User login

Community Pediatric Hospitalist Workload: Results from a National Survey

As a newly recognized specialty, pediatric hospital medicine (PHM) continues to expand and diversify.1 Pediatric hospitalists care for children in hospitals ranging from small, rural community hospitals to large, free-standing quaternary children’s hospitals.2-4 In addition, more than 10% of graduating pediatric residents are seeking future careers within PHM.5

In 2018, Fromme et al. published a study describing clinical workload for pediatric hospitalists within university-based settings.6 They characterized the diversity of work models and programmatic sustainability but limited the study to university-based programs. With over half of children receiving care within community hospitals,7 workforce patterns for community-based pediatric hospitalists should be characterized to maximize sustainability and minimize attrition across the field.

In this study, we describe programmatic variability in clinical work expectations of 70 community-based PHM programs. We aimed to describe existing work models and expectations of community-based program leaders as they relate to their unique clinical setting.

METHODS

We conducted a cross-sectional survey of community-based PHM site directors through structured interviews. Community hospital programs were self-defined by the study participants, although typically defined as general hospitals that admit pediatric patients and are not free-standing or children’s hospitals within a general hospital. Survey respondents were asked to answer questions only reflecting expectations at their community hospital.

Survey Design and Content

Building from a tool used by Fromme et al.6 we created a 12-question structured interview questionnaire focused on three areas: (1) full-time employment (FTE) metrics including definitions of a 1.0 FTE, “typical” shifts, and weekend responsibilities; (2) work volume including census parameters, service-line coverage expectations, back-up systems, and overnight call responsibilities; and (3) programmatic model including sense of sustainability (eg, minimizing burnout and attrition), support for activities such as administrative or research time, and employer model (Appendix).

We modified the survey through research team consensus. After pilot-testing by research team members at their own sites, the survey was refined for item clarity, structural design, and length. We chose to administer surveys through phone interviews over a traditional distribution due to anticipated variability in work models. The research team discussed how each question should be asked, and responses were clarified to maintain consistency.

Survey Administration

Given the absence of a national registry or database for community-based PHM programs, study participation was solicited through an invitation posted on the American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Hospital Medicine (AAP SOHM) Listserv and the AAP SOHM Community Hospitalist Listserv in May 2018. Invitations were posted twice at two weeks apart. Each research team member completed 6-19 interviews. Responses to survey questions were recorded in REDCap, a secure, web-based data capture instrument.8

Participating in the study was considered implied consent, and participants did not receive a monetary incentive, although respondents were offered deidentified survey data for participation. The study was exempted through the University of Chicago Institutional Review Board.

Data Analysis

Employers were dichotomized as community hospital employer (including primary community hospital employment/private organization) or noncommunity hospital employer (including children’s/university hospital employment or school of medicine). Descriptive statistics were reported to compare the demographics of two employer groups. P values were calculated using two-sample t-tests for the continuous variables and chi-square or Fisher-exact tests for the categorical variables. Mann–Whitney U-test was performed for continuous variables without normality. Analyses were performed using the R Statistical Programming Language (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), version 3.4.3.

RESULTS

Participation and Program Characteristics

We interviewed 70 community-based PHM site directors representing programs across 29 states (Table 1) and five geographic regions: Midwest (34.3%), Northeast (11.4%), Southeast (15.7%), Southwest (4.3%), and West (34.3%). Employer models varied across groups, with more noncommunity hospital employers (57%) than community hospital employers (43%). The top three services covered by pediatric hospitalists were pediatric inpatient or observation bed admissions (97%), emergency department consults (89%), and general newborns (67%). PHM programs also provided coverage for other services, including newborn deliveries (43%), Special Care Nursery/Level II Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (41%), step-down unit (20%), and mental health units (13%). About 59% of programs provided education for family medicine residents, 36% were for pediatric residents, and 70% worked with advanced practice providers. The majority of programs (70%) provided in-house coverage overnight.

Clinical Work Expectations and Employer Model

Clinical work expectations varied broadly across programs (Table 2). The median expected hours for a 1.0 FTE was 1,882 hours per year (interquartile range [IQR] 1,805, 2,016), and the median expected weekend coverage/year (defined as covering two days or two nights of the weekend) was 21 (IQR 14, 24). Most programs did not expand staff coverage based on seasonality (73%), and less than 20% of programs operated with a census cap. Median support for nondirect patient care activities was 4% (IQR 0,10) of a program’s total FTE (ie, a 5.0 FTE program would have 0.20 FTE support). Programs with community hospital employers had an 8% higher expectation of 1.0 FTE hours/year (P = .01) and viewed an appropriate pediatric morning census as 20% higher (P = .01; Table 2).

Program Sustainability

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this study is the first to describe clinical work models exclusively for pediatric community hospitalist programs. We found that expectations for clinical FTE hours, weekend coverage, appropriate morning census, support for nondirect patient care activities, and perception of sustainability varied broadly across programs. The only variable affecting some of these differences was employer model, with those employed by a community hospital employer having a higher expectation for hours/year and appropriate morning pediatric census than those employed by noncommunity hospital employers.

With a growing emphasis on physician burnout and career satisfaction,9-11 understanding the characteristics of community hospital work settings is critical for identifying and building sustainable employment models. Previous studies have identified that the balance of clinical and nonclinical responsibilities and the setting of community versus university-based programs are major contributors to burnout and career satisfaction.9,11 Interestingly, although community hospital-based programs have limited FTE for nondirect patient care activities, we found that a higher percentage of program site directors perceived their program models as sustainable when compared with university-based programs in prior research (63% versus 50%).6 Elucidating why community hospital PHM programs are perceived as more sustainable provides an opportunity for future research. Potential reasons may include fewer academic requirements for promotion or an increased connection to a local community.

We also found that the employer model had a statistically significant impact on expected FTE hours per year but not on perception of sustainability. Programs employed by community hospitals worked 8% more hours per year than those employed by noncommunity hospital employers and accepted a higher morning pediatric census. This variation in hours and census level appropriateness is likely multifactorial, potentially from higher nonclinical expectations for promotion (eg, academic or scholarly production) at school of medicine or children’s hospital employed programs versus limited reimbursement for administrative responsibilities within community hospital employment models.

There are several potential next steps for our findings. As our data are the first attempt (to our knowledge) at describing the current practice and expectations exclusively within community hospital programs, this study can be used as a starting point for the development of workload expectation standards. Increasing transparency nationally for individual community programs potentially promotes discussions around burnout and attrition. Having objective data to compare program models may assist in advocating with local hospital leadership for restructuring that better aligns with national norms.

Our study has several limitations. First, our sampling frame was based upon a self-selection of program directors. This may have led to a biased representation of programs with higher workloads motivated to develop a standard to compare with other programs, which may have potentially led to an overestimation of hours. Second, without a registry or database for community-based pediatric hospitalist programs, we do not know the percentage of community-based programs that our sample represents. Although our results cannot speak for all community PHM programs, we attempted to mitigate nonresponse bias through the breadth of programs represented, which spanned 29 states, five geographic regions, and teaching and nonteaching programs. The interview-based method for data collection allowed the research team to clarify questions and responses across sites, thereby improving the quality and consistency of the data for the represented study sample. Finally, other factors possibly contributed to sustainability that we did not address in this study, such as programs that are dependent on billable encounters as part of their salary support.

CONCLUSION

As a newly recognized subspecialty, creating a reference for community-based program leaders to determine and discuss individual models and expectations with hospital administrators may help address programmatic sustainability. It may also allow for the analysis of long-term career satisfaction and longevity within community PHM programs based on workload. Future studies should further explore root causes for workload discrepancies between community and university employed programs along with establishing potential standards for PHM program development.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Stanford School of Medicine Quantitative Sciences Unit staff for their assistance in statistical analysis.

Disclosure

The authors have nothing to disclose.

1. Robert MW, Lee G. Zero to 50,000—The 20th anniversary of the hospitalist. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(11):1009-1011. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1607958.

2. Gosdin C, Simmons J, Yau C, Sucharew H, Carlson D, Paciorkowski N. Survey of academic pediatric hospitalist programs in the US: organizational, administrative, and financial factors. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(6):285-291. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2020.

3. Paul DH, Jennifer D, Elizabeth R, et al. Proposed dashboard for pediatric hospital medicine groups. Hosp Pediatr. 2012;2(2):59-68. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2012-0004

4. Gary LF, Kathryn B, Kamilah N, Indu L. Characteristics of the pediatric hospitalist workforce: its roles and work environment. Pediatrics 2007;120(1):33-39. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2007-0304

5. Leyenaar JK, Frintner MP. Graduating pediatric residents entering the hospital medicine workforce. 2006-2015. Acad Pediatr. 2018;18(2):200-207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2017.05.001.

