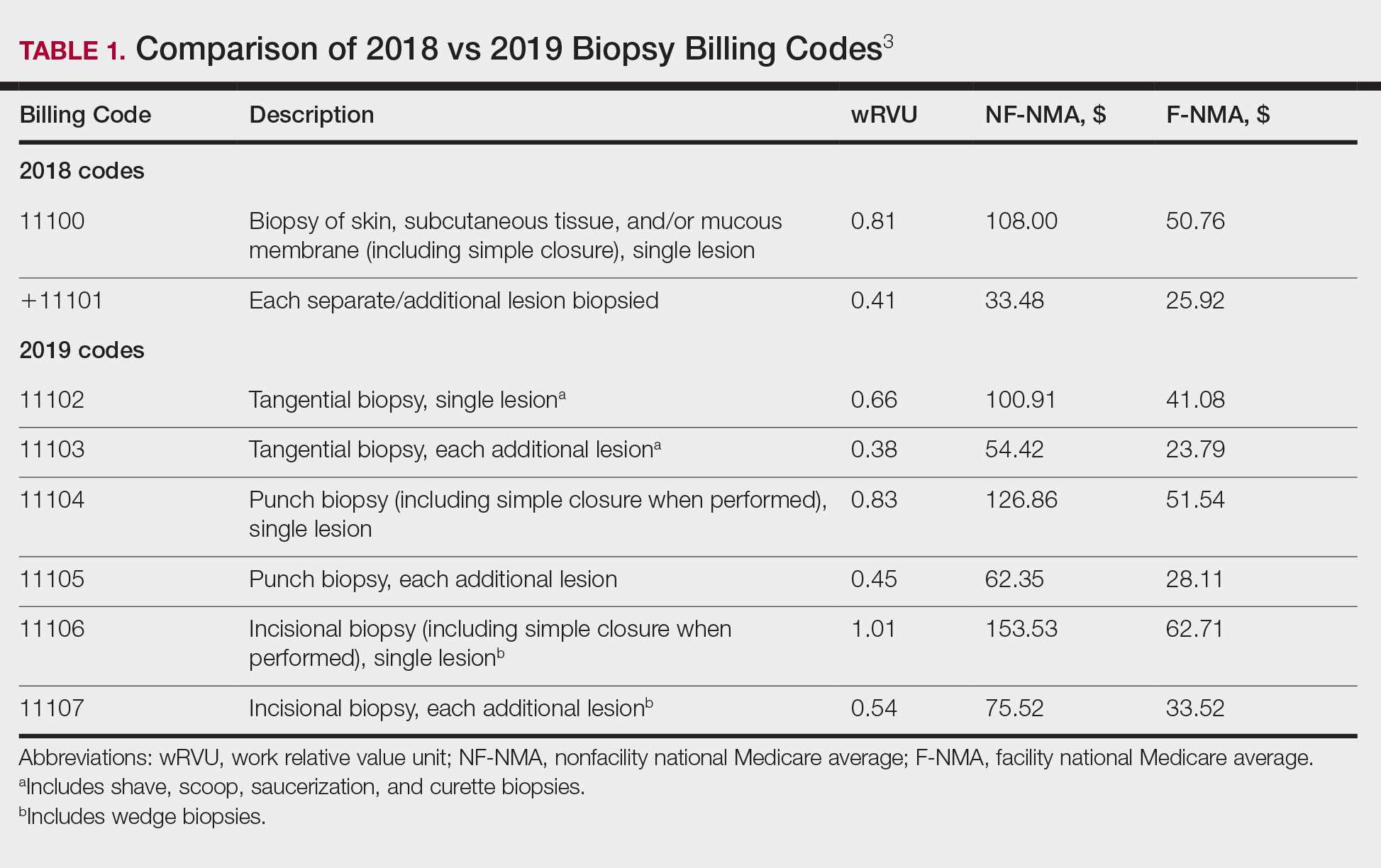

In this situation, reporting is straightforward. There is no separate E/M visit; only the CPT code 11102 for tangential biopsy is reported. An International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision code of D48.5 (neoplasm of uncertain behavior of skin) will be included.

Why no E/M code? This is because the biopsy includes preservice and postservice time and work that would be double reported with the E/M. Remember that the preservice work would include any history and physical examination related to the area to be biopsied.

Specifically, preservice work includes:

Inspect and palpate lesion to assess surface size, subcutaneous depth and extension, and whether fixed to underlying structures. Select the most representative and appropriate site to obtain specimen. Examine draining lymph node basins. Discuss need for skin biopsy and biopsy technique options. Describe the tangential biopsy procedure method and expected result and the potential for inconclusive pathology result. Review procedural risks, including bleeding, pain, edema, infection, delayed healing, scarring, and hyper- or hypopigmentation.5

Postservice work includes:

Instruct patient and family on postoperative wound care and dressing changes, as well as problems such as bleeding or pain and restrictions on activities, and follow-up care. Provide prescriptions for pain and antibiotics as necessary. Advise patient and family when results will be available and how they will be communicated. The pathology request form is filled out and signed by the physician. Complete medical record and communicate procedure/results to referring physician as appropriate.5

The Takeaway—Procedure codes include preservice and postservice work. If additional work for the procedure is not documented beyond that, an E/M cannot be included in the encounter.

