User login

Should You Report a Substance-Abusing Colleague to the State Licensing Board?

PRO

Hospitalists’ moral obligation is to protect the patient

In this era of historic budget deficits, wars, and political strife surrounding healthcare reform, one might ask if we can afford to spend valuable time and energy on the issue of reporting physicians who abuse substances.

At first glance, I certainly had skepticism about the subject, but then I dug deeper. To my surprise (and likely yours), studies indicate that physicians develop substance-abuse problems as often or more than the general population does.1 Recent reports detail horrific patient outcomes at the hands of health providers whose actions are compromised by drug use. With data showing the prevalence of substance abuse among physicians hovering around 10% to 12%, we must accept the reality that hospitalists are not exempt.2,3,4,5

As medical doctors, our promise to our patients is to provide care in an ethical manner. Even if we try to live in denial, most of us would agree that with great blessing (or power) comes great responsibility. So when the question of reporting a fellow hospitalist who is abusing substances was asked, my response was unequivocally yes.

In my opinion, this discussion can be limited to two overarching principles: First, we are compelled to put our patients first. As hospitalists, we are blessed to be caring for some of the most frail and vulnerable in our society. Fortunately, an overwhelming number of us do so with pride, skill, and integrity.

The task of providing high-quality care to an empowered patient population is difficult enough with us being physically, emotionally, and mentally exhausted. But to add substance abuse to this is just a complete and utter violation of our patients’ trust. We must agree that putting our patients’ well-being beyond reproach requires us to report any colleague who is compromised.

Second, delayed help for a colleague in trouble with substance-abuse issues could be fatal—and for more than just that single colleague. At some point, we are compelled to do more than just raise an eyebrow and shake our head. Usually at the time of discovery, months if not years of substance abuse already have gone by undetected. Deferring to the next person is just not an option. There is too much at stake. It is our moral duty to help our colleagues who are unable to realize the danger they are posing to themselves, the team, and, most importantly, the patients.

Certainly, physicians do not need another lecture about the perils of substance abuse. Whether discussing prescription drugs, alcohol, marijuana, cocaine, or the like, we all have witnessed the devastating effects of abuse. The fact is, any substance that alters our ability to perform our trusted duty must be avoided.

Colleagues, the algorithm is simple: Be vigilant, observe, confirm, and report. It is our moral and ethical imperative.

Dr. Pyke is chief medical officer of Medicus Consulting, LLC.

CON

Responsible, helpful action doesn’t always mean official involvement

Recognizing impairment in our colleagues is both difficult and ethically challenging. Despite national trends, medicine remains a largely self-regulated profession, and we have an ethical obligation to report impaired, incompetent, or unethical colleagues. Rarely are the indications for reporting or identifying a colleague clear.

As trained clinicians, we know the signs of substance abuse:6

- Frequent tardiness and absences;

- Unexplained disappearances during working hours;

- Inappropriate behavior;

- Affective lability or irritability;

- Interpersonal conflict;

- Avoidance of peers or supervisors;

- Keeping odd hours;

- Disorganized and forgetful;

- Incomplete charts and work performance;

- Heavy drinking at social functions;

- Unexplained changes in weight or energy level;

- Diminished personal hygiene;

- Slurred or rapid speech;

- Frequently dilated pupils or red, watery eyes and a runny nose;

- Defensiveness, anxiety, apathy, and manipulative behaviors; and

- Withdrawal from long-standing relationships.

Yet when it is a colleague, we are often in denial about their substance abuse. Certainly, simple seasonal allergies and allergy medications can cause a number of the above symptoms. We also are aware of and fear the potential impact of licensing board notification on a physician’s career. In fact, in a national survey of physicians, 45% of respondents who had encountered impaired or incompetent physicians had not reported them, even though 96% of those surveyed agreed that physicians should report impaired or incompetent colleagues.7

Similar to reporting child or elder abuse, you don’t want to be wrong.

At the same time, impaired physicians are disruptive. They negatively impact the lives of their patients, colleagues, and hospital staff.

It is possible to do both the responsible thing and not go directly to the licensing board. You are not responsible for diagnosing your colleagues, but rather recognizing possible impairment.

Check out the Federation of State Physician Health Programs’ website (www.fsphp.org) to identify a local physician health program. Call them and place a report of concern identifying your impaired colleague. While it’s possibly new to you, they have years of experience working with this situation. Trust these organizations, many of which are independent from licensing, to intervene responsibly and confidentially. They can evaluate your colleague and provide a treatment plan and monitoring, as needed. Their approach is rehabilitative rather than punitive, and they resist reporting to the medical board unless the physician-patient is noncompliant.

Physicians have better outcomes than the general population, with reported abstinence rates of 70% to 90% for those who complete treatment.8,9 Between 75% and 85% of physicians who complete rehabilitation and comply with close monitoring and follow-up care are able to return to work.9,10

There is hope for your impaired colleague. Contact your local physician health program.

Dr. Guerrasio is a hospitalist and director of resident and medical student remediation at the University of Colorado Denver.

References

- Hughes PH, Brandenburg N, Baldwin DC Jr., et al. Prevalence of substance use among US physicians. JAMA. 1992;267:2333-2339.

- Gold KB, Teitelbaum SA. Physicians impaired by substance abuse disorders. The Journal of Global Drug Policy and Practice website. Available at: http://www.globaldrugpolicy.org/2/2/3.php. Accessed June 27, 2011.

- Wolfgang AP. Substance abuse potential and job stress: a study of pharmacists, physicians, and nurses. J Pharm Mark Manage. 1989;3(4):97-110.

- Cicala RS. Substance abuse among physicians: What you need to know. Hosp Phys. 2003:39-46.

- Berge KH, Seppala MD, Schipper AM. Chemical dependency and the physician. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84(7):625-631.

- Bright RP, Krahn L. Impaired physicians: How to recognize, when to report, and where to refer. Curr Psy. 2010;9(6):11-20.

- Campbell EG, Regan S, Gruen RL, et al. Professionalism in medicine: results of a national survey of physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:795-802.

- Femino J, Nirenberg TD. Treatment outcome studies on physician impairment: a review of the literature. R I Med. 1994;77:345-350.

- Alpern F, Correnti CE, Dolan TE, Llufrio MC, Sill A. A survey of recovering Maryland physicians. Md Med J. 1992;41:301-303.

- Gallegos KV, Lubin BH, Bowers C, Blevins JW, Talbott GD, Wilson PO. Relapse and recovery: five to ten year follow-up study of chemically dependent physicians—the Georgia experience. Md Med J. 1992;41:315-319.

PRO

Hospitalists’ moral obligation is to protect the patient

In this era of historic budget deficits, wars, and political strife surrounding healthcare reform, one might ask if we can afford to spend valuable time and energy on the issue of reporting physicians who abuse substances.

At first glance, I certainly had skepticism about the subject, but then I dug deeper. To my surprise (and likely yours), studies indicate that physicians develop substance-abuse problems as often or more than the general population does.1 Recent reports detail horrific patient outcomes at the hands of health providers whose actions are compromised by drug use. With data showing the prevalence of substance abuse among physicians hovering around 10% to 12%, we must accept the reality that hospitalists are not exempt.2,3,4,5

As medical doctors, our promise to our patients is to provide care in an ethical manner. Even if we try to live in denial, most of us would agree that with great blessing (or power) comes great responsibility. So when the question of reporting a fellow hospitalist who is abusing substances was asked, my response was unequivocally yes.

In my opinion, this discussion can be limited to two overarching principles: First, we are compelled to put our patients first. As hospitalists, we are blessed to be caring for some of the most frail and vulnerable in our society. Fortunately, an overwhelming number of us do so with pride, skill, and integrity.

The task of providing high-quality care to an empowered patient population is difficult enough with us being physically, emotionally, and mentally exhausted. But to add substance abuse to this is just a complete and utter violation of our patients’ trust. We must agree that putting our patients’ well-being beyond reproach requires us to report any colleague who is compromised.

Second, delayed help for a colleague in trouble with substance-abuse issues could be fatal—and for more than just that single colleague. At some point, we are compelled to do more than just raise an eyebrow and shake our head. Usually at the time of discovery, months if not years of substance abuse already have gone by undetected. Deferring to the next person is just not an option. There is too much at stake. It is our moral duty to help our colleagues who are unable to realize the danger they are posing to themselves, the team, and, most importantly, the patients.

Certainly, physicians do not need another lecture about the perils of substance abuse. Whether discussing prescription drugs, alcohol, marijuana, cocaine, or the like, we all have witnessed the devastating effects of abuse. The fact is, any substance that alters our ability to perform our trusted duty must be avoided.

Colleagues, the algorithm is simple: Be vigilant, observe, confirm, and report. It is our moral and ethical imperative.

Dr. Pyke is chief medical officer of Medicus Consulting, LLC.

CON

Responsible, helpful action doesn’t always mean official involvement

Recognizing impairment in our colleagues is both difficult and ethically challenging. Despite national trends, medicine remains a largely self-regulated profession, and we have an ethical obligation to report impaired, incompetent, or unethical colleagues. Rarely are the indications for reporting or identifying a colleague clear.

As trained clinicians, we know the signs of substance abuse:6

- Frequent tardiness and absences;

- Unexplained disappearances during working hours;

- Inappropriate behavior;

- Affective lability or irritability;

- Interpersonal conflict;

- Avoidance of peers or supervisors;

- Keeping odd hours;

- Disorganized and forgetful;

- Incomplete charts and work performance;

- Heavy drinking at social functions;

- Unexplained changes in weight or energy level;

- Diminished personal hygiene;

- Slurred or rapid speech;

- Frequently dilated pupils or red, watery eyes and a runny nose;

- Defensiveness, anxiety, apathy, and manipulative behaviors; and

- Withdrawal from long-standing relationships.

Yet when it is a colleague, we are often in denial about their substance abuse. Certainly, simple seasonal allergies and allergy medications can cause a number of the above symptoms. We also are aware of and fear the potential impact of licensing board notification on a physician’s career. In fact, in a national survey of physicians, 45% of respondents who had encountered impaired or incompetent physicians had not reported them, even though 96% of those surveyed agreed that physicians should report impaired or incompetent colleagues.7

Similar to reporting child or elder abuse, you don’t want to be wrong.

