User login

Disease Education

Q) The billing consultant who came to our office said we can increase our reimbursements if we also provide education to our patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). Is she right?

In 2010, under an omnibus bill, kidney disease education (KDE) classes were added as a Medicare benefit. These are for patients with stage 4 CKD (glomerular filtration rate, 15-30 mL/min) and are to be taught by a qualified instructor (MD, PA, NP, or CNS).

The classes can be taught on the same day as an evaluation/management visit (ie, a regular office visit) and are compensated by the hour. (Side note: Medicare defines an hour as 31 minutes—yes, 31 minutes; Medicare takes for granted that you will also need time to chart!) You can teach two classes in the same day. Thus, if you wanted to, you could have a patient arrive for an office visit, then teach two 31-minute classes, and bill all three for the same day. The entire visit could be 75 minutes (although this may be exhausting for this population).

You can conduct the classes in a number of settings, including nursing homes, hospitals, skilled nursing facilities, the office, or even the patient’s home. Many PAs and NPs have taught these classes to hospitalized patients who have lost kidney function due to an acute insult (ie, medications, dehydration, contrast).

Each Medicare recipient has a lifetime benefit of six KDE classes. The CPT billing code is G0420 for an individual class and G0421 for a group class. You must make sure you also code for the stage 4 CKD diagnosis (code: 585.4).

Congress stipulated KDE classes must include information on causes, symptoms, and treatments and comprise a posttest at a specific health literacy level. To make it simple, the National Kidney Foundation Council of Advanced Practitioners (NKF-CAP) has developed two free Power-Point slide decks for clinicians to use in KDE classes (available at www.kidney.org/professionals/CAP/sub_resources#kde). References and updated peer-reviewed guidelines are included. You can print the slides for your patients and/or share the program with your colleagues.

Many nephrology practitioners teach the two slide sets over and over, because patients only retain one-third of the info we provide them on a given day. So if you teach each slide set three times, you have six lifetime classes—and hopefully the patient will have retained everything.

One caveat: Before you initiate KDE classes for a specific patient, check with the patient’s nephrology group (we hope at stage 4 the patient has a nephrologist) to see if they are providing the education. —KZ and JD

Kim Zuber, PA-C, MSPS, DFAAPA

American Academy of Nephrology PAs

Jane S. Davis, CRNP, DNP

Division of Nephrology at the University of Alabama

National Kidney Foundation's Council of Advanced Practitioners

Q) The billing consultant who came to our office said we can increase our reimbursements if we also provide education to our patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). Is she right?

In 2010, under an omnibus bill, kidney disease education (KDE) classes were added as a Medicare benefit. These are for patients with stage 4 CKD (glomerular filtration rate, 15-30 mL/min) and are to be taught by a qualified instructor (MD, PA, NP, or CNS).

The classes can be taught on the same day as an evaluation/management visit (ie, a regular office visit) and are compensated by the hour. (Side note: Medicare defines an hour as 31 minutes—yes, 31 minutes; Medicare takes for granted that you will also need time to chart!) You can teach two classes in the same day. Thus, if you wanted to, you could have a patient arrive for an office visit, then teach two 31-minute classes, and bill all three for the same day. The entire visit could be 75 minutes (although this may be exhausting for this population).

You can conduct the classes in a number of settings, including nursing homes, hospitals, skilled nursing facilities, the office, or even the patient’s home. Many PAs and NPs have taught these classes to hospitalized patients who have lost kidney function due to an acute insult (ie, medications, dehydration, contrast).

Each Medicare recipient has a lifetime benefit of six KDE classes. The CPT billing code is G0420 for an individual class and G0421 for a group class. You must make sure you also code for the stage 4 CKD diagnosis (code: 585.4).

Congress stipulated KDE classes must include information on causes, symptoms, and treatments and comprise a posttest at a specific health literacy level. To make it simple, the National Kidney Foundation Council of Advanced Practitioners (NKF-CAP) has developed two free Power-Point slide decks for clinicians to use in KDE classes (available at www.kidney.org/professionals/CAP/sub_resources#kde). References and updated peer-reviewed guidelines are included. You can print the slides for your patients and/or share the program with your colleagues.

Many nephrology practitioners teach the two slide sets over and over, because patients only retain one-third of the info we provide them on a given day. So if you teach each slide set three times, you have six lifetime classes—and hopefully the patient will have retained everything.

One caveat: Before you initiate KDE classes for a specific patient, check with the patient’s nephrology group (we hope at stage 4 the patient has a nephrologist) to see if they are providing the education. —KZ and JD

Kim Zuber, PA-C, MSPS, DFAAPA

American Academy of Nephrology PAs

Jane S. Davis, CRNP, DNP

Division of Nephrology at the University of Alabama

National Kidney Foundation's Council of Advanced Practitioners

Q) The billing consultant who came to our office said we can increase our reimbursements if we also provide education to our patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). Is she right?

In 2010, under an omnibus bill, kidney disease education (KDE) classes were added as a Medicare benefit. These are for patients with stage 4 CKD (glomerular filtration rate, 15-30 mL/min) and are to be taught by a qualified instructor (MD, PA, NP, or CNS).

The classes can be taught on the same day as an evaluation/management visit (ie, a regular office visit) and are compensated by the hour. (Side note: Medicare defines an hour as 31 minutes—yes, 31 minutes; Medicare takes for granted that you will also need time to chart!) You can teach two classes in the same day. Thus, if you wanted to, you could have a patient arrive for an office visit, then teach two 31-minute classes, and bill all three for the same day. The entire visit could be 75 minutes (although this may be exhausting for this population).

You can conduct the classes in a number of settings, including nursing homes, hospitals, skilled nursing facilities, the office, or even the patient’s home. Many PAs and NPs have taught these classes to hospitalized patients who have lost kidney function due to an acute insult (ie, medications, dehydration, contrast).

Each Medicare recipient has a lifetime benefit of six KDE classes. The CPT billing code is G0420 for an individual class and G0421 for a group class. You must make sure you also code for the stage 4 CKD diagnosis (code: 585.4).

Congress stipulated KDE classes must include information on causes, symptoms, and treatments and comprise a posttest at a specific health literacy level. To make it simple, the National Kidney Foundation Council of Advanced Practitioners (NKF-CAP) has developed two free Power-Point slide decks for clinicians to use in KDE classes (available at www.kidney.org/professionals/CAP/sub_resources#kde). References and updated peer-reviewed guidelines are included. You can print the slides for your patients and/or share the program with your colleagues.

Many nephrology practitioners teach the two slide sets over and over, because patients only retain one-third of the info we provide them on a given day. So if you teach each slide set three times, you have six lifetime classes—and hopefully the patient will have retained everything.

One caveat: Before you initiate KDE classes for a specific patient, check with the patient’s nephrology group (we hope at stage 4 the patient has a nephrologist) to see if they are providing the education. —KZ and JD

Kim Zuber, PA-C, MSPS, DFAAPA

American Academy of Nephrology PAs

Jane S. Davis, CRNP, DNP

Division of Nephrology at the University of Alabama

National Kidney Foundation's Council of Advanced Practitioners

Updates on Kidney Donation

Q) A good friend was diagnosed with chronic kidney disease (CKD) and is presently undergoing workup for a transplant. He is 60 and otherwise healthy; his glomerular filtration rate (GFR) is 14, and he has no uremic symptoms. If I volunteer to give him a kidney, are there any long-term risks for me?

Kidney failure, dialysis, and kidney transplant are terms that can invoke stress and uncertainty in patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) and among their family members and friends. In addition to adjusting to the changes wrought by ESRD, patients may also be burdened by the prospect of a family member or friend donating a kidney to them and the concern that the donation will lead to complications for their donor. Family members or friends who volunteer may also experience stress, uncertain of their own risk for ESRD in the future.