6. Fromme HB, Chen CO, Fine BR, Gosdin C, Shaughnessy EE. Pediatric hospitalist workload and sustainability in university-based programs: results from a national interview-based survey. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(10):702-705. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2977.

7. Leyenaar JK, Ralston SL, Shieh MS, Pekow PS, Mangione-Smith R, Lindenauer PK. Epidemiology of pediatric hospitalizations at general hospitals and freestanding children’s hospitals in the United States. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(11):743-749. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2624.

8. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377-381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010.

9. Laurie AP, Aisha BD, Mary CO. Association between practice setting and pediatric hospitalist career satisfaction. Hosp Pediatr. 2013;3(3):285-291. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2012-0085

10. Hinami K, Whelan CT, Wolosin RJ, Miller JA, Wetterneck TB. Worklife and satisfaction of hospitalists: toward flourishing careers. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;27(1):28-36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-011-1780-z.

11. Hinami K, Whelan CT, Miller JA, Wolosin RJ, Wetterneck TB. Job characteristics, satisfaction, and burnout across hospitalist practice models. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(5):402-410. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.1907

As a newly recognized specialty, pediatric hospital medicine (PHM) continues to expand and diversify.1 Pediatric hospitalists care for children in hospitals ranging from small, rural community hospitals to large, free-standing quaternary children’s hospitals.2-4 In addition, more than 10% of graduating pediatric residents are seeking future careers within PHM.5

In 2018, Fromme et al. published a study describing clinical workload for pediatric hospitalists within university-based settings.6 They characterized the diversity of work models and programmatic sustainability but limited the study to university-based programs. With over half of children receiving care within community hospitals,7 workforce patterns for community-based pediatric hospitalists should be characterized to maximize sustainability and minimize attrition across the field.

In this study, we describe programmatic variability in clinical work expectations of 70 community-based PHM programs. We aimed to describe existing work models and expectations of community-based program leaders as they relate to their unique clinical setting.

METHODS

We conducted a cross-sectional survey of community-based PHM site directors through structured interviews. Community hospital programs were self-defined by the study participants, although typically defined as general hospitals that admit pediatric patients and are not free-standing or children’s hospitals within a general hospital. Survey respondents were asked to answer questions only reflecting expectations at their community hospital.

Survey Design and Content

Building from a tool used by Fromme et al.6 we created a 12-question structured interview questionnaire focused on three areas: (1) full-time employment (FTE) metrics including definitions of a 1.0 FTE, “typical” shifts, and weekend responsibilities; (2) work volume including census parameters, service-line coverage expectations, back-up systems, and overnight call responsibilities; and (3) programmatic model including sense of sustainability (eg, minimizing burnout and attrition), support for activities such as administrative or research time, and employer model (Appendix).

We modified the survey through research team consensus. After pilot-testing by research team members at their own sites, the survey was refined for item clarity, structural design, and length. We chose to administer surveys through phone interviews over a traditional distribution due to anticipated variability in work models. The research team discussed how each question should be asked, and responses were clarified to maintain consistency.

Survey Administration

Given the absence of a national registry or database for community-based PHM programs, study participation was solicited through an invitation posted on the American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Hospital Medicine (AAP SOHM) Listserv and the AAP SOHM Community Hospitalist Listserv in May 2018. Invitations were posted twice at two weeks apart. Each research team member completed 6-19 interviews. Responses to survey questions were recorded in REDCap, a secure, web-based data capture instrument.8

Participating in the study was considered implied consent, and participants did not receive a monetary incentive, although respondents were offered deidentified survey data for participation. The study was exempted through the University of Chicago Institutional Review Board.

Data Analysis

Employers were dichotomized as community hospital employer (including primary community hospital employment/private organization) or noncommunity hospital employer (including children’s/university hospital employment or school of medicine). Descriptive statistics were reported to compare the demographics of two employer groups. P values were calculated using two-sample t-tests for the continuous variables and chi-square or Fisher-exact tests for the categorical variables. Mann–Whitney U-test was performed for continuous variables without normality. Analyses were performed using the R Statistical Programming Language (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), version 3.4.3.

RESULTS

Participation and Program Characteristics

We interviewed 70 community-based PHM site directors representing programs across 29 states (Table 1) and five geographic regions: Midwest (34.3%), Northeast (11.4%), Southeast (15.7%), Southwest (4.3%), and West (34.3%). Employer models varied across groups, with more noncommunity hospital employers (57%) than community hospital employers (43%). The top three services covered by pediatric hospitalists were pediatric inpatient or observation bed admissions (97%), emergency department consults (89%), and general newborns (67%). PHM programs also provided coverage for other services, including newborn deliveries (43%), Special Care Nursery/Level II Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (41%), step-down unit (20%), and mental health units (13%). About 59% of programs provided education for family medicine residents, 36% were for pediatric residents, and 70% worked with advanced practice providers. The majority of programs (70%) provided in-house coverage overnight.

Clinical Work Expectations and Employer Model

Clinical work expectations varied broadly across programs (Table 2). The median expected hours for a 1.0 FTE was 1,882 hours per year (interquartile range [IQR] 1,805, 2,016), and the median expected weekend coverage/year (defined as covering two days or two nights of the weekend) was 21 (IQR 14, 24). Most programs did not expand staff coverage based on seasonality (73%), and less than 20% of programs operated with a census cap. Median support for nondirect patient care activities was 4% (IQR 0,10) of a program’s total FTE (ie, a 5.0 FTE program would have 0.20 FTE support). Programs with community hospital employers had an 8% higher expectation of 1.0 FTE hours/year (P = .01) and viewed an appropriate pediatric morning census as 20% higher (P = .01; Table 2).

Program Sustainability

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this study is the first to describe clinical work models exclusively for pediatric community hospitalist programs. We found that expectations for clinical FTE hours, weekend coverage, appropriate morning census, support for nondirect patient care activities, and perception of sustainability varied broadly across programs. The only variable affecting some of these differences was employer model, with those employed by a community hospital employer having a higher expectation for hours/year and appropriate morning pediatric census than those employed by noncommunity hospital employers.

With a growing emphasis on physician burnout and career satisfaction,9-11 understanding the characteristics of community hospital work settings is critical for identifying and building sustainable employment models. Previous studies have identified that the balance of clinical and nonclinical responsibilities and the setting of community versus university-based programs are major contributors to burnout and career satisfaction.9,11 Interestingly, although community hospital-based programs have limited FTE for nondirect patient care activities, we found that a higher percentage of program site directors perceived their program models as sustainable when compared with university-based programs in prior research (63% versus 50%).6 Elucidating why community hospital PHM programs are perceived as more sustainable provides an opportunity for future research. Potential reasons may include fewer academic requirements for promotion or an increased connection to a local community.

We also found that the employer model had a statistically significant impact on expected FTE hours per year but not on perception of sustainability. Programs employed by community hospitals worked 8% more hours per year than those employed by noncommunity hospital employers and accepted a higher morning pediatric census. This variation in hours and census level appropriateness is likely multifactorial, potentially from higher nonclinical expectations for promotion (eg, academic or scholarly production) at school of medicine or children’s hospital employed programs versus limited reimbursement for administrative responsibilities within community hospital employment models.

There are several potential next steps for our findings. As our data are the first attempt (to our knowledge) at describing the current practice and expectations exclusively within community hospital programs, this study can be used as a starting point for the development of workload expectation standards. Increasing transparency nationally for individual community programs potentially promotes discussions around burnout and attrition. Having objective data to compare program models may assist in advocating with local hospital leadership for restructuring that better aligns with national norms.

Our study has several limitations. First, our sampling frame was based upon a self-selection of program directors. This may have led to a biased representation of programs with higher workloads motivated to develop a standard to compare with other programs, which may have potentially led to an overestimation of hours. Second, without a registry or database for community-based pediatric hospitalist programs, we do not know the percentage of community-based programs that our sample represents. Although our results cannot speak for all community PHM programs, we attempted to mitigate nonresponse bias through the breadth of programs represented, which spanned 29 states, five geographic regions, and teaching and nonteaching programs. The interview-based method for data collection allowed the research team to clarify questions and responses across sites, thereby improving the quality and consistency of the data for the represented study sample. Finally, other factors possibly contributed to sustainability that we did not address in this study, such as programs that are dependent on billable encounters as part of their salary support.

CONCLUSION

As a newly recognized subspecialty, creating a reference for community-based program leaders to determine and discuss individual models and expectations with hospital administrators may help address programmatic sustainability. It may also allow for the analysis of long-term career satisfaction and longevity within community PHM programs based on workload. Future studies should further explore root causes for workload discrepancies between community and university employed programs along with establishing potential standards for PHM program development.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Stanford School of Medicine Quantitative Sciences Unit staff for their assistance in statistical analysis.

