User login

Discharge Summary Quality

Hospitalized patients are often cared for by physicians who do not follow them in the community, creating a discontinuity of care that must be bridged through communication. This communication between inpatient and outpatient physicians occurs, in part via a discharge summary, which is intended to summarize events during hospitalization and prepare the outpatient physician to resume care of the patient. Yet, this form of communication has long been problematic.[1, 2, 3] In a 1960 study, only 30% of discharge letters were received by the primary care physician within 48 hours of discharge.[1]

More recent studies have shown little improvement. Direct communication between hospital and outpatient physicians is rare, and discharge summaries are still largely unavailable at the time of follow‐up.[4] In 1 study, primary care physicians were unaware of 62% of laboratory tests or study results that were pending on discharge,[5] in part because this information is missing from most discharge summaries.[6] Deficits such as these persist despite the fact that the rate of postdischarge completion of recommended tests, referrals, or procedures is significantly increased when the recommendation is included in the discharge summary.[7]

Regulatory mandates for discharge summaries from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services[8] and from The Joint Commission[9] appear to be generally met[10, 11]; however, these mandates have no requirements for timeliness stricter than 30 days, do not require that summaries be transmitted to outpatient physicians, and do not require several content elements that might be useful to outside physicians such as condition of the patient at discharge, cognitive and functional status, goals of care, or pending studies. Expert opinion guidelines have more comprehensive recommendations,[12, 13] but it is uncertain how widely they are followed.

The existence of a discharge summary does not necessarily mean it serves a patient well in the transitional period.[11, 14, 15] Discharge summaries are a complex intervention, and we do not yet understand the best ways discharge summaries may fulfill needs specific to transitional care. Furthermore, it is uncertain what factors improve aspects of discharge summary quality as defined by timeliness, transmission, and content.[6, 16]

The goal of the DIagnosing Systemic failures, Complexities and HARm in GEriatric discharges study (DISCHARGE) was to comprehensively assess the discharge process for older patients discharged to the community. In this article we examine discharge summaries of patients enrolled in the study to determine the timeliness, transmission to outside physicians, and content of the summaries. We further examine the effect of provider training level and timeliness of dictation on discharge summary quality.

METHODS

Study Cohort

The DISCHARGE study was a prospective, observational cohort study of patients 65 years or older discharged to home from YaleNew Haven Hospital (YNHH) who were admitted with acute coronary syndrome (ACS), community‐acquired pneumonia, or heart failure (HF). Patients were screened by physicians for eligibility within 24 hours of admission using specialty society guidelines[17, 18, 19, 20] and were enrolled by telephone within 1 week of discharge. Additional inclusion criteria included speaking English or Spanish, and ability of the patient or caregiver to participate in a telephone interview. Patients enrolled in hospice were excluded, as were patients who failed the Mini‐Cog mental status screen (3‐item recall and a clock draw)[21] while in the hospital or appeared confused or delirious during the telephone interview. Caregivers of cognitively impaired patients were eligible for enrollment instead if the patient provided permission.

Study Setting

YNHH is a 966‐bed urban tertiary care hospital with statistically lower than the national average mortality for acute myocardial infarction, HF, and pneumonia but statistically higher than the national average for 30‐day readmission rates for HF and pneumonia at the time this study was conducted. Advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs) working under the supervision of private or university cardiologists provided care for cardiology service patients. Housestaff under the supervision of university or hospitalist attending physicians, or physician assistants or APRNs under the supervision of hospitalist attending physicians provided care for patients on medical services. Discharge summaries were typically dictated by APRNs for cardiology patients, by 2nd‐ or 3rd‐year residents for housestaff patients, and by hospitalists for hospitalist patients. A dictation guideline was provided to housestaff and hospitalists (see Supporting Information, Appendix 1, in the online version of this article); this guideline suggested including basic demographic information, disposition and diagnoses, the admission history and physical, hospital course, discharge medications, and follow‐up appointments. Additionally, housestaff received a lecture about discharge summaries at the start of their 2nd year. Discharge instructions including medications and follow‐up appointment information were automatically appended to the discharge summaries. Summaries were sent by the medical records department only to physicians in the system who were listed by the dictating physician as needing to receive a copy of the summary; no summary was automatically sent (ie, to the primary care physician) if not requested by the dictating physician.

Data Collection

Experienced registered nurses trained in chart abstraction conducted explicit reviews of medical charts using a standardized review tool. The tool included 24 questions about the discharge summary applicable to all 3 conditions, with 7 additional questions for patients with HF and 1 additional question for patients with ACS. These questions included the 6 elements required by The Joint Commission for all discharge summaries (reason for hospitalization, significant findings, procedures and treatment provided, patient's discharge condition, patient and family instructions, and attending physician's signature)[9] as well as the 7 elements (principal diagnosis and problem list, medication list, transferring physician name and contact information, cognitive status of the patient, test results, and pending test results) recommended by the Transitions of Care Consensus Conference (TOCCC), a recent consensus statement produced by 6 major medical societies.[13] Each content element is shown in (see Supporting Information, Appendix 2, in the online version of this article), which also indicates the elements included in the 2 guidelines.

Main Measures

We assessed quality in 3 main domains: timeliness, transmission, and content. We defined timeliness as days between discharge date and dictation date (not final signature date, which may occur later), and measured both median timeliness and proportion of discharge summaries completed on the day of discharge. We defined transmission as successful fax or mail of the discharge summary to an outside physician as reported by the medical records department, and measured the proportion of discharge summaries sent to any outside physician as well as the median number of physicians per discharge summary who were scheduled to follow‐up with the patient postdischarge but who did not receive a copy of the summary. We defined 21 individual content items and assessed the frequency of each individual content item. We also measured compliance with The Joint Commission mandates and TOCCC recommendations, which included several of the individual content items.

To measure compliance with The Joint Commission requirements, we created a composite score in which 1 point was provided for the presence of each of the 6 required elements (maximum score=6). Every discharge summary received 1 point for attending physician signature, because all discharge summaries were electronically signed. Discharge instructions to family/patients were automatically appended to every discharge summary; however, we gave credit for patient and family instructions only to those that included any information about signs and symptoms to monitor for at home. We defined discharge condition as any information about functional status, cognitive status, physical exam, or laboratory findings at discharge.

To measure compliance with specialty society recommendations for discharge summaries, we created a composite score in which 1 point was provided for the presence of each of the 7 recommended elements (maximum score=7). Every discharge summary received 1 point for discharge medications, because these are automatically appended.

We obtained data on age, race, gender, and length of stay from hospital administrative databases. The study was approved by the Yale Human Investigation Committee, and verbal informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Statistical Analysis

Characteristics of the sample are described with counts and percentages or means and standard deviations. Medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) or counts and percentages were calculated for summary measures of timeliness, transmission, and content. We assessed differences in quality measures between APRNs, housestaff, and hospitalists using 2 tests. We conducted multivariable logistic regression analyses for timeliness and for transmission to any outside physician. All discharge summaries included at least 4 of The Joint Commission elements; consequently, we coded this content outcome as an ordinal variable with 3 levels indicating inclusion of 4, 5, or 6 of The Joint Commission elements. We coded the TOCCC content outcome as a 3‐level variable indicating <4, 4, or >4 elements satisfied. Accordingly, proportional odds models were used, in which the reported odds ratios (ORs) can be interpreted as the average effect of the explanatory variable on the odds of having more recommendations, for any dichotomization of the outcome. Residual analysis and goodness‐of‐fit statistics were used to assess model fit; the proportional odds assumption was tested. Statistical analyses were conducted with SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). P values <0.05 were interpreted as statistically significant for 2‐sided tests.

