User login

The Complex Problem of Women Trainees in Academic Medicine

Despite media attention to gender inequality in multiple professions, medicine has only recently begun to identify disparities facing women in academic medicine, focusing primarily on women faculty rather than trainees. Because of the unique and poorly understood juxtaposition of forces affecting their experience, focusing on women medical trainees may provide a representative framework to understand the larger, complex problem of gender equity in medicine. Rather than being a complicated problem with component parts that can be separately addressed, gender equity in medicine is a complex problem—one composed of a myriad of interrelated human and systemic factors. Such a complex problem demands innovative, open-minded, user-centered interventions. Here, we outline some of the factors unique to women trainees, including lack of female role models in leadership, gender bias, sexual harassment, work-life imbalance, and few formal leadership training programs. We propose one potential strategy, leadership programs specifically targeted to women residents and fellows. We recently implemented this strategy at our institution in the form of a day-long symposium of skill-building sessions for women residents and fellows.

Although women have achieved equal representation in several medical training programs, there is still a dearth of women in high-profile leadership positions within academic medicine. Although women comprised 46% of United States medical school applicants and residents in 2015-2016, underrepresentation persists at the level of associate professor (35% women), full professor (22%), department chair (14%), and dean (16%).1 Many potential women leaders may not self-identify as such due to the limited exposure to women role models in positions of power and may in fact be ready for leadership roles earlier but not apply until later in their careers as compared with men.2,3 The lack of role models with a shared background is an even more severe problem for women of color and all of these factors contribute to the “leaky pipeline” phenomenon.4 We aimed to address this mindset and help women see themselves as leaders by overcoming “second-generation gender bias” through our work.2

Due to the intense and inflexible nature of residency and fellowship training programs, many women choose to defer milestones such as childbearing.5 Women trainees are more likely than their male colleagues to avoid having a child during residency due to perceived threat to their career and negative perceptions of colleagues.5,6 Women who are in a domestic partnership often bear the brunt of the household work regardless of the careers of the two partners, a phenomenon termed the “second shift.”7 This work-life imbalance has been shown to correlate with depressive symptoms in women internal medicine trainees.8

Recently, a trainee published on the experience of medical residents being asked whether they were ever called “nurse.” All the women in the room put up their hands; none of their male colleagues did.9 At issue is not the relative importance of the professions of medicine and nursing, but rather the gender stereotypes in medicine that lead to automatic categorization of women into one group. Although the majority of women residents likely have had personal experiences with bias and microaggressions, few are explicitly taught the tools to address these. Beyond microaggressions, women trainees are also subject to more sexual harassment than their male colleagues.10 In addition, women living at the intersections of race, ethnicity, and gender are faced with even higher rates of harassment.11 Reporting sexual assault and harassment can be particularly difficult as a trainee because of the risk of retaliation, fear of poor evaluations from superiors, and lack of confidence in the reporting process.10

Finally, women trainees often receive little training about the skills required for career advancement to achieve parity with their male colleagues. Women are less likely to negotiate due to concerns about backlash or due to general lack of awareness about the importance of negotiation.12 Women are asked to volunteer for “nonpromotable” tasks more often than men by colleagues of both sexes, a barrier to women reaching their full career potential and a difficult workplace scenario to navigate.13 Unlike the fields of business, law, and technology, for example, women in medicine do not routinely have training courses that incorporate skills such as navigating difficult conversations, conflict resolution, curriculum vitae writing, and negotiation. Various solutions have been offered to address some of the barriers facing women in medicine (such as the Association of American Medical Colleges and Executive Leadership in Academic Medicine leadership courses), but typically these focus on faculty rather than trainees. Given that women physicians practicing in the inpatient setting have been shown to have better patient outcomes14 and organizations with female leadership outperform those led by men,15 equipping our women trainees to thrive in the clinical and leadership environments is an essential step in fulfilling our mission as high-quality training programs.

At our institution, we recognized the need for training in leadership skills for women medical trainees and designed a day-long symposium for internal medicine women residents and fellows. Before developing the curriculum, we conducted a needs assessment to ascertain which skills women wanted to develop; women overwhelmingly wanted to learn about public speaking skills, work-life integration, and mentoring. Based on these responses, a group spanning multiple levels of training (residency, fellowship, and faculty) designed a combination of large-group lectures and small-group workshops termed “Women in Leadership Development” (WILD). The day-long curriculum included sessions on public speaking skills, women as change agents, mentorship, conflict resolution, and addressing microaggressions and concluded with a networking event for women faculty and trainees (Table).

In total, 77 medicine residents and fellows voluntarily participated in the symposium in 2017 and 2018. The public speaking skills session received the highest reviews, with 98% of participants reporting that they identified ways to change public speaking styles to project confidence. This session was facilitated by an outside consultant in public speaking, highlighting the benefit of seeking experts outside of academic medicine. Another novel session focused on responding to microaggressions, defined as subtle and sometimes unintentional actions that express prejudice toward marginalized groups, in the clinical and academic environments. Microaggressions can undermine the recipient’s confidence, feeling of belonging, and effectiveness at work.16 At our institution, trainees in graduate medical education report the largest single source of microaggressions as patients (greater than attendings, fellow trainees, or staff), with gender bias being responsible for the greatest number of microaggressions (Schaeffer, unpublished data). Navigating these situations to ensure good patient care and strong patient-provider relationships, while also establishing a climate of mutual respect, can be challenging for all women physicians, in particular for trainees who are just beginning to experience the clinical environment independently. Our session on microaggressions was purposefully led by a national expert in patient-provider communication and offered an opportunity for women trainees to reflect on their past experiences being the target of microaggressions, to name them as such, and then to brainstorm possible responses as a group. The result was a “toolkit” of resources for responding to microaggressions.17

Of the attendees of WILD 2017 and 2018, 91% strongly agreed that participation in the symposium was a useful experience. One attendee reflected that they “feel more empowered to discuss women-related issues in academics with peers, mentors, mentees” and another stated that as a result of WILD, they would “sponsor peers and mentors, speak out more about gender bias, seek out leadership positions.” Challenges for our symposium included obtaining protected curricular time from busy trainee schedules. Supportive leadership at all levels was critical to our success; carving out dedicated curricular time will be essential for the sustainability of this leadership symposium. Our group has recently received funding to expand to a longitudinal course open to all women residents and fellows across graduate medical education.

Although the complex and unique problems facing women medical trainees are unlikely to be comprehensively addressed by a leadership course, we urge other institutions to adopt and expand on our model for teaching vital leadership skills. In addition to leadership skills, academic medical centers should adopt a multipronged approach to support their female trainees, including clear and confidential reporting practices of sexual harassment without fear of retaliation, training for all staff on harassment and bias, involvement of men as allies, and mentorship programs for women trainees. Further research is needed to better understand this complex problem, its impact on career outcomes, and a path to achieving gender equality in medicine.

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to Catherine Lucey, MD, for her framing of the issues for women in medicine as a complex problem and to Sarah Schaeffer, MD, for her unpublished data on microaggressions at our institution. The authors are also grateful to the UCSF Department of Medicine and the UCSF Chancellor’s Advisory Committee on the Status of Women for their financial support of the WILD (Women In Leadership Development) program.

Disclosures

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

The authors report no external funding source for this study.

1. AAMC [website]. 2018. https://www.aamc.org/. Accessed May 5, 2018.

2. Ibarra H, Ely, Robin J, Kolb D. Women rising: the unseen barriers. Harvard Bus Rev. 2013;91(9):60-66.

3. Stevenson EJ, Orr E. We interviewed 57 female CEOs to find out how more women can get to the top. Harvard Bus Rev. 2017.

