User login

Gender Distribution in Pediatric Hospital Medicine Leadership

There is a growing appreciation of gender disparities in career advancement in medicine. By 2004, approximately 50% of medical school graduates were women, yet considerable differences persist between genders in compensation, faculty rank, and leadership positions.1-3 According to the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), women account for only 25% of full professors, 18% of department chairs, and 18% of medical school deans.1 Women are also underrepresented in other areas of leadership such as division directors, professional society leadership, and hospital executives.4-6

Specialties that are predominantly women, including pediatrics, are not immune to gender disparities. Women represent 71% of pediatric residents1 and currently constitute two-thirds of active pediatricians in the United States.7 However, there is a disproportionately low number of women ascending the pediatric academic ladder, with only 35% of full professors2 and 28% of department chairs being women.1 Pediatrics also was noted to have the fifth-largest gender pay gap across 40 specialties.3 These disparities can contribute to burnout, poorer patient outcomes, and decreased advancement of women known as the “leaky pipeline.”1,8,9

There is some evidence that gender disparities may be improving among younger professionals with increasing percentages of women as leaders and decreasing pay gaps.10,11 These potential positive trends provide hope that fields in medicine early in their development may demonstrate fewer gender disparities. One of the youngest fields of medicine is pediatric hospital medicine (PHM), which officially became a recognized pediatric subspecialty in 2017.12 There is no literature to date describing gender disparities in PHM. We aimed to explore the gender distribution of university-based PHM program leadership and to compare this gender distribution with that seen in the broader field of PHM.

METHODS

This study was Institutional Review Board–approved as non–human subjects research through University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois. From January to March 2020, the authors performed web-based searches for PHM division directors or program leaders in the United States. Because there is no single database of PHM programs in the United States, we used the AAMC list of Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME)–accredited US medical schools; medical schools in Puerto Rico were not included, nor were pending and provisional institutions. If an institution had multiple practice sites for its students, the primary site for third-year medical student clerkship rotations was included. If a medical school had multiple branches, each with its own primary inpatient pediatrics site, these sites were included. If there was no PHM division director, a program leader (lead hospitalist) was substituted and counted as long as the role was formally designated. This leadership role is herein referred to under the umbrella term of “division director.”

We searched medical school web pages, affiliated hospital web pages, and Google. All program leadership information (divisional and fellowship, if present) was confirmed through direct communication with the program, most commonly with division directors, and included name, gender, title, and presence of associate/assistant leader, gender, and title. Associate division directors were only included if it was a formal leadership position. Associate directors of research, quality, etc, were not included due to the limited number of formal positions noted on further review. Of note, the terms “associate” and “assistant” are referring to leadership positions and not academic ranks.

Fellowship leadership was included if affiliated with a US medical school in the primary list. Medical schools with multiple PHM fellowships were included as separate observations. The leadership was confirmed using the methods described above and cross-referenced through the PHM Fellowship Program website. PHM fellowship programs starting in 2020 were included if leadership was determined.

All leadership positions were verified by two authors, and all authors reviewed the master list to identify errors.

To determine the overall gender breakdown in the specialty, we used three estimates: 2019 American Board of Pediatrics (ABP) PHM Board Certification Exam applicants, the 2019 American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Hospital Medicine membership, and a random sample of all PHM faculty in 25% of the programs included in this study.4

Descriptive statistics using 95% confidence intervals for proportions were used. Differences between proportions were evaluated using a two-proportion z test with the null hypothesis that the two proportions are the same and significance set at P < .05.

RESULTS

Of the 150 AAMC LCME–accredited medical school departments of pediatrics evaluated, a total of 142 programs were included; eight programs were excluded due to not providing inpatient pediatric services.

Division Leadership

The proportion of women PHM division directors was 55% (95% CI, 47%-63%) in this sample of 146 leaders from 142 programs (4 programs had coleaders). In the 113 programs with standalone PHM divisions or sections, the proportion of women division directors was 56% (95% CI, 47%-64%). In the 29 hospitalist groups that were not standalone (ie, embedded in another division), the proportion of women leaders was similar at 52% (95% CI, 34%-69%). In 24 programs with 27 formally designated associate directors (1 program had 3 associate directors and 1 program had 2), 81% of associate directors were women (95% CI, 63%-92%).

Fellowship Leadership

A total of 51 PHM fellowship programs had 53 directors (2 had codirectors), and 66% of the fellowship directors were women (95% CI, 53%-77%). A total of 31 programs had 34 assistant directors (3 programs had 2 assistants), and 82% of the assistant fellowship directors were women (95% CI, 66%-92%).

Comparison With the Field at Large

The inaugural ABP PHM board certification exam in 2019 had 1,627 applicants with 70% women (95% CI, 68%-73%) (Suzanne Woods, MD, email communication, December 4, 2019). The American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Hospital Medicine, the largest PHM-specific organization, has 2,299 practicing physician members with 71% women (95% CI, 69%-73%) (Niccole Alexander, email communication, November 25, 2019). Our random sample of 25% of university-based PHM programs contained 1,063 faculty members with 72% women (95% CI, 69%-75%).

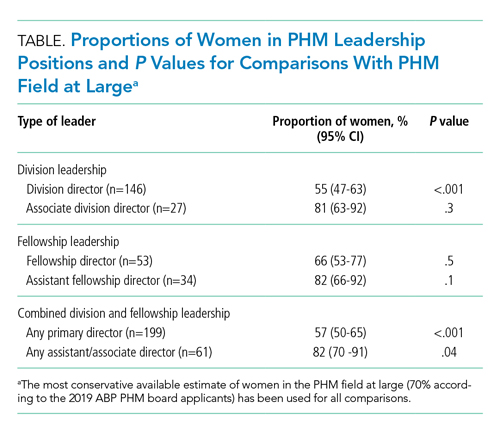

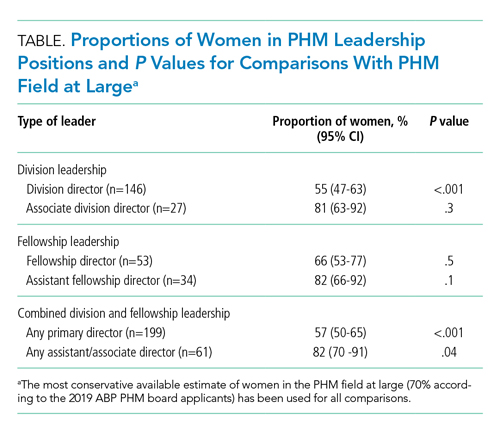

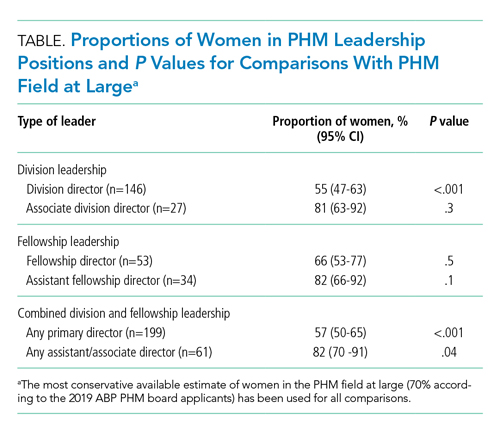

The Table provides P values for comparisons of the proportion of women in each of the above-described leadership roles compared to the most conservative estimate of women in the field from the estimates given above (ie, 70%). Compared with the field at large, women appear to be underrepresented as division directors (70% vs 55%; P < .001) but not as fellowship directors (70% vs 66%; P = .5). There is a higher proportion of women in all associate/assistant director roles, compared with the population (82% vs 70%; P = .04).

DISCUSSION

We found a significant difference between the proportion of women as PHM division directors (55%) when compared with the proportion of women physicians in PHM (70%), which suggests that women are underrepresented in clinical leadership at university-based pediatric hospitalist programs. Similar findings are described in other specialties, including notably adult hospital medicine.4 Burden et al found that only 16% of hospital medicine program leaders were women despite an equal number of women and men in the field. PHM has a much larger proportion of women, compared with that of hospital medicine, and yet women are still underrepresented as program leaders.