Past research improperly compared relative risk for ESRD in donors with that in the general population (without accounting for higher propensity for complications in donors with preexisting conditions). In an effort to correct this misperception, a study recently published in JAMA compared the risk for ESRD in donors with that in a healthy group of nondonors.1 The nondonor pool was taken from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III), which assesses the health and nutritional status of adults and children in the United States.

The JAMA study included a cohort of 96,217 kidney donors in the US in a 17-year period and a cohort of 20,024 participants in a six-year period of the NHANES III trial. This data was then compared to Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) data to determine the development of ESRD in kidney donors. ESRD was defined by CMS as the initiation of dialysis, placement on the kidney transplant waiting list, or receipt of a living or deceased donor kidney transplant.

In addition to comparing risk for ESRD in kidney donors with that of a healthy population of nondonors, the researchers also stratified their results demographically. Thus, the lifetime rate of kidney failure in donors is 90 per 10,000, compared with 326 per 10,000 in the general population of nondonors. In healthy nondonors, the risk for kidney failure was 14 per 10,000. After 15 years, the risk for kidney failure associated with donating a kidney was 51 per 10,000 in African-American donors and 23 per 10,000 in white donors. So while the study did reveal an increased risk associated with kidney donation, the degree of risk is considered small.

These findings demonstrate the importance of understanding the facts surrounding inherent risk for ESRD in kidney donation. Overall, a donor’s lifetime risk is considered minuscule. So, to answer the question, yes, there is a slight increase in risk for kidney failure if you donate to your friend. That said, the risk is 0.014 x a standardized risk of 1. This increases at 15 years to 0.51 for African-American and 0.23 for white donors. With such tiny increases, you can safely feel good about donating a kidney to your friend.

Donna Reesman, MSN, CNP

VP Clinical & Quality Management

St Clair Specialty Physicians Detroit

REFERENCES

1. Muzaale AD, Massie AB, Wang MC, et al. Risk of end-stage renal disease following live kidney donation. JAMA. 2014;311(6):579-586.

2. CDC. HIV in the United States: at a glance (2013). www.cdc.gov/hiv/statistics/basics/ataglance.html. Accessed June 16, 2014.

3. Frassetto LA, Tan-Tam C, Stock PG. Renal transplantation in patients with HIV. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2009;5(10):582-589.

4. Malani PN. New law allows organ transplants from deceased HIV-infected donors to HIV-infected recipients. JAMA. 2013;310(23): 2492-2493.

5. Muller E, Kahn D, Mendelson M. Renal transplantation between HIV-positive donors and recipients. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(24):2336-2337.

6. Mariani LH, Berns JS. Viral nephropathies. In: Gilbert SJ, Weiner DE, eds. National Kidney Foundation’s Primer on Kidney Diseases. 6th ed. Elsevier; 2014:253-261.

Q) A good friend was diagnosed with chronic kidney disease (CKD) and is presently undergoing workup for a transplant. He is 60 and otherwise healthy; his glomerular filtration rate (GFR) is 14, and he has no uremic symptoms. If I volunteer to give him a kidney, are there any long-term risks for me?

Kidney failure, dialysis, and kidney transplant are terms that can invoke stress and uncertainty in patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) and among their family members and friends. In addition to adjusting to the changes wrought by ESRD, patients may also be burdened by the prospect of a family member or friend donating a kidney to them and the concern that the donation will lead to complications for their donor. Family members or friends who volunteer may also experience stress, uncertain of their own risk for ESRD in the future.

Past research improperly compared relative risk for ESRD in donors with that in the general population (without accounting for higher propensity for complications in donors with preexisting conditions). In an effort to correct this misperception, a study recently published in JAMA compared the risk for ESRD in donors with that in a healthy group of nondonors.1 The nondonor pool was taken from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III), which assesses the health and nutritional status of adults and children in the United States.

The JAMA study included a cohort of 96,217 kidney donors in the US in a 17-year period and a cohort of 20,024 participants in a six-year period of the NHANES III trial. This data was then compared to Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) data to determine the development of ESRD in kidney donors. ESRD was defined by CMS as the initiation of dialysis, placement on the kidney transplant waiting list, or receipt of a living or deceased donor kidney transplant.

In addition to comparing risk for ESRD in kidney donors with that of a healthy population of nondonors, the researchers also stratified their results demographically. Thus, the lifetime rate of kidney failure in donors is 90 per 10,000, compared with 326 per 10,000 in the general population of nondonors. In healthy nondonors, the risk for kidney failure was 14 per 10,000. After 15 years, the risk for kidney failure associated with donating a kidney was 51 per 10,000 in African-American donors and 23 per 10,000 in white donors. So while the study did reveal an increased risk associated with kidney donation, the degree of risk is considered small.

These findings demonstrate the importance of understanding the facts surrounding inherent risk for ESRD in kidney donation. Overall, a donor’s lifetime risk is considered minuscule. So, to answer the question, yes, there is a slight increase in risk for kidney failure if you donate to your friend. That said, the risk is 0.014 x a standardized risk of 1. This increases at 15 years to 0.51 for African-American and 0.23 for white donors. With such tiny increases, you can safely feel good about donating a kidney to your friend.

Donna Reesman, MSN, CNP

VP Clinical & Quality Management

St Clair Specialty Physicians Detroit

REFERENCES

1. Muzaale AD, Massie AB, Wang MC, et al. Risk of end-stage renal disease following live kidney donation. JAMA. 2014;311(6):579-586.

2. CDC. HIV in the United States: at a glance (2013). www.cdc.gov/hiv/statistics/basics/ataglance.html. Accessed June 16, 2014.

3. Frassetto LA, Tan-Tam C, Stock PG. Renal transplantation in patients with HIV. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2009;5(10):582-589.

4. Malani PN. New law allows organ transplants from deceased HIV-infected donors to HIV-infected recipients. JAMA. 2013;310(23): 2492-2493.

5. Muller E, Kahn D, Mendelson M. Renal transplantation between HIV-positive donors and recipients. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(24):2336-2337.

6. Mariani LH, Berns JS. Viral nephropathies. In: Gilbert SJ, Weiner DE, eds. National Kidney Foundation’s Primer on Kidney Diseases. 6th ed. Elsevier; 2014:253-261.

Q) A good friend was diagnosed with chronic kidney disease (CKD) and is presently undergoing workup for a transplant. He is 60 and otherwise healthy; his glomerular filtration rate (GFR) is 14, and he has no uremic symptoms. If I volunteer to give him a kidney, are there any long-term risks for me?

Kidney failure, dialysis, and kidney transplant are terms that can invoke stress and uncertainty in patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) and among their family members and friends. In addition to adjusting to the changes wrought by ESRD, patients may also be burdened by the prospect of a family member or friend donating a kidney to them and the concern that the donation will lead to complications for their donor. Family members or friends who volunteer may also experience stress, uncertain of their own risk for ESRD in the future.

Past research improperly compared relative risk for ESRD in donors with that in the general population (without accounting for higher propensity for complications in donors with preexisting conditions). In an effort to correct this misperception, a study recently published in JAMA compared the risk for ESRD in donors with that in a healthy group of nondonors.1 The nondonor pool was taken from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III), which assesses the health and nutritional status of adults and children in the United States.

The JAMA study included a cohort of 96,217 kidney donors in the US in a 17-year period and a cohort of 20,024 participants in a six-year period of the NHANES III trial. This data was then compared to Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) data to determine the development of ESRD in kidney donors. ESRD was defined by CMS as the initiation of dialysis, placement on the kidney transplant waiting list, or receipt of a living or deceased donor kidney transplant.

In addition to comparing risk for ESRD in kidney donors with that of a healthy population of nondonors, the researchers also stratified their results demographically. Thus, the lifetime rate of kidney failure in donors is 90 per 10,000, compared with 326 per 10,000 in the general population of nondonors. In healthy nondonors, the risk for kidney failure was 14 per 10,000. After 15 years, the risk for kidney failure associated with donating a kidney was 51 per 10,000 in African-American donors and 23 per 10,000 in white donors. So while the study did reveal an increased risk associated with kidney donation, the degree of risk is considered small.

