User login

ED docs are cleaning up the messes of medical tourism

It was a typical, busy evening shift in the emergency department (ED) when Steve Carroll, DO, an emergency medicine physician in the Philadelphia area, noticed an odd listing on the tracking board. In the waiting room, there was someone whose chief complaint was that she needed to have surgical drains pulled.

According to the woman’s chart, she’d undergone liposuction in Miami a week before. The surgeon had effectively relinquished all follow-up care to the woman’s local ED.

Dr. Carroll searched the name of her surgeon and found that his site “specifically advertised medical tourism,” Dr. Carroll said. The site lured patients with the idea of recovering by the beach and that a local nurse would come to their room every day.

But when Dr. Carroll told the patient that her surgeon should be the one who removes the drains, she became concerned. She didn’t know that her surgeon wasn’t providing the standard of care, he said. Somewhat appalled that a board-certified plastic surgeon would place the burden of follow-up care on an ED doctor hundreds of miles away, Dr. Carroll posted the case to Twitter and several Facebook groups.

“Yes I could refuse to take [the drains] out but that’s not patient-centered care,” Dr. Carroll wrote in a Twitter thread. “It’s unfairly shifting routine outpatient surgical followup (and liability) onto me and extra cost to [the patient].” Comments from ED physicians and sympathetic surgeons across the country flowed in. Dr. Carroll quickly realized his situation was part of a much larger problem than he’d thought.

Dr. Carroll’s patient told him that the Miami surgery cost less than undergoing the surgery locally; that’s why she’d made the trip. She’s not alone. Traveling to get the lowest price for a plastic surgery procedure has been a rising phenomenon since the early 2000s, according to the American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS). Many countries are actively fostering their medical tourism industries, as are states such as Florida.

People have long traveled to get the best medical care. But “medical tourism is completely different,” said Alan Matarasso, MD, FACS, a Manhattan-based plastic surgeon and member of the ASPS Executive Committee. “People [are] traveling to get a simultaneous vacation or lower cost,” he said.

Choosing facilities on the basis of these criteria comes with myriad problems, and the quality of medical care may be lower. It’s difficult to verify the credentials of the surgeons, anesthesiologists, and facilities involved. Medical records can be in a different language, and traveling immediately after surgery increases the risk for pulmonary embolism and death, not to mention the added complications of traveling and being a surgical patient during the COVID-19 pandemic, he said.

Typically, surgeons are protective of their patients. But Murtaza Akhter, MD, an emergency medicine physician based in Miami, says it’s the opposite with the medical tourism surgeons whose patients regularly end up in his ED. “There’s almost no ownership,” he said. “Every time, [the patients] say, ‘My doctor isn’t responding,’ or they said go to the ER.” And that’s before they’ve even made it out of Miami.

The most common cosmetic surgery complications Dr. Akhter sees occur in patients who’ve undergone so-called Brazilian butt lifts. They show up in his ED face down, suffering from severe blood loss. He has them undergo a transfusion and maybe some imaging, but if they need a higher degree of care, they have to be transferred. “There’s a reason it’s cheaper,” he said.

Medical tourism mishaps are such a regular occurrence in Miami that no one flinches when the patients show up in the ED, Dr. Akhter said. He had begun to think he was overreacting to the problem until he saw Dr. Carroll’s Twitter thread.

“Since it’s daily, I just thought maybe I had gone crazy and that it’s considered normal for plastic surgeons to do this. Thanks for making me feel sane again,” Dr. Akhter tweeted in a reply to Dr. Carroll.

There are no reliable data as to of how often or where such surgeries are occurring or of patients’ outcomes. But Nicholas Genes, MD, an ED physician in Manhattan, says he sees far more postsurgical patients who traveled for their procedures than ones who underwent surgery locally. He can’t say for certain whether that’s because procedures performed by doctors in New York City have fewer complications or the physicians just handle postprocedure problems themselves.

In a 2021 systematic review of aesthetic breast surgeries performed through medical tourism, researchers found that of 171 patients who traveled for surgery, 88 (51%) had a total of 106 complications that required returning to the operating room and undergoing general anesthesia. They also found that 39% of breast augmentation implant surgeries required either a unilateral or bilateral explantation procedure after patients returned home.

The rate of complications was higher than the study authors had expected. “These are totally elective procedures,” Dr. Matarasso said. “They should be optimized.” And high rates of complications come with hefty price tags.

The cost of managing these complications, which falls to the home healthcare system or the patient themselves, can range from $5,500 (determined on the basis of data from a 2019 study in the United Kingdom) to as much as $123,000, researchers in New York City calculated, if the patient develops a complicated mycobacterium infection.

“In your effort to get a good deal or around the system, you could still end up with a lot of extensive medical bills if something goes wrong,” Dr. Genes said.

The liability dilemma

Many of the ED physicians Dr. Carroll heard from said that they wouldn’t have treated the woman who needed to have drains removed. Unlike the Brazilian-butt-lifts-gone-wrong in Miami or the complications Dr. Genes sees in New York City, Dr. Carroll’s patient wasn’t in a state of emergency. Most ED physicians said they would have sent her on her way to find a surgeon.

“In general, we shouldn’t be doing things we aren’t trained to do. It’s sort of a slippery slope,” Dr. Genes said. He’s comfortable with removing stitches, but for surgical drains and plastic apparatuses, “I don’t feel particularly well trained. I’d have to consult a colleague in general surgery,” he said. When he does get one of these patients, he works the phones to find a plastic surgeon who will see the patient, something he says their original plastic surgeon should have done.

“Sitting there with the patient, I felt a little bad for her,” Dr. Carroll said. “I knew if I didn’t do it, it would be weeks while she bounced around to urgent care, primary care, and finally found a surgeon.” But by removing the drains, he did shift some of the liability to himself. “If she developed a wound infection, then I’m on the hook for [that],” he said. “If I send her away, I have less liability but didn’t quite do the right thing for the patient.”

In replies to Dr. Carroll’s thread, some doctors debated whether these types of cases, particularly those in which surgeons forgo follow-up care, could be considered medical abandonment. Legal experts say that’s not exactly the case, at least it would not be the case with Dr. Carroll’s patient.

“I don’t think they’ve abandoned the patient; I think they’ve abandoned care,” said Michael Flynn, JD, professor of personal injury law at Nova Southeastern University, in Fort Lauderdale–Davie, Fla. “And that abandonment of follow-up care, if it falls below the standard of what medical professionals should do, then it’s malpractice.”

“The doctor didn’t just walk away and become unreachable,” said Bernard Black, JD, a medical malpractice attorney and law professor at Northwestern University, in Evanston, Ill. Technically, the surgeon referred the patient to the ED. Mr. Black agreed that it sounds more like a question of malpractice, “but without real damages, there’s no claim.”

Even if not illegal, sending these patients to the ED is still highly unethical, Dr. Carroll said. The authors of a 2014 article in Aesthetic Plastic Surgery concur: “It is the duty and ethical responsibility of plastic surgeons to prevent unnecessary complications following tourism medicine by adequately counseling patients, defining perioperative treatment protocols, and reporting complications to regional and specialty-specific governing bodies,” they write.

Sometimes patients need to travel, Dr. Matarasso said. Recently, three out-of-state patients came to him for procedures. Two stayed in Manhattan until their follow-up care was finished; he arranged care elsewhere for the third. It’s the operating surgeon’s job to connect patients with someone who can provide follow-up care when they go home, Dr. Matarasso said. If a surgeon doesn’t have a connection in a patient’s home city, the ASPS has a referral service to help, he said.

“My frustration was never with the patient,” Dr. Carroll said. “No one should feel bad about coming to an ED for literally anything, and I mean that. My frustration is with the surgeon who didn’t go the one extra step to arrange her follow-up.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It was a typical, busy evening shift in the emergency department (ED) when Steve Carroll, DO, an emergency medicine physician in the Philadelphia area, noticed an odd listing on the tracking board. In the waiting room, there was someone whose chief complaint was that she needed to have surgical drains pulled.

According to the woman’s chart, she’d undergone liposuction in Miami a week before. The surgeon had effectively relinquished all follow-up care to the woman’s local ED.

Dr. Carroll searched the name of her surgeon and found that his site “specifically advertised medical tourism,” Dr. Carroll said. The site lured patients with the idea of recovering by the beach and that a local nurse would come to their room every day.

But when Dr. Carroll told the patient that her surgeon should be the one who removes the drains, she became concerned. She didn’t know that her surgeon wasn’t providing the standard of care, he said. Somewhat appalled that a board-certified plastic surgeon would place the burden of follow-up care on an ED doctor hundreds of miles away, Dr. Carroll posted the case to Twitter and several Facebook groups.

“Yes I could refuse to take [the drains] out but that’s not patient-centered care,” Dr. Carroll wrote in a Twitter thread. “It’s unfairly shifting routine outpatient surgical followup (and liability) onto me and extra cost to [the patient].” Comments from ED physicians and sympathetic surgeons across the country flowed in. Dr. Carroll quickly realized his situation was part of a much larger problem than he’d thought.

Dr. Carroll’s patient told him that the Miami surgery cost less than undergoing the surgery locally; that’s why she’d made the trip. She’s not alone. Traveling to get the lowest price for a plastic surgery procedure has been a rising phenomenon since the early 2000s, according to the American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS). Many countries are actively fostering their medical tourism industries, as are states such as Florida.

People have long traveled to get the best medical care. But “medical tourism is completely different,” said Alan Matarasso, MD, FACS, a Manhattan-based plastic surgeon and member of the ASPS Executive Committee. “People [are] traveling to get a simultaneous vacation or lower cost,” he said.

Choosing facilities on the basis of these criteria comes with myriad problems, and the quality of medical care may be lower. It’s difficult to verify the credentials of the surgeons, anesthesiologists, and facilities involved. Medical records can be in a different language, and traveling immediately after surgery increases the risk for pulmonary embolism and death, not to mention the added complications of traveling and being a surgical patient during the COVID-19 pandemic, he said.

Typically, surgeons are protective of their patients. But Murtaza Akhter, MD, an emergency medicine physician based in Miami, says it’s the opposite with the medical tourism surgeons whose patients regularly end up in his ED. “There’s almost no ownership,” he said. “Every time, [the patients] say, ‘My doctor isn’t responding,’ or they said go to the ER.” And that’s before they’ve even made it out of Miami.

The most common cosmetic surgery complications Dr. Akhter sees occur in patients who’ve undergone so-called Brazilian butt lifts. They show up in his ED face down, suffering from severe blood loss. He has them undergo a transfusion and maybe some imaging, but if they need a higher degree of care, they have to be transferred. “There’s a reason it’s cheaper,” he said.