RESULTS

Enrollment and Study Sample

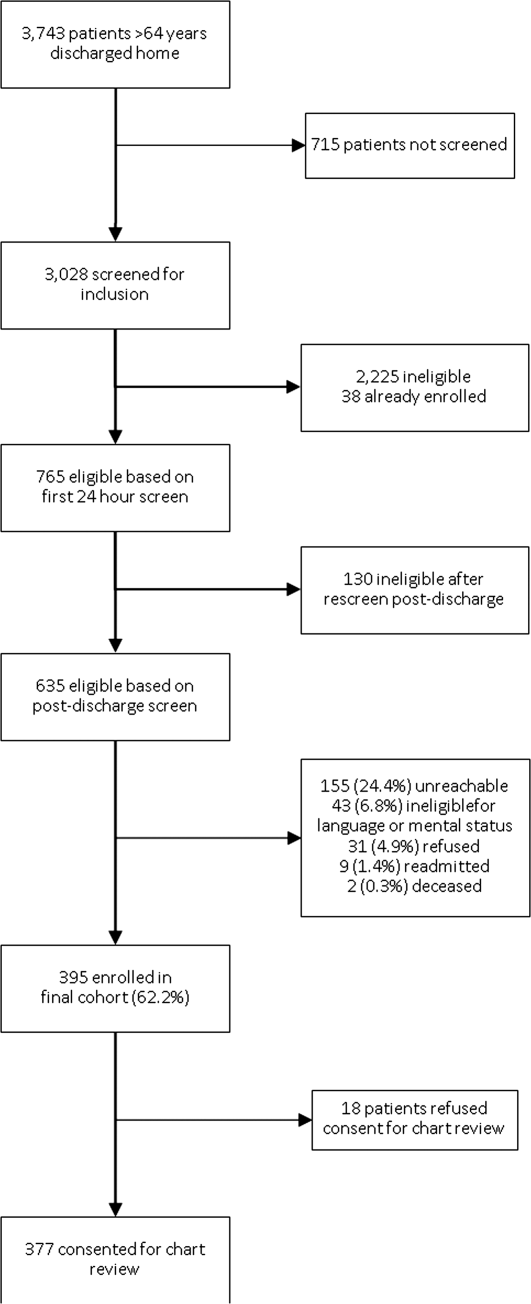

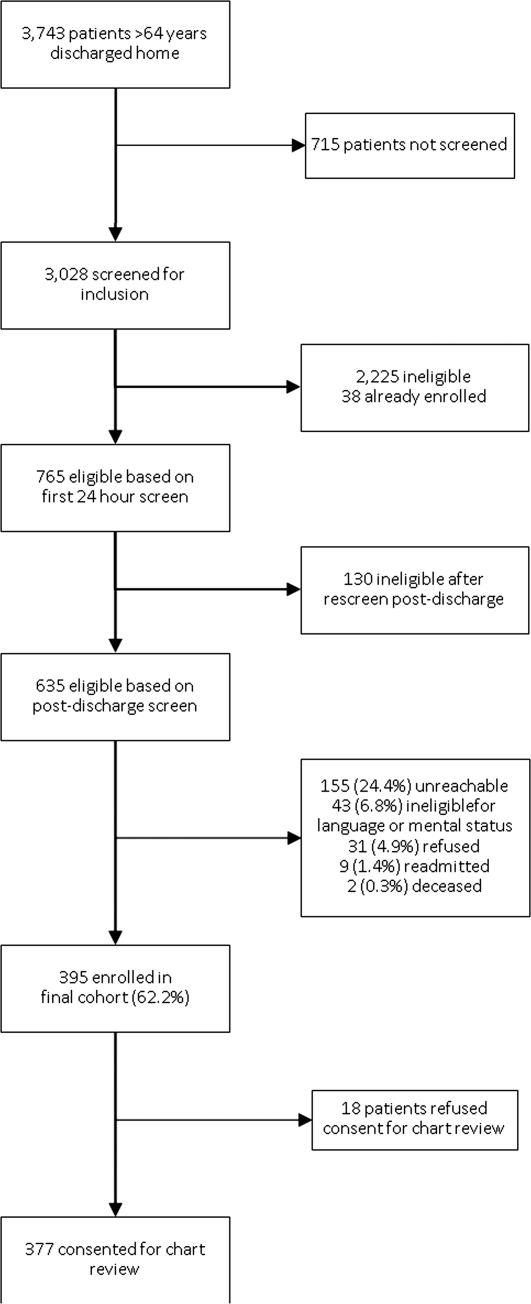

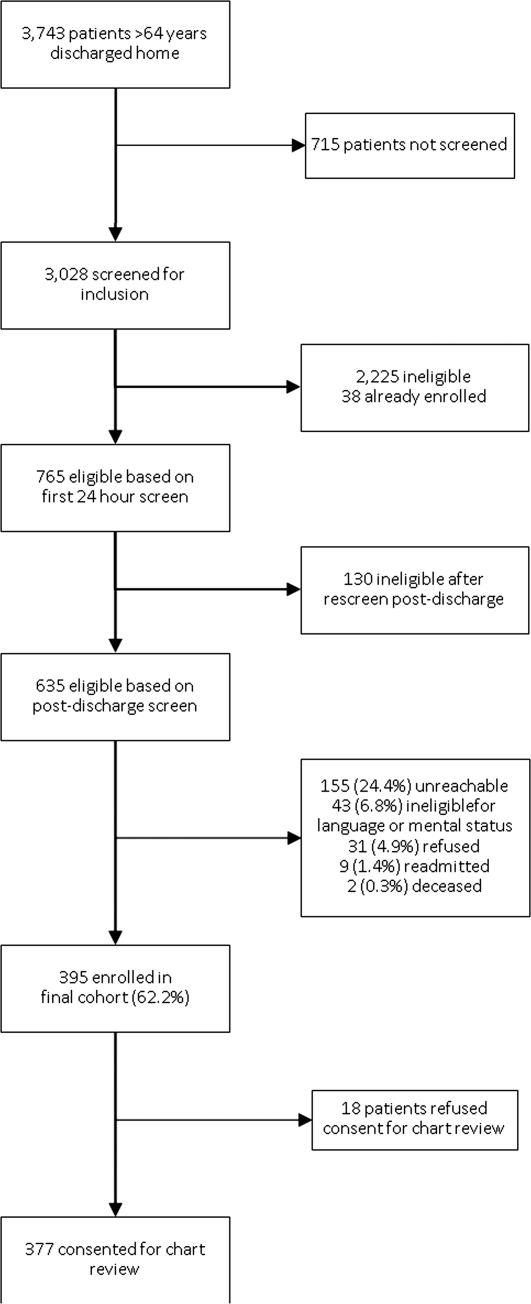

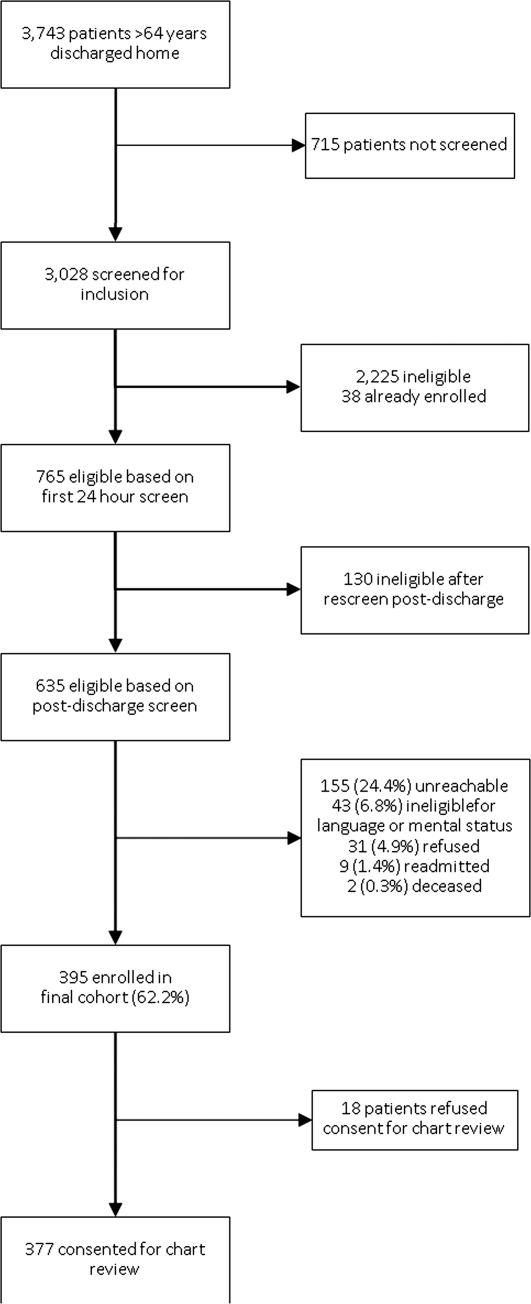

A total of 3743 patients over 64 years old were discharged home from the medical service at YNHH during the study period; 3028 patients were screened for eligibility within 24 hours of admission. We identified 635 eligible admissions and enrolled 395 patients (62.2%) in the study. Of these, 377 granted permission for chart review and were included in this analysis (Figure 1).

The study sample had a mean age of 77.1 years (standard deviation: 7.8); 205 (54.4%) were male and 310 (82.5%) were non‐Hispanic white. A total of 195 (51.7%) had ACS, 91 (24.1%) had pneumonia, and 146 (38.7%) had HF; 54 (14.3%) patients had more than 1 qualifying condition. There were similar numbers of patients on the cardiology, medicine housestaff, and medicine hospitalist teams (Table 1).

| Characteristic | N (%) or Mean (SD) |

|---|---|

| |

| Condition | |

| Acute coronary syndrome | 195 (51.7) |

| Community‐acquired pneumonia | 91 (24.1) |

| Heart failure | 146 (38.7) |

| Training level of summary dictator | |

| APRN | 140 (37.1) |

| House staff | 123 (32.6) |

| Hospitalist | 114 (30.2) |

| Length of stay, mean, d | 3.5 (2.5) |

| Total number of medications | 8.9 (3.3) |

| Identify a usual source of care | 360 (96.0) |

| Age, mean, y | 77.1 (7.8) |

| Male | 205 (54.4) |

| English‐speaking | 366 (98.1) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Non‐Hispanic white | 310 (82.5) |

| Non‐Hispanic black | 44 (11.7) |

| Hispanic | 15 (4.0) |

| Other | 7 (1.9) |

| High school graduate or GED Admission source | 268 (73.4) |

| Emergency department | 248 (66.0) |

| Direct transfer from hospital or nursing facility | 94 (25.0) |

| Direct admission from office | 34 (9.0) |

Timeliness

Discharge summaries were completed for 376/377 patients, of which 174 (46.3%) were dictated on the day of discharge. However, 122 (32.4%) summaries were dictated more than 48 hours after discharge, including 93 (24.7%) that were dictated more than 1 week after discharge (see Supporting Information, Appendix 3, in the online version of this article).