4. Mahoney MR, Wilson E, Odom KL, Flowers L, Adler SR. Minority faculty voices on diversity in academic medicine: perspectives from one school. Acad Med. 2008;83(8):781-786. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31817ec002. PubMed

5. Turner PL, Lumpkins K, Gabre J, Lin MJ, Liu X, Terrin M. Pregnancy among women surgeons: trends over time. Arch Surg. 2012;147(5):474-479. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2011.1693. PubMed

6. Willett LL, Wellons MF, Hartig JR, et al. Do women residents delay childbearing due to perceived career threats? Acad Med. 2010;85(4):640-646. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181d2cb5b. PubMed

7. Jolly S, Griffith KA, DeCastro R, Stewart A, Ubel P, Jagsi R. Gender differences in time spent on parenting and domestic responsibilities by high-achieving young physician-researchers. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(5):344-353. doi: 10.7326/M13-0974. PubMed

8. Guille C, Frank E, Zhao Z, et al. Work-family conflict and the sex difference in depression among training physicians. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(12):1766-1772. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.5138. PubMed

9. DeFilippis EM. Putting the “She” in doctor. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(3):323-324. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.8362. PubMed

10. Komaromy M, Bindman AB, Haber RJ, Sande MA. Sexual harassment in medical training. N Engl J Med. 1993;328(5):322-326. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199302043280507. PubMed

11. Corbie-Smith G, Frank E, Nickens HW, Elon L. Prevalences and correlates of ethnic harassment in the U.S. Women Physicians’ Health Study. Acad Med. 1999;74(6):695-701. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199906000-00018. PubMed

12. Amanatullah ET, Morris MW. Negotiating gender roles: gender differences in assertive negotiating are mediated by women’s fear of backlash and attenuated when negotiating on behalf of others. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2010;98(2):256-267. doi: 10.1037/a0017094. PubMed

13. Babcock L, Maria PR, Vesterlund L. Why women volunteer for tasks that don’t lead to promotions. Harvard Bus Rev. 2018.

14. Tsugawa Y, Jena AB, Figueroa JF, Orav EJ, Blumenthal DM, Jha AK. Comparison of hospital mortality and readmission rates for medicare patients treated by male vs female physicians. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(2):206-213. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.7875. PubMed

15. Landel M. Why gender balance can’t wait. Harvard Bus Rev. 2016.

16. Wolf TM, Randall HM, von Almen K, Tynes LL. Perceived mistreatment and attitude change by graduating medical students: a retrospective study. Med Educ. 1991;25(3):182-190. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1991.tb00050.x. PubMed

17. Wheeler DJ, Zapata J, Davis D, Chou C. Twelve tips for responding to microaggressions and overt discrimination: when the patient offends the learner. Med Teach. 2018:1-6. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2018.1506097. PubMed

Despite media attention to gender inequality in multiple professions, medicine has only recently begun to identify disparities facing women in academic medicine, focusing primarily on women faculty rather than trainees. Because of the unique and poorly understood juxtaposition of forces affecting their experience, focusing on women medical trainees may provide a representative framework to understand the larger, complex problem of gender equity in medicine. Rather than being a complicated problem with component parts that can be separately addressed, gender equity in medicine is a complex problem—one composed of a myriad of interrelated human and systemic factors. Such a complex problem demands innovative, open-minded, user-centered interventions. Here, we outline some of the factors unique to women trainees, including lack of female role models in leadership, gender bias, sexual harassment, work-life imbalance, and few formal leadership training programs. We propose one potential strategy, leadership programs specifically targeted to women residents and fellows. We recently implemented this strategy at our institution in the form of a day-long symposium of skill-building sessions for women residents and fellows.

Although women have achieved equal representation in several medical training programs, there is still a dearth of women in high-profile leadership positions within academic medicine. Although women comprised 46% of United States medical school applicants and residents in 2015-2016, underrepresentation persists at the level of associate professor (35% women), full professor (22%), department chair (14%), and dean (16%).1 Many potential women leaders may not self-identify as such due to the limited exposure to women role models in positions of power and may in fact be ready for leadership roles earlier but not apply until later in their careers as compared with men.2,3 The lack of role models with a shared background is an even more severe problem for women of color and all of these factors contribute to the “leaky pipeline” phenomenon.4 We aimed to address this mindset and help women see themselves as leaders by overcoming “second-generation gender bias” through our work.2

Due to the intense and inflexible nature of residency and fellowship training programs, many women choose to defer milestones such as childbearing.5 Women trainees are more likely than their male colleagues to avoid having a child during residency due to perceived threat to their career and negative perceptions of colleagues.5,6 Women who are in a domestic partnership often bear the brunt of the household work regardless of the careers of the two partners, a phenomenon termed the “second shift.”7 This work-life imbalance has been shown to correlate with depressive symptoms in women internal medicine trainees.8

Recently, a trainee published on the experience of medical residents being asked whether they were ever called “nurse.” All the women in the room put up their hands; none of their male colleagues did.9 At issue is not the relative importance of the professions of medicine and nursing, but rather the gender stereotypes in medicine that lead to automatic categorization of women into one group. Although the majority of women residents likely have had personal experiences with bias and microaggressions, few are explicitly taught the tools to address these. Beyond microaggressions, women trainees are also subject to more sexual harassment than their male colleagues.10 In addition, women living at the intersections of race, ethnicity, and gender are faced with even higher rates of harassment.11 Reporting sexual assault and harassment can be particularly difficult as a trainee because of the risk of retaliation, fear of poor evaluations from superiors, and lack of confidence in the reporting process.10

Finally, women trainees often receive little training about the skills required for career advancement to achieve parity with their male colleagues. Women are less likely to negotiate due to concerns about backlash or due to general lack of awareness about the importance of negotiation.12 Women are asked to volunteer for “nonpromotable” tasks more often than men by colleagues of both sexes, a barrier to women reaching their full career potential and a difficult workplace scenario to navigate.13 Unlike the fields of business, law, and technology, for example, women in medicine do not routinely have training courses that incorporate skills such as navigating difficult conversations, conflict resolution, curriculum vitae writing, and negotiation. Various solutions have been offered to address some of the barriers facing women in medicine (such as the Association of American Medical Colleges and Executive Leadership in Academic Medicine leadership courses), but typically these focus on faculty rather than trainees. Given that women physicians practicing in the inpatient setting have been shown to have better patient outcomes14 and organizations with female leadership outperform those led by men,15 equipping our women trainees to thrive in the clinical and leadership environments is an essential step in fulfilling our mission as high-quality training programs.

At our institution, we recognized the need for training in leadership skills for women medical trainees and designed a day-long symposium for internal medicine women residents and fellows. Before developing the curriculum, we conducted a needs assessment to ascertain which skills women wanted to develop; women overwhelmingly wanted to learn about public speaking skills, work-life integration, and mentoring. Based on these responses, a group spanning multiple levels of training (residency, fellowship, and faculty) designed a combination of large-group lectures and small-group workshops termed “Women in Leadership Development” (WILD). The day-long curriculum included sessions on public speaking skills, women as change agents, mentorship, conflict resolution, and addressing microaggressions and concluded with a networking event for women faculty and trainees (Table).

