User login

Opioid Utilization and Perception of Pain Control in Hospitalized Patients: A Cross-Sectional Study of 11 Sites in 8 Countries

Since 2000, the United States has seen a marked increase in opioid prescribing1-3 and opioid-related complications, including overdoses, hospitalizations, and deaths.2,4,5 A study from 2015 showed that more than one-third of the US civilian noninstitutionalized population reported receiving an opioid prescription in the prior year, with 12.5% reporting misuse, and, of those, 16.7% reported a prescription use disorder.6 While there has been a slight decrease in opioid prescriptions in the US since 2012, rates of opioid prescribing in 2015 were three times higher than in 1999 and approximately four times higher than in Europe in 2015.3,7

Pain is commonly reported by hospitalized patients,8,9 and opioids are often a mainstay of treatment;9,10 however, treatment with opioids can have a number of adverse outcomes.2,10,11 Short-term exposure to opioids can lead to long-term use,12-16 and patients on opioids are at an increased risk for subsequent hospitalization and longer inpatient lengths of stay.5

Physician prescribing practices for opioids and patient expectations for pain control vary as a function of geographic region and culture,10,12,17,18 and pain is influenced by the cultural context in which it occurs.17,19-22 Treatment of pain may also be affected by limited access to or restrictions on selected medications, as well as by cultural biases.23 Whether these variations in the treatment of pain are reflected in patients’ satisfaction with pain control is uncertain.

We sought to compare the inpatient analgesic prescribing practices and patients’ perceptions of pain control for medical patients in four teaching hospitals in the US and in seven teaching hospitals in seven other countries.

METHODS

Study Design

We utilized a cross-sectional, observational design. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at all participating sites.

Setting

The study was conducted at 11 academic hospitals in eight countries from October 8, 2013 to August 31, 2015. Sites in the US included Denver Health in Denver, Colorado; the University of Colorado Hospital in Aurora, Colorado; Hennepin Healthcare in Minneapolis, Minnesota; and Legacy Health in Portland, Oregon. Sites outside the US included McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada; Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Universitat Autonòma de Barcelona in Barcelona, Spain; the University of Study of Milan and the University Ospedale “Luigi Sacco” in Milan, Italy, the National Taiwan University Hospital, in Taipei, Taiwan, the University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Asan Medical Center, in Seoul, Korea, the Imperial College, Chelsea and Westminster Hospital, in London, United Kingdom and Dunedin Hospital, Dunedin, New Zealand.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

We included patients 18-89 years of age (20-89 in Taiwan because patients under 20 years of age in this country are a restricted group with respect to participating in research), admitted to an internal medicine service from the Emergency Department or Urgent Care clinic with an acute illness for a minimum of 24 hours (with time zero defined as the time care was initiated in the Emergency Department or Urgent Care Clinic), who reported pain at some time during the first 24-36 hours of their hospitalization and who provided informed consent. In the US, “admission” included both observation and inpatient status. We limited the patient population to those admitted via emergency departments and urgent care clinics in order to enroll similar patient populations across sites.

Scheduled admissions, patients transferred from an outside facility, patients admitted directly from a clinic, and those receiving care in intensive care units were excluded. We also excluded patients who were incarcerated, pregnant, those who received major surgery within the previous 14 days, those with a known diagnosis of active cancer, and those who were receiving palliative or hospice care. Patients receiving care from an investigator in the study at the time of enrollment were not eligible due to the potential conflict of interest.

Patient Screening

Primary teams were contacted to determine if any patients on their service might meet the criteria for inclusion in the study on preselected study days chosen on the basis of the research team’s availability. Identified patients were then screened to establish if they met the eligibility criteria. Patients were asked directly if they had experienced pain during their preadmission evaluation or during their hospitalization.

Data Collection

All patients were hospitalized at the time they gave consent and when data were collected. Data were collected via interviews with patients, as well as through chart review. We recorded patients’ age, gender, race, admitting diagnosis(es), length of stay, psychiatric illness, illicit drug use, whether they reported receiving opioid analgesics at the time of hospitalization, whether they were prescribed opioids and/or nonopioid analgesics during their hospitalization, the median and maximum doses of opioids prescribed and dispensed, and whether they were discharged on opioids. The question of illicit drug use was asked of all patients with the exception of those hospitalized in South Korea due to potential legal implications.

Opioid prescribing and receipt of opioids was recorded based upon current provider orders and medication administration records, respectively. Perception of and satisfaction with pain control was assessed with the American Pain Society Patient Outcome Questionnaire–Modified (APS-POQ-Modified).24,25 Versions of this survey have been validated in English as well as in other languages and cultures.26-28 Because hospitalization practices could differ across hospitals and in different countries, we compared patients’ severity of illness by using Charlson comorbidity scores. Consent forms and the APS-POQ were translated into each country’s primary language according to established processes.29 The survey was filled out by having site investigators read questions aloud and by use of a large-font visual analog scale to aid patients’ verbal responses.

Data were collected and managed using a secure, web-based application electronic data capture tool (Research Electronic Data Capture [REDCap], Nashville, Tennessee), hosted at Denver Health.30

Study Size

Preliminary data from the internal medicine units at our institution suggested that 40% of patients without cancer received opioid analgesics during their hospitalization. Assuming 90% power to detect an absolute difference in the proportion of inpatient medical patients who are receiving opioid analgesics during their hospital stay of 17%, a two-sided type 1 error rate of 0.05, six hospitals in the US, and nine hospitals from all other countries, we calculated an initial sample size of 150 patients per site. This sample size was considered feasible for enrollment in a busy inpatient clinical setting. Study end points were to either reach the goal number of patients (150 per site) or the predetermined study end date, whichever came first.

Data Analysis

We generated means with standard deviations (SDs) and medians with interquartile ranges (IQRs) for normally and nonnormally distributed continuous variables, respectively, and frequencies for categorical variables. We used linear mixed modeling for the analysis of continuous variables. For binary outcomes, our data were fitted to a generalized linear mixed model with logit as the link function and a binary distribution. For ordinal variables, specifically patient-reported satisfaction with pain control and the opinion statements, the data were fitted to a generalized linear mixed model with a cumulative logit link and a multinomial distribution. Hospital was included as a random effect in all models to account for patients cared for in the same hospital.

Country of origin, dichotomized as US or non-US, was the independent variable of interest for all models. An interaction term for exposure to opioids prior to admission and country was entered into all models to explore whether differences in the effect of country existed for patients who reported taking opioids prior to admission and those who did not.

The models for the frequency with which analgesics were given, doses of opioids given during hospitalization and at discharge, patient-reported pain score, and patient-reported satisfaction with pain control were adjusted for (1) age, (2) gender, (3) Charlson Comorbidity Index, (4) length of stay, (5) history of illicit drug use, (6) history of psychiatric illness, (7) daily dose in morphine milligram equivalents (MME) for opioids prior to admission, (8) average pain score, and (9) hospital. The patient-reported satisfaction with pain control model was also adjusted for whether or not opioids were given to the patient during their hospitalization. P < .05 was considered to indicate significance. All analyses were performed using SAS Enterprise Guide 7.1 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina). We reported data on medications that were prescribed and dispensed (as opposed to just prescribed and not necessarily given). Opioids prescribed at discharge represented the total possible opioids that could be given based upon the order/prescription (eg, oxycodone 5 mg every 6 hours as needed for pain would be counted as 20 mg/24 hours maximum possible dose followed by conversion to MME).

Missing Data

When there were missing data, a query was sent to sites to verify if the data were retrievable. If retrievable, the data were then entered. Data were missing in 5% and 2% of patients who did or did not report taking an opioid prior to admission, respectively. If a variable was included in a specific statistical test, then subjects with missing data were excluded from that analysis (ie, complete case analysis).

