User login

Hospitalist Value in an ACO World

The accountable care organization (ACO) concept, elucidated in 2006 as the development of partnerships between hospitals and physicians to coordinate and deliver efficient care,1 seeks to remove existing barriers to improving value.2 Some advocate this concept as a promising payment model that could successfully realign the current payment system to financially reward improvements in quality and efficiency that bend the cost curve.3,4 Hospitalists fit well with this philosophy. As the fastest growing medical specialty in the history of American medicine, from a couple of thousand hospitalists in the mid-1990s to more than 50,000, the remarkable progression of hospitalists has ostensibly been driven partially by hospitals’ efforts to improve the value equation through enhanced efficiency in inpatient care. Importantly, hospitalists probably provide care for more than half of all hospitalized Medicare beneficiaries and increasingly patients in skilled nursing facilities (ie, SNFists).5 Along with primary care physicians, hospitalists thus represent an essential group of physicians needed to transform care delivery.

RAPID GROWTH AND THE FUTURE OF ACOs

When the Affordable Care Act (ACA) established the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP), ACOs leaped from being an intellectual concept1,2 into a pragmatic health system strategy.3,4 Following Medicare, various private health insurance plans and some state Medicaid programs entered into contracts with groups of healthcare providers (hospitals, physicians, or health systems) to serve as ACOs for their insured enrollees.6 Leavitt Partners’ ACO tracking database showed that the number of ACOs increased from 157 in March of 2012 to 782 in December of 2015.7

Until recently, the federal government’s commitment to having 50% of total Medicare spending via value-based payment models by 2018, coupled with endorsement from state Medicaid programs and commercial insurers, demonstrated strong support for continuation of ACOs. Unexpectedly on August 15, 2017, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) outlined a plan in its proposed rulemaking to cancel the Episode Payment Models and the Cardiac Rehabilitation incentive payment model, which were scheduled to commence on January 1, 2018. CMS also plans to scale back the mandatory Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement (CCJR) bundled payment model from 67 selected geographic areas to 34. Although this proposed rulemaking created some equipoise in the healthcare industry regarding the future of value-based reimbursement approaches, cost containment and improved efficiency remain as major focuses of the federal government’s healthcare effort. Notably, CMS offers providers that are newly excluded from the CCJR model the opportunity to voluntarily participate in the program and is expected to increase opportunities for providers to participate in voluntary rather than large-scale mandatory episode payment model initiatives. In 2018, the agency also plans to develop new voluntary bundled payment models that will meet criteria to be considered an advanced alternative payment model for Quality Payment Program purposes.

Importantly, the value-based reimbursement movement was well underway before ACA legislation. Through ACA health reform, value-based reimbursement efforts were expanded through ACOs, bundled payments, value-based purchasing, the CMS Innovation Center and other initiatives. With health systems having an overflowing plate of activities, a wait-and-see attitude might seem reasonable at first. However, being unprepared for the inevitable shift to value-based reimbursement and reduced fee-for-service revenue places an organization at risk. A successful ACO requires system-level transformation, especially cultural and structural changes to achieve clinical integration. Being embedded in health system delivery, hospitalists can help shape a team-oriented culture and foster success in value-based payment models. This requires hospitalists to take a more active role in assessing and striking a balance between high-quality, cost-efficient care and financial risk inherent in ACO models.

WHAT HOSPITALISTS NEED TO KNOW ABOUT ACOs

The key to hospitalists fulfilling their value creation potential and becoming enablers for ACO success lies in developing a thorough understanding of the aspects of an ACO that promote efficient and effective care, while accounting for financial factors. Fundamentally, the ACO concept combines provider payment and delivery system reforms. Specifically, the definition of an ACO contains 3 factors: (1) a local healthcare organization (eg, hospital or multispecialty group of physicians) with a related set of providers that (2) can be held accountable for the cost and quality of care delivered to (3) a defined population. While the notion of accountability is not new, the locus of accountability is changed in the ACO model—emphasizing accountability at the level of actual care delivery with documentation of quality and cost outcomes. The ACO approach aims to address multiple, frequent, and recurring problems, including lack of financial incentives to improve quality and reduce cost, as well as the negative consequences of a pay-for-volume system—uncoordinated and fragmented care, overutilization of unnecessary tests and treatments, and poor patient experience all manifested as unwarranted geographic variation in practice patterns, clinical outcomes, and health spending. Participants in an ACO are rewarded financially if they can slow the growth of their patients’ healthcare costs while maintaining or improving the quality of care delivered. To succeed in this ACO world, hospitalists must assume greater prudence in the use of healthcare services while improving (or at a minimum, maintaining) patient outcomes, thus excising avoidable waste across the continuum of care.

More than half of ACOs include a hospital.8 However, whether hospital-led ACOs possess an advantage remains to be elucidated. Early reports indicated that physician-led ACOs saved more money.9,10 However, others argue that hospitals11 are better capitalized, have greater capacity for data sharing, and possess economies of scale that allow them to invest in more advanced technology, such as predictive modeling and/or simulation software. Such analytics can identify high-cost patients (ie, multiple comorbidities), super utilizers and populations lacking care, allowing ACOs to implement preventive measures to reduce unnecessary utilization. Recently released CMS MSSP 2016 performance data12 showed that nearly half (45%) of physician-only ACOs earned shared savings, whereas 23% of ACOs that include hospitals earned shared savings. However, among all the ACOs that achieved savings, ACO entities that include hospitals generated the highest amount of shared savings (eg, Advocate, Hackensack Alliance, Cleveland Clinic, and AMITA Health). Notably, hospital-led ACOs tend to have much larger beneficiary populations than physician-led ACOs, which may create a scenario of higher risk but higher potential reward.

HOW HOSPITALISTS CONTRIBUTE VALUE TO ACO SUCCESS

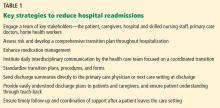

The emphasis on value over volume inherent in the development of ACOs occurs through employing care strategies implemented through changes in policies, and eventual structural and cultural changes. These changes require participating organizations to possess certain key competencies, including the following: 1) leadership that facilitates change; 2) organizational culture of teamwork; 3) collaborative relationships among providers; 4) information technology infrastructure for population management and care coordination; 5) infrastructure for monitoring, managing, and reporting quality; 6) ability to manage financial risk; 7) ability to receive and distribute payments or savings; and 8) resources for patient education and support.2,3,13-16 Table 1 summarizes the broad range of roles that hospitalists can serve in delivering care to ACO populations.17-19

Hospitalists’ active pursuit of nonclinical training and selection for administrative positions demonstrate their proclivity to provide these competencies. In addition to full-time clinician hospitalists, who can directly influence the delivery of high-value care to patients, hospitalists serve many other roles in hospitals and each can contribute differently based on their specialized expertise. Examples include the success of the Society of Hospital Medicine’s Leadership Academy; the acknowledged expertise of hospitalists in quality improvement (QI), informatics, teamwork, patient experience, care coordination and utilization; and advancement of hospitalists to senior leadership positions (eg, CQO, CMO, CEO). Given that nearly a third of healthcare expenditures are for hospital care,20 hospitalists are in a unique position to foster ACO competencies while impacting the quality of care episodes associated with an index hospital stay.

Importantly, hospitalists cannot act as gatekeepers to restrict care. Managed care organizations and health maintenance organizations use of this approach in the 1990s to limit access to services in order to reduce costs led to unacceptable outcomes and numerous malpractice lawsuits. ACOs should aspire to deliver the most cost-effective high-quality care, and their performance should be monitored to ensure that they provide recommended services and timely access. The Medicare ACO contract holds the provider accountable for meeting 34 different quality measures (Supplemental Table 1), and hospitalists can influence outcomes for the majority. Especially through hospital and health system QI initiatives, hospitalists can directly impact and share accountability for measures ranging from care coordination to implementation of evidence-based care (eg, ACE inhibitors and beta blockers for heart failure) to patient and family caregiver experience.