In total, 77 medicine residents and fellows voluntarily participated in the symposium in 2017 and 2018. The public speaking skills session received the highest reviews, with 98% of participants reporting that they identified ways to change public speaking styles to project confidence. This session was facilitated by an outside consultant in public speaking, highlighting the benefit of seeking experts outside of academic medicine. Another novel session focused on responding to microaggressions, defined as subtle and sometimes unintentional actions that express prejudice toward marginalized groups, in the clinical and academic environments. Microaggressions can undermine the recipient’s confidence, feeling of belonging, and effectiveness at work.16 At our institution, trainees in graduate medical education report the largest single source of microaggressions as patients (greater than attendings, fellow trainees, or staff), with gender bias being responsible for the greatest number of microaggressions (Schaeffer, unpublished data). Navigating these situations to ensure good patient care and strong patient-provider relationships, while also establishing a climate of mutual respect, can be challenging for all women physicians, in particular for trainees who are just beginning to experience the clinical environment independently. Our session on microaggressions was purposefully led by a national expert in patient-provider communication and offered an opportunity for women trainees to reflect on their past experiences being the target of microaggressions, to name them as such, and then to brainstorm possible responses as a group. The result was a “toolkit” of resources for responding to microaggressions.17

Of the attendees of WILD 2017 and 2018, 91% strongly agreed that participation in the symposium was a useful experience. One attendee reflected that they “feel more empowered to discuss women-related issues in academics with peers, mentors, mentees” and another stated that as a result of WILD, they would “sponsor peers and mentors, speak out more about gender bias, seek out leadership positions.” Challenges for our symposium included obtaining protected curricular time from busy trainee schedules. Supportive leadership at all levels was critical to our success; carving out dedicated curricular time will be essential for the sustainability of this leadership symposium. Our group has recently received funding to expand to a longitudinal course open to all women residents and fellows across graduate medical education.

Although the complex and unique problems facing women medical trainees are unlikely to be comprehensively addressed by a leadership course, we urge other institutions to adopt and expand on our model for teaching vital leadership skills. In addition to leadership skills, academic medical centers should adopt a multipronged approach to support their female trainees, including clear and confidential reporting practices of sexual harassment without fear of retaliation, training for all staff on harassment and bias, involvement of men as allies, and mentorship programs for women trainees. Further research is needed to better understand this complex problem, its impact on career outcomes, and a path to achieving gender equality in medicine.

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to Catherine Lucey, MD, for her framing of the issues for women in medicine as a complex problem and to Sarah Schaeffer, MD, for her unpublished data on microaggressions at our institution. The authors are also grateful to the UCSF Department of Medicine and the UCSF Chancellor’s Advisory Committee on the Status of Women for their financial support of the WILD (Women In Leadership Development) program.

Disclosures

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

The authors report no external funding source for this study.

Despite media attention to gender inequality in multiple professions, medicine has only recently begun to identify disparities facing women in academic medicine, focusing primarily on women faculty rather than trainees. Because of the unique and poorly understood juxtaposition of forces affecting their experience, focusing on women medical trainees may provide a representative framework to understand the larger, complex problem of gender equity in medicine. Rather than being a complicated problem with component parts that can be separately addressed, gender equity in medicine is a complex problem—one composed of a myriad of interrelated human and systemic factors. Such a complex problem demands innovative, open-minded, user-centered interventions. Here, we outline some of the factors unique to women trainees, including lack of female role models in leadership, gender bias, sexual harassment, work-life imbalance, and few formal leadership training programs. We propose one potential strategy, leadership programs specifically targeted to women residents and fellows. We recently implemented this strategy at our institution in the form of a day-long symposium of skill-building sessions for women residents and fellows.

Although women have achieved equal representation in several medical training programs, there is still a dearth of women in high-profile leadership positions within academic medicine. Although women comprised 46% of United States medical school applicants and residents in 2015-2016, underrepresentation persists at the level of associate professor (35% women), full professor (22%), department chair (14%), and dean (16%).1 Many potential women leaders may not self-identify as such due to the limited exposure to women role models in positions of power and may in fact be ready for leadership roles earlier but not apply until later in their careers as compared with men.2,3 The lack of role models with a shared background is an even more severe problem for women of color and all of these factors contribute to the “leaky pipeline” phenomenon.4 We aimed to address this mindset and help women see themselves as leaders by overcoming “second-generation gender bias” through our work.2

Due to the intense and inflexible nature of residency and fellowship training programs, many women choose to defer milestones such as childbearing.5 Women trainees are more likely than their male colleagues to avoid having a child during residency due to perceived threat to their career and negative perceptions of colleagues.5,6 Women who are in a domestic partnership often bear the brunt of the household work regardless of the careers of the two partners, a phenomenon termed the “second shift.”7 This work-life imbalance has been shown to correlate with depressive symptoms in women internal medicine trainees.8

Recently, a trainee published on the experience of medical residents being asked whether they were ever called “nurse.” All the women in the room put up their hands; none of their male colleagues did.9 At issue is not the relative importance of the professions of medicine and nursing, but rather the gender stereotypes in medicine that lead to automatic categorization of women into one group. Although the majority of women residents likely have had personal experiences with bias and microaggressions, few are explicitly taught the tools to address these. Beyond microaggressions, women trainees are also subject to more sexual harassment than their male colleagues.10 In addition, women living at the intersections of race, ethnicity, and gender are faced with even higher rates of harassment.11 Reporting sexual assault and harassment can be particularly difficult as a trainee because of the risk of retaliation, fear of poor evaluations from superiors, and lack of confidence in the reporting process.10

Finally, women trainees often receive little training about the skills required for career advancement to achieve parity with their male colleagues. Women are less likely to negotiate due to concerns about backlash or due to general lack of awareness about the importance of negotiation.12 Women are asked to volunteer for “nonpromotable” tasks more often than men by colleagues of both sexes, a barrier to women reaching their full career potential and a difficult workplace scenario to navigate.13 Unlike the fields of business, law, and technology, for example, women in medicine do not routinely have training courses that incorporate skills such as navigating difficult conversations, conflict resolution, curriculum vitae writing, and negotiation. Various solutions have been offered to address some of the barriers facing women in medicine (such as the Association of American Medical Colleges and Executive Leadership in Academic Medicine leadership courses), but typically these focus on faculty rather than trainees. Given that women physicians practicing in the inpatient setting have been shown to have better patient outcomes14 and organizations with female leadership outperform those led by men,15 equipping our women trainees to thrive in the clinical and leadership environments is an essential step in fulfilling our mission as high-quality training programs.

At our institution, we recognized the need for training in leadership skills for women medical trainees and designed a day-long symposium for internal medicine women residents and fellows. Before developing the curriculum, we conducted a needs assessment to ascertain which skills women wanted to develop; women overwhelmingly wanted to learn about public speaking skills, work-life integration, and mentoring. Based on these responses, a group spanning multiple levels of training (residency, fellowship, and faculty) designed a combination of large-group lectures and small-group workshops termed “Women in Leadership Development” (WILD). The day-long curriculum included sessions on public speaking skills, women as change agents, mentorship, conflict resolution, and addressing microaggressions and concluded with a networking event for women faculty and trainees (Table).

In total, 77 medicine residents and fellows voluntarily participated in the symposium in 2017 and 2018. The public speaking skills session received the highest reviews, with 98% of participants reporting that they identified ways to change public speaking styles to project confidence. This session was facilitated by an outside consultant in public speaking, highlighting the benefit of seeking experts outside of academic medicine. Another novel session focused on responding to microaggressions, defined as subtle and sometimes unintentional actions that express prejudice toward marginalized groups, in the clinical and academic environments. Microaggressions can undermine the recipient’s confidence, feeling of belonging, and effectiveness at work.16 At our institution, trainees in graduate medical education report the largest single source of microaggressions as patients (greater than attendings, fellow trainees, or staff), with gender bias being responsible for the greatest number of microaggressions (Schaeffer, unpublished data). Navigating these situations to ensure good patient care and strong patient-provider relationships, while also establishing a climate of mutual respect, can be challenging for all women physicians, in particular for trainees who are just beginning to experience the clinical environment independently. Our session on microaggressions was purposefully led by a national expert in patient-provider communication and offered an opportunity for women trainees to reflect on their past experiences being the target of microaggressions, to name them as such, and then to brainstorm possible responses as a group. The result was a “toolkit” of resources for responding to microaggressions.17

Of the attendees of WILD 2017 and 2018, 91% strongly agreed that participation in the symposium was a useful experience. One attendee reflected that they “feel more empowered to discuss women-related issues in academics with peers, mentors, mentees” and another stated that as a result of WILD, they would “sponsor peers and mentors, speak out more about gender bias, seek out leadership positions.” Challenges for our symposium included obtaining protected curricular time from busy trainee schedules. Supportive leadership at all levels was critical to our success; carving out dedicated curricular time will be essential for the sustainability of this leadership symposium. Our group has recently received funding to expand to a longitudinal course open to all women residents and fellows across graduate medical education.