At the same time, impaired physicians are disruptive. They negatively impact the lives of their patients, colleagues, and hospital staff.

It is possible to do both the responsible thing and not go directly to the licensing board. You are not responsible for diagnosing your colleagues, but rather recognizing possible impairment.

Check out the Federation of State Physician Health Programs’ website (www.fsphp.org) to identify a local physician health program. Call them and place a report of concern identifying your impaired colleague. While it’s possibly new to you, they have years of experience working with this situation. Trust these organizations, many of which are independent from licensing, to intervene responsibly and confidentially. They can evaluate your colleague and provide a treatment plan and monitoring, as needed. Their approach is rehabilitative rather than punitive, and they resist reporting to the medical board unless the physician-patient is noncompliant.

Physicians have better outcomes than the general population, with reported abstinence rates of 70% to 90% for those who complete treatment.8,9 Between 75% and 85% of physicians who complete rehabilitation and comply with close monitoring and follow-up care are able to return to work.9,10

There is hope for your impaired colleague. Contact your local physician health program.

Dr. Guerrasio is a hospitalist and director of resident and medical student remediation at the University of Colorado Denver.

References

- Hughes PH, Brandenburg N, Baldwin DC Jr., et al. Prevalence of substance use among US physicians. JAMA. 1992;267:2333-2339.

- Gold KB, Teitelbaum SA. Physicians impaired by substance abuse disorders. The Journal of Global Drug Policy and Practice website. Available at: http://www.globaldrugpolicy.org/2/2/3.php. Accessed June 27, 2011.

- Wolfgang AP. Substance abuse potential and job stress: a study of pharmacists, physicians, and nurses. J Pharm Mark Manage. 1989;3(4):97-110.

- Cicala RS. Substance abuse among physicians: What you need to know. Hosp Phys. 2003:39-46.

- Berge KH, Seppala MD, Schipper AM. Chemical dependency and the physician. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84(7):625-631.

- Bright RP, Krahn L. Impaired physicians: How to recognize, when to report, and where to refer. Curr Psy. 2010;9(6):11-20.

- Campbell EG, Regan S, Gruen RL, et al. Professionalism in medicine: results of a national survey of physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:795-802.

- Femino J, Nirenberg TD. Treatment outcome studies on physician impairment: a review of the literature. R I Med. 1994;77:345-350.

- Alpern F, Correnti CE, Dolan TE, Llufrio MC, Sill A. A survey of recovering Maryland physicians. Md Med J. 1992;41:301-303.

- Gallegos KV, Lubin BH, Bowers C, Blevins JW, Talbott GD, Wilson PO. Relapse and recovery: five to ten year follow-up study of chemically dependent physicians—the Georgia experience. Md Med J. 1992;41:315-319.

PRO

Hospitalists’ moral obligation is to protect the patient

In this era of historic budget deficits, wars, and political strife surrounding healthcare reform, one might ask if we can afford to spend valuable time and energy on the issue of reporting physicians who abuse substances.

At first glance, I certainly had skepticism about the subject, but then I dug deeper. To my surprise (and likely yours), studies indicate that physicians develop substance-abuse problems as often or more than the general population does.1 Recent reports detail horrific patient outcomes at the hands of health providers whose actions are compromised by drug use. With data showing the prevalence of substance abuse among physicians hovering around 10% to 12%, we must accept the reality that hospitalists are not exempt.2,3,4,5

As medical doctors, our promise to our patients is to provide care in an ethical manner. Even if we try to live in denial, most of us would agree that with great blessing (or power) comes great responsibility. So when the question of reporting a fellow hospitalist who is abusing substances was asked, my response was unequivocally yes.

In my opinion, this discussion can be limited to two overarching principles: First, we are compelled to put our patients first. As hospitalists, we are blessed to be caring for some of the most frail and vulnerable in our society. Fortunately, an overwhelming number of us do so with pride, skill, and integrity.

The task of providing high-quality care to an empowered patient population is difficult enough with us being physically, emotionally, and mentally exhausted. But to add substance abuse to this is just a complete and utter violation of our patients’ trust. We must agree that putting our patients’ well-being beyond reproach requires us to report any colleague who is compromised.

Second, delayed help for a colleague in trouble with substance-abuse issues could be fatal—and for more than just that single colleague. At some point, we are compelled to do more than just raise an eyebrow and shake our head. Usually at the time of discovery, months if not years of substance abuse already have gone by undetected. Deferring to the next person is just not an option. There is too much at stake. It is our moral duty to help our colleagues who are unable to realize the danger they are posing to themselves, the team, and, most importantly, the patients.

Certainly, physicians do not need another lecture about the perils of substance abuse. Whether discussing prescription drugs, alcohol, marijuana, cocaine, or the like, we all have witnessed the devastating effects of abuse. The fact is, any substance that alters our ability to perform our trusted duty must be avoided.

Colleagues, the algorithm is simple: Be vigilant, observe, confirm, and report. It is our moral and ethical imperative.

Dr. Pyke is chief medical officer of Medicus Consulting, LLC.

CON

Responsible, helpful action doesn’t always mean official involvement

Recognizing impairment in our colleagues is both difficult and ethically challenging. Despite national trends, medicine remains a largely self-regulated profession, and we have an ethical obligation to report impaired, incompetent, or unethical colleagues. Rarely are the indications for reporting or identifying a colleague clear.

As trained clinicians, we know the signs of substance abuse:6

- Frequent tardiness and absences;

- Unexplained disappearances during working hours;

- Inappropriate behavior;

- Affective lability or irritability;

- Interpersonal conflict;

- Avoidance of peers or supervisors;

- Keeping odd hours;

- Disorganized and forgetful;

- Incomplete charts and work performance;

- Heavy drinking at social functions;

- Unexplained changes in weight or energy level;

- Diminished personal hygiene;

- Slurred or rapid speech;

- Frequently dilated pupils or red, watery eyes and a runny nose;

- Defensiveness, anxiety, apathy, and manipulative behaviors; and

- Withdrawal from long-standing relationships.

Yet when it is a colleague, we are often in denial about their substance abuse. Certainly, simple seasonal allergies and allergy medications can cause a number of the above symptoms. We also are aware of and fear the potential impact of licensing board notification on a physician’s career. In fact, in a national survey of physicians, 45% of respondents who had encountered impaired or incompetent physicians had not reported them, even though 96% of those surveyed agreed that physicians should report impaired or incompetent colleagues.7

Similar to reporting child or elder abuse, you don’t want to be wrong.

At the same time, impaired physicians are disruptive. They negatively impact the lives of their patients, colleagues, and hospital staff.

It is possible to do both the responsible thing and not go directly to the licensing board. You are not responsible for diagnosing your colleagues, but rather recognizing possible impairment.

Check out the Federation of State Physician Health Programs’ website (www.fsphp.org) to identify a local physician health program. Call them and place a report of concern identifying your impaired colleague. While it’s possibly new to you, they have years of experience working with this situation. Trust these organizations, many of which are independent from licensing, to intervene responsibly and confidentially. They can evaluate your colleague and provide a treatment plan and monitoring, as needed. Their approach is rehabilitative rather than punitive, and they resist reporting to the medical board unless the physician-patient is noncompliant.

Physicians have better outcomes than the general population, with reported abstinence rates of 70% to 90% for those who complete treatment.8,9 Between 75% and 85% of physicians who complete rehabilitation and comply with close monitoring and follow-up care are able to return to work.9,10

There is hope for your impaired colleague. Contact your local physician health program.

Dr. Guerrasio is a hospitalist and director of resident and medical student remediation at the University of Colorado Denver.

References

- Hughes PH, Brandenburg N, Baldwin DC Jr., et al. Prevalence of substance use among US physicians. JAMA. 1992;267:2333-2339.

- Gold KB, Teitelbaum SA. Physicians impaired by substance abuse disorders. The Journal of Global Drug Policy and Practice website. Available at: http://www.globaldrugpolicy.org/2/2/3.php. Accessed June 27, 2011.

- Wolfgang AP. Substance abuse potential and job stress: a study of pharmacists, physicians, and nurses. J Pharm Mark Manage. 1989;3(4):97-110.

- Cicala RS. Substance abuse among physicians: What you need to know. Hosp Phys. 2003:39-46.

- Berge KH, Seppala MD, Schipper AM. Chemical dependency and the physician. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84(7):625-631.

- Bright RP, Krahn L. Impaired physicians: How to recognize, when to report, and where to refer. Curr Psy. 2010;9(6):11-20.

- Campbell EG, Regan S, Gruen RL, et al. Professionalism in medicine: results of a national survey of physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:795-802.

- Femino J, Nirenberg TD. Treatment outcome studies on physician impairment: a review of the literature. R I Med. 1994;77:345-350.

- Alpern F, Correnti CE, Dolan TE, Llufrio MC, Sill A. A survey of recovering Maryland physicians. Md Med J. 1992;41:301-303.

- Gallegos KV, Lubin BH, Bowers C, Blevins JW, Talbott GD, Wilson PO. Relapse and recovery: five to ten year follow-up study of chemically dependent physicians—the Georgia experience. Md Med J. 1992;41:315-319.