Aligned with Medicare ACO quality measures, 5 high-impact target areas were identified for ACOs21: (1) Prevention and wellness; (2) Chronic conditions/care management; (3) Reduced hospitalizations; (4) Care transitions across the fragmented system; and (5) Multispecialty care coordination of complex patients. One essential element of a successful ACO is the ability to implement evidence-based medical guidelines and/or practices across the continuum of care for selected targeted initiatives. Optimizing care coordination/continuum requires team-based care, and hospitalists already routinely collaborate with nurses, social workers, case managers, pharmacists, and other stakeholders such as dieticians and physical therapists on inpatient care. Hospitalists are also experienced in facilitating communication and improving integration and coordination efficiencies among primary care providers and specialists, and between hospital care and post-acute care, as they coordinate post-hospital care and follow-up. This provides an opportunity to lead health system care coordination efforts, especially for complex and/or high-risk patients.22,23 CMS MSSP 2016 performance data12 showed that ACOs achieving shared savings had a decline in inpatient expenditures and utilization across several facility types (hospital, SNF, rehabilitation, long term). Postacute care management is critical to earning shared savings; SNF and Home Health expenditures fell by 18.3% and 9.7%, respectively, on average. We believe that hospitalists can have more influence over these cost areas by influencing treatment of hospitalized patients in a timely manner, discharge coordination, and selection of appropriate disposition locations. Hospitalists also play an integral role in ensuring the hospital performs well on quality metrics, including 30-day readmissions, hospital acquired conditions, and patient satisfaction. Examples below document the effectiveness of hospitalists in this new ACO era.

Care Transitions/Coordination

Before the Hospital Readmission Reduction Program (HRRP) delineated in the ACA, hospitalists developed Project BOOST (Better Outcomes by Optimizing Care Transitions) to improve hospital discharge care transition. The evidence-based foundation of this project led CMS to list Project BOOST as an example program that can reduce readmissions.24 Through the dissemination and mentored implementation of Project BOOST to over 200 hospitals across the United States,25 hospitalists contributed to the marked reduction in hospital readmission occurring since 2010.26 Although hospital medicine began as a practice specific to the hospital setting, hospitalists’ skills generated growing demand for them in postacute facilities. SNF residents commonly come from hospitals postdischarge and suffer from multiple comorbidities and limitations in activities of daily living. Not surprisingly, SNF residents experience high rates of rehospitalizations.27 Hospitalists can serve as a bridge between hospitals and SNFs and optimize this transition process to yield improved outcomes. Industry experts endorse this approach.28 A recent study demonstrated a significant reduction in readmissions in 1 SNF (32.3% to 16.1%, odds ratio = 0.403, P < .001), by having a hospitalist-led team follow patients discharged from the hospital.29

Chronic Conditions Management/High-Risk Patients

Interest in patients with multiple chronic comorbidities and social issues intensifies as healthcare systems focus limited resources on these high-risk patients to prevent the unnecessary use of costly services.30,31 As health systems assume financial risk for health outcomes and costs of designated patient groups, they undertake efforts to understand the population they serve. Such efforts aim to identify patients with established high utilization patterns (or those at risk for high utilization). This knowledge enables targeted actions to provide access, treatment, and preventive interventions to avoid unneeded emergency and hospital services. Hospitalists commonly care for these patients and are positioned to lead the implementation of patient risk assessment and stratification, develop patient-centered care models across care settings, and act as a liaison with primary care. For frail elderly and seriously ill patients, the integration of hospitalists into palliative care provides several opportunities for improving the quality of care at the end of life.32 As patients and their family caregivers commonly do not address goals of care until faced with a life-threatening condition in the hospital, hospitalists represent ideal primary palliative care physicians to initiate these conversations.33 A hospitalist communicating with a patient and/or their family caregiver about alleviating symptoms and clarifying patients’ preferences for care often yields decreases in ineffective healthcare utilization and better patient outcomes. The hospitalists’ ability to communicate with other providers within the hospital setting also allows them to better coordinate interdisciplinary care and prevent unnecessary and ineffective treatments and procedures.

De-Implementation/Waste Reduction

The largest inefficiencies in healthcare noted in the National Academy of Medicine report, Demanding Value from Our Health Care (2012), are failure to deliver known beneficial therapies or providing unnecessary or nonevidenced based services that do not improve outcomes, but come with associated risk and cost.34 “De-implementation” of unnecessary diagnostic tests or ineffective or even harmful treatments by hospitalists represents a significant opportunity to reduce costs while maintaining or even improving the quality of care. The Society of Hospital Medicine joined the Choosing Wisely® campaign and made 5 recommendations in adult care as an explicit starting point for eliminating waste in the hospital in 2013.35 Since then, hospitalists have participated in multiple successful efforts to address overutilization of care; some published results include the following:

- decreased frequency of unnecessary common labs through a multifaceted hospitalist QI intervention;36

- reduced length of stay and cost by appropriate use of telemetry;37 and

- reduced unnecessary radiology testing by providing physicians with individualized audit and feedback reports.38

CONCLUSION

Hundreds of ACOs now exist across the US, formed by a variety of providers including hospitals, physician groups, and integrated delivery systems. Provider groups range in size from primary care-focused physician groups with a handful of offices to large, multistate integrated delivery systems with dozens of hospitals and hundreds of office locations. Evaluations of ACO outcomes reveal mixed results.9,39-53 Admittedly, assessments attempting to compare the magnitude of savings across ACO models are difficult given the variation in size, variability in specific efforts to influence utilization, and substantial turnover among participating beneficiaries.54 Nonetheless, a newly published Office of Inspector General report55 showed that most Medicare ACOs reduced spending and improved care quality (82% of the individual quality measures) over the first 3 years of the program, and savings increased with duration of an ACO program. The report also noted that considerable time and managerial resources are required to implement changes to improve quality and lower costs. While the political terrain ostensibly supports value-based care and the need to diminish the proportion of our nation’s gross domestic product dedicated to healthcare, health systems are navigating an environment that still largely rewards volume. Hospitalists may be ideal facilitators for this transitional period as they possess the clinical experience caring for complex patients with multiple comorbidities and quality improvement skills to lead efforts in this new ACO era.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

1. Fisher ES, Staiger DO, Bynum JP, Gottlieb DJ. Creating accountable care organizations: the extended hospital medical staff. Health Aff(Project Hope). 2007;26(1):w44-w57. PubMed

2. Fisher ES, McClellan MB, Bertko J, et al. Fostering accountable health care: moving forward in medicare. Health Aff(Project Hope). 2009;28(2):w219-w231. PubMed

3. McClellan M, McKethan AN, Lewis JL, Roski J, Fisher ES. A national strategy to put accountable care into practice. Health Aff(Project Hope). 2010;29(5):982-990. PubMed

4. Berwick DM. Making good on ACOs’ promise--the final rule for the Medicare shared savings program. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(19):1753-1756. PubMed

5. Kuo YF, Sharma G, Freeman JL, Goodwin JS. Growth in the care of older patients by hospitalists in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(11):1102-1112. PubMed

6. Kennedy K. Health Care Providers Embracing Cost-saving Groups. USA Today, July 24, 2011.

7. Leavitt Partners. Available at http://leavittpartners.com, April 2016.

8. Colla CH, Lewis VA, Tierney E, Muhlestein DB. Hospitals Participating In ACOs Tend To Be Large And Urban, Allowing Access To Capital And Data. Health Aff(Millwood). 2016;35(3):431-439. PubMed

9. McWilliams JM, Hatfield LA, Chernew ME, Landon BE, Schwartz AL. Early Performance of Accountable Care Organizations in Medicare. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(24):2357-2366. PubMed

10. Muhlestein D, Saunders R, McClellan M. Medicare Accountable Care Organization Results For 2015: The Journey To Better Quality And Lower Costs Continues. In. Health Affairs Blog. Bethesda, MD 2016.

11. Chernew ME. New Health Care Symposium: Building An ACO---What Services Do You Need And How Are Physicians Impacted? In Health Affairs Blog. Bethesda, MD 2016.

12. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Performance Year 2016 Quality Performance and Financial Reconciliation Results for ACOs with 2012-2016 Start Dates. Available at https://strategichealthcare.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/CMS-Slides-on-ACOs.pdf. 2017.

13. Shortell SM, Casalino LP. Implementing qualifications criteria and technical assistance for accountable care organizations. JAMA. 2010;303(17):1747-1748. PubMed

14. Shortell SM, Casalino LP, Fisher ES. How the center for Medicare and Medicaid innovation should test accountable care organizations. Health Aff (Project Hope). 2010;29(7):1293-1298. PubMed

15. Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Accountable Care Organizations Payment Systems October 2015. Available at http://www.medpac.gov/documents/payment-basics/accountable-care-organization-payment-systems-15.pdf?sfvrsn=0.

16. American Hospital Association. 2010 Committee on Research. AHA Research Synthesis Report: Accountable Care Organization.