Although the complex and unique problems facing women medical trainees are unlikely to be comprehensively addressed by a leadership course, we urge other institutions to adopt and expand on our model for teaching vital leadership skills. In addition to leadership skills, academic medical centers should adopt a multipronged approach to support their female trainees, including clear and confidential reporting practices of sexual harassment without fear of retaliation, training for all staff on harassment and bias, involvement of men as allies, and mentorship programs for women trainees. Further research is needed to better understand this complex problem, its impact on career outcomes, and a path to achieving gender equality in medicine.

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to Catherine Lucey, MD, for her framing of the issues for women in medicine as a complex problem and to Sarah Schaeffer, MD, for her unpublished data on microaggressions at our institution. The authors are also grateful to the UCSF Department of Medicine and the UCSF Chancellor’s Advisory Committee on the Status of Women for their financial support of the WILD (Women In Leadership Development) program.

Disclosures

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

The authors report no external funding source for this study.

1. AAMC [website]. 2018. https://www.aamc.org/. Accessed May 5, 2018.

2. Ibarra H, Ely, Robin J, Kolb D. Women rising: the unseen barriers. Harvard Bus Rev. 2013;91(9):60-66.

3. Stevenson EJ, Orr E. We interviewed 57 female CEOs to find out how more women can get to the top. Harvard Bus Rev. 2017.

4. Mahoney MR, Wilson E, Odom KL, Flowers L, Adler SR. Minority faculty voices on diversity in academic medicine: perspectives from one school. Acad Med. 2008;83(8):781-786. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31817ec002. PubMed

5. Turner PL, Lumpkins K, Gabre J, Lin MJ, Liu X, Terrin M. Pregnancy among women surgeons: trends over time. Arch Surg. 2012;147(5):474-479. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2011.1693. PubMed

6. Willett LL, Wellons MF, Hartig JR, et al. Do women residents delay childbearing due to perceived career threats? Acad Med. 2010;85(4):640-646. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181d2cb5b. PubMed

7. Jolly S, Griffith KA, DeCastro R, Stewart A, Ubel P, Jagsi R. Gender differences in time spent on parenting and domestic responsibilities by high-achieving young physician-researchers. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(5):344-353. doi: 10.7326/M13-0974. PubMed

8. Guille C, Frank E, Zhao Z, et al. Work-family conflict and the sex difference in depression among training physicians. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(12):1766-1772. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.5138. PubMed

9. DeFilippis EM. Putting the “She” in doctor. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(3):323-324. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.8362. PubMed

10. Komaromy M, Bindman AB, Haber RJ, Sande MA. Sexual harassment in medical training. N Engl J Med. 1993;328(5):322-326. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199302043280507. PubMed

11. Corbie-Smith G, Frank E, Nickens HW, Elon L. Prevalences and correlates of ethnic harassment in the U.S. Women Physicians’ Health Study. Acad Med. 1999;74(6):695-701. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199906000-00018. PubMed

12. Amanatullah ET, Morris MW. Negotiating gender roles: gender differences in assertive negotiating are mediated by women’s fear of backlash and attenuated when negotiating on behalf of others. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2010;98(2):256-267. doi: 10.1037/a0017094. PubMed

13. Babcock L, Maria PR, Vesterlund L. Why women volunteer for tasks that don’t lead to promotions. Harvard Bus Rev. 2018.

14. Tsugawa Y, Jena AB, Figueroa JF, Orav EJ, Blumenthal DM, Jha AK. Comparison of hospital mortality and readmission rates for medicare patients treated by male vs female physicians. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(2):206-213. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.7875. PubMed

15. Landel M. Why gender balance can’t wait. Harvard Bus Rev. 2016.

16. Wolf TM, Randall HM, von Almen K, Tynes LL. Perceived mistreatment and attitude change by graduating medical students: a retrospective study. Med Educ. 1991;25(3):182-190. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1991.tb00050.x. PubMed

17. Wheeler DJ, Zapata J, Davis D, Chou C. Twelve tips for responding to microaggressions and overt discrimination: when the patient offends the learner. Med Teach. 2018:1-6. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2018.1506097. PubMed

1. AAMC [website]. 2018. https://www.aamc.org/. Accessed May 5, 2018.

2. Ibarra H, Ely, Robin J, Kolb D. Women rising: the unseen barriers. Harvard Bus Rev. 2013;91(9):60-66.

3. Stevenson EJ, Orr E. We interviewed 57 female CEOs to find out how more women can get to the top. Harvard Bus Rev. 2017.

4. Mahoney MR, Wilson E, Odom KL, Flowers L, Adler SR. Minority faculty voices on diversity in academic medicine: perspectives from one school. Acad Med. 2008;83(8):781-786. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31817ec002. PubMed

5. Turner PL, Lumpkins K, Gabre J, Lin MJ, Liu X, Terrin M. Pregnancy among women surgeons: trends over time. Arch Surg. 2012;147(5):474-479. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2011.1693. PubMed

6. Willett LL, Wellons MF, Hartig JR, et al. Do women residents delay childbearing due to perceived career threats? Acad Med. 2010;85(4):640-646. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181d2cb5b. PubMed

7. Jolly S, Griffith KA, DeCastro R, Stewart A, Ubel P, Jagsi R. Gender differences in time spent on parenting and domestic responsibilities by high-achieving young physician-researchers. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(5):344-353. doi: 10.7326/M13-0974. PubMed

8. Guille C, Frank E, Zhao Z, et al. Work-family conflict and the sex difference in depression among training physicians. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(12):1766-1772. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.5138. PubMed

9. DeFilippis EM. Putting the “She” in doctor. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(3):323-324. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.8362. PubMed

10. Komaromy M, Bindman AB, Haber RJ, Sande MA. Sexual harassment in medical training. N Engl J Med. 1993;328(5):322-326. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199302043280507. PubMed

11. Corbie-Smith G, Frank E, Nickens HW, Elon L. Prevalences and correlates of ethnic harassment in the U.S. Women Physicians’ Health Study. Acad Med. 1999;74(6):695-701. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199906000-00018. PubMed

12. Amanatullah ET, Morris MW. Negotiating gender roles: gender differences in assertive negotiating are mediated by women’s fear of backlash and attenuated when negotiating on behalf of others. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2010;98(2):256-267. doi: 10.1037/a0017094. PubMed

13. Babcock L, Maria PR, Vesterlund L. Why women volunteer for tasks that don’t lead to promotions. Harvard Bus Rev. 2018.

14. Tsugawa Y, Jena AB, Figueroa JF, Orav EJ, Blumenthal DM, Jha AK. Comparison of hospital mortality and readmission rates for medicare patients treated by male vs female physicians. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(2):206-213. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.7875. PubMed

15. Landel M. Why gender balance can’t wait. Harvard Bus Rev. 2016.

16. Wolf TM, Randall HM, von Almen K, Tynes LL. Perceived mistreatment and attitude change by graduating medical students: a retrospective study. Med Educ. 1991;25(3):182-190. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1991.tb00050.x. PubMed

17. Wheeler DJ, Zapata J, Davis D, Chou C. Twelve tips for responding to microaggressions and overt discrimination: when the patient offends the learner. Med Teach. 2018:1-6. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2018.1506097. PubMed

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine

We May Not “Have It All,” But We Can Make It Better through Structural Changes

In this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, the paper by Gottenborg et al. captures the experiences of female academic hospitalists navigating one of the most significant transitions they will face—becoming new mothers.1 This article gives an accessible voice to impersonal statistics about the barriers women physicians encounter within and across specialties in academia. The challenges and anecdotes shared by the study participants were eminently relatable and captured the all-too-familiar circumstances most of us with children have faced in our careers as physician mothers.