Scenario 2: What If We Don’t Biopsy?

• CC: New spot on left cheek that seems to be growing and changing shape rapidly.

• History: No family history of skin cancer; concerned about scarring, no blood thinner.

• Examination: Irregular tan to brown to black 8-mm macule. No lymphadenopathy.

• Impression: rule out melanoma.

• Plan: Review risk, benefits, and alternative options. Schedule biopsy. Discuss unique risk factor of sebaceous peau d’orange skin more prone to contour defects after biopsy.

When determining the coding level for this scenario by MDM, 3 components must be considered: number and complexity of problems addressed at the encounter (column 1), amount and/or complexity of data to be reviewed and analyzed (column 2), and risk of complications and/or morbidity or mortality of patient management (column 3).1 There are no data that are reviewed, so the auditor will assume minimal data to be reviewed and/or analyzed (level 2, row 2 in the MDM table). However, there may be a lot of variation in how an auditor would address the number and complexity of problems (level 1). Consider that you must explicitly state what you are thinking, as an auditor may not know melanoma is a life-threatening diagnosis. From the perspective of the auditor, could this be a:

• Self-limited or minor problem (level 2, or minimal problem in the MDM table)?1

• Stable chronic illness (level 3, or low-level problem)?1

• Undiagnosed new problem with uncertain prognosis (level 4, or moderate level problem)?1

• Acute illness with systemic symptoms (level 4, or moderate level problem)?1

• Acute or chronic illness or injury that poses a threat to life or bodily function (level 5, or high-level problem)?1

• All of the above?

Similarly, there may be variation in how the risk (column 3) would be interpreted in this scenario. The treatment gives no guidance, so the auditor may assume this has a minimal risk of morbidity (level 2) or possibly a low risk of morbidity from additional diagnostic testing or treatment (level 3), as opposed to a moderate risk of morbidity (level 4).1The Takeaway—In the auditor’s mind, this could be a straightforward (CPT codes 99202/99212) or lowlevel (99203/99213) visit as opposed to a moderate-level (99204/99214) visit. From the above documentation, an auditor would not be able to tell what you are thinking, and you can be assured they will not look further into the diagnosis or treatment to learn. That is not their job. So, let us clarify by explicitly stating what you are thinking in the context of the MDM grid.

Modified Scenario 2: A Funny-Looking New Spot With MDM Descriptors to Guide an Auditor

Below are modifications to the documentation for scenario 2 to guide an auditor:

• CC: New spot on left cheek that seems to be growing and changing shape rapidly.

• History: No family history of skin cancer; concerned about scarring, no blood thinner.

• Examination: Irregular tan to brown to black 8-mm macule. No lymphadenopathy.

• Impression: rule out melanoma

• Plan: Discuss risks, benefits, and alternatives, including biopsy (

In this scenario, the level of MDM is much more clearly documented (as bolded above).

The number and complexity of problems would be an undiagnosed new problem with uncertain prognosis, which would be moderate complexity (column 1, level 4).1 There are no data that are reviewed or analyzed, which would be straightforward (column 2, level 2). For risk, the discussion of the biopsy as part of the diagnostic choices should include discussion of possible scarring, bleeding, pain, and infection, which would be considered best described as a decision regarding minor surgery with identified patient or procedure risk factors, which would make this of moderate complexity (column 3, level 4).1

Importantly, even if the procedure is not chosen as the final treatment plan, the discussion regarding the surgery, including the risks, benefits, and alternatives, can still count toward this category in the MDM table. Therefore, in this scenario with the updated and clarified documentation, this would be reported as CPT code 99204 for a new patient, while an established patient would be 99214.

Scenario 1 Revisited: A Funny-Looking New Spot

Below is scenario 1 with enhanced documentation, now applied to our procedure-only visit.

• CC: New spot on left cheek that seems to be growing and changing shape rapidly.

• History: No family history of skin cancer; concerned about scarring, no blood thinner.

• Examination: Irregular tan to brown to black 8-mm macule. No lymphadenopathy.

• Impression: rule out melanoma (undiagnosed new problem with uncertain prognosis).

• Plan: Discuss risks, benefits, and alternatives, including biopsy (decision regarding minor surgery with identified patient or procedure risk factors) vs a noninvasive 2 gene expression profiling melanoma rule-out test. Patient wants biopsy. Consent, biopsy via shave technique. Lidocaine hydrochloride 1% with epinephrine, 1 cc, prepare and drape, hemostasis obtained, ointment and bandage applied, and care instructions provided.