Summaries dictated by hospitalists were most likely to be done on the day of discharge (35.3% APRNs, 38.2% housestaff, 68.4% hospitalists, P<0.001). After adjustment for diagnosis and length of stay, hospitalists were still significantly more likely to produce a timely discharge summary than APRNs (OR: 2.82; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.56‐5.09), whereas housestaff were no different than APRNs (OR: 0.84; 95% CI: 0.48‐1.46).

Transmission

A total of 144 (38.3%) discharge summaries were not sent to any physician besides the inpatient attending, and 209/374 (55.9%) were not sent to at least 1 physician listed as having a follow‐up appointment planned with the patient. Each discharge summary was sent to a median of 1 physician besides the dictating physician (IQR: 01). However, for each summary, a median of 1 physician (IQR: 01) who had a scheduled follow‐up with the patient did not receive the summary. Summaries dictated by hospitalists were most likely to be sent to at least 1 outside physician (54.7% APRNs, 58.5% housestaff, 73.7% hospitalists, P=0.006). Summaries dictated on the day of discharge were more likely than delayed summaries to be sent to at least 1 outside physician (75.9% vs 49.5%, P<0.001). After adjustment for diagnosis and length of stay, there was no longer a difference in likelihood of transmitting a discharge summary to any outpatient physician according to training level; however, dictations completed on the day of discharge remained significantly more likely to be transmitted to an outside physician (OR: 3.05; 95% CI: 1.88‐4.93) (Table 2).

| Explanatory Variable | Proportion Transmitted to at Least 1 Outside Physician | OR for Transmission to Any Outside Physician (95% CI) | Adjusted P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Training level | 0.52 | ||

| APRN | 54.7% | REF | |

| Housestaff | 58.5% | 1.17 (0.66‐2.06) | |

| Hospitalist | 73.7% | 1.46 (0.76‐2.79) | |

| Timeliness | |||

| Dictated after discharge | 49.5% | REF | <0.001 |

| Dictated day of discharge | 75.9% | 3.05 (1.88‐4.93) | |

| Acute coronary syndrome vs nota | 52.1 % | 1.05 (0.49‐2.26) | 0.89 |

| Pneumonia vs nota | 69.2 % | 1.59 (0.66‐3.79) | 0.30 |

| Heart failure vs nota | 74.7 % | 3.32 (1.61‐6.84) | 0.001 |

| Length of stay, d | 0.91 (0.83‐1.00) | 0.06 | |

Content

Rate of inclusion of each content element is shown in Table 3, overall and by training level. Nearly every discharge summary included information about admitting diagnosis, hospital course, and procedures or tests performed during the hospitalization. However, few summaries included information about the patient's condition at discharge. Less than half included discharge laboratory results; less than one‐third included functional capacity, cognitive capacity, or discharge physical exam. Only 4.1% overall of discharge summaries for patients with HF included the patient's weight at discharge; best were hospitalists who still included this information in only 7.7% of summaries. Information about postdischarge care, including home social support, pending tests, or recommended follow‐up tests/procedures was also rarely specified. Last, only 6.2% of discharge summaries included the name and contact number of the inpatient physician; this information was least likely to be provided by housestaff (1.6%) and most likely to be provided by hospitalists (15.2%) (P<0.001).

| Discharge Summary Component | Overall, n=377, n (%) | APRN, n=140, n (%) | Housestaff, n=123, n (%) | Hospitalist, n=114, n (%) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Diagnosisab | 368 (97.9) | 136 (97.8) | 120 (97.6) | 112 (98.3) | 1.00 |

| Discharge second diagnosisb | 289 (76.9) | 100 (71.9) | 89 (72.4) | 100 (87.7) | <0.001 |

| Hospital coursea | 375 (100.0) | 138 (100) | 123 (100) | 114 (100) | N/A |

| Procedures/tests performed during admissionab | 374 (99.7) | 138 (99.3) | 123 (100) | 113 (100) | N/A |

| Patient and family instructionsa | 371 (98.4) | 136 (97.1) | 122 (99.2) | 113 (99.1) | .43 |

| Social support or living situation of patient | 148 (39.5) | 18 (12.9) | 62 (50.4) | 68 (60.2) | <0.001 |

| Functional capacity at dischargea | 99 (26.4) | 37 (26.6) | 32 (26.0) | 30 (26.6) | 0.99 |

| Cognitive capacity at dischargeab | 30 (8.0) | 6 (4.4) | 11 (8.9) | 13 (11.5) | 0.10 |

| Physical exam at dischargea | 62 (16.7) | 19 (13.8) | 16 (13.1) | 27 (24.1) | 0.04 |

| Laboratory results at time of dischargea | 164 (43.9) | 63 (45.3) | 50 (40.7) | 51 (45.5) | 0.68 |

| Back to baseline or other nonspecific remark about discharge statusa | 71 (19.0) | 30 (21.6) | 18 (14.8) | 23 (20.4) | 0.34 |

| Any test or result still pending or specific comment that nothing is pendingb | 46 (12.2) | 9 (6.4) | 20 (16.3) | 17 (14.9) | 0.03 |

| Recommendation for follow‐up tests/procedures | 157 (41.9) | 43 (30.9) | 54 (43.9) | 60 (53.1) | 0.002 |

| Call‐back number of responsible in‐house physicianb | 23 (6.2) | 4 (2.9) | 2 (1.6) | 17 (15.2) | <0.001 |

| Resuscitation status | 27 (7.7) | 2 (1.5) | 18 (15.4) | 7 (6.7) | <0.001 |

| Etiology of heart failurec | 120 (82.8) | 44 (81.5) | 34 (87.2) | 42 (80.8) | 0.69 |

| Reason/trigger for exacerbationc | 86 (58.9) | 30 (55.6) | 27 (67.5) | 29 (55.8) | 0.43 |

| Ejection fractionc | 107 (73.3) | 40 (74.1) | 32 (80.0) | 35 (67.3) | 0.39 |

| Discharge weightc | 6 (4.1) | 1 (1.9) | 1 (2.5) | 4 (7.7) | 0.33 |

| Target weight rangec | 5 (3.4) | 0 (0) | 2 (5.0) | 3 (5.8) | 0.22 |

| Discharge creatinine or GFRc | 34 (23.3) | 14 (25.9) | 10 (25.0) | 10 (19.2) | 0.69 |

| If stent placed, whether drug‐eluting or notd | 89 (81.7) | 58 (87.9) | 27 (81.8) | 4 (40.0) | 0.001 |

On average, summaries included 5.6 of the 6 Joint Commission elements and 4.0 of the 7 TOCCC elements. A total of 63.0% of discharge summaries included all 6 elements required by The Joint Commission, whereas no discharge summary included all 7 TOCCC elements.

APRNs, housestaff and hospitalists included the same average number of The Joint Commission elements (5.6 each), but hospitalists on average included slightly more TOCCC elements (4.3) than did housestaff (4.0) or APRNs (3.8) (P<0.001). Summaries dictated on the day of discharge included an average of 4.2 TOCCC elements, compared to 3.9 TOCCC elements in delayed discharge. In multivariable analyses adjusted for diagnosis and length of stay, there was still no difference by training level in presence of The Joint Commission elements, but hospitalists were significantly more likely to include more TOCCC elements than APRNs (OR: 2.70; 95% CI: 1.49‐4.90) (Table 4). Summaries dictated on the day of discharge were significantly more likely to include more TOCCC elements (OR: 1.92; 95% CI: 1.23‐2.99).

| Explanatory Variable | Average Number of TOCCC Elements Included | OR (95% CI) | Adjusted P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Training level | 0.004 | ||

| APRN | 3.8 | REF | |

| Housestaff | 4.0 | 1.54 (0.90‐2.62) | |

| Hospitalist | 4.3 | 2.70 (1.49‐4.90) | |

| Timeliness | |||

| Dictated after discharge | 3.9 | REF | |

| Dictated day of discharge | 4.2 | 1.92 (1.23‐2.99) | 0.004 |

| Acute coronary syndrome vs nota | 3.9 | 0.72 (0.37‐1.39) | 0.33 |

| Pneumonia vs nota | 4.2 | 1.02 (0.49‐2.14) | 0.95 |

| Heart failure vs nota | 4.1 | 1.49 (0.80‐2.78) | 0.21 |

| Length of stay, d | 0.99 (0.90‐1.07) | 0.73 | |

No discharge summary included all 7 TOCCC‐endorsed content elements, was dictated on the day of discharge, and was sent to an outside physician.