Medical tourism mishaps are such a regular occurrence in Miami that no one flinches when the patients show up in the ED, Dr. Akhter said. He had begun to think he was overreacting to the problem until he saw Dr. Carroll’s Twitter thread.

“Since it’s daily, I just thought maybe I had gone crazy and that it’s considered normal for plastic surgeons to do this. Thanks for making me feel sane again,” Dr. Akhter tweeted in a reply to Dr. Carroll.

There are no reliable data as to of how often or where such surgeries are occurring or of patients’ outcomes. But Nicholas Genes, MD, an ED physician in Manhattan, says he sees far more postsurgical patients who traveled for their procedures than ones who underwent surgery locally. He can’t say for certain whether that’s because procedures performed by doctors in New York City have fewer complications or the physicians just handle postprocedure problems themselves.

In a 2021 systematic review of aesthetic breast surgeries performed through medical tourism, researchers found that of 171 patients who traveled for surgery, 88 (51%) had a total of 106 complications that required returning to the operating room and undergoing general anesthesia. They also found that 39% of breast augmentation implant surgeries required either a unilateral or bilateral explantation procedure after patients returned home.

The rate of complications was higher than the study authors had expected. “These are totally elective procedures,” Dr. Matarasso said. “They should be optimized.” And high rates of complications come with hefty price tags.

The cost of managing these complications, which falls to the home healthcare system or the patient themselves, can range from $5,500 (determined on the basis of data from a 2019 study in the United Kingdom) to as much as $123,000, researchers in New York City calculated, if the patient develops a complicated mycobacterium infection.

“In your effort to get a good deal or around the system, you could still end up with a lot of extensive medical bills if something goes wrong,” Dr. Genes said.

The liability dilemma

Many of the ED physicians Dr. Carroll heard from said that they wouldn’t have treated the woman who needed to have drains removed. Unlike the Brazilian-butt-lifts-gone-wrong in Miami or the complications Dr. Genes sees in New York City, Dr. Carroll’s patient wasn’t in a state of emergency. Most ED physicians said they would have sent her on her way to find a surgeon.

“In general, we shouldn’t be doing things we aren’t trained to do. It’s sort of a slippery slope,” Dr. Genes said. He’s comfortable with removing stitches, but for surgical drains and plastic apparatuses, “I don’t feel particularly well trained. I’d have to consult a colleague in general surgery,” he said. When he does get one of these patients, he works the phones to find a plastic surgeon who will see the patient, something he says their original plastic surgeon should have done.

“Sitting there with the patient, I felt a little bad for her,” Dr. Carroll said. “I knew if I didn’t do it, it would be weeks while she bounced around to urgent care, primary care, and finally found a surgeon.” But by removing the drains, he did shift some of the liability to himself. “If she developed a wound infection, then I’m on the hook for [that],” he said. “If I send her away, I have less liability but didn’t quite do the right thing for the patient.”

In replies to Dr. Carroll’s thread, some doctors debated whether these types of cases, particularly those in which surgeons forgo follow-up care, could be considered medical abandonment. Legal experts say that’s not exactly the case, at least it would not be the case with Dr. Carroll’s patient.

“I don’t think they’ve abandoned the patient; I think they’ve abandoned care,” said Michael Flynn, JD, professor of personal injury law at Nova Southeastern University, in Fort Lauderdale–Davie, Fla. “And that abandonment of follow-up care, if it falls below the standard of what medical professionals should do, then it’s malpractice.”

“The doctor didn’t just walk away and become unreachable,” said Bernard Black, JD, a medical malpractice attorney and law professor at Northwestern University, in Evanston, Ill. Technically, the surgeon referred the patient to the ED. Mr. Black agreed that it sounds more like a question of malpractice, “but without real damages, there’s no claim.”

Even if not illegal, sending these patients to the ED is still highly unethical, Dr. Carroll said. The authors of a 2014 article in Aesthetic Plastic Surgery concur: “It is the duty and ethical responsibility of plastic surgeons to prevent unnecessary complications following tourism medicine by adequately counseling patients, defining perioperative treatment protocols, and reporting complications to regional and specialty-specific governing bodies,” they write.

Sometimes patients need to travel, Dr. Matarasso said. Recently, three out-of-state patients came to him for procedures. Two stayed in Manhattan until their follow-up care was finished; he arranged care elsewhere for the third. It’s the operating surgeon’s job to connect patients with someone who can provide follow-up care when they go home, Dr. Matarasso said. If a surgeon doesn’t have a connection in a patient’s home city, the ASPS has a referral service to help, he said.

“My frustration was never with the patient,” Dr. Carroll said. “No one should feel bad about coming to an ED for literally anything, and I mean that. My frustration is with the surgeon who didn’t go the one extra step to arrange her follow-up.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It was a typical, busy evening shift in the emergency department (ED) when Steve Carroll, DO, an emergency medicine physician in the Philadelphia area, noticed an odd listing on the tracking board. In the waiting room, there was someone whose chief complaint was that she needed to have surgical drains pulled.

According to the woman’s chart, she’d undergone liposuction in Miami a week before. The surgeon had effectively relinquished all follow-up care to the woman’s local ED.

Dr. Carroll searched the name of her surgeon and found that his site “specifically advertised medical tourism,” Dr. Carroll said. The site lured patients with the idea of recovering by the beach and that a local nurse would come to their room every day.

But when Dr. Carroll told the patient that her surgeon should be the one who removes the drains, she became concerned. She didn’t know that her surgeon wasn’t providing the standard of care, he said. Somewhat appalled that a board-certified plastic surgeon would place the burden of follow-up care on an ED doctor hundreds of miles away, Dr. Carroll posted the case to Twitter and several Facebook groups.

“Yes I could refuse to take [the drains] out but that’s not patient-centered care,” Dr. Carroll wrote in a Twitter thread. “It’s unfairly shifting routine outpatient surgical followup (and liability) onto me and extra cost to [the patient].” Comments from ED physicians and sympathetic surgeons across the country flowed in. Dr. Carroll quickly realized his situation was part of a much larger problem than he’d thought.

Dr. Carroll’s patient told him that the Miami surgery cost less than undergoing the surgery locally; that’s why she’d made the trip. She’s not alone. Traveling to get the lowest price for a plastic surgery procedure has been a rising phenomenon since the early 2000s, according to the American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS). Many countries are actively fostering their medical tourism industries, as are states such as Florida.

People have long traveled to get the best medical care. But “medical tourism is completely different,” said Alan Matarasso, MD, FACS, a Manhattan-based plastic surgeon and member of the ASPS Executive Committee. “People [are] traveling to get a simultaneous vacation or lower cost,” he said.

Choosing facilities on the basis of these criteria comes with myriad problems, and the quality of medical care may be lower. It’s difficult to verify the credentials of the surgeons, anesthesiologists, and facilities involved. Medical records can be in a different language, and traveling immediately after surgery increases the risk for pulmonary embolism and death, not to mention the added complications of traveling and being a surgical patient during the COVID-19 pandemic, he said.

Typically, surgeons are protective of their patients. But Murtaza Akhter, MD, an emergency medicine physician based in Miami, says it’s the opposite with the medical tourism surgeons whose patients regularly end up in his ED. “There’s almost no ownership,” he said. “Every time, [the patients] say, ‘My doctor isn’t responding,’ or they said go to the ER.” And that’s before they’ve even made it out of Miami.

The most common cosmetic surgery complications Dr. Akhter sees occur in patients who’ve undergone so-called Brazilian butt lifts. They show up in his ED face down, suffering from severe blood loss. He has them undergo a transfusion and maybe some imaging, but if they need a higher degree of care, they have to be transferred. “There’s a reason it’s cheaper,” he said.

Medical tourism mishaps are such a regular occurrence in Miami that no one flinches when the patients show up in the ED, Dr. Akhter said. He had begun to think he was overreacting to the problem until he saw Dr. Carroll’s Twitter thread.

“Since it’s daily, I just thought maybe I had gone crazy and that it’s considered normal for plastic surgeons to do this. Thanks for making me feel sane again,” Dr. Akhter tweeted in a reply to Dr. Carroll.

There are no reliable data as to of how often or where such surgeries are occurring or of patients’ outcomes. But Nicholas Genes, MD, an ED physician in Manhattan, says he sees far more postsurgical patients who traveled for their procedures than ones who underwent surgery locally. He can’t say for certain whether that’s because procedures performed by doctors in New York City have fewer complications or the physicians just handle postprocedure problems themselves.

In a 2021 systematic review of aesthetic breast surgeries performed through medical tourism, researchers found that of 171 patients who traveled for surgery, 88 (51%) had a total of 106 complications that required returning to the operating room and undergoing general anesthesia. They also found that 39% of breast augmentation implant surgeries required either a unilateral or bilateral explantation procedure after patients returned home.

The rate of complications was higher than the study authors had expected. “These are totally elective procedures,” Dr. Matarasso said. “They should be optimized.” And high rates of complications come with hefty price tags.

The cost of managing these complications, which falls to the home healthcare system or the patient themselves, can range from $5,500 (determined on the basis of data from a 2019 study in the United Kingdom) to as much as $123,000, researchers in New York City calculated, if the patient develops a complicated mycobacterium infection.

“In your effort to get a good deal or around the system, you could still end up with a lot of extensive medical bills if something goes wrong,” Dr. Genes said.

The liability dilemma

Many of the ED physicians Dr. Carroll heard from said that they wouldn’t have treated the woman who needed to have drains removed. Unlike the Brazilian-butt-lifts-gone-wrong in Miami or the complications Dr. Genes sees in New York City, Dr. Carroll’s patient wasn’t in a state of emergency. Most ED physicians said they would have sent her on her way to find a surgeon.

“In general, we shouldn’t be doing things we aren’t trained to do. It’s sort of a slippery slope,” Dr. Genes said. He’s comfortable with removing stitches, but for surgical drains and plastic apparatuses, “I don’t feel particularly well trained. I’d have to consult a colleague in general surgery,” he said. When he does get one of these patients, he works the phones to find a plastic surgeon who will see the patient, something he says their original plastic surgeon should have done.

“Sitting there with the patient, I felt a little bad for her,” Dr. Carroll said. “I knew if I didn’t do it, it would be weeks while she bounced around to urgent care, primary care, and finally found a surgeon.” But by removing the drains, he did shift some of the liability to himself. “If she developed a wound infection, then I’m on the hook for [that],” he said. “If I send her away, I have less liability but didn’t quite do the right thing for the patient.”