RESULTS

We approached 1,309 eligible patients, of which 981 provided informed consent, for a response rate of 75%; 503 from the US and 478 patients from other countries (Figure). In unadjusted analyses, we found no significant differences between US and non-US patients in age (mean age 51, SD 15 vs 59, SD 19; P = .30), race, ethnicity, or Charlson comorbidity index scores (median 2, IQR 1-3 vs 3, IQR 1-4; P = .45). US patients had shorter lengths of stay (median 3 days, IQR 2-4 vs 6 days, IQR 3-11; P = .04), a more frequent history of illicit drug use (33% vs 6%; P = .003), a higher frequency of psychiatric illness (27% vs 8%; P < .0001), and more were receiving opioid analgesics prior to admission (38% vs 17%; P = .007) than those hospitalized in other countries (Table 1, Appendix 1). The primary admitting diagnoses for all patients in the study are listed in Appendix 2. Opioid prescribing practices across the individual sites are shown in Appendix 3.

Patients Taking Opioids Prior to Admission

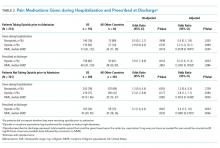

After adjusting for relevant covariates, we found that more patients in the US were given opioids during their hospitalization and in higher doses than patients from other countries and more were prescribed opioids at discharge. Fewer patients in the US were dispensed nonopioid analgesics during their hospitalization than patients from other countries, but this difference was not significant (Table 2). Appendix 4 shows the types of nonopioid pain medications prescribed in the US and other countries.

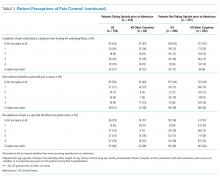

After adjustment for relevant covariates, US patients reported greater pain severity at the time they completed their pain surveys. We found no significant difference in satisfaction with pain control between patients from the US and other countries in the models, regardless of whether we included average pain score or opioid receipt during hospitalization in the model (Table 3).

In unadjusted analyses, compared with patients hospitalized in other countries, more patients in the US stated that they would like a stronger dose of analgesic if they were still in pain, though the difference was nonsignificant, and US patients were more likely to agree with the statement that people become addicted to pain medication easily and less likely to agree with the statement that it is easier to endure pain than deal with the side effects of pain medications (Table 3).

Patients Not Taking Opioids Prior to Admission

After adjusting for relevant covariates, we found no significant difference in the proportion of US patients provided with nonopioid pain medications during their hospitalization compared with patients in other countries, but a greater percentage of US patients were given opioids during their hospitalization and at discharge and in higher doses (Table 2).

After adjusting for relevant covariates, US patients reported greater pain severity at the time they completed their pain surveys and greater pain severity in the 24-36 hours prior to completing the survey than patients from other countries, but we found no difference in patient satisfaction with pain control (Table 3). After we included the average pain score and whether or not opioids were given to the patient during their hospitalization in this model, patients in the US were more likely to report a higher level of satisfaction with pain control than patients in all other countries (P = .001).

In unadjusted analyses, compared with patients hospitalized in other countries, those in the US were less likely to agree with the statement that good patients avoid talking about pain (Table 3).

Patient Satisfaction and Opioid Receipt

Among patients cared for in the US, after controlling for the average pain score, we did not find a significant association between receiving opioids while in the hospital and satisfaction with pain control for patients who either did or did not endorse taking opioids prior to admission (P = .38 and P = .24, respectively). Among patients cared for in all other countries, after controlling for the average pain score, we found a significant association between receiving opioids while in the hospital and a lower level of satisfaction with pain control for patients who reported taking opioids prior to admission (P = .02) but not for patients who did not report taking opioids prior to admission (P = .08).

DISCUSSION

Compared with patients hospitalized in other countries, a greater percentage of those hospitalized in the US were prescribed opioid analgesics both during hospitalization and at the time of discharge, even after adjustment for pain severity. In addition, patients hospitalized in the US reported greater pain severity at the time they completed their pain surveys and in the 24 to 36 hours prior to completing the survey than patients from other countries. In this sample, satisfaction, beliefs, and expectations about pain control differed between patients in the US and other sites. Our study also suggests that opioid receipt did not lead to improved patient satisfaction with pain control.

The frequency with which we observed opioid analgesics being prescribed during hospitalization in US hospitals (79%) was higher than the 51% of patients who received opioids reported by Herzig and colleagues.10 Patients in our study had a higher prevalence of illicit drug abuse and psychiatric illness, and our study only included patients who reported pain at some point during their hospitalization. We also studied prescribing practices through analysis of provider orders and medication administration records at the time the patient was hospitalized.

While we observed that physicians in the US more frequently prescribed opioid analgesics during hospitalizations than physicians working in other countries, we also observed that patients in the US reported higher levels of pain during their hospitalization. After adjusting for a number of variables, including pain severity, however, we still found that opioids were more commonly prescribed during hospitalizations by physicians working in the US sites studied than by physicians in the non-US sites.

Opioid prescribing practices varied across the sites sampled in our study. While the US sites, Taiwan, and Korea tended to be heavier utilizers of opioids during hospitalization, there were notable differences in discharge prescribing of opioids, with the US sites more commonly prescribing opioids and higher MME for patients who did not report taking opioids prior to their hospitalization (Appendix 3). A sensitivity analysis was conducted excluding South Korea from modeling, given that patients there were not asked about illicit opioid use. There were no important changes in the magnitude or direction of the results.

Our study supports previous studies indicating that there are cultural and societal differences when it comes to the experience of pain and the expectations around pain control.17,20-22,31 Much of the focus on reducing opioid utilization has been on provider practices32 and on prescription drug monitoring programs.33 Our findings suggest that another area of focus that may be important in mitigating the opioid epidemic is patient expectations of pain control.

Our study has a number of strengths. First, we included 11 hospitals from eight different countries. Second, we believe this is the first study to assess opioid prescribing and dispensing practices during hospitalization as well as at the time of discharge. Third, patient perceptions of pain control were assessed in conjunction with analgesic prescribing and were assessed during hospitalization. Fourth, we had high response rates for patient participation in our study. Fifth, we found much larger differences in opioid prescribing than anticipated, and thus, while we did not achieve the sample size originally planned for either the number of hospitals or patients enrolled per hospital, we were sufficiently powered. This is likely secondary to the fact that the population we studied was one that specifically reported pain, resulting in the larger differences seen.

Our study also had a number of limitations. First, the prescribing practices in countries other than the US are represented by only one hospital per country and, in some countries, by limited numbers of patients. While we studied four sites in the US, we did not have a site in the Northeast, a region previously shown to have lower prescribing rates.10 Additionally, patient samples for the US sites compared with the sites in other countries varied considerably with respect to ethnicity. While some studies in US patients have shown that opioid prescribing may vary based on race/ethnicity,34 we are uncertain as to how this might impact a study that crosses multiple countries. We also had a low number of patients receiving opioids prior to hospitalization for several of the non-US countries, which reduced the power to detect differences in this subgroup. Previous research has shown that there are wide variations in prescribing practices even within countries;10,12,18 therefore, caution should be taken when generalizing our findings. Second, we assessed analgesic prescribing patterns and pain control during the first 24 to 36 hours of hospitalization and did not consider hospital days beyond this timeframe with the exception of noting what medications were prescribed at discharge. We chose this methodology in an attempt to eliminate as many differences that might exist in the duration of hospitalization across many countries. Third, investigators in the study administered the survey, and respondents may have been affected by social desirability bias in how the survey questions were answered. Because investigators were not a part of the care team of any study patients, we believe this to be unlikely. Fourth, our study was conducted from October 8, 2013 to August 31, 2015 and the opioid epidemic is dynamic. Accordingly, our data may not reflect current opioid prescribing practices or patients’ current beliefs regarding pain control. Fifth, we did not collect demographic data on the patients who did not participate and could not look for systematic differences between participants and nonparticipants. Sixth, we relied on patients to self-report whether they were taking opioids prior to hospitalization or using illicit drugs. Seventh, we found comorbid mental health conditions to be more frequent in the US population studied. Previous work has shown regional variation in mental health conditions,35,36 which could have affected our findings. To account for this, our models included psychiatric illness.

