User login

Prevention of Hospital‐Acquired VTE

Pulmonary embolism (PE) and deep vein thrombosis (DVT), collectively referred to as venous thromboembolism (VTE), represent a major public health problem, affecting hundreds of thousands of Americans each year.1 The best estimates are that at least 100,000 deaths are attributable to VTE each year in the United States alone.1 VTE is primarily a problem of hospitalized and recently‐hospitalized patients.2 Although a recent meta‐analysis did not prove mortality benefit of prophylaxis in the medical population,3 PE is frequently estimated to be the most common preventable cause of hospital death.46

Pharmacologic methods to prevent VTE are safe, effective, cost‐effective, and advocated by authoritative guidelines.7 Even though the majority of medical and surgical inpatients have multiple risk factors for VTE, large prospective studies continue to demonstrate that these preventive methods are significantly underutilized, often with only 30% to 50% eligible patients receiving prophylaxis.812

The reasons for this underutilization include lack of physician familiarity or agreement with guidelines, underestimation of VTE risk, concern over risk of bleeding, and the perception that the guidelines are resource‐intensive or difficult to implement in a practical fashion.13 While many VTE risk‐assessment models are available in the literature,1418 a lack of prospectively validated models and issues regarding ease of use have further hampered widespread integration of VTE risk assessments into order sets and inpatient practice.

We sought to optimize prevention of hospital‐acquired (HA) VTE in our 350‐bed tertiary‐care academic center using a VTE prevention protocol and a multifaceted approach that could be replicated across a wide variety of medical centers.

Patients and Methods

Study Design

We developed, implemented, and refined a VTE prevention protocol and examined the impact of our efforts. We observed adult inpatients on a longitudinal basis for the prevalence of adequate VTE prophylaxis and for the incidence of HA VTE throughout a 36‐month period from calendar year 2005 through 2007, and performed a retrospective analysis for any potential adverse effects of increased VTE prophylaxis. The project adhered to the HIPAA requirements for privacy involving health‐related data from human research participants. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of California, San Diego, which waived the requirement for individual patient informed consent.

We included all hospitalized adult patients (medical and surgical services) at our medical center in our observations and interventions, including patients of all ethnic groups, geriatric patients, prisoners, and the socially and economically disadvantaged in our population. Exclusion criteria were age under 14 years, and hospitalization on Psychiatry or Obstetrics/Gynecology services.

Development of a VTE Risk‐assessment Model and VTE Prevention Protocol

A core multidisciplinary team with hospitalists, pulmonary critical care VTE experts, pharmacists, nurses, and information specialists was formed. After gaining administrative support for standardization, we worked with medical staff leaders to gain consensus on a VTE prevention protocol for all medical and surgical areas from mid‐2005 through mid‐2006. The VTE prevention protocol included the elements of VTE risk stratification, definitions of adequate VTE prevention measures linked to the level of VTE risk, and definitions for contraindications to pharmacologic prophylactic measures. We piloted risk‐assessment model (RAM) drafts for ease of use and clarity, using rapid cycle feedback from pharmacy residents, house staff, and medical staff attending physicians. Models often cited in the literature15, 18 that include point‐based scoring of VTE risk factors (with prophylaxis choices hinging on the additive sum of scoring) were rejected based on the pilot experience.