Disclosure

The authors have nothing to disclose.

As a newly recognized specialty, pediatric hospital medicine (PHM) continues to expand and diversify.1 Pediatric hospitalists care for children in hospitals ranging from small, rural community hospitals to large, free-standing quaternary children’s hospitals.2-4 In addition, more than 10% of graduating pediatric residents are seeking future careers within PHM.5

In 2018, Fromme et al. published a study describing clinical workload for pediatric hospitalists within university-based settings.6 They characterized the diversity of work models and programmatic sustainability but limited the study to university-based programs. With over half of children receiving care within community hospitals,7 workforce patterns for community-based pediatric hospitalists should be characterized to maximize sustainability and minimize attrition across the field.

In this study, we describe programmatic variability in clinical work expectations of 70 community-based PHM programs. We aimed to describe existing work models and expectations of community-based program leaders as they relate to their unique clinical setting.

METHODS

We conducted a cross-sectional survey of community-based PHM site directors through structured interviews. Community hospital programs were self-defined by the study participants, although typically defined as general hospitals that admit pediatric patients and are not free-standing or children’s hospitals within a general hospital. Survey respondents were asked to answer questions only reflecting expectations at their community hospital.

Survey Design and Content

Building from a tool used by Fromme et al.6 we created a 12-question structured interview questionnaire focused on three areas: (1) full-time employment (FTE) metrics including definitions of a 1.0 FTE, “typical” shifts, and weekend responsibilities; (2) work volume including census parameters, service-line coverage expectations, back-up systems, and overnight call responsibilities; and (3) programmatic model including sense of sustainability (eg, minimizing burnout and attrition), support for activities such as administrative or research time, and employer model (Appendix).

We modified the survey through research team consensus. After pilot-testing by research team members at their own sites, the survey was refined for item clarity, structural design, and length. We chose to administer surveys through phone interviews over a traditional distribution due to anticipated variability in work models. The research team discussed how each question should be asked, and responses were clarified to maintain consistency.

Survey Administration

Given the absence of a national registry or database for community-based PHM programs, study participation was solicited through an invitation posted on the American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Hospital Medicine (AAP SOHM) Listserv and the AAP SOHM Community Hospitalist Listserv in May 2018. Invitations were posted twice at two weeks apart. Each research team member completed 6-19 interviews. Responses to survey questions were recorded in REDCap, a secure, web-based data capture instrument.8

Participating in the study was considered implied consent, and participants did not receive a monetary incentive, although respondents were offered deidentified survey data for participation. The study was exempted through the University of Chicago Institutional Review Board.

Data Analysis

Employers were dichotomized as community hospital employer (including primary community hospital employment/private organization) or noncommunity hospital employer (including children’s/university hospital employment or school of medicine). Descriptive statistics were reported to compare the demographics of two employer groups. P values were calculated using two-sample t-tests for the continuous variables and chi-square or Fisher-exact tests for the categorical variables. Mann–Whitney U-test was performed for continuous variables without normality. Analyses were performed using the R Statistical Programming Language (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), version 3.4.3.

RESULTS

Participation and Program Characteristics

We interviewed 70 community-based PHM site directors representing programs across 29 states (Table 1) and five geographic regions: Midwest (34.3%), Northeast (11.4%), Southeast (15.7%), Southwest (4.3%), and West (34.3%). Employer models varied across groups, with more noncommunity hospital employers (57%) than community hospital employers (43%). The top three services covered by pediatric hospitalists were pediatric inpatient or observation bed admissions (97%), emergency department consults (89%), and general newborns (67%). PHM programs also provided coverage for other services, including newborn deliveries (43%), Special Care Nursery/Level II Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (41%), step-down unit (20%), and mental health units (13%). About 59% of programs provided education for family medicine residents, 36% were for pediatric residents, and 70% worked with advanced practice providers. The majority of programs (70%) provided in-house coverage overnight.

Clinical Work Expectations and Employer Model

Clinical work expectations varied broadly across programs (Table 2). The median expected hours for a 1.0 FTE was 1,882 hours per year (interquartile range [IQR] 1,805, 2,016), and the median expected weekend coverage/year (defined as covering two days or two nights of the weekend) was 21 (IQR 14, 24). Most programs did not expand staff coverage based on seasonality (73%), and less than 20% of programs operated with a census cap. Median support for nondirect patient care activities was 4% (IQR 0,10) of a program’s total FTE (ie, a 5.0 FTE program would have 0.20 FTE support). Programs with community hospital employers had an 8% higher expectation of 1.0 FTE hours/year (P = .01) and viewed an appropriate pediatric morning census as 20% higher (P = .01; Table 2).

Program Sustainability

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this study is the first to describe clinical work models exclusively for pediatric community hospitalist programs. We found that expectations for clinical FTE hours, weekend coverage, appropriate morning census, support for nondirect patient care activities, and perception of sustainability varied broadly across programs. The only variable affecting some of these differences was employer model, with those employed by a community hospital employer having a higher expectation for hours/year and appropriate morning pediatric census than those employed by noncommunity hospital employers.

With a growing emphasis on physician burnout and career satisfaction,9-11 understanding the characteristics of community hospital work settings is critical for identifying and building sustainable employment models. Previous studies have identified that the balance of clinical and nonclinical responsibilities and the setting of community versus university-based programs are major contributors to burnout and career satisfaction.9,11 Interestingly, although community hospital-based programs have limited FTE for nondirect patient care activities, we found that a higher percentage of program site directors perceived their program models as sustainable when compared with university-based programs in prior research (63% versus 50%).6 Elucidating why community hospital PHM programs are perceived as more sustainable provides an opportunity for future research. Potential reasons may include fewer academic requirements for promotion or an increased connection to a local community.

We also found that the employer model had a statistically significant impact on expected FTE hours per year but not on perception of sustainability. Programs employed by community hospitals worked 8% more hours per year than those employed by noncommunity hospital employers and accepted a higher morning pediatric census. This variation in hours and census level appropriateness is likely multifactorial, potentially from higher nonclinical expectations for promotion (eg, academic or scholarly production) at school of medicine or children’s hospital employed programs versus limited reimbursement for administrative responsibilities within community hospital employment models.

There are several potential next steps for our findings. As our data are the first attempt (to our knowledge) at describing the current practice and expectations exclusively within community hospital programs, this study can be used as a starting point for the development of workload expectation standards. Increasing transparency nationally for individual community programs potentially promotes discussions around burnout and attrition. Having objective data to compare program models may assist in advocating with local hospital leadership for restructuring that better aligns with national norms.

Our study has several limitations. First, our sampling frame was based upon a self-selection of program directors. This may have led to a biased representation of programs with higher workloads motivated to develop a standard to compare with other programs, which may have potentially led to an overestimation of hours. Second, without a registry or database for community-based pediatric hospitalist programs, we do not know the percentage of community-based programs that our sample represents. Although our results cannot speak for all community PHM programs, we attempted to mitigate nonresponse bias through the breadth of programs represented, which spanned 29 states, five geographic regions, and teaching and nonteaching programs. The interview-based method for data collection allowed the research team to clarify questions and responses across sites, thereby improving the quality and consistency of the data for the represented study sample. Finally, other factors possibly contributed to sustainability that we did not address in this study, such as programs that are dependent on billable encounters as part of their salary support.

CONCLUSION

As a newly recognized subspecialty, creating a reference for community-based program leaders to determine and discuss individual models and expectations with hospital administrators may help address programmatic sustainability. It may also allow for the analysis of long-term career satisfaction and longevity within community PHM programs based on workload. Future studies should further explore root causes for workload discrepancies between community and university employed programs along with establishing potential standards for PHM program development.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Stanford School of Medicine Quantitative Sciences Unit staff for their assistance in statistical analysis.

Disclosure

The authors have nothing to disclose.

1. Robert MW, Lee G. Zero to 50,000—The 20th anniversary of the hospitalist. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(11):1009-1011. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1607958.

2. Gosdin C, Simmons J, Yau C, Sucharew H, Carlson D, Paciorkowski N. Survey of academic pediatric hospitalist programs in the US: organizational, administrative, and financial factors. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(6):285-291. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2020.

3. Paul DH, Jennifer D, Elizabeth R, et al. Proposed dashboard for pediatric hospital medicine groups. Hosp Pediatr. 2012;2(2):59-68. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2012-0004

4. Gary LF, Kathryn B, Kamilah N, Indu L. Characteristics of the pediatric hospitalist workforce: its roles and work environment. Pediatrics 2007;120(1):33-39. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2007-0304

5. Leyenaar JK, Frintner MP. Graduating pediatric residents entering the hospital medicine workforce. 2006-2015. Acad Pediatr. 2018;18(2):200-207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2017.05.001.