Hospitalist‐Run Acute Care for Elderly

For the frail older patient, hospitalization marks a period of high risk of poor outcomes and adverse events including functional decline, delirium, pressure ulcers, adverse drug events, nosocomial infections, and falls.1, 2 Physician recognition of elderly patients at risk for adverse outcomes is poor, making it difficult to intervene to prevent them.3, 4 Among frail, elderly inpatients at an urban academic medical center, doctors documented cognitive assessments in only 5% of patients. Functional assessments are appropriately documented in 40%80% of inpatients.3, 5

The Acute Care for Elders (ACE) unit is one of several models of comprehensive inpatient geriatric care that have been developed by geriatrician researchers to address the adverse events and functional decline that often accompany hospitalization.6 The ACE unit model generally incorporates: 1) a modified hospital environment, 2) early assessment and intensive management to minimize the adverse effects of hospital care, 3) early discharge planning, 4) patient centered care protocols, and 5) a consistent nursing staff.7 Two randomized, controlled trials have shown the ACE unit model to be successful in reducing functional decline among frail older inpatients during and after hospitalization.7, 8 While meta‐analyses data also suggests the ACE unit model reduces functional decline and future institutionalization, significant impact on other outcomes is not proven.9, 10

Several barriers have prevented the successful dissemination of the ACE unit model. The chief limitations are the upfront resources required to create and maintain a modified, dedicated unit, as well as the lack of a geriatrics trained workforce.7, 1113 The rapid growth of hospital medicine presents opportunities for innovation in the care of older patients. Still, a 2006 census demonstrated that few hospitalist groups had identified geriatric care as a priority.14

In response to these challenges, the University of Colorado Hospital Medicine Group created a hospitalist‐run inpatient medical service designed for the care of the frail older patient. This Hospitalist‐Acute Care for the Elderly (Hospitalist‐ACE) unit is a hybrid of a general medical service and an inpatient geriatrics unit.7 The goals of the Hospitalist‐ACE service are to provide high quality care tailored to older inpatients, thus minimizing the risks of functional decline and adverse events associate with hospitalization, and to provide a clinical geriatrics teaching experience for Hospitalist Training Track Residents within the Internal Medicine Residency Training Program and medical students at the University of Colorado Denver School of Medicine. The Hospitalist‐ACE unit is staffed with a core group of hospitalist attendings who have, at a minimum, attended an intensive mini‐course in inpatient geriatrics. The service employs interdisciplinary rounds; a brief, standardized geriatric assessment including screens of function, cognition, and mood; a clinical focus on mitigating the hazards of hospitalization, early discharge planning; and a novel geriatric educational curriculum for medicine residents and medical students.

This article will: 1) describe the creation of the Hospitalist‐ACE service at the University of Colorado Hospital; and 2) summarize the evaluation of the Hospitalist‐ACE service in a quasi‐randomized, controlled manner during its first year. We hypothesized that, when compared to patients receiving usual care, patients cared for on the Hospitalist‐ACE service would have increased recognition of abnormal functional status; recognition of abnormal cognitive status and delirium; equivalent lengths of stay and hospital charges; and decreased falls, 30‐day readmissions, and restraint use.

METHODS

Design

We performed a quasi‐randomized, controlled study of the Hospitalist‐ACE service.

Setting

The study setting was the inpatient general medical services of the Anschutz Inpatient Pavilion (AIP) of the University of Colorado Hospital (UCH). The AIP is a 425‐bed tertiary care hospital that is the major teaching affiliate of the University of Colorado School of Medicine and a regional referral center. The control services, hereafter referred to as usual care, were comprised of the four inpatient general medicine teaching services that take admissions on a four‐day rotation (in general, two were staffed by outpatient general internists and medical subspecialists, and two were staffed by academic hospitalists). The Hospitalist‐ACE service was a novel hospitalist teaching service that began in July 2007. Hospitalist‐ACE patients were admitted to a single 12‐bed medical unit (12 West) when beds were available; 12 West is similar to the other medical/surgical units at UCH and did not have any modifications to the rooms, equipment, or common areas for the intervention. The nursing staff on this unit had no formal geriatric nursing training. The Hospitalist‐ACE team admitted patients daily (between 7 AM and 3 PM MondayFriday; between 7 AM and 12 noon Saturday and Sunday). Patients assigned to the Hospitalist‐ACE service after hours were admitted by the internal medicine resident on call for the usual care services and handed off to the Hospitalist‐ACE team at 7 AM the next morning.

Study Subjects

Eligible subjects were inpatients age 70 years admitted to the usual care or Hospitalist‐ACE services at the AIP from November 2, 2007 to April 15, 2008. All patients age 70 years were randomized to the Hospitalist‐ACE service or usual care on a general internal medicine service by the last digit of the medical record number (odd numbers admitted to the Hospitalist‐ACE service and even numbers admitted to usual care). Patients followed by the Hospitalist‐ACE service but not admitted to 12 West were included in the study. To isolate the impact of the intervention, patients admitted to a medicine subspecialty service (such as cardiology, pulmonary, or oncology), or transferred to or from the Hospitalist‐ACE or control services to another service (eg, intensive care unit [ICU] or orthopedic surgery service) were excluded from the study.

Intervention

The Hospitalist‐ACE unit implemented an interdisciplinary team approach to identify and address geriatric syndromes in patients aged 70 and over. The Hospitalist‐ACE model of care consisted of clinical care provided by a hospitalist attending with additional training in geriatric medicine, administration of standardized geriatric screens assessing function, cognition, and mood, 15 minute daily (MondayFriday) interdisciplinary rounds focusing on recognition and management of geriatric syndromes and early discharge planning, and a standardized educational curriculum for medical residents and medical students addressing hazards of hospitalization.

The Hospitalist‐ACE service was a unique rotation within the Hospitalist Training Track of the Internal Medicine Residency that was developed with the support of the University of Colorado Hospital and the Internal Medicine Residency Training Program, and input from the Geriatrics Division at the University of Colorado Denver. The director received additional training from the Donald W. Reynolds FoundationUCLA Faculty Development to Advance Geriatric Education Mini‐Fellowship for hospitalist faculty. The mission of the service was to excel at educating the next generation of hospitalists while providing a model for excellence of care for hospitalized elderly patients. Important stakeholders were identified, and a leadership teamincluding representatives from nursing, physical and occupational therapy, pharmacy, social work, case management, and later, volunteer servicescreated the model daily interdisciplinary rounds. As geographic concentration was essential for the viability of interdisciplinary rounds, one unit (12 West) within the hospital was designated as the preferred location for patients admitted to the Hospitalist‐ACE service.

The Hospitalist‐ACE unit team consisted of one attending hospitalist, one resident, one intern, and medical students. The attending was one of five hospitalists, with additional training in geriatric medicine, who rotated attending responsibilities on the service. One of the hospitalists was board certified in geriatric medicine. Each of the other four hospitalists attended the Reynolds FoundationUCLA mini‐fellowship in geriatric medicine. Hospitalist‐ACE attendings rotated on a variety of other hospitalist services throughout the academic year, including the usual care services.