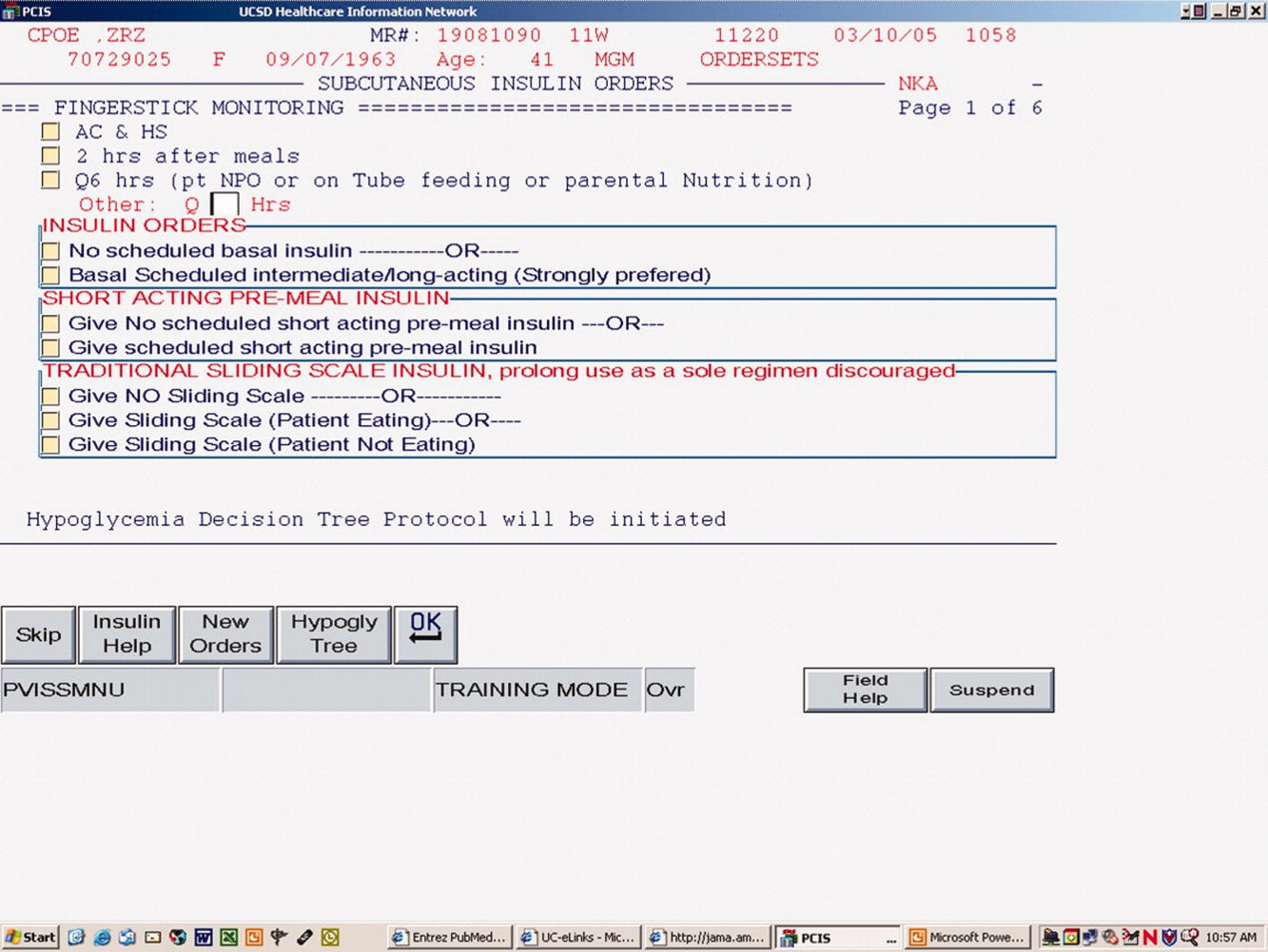

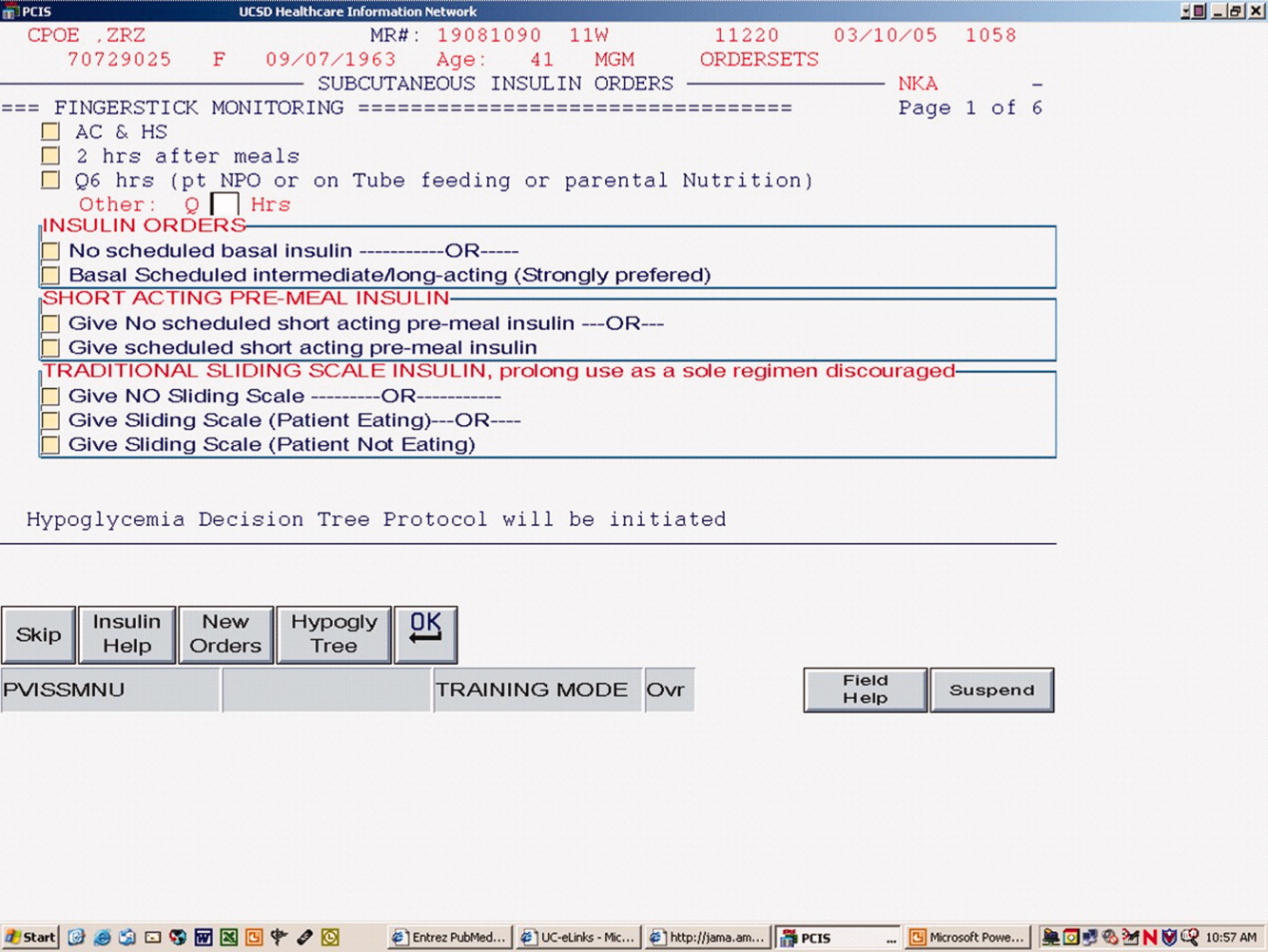

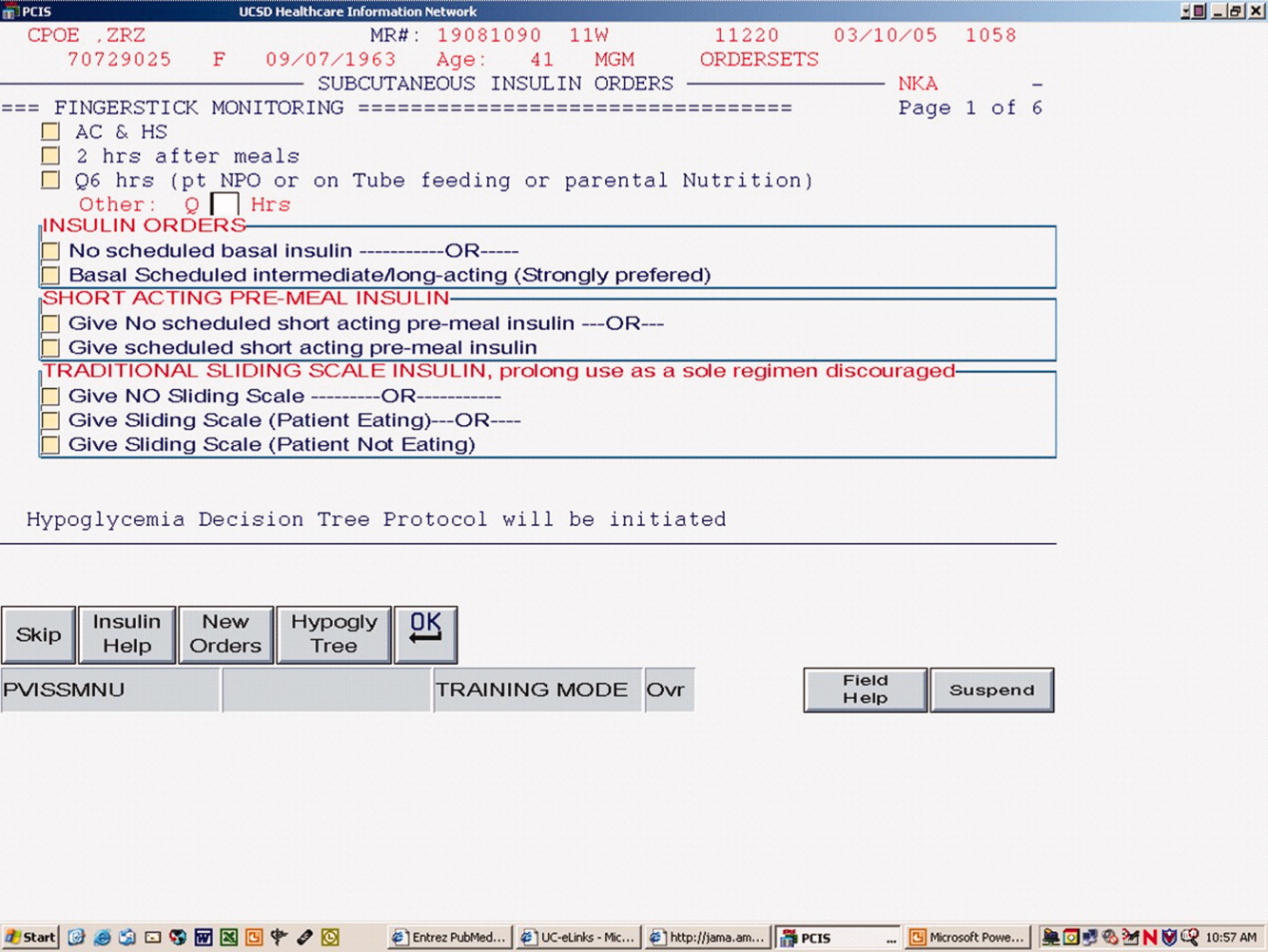

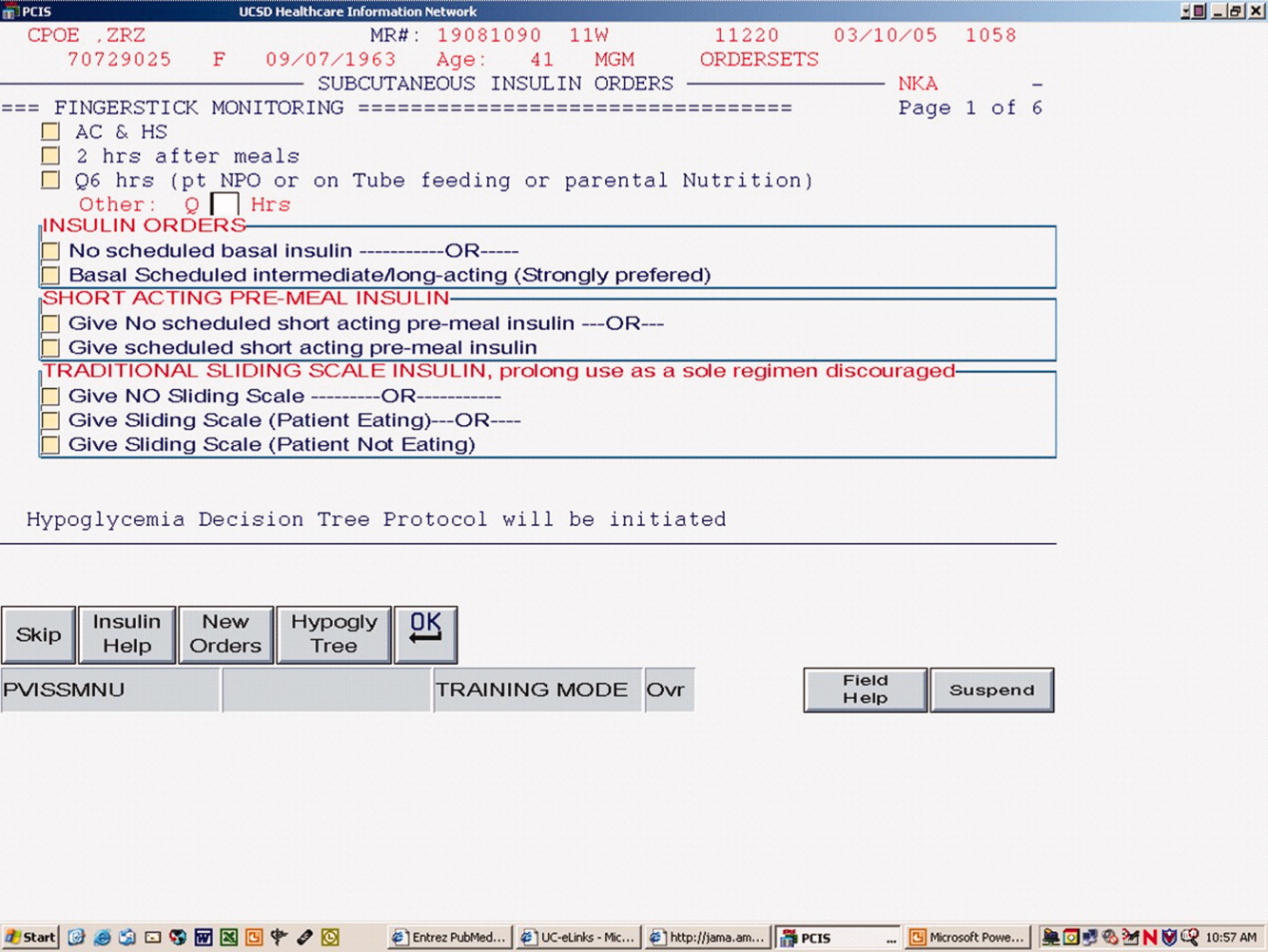

We adopted a simple model with 3 levels of VTE risk that could be completed by the physician in seconds, and then proceeded to integrate this RAM into standardized data collection instruments and eventually (April 2006) into a computerized provider order entry (CPOE) order set (Siemmens Invision v26). Each level of VTE risk was firmly linked to a menu of acceptable prophylaxis options (Table 1). Simple text cues were used to define risk assessment, with more exhaustive listings of risk factors being relegated to accessible reference tables.

| Low | Moderate | High |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Ambulatory patient without VTE risk factors; observation patient with expected LOS 2 days; same day surgery or minor surgery | All other patients (not in low‐risk or high‐risk category); most medical/surgical patients; respiratory insufficiency, heart failure, acute infectious, or inflammatory disease | Lower extremity arthroplasty; hip, pelvic, or severe lower extremity fractures; acute SCI with paresis; multiple major trauma; abdominal or pelvic surgery for cancer |

| Early ambulation | UFH 5000 units SC q 8 hours; OR LMWH q day; OR UFH 5000 units SC q 12 hours (if weight < 50 kg or age > 75 years); AND suggest adding IPC | LMWH (UFH if ESRD); OR fondaparinux 2.5 mg SC daily; OR warfarin, INR 2‐3; AND IPC (unless not feasible) |

Intermittent pneumatic compression devices were endorsed as an adjunct in all patients in the highest risk level, and as the primary method in patients with contraindications to pharmacologic prophylaxis. Aspirin was deemed an inappropriate choice for VTE prophylaxis. Subcutaneous unfractionated or low‐molecular‐weight heparin were endorsed as the primary method of prophylaxis for the majority of patients without contraindications.

Integration of the VTE Protocol into Order Sets

An essential strategy for the success of the VTE protocol included integrating guidance for the physician into the flow of patient care, via standardized order sets. The CPOE VTE prevention order set was modular by design, as opposed to a stand alone design. After conferring with appropriate stakeholders, preexisting and nonstandardized prompts for VTE prophylaxis were removed from commonly used order sets, and the standardized module was inserted in its place. This allowed for integration of the standardized VTE prevention module into all admission and transfer order sets, essentially insuring that all patients admitted or transferred within the medical center would be exposed to the protocol. Physicians using a variety of admission and transfer order sets were prompted to select each patient's risk for VTE, and declare the presence or absence of contraindications to pharmacologic prophylaxis. Only the VTE prevention options most appropriate for the patient's VTE and anticoagulation risk profile were presented as the default choice for VTE prophylaxis. Explicit designation of VTE risk level and a prophylaxis choice were presented in a hard stop mechanism, and utilization of these orders was therefore mandatory, not optional. Proper use (such as the proper classification of VTE risk by the ordering physician) was actively monitored on an auditing basis, and order sets were modified occasionally on the basis of subjective and objective feedback.

Assessment of VTE Risk Assessment Interobserver Agreement

Data from 150 randomly selected patients from the audit pool (from late 2005 through mid‐2006) were abstracted by the nurse practitioner in a detailed manner. Five independent reviewers assessed each patient for VTE risk level, and for a determination of whether or not they were on adequate VTE prophylaxis on the day of the audit per protocol. Interobserver agreement was calculated for these parameters using kappa scores.

Prospective Monitoring of Adequate VTE Prophylaxis

A daily medical center inpatient census report of eligible patients in the medical center for >48 hours was downloaded into an Microsoft Excel spreadsheet, with each patient assigned a consecutive number. The Excel random number generator plug‐in function was used to generate a randomly sequenced list of the patients. The research nurse practitioner targeted serial patients on the list for further study, until she accomplished the requisite number of audits each day. The mean number of audits per month declined over the study years as the trends stabilized and as grant funding expired, but remained robust throughout (2005: 107 audits per month; 2006: 80 audits per month; and 2007: 57 audits per month).