CONCLUSIONS

Our data suggest that physicians in the US may prescribe opioids more frequently during patients’ hospitalizations and at discharge than their colleagues in other countries. We also found that patient satisfaction, beliefs, and expectations about pain control differed between patients in the US and other sites. Although the small number of hospitals included in our sample coupled with the small sample size in some of the non-US countries limits the generalizability of our findings, the data suggest that reducing the opioid epidemic in the US may require addressing patients’ expectations regarding pain control in addition to providers’ inpatient analgesic prescribing patterns.

Disclosures

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Funding

The authors report no funding source for this work.

1. Pletcher MJ, Kertesz SG, Kohn MA, Gonzales R. Trends in opioid prescribing by race/ethnicity for patients seeking care in US emergency departments. JAMA. 2008;299(1):70-78. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2007.64.

2. Herzig SJ. Growing concerns regarding long-term opioid use: the hospitalization hazard. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(7):469-470. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2369.

3. Guy GP Jr, Zhang K, Bohm MK, et al. Vital Signs: changes in opioid prescribing in the United States, 2006–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(26):697-704. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6626a4.

4. Okie S. A flood of opioids, a rising tide of deaths. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(21):1981-1985. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1011512.

5. Liang Y, Turner BJ. National cohort study of opioid analgesic dose and risk of future hospitalization. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(7):425-431. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2350.

6. Han B, Compton WM, Blanco C, et al. Prescription opioid use, misuse, and use disorders in U.S. Adults: 2015 national survey on drug use and health. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(5):293-301. https://doi.org/10.7326/M17-0865.

7. Schuchat A, Houry D, Guy GP, Jr. New data on opioid use and prescribing in the United States. JAMA. 2017;318(5):425-426. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.8913.

8. Sawyer J, Haslam L, Robinson S, Daines P, Stilos K. Pain prevalence study in a large Canadian teaching hospital. Pain Manag Nurs. 2008;9(3):104-112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmn.2008.02.001.

9. Gupta A, Daigle S, Mojica J, Hurley RW. Patient perception of pain care in hospitals in the United States. J Pain Res. 2009;2:157-164. https://doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S7903.

10. Herzig SJ, Rothberg MB, Cheung M, Ngo LH, Marcantonio ER. Opioid utilization and opioid-related adverse events in nonsurgical patients in US hospitals. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(2):73-81. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2102.

11. Kanjanarat P, Winterstein AG, Johns TE, et al. Nature of preventable adverse drug events in hospitals: a literature review. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2003;60(17):1750-1759. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajhp/60.17.1750.

12. Jena AB, Goldman D, Karaca-Mandic P. Hospital prescribing of opioids to medicare beneficiaries. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(7):990-997. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.2737.

13. Hooten WM, St Sauver JL, McGree ME, Jacobson DJ, Warner DO. Incidence and risk factors for progression From short-term to episodic or long-term opioid prescribing: A population-based study. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(7):850-856. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.04.012.

14. Alam A, Gomes T, Zheng H, et al. Long-term analgesic use after low-risk surgery: a retrospective cohort study. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(5):425-430. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2011.1827.

15. Barnett ML, Olenski AR, Jena AB. Opioid-prescribing patterns of emergency physicians and risk of long-term use. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(7):663-673. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa1610524.

16. Calcaterra SL, Scarbro S, Hull ML, et al. Prediction of future chronic opioid use Among hospitalized patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(6):898-905. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4335-8.

17. Callister LC. Cultural influences on pain perceptions and behaviors. Home Health Care Manag Pract. 2003;15(3):207-211. https://doi.org/10.1177/1084822302250687.

18. Paulozzi LJ, Mack KA, Hockenberry JM. Vital signs: Variation among states in prescribing of opioid pain relievers and benzodiazepines--United States, 2012. J Saf Res. 2014;63(26):563-568. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsr.2014.09.001.

19. Callister LC, Khalaf I, Semenic S, Kartchner R, Vehvilainen-Julkunen K. The pain of childbirth: perceptions of culturally diverse women. Pain Manag Nurs. 2003;4(4):145-154. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1524-9042(03)00028-6.

20. Moore R, Brødsgaard I, Mao TK, Miller ML, Dworkin SF. Perceived need for local anesthesia in tooth drilling among Anglo-Americans, Chinese, and Scandinavians. Anesth Prog. 1998;45(1):22-28.

21. Kankkunen PM, Vehviläinen-Julkunen KM, Pietilä AM, et al. A tale of two countries: comparison of the perceptions of analgesics among Finnish and American parents. Pain Manag Nurs. 2008;9(3):113-119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmn.2007.12.003.

22. Hanoch Y, Katsikopoulos KV, Gummerum M, Brass EP. American and German students’ knowledge, perceptions, and behaviors with respect to over-the-counter pain relievers. Health Psychol. 2007;26(6):802-806. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.26.6.802.

23. Manjiani D, Paul DB, Kunnumpurath S, Kaye AD, Vadivelu N. Availability and utilization of opioids for pain management: global issues. Ochsner J. 2014;14(2):208-215.

24. Quality improvement guidelines for the treatment of acute pain and cancer pain. JAMA. 1995;274(23):1874-1880.

25. McNeill JA, Sherwood GD, Starck PL, Thompson CJ. Assessing clinical outcomes: patient satisfaction with pain management. J Pain Symptom Manag. 1998;16(1):29-40. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0885-3924(98)00034-7.

26. Ferrari R, Novello C, Catania G, Visentin M. Patients’ satisfaction with pain management: the Italian version of the Patient Outcome Questionnaire of the American Pain Society. Recenti Prog Med. 2010;101(7–8):283-288.

27. Malouf J, Andión O, Torrubia R, Cañellas M, Baños JE. A survey of perceptions with pain management in Spanish inpatients. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2006;32(4):361-371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.05.006.

28. Gordon DB, Polomano RC, Pellino TA, et al. Revised American Pain Society Patient Outcome Questionnaire (APS-POQ-R) for quality improvement of pain management in hospitalized adults: preliminary psychometric evaluation. J Pain. 2010;11(11):1172-1186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2010.02.012.

29. Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, Ferraz MB. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25(24):3186-3191. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007632-200012150-00014.

30. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377-381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010.

31. Duman F. After surgery in Germany, I wanted Vicodin, not herbal tea. New York Times. January 27, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/01/27/opinion/sunday/surgery-germany-vicodin.html. Accessed November 6, 2018.

32. Beaudoin FL, Banerjee GN, Mello MJ. State-level and system-level opioid prescribing policies: the impact on provider practices and overdose deaths, a systematic review. J Opioid Manag. 2016;12(2):109-118. https://doi.org/10.5055/jom.2016.0322. 33. Bao Y, Wen K, Johnson P, et al. Assessing the impact of state policies for prescription drug monitoring programs on high-risk opioid prescriptions. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(10):1596-1604. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2018.0512.

33. Bao Y, Wen K, Johnson P, et al. Assessing the impact of state policies for prescription drug monitoring programs on high-risk opioid prescriptions. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(10):1596-1604. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2018.0512.

34. Friedman J, Kim D, Schneberk T, et al. Assessment of racial/ethnic and income disparities in the prescription of opioids and other controlled medications in California. JAMA Intern Med. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.6721.