STUDY COMMENTARY AND DISCUSSION

This study uses qualitative research methods to illustrate the hurdles faced by mothers in hospital medicine beyond what is demonstrated by quantitative measures and provides the helpful step of proposing some solutions to the obstacles they have faced. While the sample size was very small, the women interviewed were diverse in their years in practice, geographic distribution, and percent clinical effort, providing evidence that the themes discussed prevail across demographic categories.

The snowball sampling via the Society of Hospital Medicine committees may not have yielded a representative sample of female hospitalists. It seems possible that women who are involved in this type of leadership may be better supported and/or have different work schedules than their peers who are not in leadership positions. We also wish there had been more emphasis on the systemic and structural factors that can improve the quality of life of physician mothers. These policies include paternity leave and other creative ways of acknowledging the useful skills and experience that motherhood brings to bear on clinical practice, such as increased empathy and compassion, as mentioned by one of the study participants.

Even with the aforementioned limitations, this study is important because it combines authentic quotes from practicing academic hospitalists with concrete and tangible suggestions for structural changes. The most striking element is that the majority of the study participants experienced uncertainty and a lack of transparency around parental leave policies. As nearly half of hospitalists are women and 80% are under age 40,2 it seems unimaginable that there would not be explicit policies in place for what is a common and largely anticipated life event. Medicine has made great strides toward gender equality, but we are unlikely to ever reach the goal of true parity without openly addressing the disproportionate effect of childbearing and child rearing on women physicians. Standardized, readily available, and equitable parental leave policies (for both birth parents and nonbirth parents) are the first and most critical step.

The absence of standard leave policies naturally puts physician mothers in the position of having to negotiate or “haggle” with various supervisors, the majority of whom are male division chiefs and department chairs,3 which places all parties in an uncomfortable position, further reinforcing inequities and sowing discord and resentment. Having formal policies around leave protects not only those who utilize parental leave but also the other members of a hospital medicine practice who take on the workload of the person on leave.

Uncertainty around how to address the increased clinical load and for how long, also creates anxiety among other group members and may lead to feelings of bitterness toward clinicians on leave, further contributing to the negative impact of new parenthood on female hospitalists. We can think of no other medical circumstance in which there is as much advance notice of the need for significant time away from work. Yet pregnancy, which is subject to complications and emergencies just like other medical conditions, is treated with so little concern that one may be asked to arrange for their own coverage during such an emergency, as one study subject reported.

We also empathize with the study participants’ reports of feeling that supervisors often mentally discounted their ability to participate in projects on return to work. These pernicious assumptions can compound a cycle of lost productivity, disengagement, and attrition from the workforce.

Female hospitalists returning from leave face additional challenges that place an undue burden on their professional activities, most notably related to breastfeeding. This is particularly relevant in the context of the intensity inherent in practicing hospital medicine, which includes long days of being the primary provider for acutely ill inpatients, as well as long stretches of many consecutive days when it may not be possible to return home before children’s bedtime. Even at our own institution, which has been recognized as a “Healthy Mothers Workplace,” breastfeeding accommodations are not set up to allow for ongoing clinical activities while taking time to express breastmilk, and the clinical schedule does not build in adjustments for this time-consuming and psychologically taxing commitment. Breastfeeding for at least one year is the medical recommendation of the American Academy of Pediatrics in line with a substantial body of evidence.4 One quote from the article poignantly notes, “Pumping every 3-4 hours: stopping what you’re doing, finding an empty room to pump, finding a place to store your milk, then going back to work, three times per shift, for the next 9 months of your life, was hell.” If we cannot enable our own medical providers to follow evidence-based recommendations, how can we possibly expect this of our patients?

CONCLUSIONS

The notion of women “having it all” is an impossible ideal—both work and life outside of work will inevitably require tradeoffs. However, there is an abundance of evidence and recommendations for concrete steps that can be taken to improve the experience of female physicians who have children. These include formal policies for childbearing and child rearing leave (the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends at least six to nine months5), convenient space and protected time for pumping milk during the first year, on-site childcare services and back-up child care, and flexible work schedules.6 It is time to stop treating childbirth among female physicians like an unexpected inconvenience and acknowledge the undeniable demographics of physicians in hospital medicine and the duty of healthcare systems and hospital medicine leaders to effectively plan for the needs of half of their workforce.

Disclosures

Neither of the authors have any financial conflicts of interest to disclose.

1. Gottenborg E, Maw A, Ngov LK, Burden M, Ponomaryova A, Jones CD. You can’t have it all: The experience of academic hospitalists during pregnancy, parental leave, and return to work. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(12):836-839. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3076. PubMed

2. Reid MB, Misky GJ, Harrison RA, Sharpe B, Auerbach A, Glasheen JJ. Mentorship, productivity, and promotion among academic hospitalists. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(1):23-27. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1892-5. PubMed

3. Association of American Medical Colleges. The state of women in academic medicine: The pipeline and pathways to leadership, 2015-2016. https://www.aamc.org/members/gwims/statistics/. Accessed October 1, 2018.

4. American Academy of Pediatrics. Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics. 2012;129(3):e827-e841. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3552. PubMed

5. National Public Radio. A Pediatrician’s View of Paid Parental Leave. https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2016/10/10/497052014/a-pediatricians-view-of-paid-parental-leave. Accessed September 26, 2018.

6. Mangurian C, Linos E, Sarkar U, Rodriguez C, Jagsi R. What’s holding women in medicine back from leadership? (2018, June 19). Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2018/06/whats-holding-women-in-medicine-back-from-leadership. Accessed October 1, 2018.

In this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, the paper by Gottenborg et al. captures the experiences of female academic hospitalists navigating one of the most significant transitions they will face—becoming new mothers.1 This article gives an accessible voice to impersonal statistics about the barriers women physicians encounter within and across specialties in academia. The challenges and anecdotes shared by the study participants were eminently relatable and captured the all-too-familiar circumstances most of us with children have faced in our careers as physician mothers.

STUDY COMMENTARY AND DISCUSSION

This study uses qualitative research methods to illustrate the hurdles faced by mothers in hospital medicine beyond what is demonstrated by quantitative measures and provides the helpful step of proposing some solutions to the obstacles they have faced. While the sample size was very small, the women interviewed were diverse in their years in practice, geographic distribution, and percent clinical effort, providing evidence that the themes discussed prevail across demographic categories.

The snowball sampling via the Society of Hospital Medicine committees may not have yielded a representative sample of female hospitalists. It seems possible that women who are involved in this type of leadership may be better supported and/or have different work schedules than their peers who are not in leadership positions. We also wish there had been more emphasis on the systemic and structural factors that can improve the quality of life of physician mothers. These policies include paternity leave and other creative ways of acknowledging the useful skills and experience that motherhood brings to bear on clinical practice, such as increased empathy and compassion, as mentioned by one of the study participants.

Even with the aforementioned limitations, this study is important because it combines authentic quotes from practicing academic hospitalists with concrete and tangible suggestions for structural changes. The most striking element is that the majority of the study participants experienced uncertainty and a lack of transparency around parental leave policies. As nearly half of hospitalists are women and 80% are under age 40,2 it seems unimaginable that there would not be explicit policies in place for what is a common and largely anticipated life event. Medicine has made great strides toward gender equality, but we are unlikely to ever reach the goal of true parity without openly addressing the disproportionate effect of childbearing and child rearing on women physicians. Standardized, readily available, and equitable parental leave policies (for both birth parents and nonbirth parents) are the first and most critical step.

The absence of standard leave policies naturally puts physician mothers in the position of having to negotiate or “haggle” with various supervisors, the majority of whom are male division chiefs and department chairs,3 which places all parties in an uncomfortable position, further reinforcing inequities and sowing discord and resentment. Having formal policies around leave protects not only those who utilize parental leave but also the other members of a hospital medicine practice who take on the workload of the person on leave.