In replies to Dr. Carroll’s thread, some doctors debated whether these types of cases, particularly those in which surgeons forgo follow-up care, could be considered medical abandonment. Legal experts say that’s not exactly the case, at least it would not be the case with Dr. Carroll’s patient.

“I don’t think they’ve abandoned the patient; I think they’ve abandoned care,” said Michael Flynn, JD, professor of personal injury law at Nova Southeastern University, in Fort Lauderdale–Davie, Fla. “And that abandonment of follow-up care, if it falls below the standard of what medical professionals should do, then it’s malpractice.”

“The doctor didn’t just walk away and become unreachable,” said Bernard Black, JD, a medical malpractice attorney and law professor at Northwestern University, in Evanston, Ill. Technically, the surgeon referred the patient to the ED. Mr. Black agreed that it sounds more like a question of malpractice, “but without real damages, there’s no claim.”

Even if not illegal, sending these patients to the ED is still highly unethical, Dr. Carroll said. The authors of a 2014 article in Aesthetic Plastic Surgery concur: “It is the duty and ethical responsibility of plastic surgeons to prevent unnecessary complications following tourism medicine by adequately counseling patients, defining perioperative treatment protocols, and reporting complications to regional and specialty-specific governing bodies,” they write.

Sometimes patients need to travel, Dr. Matarasso said. Recently, three out-of-state patients came to him for procedures. Two stayed in Manhattan until their follow-up care was finished; he arranged care elsewhere for the third. It’s the operating surgeon’s job to connect patients with someone who can provide follow-up care when they go home, Dr. Matarasso said. If a surgeon doesn’t have a connection in a patient’s home city, the ASPS has a referral service to help, he said.

“My frustration was never with the patient,” Dr. Carroll said. “No one should feel bad about coming to an ED for literally anything, and I mean that. My frustration is with the surgeon who didn’t go the one extra step to arrange her follow-up.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Injectable monoclonal antibodies prevent COVID-19 in trial

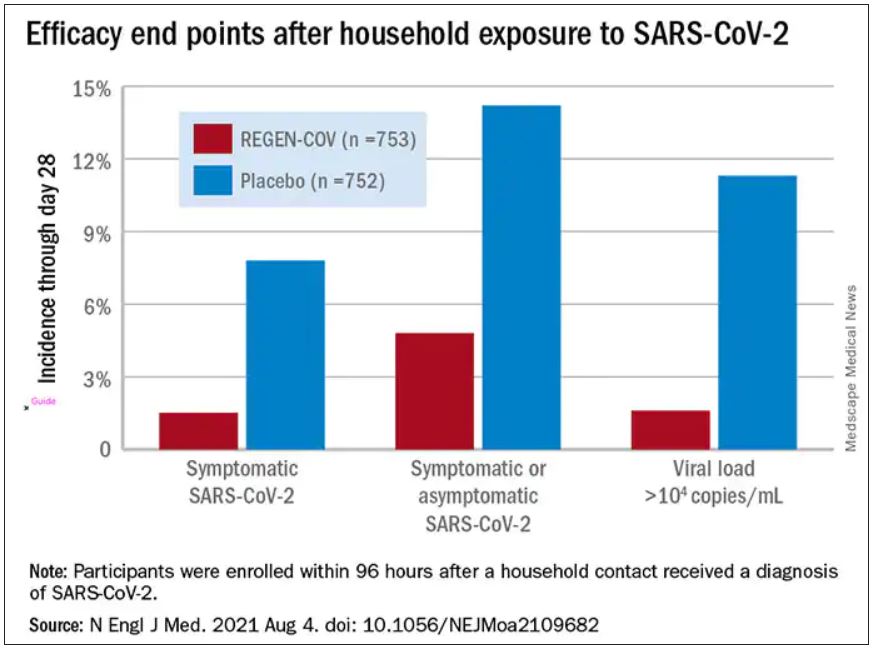

according to results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial published online August 4, 2021, in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The cocktail of the monoclonal antibodies casirivimab and imdevimab (REGEN-COV, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals) reduced participants’ relative risk of infection by 72%, compared with placebo within the first week. After the first week, risk reduction increased to 93%.

“Long after you would be exposed by your household, there is an enduring effect that prevents you from community spread,” said David Wohl, MD, professor of medicine in the division of infectious diseases at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, who was a site investigator for the trial but not a study author.

Participants were enrolled within 96 hours after someone in their household tested positive for SARS-CoV-2. Participants were randomly assigned to receive 1,200 mg of REGEN-COV subcutaneously or a placebo. Based on serologic testing, study participants showed no evidence of current or previous SARS-CoV-2 infection. The median age of participants was 42.9, but 45% were male teenagers (ages 12-17).

In the group that received REGEN-COV, 11 out of 753 participants developed symptomatic COVID-19, compared with 59 out of 752 participants who received placebo. The relative risk reduction for the study’s 4-week period was 81.4% (P < .001). Of the participants that did develop a SARS-CoV-2 infection, those that received REGEN-COV were less likely to be symptomatic. Asymptomatic infections developed in 25 participants who received REGEN-COV versus 48 in the placebo group. The relative risk of developing any SARS-CoV-2 infection, symptomatic or asymptomatic, was reduced by 66.4% with REGEN-COV (P < .001).

Among the patients who were symptomatic, symptoms subsided within a median of 1.2 weeks for the group that received REGEN-COV, 2 weeks earlier than the placebo group. These patients also had a shorter duration of a high viral load (>104 copies/mL). Few adverse events were reported in the treatment or placebo groups. Monoclonal antibodies “seem to be incredibly safe,” Dr. Wohl said.

“These monoclonal antibodies have proven they can reduce the viral replication in the nose,” said study author Myron Cohen, MD, an infectious disease specialist and professor of epidemiology at the University of North Carolina.

The Food and Drug Administration first granted REGEN-COV emergency use authorization (EUA) in November 2020 for use in patients with mild or moderate COVID-19 who were also at high risk for progressing to severe COVID-19. At that time, the cocktail of monoclonal antibodies was delivered by a single intravenous infusion.

In January, Regeneron first announced the success of this trial of the subcutaneous injection for exposed household contacts based on early results, and in June of 2021, the FDA expanded the EUA to include a subcutaneous delivery when IV is not feasible. On July 30, the EUA was expanded again to include prophylactic use in exposed patients based on these trial results.

The U.S. government has purchased approximately 1.5 million doses of REGEN-COV from Regeneron and has agreed to make the treatments free of charge to patients.

But despite being free, available, and backed by promising data, monoclonal antibodies as a therapeutic answer to COVID-19 still hasn’t really taken off. “The problem is, it first requires knowledge and awareness,” Dr. Wohl said. “A lot [of people] don’t know this exists. To be honest, vaccination has taken up all the oxygen in the room.”

Dr. Cohen agreed. One reason for the slow uptake may be because the drug supply is owned by the government and not a pharmaceutical company. There hasn’t been a typical marketing push to make physicians and consumers aware. Additionally, “the logistics are daunting,” Dr. Cohen said. The office spaces where many physicians care for patients “often aren’t appropriate for patients who think they have SARS-CoV-2.”

“Right now, there’s not a mechanism” to administer the drug to people who could benefit from it, Dr. Wohl said. Eligible patients are either immunocompromised and unlikely to mount a sufficient immune response with vaccination, or not fully vaccinated. They should have been exposed to an infected individual or have a high likelihood of exposure due to where they live, such as in a prison or nursing home. Local doctors are unlikely to be the primary administrators of the drug, Dr. Wohl added. “How do we operationalize this for people who fit the criteria?”

There’s also an issue of timing. REGEN-COV is most effective when given early, Dr. Cohen said. “[Monoclonal antibodies] really only work well in the replication phase.” Many patients who would be eligible delay care until they’ve had symptoms for several days, when REGEN-COV would no longer have the desired effect.

Eventually, Dr. Wohl suspects demand will increase when people realize REGEN-COV can help those with COVID-19 and those who have been exposed. But before then, “we do have to think about how to integrate this into a workflow people can access without being confused.”

The trial was done before there was widespread vaccination, so it’s unclear what the results mean for people who have been vaccinated. Dr. Cohen and Dr. Wohl said there are ongoing conversations about whether monoclonal antibodies could be complementary to vaccination and if there’s potential for continued monthly use of these therapies.

Cohen and Wohl reported no relevant financial relationships. The trial was supported by Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, F. Hoffmann–La Roche, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH, and the COVID-19 Prevention Network.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

according to results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial published online August 4, 2021, in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The cocktail of the monoclonal antibodies casirivimab and imdevimab (REGEN-COV, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals) reduced participants’ relative risk of infection by 72%, compared with placebo within the first week. After the first week, risk reduction increased to 93%.

“Long after you would be exposed by your household, there is an enduring effect that prevents you from community spread,” said David Wohl, MD, professor of medicine in the division of infectious diseases at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, who was a site investigator for the trial but not a study author.

Participants were enrolled within 96 hours after someone in their household tested positive for SARS-CoV-2. Participants were randomly assigned to receive 1,200 mg of REGEN-COV subcutaneously or a placebo. Based on serologic testing, study participants showed no evidence of current or previous SARS-CoV-2 infection. The median age of participants was 42.9, but 45% were male teenagers (ages 12-17).

In the group that received REGEN-COV, 11 out of 753 participants developed symptomatic COVID-19, compared with 59 out of 752 participants who received placebo. The relative risk reduction for the study’s 4-week period was 81.4% (P < .001). Of the participants that did develop a SARS-CoV-2 infection, those that received REGEN-COV were less likely to be symptomatic. Asymptomatic infections developed in 25 participants who received REGEN-COV versus 48 in the placebo group. The relative risk of developing any SARS-CoV-2 infection, symptomatic or asymptomatic, was reduced by 66.4% with REGEN-COV (P < .001).

Among the patients who were symptomatic, symptoms subsided within a median of 1.2 weeks for the group that received REGEN-COV, 2 weeks earlier than the placebo group. These patients also had a shorter duration of a high viral load (>104 copies/mL). Few adverse events were reported in the treatment or placebo groups. Monoclonal antibodies “seem to be incredibly safe,” Dr. Wohl said.

“These monoclonal antibodies have proven they can reduce the viral replication in the nose,” said study author Myron Cohen, MD, an infectious disease specialist and professor of epidemiology at the University of North Carolina.

The Food and Drug Administration first granted REGEN-COV emergency use authorization (EUA) in November 2020 for use in patients with mild or moderate COVID-19 who were also at high risk for progressing to severe COVID-19. At that time, the cocktail of monoclonal antibodies was delivered by a single intravenous infusion.