This documentation would only allow reporting the biopsy as in Scenario 1, as the decision to perform a 0- or 10-day global procedure is bundled with the procedure if performed on the same date of service.

Final Thoughts

Spot checks are commonly encountered dermatologic visits. With the updated E/M guidelines, clarifying and streamlining your documentation is crucial. In particular, utilizing language that clearly defines number and complexity of problems, amount and/or complexity of data to be reviewed and analyzed, and appropriate risk stratification is crucial to ensuring appropriate reimbursement and minimizing your pain with audits.

- American Medical Association. CPT evaluation and management (E/M) code and guideline changes; 2023. Accessed April 13, 2023. https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2023-e-m-descriptors-guidelines.pdf

- American Medical Association. CPT Professional Edition 2023. American Medical Association; 2022.

- American Medical Association. Evaluation and management (E/M) coding. Accessed April 25, 2023. https://www.ama-assn.org/topics/evaluation-and-management-em-coding

- American Academy of Dermatology Association. Coding resource center. Accessed April 13, 2023. https://www.aad.org/member/practice/coding

- American Medical Association. RBVS DataManager Online. Accessed April 13, 2023. https://commerce.ama-assn.org/store/ui/catalog/productDetail?product_id=prod280002&navAction=push

On January 1, 2021, the Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) evaluation and management (E/M) reporting rules changed dramatically, with “bullet counting” no longer necessary and the coding level now based on either the new medical decision making (MDM) table or time spent on all activities relating to the care of the patient on the day of the encounter.1 This is described in the CPT Professional Edition 2023, a book every practitioner should review annually.2 In particular, every provider should read and reread pages 1 to 14—and beyond if you provide services beyond standard office visits. These changes were made with the intent to simplify the process of documentation and allow a provider to spend more time with patients, though there is still a paucity of data related to whether the new system achieves these aims.

The general rule of reporting work with CPT codes can be simply stated—“Document what you did, do what you documented, and report that which is medically necessary” (David McCafferey, MD, personal communication)—and you should never have any difficulty with audits. Unfortunately, the new system does not let an auditor, who typically lacks a medical degree, audit effectively unless they have a clear understanding of diseases and their stages. Many medical societies, including the American Medical Association3 and American Academy of Dermatology,4 have provided education that focuses on how to report a given vignette, but specific examples of documentation with commentary are uncommon.

To make your documentation more likely to pass audits, explicitly link parts of your documentation to CPT MDM descriptors. We offer scenarios and tips. In part 1 of this series, we discuss how to approach the “spot check,” a commonly encountered chief concern (CC) within dermatology.

A 34-year-old presents with a new spot on the left cheek that seems to be growing and changing shape rapidly. You examine the patient and discuss treatment options. The documentation reads as follows:

• CC: New spot on left cheek that seems to be growing and changing shape rapidly

• History: No family history of skin cancer; concerned about scarring, no blood thinner

• Examination: Irregular tan to brown to black 8-mm macule. No lymphadenopathy

• Impression: rule out melanoma.

• Plan:

As was the case before 2021, you still need a CC, along with a medically (and medicolegally) appropriate history and physical examination. A diagnostic impression and treatment plan also should be included.

In this situation, reporting is straightforward. There is no separate E/M visit; only the CPT code 11102 for tangential biopsy is reported. An International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision code of D48.5 (neoplasm of uncertain behavior of skin) will be included.

Why no E/M code? This is because the biopsy includes preservice and postservice time and work that would be double reported with the E/M. Remember that the preservice work would include any history and physical examination related to the area to be biopsied.

Specifically, preservice work includes:

Inspect and palpate lesion to assess surface size, subcutaneous depth and extension, and whether fixed to underlying structures. Select the most representative and appropriate site to obtain specimen. Examine draining lymph node basins. Discuss need for skin biopsy and biopsy technique options. Describe the tangential biopsy procedure method and expected result and the potential for inconclusive pathology result. Review procedural risks, including bleeding, pain, edema, infection, delayed healing, scarring, and hyper- or hypopigmentation.5

Postservice work includes:

Instruct patient and family on postoperative wound care and dressing changes, as well as problems such as bleeding or pain and restrictions on activities, and follow-up care. Provide prescriptions for pain and antibiotics as necessary. Advise patient and family when results will be available and how they will be communicated. The pathology request form is filled out and signed by the physician. Complete medical record and communicate procedure/results to referring physician as appropriate.5

The Takeaway—Procedure codes include preservice and postservice work. If additional work for the procedure is not documented beyond that, an E/M cannot be included in the encounter.

Scenario 2: What If We Don’t Biopsy?

• CC: New spot on left cheek that seems to be growing and changing shape rapidly.

• History: No family history of skin cancer; concerned about scarring, no blood thinner.