The data collected on each patient randomly selected for audit included age, gender, location, service, date and time of review, and date of admission. The audit VTE RAM (identical to the VTE RAM incorporated into the order set), was used to classify each patient's VTE risk as low, moderate, or high. For each audit, we determined if the patient was on an adequate VTE prevention regimen consistent with our protocol, given their VTE risk level, demographics, and absence or presence of contraindications to pharmacologic prophylaxis. All questionable cases were reviewed by at least 2 physicians at weekly meetings with a final consensus determination. Adequacy of the VTE regimen was judged by orders entered on the day of the audit, but we also noted whether or not ordered intermittent compression devices were in place and functioning at the time of the audit.

Prospective (Concurrent) Discovery and Analysis of VTE Cases

The team nurse practitioner used the PACS radiology reporting and archival system (IMPAX version 4.5; AGFA Healthcare Informatics, Greenville, SC) to identify all new diagnoses of VTE, in the process described below.

Procedure codes for following studies were entered into the IMPAX search engine to locate all such exams performed in the previous 1 to 3 days:

Ultrasound exams of the neck, upper extremities, and lower extremities;

Computed tomography (CT) angiograms of the chest;

Ventilation/perfusion nuclear medicine scans; and

Pulmonary angiograms.

Negative studies and studies that revealed unchanged chronic thromboses were excluded, while clots with a chronic appearance but no evidence of prior diagnosis were included. Iliofemoral, popliteal, calf vein, subclavian, internal and external jugular vein, and axillary vein thromboses were therefore included, as were all PEs. Less common locations, such as renal vein and cavernous sinus thromboses, were excluded. The improvement/research team exerted no influence over decisions about whether or not testing was done.

Each new case of VTE was then classified as HA VTE or community‐acquired VTE. A new VTE was classified as HA if the diagnosis was first suspected and made in the hospital. A newly diagnosed VTE was also classified as HA if the VTE was suspected in the ambulatory setting, but the patient had been hospitalized within the arbitrary window of the preceding 30 days.

Each new diagnosis of HA VTE was reviewed by core members of the multidisciplinary support team. This investigation included a determination of whether the patient was on an adequate VTE prophylaxis regimen at the time of the HA VTE, using the RAM and linked prophylaxis menu described above. The VTE prevention regimen ordered at the time the inpatient developed the HA VTE was classified as adherent or nonadherent to the University of California, San Diego (UCSD) protocol: patients who developed VTE when on suboptimal prophylaxis per protocol were classified as having a potentially preventable case. Potentially iatrogenic precipitants of VTE (such as the presence of a central venous catheter or restraints) were also noted. All data were entered into a Microsoft Access database for ease of retrieval and reporting.

All tests for VTE were performed based on clinical signs and symptoms, rather than routine screening, except for the Trauma and Burn services, which also screen for VTE in high‐risk patients per their established screening protocols.

Statistical Analysis of VTE Prophylaxis and HA VTE Cases

Gender differences between cases of VTE and randomly sampled and audited inpatients were examined by chi‐square analysis, and analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to examine any age or body mass index (BMI) differences between audits and cases.

The unadjusted risk ratio (RR) for adequate prophylaxis was compared by year, with year 2005 being the baseline (comparison) year, by chi‐square analysis.

The unadjusted RR of HA VTE was calculated by dividing the number of cases found in the calendar year by the hospital census of adult inpatients at risk. For each case, a classification for the type of VTE (PE vs. DVT vs. combinations) was recorded. Cases not receiving adequate prophylaxis were categorized as preventable DVT. Unadjusted RRs were calculated for each year by chi‐square analysis, compared to the baseline (2005) year.

All data were analyzed using Stata (version 10; Stata Corp., College Station, TX). Results for the different analysis were considered significant at P < 0.05.

Retrospective Study of Unintentional Adverse Effects

The increase in anticoagulant use accompanying the introduction of the VTE prophylaxis order set warranted an evaluation of any subsequent rise in related adverse events. A study was done to determine the rates of bleeding and heparin‐induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) before and after the implementation of the VTE prophylaxis order set.

A retrospective analysis was conducted to evaluate outcomes in our inpatients from December 2004 through November 2006, with April to November, 2006 representing the post‐order set implementation time period. Any patient with a discharge diagnosis code of e934.2 (anticoagulant‐related adverse event) was selected for study to identify possible bleeding attributable to pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis. Major or minor bleeding attributable to pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis was defined as a bleed occurring 72 hours after receiving pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis. Major bleeding was defined as cerebrovascular, gastrointestinal, retroperitoneal, or overt bleeding with a decrease in hemoglobin 2 mg/dL with clinical symptoms such as hypotension or hypoxia (not associated with hemodialysis) or transfusion of 2 units of packed red blood cells. Minor bleeding was defined as ecchymosis, epistaxis, hematoma, hematuria, hemoptysis, petechiae, or bleeding without a decrease in hemoglobin 2 g/dL.

Possible cases of HIT were identified by screening for a concomitant secondary thrombocytopenia code (287.4). Chart review was then conducted to determine a causal relationship between the use of pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis and adverse events during the hospital stay. HIT attributable to pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis was determined by assessing if patients developed any of the following clinical criteria after receiving pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis: platelet count <150 109/L or 50% decrease from baseline, with or without an associated venous or arterial thrombosis or other sequelae (skin lesions at injection site, acute systemic reaction) and/or a positive heparin‐induced platelet activation (HIPA) test. In order to receive a diagnosis of HIT, thrombocytopenia must have occurred between days 5 to 15 of heparin therapy, unless existing evidence suggested that the patient developed rapid‐onset HIT or delayed‐onset HIT. Rapid‐onset HIT was defined as an abrupt drop in platelet count upon receiving a heparin product, due to heparin exposure within the previous 100 days. Delayed‐onset HIT was defined as HIT that developed several days after discontinuation of heparin. Other evident causes of thrombocytopenia were ruled out.

Statistical Analysis of Retrospective Study of Unintentional Adverse Effects

Regression analysis with chi‐square and ANOVA were used in the analysis of the demographic data. RRs were calculated for the number of cases coded with an anticoagulant‐related adverse event secondary thrombocytopenia before and after the order set implementation.

Educational Efforts and Feedback

Members of the multidisciplinary team presented information on HA VTE and the VTE prevention protocol at Medical and Surgical grand rounds, teaching rounds, and noon conference, averaging 1 educational session per quarter. Feedback and education was provided to physicians and nursing staff when audits revealed that a patient had inadequate prophylaxis with reference to the protocol standard. In addition, these conversations provided on opportunity to explore reasons for nonadherence with the protocol, confusion regarding the VTE RAM, and other barriers to effective prophylaxis, thereby providing guidance for further protocol revision and educational efforts. We adjusted the order set based on active monitoring of order set use and the audit process.

Results

There were 30,850 adult medical/surgical inpatients admitted to the medical center with a length of stay of 48 hours or more in 2005 to 2007, representing 186,397 patient‐days of observation. A total of 2,924 of these patients were randomly sampled during the VTE prophylaxis audit process (mean 81 audits per month). Table 2 shows the characteristics of randomly sampled audit patients and of the patients diagnosed with HA VTE. The demographics of the 30,850‐inpatient population (mean age = 50 years; 60.7% male; 52% Surgical Services) mirrored the demographics of the randomly sampled inpatients that underwent audits, validating the random sampling methods.

| Number (n = 3285) | % of Study Population* | Cases (n = 361) [n (%)] | Audits (n = 2924) [n (%)] | OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Age (years) mean SD | 51 16 (range 15‐100) | 53 17 | 50 17 | 1.01 (1.003‐1.016) | |

| Gender, males | 1993 | 61 | 213 (59) | 1782 (61) | 0.93 (0.744‐1.16) |

| Major service: | |||||

| Surgery | 1714 | 52 | 200 (55) | 1516 (52) | |

| Medicine | 1566 | 48 | 161 (45) | 1408 (48) | |

| Service, detail | |||||

| Hospitalist | 1041 | 32 | 83 (23) | 958 (33) | |

| General surgery | 831 | 25 | 75 (21) | 756 (26) | |

| Trauma | 419 | 13 | 77 (22) | 342 (12) | |

| Cardiology | 313 | 10 | 45 (13) | 268 (9) | |

| Orthopedics | 244 | 7 | 15 (4) | 229 (8) | |

| Burn unit | 205 | 6 | 29 (8) | 176 (6) | |

| Other | 222 | 7 | 30 (8) | 192 (7) | |

The majority of inpatients sampled in the audits were in the moderate VTE risk category (84%), 12% were in the high‐risk category, and 4% were in the low‐risk category. The distribution of VTE risk did not change significantly over this time period.

Interobserver Agreement

The VTE RAM interobserver agreement was assessed on 150 patients with 5 observers as described above. The kappa score for the VTE risk level was 0.81. The kappa score for the judgment of whether the patient was on adequate prophylaxis or not was 0.90.

Impact on Percent of Patients with Adequate Prophylaxis (Longitudinal Audits)

Audits of randomly sampled inpatients occurred longitudinally throughout the study period as described above. Based on the intervention, the percent of patients on adequate prophylaxis improved significantly (P < 0.001) by each calendar year (see Table 3), from a baseline of 58% in 2005 to 78% in 2006 (unadjusted relative benefit = 1.35; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.28‐1.43), and 93% in 2007 (unadjusted relative benefit = 1.61; 95% CI = 1.52, 1.69). The improvement seen was more marked in the moderate VTE risk patients when compared to the high VTE risk patients. The percent of audited VTE prophylaxis improved from 53% in calendar year (CY) 2005 to 93% in 2007 (unadjusted relative benefit = 1.75; 95% CI = 1.70‐1.81) in the moderate VTE risk group, while the high VTE risk group improved from 83% to 92% in the same time period (unadjusted relative benefit = 1.11; 95% CI = 0.95‐1.25).

| 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| All audits | 1279 | 960 | 679 |

| Prophylaxis adequate, n (%) | 740 (58) | 751 (78) | 631 (93) |

| Relative benefit (95% CI) | 1 | 1.35* (1.28‐1.43) | 1.61* (1.52‐1.69) |

Overall, adequate VTE prophylaxis was present in over 98% of audited patients in the last 6 months of 2007, and this high rate has been sustained throughout 2008. Age, ethnicity, and gender were not associated with differential rates of adequate VTE prophylaxis.

