User login

Rapidly Growing Scalp Nodule

Cutaneous Metastasis of Pulmonary Adenocarcinoma

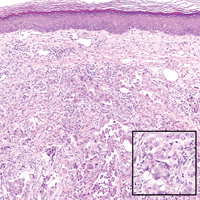

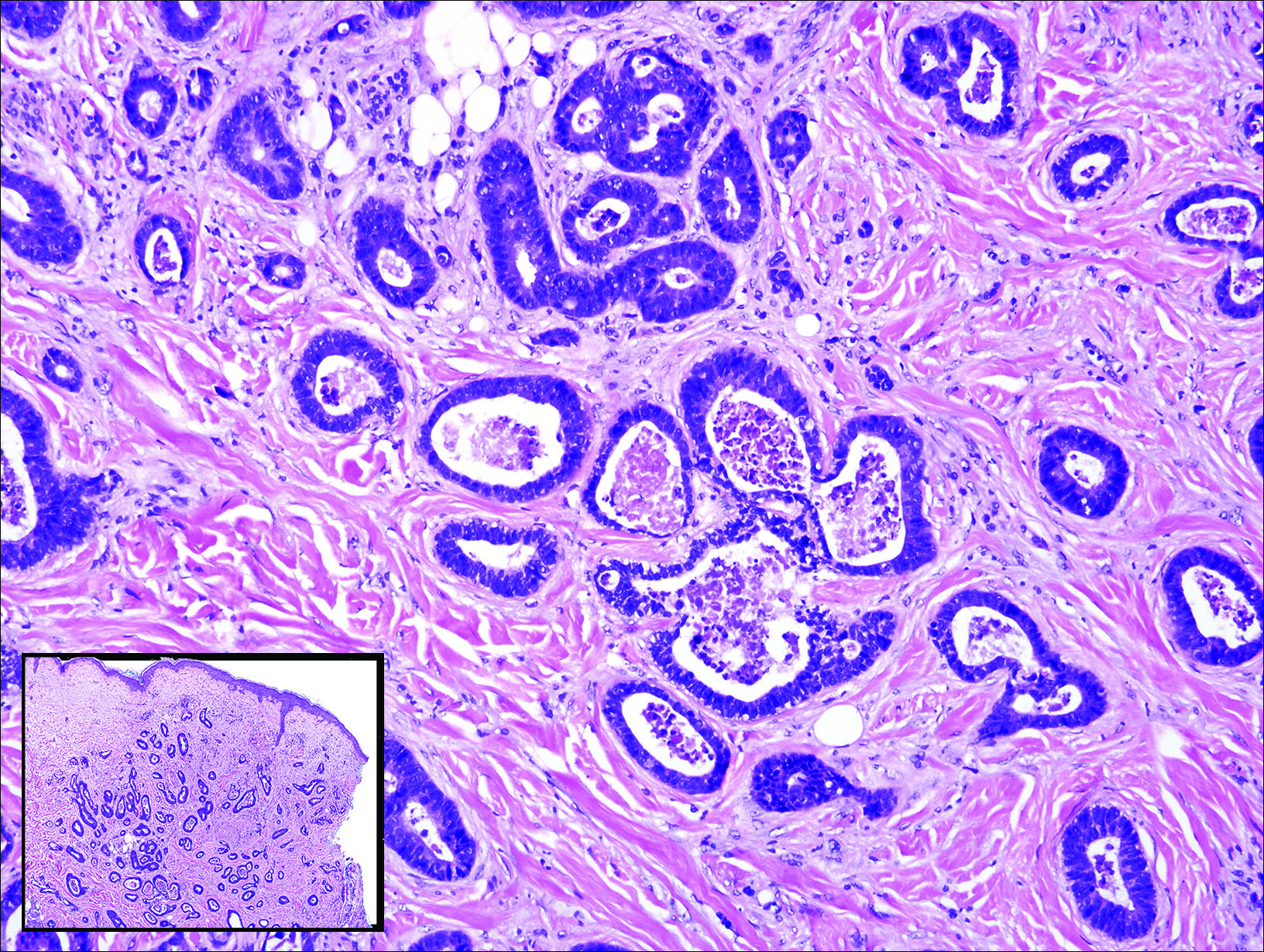

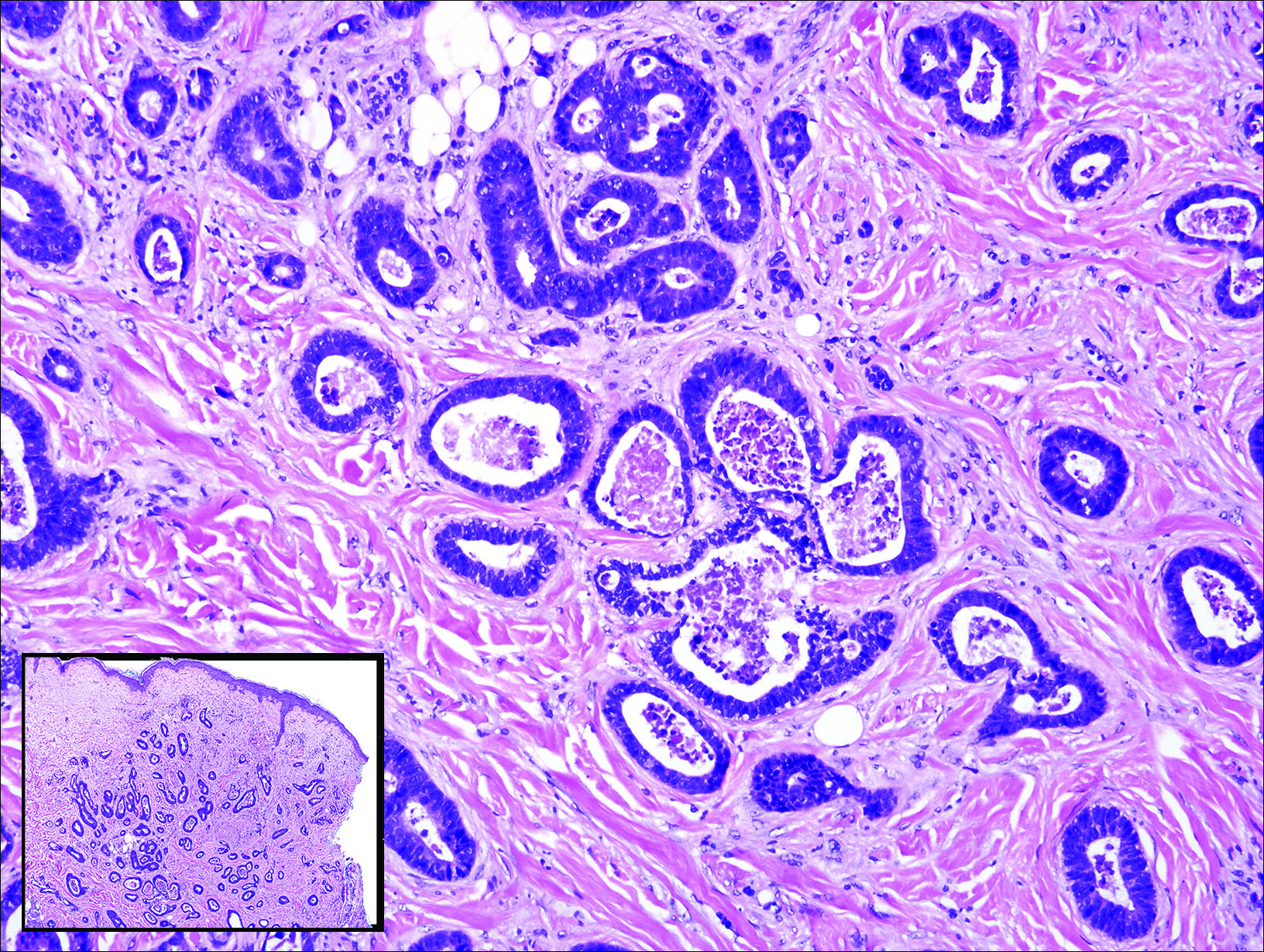

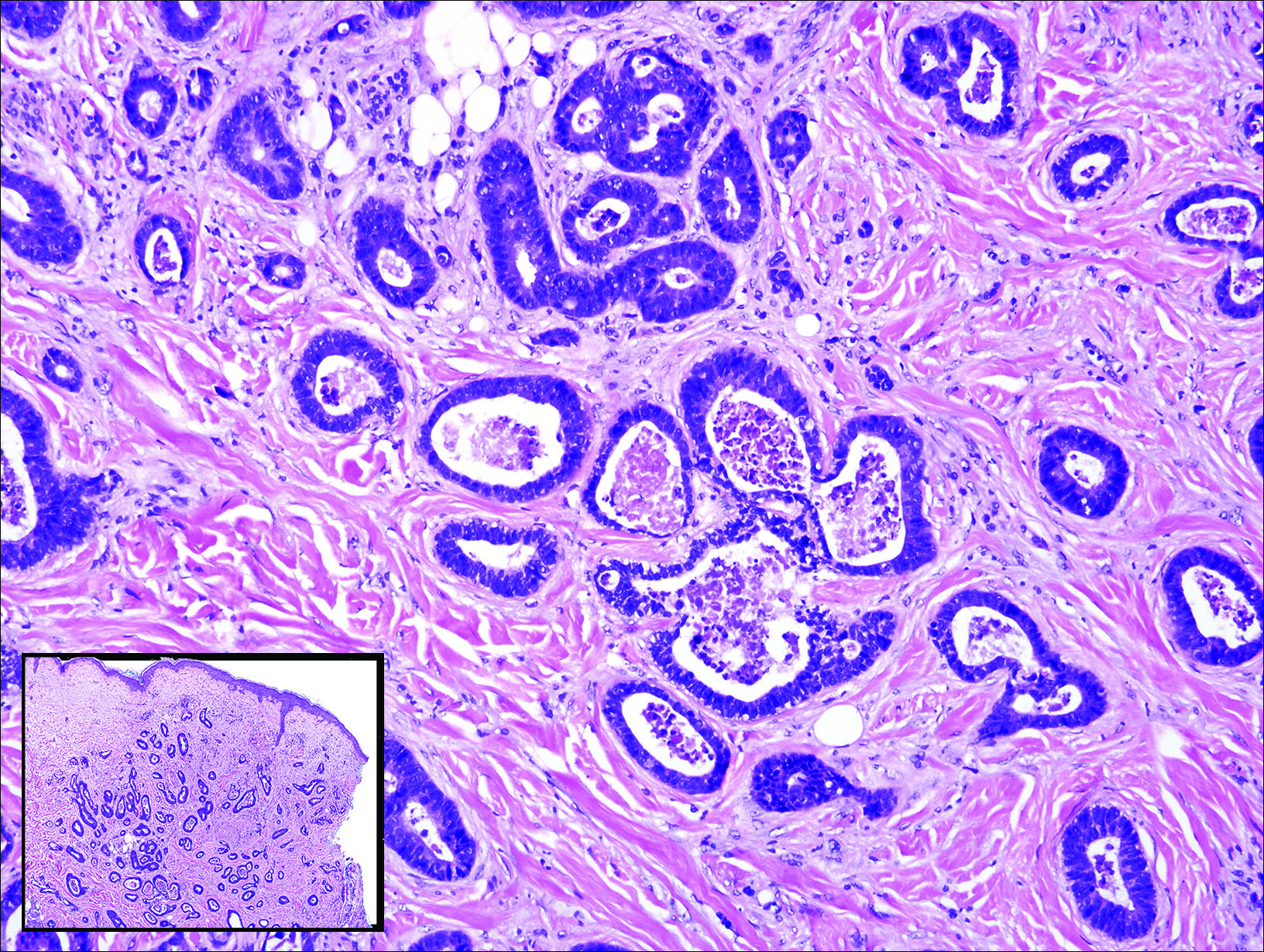

Cutaneous metastasis of pulmonary adenocarcinoma (CMPA) is a rare phenomenon with an overall survival rate of less than 5 months.1,2 Often, CMPA can be the heralding feature of an aggressive systemic malignancy in 2.8% to 22% of reported cases.2-4 Clinically, CMPAs often present as fixed, violaceous, ulcerated nodules on the chest wall, scalp, or site of a prior procedure.3,5,6 Other clinical presentations have been described including zosteriform and inflammatory carcinomalike CMPA and CMPA on the tip of the nose.7 Histologically, CMPA presents as a subdermal collection of atypical glands arranged as clustered aggregates of infiltrative glands penetrating the dermal stroma (quiz image). The atypical glands have large oval nuclei with high nuclear to cytoplasm ratios with scant pale cytoplasm.

Cutaneous metastasis of pulmonary adenocarcinoma is difficult to distinguish from other metastatic or primary glandular malignancies based on histology alone. Immunohistochemical analysis can aid in the diagnosis of the primary tumor. Pulmonary adenocarcinomas are positive for cytokeratin (CK) 7 and thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF-1), and they are negative for CK5/6 and CK20.7 The differential diagnosis for CMPA includes other internal malignancies such as invasive ductal adenocarcinoma of the breast and gastrointestinal adenocarcinomas (eg, gastric or colorectal carcinoma [CRC]). Additionally, endometriosis and primary sebaceous carcinomas can mimic cutaneous metastatic adenocarcinomas.