We found no disparities between the proportion of women as PHM fellowship directors and the field at large. These results are similar to those of other studies, which showed a higher number of women in educational leadership roles and lower representation in roles with influence over policy and allocation of resources.13,14 Although the proportion of women in educational roles itself is not a concern, there is evidence that these positions may be undervalued by some institutions, which provide these positions with lower salaries and fewer opportunities for career advancement.13,14

Interestingly, women are well-represented in associate/assistant director roles at both the division and fellowship leader level when comparing the distribution in those roles with that of the PHM field at large. This finding suggests that the pipeline of women is robust and potentially may indicate positive change. Alternatively, this finding may reflect a previously described phenomenon of the “sticky floor” in which women are “stuck” in these supportive roles and do not necessarily advance to higher-impact positions.15 We found a statistically significant higher proportion of women in the combined group of all associate/assistant directors compared with the overall population, which raises the concern that supportive leadership roles may represent “women’s work.”16 Future studies are needed to track whether these women truly advance or whether women are overrepresented in supportive leadership positions at the expense of primary leadership positions.

Adequate representation of women alone is not sufficient to achieve gender equity in medicine. We need to understand why there is a lower representation of women in leadership positions. Some barriers have already been described, including gender bias in promotions,17 higher demands outside of work,18 and lower pay,3 though none are specific to PHM. A further qualitative exploration of PHM leadership would help describe any barriers women in PHM specifically may be facing in their career trajectory. In addition, more information is needed to explore the experience of women with intersectional identities in PHM, especially since they may experience increased bias and discrimination.19

Limitations of this study include the lack of a centralized list of PHM programs and data on PHM workforce. Our three estimates for the proportion of women in PHM were similar at 70%-71%; however, these are only proxies for the true gender distribution of PHM physicians, which is unknown. PHM leadership targets of close to 70% women would be reflective of the field at large; however, institutional variation may exist, and ideally leadership should be diverse and reflective of its faculty members. Our study only describes university-based PHM programs and, therefore, is not necessarily generalizable to nonuniversity programs. Further studies are needed to evaluate any potential differences based on program type. In our study, gender was used in binary terms; however, we acknowledge that gender exists on a spectrum.

CONCLUSION

As a specialty early in development with a robust pipeline of women, PHM is in a unique position to lead the way in gender equity. However, women appear to be underrepresented as division directors at university-based PHM programs. Achieving proportional representation of women leaders is imperative for tapping into the full potential of the community and ensuring that the goals of the field are representative of the population.

Acknowledgment

Special thanks to Lucille Lester, MD, who asked the question that started this road to discovery.

1. Lautenberger DM, Dandar VM. State of Women in Academic Medicine 2018-2019 Exploring Pathways to Equity. AAMC; 2020. Accessed April 10, 2020. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/data/2018-2019-state-women-academic-medicine-exploring-pathways-equity

2. Table 13: U.S. Medical School Faculty by Sex, Rank, and Department, 2017. AAMC; 2019. Accessed June 25, 2020. https://www.aamc.org/download/486102/data/17table13.pdf

3. 2019 Physician Compensation Report. Doximity; March 2019. Accessed April 11, 2020. https://s3.amazonaws.com/s3.doximity.com/press/doximity_third_annual_physician_compensation_report_round3.pdf

4. Burden M, Frank MG, Keniston A, et al. Gender disparities in leadership and scholarly productivity of academic hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(8):481-485. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2340

5. Silver J, Ghalib R, Poorman JA, et al. Analysis of gender equity in leadership of physician-focused medical specialty societies, 2008-2017. JAMA Intern Med. 2019:179(3):433-435. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.5303

6. Thomas R, Cooper M, Konar E, et al. Lean In: Women in the Workplace 2019. McKinsey & Company; 2019. Accessed July 1, 2020. https://wiw-report.s3.amazonaws.com/Women_in_the_Workplace_2019.pdf

7. Table 1.3: Number and Percentage of Active Physicians by Sex and Specialty, 2017. AAMC; 2017. Accessed April 12, 2020. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/interactive-data/active-physicians-sex-and-specialty-2017

8. Taka F, Nomura K, Horie S, et al. Organizational climate with gender equity and burnout among university academics in Japan. Ind Health. 2016;54(6):480-487. https://doi.org/10.2486/indhealth.2016-0126

9. Tsugawa Y, Jena A, Figueroa J, Orav EJ, Blumenthal DM, Jha AK. Comparison of hospital mortality and readmission rates for medicare patients treated by male vs female physicians. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(2):206-213. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.7875

10. Bissing MA, Lange EMS, Davila WF, et al. Status of women in academic anesthesiology: a 10-year update. Anesth Analg. 2019;128(1):137-143. https://doi.org/10.1213/ane.0000000000003691

11. Graf N, Brown A, Patten E. The narrowing, but persistent, gender gap in pay. Pew Research Center; March 22, 2019. Accessed April 20, 2020. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/03/22/gender-pay-gap-facts/

12. American Board of Medical Specialties Officially Recognizes Pediatric Hospital Medicine Subspecialty Certification. News release. American Board of Medical Specialties; November 9, 2016. Accessed June 25, 2020. https://www.abms.org/media/120095/abms-recognizes-pediatric-hospital-medicine-as-a-subspecialty.pdf

13. Hofler LG, Hacker MR, Dodge LE, Schutzberg R, Ricciotti HA. Comparison of women in department leadership in obstetrics and gynecology with other specialties. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127(3):442-447. https://doi.org/10.1097/aog.0000000000001290

14. Weiss A, Lee KC, Tapia V, et al. Equity in surgical leadership for women: more work to do. Am J Surg. 2014;208:494-498. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2013.11.005

15. Tesch BJ, Wood HM, Helwig AL, Nattinger AB. Promotion of women physicians in academic medicine. Glass ceiling or sticky floor? JAMA. 1995;273(13):1022-1025.

16. Pelley E, Carnes M. When a specialty becomes “women’s work”: trends in and implications of specialty gender segregation in medicine. Acad Med. 2020;95(10):1499-1506. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000003555

17. Steinpreis RE, Anders KA, Ritzke D. The impact of gender on the review of the curricula vitae of job applicants and tenure candidates: a national empirical study. Sex Roles. 1999;41(7):509-528. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1018839203698

18. Jolly S, Griffith KA, DeCastro R, Stewart A, Ubel P, Jagsi R. Gender differences in time spent on parenting and domestic responsibilities by high-achieving young physician-researchers. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(5):344-353. https://doi.org/10.7326/m13-0974

19. Ginther DK, Kahn S, Schaffer WT. Gender, race/ethnicity, and National Institutes of Health R01 research awards: is there evidence of a double bind for women of color? Acad Med. 2016;91(8):1098-1107. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000001278

There is a growing appreciation of gender disparities in career advancement in medicine. By 2004, approximately 50% of medical school graduates were women, yet considerable differences persist between genders in compensation, faculty rank, and leadership positions.1-3 According to the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), women account for only 25% of full professors, 18% of department chairs, and 18% of medical school deans.1 Women are also underrepresented in other areas of leadership such as division directors, professional society leadership, and hospital executives.4-6

Specialties that are predominantly women, including pediatrics, are not immune to gender disparities. Women represent 71% of pediatric residents1 and currently constitute two-thirds of active pediatricians in the United States.7 However, there is a disproportionately low number of women ascending the pediatric academic ladder, with only 35% of full professors2 and 28% of department chairs being women.1 Pediatrics also was noted to have the fifth-largest gender pay gap across 40 specialties.3 These disparities can contribute to burnout, poorer patient outcomes, and decreased advancement of women known as the “leaky pipeline.”1,8,9

There is some evidence that gender disparities may be improving among younger professionals with increasing percentages of women as leaders and decreasing pay gaps.10,11 These potential positive trends provide hope that fields in medicine early in their development may demonstrate fewer gender disparities. One of the youngest fields of medicine is pediatric hospital medicine (PHM), which officially became a recognized pediatric subspecialty in 2017.12 There is no literature to date describing gender disparities in PHM. We aimed to explore the gender distribution of university-based PHM program leadership and to compare this gender distribution with that seen in the broader field of PHM.