These findings demonstrate the importance of understanding the facts surrounding inherent risk for ESRD in kidney donation. Overall, a donor’s lifetime risk is considered minuscule. So, to answer the question, yes, there is a slight increase in risk for kidney failure if you donate to your friend. That said, the risk is 0.014 x a standardized risk of 1. This increases at 15 years to 0.51 for African-American and 0.23 for white donors. With such tiny increases, you can safely feel good about donating a kidney to your friend.

Donna Reesman, MSN, CNP

VP Clinical & Quality Management

St Clair Specialty Physicians Detroit

REFERENCES

1. Muzaale AD, Massie AB, Wang MC, et al. Risk of end-stage renal disease following live kidney donation. JAMA. 2014;311(6):579-586.

2. CDC. HIV in the United States: at a glance (2013). www.cdc.gov/hiv/statistics/basics/ataglance.html. Accessed June 16, 2014.

3. Frassetto LA, Tan-Tam C, Stock PG. Renal transplantation in patients with HIV. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2009;5(10):582-589.

4. Malani PN. New law allows organ transplants from deceased HIV-infected donors to HIV-infected recipients. JAMA. 2013;310(23): 2492-2493.

5. Muller E, Kahn D, Mendelson M. Renal transplantation between HIV-positive donors and recipients. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(24):2336-2337.

6. Mariani LH, Berns JS. Viral nephropathies. In: Gilbert SJ, Weiner DE, eds. National Kidney Foundation’s Primer on Kidney Diseases. 6th ed. Elsevier; 2014:253-261.

Kidney Donation & HIV

Q) Now that patients are living with HIV/AIDS, can they donate kidneys or receive a kidney transplant?

Kidney disease often has multiple causes, including hypertension, diabetes, inherited conditions, and viral illnesses. The latter include primarily HIV, hepatitis C, and hepatitis B. With advances in the treatment of viral illnesses, the question of whether patients with these viruses can donate or receive a kidney transplant is being discussed not only in the United States but also worldwide.

The most recent CDC figures estimate that more than 1.1 million people in the US are living with HIV, of whom one in six (or nearly 16%) are undiagnosed. There are approximately 50,000 new infections reported annually.2

The Organ Transplant Amendments Act of 1988 banned HIV-positive people from donating organs. However, with the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART, now often referred to as active antiretroviral therapy) and the effective prophylaxis and management of opportunistic infections, mortality has been reduced. HIV/AIDS is often seen as a chronic disease and not the death sentence it once was.3 Since the development of HAART, there have been successful transplants to HIV-positive recipients from non–HIV-infected donors.

In November 2013, President Obama signed the HIV Organ Policy Equity (HOPE) Act, which lifted the ban on using organs from HIV-infected donors. The legislation directs the Department of Health and Human Services and the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network to develop standards to make these transplants possible.4

Although there have not been any documented cases of transplants from HIV-infected donors to HIV-infected recipients in this country, such transplants have been very successful in South Africa.5 There, to qualify for kidney transplant, all recipients must have proven adherence, virologic suppression, and immune constitution. Donor suitability is defined as HIV infection (confirmed with the use of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay), absence of proteinuria, and a normal kidney as assessed with post hoc renal biopsy.5

One of the chief concerns has been the effect of further immunosuppression on the recipients and the possibility of disease progression. Although the sample size is limited (four transplants), data from the available cases indicate no evidence of organ rejection at 12 months post-transplantation. In addition, the recipients’ CD4 counts remained lower than baseline due to immunosuppressive therapy. All four patients maintained a viral load of less than 50 copies, which suggested that any virus transplanted along with the kidney had not affected control of HIV infection.5 However, it should be noted that many of the agents used for posttransplant maintenance immunosuppression (mycophenolate mofetil, cyclosporine, tacrolimus, and sirolimus) have antiretroviral properties.3

HIV patients in the US must meet the following criteria to be listed for a transplant:

• Diagnosis of ESRD with at least a five-year life-expectancy

• CD4 count of > 200 cells/ μL for at least six months

• Undetectable HIV viremia (< 50 HIV-1 RNA copies/mL)

• Demonstrated adherence to stable antiviral regimen for at least six months

• Absence of AIDS-defining illness following successful immune reconstitution6

A prospective trial of 150 patients in 19 US transplant centers who met the above criteria demonstrated patient survival and graft survival rates comparable to those in patients ages 65 and older.6

While awaiting the donation, HIV patients can continue hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis. With the improved antiviral drugs, HIV patients have a survival rate similar to the non–HIV-infected population.

Transplantation is the goal and certainly the hope of many advanced-stage kidney patients, but in reality, the need far exceeds the resources. The HOPE Act opens the door for many patients who were previously excluded from the possibility of a life without dialysis. Taking care of these patients will be a team effort, encompassing HIV and infectious disease specialists, pharmacists, nephrologists, transplant surgeons and coordinators, and primary care providers—including, of course, advanced practitioners.

Shelly Levinstein, MSN, CRNP

Nephrology Associates of York

York, PA

REFERENCES

1. Muzaale AD, Massie AB, Wang MC, et al. Risk of end-stage renal disease following live kidney donation. JAMA. 2014;311(6):579-586.

2. CDC. HIV in the United States: at a glance (2013). www.cdc.gov/hiv/statistics/basics/ataglance.html. Accessed June 16, 2014.

3. Frassetto LA, Tan-Tam C, Stock PG. Renal transplantation in patients with HIV. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2009;5(10):582-589.

4. Malani PN. New law allows organ transplants from deceased HIV-infected donors to HIV-infected recipients. JAMA. 2013;310(23): 2492-2493.

5. Muller E, Kahn D, Mendelson M. Renal transplantation between HIV-positive donors and recipients. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(24):2336-2337.

6. Mariani LH, Berns JS. Viral nephropathies. In: Gilbert SJ, Weiner DE, eds. National Kidney Foundation’s Primer on Kidney Diseases. 6th ed. Elsevier; 2014:253-261.

Q) Now that patients are living with HIV/AIDS, can they donate kidneys or receive a kidney transplant?

Kidney disease often has multiple causes, including hypertension, diabetes, inherited conditions, and viral illnesses. The latter include primarily HIV, hepatitis C, and hepatitis B. With advances in the treatment of viral illnesses, the question of whether patients with these viruses can donate or receive a kidney transplant is being discussed not only in the United States but also worldwide.

The most recent CDC figures estimate that more than 1.1 million people in the US are living with HIV, of whom one in six (or nearly 16%) are undiagnosed. There are approximately 50,000 new infections reported annually.2

The Organ Transplant Amendments Act of 1988 banned HIV-positive people from donating organs. However, with the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART, now often referred to as active antiretroviral therapy) and the effective prophylaxis and management of opportunistic infections, mortality has been reduced. HIV/AIDS is often seen as a chronic disease and not the death sentence it once was.3 Since the development of HAART, there have been successful transplants to HIV-positive recipients from non–HIV-infected donors.

In November 2013, President Obama signed the HIV Organ Policy Equity (HOPE) Act, which lifted the ban on using organs from HIV-infected donors. The legislation directs the Department of Health and Human Services and the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network to develop standards to make these transplants possible.4

Although there have not been any documented cases of transplants from HIV-infected donors to HIV-infected recipients in this country, such transplants have been very successful in South Africa.5 There, to qualify for kidney transplant, all recipients must have proven adherence, virologic suppression, and immune constitution. Donor suitability is defined as HIV infection (confirmed with the use of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay), absence of proteinuria, and a normal kidney as assessed with post hoc renal biopsy.5

One of the chief concerns has been the effect of further immunosuppression on the recipients and the possibility of disease progression. Although the sample size is limited (four transplants), data from the available cases indicate no evidence of organ rejection at 12 months post-transplantation. In addition, the recipients’ CD4 counts remained lower than baseline due to immunosuppressive therapy. All four patients maintained a viral load of less than 50 copies, which suggested that any virus transplanted along with the kidney had not affected control of HIV infection.5 However, it should be noted that many of the agents used for posttransplant maintenance immunosuppression (mycophenolate mofetil, cyclosporine, tacrolimus, and sirolimus) have antiretroviral properties.3

HIV patients in the US must meet the following criteria to be listed for a transplant:

• Diagnosis of ESRD with at least a five-year life-expectancy

• CD4 count of > 200 cells/ μL for at least six months

• Undetectable HIV viremia (< 50 HIV-1 RNA copies/mL)

• Demonstrated adherence to stable antiviral regimen for at least six months

• Absence of AIDS-defining illness following successful immune reconstitution6

A prospective trial of 150 patients in 19 US transplant centers who met the above criteria demonstrated patient survival and graft survival rates comparable to those in patients ages 65 and older.6

While awaiting the donation, HIV patients can continue hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis. With the improved antiviral drugs, HIV patients have a survival rate similar to the non–HIV-infected population.