35. Steel Z, Marnane C, Iranpour C, et al. The global prevalence of common mental disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis 1980-2013. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43(2):476-493. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyu038.

36. Simon GE, Goldberg DP, Von Korff M, Ustün TB. Understanding cross-national differences in depression prevalence. Psychol Med. 2002;32(4):585-594. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291702005457.

Since 2000, the United States has seen a marked increase in opioid prescribing1-3 and opioid-related complications, including overdoses, hospitalizations, and deaths.2,4,5 A study from 2015 showed that more than one-third of the US civilian noninstitutionalized population reported receiving an opioid prescription in the prior year, with 12.5% reporting misuse, and, of those, 16.7% reported a prescription use disorder.6 While there has been a slight decrease in opioid prescriptions in the US since 2012, rates of opioid prescribing in 2015 were three times higher than in 1999 and approximately four times higher than in Europe in 2015.3,7

Pain is commonly reported by hospitalized patients,8,9 and opioids are often a mainstay of treatment;9,10 however, treatment with opioids can have a number of adverse outcomes.2,10,11 Short-term exposure to opioids can lead to long-term use,12-16 and patients on opioids are at an increased risk for subsequent hospitalization and longer inpatient lengths of stay.5

Physician prescribing practices for opioids and patient expectations for pain control vary as a function of geographic region and culture,10,12,17,18 and pain is influenced by the cultural context in which it occurs.17,19-22 Treatment of pain may also be affected by limited access to or restrictions on selected medications, as well as by cultural biases.23 Whether these variations in the treatment of pain are reflected in patients’ satisfaction with pain control is uncertain.

We sought to compare the inpatient analgesic prescribing practices and patients’ perceptions of pain control for medical patients in four teaching hospitals in the US and in seven teaching hospitals in seven other countries.

METHODS

Study Design

We utilized a cross-sectional, observational design. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at all participating sites.

Setting

The study was conducted at 11 academic hospitals in eight countries from October 8, 2013 to August 31, 2015. Sites in the US included Denver Health in Denver, Colorado; the University of Colorado Hospital in Aurora, Colorado; Hennepin Healthcare in Minneapolis, Minnesota; and Legacy Health in Portland, Oregon. Sites outside the US included McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada; Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Universitat Autonòma de Barcelona in Barcelona, Spain; the University of Study of Milan and the University Ospedale “Luigi Sacco” in Milan, Italy, the National Taiwan University Hospital, in Taipei, Taiwan, the University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Asan Medical Center, in Seoul, Korea, the Imperial College, Chelsea and Westminster Hospital, in London, United Kingdom and Dunedin Hospital, Dunedin, New Zealand.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

We included patients 18-89 years of age (20-89 in Taiwan because patients under 20 years of age in this country are a restricted group with respect to participating in research), admitted to an internal medicine service from the Emergency Department or Urgent Care clinic with an acute illness for a minimum of 24 hours (with time zero defined as the time care was initiated in the Emergency Department or Urgent Care Clinic), who reported pain at some time during the first 24-36 hours of their hospitalization and who provided informed consent. In the US, “admission” included both observation and inpatient status. We limited the patient population to those admitted via emergency departments and urgent care clinics in order to enroll similar patient populations across sites.

Scheduled admissions, patients transferred from an outside facility, patients admitted directly from a clinic, and those receiving care in intensive care units were excluded. We also excluded patients who were incarcerated, pregnant, those who received major surgery within the previous 14 days, those with a known diagnosis of active cancer, and those who were receiving palliative or hospice care. Patients receiving care from an investigator in the study at the time of enrollment were not eligible due to the potential conflict of interest.

Patient Screening

Primary teams were contacted to determine if any patients on their service might meet the criteria for inclusion in the study on preselected study days chosen on the basis of the research team’s availability. Identified patients were then screened to establish if they met the eligibility criteria. Patients were asked directly if they had experienced pain during their preadmission evaluation or during their hospitalization.

Data Collection

All patients were hospitalized at the time they gave consent and when data were collected. Data were collected via interviews with patients, as well as through chart review. We recorded patients’ age, gender, race, admitting diagnosis(es), length of stay, psychiatric illness, illicit drug use, whether they reported receiving opioid analgesics at the time of hospitalization, whether they were prescribed opioids and/or nonopioid analgesics during their hospitalization, the median and maximum doses of opioids prescribed and dispensed, and whether they were discharged on opioids. The question of illicit drug use was asked of all patients with the exception of those hospitalized in South Korea due to potential legal implications.

Opioid prescribing and receipt of opioids was recorded based upon current provider orders and medication administration records, respectively. Perception of and satisfaction with pain control was assessed with the American Pain Society Patient Outcome Questionnaire–Modified (APS-POQ-Modified).24,25 Versions of this survey have been validated in English as well as in other languages and cultures.26-28 Because hospitalization practices could differ across hospitals and in different countries, we compared patients’ severity of illness by using Charlson comorbidity scores. Consent forms and the APS-POQ were translated into each country’s primary language according to established processes.29 The survey was filled out by having site investigators read questions aloud and by use of a large-font visual analog scale to aid patients’ verbal responses.

Data were collected and managed using a secure, web-based application electronic data capture tool (Research Electronic Data Capture [REDCap], Nashville, Tennessee), hosted at Denver Health.30

Study Size

Preliminary data from the internal medicine units at our institution suggested that 40% of patients without cancer received opioid analgesics during their hospitalization. Assuming 90% power to detect an absolute difference in the proportion of inpatient medical patients who are receiving opioid analgesics during their hospital stay of 17%, a two-sided type 1 error rate of 0.05, six hospitals in the US, and nine hospitals from all other countries, we calculated an initial sample size of 150 patients per site. This sample size was considered feasible for enrollment in a busy inpatient clinical setting. Study end points were to either reach the goal number of patients (150 per site) or the predetermined study end date, whichever came first.

Data Analysis

We generated means with standard deviations (SDs) and medians with interquartile ranges (IQRs) for normally and nonnormally distributed continuous variables, respectively, and frequencies for categorical variables. We used linear mixed modeling for the analysis of continuous variables. For binary outcomes, our data were fitted to a generalized linear mixed model with logit as the link function and a binary distribution. For ordinal variables, specifically patient-reported satisfaction with pain control and the opinion statements, the data were fitted to a generalized linear mixed model with a cumulative logit link and a multinomial distribution. Hospital was included as a random effect in all models to account for patients cared for in the same hospital.

Country of origin, dichotomized as US or non-US, was the independent variable of interest for all models. An interaction term for exposure to opioids prior to admission and country was entered into all models to explore whether differences in the effect of country existed for patients who reported taking opioids prior to admission and those who did not.

The models for the frequency with which analgesics were given, doses of opioids given during hospitalization and at discharge, patient-reported pain score, and patient-reported satisfaction with pain control were adjusted for (1) age, (2) gender, (3) Charlson Comorbidity Index, (4) length of stay, (5) history of illicit drug use, (6) history of psychiatric illness, (7) daily dose in morphine milligram equivalents (MME) for opioids prior to admission, (8) average pain score, and (9) hospital. The patient-reported satisfaction with pain control model was also adjusted for whether or not opioids were given to the patient during their hospitalization. P < .05 was considered to indicate significance. All analyses were performed using SAS Enterprise Guide 7.1 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina). We reported data on medications that were prescribed and dispensed (as opposed to just prescribed and not necessarily given). Opioids prescribed at discharge represented the total possible opioids that could be given based upon the order/prescription (eg, oxycodone 5 mg every 6 hours as needed for pain would be counted as 20 mg/24 hours maximum possible dose followed by conversion to MME).

Missing Data

When there were missing data, a query was sent to sites to verify if the data were retrievable. If retrievable, the data were then entered. Data were missing in 5% and 2% of patients who did or did not report taking an opioid prior to admission, respectively. If a variable was included in a specific statistical test, then subjects with missing data were excluded from that analysis (ie, complete case analysis).