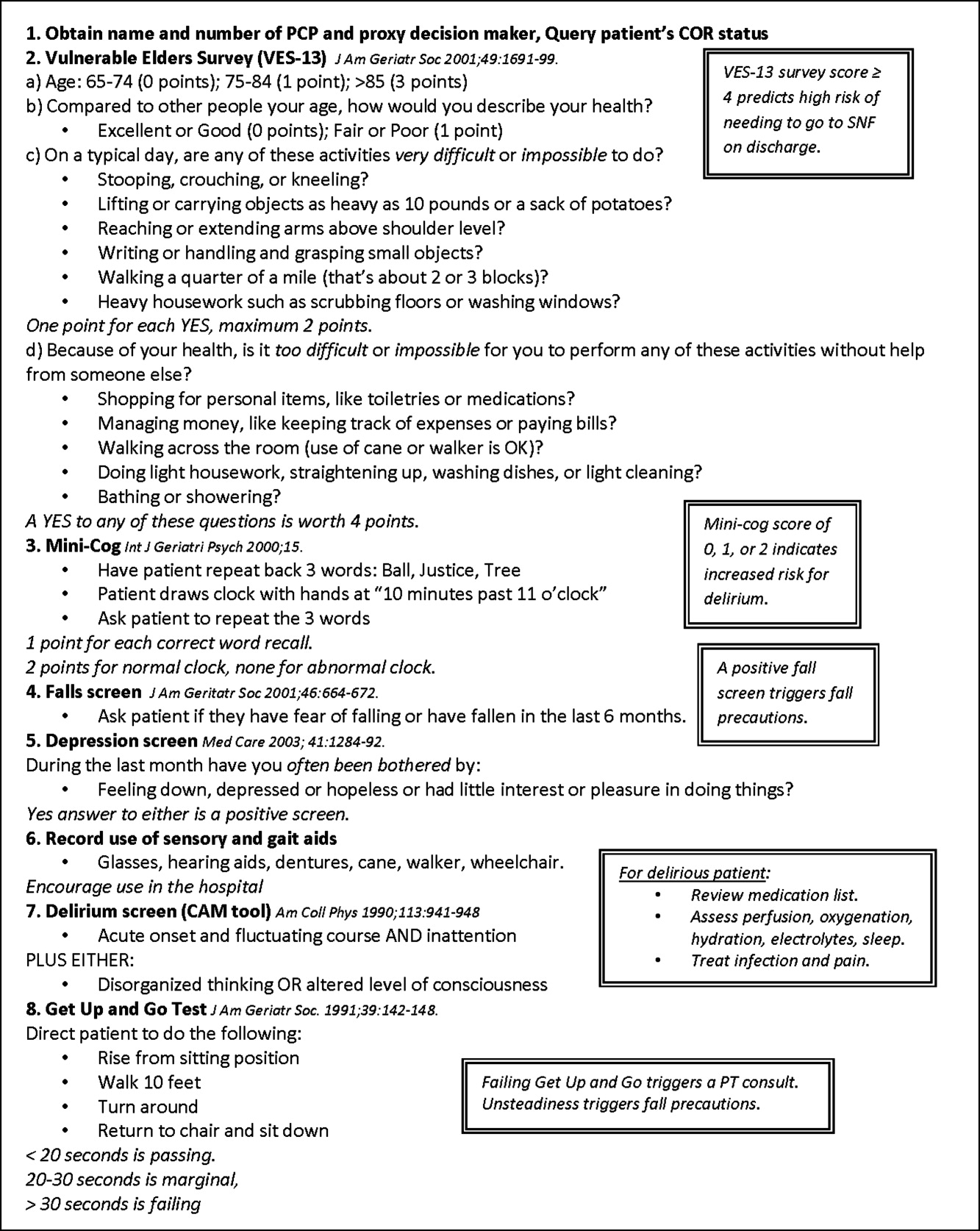

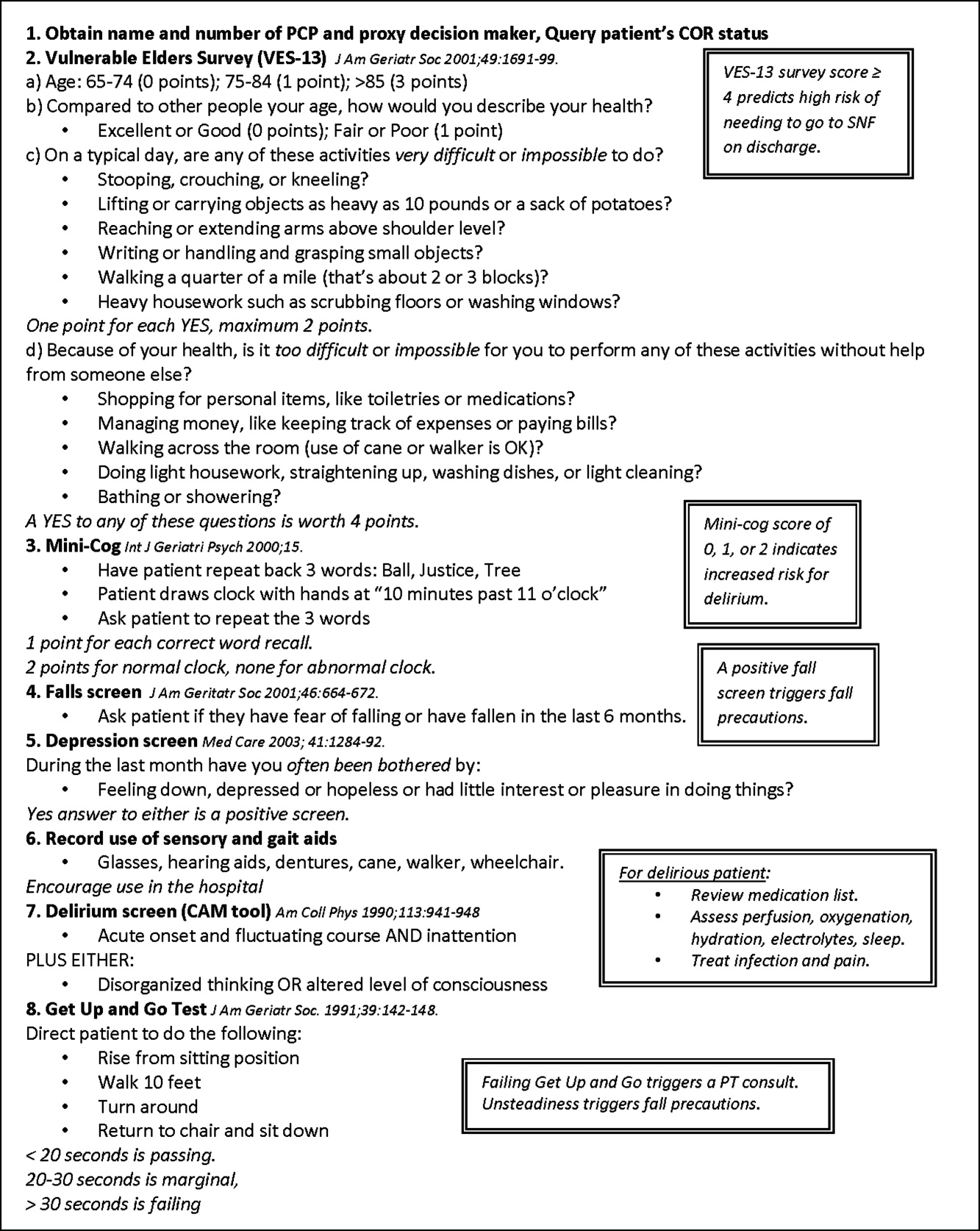

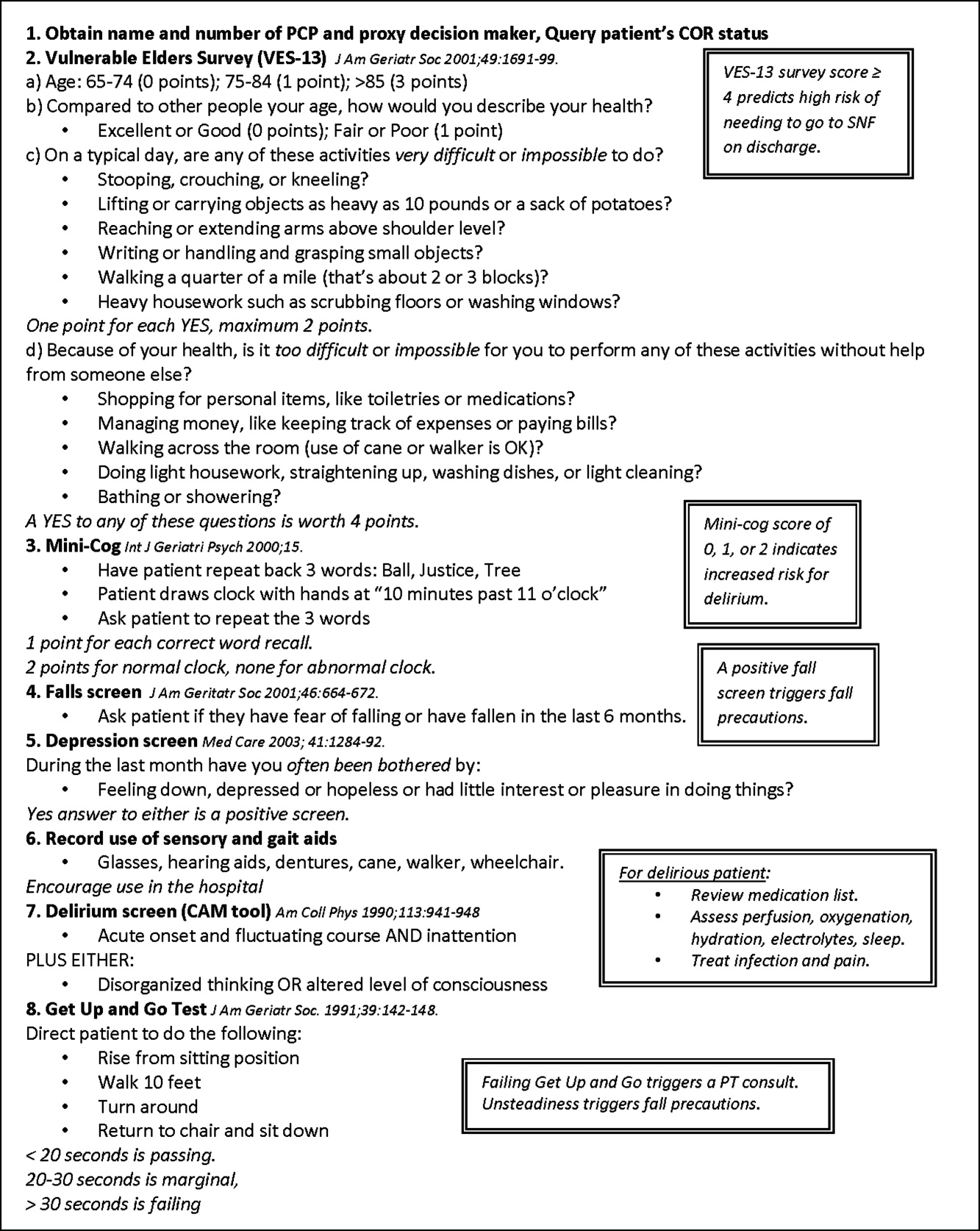

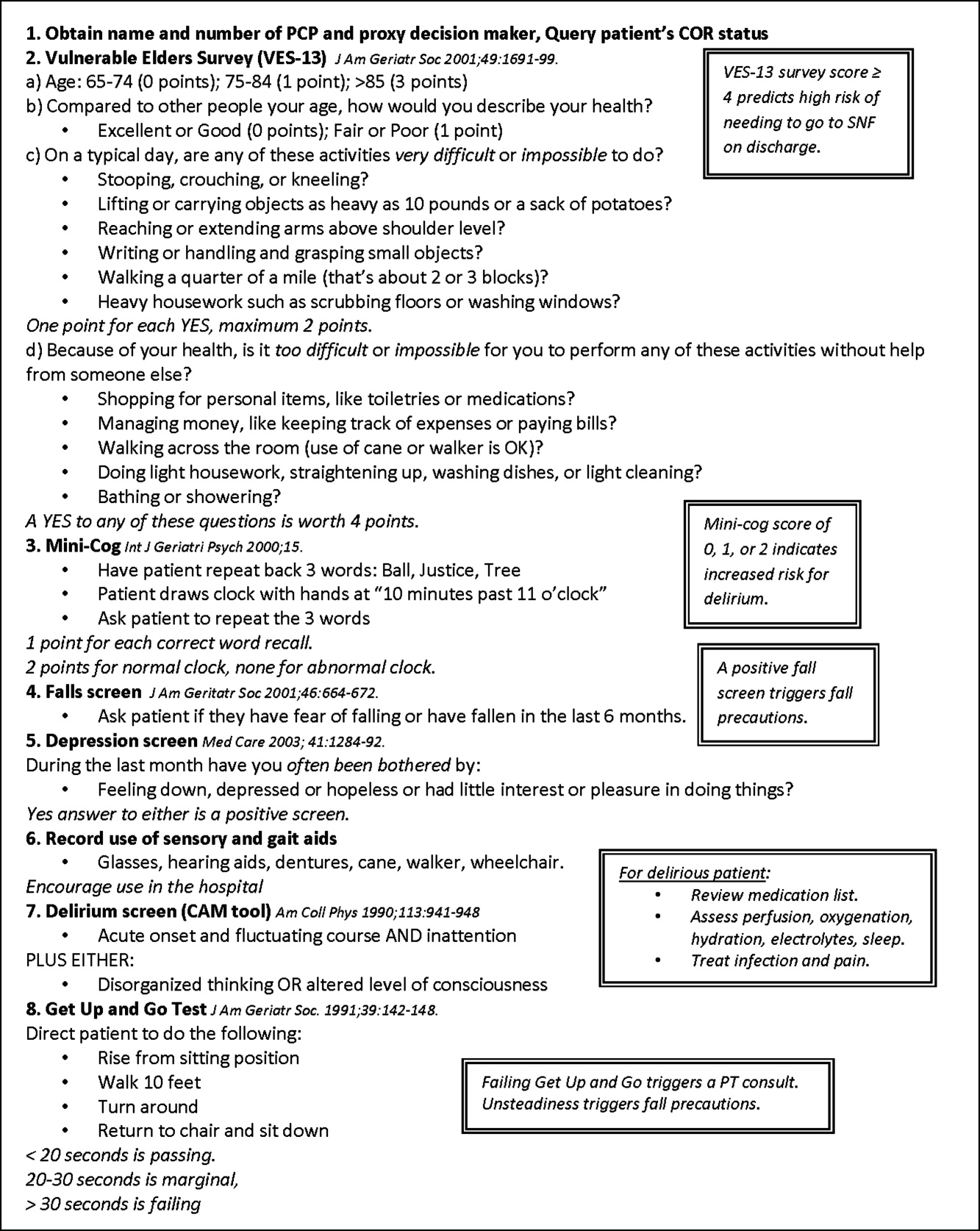

The brief standardized geriatric assessment consisted of six validated instruments, and was completed by house staff or medical students on admission, following instruction by the attending physician. The complete assessment tool is shown in Figure 1. The cognitive items included the Mini‐Cog,15 a two‐item depression screen,16 and the Confusion Assessment Method.17 The functional items included the Vulnerable Elders Survey (VES‐13),18 the Timed Get Up and Go test,19 and a two‐question falls screen.20 The elements of the assessment tool were selected by the Hospitalist‐ACE attendings for brevity and the potential to inform clinical management. To standardize the clinical and educational approach, the Hospitalist‐ACE attendings regularly discussed appropriate orders recommended in response to each positive screen, but no templated order sets were used during the study period.

Interdisciplinary rounds were attended by Hospitalist‐ACE physicians, nurses, case managers, social workers, physical or occupational therapists, pharmacists, and volunteers. Rounds were led by the attending or medical resident.

The educational curriculum encompassed 13 modules created by the attending faculty that cover delirium, falls, dementia, pressure ulcers, physiology of aging, movement disorders, medication safety, end of life care, advance directives, care transitions, financing of health care for the elderly, and ethical conundrums in the care of the elderly. A full table of contents appears in online Appendix 1. Additionally, portions of the curriculum have been published online.21, 22 Topic selection was guided by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) core geriatrics topics determined most relevant for the inpatient setting. Formal instruction of 3045 minutes duration occurred three to four days a week and was presented in addition to routine internal medicine educational conferences. Attendings coordinated teaching to ensure that each trainee was exposed to all of the content during the course of their four‐week rotation.

In contrast to the Hospitalist‐ACE service, usual care on the control general medical services consisted of either a hospitalist, a general internist, or an internal medicine subspecialist attending physician, with one medical resident, one intern, and medical students admitting every fourth day. The general medical teams attended daily discharge planning rounds with a discharge planner and social worker focused exclusively on discharge planning. The content of teaching rounds on the general medical services was largely left to the discretion of the attending physician.

This program evaluation of the Hospitalist‐ACE service was granted a waiver of consent and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Primary Outcome

The primary outcome for the study was the recognition of abnormal functional status by the primary team. Recognition of abnormal functional status was determined from chart review and consisted of both the physician's detection of abnormal functional status and evidence of a corresponding treatment plan identified in the notes or orders of a physician member of the primary team (Table 1).

| Measure | Criterion | Source | Content Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Recognition of abnormal functional status* | 1) Detection | MD's documentation of history | Presentation with change in function (new gait instability); use of gait aides (wheelchair) |

| OR | |||

| MD's documentation of physical exam | Observation of abnormal gait (eg, unsteady, wide‐based, shuffling) and/or balance Abnormal Get Up and Go test | ||

| AND | |||

| 2) Treatment | MD's order | PT/OT consult; home safety evaluation | |

| OR | |||

| MD's documentation assessment/plan | Inclusion of functional status (rehabilitation, PT/OT needs) on the MD's problem list | ||

| Recognition of abnormal cognitive status | Any of the following: | ||

| Delirium | 1) Detection | MD's history | Presentation of confusion or altered mental status |

| OR | |||

| MD's physical exam | Abnormal confusion assessment method | ||

| AND | |||

| 2) Treatment | MD's order | Sitter, reorienting communication, new halperidol order | |

| OR | |||

| MD's documentation of assessment/plan | Inclusion of delirium on the problem list | ||

| OR | |||

| Dementia | 1) Detection | MD's history | Dementia in medical history |

| OR | OR | ||

| MD's physical exam | Abnormal Folstein Mini‐Mental Status Exam or Mini‐Cog | ||

| AND | |||

| 2) Treatment | MD's order | Cholinesterase inhibitor ordered | |

| OR | OR | ||

| MD's documentation of assessment/plan | Inclusion of dementia on the problem list | ||

| OR | |||

| Depression | 1) Detection | MD's history | Depression in medical history |

| OR | OR | ||

| MD's physical exam | Positive depression screen | ||

| AND | |||

| 2) Treatment | MD's order | New antidepressant order | |

| OR | |||

| MD's documentation of assessment/plan | Inclusion of depression on the problem list | ||

Secondary Outcomes

Recognition of abnormal cognitive status was determined from chart review and consisted of both the physician's detection of dementia, depression, or delirium, and evidence of a corresponding treatment plan for any of the documented conditions identified in the notes or orders of a physician member of the primary team (Table 1). Additionally, we measured recognition and treatment of delirium alone.

Falls were determined from mandatory event reporting collected by the hospital on the University Hospitals Consortium Patient Safety Net web‐based reporting system and based on clinical assessment as reported by the nursing staff. The reports are validated by the appropriate clinical managers within 45 days of the event according to standard procedure.