In January, Regeneron first announced the success of this trial of the subcutaneous injection for exposed household contacts based on early results, and in June of 2021, the FDA expanded the EUA to include a subcutaneous delivery when IV is not feasible. On July 30, the EUA was expanded again to include prophylactic use in exposed patients based on these trial results.

The U.S. government has purchased approximately 1.5 million doses of REGEN-COV from Regeneron and has agreed to make the treatments free of charge to patients.

But despite being free, available, and backed by promising data, monoclonal antibodies as a therapeutic answer to COVID-19 still hasn’t really taken off. “The problem is, it first requires knowledge and awareness,” Dr. Wohl said. “A lot [of people] don’t know this exists. To be honest, vaccination has taken up all the oxygen in the room.”

Dr. Cohen agreed. One reason for the slow uptake may be because the drug supply is owned by the government and not a pharmaceutical company. There hasn’t been a typical marketing push to make physicians and consumers aware. Additionally, “the logistics are daunting,” Dr. Cohen said. The office spaces where many physicians care for patients “often aren’t appropriate for patients who think they have SARS-CoV-2.”

“Right now, there’s not a mechanism” to administer the drug to people who could benefit from it, Dr. Wohl said. Eligible patients are either immunocompromised and unlikely to mount a sufficient immune response with vaccination, or not fully vaccinated. They should have been exposed to an infected individual or have a high likelihood of exposure due to where they live, such as in a prison or nursing home. Local doctors are unlikely to be the primary administrators of the drug, Dr. Wohl added. “How do we operationalize this for people who fit the criteria?”

There’s also an issue of timing. REGEN-COV is most effective when given early, Dr. Cohen said. “[Monoclonal antibodies] really only work well in the replication phase.” Many patients who would be eligible delay care until they’ve had symptoms for several days, when REGEN-COV would no longer have the desired effect.

Eventually, Dr. Wohl suspects demand will increase when people realize REGEN-COV can help those with COVID-19 and those who have been exposed. But before then, “we do have to think about how to integrate this into a workflow people can access without being confused.”

The trial was done before there was widespread vaccination, so it’s unclear what the results mean for people who have been vaccinated. Dr. Cohen and Dr. Wohl said there are ongoing conversations about whether monoclonal antibodies could be complementary to vaccination and if there’s potential for continued monthly use of these therapies.

Cohen and Wohl reported no relevant financial relationships. The trial was supported by Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, F. Hoffmann–La Roche, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH, and the COVID-19 Prevention Network.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

according to results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial published online August 4, 2021, in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The cocktail of the monoclonal antibodies casirivimab and imdevimab (REGEN-COV, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals) reduced participants’ relative risk of infection by 72%, compared with placebo within the first week. After the first week, risk reduction increased to 93%.

“Long after you would be exposed by your household, there is an enduring effect that prevents you from community spread,” said David Wohl, MD, professor of medicine in the division of infectious diseases at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, who was a site investigator for the trial but not a study author.

Participants were enrolled within 96 hours after someone in their household tested positive for SARS-CoV-2. Participants were randomly assigned to receive 1,200 mg of REGEN-COV subcutaneously or a placebo. Based on serologic testing, study participants showed no evidence of current or previous SARS-CoV-2 infection. The median age of participants was 42.9, but 45% were male teenagers (ages 12-17).

In the group that received REGEN-COV, 11 out of 753 participants developed symptomatic COVID-19, compared with 59 out of 752 participants who received placebo. The relative risk reduction for the study’s 4-week period was 81.4% (P < .001). Of the participants that did develop a SARS-CoV-2 infection, those that received REGEN-COV were less likely to be symptomatic. Asymptomatic infections developed in 25 participants who received REGEN-COV versus 48 in the placebo group. The relative risk of developing any SARS-CoV-2 infection, symptomatic or asymptomatic, was reduced by 66.4% with REGEN-COV (P < .001).

Among the patients who were symptomatic, symptoms subsided within a median of 1.2 weeks for the group that received REGEN-COV, 2 weeks earlier than the placebo group. These patients also had a shorter duration of a high viral load (>104 copies/mL). Few adverse events were reported in the treatment or placebo groups. Monoclonal antibodies “seem to be incredibly safe,” Dr. Wohl said.

“These monoclonal antibodies have proven they can reduce the viral replication in the nose,” said study author Myron Cohen, MD, an infectious disease specialist and professor of epidemiology at the University of North Carolina.

The Food and Drug Administration first granted REGEN-COV emergency use authorization (EUA) in November 2020 for use in patients with mild or moderate COVID-19 who were also at high risk for progressing to severe COVID-19. At that time, the cocktail of monoclonal antibodies was delivered by a single intravenous infusion.

In January, Regeneron first announced the success of this trial of the subcutaneous injection for exposed household contacts based on early results, and in June of 2021, the FDA expanded the EUA to include a subcutaneous delivery when IV is not feasible. On July 30, the EUA was expanded again to include prophylactic use in exposed patients based on these trial results.

The U.S. government has purchased approximately 1.5 million doses of REGEN-COV from Regeneron and has agreed to make the treatments free of charge to patients.

But despite being free, available, and backed by promising data, monoclonal antibodies as a therapeutic answer to COVID-19 still hasn’t really taken off. “The problem is, it first requires knowledge and awareness,” Dr. Wohl said. “A lot [of people] don’t know this exists. To be honest, vaccination has taken up all the oxygen in the room.”

Dr. Cohen agreed. One reason for the slow uptake may be because the drug supply is owned by the government and not a pharmaceutical company. There hasn’t been a typical marketing push to make physicians and consumers aware. Additionally, “the logistics are daunting,” Dr. Cohen said. The office spaces where many physicians care for patients “often aren’t appropriate for patients who think they have SARS-CoV-2.”

“Right now, there’s not a mechanism” to administer the drug to people who could benefit from it, Dr. Wohl said. Eligible patients are either immunocompromised and unlikely to mount a sufficient immune response with vaccination, or not fully vaccinated. They should have been exposed to an infected individual or have a high likelihood of exposure due to where they live, such as in a prison or nursing home. Local doctors are unlikely to be the primary administrators of the drug, Dr. Wohl added. “How do we operationalize this for people who fit the criteria?”

There’s also an issue of timing. REGEN-COV is most effective when given early, Dr. Cohen said. “[Monoclonal antibodies] really only work well in the replication phase.” Many patients who would be eligible delay care until they’ve had symptoms for several days, when REGEN-COV would no longer have the desired effect.

Eventually, Dr. Wohl suspects demand will increase when people realize REGEN-COV can help those with COVID-19 and those who have been exposed. But before then, “we do have to think about how to integrate this into a workflow people can access without being confused.”

The trial was done before there was widespread vaccination, so it’s unclear what the results mean for people who have been vaccinated. Dr. Cohen and Dr. Wohl said there are ongoing conversations about whether monoclonal antibodies could be complementary to vaccination and if there’s potential for continued monthly use of these therapies.

Cohen and Wohl reported no relevant financial relationships. The trial was supported by Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, F. Hoffmann–La Roche, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH, and the COVID-19 Prevention Network.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Midodrine reduces fainting in young patients

.

Vasovagal syncope is the most common cause of fainting and is often triggered by dehydration and upright posture, according to Johns Hopkins Medicine. But it can also be caused by stimuli like the sight of blood or sudden emotional distress. The stimulus causes the heart rate and blood pressure to drop rapidly, according to the Mayo Clinic.

The randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial included 133 patients with recurrent vasovagal syncope and was published in Annals of Internal Medicine. Those that received midodrine were less likely to have one syncope episode (28 of 66 [42%]), compared with those that took the placebo (41 of 67 [61%]). The absolute risk reduction for vasovagal syncope was 19 percentage points (95% confidence interval, 2-36 percentage points).

The study included patients from 25 university hospitals in Canada, the United States, Mexico, and the United Kingdom, who were followed for 12 months. The trial participants were highly symptomatic for vasovagal syncope, having experienced a median of 23 episodes in their lifetime and 5 syncope episodes in the last year, and they had no comorbid conditions.

“We don’t have many arrows in our quiver,” said Robert Sheldon, MD, PhD, a cardiologist at University of Calgary (Alta.) and lead author of the study, referring to the lack of evidence-based treatments for syncope.

For 20 years Dr. Sheldon’s lab has been testing drugs that showed some potential. While a previous study of fludrocortisone (Florinef ) showed some benefit, “[midodrine] was the first to be unequivocally, slam-dunk positive,” he said in an interview.

Earlier trials of midodrine

Other studies have shown midodrine to prevent syncope on tilt tests. There have been two randomized trials where midodrine significantly reduced vasovagal syncope, but one of these was short and in children, and the other one was open label with no placebo control.

“Risk reduction was very high in previous studies,” Dr. Sheldon said in an interview. But, because they were open label, there was a huge placebo effect, he noted.

“There were no adequately done, adequately powered [studies] that have been positive,” Dr. Sheldon added.

New study methods and outcomes

The study published in Annals of Internal Medicine this week included patients over 18 years of age with a Calgary Syncope Symptom Score of at least 2. All were educated on lifestyle measures that can prevent syncopes before beginning to take 5 mg of study drug or placebo three times daily, 4 hours apart.

In these cases, the study authors wrote, “taking medication three times a day seems worth the effort.” But in patients with a lower frequency of episodes, midodrine might not have an adequate payoff.

These results are “impressive,” said Roopinder K. Sandhu, MD, MPH, clinical electrophysiologist at Cedar-Sinai in Los Angeles. “This study demonstrated that midodrine is the first medical therapy, in addition to education and lifestyle measures, to unequivocally pass the scrutiny of an international, placebo-controlled, RCT to show a significant reduction in syncope recurrence in a younger population with frequent syncope events.”

“[Taking midodrine] doesn’t carry the long-term consequence of pacemakers,” she added.

Study limitations

Limitations of the new study include its small size and short observation period, the authors wrote. Additionally, a large proportion of patients enrolled were also from a single center in Calgary that specializes in syncope care. Twenty-seven patients in the trial stopped taking their assigned medication during the year observation period, but the authors concluded these participants “likely would bias the results against midodrine.”

For doctors considering midodrine for their patients, it’s critical to confirm the diagnosis and to try patient education first, Dr. Sheldon advised.

Lifestyle factors like hydration, adequate sodium intake, and squatting or lying down when the syncope is coming on can sufficiently suppress syncopes in two-thirds of patients, he noted.