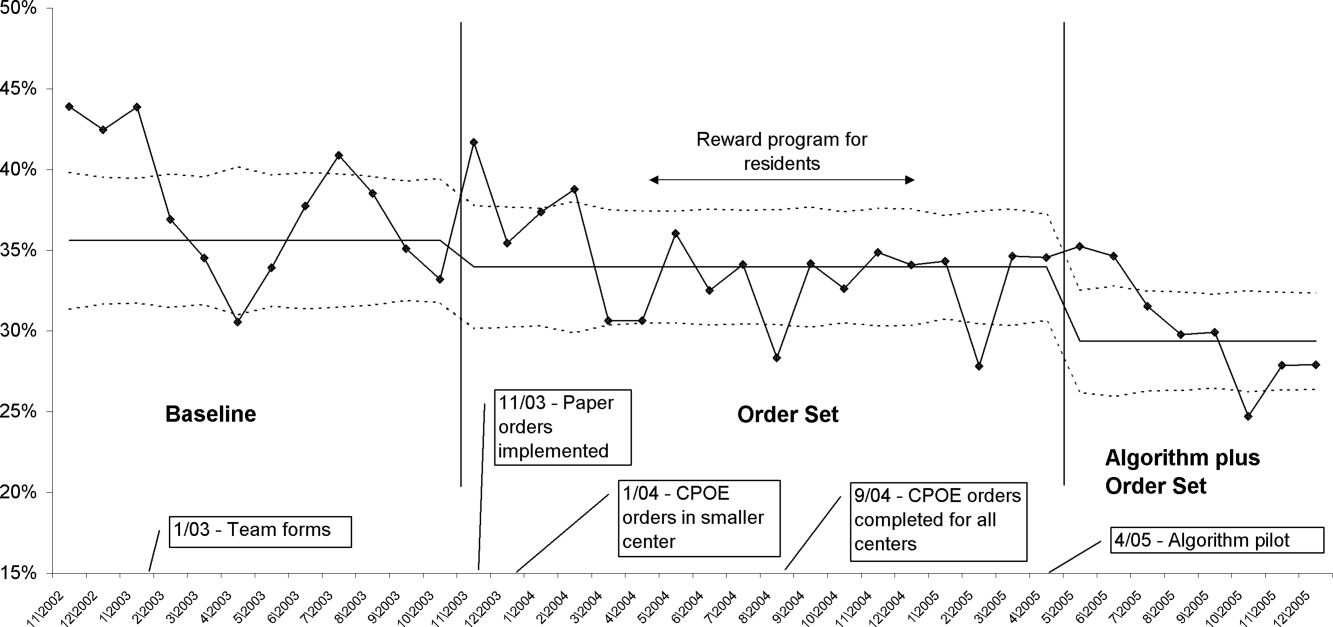

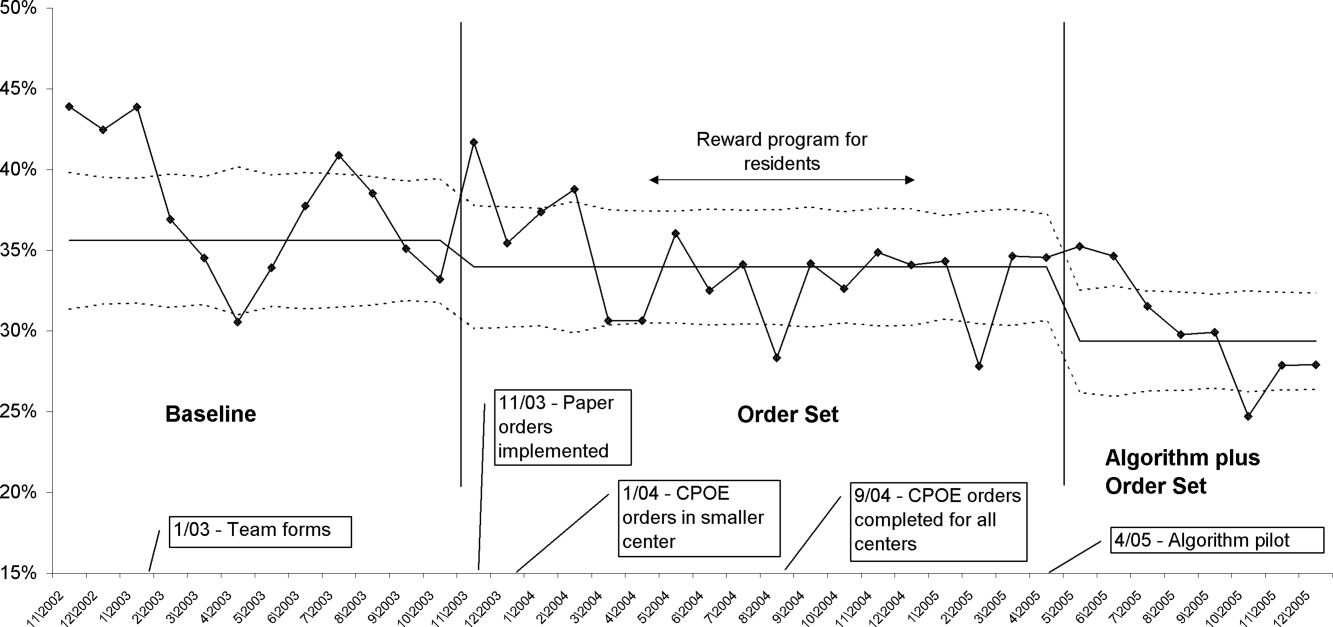

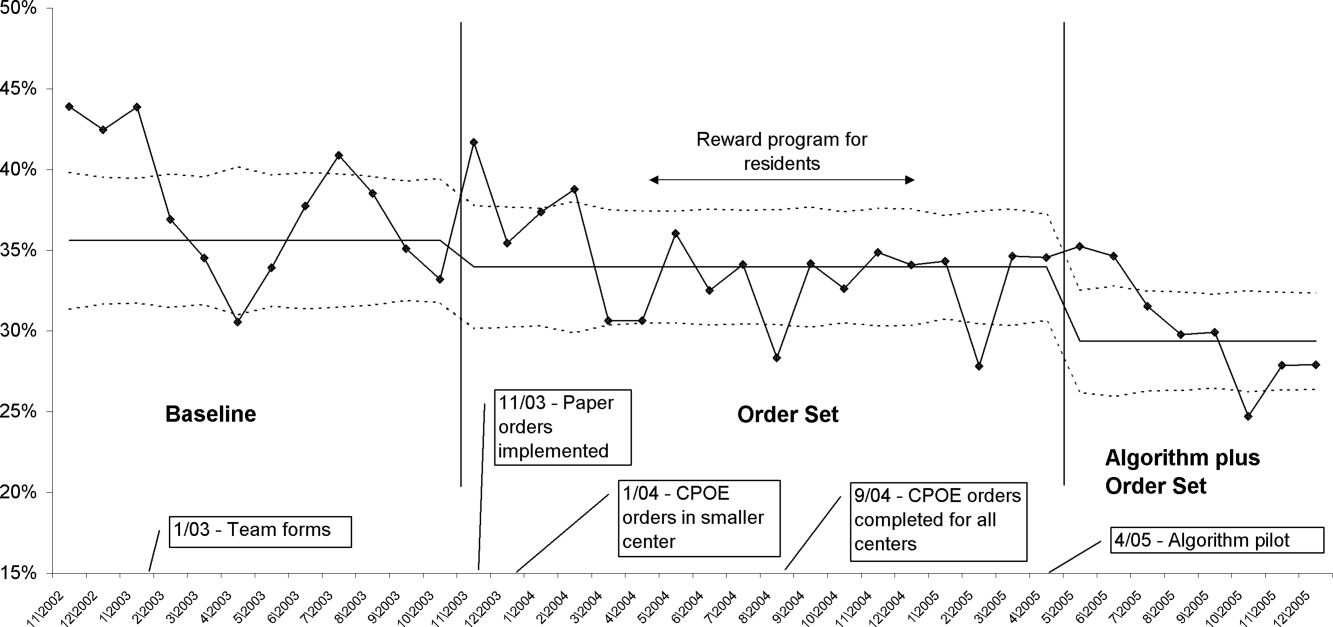

Figure 1 is a timeline of interventions and the impact on the prevalence of adequate VTE prophylaxis. The first 7 to 8 months represent the baseline rate 50% to 55% of VTE prophylaxis. In this baseline period, the improvement team was meeting, but had not yet begun meeting with the large variety of medical and surgical service leaders. Consensus‐building sessions with these leaders in the latter part of 2005 through mid‐2006 correlated with improvement in adequate VTE prophylaxis rates to near 70%. The consensus‐building sessions also prepared these varied services for a go live date of the modular order set that was incorporated into all admit and transfer order sets, often replacing preexisting orders referring to VTE prevention measures. The order set resulted in an improvement to 80% adequate prophylaxis, with the incremental improvement occurring virtually overnight with the go live date at the onset of quarter 2 (Q2) of 2006. Monitoring of the order set use confirmed that it was easy and efficient to use, but also revealed that physicians were at times classifying patients as low VTE risk inaccurately, when they possessed qualities that actually qualified them for moderate risk status by our protocol. We therefore inserted a secondary CPOE screen when patients were categorized as low VTE risk, asking the physician to deny or confirm that the patient had no risk factors that qualified them for moderate risk status. This confirmation screen essentially acted as a reminder to the physician to ask Are you sure this patient does not need VTE prophylaxis? This minor modification of the CPOE order set improved adequate VTE prophylaxis rates to 90%. Finally, we asked nurses to evaluate patients who were not on therapeutic or prophylactic doses of anticoagulants. Patients with VTE risk factors but no obvious contraindications generated a note from the nurse to the doctor, prompting the doctor to reassess VTE risk and potential contraindications. This simple intervention raised the percent of audited patients on adequate VTE prophylaxis to 98% in the last 6 months of 2007.

Description of Prospectively Identified VTE

We identified 748 cases of VTE among patients admitted to the medical center over the 36‐month study period; 387 (52%) were community‐acquired VTE. There were 361 HA cases (48% of total cases) over the same time period. There was no difference in age, gender, or BMI between the community‐acquired and hospital‐related VTE.

Of the 361 HA cases, 199 (55%) occurred on Surgical Services and 162 (45%) occurred on Medical Services; 58 (16%) unique patients had pulmonary emboli, while 303 (84%) patients experienced only DVT. Remarkably, almost one‐third of the DVT occurred in the upper extremities (108 upper extremities, 240 lower extremities), and most (80%) of the upper‐extremity DVT were associated with central venous catheters.

Of 361 HA VTE cases, 292 (81%) occurred in those in the moderate VTE risk category, 69 HA VTE cases occurred in high‐risk category patients (19%), and no VTE occurred in patients in the low‐risk category.

Improvement in HA VTE

HA VTE were identified and each case analyzed on an ongoing basis over the entire 3 year study period, as described above. Table 4 depicts a comparison of HA VTE on a year‐to‐year basis and the impact of the VTE prevention protocol on the incidence of HA VTE. In 2007 (the first full CY after the implementation of the order set) there was a 39% relative risk reduction (RRR) in the risk of experiencing an HA VTE. The reduction in the risk of preventable HA VTE was even more marked (RRR = 86%; 7 preventable VTE in 2007, compared to 44 in baseline year of 2005; RR = 0.14; 95% CI = 0.06‐0.31).

| HA VTE by Year | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | |

| |||

| Patients at Risk | 9720 | 9923 | 11,207 |

| Cases with any HA VTE | 131 | 138 | 92 |

| Risk for HA VTE | 1 in 76 | 1 in 73 | 1 in 122 |

| Unadjusted relative risk (95% CI) | 1.0 | 1.03 (0.81‐1.31) | 0.61* (0.47‐0.79) |

| Cases with PE | 21 | 22 | 15 |

| Risk for PE | 1 in 463 | 1 in 451 | 1 in 747 |

| Unadjusted relative risk (95% CI) | 1.0 | 1.03 (0.56‐1.86) | 0.62 (0.32‐1.20) |

| Cases with DVT (and no PE) | 110 | 116 | 77 |

| Risk for DVT | 1 in 88 | 1 in 85 | 1 in 146 |

| Unadjusted relative risk (95% CI) | 1.0 | 1.03 (0.80‐1.33) | 0.61* (0.45‐0.81) |

| Cases with preventable VTE | 44 | 21 | 7 |

| Risk for preventable VTE | 1 in 221 | 1 in 473 | 1 in 1601 |

| Unadjusted relative risk (95% CI) | 1.0 | 0.47 (0.28‐0.79) | 0.14* (0.06‐0.31) |

Retrospective Analysis of Impact on HIT and Bleeding

There were no statistically significant differences in the number of cases coded for an anticoagulant‐related bleed or secondary thrombocytopenia (Table 5). Chart review revealed there were 2 cases of minor bleeding attributable to pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis before the order set implementation. There were no cases after implementation. No cases of HIT attributable to pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis were identified in either study period, with all cases being attributed to therapeutic anticoagulation.

| Pre‐order Set | Post‐order Set | Post‐order Set RR (CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Bleeding events | 74 | 28 | 0.70 (0.46‐1.08) |

| Due to prophylaxis | 2 (minor) | 0 | |

| HIT events | 9 | 7 | 1.44 (0.54‐3.85) |

| Due to prophylaxis | 0 | 0 | |

| Patient admissions | 32117 | 17294 | |

Discussion

We demonstrated that implementation of a standardized VTE prevention protocol and order set could result in a dramatic and sustained increase in adequate VTE prophylaxis across an entire adult inpatient population. This achievement is more remarkable given the rigorous criteria defining adequate prophylaxis. Mechanical compression devices were not accepted as primary prophylaxis in moderate‐risk or high‐risk patients unless there was a documented contraindication to pharmacologic prophylaxis, and high VTE risk patients required both mechanical and pharmacologic prophylaxis to be considered adequately protected, for example. The relegation of mechanical prophylaxis to an ancillary role was endorsed by our direct observations, in that we were only able to verify that ordered mechanical prophylaxis was in place 60% of the time.