Physical restraint use (type of restraint and duration) was determined from query of mandatory clinical documentation in the electronic medical record. Use of sleep aids was determined from review of the physician's order sheets in the medical record. The chart review captured any of 39 commonly prescribed hypnotic medications ordered at hour of sleep or for insomnia. The sleep medication list was compiled with the assistance of a pharmacist for an earlier chart review and included non‐benzodiazepine hypnotics, benzodiazepines, antidepressants, antihistamines, and antipsychotics.23

Length of stay, hospital charges, 30‐day readmissions to UCH (calculated from date of discharge), and discharge location were determined from administrative data.

Additional Descriptive Variables

Name, medical record number, gender, date of birth, date of admission and discharge, and primary diagnosis were obtained from the medical record. The Case Mix Index for each group of patients was determined from the average Medicare Severity‐adjusted Diagnosis Related Group (MS‐DRG) weight obtained from administrative data.

Data Collection

A two‐step, retrospective chart abstraction was employed. A professional research assistant (P.R.A.) hand‐abstracted process measures from the paper medical chart onto a data collection form designed for this study. A physician investigator performed a secondary review (H.L.W.). Discrepancies were resolved by the physician reviewer.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were performed on intervention and control subjects. Means and standard deviations (age) or frequencies (gender, primary diagnoses) were calculated as appropriate. T tests were used for continuous variables, chi‐square tests for gender, and the Wilcoxon rank sum test for categorical variables.

Outcomes were reported as means and standard deviations for continuous variables (length of stay and charges) and frequencies for categorical variables (all other outcomes). T tests were used for continuous variables, Fisher's exact test for restraint use, and chi‐square tests were used for categorical variable to compare the impact of the intervention between intervention and control patients. For falls, confidence intervals were calculated for the incidence rate differences based on Poisson approximations.

Sample Size Considerations

An a priori sample size calculation was performed. A 2001 study showed that functional status is poorly documented in at least 60% of hospital charts of elderly patients.5 Given an estimated sample size of 120 per group and a power of 80%, this study was powered to be able to detect an absolute difference in the documentation of functional status of as little as 18%.

RESULTS

Two hundred seventeen patients met the study entry criteria (Table 2): 122 were admitted to the Hospitalist‐ACE service, and 95 were admitted to usual care on the general medical services. The average age of the study patients was 80.5 years, 55.3% were female. Twenty‐eight percent of subjects were admitted for pulmonary diagnoses. The two groups of patients were similar with respect to age, gender, and distribution of primary diagnoses. The Hospitalist‐ACE patients had a mean MS‐DRG weight of 1.15, which was slightly higher than that of usual care patients at 1.05 (P = 0.06). Typically, 70% of Hospitalist‐ACE patients are admitted to the designated ACE medical unit (12 West).

| Characteristic | Hospitalist‐ACE | Usual Care | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 122 | N = 95 | ||

| |||

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 80.5 (6.5) | 80.7 (7.0) | 0.86 |

| Gender (% female) | 52.5 | 59 | 0.34 |

| Case Mix Index (mean MS‐DRG weight [SD]) | 1.15 (0.43) | 1.05 (0.31) | 0.06 |

| Primary ICD‐9 diagnosis (%) | 0.59 | ||

| Pulmonary | 27.9 | 28.4 | |

| General medicine | 15.6 | 11.6 | |

| Surgery | 13.9 | 11.6 | |

| Cardiology | 9.8 | 6.3 | |

| Nephrology | 8.2 | 7.4 | |

Processes of Care

Processes of care for older patients are displayed in Table 3. Patients on the Hospitalist‐ACE service had recognition and treatment of abnormal functional status at a rate that was nearly double that of patients on the usual care services (68.9% vs 35.8%, P < 0.0001). In addition, patients on the Hospitalist‐ACE service were significantly more likely to have had recognition and treatment of any abnormal cognitive status (55.7% vs 40.0%, P = 0.02). When delirium was evaluated alone, the Hospitalist‐ACE patients were also more likely to have had recognition and treatment of delirium (27.1% vs 17.0%, P = 0.08), although this finding did not reach statistical significance.

| Measure | Percent of Hospitalist‐ACE Patients | Percent of Usual Care Patients | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 122 | N = 95 | ||

| |||

| Recognition and treatment of abnormal functional status | 68.9 | 35.8 | <0.0001 |

| Recognition and treatment of abnormal cognitive status* | 55.7 | 40.0 | 0.02 |

| Recognition and treatment of delirium | 27.1 | 17.0 | 0.08 |

| Documentation of resuscitation preferences | 95.1 | 91.6 | 0.3 |

| Do Not Attempt Resuscitation orders | 39.3 | 26.3 | 0.04 |

| Use of sleep medications | 28.1 | 27.4 | 0.91 |

| Use of physical restraints | 2.5 | 0 | 0.26 |

While patients on the Hospitalist‐ACE and usual care services had similar percentages of documentation of resuscitation preferences (95.1% vs 91.6%, P = 0.3), the percentage of Hospitalist‐ACE patients who had Do Not Attempt Resuscitation (DNAR) orders was significantly greater than that of the usual care patients (39.3% vs 26.3%, P = 0.04).