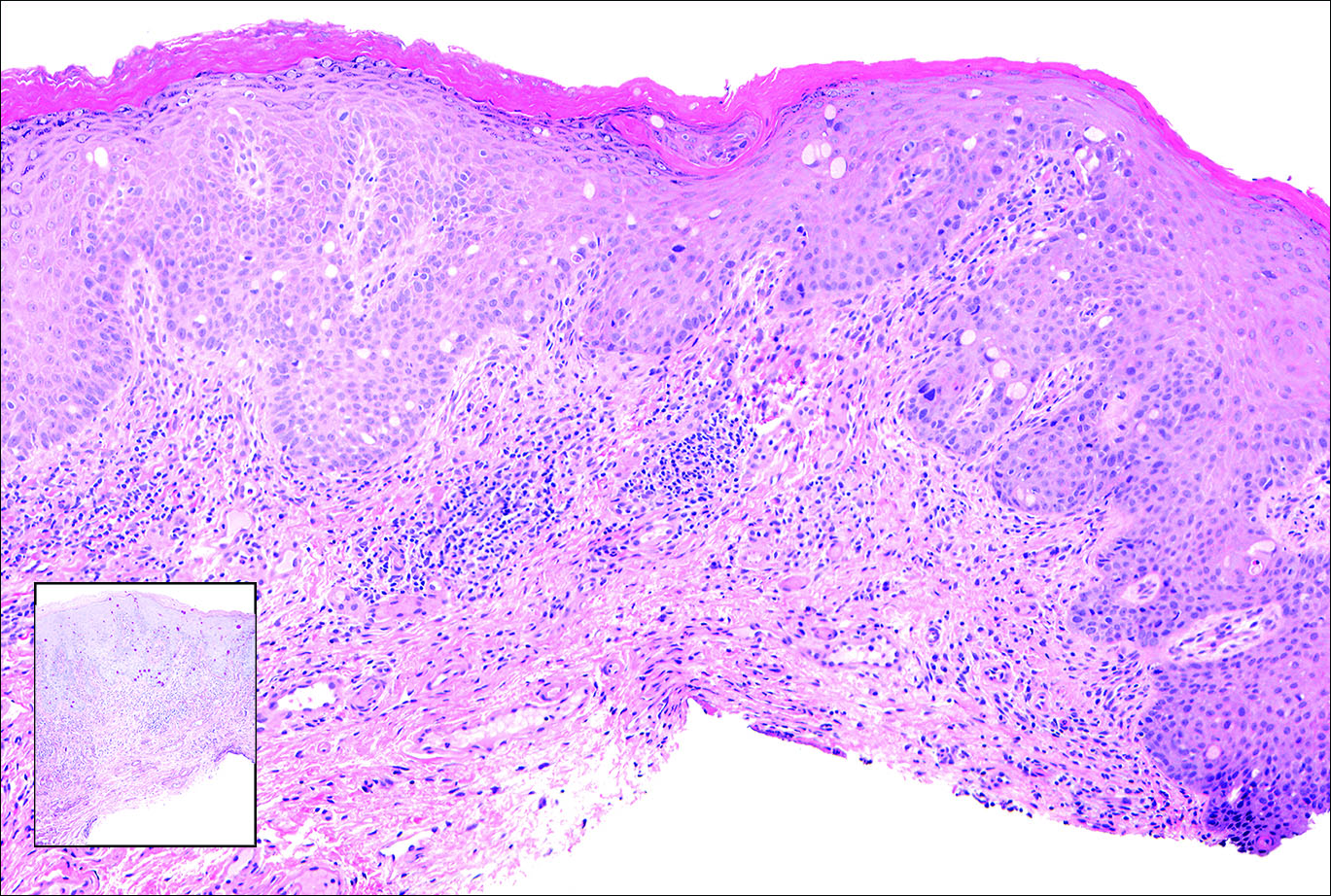

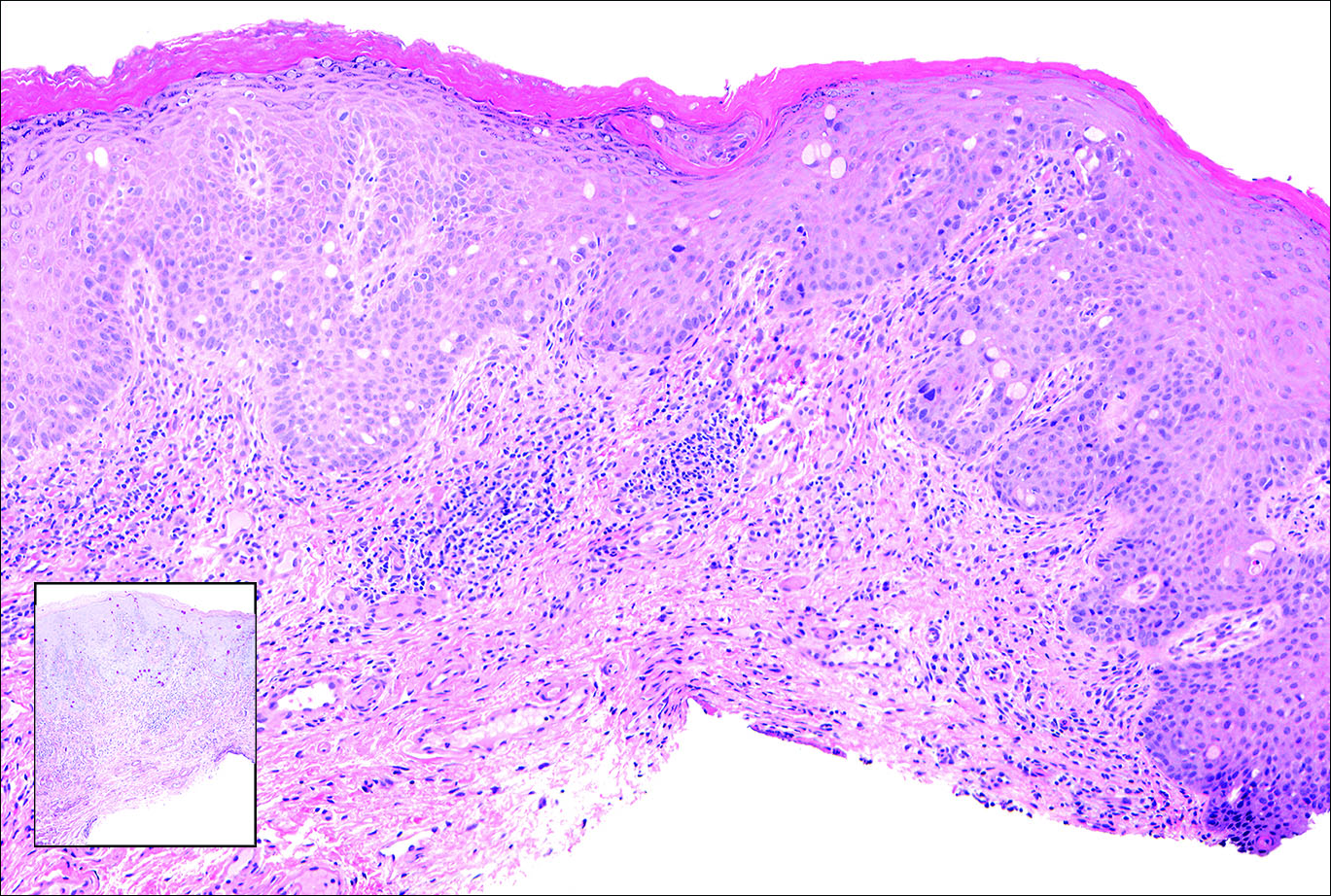

Endometriosis can mimic adenocarcinoma, especially when presenting as a subdermal nodule. However, the scattered dermal glands are cytologically banal and are surrounded by uterine-type stroma and extravasated hemorrhage, a classic presentation of endometriosis (Figure 1).

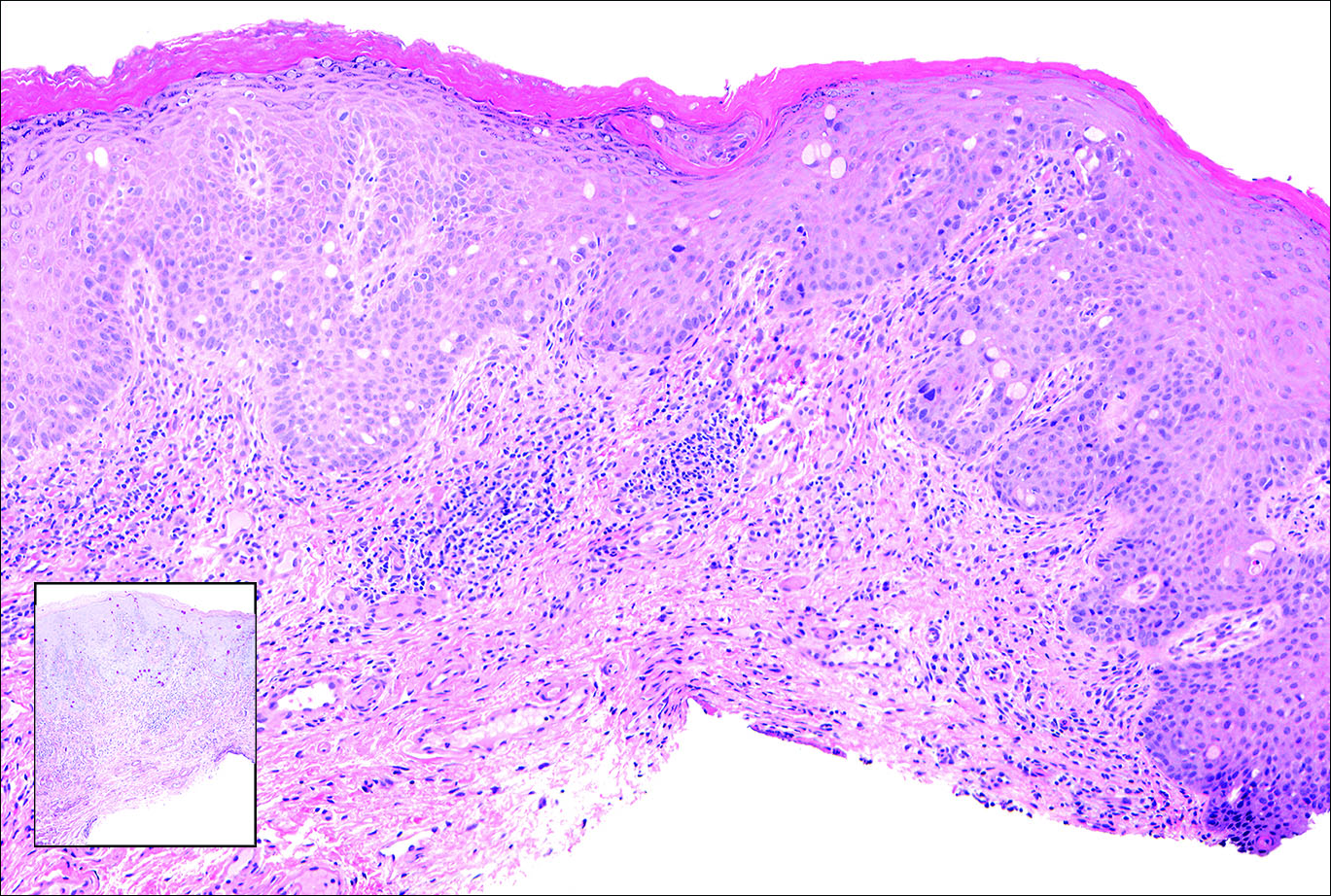

Invasive ductal carcinoma of the breast is one of the most common cutaneous metastases of internal malignancy.3 Clinically, these lesions present on the chest wall or abdomen as flesh-colored nodules. Histopathology generally reveals either tubular or single tumor cells infiltrating the dermis with surrounding desmoplastic fibrosis (Figure 2). Immunohistochemistry typically is positive for CK7, estrogen receptor, and mammaglobin, and negative for CK20, CK5/6, and TTF-1.