METHODS

This study was Institutional Review Board–approved as non–human subjects research through University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois. From January to March 2020, the authors performed web-based searches for PHM division directors or program leaders in the United States. Because there is no single database of PHM programs in the United States, we used the AAMC list of Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME)–accredited US medical schools; medical schools in Puerto Rico were not included, nor were pending and provisional institutions. If an institution had multiple practice sites for its students, the primary site for third-year medical student clerkship rotations was included. If a medical school had multiple branches, each with its own primary inpatient pediatrics site, these sites were included. If there was no PHM division director, a program leader (lead hospitalist) was substituted and counted as long as the role was formally designated. This leadership role is herein referred to under the umbrella term of “division director.”

We searched medical school web pages, affiliated hospital web pages, and Google. All program leadership information (divisional and fellowship, if present) was confirmed through direct communication with the program, most commonly with division directors, and included name, gender, title, and presence of associate/assistant leader, gender, and title. Associate division directors were only included if it was a formal leadership position. Associate directors of research, quality, etc, were not included due to the limited number of formal positions noted on further review. Of note, the terms “associate” and “assistant” are referring to leadership positions and not academic ranks.

Fellowship leadership was included if affiliated with a US medical school in the primary list. Medical schools with multiple PHM fellowships were included as separate observations. The leadership was confirmed using the methods described above and cross-referenced through the PHM Fellowship Program website. PHM fellowship programs starting in 2020 were included if leadership was determined.

All leadership positions were verified by two authors, and all authors reviewed the master list to identify errors.

To determine the overall gender breakdown in the specialty, we used three estimates: 2019 American Board of Pediatrics (ABP) PHM Board Certification Exam applicants, the 2019 American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Hospital Medicine membership, and a random sample of all PHM faculty in 25% of the programs included in this study.4

Descriptive statistics using 95% confidence intervals for proportions were used. Differences between proportions were evaluated using a two-proportion z test with the null hypothesis that the two proportions are the same and significance set at P < .05.

RESULTS

Of the 150 AAMC LCME–accredited medical school departments of pediatrics evaluated, a total of 142 programs were included; eight programs were excluded due to not providing inpatient pediatric services.

Division Leadership

The proportion of women PHM division directors was 55% (95% CI, 47%-63%) in this sample of 146 leaders from 142 programs (4 programs had coleaders). In the 113 programs with standalone PHM divisions or sections, the proportion of women division directors was 56% (95% CI, 47%-64%). In the 29 hospitalist groups that were not standalone (ie, embedded in another division), the proportion of women leaders was similar at 52% (95% CI, 34%-69%). In 24 programs with 27 formally designated associate directors (1 program had 3 associate directors and 1 program had 2), 81% of associate directors were women (95% CI, 63%-92%).

Fellowship Leadership

A total of 51 PHM fellowship programs had 53 directors (2 had codirectors), and 66% of the fellowship directors were women (95% CI, 53%-77%). A total of 31 programs had 34 assistant directors (3 programs had 2 assistants), and 82% of the assistant fellowship directors were women (95% CI, 66%-92%).

Comparison With the Field at Large

The inaugural ABP PHM board certification exam in 2019 had 1,627 applicants with 70% women (95% CI, 68%-73%) (Suzanne Woods, MD, email communication, December 4, 2019). The American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Hospital Medicine, the largest PHM-specific organization, has 2,299 practicing physician members with 71% women (95% CI, 69%-73%) (Niccole Alexander, email communication, November 25, 2019). Our random sample of 25% of university-based PHM programs contained 1,063 faculty members with 72% women (95% CI, 69%-75%).

The Table provides P values for comparisons of the proportion of women in each of the above-described leadership roles compared to the most conservative estimate of women in the field from the estimates given above (ie, 70%). Compared with the field at large, women appear to be underrepresented as division directors (70% vs 55%; P < .001) but not as fellowship directors (70% vs 66%; P = .5). There is a higher proportion of women in all associate/assistant director roles, compared with the population (82% vs 70%; P = .04).

DISCUSSION

We found a significant difference between the proportion of women as PHM division directors (55%) when compared with the proportion of women physicians in PHM (70%), which suggests that women are underrepresented in clinical leadership at university-based pediatric hospitalist programs. Similar findings are described in other specialties, including notably adult hospital medicine.4 Burden et al found that only 16% of hospital medicine program leaders were women despite an equal number of women and men in the field. PHM has a much larger proportion of women, compared with that of hospital medicine, and yet women are still underrepresented as program leaders.

We found no disparities between the proportion of women as PHM fellowship directors and the field at large. These results are similar to those of other studies, which showed a higher number of women in educational leadership roles and lower representation in roles with influence over policy and allocation of resources.13,14 Although the proportion of women in educational roles itself is not a concern, there is evidence that these positions may be undervalued by some institutions, which provide these positions with lower salaries and fewer opportunities for career advancement.13,14

Interestingly, women are well-represented in associate/assistant director roles at both the division and fellowship leader level when comparing the distribution in those roles with that of the PHM field at large. This finding suggests that the pipeline of women is robust and potentially may indicate positive change. Alternatively, this finding may reflect a previously described phenomenon of the “sticky floor” in which women are “stuck” in these supportive roles and do not necessarily advance to higher-impact positions.15 We found a statistically significant higher proportion of women in the combined group of all associate/assistant directors compared with the overall population, which raises the concern that supportive leadership roles may represent “women’s work.”16 Future studies are needed to track whether these women truly advance or whether women are overrepresented in supportive leadership positions at the expense of primary leadership positions.

Adequate representation of women alone is not sufficient to achieve gender equity in medicine. We need to understand why there is a lower representation of women in leadership positions. Some barriers have already been described, including gender bias in promotions,17 higher demands outside of work,18 and lower pay,3 though none are specific to PHM. A further qualitative exploration of PHM leadership would help describe any barriers women in PHM specifically may be facing in their career trajectory. In addition, more information is needed to explore the experience of women with intersectional identities in PHM, especially since they may experience increased bias and discrimination.19

Limitations of this study include the lack of a centralized list of PHM programs and data on PHM workforce. Our three estimates for the proportion of women in PHM were similar at 70%-71%; however, these are only proxies for the true gender distribution of PHM physicians, which is unknown. PHM leadership targets of close to 70% women would be reflective of the field at large; however, institutional variation may exist, and ideally leadership should be diverse and reflective of its faculty members. Our study only describes university-based PHM programs and, therefore, is not necessarily generalizable to nonuniversity programs. Further studies are needed to evaluate any potential differences based on program type. In our study, gender was used in binary terms; however, we acknowledge that gender exists on a spectrum.

CONCLUSION

As a specialty early in development with a robust pipeline of women, PHM is in a unique position to lead the way in gender equity. However, women appear to be underrepresented as division directors at university-based PHM programs. Achieving proportional representation of women leaders is imperative for tapping into the full potential of the community and ensuring that the goals of the field are representative of the population.

Acknowledgment

Special thanks to Lucille Lester, MD, who asked the question that started this road to discovery.

There is a growing appreciation of gender disparities in career advancement in medicine. By 2004, approximately 50% of medical school graduates were women, yet considerable differences persist between genders in compensation, faculty rank, and leadership positions.1-3 According to the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), women account for only 25% of full professors, 18% of department chairs, and 18% of medical school deans.1 Women are also underrepresented in other areas of leadership such as division directors, professional society leadership, and hospital executives.4-6

Specialties that are predominantly women, including pediatrics, are not immune to gender disparities. Women represent 71% of pediatric residents1 and currently constitute two-thirds of active pediatricians in the United States.7 However, there is a disproportionately low number of women ascending the pediatric academic ladder, with only 35% of full professors2 and 28% of department chairs being women.1 Pediatrics also was noted to have the fifth-largest gender pay gap across 40 specialties.3 These disparities can contribute to burnout, poorer patient outcomes, and decreased advancement of women known as the “leaky pipeline.”1,8,9

There is some evidence that gender disparities may be improving among younger professionals with increasing percentages of women as leaders and decreasing pay gaps.10,11 These potential positive trends provide hope that fields in medicine early in their development may demonstrate fewer gender disparities. One of the youngest fields of medicine is pediatric hospital medicine (PHM), which officially became a recognized pediatric subspecialty in 2017.12 There is no literature to date describing gender disparities in PHM. We aimed to explore the gender distribution of university-based PHM program leadership and to compare this gender distribution with that seen in the broader field of PHM.