6. Fromme HB, Chen CO, Fine BR, Gosdin C, Shaughnessy EE. Pediatric hospitalist workload and sustainability in university-based programs: results from a national interview-based survey. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(10):702-705. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2977.

7. Leyenaar JK, Ralston SL, Shieh MS, Pekow PS, Mangione-Smith R, Lindenauer PK. Epidemiology of pediatric hospitalizations at general hospitals and freestanding children’s hospitals in the United States. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(11):743-749. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2624.

8. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377-381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010.

9. Laurie AP, Aisha BD, Mary CO. Association between practice setting and pediatric hospitalist career satisfaction. Hosp Pediatr. 2013;3(3):285-291. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2012-0085

10. Hinami K, Whelan CT, Wolosin RJ, Miller JA, Wetterneck TB. Worklife and satisfaction of hospitalists: toward flourishing careers. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;27(1):28-36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-011-1780-z.

11. Hinami K, Whelan CT, Miller JA, Wolosin RJ, Wetterneck TB. Job characteristics, satisfaction, and burnout across hospitalist practice models. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(5):402-410. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.1907

1. Robert MW, Lee G. Zero to 50,000—The 20th anniversary of the hospitalist. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(11):1009-1011. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1607958.

2. Gosdin C, Simmons J, Yau C, Sucharew H, Carlson D, Paciorkowski N. Survey of academic pediatric hospitalist programs in the US: organizational, administrative, and financial factors. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(6):285-291. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2020.

3. Paul DH, Jennifer D, Elizabeth R, et al. Proposed dashboard for pediatric hospital medicine groups. Hosp Pediatr. 2012;2(2):59-68. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2012-0004

4. Gary LF, Kathryn B, Kamilah N, Indu L. Characteristics of the pediatric hospitalist workforce: its roles and work environment. Pediatrics 2007;120(1):33-39. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2007-0304

5. Leyenaar JK, Frintner MP. Graduating pediatric residents entering the hospital medicine workforce. 2006-2015. Acad Pediatr. 2018;18(2):200-207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2017.05.001.

6. Fromme HB, Chen CO, Fine BR, Gosdin C, Shaughnessy EE. Pediatric hospitalist workload and sustainability in university-based programs: results from a national interview-based survey. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(10):702-705. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2977.

7. Leyenaar JK, Ralston SL, Shieh MS, Pekow PS, Mangione-Smith R, Lindenauer PK. Epidemiology of pediatric hospitalizations at general hospitals and freestanding children’s hospitals in the United States. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(11):743-749. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2624.

8. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377-381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010.

9. Laurie AP, Aisha BD, Mary CO. Association between practice setting and pediatric hospitalist career satisfaction. Hosp Pediatr. 2013;3(3):285-291. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2012-0085

10. Hinami K, Whelan CT, Wolosin RJ, Miller JA, Wetterneck TB. Worklife and satisfaction of hospitalists: toward flourishing careers. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;27(1):28-36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-011-1780-z.

11. Hinami K, Whelan CT, Miller JA, Wolosin RJ, Wetterneck TB. Job characteristics, satisfaction, and burnout across hospitalist practice models. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(5):402-410. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.1907

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine

In Reply to: “Practical Application of Pediatric Hospital Medicine Workforce Data: In Reference to ‘Pediatric Hospitalist Workload and Sustainability in University-Based Programs: Results from a National Interview-Based Survey’”

We appreciate the query by Drs. Douglas and Wilson. We hereby supply additional information that is critical for creating and administering sustainable staffing models.

For programs with a census cap, the majority cited 16 or fewer patients as the trigger for that cap. Nearly all programs with back-up used a census of 16 or fewer. Over 80% of programs cited a “safe 7

Regarding clinical weighting of nights, nighttime shifts were often more heavily weighted than day shifts, but approaches to weighting varied and have not been validated. Alternate staffing models for overnight pager calls varied greatly by individual program.

This is a time of significant growth for pediatric hospital medicine, and national workforce data are essential to hospitalists, administrators, and most importantly, patients. Our study1 provides pediatric hospital medicine leaders with data for discussions regarding appropriate FTE and staffing model considerations. The insights generated by our study are particularly relevant in expanding programs and solving problems related to recruitment and retention.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

1. Fromme HB, Chen C, Fine B, Gosdin C, Shaughnessy E. Pediatric hospitalist workload and sustainability in university-based programs: Results from a national interview-based survey. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(10):702-705. PubMed

We appreciate the query by Drs. Douglas and Wilson. We hereby supply additional information that is critical for creating and administering sustainable staffing models.

For programs with a census cap, the majority cited 16 or fewer patients as the trigger for that cap. Nearly all programs with back-up used a census of 16 or fewer. Over 80% of programs cited a “safe 7

Regarding clinical weighting of nights, nighttime shifts were often more heavily weighted than day shifts, but approaches to weighting varied and have not been validated. Alternate staffing models for overnight pager calls varied greatly by individual program.

This is a time of significant growth for pediatric hospital medicine, and national workforce data are essential to hospitalists, administrators, and most importantly, patients. Our study1 provides pediatric hospital medicine leaders with data for discussions regarding appropriate FTE and staffing model considerations. The insights generated by our study are particularly relevant in expanding programs and solving problems related to recruitment and retention.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

We appreciate the query by Drs. Douglas and Wilson. We hereby supply additional information that is critical for creating and administering sustainable staffing models.

For programs with a census cap, the majority cited 16 or fewer patients as the trigger for that cap. Nearly all programs with back-up used a census of 16 or fewer. Over 80% of programs cited a “safe 7

Regarding clinical weighting of nights, nighttime shifts were often more heavily weighted than day shifts, but approaches to weighting varied and have not been validated. Alternate staffing models for overnight pager calls varied greatly by individual program.

This is a time of significant growth for pediatric hospital medicine, and national workforce data are essential to hospitalists, administrators, and most importantly, patients. Our study1 provides pediatric hospital medicine leaders with data for discussions regarding appropriate FTE and staffing model considerations. The insights generated by our study are particularly relevant in expanding programs and solving problems related to recruitment and retention.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

1. Fromme HB, Chen C, Fine B, Gosdin C, Shaughnessy E. Pediatric hospitalist workload and sustainability in university-based programs: Results from a national interview-based survey. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(10):702-705. PubMed

1. Fromme HB, Chen C, Fine B, Gosdin C, Shaughnessy E. Pediatric hospitalist workload and sustainability in university-based programs: Results from a national interview-based survey. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(10):702-705. PubMed

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine

Pediatric Hospitalist Workload and Sustainability in University-Based Programs: Results from a National Interview-Based Survey

Pediatric hospital medicine (PHM) has grown tremendously since Wachter first described the specialty in 1996.1 Evidence of this growth is seen most markedly at the annual Pediatric Hospitalist Meeting, which has experienced an increase in attendance from 700 in 2013 to over 1,200 in 20172. Although the exact number of pediatric hospitalists in the United States is unknown, the American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Hospital Medicine (AAP SOHM) estimates that approximately 3,000-5,000 pediatric hospitalists currently practice in the country (personal communication).

As PHM programs have grown, variability has been reported in the roles, responsibilities, and workload among practitioners. Gosdin et al.3 reported large ranges and standard deviations in workload among full-time equivalents (FTEs) in academic PHM programs. However, this study’s ability to account for important nuances in program description was limited given that its data were obtained from an online survey.

Program variability, particularly regarding clinical hours and overall clinical burden (eg, in-house hours, census caps, and weekend coverage), is concerning given the well-reported increase in physician burn-out.4,5 Benchmarking data regarding the overall workload of pediatric hospitalists can offer nationally recognized guidance to assist program leaders in building successful programs. With this goal in mind, we sought to obtain data on university-based PHM programs to describe the current average workload for a 1.0 clinical FTE pediatric hospitalist and to assess the perceptions of program directors regarding the sustainability of the current workload.

METHODS

Study Design and Population

To obtain data with sufficient detail to compare programs, the authors, all of whom are practicing pediatric hospitalists at university-based programs, conducted structured interviews of PHM leaders in the United States. Given the absence of a single database for all PHM programs in the United States, the clinical division/program leaders of university-based programs were invited to participate through a post (with 2 reminders) to the AAP SOHM Listserv for PHM Division Leaders in May of 2017. To encourage participation, respondents were promised a summary of aggregate data. The study was exempted by the IRB of the University of Chicago.