RESULTS

We approached 1,309 eligible patients, of which 981 provided informed consent, for a response rate of 75%; 503 from the US and 478 patients from other countries (Figure). In unadjusted analyses, we found no significant differences between US and non-US patients in age (mean age 51, SD 15 vs 59, SD 19; P = .30), race, ethnicity, or Charlson comorbidity index scores (median 2, IQR 1-3 vs 3, IQR 1-4; P = .45). US patients had shorter lengths of stay (median 3 days, IQR 2-4 vs 6 days, IQR 3-11; P = .04), a more frequent history of illicit drug use (33% vs 6%; P = .003), a higher frequency of psychiatric illness (27% vs 8%; P < .0001), and more were receiving opioid analgesics prior to admission (38% vs 17%; P = .007) than those hospitalized in other countries (Table 1, Appendix 1). The primary admitting diagnoses for all patients in the study are listed in Appendix 2. Opioid prescribing practices across the individual sites are shown in Appendix 3.

Patients Taking Opioids Prior to Admission

After adjusting for relevant covariates, we found that more patients in the US were given opioids during their hospitalization and in higher doses than patients from other countries and more were prescribed opioids at discharge. Fewer patients in the US were dispensed nonopioid analgesics during their hospitalization than patients from other countries, but this difference was not significant (Table 2). Appendix 4 shows the types of nonopioid pain medications prescribed in the US and other countries.

After adjustment for relevant covariates, US patients reported greater pain severity at the time they completed their pain surveys. We found no significant difference in satisfaction with pain control between patients from the US and other countries in the models, regardless of whether we included average pain score or opioid receipt during hospitalization in the model (Table 3).

In unadjusted analyses, compared with patients hospitalized in other countries, more patients in the US stated that they would like a stronger dose of analgesic if they were still in pain, though the difference was nonsignificant, and US patients were more likely to agree with the statement that people become addicted to pain medication easily and less likely to agree with the statement that it is easier to endure pain than deal with the side effects of pain medications (Table 3).

Patients Not Taking Opioids Prior to Admission

After adjusting for relevant covariates, we found no significant difference in the proportion of US patients provided with nonopioid pain medications during their hospitalization compared with patients in other countries, but a greater percentage of US patients were given opioids during their hospitalization and at discharge and in higher doses (Table 2).

After adjusting for relevant covariates, US patients reported greater pain severity at the time they completed their pain surveys and greater pain severity in the 24-36 hours prior to completing the survey than patients from other countries, but we found no difference in patient satisfaction with pain control (Table 3). After we included the average pain score and whether or not opioids were given to the patient during their hospitalization in this model, patients in the US were more likely to report a higher level of satisfaction with pain control than patients in all other countries (P = .001).

In unadjusted analyses, compared with patients hospitalized in other countries, those in the US were less likely to agree with the statement that good patients avoid talking about pain (Table 3).

Patient Satisfaction and Opioid Receipt

Among patients cared for in the US, after controlling for the average pain score, we did not find a significant association between receiving opioids while in the hospital and satisfaction with pain control for patients who either did or did not endorse taking opioids prior to admission (P = .38 and P = .24, respectively). Among patients cared for in all other countries, after controlling for the average pain score, we found a significant association between receiving opioids while in the hospital and a lower level of satisfaction with pain control for patients who reported taking opioids prior to admission (P = .02) but not for patients who did not report taking opioids prior to admission (P = .08).

DISCUSSION

Compared with patients hospitalized in other countries, a greater percentage of those hospitalized in the US were prescribed opioid analgesics both during hospitalization and at the time of discharge, even after adjustment for pain severity. In addition, patients hospitalized in the US reported greater pain severity at the time they completed their pain surveys and in the 24 to 36 hours prior to completing the survey than patients from other countries. In this sample, satisfaction, beliefs, and expectations about pain control differed between patients in the US and other sites. Our study also suggests that opioid receipt did not lead to improved patient satisfaction with pain control.

The frequency with which we observed opioid analgesics being prescribed during hospitalization in US hospitals (79%) was higher than the 51% of patients who received opioids reported by Herzig and colleagues.10 Patients in our study had a higher prevalence of illicit drug abuse and psychiatric illness, and our study only included patients who reported pain at some point during their hospitalization. We also studied prescribing practices through analysis of provider orders and medication administration records at the time the patient was hospitalized.

While we observed that physicians in the US more frequently prescribed opioid analgesics during hospitalizations than physicians working in other countries, we also observed that patients in the US reported higher levels of pain during their hospitalization. After adjusting for a number of variables, including pain severity, however, we still found that opioids were more commonly prescribed during hospitalizations by physicians working in the US sites studied than by physicians in the non-US sites.

Opioid prescribing practices varied across the sites sampled in our study. While the US sites, Taiwan, and Korea tended to be heavier utilizers of opioids during hospitalization, there were notable differences in discharge prescribing of opioids, with the US sites more commonly prescribing opioids and higher MME for patients who did not report taking opioids prior to their hospitalization (Appendix 3). A sensitivity analysis was conducted excluding South Korea from modeling, given that patients there were not asked about illicit opioid use. There were no important changes in the magnitude or direction of the results.

Our study supports previous studies indicating that there are cultural and societal differences when it comes to the experience of pain and the expectations around pain control.17,20-22,31 Much of the focus on reducing opioid utilization has been on provider practices32 and on prescription drug monitoring programs.33 Our findings suggest that another area of focus that may be important in mitigating the opioid epidemic is patient expectations of pain control.

Our study has a number of strengths. First, we included 11 hospitals from eight different countries. Second, we believe this is the first study to assess opioid prescribing and dispensing practices during hospitalization as well as at the time of discharge. Third, patient perceptions of pain control were assessed in conjunction with analgesic prescribing and were assessed during hospitalization. Fourth, we had high response rates for patient participation in our study. Fifth, we found much larger differences in opioid prescribing than anticipated, and thus, while we did not achieve the sample size originally planned for either the number of hospitals or patients enrolled per hospital, we were sufficiently powered. This is likely secondary to the fact that the population we studied was one that specifically reported pain, resulting in the larger differences seen.

Our study also had a number of limitations. First, the prescribing practices in countries other than the US are represented by only one hospital per country and, in some countries, by limited numbers of patients. While we studied four sites in the US, we did not have a site in the Northeast, a region previously shown to have lower prescribing rates.10 Additionally, patient samples for the US sites compared with the sites in other countries varied considerably with respect to ethnicity. While some studies in US patients have shown that opioid prescribing may vary based on race/ethnicity,34 we are uncertain as to how this might impact a study that crosses multiple countries. We also had a low number of patients receiving opioids prior to hospitalization for several of the non-US countries, which reduced the power to detect differences in this subgroup. Previous research has shown that there are wide variations in prescribing practices even within countries;10,12,18 therefore, caution should be taken when generalizing our findings. Second, we assessed analgesic prescribing patterns and pain control during the first 24 to 36 hours of hospitalization and did not consider hospital days beyond this timeframe with the exception of noting what medications were prescribed at discharge. We chose this methodology in an attempt to eliminate as many differences that might exist in the duration of hospitalization across many countries. Third, investigators in the study administered the survey, and respondents may have been affected by social desirability bias in how the survey questions were answered. Because investigators were not a part of the care team of any study patients, we believe this to be unlikely. Fourth, our study was conducted from October 8, 2013 to August 31, 2015 and the opioid epidemic is dynamic. Accordingly, our data may not reflect current opioid prescribing practices or patients’ current beliefs regarding pain control. Fifth, we did not collect demographic data on the patients who did not participate and could not look for systematic differences between participants and nonparticipants. Sixth, we relied on patients to self-report whether they were taking opioids prior to hospitalization or using illicit drugs. Seventh, we found comorbid mental health conditions to be more frequent in the US population studied. Previous work has shown regional variation in mental health conditions,35,36 which could have affected our findings. To account for this, our models included psychiatric illness.