Transplantation is the goal and certainly the hope of many advanced-stage kidney patients, but in reality, the need far exceeds the resources. The HOPE Act opens the door for many patients who were previously excluded from the possibility of a life without dialysis. Taking care of these patients will be a team effort, encompassing HIV and infectious disease specialists, pharmacists, nephrologists, transplant surgeons and coordinators, and primary care providers—including, of course, advanced practitioners.

Shelly Levinstein, MSN, CRNP

Nephrology Associates of York

York, PA

REFERENCES

1. Muzaale AD, Massie AB, Wang MC, et al. Risk of end-stage renal disease following live kidney donation. JAMA. 2014;311(6):579-586.

2. CDC. HIV in the United States: at a glance (2013). www.cdc.gov/hiv/statistics/basics/ataglance.html. Accessed June 16, 2014.

3. Frassetto LA, Tan-Tam C, Stock PG. Renal transplantation in patients with HIV. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2009;5(10):582-589.

4. Malani PN. New law allows organ transplants from deceased HIV-infected donors to HIV-infected recipients. JAMA. 2013;310(23): 2492-2493.

5. Muller E, Kahn D, Mendelson M. Renal transplantation between HIV-positive donors and recipients. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(24):2336-2337.

6. Mariani LH, Berns JS. Viral nephropathies. In: Gilbert SJ, Weiner DE, eds. National Kidney Foundation’s Primer on Kidney Diseases. 6th ed. Elsevier; 2014:253-261.

Q) Now that patients are living with HIV/AIDS, can they donate kidneys or receive a kidney transplant?

Kidney disease often has multiple causes, including hypertension, diabetes, inherited conditions, and viral illnesses. The latter include primarily HIV, hepatitis C, and hepatitis B. With advances in the treatment of viral illnesses, the question of whether patients with these viruses can donate or receive a kidney transplant is being discussed not only in the United States but also worldwide.

The most recent CDC figures estimate that more than 1.1 million people in the US are living with HIV, of whom one in six (or nearly 16%) are undiagnosed. There are approximately 50,000 new infections reported annually.2

The Organ Transplant Amendments Act of 1988 banned HIV-positive people from donating organs. However, with the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART, now often referred to as active antiretroviral therapy) and the effective prophylaxis and management of opportunistic infections, mortality has been reduced. HIV/AIDS is often seen as a chronic disease and not the death sentence it once was.3 Since the development of HAART, there have been successful transplants to HIV-positive recipients from non–HIV-infected donors.

In November 2013, President Obama signed the HIV Organ Policy Equity (HOPE) Act, which lifted the ban on using organs from HIV-infected donors. The legislation directs the Department of Health and Human Services and the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network to develop standards to make these transplants possible.4

Although there have not been any documented cases of transplants from HIV-infected donors to HIV-infected recipients in this country, such transplants have been very successful in South Africa.5 There, to qualify for kidney transplant, all recipients must have proven adherence, virologic suppression, and immune constitution. Donor suitability is defined as HIV infection (confirmed with the use of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay), absence of proteinuria, and a normal kidney as assessed with post hoc renal biopsy.5

One of the chief concerns has been the effect of further immunosuppression on the recipients and the possibility of disease progression. Although the sample size is limited (four transplants), data from the available cases indicate no evidence of organ rejection at 12 months post-transplantation. In addition, the recipients’ CD4 counts remained lower than baseline due to immunosuppressive therapy. All four patients maintained a viral load of less than 50 copies, which suggested that any virus transplanted along with the kidney had not affected control of HIV infection.5 However, it should be noted that many of the agents used for posttransplant maintenance immunosuppression (mycophenolate mofetil, cyclosporine, tacrolimus, and sirolimus) have antiretroviral properties.3

HIV patients in the US must meet the following criteria to be listed for a transplant:

• Diagnosis of ESRD with at least a five-year life-expectancy

• CD4 count of > 200 cells/ μL for at least six months

• Undetectable HIV viremia (< 50 HIV-1 RNA copies/mL)

• Demonstrated adherence to stable antiviral regimen for at least six months

• Absence of AIDS-defining illness following successful immune reconstitution6

A prospective trial of 150 patients in 19 US transplant centers who met the above criteria demonstrated patient survival and graft survival rates comparable to those in patients ages 65 and older.6

While awaiting the donation, HIV patients can continue hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis. With the improved antiviral drugs, HIV patients have a survival rate similar to the non–HIV-infected population.

Transplantation is the goal and certainly the hope of many advanced-stage kidney patients, but in reality, the need far exceeds the resources. The HOPE Act opens the door for many patients who were previously excluded from the possibility of a life without dialysis. Taking care of these patients will be a team effort, encompassing HIV and infectious disease specialists, pharmacists, nephrologists, transplant surgeons and coordinators, and primary care providers—including, of course, advanced practitioners.

Shelly Levinstein, MSN, CRNP

Nephrology Associates of York

York, PA

REFERENCES

1. Muzaale AD, Massie AB, Wang MC, et al. Risk of end-stage renal disease following live kidney donation. JAMA. 2014;311(6):579-586.

2. CDC. HIV in the United States: at a glance (2013). www.cdc.gov/hiv/statistics/basics/ataglance.html. Accessed June 16, 2014.

3. Frassetto LA, Tan-Tam C, Stock PG. Renal transplantation in patients with HIV. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2009;5(10):582-589.

4. Malani PN. New law allows organ transplants from deceased HIV-infected donors to HIV-infected recipients. JAMA. 2013;310(23): 2492-2493.

5. Muller E, Kahn D, Mendelson M. Renal transplantation between HIV-positive donors and recipients. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(24):2336-2337.

6. Mariani LH, Berns JS. Viral nephropathies. In: Gilbert SJ, Weiner DE, eds. National Kidney Foundation’s Primer on Kidney Diseases. 6th ed. Elsevier; 2014:253-261.

Anemia, A1C, and Rhabdomyolysis

Q) Does anemia in CKD patients affect their A1C? Is A1C accurate in CKD patients?

Tight glycemic control is imperative for patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD), but the management of diabetes in CKD can be complex due to factors including anemia and changes in glucose and insulin homeostasis.

A1C is directly proportionate to the ambient blood glucose concentration and in the general diabetic population has proven to be a reliable marker.1 However, it may not be valid in patients with diabetes and CKD. Reduced red blood cell (RBC) lifespan, rapid hemolysis, and iron deficiency may lead to falsely decreased results.2 Decreased RBC survival results from an increase in hemoglobin turnover, which decreases glycemic exposure time.1 This process then lowers the amount of nonenzymatic glucose binding to hemoglobin.1 Folate deficiency caused by impaired intestinal absorption in CKD also affects RBC survival.3 Falsely increased results may be related to carbamylation of the hemoglobin and acidosis, both of which are influenced by uremia.2

Special considerations should be made for dialysis patients with diabetes. In hemodialysis patients, A1C may be falsely decreased due to blood loss, RBC transfusion, and erythropoietin therapy.3 Observational studies have shown that erythropoietin therapy is associated with lower A1C due to the increased number of immature RBCs that have a decreased glycemic exposure time.1 In peritoneal dialysis patients, A1C may increase after the start of therapy as a result of dialysate absorption.3

Research suggests that glycated albumin (GA) provides a short-term index of glycemic control (typically two to three weeks) and is not influenced by albumin concentration, RBC lifespan, or erythropoietin administration.1 A clear consensus on optimal levels of GA has not been established, but GA may be a more reliable marker of glycemic control in patients with diabetes and CKD. Further research is needed to establish a target GA level that predicts the best prognosis for patients with both conditions.1

A1C is the most reliable marker at this time, but special considerations should be made for the patient with CKD. Rather than focus on a single measurement, clinicians need to consider the patient’s symptoms and results from all labwork, along with A1C, to best evaluate glycemic control.4 Further research is needed in patients with diabetes and CKD to explore other reliable markers to help maintain tight glycemic control.