Interview Content and Administration

The authors designed an 18-question structured interview regarding the current state of staffing in university-based PHM programs, with a focus on current descriptions of FTE, patient volume, and workload. Utilizing prior surveys3 as a basis, the authors iteratively determined the questions essential to understanding the programs’ current staffing models and ideal models. Considering the diversity of program models, interviews allowed for the clarification of questions and answers. A question regarding employment models was included to determine whether hospitalists were university-employed, hospital-employed, or a hybrid of the 2 modes of employment. The interview was also designed to establish a common language for work metrics (hours per year) for comparative purposes and to assess the perceived sustainability of the workload. Questions were provided in advance to provide respondents with sufficient time to collect data, thus increasing the accuracy of estimates. Respondents were asked, “Do you or your hospitalists have concerns about the sustainability of the model?” Sustainability was intentionally undefined to prevent limiting respondent perspective. For clarification, however, a follow-up comment that included examples was provided: “Faculty departures, reduction in total effort, and/or significant burn out.” The authors piloted the interview protocol by interviewing the division leaders of their own programs, and revisions were made based on feedback on feasibility and clarity. Finally, the AAP SOHM Subcommittee on Division Leaders provided feedback, which was incorporated.

Each author then interviewed 10-12 leaders (or designee) during May and June of 2017. Answers were recorded in REDCAP, an online survey and database tool that contains largely numeric data fields and has 1 field for narrative comments.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize interview responses, including median values with interquartile range. Data were compared between programs with models that were self-identified as either sustainable or unsustainable, with P-values in categorical variables from χ2-test or Fischer’s exact test and in continuous variables from Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

Spearman correlation coefficient was used to evaluate the association between average protected time (defined as the percent of funded time for nonclinical roles) and percentage working full-time clinical effort. It was also used to evaluate hours per year per 1.0 FTE and total weekends per year per 1.0 FTE and perceived sustainability. Linear regression was used to determine whether associations differed between groups identifying as sustainable versus unsustainable.