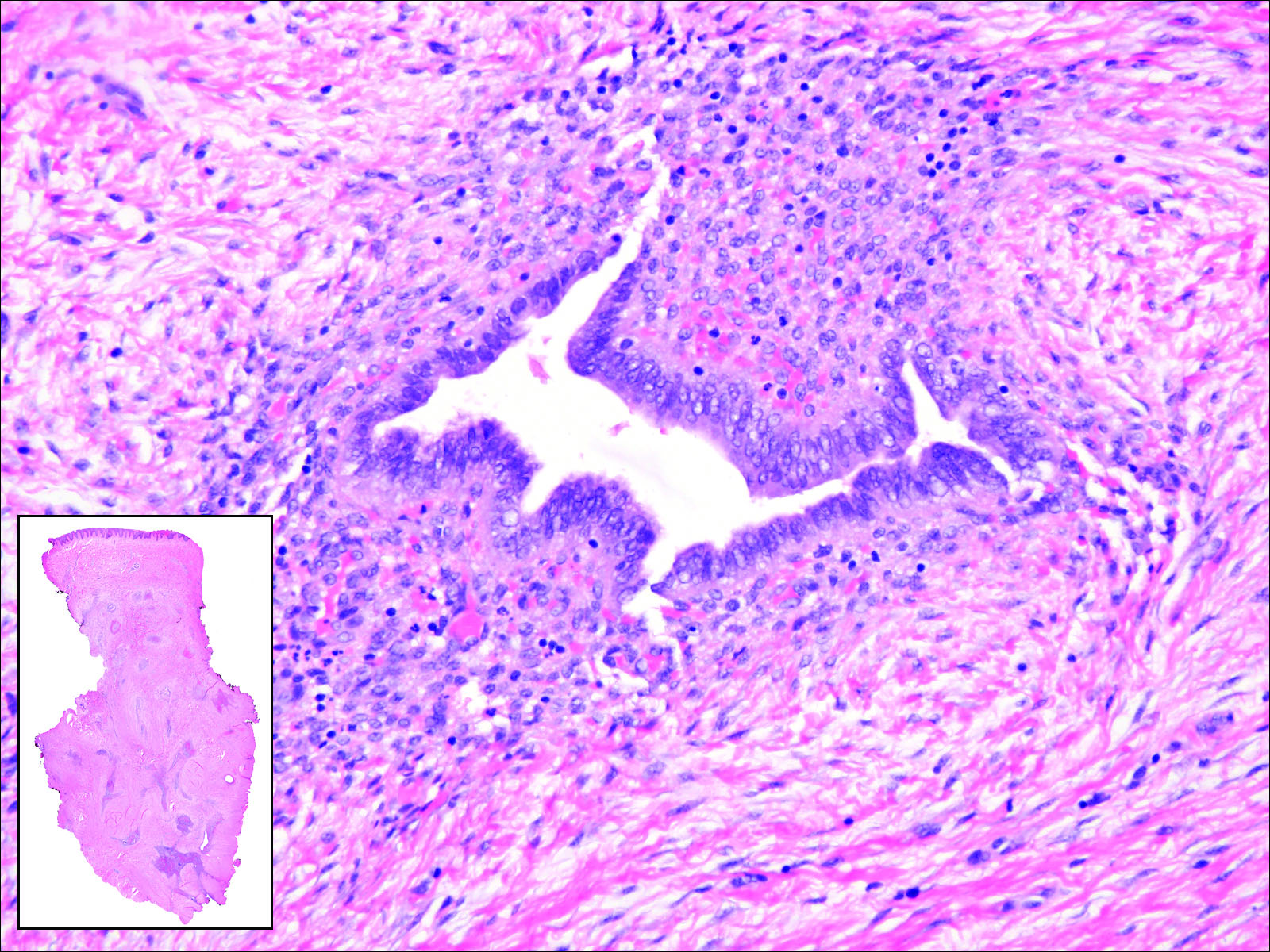

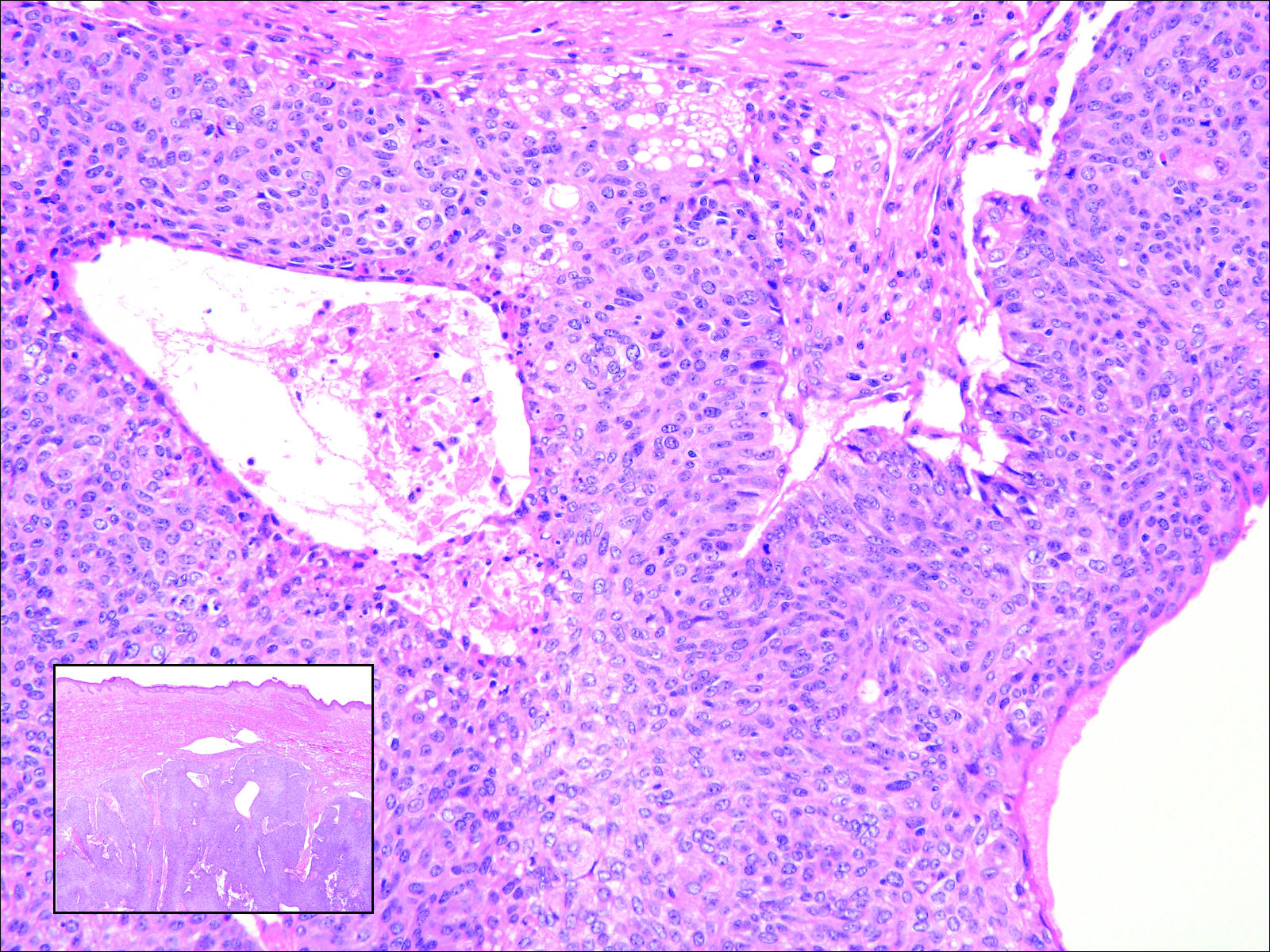

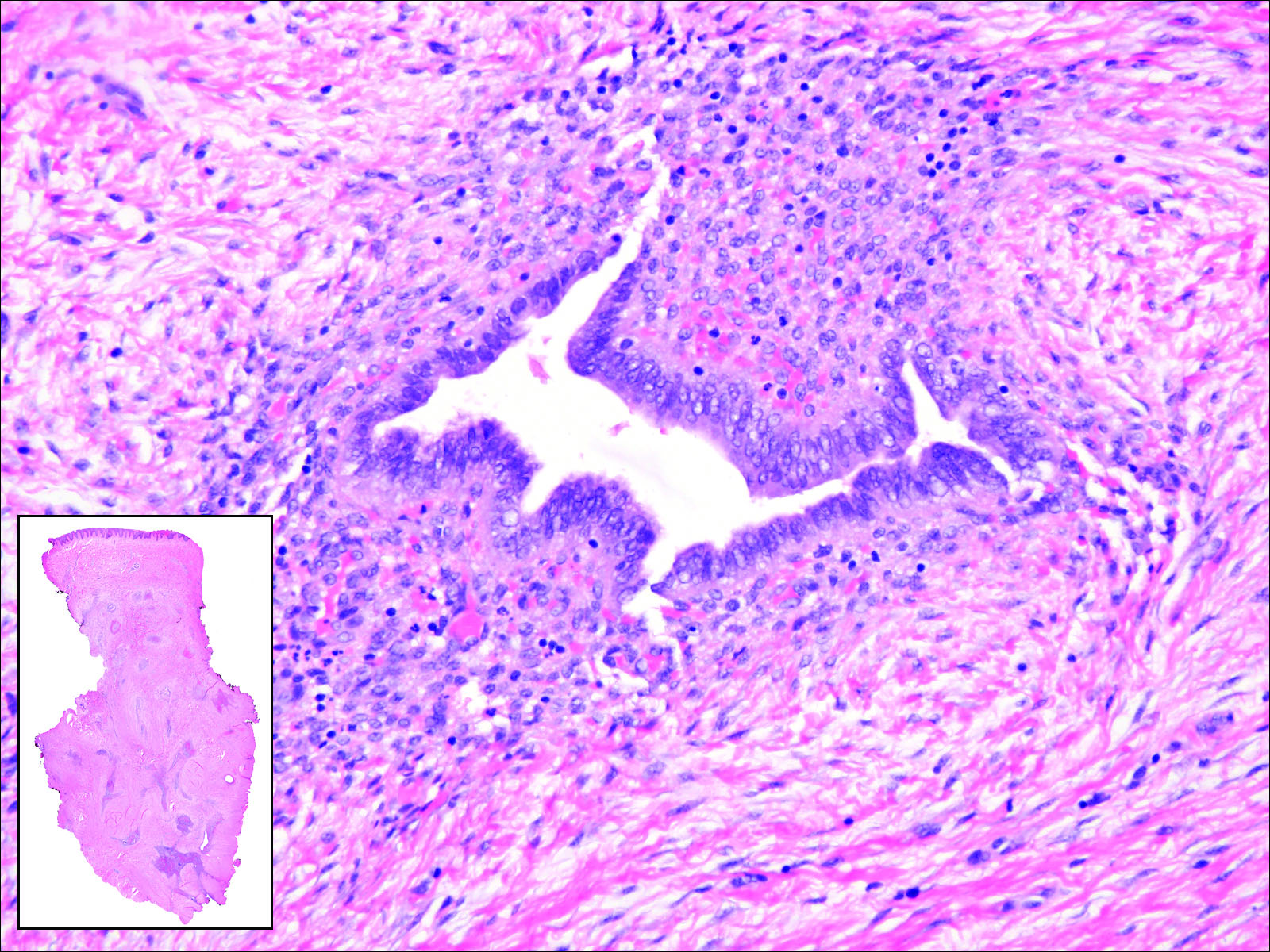

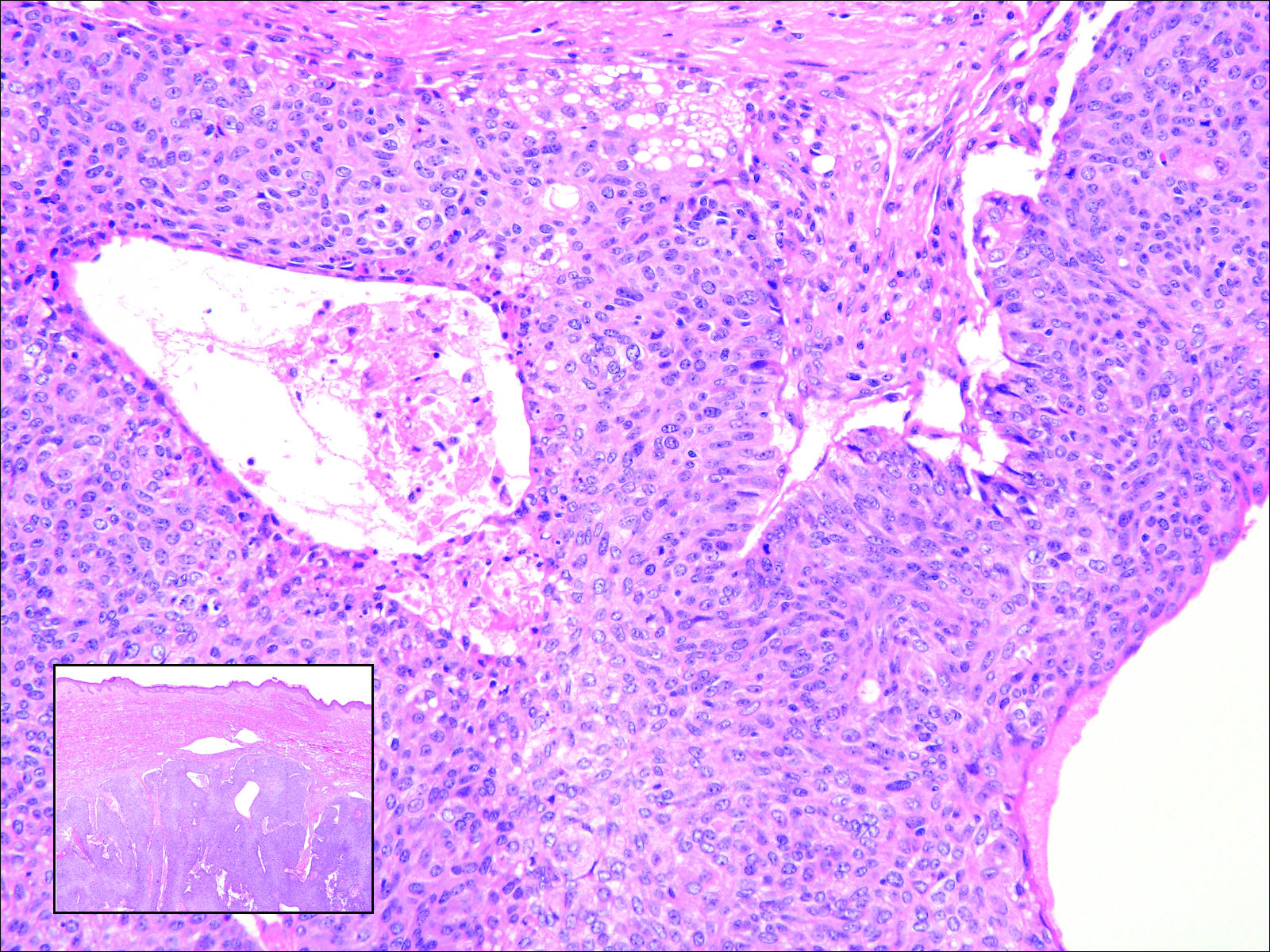

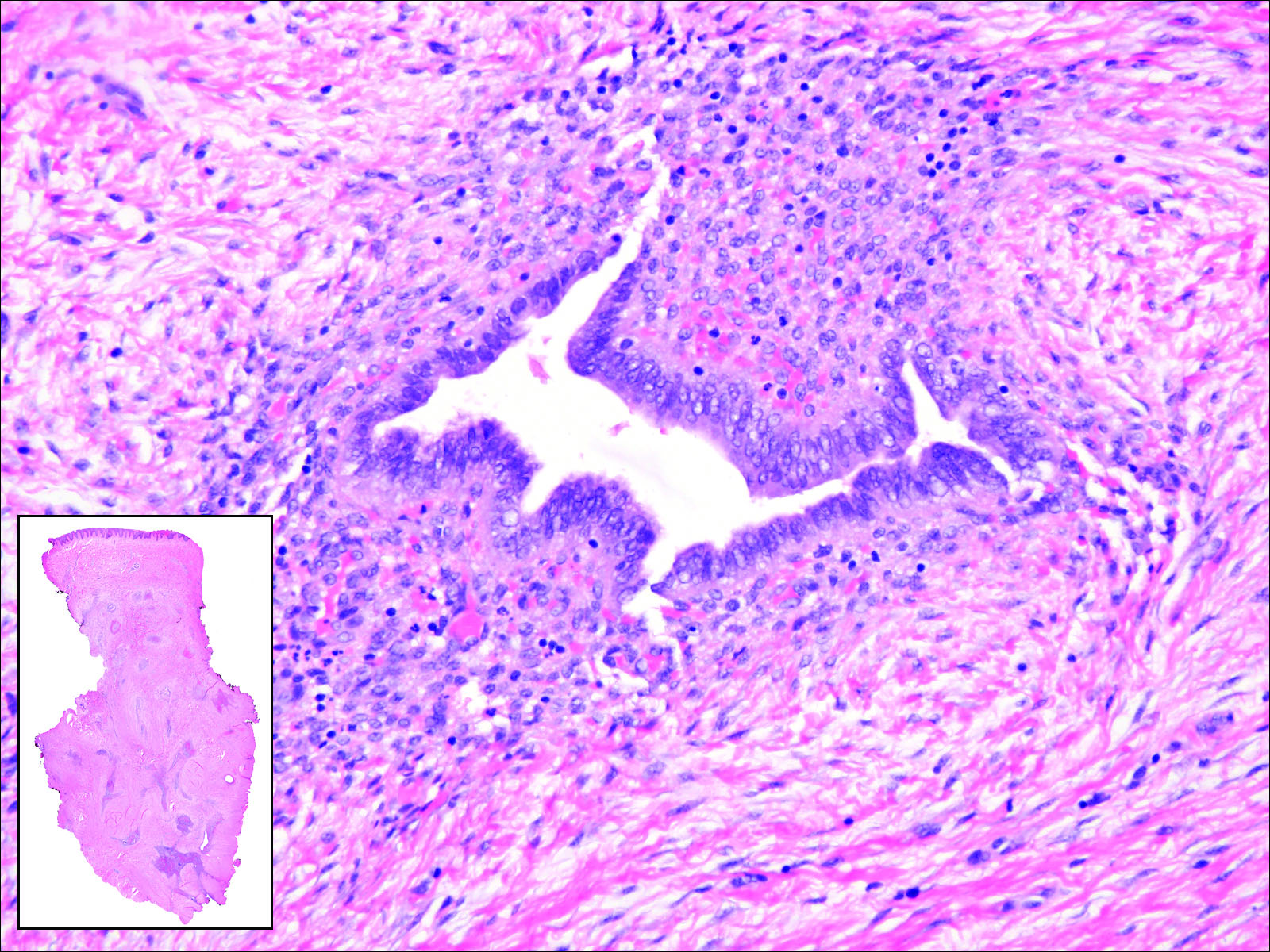

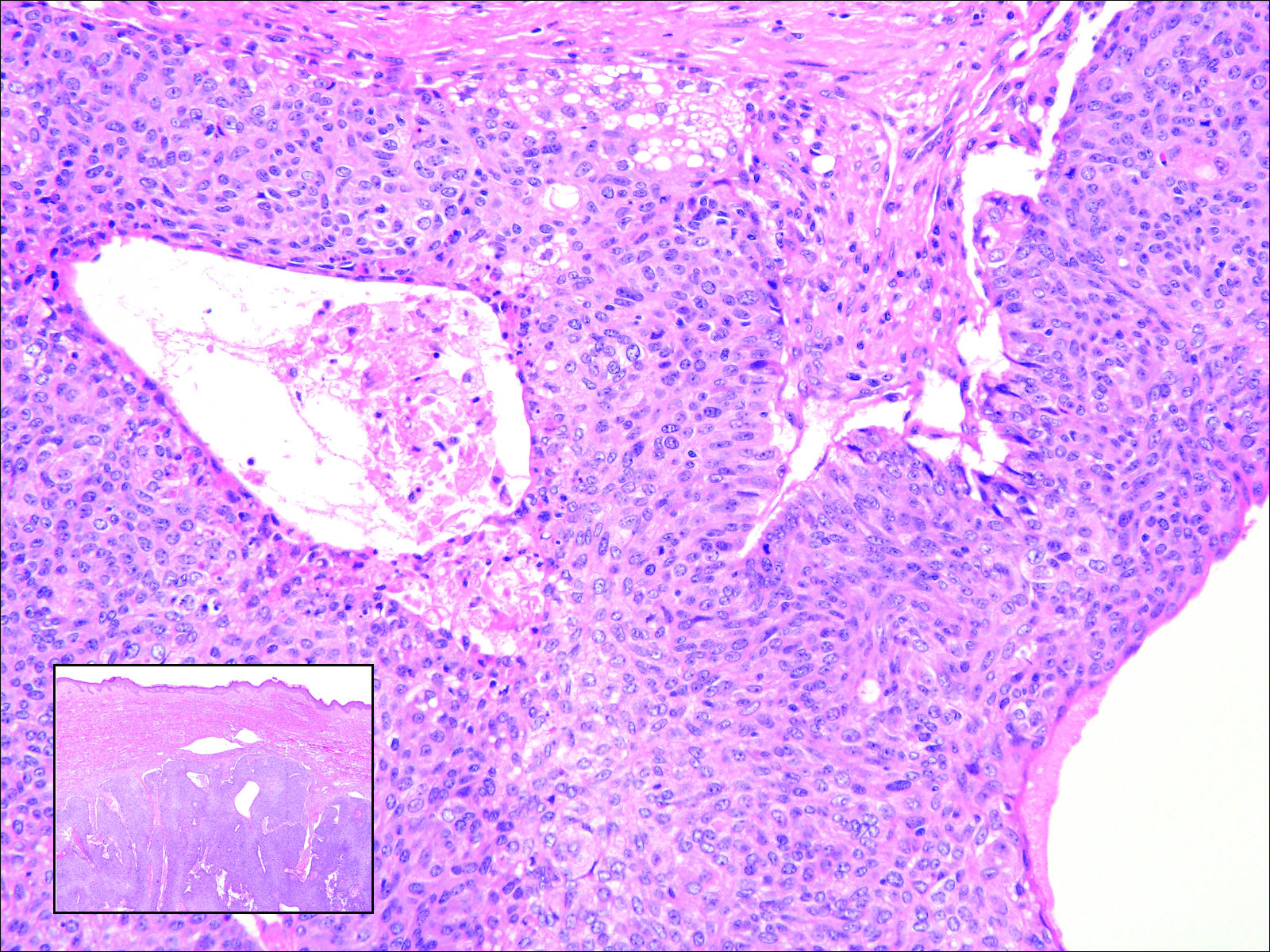

Gastrointestinal adenocarcinomas encompass a variety of primary sites that can metastasize to the skin including CRC. Clinically, cutaneous metastases of CRC present as multiple nodules on the trunk, abdomen, or umbilicus (also known as Sister Mary Joseph nodule).7,8 Distinguishing CRC as the primary site of origin can be difficult; however, there are subtle differences depending on the histologic subtype. In well-differentiated CRCs, well-defined atypical glands are haphazardly arranged within the dermis (Figure 3), while poorly differentiated lesions can present as single cells or with a signet ring-like morphology (Figure 4). For perianal lesions, extramammary Paget disease should be considered when biopsies show large, amphophilic, intraepithelial cells. These lesions often present with mucin and CK20 expression and are frequently associated with colorectal malignancies.9 Another characteristic feature of CRC is central necrosis with karyorrhectic debris, known as dirty necrosis. Immunohistochemical analysis typically shows expression of caudal type homeobox 2 and CK20 with infrequent expression of CK7 and no expression of TTF-1; however, additional clinical history (eg, history of colorectal adenocarcinoma, positive fecal occult blood test) often is the best distinguishing feature.