METHODS

This study was Institutional Review Board–approved as non–human subjects research through University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois. From January to March 2020, the authors performed web-based searches for PHM division directors or program leaders in the United States. Because there is no single database of PHM programs in the United States, we used the AAMC list of Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME)–accredited US medical schools; medical schools in Puerto Rico were not included, nor were pending and provisional institutions. If an institution had multiple practice sites for its students, the primary site for third-year medical student clerkship rotations was included. If a medical school had multiple branches, each with its own primary inpatient pediatrics site, these sites were included. If there was no PHM division director, a program leader (lead hospitalist) was substituted and counted as long as the role was formally designated. This leadership role is herein referred to under the umbrella term of “division director.”

We searched medical school web pages, affiliated hospital web pages, and Google. All program leadership information (divisional and fellowship, if present) was confirmed through direct communication with the program, most commonly with division directors, and included name, gender, title, and presence of associate/assistant leader, gender, and title. Associate division directors were only included if it was a formal leadership position. Associate directors of research, quality, etc, were not included due to the limited number of formal positions noted on further review. Of note, the terms “associate” and “assistant” are referring to leadership positions and not academic ranks.

Fellowship leadership was included if affiliated with a US medical school in the primary list. Medical schools with multiple PHM fellowships were included as separate observations. The leadership was confirmed using the methods described above and cross-referenced through the PHM Fellowship Program website. PHM fellowship programs starting in 2020 were included if leadership was determined.

All leadership positions were verified by two authors, and all authors reviewed the master list to identify errors.

To determine the overall gender breakdown in the specialty, we used three estimates: 2019 American Board of Pediatrics (ABP) PHM Board Certification Exam applicants, the 2019 American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Hospital Medicine membership, and a random sample of all PHM faculty in 25% of the programs included in this study.4

Descriptive statistics using 95% confidence intervals for proportions were used. Differences between proportions were evaluated using a two-proportion z test with the null hypothesis that the two proportions are the same and significance set at P < .05.

RESULTS

Of the 150 AAMC LCME–accredited medical school departments of pediatrics evaluated, a total of 142 programs were included; eight programs were excluded due to not providing inpatient pediatric services.

Division Leadership

The proportion of women PHM division directors was 55% (95% CI, 47%-63%) in this sample of 146 leaders from 142 programs (4 programs had coleaders). In the 113 programs with standalone PHM divisions or sections, the proportion of women division directors was 56% (95% CI, 47%-64%). In the 29 hospitalist groups that were not standalone (ie, embedded in another division), the proportion of women leaders was similar at 52% (95% CI, 34%-69%). In 24 programs with 27 formally designated associate directors (1 program had 3 associate directors and 1 program had 2), 81% of associate directors were women (95% CI, 63%-92%).

Fellowship Leadership

A total of 51 PHM fellowship programs had 53 directors (2 had codirectors), and 66% of the fellowship directors were women (95% CI, 53%-77%). A total of 31 programs had 34 assistant directors (3 programs had 2 assistants), and 82% of the assistant fellowship directors were women (95% CI, 66%-92%).

Comparison With the Field at Large

The inaugural ABP PHM board certification exam in 2019 had 1,627 applicants with 70% women (95% CI, 68%-73%) (Suzanne Woods, MD, email communication, December 4, 2019). The American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Hospital Medicine, the largest PHM-specific organization, has 2,299 practicing physician members with 71% women (95% CI, 69%-73%) (Niccole Alexander, email communication, November 25, 2019). Our random sample of 25% of university-based PHM programs contained 1,063 faculty members with 72% women (95% CI, 69%-75%).

The Table provides P values for comparisons of the proportion of women in each of the above-described leadership roles compared to the most conservative estimate of women in the field from the estimates given above (ie, 70%). Compared with the field at large, women appear to be underrepresented as division directors (70% vs 55%; P < .001) but not as fellowship directors (70% vs 66%; P = .5). There is a higher proportion of women in all associate/assistant director roles, compared with the population (82% vs 70%; P = .04).

DISCUSSION

We found a significant difference between the proportion of women as PHM division directors (55%) when compared with the proportion of women physicians in PHM (70%), which suggests that women are underrepresented in clinical leadership at university-based pediatric hospitalist programs. Similar findings are described in other specialties, including notably adult hospital medicine.4 Burden et al found that only 16% of hospital medicine program leaders were women despite an equal number of women and men in the field. PHM has a much larger proportion of women, compared with that of hospital medicine, and yet women are still underrepresented as program leaders.

We found no disparities between the proportion of women as PHM fellowship directors and the field at large. These results are similar to those of other studies, which showed a higher number of women in educational leadership roles and lower representation in roles with influence over policy and allocation of resources.13,14 Although the proportion of women in educational roles itself is not a concern, there is evidence that these positions may be undervalued by some institutions, which provide these positions with lower salaries and fewer opportunities for career advancement.13,14

Interestingly, women are well-represented in associate/assistant director roles at both the division and fellowship leader level when comparing the distribution in those roles with that of the PHM field at large. This finding suggests that the pipeline of women is robust and potentially may indicate positive change. Alternatively, this finding may reflect a previously described phenomenon of the “sticky floor” in which women are “stuck” in these supportive roles and do not necessarily advance to higher-impact positions.15 We found a statistically significant higher proportion of women in the combined group of all associate/assistant directors compared with the overall population, which raises the concern that supportive leadership roles may represent “women’s work.”16 Future studies are needed to track whether these women truly advance or whether women are overrepresented in supportive leadership positions at the expense of primary leadership positions.

Adequate representation of women alone is not sufficient to achieve gender equity in medicine. We need to understand why there is a lower representation of women in leadership positions. Some barriers have already been described, including gender bias in promotions,17 higher demands outside of work,18 and lower pay,3 though none are specific to PHM. A further qualitative exploration of PHM leadership would help describe any barriers women in PHM specifically may be facing in their career trajectory. In addition, more information is needed to explore the experience of women with intersectional identities in PHM, especially since they may experience increased bias and discrimination.19

Limitations of this study include the lack of a centralized list of PHM programs and data on PHM workforce. Our three estimates for the proportion of women in PHM were similar at 70%-71%; however, these are only proxies for the true gender distribution of PHM physicians, which is unknown. PHM leadership targets of close to 70% women would be reflective of the field at large; however, institutional variation may exist, and ideally leadership should be diverse and reflective of its faculty members. Our study only describes university-based PHM programs and, therefore, is not necessarily generalizable to nonuniversity programs. Further studies are needed to evaluate any potential differences based on program type. In our study, gender was used in binary terms; however, we acknowledge that gender exists on a spectrum.

CONCLUSION

As a specialty early in development with a robust pipeline of women, PHM is in a unique position to lead the way in gender equity. However, women appear to be underrepresented as division directors at university-based PHM programs. Achieving proportional representation of women leaders is imperative for tapping into the full potential of the community and ensuring that the goals of the field are representative of the population.

Acknowledgment

Special thanks to Lucille Lester, MD, who asked the question that started this road to discovery.