17. D’Aunno T, Broffman L, Sparer M, Kumar SR. Factors That Distinguish High-Performing Accountable Care Organizations in the Medicare Shared Savings Program. Health Serv. Res. 2016. PubMed

18. Peiris D, Phipps-Taylor MC, Stachowski CA, et al. ACOs Holding Commercial Contracts Are Larger And More Efficient Than Noncommercial ACOs. Health Aff (Project Hope). 2016;35(10):1849-1856. PubMed

19. Ouayogode MH, Colla CH, Lewis VA. Determinants of success in Shared Savings Programs: An analysis of ACO and market characteristics. Healthcare (Amsterdam, Netherlands). 2017;5(1-2):53-61. PubMed

20. National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2016: With Chartbook on Long-term Trends in Health. In: Hyattsville, MD.2017. PubMed

21. Gbemudu JN. Larson BK, Van Citters AD, Kreindler SA, Nelson EC, Shortell SM, Fisher ES. Norton Healthcare: A Strong Payer–Provider Partnership for the Journey to Accountable Care. January 2012. Available at http://www.commonwealthfund.org/~/media/files/publications/case-study/2012/jan/1574_gbemudu_norton_case-study_01_12_2012.pdf.

22. O’Leary KJ, Haviley C, Slade ME, Shah HM, Lee J, Williams MV. Improving teamwork: impact of structured interdisciplinary rounds on a hospitalist unit. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(2):88-93. PubMed

23. Hansen LO, Greenwald JL, Budnitz T, et al. Project BOOST: effectiveness of a multihospital effort to reduce rehospitalization. J. Hosp. Med.. 2013;8(8):421-427. PubMed

24. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Solicitation for Applications: Community-based Care Transitions Program. Available at https://innovation.cms.gov/Files/Migrated-Medicare-Demonstration-x/CCTP-Solicitation.pdf. September 7, 2017.

25. Li J, Hinami K, Hansen LO, Maynard G, Budnitz T, Williams MV. The physician mentored implementation model: a promising quality improvement framework for health care change. Acad Med. 2015;90(3):303-310. PubMed

26. Williams MV, Li J, Hansen LO, et al. Project BOOST implementation: lessons learned. South Med J. 2014;107(7):455-465. PubMed

27. Ouslander JG, Lamb G, Perloe M, et al. Potentially avoidable hospitalizations of nursing home residents: frequency, causes, and costs: [see editorial comments by Drs. Jean F. Wyman and William R. Hazzard, pp 760-761]. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(4):627-635. PubMed

28. Pittman D. SNFs: New Turf for Hospitalists? 2013. Available at https://www.medpagetoday.com/hospitalbasedmedicine/hospitalists/39401.

29. Petigara S, Krishnamurthy M, Livert D. Necessity is the mother of invention: an innovative hospitalist-resident initiative for improving quality and reducing readmissions from skilled nursing facilities. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2017;7(2):66-69. PubMed

30. Silow-Carroll S, Edwards J. Early Adopters of the Accountable Care Model: A Field Report on Improvements in Health Care Delivery. New York, NY: The Commonwealth Fund;March 2013.

31. Hasselman D. Super-Utilizer Summit: Common Themes from Innovative Complex Care Management Programs. Hamilton, NJ: Center for Health Care Strategies;October 2013.

32. Wald HL, Glasheen JJ, Guerrasio J, Youngwerth JM, Cumbler EU. Evaluation of a hospitalist-run acute care for the elderly service. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(6):313-321. PubMed

33. Quill TE, Abernethy AP. Generalist plus specialist palliative care--creating a more sustainable model. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(13):1173-1175. PubMed

34. O’Kane M, Buto K, Alteras T, et. al. Demanding Value from Our Health Care: Motivating Patient Action to Reduce Waste in Health Care. Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. July 2012. https://nam.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/VSRT-DemandingValue.pdf. Accessed Accessed June 18, 2017.

35. Bulger J, Nickel W, Messler J, et al. Choosing wisely in adult hospital medicine: five opportunities for improved healthcare value. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(9):486-492. PubMed

36. Corson AH, Fan VS, White T, et al. A multifaceted hospitalist quality improvement intervention: Decreased frequency of common labs. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(6):390-395. PubMed

37. Svec D, Ahuja N, Evans KH, et al. Hospitalist intervention for appropriate use of telemetry reduces length of stay and cost. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(9):627-632. PubMed

38. Neeman N, Quinn K, Soni K, Mourad M, Sehgal NL. Reducing radiology use on an inpatient medical service: choosing wisely. JAMA Intern Med. 2012;172(20):1606-1608. PubMed

39. Abrams M, Nuzum R, Zezza M, Ryan J, Kiszla J, Guterman S. The Affordable Care Act’s Payment and Delivery System Reforms: A Progress Report at Five Years. Bipartisan Policy Center, May 2015. Available at http://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2015/may/aca-payment-and-delivery-system-reforms-at-5-years.

40. Kocot SL, White R, Katikaneni P, McClellan MB. A More Complete Picture of Pioneer ACO Results. The Brookings Institution, October 13, 2014. Available at http://www.brookings.edu/blogs/up-front/posts/2014/10/09-pioneer-aco-results-mcclellan/#recent_rr/

41. Blumenthal D, Abrams M, Nuzum R. The Affordable Care Act at 5 Years. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(25):2451-2458. PubMed

42. Colla CH, Lewis VA, Kao LS, O’Malley AJ, Chang CH, Fisher ES. Association Between Medicare Accountable Care Organization Implementation and Spending Among Clinically Vulnerable Beneficiaries. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(8):1167-1175. PubMed

43. Epstein AM, Jha AK, Orav EJ, et al. Analysis of early accountable care organizations defines patient, structural, cost, and quality-of-care characteristics. Health Aff (Project Hope). 2014;33(1):95-102. PubMed

44. Fullerton CA, Henke RM, Crable E, Hohlbauch A, Cummings N. The Impact Of Medicare ACOs On Improving Integration And Coordination Of Physical And Behavioral Health Care. Health Aff (Project Hope). 2016;35(7):1257-1265. PubMed

45. Herrel LA, Norton EC, Hawken SR, Ye Z, Hollenbeck BK, Miller DC. Early impact of Medicare accountable care organizations on cancer surgery outcomes. Cancer. 2016;122(17):2739-2746. PubMed

46. McConnell KJ, Renfro S, Chan BK, et al. Early Performance in Medicaid Accountable Care Organizations: A Comparison of Oregon and Colorado. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(4):538-545. PubMed

47. Nyweide DJ, Lee W, Cuerdon TT, et al. Association of Pioneer Accountable Care Organizations vs traditional Medicare fee for service with spending, utilization, and patient experience. JAMA. 2015;313(21):2152-2161. PubMed

48. Rajkumar R, Press MJ, Conway PH. The CMS Innovation Center--a five-year self-assessment. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(21):1981-1983. PubMed

49. Rose S, Zaslavsky AM, McWilliams JM. Variation In Accountable Care Organization Spending And Sensitivity To Risk Adjustment: Implications For Benchmarking. Health affairs (Project Hope). 2016;35(3):440-448. PubMed

50. Shortell SM, Poon BY, Ramsay PP, et al. A Multilevel Analysis of Patient Engagement and Patient-Reported Outcomes in Primary Care Practices of Accountable Care Organizations. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(6):640-647. PubMed

51. Winblad U, Mor V, McHugh JP, Rahman M. ACO-Affiliated Hospitals Reduced Rehospitalizations From Skilled Nursing Facilities Faster Than Other Hospitals. Health Aff (Project Hope). 2017;36(1):67-73. PubMed

52. Zhang Y, Caines KJ, Powers CA. Evaluating the Effects of Pioneer Accountable Care Organizations on Medicare Part D Drug Spending and Utilization. Med Care. 2017;55(5):470-475. PubMed

53. Muhlestein D. Medicare ACOs: Mixed Initial Results and Cautious Optimism. Health Affairs Blog, February 4, 2014. Available at http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2014/02/04/medicare-acos-mixed-initial-results-and-cautious-optimism/.

54. Hsu J, Price M, Vogeli C, et al. Bending The Spending Curve By Altering Care Delivery Patterns: The Role Of Care Management Within A Pioneer ACO. Health Aff (Project Hope). 2017;36(5):876-884. PubMed

55. Medicare Shared Savings Program Accountable Care Organizations Have Shown Potential For Reducing Spending And Improving Quality. Office of Inspector General;August 2017.