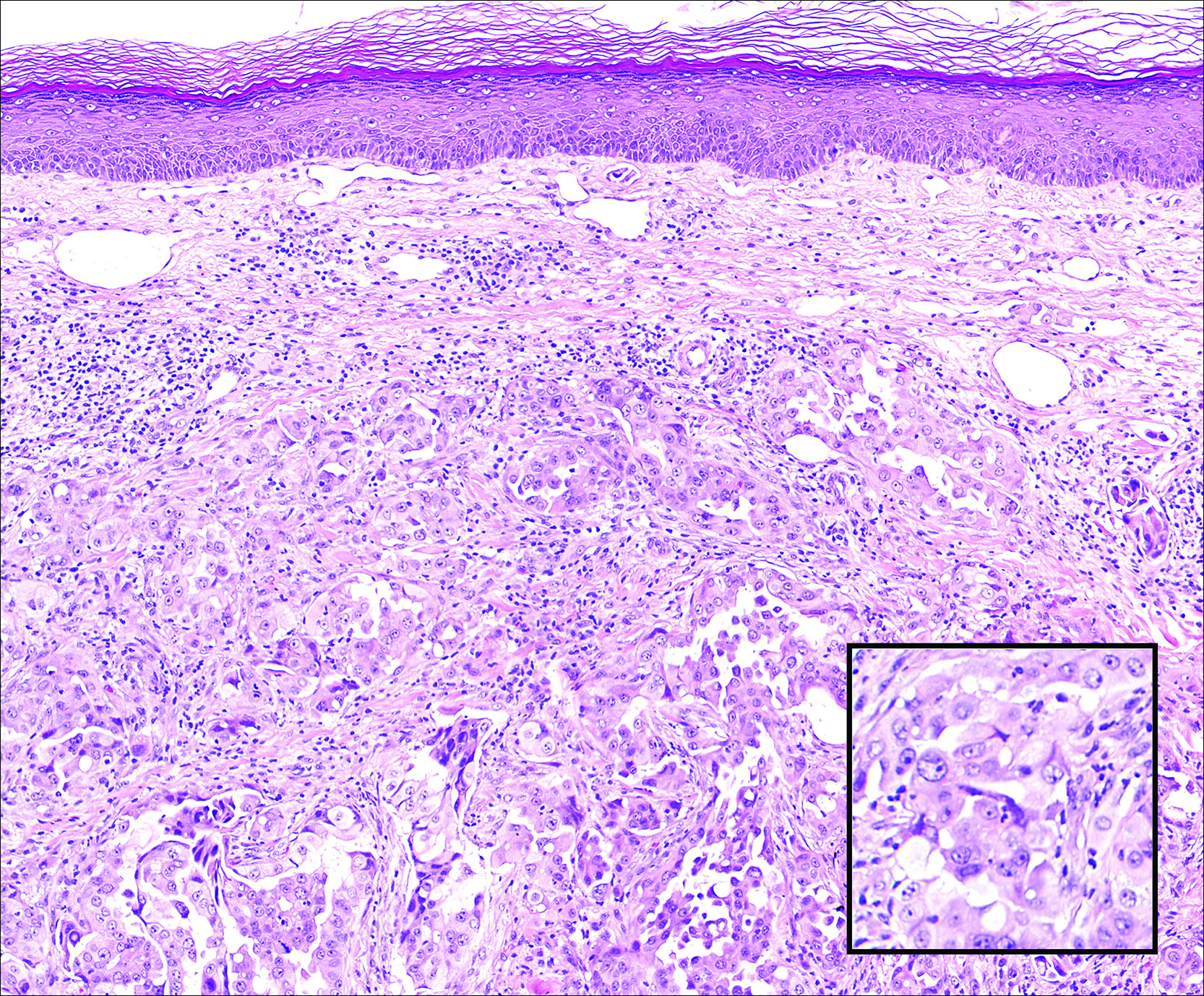

Primary sebaceous carcinoma also can mimic metastatic adenocarcinoma within the skin and is histologically similar to metastatic adenocarcinomas. The most distinguishing feature is sebaceous differentiation characterized by sebocytes, which have a vacuolated cytoplasm giving the nucleus a scalloped appearance, frequently with adjacent ductlike structures (Figure 5). Epidermotropism sometimes is present in sebaceous carcinomas but cannot be relied on as a distinguishing feature. Immunohistochemical analysis also is a helpful tool; these tumors typically are positive for p63 and podoplanin, distinguishing them from negative-staining metastatic adenocarcinomas.10,11

- Terashima T, Kanazawa M. Lung cancer with skin metastasis. Chest. 1994;106:1448-1450.

- Song Z, Lin B, Shao L, et al. Cutaneous metastasis as a initial presentation in advanced non-small cell lung cancer and its poor survival prognosis. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2012;138:1613-1617.

- Lookingbill DP, Spangler N, Helm KF. Cutaneous metastases in patients with metastatic carcinoma: a retrospective study of 4020 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29(2, pt 1):228-236.

- Saeed S, Keehn CA, Morgan MB. Cutaneous metastasis: a clinical, pathological, and immunohistochemical appraisal. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31:419-430.

- Chang SE, Choi JC, Moon KC. A papillary carcinoma: cutaneous metastases from lung cancer. J Dermatol. 2001;28:110-111.

- Snow S, Madjar D, Reizner G, et al. Renal cell carcinoma metastatic to the scalp: case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 2001;27:192-194.

- Alcaraz I, Cerroni L, Rutten A, et al. Cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:347-393.

- Schwartz IS. Sister (Mary?) Joseph's nodule. N Engl J Med. 1987;316:1348-1349.

- Goldblum J, Hart W. Perianal Paget's disease: a histologic and immunohistochemical study of 11 cases with and without associated rectal adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:170-179.

- Ivan D, Nash J, Preito V, et al. Use of p63 expression in distinguishing primary and metastatic cutaneous adnexal neoplasms from metastatic adenocarcinoma to skin. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;34:474-480.

- Liang H, Wu H, Giorgadze T, et al. Podoplanin is a highly sensitive and specific marker to distinguish primary skin adnexal carcinomas from adenocarcinomas metastatic to skin. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:304-310.

Cutaneous Metastasis of Pulmonary Adenocarcinoma

Cutaneous metastasis of pulmonary adenocarcinoma (CMPA) is a rare phenomenon with an overall survival rate of less than 5 months.1,2 Often, CMPA can be the heralding feature of an aggressive systemic malignancy in 2.8% to 22% of reported cases.2-4 Clinically, CMPAs often present as fixed, violaceous, ulcerated nodules on the chest wall, scalp, or site of a prior procedure.3,5,6 Other clinical presentations have been described including zosteriform and inflammatory carcinomalike CMPA and CMPA on the tip of the nose.7 Histologically, CMPA presents as a subdermal collection of atypical glands arranged as clustered aggregates of infiltrative glands penetrating the dermal stroma (quiz image). The atypical glands have large oval nuclei with high nuclear to cytoplasm ratios with scant pale cytoplasm.

Cutaneous metastasis of pulmonary adenocarcinoma is difficult to distinguish from other metastatic or primary glandular malignancies based on histology alone. Immunohistochemical analysis can aid in the diagnosis of the primary tumor. Pulmonary adenocarcinomas are positive for cytokeratin (CK) 7 and thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF-1), and they are negative for CK5/6 and CK20.7 The differential diagnosis for CMPA includes other internal malignancies such as invasive ductal adenocarcinoma of the breast and gastrointestinal adenocarcinomas (eg, gastric or colorectal carcinoma [CRC]). Additionally, endometriosis and primary sebaceous carcinomas can mimic cutaneous metastatic adenocarcinomas.

Endometriosis can mimic adenocarcinoma, especially when presenting as a subdermal nodule. However, the scattered dermal glands are cytologically banal and are surrounded by uterine-type stroma and extravasated hemorrhage, a classic presentation of endometriosis (Figure 1).

Invasive ductal carcinoma of the breast is one of the most common cutaneous metastases of internal malignancy.3 Clinically, these lesions present on the chest wall or abdomen as flesh-colored nodules. Histopathology generally reveals either tubular or single tumor cells infiltrating the dermis with surrounding desmoplastic fibrosis (Figure 2). Immunohistochemistry typically is positive for CK7, estrogen receptor, and mammaglobin, and negative for CK20, CK5/6, and TTF-1.

Gastrointestinal adenocarcinomas encompass a variety of primary sites that can metastasize to the skin including CRC. Clinically, cutaneous metastases of CRC present as multiple nodules on the trunk, abdomen, or umbilicus (also known as Sister Mary Joseph nodule).7,8 Distinguishing CRC as the primary site of origin can be difficult; however, there are subtle differences depending on the histologic subtype. In well-differentiated CRCs, well-defined atypical glands are haphazardly arranged within the dermis (Figure 3), while poorly differentiated lesions can present as single cells or with a signet ring-like morphology (Figure 4). For perianal lesions, extramammary Paget disease should be considered when biopsies show large, amphophilic, intraepithelial cells. These lesions often present with mucin and CK20 expression and are frequently associated with colorectal malignancies.9 Another characteristic feature of CRC is central necrosis with karyorrhectic debris, known as dirty necrosis. Immunohistochemical analysis typically shows expression of caudal type homeobox 2 and CK20 with infrequent expression of CK7 and no expression of TTF-1; however, additional clinical history (eg, history of colorectal adenocarcinoma, positive fecal occult blood test) often is the best distinguishing feature.