Uncertainty around how to address the increased clinical load and for how long, also creates anxiety among other group members and may lead to feelings of bitterness toward clinicians on leave, further contributing to the negative impact of new parenthood on female hospitalists. We can think of no other medical circumstance in which there is as much advance notice of the need for significant time away from work. Yet pregnancy, which is subject to complications and emergencies just like other medical conditions, is treated with so little concern that one may be asked to arrange for their own coverage during such an emergency, as one study subject reported.

We also empathize with the study participants’ reports of feeling that supervisors often mentally discounted their ability to participate in projects on return to work. These pernicious assumptions can compound a cycle of lost productivity, disengagement, and attrition from the workforce.

Female hospitalists returning from leave face additional challenges that place an undue burden on their professional activities, most notably related to breastfeeding. This is particularly relevant in the context of the intensity inherent in practicing hospital medicine, which includes long days of being the primary provider for acutely ill inpatients, as well as long stretches of many consecutive days when it may not be possible to return home before children’s bedtime. Even at our own institution, which has been recognized as a “Healthy Mothers Workplace,” breastfeeding accommodations are not set up to allow for ongoing clinical activities while taking time to express breastmilk, and the clinical schedule does not build in adjustments for this time-consuming and psychologically taxing commitment. Breastfeeding for at least one year is the medical recommendation of the American Academy of Pediatrics in line with a substantial body of evidence.4 One quote from the article poignantly notes, “Pumping every 3-4 hours: stopping what you’re doing, finding an empty room to pump, finding a place to store your milk, then going back to work, three times per shift, for the next 9 months of your life, was hell.” If we cannot enable our own medical providers to follow evidence-based recommendations, how can we possibly expect this of our patients?

CONCLUSIONS

The notion of women “having it all” is an impossible ideal—both work and life outside of work will inevitably require tradeoffs. However, there is an abundance of evidence and recommendations for concrete steps that can be taken to improve the experience of female physicians who have children. These include formal policies for childbearing and child rearing leave (the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends at least six to nine months5), convenient space and protected time for pumping milk during the first year, on-site childcare services and back-up child care, and flexible work schedules.6 It is time to stop treating childbirth among female physicians like an unexpected inconvenience and acknowledge the undeniable demographics of physicians in hospital medicine and the duty of healthcare systems and hospital medicine leaders to effectively plan for the needs of half of their workforce.

Disclosures

Neither of the authors have any financial conflicts of interest to disclose.

In this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, the paper by Gottenborg et al. captures the experiences of female academic hospitalists navigating one of the most significant transitions they will face—becoming new mothers.1 This article gives an accessible voice to impersonal statistics about the barriers women physicians encounter within and across specialties in academia. The challenges and anecdotes shared by the study participants were eminently relatable and captured the all-too-familiar circumstances most of us with children have faced in our careers as physician mothers.

STUDY COMMENTARY AND DISCUSSION

This study uses qualitative research methods to illustrate the hurdles faced by mothers in hospital medicine beyond what is demonstrated by quantitative measures and provides the helpful step of proposing some solutions to the obstacles they have faced. While the sample size was very small, the women interviewed were diverse in their years in practice, geographic distribution, and percent clinical effort, providing evidence that the themes discussed prevail across demographic categories.

The snowball sampling via the Society of Hospital Medicine committees may not have yielded a representative sample of female hospitalists. It seems possible that women who are involved in this type of leadership may be better supported and/or have different work schedules than their peers who are not in leadership positions. We also wish there had been more emphasis on the systemic and structural factors that can improve the quality of life of physician mothers. These policies include paternity leave and other creative ways of acknowledging the useful skills and experience that motherhood brings to bear on clinical practice, such as increased empathy and compassion, as mentioned by one of the study participants.

Even with the aforementioned limitations, this study is important because it combines authentic quotes from practicing academic hospitalists with concrete and tangible suggestions for structural changes. The most striking element is that the majority of the study participants experienced uncertainty and a lack of transparency around parental leave policies. As nearly half of hospitalists are women and 80% are under age 40,2 it seems unimaginable that there would not be explicit policies in place for what is a common and largely anticipated life event. Medicine has made great strides toward gender equality, but we are unlikely to ever reach the goal of true parity without openly addressing the disproportionate effect of childbearing and child rearing on women physicians. Standardized, readily available, and equitable parental leave policies (for both birth parents and nonbirth parents) are the first and most critical step.

The absence of standard leave policies naturally puts physician mothers in the position of having to negotiate or “haggle” with various supervisors, the majority of whom are male division chiefs and department chairs,3 which places all parties in an uncomfortable position, further reinforcing inequities and sowing discord and resentment. Having formal policies around leave protects not only those who utilize parental leave but also the other members of a hospital medicine practice who take on the workload of the person on leave.

Uncertainty around how to address the increased clinical load and for how long, also creates anxiety among other group members and may lead to feelings of bitterness toward clinicians on leave, further contributing to the negative impact of new parenthood on female hospitalists. We can think of no other medical circumstance in which there is as much advance notice of the need for significant time away from work. Yet pregnancy, which is subject to complications and emergencies just like other medical conditions, is treated with so little concern that one may be asked to arrange for their own coverage during such an emergency, as one study subject reported.

We also empathize with the study participants’ reports of feeling that supervisors often mentally discounted their ability to participate in projects on return to work. These pernicious assumptions can compound a cycle of lost productivity, disengagement, and attrition from the workforce.

Female hospitalists returning from leave face additional challenges that place an undue burden on their professional activities, most notably related to breastfeeding. This is particularly relevant in the context of the intensity inherent in practicing hospital medicine, which includes long days of being the primary provider for acutely ill inpatients, as well as long stretches of many consecutive days when it may not be possible to return home before children’s bedtime. Even at our own institution, which has been recognized as a “Healthy Mothers Workplace,” breastfeeding accommodations are not set up to allow for ongoing clinical activities while taking time to express breastmilk, and the clinical schedule does not build in adjustments for this time-consuming and psychologically taxing commitment. Breastfeeding for at least one year is the medical recommendation of the American Academy of Pediatrics in line with a substantial body of evidence.4 One quote from the article poignantly notes, “Pumping every 3-4 hours: stopping what you’re doing, finding an empty room to pump, finding a place to store your milk, then going back to work, three times per shift, for the next 9 months of your life, was hell.” If we cannot enable our own medical providers to follow evidence-based recommendations, how can we possibly expect this of our patients?

CONCLUSIONS

The notion of women “having it all” is an impossible ideal—both work and life outside of work will inevitably require tradeoffs. However, there is an abundance of evidence and recommendations for concrete steps that can be taken to improve the experience of female physicians who have children. These include formal policies for childbearing and child rearing leave (the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends at least six to nine months5), convenient space and protected time for pumping milk during the first year, on-site childcare services and back-up child care, and flexible work schedules.6 It is time to stop treating childbirth among female physicians like an unexpected inconvenience and acknowledge the undeniable demographics of physicians in hospital medicine and the duty of healthcare systems and hospital medicine leaders to effectively plan for the needs of half of their workforce.

Disclosures

Neither of the authors have any financial conflicts of interest to disclose.

1. Gottenborg E, Maw A, Ngov LK, Burden M, Ponomaryova A, Jones CD. You can’t have it all: The experience of academic hospitalists during pregnancy, parental leave, and return to work. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(12):836-839. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3076. PubMed

2. Reid MB, Misky GJ, Harrison RA, Sharpe B, Auerbach A, Glasheen JJ. Mentorship, productivity, and promotion among academic hospitalists. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(1):23-27. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1892-5. PubMed

3. Association of American Medical Colleges. The state of women in academic medicine: The pipeline and pathways to leadership, 2015-2016. https://www.aamc.org/members/gwims/statistics/. Accessed October 1, 2018.