Continued on next page >>

Q) One of my patients developed severe leg cramps while taking statins. I felt it was questionable rhabdomyolysis and stopped the medication; the leg pain went away. Is there a way to know if the rhabdomyolysis is progressive?

Rhabdomyolysis is a serious condition caused by the breakdown of muscle tissue that leads to the release of myoglobin into the bloodstream. This condition can lead to severe kidney failure and death.

Previously, there has been no easy method to predict progressive rhabdomyolysis. But researchers from Brigham and Women’s Hospital recently developed the Rhabdomyolysis Risk Calculator, a prediction score that can help determine whether a patient with rhabdomyolysis is at risk for severe kidney failure or death.

The researchers conducted a retrospective cohort study of 2,371 patients admitted between 2000 and 2011 and examined variables that may be associated with kidney failure and death.5 They identified independent predictors for these outcomes, including age; gender; initial levels of phosphate, calcium, creatinine, carbon dioxide, and creatine kinase; and etiology of rhabdomyolysis (myositis, exercise, statin use, or seizure).5

This tool can assist providers in developing a patient-specific treatment plan. However, further research is needed to validate the current variables, verify the risk prediction score in other populations, and examine its ability to guide individualized treatment plans.

The Rhabdomyolysis Risk Calculator is available at www.brighamandwomens.org/research/rhabdo/default.aspx

Kristy Washinger, MSN, CRNP

Nephrology Associates of Central PA

Camp Hill, PA

REFERENCES

1. Vos FE, Schollum JB, Walker RJ. Glycated albumin is the preferred marker for assessing glycaemic control in advanced chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant Plus. 2011; 4(6):368-375.

2. National Kidney Foundation Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative. Clinical practice guidelines and clinical practice recommendations for diabetes and chronic kidney disease. Guideline 2: management of hyperglycemia and general diabetes care in chronic kidney disease. www.kidney.org/professionals/kdoqi/guideline_diabetes/guide2.htm. Accessed April 15, 2014.

3. Sharif A, Baboolal K. Diagnostic application of the A1c assay in renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21(3):383-385.

4. American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes—2013. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(suppl 1):S11-S66.

5. McMahon GM, Zeng X, Walker SS. A risk prediction score for kidney failure or mortality in rhabdomyolysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(19):1821-1828.

Q) Does anemia in CKD patients affect their A1C? Is A1C accurate in CKD patients?

Tight glycemic control is imperative for patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD), but the management of diabetes in CKD can be complex due to factors including anemia and changes in glucose and insulin homeostasis.

A1C is directly proportionate to the ambient blood glucose concentration and in the general diabetic population has proven to be a reliable marker.1 However, it may not be valid in patients with diabetes and CKD. Reduced red blood cell (RBC) lifespan, rapid hemolysis, and iron deficiency may lead to falsely decreased results.2 Decreased RBC survival results from an increase in hemoglobin turnover, which decreases glycemic exposure time.1 This process then lowers the amount of nonenzymatic glucose binding to hemoglobin.1 Folate deficiency caused by impaired intestinal absorption in CKD also affects RBC survival.3 Falsely increased results may be related to carbamylation of the hemoglobin and acidosis, both of which are influenced by uremia.2

Special considerations should be made for dialysis patients with diabetes. In hemodialysis patients, A1C may be falsely decreased due to blood loss, RBC transfusion, and erythropoietin therapy.3 Observational studies have shown that erythropoietin therapy is associated with lower A1C due to the increased number of immature RBCs that have a decreased glycemic exposure time.1 In peritoneal dialysis patients, A1C may increase after the start of therapy as a result of dialysate absorption.3

Research suggests that glycated albumin (GA) provides a short-term index of glycemic control (typically two to three weeks) and is not influenced by albumin concentration, RBC lifespan, or erythropoietin administration.1 A clear consensus on optimal levels of GA has not been established, but GA may be a more reliable marker of glycemic control in patients with diabetes and CKD. Further research is needed to establish a target GA level that predicts the best prognosis for patients with both conditions.1

A1C is the most reliable marker at this time, but special considerations should be made for the patient with CKD. Rather than focus on a single measurement, clinicians need to consider the patient’s symptoms and results from all labwork, along with A1C, to best evaluate glycemic control.4 Further research is needed in patients with diabetes and CKD to explore other reliable markers to help maintain tight glycemic control.

Continued on next page >>

Q) One of my patients developed severe leg cramps while taking statins. I felt it was questionable rhabdomyolysis and stopped the medication; the leg pain went away. Is there a way to know if the rhabdomyolysis is progressive?

Rhabdomyolysis is a serious condition caused by the breakdown of muscle tissue that leads to the release of myoglobin into the bloodstream. This condition can lead to severe kidney failure and death.

Previously, there has been no easy method to predict progressive rhabdomyolysis. But researchers from Brigham and Women’s Hospital recently developed the Rhabdomyolysis Risk Calculator, a prediction score that can help determine whether a patient with rhabdomyolysis is at risk for severe kidney failure or death.

The researchers conducted a retrospective cohort study of 2,371 patients admitted between 2000 and 2011 and examined variables that may be associated with kidney failure and death.5 They identified independent predictors for these outcomes, including age; gender; initial levels of phosphate, calcium, creatinine, carbon dioxide, and creatine kinase; and etiology of rhabdomyolysis (myositis, exercise, statin use, or seizure).5

This tool can assist providers in developing a patient-specific treatment plan. However, further research is needed to validate the current variables, verify the risk prediction score in other populations, and examine its ability to guide individualized treatment plans.

The Rhabdomyolysis Risk Calculator is available at www.brighamandwomens.org/research/rhabdo/default.aspx

Kristy Washinger, MSN, CRNP

Nephrology Associates of Central PA

Camp Hill, PA

REFERENCES

1. Vos FE, Schollum JB, Walker RJ. Glycated albumin is the preferred marker for assessing glycaemic control in advanced chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant Plus. 2011; 4(6):368-375.

2. National Kidney Foundation Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative. Clinical practice guidelines and clinical practice recommendations for diabetes and chronic kidney disease. Guideline 2: management of hyperglycemia and general diabetes care in chronic kidney disease. www.kidney.org/professionals/kdoqi/guideline_diabetes/guide2.htm. Accessed April 15, 2014.

3. Sharif A, Baboolal K. Diagnostic application of the A1c assay in renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21(3):383-385.

4. American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes—2013. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(suppl 1):S11-S66.

5. McMahon GM, Zeng X, Walker SS. A risk prediction score for kidney failure or mortality in rhabdomyolysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(19):1821-1828.

Q) Does anemia in CKD patients affect their A1C? Is A1C accurate in CKD patients?

Tight glycemic control is imperative for patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD), but the management of diabetes in CKD can be complex due to factors including anemia and changes in glucose and insulin homeostasis.