The accountable care organization (ACO) concept, elucidated in 2006 as the development of partnerships between hospitals and physicians to coordinate and deliver efficient care,1 seeks to remove existing barriers to improving value.2 Some advocate this concept as a promising payment model that could successfully realign the current payment system to financially reward improvements in quality and efficiency that bend the cost curve.3,4 Hospitalists fit well with this philosophy. As the fastest growing medical specialty in the history of American medicine, from a couple of thousand hospitalists in the mid-1990s to more than 50,000, the remarkable progression of hospitalists has ostensibly been driven partially by hospitals’ efforts to improve the value equation through enhanced efficiency in inpatient care. Importantly, hospitalists probably provide care for more than half of all hospitalized Medicare beneficiaries and increasingly patients in skilled nursing facilities (ie, SNFists).5 Along with primary care physicians, hospitalists thus represent an essential group of physicians needed to transform care delivery.

RAPID GROWTH AND THE FUTURE OF ACOs

When the Affordable Care Act (ACA) established the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP), ACOs leaped from being an intellectual concept1,2 into a pragmatic health system strategy.3,4 Following Medicare, various private health insurance plans and some state Medicaid programs entered into contracts with groups of healthcare providers (hospitals, physicians, or health systems) to serve as ACOs for their insured enrollees.6 Leavitt Partners’ ACO tracking database showed that the number of ACOs increased from 157 in March of 2012 to 782 in December of 2015.7

Until recently, the federal government’s commitment to having 50% of total Medicare spending via value-based payment models by 2018, coupled with endorsement from state Medicaid programs and commercial insurers, demonstrated strong support for continuation of ACOs. Unexpectedly on August 15, 2017, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) outlined a plan in its proposed rulemaking to cancel the Episode Payment Models and the Cardiac Rehabilitation incentive payment model, which were scheduled to commence on January 1, 2018. CMS also plans to scale back the mandatory Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement (CCJR) bundled payment model from 67 selected geographic areas to 34. Although this proposed rulemaking created some equipoise in the healthcare industry regarding the future of value-based reimbursement approaches, cost containment and improved efficiency remain as major focuses of the federal government’s healthcare effort. Notably, CMS offers providers that are newly excluded from the CCJR model the opportunity to voluntarily participate in the program and is expected to increase opportunities for providers to participate in voluntary rather than large-scale mandatory episode payment model initiatives. In 2018, the agency also plans to develop new voluntary bundled payment models that will meet criteria to be considered an advanced alternative payment model for Quality Payment Program purposes.

Importantly, the value-based reimbursement movement was well underway before ACA legislation. Through ACA health reform, value-based reimbursement efforts were expanded through ACOs, bundled payments, value-based purchasing, the CMS Innovation Center and other initiatives. With health systems having an overflowing plate of activities, a wait-and-see attitude might seem reasonable at first. However, being unprepared for the inevitable shift to value-based reimbursement and reduced fee-for-service revenue places an organization at risk. A successful ACO requires system-level transformation, especially cultural and structural changes to achieve clinical integration. Being embedded in health system delivery, hospitalists can help shape a team-oriented culture and foster success in value-based payment models. This requires hospitalists to take a more active role in assessing and striking a balance between high-quality, cost-efficient care and financial risk inherent in ACO models.

WHAT HOSPITALISTS NEED TO KNOW ABOUT ACOs

The key to hospitalists fulfilling their value creation potential and becoming enablers for ACO success lies in developing a thorough understanding of the aspects of an ACO that promote efficient and effective care, while accounting for financial factors. Fundamentally, the ACO concept combines provider payment and delivery system reforms. Specifically, the definition of an ACO contains 3 factors: (1) a local healthcare organization (eg, hospital or multispecialty group of physicians) with a related set of providers that (2) can be held accountable for the cost and quality of care delivered to (3) a defined population. While the notion of accountability is not new, the locus of accountability is changed in the ACO model—emphasizing accountability at the level of actual care delivery with documentation of quality and cost outcomes. The ACO approach aims to address multiple, frequent, and recurring problems, including lack of financial incentives to improve quality and reduce cost, as well as the negative consequences of a pay-for-volume system—uncoordinated and fragmented care, overutilization of unnecessary tests and treatments, and poor patient experience all manifested as unwarranted geographic variation in practice patterns, clinical outcomes, and health spending. Participants in an ACO are rewarded financially if they can slow the growth of their patients’ healthcare costs while maintaining or improving the quality of care delivered. To succeed in this ACO world, hospitalists must assume greater prudence in the use of healthcare services while improving (or at a minimum, maintaining) patient outcomes, thus excising avoidable waste across the continuum of care.

More than half of ACOs include a hospital.8 However, whether hospital-led ACOs possess an advantage remains to be elucidated. Early reports indicated that physician-led ACOs saved more money.9,10 However, others argue that hospitals11 are better capitalized, have greater capacity for data sharing, and possess economies of scale that allow them to invest in more advanced technology, such as predictive modeling and/or simulation software. Such analytics can identify high-cost patients (ie, multiple comorbidities), super utilizers and populations lacking care, allowing ACOs to implement preventive measures to reduce unnecessary utilization. Recently released CMS MSSP 2016 performance data12 showed that nearly half (45%) of physician-only ACOs earned shared savings, whereas 23% of ACOs that include hospitals earned shared savings. However, among all the ACOs that achieved savings, ACO entities that include hospitals generated the highest amount of shared savings (eg, Advocate, Hackensack Alliance, Cleveland Clinic, and AMITA Health). Notably, hospital-led ACOs tend to have much larger beneficiary populations than physician-led ACOs, which may create a scenario of higher risk but higher potential reward.

HOW HOSPITALISTS CONTRIBUTE VALUE TO ACO SUCCESS

The emphasis on value over volume inherent in the development of ACOs occurs through employing care strategies implemented through changes in policies, and eventual structural and cultural changes. These changes require participating organizations to possess certain key competencies, including the following: 1) leadership that facilitates change; 2) organizational culture of teamwork; 3) collaborative relationships among providers; 4) information technology infrastructure for population management and care coordination; 5) infrastructure for monitoring, managing, and reporting quality; 6) ability to manage financial risk; 7) ability to receive and distribute payments or savings; and 8) resources for patient education and support.2,3,13-16 Table 1 summarizes the broad range of roles that hospitalists can serve in delivering care to ACO populations.17-19

Hospitalists’ active pursuit of nonclinical training and selection for administrative positions demonstrate their proclivity to provide these competencies. In addition to full-time clinician hospitalists, who can directly influence the delivery of high-value care to patients, hospitalists serve many other roles in hospitals and each can contribute differently based on their specialized expertise. Examples include the success of the Society of Hospital Medicine’s Leadership Academy; the acknowledged expertise of hospitalists in quality improvement (QI), informatics, teamwork, patient experience, care coordination and utilization; and advancement of hospitalists to senior leadership positions (eg, CQO, CMO, CEO). Given that nearly a third of healthcare expenditures are for hospital care,20 hospitalists are in a unique position to foster ACO competencies while impacting the quality of care episodes associated with an index hospital stay.

Importantly, hospitalists cannot act as gatekeepers to restrict care. Managed care organizations and health maintenance organizations use of this approach in the 1990s to limit access to services in order to reduce costs led to unacceptable outcomes and numerous malpractice lawsuits. ACOs should aspire to deliver the most cost-effective high-quality care, and their performance should be monitored to ensure that they provide recommended services and timely access. The Medicare ACO contract holds the provider accountable for meeting 34 different quality measures (Supplemental Table 1), and hospitalists can influence outcomes for the majority. Especially through hospital and health system QI initiatives, hospitalists can directly impact and share accountability for measures ranging from care coordination to implementation of evidence-based care (eg, ACE inhibitors and beta blockers for heart failure) to patient and family caregiver experience.

Aligned with Medicare ACO quality measures, 5 high-impact target areas were identified for ACOs21: (1) Prevention and wellness; (2) Chronic conditions/care management; (3) Reduced hospitalizations; (4) Care transitions across the fragmented system; and (5) Multispecialty care coordination of complex patients. One essential element of a successful ACO is the ability to implement evidence-based medical guidelines and/or practices across the continuum of care for selected targeted initiatives. Optimizing care coordination/continuum requires team-based care, and hospitalists already routinely collaborate with nurses, social workers, case managers, pharmacists, and other stakeholders such as dieticians and physical therapists on inpatient care. Hospitalists are also experienced in facilitating communication and improving integration and coordination efficiencies among primary care providers and specialists, and between hospital care and post-acute care, as they coordinate post-hospital care and follow-up. This provides an opportunity to lead health system care coordination efforts, especially for complex and/or high-risk patients.22,23 CMS MSSP 2016 performance data12 showed that ACOs achieving shared savings had a decline in inpatient expenditures and utilization across several facility types (hospital, SNF, rehabilitation, long term). Postacute care management is critical to earning shared savings; SNF and Home Health expenditures fell by 18.3% and 9.7%, respectively, on average. We believe that hospitalists can have more influence over these cost areas by influencing treatment of hospitalized patients in a timely manner, discharge coordination, and selection of appropriate disposition locations. Hospitalists also play an integral role in ensuring the hospital performs well on quality metrics, including 30-day readmissions, hospital acquired conditions, and patient satisfaction. Examples below document the effectiveness of hospitalists in this new ACO era.