DISCUSSION

In this prospective single‐site study of medical patients with 3 common conditions, we found that discharge summaries were completed relatively promptly, but were often not sent to the appropriate outpatient physicians. We also found that summaries were uniformly excellent at providing details of the hospitalization, but less reliable at providing details relevant to transitional care such as the patient's condition on discharge or existence of pending tests. On average, summaries included 57% of the elements included in consensus guidelines by 6 major medical societies. The content of discharge summaries dictated by hospitalists was slightly more comprehensive than that of APRNs and trainees, but no group exhibited high performance. In fact, not one discharge summary fully met all 3 quality criteria of timeliness, transmission, and content.

Our study, unlike most in the field, focused on multiple dimensions of discharge summary quality simultaneously. For instance, previous studies have found that timely receipt of a discharge summary does not reduce readmission rates.[11, 14, 15] Yet, if the content of the discharge summary is inadequate for postdischarge care, the summary may not be useful even if it is received by the follow‐up visit. Conversely, high‐quality content is ineffective if the summary is not sent to the outpatient physician.

This study suggests several avenues for improving summary quality. Timely discharge summaries in this study were more likely to include key content and to be transmitted to the appropriate physician. Strategies to improve discharge summary quality should therefore prioritize timely summaries, which can be expected to have downstream benefits for other aspects of quality. Some studies have found that templates improve discharge summary content.[22] In our institution, a template exists, but it favors a hospitalization‐focused rather than transition‐focused approach to the discharge summary. For instance, it includes instructions to dictate the admission exam, but not the discharge exam. Thus, designing templates specifically for transitional care is key. Maximizing capabilities of electronic records may help; many content elements that were commonly missing (e.g., pending results, discharge vitals, discharge weight) could be automatically inserted from electronic records. Likewise, automatic transmission of the summary to care providers listed in the electronic record might ameliorate many transmission failures. Some efforts have been made to convert existing electronic data into discharge summaries.[23, 24, 25] However, these activities are very preliminary, and some studies have found the quality of electronic summaries to be lower than dictated or handwritten summaries.[26] As with all automated or electronic applications, it will be essential to consider workflow, readability, and ability to synthesize information prior to adoption.

Hospitalists consistently produced highest‐quality summaries, even though they did not receive explicit training, suggesting experience may be beneficial,[27, 28, 29] or that the hospitalist community focus on transitional care has been effective. In addition, hospitalists at our institution explicitly prioritize timely and comprehensive discharge dictations, because their business relies on maintaining good relationships with outpatient physicians who contract for their services. Housestaff and APRNs have no such incentives or policies; rather, they typically consider discharge summaries to be a useful source of patient history at the time of an admission or readmission. Other academic centers have found similar results.[6, 16] Nonetheless, even though hospitalists had slightly better performance in our study, large gaps in the quality of summaries remained for all groups including hospitalists.

This study has several limitations. First, as a single‐site study at an academic hospital, it may not be generalizable to other hospitals or other settings. It is noteworthy, however, that the average time to dictation in this study was much lower than that of other studies,[4, 14, 30, 31, 32] suggesting that practices at this institution are at least no worse and possibly better than elsewhere. Second, although there are some mandates and expert opinion‐based guidelines for discharge summary content, there is no validated evidence base to confirm what content ought to be present in discharge summaries to improve patient outcomes. Third, we had too few readmissions in the dataset to have enough power to determine whether discharge summary content, timeliness, or transmission predicts readmission. Fourth, we did not determine whether the information in discharge summaries was accurate or complete; we merely assessed whether it was present. For example, we gave every discharge summary full credit for including discharge medications because they are automatically appended. Yet medication reconciliation errors at discharge are common.[33, 34] In fact, in the DISCHARGE study cohort, more than a quarter of discharge medication lists contained a suspected error.[35]

In summary, this study demonstrated the inadequacy of the contemporary discharge summary for conveying information that is critical to the transition from hospital to home. It may be that hospital culture treats hospitalizations as discrete and self‐contained events rather than as components of a larger episode of care. As interest in reducing readmissions rises, reframing the discharge summary to serve as a transitional tool and targeting it for quality assessment will likely be necessary.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Amy Browning and the staff of the Center for Outcomes Research and Evaluation Follow‐Up Center for conducting patient interviews, Mark Abroms and Katherine Herman for patient recruitment and screening, and Peter Charpentier for Web site development.

Disclosures

At the time this study was conducted, Dr. Horwitz was supported by the CTSA Grant UL1 RR024139 and KL2 RR024138 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and NIH roadmap for Medical Research, and was a Centers of Excellence Scholar in Geriatric Medicine by the John A. Hartford Foundation and the American Federation for Aging Research. Dr. Horwitz is now supported by the National Institute on Aging (K08 AG038336) and by the American Federation for Aging Research through the Paul B. Beeson Career Development Award Program. This work was also supported by a grant from the Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center at Yale University School of Medicine (P30AG021342 NIH/NIA). Dr. Krumholz is supported by grant U01 HL105270‐01 (Center for Cardiovascular Outcomes Research at Yale University) from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. No funding source had any role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Aging, the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, the National Institutes of Health, The John A. Hartford Foundation, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, or the American Federation for Aging Research. Dr. Horwitz had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. An earlier version of this work was presented as an oral presentation at the Society of General Internal Medicine Annual Meeting in Orlando, Florida on May 12, 2012. Dr. Krumholz chairs a cardiac scientific advisory board for UnitedHealth. Dr. Krumholz receives support from the Centers of Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to develop and maintain performance measures that are used for public reporting, including readmission measures.

APPENDIX

A

Dictation guidelines provided to house staff and hospitalists

DICTATION GUIDELINES

FORMAT OF DISCHARGE SUMMARY

- Your name(spell it out), andPatient name(spell it out as well)

- Medical record number, date of admission, date of discharge

- Attending physician

- Disposition

- Principal and other diagnoses, Principal and other operations/procedures

- Copies to be sent to other physicians

- Begin narrative: CC, HPI, PMHx, Medications on admit, Social, Family Hx, Physical exam on admission, Data (labs on admission, plus labs relevant to workup, significant changes at discharge, admission EKG, radiologic and other data),Hospital course by problem, discharge meds, follow‐up appointments

APPENDIX

B

| Diagnosis |

| Discharge Second Diagnosis |

| Hospital course |

| Procedures/tests performed during admission |

| Patient and Family Instructions |

| Social support or living situation of patient |

| Functional capacity at discharge |

| Cognitive capacity at discharge |

| Physical exam at discharge |

| Laboratory results at time of discharge |

| Back to baseline or other nonspecific remark about discharge status |

| Any test or result still pending |

| Specific comment that nothing is pending |

| Recommendation for follow up tests/procedures |

| Call back number of responsible in‐house physician |

| Resuscitation status |

| Etiology of heart failure |

| Reason/trigger for exacerbation |

| Ejection fraction |

| Discharge weight |

| Target weight range |

| Discharge creatinine or GFR |

| If stent placed, whether drug‐eluting or not |

| Composite element | Data elements abstracted that qualify as meeting measure |

|---|---|

| Reason for hospitalization | Diagnosis |

| Significant findings | Hospital course |

| Procedures and treatment provided | Procedures/tests performed during admission |

| Patient's discharge condition | Functional capacity at discharge, Cognitive capacity at discharge, Physical exam at discharge, Laboratory results at time of discharge, Back to baseline or other nonspecific remark about discharge status |

| Patient and family instructions | Signs and symptoms to monitor at home |

| Attending physician's signature | Attending signature |

| Composite element | Data elements abstracted that qualify as meeting measure |

|---|---|

| Principal diagnosis | Diagnosis |

| Problem list | Discharge second diagnosis |

| Medication list | [Automatically appended; full credit to every summary] |

| Transferring physician name and contact information | Call back number of responsible in‐house physician |

| Cognitive status of the patient | Cognitive capacity at discharge |

| Test results | Procedures/tests performed during admission |

| Pending test results | Any test or result still pending or specific comment that nothing is pending |

APPENDIX

C

Histogram of days between discharge and dictation

- , , . Value of the specialist's report. Br Med J. 1960;2(5213):1663–1664.

- , . Communications between general practitioners and consultants. Br Med J. 1974;4(5942):456–459.

- , , . A functional hospital discharge summary. J Pediatr. 1975;86(1):97–98.

- , , , , , . Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital‐based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA. 2007;297(8):831–841.

- , , , et al. Patient safety concerns arising from test results that return after hospital discharge. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143(2):121–128.

- , , , et al. Adequacy of hospital discharge summaries in documenting tests with pending results and outpatient follow‐up providers. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(9):1002–1006.

- , , . Tying up loose ends: discharging patients with unresolved medical issues. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(12):1305–1311.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Condition of participation: medical record services. 42. Vol 482.C.F.R. § 482.24 (2012).

- Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. Hospital Accreditation Standards. Standard IM 6.10 EP 7–9. Oakbrook Terrace, IL: The Joint Commission; 2008.

- , . Documentation of mandated discharge summary components in transitions from acute to subacute care. In: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, ed. Advances in Patient Safety: New Directions and Alternative Approaches. Vol 2: Culture and Redesign. AHRQ Publication No. 08-0034‐2. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2008:179–188.