• Examination: Irregular tan to brown to black 8-mm macule. No lymphadenopathy.

• Impression: rule out melanoma.

• Plan: Review risk, benefits, and alternative options. Schedule biopsy. Discuss unique risk factor of sebaceous peau d’orange skin more prone to contour defects after biopsy.

When determining the coding level for this scenario by MDM, 3 components must be considered: number and complexity of problems addressed at the encounter (column 1), amount and/or complexity of data to be reviewed and analyzed (column 2), and risk of complications and/or morbidity or mortality of patient management (column 3).1 There are no data that are reviewed, so the auditor will assume minimal data to be reviewed and/or analyzed (level 2, row 2 in the MDM table). However, there may be a lot of variation in how an auditor would address the number and complexity of problems (level 1). Consider that you must explicitly state what you are thinking, as an auditor may not know melanoma is a life-threatening diagnosis. From the perspective of the auditor, could this be a:

• Self-limited or minor problem (level 2, or minimal problem in the MDM table)?1

• Stable chronic illness (level 3, or low-level problem)?1

• Undiagnosed new problem with uncertain prognosis (level 4, or moderate level problem)?1

• Acute illness with systemic symptoms (level 4, or moderate level problem)?1

• Acute or chronic illness or injury that poses a threat to life or bodily function (level 5, or high-level problem)?1

• All of the above?

Similarly, there may be variation in how the risk (column 3) would be interpreted in this scenario. The treatment gives no guidance, so the auditor may assume this has a minimal risk of morbidity (level 2) or possibly a low risk of morbidity from additional diagnostic testing or treatment (level 3), as opposed to a moderate risk of morbidity (level 4).1The Takeaway—In the auditor’s mind, this could be a straightforward (CPT codes 99202/99212) or lowlevel (99203/99213) visit as opposed to a moderate-level (99204/99214) visit. From the above documentation, an auditor would not be able to tell what you are thinking, and you can be assured they will not look further into the diagnosis or treatment to learn. That is not their job. So, let us clarify by explicitly stating what you are thinking in the context of the MDM grid.

Modified Scenario 2: A Funny-Looking New Spot With MDM Descriptors to Guide an Auditor

Below are modifications to the documentation for scenario 2 to guide an auditor:

• CC: New spot on left cheek that seems to be growing and changing shape rapidly.

• History: No family history of skin cancer; concerned about scarring, no blood thinner.

• Examination: Irregular tan to brown to black 8-mm macule. No lymphadenopathy.

• Impression: rule out melanoma

• Plan: Discuss risks, benefits, and alternatives, including biopsy (

In this scenario, the level of MDM is much more clearly documented (as bolded above).

The number and complexity of problems would be an undiagnosed new problem with uncertain prognosis, which would be moderate complexity (column 1, level 4).1 There are no data that are reviewed or analyzed, which would be straightforward (column 2, level 2). For risk, the discussion of the biopsy as part of the diagnostic choices should include discussion of possible scarring, bleeding, pain, and infection, which would be considered best described as a decision regarding minor surgery with identified patient or procedure risk factors, which would make this of moderate complexity (column 3, level 4).1

Importantly, even if the procedure is not chosen as the final treatment plan, the discussion regarding the surgery, including the risks, benefits, and alternatives, can still count toward this category in the MDM table. Therefore, in this scenario with the updated and clarified documentation, this would be reported as CPT code 99204 for a new patient, while an established patient would be 99214.

Scenario 1 Revisited: A Funny-Looking New Spot

Below is scenario 1 with enhanced documentation, now applied to our procedure-only visit.

• CC: New spot on left cheek that seems to be growing and changing shape rapidly.

• History: No family history of skin cancer; concerned about scarring, no blood thinner.

• Examination: Irregular tan to brown to black 8-mm macule. No lymphadenopathy.

• Impression: rule out melanoma (undiagnosed new problem with uncertain prognosis).

• Plan: Discuss risks, benefits, and alternatives, including biopsy (decision regarding minor surgery with identified patient or procedure risk factors) vs a noninvasive 2 gene expression profiling melanoma rule-out test. Patient wants biopsy. Consent, biopsy via shave technique. Lidocaine hydrochloride 1% with epinephrine, 1 cc, prepare and drape, hemostasis obtained, ointment and bandage applied, and care instructions provided.

This documentation would only allow reporting the biopsy as in Scenario 1, as the decision to perform a 0- or 10-day global procedure is bundled with the procedure if performed on the same date of service.

Final Thoughts

Spot checks are commonly encountered dermatologic visits. With the updated E/M guidelines, clarifying and streamlining your documentation is crucial. In particular, utilizing language that clearly defines number and complexity of problems, amount and/or complexity of data to be reviewed and analyzed, and appropriate risk stratification is crucial to ensuring appropriate reimbursement and minimizing your pain with audits.