CONCLUSIONS

Our data suggest that physicians in the US may prescribe opioids more frequently during patients’ hospitalizations and at discharge than their colleagues in other countries. We also found that patient satisfaction, beliefs, and expectations about pain control differed between patients in the US and other sites. Although the small number of hospitals included in our sample coupled with the small sample size in some of the non-US countries limits the generalizability of our findings, the data suggest that reducing the opioid epidemic in the US may require addressing patients’ expectations regarding pain control in addition to providers’ inpatient analgesic prescribing patterns.

Disclosures

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Funding

The authors report no funding source for this work.

Since 2000, the United States has seen a marked increase in opioid prescribing1-3 and opioid-related complications, including overdoses, hospitalizations, and deaths.2,4,5 A study from 2015 showed that more than one-third of the US civilian noninstitutionalized population reported receiving an opioid prescription in the prior year, with 12.5% reporting misuse, and, of those, 16.7% reported a prescription use disorder.6 While there has been a slight decrease in opioid prescriptions in the US since 2012, rates of opioid prescribing in 2015 were three times higher than in 1999 and approximately four times higher than in Europe in 2015.3,7

Pain is commonly reported by hospitalized patients,8,9 and opioids are often a mainstay of treatment;9,10 however, treatment with opioids can have a number of adverse outcomes.2,10,11 Short-term exposure to opioids can lead to long-term use,12-16 and patients on opioids are at an increased risk for subsequent hospitalization and longer inpatient lengths of stay.5

Physician prescribing practices for opioids and patient expectations for pain control vary as a function of geographic region and culture,10,12,17,18 and pain is influenced by the cultural context in which it occurs.17,19-22 Treatment of pain may also be affected by limited access to or restrictions on selected medications, as well as by cultural biases.23 Whether these variations in the treatment of pain are reflected in patients’ satisfaction with pain control is uncertain.

We sought to compare the inpatient analgesic prescribing practices and patients’ perceptions of pain control for medical patients in four teaching hospitals in the US and in seven teaching hospitals in seven other countries.

METHODS

Study Design

We utilized a cross-sectional, observational design. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at all participating sites.

Setting

The study was conducted at 11 academic hospitals in eight countries from October 8, 2013 to August 31, 2015. Sites in the US included Denver Health in Denver, Colorado; the University of Colorado Hospital in Aurora, Colorado; Hennepin Healthcare in Minneapolis, Minnesota; and Legacy Health in Portland, Oregon. Sites outside the US included McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada; Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Universitat Autonòma de Barcelona in Barcelona, Spain; the University of Study of Milan and the University Ospedale “Luigi Sacco” in Milan, Italy, the National Taiwan University Hospital, in Taipei, Taiwan, the University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Asan Medical Center, in Seoul, Korea, the Imperial College, Chelsea and Westminster Hospital, in London, United Kingdom and Dunedin Hospital, Dunedin, New Zealand.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

We included patients 18-89 years of age (20-89 in Taiwan because patients under 20 years of age in this country are a restricted group with respect to participating in research), admitted to an internal medicine service from the Emergency Department or Urgent Care clinic with an acute illness for a minimum of 24 hours (with time zero defined as the time care was initiated in the Emergency Department or Urgent Care Clinic), who reported pain at some time during the first 24-36 hours of their hospitalization and who provided informed consent. In the US, “admission” included both observation and inpatient status. We limited the patient population to those admitted via emergency departments and urgent care clinics in order to enroll similar patient populations across sites.

Scheduled admissions, patients transferred from an outside facility, patients admitted directly from a clinic, and those receiving care in intensive care units were excluded. We also excluded patients who were incarcerated, pregnant, those who received major surgery within the previous 14 days, those with a known diagnosis of active cancer, and those who were receiving palliative or hospice care. Patients receiving care from an investigator in the study at the time of enrollment were not eligible due to the potential conflict of interest.

Patient Screening

Primary teams were contacted to determine if any patients on their service might meet the criteria for inclusion in the study on preselected study days chosen on the basis of the research team’s availability. Identified patients were then screened to establish if they met the eligibility criteria. Patients were asked directly if they had experienced pain during their preadmission evaluation or during their hospitalization.

Data Collection

All patients were hospitalized at the time they gave consent and when data were collected. Data were collected via interviews with patients, as well as through chart review. We recorded patients’ age, gender, race, admitting diagnosis(es), length of stay, psychiatric illness, illicit drug use, whether they reported receiving opioid analgesics at the time of hospitalization, whether they were prescribed opioids and/or nonopioid analgesics during their hospitalization, the median and maximum doses of opioids prescribed and dispensed, and whether they were discharged on opioids. The question of illicit drug use was asked of all patients with the exception of those hospitalized in South Korea due to potential legal implications.

Opioid prescribing and receipt of opioids was recorded based upon current provider orders and medication administration records, respectively. Perception of and satisfaction with pain control was assessed with the American Pain Society Patient Outcome Questionnaire–Modified (APS-POQ-Modified).24,25 Versions of this survey have been validated in English as well as in other languages and cultures.26-28 Because hospitalization practices could differ across hospitals and in different countries, we compared patients’ severity of illness by using Charlson comorbidity scores. Consent forms and the APS-POQ were translated into each country’s primary language according to established processes.29 The survey was filled out by having site investigators read questions aloud and by use of a large-font visual analog scale to aid patients’ verbal responses.

Data were collected and managed using a secure, web-based application electronic data capture tool (Research Electronic Data Capture [REDCap], Nashville, Tennessee), hosted at Denver Health.30

Study Size

Preliminary data from the internal medicine units at our institution suggested that 40% of patients without cancer received opioid analgesics during their hospitalization. Assuming 90% power to detect an absolute difference in the proportion of inpatient medical patients who are receiving opioid analgesics during their hospital stay of 17%, a two-sided type 1 error rate of 0.05, six hospitals in the US, and nine hospitals from all other countries, we calculated an initial sample size of 150 patients per site. This sample size was considered feasible for enrollment in a busy inpatient clinical setting. Study end points were to either reach the goal number of patients (150 per site) or the predetermined study end date, whichever came first.

Data Analysis

We generated means with standard deviations (SDs) and medians with interquartile ranges (IQRs) for normally and nonnormally distributed continuous variables, respectively, and frequencies for categorical variables. We used linear mixed modeling for the analysis of continuous variables. For binary outcomes, our data were fitted to a generalized linear mixed model with logit as the link function and a binary distribution. For ordinal variables, specifically patient-reported satisfaction with pain control and the opinion statements, the data were fitted to a generalized linear mixed model with a cumulative logit link and a multinomial distribution. Hospital was included as a random effect in all models to account for patients cared for in the same hospital.

Country of origin, dichotomized as US or non-US, was the independent variable of interest for all models. An interaction term for exposure to opioids prior to admission and country was entered into all models to explore whether differences in the effect of country existed for patients who reported taking opioids prior to admission and those who did not.

The models for the frequency with which analgesics were given, doses of opioids given during hospitalization and at discharge, patient-reported pain score, and patient-reported satisfaction with pain control were adjusted for (1) age, (2) gender, (3) Charlson Comorbidity Index, (4) length of stay, (5) history of illicit drug use, (6) history of psychiatric illness, (7) daily dose in morphine milligram equivalents (MME) for opioids prior to admission, (8) average pain score, and (9) hospital. The patient-reported satisfaction with pain control model was also adjusted for whether or not opioids were given to the patient during their hospitalization. P < .05 was considered to indicate significance. All analyses were performed using SAS Enterprise Guide 7.1 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina). We reported data on medications that were prescribed and dispensed (as opposed to just prescribed and not necessarily given). Opioids prescribed at discharge represented the total possible opioids that could be given based upon the order/prescription (eg, oxycodone 5 mg every 6 hours as needed for pain would be counted as 20 mg/24 hours maximum possible dose followed by conversion to MME).