1. Lautenberger DM, Dandar VM. State of Women in Academic Medicine 2018-2019 Exploring Pathways to Equity. AAMC; 2020. Accessed April 10, 2020. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/data/2018-2019-state-women-academic-medicine-exploring-pathways-equity

2. Table 13: U.S. Medical School Faculty by Sex, Rank, and Department, 2017. AAMC; 2019. Accessed June 25, 2020. https://www.aamc.org/download/486102/data/17table13.pdf

3. 2019 Physician Compensation Report. Doximity; March 2019. Accessed April 11, 2020. https://s3.amazonaws.com/s3.doximity.com/press/doximity_third_annual_physician_compensation_report_round3.pdf

4. Burden M, Frank MG, Keniston A, et al. Gender disparities in leadership and scholarly productivity of academic hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(8):481-485. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2340

5. Silver J, Ghalib R, Poorman JA, et al. Analysis of gender equity in leadership of physician-focused medical specialty societies, 2008-2017. JAMA Intern Med. 2019:179(3):433-435. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.5303

6. Thomas R, Cooper M, Konar E, et al. Lean In: Women in the Workplace 2019. McKinsey & Company; 2019. Accessed July 1, 2020. https://wiw-report.s3.amazonaws.com/Women_in_the_Workplace_2019.pdf

7. Table 1.3: Number and Percentage of Active Physicians by Sex and Specialty, 2017. AAMC; 2017. Accessed April 12, 2020. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/interactive-data/active-physicians-sex-and-specialty-2017

8. Taka F, Nomura K, Horie S, et al. Organizational climate with gender equity and burnout among university academics in Japan. Ind Health. 2016;54(6):480-487. https://doi.org/10.2486/indhealth.2016-0126

9. Tsugawa Y, Jena A, Figueroa J, Orav EJ, Blumenthal DM, Jha AK. Comparison of hospital mortality and readmission rates for medicare patients treated by male vs female physicians. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(2):206-213. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.7875

10. Bissing MA, Lange EMS, Davila WF, et al. Status of women in academic anesthesiology: a 10-year update. Anesth Analg. 2019;128(1):137-143. https://doi.org/10.1213/ane.0000000000003691

11. Graf N, Brown A, Patten E. The narrowing, but persistent, gender gap in pay. Pew Research Center; March 22, 2019. Accessed April 20, 2020. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/03/22/gender-pay-gap-facts/

12. American Board of Medical Specialties Officially Recognizes Pediatric Hospital Medicine Subspecialty Certification. News release. American Board of Medical Specialties; November 9, 2016. Accessed June 25, 2020. https://www.abms.org/media/120095/abms-recognizes-pediatric-hospital-medicine-as-a-subspecialty.pdf

13. Hofler LG, Hacker MR, Dodge LE, Schutzberg R, Ricciotti HA. Comparison of women in department leadership in obstetrics and gynecology with other specialties. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127(3):442-447. https://doi.org/10.1097/aog.0000000000001290

14. Weiss A, Lee KC, Tapia V, et al. Equity in surgical leadership for women: more work to do. Am J Surg. 2014;208:494-498. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2013.11.005

15. Tesch BJ, Wood HM, Helwig AL, Nattinger AB. Promotion of women physicians in academic medicine. Glass ceiling or sticky floor? JAMA. 1995;273(13):1022-1025.

16. Pelley E, Carnes M. When a specialty becomes “women’s work”: trends in and implications of specialty gender segregation in medicine. Acad Med. 2020;95(10):1499-1506. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000003555

17. Steinpreis RE, Anders KA, Ritzke D. The impact of gender on the review of the curricula vitae of job applicants and tenure candidates: a national empirical study. Sex Roles. 1999;41(7):509-528. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1018839203698

18. Jolly S, Griffith KA, DeCastro R, Stewart A, Ubel P, Jagsi R. Gender differences in time spent on parenting and domestic responsibilities by high-achieving young physician-researchers. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(5):344-353. https://doi.org/10.7326/m13-0974

19. Ginther DK, Kahn S, Schaffer WT. Gender, race/ethnicity, and National Institutes of Health R01 research awards: is there evidence of a double bind for women of color? Acad Med. 2016;91(8):1098-1107. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000001278

1. Lautenberger DM, Dandar VM. State of Women in Academic Medicine 2018-2019 Exploring Pathways to Equity. AAMC; 2020. Accessed April 10, 2020. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/data/2018-2019-state-women-academic-medicine-exploring-pathways-equity

2. Table 13: U.S. Medical School Faculty by Sex, Rank, and Department, 2017. AAMC; 2019. Accessed June 25, 2020. https://www.aamc.org/download/486102/data/17table13.pdf

3. 2019 Physician Compensation Report. Doximity; March 2019. Accessed April 11, 2020. https://s3.amazonaws.com/s3.doximity.com/press/doximity_third_annual_physician_compensation_report_round3.pdf

4. Burden M, Frank MG, Keniston A, et al. Gender disparities in leadership and scholarly productivity of academic hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(8):481-485. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2340

5. Silver J, Ghalib R, Poorman JA, et al. Analysis of gender equity in leadership of physician-focused medical specialty societies, 2008-2017. JAMA Intern Med. 2019:179(3):433-435. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.5303

6. Thomas R, Cooper M, Konar E, et al. Lean In: Women in the Workplace 2019. McKinsey & Company; 2019. Accessed July 1, 2020. https://wiw-report.s3.amazonaws.com/Women_in_the_Workplace_2019.pdf

7. Table 1.3: Number and Percentage of Active Physicians by Sex and Specialty, 2017. AAMC; 2017. Accessed April 12, 2020. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/interactive-data/active-physicians-sex-and-specialty-2017

8. Taka F, Nomura K, Horie S, et al. Organizational climate with gender equity and burnout among university academics in Japan. Ind Health. 2016;54(6):480-487. https://doi.org/10.2486/indhealth.2016-0126

9. Tsugawa Y, Jena A, Figueroa J, Orav EJ, Blumenthal DM, Jha AK. Comparison of hospital mortality and readmission rates for medicare patients treated by male vs female physicians. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(2):206-213. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.7875

10. Bissing MA, Lange EMS, Davila WF, et al. Status of women in academic anesthesiology: a 10-year update. Anesth Analg. 2019;128(1):137-143. https://doi.org/10.1213/ane.0000000000003691

11. Graf N, Brown A, Patten E. The narrowing, but persistent, gender gap in pay. Pew Research Center; March 22, 2019. Accessed April 20, 2020. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/03/22/gender-pay-gap-facts/

12. American Board of Medical Specialties Officially Recognizes Pediatric Hospital Medicine Subspecialty Certification. News release. American Board of Medical Specialties; November 9, 2016. Accessed June 25, 2020. https://www.abms.org/media/120095/abms-recognizes-pediatric-hospital-medicine-as-a-subspecialty.pdf

13. Hofler LG, Hacker MR, Dodge LE, Schutzberg R, Ricciotti HA. Comparison of women in department leadership in obstetrics and gynecology with other specialties. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127(3):442-447. https://doi.org/10.1097/aog.0000000000001290

14. Weiss A, Lee KC, Tapia V, et al. Equity in surgical leadership for women: more work to do. Am J Surg. 2014;208:494-498. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2013.11.005

15. Tesch BJ, Wood HM, Helwig AL, Nattinger AB. Promotion of women physicians in academic medicine. Glass ceiling or sticky floor? JAMA. 1995;273(13):1022-1025.

16. Pelley E, Carnes M. When a specialty becomes “women’s work”: trends in and implications of specialty gender segregation in medicine. Acad Med. 2020;95(10):1499-1506. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000003555

17. Steinpreis RE, Anders KA, Ritzke D. The impact of gender on the review of the curricula vitae of job applicants and tenure candidates: a national empirical study. Sex Roles. 1999;41(7):509-528. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1018839203698

18. Jolly S, Griffith KA, DeCastro R, Stewart A, Ubel P, Jagsi R. Gender differences in time spent on parenting and domestic responsibilities by high-achieving young physician-researchers. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(5):344-353. https://doi.org/10.7326/m13-0974

19. Ginther DK, Kahn S, Schaffer WT. Gender, race/ethnicity, and National Institutes of Health R01 research awards: is there evidence of a double bind for women of color? Acad Med. 2016;91(8):1098-1107. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000001278

© 2021 Society of Hospital Medicine

Collective Action and Effective Dialogue to Address Gender Bias in Medicine

In 2016, Pediatric Hospital Medicine (PHM) was recognized as a subspecialty under the American Board of Pediatrics (ABP), one of 24 certifying boards of the American Board of Medical Specialties. As with all new ABP subspecialty certification processes, a “practice pathway” with specific eligibility criteria allows individuals with expertise and sufficient practice experience within the discipline to take the certification examination. For PHM, certification via the practice pathway is permissible for the 2019, 2021, and 2023 certifying examinations.1 In this perspective, we provide an illustration of ABP leadership and the PHM community partnering to mitigate unintentional gender bias that surfaced after the practice pathway eligibility criteria were implemented. We also provide recommendations to revise these criteria to eliminate future gender bias and promote equity in medicine.