On January 1, 2021, the Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) evaluation and management (E/M) reporting rules changed dramatically, with “bullet counting” no longer necessary and the coding level now based on either the new medical decision making (MDM) table or time spent on all activities relating to the care of the patient on the day of the encounter.1 This is described in the CPT Professional Edition 2023, a book every practitioner should review annually.2 In particular, every provider should read and reread pages 1 to 14—and beyond if you provide services beyond standard office visits. These changes were made with the intent to simplify the process of documentation and allow a provider to spend more time with patients, though there is still a paucity of data related to whether the new system achieves these aims.

The general rule of reporting work with CPT codes can be simply stated—“Document what you did, do what you documented, and report that which is medically necessary” (David McCafferey, MD, personal communication)—and you should never have any difficulty with audits. Unfortunately, the new system does not let an auditor, who typically lacks a medical degree, audit effectively unless they have a clear understanding of diseases and their stages. Many medical societies, including the American Medical Association3 and American Academy of Dermatology,4 have provided education that focuses on how to report a given vignette, but specific examples of documentation with commentary are uncommon.

To make your documentation more likely to pass audits, explicitly link parts of your documentation to CPT MDM descriptors. We offer scenarios and tips. In part 1 of this series, we discuss how to approach the “spot check,” a commonly encountered chief concern (CC) within dermatology.

A 34-year-old presents with a new spot on the left cheek that seems to be growing and changing shape rapidly. You examine the patient and discuss treatment options. The documentation reads as follows:

• CC: New spot on left cheek that seems to be growing and changing shape rapidly

• History: No family history of skin cancer; concerned about scarring, no blood thinner

• Examination: Irregular tan to brown to black 8-mm macule. No lymphadenopathy

• Impression: rule out melanoma.

• Plan:

As was the case before 2021, you still need a CC, along with a medically (and medicolegally) appropriate history and physical examination. A diagnostic impression and treatment plan also should be included.

In this situation, reporting is straightforward. There is no separate E/M visit; only the CPT code 11102 for tangential biopsy is reported. An International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision code of D48.5 (neoplasm of uncertain behavior of skin) will be included.

Why no E/M code? This is because the biopsy includes preservice and postservice time and work that would be double reported with the E/M. Remember that the preservice work would include any history and physical examination related to the area to be biopsied.

Specifically, preservice work includes:

Inspect and palpate lesion to assess surface size, subcutaneous depth and extension, and whether fixed to underlying structures. Select the most representative and appropriate site to obtain specimen. Examine draining lymph node basins. Discuss need for skin biopsy and biopsy technique options. Describe the tangential biopsy procedure method and expected result and the potential for inconclusive pathology result. Review procedural risks, including bleeding, pain, edema, infection, delayed healing, scarring, and hyper- or hypopigmentation.5

Postservice work includes:

Instruct patient and family on postoperative wound care and dressing changes, as well as problems such as bleeding or pain and restrictions on activities, and follow-up care. Provide prescriptions for pain and antibiotics as necessary. Advise patient and family when results will be available and how they will be communicated. The pathology request form is filled out and signed by the physician. Complete medical record and communicate procedure/results to referring physician as appropriate.5

The Takeaway—Procedure codes include preservice and postservice work. If additional work for the procedure is not documented beyond that, an E/M cannot be included in the encounter.

Scenario 2: What If We Don’t Biopsy?

• CC: New spot on left cheek that seems to be growing and changing shape rapidly.

• History: No family history of skin cancer; concerned about scarring, no blood thinner.

• Examination: Irregular tan to brown to black 8-mm macule. No lymphadenopathy.

• Impression: rule out melanoma.

• Plan: Review risk, benefits, and alternative options. Schedule biopsy. Discuss unique risk factor of sebaceous peau d’orange skin more prone to contour defects after biopsy.

When determining the coding level for this scenario by MDM, 3 components must be considered: number and complexity of problems addressed at the encounter (column 1), amount and/or complexity of data to be reviewed and analyzed (column 2), and risk of complications and/or morbidity or mortality of patient management (column 3).1 There are no data that are reviewed, so the auditor will assume minimal data to be reviewed and/or analyzed (level 2, row 2 in the MDM table). However, there may be a lot of variation in how an auditor would address the number and complexity of problems (level 1). Consider that you must explicitly state what you are thinking, as an auditor may not know melanoma is a life-threatening diagnosis. From the perspective of the auditor, could this be a:

• Self-limited or minor problem (level 2, or minimal problem in the MDM table)?1

• Stable chronic illness (level 3, or low-level problem)?1

• Undiagnosed new problem with uncertain prognosis (level 4, or moderate level problem)?1

• Acute illness with systemic symptoms (level 4, or moderate level problem)?1

• Acute or chronic illness or injury that poses a threat to life or bodily function (level 5, or high-level problem)?1

• All of the above?