The passive dissemination of guidelines is ineffective in securing VTE prophylaxis.19 Improvement in VTE prophylaxis has been suboptimal when options for VTE prophylaxis are offered without providing guidance for VTE risk stratification and all options (pharmacologic, mechanical, or no prophylaxis) are presented as equally acceptable choices.20, 21 Our multifaceted strategy using multiple interventions is an approach endorsed by a recent systematic review19 and others in the literature.22, 23 The interventions we enacted included a method to prompt clinicians to assess patients for VTE risk, and then to assist in the selection of appropriate prophylaxis from standardized options. Decision support and clinical reminders have been shown to be more effective when integrated into the workflow19, 24; therefore, a key strategy of our study involved embedding the VTE risk assessment tool and guidance toward appropriate prophylactic regimens into commonly used admission/transfer order sets. We addressed the barriers of physician unfamiliarity or disagreement with guidelines10 with education and consensus‐building sessions with clinical leadership. Clinical feedback from audits, peer review, and nursing‐led interventions rounded out the layered multifaceted interventional approach.

We designed and prospectively validated a VTE RAM during the course of our improvement efforts, and to our knowledge our simple 3‐category (or 3‐level) VTE risk assessment model is the only validated model. The VTE risk assessment/prevention protocol was validated by several important parameters. First, it proved to be practical and easy to use, taking only seconds to complete, and it was readily adopted by all adult medical and surgical services. Second, the VTE RAM demonstrated excellent interobserver agreement for VTE risk level and decisions about adequacy of VTE prophylaxis with 5 physician reviewers. Third, the VTE RAM predicted risk for VTE. All patients suffering from HA VTE were in the moderate‐risk to high‐risk categories, and HA VTE occurred disproportionately in those meeting criteria for high risk. Fourth, implementation of the VTE RAM/protocol resulted in very high, sustained levels of VTE prophylaxis without any detectable safety concerns. Finally and perhaps most importantly, high rates of adherence to the VTE protocol resulted in a 40% decline in the incidence of HA VTE in our institution.

The improved prevalence of adequate VTE prophylaxis reduced, but did not eliminate, HA VTE. The reduction observed is consistent with the 40% to 50% efficacy of prophylaxis reported in the literature.7 Our experience highlights the recent controversy over proposals by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) to add HA VTE to the list of do not pay conditions later this year,25 as it is clear from our data that even near‐perfect adherence with accepted VTE prevention measures will not eliminate HA VTE. After vigorous pushback about the fairness of this measure, the HA VTE do not pay scope was narrowed to include only certain major orthopedic procedure patients.

Services with a preponderance of moderate‐risk patients had the largest reduction in HA VTE. Efforts that are focused only on high‐risk orthopedic, trauma, and critical care patients will miss the larger opportunities for maximal reduction in HA VTE for multiple reasons. First, moderate VTE risk patients are far more prevalent than high VTE risk patients (84% vs. 12% of inpatients at our institution). Second, high‐risk patients are already at a baseline relatively high rate of VTE prophylaxis compared to their moderate VTE risk counterparts (83% vs. 53% at our institution). Third, a large portion of patients at high risk for VTE (such as trauma patients) also have the largest prevalence of absolute or relative contraindications to pharmacologic prophylaxis, limiting the effect size of prevention efforts.

Major strengths of this study included ongoing rigorous concurrent measurement of both processes (percent of patients on adequate prophylaxis) and outcomes (HA VTE diagnosed via imaging studies) over a prolonged time period. The robust random sampling of inpatients insured that changes in VTE prophylaxis rates were not due to changes in the distribution of VTE risk or bias potentially introduced from convenience samples. The longitudinal monitoring of imaging study results for VTE cases is vastly superior to using administrative data that is reliant on coding. The recent University Healthsystem Consortium (UHC) benchmarking data on venous thromboembolism were sobering but instructive.26 UHC used administrative discharge codes for VTE in a secondary position to identify patients with HA VTE, which is a common strategy to follow the incidence of HA VTE. The accuracy of identifying surgical patients with an HA VTE was only 60%. Proper use of the present on admission (POA) designation would have improved this to 83%, but 17% of cases either did not occur or had history only with a labor‐intensive manual chart review. Performance was even worse in medical patients, with only a 30% accuracy rate, potentially improved to 79% if accurate POA designation had been used, and 21% of cases identified by administrative methods either did not occur or had history only. In essence, unless an improvement team uses chart review of each case potentially identified as a HA VTE case, the administrative data are not reliable. Concurrent discovery of VTE cases allows for a more accurate and timely chart review, and allows for near real‐time feedback to the responsible treatment team.

The major limitation of this study is inherent in the observational design and the lack of a control population. Other factors besides our VTE‐specific improvement efforts could affect process and outcomes, and reductions in HA VTE could conceivably occur because of changes in the make‐up of the admitted inpatient population. These limitations are mitigated to some degree by several observations. The VTE risk distribution in the randomly sampled inpatient population did not vary significantly from year to year. The number of HA VTE was reduced in 2007 even though the number of patients and patient days at risk for developing VTE went up. The incidence of community‐acquired VTE remained constant over the same time period, highlighting the consistency of our measurement techniques and the VTE risk in the community we serve. Last, the improvements in VTE prophylaxis rates increased at times that correlated well with the introduction of layered interventions, as depicted in Figure 1.

There were several limitations to the internal study on adverse effects of VTE protocol implementation. First, this was a retrospective study, so much of the data collection was dependent upon physician progress notes and discharge summaries. Lack of documentation could have precluded the appropriate diagnosis codes from being assigned. Next, the study population was generated from coding data, so subjectivity could have been introduced during the coding process. Also, a majority of the patients did not fit the study criteria due to discharge with the e934.2 code, because they were found to have an elevated international normalized ratio (INR) after being admitted on warfarin. Finally, chart‐reviewer bias could have affected the results, as the chart reviewer became more proficient at reviewing charts over time. Despite these limitations, the study methodology allowed for screening of a large population for rare events. Bleeding may be a frequent concern with primary thromboprophylaxis, but data from clinical trials and this study help to demonstrate that rates of adverse events from pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis are very rare.

Another potential limitation is raised by the question of whether our methods can be generalized to other sites. Our site is an academic medical center and we have CPOE, which is present in only a small minority of centers. Furthermore, one could question how feasible it is to get institution‐wide consensus for a VTE prevention protocol in settings with heterogenous medical staffs. To address these issues, we used a proven performance improvement framework calling for administrative support, a multidisciplinary improvement team, reliable measures, and a multifaceted approach to interventions. This framework and our experiences have been incorporated into improvement guides27, 28 that have been the centerpiece of the Society of Hospital Medicine VTE Prevention Collaborative improvement efforts in a wide variety of medical environments. The collaborative leadership has observed that success is the rule when this model is followed, in institutions large and small, academic or community, and in both paper and CPOE environments. Not all of these sites use a VTE RAM identical to ours, and there are local nuances to preferred choices of prophylaxis. However, they all incorporated simple VTE risk stratification with only a few levels of risk. Reinforcing the expectation that pharmacologic prophylaxis is indicated for the majority of inpatients is likely more important than the nuances of choices for each risk level.

We demonstrated that dramatic improvement in VTE prophylaxis is achievable, safe, and effective in reducing the incidence of HA VTE. We used scalable, portable methods to make a large and convincing impact on the incidence of HA VTE, while also developing and prospectively validating a VTE RAM. A wide variety of institutions are achieving significant improvement using similar strategies. Future research and improvement efforts should focus on how to accelerate integration of this model across networks of hospitals, leveraging networks with common order sets or information systems. Widespread success in improving VTE prophylaxis would likely have a far‐reaching benefit on morbidity and PE‐related mortality.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Surgeon General's Call to Action to Prevent Deep Vein Thrombosis and Pulmonary Embolism.2008 Clean-up Rule No. CU01 invoked here. . Available at: http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/topics/deepvein. Accessed June 2009.

- ,,, et al.Incidence of venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients vs. community residents.Mayo Clin Proc.2001;76:1102–1110.

- ,,,,.Meta‐analysis: anticoagulant prophylaxis to prevent symptomatic venous thromboembolism in hospitalized medical patients.Ann Intern Med.2007;146(4):278–288.

- ,,, et al.Relative impact of risk factors for deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism.Arch Intern Med.2002;162:1245–1248.

- ,,, et al.Antithrombotic therapy practices in US hospitals in an era of practice guidelines.Arch Intern Med.2005;165:1458–1464.

- ,,, et al.Prevention of venous thromboembolism.Chest.1995;108:312–334.

- ,,, et al.Prevention of venous thromboembolism: ACCP Evidence‐Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th Edition).Chest.2008;133(6 Suppl):381S–453S.

- ,.A prospective registry of 5,451 patients with ultrasound‐confirmed deep vein thrombosis.Am J Cardiol.2004;93:259–262.

- ,,, et al.The outcome after treatment of venous thromboembolism is different in surgical and acutely ill medical patients. Findings from the RIETE registry.J Thromb Haemost.2004;2:1892–1898.

- ,,, et al.Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in acutely ill hospitalized medical patients: findings from the international medical prevention registry on venous thromboembolism.Chest.2007;132(3):936–945.

- ,,, et al.Multicenter evaluation of the use of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in acutely ill medical patients in Canada.Thromb Res.2007;119(2):145–155.

- ,,, et al.Venous thromboembolism risk and prophylaxis in the acute hospital care setting (ENDORSE study): a multinational cross‐sectional study.Lancet.2008;371(9610):387–394.

- ,,.Compliance with recommended prophylaxis for venous thromboembolism: improving the use and rate of uptake of clinical practice guidelines.J Thromb Haemost.2004;2:221–227.

- ,.Risk factors for venous thromboembolism.Circulation.2003;107:I‐9–I‐16.

- ,,.Effective risk stratification of surgical and nonsurgical patients for venous thromboembolic disease.Semin Hematol.2001;38(2 suppl 5):12–19.