Care Transitions/Coordination

Before the Hospital Readmission Reduction Program (HRRP) delineated in the ACA, hospitalists developed Project BOOST (Better Outcomes by Optimizing Care Transitions) to improve hospital discharge care transition. The evidence-based foundation of this project led CMS to list Project BOOST as an example program that can reduce readmissions.24 Through the dissemination and mentored implementation of Project BOOST to over 200 hospitals across the United States,25 hospitalists contributed to the marked reduction in hospital readmission occurring since 2010.26 Although hospital medicine began as a practice specific to the hospital setting, hospitalists’ skills generated growing demand for them in postacute facilities. SNF residents commonly come from hospitals postdischarge and suffer from multiple comorbidities and limitations in activities of daily living. Not surprisingly, SNF residents experience high rates of rehospitalizations.27 Hospitalists can serve as a bridge between hospitals and SNFs and optimize this transition process to yield improved outcomes. Industry experts endorse this approach.28 A recent study demonstrated a significant reduction in readmissions in 1 SNF (32.3% to 16.1%, odds ratio = 0.403, P < .001), by having a hospitalist-led team follow patients discharged from the hospital.29

Chronic Conditions Management/High-Risk Patients

Interest in patients with multiple chronic comorbidities and social issues intensifies as healthcare systems focus limited resources on these high-risk patients to prevent the unnecessary use of costly services.30,31 As health systems assume financial risk for health outcomes and costs of designated patient groups, they undertake efforts to understand the population they serve. Such efforts aim to identify patients with established high utilization patterns (or those at risk for high utilization). This knowledge enables targeted actions to provide access, treatment, and preventive interventions to avoid unneeded emergency and hospital services. Hospitalists commonly care for these patients and are positioned to lead the implementation of patient risk assessment and stratification, develop patient-centered care models across care settings, and act as a liaison with primary care. For frail elderly and seriously ill patients, the integration of hospitalists into palliative care provides several opportunities for improving the quality of care at the end of life.32 As patients and their family caregivers commonly do not address goals of care until faced with a life-threatening condition in the hospital, hospitalists represent ideal primary palliative care physicians to initiate these conversations.33 A hospitalist communicating with a patient and/or their family caregiver about alleviating symptoms and clarifying patients’ preferences for care often yields decreases in ineffective healthcare utilization and better patient outcomes. The hospitalists’ ability to communicate with other providers within the hospital setting also allows them to better coordinate interdisciplinary care and prevent unnecessary and ineffective treatments and procedures.

De-Implementation/Waste Reduction

The largest inefficiencies in healthcare noted in the National Academy of Medicine report, Demanding Value from Our Health Care (2012), are failure to deliver known beneficial therapies or providing unnecessary or nonevidenced based services that do not improve outcomes, but come with associated risk and cost.34 “De-implementation” of unnecessary diagnostic tests or ineffective or even harmful treatments by hospitalists represents a significant opportunity to reduce costs while maintaining or even improving the quality of care. The Society of Hospital Medicine joined the Choosing Wisely® campaign and made 5 recommendations in adult care as an explicit starting point for eliminating waste in the hospital in 2013.35 Since then, hospitalists have participated in multiple successful efforts to address overutilization of care; some published results include the following:

- decreased frequency of unnecessary common labs through a multifaceted hospitalist QI intervention;36

- reduced length of stay and cost by appropriate use of telemetry;37 and

- reduced unnecessary radiology testing by providing physicians with individualized audit and feedback reports.38

CONCLUSION

Hundreds of ACOs now exist across the US, formed by a variety of providers including hospitals, physician groups, and integrated delivery systems. Provider groups range in size from primary care-focused physician groups with a handful of offices to large, multistate integrated delivery systems with dozens of hospitals and hundreds of office locations. Evaluations of ACO outcomes reveal mixed results.9,39-53 Admittedly, assessments attempting to compare the magnitude of savings across ACO models are difficult given the variation in size, variability in specific efforts to influence utilization, and substantial turnover among participating beneficiaries.54 Nonetheless, a newly published Office of Inspector General report55 showed that most Medicare ACOs reduced spending and improved care quality (82% of the individual quality measures) over the first 3 years of the program, and savings increased with duration of an ACO program. The report also noted that considerable time and managerial resources are required to implement changes to improve quality and lower costs. While the political terrain ostensibly supports value-based care and the need to diminish the proportion of our nation’s gross domestic product dedicated to healthcare, health systems are navigating an environment that still largely rewards volume. Hospitalists may be ideal facilitators for this transitional period as they possess the clinical experience caring for complex patients with multiple comorbidities and quality improvement skills to lead efforts in this new ACO era.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

The accountable care organization (ACO) concept, elucidated in 2006 as the development of partnerships between hospitals and physicians to coordinate and deliver efficient care,1 seeks to remove existing barriers to improving value.2 Some advocate this concept as a promising payment model that could successfully realign the current payment system to financially reward improvements in quality and efficiency that bend the cost curve.3,4 Hospitalists fit well with this philosophy. As the fastest growing medical specialty in the history of American medicine, from a couple of thousand hospitalists in the mid-1990s to more than 50,000, the remarkable progression of hospitalists has ostensibly been driven partially by hospitals’ efforts to improve the value equation through enhanced efficiency in inpatient care. Importantly, hospitalists probably provide care for more than half of all hospitalized Medicare beneficiaries and increasingly patients in skilled nursing facilities (ie, SNFists).5 Along with primary care physicians, hospitalists thus represent an essential group of physicians needed to transform care delivery.

RAPID GROWTH AND THE FUTURE OF ACOs

When the Affordable Care Act (ACA) established the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP), ACOs leaped from being an intellectual concept1,2 into a pragmatic health system strategy.3,4 Following Medicare, various private health insurance plans and some state Medicaid programs entered into contracts with groups of healthcare providers (hospitals, physicians, or health systems) to serve as ACOs for their insured enrollees.6 Leavitt Partners’ ACO tracking database showed that the number of ACOs increased from 157 in March of 2012 to 782 in December of 2015.7

Until recently, the federal government’s commitment to having 50% of total Medicare spending via value-based payment models by 2018, coupled with endorsement from state Medicaid programs and commercial insurers, demonstrated strong support for continuation of ACOs. Unexpectedly on August 15, 2017, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) outlined a plan in its proposed rulemaking to cancel the Episode Payment Models and the Cardiac Rehabilitation incentive payment model, which were scheduled to commence on January 1, 2018. CMS also plans to scale back the mandatory Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement (CCJR) bundled payment model from 67 selected geographic areas to 34. Although this proposed rulemaking created some equipoise in the healthcare industry regarding the future of value-based reimbursement approaches, cost containment and improved efficiency remain as major focuses of the federal government’s healthcare effort. Notably, CMS offers providers that are newly excluded from the CCJR model the opportunity to voluntarily participate in the program and is expected to increase opportunities for providers to participate in voluntary rather than large-scale mandatory episode payment model initiatives. In 2018, the agency also plans to develop new voluntary bundled payment models that will meet criteria to be considered an advanced alternative payment model for Quality Payment Program purposes.

Importantly, the value-based reimbursement movement was well underway before ACA legislation. Through ACA health reform, value-based reimbursement efforts were expanded through ACOs, bundled payments, value-based purchasing, the CMS Innovation Center and other initiatives. With health systems having an overflowing plate of activities, a wait-and-see attitude might seem reasonable at first. However, being unprepared for the inevitable shift to value-based reimbursement and reduced fee-for-service revenue places an organization at risk. A successful ACO requires system-level transformation, especially cultural and structural changes to achieve clinical integration. Being embedded in health system delivery, hospitalists can help shape a team-oriented culture and foster success in value-based payment models. This requires hospitalists to take a more active role in assessing and striking a balance between high-quality, cost-efficient care and financial risk inherent in ACO models.