Missing Data

When there were missing data, a query was sent to sites to verify if the data were retrievable. If retrievable, the data were then entered. Data were missing in 5% and 2% of patients who did or did not report taking an opioid prior to admission, respectively. If a variable was included in a specific statistical test, then subjects with missing data were excluded from that analysis (ie, complete case analysis).

RESULTS

We approached 1,309 eligible patients, of which 981 provided informed consent, for a response rate of 75%; 503 from the US and 478 patients from other countries (Figure). In unadjusted analyses, we found no significant differences between US and non-US patients in age (mean age 51, SD 15 vs 59, SD 19; P = .30), race, ethnicity, or Charlson comorbidity index scores (median 2, IQR 1-3 vs 3, IQR 1-4; P = .45). US patients had shorter lengths of stay (median 3 days, IQR 2-4 vs 6 days, IQR 3-11; P = .04), a more frequent history of illicit drug use (33% vs 6%; P = .003), a higher frequency of psychiatric illness (27% vs 8%; P < .0001), and more were receiving opioid analgesics prior to admission (38% vs 17%; P = .007) than those hospitalized in other countries (Table 1, Appendix 1). The primary admitting diagnoses for all patients in the study are listed in Appendix 2. Opioid prescribing practices across the individual sites are shown in Appendix 3.

Patients Taking Opioids Prior to Admission

After adjusting for relevant covariates, we found that more patients in the US were given opioids during their hospitalization and in higher doses than patients from other countries and more were prescribed opioids at discharge. Fewer patients in the US were dispensed nonopioid analgesics during their hospitalization than patients from other countries, but this difference was not significant (Table 2). Appendix 4 shows the types of nonopioid pain medications prescribed in the US and other countries.

After adjustment for relevant covariates, US patients reported greater pain severity at the time they completed their pain surveys. We found no significant difference in satisfaction with pain control between patients from the US and other countries in the models, regardless of whether we included average pain score or opioid receipt during hospitalization in the model (Table 3).

In unadjusted analyses, compared with patients hospitalized in other countries, more patients in the US stated that they would like a stronger dose of analgesic if they were still in pain, though the difference was nonsignificant, and US patients were more likely to agree with the statement that people become addicted to pain medication easily and less likely to agree with the statement that it is easier to endure pain than deal with the side effects of pain medications (Table 3).

Patients Not Taking Opioids Prior to Admission

After adjusting for relevant covariates, we found no significant difference in the proportion of US patients provided with nonopioid pain medications during their hospitalization compared with patients in other countries, but a greater percentage of US patients were given opioids during their hospitalization and at discharge and in higher doses (Table 2).

After adjusting for relevant covariates, US patients reported greater pain severity at the time they completed their pain surveys and greater pain severity in the 24-36 hours prior to completing the survey than patients from other countries, but we found no difference in patient satisfaction with pain control (Table 3). After we included the average pain score and whether or not opioids were given to the patient during their hospitalization in this model, patients in the US were more likely to report a higher level of satisfaction with pain control than patients in all other countries (P = .001).

In unadjusted analyses, compared with patients hospitalized in other countries, those in the US were less likely to agree with the statement that good patients avoid talking about pain (Table 3).

Patient Satisfaction and Opioid Receipt

Among patients cared for in the US, after controlling for the average pain score, we did not find a significant association between receiving opioids while in the hospital and satisfaction with pain control for patients who either did or did not endorse taking opioids prior to admission (P = .38 and P = .24, respectively). Among patients cared for in all other countries, after controlling for the average pain score, we found a significant association between receiving opioids while in the hospital and a lower level of satisfaction with pain control for patients who reported taking opioids prior to admission (P = .02) but not for patients who did not report taking opioids prior to admission (P = .08).

DISCUSSION

Compared with patients hospitalized in other countries, a greater percentage of those hospitalized in the US were prescribed opioid analgesics both during hospitalization and at the time of discharge, even after adjustment for pain severity. In addition, patients hospitalized in the US reported greater pain severity at the time they completed their pain surveys and in the 24 to 36 hours prior to completing the survey than patients from other countries. In this sample, satisfaction, beliefs, and expectations about pain control differed between patients in the US and other sites. Our study also suggests that opioid receipt did not lead to improved patient satisfaction with pain control.

The frequency with which we observed opioid analgesics being prescribed during hospitalization in US hospitals (79%) was higher than the 51% of patients who received opioids reported by Herzig and colleagues.10 Patients in our study had a higher prevalence of illicit drug abuse and psychiatric illness, and our study only included patients who reported pain at some point during their hospitalization. We also studied prescribing practices through analysis of provider orders and medication administration records at the time the patient was hospitalized.

While we observed that physicians in the US more frequently prescribed opioid analgesics during hospitalizations than physicians working in other countries, we also observed that patients in the US reported higher levels of pain during their hospitalization. After adjusting for a number of variables, including pain severity, however, we still found that opioids were more commonly prescribed during hospitalizations by physicians working in the US sites studied than by physicians in the non-US sites.

Opioid prescribing practices varied across the sites sampled in our study. While the US sites, Taiwan, and Korea tended to be heavier utilizers of opioids during hospitalization, there were notable differences in discharge prescribing of opioids, with the US sites more commonly prescribing opioids and higher MME for patients who did not report taking opioids prior to their hospitalization (Appendix 3). A sensitivity analysis was conducted excluding South Korea from modeling, given that patients there were not asked about illicit opioid use. There were no important changes in the magnitude or direction of the results.

Our study supports previous studies indicating that there are cultural and societal differences when it comes to the experience of pain and the expectations around pain control.17,20-22,31 Much of the focus on reducing opioid utilization has been on provider practices32 and on prescription drug monitoring programs.33 Our findings suggest that another area of focus that may be important in mitigating the opioid epidemic is patient expectations of pain control.

Our study has a number of strengths. First, we included 11 hospitals from eight different countries. Second, we believe this is the first study to assess opioid prescribing and dispensing practices during hospitalization as well as at the time of discharge. Third, patient perceptions of pain control were assessed in conjunction with analgesic prescribing and were assessed during hospitalization. Fourth, we had high response rates for patient participation in our study. Fifth, we found much larger differences in opioid prescribing than anticipated, and thus, while we did not achieve the sample size originally planned for either the number of hospitals or patients enrolled per hospital, we were sufficiently powered. This is likely secondary to the fact that the population we studied was one that specifically reported pain, resulting in the larger differences seen.

Our study also had a number of limitations. First, the prescribing practices in countries other than the US are represented by only one hospital per country and, in some countries, by limited numbers of patients. While we studied four sites in the US, we did not have a site in the Northeast, a region previously shown to have lower prescribing rates.10 Additionally, patient samples for the US sites compared with the sites in other countries varied considerably with respect to ethnicity. While some studies in US patients have shown that opioid prescribing may vary based on race/ethnicity,34 we are uncertain as to how this might impact a study that crosses multiple countries. We also had a low number of patients receiving opioids prior to hospitalization for several of the non-US countries, which reduced the power to detect differences in this subgroup. Previous research has shown that there are wide variations in prescribing practices even within countries;10,12,18 therefore, caution should be taken when generalizing our findings. Second, we assessed analgesic prescribing patterns and pain control during the first 24 to 36 hours of hospitalization and did not consider hospital days beyond this timeframe with the exception of noting what medications were prescribed at discharge. We chose this methodology in an attempt to eliminate as many differences that might exist in the duration of hospitalization across many countries. Third, investigators in the study administered the survey, and respondents may have been affected by social desirability bias in how the survey questions were answered. Because investigators were not a part of the care team of any study patients, we believe this to be unlikely. Fourth, our study was conducted from October 8, 2013 to August 31, 2015 and the opioid epidemic is dynamic. Accordingly, our data may not reflect current opioid prescribing practices or patients’ current beliefs regarding pain control. Fifth, we did not collect demographic data on the patients who did not participate and could not look for systematic differences between participants and nonparticipants. Sixth, we relied on patients to self-report whether they were taking opioids prior to hospitalization or using illicit drugs. Seventh, we found comorbid mental health conditions to be more frequent in the US population studied. Previous work has shown regional variation in mental health conditions,35,36 which could have affected our findings. To account for this, our models included psychiatric illness.