4. American Academy of Pediatrics. Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics. 2012;129(3):e827-e841. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3552. PubMed

5. National Public Radio. A Pediatrician’s View of Paid Parental Leave. https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2016/10/10/497052014/a-pediatricians-view-of-paid-parental-leave. Accessed September 26, 2018.

6. Mangurian C, Linos E, Sarkar U, Rodriguez C, Jagsi R. What’s holding women in medicine back from leadership? (2018, June 19). Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2018/06/whats-holding-women-in-medicine-back-from-leadership. Accessed October 1, 2018.

1. Gottenborg E, Maw A, Ngov LK, Burden M, Ponomaryova A, Jones CD. You can’t have it all: The experience of academic hospitalists during pregnancy, parental leave, and return to work. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(12):836-839. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3076. PubMed

2. Reid MB, Misky GJ, Harrison RA, Sharpe B, Auerbach A, Glasheen JJ. Mentorship, productivity, and promotion among academic hospitalists. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(1):23-27. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1892-5. PubMed

3. Association of American Medical Colleges. The state of women in academic medicine: The pipeline and pathways to leadership, 2015-2016. https://www.aamc.org/members/gwims/statistics/. Accessed October 1, 2018.

4. American Academy of Pediatrics. Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics. 2012;129(3):e827-e841. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3552. PubMed

5. National Public Radio. A Pediatrician’s View of Paid Parental Leave. https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2016/10/10/497052014/a-pediatricians-view-of-paid-parental-leave. Accessed September 26, 2018.

6. Mangurian C, Linos E, Sarkar U, Rodriguez C, Jagsi R. What’s holding women in medicine back from leadership? (2018, June 19). Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2018/06/whats-holding-women-in-medicine-back-from-leadership. Accessed October 1, 2018.

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

Diving Into Diagnostic Uncertainty: Strategies to Mitigate Cognitive Load: In Reference to: “Focused Ethnography of Diagnosis in Academic Medical Centers”

We read the article by Chopra et al. “Focused Ethnography of Diagnosis in Academic Medical Centers” with great interest.1 This ethnographic study provided valuable insights into possible interventions to encourage diagnostic thinking.

Duty hour regulations and the resulting increase in handoffs have shifted the social experience of diagnosis from one that occurs within teams to one that often occurs between teams during handoffs between providers.2 While the article highlighted barriers to diagnosis, including distractions and time pressure, it did not explicitly discuss cognitive load theory. Cognitive load theory is an educational framework that has been described by Young et al.3 to improve instructions in the handoff process. These investigators showed how progressively experienced learners retain more information when using a structured scaffold or framework for information, such as the IPASS mnemonic,4 for example.

To mitigate the effects of distraction on the transfer of information, especially in cases with high diagnostic uncertainty, cognitive load must be explicitly considered. A structured framework for communication about diagnostic uncertainty informed by cognitive load theory would be a novel innovation that would help not only graduate medical education but could also improve diagnostic accuracy.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose

1. Chopra V, Harrod M, Winter S, et al. Focused Ethnography of Diagnosis in Academic Medical Centers. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(10):668-672. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2966. PubMed

2. Duong JA, Jensen TP, Morduchowicz, S, Mourad M, Harrison JD, Ranji SR. Exploring physician perspectives of residency holdover handoffs: a qualitative study to understand an increasingly important type of handoff. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(6):654-659. doi: 10.1007/s11606-017-4009-y PubMed

3. Young JQ, ten Cate O, O’Sullivan PS, Irby DM. Unpacking the complexity of patient handoffs through the lens of cognitive load theory. Teach Learn Med. 2016;28(1):88-96. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2015.1107491. PubMed

4. Starmer AJ, Spector ND, Srivastava R, et al. Changes in medical errors after implementation of a handoff program. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(19):1803-1812. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1414788. PubMed

We read the article by Chopra et al. “Focused Ethnography of Diagnosis in Academic Medical Centers” with great interest.1 This ethnographic study provided valuable insights into possible interventions to encourage diagnostic thinking.

Duty hour regulations and the resulting increase in handoffs have shifted the social experience of diagnosis from one that occurs within teams to one that often occurs between teams during handoffs between providers.2 While the article highlighted barriers to diagnosis, including distractions and time pressure, it did not explicitly discuss cognitive load theory. Cognitive load theory is an educational framework that has been described by Young et al.3 to improve instructions in the handoff process. These investigators showed how progressively experienced learners retain more information when using a structured scaffold or framework for information, such as the IPASS mnemonic,4 for example.

To mitigate the effects of distraction on the transfer of information, especially in cases with high diagnostic uncertainty, cognitive load must be explicitly considered. A structured framework for communication about diagnostic uncertainty informed by cognitive load theory would be a novel innovation that would help not only graduate medical education but could also improve diagnostic accuracy.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose

We read the article by Chopra et al. “Focused Ethnography of Diagnosis in Academic Medical Centers” with great interest.1 This ethnographic study provided valuable insights into possible interventions to encourage diagnostic thinking.

Duty hour regulations and the resulting increase in handoffs have shifted the social experience of diagnosis from one that occurs within teams to one that often occurs between teams during handoffs between providers.2 While the article highlighted barriers to diagnosis, including distractions and time pressure, it did not explicitly discuss cognitive load theory. Cognitive load theory is an educational framework that has been described by Young et al.3 to improve instructions in the handoff process. These investigators showed how progressively experienced learners retain more information when using a structured scaffold or framework for information, such as the IPASS mnemonic,4 for example.

To mitigate the effects of distraction on the transfer of information, especially in cases with high diagnostic uncertainty, cognitive load must be explicitly considered. A structured framework for communication about diagnostic uncertainty informed by cognitive load theory would be a novel innovation that would help not only graduate medical education but could also improve diagnostic accuracy.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose

1. Chopra V, Harrod M, Winter S, et al. Focused Ethnography of Diagnosis in Academic Medical Centers. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(10):668-672. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2966. PubMed

2. Duong JA, Jensen TP, Morduchowicz, S, Mourad M, Harrison JD, Ranji SR. Exploring physician perspectives of residency holdover handoffs: a qualitative study to understand an increasingly important type of handoff. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(6):654-659. doi: 10.1007/s11606-017-4009-y PubMed

3. Young JQ, ten Cate O, O’Sullivan PS, Irby DM. Unpacking the complexity of patient handoffs through the lens of cognitive load theory. Teach Learn Med. 2016;28(1):88-96. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2015.1107491. PubMed

4. Starmer AJ, Spector ND, Srivastava R, et al. Changes in medical errors after implementation of a handoff program. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(19):1803-1812. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1414788. PubMed

1. Chopra V, Harrod M, Winter S, et al. Focused Ethnography of Diagnosis in Academic Medical Centers. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(10):668-672. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2966. PubMed

2. Duong JA, Jensen TP, Morduchowicz, S, Mourad M, Harrison JD, Ranji SR. Exploring physician perspectives of residency holdover handoffs: a qualitative study to understand an increasingly important type of handoff. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(6):654-659. doi: 10.1007/s11606-017-4009-y PubMed

3. Young JQ, ten Cate O, O’Sullivan PS, Irby DM. Unpacking the complexity of patient handoffs through the lens of cognitive load theory. Teach Learn Med. 2016;28(1):88-96. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2015.1107491. PubMed

4. Starmer AJ, Spector ND, Srivastava R, et al. Changes in medical errors after implementation of a handoff program. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(19):1803-1812. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1414788. PubMed

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

Tissue Isn’t the Issue

A 43-year-old man with a history of asplenia, hepatitis C, and nephrolithiasis reported right-flank pain. He described severe, sharp pain that came in waves and radiated to the right groin, associated with nausea and nonbloody emesis. He noted “pink urine” but no dysuria. He had 4prior similar episodes during which he had passed kidney stones, although stone analysis had never been performed. He denied having fevers or chills.