WHAT HOSPITALISTS NEED TO KNOW ABOUT ACOs

The key to hospitalists fulfilling their value creation potential and becoming enablers for ACO success lies in developing a thorough understanding of the aspects of an ACO that promote efficient and effective care, while accounting for financial factors. Fundamentally, the ACO concept combines provider payment and delivery system reforms. Specifically, the definition of an ACO contains 3 factors: (1) a local healthcare organization (eg, hospital or multispecialty group of physicians) with a related set of providers that (2) can be held accountable for the cost and quality of care delivered to (3) a defined population. While the notion of accountability is not new, the locus of accountability is changed in the ACO model—emphasizing accountability at the level of actual care delivery with documentation of quality and cost outcomes. The ACO approach aims to address multiple, frequent, and recurring problems, including lack of financial incentives to improve quality and reduce cost, as well as the negative consequences of a pay-for-volume system—uncoordinated and fragmented care, overutilization of unnecessary tests and treatments, and poor patient experience all manifested as unwarranted geographic variation in practice patterns, clinical outcomes, and health spending. Participants in an ACO are rewarded financially if they can slow the growth of their patients’ healthcare costs while maintaining or improving the quality of care delivered. To succeed in this ACO world, hospitalists must assume greater prudence in the use of healthcare services while improving (or at a minimum, maintaining) patient outcomes, thus excising avoidable waste across the continuum of care.

More than half of ACOs include a hospital.8 However, whether hospital-led ACOs possess an advantage remains to be elucidated. Early reports indicated that physician-led ACOs saved more money.9,10 However, others argue that hospitals11 are better capitalized, have greater capacity for data sharing, and possess economies of scale that allow them to invest in more advanced technology, such as predictive modeling and/or simulation software. Such analytics can identify high-cost patients (ie, multiple comorbidities), super utilizers and populations lacking care, allowing ACOs to implement preventive measures to reduce unnecessary utilization. Recently released CMS MSSP 2016 performance data12 showed that nearly half (45%) of physician-only ACOs earned shared savings, whereas 23% of ACOs that include hospitals earned shared savings. However, among all the ACOs that achieved savings, ACO entities that include hospitals generated the highest amount of shared savings (eg, Advocate, Hackensack Alliance, Cleveland Clinic, and AMITA Health). Notably, hospital-led ACOs tend to have much larger beneficiary populations than physician-led ACOs, which may create a scenario of higher risk but higher potential reward.

HOW HOSPITALISTS CONTRIBUTE VALUE TO ACO SUCCESS

The emphasis on value over volume inherent in the development of ACOs occurs through employing care strategies implemented through changes in policies, and eventual structural and cultural changes. These changes require participating organizations to possess certain key competencies, including the following: 1) leadership that facilitates change; 2) organizational culture of teamwork; 3) collaborative relationships among providers; 4) information technology infrastructure for population management and care coordination; 5) infrastructure for monitoring, managing, and reporting quality; 6) ability to manage financial risk; 7) ability to receive and distribute payments or savings; and 8) resources for patient education and support.2,3,13-16 Table 1 summarizes the broad range of roles that hospitalists can serve in delivering care to ACO populations.17-19

Hospitalists’ active pursuit of nonclinical training and selection for administrative positions demonstrate their proclivity to provide these competencies. In addition to full-time clinician hospitalists, who can directly influence the delivery of high-value care to patients, hospitalists serve many other roles in hospitals and each can contribute differently based on their specialized expertise. Examples include the success of the Society of Hospital Medicine’s Leadership Academy; the acknowledged expertise of hospitalists in quality improvement (QI), informatics, teamwork, patient experience, care coordination and utilization; and advancement of hospitalists to senior leadership positions (eg, CQO, CMO, CEO). Given that nearly a third of healthcare expenditures are for hospital care,20 hospitalists are in a unique position to foster ACO competencies while impacting the quality of care episodes associated with an index hospital stay.

Importantly, hospitalists cannot act as gatekeepers to restrict care. Managed care organizations and health maintenance organizations use of this approach in the 1990s to limit access to services in order to reduce costs led to unacceptable outcomes and numerous malpractice lawsuits. ACOs should aspire to deliver the most cost-effective high-quality care, and their performance should be monitored to ensure that they provide recommended services and timely access. The Medicare ACO contract holds the provider accountable for meeting 34 different quality measures (Supplemental Table 1), and hospitalists can influence outcomes for the majority. Especially through hospital and health system QI initiatives, hospitalists can directly impact and share accountability for measures ranging from care coordination to implementation of evidence-based care (eg, ACE inhibitors and beta blockers for heart failure) to patient and family caregiver experience.

Aligned with Medicare ACO quality measures, 5 high-impact target areas were identified for ACOs21: (1) Prevention and wellness; (2) Chronic conditions/care management; (3) Reduced hospitalizations; (4) Care transitions across the fragmented system; and (5) Multispecialty care coordination of complex patients. One essential element of a successful ACO is the ability to implement evidence-based medical guidelines and/or practices across the continuum of care for selected targeted initiatives. Optimizing care coordination/continuum requires team-based care, and hospitalists already routinely collaborate with nurses, social workers, case managers, pharmacists, and other stakeholders such as dieticians and physical therapists on inpatient care. Hospitalists are also experienced in facilitating communication and improving integration and coordination efficiencies among primary care providers and specialists, and between hospital care and post-acute care, as they coordinate post-hospital care and follow-up. This provides an opportunity to lead health system care coordination efforts, especially for complex and/or high-risk patients.22,23 CMS MSSP 2016 performance data12 showed that ACOs achieving shared savings had a decline in inpatient expenditures and utilization across several facility types (hospital, SNF, rehabilitation, long term). Postacute care management is critical to earning shared savings; SNF and Home Health expenditures fell by 18.3% and 9.7%, respectively, on average. We believe that hospitalists can have more influence over these cost areas by influencing treatment of hospitalized patients in a timely manner, discharge coordination, and selection of appropriate disposition locations. Hospitalists also play an integral role in ensuring the hospital performs well on quality metrics, including 30-day readmissions, hospital acquired conditions, and patient satisfaction. Examples below document the effectiveness of hospitalists in this new ACO era.

Care Transitions/Coordination

Before the Hospital Readmission Reduction Program (HRRP) delineated in the ACA, hospitalists developed Project BOOST (Better Outcomes by Optimizing Care Transitions) to improve hospital discharge care transition. The evidence-based foundation of this project led CMS to list Project BOOST as an example program that can reduce readmissions.24 Through the dissemination and mentored implementation of Project BOOST to over 200 hospitals across the United States,25 hospitalists contributed to the marked reduction in hospital readmission occurring since 2010.26 Although hospital medicine began as a practice specific to the hospital setting, hospitalists’ skills generated growing demand for them in postacute facilities. SNF residents commonly come from hospitals postdischarge and suffer from multiple comorbidities and limitations in activities of daily living. Not surprisingly, SNF residents experience high rates of rehospitalizations.27 Hospitalists can serve as a bridge between hospitals and SNFs and optimize this transition process to yield improved outcomes. Industry experts endorse this approach.28 A recent study demonstrated a significant reduction in readmissions in 1 SNF (32.3% to 16.1%, odds ratio = 0.403, P < .001), by having a hospitalist-led team follow patients discharged from the hospital.29

Chronic Conditions Management/High-Risk Patients

Interest in patients with multiple chronic comorbidities and social issues intensifies as healthcare systems focus limited resources on these high-risk patients to prevent the unnecessary use of costly services.30,31 As health systems assume financial risk for health outcomes and costs of designated patient groups, they undertake efforts to understand the population they serve. Such efforts aim to identify patients with established high utilization patterns (or those at risk for high utilization). This knowledge enables targeted actions to provide access, treatment, and preventive interventions to avoid unneeded emergency and hospital services. Hospitalists commonly care for these patients and are positioned to lead the implementation of patient risk assessment and stratification, develop patient-centered care models across care settings, and act as a liaison with primary care. For frail elderly and seriously ill patients, the integration of hospitalists into palliative care provides several opportunities for improving the quality of care at the end of life.32 As patients and their family caregivers commonly do not address goals of care until faced with a life-threatening condition in the hospital, hospitalists represent ideal primary palliative care physicians to initiate these conversations.33 A hospitalist communicating with a patient and/or their family caregiver about alleviating symptoms and clarifying patients’ preferences for care often yields decreases in ineffective healthcare utilization and better patient outcomes. The hospitalists’ ability to communicate with other providers within the hospital setting also allows them to better coordinate interdisciplinary care and prevent unnecessary and ineffective treatments and procedures.