Similarly, there may be variation in how the risk (column 3) would be interpreted in this scenario. The treatment gives no guidance, so the auditor may assume this has a minimal risk of morbidity (level 2) or possibly a low risk of morbidity from additional diagnostic testing or treatment (level 3), as opposed to a moderate risk of morbidity (level 4).1The Takeaway—In the auditor’s mind, this could be a straightforward (CPT codes 99202/99212) or lowlevel (99203/99213) visit as opposed to a moderate-level (99204/99214) visit. From the above documentation, an auditor would not be able to tell what you are thinking, and you can be assured they will not look further into the diagnosis or treatment to learn. That is not their job. So, let us clarify by explicitly stating what you are thinking in the context of the MDM grid.

Modified Scenario 2: A Funny-Looking New Spot With MDM Descriptors to Guide an Auditor

Below are modifications to the documentation for scenario 2 to guide an auditor:

• CC: New spot on left cheek that seems to be growing and changing shape rapidly.

• History: No family history of skin cancer; concerned about scarring, no blood thinner.

• Examination: Irregular tan to brown to black 8-mm macule. No lymphadenopathy.

• Impression: rule out melanoma

• Plan: Discuss risks, benefits, and alternatives, including biopsy (

In this scenario, the level of MDM is much more clearly documented (as bolded above).

The number and complexity of problems would be an undiagnosed new problem with uncertain prognosis, which would be moderate complexity (column 1, level 4).1 There are no data that are reviewed or analyzed, which would be straightforward (column 2, level 2). For risk, the discussion of the biopsy as part of the diagnostic choices should include discussion of possible scarring, bleeding, pain, and infection, which would be considered best described as a decision regarding minor surgery with identified patient or procedure risk factors, which would make this of moderate complexity (column 3, level 4).1

Importantly, even if the procedure is not chosen as the final treatment plan, the discussion regarding the surgery, including the risks, benefits, and alternatives, can still count toward this category in the MDM table. Therefore, in this scenario with the updated and clarified documentation, this would be reported as CPT code 99204 for a new patient, while an established patient would be 99214.

Scenario 1 Revisited: A Funny-Looking New Spot

Below is scenario 1 with enhanced documentation, now applied to our procedure-only visit.

• CC: New spot on left cheek that seems to be growing and changing shape rapidly.

• History: No family history of skin cancer; concerned about scarring, no blood thinner.

• Examination: Irregular tan to brown to black 8-mm macule. No lymphadenopathy.

• Impression: rule out melanoma (undiagnosed new problem with uncertain prognosis).

• Plan: Discuss risks, benefits, and alternatives, including biopsy (decision regarding minor surgery with identified patient or procedure risk factors) vs a noninvasive 2 gene expression profiling melanoma rule-out test. Patient wants biopsy. Consent, biopsy via shave technique. Lidocaine hydrochloride 1% with epinephrine, 1 cc, prepare and drape, hemostasis obtained, ointment and bandage applied, and care instructions provided.

This documentation would only allow reporting the biopsy as in Scenario 1, as the decision to perform a 0- or 10-day global procedure is bundled with the procedure if performed on the same date of service.

Final Thoughts

Spot checks are commonly encountered dermatologic visits. With the updated E/M guidelines, clarifying and streamlining your documentation is crucial. In particular, utilizing language that clearly defines number and complexity of problems, amount and/or complexity of data to be reviewed and analyzed, and appropriate risk stratification is crucial to ensuring appropriate reimbursement and minimizing your pain with audits.

- American Medical Association. CPT evaluation and management (E/M) code and guideline changes; 2023. Accessed April 13, 2023. https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2023-e-m-descriptors-guidelines.pdf

- American Medical Association. CPT Professional Edition 2023. American Medical Association; 2022.

- American Medical Association. Evaluation and management (E/M) coding. Accessed April 25, 2023. https://www.ama-assn.org/topics/evaluation-and-management-em-coding

- American Academy of Dermatology Association. Coding resource center. Accessed April 13, 2023. https://www.aad.org/member/practice/coding

- American Medical Association. RBVS DataManager Online. Accessed April 13, 2023. https://commerce.ama-assn.org/store/ui/catalog/productDetail?product_id=prod280002&navAction=push

- American Medical Association. CPT evaluation and management (E/M) code and guideline changes; 2023. Accessed April 13, 2023. https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2023-e-m-descriptors-guidelines.pdf

- American Medical Association. CPT Professional Edition 2023. American Medical Association; 2022.

- American Medical Association. Evaluation and management (E/M) coding. Accessed April 25, 2023. https://www.ama-assn.org/topics/evaluation-and-management-em-coding

- American Academy of Dermatology Association. Coding resource center. Accessed April 13, 2023. https://www.aad.org/member/practice/coding

- American Medical Association. RBVS DataManager Online. Accessed April 13, 2023. https://commerce.ama-assn.org/store/ui/catalog/productDetail?product_id=prod280002&navAction=push

Practice Points

- Clear documentation that reflects your thought process is an important component of effective coding and billing.