There were no differences in the use of physical restraints or sleep medications for Hospitalist‐ACE patients as compared to usual care patients, although the types of sleep mediations used on each service were markedly different: trazadone was employed as the first‐line sleep agent on the Hospitalist‐ACE service (77.7%), and non‐benzodiazepine hypnotics (primarily zolpidem) were employed most commonly on the usual care services (35%). There were no differences noted in the percentage of patients with benzodiazepines prescribed as sleep aids.

Outcomes

Resource utilization outcomes are reported in Table 4. Of note, there were no significant differences between Hospitalist‐ACE discharges and usual care discharges in mean length of stay (3.4 2.7 days vs 3.1 2.7 days, P = 0.52), mean charges ($24,617 15,828 vs $21,488 13,407, P = 0.12), or 30‐day readmissions to UCH (12.3% vs 9.5%, P = 0.51). Hospitalist‐ACE discharges and usual care patients were equally likely to be discharged to home (68.6% vs 67.4%, P = 0.84), with a similar proportion of Hospitalist‐ACE discharges receiving home health care or home hospice services (14.1% vs 7.4%, P = 12).

| Measure | Hospitalist‐ACE | Usual Care | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 122 | N = 95 | ||

| |||

| Length of stay in days (mean [SD]) | 3.4 (2.7) | 3.1 (2.7) | 0.52 |

| Charges in dollars (mean [SD]) | 24,617 (15,828) | 21,488 (13,407) | 0.12 |

| 30‐Day readmissions to UCH (%) | 12.3 | 9.5 | 0.51 |

| Discharges to home (%) | 68.8* | 67.4 | 0.84 |

| Discharges to home with services (%) | 14%* | 7.4% | 0.12 |

In addition, the fall rate for Hospitalist‐ACE patients was not significantly different from the fall rate for usual care patients (4.8 falls/1000 patient days vs 6.7 falls/1000 patient days, 95% confidence interval 9.613.3).

DISCUSSION

We report the implementation and evaluation of a medical service tailored to the care of the acutely ill older patient that draws from elements of the hospitalist model and the ACE unit model.7, 14, 24 For this Hospitalist‐ACE service, we developed a specialized hospitalist workforce, assembled a brief geriatric assessment tailored to the inpatient setting, instituted an interdisciplinary rounding model, and created a novel inpatient geriatrics curriculum.

During the study period, we improved performance of important processes of care for hospitalized elders, including recognition of abnormal cognitive and functional status; maintained comparable resource use; and implemented a novel, inpatient‐focused geriatric medicine educational experience. We were unable to demonstrate an impact on key clinical outcomes such as falls, physical restraint use, and readmissions. Nonetheless, there is evidence that the performance of selected processes of care is associated with improved three‐year survival status in the community‐dwelling vulnerable older patient, and may also be associated with a mortality benefit in the hospitalized vulnerable older patient.25, 26 Therefore, methods to improve the performance of these processes of care may be of clinical importance.

The finding of increased use of DNAR orders in the face of equivalent documentation of code status is of interest and generates hypotheses for further study. It is possible that the educational experience and use of geriatric assessment provides a more complete context for the code status discussion (one that incorporates the patient's social, physical, and cognitive function). However, we do not know if the patients on the ACE service had improved concordance between their code status and their goals of care.

We believe that there was no difference in key clinical outcomes between Hospitalist‐ACE and control patients because the population in this study was relatively low acuity and, therefore, the occurrence of falls and the use of physical restraints were quite low in the study population. In particular, the readmission rate was much lower than is typical for the Medicare population at our hospital, making it challenging to draw conclusions about the impact of the intervention on readmissions, however, we cannot rule out the possibility that our early discharge planning did not address the determinants of readmission for this population.

The ACE unit paradigmcharacterized by 1) closed, modified hospital units; 2) staffing by geriatricians and nurses with geriatrics training; 3) employing geriatric nursing care protocolsrequires significant resources and is not feasible for all settings.6 There is a need for alternative models of comprehensive care for hospitalized elders that require fewer resources in the form of dedicated units and specialist personnel, and can be more responsive to institutional needs. For example, in a 2005 report, one institution reported the creation of a geriatric medicine service that utilized a geriatrician and hospitalist co‐attending model.14 More recently, a large geriatrics program replaced its inpatient geriatrics unit with a mobile inpatient geriatrics service staffed by an attending geriatricianhospitalist, a geriatrics fellow, and a nurse practitioner.27 While these innovative models have eliminated the dedicated unit, they rely on board certified geriatricians, a group in short supply nationally.28 Hospitalists are a rapidly growing provider group that, with appropriate training and building on the work of geriatricians, is poised to provide leadership in acute geriatric care.29, 30

In contrast to the comprehensive inpatient geriatric care models described above, the Hospitalist‐ACE service uses a specialized hospitalist workforce and is not dependent on continuous staffing by geriatricians. Although geographic concentration is important for the success of interdisciplinary rounds, the Hospitalist‐ACE service does not require a closed or modified unit. The nursing staff caring for Hospitalist‐ACE patients have generalist nursing training and, at the time of the study, did not utilize geriatric‐care protocols. Our results need to be interpreted in the light of these differences from the ACE unit model which is a significantly more intensive intervention than the Hospitalist‐ACE service. In addition, the current practice environment is quite different from the mid‐1990s when ACE units were developed and studied. Development and maintenance of models of comprehensive inpatient geriatric care require demonstration of both value as well as return on investment. The alignment of financial and regulatory incentives for programs that provide comprehensive care to complex patients, such as those anticipated by the Affordable Care Act, may encourage the growth of such models.

These data represent findings from a six‐month evaluation of a novel inpatient service in the middle of its first year. There are several limitations related to our study design. First, the results of this small study at a single academic medical center may be of limited generalizability to other settings. Second, the program was evaluated only three months after its inception; we did not capture further improvements in methods, training, and outcomes expected as the program matured. Third, most of the Hospitalist‐ACE service attendings and residents rotate on the UCH general medical services throughout the year. Consequently, we were unable to eliminate the possibility of contamination of the control group, and we were unable to blind the physicians to the study. Fourth, the study population had a relatively low severity of illnessthe average MS‐DRG weight was near 1and low rates of important adverse events such falls and restraint use. This may have occurred because we excluded patients transferred from the ICUs and other services. It is possible that the Hospitalist‐ACE intervention might have demonstrated a larger benefit in a sicker population that would have presented greater opportunities for reductions in length of stay, costs, and adverse events. Fifth, given the retrospective nature of the data collection, we were not able to prospectively assess the incidence of important geriatric outcomes such as delirium and functional decline, nor can we make conclusions about changes in function during the hospitalization.

While the outcome measures we used are conceptually similar to several measures developed by RAND's Assessing Care of Vulnerable Elders (ACOVE) project, this study did not explicitly rely on those constructs.31 To do so would have required prospective screening by clinical staff independent from the care team for vulnerability that was beyond the scope of this project. In addition, the ACOVE measures of interest for functional and cognitive decline are limited to documentation of cognitive or functional assessments in the medical record. The ACE service's adoption of a brief standardized geriatric assessment was almost certain to meet that documentation requirement. While documentation is important, it is not clear that documentation, in and of itself, improves outcomes. Therefore, we expanded upon the ACOVE constructs to include the need for the additional evidence of a treatment plan when abnormal physical or cognitive function was documented. These constructs are important process of care for vulnerable elders. While we demonstrated improvements in several of these important processes of care for elderly patients, we are unable to draw conclusions about the impact of these differences in care on important clinical outcomes such as development of delirium, long‐term institutionalization, or mortality.

CONCLUSIONS

The risks of hospitalization for older persons are numerous, and present challenges and opportunities for inpatient physicians. As the hospitalized population agesmirroring national demographic trends and trends in use of acute care hospitalsthe challenge of avoiding harm in the older hospitalized patient will intensify. Innovations in care to improve the experience and outcomes of hospitalization for older patients are needed in the face of limited geriatrics‐trained workforce and few discretionary funds for unit redesign. The Hospitalist‐ACE service is a promising strategy for hospitalist programs with sufficient numbers of older patients and hospitalists with interest in improving clinical care for older adults. It provides a model for hospitalists to employ geriatrics principles targeted at reducing harm to their most vulnerable patients. Hospitalist‐run geriatric care models offer great promise for improving the care of acutely ill elderly patients. Future investigation should focus on demonstrating the impact of such care on important clinical outcomes between admission and discharge; on model refinement and adaptation, such as determining what components of comprehensive geriatric care are essential to success; and on how complementary interventions, such as the use of templated orders for the hospitalized elderly, impact outcomes. Additional research is needed, with a focus on demonstrating value with regard to an array of outcomes including cost, readmissions, and preventable harms of care.

Acknowledgements

Jean Kutner, MD, MSPH; Daniel Sandy, MPH; Shelly Limon, RN; nurses of 12 West; the UCH staff on the interdisciplinary team; and ACE patients and their families.

- ,,, et al.Functional outcomes of acute medical illness and hospitalization in older persons.Arch Intern Med.1996;156:645–652.

- ,,.Delirium: a symptom of how hospital care is failing older persons and a window to improve quality of hospital care.Am J Med.1999;106:565–573.

- ,,, et al.Using assessing care of vulnerable elders quality indicators to measure quality of hospital care for vulnerable elders.J Am Geriatr Soc.2007;55(11):1705–1711.