In July 2019, individuals within the PHM community began to share stories of being denied eligibility to sit for the 2019 exam.2 Some of the reported denials were due to an eligibility criterion related to “practice interruptions”, which stated that practice interruptions cannot exceed three months in the preceding four years or six months in the preceding five years. Notably, some women reported that their applications were denied because of practice interruptions due to maternity leave. These stories raised significant concerns of gender bias in the board certification process and sparked collective action to revise the board certification eligibility criteria. A petition was circulated within the PHM community and received 1,479 signatures in two weeks.

Given the magnitude of concern, leaders within the PHM community, with support from the American Academy of Pediatrics, collaboratively engaged with the ABP and members of the ABP PHM subboard to improve the transparency and equity of the eligibility process. As a result of this activism and effective dialogue, the ABP revised the PHM board certification eligibility criteria and removed the practice interruption criterion.1 Through this unique experience of advocacy and partner

Gender bias is defined as the unfair difference in the way men and women are treated.3 Maternal bias is further characterized as bias experienced by mothers related to motherhood, often involving discrimination based on pregnancy, maternity leave, or breastfeeding. Both are common in medicine. Two-thirds of physician mothers report experiencing gender bias and more than a third experience maternal bias.4 This bias may be explicit, or intentional, but often the bias is unintentional. This bias can occur even with equal representation of women and men on committees determining eligibility, and even when the committee believes it is not biased.5 Furthermore, gender or maternal bias negatively affects individuals in medicine in regards to future employment, career advancement, and compensation.6-11

Given these implications, we celebrate the removal of the practice interruptions criterion as it was unintentionally biased against women. Eligibility criteria that considered practice interruptions would have disproportionately affected women due to leaves related to pregnancy and due to discrepancies in the length of parental leave for mothers versus fathers. Though the ABP’s initial review of cases of denial did not demonstrate a significant difference in the proportion of men and women who were denied, these data may be misleading. Potential reasons why the ABP did not find significant differences in denial rates between women and men include: (1) some women who had recent maternity leaves chose not to apply because of concerns they may be denied; or (2) some women did not disclose maternity leaves on their application because they did not interpret maternity leave to be a practice interruption. This “self-censoring” may have resulted in incomplete data, making it difficult to fully understand the differential impact of this criterion on women versus men. Therefore, it is essential that we as a profession continue to identify any areas where gender bias exists in determining eligibility for certification, employment, or career advancement within medicine and eliminate it.

Despite the improvements made in the revised criteria, further revision is necessary to remove the criterion related to the “start date”, which will differentially affect women. This criterion states that an individual must have started their PHM practice on or before July of the first year of a four-year look-back period (eg, July 2015 for the 2019 cycle). We present three theoretical cases to illustrate gender bias with respect to this criterion (Table). Even though Applicants #2 and #3 accrue far more than the minimum number of hours in their first year—and more hours overall than Applicant #1—both of these women will remain ineligible under the revised criteria. While Applicant #2 could be eligible for the 2021 or 2023 cycle, Applicant #3, who is new to PHM practice in 2019 as a residency graduate, will not be eligible at all under the practice pathway due to delayed graduation from residency.

Parental leave during residency following birth of a child may result in the need to make up the time missed.12 This means that more women than men will experience delayed entry into the workforce due to late graduation from residency.13 Women who experience a gap in employment at the start of their PHM practice due to pregnancy or childbirth will also be differentially affected by this criterion. If this same type of gap were to occur later in the year, it would no longer impact a woman’s eligibility under the revised criteria. Therefore, we implore the ABP to reevaluate this criterion which results in a hidden “practice interruption” penalty. Removing eligibility criteria related to practice interruptions, wherever they may occur, will not only eliminate systematic bias against women, but may also encourage men to take paternity leave, for which the benefits to both men and women are well described.14,15

We support the ABP’s mission to maintain the public’s trust by ensuring PHM board certification is an indicator that individuals have met a high standard. We acknowledge that the ABP and PHM subboard had to draw a line to create minimum standards. The start date and four-year look-back criteria were informed by prior certification processes, and the PHM community was given the opportunity to comment on these criteria prior to final ABP approval. However, now that we have become aware of how the start date criteria can differentially impact women and men, we must reevaluate this line to ensure that women and men are treated equally. Similar to the removal of the practice interruptions criterion, we do not believe that removal of the start date criterion will in any way compromise these standards. A four-year look-back period will still be in place and individuals will still be required to accrue the minimum number of hours in the first year and each subsequent year of the four-year period.

Despite any change in the criteria, there will be individuals who remain ineligible for PHM board certification. We will need to rely on institutions and the societies that lead PHM to remember that not all individuals had the opportunity to certify as a pediatric hospitalist, and for some, this was due to maternity leave. No woman should have to worry about her future employment when considering motherhood.

We hope the lessons learned from this experience will be informative for other specialties considering a new certification. Committees designing new criteria should have proportional representation of women and men, inclusion of underrepresented minorities, and members with a range of ages, orientations, identities, and abilities. Criteria should be closely scrutinized to evaluate if a single group of people is more likely to be excluded. All application reviewers should undergo training in identifying implicit bias.16 Once eligibility criteria are determined, they should be transparent to all applicants, consistently applied, and decisions to applicants should clearly state which criteria were or were not met. Regular audits should be conducted to identify any bias. Finally, transparent and respectful dialogue between the certifying board and the physician community is paramount to ensuring continuous quality improvement in the process.

The PHM experience with this new board certification process highlights the positive impact that the PHM community had engaging with the ABP leadership, who listened to the concerns and revised the eligibility criteria. We are optimistic that this productive relationship will continue to eliminate any gender bias in the board certification process. In turn, PHM and the ABP can be leaders in ending gender inequity in medicine.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

1. Nichols DG, Woods SK. The American Board of Pediatrics response to the Pediatric Hospital Medicine petition. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(10):586-588. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3322

2. Don’t make me choose between motherhood and my career. https://www.kevinmd.com/blog/2019/08/dont-make-me-choose-between-motherhood-and-my-career.html. Accessed September 16, 2019.

3. GENDER BIAS | definition in the Cambridge English Dictionary. April 2019. https://dictionary.cambridge.org/us/dictionary/english/gender-bias.

4. Adesoye T, Mangurian C, Choo EK, Girgis C, Sabry-Elnaggar H, Linos E. Perceived discrimination experienced by physician mothers and desired workplace changes: A cross-sectional survey. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(7):1033-1036. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.1394

5. Régner I, Thinus-Blanc C, Netter A, Schmader T, Huguet P. Committees with implicit biases promote fewer women when they do not believe gender bias exists. Nat Hum Behav. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-019-0686-3

6. Trix F, Psenka C. Exploring the color of glass: Letters of recommendation for female and male medical faculty. Discourse Soc. 2003;14(2):191-220. https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926503014002277

7. Correll SJ, Benard S, Paik I. Getting a job: Is there a motherhood penalty? Am J Sociol. 2007;112(5):1297-1339. https://doi.org/10.1086/511799

8. Aamc. Analysis in Brief - August 2009: Unconscious Bias in Faculty and Leadership Recruitment: A Literature Review; 2009. https://implicit.harvard.edu/. Accessed September 10, 2019.