- ,,,,.Identification of candidates for prevention of venous thromboembolism.Semin Thromb Hemost.1997;23(1):55–67.

- .Venous thromboembolic risk and its prevention in hospitalized medical patients.Semin Thromb Hemost.2002;28(6);577–583.

- ,,, et al.A guide to venous thromboembolism risk factor assessment.J Thromb Thrombolysis.2000;9:253–262.

- ,,, et al.A systematic review of strategies to improve prophylaxis for venous thromboembolism in hospitals.Ann Surg.2005;241:397–415.

- ,,,.Medical admission order sets to improve deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis rates and other outcomes.J Hosp Med.2009;4(2):81–89.

- .Medical admission order sets to improve deep vein thrombosis prevention: a model for others or a prescription for mediocrity? [Editorial].J Hosp Med.2009;4(2):77–80.

- ,,,.No magic bullets: a systematic review of 102 trials of interventions to improve professional practice.CMAJ.1995;153:1423–1431.

- ,,.Innovative approaches to increase deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis rate resulting in a decrease in hospital‐acquired deep vein thrombosis at a tertiary‐care teaching hospital.J Hosp Med.2008;3(2):148–155.

- ,,,.Closing the Quality Gap: A Critical Analysis of Quality Improvement Strategies.Rockville, MD:Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality;2004.

- CMS Office of Public Affairs. Fact Sheet: CMS Proposes Additions to List of Hospital‐Acquired Conditions for Fiscal Year 2009. Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/apps/media/press/factsheet.asp?Counter=3042. Accessed June2009.

- The DVT/PE 2007 Knowledge Transfer Meeting. Proceedings of November 30, 2007 meeting. Available at: http://www.uhc.edu/21801.htm. Accessed June2009.

- ,. Preventing Hospital‐Acquired Venous Thromboembolism. A Guide for Effective Quality Improvement. Society of Hospital Medicine, VTE Quality Improvement Resource Room. Available at: http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/ResourceRoomRedesign/RR_VTE/VTE_Home.cfm. Accessed June 2009.

- ,.Preventing Hospital‐Acquired Venous Thromboembolism: A Guide for Effective Quality Improvement. Prepared by the Society of Hospital Medicine. AHRQ Publication No. 08–0075.Rockville, MD:Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. September2008. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/qual/vtguide. Accessed June 2009.

Pulmonary embolism (PE) and deep vein thrombosis (DVT), collectively referred to as venous thromboembolism (VTE), represent a major public health problem, affecting hundreds of thousands of Americans each year.1 The best estimates are that at least 100,000 deaths are attributable to VTE each year in the United States alone.1 VTE is primarily a problem of hospitalized and recently‐hospitalized patients.2 Although a recent meta‐analysis did not prove mortality benefit of prophylaxis in the medical population,3 PE is frequently estimated to be the most common preventable cause of hospital death.46

Pharmacologic methods to prevent VTE are safe, effective, cost‐effective, and advocated by authoritative guidelines.7 Even though the majority of medical and surgical inpatients have multiple risk factors for VTE, large prospective studies continue to demonstrate that these preventive methods are significantly underutilized, often with only 30% to 50% eligible patients receiving prophylaxis.812

The reasons for this underutilization include lack of physician familiarity or agreement with guidelines, underestimation of VTE risk, concern over risk of bleeding, and the perception that the guidelines are resource‐intensive or difficult to implement in a practical fashion.13 While many VTE risk‐assessment models are available in the literature,1418 a lack of prospectively validated models and issues regarding ease of use have further hampered widespread integration of VTE risk assessments into order sets and inpatient practice.

We sought to optimize prevention of hospital‐acquired (HA) VTE in our 350‐bed tertiary‐care academic center using a VTE prevention protocol and a multifaceted approach that could be replicated across a wide variety of medical centers.

Patients and Methods

Study Design

We developed, implemented, and refined a VTE prevention protocol and examined the impact of our efforts. We observed adult inpatients on a longitudinal basis for the prevalence of adequate VTE prophylaxis and for the incidence of HA VTE throughout a 36‐month period from calendar year 2005 through 2007, and performed a retrospective analysis for any potential adverse effects of increased VTE prophylaxis. The project adhered to the HIPAA requirements for privacy involving health‐related data from human research participants. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of California, San Diego, which waived the requirement for individual patient informed consent.

We included all hospitalized adult patients (medical and surgical services) at our medical center in our observations and interventions, including patients of all ethnic groups, geriatric patients, prisoners, and the socially and economically disadvantaged in our population. Exclusion criteria were age under 14 years, and hospitalization on Psychiatry or Obstetrics/Gynecology services.

Development of a VTE Risk‐assessment Model and VTE Prevention Protocol

A core multidisciplinary team with hospitalists, pulmonary critical care VTE experts, pharmacists, nurses, and information specialists was formed. After gaining administrative support for standardization, we worked with medical staff leaders to gain consensus on a VTE prevention protocol for all medical and surgical areas from mid‐2005 through mid‐2006. The VTE prevention protocol included the elements of VTE risk stratification, definitions of adequate VTE prevention measures linked to the level of VTE risk, and definitions for contraindications to pharmacologic prophylactic measures. We piloted risk‐assessment model (RAM) drafts for ease of use and clarity, using rapid cycle feedback from pharmacy residents, house staff, and medical staff attending physicians. Models often cited in the literature15, 18 that include point‐based scoring of VTE risk factors (with prophylaxis choices hinging on the additive sum of scoring) were rejected based on the pilot experience.

We adopted a simple model with 3 levels of VTE risk that could be completed by the physician in seconds, and then proceeded to integrate this RAM into standardized data collection instruments and eventually (April 2006) into a computerized provider order entry (CPOE) order set (Siemmens Invision v26). Each level of VTE risk was firmly linked to a menu of acceptable prophylaxis options (Table 1). Simple text cues were used to define risk assessment, with more exhaustive listings of risk factors being relegated to accessible reference tables.

| Low | Moderate | High |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Ambulatory patient without VTE risk factors; observation patient with expected LOS 2 days; same day surgery or minor surgery | All other patients (not in low‐risk or high‐risk category); most medical/surgical patients; respiratory insufficiency, heart failure, acute infectious, or inflammatory disease | Lower extremity arthroplasty; hip, pelvic, or severe lower extremity fractures; acute SCI with paresis; multiple major trauma; abdominal or pelvic surgery for cancer |

| Early ambulation | UFH 5000 units SC q 8 hours; OR LMWH q day; OR UFH 5000 units SC q 12 hours (if weight < 50 kg or age > 75 years); AND suggest adding IPC | LMWH (UFH if ESRD); OR fondaparinux 2.5 mg SC daily; OR warfarin, INR 2‐3; AND IPC (unless not feasible) |

Intermittent pneumatic compression devices were endorsed as an adjunct in all patients in the highest risk level, and as the primary method in patients with contraindications to pharmacologic prophylaxis. Aspirin was deemed an inappropriate choice for VTE prophylaxis. Subcutaneous unfractionated or low‐molecular‐weight heparin were endorsed as the primary method of prophylaxis for the majority of patients without contraindications.

Integration of the VTE Protocol into Order Sets

An essential strategy for the success of the VTE protocol included integrating guidance for the physician into the flow of patient care, via standardized order sets. The CPOE VTE prevention order set was modular by design, as opposed to a stand alone design. After conferring with appropriate stakeholders, preexisting and nonstandardized prompts for VTE prophylaxis were removed from commonly used order sets, and the standardized module was inserted in its place. This allowed for integration of the standardized VTE prevention module into all admission and transfer order sets, essentially insuring that all patients admitted or transferred within the medical center would be exposed to the protocol. Physicians using a variety of admission and transfer order sets were prompted to select each patient's risk for VTE, and declare the presence or absence of contraindications to pharmacologic prophylaxis. Only the VTE prevention options most appropriate for the patient's VTE and anticoagulation risk profile were presented as the default choice for VTE prophylaxis. Explicit designation of VTE risk level and a prophylaxis choice were presented in a hard stop mechanism, and utilization of these orders was therefore mandatory, not optional. Proper use (such as the proper classification of VTE risk by the ordering physician) was actively monitored on an auditing basis, and order sets were modified occasionally on the basis of subjective and objective feedback.

Assessment of VTE Risk Assessment Interobserver Agreement

Data from 150 randomly selected patients from the audit pool (from late 2005 through mid‐2006) were abstracted by the nurse practitioner in a detailed manner. Five independent reviewers assessed each patient for VTE risk level, and for a determination of whether or not they were on adequate VTE prophylaxis on the day of the audit per protocol. Interobserver agreement was calculated for these parameters using kappa scores.

Prospective Monitoring of Adequate VTE Prophylaxis

A daily medical center inpatient census report of eligible patients in the medical center for >48 hours was downloaded into an Microsoft Excel spreadsheet, with each patient assigned a consecutive number. The Excel random number generator plug‐in function was used to generate a randomly sequenced list of the patients. The research nurse practitioner targeted serial patients on the list for further study, until she accomplished the requisite number of audits each day. The mean number of audits per month declined over the study years as the trends stabilized and as grant funding expired, but remained robust throughout (2005: 107 audits per month; 2006: 80 audits per month; and 2007: 57 audits per month).

The data collected on each patient randomly selected for audit included age, gender, location, service, date and time of review, and date of admission. The audit VTE RAM (identical to the VTE RAM incorporated into the order set), was used to classify each patient's VTE risk as low, moderate, or high. For each audit, we determined if the patient was on an adequate VTE prevention regimen consistent with our protocol, given their VTE risk level, demographics, and absence or presence of contraindications to pharmacologic prophylaxis. All questionable cases were reviewed by at least 2 physicians at weekly meetings with a final consensus determination. Adequacy of the VTE regimen was judged by orders entered on the day of the audit, but we also noted whether or not ordered intermittent compression devices were in place and functioning at the time of the audit.

Prospective (Concurrent) Discovery and Analysis of VTE Cases

The team nurse practitioner used the PACS radiology reporting and archival system (IMPAX version 4.5; AGFA Healthcare Informatics, Greenville, SC) to identify all new diagnoses of VTE, in the process described below.

Procedure codes for following studies were entered into the IMPAX search engine to locate all such exams performed in the previous 1 to 3 days:

Ultrasound exams of the neck, upper extremities, and lower extremities;

Computed tomography (CT) angiograms of the chest;

Ventilation/perfusion nuclear medicine scans; and

Pulmonary angiograms.

Negative studies and studies that revealed unchanged chronic thromboses were excluded, while clots with a chronic appearance but no evidence of prior diagnosis were included. Iliofemoral, popliteal, calf vein, subclavian, internal and external jugular vein, and axillary vein thromboses were therefore included, as were all PEs. Less common locations, such as renal vein and cavernous sinus thromboses, were excluded. The improvement/research team exerted no influence over decisions about whether or not testing was done.

Each new case of VTE was then classified as HA VTE or community‐acquired VTE. A new VTE was classified as HA if the diagnosis was first suspected and made in the hospital. A newly diagnosed VTE was also classified as HA if the VTE was suspected in the ambulatory setting, but the patient had been hospitalized within the arbitrary window of the preceding 30 days.