CONCLUSIONS

Our data suggest that physicians in the US may prescribe opioids more frequently during patients’ hospitalizations and at discharge than their colleagues in other countries. We also found that patient satisfaction, beliefs, and expectations about pain control differed between patients in the US and other sites. Although the small number of hospitals included in our sample coupled with the small sample size in some of the non-US countries limits the generalizability of our findings, the data suggest that reducing the opioid epidemic in the US may require addressing patients’ expectations regarding pain control in addition to providers’ inpatient analgesic prescribing patterns.

Disclosures

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Funding

The authors report no funding source for this work.

1. Pletcher MJ, Kertesz SG, Kohn MA, Gonzales R. Trends in opioid prescribing by race/ethnicity for patients seeking care in US emergency departments. JAMA. 2008;299(1):70-78. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2007.64.

2. Herzig SJ. Growing concerns regarding long-term opioid use: the hospitalization hazard. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(7):469-470. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2369.

3. Guy GP Jr, Zhang K, Bohm MK, et al. Vital Signs: changes in opioid prescribing in the United States, 2006–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(26):697-704. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6626a4.

4. Okie S. A flood of opioids, a rising tide of deaths. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(21):1981-1985. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1011512.

5. Liang Y, Turner BJ. National cohort study of opioid analgesic dose and risk of future hospitalization. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(7):425-431. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2350.

6. Han B, Compton WM, Blanco C, et al. Prescription opioid use, misuse, and use disorders in U.S. Adults: 2015 national survey on drug use and health. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(5):293-301. https://doi.org/10.7326/M17-0865.

7. Schuchat A, Houry D, Guy GP, Jr. New data on opioid use and prescribing in the United States. JAMA. 2017;318(5):425-426. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.8913.

8. Sawyer J, Haslam L, Robinson S, Daines P, Stilos K. Pain prevalence study in a large Canadian teaching hospital. Pain Manag Nurs. 2008;9(3):104-112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmn.2008.02.001.

9. Gupta A, Daigle S, Mojica J, Hurley RW. Patient perception of pain care in hospitals in the United States. J Pain Res. 2009;2:157-164. https://doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S7903.

10. Herzig SJ, Rothberg MB, Cheung M, Ngo LH, Marcantonio ER. Opioid utilization and opioid-related adverse events in nonsurgical patients in US hospitals. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(2):73-81. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2102.

11. Kanjanarat P, Winterstein AG, Johns TE, et al. Nature of preventable adverse drug events in hospitals: a literature review. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2003;60(17):1750-1759. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajhp/60.17.1750.

12. Jena AB, Goldman D, Karaca-Mandic P. Hospital prescribing of opioids to medicare beneficiaries. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(7):990-997. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.2737.

13. Hooten WM, St Sauver JL, McGree ME, Jacobson DJ, Warner DO. Incidence and risk factors for progression From short-term to episodic or long-term opioid prescribing: A population-based study. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(7):850-856. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.04.012.

14. Alam A, Gomes T, Zheng H, et al. Long-term analgesic use after low-risk surgery: a retrospective cohort study. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(5):425-430. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2011.1827.

15. Barnett ML, Olenski AR, Jena AB. Opioid-prescribing patterns of emergency physicians and risk of long-term use. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(7):663-673. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa1610524.

16. Calcaterra SL, Scarbro S, Hull ML, et al. Prediction of future chronic opioid use Among hospitalized patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(6):898-905. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4335-8.

17. Callister LC. Cultural influences on pain perceptions and behaviors. Home Health Care Manag Pract. 2003;15(3):207-211. https://doi.org/10.1177/1084822302250687.

18. Paulozzi LJ, Mack KA, Hockenberry JM. Vital signs: Variation among states in prescribing of opioid pain relievers and benzodiazepines--United States, 2012. J Saf Res. 2014;63(26):563-568. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsr.2014.09.001.

19. Callister LC, Khalaf I, Semenic S, Kartchner R, Vehvilainen-Julkunen K. The pain of childbirth: perceptions of culturally diverse women. Pain Manag Nurs. 2003;4(4):145-154. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1524-9042(03)00028-6.

20. Moore R, Brødsgaard I, Mao TK, Miller ML, Dworkin SF. Perceived need for local anesthesia in tooth drilling among Anglo-Americans, Chinese, and Scandinavians. Anesth Prog. 1998;45(1):22-28.

21. Kankkunen PM, Vehviläinen-Julkunen KM, Pietilä AM, et al. A tale of two countries: comparison of the perceptions of analgesics among Finnish and American parents. Pain Manag Nurs. 2008;9(3):113-119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmn.2007.12.003.

22. Hanoch Y, Katsikopoulos KV, Gummerum M, Brass EP. American and German students’ knowledge, perceptions, and behaviors with respect to over-the-counter pain relievers. Health Psychol. 2007;26(6):802-806. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.26.6.802.

23. Manjiani D, Paul DB, Kunnumpurath S, Kaye AD, Vadivelu N. Availability and utilization of opioids for pain management: global issues. Ochsner J. 2014;14(2):208-215.

24. Quality improvement guidelines for the treatment of acute pain and cancer pain. JAMA. 1995;274(23):1874-1880.

25. McNeill JA, Sherwood GD, Starck PL, Thompson CJ. Assessing clinical outcomes: patient satisfaction with pain management. J Pain Symptom Manag. 1998;16(1):29-40. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0885-3924(98)00034-7.

26. Ferrari R, Novello C, Catania G, Visentin M. Patients’ satisfaction with pain management: the Italian version of the Patient Outcome Questionnaire of the American Pain Society. Recenti Prog Med. 2010;101(7–8):283-288.

27. Malouf J, Andión O, Torrubia R, Cañellas M, Baños JE. A survey of perceptions with pain management in Spanish inpatients. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2006;32(4):361-371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.05.006.

28. Gordon DB, Polomano RC, Pellino TA, et al. Revised American Pain Society Patient Outcome Questionnaire (APS-POQ-R) for quality improvement of pain management in hospitalized adults: preliminary psychometric evaluation. J Pain. 2010;11(11):1172-1186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2010.02.012.

29. Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, Ferraz MB. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25(24):3186-3191. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007632-200012150-00014.

30. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377-381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010.

31. Duman F. After surgery in Germany, I wanted Vicodin, not herbal tea. New York Times. January 27, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/01/27/opinion/sunday/surgery-germany-vicodin.html. Accessed November 6, 2018.

32. Beaudoin FL, Banerjee GN, Mello MJ. State-level and system-level opioid prescribing policies: the impact on provider practices and overdose deaths, a systematic review. J Opioid Manag. 2016;12(2):109-118. https://doi.org/10.5055/jom.2016.0322. 33. Bao Y, Wen K, Johnson P, et al. Assessing the impact of state policies for prescription drug monitoring programs on high-risk opioid prescriptions. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(10):1596-1604. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2018.0512.