9. Wright AL, Schwindt LA, Bassford TL, et al. Gender differences in academic advancement: patterns, causes, and potential solutions in one US College of Medicine. Acad Med. 2003;78(5):500-508. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200305000-00015

10. Weaver AC, Wetterneck TB, Whelan CT, Hinami K. A matter of priorities? Exploring the persistent gender pay gap in hospital medicine. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(8):486-490. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2400

11. Frintner MP, Sisk B, Byrne BJ, Freed GL, Starmer AJ, Olson LM. Gender differences in earnings of early- and midcareer pediatricians. Pediatrics. September 2019:e20183955. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-3955

12. Section on Medical Students, Residents and Fellowship Trainees, Committee on Early Childhood. Parental leave for residents and pediatric training programs. Pediatrics. 2013;131(2):387-390. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-3542

13. Jagsi R, Tarbell NJ, Weinstein DF. Becoming a doctor, starting a family — leaves of absence from graduate medical education. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(19):1889-1891. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp078163

14. Nepomnyaschy L, Waldfogel J. Paternity leave and fathers’ involvement with their young children. Community Work Fam. 2007;10(4):427-453. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668800701575077

15. Andersen SH. Paternity leave and the motherhood penalty: New causal evidence. J Marriage Fam. 2018;80(5):1125-1143. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12507.

16. Girod S, Fassiotto M, Grewal D, et al. Reducing Implicit Gender Leadership Bias in Academic Medicine With an Educational Intervention. Acad Med. 2016;91(8):1143-1150. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001099

In 2016, Pediatric Hospital Medicine (PHM) was recognized as a subspecialty under the American Board of Pediatrics (ABP), one of 24 certifying boards of the American Board of Medical Specialties. As with all new ABP subspecialty certification processes, a “practice pathway” with specific eligibility criteria allows individuals with expertise and sufficient practice experience within the discipline to take the certification examination. For PHM, certification via the practice pathway is permissible for the 2019, 2021, and 2023 certifying examinations.1 In this perspective, we provide an illustration of ABP leadership and the PHM community partnering to mitigate unintentional gender bias that surfaced after the practice pathway eligibility criteria were implemented. We also provide recommendations to revise these criteria to eliminate future gender bias and promote equity in medicine.

In July 2019, individuals within the PHM community began to share stories of being denied eligibility to sit for the 2019 exam.2 Some of the reported denials were due to an eligibility criterion related to “practice interruptions”, which stated that practice interruptions cannot exceed three months in the preceding four years or six months in the preceding five years. Notably, some women reported that their applications were denied because of practice interruptions due to maternity leave. These stories raised significant concerns of gender bias in the board certification process and sparked collective action to revise the board certification eligibility criteria. A petition was circulated within the PHM community and received 1,479 signatures in two weeks.

Given the magnitude of concern, leaders within the PHM community, with support from the American Academy of Pediatrics, collaboratively engaged with the ABP and members of the ABP PHM subboard to improve the transparency and equity of the eligibility process. As a result of this activism and effective dialogue, the ABP revised the PHM board certification eligibility criteria and removed the practice interruption criterion.1 Through this unique experience of advocacy and partner

Gender bias is defined as the unfair difference in the way men and women are treated.3 Maternal bias is further characterized as bias experienced by mothers related to motherhood, often involving discrimination based on pregnancy, maternity leave, or breastfeeding. Both are common in medicine. Two-thirds of physician mothers report experiencing gender bias and more than a third experience maternal bias.4 This bias may be explicit, or intentional, but often the bias is unintentional. This bias can occur even with equal representation of women and men on committees determining eligibility, and even when the committee believes it is not biased.5 Furthermore, gender or maternal bias negatively affects individuals in medicine in regards to future employment, career advancement, and compensation.6-11

Given these implications, we celebrate the removal of the practice interruptions criterion as it was unintentionally biased against women. Eligibility criteria that considered practice interruptions would have disproportionately affected women due to leaves related to pregnancy and due to discrepancies in the length of parental leave for mothers versus fathers. Though the ABP’s initial review of cases of denial did not demonstrate a significant difference in the proportion of men and women who were denied, these data may be misleading. Potential reasons why the ABP did not find significant differences in denial rates between women and men include: (1) some women who had recent maternity leaves chose not to apply because of concerns they may be denied; or (2) some women did not disclose maternity leaves on their application because they did not interpret maternity leave to be a practice interruption. This “self-censoring” may have resulted in incomplete data, making it difficult to fully understand the differential impact of this criterion on women versus men. Therefore, it is essential that we as a profession continue to identify any areas where gender bias exists in determining eligibility for certification, employment, or career advancement within medicine and eliminate it.

Despite the improvements made in the revised criteria, further revision is necessary to remove the criterion related to the “start date”, which will differentially affect women. This criterion states that an individual must have started their PHM practice on or before July of the first year of a four-year look-back period (eg, July 2015 for the 2019 cycle). We present three theoretical cases to illustrate gender bias with respect to this criterion (Table). Even though Applicants #2 and #3 accrue far more than the minimum number of hours in their first year—and more hours overall than Applicant #1—both of these women will remain ineligible under the revised criteria. While Applicant #2 could be eligible for the 2021 or 2023 cycle, Applicant #3, who is new to PHM practice in 2019 as a residency graduate, will not be eligible at all under the practice pathway due to delayed graduation from residency.

Parental leave during residency following birth of a child may result in the need to make up the time missed.12 This means that more women than men will experience delayed entry into the workforce due to late graduation from residency.13 Women who experience a gap in employment at the start of their PHM practice due to pregnancy or childbirth will also be differentially affected by this criterion. If this same type of gap were to occur later in the year, it would no longer impact a woman’s eligibility under the revised criteria. Therefore, we implore the ABP to reevaluate this criterion which results in a hidden “practice interruption” penalty. Removing eligibility criteria related to practice interruptions, wherever they may occur, will not only eliminate systematic bias against women, but may also encourage men to take paternity leave, for which the benefits to both men and women are well described.14,15

We support the ABP’s mission to maintain the public’s trust by ensuring PHM board certification is an indicator that individuals have met a high standard. We acknowledge that the ABP and PHM subboard had to draw a line to create minimum standards. The start date and four-year look-back criteria were informed by prior certification processes, and the PHM community was given the opportunity to comment on these criteria prior to final ABP approval. However, now that we have become aware of how the start date criteria can differentially impact women and men, we must reevaluate this line to ensure that women and men are treated equally. Similar to the removal of the practice interruptions criterion, we do not believe that removal of the start date criterion will in any way compromise these standards. A four-year look-back period will still be in place and individuals will still be required to accrue the minimum number of hours in the first year and each subsequent year of the four-year period.

Despite any change in the criteria, there will be individuals who remain ineligible for PHM board certification. We will need to rely on institutions and the societies that lead PHM to remember that not all individuals had the opportunity to certify as a pediatric hospitalist, and for some, this was due to maternity leave. No woman should have to worry about her future employment when considering motherhood.

We hope the lessons learned from this experience will be informative for other specialties considering a new certification. Committees designing new criteria should have proportional representation of women and men, inclusion of underrepresented minorities, and members with a range of ages, orientations, identities, and abilities. Criteria should be closely scrutinized to evaluate if a single group of people is more likely to be excluded. All application reviewers should undergo training in identifying implicit bias.16 Once eligibility criteria are determined, they should be transparent to all applicants, consistently applied, and decisions to applicants should clearly state which criteria were or were not met. Regular audits should be conducted to identify any bias. Finally, transparent and respectful dialogue between the certifying board and the physician community is paramount to ensuring continuous quality improvement in the process.

The PHM experience with this new board certification process highlights the positive impact that the PHM community had engaging with the ABP leadership, who listened to the concerns and revised the eligibility criteria. We are optimistic that this productive relationship will continue to eliminate any gender bias in the board certification process. In turn, PHM and the ABP can be leaders in ending gender inequity in medicine.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

In 2016, Pediatric Hospital Medicine (PHM) was recognized as a subspecialty under the American Board of Pediatrics (ABP), one of 24 certifying boards of the American Board of Medical Specialties. As with all new ABP subspecialty certification processes, a “practice pathway” with specific eligibility criteria allows individuals with expertise and sufficient practice experience within the discipline to take the certification examination. For PHM, certification via the practice pathway is permissible for the 2019, 2021, and 2023 certifying examinations.1 In this perspective, we provide an illustration of ABP leadership and the PHM community partnering to mitigate unintentional gender bias that surfaced after the practice pathway eligibility criteria were implemented. We also provide recommendations to revise these criteria to eliminate future gender bias and promote equity in medicine.