Primary sebaceous carcinoma also can mimic metastatic adenocarcinoma within the skin and is histologically similar to metastatic adenocarcinomas. The most distinguishing feature is sebaceous differentiation characterized by sebocytes, which have a vacuolated cytoplasm giving the nucleus a scalloped appearance, frequently with adjacent ductlike structures (Figure 5). Epidermotropism sometimes is present in sebaceous carcinomas but cannot be relied on as a distinguishing feature. Immunohistochemical analysis also is a helpful tool; these tumors typically are positive for p63 and podoplanin, distinguishing them from negative-staining metastatic adenocarcinomas.10,11

Cutaneous Metastasis of Pulmonary Adenocarcinoma

Cutaneous metastasis of pulmonary adenocarcinoma (CMPA) is a rare phenomenon with an overall survival rate of less than 5 months.1,2 Often, CMPA can be the heralding feature of an aggressive systemic malignancy in 2.8% to 22% of reported cases.2-4 Clinically, CMPAs often present as fixed, violaceous, ulcerated nodules on the chest wall, scalp, or site of a prior procedure.3,5,6 Other clinical presentations have been described including zosteriform and inflammatory carcinomalike CMPA and CMPA on the tip of the nose.7 Histologically, CMPA presents as a subdermal collection of atypical glands arranged as clustered aggregates of infiltrative glands penetrating the dermal stroma (quiz image). The atypical glands have large oval nuclei with high nuclear to cytoplasm ratios with scant pale cytoplasm.

Cutaneous metastasis of pulmonary adenocarcinoma is difficult to distinguish from other metastatic or primary glandular malignancies based on histology alone. Immunohistochemical analysis can aid in the diagnosis of the primary tumor. Pulmonary adenocarcinomas are positive for cytokeratin (CK) 7 and thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF-1), and they are negative for CK5/6 and CK20.7 The differential diagnosis for CMPA includes other internal malignancies such as invasive ductal adenocarcinoma of the breast and gastrointestinal adenocarcinomas (eg, gastric or colorectal carcinoma [CRC]). Additionally, endometriosis and primary sebaceous carcinomas can mimic cutaneous metastatic adenocarcinomas.

Endometriosis can mimic adenocarcinoma, especially when presenting as a subdermal nodule. However, the scattered dermal glands are cytologically banal and are surrounded by uterine-type stroma and extravasated hemorrhage, a classic presentation of endometriosis (Figure 1).

Invasive ductal carcinoma of the breast is one of the most common cutaneous metastases of internal malignancy.3 Clinically, these lesions present on the chest wall or abdomen as flesh-colored nodules. Histopathology generally reveals either tubular or single tumor cells infiltrating the dermis with surrounding desmoplastic fibrosis (Figure 2). Immunohistochemistry typically is positive for CK7, estrogen receptor, and mammaglobin, and negative for CK20, CK5/6, and TTF-1.

Gastrointestinal adenocarcinomas encompass a variety of primary sites that can metastasize to the skin including CRC. Clinically, cutaneous metastases of CRC present as multiple nodules on the trunk, abdomen, or umbilicus (also known as Sister Mary Joseph nodule).7,8 Distinguishing CRC as the primary site of origin can be difficult; however, there are subtle differences depending on the histologic subtype. In well-differentiated CRCs, well-defined atypical glands are haphazardly arranged within the dermis (Figure 3), while poorly differentiated lesions can present as single cells or with a signet ring-like morphology (Figure 4). For perianal lesions, extramammary Paget disease should be considered when biopsies show large, amphophilic, intraepithelial cells. These lesions often present with mucin and CK20 expression and are frequently associated with colorectal malignancies.9 Another characteristic feature of CRC is central necrosis with karyorrhectic debris, known as dirty necrosis. Immunohistochemical analysis typically shows expression of caudal type homeobox 2 and CK20 with infrequent expression of CK7 and no expression of TTF-1; however, additional clinical history (eg, history of colorectal adenocarcinoma, positive fecal occult blood test) often is the best distinguishing feature.

Primary sebaceous carcinoma also can mimic metastatic adenocarcinoma within the skin and is histologically similar to metastatic adenocarcinomas. The most distinguishing feature is sebaceous differentiation characterized by sebocytes, which have a vacuolated cytoplasm giving the nucleus a scalloped appearance, frequently with adjacent ductlike structures (Figure 5). Epidermotropism sometimes is present in sebaceous carcinomas but cannot be relied on as a distinguishing feature. Immunohistochemical analysis also is a helpful tool; these tumors typically are positive for p63 and podoplanin, distinguishing them from negative-staining metastatic adenocarcinomas.10,11

- Terashima T, Kanazawa M. Lung cancer with skin metastasis. Chest. 1994;106:1448-1450.

- Song Z, Lin B, Shao L, et al. Cutaneous metastasis as a initial presentation in advanced non-small cell lung cancer and its poor survival prognosis. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2012;138:1613-1617.

- Lookingbill DP, Spangler N, Helm KF. Cutaneous metastases in patients with metastatic carcinoma: a retrospective study of 4020 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29(2, pt 1):228-236.

- Saeed S, Keehn CA, Morgan MB. Cutaneous metastasis: a clinical, pathological, and immunohistochemical appraisal. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31:419-430.

- Chang SE, Choi JC, Moon KC. A papillary carcinoma: cutaneous metastases from lung cancer. J Dermatol. 2001;28:110-111.

- Snow S, Madjar D, Reizner G, et al. Renal cell carcinoma metastatic to the scalp: case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 2001;27:192-194.

- Alcaraz I, Cerroni L, Rutten A, et al. Cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:347-393.

- Schwartz IS. Sister (Mary?) Joseph's nodule. N Engl J Med. 1987;316:1348-1349.

- Goldblum J, Hart W. Perianal Paget's disease: a histologic and immunohistochemical study of 11 cases with and without associated rectal adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:170-179.

- Ivan D, Nash J, Preito V, et al. Use of p63 expression in distinguishing primary and metastatic cutaneous adnexal neoplasms from metastatic adenocarcinoma to skin. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;34:474-480.

- Liang H, Wu H, Giorgadze T, et al. Podoplanin is a highly sensitive and specific marker to distinguish primary skin adnexal carcinomas from adenocarcinomas metastatic to skin. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:304-310.

- Terashima T, Kanazawa M. Lung cancer with skin metastasis. Chest. 1994;106:1448-1450.

- Song Z, Lin B, Shao L, et al. Cutaneous metastasis as a initial presentation in advanced non-small cell lung cancer and its poor survival prognosis. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2012;138:1613-1617.

- Lookingbill DP, Spangler N, Helm KF. Cutaneous metastases in patients with metastatic carcinoma: a retrospective study of 4020 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29(2, pt 1):228-236.

- Saeed S, Keehn CA, Morgan MB. Cutaneous metastasis: a clinical, pathological, and immunohistochemical appraisal. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31:419-430.

- Chang SE, Choi JC, Moon KC. A papillary carcinoma: cutaneous metastases from lung cancer. J Dermatol. 2001;28:110-111.

- Snow S, Madjar D, Reizner G, et al. Renal cell carcinoma metastatic to the scalp: case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 2001;27:192-194.

- Alcaraz I, Cerroni L, Rutten A, et al. Cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:347-393.

- Schwartz IS. Sister (Mary?) Joseph's nodule. N Engl J Med. 1987;316:1348-1349.

- Goldblum J, Hart W. Perianal Paget's disease: a histologic and immunohistochemical study of 11 cases with and without associated rectal adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:170-179.

- Ivan D, Nash J, Preito V, et al. Use of p63 expression in distinguishing primary and metastatic cutaneous adnexal neoplasms from metastatic adenocarcinoma to skin. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;34:474-480.

- Liang H, Wu H, Giorgadze T, et al. Podoplanin is a highly sensitive and specific marker to distinguish primary skin adnexal carcinomas from adenocarcinomas metastatic to skin. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:304-310.

A 67-year-old woman with no history of malignancy presented with a scalp nodule. The photomicrograph showed atypical glands forming a subepidermal nodule with pleomorphic cells characterized by scant eosinophilic cytoplasm and large prominent nucleoli. Immunohistochemical analysis revealed diffuse thyroid transcription factor 1 and cytokeratin 7 positivity.

Rapidly Recurring Keratoacanthoma

To the Editor:

A 61-year-old man with a medical history of type 2 diabetes mellitus presented to us with a 2.5×3.0-cm erythematous, ulcerated, and exophytic tumor on the right dorsal forearm that had rapidly developed over 2 weeks. A tangential biopsy was performed followed by treatment with electrodesiccation and curettage (ED&C). Histology revealed a squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), keratoacanthoma (KA) type. Over the next 11 days the lesion rapidly recurred and the patient returned with his own daily photodocumentation of the KA’s progression (Figure). The lesion was re-excised with 5-mm margins; histology again revealed SCC, KA type, with deep margin involvement. Chest radiograph revealed findings suspicious for metastatic lesions in the right lung. He was referred to oncology for metastatic workup; positron emission tomography was negative and ultimately the lung lesion was found to be benign. The patient underwent adjuvant radia-tion to the KA resection bed and lymph nodes with minimal side effects. The patient has remained cancer free to date.