A1C is directly proportionate to the ambient blood glucose concentration and in the general diabetic population has proven to be a reliable marker.1 However, it may not be valid in patients with diabetes and CKD. Reduced red blood cell (RBC) lifespan, rapid hemolysis, and iron deficiency may lead to falsely decreased results.2 Decreased RBC survival results from an increase in hemoglobin turnover, which decreases glycemic exposure time.1 This process then lowers the amount of nonenzymatic glucose binding to hemoglobin.1 Folate deficiency caused by impaired intestinal absorption in CKD also affects RBC survival.3 Falsely increased results may be related to carbamylation of the hemoglobin and acidosis, both of which are influenced by uremia.2

Special considerations should be made for dialysis patients with diabetes. In hemodialysis patients, A1C may be falsely decreased due to blood loss, RBC transfusion, and erythropoietin therapy.3 Observational studies have shown that erythropoietin therapy is associated with lower A1C due to the increased number of immature RBCs that have a decreased glycemic exposure time.1 In peritoneal dialysis patients, A1C may increase after the start of therapy as a result of dialysate absorption.3

Research suggests that glycated albumin (GA) provides a short-term index of glycemic control (typically two to three weeks) and is not influenced by albumin concentration, RBC lifespan, or erythropoietin administration.1 A clear consensus on optimal levels of GA has not been established, but GA may be a more reliable marker of glycemic control in patients with diabetes and CKD. Further research is needed to establish a target GA level that predicts the best prognosis for patients with both conditions.1

A1C is the most reliable marker at this time, but special considerations should be made for the patient with CKD. Rather than focus on a single measurement, clinicians need to consider the patient’s symptoms and results from all labwork, along with A1C, to best evaluate glycemic control.4 Further research is needed in patients with diabetes and CKD to explore other reliable markers to help maintain tight glycemic control.

Continued on next page >>

Q) One of my patients developed severe leg cramps while taking statins. I felt it was questionable rhabdomyolysis and stopped the medication; the leg pain went away. Is there a way to know if the rhabdomyolysis is progressive?

Rhabdomyolysis is a serious condition caused by the breakdown of muscle tissue that leads to the release of myoglobin into the bloodstream. This condition can lead to severe kidney failure and death.

Previously, there has been no easy method to predict progressive rhabdomyolysis. But researchers from Brigham and Women’s Hospital recently developed the Rhabdomyolysis Risk Calculator, a prediction score that can help determine whether a patient with rhabdomyolysis is at risk for severe kidney failure or death.

The researchers conducted a retrospective cohort study of 2,371 patients admitted between 2000 and 2011 and examined variables that may be associated with kidney failure and death.5 They identified independent predictors for these outcomes, including age; gender; initial levels of phosphate, calcium, creatinine, carbon dioxide, and creatine kinase; and etiology of rhabdomyolysis (myositis, exercise, statin use, or seizure).5

This tool can assist providers in developing a patient-specific treatment plan. However, further research is needed to validate the current variables, verify the risk prediction score in other populations, and examine its ability to guide individualized treatment plans.

The Rhabdomyolysis Risk Calculator is available at www.brighamandwomens.org/research/rhabdo/default.aspx

Kristy Washinger, MSN, CRNP

Nephrology Associates of Central PA

Camp Hill, PA

REFERENCES

1. Vos FE, Schollum JB, Walker RJ. Glycated albumin is the preferred marker for assessing glycaemic control in advanced chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant Plus. 2011; 4(6):368-375.

2. National Kidney Foundation Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative. Clinical practice guidelines and clinical practice recommendations for diabetes and chronic kidney disease. Guideline 2: management of hyperglycemia and general diabetes care in chronic kidney disease. www.kidney.org/professionals/kdoqi/guideline_diabetes/guide2.htm. Accessed April 15, 2014.

3. Sharif A, Baboolal K. Diagnostic application of the A1c assay in renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21(3):383-385.

4. American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes—2013. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(suppl 1):S11-S66.

5. McMahon GM, Zeng X, Walker SS. A risk prediction score for kidney failure or mortality in rhabdomyolysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(19):1821-1828.

Determining Renal Function: What Those Test Results Mean

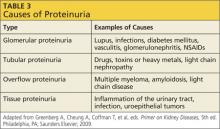

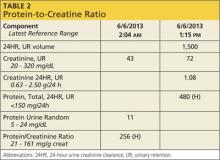

Q: Even though you suggested a random urine ACR (albumin-to-creatinine ratio), the internal medicine group ordered a 24-hour urine test for protein. As you can see from the results (see Table 2), the PCR (protein-to-creatinine ratio) is high. What does this mean? Does my patient have more severe kidney disease than I thought for her age?

Advanced age is a risk factor for CKD, and the patient has also had weight loss that can affect her serum creatinine. Because of her femur fracture, she has likely been in pain and probably has been taking nephrotoxic analgesics, such as NSAIDs or a ketorolac injection, commonly given postoperatively.

The patient’s weight does not appear to be stable, and she may have a degree of malnutrition. Both malnutrition and reduced muscle mass are known to decrease serum creatinine, which can mask worsening kidney disease. Thus she may have a lower true GFR than predicted by CG, which tends to overestimate renal function in the case of lower levels of creatinine production.6

Looking at all of these factors, it is likely that she has some degree of renal disease; however, it is important to determine if this is an acute change or a chronic issue. Looking closely at the higher-than-normal urinary protein result requires some out-of-the-box thinking.

Proteinuria has four types; each indicates a particular disorder.5 Table 3 provides examples of causative factors for each type.

Based on the data provided (Table 2), you have a high urinary protein result and are unsure if it is albumin. It is important to determine if this is albumin—and therefore pathognomonic for progressive kidney disease—or if the protein is of a nonalbumin type that will require further evaluation. What started as just an elderly female with a femur fracture and decreased GFR can turn into a diagnosis of multiple myeloma (which is more common in this age-group), kidney damage from postoperative medications, or another form of kidney disease. Only by looking at urinary protein type can one “tease out” what this might be.

In conclusion, there are many different ways to determine renal function, either by creatinine clearance or by using an estimation formula. Each one, used correctly, can offer advantages in certain populations. It is extremely important to determine whether an individual has diminished kidney function in order to be able to delay the progression of CKD.

Catherine B. York, MSN, APRN-BC

Springfield Nephrology

Associates, Springfield, MO

References

1. CDC. National chronic kidney disease fact sheet: general information and national estimates on chronic kidney disease in the United States, 2010. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2010.

2. US Renal Data System. USRDS 2012 annual data report: atlas of end-stage renal disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2012.

3. US Renal Data System. USRDS 2012 annual data report: atlas of end-stage renal disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2011.

4. Clarkson MR, Brenner BM. Clinical assessment of the patient with kidney disease. In: Clarkson MR, Brenner BM. Pocket Companion to Brenner & Rector’s The Kidney. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2005: 3-19.5.

5. Hsu C. Clinical evaluation of kidney function. In: Greenberg A, Cheung A, Coffman T, et al, eds. Primer on Kidney Diseases, 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA; Saunders Elsevier; 2009:19-237.

6. Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group. KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl. 2013;3:1-150.

7. National Kidney Foundation. Guideline 5: assessment of proteinuria. K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification; 2000.

8. Stevens LA, Coresh J, Greene T, et al. Assessing kidney function-measured and estimated glomerular filtration rate. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2473-2483.

Q: Even though you suggested a random urine ACR (albumin-to-creatinine ratio), the internal medicine group ordered a 24-hour urine test for protein. As you can see from the results (see Table 2), the PCR (protein-to-creatinine ratio) is high. What does this mean? Does my patient have more severe kidney disease than I thought for her age?

Advanced age is a risk factor for CKD, and the patient has also had weight loss that can affect her serum creatinine. Because of her femur fracture, she has likely been in pain and probably has been taking nephrotoxic analgesics, such as NSAIDs or a ketorolac injection, commonly given postoperatively.

The patient’s weight does not appear to be stable, and she may have a degree of malnutrition. Both malnutrition and reduced muscle mass are known to decrease serum creatinine, which can mask worsening kidney disease. Thus she may have a lower true GFR than predicted by CG, which tends to overestimate renal function in the case of lower levels of creatinine production.6

Looking at all of these factors, it is likely that she has some degree of renal disease; however, it is important to determine if this is an acute change or a chronic issue. Looking closely at the higher-than-normal urinary protein result requires some out-of-the-box thinking.