In July 2019, individuals within the PHM community began to share stories of being denied eligibility to sit for the 2019 exam.2 Some of the reported denials were due to an eligibility criterion related to “practice interruptions”, which stated that practice interruptions cannot exceed three months in the preceding four years or six months in the preceding five years. Notably, some women reported that their applications were denied because of practice interruptions due to maternity leave. These stories raised significant concerns of gender bias in the board certification process and sparked collective action to revise the board certification eligibility criteria. A petition was circulated within the PHM community and received 1,479 signatures in two weeks.

Given the magnitude of concern, leaders within the PHM community, with support from the American Academy of Pediatrics, collaboratively engaged with the ABP and members of the ABP PHM subboard to improve the transparency and equity of the eligibility process. As a result of this activism and effective dialogue, the ABP revised the PHM board certification eligibility criteria and removed the practice interruption criterion.1 Through this unique experience of advocacy and partner

Gender bias is defined as the unfair difference in the way men and women are treated.3 Maternal bias is further characterized as bias experienced by mothers related to motherhood, often involving discrimination based on pregnancy, maternity leave, or breastfeeding. Both are common in medicine. Two-thirds of physician mothers report experiencing gender bias and more than a third experience maternal bias.4 This bias may be explicit, or intentional, but often the bias is unintentional. This bias can occur even with equal representation of women and men on committees determining eligibility, and even when the committee believes it is not biased.5 Furthermore, gender or maternal bias negatively affects individuals in medicine in regards to future employment, career advancement, and compensation.6-11

Given these implications, we celebrate the removal of the practice interruptions criterion as it was unintentionally biased against women. Eligibility criteria that considered practice interruptions would have disproportionately affected women due to leaves related to pregnancy and due to discrepancies in the length of parental leave for mothers versus fathers. Though the ABP’s initial review of cases of denial did not demonstrate a significant difference in the proportion of men and women who were denied, these data may be misleading. Potential reasons why the ABP did not find significant differences in denial rates between women and men include: (1) some women who had recent maternity leaves chose not to apply because of concerns they may be denied; or (2) some women did not disclose maternity leaves on their application because they did not interpret maternity leave to be a practice interruption. This “self-censoring” may have resulted in incomplete data, making it difficult to fully understand the differential impact of this criterion on women versus men. Therefore, it is essential that we as a profession continue to identify any areas where gender bias exists in determining eligibility for certification, employment, or career advancement within medicine and eliminate it.

Despite the improvements made in the revised criteria, further revision is necessary to remove the criterion related to the “start date”, which will differentially affect women. This criterion states that an individual must have started their PHM practice on or before July of the first year of a four-year look-back period (eg, July 2015 for the 2019 cycle). We present three theoretical cases to illustrate gender bias with respect to this criterion (Table). Even though Applicants #2 and #3 accrue far more than the minimum number of hours in their first year—and more hours overall than Applicant #1—both of these women will remain ineligible under the revised criteria. While Applicant #2 could be eligible for the 2021 or 2023 cycle, Applicant #3, who is new to PHM practice in 2019 as a residency graduate, will not be eligible at all under the practice pathway due to delayed graduation from residency.

Parental leave during residency following birth of a child may result in the need to make up the time missed.12 This means that more women than men will experience delayed entry into the workforce due to late graduation from residency.13 Women who experience a gap in employment at the start of their PHM practice due to pregnancy or childbirth will also be differentially affected by this criterion. If this same type of gap were to occur later in the year, it would no longer impact a woman’s eligibility under the revised criteria. Therefore, we implore the ABP to reevaluate this criterion which results in a hidden “practice interruption” penalty. Removing eligibility criteria related to practice interruptions, wherever they may occur, will not only eliminate systematic bias against women, but may also encourage men to take paternity leave, for which the benefits to both men and women are well described.14,15

We support the ABP’s mission to maintain the public’s trust by ensuring PHM board certification is an indicator that individuals have met a high standard. We acknowledge that the ABP and PHM subboard had to draw a line to create minimum standards. The start date and four-year look-back criteria were informed by prior certification processes, and the PHM community was given the opportunity to comment on these criteria prior to final ABP approval. However, now that we have become aware of how the start date criteria can differentially impact women and men, we must reevaluate this line to ensure that women and men are treated equally. Similar to the removal of the practice interruptions criterion, we do not believe that removal of the start date criterion will in any way compromise these standards. A four-year look-back period will still be in place and individuals will still be required to accrue the minimum number of hours in the first year and each subsequent year of the four-year period.

Despite any change in the criteria, there will be individuals who remain ineligible for PHM board certification. We will need to rely on institutions and the societies that lead PHM to remember that not all individuals had the opportunity to certify as a pediatric hospitalist, and for some, this was due to maternity leave. No woman should have to worry about her future employment when considering motherhood.

We hope the lessons learned from this experience will be informative for other specialties considering a new certification. Committees designing new criteria should have proportional representation of women and men, inclusion of underrepresented minorities, and members with a range of ages, orientations, identities, and abilities. Criteria should be closely scrutinized to evaluate if a single group of people is more likely to be excluded. All application reviewers should undergo training in identifying implicit bias.16 Once eligibility criteria are determined, they should be transparent to all applicants, consistently applied, and decisions to applicants should clearly state which criteria were or were not met. Regular audits should be conducted to identify any bias. Finally, transparent and respectful dialogue between the certifying board and the physician community is paramount to ensuring continuous quality improvement in the process.

The PHM experience with this new board certification process highlights the positive impact that the PHM community had engaging with the ABP leadership, who listened to the concerns and revised the eligibility criteria. We are optimistic that this productive relationship will continue to eliminate any gender bias in the board certification process. In turn, PHM and the ABP can be leaders in ending gender inequity in medicine.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

1. Nichols DG, Woods SK. The American Board of Pediatrics response to the Pediatric Hospital Medicine petition. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(10):586-588. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3322

2. Don’t make me choose between motherhood and my career. https://www.kevinmd.com/blog/2019/08/dont-make-me-choose-between-motherhood-and-my-career.html. Accessed September 16, 2019.

3. GENDER BIAS | definition in the Cambridge English Dictionary. April 2019. https://dictionary.cambridge.org/us/dictionary/english/gender-bias.

4. Adesoye T, Mangurian C, Choo EK, Girgis C, Sabry-Elnaggar H, Linos E. Perceived discrimination experienced by physician mothers and desired workplace changes: A cross-sectional survey. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(7):1033-1036. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.1394

5. Régner I, Thinus-Blanc C, Netter A, Schmader T, Huguet P. Committees with implicit biases promote fewer women when they do not believe gender bias exists. Nat Hum Behav. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-019-0686-3

6. Trix F, Psenka C. Exploring the color of glass: Letters of recommendation for female and male medical faculty. Discourse Soc. 2003;14(2):191-220. https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926503014002277

7. Correll SJ, Benard S, Paik I. Getting a job: Is there a motherhood penalty? Am J Sociol. 2007;112(5):1297-1339. https://doi.org/10.1086/511799

8. Aamc. Analysis in Brief - August 2009: Unconscious Bias in Faculty and Leadership Recruitment: A Literature Review; 2009. https://implicit.harvard.edu/. Accessed September 10, 2019.

9. Wright AL, Schwindt LA, Bassford TL, et al. Gender differences in academic advancement: patterns, causes, and potential solutions in one US College of Medicine. Acad Med. 2003;78(5):500-508. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200305000-00015

10. Weaver AC, Wetterneck TB, Whelan CT, Hinami K. A matter of priorities? Exploring the persistent gender pay gap in hospital medicine. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(8):486-490. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2400