This is a treatment for young people, Dr. Sandhu said. The median age in the trial was 35, so patients taking midodrine should be younger than 50. Midodrine is also not effective in patients with high blood pressure or heart failure, she said.

“[Midodrine] is easy to use but kind of a pain at first,” Dr. Sheldon noted. Every patient should start out taking 5 mg doses, three times a day – during waking hours. But then you have to adjust the dosage, “and it’s tricky,” he said.

If a patient experiences goosebumps or the sensation of worms crawling in the hair, the dose might be too much, Dr. Sheldon noted.

If the patient is still fainting, first consider when they are fainting, he said. If it’s around the time they should take another dose, it might be trough effect.

Dr. Sandhu was not involved in the study, but Cedar Sinai was a participating center, and she considers Dr. Sheldon to be a mentor. Dr. Sandhu also noted that she has published papers with Dr. Sheldon, who reported no conflicts.

.

Vasovagal syncope is the most common cause of fainting and is often triggered by dehydration and upright posture, according to Johns Hopkins Medicine. But it can also be caused by stimuli like the sight of blood or sudden emotional distress. The stimulus causes the heart rate and blood pressure to drop rapidly, according to the Mayo Clinic.

The randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial included 133 patients with recurrent vasovagal syncope and was published in Annals of Internal Medicine. Those that received midodrine were less likely to have one syncope episode (28 of 66 [42%]), compared with those that took the placebo (41 of 67 [61%]). The absolute risk reduction for vasovagal syncope was 19 percentage points (95% confidence interval, 2-36 percentage points).

The study included patients from 25 university hospitals in Canada, the United States, Mexico, and the United Kingdom, who were followed for 12 months. The trial participants were highly symptomatic for vasovagal syncope, having experienced a median of 23 episodes in their lifetime and 5 syncope episodes in the last year, and they had no comorbid conditions.

“We don’t have many arrows in our quiver,” said Robert Sheldon, MD, PhD, a cardiologist at University of Calgary (Alta.) and lead author of the study, referring to the lack of evidence-based treatments for syncope.

For 20 years Dr. Sheldon’s lab has been testing drugs that showed some potential. While a previous study of fludrocortisone (Florinef ) showed some benefit, “[midodrine] was the first to be unequivocally, slam-dunk positive,” he said in an interview.

Earlier trials of midodrine

Other studies have shown midodrine to prevent syncope on tilt tests. There have been two randomized trials where midodrine significantly reduced vasovagal syncope, but one of these was short and in children, and the other one was open label with no placebo control.

“Risk reduction was very high in previous studies,” Dr. Sheldon said in an interview. But, because they were open label, there was a huge placebo effect, he noted.

“There were no adequately done, adequately powered [studies] that have been positive,” Dr. Sheldon added.

New study methods and outcomes

The study published in Annals of Internal Medicine this week included patients over 18 years of age with a Calgary Syncope Symptom Score of at least 2. All were educated on lifestyle measures that can prevent syncopes before beginning to take 5 mg of study drug or placebo three times daily, 4 hours apart.

In these cases, the study authors wrote, “taking medication three times a day seems worth the effort.” But in patients with a lower frequency of episodes, midodrine might not have an adequate payoff.

These results are “impressive,” said Roopinder K. Sandhu, MD, MPH, clinical electrophysiologist at Cedar-Sinai in Los Angeles. “This study demonstrated that midodrine is the first medical therapy, in addition to education and lifestyle measures, to unequivocally pass the scrutiny of an international, placebo-controlled, RCT to show a significant reduction in syncope recurrence in a younger population with frequent syncope events.”

“[Taking midodrine] doesn’t carry the long-term consequence of pacemakers,” she added.

Study limitations

Limitations of the new study include its small size and short observation period, the authors wrote. Additionally, a large proportion of patients enrolled were also from a single center in Calgary that specializes in syncope care. Twenty-seven patients in the trial stopped taking their assigned medication during the year observation period, but the authors concluded these participants “likely would bias the results against midodrine.”

For doctors considering midodrine for their patients, it’s critical to confirm the diagnosis and to try patient education first, Dr. Sheldon advised.

Lifestyle factors like hydration, adequate sodium intake, and squatting or lying down when the syncope is coming on can sufficiently suppress syncopes in two-thirds of patients, he noted.

This is a treatment for young people, Dr. Sandhu said. The median age in the trial was 35, so patients taking midodrine should be younger than 50. Midodrine is also not effective in patients with high blood pressure or heart failure, she said.

“[Midodrine] is easy to use but kind of a pain at first,” Dr. Sheldon noted. Every patient should start out taking 5 mg doses, three times a day – during waking hours. But then you have to adjust the dosage, “and it’s tricky,” he said.

If a patient experiences goosebumps or the sensation of worms crawling in the hair, the dose might be too much, Dr. Sheldon noted.

If the patient is still fainting, first consider when they are fainting, he said. If it’s around the time they should take another dose, it might be trough effect.

Dr. Sandhu was not involved in the study, but Cedar Sinai was a participating center, and she considers Dr. Sheldon to be a mentor. Dr. Sandhu also noted that she has published papers with Dr. Sheldon, who reported no conflicts.

.

Vasovagal syncope is the most common cause of fainting and is often triggered by dehydration and upright posture, according to Johns Hopkins Medicine. But it can also be caused by stimuli like the sight of blood or sudden emotional distress. The stimulus causes the heart rate and blood pressure to drop rapidly, according to the Mayo Clinic.

The randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial included 133 patients with recurrent vasovagal syncope and was published in Annals of Internal Medicine. Those that received midodrine were less likely to have one syncope episode (28 of 66 [42%]), compared with those that took the placebo (41 of 67 [61%]). The absolute risk reduction for vasovagal syncope was 19 percentage points (95% confidence interval, 2-36 percentage points).

The study included patients from 25 university hospitals in Canada, the United States, Mexico, and the United Kingdom, who were followed for 12 months. The trial participants were highly symptomatic for vasovagal syncope, having experienced a median of 23 episodes in their lifetime and 5 syncope episodes in the last year, and they had no comorbid conditions.

“We don’t have many arrows in our quiver,” said Robert Sheldon, MD, PhD, a cardiologist at University of Calgary (Alta.) and lead author of the study, referring to the lack of evidence-based treatments for syncope.

For 20 years Dr. Sheldon’s lab has been testing drugs that showed some potential. While a previous study of fludrocortisone (Florinef ) showed some benefit, “[midodrine] was the first to be unequivocally, slam-dunk positive,” he said in an interview.

Earlier trials of midodrine

Other studies have shown midodrine to prevent syncope on tilt tests. There have been two randomized trials where midodrine significantly reduced vasovagal syncope, but one of these was short and in children, and the other one was open label with no placebo control.

“Risk reduction was very high in previous studies,” Dr. Sheldon said in an interview. But, because they were open label, there was a huge placebo effect, he noted.

“There were no adequately done, adequately powered [studies] that have been positive,” Dr. Sheldon added.

New study methods and outcomes

The study published in Annals of Internal Medicine this week included patients over 18 years of age with a Calgary Syncope Symptom Score of at least 2. All were educated on lifestyle measures that can prevent syncopes before beginning to take 5 mg of study drug or placebo three times daily, 4 hours apart.

In these cases, the study authors wrote, “taking medication three times a day seems worth the effort.” But in patients with a lower frequency of episodes, midodrine might not have an adequate payoff.

These results are “impressive,” said Roopinder K. Sandhu, MD, MPH, clinical electrophysiologist at Cedar-Sinai in Los Angeles. “This study demonstrated that midodrine is the first medical therapy, in addition to education and lifestyle measures, to unequivocally pass the scrutiny of an international, placebo-controlled, RCT to show a significant reduction in syncope recurrence in a younger population with frequent syncope events.”

“[Taking midodrine] doesn’t carry the long-term consequence of pacemakers,” she added.

Study limitations

Limitations of the new study include its small size and short observation period, the authors wrote. Additionally, a large proportion of patients enrolled were also from a single center in Calgary that specializes in syncope care. Twenty-seven patients in the trial stopped taking their assigned medication during the year observation period, but the authors concluded these participants “likely would bias the results against midodrine.”

For doctors considering midodrine for their patients, it’s critical to confirm the diagnosis and to try patient education first, Dr. Sheldon advised.

Lifestyle factors like hydration, adequate sodium intake, and squatting or lying down when the syncope is coming on can sufficiently suppress syncopes in two-thirds of patients, he noted.

This is a treatment for young people, Dr. Sandhu said. The median age in the trial was 35, so patients taking midodrine should be younger than 50. Midodrine is also not effective in patients with high blood pressure or heart failure, she said.

“[Midodrine] is easy to use but kind of a pain at first,” Dr. Sheldon noted. Every patient should start out taking 5 mg doses, three times a day – during waking hours. But then you have to adjust the dosage, “and it’s tricky,” he said.

If a patient experiences goosebumps or the sensation of worms crawling in the hair, the dose might be too much, Dr. Sheldon noted.

If the patient is still fainting, first consider when they are fainting, he said. If it’s around the time they should take another dose, it might be trough effect.

Dr. Sandhu was not involved in the study, but Cedar Sinai was a participating center, and she considers Dr. Sheldon to be a mentor. Dr. Sandhu also noted that she has published papers with Dr. Sheldon, who reported no conflicts.