Proteinuria has four types; each indicates a particular disorder.5 Table 3 provides examples of causative factors for each type.

Based on the data provided (Table 2), you have a high urinary protein result and are unsure if it is albumin. It is important to determine if this is albumin—and therefore pathognomonic for progressive kidney disease—or if the protein is of a nonalbumin type that will require further evaluation. What started as just an elderly female with a femur fracture and decreased GFR can turn into a diagnosis of multiple myeloma (which is more common in this age-group), kidney damage from postoperative medications, or another form of kidney disease. Only by looking at urinary protein type can one “tease out” what this might be.

In conclusion, there are many different ways to determine renal function, either by creatinine clearance or by using an estimation formula. Each one, used correctly, can offer advantages in certain populations. It is extremely important to determine whether an individual has diminished kidney function in order to be able to delay the progression of CKD.

Catherine B. York, MSN, APRN-BC

Springfield Nephrology

Associates, Springfield, MO

References

1. CDC. National chronic kidney disease fact sheet: general information and national estimates on chronic kidney disease in the United States, 2010. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2010.

2. US Renal Data System. USRDS 2012 annual data report: atlas of end-stage renal disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2012.

3. US Renal Data System. USRDS 2012 annual data report: atlas of end-stage renal disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2011.

4. Clarkson MR, Brenner BM. Clinical assessment of the patient with kidney disease. In: Clarkson MR, Brenner BM. Pocket Companion to Brenner & Rector’s The Kidney. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2005: 3-19.5.

5. Hsu C. Clinical evaluation of kidney function. In: Greenberg A, Cheung A, Coffman T, et al, eds. Primer on Kidney Diseases, 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA; Saunders Elsevier; 2009:19-237.

6. Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group. KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl. 2013;3:1-150.

7. National Kidney Foundation. Guideline 5: assessment of proteinuria. K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification; 2000.

8. Stevens LA, Coresh J, Greene T, et al. Assessing kidney function-measured and estimated glomerular filtration rate. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2473-2483.

Q: Even though you suggested a random urine ACR (albumin-to-creatinine ratio), the internal medicine group ordered a 24-hour urine test for protein. As you can see from the results (see Table 2), the PCR (protein-to-creatinine ratio) is high. What does this mean? Does my patient have more severe kidney disease than I thought for her age?

Advanced age is a risk factor for CKD, and the patient has also had weight loss that can affect her serum creatinine. Because of her femur fracture, she has likely been in pain and probably has been taking nephrotoxic analgesics, such as NSAIDs or a ketorolac injection, commonly given postoperatively.

The patient’s weight does not appear to be stable, and she may have a degree of malnutrition. Both malnutrition and reduced muscle mass are known to decrease serum creatinine, which can mask worsening kidney disease. Thus she may have a lower true GFR than predicted by CG, which tends to overestimate renal function in the case of lower levels of creatinine production.6

Looking at all of these factors, it is likely that she has some degree of renal disease; however, it is important to determine if this is an acute change or a chronic issue. Looking closely at the higher-than-normal urinary protein result requires some out-of-the-box thinking.

Proteinuria has four types; each indicates a particular disorder.5 Table 3 provides examples of causative factors for each type.

Based on the data provided (Table 2), you have a high urinary protein result and are unsure if it is albumin. It is important to determine if this is albumin—and therefore pathognomonic for progressive kidney disease—or if the protein is of a nonalbumin type that will require further evaluation. What started as just an elderly female with a femur fracture and decreased GFR can turn into a diagnosis of multiple myeloma (which is more common in this age-group), kidney damage from postoperative medications, or another form of kidney disease. Only by looking at urinary protein type can one “tease out” what this might be.

In conclusion, there are many different ways to determine renal function, either by creatinine clearance or by using an estimation formula. Each one, used correctly, can offer advantages in certain populations. It is extremely important to determine whether an individual has diminished kidney function in order to be able to delay the progression of CKD.

Catherine B. York, MSN, APRN-BC

Springfield Nephrology

Associates, Springfield, MO

References

1. CDC. National chronic kidney disease fact sheet: general information and national estimates on chronic kidney disease in the United States, 2010. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2010.

2. US Renal Data System. USRDS 2012 annual data report: atlas of end-stage renal disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2012.

3. US Renal Data System. USRDS 2012 annual data report: atlas of end-stage renal disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2011.

4. Clarkson MR, Brenner BM. Clinical assessment of the patient with kidney disease. In: Clarkson MR, Brenner BM. Pocket Companion to Brenner & Rector’s The Kidney. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2005: 3-19.5.

5. Hsu C. Clinical evaluation of kidney function. In: Greenberg A, Cheung A, Coffman T, et al, eds. Primer on Kidney Diseases, 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA; Saunders Elsevier; 2009:19-237.

6. Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group. KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl. 2013;3:1-150.

7. National Kidney Foundation. Guideline 5: assessment of proteinuria. K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification; 2000.

8. Stevens LA, Coresh J, Greene T, et al. Assessing kidney function-measured and estimated glomerular filtration rate. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2473-2483.

Determining Renal Function: What’s the Best Way to Evaluate?

Q: One of my patients is a 72-year-old woman who weighs 59 kg. Her creatinine clearance by Cockcroft-Gault (CG) came back low (49 mL/min). Is this due to her age, gender, and weight loss during the past five months (subsequent to a femur fracture), or does she have underlying kidney disease? Would a 24-hour urine creatinine test be the best way to determine her level of kidney function—and would it be appropriate for someone her age? Is there a better way to evaluate her kidney function?

Accurate measurement of renal function is vital for any patient suspected of having chronic kidney disease (CKD). More than 20 million adults in the United States, or more than 10% of the adult population, have CKD.1 The 2012 US Renal Data System (USRDS) Annual Data Report states that the prevalence of chronic kidney disease in the Medicare population alone rose more than three-fold between 2000 and 2010, from 2.7% to 9.2%.2

CKD consumes a large proportion of Medicare dollars: more than $23,000 per person per year (PPPY) annually. For end-stage renal disease (ESRD) patients on hemodialysis, the cost is an astounding $88,000 PPPY.2 The cost of treating 871,000 ESRD patients was more than $40 billion in both public and private funds in 2009.3

Risk factors for CKD include but are not limited to: advancing age, male sex, race, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, smoking, family history of kidney disease, proteinuria, exposure to nephrotoxins, and atherosclerosis.4

In the US, the most common methods used to estimate renal function are the CG (Cockcroft-Gault) equation, Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) study equations, and the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation. It is often difficult to determine which test is best suited for a patient, because there are pros and cons to each formula and no one test is perfectly suited for every clinical application.4

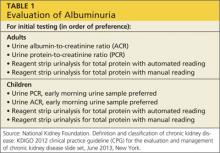

Since we know this patient’s renal function is low via CG (49 mL/min), the next important question to ask is, “Is it progressive?” I would recommend obtaining a urinalysis to look for hematuria and albuminuria. Proteinuria is an all-encompassing term. Albumin is only one type of protein and is the single most predictive risk factor for kidney disease progression. Persistent albuminuria alone is diagnostic of renal disease.5 The recommended test is a random urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR; see Table 1).6

You asked if a 24-hour urine creatinine clearance might evaluate her renal function better. Creatinine clearance can be determined by a 24-hour urine test and a serum blood sample in a steady state. However, this test should be interpreted with caution due to both collection errors and the fact that creatinine clearance overestimates true glomerular filtration rate (GFR) due to tubular secretion of creatinine.7,8 Thus, this test is no longer routinely recommended to determine kidney function.8

Catherine B. York, MSN, APRN-BC

Springfield Nephrology

Associates, Springfield, MO

References

1. CDC. National chronic kidney disease fact sheet: general information and national estimates on chronic kidney disease in the United States, 2010. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2010.