De-Implementation/Waste Reduction

The largest inefficiencies in healthcare noted in the National Academy of Medicine report, Demanding Value from Our Health Care (2012), are failure to deliver known beneficial therapies or providing unnecessary or nonevidenced based services that do not improve outcomes, but come with associated risk and cost.34 “De-implementation” of unnecessary diagnostic tests or ineffective or even harmful treatments by hospitalists represents a significant opportunity to reduce costs while maintaining or even improving the quality of care. The Society of Hospital Medicine joined the Choosing Wisely® campaign and made 5 recommendations in adult care as an explicit starting point for eliminating waste in the hospital in 2013.35 Since then, hospitalists have participated in multiple successful efforts to address overutilization of care; some published results include the following:

- decreased frequency of unnecessary common labs through a multifaceted hospitalist QI intervention;36

- reduced length of stay and cost by appropriate use of telemetry;37 and

- reduced unnecessary radiology testing by providing physicians with individualized audit and feedback reports.38

CONCLUSION

Hundreds of ACOs now exist across the US, formed by a variety of providers including hospitals, physician groups, and integrated delivery systems. Provider groups range in size from primary care-focused physician groups with a handful of offices to large, multistate integrated delivery systems with dozens of hospitals and hundreds of office locations. Evaluations of ACO outcomes reveal mixed results.9,39-53 Admittedly, assessments attempting to compare the magnitude of savings across ACO models are difficult given the variation in size, variability in specific efforts to influence utilization, and substantial turnover among participating beneficiaries.54 Nonetheless, a newly published Office of Inspector General report55 showed that most Medicare ACOs reduced spending and improved care quality (82% of the individual quality measures) over the first 3 years of the program, and savings increased with duration of an ACO program. The report also noted that considerable time and managerial resources are required to implement changes to improve quality and lower costs. While the political terrain ostensibly supports value-based care and the need to diminish the proportion of our nation’s gross domestic product dedicated to healthcare, health systems are navigating an environment that still largely rewards volume. Hospitalists may be ideal facilitators for this transitional period as they possess the clinical experience caring for complex patients with multiple comorbidities and quality improvement skills to lead efforts in this new ACO era.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

1. Fisher ES, Staiger DO, Bynum JP, Gottlieb DJ. Creating accountable care organizations: the extended hospital medical staff. Health Aff(Project Hope). 2007;26(1):w44-w57. PubMed

2. Fisher ES, McClellan MB, Bertko J, et al. Fostering accountable health care: moving forward in medicare. Health Aff(Project Hope). 2009;28(2):w219-w231. PubMed

3. McClellan M, McKethan AN, Lewis JL, Roski J, Fisher ES. A national strategy to put accountable care into practice. Health Aff(Project Hope). 2010;29(5):982-990. PubMed

4. Berwick DM. Making good on ACOs’ promise--the final rule for the Medicare shared savings program. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(19):1753-1756. PubMed

5. Kuo YF, Sharma G, Freeman JL, Goodwin JS. Growth in the care of older patients by hospitalists in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(11):1102-1112. PubMed

6. Kennedy K. Health Care Providers Embracing Cost-saving Groups. USA Today, July 24, 2011.

7. Leavitt Partners. Available at http://leavittpartners.com, April 2016.

8. Colla CH, Lewis VA, Tierney E, Muhlestein DB. Hospitals Participating In ACOs Tend To Be Large And Urban, Allowing Access To Capital And Data. Health Aff(Millwood). 2016;35(3):431-439. PubMed

9. McWilliams JM, Hatfield LA, Chernew ME, Landon BE, Schwartz AL. Early Performance of Accountable Care Organizations in Medicare. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(24):2357-2366. PubMed

10. Muhlestein D, Saunders R, McClellan M. Medicare Accountable Care Organization Results For 2015: The Journey To Better Quality And Lower Costs Continues. In. Health Affairs Blog. Bethesda, MD 2016.

11. Chernew ME. New Health Care Symposium: Building An ACO---What Services Do You Need And How Are Physicians Impacted? In Health Affairs Blog. Bethesda, MD 2016.

12. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Performance Year 2016 Quality Performance and Financial Reconciliation Results for ACOs with 2012-2016 Start Dates. Available at https://strategichealthcare.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/CMS-Slides-on-ACOs.pdf. 2017.

13. Shortell SM, Casalino LP. Implementing qualifications criteria and technical assistance for accountable care organizations. JAMA. 2010;303(17):1747-1748. PubMed

14. Shortell SM, Casalino LP, Fisher ES. How the center for Medicare and Medicaid innovation should test accountable care organizations. Health Aff (Project Hope). 2010;29(7):1293-1298. PubMed

15. Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Accountable Care Organizations Payment Systems October 2015. Available at http://www.medpac.gov/documents/payment-basics/accountable-care-organization-payment-systems-15.pdf?sfvrsn=0.

16. American Hospital Association. 2010 Committee on Research. AHA Research Synthesis Report: Accountable Care Organization.

17. D’Aunno T, Broffman L, Sparer M, Kumar SR. Factors That Distinguish High-Performing Accountable Care Organizations in the Medicare Shared Savings Program. Health Serv. Res. 2016. PubMed

18. Peiris D, Phipps-Taylor MC, Stachowski CA, et al. ACOs Holding Commercial Contracts Are Larger And More Efficient Than Noncommercial ACOs. Health Aff (Project Hope). 2016;35(10):1849-1856. PubMed

19. Ouayogode MH, Colla CH, Lewis VA. Determinants of success in Shared Savings Programs: An analysis of ACO and market characteristics. Healthcare (Amsterdam, Netherlands). 2017;5(1-2):53-61. PubMed

20. National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2016: With Chartbook on Long-term Trends in Health. In: Hyattsville, MD.2017. PubMed

21. Gbemudu JN. Larson BK, Van Citters AD, Kreindler SA, Nelson EC, Shortell SM, Fisher ES. Norton Healthcare: A Strong Payer–Provider Partnership for the Journey to Accountable Care. January 2012. Available at http://www.commonwealthfund.org/~/media/files/publications/case-study/2012/jan/1574_gbemudu_norton_case-study_01_12_2012.pdf.

22. O’Leary KJ, Haviley C, Slade ME, Shah HM, Lee J, Williams MV. Improving teamwork: impact of structured interdisciplinary rounds on a hospitalist unit. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(2):88-93. PubMed

23. Hansen LO, Greenwald JL, Budnitz T, et al. Project BOOST: effectiveness of a multihospital effort to reduce rehospitalization. J. Hosp. Med.. 2013;8(8):421-427. PubMed

24. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Solicitation for Applications: Community-based Care Transitions Program. Available at https://innovation.cms.gov/Files/Migrated-Medicare-Demonstration-x/CCTP-Solicitation.pdf. September 7, 2017.

25. Li J, Hinami K, Hansen LO, Maynard G, Budnitz T, Williams MV. The physician mentored implementation model: a promising quality improvement framework for health care change. Acad Med. 2015;90(3):303-310. PubMed

26. Williams MV, Li J, Hansen LO, et al. Project BOOST implementation: lessons learned. South Med J. 2014;107(7):455-465. PubMed

27. Ouslander JG, Lamb G, Perloe M, et al. Potentially avoidable hospitalizations of nursing home residents: frequency, causes, and costs: [see editorial comments by Drs. Jean F. Wyman and William R. Hazzard, pp 760-761]. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(4):627-635. PubMed

28. Pittman D. SNFs: New Turf for Hospitalists? 2013. Available at https://www.medpagetoday.com/hospitalbasedmedicine/hospitalists/39401.

29. Petigara S, Krishnamurthy M, Livert D. Necessity is the mother of invention: an innovative hospitalist-resident initiative for improving quality and reducing readmissions from skilled nursing facilities. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2017;7(2):66-69. PubMed

30. Silow-Carroll S, Edwards J. Early Adopters of the Accountable Care Model: A Field Report on Improvements in Health Care Delivery. New York, NY: The Commonwealth Fund;March 2013.

31. Hasselman D. Super-Utilizer Summit: Common Themes from Innovative Complex Care Management Programs. Hamilton, NJ: Center for Health Care Strategies;October 2013.

32. Wald HL, Glasheen JJ, Guerrasio J, Youngwerth JM, Cumbler EU. Evaluation of a hospitalist-run acute care for the elderly service. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(6):313-321. PubMed

33. Quill TE, Abernethy AP. Generalist plus specialist palliative care--creating a more sustainable model. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(13):1173-1175. PubMed

34. O’Kane M, Buto K, Alteras T, et. al. Demanding Value from Our Health Care: Motivating Patient Action to Reduce Waste in Health Care. Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. July 2012. https://nam.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/VSRT-DemandingValue.pdf. Accessed Accessed June 18, 2017.