Each new diagnosis of HA VTE was reviewed by core members of the multidisciplinary support team. This investigation included a determination of whether the patient was on an adequate VTE prophylaxis regimen at the time of the HA VTE, using the RAM and linked prophylaxis menu described above. The VTE prevention regimen ordered at the time the inpatient developed the HA VTE was classified as adherent or nonadherent to the University of California, San Diego (UCSD) protocol: patients who developed VTE when on suboptimal prophylaxis per protocol were classified as having a potentially preventable case. Potentially iatrogenic precipitants of VTE (such as the presence of a central venous catheter or restraints) were also noted. All data were entered into a Microsoft Access database for ease of retrieval and reporting.

All tests for VTE were performed based on clinical signs and symptoms, rather than routine screening, except for the Trauma and Burn services, which also screen for VTE in high‐risk patients per their established screening protocols.

Statistical Analysis of VTE Prophylaxis and HA VTE Cases

Gender differences between cases of VTE and randomly sampled and audited inpatients were examined by chi‐square analysis, and analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to examine any age or body mass index (BMI) differences between audits and cases.

The unadjusted risk ratio (RR) for adequate prophylaxis was compared by year, with year 2005 being the baseline (comparison) year, by chi‐square analysis.

The unadjusted RR of HA VTE was calculated by dividing the number of cases found in the calendar year by the hospital census of adult inpatients at risk. For each case, a classification for the type of VTE (PE vs. DVT vs. combinations) was recorded. Cases not receiving adequate prophylaxis were categorized as preventable DVT. Unadjusted RRs were calculated for each year by chi‐square analysis, compared to the baseline (2005) year.

All data were analyzed using Stata (version 10; Stata Corp., College Station, TX). Results for the different analysis were considered significant at P < 0.05.

Retrospective Study of Unintentional Adverse Effects

The increase in anticoagulant use accompanying the introduction of the VTE prophylaxis order set warranted an evaluation of any subsequent rise in related adverse events. A study was done to determine the rates of bleeding and heparin‐induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) before and after the implementation of the VTE prophylaxis order set.

A retrospective analysis was conducted to evaluate outcomes in our inpatients from December 2004 through November 2006, with April to November, 2006 representing the post‐order set implementation time period. Any patient with a discharge diagnosis code of e934.2 (anticoagulant‐related adverse event) was selected for study to identify possible bleeding attributable to pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis. Major or minor bleeding attributable to pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis was defined as a bleed occurring 72 hours after receiving pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis. Major bleeding was defined as cerebrovascular, gastrointestinal, retroperitoneal, or overt bleeding with a decrease in hemoglobin 2 mg/dL with clinical symptoms such as hypotension or hypoxia (not associated with hemodialysis) or transfusion of 2 units of packed red blood cells. Minor bleeding was defined as ecchymosis, epistaxis, hematoma, hematuria, hemoptysis, petechiae, or bleeding without a decrease in hemoglobin 2 g/dL.

Possible cases of HIT were identified by screening for a concomitant secondary thrombocytopenia code (287.4). Chart review was then conducted to determine a causal relationship between the use of pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis and adverse events during the hospital stay. HIT attributable to pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis was determined by assessing if patients developed any of the following clinical criteria after receiving pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis: platelet count <150 109/L or 50% decrease from baseline, with or without an associated venous or arterial thrombosis or other sequelae (skin lesions at injection site, acute systemic reaction) and/or a positive heparin‐induced platelet activation (HIPA) test. In order to receive a diagnosis of HIT, thrombocytopenia must have occurred between days 5 to 15 of heparin therapy, unless existing evidence suggested that the patient developed rapid‐onset HIT or delayed‐onset HIT. Rapid‐onset HIT was defined as an abrupt drop in platelet count upon receiving a heparin product, due to heparin exposure within the previous 100 days. Delayed‐onset HIT was defined as HIT that developed several days after discontinuation of heparin. Other evident causes of thrombocytopenia were ruled out.

Statistical Analysis of Retrospective Study of Unintentional Adverse Effects

Regression analysis with chi‐square and ANOVA were used in the analysis of the demographic data. RRs were calculated for the number of cases coded with an anticoagulant‐related adverse event secondary thrombocytopenia before and after the order set implementation.

Educational Efforts and Feedback

Members of the multidisciplinary team presented information on HA VTE and the VTE prevention protocol at Medical and Surgical grand rounds, teaching rounds, and noon conference, averaging 1 educational session per quarter. Feedback and education was provided to physicians and nursing staff when audits revealed that a patient had inadequate prophylaxis with reference to the protocol standard. In addition, these conversations provided on opportunity to explore reasons for nonadherence with the protocol, confusion regarding the VTE RAM, and other barriers to effective prophylaxis, thereby providing guidance for further protocol revision and educational efforts. We adjusted the order set based on active monitoring of order set use and the audit process.

Results

There were 30,850 adult medical/surgical inpatients admitted to the medical center with a length of stay of 48 hours or more in 2005 to 2007, representing 186,397 patient‐days of observation. A total of 2,924 of these patients were randomly sampled during the VTE prophylaxis audit process (mean 81 audits per month). Table 2 shows the characteristics of randomly sampled audit patients and of the patients diagnosed with HA VTE. The demographics of the 30,850‐inpatient population (mean age = 50 years; 60.7% male; 52% Surgical Services) mirrored the demographics of the randomly sampled inpatients that underwent audits, validating the random sampling methods.

| Number (n = 3285) | % of Study Population* | Cases (n = 361) [n (%)] | Audits (n = 2924) [n (%)] | OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Age (years) mean SD | 51 16 (range 15‐100) | 53 17 | 50 17 | 1.01 (1.003‐1.016) | |

| Gender, males | 1993 | 61 | 213 (59) | 1782 (61) | 0.93 (0.744‐1.16) |

| Major service: | |||||

| Surgery | 1714 | 52 | 200 (55) | 1516 (52) | |

| Medicine | 1566 | 48 | 161 (45) | 1408 (48) | |

| Service, detail | |||||

| Hospitalist | 1041 | 32 | 83 (23) | 958 (33) | |

| General surgery | 831 | 25 | 75 (21) | 756 (26) | |

| Trauma | 419 | 13 | 77 (22) | 342 (12) | |

| Cardiology | 313 | 10 | 45 (13) | 268 (9) | |

| Orthopedics | 244 | 7 | 15 (4) | 229 (8) | |

| Burn unit | 205 | 6 | 29 (8) | 176 (6) | |

| Other | 222 | 7 | 30 (8) | 192 (7) | |

The majority of inpatients sampled in the audits were in the moderate VTE risk category (84%), 12% were in the high‐risk category, and 4% were in the low‐risk category. The distribution of VTE risk did not change significantly over this time period.

Interobserver Agreement

The VTE RAM interobserver agreement was assessed on 150 patients with 5 observers as described above. The kappa score for the VTE risk level was 0.81. The kappa score for the judgment of whether the patient was on adequate prophylaxis or not was 0.90.

Impact on Percent of Patients with Adequate Prophylaxis (Longitudinal Audits)

Audits of randomly sampled inpatients occurred longitudinally throughout the study period as described above. Based on the intervention, the percent of patients on adequate prophylaxis improved significantly (P < 0.001) by each calendar year (see Table 3), from a baseline of 58% in 2005 to 78% in 2006 (unadjusted relative benefit = 1.35; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.28‐1.43), and 93% in 2007 (unadjusted relative benefit = 1.61; 95% CI = 1.52, 1.69). The improvement seen was more marked in the moderate VTE risk patients when compared to the high VTE risk patients. The percent of audited VTE prophylaxis improved from 53% in calendar year (CY) 2005 to 93% in 2007 (unadjusted relative benefit = 1.75; 95% CI = 1.70‐1.81) in the moderate VTE risk group, while the high VTE risk group improved from 83% to 92% in the same time period (unadjusted relative benefit = 1.11; 95% CI = 0.95‐1.25).

| 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| All audits | 1279 | 960 | 679 |

| Prophylaxis adequate, n (%) | 740 (58) | 751 (78) | 631 (93) |

| Relative benefit (95% CI) | 1 | 1.35* (1.28‐1.43) | 1.61* (1.52‐1.69) |

Overall, adequate VTE prophylaxis was present in over 98% of audited patients in the last 6 months of 2007, and this high rate has been sustained throughout 2008. Age, ethnicity, and gender were not associated with differential rates of adequate VTE prophylaxis.

Figure 1 is a timeline of interventions and the impact on the prevalence of adequate VTE prophylaxis. The first 7 to 8 months represent the baseline rate 50% to 55% of VTE prophylaxis. In this baseline period, the improvement team was meeting, but had not yet begun meeting with the large variety of medical and surgical service leaders. Consensus‐building sessions with these leaders in the latter part of 2005 through mid‐2006 correlated with improvement in adequate VTE prophylaxis rates to near 70%. The consensus‐building sessions also prepared these varied services for a go live date of the modular order set that was incorporated into all admit and transfer order sets, often replacing preexisting orders referring to VTE prevention measures. The order set resulted in an improvement to 80% adequate prophylaxis, with the incremental improvement occurring virtually overnight with the go live date at the onset of quarter 2 (Q2) of 2006. Monitoring of the order set use confirmed that it was easy and efficient to use, but also revealed that physicians were at times classifying patients as low VTE risk inaccurately, when they possessed qualities that actually qualified them for moderate risk status by our protocol. We therefore inserted a secondary CPOE screen when patients were categorized as low VTE risk, asking the physician to deny or confirm that the patient had no risk factors that qualified them for moderate risk status. This confirmation screen essentially acted as a reminder to the physician to ask Are you sure this patient does not need VTE prophylaxis? This minor modification of the CPOE order set improved adequate VTE prophylaxis rates to 90%. Finally, we asked nurses to evaluate patients who were not on therapeutic or prophylactic doses of anticoagulants. Patients with VTE risk factors but no obvious contraindications generated a note from the nurse to the doctor, prompting the doctor to reassess VTE risk and potential contraindications. This simple intervention raised the percent of audited patients on adequate VTE prophylaxis to 98% in the last 6 months of 2007.

Description of Prospectively Identified VTE

We identified 748 cases of VTE among patients admitted to the medical center over the 36‐month study period; 387 (52%) were community‐acquired VTE. There were 361 HA cases (48% of total cases) over the same time period. There was no difference in age, gender, or BMI between the community‐acquired and hospital‐related VTE.

Of the 361 HA cases, 199 (55%) occurred on Surgical Services and 162 (45%) occurred on Medical Services; 58 (16%) unique patients had pulmonary emboli, while 303 (84%) patients experienced only DVT. Remarkably, almost one‐third of the DVT occurred in the upper extremities (108 upper extremities, 240 lower extremities), and most (80%) of the upper‐extremity DVT were associated with central venous catheters.

Of 361 HA VTE cases, 292 (81%) occurred in those in the moderate VTE risk category, 69 HA VTE cases occurred in high‐risk category patients (19%), and no VTE occurred in patients in the low‐risk category.