- , , , et al. Hospital discharge documentation and risk of rehospitalisation. BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;20(9):773–778.

- , , , et al. Transition of care for hospitalized elderly patients‐development of a discharge checklist for hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2006;1(6):354–360.

- , , , et al. Transitions of Care Consensus Policy Statement American College of Physicians‐Society of General Internal Medicine‐Society of Hospital Medicine‐American Geriatrics Society‐American College of Emergency Physicians‐Society of Academic Emergency Medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(8):971–976.

- , , , et al. Association of communication between hospital‐based physicians and primary care providers with patient outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(3):381–386.

- , , , . Effect of discharge summary availability during post‐discharge visits on hospital readmission. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(3):186–192.

- , , , , . Provider characteristics, clinical‐work processes and their relationship to discharge summary quality for sub‐acute care patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(1):78–84.

- , , , et al. ACC/AHA 2007 guidelines for the management of patients with unstable angina/non‐ST‐elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2002 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Unstable Angina/Non‐ST‐Elevation Myocardial Infarction) developed in collaboration with the American College of Emergency Physicians, the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons endorsed by the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation and the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50(7):e1–e157.

- , , . Universal definition of myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2007;28(20):2525–2538.

- , , , et al. ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2008: the Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2008 of the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the Heart Failure Association of the ESC (HFA) and endorsed by the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM). Eur J Heart Fail. 2008;10(10):933–989.

- , , , et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community‐acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(suppl 2):S27–S72.

- , , , et al. Clock drawing in Alzheimer's disease. A novel measure of dementia severity. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1989;37(8):725–729.

- , , , , . Assessing quality and efficiency of discharge summaries. Am J Med Qual. 2005;20(6):337–343.

- , , , et al. Electronic versus dictated hospital discharge summaries: a randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(9):995–1001.

- , , , . Dictated versus database‐generated discharge summaries: a randomized clinical trial. CMAJ. 1999;160(3):319–326.

- , , , , . Computerised updating of clinical summaries: new opportunities for clinical practice and research? BMJ. 1988;297(6662):1504–1506.

- , , . Evaluation of electronic discharge summaries: a comparison of documentation in electronic and handwritten discharge summaries. Int J Med Inform. 2008;77(9):613–620.

- , , , , . Did I do as best as the system would let me? Healthcare professional views on hospital to home care transitions. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(12):1649–1656.

- , , , , . Learning by doing—resident perspectives on developing competency in high‐quality discharge care. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(9):1188–1194.

- , , , , . Out of sight, out of mind: housestaff perceptions of quality‐limiting factors in discharge care at teaching hospitals. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(5):376–381.

- , , . Dissemination of discharge summaries. Not reaching follow‐up physicians. Can Fam Physician. 2002;48:737–742.

- , , , . Primary care physician attitudes regarding communication with hospitalists. Am J Med. 2001;111(9B):15S–20S.

- , , , . General practitioner‐hospital communications: a review of discharge summaries. J Qual Clin Pract. 2001;21(4):104–108.

- , , . Accuracy of information on medicines in hospital discharge summaries. Intern Med J. 2006;36(4):221–225.

- , , . Accuracy of medication documentation in hospital discharge summaries: A retrospective analysis of medication transcription errors in manual and electronic discharge summaries. Int J Med Inform. 2010;79(1):58–64.

- , , , . Medication reconciliation accuracy and patient understanding of intended medication changes on hospital discharge. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(11):1513–1520.

Hospitalized patients are often cared for by physicians who do not follow them in the community, creating a discontinuity of care that must be bridged through communication. This communication between inpatient and outpatient physicians occurs, in part via a discharge summary, which is intended to summarize events during hospitalization and prepare the outpatient physician to resume care of the patient. Yet, this form of communication has long been problematic.[1, 2, 3] In a 1960 study, only 30% of discharge letters were received by the primary care physician within 48 hours of discharge.[1]

More recent studies have shown little improvement. Direct communication between hospital and outpatient physicians is rare, and discharge summaries are still largely unavailable at the time of follow‐up.[4] In 1 study, primary care physicians were unaware of 62% of laboratory tests or study results that were pending on discharge,[5] in part because this information is missing from most discharge summaries.[6] Deficits such as these persist despite the fact that the rate of postdischarge completion of recommended tests, referrals, or procedures is significantly increased when the recommendation is included in the discharge summary.[7]

Regulatory mandates for discharge summaries from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services[8] and from The Joint Commission[9] appear to be generally met[10, 11]; however, these mandates have no requirements for timeliness stricter than 30 days, do not require that summaries be transmitted to outpatient physicians, and do not require several content elements that might be useful to outside physicians such as condition of the patient at discharge, cognitive and functional status, goals of care, or pending studies. Expert opinion guidelines have more comprehensive recommendations,[12, 13] but it is uncertain how widely they are followed.

The existence of a discharge summary does not necessarily mean it serves a patient well in the transitional period.[11, 14, 15] Discharge summaries are a complex intervention, and we do not yet understand the best ways discharge summaries may fulfill needs specific to transitional care. Furthermore, it is uncertain what factors improve aspects of discharge summary quality as defined by timeliness, transmission, and content.[6, 16]

The goal of the DIagnosing Systemic failures, Complexities and HARm in GEriatric discharges study (DISCHARGE) was to comprehensively assess the discharge process for older patients discharged to the community. In this article we examine discharge summaries of patients enrolled in the study to determine the timeliness, transmission to outside physicians, and content of the summaries. We further examine the effect of provider training level and timeliness of dictation on discharge summary quality.

METHODS

Study Cohort

The DISCHARGE study was a prospective, observational cohort study of patients 65 years or older discharged to home from YaleNew Haven Hospital (YNHH) who were admitted with acute coronary syndrome (ACS), community‐acquired pneumonia, or heart failure (HF). Patients were screened by physicians for eligibility within 24 hours of admission using specialty society guidelines[17, 18, 19, 20] and were enrolled by telephone within 1 week of discharge. Additional inclusion criteria included speaking English or Spanish, and ability of the patient or caregiver to participate in a telephone interview. Patients enrolled in hospice were excluded, as were patients who failed the Mini‐Cog mental status screen (3‐item recall and a clock draw)[21] while in the hospital or appeared confused or delirious during the telephone interview. Caregivers of cognitively impaired patients were eligible for enrollment instead if the patient provided permission.

Study Setting

YNHH is a 966‐bed urban tertiary care hospital with statistically lower than the national average mortality for acute myocardial infarction, HF, and pneumonia but statistically higher than the national average for 30‐day readmission rates for HF and pneumonia at the time this study was conducted. Advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs) working under the supervision of private or university cardiologists provided care for cardiology service patients. Housestaff under the supervision of university or hospitalist attending physicians, or physician assistants or APRNs under the supervision of hospitalist attending physicians provided care for patients on medical services. Discharge summaries were typically dictated by APRNs for cardiology patients, by 2nd‐ or 3rd‐year residents for housestaff patients, and by hospitalists for hospitalist patients. A dictation guideline was provided to housestaff and hospitalists (see Supporting Information, Appendix 1, in the online version of this article); this guideline suggested including basic demographic information, disposition and diagnoses, the admission history and physical, hospital course, discharge medications, and follow‐up appointments. Additionally, housestaff received a lecture about discharge summaries at the start of their 2nd year. Discharge instructions including medications and follow‐up appointment information were automatically appended to the discharge summaries. Summaries were sent by the medical records department only to physicians in the system who were listed by the dictating physician as needing to receive a copy of the summary; no summary was automatically sent (ie, to the primary care physician) if not requested by the dictating physician.

Data Collection

Experienced registered nurses trained in chart abstraction conducted explicit reviews of medical charts using a standardized review tool. The tool included 24 questions about the discharge summary applicable to all 3 conditions, with 7 additional questions for patients with HF and 1 additional question for patients with ACS. These questions included the 6 elements required by The Joint Commission for all discharge summaries (reason for hospitalization, significant findings, procedures and treatment provided, patient's discharge condition, patient and family instructions, and attending physician's signature)[9] as well as the 7 elements (principal diagnosis and problem list, medication list, transferring physician name and contact information, cognitive status of the patient, test results, and pending test results) recommended by the Transitions of Care Consensus Conference (TOCCC), a recent consensus statement produced by 6 major medical societies.[13] Each content element is shown in (see Supporting Information, Appendix 2, in the online version of this article), which also indicates the elements included in the 2 guidelines.

Main Measures

We assessed quality in 3 main domains: timeliness, transmission, and content. We defined timeliness as days between discharge date and dictation date (not final signature date, which may occur later), and measured both median timeliness and proportion of discharge summaries completed on the day of discharge. We defined transmission as successful fax or mail of the discharge summary to an outside physician as reported by the medical records department, and measured the proportion of discharge summaries sent to any outside physician as well as the median number of physicians per discharge summary who were scheduled to follow‐up with the patient postdischarge but who did not receive a copy of the summary. We defined 21 individual content items and assessed the frequency of each individual content item. We also measured compliance with The Joint Commission mandates and TOCCC recommendations, which included several of the individual content items.