2. US Renal Data System. USRDS 2012 annual data report: atlas of end-stage renal disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2012.

3. US Renal Data System. USRDS 2012 annual data report: atlas of end-stage renal disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2011.

4. Clarkson MR, Brenner BM. Clinical assessment of the patient with kidney disease. In: Clarkson MR, Brenner BM. Pocket Companion to Brenner & Rector’s The Kidney. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2005: 3-19.5.

5. Hsu C. Clinical evaluation of kidney function. In: Greenberg A, Cheung A, Coffman T, et al, eds. Primer on Kidney Diseases, 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA; Saunders Elsevier; 2009:19-237.

6. Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group. KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl. 2013;3:1-150.

7. National Kidney Foundation. Guideline 5: assessment of proteinuria. K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification; 2000.

8. Stevens LA, Coresh J, Greene T, et al. Assessing kidney function-measured and estimated glomerular filtration rate. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2473-2483.

Q: One of my patients is a 72-year-old woman who weighs 59 kg. Her creatinine clearance by Cockcroft-Gault (CG) came back low (49 mL/min). Is this due to her age, gender, and weight loss during the past five months (subsequent to a femur fracture), or does she have underlying kidney disease? Would a 24-hour urine creatinine test be the best way to determine her level of kidney function—and would it be appropriate for someone her age? Is there a better way to evaluate her kidney function?

Accurate measurement of renal function is vital for any patient suspected of having chronic kidney disease (CKD). More than 20 million adults in the United States, or more than 10% of the adult population, have CKD.1 The 2012 US Renal Data System (USRDS) Annual Data Report states that the prevalence of chronic kidney disease in the Medicare population alone rose more than three-fold between 2000 and 2010, from 2.7% to 9.2%.2

CKD consumes a large proportion of Medicare dollars: more than $23,000 per person per year (PPPY) annually. For end-stage renal disease (ESRD) patients on hemodialysis, the cost is an astounding $88,000 PPPY.2 The cost of treating 871,000 ESRD patients was more than $40 billion in both public and private funds in 2009.3

Risk factors for CKD include but are not limited to: advancing age, male sex, race, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, smoking, family history of kidney disease, proteinuria, exposure to nephrotoxins, and atherosclerosis.4

In the US, the most common methods used to estimate renal function are the CG (Cockcroft-Gault) equation, Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) study equations, and the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation. It is often difficult to determine which test is best suited for a patient, because there are pros and cons to each formula and no one test is perfectly suited for every clinical application.4

Since we know this patient’s renal function is low via CG (49 mL/min), the next important question to ask is, “Is it progressive?” I would recommend obtaining a urinalysis to look for hematuria and albuminuria. Proteinuria is an all-encompassing term. Albumin is only one type of protein and is the single most predictive risk factor for kidney disease progression. Persistent albuminuria alone is diagnostic of renal disease.5 The recommended test is a random urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR; see Table 1).6

You asked if a 24-hour urine creatinine clearance might evaluate her renal function better. Creatinine clearance can be determined by a 24-hour urine test and a serum blood sample in a steady state. However, this test should be interpreted with caution due to both collection errors and the fact that creatinine clearance overestimates true glomerular filtration rate (GFR) due to tubular secretion of creatinine.7,8 Thus, this test is no longer routinely recommended to determine kidney function.8

Catherine B. York, MSN, APRN-BC

Springfield Nephrology

Associates, Springfield, MO

References

1. CDC. National chronic kidney disease fact sheet: general information and national estimates on chronic kidney disease in the United States, 2010. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2010.

2. US Renal Data System. USRDS 2012 annual data report: atlas of end-stage renal disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2012.

3. US Renal Data System. USRDS 2012 annual data report: atlas of end-stage renal disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2011.

4. Clarkson MR, Brenner BM. Clinical assessment of the patient with kidney disease. In: Clarkson MR, Brenner BM. Pocket Companion to Brenner & Rector’s The Kidney. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2005: 3-19.5.

5. Hsu C. Clinical evaluation of kidney function. In: Greenberg A, Cheung A, Coffman T, et al, eds. Primer on Kidney Diseases, 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA; Saunders Elsevier; 2009:19-237.

6. Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group. KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl. 2013;3:1-150.

7. National Kidney Foundation. Guideline 5: assessment of proteinuria. K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification; 2000.

8. Stevens LA, Coresh J, Greene T, et al. Assessing kidney function-measured and estimated glomerular filtration rate. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2473-2483.

Q: One of my patients is a 72-year-old woman who weighs 59 kg. Her creatinine clearance by Cockcroft-Gault (CG) came back low (49 mL/min). Is this due to her age, gender, and weight loss during the past five months (subsequent to a femur fracture), or does she have underlying kidney disease? Would a 24-hour urine creatinine test be the best way to determine her level of kidney function—and would it be appropriate for someone her age? Is there a better way to evaluate her kidney function?

Accurate measurement of renal function is vital for any patient suspected of having chronic kidney disease (CKD). More than 20 million adults in the United States, or more than 10% of the adult population, have CKD.1 The 2012 US Renal Data System (USRDS) Annual Data Report states that the prevalence of chronic kidney disease in the Medicare population alone rose more than three-fold between 2000 and 2010, from 2.7% to 9.2%.2

CKD consumes a large proportion of Medicare dollars: more than $23,000 per person per year (PPPY) annually. For end-stage renal disease (ESRD) patients on hemodialysis, the cost is an astounding $88,000 PPPY.2 The cost of treating 871,000 ESRD patients was more than $40 billion in both public and private funds in 2009.3

Risk factors for CKD include but are not limited to: advancing age, male sex, race, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, smoking, family history of kidney disease, proteinuria, exposure to nephrotoxins, and atherosclerosis.4

In the US, the most common methods used to estimate renal function are the CG (Cockcroft-Gault) equation, Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) study equations, and the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation. It is often difficult to determine which test is best suited for a patient, because there are pros and cons to each formula and no one test is perfectly suited for every clinical application.4

Since we know this patient’s renal function is low via CG (49 mL/min), the next important question to ask is, “Is it progressive?” I would recommend obtaining a urinalysis to look for hematuria and albuminuria. Proteinuria is an all-encompassing term. Albumin is only one type of protein and is the single most predictive risk factor for kidney disease progression. Persistent albuminuria alone is diagnostic of renal disease.5 The recommended test is a random urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR; see Table 1).6

You asked if a 24-hour urine creatinine clearance might evaluate her renal function better. Creatinine clearance can be determined by a 24-hour urine test and a serum blood sample in a steady state. However, this test should be interpreted with caution due to both collection errors and the fact that creatinine clearance overestimates true glomerular filtration rate (GFR) due to tubular secretion of creatinine.7,8 Thus, this test is no longer routinely recommended to determine kidney function.8

Catherine B. York, MSN, APRN-BC

Springfield Nephrology

Associates, Springfield, MO

References

1. CDC. National chronic kidney disease fact sheet: general information and national estimates on chronic kidney disease in the United States, 2010. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2010.

2. US Renal Data System. USRDS 2012 annual data report: atlas of end-stage renal disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2012.

3. US Renal Data System. USRDS 2012 annual data report: atlas of end-stage renal disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2011.

4. Clarkson MR, Brenner BM. Clinical assessment of the patient with kidney disease. In: Clarkson MR, Brenner BM. Pocket Companion to Brenner & Rector’s The Kidney. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2005: 3-19.5.

5. Hsu C. Clinical evaluation of kidney function. In: Greenberg A, Cheung A, Coffman T, et al, eds. Primer on Kidney Diseases, 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA; Saunders Elsevier; 2009:19-237.

6. Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group. KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl. 2013;3:1-150.

7. National Kidney Foundation. Guideline 5: assessment of proteinuria. K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification; 2000.

8. Stevens LA, Coresh J, Greene T, et al. Assessing kidney function-measured and estimated glomerular filtration rate. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2473-2483.

Why Take This Patient Off Her ACEI?