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

Married docs remove girl’s lethal facial tumor in ‘excruciatingly difficult’ procedure

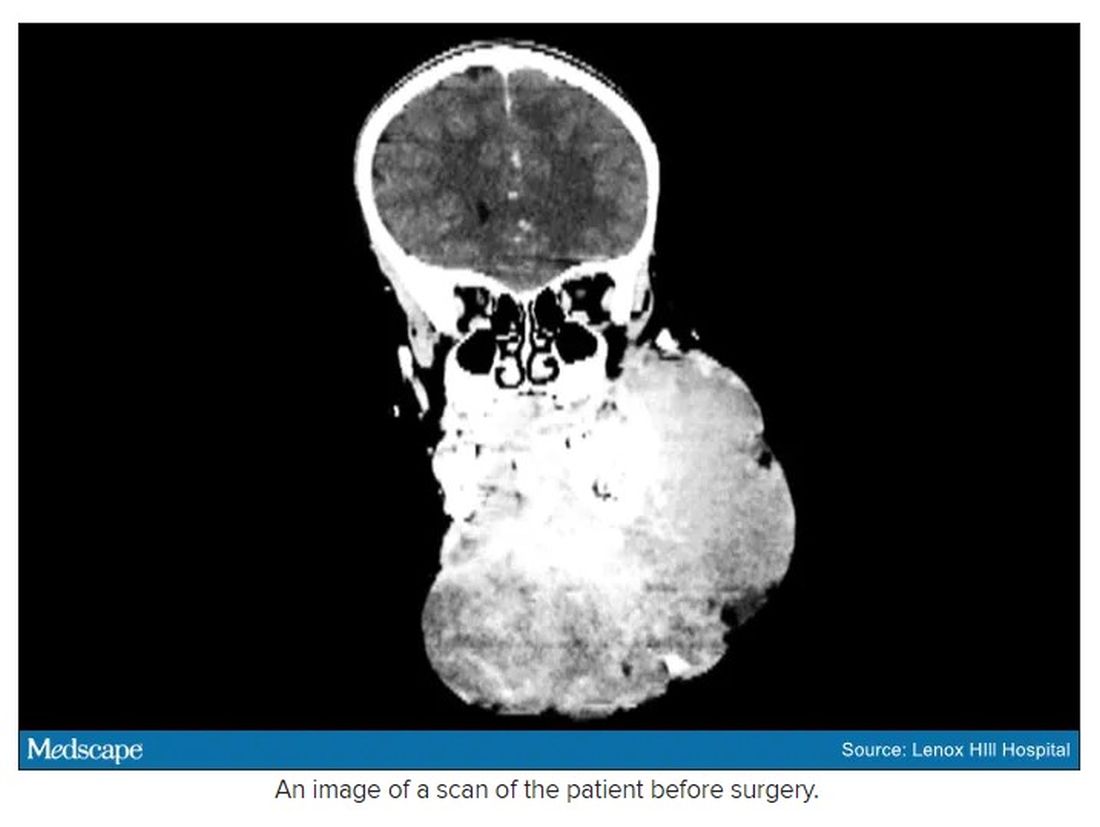

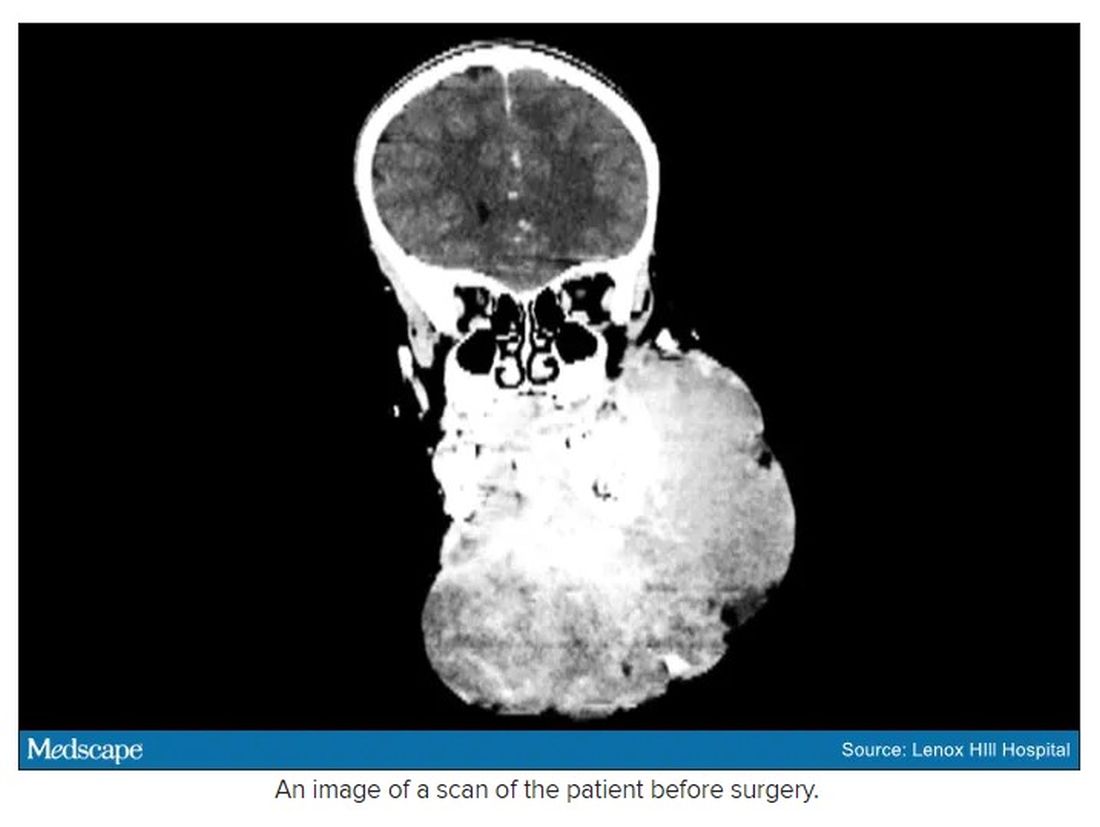

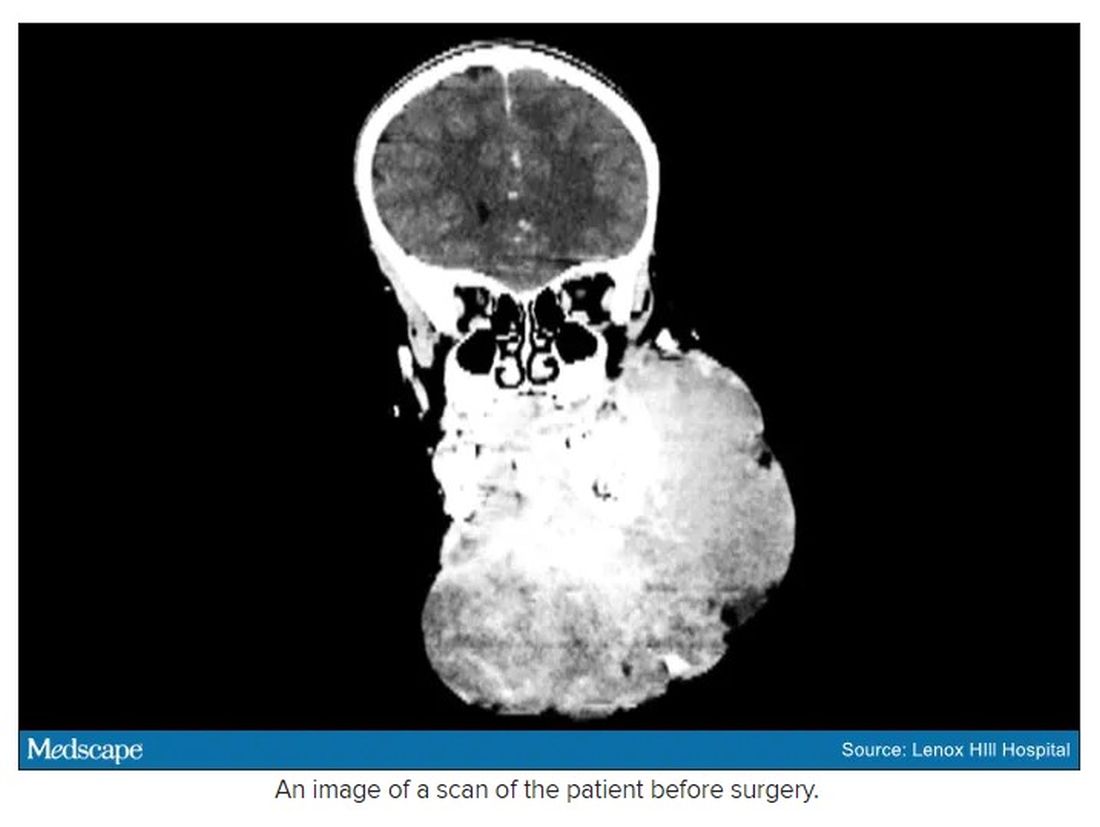

In 2019, doctors in London saw a 5-year old girl from rural Ethiopia with an enormous tumor extending from her cheek to her lower jaw. Her name was Negalem and the tumor was a vascular malformation, a life-threatening web of tangled blood vessels.

Surgery to remove it was impossible, the doctors told the foundation advocating for the girl. The child would never make it off the operating table. After a closer examination, the London group still declined to do the procedure, but told the child’s parents and advocates that if anyone was going to attempt this, they’d need to get the little girl to New York.

In New York City, on 64th St. in Manhattan, is the Vascular Birthmark Institute, founded by Milton Waner, MD, who has exclusively treated hemangiomas and vascular malformations for the last 30 years. “I’m the only person in the [United] States whose practice is exclusively [treating] vascular anomalies,” Dr. Waner said in an interview.