The patient had been involved in a remote motor vehicle accident complicated by splenic laceration, for which he underwent splenectomy. He was appropriately immunized. The patient also suffered from bipolar affective disorder and untreated chronic hepatitis C infection with no evidence of cirrhosis. He smoked one pack of tobacco per day for the last 10 years and reported distant alcohol and methamphetamine use.

Right-flank pain can arise from conditions affecting the lower thorax (effusion, pneumonia, pulmonary embolism), abdomen (hepatobiliary or intestinal disease), retroperitoneum (hemorrhage or infection), musculoskeletal system, peripheral nerves (herpes zoster), or the genitourinary system (pyelonephritis). Pain radiating to the groin, discolored urine (suggesting hematuria), and history of kidney stones increase the likelihood of renal colic from nephrolithiasis.

Less commonly, flank pain and hematuria may present as initial symptoms of renal cell carcinoma, renal infarction, or aortic dissection. The patient’s immunosuppression from asplenia and active injection drug use could predispose him to septic emboli to his kidneys. Prior trauma causing aortic injury could predispose himto subsequent dissection.

The patient appeared well with a heart rate of 100 beats per minute, blood pressure 122/76 mmHg, temperature 36.8°C, respiratory rate 16 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation 96% on room air. His cardiopulmonary and abdominal examinations were normal, and he had no costovertebral angle tenderness. His skin was warm and dry without rashes. His white blood cell (WBC) count was 26,000/μL; absolute neutrophil count was 22,000/μL. Serum chemistries were normal, including creatinine 0.63 mg/dL, calcium 8.8 mg/dL, and phosphorus 3.1 mg/dL. Lactate was 0.8 mmol/L (reference range: 0-2.0 mmol/L). Urinalysis revealed large ketones, >50 red blood cells (RBC) per high power field (HPF), <5 WBC per HPF, 1+ calcium oxalate crystals and pH 6.0. A bedside ultrasound showed mild right hydronephrosis. Computed tomography (CT) with intravenous contrast of his abdomen and pelvis demonstrated diffuse, mildly prominent subcentimeter mesenteric lymphadenopathy and no kidney stones. He was treated with intravenous fluids and pain control, and was discharged with a presumptive diagnosis of a passed kidney stone.

A passed stone would not explain this degree of leukocytosis. The CT results reduce the likelihood of a renal neoplasm, renal infarction, or pyelonephritis. Mesenteric lymphadenopathy is nonspecific, but it may signal underlying infection or malignancy with spread to lymph nodes, or it may be part of a systemic disorder causing generalized lymphadenopathy. Malignant causes of mesenteric lymphadenopathy (with no apparent primary tumor) include testicular cancer, lymphoma, and primary urogenital neoplasms.

The lower extremity nodules are consistent with erythema nodosum, which may be observed in numerous infectious and noninfectious illnesses. The rapid tempo of this febrile illness mandates early consideration of infection. Splenectomized patients are at risk for overwhelming post-splenectomy infection from encapsulated organisms, although this risk is significantly mitigated with appropriate immunization. The patient is at risk of bacterial endocarditis, which could explain his fevers and polyarthritis, although plaques, pustules, and oral ulcers would be unusual. Disseminated gonococcal infection causes fevers, oral lesions, polyarthritis and pustular skin lesions, but plaques are uncommon. Disseminated mycobacterial and fungal infections may cause oral ulcers, but affected patients tend to be severely ill and have profound immunosuppression. Secondary syphilis may account for many of the findings; however, oral ulcers would be unusual, and the rash tends to be more widespread, with a predilection for the palms and soles. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) can cause oral ulcers and is the chief viral etiology to consider.

Noninfectious illnesses to consider include neoplasms and connective tissue diseases. Malignancy would be unlikely to manifest this abruptly or produce a paraneoplastic disorder with these features.

The patient described severe fatigue and drenching night sweats for two months prior to admission. He denied dyspnea or cough. He was born in the southwestern United States and had lived in California for almost a decade. He had been incarcerated for a few years and released three years prior. He had intermittently lived in homeless shelters, but currently lived alone in downtown San Francisco. He had traveled remotely to the Caribbean, and more recently traveled frequently to the Central Valley in California. The patient formerly worked as a pipe-fitter and welder. He denied animal exposure or recent sick contacts. He was sexually active with women, and intermittently used barrier protection.

His years in the southwestern United States may have exposed the patient to blastomycosis or histoplasmosis; both can mimic mycobacterial disease. Blastomycosis demonstrates a slightly stronger predilection for spreading to the bones, genitourinary tract, and central nervous system, whereas histoplasmosis is a more frequent cause of polyarthrtitis and mesenteric adenopathy. The patient’s travel to the Central Valley, California raises the possibility of coccidioidomycosis, which typically starts with pulmonary disease prior to dissemination to bones, skin, and other less common sites. Pipe-fitters are predisposed to asbestos-related illnesses, including lung cancer and mesothelioma, which would not explain this patient’s presentation. Incarceration and high-risk sexual practices increase his risk for tuberculosis, HIV, and syphilis. Widespread skin involvement is more characteristic of syphilis or primary HIV infection than of disseminated fungal or mycobacterial infection.

WBC measured 29,000/uL with a neutrophilic predominance. His peripheral blood smear was unremarkable. A comprehensive metabolic panel was normal. Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) was 317 U/L (reference range 140-280 U/L). Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was 39 mm/hr (reference range < 20 mm/hr) and C-reactive protein (CRP) was 66 mg/L (reference range <6.3 mg/L). Blood, urine, and throat cultures were sent. Chest radiograph showed clear lungs without adenopathy. Ankle and knee radiographs identified small effusions bilaterally without bony abnormalities. CT of his brain showed a small, hypodense lesion in the right lacrimal gland. A lumbar puncture with cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis showed absence of RBCs; WBC, 2/µL; protein, 35 mg/dL; glucose, 62 mg/dL; negative gram stain. CSF bacterial and fungal cultures, venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL), herpes simplex virus polymerase chain reaction (HSV PCR), and cryptococcal antigen were sent for laboratory analysis. The patient was started on vancomycin and aztreonam.

Lesions of the lacrimal gland feature multiple causes, including autoimmune diseases (Sjögren’s, Behçet’s disease), granulomatous diseases (sarcoidosis, granulomatosis with polyangiitis), neoplasms (salivary gland tumors, lymphoma), and infections. Initiating broad-spectrum antibiotics is reasonable while awaiting additional information from blood and urine cultures, serologies for HIV and syphilis, and purified protein derivative or interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA).

If these tests fail to reveal a diagnosis, the search for atypical infections and noninfectious possibilities should expand.

The patient continued to have intermittent fevers, sweats, and malaise over the next 3 days. All bacterial and fungal cultures remained negative, and antibiotics were discontinued. Rheumatoid factor, anticyclic citrullinated peptide, antinuclear antibody, and cryoglobulins were negative. Serum C3, C4, and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) levels were normal. A rapid plasma reagin (RPR), HIV antibody, IGRA, and serum antibodies for Coccidioides, histoplasmosis, and West Nile virus were negative. Urine nucleic acid amplification testing for gonorrhea and chlamydia was negative. CSF VDRL, HSV PCR and cryptococcal antigen were negative. HSV culture from an oral ulcer showed no growth. The patient had a reactive hepatitis C antibody with a viral load of 3 million virus equivalents/mL.

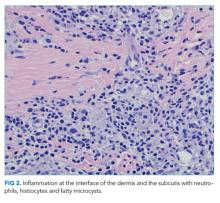

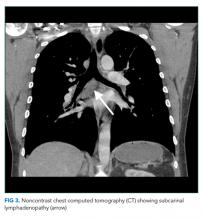

The additional test results lower