- Include Current Procedural Terminology–defined language within documentation to help ensure appropriate reimbursement and decrease the risk of audits.

Proper Use and Compliance of Facial Masks During the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Observational Study of Hospitals in New York City

Although the universal use of masks by both health care professionals and the general public now appears routine, widely differing recommendations were distributed by different health organizations early in the pandemic. In April 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) stated that there was no evidence that healthy individuals wearing a medical mask in the community prevented COVID-19 infection.1 However, these recommendations must be placed in the context of a national shortage of personal protective equipment early in the pandemic. The WHO guidance released on June 5, 2020, recommended continuous use of masks for health care workers in the clinical setting.2 Additional recommendations included mask replacement when wet, soiled, or damaged, and when the wearer touched the mask. The WHO also recommended mask usage by those with underlying medical comorbidities and those living in high population–density areas and in settings where physical distancing was not possible.2

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) officially recommended the use of face coverings for the general public to prevent COVID-19 transmission on April 3, 2020.3 The CDC highlighted that masks should not be worn by children younger than 2 years; individuals with respiratory compromise; and patients who are unconscious, incapacitated, or unable to remove a mask without assistance.4 Medical masks and respirators were only recommended for health care workers. Importantly, masks with valves/vents were not recommended, as respiratory droplets can be emitted, defeating the purpose of source control.4 New York State mandated mask usage in public places starting on April 15, 2020.

These recommendations were based on the hypothesis that COVID-19 transmission occurs primarily via droplets and contact. In reality, SARS-CoV-2 transmission more likely occurs in a continuum from larger droplets to miniscule aerosols expelled from an infected person when talking, coughing, or sneezing.5,6 It should be noted that there was a formal suggestion of the potential for airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2 by the CDC in a statement on September 18, 2020, that was subsequently retracted 3 days later.7,8 The CDC, reversing their prior recommendations, updated their guidance on October 5, 2020, endorsing prior reports that SARS-CoV-2 can be spread through aerosol transmission.8

Mask usage helps prevent viral spread by all individuals, especially those who are presymptomatic and asymptomatic. Presymptomatic individuals account for approximately 40% to 60% of transmissions, and asymptomatic individuals account for approximately 4% to 30% of infections by some models, which suggest these individuals are the drivers of the pandemic, more so than symptomatic individuals.9-15 Additionally, masking also may in effect reduce the amount of SARS-CoV-2 to which individuals are being exposed in the community.14 Universal masking is a relatively low-cost, low-risk intervention that may provide moderate benefit to the individual but substantial benefit to communities at large.10-13 Universal masking in other countries also has clearly demonstrated major benefits during the pandemic. Implementation of universal masking in Taiwan resulted in only approximately 440 COVID-19 cases and less than 10 deaths, despite a population of 23 million.16 South Korea, having experience with Middle East respiratory syndrome, also was able to quickly institute a mask policy for its citizens, resulting in approximately 94% compliance.17 Moreover, several mathematical models have shown that even imperfect use of masks on a population level can prevent disease transmission and should be instituted.18

Given the importance and potential benefits of mask usage, we investigated compliance and proper utilization of facial masks in New York City (NYC), once the epicenter of the pandemic in the United States. New York City and the rest of New York State experienced more than 1.13 million and 1.46 million cases of COVID-19, respectively, as of early November 2021.19 Nationwide, NYC had the greatest absolute death count of more than 34,634 and the greatest rate of death per 100,000 individuals of 412. In contrast, New York State, excluding NYC, had an absolute death count of more than 21,646 and a death rate per 100,000 individuals of 195 as of early November 2021.19 Now entering 20 months since the first case of COVID-19 in NYC, it continues to be vital for facial mask protocols to be emphasized as part of a comprehensive infection prevention protocol, especially in light of continued vaccine resistance, to help stall continued spread of SARS-CoV-2.20

We seek to show that despite months of policies for universal masking in NYC, there is still considerable mask noncompliance by the general public in health care settings where the use of masks is particularly imperative. We conducted an observational study investigating proper use of face masks of adults entering the main entrance of 4 hospitals located in NYC.