To measure compliance with The Joint Commission requirements, we created a composite score in which 1 point was provided for the presence of each of the 6 required elements (maximum score=6). Every discharge summary received 1 point for attending physician signature, because all discharge summaries were electronically signed. Discharge instructions to family/patients were automatically appended to every discharge summary; however, we gave credit for patient and family instructions only to those that included any information about signs and symptoms to monitor for at home. We defined discharge condition as any information about functional status, cognitive status, physical exam, or laboratory findings at discharge.

To measure compliance with specialty society recommendations for discharge summaries, we created a composite score in which 1 point was provided for the presence of each of the 7 recommended elements (maximum score=7). Every discharge summary received 1 point for discharge medications, because these are automatically appended.

We obtained data on age, race, gender, and length of stay from hospital administrative databases. The study was approved by the Yale Human Investigation Committee, and verbal informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Statistical Analysis

Characteristics of the sample are described with counts and percentages or means and standard deviations. Medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) or counts and percentages were calculated for summary measures of timeliness, transmission, and content. We assessed differences in quality measures between APRNs, housestaff, and hospitalists using 2 tests. We conducted multivariable logistic regression analyses for timeliness and for transmission to any outside physician. All discharge summaries included at least 4 of The Joint Commission elements; consequently, we coded this content outcome as an ordinal variable with 3 levels indicating inclusion of 4, 5, or 6 of The Joint Commission elements. We coded the TOCCC content outcome as a 3‐level variable indicating <4, 4, or >4 elements satisfied. Accordingly, proportional odds models were used, in which the reported odds ratios (ORs) can be interpreted as the average effect of the explanatory variable on the odds of having more recommendations, for any dichotomization of the outcome. Residual analysis and goodness‐of‐fit statistics were used to assess model fit; the proportional odds assumption was tested. Statistical analyses were conducted with SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). P values <0.05 were interpreted as statistically significant for 2‐sided tests.

RESULTS

Enrollment and Study Sample

A total of 3743 patients over 64 years old were discharged home from the medical service at YNHH during the study period; 3028 patients were screened for eligibility within 24 hours of admission. We identified 635 eligible admissions and enrolled 395 patients (62.2%) in the study. Of these, 377 granted permission for chart review and were included in this analysis (Figure 1).

The study sample had a mean age of 77.1 years (standard deviation: 7.8); 205 (54.4%) were male and 310 (82.5%) were non‐Hispanic white. A total of 195 (51.7%) had ACS, 91 (24.1%) had pneumonia, and 146 (38.7%) had HF; 54 (14.3%) patients had more than 1 qualifying condition. There were similar numbers of patients on the cardiology, medicine housestaff, and medicine hospitalist teams (Table 1).

| Characteristic | N (%) or Mean (SD) |

|---|---|

| |

| Condition | |

| Acute coronary syndrome | 195 (51.7) |

| Community‐acquired pneumonia | 91 (24.1) |

| Heart failure | 146 (38.7) |

| Training level of summary dictator | |

| APRN | 140 (37.1) |

| House staff | 123 (32.6) |

| Hospitalist | 114 (30.2) |

| Length of stay, mean, d | 3.5 (2.5) |

| Total number of medications | 8.9 (3.3) |

| Identify a usual source of care | 360 (96.0) |

| Age, mean, y | 77.1 (7.8) |

| Male | 205 (54.4) |

| English‐speaking | 366 (98.1) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Non‐Hispanic white | 310 (82.5) |

| Non‐Hispanic black | 44 (11.7) |

| Hispanic | 15 (4.0) |

| Other | 7 (1.9) |

| High school graduate or GED Admission source | 268 (73.4) |

| Emergency department | 248 (66.0) |

| Direct transfer from hospital or nursing facility | 94 (25.0) |

| Direct admission from office | 34 (9.0) |

Timeliness

Discharge summaries were completed for 376/377 patients, of which 174 (46.3%) were dictated on the day of discharge. However, 122 (32.4%) summaries were dictated more than 48 hours after discharge, including 93 (24.7%) that were dictated more than 1 week after discharge (see Supporting Information, Appendix 3, in the online version of this article).

Summaries dictated by hospitalists were most likely to be done on the day of discharge (35.3% APRNs, 38.2% housestaff, 68.4% hospitalists, P<0.001). After adjustment for diagnosis and length of stay, hospitalists were still significantly more likely to produce a timely discharge summary than APRNs (OR: 2.82; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.56‐5.09), whereas housestaff were no different than APRNs (OR: 0.84; 95% CI: 0.48‐1.46).

Transmission

A total of 144 (38.3%) discharge summaries were not sent to any physician besides the inpatient attending, and 209/374 (55.9%) were not sent to at least 1 physician listed as having a follow‐up appointment planned with the patient. Each discharge summary was sent to a median of 1 physician besides the dictating physician (IQR: 01). However, for each summary, a median of 1 physician (IQR: 01) who had a scheduled follow‐up with the patient did not receive the summary. Summaries dictated by hospitalists were most likely to be sent to at least 1 outside physician (54.7% APRNs, 58.5% housestaff, 73.7% hospitalists, P=0.006). Summaries dictated on the day of discharge were more likely than delayed summaries to be sent to at least 1 outside physician (75.9% vs 49.5%, P<0.001). After adjustment for diagnosis and length of stay, there was no longer a difference in likelihood of transmitting a discharge summary to any outpatient physician according to training level; however, dictations completed on the day of discharge remained significantly more likely to be transmitted to an outside physician (OR: 3.05; 95% CI: 1.88‐4.93) (Table 2).

| Explanatory Variable | Proportion Transmitted to at Least 1 Outside Physician | OR for Transmission to Any Outside Physician (95% CI) | Adjusted P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Training level | 0.52 | ||

| APRN | 54.7% | REF | |

| Housestaff | 58.5% | 1.17 (0.66‐2.06) | |

| Hospitalist | 73.7% | 1.46 (0.76‐2.79) | |

| Timeliness | |||

| Dictated after discharge | 49.5% | REF | <0.001 |

| Dictated day of discharge | 75.9% | 3.05 (1.88‐4.93) | |

| Acute coronary syndrome vs nota | 52.1 % | 1.05 (0.49‐2.26) | 0.89 |

| Pneumonia vs nota | 69.2 % | 1.59 (0.66‐3.79) | 0.30 |

| Heart failure vs nota | 74.7 % | 3.32 (1.61‐6.84) | 0.001 |

| Length of stay, d | 0.91 (0.83‐1.00) | 0.06 | |

Content

Rate of inclusion of each content element is shown in Table 3, overall and by training level. Nearly every discharge summary included information about admitting diagnosis, hospital course, and procedures or tests performed during the hospitalization. However, few summaries included information about the patient's condition at discharge. Less than half included discharge laboratory results; less than one‐third included functional capacity, cognitive capacity, or discharge physical exam. Only 4.1% overall of discharge summaries for patients with HF included the patient's weight at discharge; best were hospitalists who still included this information in only 7.7% of summaries. Information about postdischarge care, including home social support, pending tests, or recommended follow‐up tests/procedures was also rarely specified. Last, only 6.2% of discharge summaries included the name and contact number of the inpatient physician; this information was least likely to be provided by housestaff (1.6%) and most likely to be provided by hospitalists (15.2%) (P<0.001).

| Discharge Summary Component | Overall, n=377, n (%) | APRN, n=140, n (%) | Housestaff, n=123, n (%) | Hospitalist, n=114, n (%) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Diagnosisab | 368 (97.9) | 136 (97.8) | 120 (97.6) | 112 (98.3) | 1.00 |

| Discharge second diagnosisb | 289 (76.9) | 100 (71.9) | 89 (72.4) | 100 (87.7) | <0.001 |

| Hospital coursea | 375 (100.0) | 138 (100) | 123 (100) | 114 (100) | N/A |

| Procedures/tests performed during admissionab | 374 (99.7) | 138 (99.3) | 123 (100) | 113 (100) | N/A |

| Patient and family instructionsa | 371 (98.4) | 136 (97.1) | 122 (99.2) | 113 (99.1) | .43 |

| Social support or living situation of patient | 148 (39.5) | 18 (12.9) | 62 (50.4) | 68 (60.2) | <0.001 |

| Functional capacity at dischargea | 99 (26.4) | 37 (26.6) | 32 (26.0) | 30 (26.6) | 0.99 |

| Cognitive capacity at dischargeab | 30 (8.0) | 6 (4.4) | 11 (8.9) | 13 (11.5) | 0.10 |

| Physical exam at dischargea | 62 (16.7) | 19 (13.8) | 16 (13.1) | 27 (24.1) | 0.04 |

| Laboratory results at time of dischargea | 164 (43.9) | 63 (45.3) | 50 (40.7) | 51 (45.5) | 0.68 |

| Back to baseline or other nonspecific remark about discharge statusa | 71 (19.0) | 30 (21.6) | 18 (14.8) | 23 (20.4) | 0.34 |