RESULTS

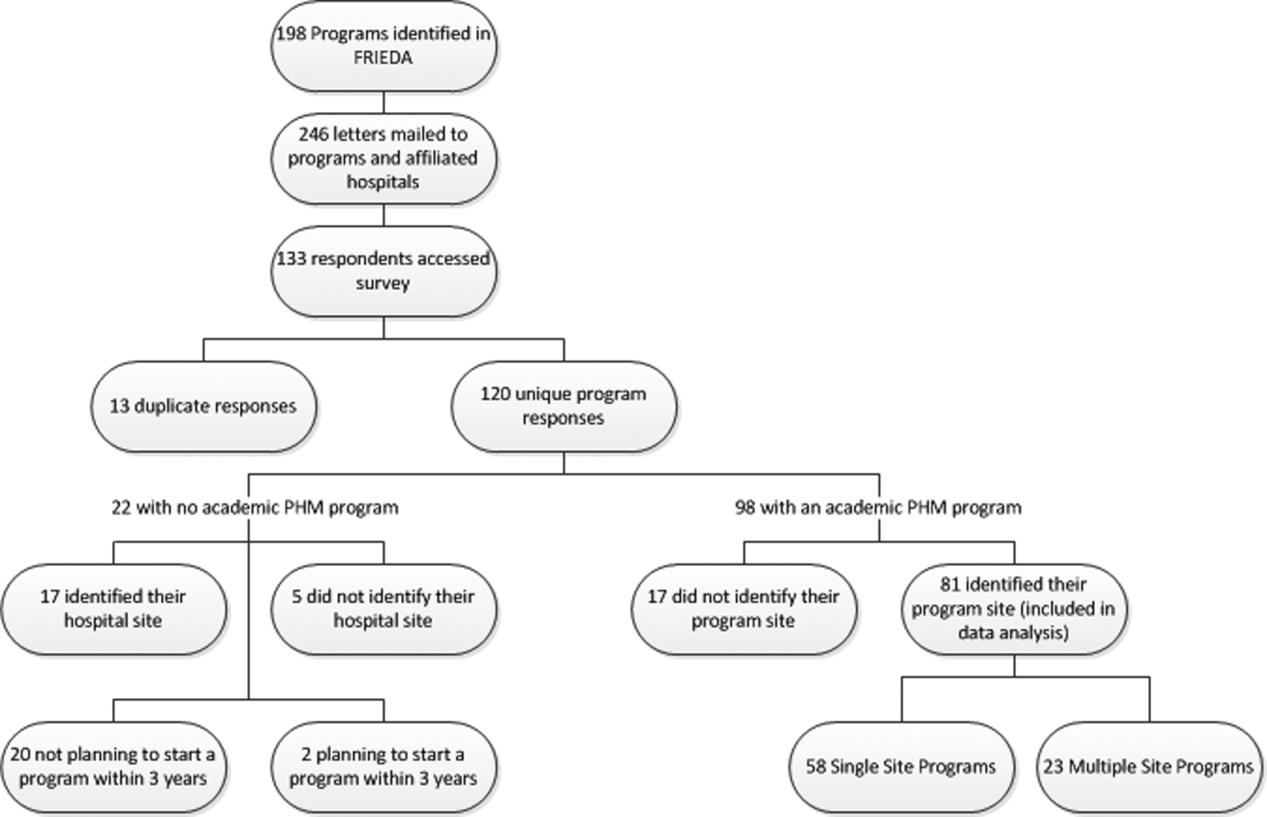

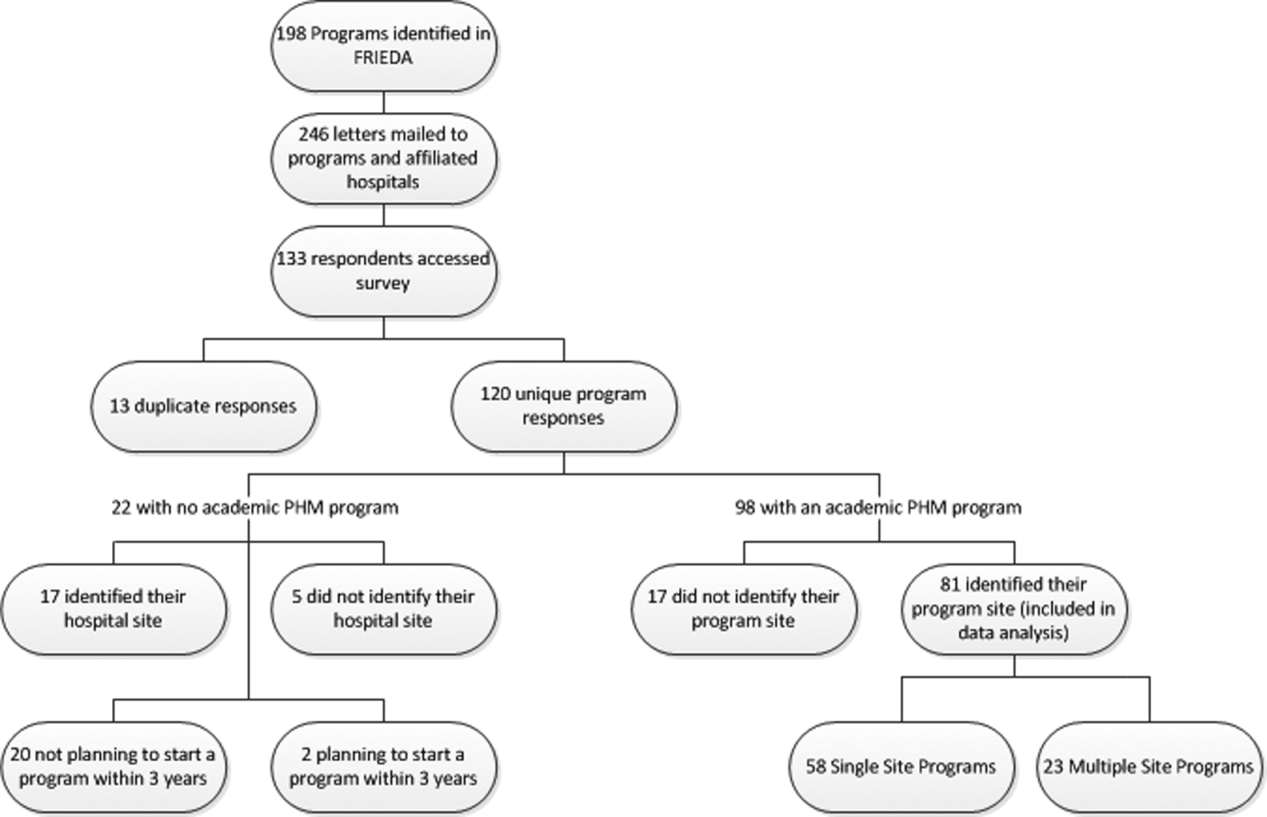

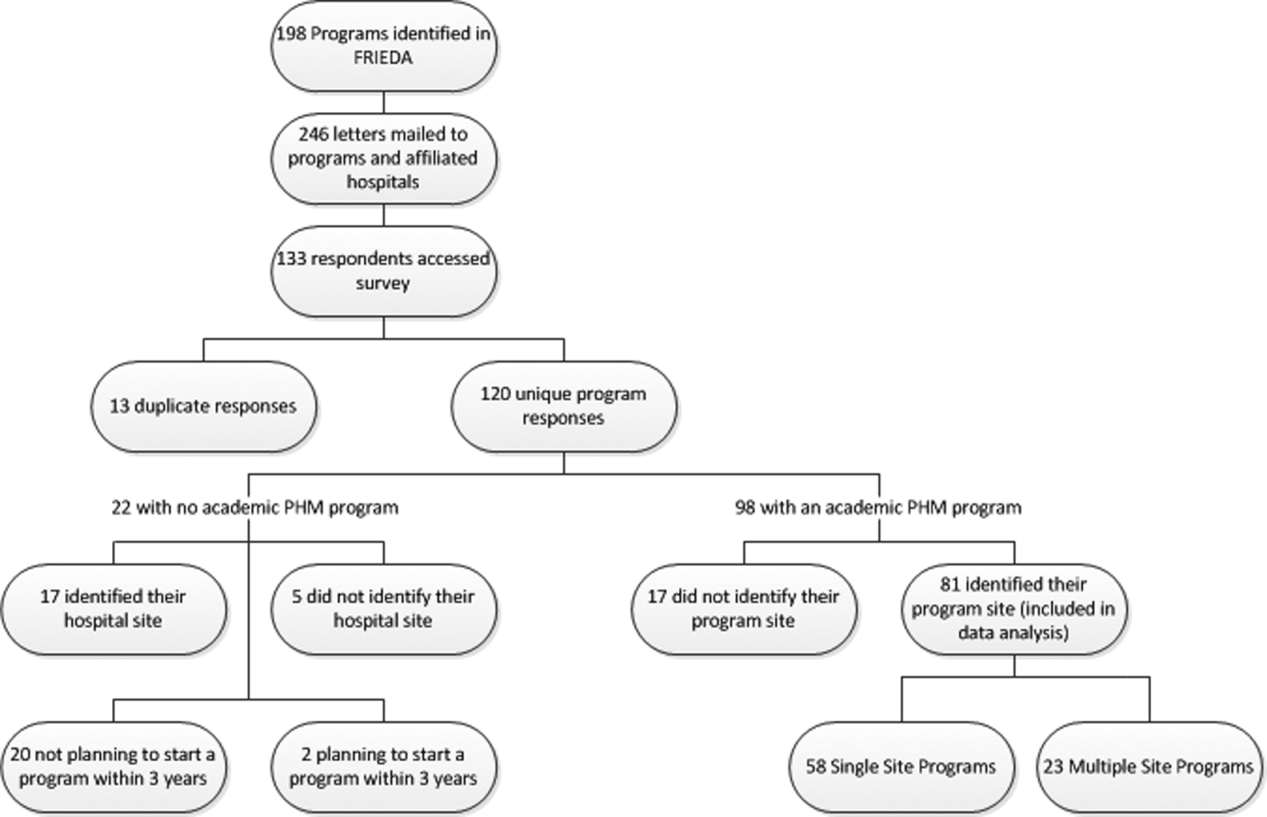

Participation and Program Characteristics

Administration

A wide variation was reported in the clinical time expected of a 1.0 FTE hospitalist. Clinical time for 1.0 FTE was defined as the amount of clinical service a full-time hospitalist is expected to complete in 12 months (Table 1). The median hours worked per year were 1800 (Interquartile range [IQR] 1620,1975; mean 1796). The median number of weekends worked per year was 15.0 (IQR 12.5, 21; mean 16.8). Only 30% of pediatric hospitalists were full-time clinicians, whereas the rest had protected time for nonclinical duties. The average amount of protected time was 20% per full-time hospitalist.

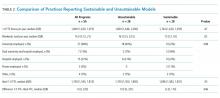

Sustainability and Ideal FTE

Half of the division leaders reported that they or their hospitalists have concerns about the sustainability of the current workload. Programs perceived as sustainable required significantly fewer weekends per year (13 vs. 16, P < .02; Table 2) than those perceived as unsustainable. University-employed programs were more likely to be perceived as unsustainable (64% unsustainable vs. 32% unsustainable, P < .048), whereas programs with other employment models were more likely to be perceived as sustainable (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

This study updates what has been previously reported about the structure and characteristics of university-based pediatric hospitalist programs.3 It also deepens our understanding of a relatively new field and the evolution of clinical coverage models. This evolution has been impacted by decreased resident work hours, increased patient complexity and acuity,6 and a broadened focus on care coordination and communication,7 while attempting to build and sustain a high-quality workforce.

This study is the first to use an interview-based method to determine the current PHM workload and to focus exclusively on university-based programs. Compared with the study by Gosdin et al,3 our study, which utilized interviews instead of surveys, was able to clarify questions and obtain workload data with a common language of hours per year. This approach allowed interviewees to incorporate subtleties, such as clinical vs. total FTE, in their responses. Our study found a slightly narrower range of clinical hours per year and extended the understanding of nonclinical duties by finding that university-based hospitalists have an average of 20% protected time from clinical duties.

In this study, we also explored the perceived sustainability of current clinical models and the ideal clinical model in hours per year. Half of respondents felt their current model was unsustainable. This result suggested that the field must continue to mitigate attrition and burnout.

Interestingly, the total number of clinical hours did not significantly differ in programs perceived to be unsustainable. Instead, a higher number of weekends worked and university employment were associated with lack of sustainability. We hypothesize that weekends have a disproportionate impact on work-life balance as compared with total hours, and that employment by a university may be a proxy for the increased academic and teaching demands of hospitalists without protected time. Future studies may better elucidate these findings and inform programmatic efforts to address sustainability.

Given that PHM is a relatively young field, considering the evolution of our clinical work model within the context of pediatric emergency medicine (PEM), a field that faces similar challenges in overnight and weekend staffing requirements, may be helpful. Gorelick et al.8 reported that total clinical work hours in PEM (combined academic and nonacademic programs) has decreased from 35.3 hours per week in 1998 to 26.7 in 2013. Extrapolating these numbers to an annual position with 5 weeks PTO/CME, the average PEM attending physician works 1254 clinical hours. These numbers demonstrate a marked difference compared with the average 1800 clinical work hours for PHM found in our study.

Although total hours trend lower in PEM, the authors noted continued challenges in sustainability with an estimated half of all PEM respondents indicating a plan to reduce hours or leave the field in the next 5 years and endorsing symptoms of burnout.6 These findings from PEM may motivate PHM leaders to be more aggressive in adjusting work models toward sustainability in the future.

Our study has several limitations. We utilized a convenience sampling approach that requires the voluntary participation of division directors. Although we had robust interest from respondents representing all major geographic areas, the respondent pool might conceivably over-represent those most interested in understanding and/or changing PHM clinical models. Overall, our sample size was smaller than that achieved by a survey approach. Nevertheless, this limitation was offset by controlling respondent type and clarifying questions, thus improving the quality of our obtained data.

CONCLUSION

This interview-based study of PHM directors describes the current state of clinical work models for university-based hospitalists. University-based PHM programs have similar mean and median total clinical hours per year. However, these hours are higher than those considered ideal by PHM directors, and many are concerned about the sustainability of current work models. Notably, programs that are university-employed or have higher weekends worked per year are more likely to be perceived as unsustainable. Future studies should explore differences between programs with sustainable work models and those with high levels of attrition and burnout.

Disclosures

The authors have no other conflicts to report.

Funding

A grant from the American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Hospital Medicine funded this study through the Subcommittee on Division and Program Leaders.