Improvement in HA VTE

HA VTE were identified and each case analyzed on an ongoing basis over the entire 3 year study period, as described above. Table 4 depicts a comparison of HA VTE on a year‐to‐year basis and the impact of the VTE prevention protocol on the incidence of HA VTE. In 2007 (the first full CY after the implementation of the order set) there was a 39% relative risk reduction (RRR) in the risk of experiencing an HA VTE. The reduction in the risk of preventable HA VTE was even more marked (RRR = 86%; 7 preventable VTE in 2007, compared to 44 in baseline year of 2005; RR = 0.14; 95% CI = 0.06‐0.31).

| HA VTE by Year | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | |

| |||

| Patients at Risk | 9720 | 9923 | 11,207 |

| Cases with any HA VTE | 131 | 138 | 92 |

| Risk for HA VTE | 1 in 76 | 1 in 73 | 1 in 122 |

| Unadjusted relative risk (95% CI) | 1.0 | 1.03 (0.81‐1.31) | 0.61* (0.47‐0.79) |

| Cases with PE | 21 | 22 | 15 |

| Risk for PE | 1 in 463 | 1 in 451 | 1 in 747 |

| Unadjusted relative risk (95% CI) | 1.0 | 1.03 (0.56‐1.86) | 0.62 (0.32‐1.20) |

| Cases with DVT (and no PE) | 110 | 116 | 77 |

| Risk for DVT | 1 in 88 | 1 in 85 | 1 in 146 |

| Unadjusted relative risk (95% CI) | 1.0 | 1.03 (0.80‐1.33) | 0.61* (0.45‐0.81) |

| Cases with preventable VTE | 44 | 21 | 7 |

| Risk for preventable VTE | 1 in 221 | 1 in 473 | 1 in 1601 |

| Unadjusted relative risk (95% CI) | 1.0 | 0.47 (0.28‐0.79) | 0.14* (0.06‐0.31) |

Retrospective Analysis of Impact on HIT and Bleeding

There were no statistically significant differences in the number of cases coded for an anticoagulant‐related bleed or secondary thrombocytopenia (Table 5). Chart review revealed there were 2 cases of minor bleeding attributable to pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis before the order set implementation. There were no cases after implementation. No cases of HIT attributable to pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis were identified in either study period, with all cases being attributed to therapeutic anticoagulation.

| Pre‐order Set | Post‐order Set | Post‐order Set RR (CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Bleeding events | 74 | 28 | 0.70 (0.46‐1.08) |

| Due to prophylaxis | 2 (minor) | 0 | |

| HIT events | 9 | 7 | 1.44 (0.54‐3.85) |

| Due to prophylaxis | 0 | 0 | |

| Patient admissions | 32117 | 17294 | |

Discussion

We demonstrated that implementation of a standardized VTE prevention protocol and order set could result in a dramatic and sustained increase in adequate VTE prophylaxis across an entire adult inpatient population. This achievement is more remarkable given the rigorous criteria defining adequate prophylaxis. Mechanical compression devices were not accepted as primary prophylaxis in moderate‐risk or high‐risk patients unless there was a documented contraindication to pharmacologic prophylaxis, and high VTE risk patients required both mechanical and pharmacologic prophylaxis to be considered adequately protected, for example. The relegation of mechanical prophylaxis to an ancillary role was endorsed by our direct observations, in that we were only able to verify that ordered mechanical prophylaxis was in place 60% of the time.

The passive dissemination of guidelines is ineffective in securing VTE prophylaxis.19 Improvement in VTE prophylaxis has been suboptimal when options for VTE prophylaxis are offered without providing guidance for VTE risk stratification and all options (pharmacologic, mechanical, or no prophylaxis) are presented as equally acceptable choices.20, 21 Our multifaceted strategy using multiple interventions is an approach endorsed by a recent systematic review19 and others in the literature.22, 23 The interventions we enacted included a method to prompt clinicians to assess patients for VTE risk, and then to assist in the selection of appropriate prophylaxis from standardized options. Decision support and clinical reminders have been shown to be more effective when integrated into the workflow19, 24; therefore, a key strategy of our study involved embedding the VTE risk assessment tool and guidance toward appropriate prophylactic regimens into commonly used admission/transfer order sets. We addressed the barriers of physician unfamiliarity or disagreement with guidelines10 with education and consensus‐building sessions with clinical leadership. Clinical feedback from audits, peer review, and nursing‐led interventions rounded out the layered multifaceted interventional approach.

We designed and prospectively validated a VTE RAM during the course of our improvement efforts, and to our knowledge our simple 3‐category (or 3‐level) VTE risk assessment model is the only validated model. The VTE risk assessment/prevention protocol was validated by several important parameters. First, it proved to be practical and easy to use, taking only seconds to complete, and it was readily adopted by all adult medical and surgical services. Second, the VTE RAM demonstrated excellent interobserver agreement for VTE risk level and decisions about adequacy of VTE prophylaxis with 5 physician reviewers. Third, the VTE RAM predicted risk for VTE. All patients suffering from HA VTE were in the moderate‐risk to high‐risk categories, and HA VTE occurred disproportionately in those meeting criteria for high risk. Fourth, implementation of the VTE RAM/protocol resulted in very high, sustained levels of VTE prophylaxis without any detectable safety concerns. Finally and perhaps most importantly, high rates of adherence to the VTE protocol resulted in a 40% decline in the incidence of HA VTE in our institution.

The improved prevalence of adequate VTE prophylaxis reduced, but did not eliminate, HA VTE. The reduction observed is consistent with the 40% to 50% efficacy of prophylaxis reported in the literature.7 Our experience highlights the recent controversy over proposals by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) to add HA VTE to the list of do not pay conditions later this year,25 as it is clear from our data that even near‐perfect adherence with accepted VTE prevention measures will not eliminate HA VTE. After vigorous pushback about the fairness of this measure, the HA VTE do not pay scope was narrowed to include only certain major orthopedic procedure patients.

Services with a preponderance of moderate‐risk patients had the largest reduction in HA VTE. Efforts that are focused only on high‐risk orthopedic, trauma, and critical care patients will miss the larger opportunities for maximal reduction in HA VTE for multiple reasons. First, moderate VTE risk patients are far more prevalent than high VTE risk patients (84% vs. 12% of inpatients at our institution). Second, high‐risk patients are already at a baseline relatively high rate of VTE prophylaxis compared to their moderate VTE risk counterparts (83% vs. 53% at our institution). Third, a large portion of patients at high risk for VTE (such as trauma patients) also have the largest prevalence of absolute or relative contraindications to pharmacologic prophylaxis, limiting the effect size of prevention efforts.

Major strengths of this study included ongoing rigorous concurrent measurement of both processes (percent of patients on adequate prophylaxis) and outcomes (HA VTE diagnosed via imaging studies) over a prolonged time period. The robust random sampling of inpatients insured that changes in VTE prophylaxis rates were not due to changes in the distribution of VTE risk or bias potentially introduced from convenience samples. The longitudinal monitoring of imaging study results for VTE cases is vastly superior to using administrative data that is reliant on coding. The recent University Healthsystem Consortium (UHC) benchmarking data on venous thromboembolism were sobering but instructive.26 UHC used administrative discharge codes for VTE in a secondary position to identify patients with HA VTE, which is a common strategy to follow the incidence of HA VTE. The accuracy of identifying surgical patients with an HA VTE was only 60%. Proper use of the present on admission (POA) designation would have improved this to 83%, but 17% of cases either did not occur or had history only with a labor‐intensive manual chart review. Performance was even worse in medical patients, with only a 30% accuracy rate, potentially improved to 79% if accurate POA designation had been used, and 21% of cases identified by administrative methods either did not occur or had history only. In essence, unless an improvement team uses chart review of each case potentially identified as a HA VTE case, the administrative data are not reliable. Concurrent discovery of VTE cases allows for a more accurate and timely chart review, and allows for near real‐time feedback to the responsible treatment team.

The major limitation of this study is inherent in the observational design and the lack of a control population. Other factors besides our VTE‐specific improvement efforts could affect process and outcomes, and reductions in HA VTE could conceivably occur because of changes in the make‐up of the admitted inpatient population. These limitations are mitigated to some degree by several observations. The VTE risk distribution in the randomly sampled inpatient population did not vary significantly from year to year. The number of HA VTE was reduced in 2007 even though the number of patients and patient days at risk for developing VTE went up. The incidence of community‐acquired VTE remained constant over the same time period, highlighting the consistency of our measurement techniques and the VTE risk in the community we serve. Last, the improvements in VTE prophylaxis rates increased at times that correlated well with the introduction of layered interventions, as depicted in Figure 1.

There were several limitations to the internal study on adverse effects of VTE protocol implementation. First, this was a retrospective study, so much of the data collection was dependent upon physician progress notes and discharge summaries. Lack of documentation could have precluded the appropriate diagnosis codes from being assigned. Next, the study population was generated from coding data, so subjectivity could have been introduced during the coding process. Also, a majority of the patients did not fit the study criteria due to discharge with the e934.2 code, because they were found to have an elevated international normalized ratio (INR) after being admitted on warfarin. Finally, chart‐reviewer bias could have affected the results, as the chart reviewer became more proficient at reviewing charts over time. Despite these limitations, the study methodology allowed for screening of a large population for rare events. Bleeding may be a frequent concern with primary thromboprophylaxis, but data from clinical trials and this study help to demonstrate that rates of adverse events from pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis are very rare.

Another potential limitation is raised by the question of whether our methods can be generalized to other sites. Our site is an academic medical center and we have CPOE, which is present in only a small minority of centers. Furthermore, one could question how feasible it is to get institution‐wide consensus for a VTE prevention protocol in settings with heterogenous medical staffs. To address these issues, we used a proven performance improvement framework calling for administrative support, a multidisciplinary improvement team, reliable measures, and a multifaceted approach to interventions. This framework and our experiences have been incorporated into improvement guides27, 28 that have been the centerpiece of the Society of Hospital Medicine VTE Prevention Collaborative improvement efforts in a wide variety of medical environments. The collaborative leadership has observed that success is the rule when this model is followed, in institutions large and small, academic or community, and in both paper and CPOE environments. Not all of these sites use a VTE RAM identical to ours, and there are local nuances to preferred choices of prophylaxis. However, they all incorporated simple VTE risk stratification with only a few levels of risk. Reinforcing the expectation that pharmacologic prophylaxis is indicated for the majority of inpatients is likely more important than the nuances of choices for each risk level.

We demonstrated that dramatic improvement in VTE prophylaxis is achievable, safe, and effective in reducing the incidence of HA VTE. We used scalable, portable methods to make a large and convincing impact on the incidence of HA VTE, while also developing and prospectively validating a VTE RAM. A wide variety of institutions are achieving significant improvement using similar strategies. Future research and improvement efforts should focus on how to accelerate integration of this model across networks of hospitals, leveraging networks with common order sets or information systems. Widespread success in improving VTE prophylaxis would likely have a far‐reaching benefit on morbidity and PE‐related mortality.

Pulmonary embolism (PE) and deep vein thrombosis (DVT), collectively referred to as venous thromboembolism (VTE), represent a major public health problem, affecting hundreds of thousands of Americans each year.1 The best estimates are that at least 100,000 deaths are attributable to VTE each year in the United States alone.1 VTE is primarily a problem of hospitalized and recently‐hospitalized patients.2 Although a recent meta‐analysis did not prove mortality benefit of prophylaxis in the medical population,3 PE is frequently estimated to be the most common preventable cause of hospital death.46

Pharmacologic methods to prevent VTE are safe, effective, cost‐effective, and advocated by authoritative guidelines.7 Even though the majority of medical and surgical inpatients have multiple risk factors for VTE, large prospective studies continue to demonstrate that these preventive methods are significantly underutilized, often with only 30% to 50% eligible patients receiving prophylaxis.812