35. Bulger J, Nickel W, Messler J, et al. Choosing wisely in adult hospital medicine: five opportunities for improved healthcare value. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(9):486-492. PubMed

36. Corson AH, Fan VS, White T, et al. A multifaceted hospitalist quality improvement intervention: Decreased frequency of common labs. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(6):390-395. PubMed

37. Svec D, Ahuja N, Evans KH, et al. Hospitalist intervention for appropriate use of telemetry reduces length of stay and cost. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(9):627-632. PubMed

38. Neeman N, Quinn K, Soni K, Mourad M, Sehgal NL. Reducing radiology use on an inpatient medical service: choosing wisely. JAMA Intern Med. 2012;172(20):1606-1608. PubMed

39. Abrams M, Nuzum R, Zezza M, Ryan J, Kiszla J, Guterman S. The Affordable Care Act’s Payment and Delivery System Reforms: A Progress Report at Five Years. Bipartisan Policy Center, May 2015. Available at http://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2015/may/aca-payment-and-delivery-system-reforms-at-5-years.

40. Kocot SL, White R, Katikaneni P, McClellan MB. A More Complete Picture of Pioneer ACO Results. The Brookings Institution, October 13, 2014. Available at http://www.brookings.edu/blogs/up-front/posts/2014/10/09-pioneer-aco-results-mcclellan/#recent_rr/

41. Blumenthal D, Abrams M, Nuzum R. The Affordable Care Act at 5 Years. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(25):2451-2458. PubMed

42. Colla CH, Lewis VA, Kao LS, O’Malley AJ, Chang CH, Fisher ES. Association Between Medicare Accountable Care Organization Implementation and Spending Among Clinically Vulnerable Beneficiaries. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(8):1167-1175. PubMed

43. Epstein AM, Jha AK, Orav EJ, et al. Analysis of early accountable care organizations defines patient, structural, cost, and quality-of-care characteristics. Health Aff (Project Hope). 2014;33(1):95-102. PubMed

44. Fullerton CA, Henke RM, Crable E, Hohlbauch A, Cummings N. The Impact Of Medicare ACOs On Improving Integration And Coordination Of Physical And Behavioral Health Care. Health Aff (Project Hope). 2016;35(7):1257-1265. PubMed

45. Herrel LA, Norton EC, Hawken SR, Ye Z, Hollenbeck BK, Miller DC. Early impact of Medicare accountable care organizations on cancer surgery outcomes. Cancer. 2016;122(17):2739-2746. PubMed

46. McConnell KJ, Renfro S, Chan BK, et al. Early Performance in Medicaid Accountable Care Organizations: A Comparison of Oregon and Colorado. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(4):538-545. PubMed

47. Nyweide DJ, Lee W, Cuerdon TT, et al. Association of Pioneer Accountable Care Organizations vs traditional Medicare fee for service with spending, utilization, and patient experience. JAMA. 2015;313(21):2152-2161. PubMed

48. Rajkumar R, Press MJ, Conway PH. The CMS Innovation Center--a five-year self-assessment. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(21):1981-1983. PubMed

49. Rose S, Zaslavsky AM, McWilliams JM. Variation In Accountable Care Organization Spending And Sensitivity To Risk Adjustment: Implications For Benchmarking. Health affairs (Project Hope). 2016;35(3):440-448. PubMed

50. Shortell SM, Poon BY, Ramsay PP, et al. A Multilevel Analysis of Patient Engagement and Patient-Reported Outcomes in Primary Care Practices of Accountable Care Organizations. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(6):640-647. PubMed

51. Winblad U, Mor V, McHugh JP, Rahman M. ACO-Affiliated Hospitals Reduced Rehospitalizations From Skilled Nursing Facilities Faster Than Other Hospitals. Health Aff (Project Hope). 2017;36(1):67-73. PubMed

52. Zhang Y, Caines KJ, Powers CA. Evaluating the Effects of Pioneer Accountable Care Organizations on Medicare Part D Drug Spending and Utilization. Med Care. 2017;55(5):470-475. PubMed

53. Muhlestein D. Medicare ACOs: Mixed Initial Results and Cautious Optimism. Health Affairs Blog, February 4, 2014. Available at http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2014/02/04/medicare-acos-mixed-initial-results-and-cautious-optimism/.

54. Hsu J, Price M, Vogeli C, et al. Bending The Spending Curve By Altering Care Delivery Patterns: The Role Of Care Management Within A Pioneer ACO. Health Aff (Project Hope). 2017;36(5):876-884. PubMed

55. Medicare Shared Savings Program Accountable Care Organizations Have Shown Potential For Reducing Spending And Improving Quality. Office of Inspector General;August 2017.

1. Fisher ES, Staiger DO, Bynum JP, Gottlieb DJ. Creating accountable care organizations: the extended hospital medical staff. Health Aff(Project Hope). 2007;26(1):w44-w57. PubMed

2. Fisher ES, McClellan MB, Bertko J, et al. Fostering accountable health care: moving forward in medicare. Health Aff(Project Hope). 2009;28(2):w219-w231. PubMed

3. McClellan M, McKethan AN, Lewis JL, Roski J, Fisher ES. A national strategy to put accountable care into practice. Health Aff(Project Hope). 2010;29(5):982-990. PubMed

4. Berwick DM. Making good on ACOs’ promise--the final rule for the Medicare shared savings program. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(19):1753-1756. PubMed

5. Kuo YF, Sharma G, Freeman JL, Goodwin JS. Growth in the care of older patients by hospitalists in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(11):1102-1112. PubMed

6. Kennedy K. Health Care Providers Embracing Cost-saving Groups. USA Today, July 24, 2011.

7. Leavitt Partners. Available at http://leavittpartners.com, April 2016.

8. Colla CH, Lewis VA, Tierney E, Muhlestein DB. Hospitals Participating In ACOs Tend To Be Large And Urban, Allowing Access To Capital And Data. Health Aff(Millwood). 2016;35(3):431-439. PubMed

9. McWilliams JM, Hatfield LA, Chernew ME, Landon BE, Schwartz AL. Early Performance of Accountable Care Organizations in Medicare. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(24):2357-2366. PubMed

10. Muhlestein D, Saunders R, McClellan M. Medicare Accountable Care Organization Results For 2015: The Journey To Better Quality And Lower Costs Continues. In. Health Affairs Blog. Bethesda, MD 2016.

11. Chernew ME. New Health Care Symposium: Building An ACO---What Services Do You Need And How Are Physicians Impacted? In Health Affairs Blog. Bethesda, MD 2016.

12. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Performance Year 2016 Quality Performance and Financial Reconciliation Results for ACOs with 2012-2016 Start Dates. Available at https://strategichealthcare.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/CMS-Slides-on-ACOs.pdf. 2017.

13. Shortell SM, Casalino LP. Implementing qualifications criteria and technical assistance for accountable care organizations. JAMA. 2010;303(17):1747-1748. PubMed

14. Shortell SM, Casalino LP, Fisher ES. How the center for Medicare and Medicaid innovation should test accountable care organizations. Health Aff (Project Hope). 2010;29(7):1293-1298. PubMed

15. Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Accountable Care Organizations Payment Systems October 2015. Available at http://www.medpac.gov/documents/payment-basics/accountable-care-organization-payment-systems-15.pdf?sfvrsn=0.

16. American Hospital Association. 2010 Committee on Research. AHA Research Synthesis Report: Accountable Care Organization.

17. D’Aunno T, Broffman L, Sparer M, Kumar SR. Factors That Distinguish High-Performing Accountable Care Organizations in the Medicare Shared Savings Program. Health Serv. Res. 2016. PubMed

18. Peiris D, Phipps-Taylor MC, Stachowski CA, et al. ACOs Holding Commercial Contracts Are Larger And More Efficient Than Noncommercial ACOs. Health Aff (Project Hope). 2016;35(10):1849-1856. PubMed

19. Ouayogode MH, Colla CH, Lewis VA. Determinants of success in Shared Savings Programs: An analysis of ACO and market characteristics. Healthcare (Amsterdam, Netherlands). 2017;5(1-2):53-61. PubMed

20. National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2016: With Chartbook on Long-term Trends in Health. In: Hyattsville, MD.2017. PubMed

21. Gbemudu JN. Larson BK, Van Citters AD, Kreindler SA, Nelson EC, Shortell SM, Fisher ES. Norton Healthcare: A Strong Payer–Provider Partnership for the Journey to Accountable Care. January 2012. Available at http://www.commonwealthfund.org/~/media/files/publications/case-study/2012/jan/1574_gbemudu_norton_case-study_01_12_2012.pdf.