Keratoacanthomas are rapidly growing, typically painless, cutaneous neoplasms that often develop on sun-exposed areas. They can occur spontaneously or following trauma and have the propensity to regress with time.1-3 They are described as progressing through 3 clinical stages: rapid proliferation, mature/stable, and involution. However, KAs can be aggressive, becoming locally destructive; therefore, KAs are typically treated to avoid further morbidity. Keratoacanthomas may be considered a subtype of SCC, as some have the potential to become locally destructive and metastasize.3-5 There are reports of spontaneous resolution of KAs over weeks to months, though surgical excision is the gold standard of treatment.3,5

Reactive KA is a subtype that is thought to develop at the site of prior trauma, representing a sort of Köbner phenomenon.3,4 We demonstrated a case of a recurrent KA in the setting of recent ED&C. Several reports describe KAs developing after dermatologic surgery, including Mohs micrographic surgery, laser resurfacing, radiation therapy, and after skin grafting.3,4,6 Trauma-induced epidermal injury and dermal inflammation may play a role in postoperative KA formation or recurrence.6

Keratoacanthoma recurrence has been reported in 3% to 8% of cases within a few weeks after treatment, as seen in our current patient.3,5 In our case, the patient photodocumented the regrowth of his lesion (Figure). Treatment of reactive KAs may be therapeutically challenging, as they can form or worsen with repeated surgeries and may require several treatment modalities to eradicate them.4 Treatment options include observation, ED&C, excision, Mohs micrographic surgery, radiation, cryosurgery, laser, isotretinoin, acitretin, imiquimod, 5-fluorouracil, methotrexate, interferon alfa-2b, or bleomycin, to name a few.3,4,7

Combination therapy should be considered in the presence of recurrent and/or aggressive KAs, such as in our case. Our patient has remained disease free after a combination of surgical excision with radiation therapy.

1. Schwartz R. Keratoacanthoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30:1-19.

2. Kingman J. Keratoacanthoma. Arch Dermatol. 1984;20:736-740.

3. Goldberg L, Silapunt S, Beyrau K, et al. Keratoacanthoma as a postoperative complication of skin cancer excision. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:753-758.

4. Hadley J, Tristani-Firouzi P, Florell S, et al. Case series of multiple recurrent reactive keratoacanthomas developing at surgical margins. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:2019-2024.

5. Karaa A, Khachemoune A. Keratoacanthoma: a tumor in search of a classification. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:671-678.

6. Chesnut GT, Maggio KL, Turiansky GW. Letter: re: case series of multiple recurrent reactive keratoacanthomas developing at surgical margins. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37:884-885.

7. Lernia V, Ricci C, Albertini G. Spontaneous regression of keratoacanthoma can be promoted by topical treatment with imiquimod cream. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004;18:626-629.

To the Editor:

A 61-year-old man with a medical history of type 2 diabetes mellitus presented to us with a 2.5×3.0-cm erythematous, ulcerated, and exophytic tumor on the right dorsal forearm that had rapidly developed over 2 weeks. A tangential biopsy was performed followed by treatment with electrodesiccation and curettage (ED&C). Histology revealed a squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), keratoacanthoma (KA) type. Over the next 11 days the lesion rapidly recurred and the patient returned with his own daily photodocumentation of the KA’s progression (Figure). The lesion was re-excised with 5-mm margins; histology again revealed SCC, KA type, with deep margin involvement. Chest radiograph revealed findings suspicious for metastatic lesions in the right lung. He was referred to oncology for metastatic workup; positron emission tomography was negative and ultimately the lung lesion was found to be benign. The patient underwent adjuvant radia-tion to the KA resection bed and lymph nodes with minimal side effects. The patient has remained cancer free to date.

Keratoacanthomas are rapidly growing, typically painless, cutaneous neoplasms that often develop on sun-exposed areas. They can occur spontaneously or following trauma and have the propensity to regress with time.1-3 They are described as progressing through 3 clinical stages: rapid proliferation, mature/stable, and involution. However, KAs can be aggressive, becoming locally destructive; therefore, KAs are typically treated to avoid further morbidity. Keratoacanthomas may be considered a subtype of SCC, as some have the potential to become locally destructive and metastasize.3-5 There are reports of spontaneous resolution of KAs over weeks to months, though surgical excision is the gold standard of treatment.3,5

Reactive KA is a subtype that is thought to develop at the site of prior trauma, representing a sort of Köbner phenomenon.3,4 We demonstrated a case of a recurrent KA in the setting of recent ED&C. Several reports describe KAs developing after dermatologic surgery, including Mohs micrographic surgery, laser resurfacing, radiation therapy, and after skin grafting.3,4,6 Trauma-induced epidermal injury and dermal inflammation may play a role in postoperative KA formation or recurrence.6

Keratoacanthoma recurrence has been reported in 3% to 8% of cases within a few weeks after treatment, as seen in our current patient.3,5 In our case, the patient photodocumented the regrowth of his lesion (Figure). Treatment of reactive KAs may be therapeutically challenging, as they can form or worsen with repeated surgeries and may require several treatment modalities to eradicate them.4 Treatment options include observation, ED&C, excision, Mohs micrographic surgery, radiation, cryosurgery, laser, isotretinoin, acitretin, imiquimod, 5-fluorouracil, methotrexate, interferon alfa-2b, or bleomycin, to name a few.3,4,7

Combination therapy should be considered in the presence of recurrent and/or aggressive KAs, such as in our case. Our patient has remained disease free after a combination of surgical excision with radiation therapy.

To the Editor:

A 61-year-old man with a medical history of type 2 diabetes mellitus presented to us with a 2.5×3.0-cm erythematous, ulcerated, and exophytic tumor on the right dorsal forearm that had rapidly developed over 2 weeks. A tangential biopsy was performed followed by treatment with electrodesiccation and curettage (ED&C). Histology revealed a squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), keratoacanthoma (KA) type. Over the next 11 days the lesion rapidly recurred and the patient returned with his own daily photodocumentation of the KA’s progression (Figure). The lesion was re-excised with 5-mm margins; histology again revealed SCC, KA type, with deep margin involvement. Chest radiograph revealed findings suspicious for metastatic lesions in the right lung. He was referred to oncology for metastatic workup; positron emission tomography was negative and ultimately the lung lesion was found to be benign. The patient underwent adjuvant radia-tion to the KA resection bed and lymph nodes with minimal side effects. The patient has remained cancer free to date.

Keratoacanthomas are rapidly growing, typically painless, cutaneous neoplasms that often develop on sun-exposed areas. They can occur spontaneously or following trauma and have the propensity to regress with time.1-3 They are described as progressing through 3 clinical stages: rapid proliferation, mature/stable, and involution. However, KAs can be aggressive, becoming locally destructive; therefore, KAs are typically treated to avoid further morbidity. Keratoacanthomas may be considered a subtype of SCC, as some have the potential to become locally destructive and metastasize.3-5 There are reports of spontaneous resolution of KAs over weeks to months, though surgical excision is the gold standard of treatment.3,5

Reactive KA is a subtype that is thought to develop at the site of prior trauma, representing a sort of Köbner phenomenon.3,4 We demonstrated a case of a recurrent KA in the setting of recent ED&C. Several reports describe KAs developing after dermatologic surgery, including Mohs micrographic surgery, laser resurfacing, radiation therapy, and after skin grafting.3,4,6 Trauma-induced epidermal injury and dermal inflammation may play a role in postoperative KA formation or recurrence.6

Keratoacanthoma recurrence has been reported in 3% to 8% of cases within a few weeks after treatment, as seen in our current patient.3,5 In our case, the patient photodocumented the regrowth of his lesion (Figure). Treatment of reactive KAs may be therapeutically challenging, as they can form or worsen with repeated surgeries and may require several treatment modalities to eradicate them.4 Treatment options include observation, ED&C, excision, Mohs micrographic surgery, radiation, cryosurgery, laser, isotretinoin, acitretin, imiquimod, 5-fluorouracil, methotrexate, interferon alfa-2b, or bleomycin, to name a few.3,4,7

Combination therapy should be considered in the presence of recurrent and/or aggressive KAs, such as in our case. Our patient has remained disease free after a combination of surgical excision with radiation therapy.

1. Schwartz R. Keratoacanthoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30:1-19.

2. Kingman J. Keratoacanthoma. Arch Dermatol. 1984;20:736-740.

3. Goldberg L, Silapunt S, Beyrau K, et al. Keratoacanthoma as a postoperative complication of skin cancer excision. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:753-758.

4. Hadley J, Tristani-Firouzi P, Florell S, et al. Case series of multiple recurrent reactive keratoacanthomas developing at surgical margins. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:2019-2024.

5. Karaa A, Khachemoune A. Keratoacanthoma: a tumor in search of a classification. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:671-678.

6. Chesnut GT, Maggio KL, Turiansky GW. Letter: re: case series of multiple recurrent reactive keratoacanthomas developing at surgical margins. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37:884-885.

7. Lernia V, Ricci C, Albertini G. Spontaneous regression of keratoacanthoma can be promoted by topical treatment with imiquimod cream. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004;18:626-629.

1. Schwartz R. Keratoacanthoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30:1-19.

2. Kingman J. Keratoacanthoma. Arch Dermatol. 1984;20:736-740.

3. Goldberg L, Silapunt S, Beyrau K, et al. Keratoacanthoma as a postoperative complication of skin cancer excision. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:753-758.

4. Hadley J, Tristani-Firouzi P, Florell S, et al. Case series of multiple recurrent reactive keratoacanthomas developing at surgical margins. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:2019-2024.

5. Karaa A, Khachemoune A. Keratoacanthoma: a tumor in search of a classification. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:671-678.

6. Chesnut GT, Maggio KL, Turiansky GW. Letter: re: case series of multiple recurrent reactive keratoacanthomas developing at surgical margins. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37:884-885.

7. Lernia V, Ricci C, Albertini G. Spontaneous regression of keratoacanthoma can be promoted by topical treatment with imiquimod cream. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004;18:626-629.