Methods

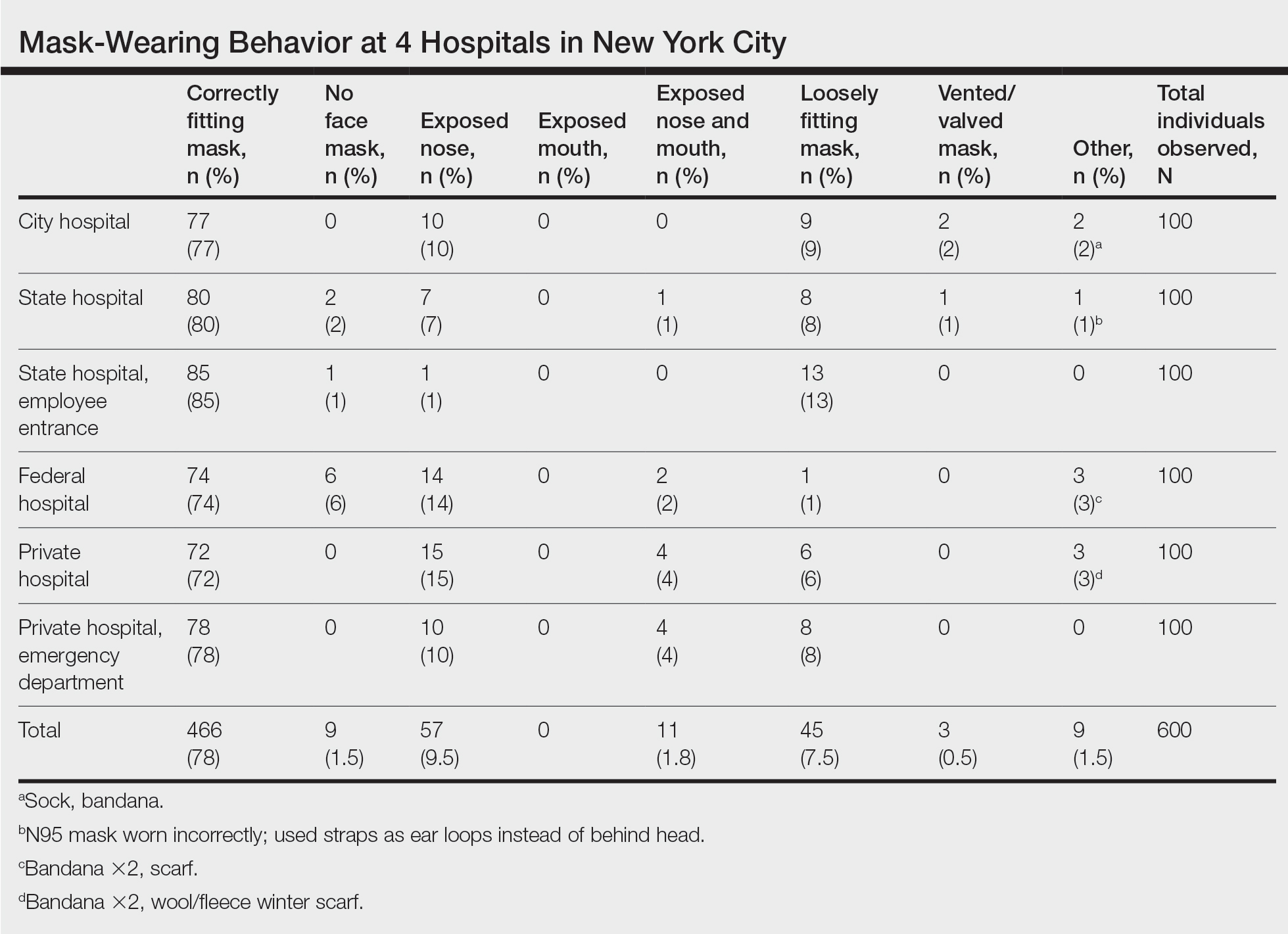

We observed mask usage in adults entering 4 hospitals in September 2020 (postsurge in NYC and prior to the availability of COVID-19 vaccinations). Hospitals were chosen to represent several types of health care delivery systems available in the United States and included a city, state, federal, and private hospital. Data collection was completed during peak traffic hours (8:00

Mask usage was observed and classified into several categories: correctly fitting mask over the nose and mouth, no face mask, mask usage with nose exposed, mask usage with mouth exposed, mask usage with both nose and mouth exposed (ie, mask on the chin/neck area), loosely fitting mask, vented/valved mask, or other form of face covering (eg, bandana, scarf).

Results

We observed a consistent rate of mask compliance between 72% and 85%, with an average of 78% of the 600 individuals observed wearing correctly fitting masks across the 4 hospitals included in this study (Table). The employee entrance included in this study had the highest compliance rate of 85%. An overall low rate of complete mask noncompliance was observed, with only 9 individuals (1.5%) in the entire study not wearing any mask. The federal hospital had the highest rate of mask noncompliance. We also observed a low rate of nose and mouth exposure, with 1.8% of individuals wearing a mask with the nose and mouth exposed (ie, mask tucked under the chin). No individuals were observed with the mouth exposed but with the nose covered by a mask. Additionally, only 3 individuals (0.5%) wore a mask with a vent/valve. The most common way that masks were worn incorrectly was with the nose exposed, accounting for 9.5% of individuals observed. Overall, only 9 individuals (1.5%) wore a nontraditional face covering, with a bandana being the most commonly observed makeshift mask.