1. Wachter RM, Goldman L. The emerging role of “hospitalists” in the American health care system. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(7):514-517. DOI: 10.1056/NEJM199608153350713 PubMed

2. Chang W. Record Attendance, Key Issues Highlight Pediatric Hospital Medicine’s 10th Anniversary.

3. Gosdin C, Simmons J, Yau C, Sucharew H, Carlson D, Paciorkowski N. Survey of academic pediatric hospitalist programs in the US: organizational, administrative, and financial factors. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(6):285-291. DOI: 10.1002/jhm.2020. PubMed

4. Hinami K, Whelan CT, Wolosin RJ, Miller JA, Wetterneck TB. Worklife and satisfaction of hospitalists: toward flourishing careers. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;27(1):28-36. DOI: 10.1007/s11606-011-1780-z. PubMed

5. Hinami K, Whelan CT, Miller JA, Wolosin RJ, Wetterneck TB. Job characteristics, satisfaction, and burnout across hospitalist practice models. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(5):402-410. DOI: 10.1002/jhm.1907. PubMed

6. Barrett DJ, McGuinness GA, Cunha CA, et al. Pediatric hospital medicine: a proposed new subspecialty. Pediatrics. 2017;139(3):1-9. DOI: 10.1542/peds.2016-1823. PubMed

7. Cawley P, Deitelzweig S, Flores L, et al. The key principles and characteristics of an effective hospital medicine group: an assessment guide for hospitals and hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(2):123-128. DOI: 10.1002/jhm.2119. PubMed

8. Gorelick MH, Schremmer R, Ruch-Ross H, Radabaugh C, Selbst S. Current workforce characteristics and burnout in pediatric emergency medicine. Acad Emerg Med. 2016;23(1):48-54. DOI: 10.1111/acem.12845. PubMed

Pediatric hospital medicine (PHM) has grown tremendously since Wachter first described the specialty in 1996.1 Evidence of this growth is seen most markedly at the annual Pediatric Hospitalist Meeting, which has experienced an increase in attendance from 700 in 2013 to over 1,200 in 20172. Although the exact number of pediatric hospitalists in the United States is unknown, the American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Hospital Medicine (AAP SOHM) estimates that approximately 3,000-5,000 pediatric hospitalists currently practice in the country (personal communication).

As PHM programs have grown, variability has been reported in the roles, responsibilities, and workload among practitioners. Gosdin et al.3 reported large ranges and standard deviations in workload among full-time equivalents (FTEs) in academic PHM programs. However, this study’s ability to account for important nuances in program description was limited given that its data were obtained from an online survey.

Program variability, particularly regarding clinical hours and overall clinical burden (eg, in-house hours, census caps, and weekend coverage), is concerning given the well-reported increase in physician burn-out.4,5 Benchmarking data regarding the overall workload of pediatric hospitalists can offer nationally recognized guidance to assist program leaders in building successful programs. With this goal in mind, we sought to obtain data on university-based PHM programs to describe the current average workload for a 1.0 clinical FTE pediatric hospitalist and to assess the perceptions of program directors regarding the sustainability of the current workload.

METHODS

Study Design and Population

To obtain data with sufficient detail to compare programs, the authors, all of whom are practicing pediatric hospitalists at university-based programs, conducted structured interviews of PHM leaders in the United States. Given the absence of a single database for all PHM programs in the United States, the clinical division/program leaders of university-based programs were invited to participate through a post (with 2 reminders) to the AAP SOHM Listserv for PHM Division Leaders in May of 2017. To encourage participation, respondents were promised a summary of aggregate data. The study was exempted by the IRB of the University of Chicago.

Interview Content and Administration

The authors designed an 18-question structured interview regarding the current state of staffing in university-based PHM programs, with a focus on current descriptions of FTE, patient volume, and workload. Utilizing prior surveys3 as a basis, the authors iteratively determined the questions essential to understanding the programs’ current staffing models and ideal models. Considering the diversity of program models, interviews allowed for the clarification of questions and answers. A question regarding employment models was included to determine whether hospitalists were university-employed, hospital-employed, or a hybrid of the 2 modes of employment. The interview was also designed to establish a common language for work metrics (hours per year) for comparative purposes and to assess the perceived sustainability of the workload. Questions were provided in advance to provide respondents with sufficient time to collect data, thus increasing the accuracy of estimates. Respondents were asked, “Do you or your hospitalists have concerns about the sustainability of the model?” Sustainability was intentionally undefined to prevent limiting respondent perspective. For clarification, however, a follow-up comment that included examples was provided: “Faculty departures, reduction in total effort, and/or significant burn out.” The authors piloted the interview protocol by interviewing the division leaders of their own programs, and revisions were made based on feedback on feasibility and clarity. Finally, the AAP SOHM Subcommittee on Division Leaders provided feedback, which was incorporated.

Each author then interviewed 10-12 leaders (or designee) during May and June of 2017. Answers were recorded in REDCAP, an online survey and database tool that contains largely numeric data fields and has 1 field for narrative comments.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize interview responses, including median values with interquartile range. Data were compared between programs with models that were self-identified as either sustainable or unsustainable, with P-values in categorical variables from χ2-test or Fischer’s exact test and in continuous variables from Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

Spearman correlation coefficient was used to evaluate the association between average protected time (defined as the percent of funded time for nonclinical roles) and percentage working full-time clinical effort. It was also used to evaluate hours per year per 1.0 FTE and total weekends per year per 1.0 FTE and perceived sustainability. Linear regression was used to determine whether associations differed between groups identifying as sustainable versus unsustainable.

RESULTS

Participation and Program Characteristics

Administration

A wide variation was reported in the clinical time expected of a 1.0 FTE hospitalist. Clinical time for 1.0 FTE was defined as the amount of clinical service a full-time hospitalist is expected to complete in 12 months (Table 1). The median hours worked per year were 1800 (Interquartile range [IQR] 1620,1975; mean 1796). The median number of weekends worked per year was 15.0 (IQR 12.5, 21; mean 16.8). Only 30% of pediatric hospitalists were full-time clinicians, whereas the rest had protected time for nonclinical duties. The average amount of protected time was 20% per full-time hospitalist.

Sustainability and Ideal FTE

Half of the division leaders reported that they or their hospitalists have concerns about the sustainability of the current workload. Programs perceived as sustainable required significantly fewer weekends per year (13 vs. 16, P < .02; Table 2) than those perceived as unsustainable. University-employed programs were more likely to be perceived as unsustainable (64% unsustainable vs. 32% unsustainable, P < .048), whereas programs with other employment models were more likely to be perceived as sustainable (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

This study updates what has been previously reported about the structure and characteristics of university-based pediatric hospitalist programs.3 It also deepens our understanding of a relatively new field and the evolution of clinical coverage models. This evolution has been impacted by decreased resident work hours, increased patient complexity and acuity,6 and a broadened focus on care coordination and communication,7 while attempting to build and sustain a high-quality workforce.

This study is the first to use an interview-based method to determine the current PHM workload and to focus exclusively on university-based programs. Compared with the study by Gosdin et al,3 our study, which utilized interviews instead of surveys, was able to clarify questions and obtain workload data with a common language of hours per year. This approach allowed interviewees to incorporate subtleties, such as clinical vs. total FTE, in their responses. Our study found a slightly narrower range of clinical hours per year and extended the understanding of nonclinical duties by finding that university-based hospitalists have an average of 20% protected time from clinical duties.

In this study, we also explored the perceived sustainability of current clinical models and the ideal clinical model in hours per year. Half of respondents felt their current model was unsustainable. This result suggested that the field must continue to mitigate attrition and burnout.

Interestingly, the total number of clinical hours did not significantly differ in programs perceived to be unsustainable. Instead, a higher number of weekends worked and university employment were associated with lack of sustainability. We hypothesize that weekends have a disproportionate impact on work-life balance as compared with total hours, and that employment by a university may be a proxy for the increased academic and teaching demands of hospitalists without protected time. Future studies may better elucidate these findings and inform programmatic efforts to address sustainability.

Given that PHM is a relatively young field, considering the evolution of our clinical work model within the context of pediatric emergency medicine (PEM), a field that faces similar challenges in overnight and weekend staffing requirements, may be helpful. Gorelick et al.8 reported that total clinical work hours in PEM (combined academic and nonacademic programs) has decreased from 35.3 hours per week in 1998 to 26.7 in 2013. Extrapolating these numbers to an annual position with 5 weeks PTO/CME, the average PEM attending physician works 1254 clinical hours. These numbers demonstrate a marked difference compared with the average 1800 clinical work hours for PHM found in our study.

Although total hours trend lower in PEM, the authors noted continued challenges in sustainability with an estimated half of all PEM respondents indicating a plan to reduce hours or leave the field in the next 5 years and endorsing symptoms of burnout.6 These findings from PEM may motivate PHM leaders to be more aggressive in adjusting work models toward sustainability in the future.

Our study has several limitations. We utilized a convenience sampling approach that requires the voluntary participation of division directors. Although we had robust interest from respondents representing all major geographic areas, the respondent pool might conceivably over-represent those most interested in understanding and/or changing PHM clinical models. Overall, our sample size was smaller than that achieved by a survey approach. Nevertheless, this limitation was offset by controlling respondent type and clarifying questions, thus improving the quality of our obtained data.