| Any test or result still pending or specific comment that nothing is pendingb | 46 (12.2) | 9 (6.4) | 20 (16.3) | 17 (14.9) | 0.03 |

| Recommendation for follow‐up tests/procedures | 157 (41.9) | 43 (30.9) | 54 (43.9) | 60 (53.1) | 0.002 |

| Call‐back number of responsible in‐house physicianb | 23 (6.2) | 4 (2.9) | 2 (1.6) | 17 (15.2) | <0.001 |

| Resuscitation status | 27 (7.7) | 2 (1.5) | 18 (15.4) | 7 (6.7) | <0.001 |

| Etiology of heart failurec | 120 (82.8) | 44 (81.5) | 34 (87.2) | 42 (80.8) | 0.69 |

| Reason/trigger for exacerbationc | 86 (58.9) | 30 (55.6) | 27 (67.5) | 29 (55.8) | 0.43 |

| Ejection fractionc | 107 (73.3) | 40 (74.1) | 32 (80.0) | 35 (67.3) | 0.39 |

| Discharge weightc | 6 (4.1) | 1 (1.9) | 1 (2.5) | 4 (7.7) | 0.33 |

| Target weight rangec | 5 (3.4) | 0 (0) | 2 (5.0) | 3 (5.8) | 0.22 |

| Discharge creatinine or GFRc | 34 (23.3) | 14 (25.9) | 10 (25.0) | 10 (19.2) | 0.69 |

| If stent placed, whether drug‐eluting or notd | 89 (81.7) | 58 (87.9) | 27 (81.8) | 4 (40.0) | 0.001 |

On average, summaries included 5.6 of the 6 Joint Commission elements and 4.0 of the 7 TOCCC elements. A total of 63.0% of discharge summaries included all 6 elements required by The Joint Commission, whereas no discharge summary included all 7 TOCCC elements.

APRNs, housestaff and hospitalists included the same average number of The Joint Commission elements (5.6 each), but hospitalists on average included slightly more TOCCC elements (4.3) than did housestaff (4.0) or APRNs (3.8) (P<0.001). Summaries dictated on the day of discharge included an average of 4.2 TOCCC elements, compared to 3.9 TOCCC elements in delayed discharge. In multivariable analyses adjusted for diagnosis and length of stay, there was still no difference by training level in presence of The Joint Commission elements, but hospitalists were significantly more likely to include more TOCCC elements than APRNs (OR: 2.70; 95% CI: 1.49‐4.90) (Table 4). Summaries dictated on the day of discharge were significantly more likely to include more TOCCC elements (OR: 1.92; 95% CI: 1.23‐2.99).

| Explanatory Variable | Average Number of TOCCC Elements Included | OR (95% CI) | Adjusted P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Training level | 0.004 | ||

| APRN | 3.8 | REF | |

| Housestaff | 4.0 | 1.54 (0.90‐2.62) | |

| Hospitalist | 4.3 | 2.70 (1.49‐4.90) | |

| Timeliness | |||

| Dictated after discharge | 3.9 | REF | |

| Dictated day of discharge | 4.2 | 1.92 (1.23‐2.99) | 0.004 |

| Acute coronary syndrome vs nota | 3.9 | 0.72 (0.37‐1.39) | 0.33 |

| Pneumonia vs nota | 4.2 | 1.02 (0.49‐2.14) | 0.95 |

| Heart failure vs nota | 4.1 | 1.49 (0.80‐2.78) | 0.21 |

| Length of stay, d | 0.99 (0.90‐1.07) | 0.73 | |

No discharge summary included all 7 TOCCC‐endorsed content elements, was dictated on the day of discharge, and was sent to an outside physician.

DISCUSSION

In this prospective single‐site study of medical patients with 3 common conditions, we found that discharge summaries were completed relatively promptly, but were often not sent to the appropriate outpatient physicians. We also found that summaries were uniformly excellent at providing details of the hospitalization, but less reliable at providing details relevant to transitional care such as the patient's condition on discharge or existence of pending tests. On average, summaries included 57% of the elements included in consensus guidelines by 6 major medical societies. The content of discharge summaries dictated by hospitalists was slightly more comprehensive than that of APRNs and trainees, but no group exhibited high performance. In fact, not one discharge summary fully met all 3 quality criteria of timeliness, transmission, and content.

Our study, unlike most in the field, focused on multiple dimensions of discharge summary quality simultaneously. For instance, previous studies have found that timely receipt of a discharge summary does not reduce readmission rates.[11, 14, 15] Yet, if the content of the discharge summary is inadequate for postdischarge care, the summary may not be useful even if it is received by the follow‐up visit. Conversely, high‐quality content is ineffective if the summary is not sent to the outpatient physician.

This study suggests several avenues for improving summary quality. Timely discharge summaries in this study were more likely to include key content and to be transmitted to the appropriate physician. Strategies to improve discharge summary quality should therefore prioritize timely summaries, which can be expected to have downstream benefits for other aspects of quality. Some studies have found that templates improve discharge summary content.[22] In our institution, a template exists, but it favors a hospitalization‐focused rather than transition‐focused approach to the discharge summary. For instance, it includes instructions to dictate the admission exam, but not the discharge exam. Thus, designing templates specifically for transitional care is key. Maximizing capabilities of electronic records may help; many content elements that were commonly missing (e.g., pending results, discharge vitals, discharge weight) could be automatically inserted from electronic records. Likewise, automatic transmission of the summary to care providers listed in the electronic record might ameliorate many transmission failures. Some efforts have been made to convert existing electronic data into discharge summaries.[23, 24, 25] However, these activities are very preliminary, and some studies have found the quality of electronic summaries to be lower than dictated or handwritten summaries.[26] As with all automated or electronic applications, it will be essential to consider workflow, readability, and ability to synthesize information prior to adoption.

Hospitalists consistently produced highest‐quality summaries, even though they did not receive explicit training, suggesting experience may be beneficial,[27, 28, 29] or that the hospitalist community focus on transitional care has been effective. In addition, hospitalists at our institution explicitly prioritize timely and comprehensive discharge dictations, because their business relies on maintaining good relationships with outpatient physicians who contract for their services. Housestaff and APRNs have no such incentives or policies; rather, they typically consider discharge summaries to be a useful source of patient history at the time of an admission or readmission. Other academic centers have found similar results.[6, 16] Nonetheless, even though hospitalists had slightly better performance in our study, large gaps in the quality of summaries remained for all groups including hospitalists.

This study has several limitations. First, as a single‐site study at an academic hospital, it may not be generalizable to other hospitals or other settings. It is noteworthy, however, that the average time to dictation in this study was much lower than that of other studies,[4, 14, 30, 31, 32] suggesting that practices at this institution are at least no worse and possibly better than elsewhere. Second, although there are some mandates and expert opinion‐based guidelines for discharge summary content, there is no validated evidence base to confirm what content ought to be present in discharge summaries to improve patient outcomes. Third, we had too few readmissions in the dataset to have enough power to determine whether discharge summary content, timeliness, or transmission predicts readmission. Fourth, we did not determine whether the information in discharge summaries was accurate or complete; we merely assessed whether it was present. For example, we gave every discharge summary full credit for including discharge medications because they are automatically appended. Yet medication reconciliation errors at discharge are common.[33, 34] In fact, in the DISCHARGE study cohort, more than a quarter of discharge medication lists contained a suspected error.[35]

In summary, this study demonstrated the inadequacy of the contemporary discharge summary for conveying information that is critical to the transition from hospital to home. It may be that hospital culture treats hospitalizations as discrete and self‐contained events rather than as components of a larger episode of care. As interest in reducing readmissions rises, reframing the discharge summary to serve as a transitional tool and targeting it for quality assessment will likely be necessary.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Amy Browning and the staff of the Center for Outcomes Research and Evaluation Follow‐Up Center for conducting patient interviews, Mark Abroms and Katherine Herman for patient recruitment and screening, and Peter Charpentier for Web site development.

Disclosures

At the time this study was conducted, Dr. Horwitz was supported by the CTSA Grant UL1 RR024139 and KL2 RR024138 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and NIH roadmap for Medical Research, and was a Centers of Excellence Scholar in Geriatric Medicine by the John A. Hartford Foundation and the American Federation for Aging Research. Dr. Horwitz is now supported by the National Institute on Aging (K08 AG038336) and by the American Federation for Aging Research through the Paul B. Beeson Career Development Award Program. This work was also supported by a grant from the Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center at Yale University School of Medicine (P30AG021342 NIH/NIA). Dr. Krumholz is supported by grant U01 HL105270‐01 (Center for Cardiovascular Outcomes Research at Yale University) from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. No funding source had any role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Aging, the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, the National Institutes of Health, The John A. Hartford Foundation, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, or the American Federation for Aging Research. Dr. Horwitz had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. An earlier version of this work was presented as an oral presentation at the Society of General Internal Medicine Annual Meeting in Orlando, Florida on May 12, 2012. Dr. Krumholz chairs a cardiac scientific advisory board for UnitedHealth. Dr. Krumholz receives support from the Centers of Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to develop and maintain performance measures that are used for public reporting, including readmission measures.