- ,,, et al.Impact and recognition of cognitive impairment among hospitalized elders.J Hosp Med.2010;5:69–75.

- ,,,,.What does the medical record reveal about functional status? A comparison of medical record and interview data.J Gen Intern Med.2001;16(11):728–736.

- ,,,,,.Successful models of comprehensive care for older adults with chronic conditions: evidence for the Institute of Medicine's “Retooling for an Aging America” report.J Am Geriatr Soc.2009;57(12):2328–2337.

- ,,,,.A randomized trial of care in a hospital medical unit especially designed to improve the functional outcomes of acutely ill older patients.N Engl J Med.1995;332:1338–1344.

- ,,, et al.Effects of a multicomponent intervention on functional outcomes and process of care in hospitalized older adults: a randomized controlled trial of Acute Care for Elders (ACE) in a community hospital.J Am Geriatr Soc.2000;48:1572–1581.

- ,,, et al.The effectiveness of inpatient geriatric evaluation and management units: a systematic review and meta‐analysis.J Am Geriatr Soc.2010;58:83–92.

- ,,,,.Effectiveness of acute geriatric units on functional decline, living at home, and case fatality among older patients admitted to hospital for acute medical disorders: meta‐analysis.BMJ.2009;338:b50.

- ,,, et al.A randomized, controlled clinical trial of a geriatrics consultation team: compliance with recommendations.JAMA.1986;255:2617–2621.

- ,,, et al.A multicomponent intervention to prevent delirium in hospitalized older patients.N Engl J Med.1999;340:669–676.

- ,,,.Dissemination and characteristics of Acute Care of Elders (ACE) units in the United States.Int J Technol Assess Health Care.2003;19:220–227.

- ,,.Is there a geriatrician in the house? Geriatric care approaches in hospitalist programs.J Hosp Med.2006;1:29–35.

- ,,,,.The Mini‐Cog: a cognitive “vital signs” measure for dementia screening in multi‐lingual elderly.Int J Geriatr Psychiatry.2000;15(11):1021–1027.

- ,,.The Patient Health Questionnaire‐2: validity of a two‐item depression screener.Med Care.2003;41:1284–1292.

- ,,,,,.Clarifying confusion: the Confusion Assessment Method.Ann Intern Med.1990;113(12):941–948.

- ,,, et al.The Vulnerable Elders Survey: a tool for identifying vulnerable older people in the community.J Am Geriatr Soc.2001;49:1691–1699.

- ,.The timed “Up and Go”: a test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons.J Am Geriatr Soc.1991;39:142–148.

- American Geriatrics Society, British Geriatrics Society, and American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons Panel on Falls Prevention.Guideline for the prevention of falls in older persons.J Am Geriatr Soc.2001;49:664–672.

- . Falls for the inpatient physician. Translating knowledge into action. The Portal of Online Geriatric Education (POGOe). 6–19‐2008. Available at: http://www.pogoe.org/productid/20212.

- ,,,. Incontinence and urinary catheters for the inpatient physician. The Portal of Online Geriatric Education (POGOe). 11–27‐0008. Available at: http://www.pogoe.org/productid/20296.

- ,,,.Use of medications for insomnia in the hospitalized geriatric population.J Am Geriatr Soc.2008;56(3):579–581.

- ,,,.Hospitalists and the practice of inpatient medicine: results of a survey of the National Association of Inpatient Physicians.Ann Intern Med.1999;130(4 pt 2):343–349.

- ,,, et al.Quality of care associated with survival in vulnerable older patients.Ann Intern Med.2005;143:274–281.

- ,,, et al.Higher quality of care for hosptialized frail older adults is associated with improved survival one year after discharge.J Hosp Med.2009;4(S1):24.

- ,,,.Operational and quality outcomes of a novel mobile acute care for the elderly service.J Am Geriatr Soc.2009;57:S1.

- Institute of Medicine (IOM).Retooling for an Aging America: Building the Health Care Workforce.Washington, DC:The National Academies Press;2008.

- ,,.Alternative solutions to the geriatric workforce deficit.Am J Med.2008;121:e23.

- ,,,,.Fulfilling the promise of hospital medicine: tailoring internal medicine training to address hospitalists' needs.J Gen Intern Med.2008;23(7):1110–1115.

- ,.Assessing care of vulnerable elders: ACOVE project overview.Ann Intern Med.2001;135(8 pt 2):642–646.

For the frail older patient, hospitalization marks a period of high risk of poor outcomes and adverse events including functional decline, delirium, pressure ulcers, adverse drug events, nosocomial infections, and falls.1, 2 Physician recognition of elderly patients at risk for adverse outcomes is poor, making it difficult to intervene to prevent them.3, 4 Among frail, elderly inpatients at an urban academic medical center, doctors documented cognitive assessments in only 5% of patients. Functional assessments are appropriately documented in 40%80% of inpatients.3, 5

The Acute Care for Elders (ACE) unit is one of several models of comprehensive inpatient geriatric care that have been developed by geriatrician researchers to address the adverse events and functional decline that often accompany hospitalization.6 The ACE unit model generally incorporates: 1) a modified hospital environment, 2) early assessment and intensive management to minimize the adverse effects of hospital care, 3) early discharge planning, 4) patient centered care protocols, and 5) a consistent nursing staff.7 Two randomized, controlled trials have shown the ACE unit model to be successful in reducing functional decline among frail older inpatients during and after hospitalization.7, 8 While meta‐analyses data also suggests the ACE unit model reduces functional decline and future institutionalization, significant impact on other outcomes is not proven.9, 10

Several barriers have prevented the successful dissemination of the ACE unit model. The chief limitations are the upfront resources required to create and maintain a modified, dedicated unit, as well as the lack of a geriatrics trained workforce.7, 1113 The rapid growth of hospital medicine presents opportunities for innovation in the care of older patients. Still, a 2006 census demonstrated that few hospitalist groups had identified geriatric care as a priority.14

In response to these challenges, the University of Colorado Hospital Medicine Group created a hospitalist‐run inpatient medical service designed for the care of the frail older patient. This Hospitalist‐Acute Care for the Elderly (Hospitalist‐ACE) unit is a hybrid of a general medical service and an inpatient geriatrics unit.7 The goals of the Hospitalist‐ACE service are to provide high quality care tailored to older inpatients, thus minimizing the risks of functional decline and adverse events associate with hospitalization, and to provide a clinical geriatrics teaching experience for Hospitalist Training Track Residents within the Internal Medicine Residency Training Program and medical students at the University of Colorado Denver School of Medicine. The Hospitalist‐ACE unit is staffed with a core group of hospitalist attendings who have, at a minimum, attended an intensive mini‐course in inpatient geriatrics. The service employs interdisciplinary rounds; a brief, standardized geriatric assessment including screens of function, cognition, and mood; a clinical focus on mitigating the hazards of hospitalization, early discharge planning; and a novel geriatric educational curriculum for medicine residents and medical students.

This article will: 1) describe the creation of the Hospitalist‐ACE service at the University of Colorado Hospital; and 2) summarize the evaluation of the Hospitalist‐ACE service in a quasi‐randomized, controlled manner during its first year. We hypothesized that, when compared to patients receiving usual care, patients cared for on the Hospitalist‐ACE service would have increased recognition of abnormal functional status; recognition of abnormal cognitive status and delirium; equivalent lengths of stay and hospital charges; and decreased falls, 30‐day readmissions, and restraint use.

METHODS

Design

We performed a quasi‐randomized, controlled study of the Hospitalist‐ACE service.

Setting

The study setting was the inpatient general medical services of the Anschutz Inpatient Pavilion (AIP) of the University of Colorado Hospital (UCH). The AIP is a 425‐bed tertiary care hospital that is the major teaching affiliate of the University of Colorado School of Medicine and a regional referral center. The control services, hereafter referred to as usual care, were comprised of the four inpatient general medicine teaching services that take admissions on a four‐day rotation (in general, two were staffed by outpatient general internists and medical subspecialists, and two were staffed by academic hospitalists). The Hospitalist‐ACE service was a novel hospitalist teaching service that began in July 2007. Hospitalist‐ACE patients were admitted to a single 12‐bed medical unit (12 West) when beds were available; 12 West is similar to the other medical/surgical units at UCH and did not have any modifications to the rooms, equipment, or common areas for the intervention. The nursing staff on this unit had no formal geriatric nursing training. The Hospitalist‐ACE team admitted patients daily (between 7 AM and 3 PM MondayFriday; between 7 AM and 12 noon Saturday and Sunday). Patients assigned to the Hospitalist‐ACE service after hours were admitted by the internal medicine resident on call for the usual care services and handed off to the Hospitalist‐ACE team at 7 AM the next morning.

Study Subjects

Eligible subjects were inpatients age 70 years admitted to the usual care or Hospitalist‐ACE services at the AIP from November 2, 2007 to April 15, 2008. All patients age 70 years were randomized to the Hospitalist‐ACE service or usual care on a general internal medicine service by the last digit of the medical record number (odd numbers admitted to the Hospitalist‐ACE service and even numbers admitted to usual care). Patients followed by the Hospitalist‐ACE service but not admitted to 12 West were included in the study. To isolate the impact of the intervention, patients admitted to a medicine subspecialty service (such as cardiology, pulmonary, or oncology), or transferred to or from the Hospitalist‐ACE or control services to another service (eg, intensive care unit [ICU] or orthopedic surgery service) were excluded from the study.

Intervention

The Hospitalist‐ACE unit implemented an interdisciplinary team approach to identify and address geriatric syndromes in patients aged 70 and over. The Hospitalist‐ACE model of care consisted of clinical care provided by a hospitalist attending with additional training in geriatric medicine, administration of standardized geriatric screens assessing function, cognition, and mood, 15 minute daily (MondayFriday) interdisciplinary rounds focusing on recognition and management of geriatric syndromes and early discharge planning, and a standardized educational curriculum for medical residents and medical students addressing hazards of hospitalization.