CONCLUSION

This interview-based study of PHM directors describes the current state of clinical work models for university-based hospitalists. University-based PHM programs have similar mean and median total clinical hours per year. However, these hours are higher than those considered ideal by PHM directors, and many are concerned about the sustainability of current work models. Notably, programs that are university-employed or have higher weekends worked per year are more likely to be perceived as unsustainable. Future studies should explore differences between programs with sustainable work models and those with high levels of attrition and burnout.

Disclosures

The authors have no other conflicts to report.

Funding

A grant from the American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Hospital Medicine funded this study through the Subcommittee on Division and Program Leaders.

Pediatric hospital medicine (PHM) has grown tremendously since Wachter first described the specialty in 1996.1 Evidence of this growth is seen most markedly at the annual Pediatric Hospitalist Meeting, which has experienced an increase in attendance from 700 in 2013 to over 1,200 in 20172. Although the exact number of pediatric hospitalists in the United States is unknown, the American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Hospital Medicine (AAP SOHM) estimates that approximately 3,000-5,000 pediatric hospitalists currently practice in the country (personal communication).

As PHM programs have grown, variability has been reported in the roles, responsibilities, and workload among practitioners. Gosdin et al.3 reported large ranges and standard deviations in workload among full-time equivalents (FTEs) in academic PHM programs. However, this study’s ability to account for important nuances in program description was limited given that its data were obtained from an online survey.

Program variability, particularly regarding clinical hours and overall clinical burden (eg, in-house hours, census caps, and weekend coverage), is concerning given the well-reported increase in physician burn-out.4,5 Benchmarking data regarding the overall workload of pediatric hospitalists can offer nationally recognized guidance to assist program leaders in building successful programs. With this goal in mind, we sought to obtain data on university-based PHM programs to describe the current average workload for a 1.0 clinical FTE pediatric hospitalist and to assess the perceptions of program directors regarding the sustainability of the current workload.

METHODS

Study Design and Population

To obtain data with sufficient detail to compare programs, the authors, all of whom are practicing pediatric hospitalists at university-based programs, conducted structured interviews of PHM leaders in the United States. Given the absence of a single database for all PHM programs in the United States, the clinical division/program leaders of university-based programs were invited to participate through a post (with 2 reminders) to the AAP SOHM Listserv for PHM Division Leaders in May of 2017. To encourage participation, respondents were promised a summary of aggregate data. The study was exempted by the IRB of the University of Chicago.

Interview Content and Administration

The authors designed an 18-question structured interview regarding the current state of staffing in university-based PHM programs, with a focus on current descriptions of FTE, patient volume, and workload. Utilizing prior surveys3 as a basis, the authors iteratively determined the questions essential to understanding the programs’ current staffing models and ideal models. Considering the diversity of program models, interviews allowed for the clarification of questions and answers. A question regarding employment models was included to determine whether hospitalists were university-employed, hospital-employed, or a hybrid of the 2 modes of employment. The interview was also designed to establish a common language for work metrics (hours per year) for comparative purposes and to assess the perceived sustainability of the workload. Questions were provided in advance to provide respondents with sufficient time to collect data, thus increasing the accuracy of estimates. Respondents were asked, “Do you or your hospitalists have concerns about the sustainability of the model?” Sustainability was intentionally undefined to prevent limiting respondent perspective. For clarification, however, a follow-up comment that included examples was provided: “Faculty departures, reduction in total effort, and/or significant burn out.” The authors piloted the interview protocol by interviewing the division leaders of their own programs, and revisions were made based on feedback on feasibility and clarity. Finally, the AAP SOHM Subcommittee on Division Leaders provided feedback, which was incorporated.

Each author then interviewed 10-12 leaders (or designee) during May and June of 2017. Answers were recorded in REDCAP, an online survey and database tool that contains largely numeric data fields and has 1 field for narrative comments.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize interview responses, including median values with interquartile range. Data were compared between programs with models that were self-identified as either sustainable or unsustainable, with P-values in categorical variables from χ2-test or Fischer’s exact test and in continuous variables from Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

Spearman correlation coefficient was used to evaluate the association between average protected time (defined as the percent of funded time for nonclinical roles) and percentage working full-time clinical effort. It was also used to evaluate hours per year per 1.0 FTE and total weekends per year per 1.0 FTE and perceived sustainability. Linear regression was used to determine whether associations differed between groups identifying as sustainable versus unsustainable.

RESULTS

Participation and Program Characteristics

Administration

A wide variation was reported in the clinical time expected of a 1.0 FTE hospitalist. Clinical time for 1.0 FTE was defined as the amount of clinical service a full-time hospitalist is expected to complete in 12 months (Table 1). The median hours worked per year were 1800 (Interquartile range [IQR] 1620,1975; mean 1796). The median number of weekends worked per year was 15.0 (IQR 12.5, 21; mean 16.8). Only 30% of pediatric hospitalists were full-time clinicians, whereas the rest had protected time for nonclinical duties. The average amount of protected time was 20% per full-time hospitalist.

Sustainability and Ideal FTE

Half of the division leaders reported that they or their hospitalists have concerns about the sustainability of the current workload. Programs perceived as sustainable required significantly fewer weekends per year (13 vs. 16, P < .02; Table 2) than those perceived as unsustainable. University-employed programs were more likely to be perceived as unsustainable (64% unsustainable vs. 32% unsustainable, P < .048), whereas programs with other employment models were more likely to be perceived as sustainable (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

This study updates what has been previously reported about the structure and characteristics of university-based pediatric hospitalist programs.3 It also deepens our understanding of a relatively new field and the evolution of clinical coverage models. This evolution has been impacted by decreased resident work hours, increased patient complexity and acuity,6 and a broadened focus on care coordination and communication,7 while attempting to build and sustain a high-quality workforce.

This study is the first to use an interview-based method to determine the current PHM workload and to focus exclusively on university-based programs. Compared with the study by Gosdin et al,3 our study, which utilized interviews instead of surveys, was able to clarify questions and obtain workload data with a common language of hours per year. This approach allowed interviewees to incorporate subtleties, such as clinical vs. total FTE, in their responses. Our study found a slightly narrower range of clinical hours per year and extended the understanding of nonclinical duties by finding that university-based hospitalists have an average of 20% protected time from clinical duties.

In this study, we also explored the perceived sustainability of current clinical models and the ideal clinical model in hours per year. Half of respondents felt their current model was unsustainable. This result suggested that the field must continue to mitigate attrition and burnout.

Interestingly, the total number of clinical hours did not significantly differ in programs perceived to be unsustainable. Instead, a higher number of weekends worked and university employment were associated with lack of sustainability. We hypothesize that weekends have a disproportionate impact on work-life balance as compared with total hours, and that employment by a university may be a proxy for the increased academic and teaching demands of hospitalists without protected time. Future studies may better elucidate these findings and inform programmatic efforts to address sustainability.

Given that PHM is a relatively young field, considering the evolution of our clinical work model within the context of pediatric emergency medicine (PEM), a field that faces similar challenges in overnight and weekend staffing requirements, may be helpful. Gorelick et al.8 reported that total clinical work hours in PEM (combined academic and nonacademic programs) has decreased from 35.3 hours per week in 1998 to 26.7 in 2013. Extrapolating these numbers to an annual position with 5 weeks PTO/CME, the average PEM attending physician works 1254 clinical hours. These numbers demonstrate a marked difference compared with the average 1800 clinical work hours for PHM found in our study.

Although total hours trend lower in PEM, the authors noted continued challenges in sustainability with an estimated half of all PEM respondents indicating a plan to reduce hours or leave the field in the next 5 years and endorsing symptoms of burnout.6 These findings from PEM may motivate PHM leaders to be more aggressive in adjusting work models toward sustainability in the future.

Our study has several limitations. We utilized a convenience sampling approach that requires the voluntary participation of division directors. Although we had robust interest from respondents representing all major geographic areas, the respondent pool might conceivably over-represent those most interested in understanding and/or changing PHM clinical models. Overall, our sample size was smaller than that achieved by a survey approach. Nevertheless, this limitation was offset by controlling respondent type and clarifying questions, thus improving the quality of our obtained data.

CONCLUSION

This interview-based study of PHM directors describes the current state of clinical work models for university-based hospitalists. University-based PHM programs have similar mean and median total clinical hours per year. However, these hours are higher than those considered ideal by PHM directors, and many are concerned about the sustainability of current work models. Notably, programs that are university-employed or have higher weekends worked per year are more likely to be perceived as unsustainable. Future studies should explore differences between programs with sustainable work models and those with high levels of attrition and burnout.

Disclosures

The authors have no other conflicts to report.

Funding

A grant from the American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Hospital Medicine funded this study through the Subcommittee on Division and Program Leaders.