APPENDIX

A

Dictation guidelines provided to house staff and hospitalists

DICTATION GUIDELINES

FORMAT OF DISCHARGE SUMMARY

- Your name(spell it out), andPatient name(spell it out as well)

- Medical record number, date of admission, date of discharge

- Attending physician

- Disposition

- Principal and other diagnoses, Principal and other operations/procedures

- Copies to be sent to other physicians

- Begin narrative: CC, HPI, PMHx, Medications on admit, Social, Family Hx, Physical exam on admission, Data (labs on admission, plus labs relevant to workup, significant changes at discharge, admission EKG, radiologic and other data),Hospital course by problem, discharge meds, follow‐up appointments

APPENDIX

B

| Diagnosis |

| Discharge Second Diagnosis |

| Hospital course |

| Procedures/tests performed during admission |

| Patient and Family Instructions |

| Social support or living situation of patient |

| Functional capacity at discharge |

| Cognitive capacity at discharge |

| Physical exam at discharge |

| Laboratory results at time of discharge |

| Back to baseline or other nonspecific remark about discharge status |

| Any test or result still pending |

| Specific comment that nothing is pending |

| Recommendation for follow up tests/procedures |

| Call back number of responsible in‐house physician |

| Resuscitation status |

| Etiology of heart failure |

| Reason/trigger for exacerbation |

| Ejection fraction |

| Discharge weight |

| Target weight range |

| Discharge creatinine or GFR |

| If stent placed, whether drug‐eluting or not |

| Composite element | Data elements abstracted that qualify as meeting measure |

|---|---|

| Reason for hospitalization | Diagnosis |

| Significant findings | Hospital course |

| Procedures and treatment provided | Procedures/tests performed during admission |

| Patient's discharge condition | Functional capacity at discharge, Cognitive capacity at discharge, Physical exam at discharge, Laboratory results at time of discharge, Back to baseline or other nonspecific remark about discharge status |

| Patient and family instructions | Signs and symptoms to monitor at home |

| Attending physician's signature | Attending signature |

| Composite element | Data elements abstracted that qualify as meeting measure |

|---|---|

| Principal diagnosis | Diagnosis |

| Problem list | Discharge second diagnosis |

| Medication list | [Automatically appended; full credit to every summary] |

| Transferring physician name and contact information | Call back number of responsible in‐house physician |

| Cognitive status of the patient | Cognitive capacity at discharge |

| Test results | Procedures/tests performed during admission |

| Pending test results | Any test or result still pending or specific comment that nothing is pending |

APPENDIX

C

Histogram of days between discharge and dictation

Hospitalized patients are often cared for by physicians who do not follow them in the community, creating a discontinuity of care that must be bridged through communication. This communication between inpatient and outpatient physicians occurs, in part via a discharge summary, which is intended to summarize events during hospitalization and prepare the outpatient physician to resume care of the patient. Yet, this form of communication has long been problematic.[1, 2, 3] In a 1960 study, only 30% of discharge letters were received by the primary care physician within 48 hours of discharge.[1]

More recent studies have shown little improvement. Direct communication between hospital and outpatient physicians is rare, and discharge summaries are still largely unavailable at the time of follow‐up.[4] In 1 study, primary care physicians were unaware of 62% of laboratory tests or study results that were pending on discharge,[5] in part because this information is missing from most discharge summaries.[6] Deficits such as these persist despite the fact that the rate of postdischarge completion of recommended tests, referrals, or procedures is significantly increased when the recommendation is included in the discharge summary.[7]

Regulatory mandates for discharge summaries from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services[8] and from The Joint Commission[9] appear to be generally met[10, 11]; however, these mandates have no requirements for timeliness stricter than 30 days, do not require that summaries be transmitted to outpatient physicians, and do not require several content elements that might be useful to outside physicians such as condition of the patient at discharge, cognitive and functional status, goals of care, or pending studies. Expert opinion guidelines have more comprehensive recommendations,[12, 13] but it is uncertain how widely they are followed.

The existence of a discharge summary does not necessarily mean it serves a patient well in the transitional period.[11, 14, 15] Discharge summaries are a complex intervention, and we do not yet understand the best ways discharge summaries may fulfill needs specific to transitional care. Furthermore, it is uncertain what factors improve aspects of discharge summary quality as defined by timeliness, transmission, and content.[6, 16]

The goal of the DIagnosing Systemic failures, Complexities and HARm in GEriatric discharges study (DISCHARGE) was to comprehensively assess the discharge process for older patients discharged to the community. In this article we examine discharge summaries of patients enrolled in the study to determine the timeliness, transmission to outside physicians, and content of the summaries. We further examine the effect of provider training level and timeliness of dictation on discharge summary quality.

METHODS

Study Cohort

The DISCHARGE study was a prospective, observational cohort study of patients 65 years or older discharged to home from YaleNew Haven Hospital (YNHH) who were admitted with acute coronary syndrome (ACS), community‐acquired pneumonia, or heart failure (HF). Patients were screened by physicians for eligibility within 24 hours of admission using specialty society guidelines[17, 18, 19, 20] and were enrolled by telephone within 1 week of discharge. Additional inclusion criteria included speaking English or Spanish, and ability of the patient or caregiver to participate in a telephone interview. Patients enrolled in hospice were excluded, as were patients who failed the Mini‐Cog mental status screen (3‐item recall and a clock draw)[21] while in the hospital or appeared confused or delirious during the telephone interview. Caregivers of cognitively impaired patients were eligible for enrollment instead if the patient provided permission.

Study Setting

YNHH is a 966‐bed urban tertiary care hospital with statistically lower than the national average mortality for acute myocardial infarction, HF, and pneumonia but statistically higher than the national average for 30‐day readmission rates for HF and pneumonia at the time this study was conducted. Advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs) working under the supervision of private or university cardiologists provided care for cardiology service patients. Housestaff under the supervision of university or hospitalist attending physicians, or physician assistants or APRNs under the supervision of hospitalist attending physicians provided care for patients on medical services. Discharge summaries were typically dictated by APRNs for cardiology patients, by 2nd‐ or 3rd‐year residents for housestaff patients, and by hospitalists for hospitalist patients. A dictation guideline was provided to housestaff and hospitalists (see Supporting Information, Appendix 1, in the online version of this article); this guideline suggested including basic demographic information, disposition and diagnoses, the admission history and physical, hospital course, discharge medications, and follow‐up appointments. Additionally, housestaff received a lecture about discharge summaries at the start of their 2nd year. Discharge instructions including medications and follow‐up appointment information were automatically appended to the discharge summaries. Summaries were sent by the medical records department only to physicians in the system who were listed by the dictating physician as needing to receive a copy of the summary; no summary was automatically sent (ie, to the primary care physician) if not requested by the dictating physician.

Data Collection

Experienced registered nurses trained in chart abstraction conducted explicit reviews of medical charts using a standardized review tool. The tool included 24 questions about the discharge summary applicable to all 3 conditions, with 7 additional questions for patients with HF and 1 additional question for patients with ACS. These questions included the 6 elements required by The Joint Commission for all discharge summaries (reason for hospitalization, significant findings, procedures and treatment provided, patient's discharge condition, patient and family instructions, and attending physician's signature)[9] as well as the 7 elements (principal diagnosis and problem list, medication list, transferring physician name and contact information, cognitive status of the patient, test results, and pending test results) recommended by the Transitions of Care Consensus Conference (TOCCC), a recent consensus statement produced by 6 major medical societies.[13] Each content element is shown in (see Supporting Information, Appendix 2, in the online version of this article), which also indicates the elements included in the 2 guidelines.

Main Measures

We assessed quality in 3 main domains: timeliness, transmission, and content. We defined timeliness as days between discharge date and dictation date (not final signature date, which may occur later), and measured both median timeliness and proportion of discharge summaries completed on the day of discharge. We defined transmission as successful fax or mail of the discharge summary to an outside physician as reported by the medical records department, and measured the proportion of discharge summaries sent to any outside physician as well as the median number of physicians per discharge summary who were scheduled to follow‐up with the patient postdischarge but who did not receive a copy of the summary. We defined 21 individual content items and assessed the frequency of each individual content item. We also measured compliance with The Joint Commission mandates and TOCCC recommendations, which included several of the individual content items.

To measure compliance with The Joint Commission requirements, we created a composite score in which 1 point was provided for the presence of each of the 6 required elements (maximum score=6). Every discharge summary received 1 point for attending physician signature, because all discharge summaries were electronically signed. Discharge instructions to family/patients were automatically appended to every discharge summary; however, we gave credit for patient and family instructions only to those that included any information about signs and symptoms to monitor for at home. We defined discharge condition as any information about functional status, cognitive status, physical exam, or laboratory findings at discharge.

To measure compliance with specialty society recommendations for discharge summaries, we created a composite score in which 1 point was provided for the presence of each of the 7 recommended elements (maximum score=7). Every discharge summary received 1 point for discharge medications, because these are automatically appended.

We obtained data on age, race, gender, and length of stay from hospital administrative databases. The study was approved by the Yale Human Investigation Committee, and verbal informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Statistical Analysis