The Hospitalist‐ACE service was a unique rotation within the Hospitalist Training Track of the Internal Medicine Residency that was developed with the support of the University of Colorado Hospital and the Internal Medicine Residency Training Program, and input from the Geriatrics Division at the University of Colorado Denver. The director received additional training from the Donald W. Reynolds FoundationUCLA Faculty Development to Advance Geriatric Education Mini‐Fellowship for hospitalist faculty. The mission of the service was to excel at educating the next generation of hospitalists while providing a model for excellence of care for hospitalized elderly patients. Important stakeholders were identified, and a leadership teamincluding representatives from nursing, physical and occupational therapy, pharmacy, social work, case management, and later, volunteer servicescreated the model daily interdisciplinary rounds. As geographic concentration was essential for the viability of interdisciplinary rounds, one unit (12 West) within the hospital was designated as the preferred location for patients admitted to the Hospitalist‐ACE service.

The Hospitalist‐ACE unit team consisted of one attending hospitalist, one resident, one intern, and medical students. The attending was one of five hospitalists, with additional training in geriatric medicine, who rotated attending responsibilities on the service. One of the hospitalists was board certified in geriatric medicine. Each of the other four hospitalists attended the Reynolds FoundationUCLA mini‐fellowship in geriatric medicine. Hospitalist‐ACE attendings rotated on a variety of other hospitalist services throughout the academic year, including the usual care services.

The brief standardized geriatric assessment consisted of six validated instruments, and was completed by house staff or medical students on admission, following instruction by the attending physician. The complete assessment tool is shown in Figure 1. The cognitive items included the Mini‐Cog,15 a two‐item depression screen,16 and the Confusion Assessment Method.17 The functional items included the Vulnerable Elders Survey (VES‐13),18 the Timed Get Up and Go test,19 and a two‐question falls screen.20 The elements of the assessment tool were selected by the Hospitalist‐ACE attendings for brevity and the potential to inform clinical management. To standardize the clinical and educational approach, the Hospitalist‐ACE attendings regularly discussed appropriate orders recommended in response to each positive screen, but no templated order sets were used during the study period.

Interdisciplinary rounds were attended by Hospitalist‐ACE physicians, nurses, case managers, social workers, physical or occupational therapists, pharmacists, and volunteers. Rounds were led by the attending or medical resident.

The educational curriculum encompassed 13 modules created by the attending faculty that cover delirium, falls, dementia, pressure ulcers, physiology of aging, movement disorders, medication safety, end of life care, advance directives, care transitions, financing of health care for the elderly, and ethical conundrums in the care of the elderly. A full table of contents appears in online Appendix 1. Additionally, portions of the curriculum have been published online.21, 22 Topic selection was guided by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) core geriatrics topics determined most relevant for the inpatient setting. Formal instruction of 3045 minutes duration occurred three to four days a week and was presented in addition to routine internal medicine educational conferences. Attendings coordinated teaching to ensure that each trainee was exposed to all of the content during the course of their four‐week rotation.

In contrast to the Hospitalist‐ACE service, usual care on the control general medical services consisted of either a hospitalist, a general internist, or an internal medicine subspecialist attending physician, with one medical resident, one intern, and medical students admitting every fourth day. The general medical teams attended daily discharge planning rounds with a discharge planner and social worker focused exclusively on discharge planning. The content of teaching rounds on the general medical services was largely left to the discretion of the attending physician.

This program evaluation of the Hospitalist‐ACE service was granted a waiver of consent and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Primary Outcome

The primary outcome for the study was the recognition of abnormal functional status by the primary team. Recognition of abnormal functional status was determined from chart review and consisted of both the physician's detection of abnormal functional status and evidence of a corresponding treatment plan identified in the notes or orders of a physician member of the primary team (Table 1).

| Measure | Criterion | Source | Content Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Recognition of abnormal functional status* | 1) Detection | MD's documentation of history | Presentation with change in function (new gait instability); use of gait aides (wheelchair) |

| OR | |||

| MD's documentation of physical exam | Observation of abnormal gait (eg, unsteady, wide‐based, shuffling) and/or balance Abnormal Get Up and Go test | ||

| AND | |||

| 2) Treatment | MD's order | PT/OT consult; home safety evaluation | |

| OR | |||

| MD's documentation assessment/plan | Inclusion of functional status (rehabilitation, PT/OT needs) on the MD's problem list | ||

| Recognition of abnormal cognitive status | Any of the following: | ||

| Delirium | 1) Detection | MD's history | Presentation of confusion or altered mental status |

| OR | |||

| MD's physical exam | Abnormal confusion assessment method | ||

| AND | |||

| 2) Treatment | MD's order | Sitter, reorienting communication, new halperidol order | |

| OR | |||

| MD's documentation of assessment/plan | Inclusion of delirium on the problem list | ||

| OR | |||

| Dementia | 1) Detection | MD's history | Dementia in medical history |

| OR | OR | ||

| MD's physical exam | Abnormal Folstein Mini‐Mental Status Exam or Mini‐Cog | ||

| AND | |||

| 2) Treatment | MD's order | Cholinesterase inhibitor ordered | |

| OR | OR | ||

| MD's documentation of assessment/plan | Inclusion of dementia on the problem list | ||

| OR | |||

| Depression | 1) Detection | MD's history | Depression in medical history |

| OR | OR | ||

| MD's physical exam | Positive depression screen | ||

| AND | |||

| 2) Treatment | MD's order | New antidepressant order | |

| OR | |||

| MD's documentation of assessment/plan | Inclusion of depression on the problem list | ||

Secondary Outcomes

Recognition of abnormal cognitive status was determined from chart review and consisted of both the physician's detection of dementia, depression, or delirium, and evidence of a corresponding treatment plan for any of the documented conditions identified in the notes or orders of a physician member of the primary team (Table 1). Additionally, we measured recognition and treatment of delirium alone.

Falls were determined from mandatory event reporting collected by the hospital on the University Hospitals Consortium Patient Safety Net web‐based reporting system and based on clinical assessment as reported by the nursing staff. The reports are validated by the appropriate clinical managers within 45 days of the event according to standard procedure.

Physical restraint use (type of restraint and duration) was determined from query of mandatory clinical documentation in the electronic medical record. Use of sleep aids was determined from review of the physician's order sheets in the medical record. The chart review captured any of 39 commonly prescribed hypnotic medications ordered at hour of sleep or for insomnia. The sleep medication list was compiled with the assistance of a pharmacist for an earlier chart review and included non‐benzodiazepine hypnotics, benzodiazepines, antidepressants, antihistamines, and antipsychotics.23

Length of stay, hospital charges, 30‐day readmissions to UCH (calculated from date of discharge), and discharge location were determined from administrative data.

Additional Descriptive Variables

Name, medical record number, gender, date of birth, date of admission and discharge, and primary diagnosis were obtained from the medical record. The Case Mix Index for each group of patients was determined from the average Medicare Severity‐adjusted Diagnosis Related Group (MS‐DRG) weight obtained from administrative data.

Data Collection

A two‐step, retrospective chart abstraction was employed. A professional research assistant (P.R.A.) hand‐abstracted process measures from the paper medical chart onto a data collection form designed for this study. A physician investigator performed a secondary review (H.L.W.). Discrepancies were resolved by the physician reviewer.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were performed on intervention and control subjects. Means and standard deviations (age) or frequencies (gender, primary diagnoses) were calculated as appropriate. T tests were used for continuous variables, chi‐square tests for gender, and the Wilcoxon rank sum test for categorical variables.

Outcomes were reported as means and standard deviations for continuous variables (length of stay and charges) and frequencies for categorical variables (all other outcomes). T tests were used for continuous variables, Fisher's exact test for restraint use, and chi‐square tests were used for categorical variable to compare the impact of the intervention between intervention and control patients. For falls, confidence intervals were calculated for the incidence rate differences based on Poisson approximations.

Sample Size Considerations

An a priori sample size calculation was performed. A 2001 study showed that functional status is poorly documented in at least 60% of hospital charts of elderly patients.5 Given an estimated sample size of 120 per group and a power of 80%, this study was powered to be able to detect an absolute difference in the documentation of functional status of as little as 18%.

RESULTS

Two hundred seventeen patients met the study entry criteria (Table 2): 122 were admitted to the Hospitalist‐ACE service, and 95 were admitted to usual care on the general medical services. The average age of the study patients was 80.5 years, 55.3% were female. Twenty‐eight percent of subjects were admitted for pulmonary diagnoses. The two groups of patients were similar with respect to age, gender, and distribution of primary diagnoses. The Hospitalist‐ACE patients had a mean MS‐DRG weight of 1.15, which was slightly higher than that of usual care patients at 1.05 (P = 0.06). Typically, 70% of Hospitalist‐ACE patients are admitted to the designated ACE medical unit (12 West).

| Characteristic | Hospitalist‐ACE | Usual Care | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 122 | N = 95 | ||

| |||

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 80.5 (6.5) | 80.7 (7.0) | 0.86 |

| Gender (% female) | 52.5 | 59 | 0.34 |

| Case Mix Index (mean MS‐DRG weight [SD]) | 1.15 (0.43) | 1.05 (0.31) | 0.06 |

| Primary ICD‐9 diagnosis (%) | 0.59 | ||

| Pulmonary | 27.9 | 28.4 | |

| General medicine | 15.6 | 11.6 | |

| Surgery | 13.9 | 11.6 | |

| Cardiology | 9.8 | 6.3 | |

| Nephrology | 8.2 | 7.4 | |

Processes of Care

Processes of care for older patients are displayed in Table 3. Patients on the Hospitalist‐ACE service had recognition and treatment of abnormal functional status at a rate that was nearly double that of patients on the usual care services (68.9% vs 35.8%, P < 0.0001). In addition, patients on the Hospitalist‐ACE service were significantly more likely to have had recognition and treatment of any abnormal cognitive status (55.7% vs 40.0%, P = 0.02). When delirium was evaluated alone, the Hospitalist‐ACE patients were also more likely to have had recognition and treatment of delirium (27.1% vs 17.0%, P = 0.08), although this finding did not reach statistical significance.

| Measure | Percent of Hospitalist‐ACE Patients | Percent of Usual Care Patients | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 122 | N = 95 | ||

| |||