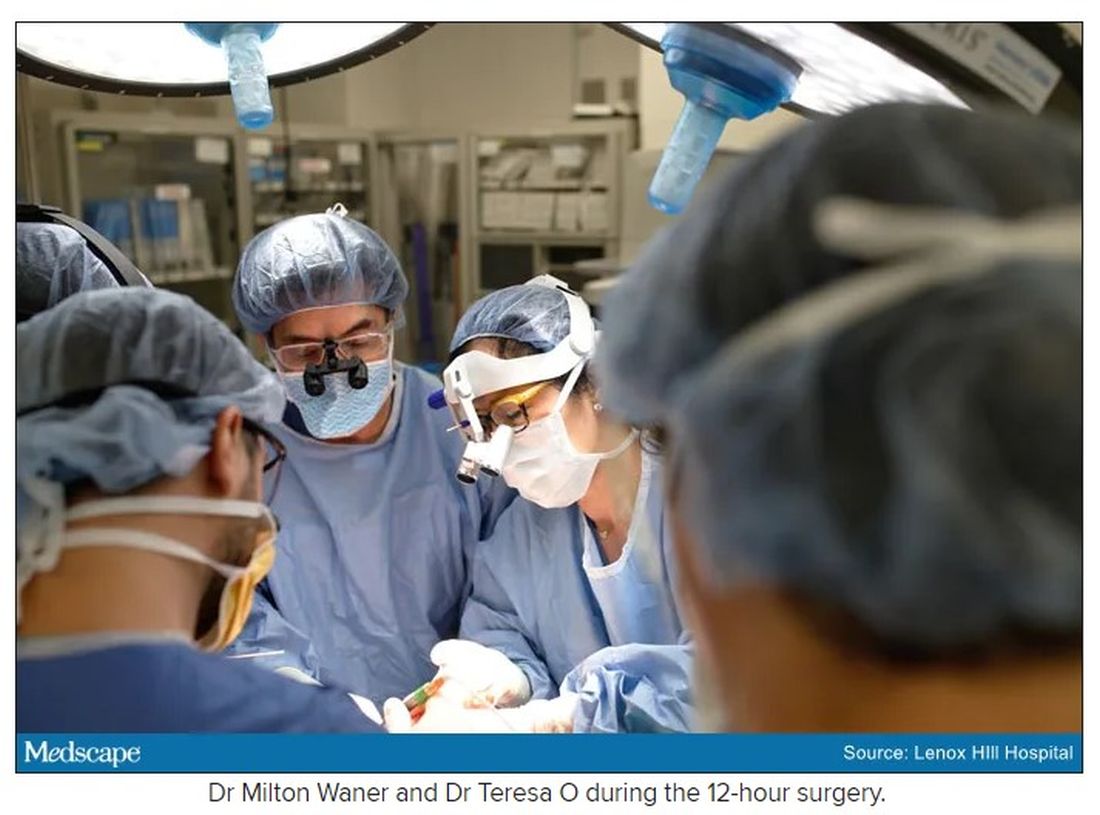

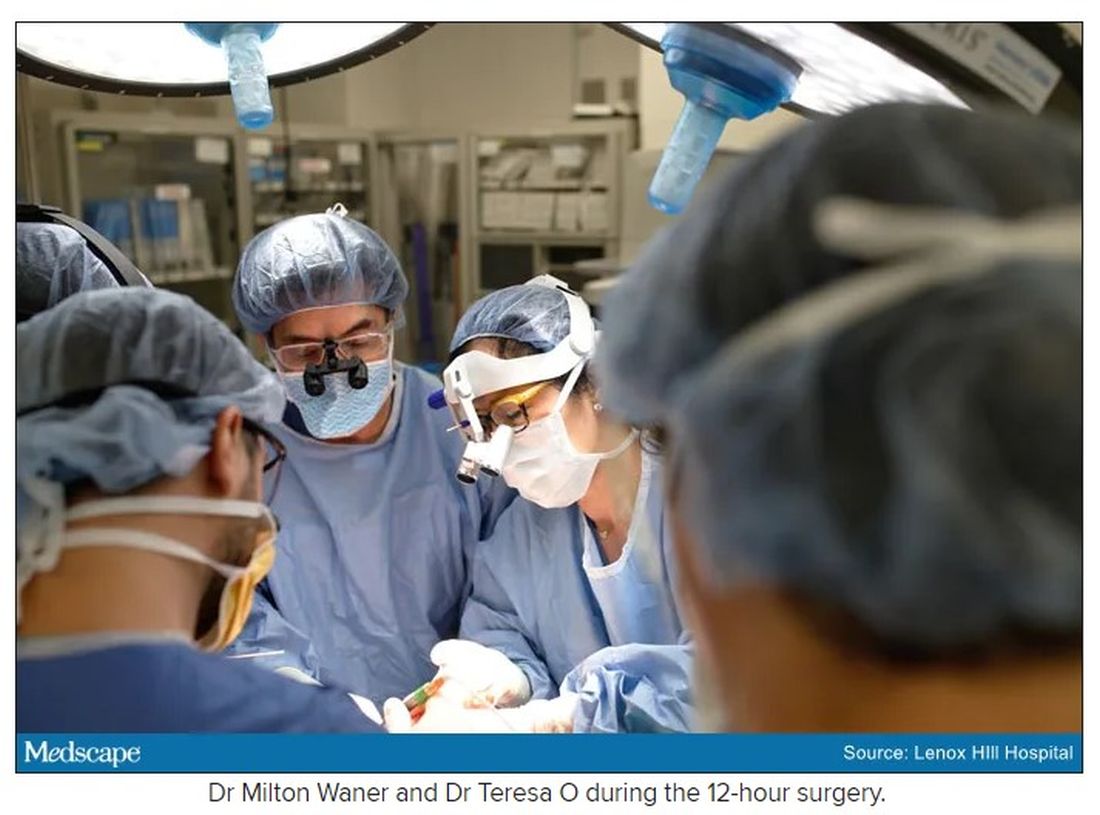

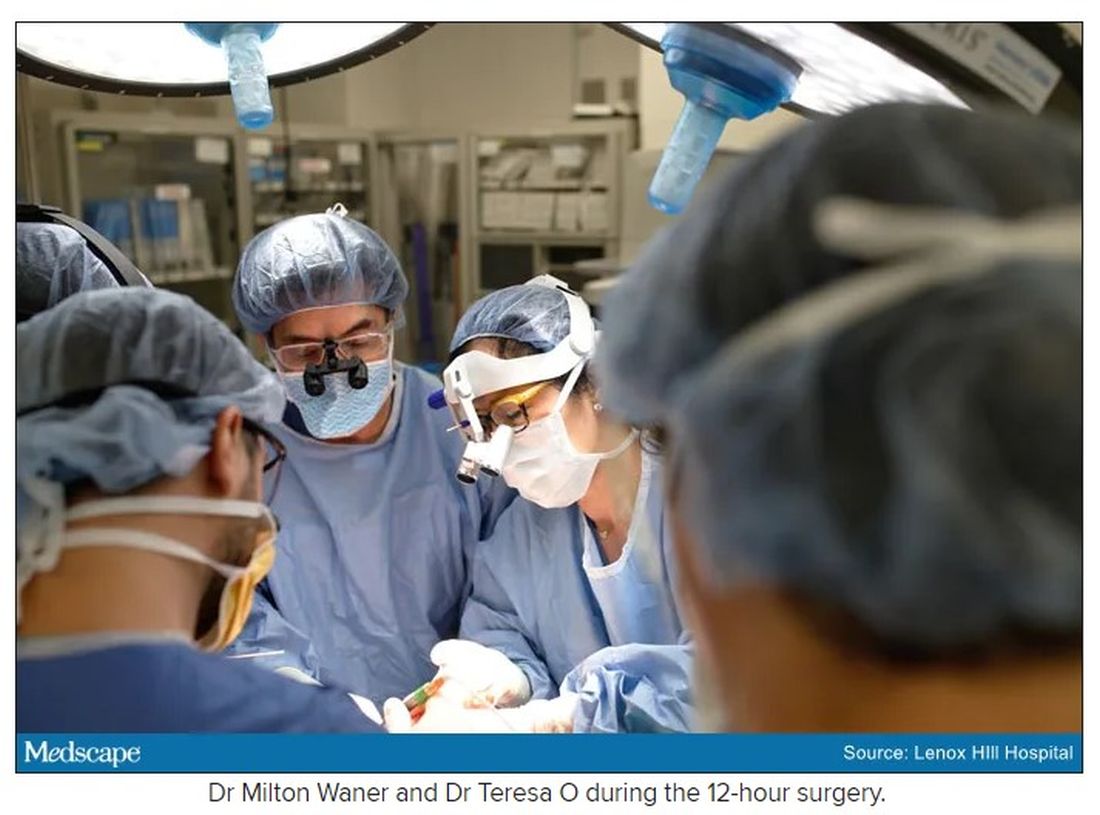

Dr. Waner has assembled a multidisciplinary team of experts at the institute’s offices in Lenox Hill – including his wife Teresa O, MD, a facial plastic and reconstructive surgeon and neurospecialist. “People often ask how the hell do you spend so much time with your spouse?” Dr. Waner says. “We work extremely well together. We complement each other.”

Dr. O and Dr. Waner each manage half of the cases at VBI. And in January they received an email about Negalem. After corresponding with the child’s advocate and reviewing images,

The challenge with vascular malformations in children, Dr. Waner said, is that they have a fraction of the blood an adult has. Where adults have an average of 5 L of blood, a child this age has only 1 L. To lose 200 or 300 mL of blood, “that’s 20% or 30% of their blood volume,” Dr. Waner said. So the removal of such a mass, which requires a meticulous dissection around many blood vessels, carries a high risk of the child bleeding out.

There were some logistical hurdles, but the patient arrived in Manhattan in mid-June, at no cost to her family. The medical visa was organized by a volunteer who also work for USAID. Healing the Children Northeast paid for her travel and the Waner Kids Foundation paid for her hotel stay. Lenox Hill Hospital and Northwell Health covered all hospital costs and postsurgery care. And Dr. O and Dr. Waner did the planning, consult visits, and procedure pro bono.

The surgery was possible because of the generosity of several organizations, but the two surgeons still had a limited time to remove the mass. Under different circumstances, and with the luxury of more time, the patient would have undergone several rounds of sclerotherapy. This procedure, done by interventional radiologists, involves injecting a toxin into the blood vessels, which causes them to clot. Done prior to surgery it can help limit bleeding risk.

On June 23, the morning of the surgery, the patient underwent one round of sclerotherapy. However, it didn’t have the intended effect, Dr. Waner said, “because the lesion was just so massive.”

The team had planned several of their moves ahead of time. But this isn’t the sort of surgery you’d find in a textbook. Because it’s such a unique field, Dr. Waner and Dr. O have developed many of their own techniques along the way. This patient was much like the cases they treat every day, only “several orders of magnitudes greater,” Dr. Waner said. “On a scale of 1 to 10 she was a 12.”

The morning of the surgery, “I was very apprehensive,” Dr. Waner recalled. He vividly remembers the girl’s father repeatedly kissing her to say goodbye as she lay on the operating table, fully aware that this procedure was a life-threatening one. And from the beginning there were challenges, like getting her under anesthesia when the anatomy of her mouth, deformed by the tumor, didn’t allow the anesthesiologists to use their typical tubing. Then, once the skin was removed, it became clear how dilated and tangled the involved blood vessels were. There were many vital structures tangled in the anomaly. “The jugular vein was right there. The carotid artery was right there,” Dr. Waner said. It was extremely difficult to delineate and preserve them, he said.

“That’s why we really took our time. We just went very slowly and deliberately,” Dr. O said. The blood vessels were so dilated that their only option was to move painstakingly slow – otherwise a small nick could be devastating.

But even with the slow pace the surgery was “excruciatingly difficult,” Dr. Waner said. And early on in the dissection he wasn’t quite sure they’d make it out. The sclerotherapy hadn’t done much to prevent bleeding. “At one point every millimeter or 2 that we advanced we got into some bleeding,” Dr. Waner said. “Brisk bleeding.”

Once they got into the surgery they also realized that the growth had adhered to the jaw bone. “There were vessels traversing into the bone, which were hard to control,” Dr. O said.

But finally, both doctors realized they’d be able to remove it. With the lesion removed they began the work of reconstruction and reanimation.

The child’s jaw and cheek bone had grown beyond their normal size to support the growth. They had to shave them down to achieve facial symmetry. The tumor had also inhibited much of the child’s facial nerve control. With it gone, Dr. O began the work of finding all the facial nerve branches and assembling them to reanimate the child’s face.

Before medicine, Dr. O trained as an architect, which, according to Dr. Waner, has equipped her with very good spatial awareness – a valuable skill in the surgical reconstruction phase. After seeing a lecture by Dr. Waner, she immediately saw a fit for her unique interest and skill set. She did fellowship training with Dr. Waner in vascular anomalies, and then went on to specialize in facial nerve reanimation. The proof of Dr. O’s expertise is Negalem’s new, beautiful smile, Dr. Waner said.

The surgery drew out over 8 hours, as long as a day of surgeries for the two doctors. When Dr. O finally walked into the waiting room to inform the family of the success, the first words out of the father’s mouth were: “Is my daughter alive?”

A growth like Negalem had is not compatible with a normal life. Dr. Waner’s mantra is that every child has the right to look normal. But this case went beyond aesthetics. If the growth hadn’t been removed, the child was expected to live only 4-6 more years, Dr. Waner said. Without the surgery, she could have suffocated, starved without the ability to swallow, or suffered a fatal bleed.

Dr. O and Dr. Waner are uniquely equipped to do this kind of work, but both are adamant that treating vascular anomalies is a multidisciplinary, multimodal approach. Specialties in anesthesiology, radiology, lasers, facial nerves – they are all critical to these procedures. And often patients with these kinds of lesions require medical and radiologic interventions in addition to surgery. In this particular case, from logistics to post op, “it was a lot of teamwork,” Dr. O said, “a lot of international teams coming together.”

Though extremely difficult, “in the end the result was exactly what we wanted,” Dr. Waner said. Negalem can live a normal life. And as for the surgical duo, both feel very fortunate to do this work. Dr. O said, “I’m honored to have found this specialty and to be able to train with and work with Milton. I’m so happy to do what I do every day.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In 2019, doctors in London saw a 5-year old girl from rural Ethiopia with an enormous tumor extending from her cheek to her lower jaw. Her name was Negalem and the tumor was a vascular malformation, a life-threatening web of tangled blood vessels.

Surgery to remove it was impossible, the doctors told the foundation advocating for the girl. The child would never make it off the operating table. After a closer examination, the London group still declined to do the procedure, but told the child’s parents and advocates that if anyone was going to attempt this, they’d need to get the little girl to New York.

In New York City, on 64th St. in Manhattan, is the Vascular Birthmark Institute, founded by Milton Waner, MD, who has exclusively treated hemangiomas and vascular malformations for the last 30 years. “I’m the only person in the [United] States whose practice is exclusively [treating] vascular anomalies,” Dr. Waner said in an interview.

Dr. Waner has assembled a multidisciplinary team of experts at the institute’s offices in Lenox Hill – including his wife Teresa O, MD, a facial plastic and reconstructive surgeon and neurospecialist. “People often ask how the hell do you spend so much time with your spouse?” Dr. Waner says. “We work extremely well together. We complement each other.”

Dr. O and Dr. Waner each manage half of the cases at VBI. And in January they received an email about Negalem. After corresponding with the child’s advocate and reviewing images,

The challenge with vascular malformations in children, Dr. Waner said, is that they have a fraction of the blood an adult has. Where adults have an average of 5 L of blood, a child this age has only 1 L. To lose 200 or 300 mL of blood, “that’s 20% or 30% of their blood volume,” Dr. Waner said. So the removal of such a mass, which requires a meticulous dissection around many blood vessels, carries a high risk of the child bleeding out.

There were some logistical hurdles, but the patient arrived in Manhattan in mid-June, at no cost to her family. The medical visa was organized by a volunteer who also work for USAID. Healing the Children Northeast paid for her travel and the Waner Kids Foundation paid for her hotel stay. Lenox Hill Hospital and Northwell Health covered all hospital costs and postsurgery care. And Dr. O and Dr. Waner did the planning, consult visits, and procedure pro bono.

The surgery was possible because of the generosity of several organizations, but the two surgeons still had a limited time to remove the mass. Under different circumstances, and with the luxury of more time, the patient would have undergone several rounds of sclerotherapy. This procedure, done by interventional radiologists, involves injecting a toxin into the blood vessels, which causes them to clot. Done prior to surgery it can help limit bleeding risk.

On June 23, the morning of the surgery, the patient underwent one round of sclerotherapy. However, it didn’t have the intended effect, Dr. Waner said, “because the lesion was just so massive.”

The team had planned several of their moves ahead of time. But this isn’t the sort of surgery you’d find in a textbook. Because it’s such a unique field, Dr. Waner and Dr. O have developed many of their own techniques along the way. This patient was much like the cases they treat every day, only “several orders of magnitudes greater,” Dr. Waner said. “On a scale of 1 to 10 she was a 12.”

The morning of the surgery, “I was very apprehensive,” Dr. Waner recalled. He vividly remembers the girl’s father repeatedly kissing her to say goodbye as she lay on the operating table, fully aware that this procedure was a life-threatening one. And from the beginning there were challenges, like getting her under anesthesia when the anatomy of her mouth, deformed by the tumor, didn’t allow the anesthesiologists to use their typical tubing. Then, once the skin was removed, it became clear how dilated and tangled the involved blood vessels were. There were many vital structures tangled in the anomaly. “The jugular vein was right there. The carotid artery was right there,” Dr. Waner said. It was extremely difficult to delineate and preserve them, he said.

“That’s why we really took our time. We just went very slowly and deliberately,” Dr. O said. The blood vessels were so dilated that their only option was to move painstakingly slow – otherwise a small nick could be devastating.

But even with the slow pace the surgery was “excruciatingly difficult,” Dr. Waner said. And early on in the dissection he wasn’t quite sure they’d make it out. The sclerotherapy hadn’t done much to prevent bleeding. “At one point every millimeter or 2 that we advanced we got into some bleeding,” Dr. Waner said. “Brisk bleeding.”

Once they got into the surgery they also realized that the growth had adhered to the jaw bone. “There were vessels traversing into the bone, which were hard to control,” Dr. O said.

But finally, both doctors realized they’d be able to remove it. With the lesion removed they began the work of reconstruction and reanimation.

The child’s jaw and cheek bone had grown beyond their normal size to support the growth. They had to shave them down to achieve facial symmetry. The tumor had also inhibited much of the child’s facial nerve control. With it gone, Dr. O began the work of finding all the facial nerve branches and assembling them to reanimate the child’s face.

Before medicine, Dr. O trained as an architect, which, according to Dr. Waner, has equipped her with very good spatial awareness – a valuable skill in the surgical reconstruction phase. After seeing a lecture by Dr. Waner, she immediately saw a fit for her unique interest and skill set. She did fellowship training with Dr. Waner in vascular anomalies, and then went on to specialize in facial nerve reanimation. The proof of Dr. O’s expertise is Negalem’s new, beautiful smile, Dr. Waner said.

The surgery drew out over 8 hours, as long as a day of surgeries for the two doctors. When Dr. O finally walked into the waiting room to inform the family of the success, the first words out of the father’s mouth were: “Is my daughter alive?”

A growth like Negalem had is not compatible with a normal life. Dr. Waner’s mantra is that every child has the right to look normal. But this case went beyond aesthetics. If the growth hadn’t been removed, the child was expected to live only 4-6 more years, Dr. Waner said. Without the surgery, she could have suffocated, starved without the ability to swallow, or suffered a fatal bleed.

Dr. O and Dr. Waner are uniquely equipped to do this kind of work, but both are adamant that treating vascular anomalies is a multidisciplinary, multimodal approach. Specialties in anesthesiology, radiology, lasers, facial nerves – they are all critical to these procedures. And often patients with these kinds of lesions require medical and radiologic interventions in addition to surgery. In this particular case, from logistics to post op, “it was a lot of teamwork,” Dr. O said, “a lot of international teams coming together.”

Though extremely difficult, “in the end the result was exactly what we wanted,” Dr. Waner said. Negalem can live a normal life. And as for the surgical duo, both feel very fortunate to do this work. Dr. O said, “I’m honored to have found this specialty and to be able to train with and work with Milton. I’m so happy to do what I do every day.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In 2019, doctors in London saw a 5-year old girl from rural Ethiopia with an enormous tumor extending from her cheek to her lower jaw. Her name was Negalem and the tumor was a vascular malformation, a life-threatening web of tangled blood vessels.

Surgery to remove it was impossible, the doctors told the foundation advocating for the girl. The child would never make it off the operating table. After a closer examination, the London group still declined to do the procedure, but told the child’s parents and advocates that if anyone was going to attempt this, they’d need to get the little girl to New York.

In New York City, on 64th St. in Manhattan, is the Vascular Birthmark Institute, founded by Milton Waner, MD, who has exclusively treated hemangiomas and vascular malformations for the last 30 years. “I’m the only person in the [United] States whose practice is exclusively [treating] vascular anomalies,” Dr. Waner said in an interview.

Dr. Waner has assembled a multidisciplinary team of experts at the institute’s offices in Lenox Hill – including his wife Teresa O, MD, a facial plastic and reconstructive surgeon and neurospecialist. “People often ask how the hell do you spend so much time with your spouse?” Dr. Waner says. “We work extremely well together. We complement each other.”

Dr. O and Dr. Waner each manage half of the cases at VBI. And in January they received an email about Negalem. After corresponding with the child’s advocate and reviewing images,

The challenge with vascular malformations in children, Dr. Waner said, is that they have a fraction of the blood an adult has. Where adults have an average of 5 L of blood, a child this age has only 1 L. To lose 200 or 300 mL of blood, “that’s 20% or 30% of their blood volume,” Dr. Waner said. So the removal of such a mass, which requires a meticulous dissection around many blood vessels, carries a high risk of the child bleeding out.

There were some logistical hurdles, but the patient arrived in Manhattan in mid-June, at no cost to her family. The medical visa was organized by a volunteer who also work for USAID. Healing the Children Northeast paid for her travel and the Waner Kids Foundation paid for her hotel stay. Lenox Hill Hospital and Northwell Health covered all hospital costs and postsurgery care. And Dr. O and Dr. Waner did the planning, consult visits, and procedure pro bono.

The surgery was possible because of the generosity of several organizations, but the two surgeons still had a limited time to remove the mass. Under different circumstances, and with the luxury of more time, the patient would have undergone several rounds of sclerotherapy. This procedure, done by interventional radiologists, involves injecting a toxin into the blood vessels, which causes them to clot. Done prior to surgery it can help limit bleeding risk.

On June 23, the morning of the surgery, the patient underwent one round of sclerotherapy. However, it didn’t have the intended effect, Dr. Waner said, “because the lesion was just so massive.”