User login

Eosinophilic Pustular Folliculitis With Underlying Mantle Cell Lymphoma

Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis (EPF) was originally described in 1965 and has since evolved into 3 distinct subtypes: classic, immunosuppressed (IS), and infantile types. Immunosuppressed EPF can be further subdivided into human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) associated (IS-HIV) and non-HIV associated. Human immunodeficiency virus–seronegative cases have been associated with underlying malignancies (IS-heme) or chronic immunosuppression, such as that seen in transplant patients.

Case Report

A 52-year-old man with a medical history limited to prostate adenocarcinoma treated with a robotic prostatectomy presented with a pruritic red rash on the face, neck, shoulders, and chest of 1 month’s duration. The patient previously completed a course of azithromycin 250 mg, intramuscular triamcinolone, and oral prednisone with only minor improvement. Physical examination demonstrated multiple pink folliculocentric papules and pustules scattered on the head (Figure 1A), neck, and chest (Figure 1B), as well as edematous pink papules and plaques on the forehead (Figures 1C and 1D). The palms, soles, and oral mucosa were clear.

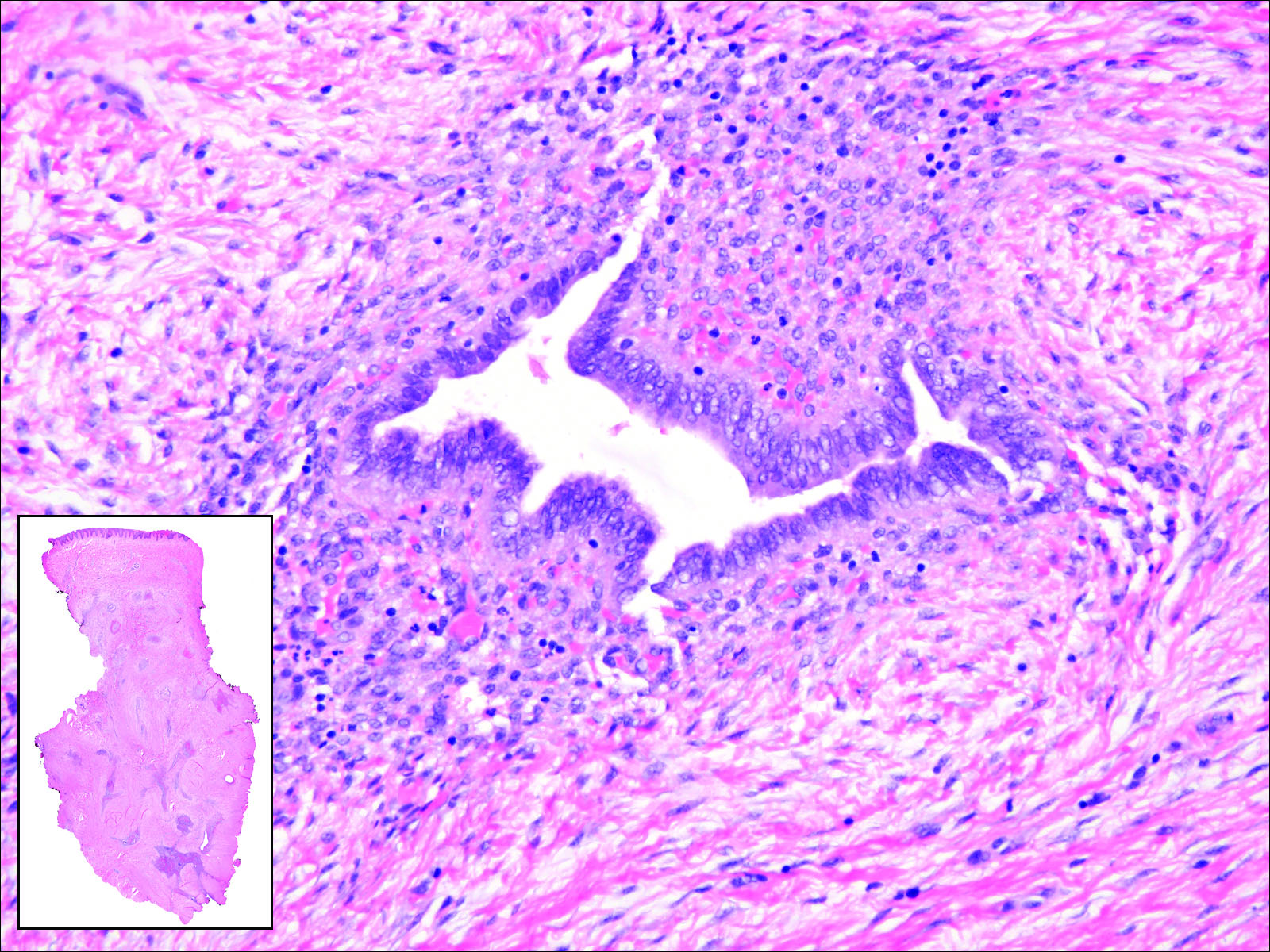

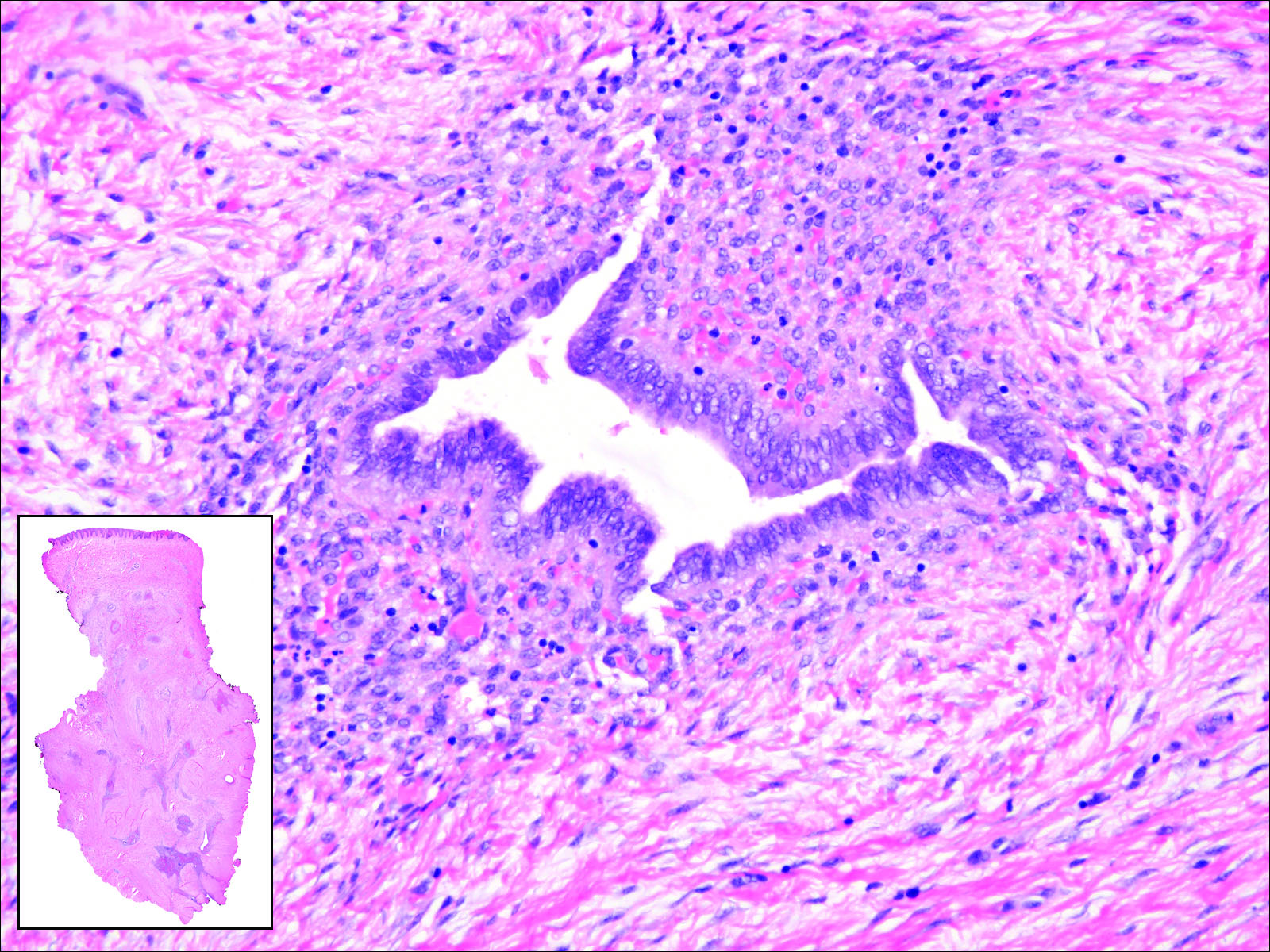

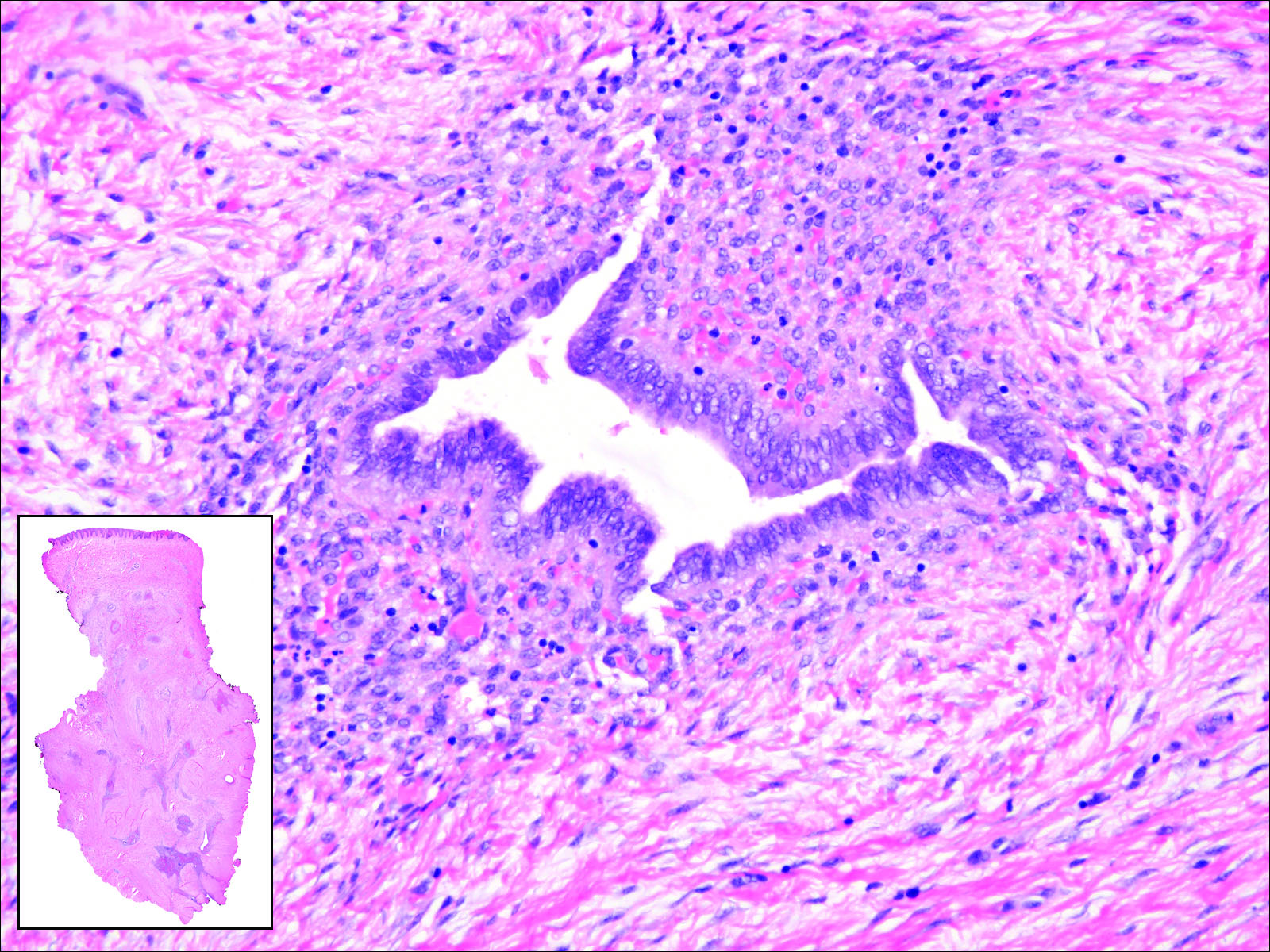

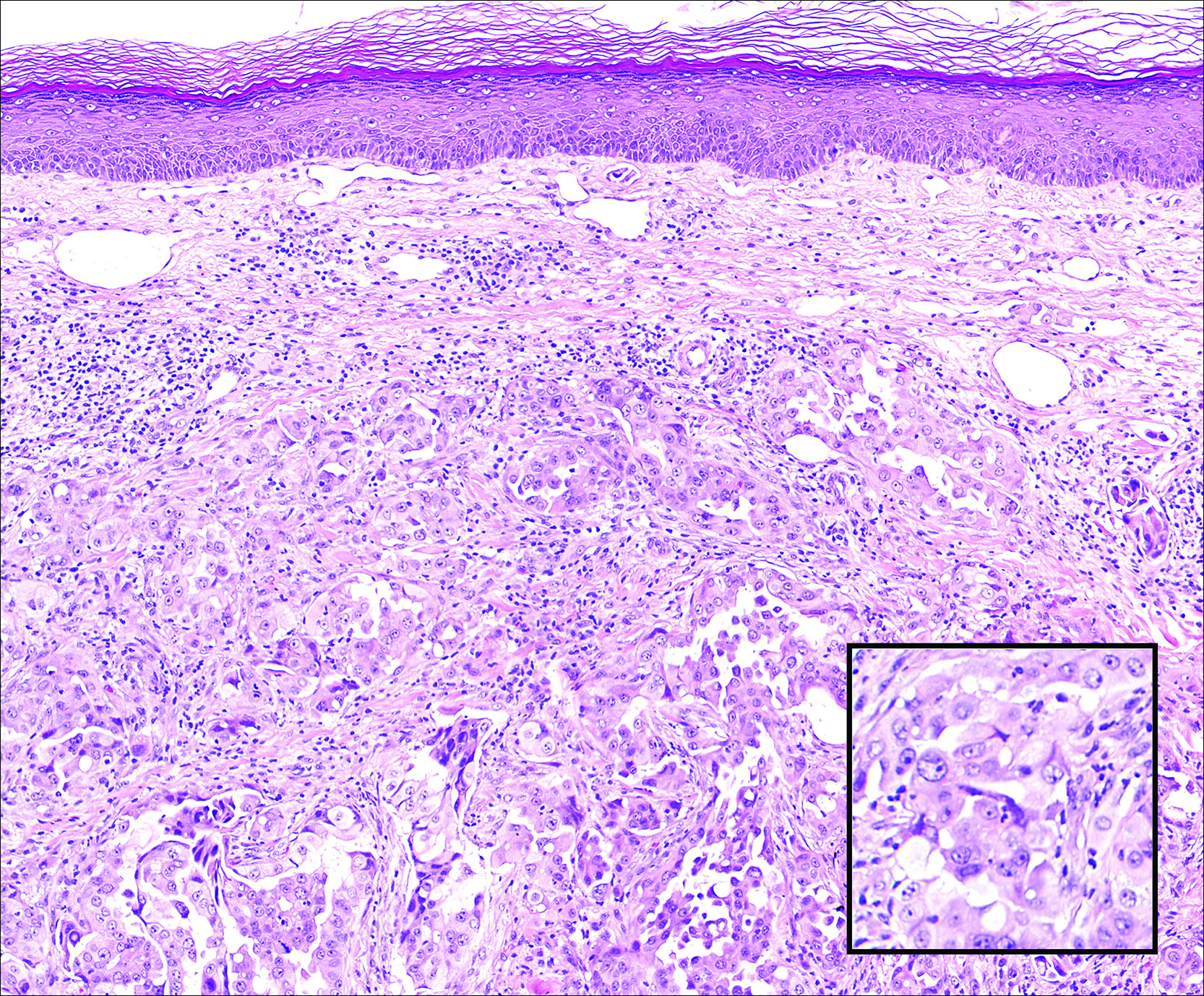

Initial biopsy of the right side of the chest was nonspecific and most consistent with a reaction to an arthropod bite. The patient was started on oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 2 weeks. With no improvement seen, additional biopsies were obtained from the left side of the chest and forehead. The biopsy of the chest showed ruptured folliculitis with evidence of acute and chronic inflammation. The biopsy of the forehead demonstrated eosinophilic follicular spongiosis with intrafollicular Langerhans cell microgranulomas along with abundant eosinophils adjacent to follicles, consistent with EPF (Figure 2). Serum HIV testing was negative. Serum white blood cell count was normal at 6400/µL (reference range, 4500–11,000/µL) with mild elevation of eosinophils (8%). The remaining complete blood cell count and comprehensive metabolic panel were within reference range. The patient was subsequently started on oral indomethacin 25 mg twice daily and triamcinolone cream 0.1%. Within a few days he experienced initial improvement in his symptoms of pruritus and diminution in the number of inflammatory follicular papules.

Approximately 1 month after presentation, he began to experience symptoms of dysphagia and fatigue. In addition, tonsillar hypertrophy and palpable neck and axillary lymphadenopathy were present. Computed tomography of the neck, chest, and abdomen showed diffuse lymphadenopathy. Full-body positron emission tomography–computed tomography demonstrated extensive metabolically active lymphoma in multiple nodal groups above and below the diaphragm. There also was lymphomatous involvement of the spleen. An axillary lymph node biopsy was diagnostic for mantle cell lymphoma (CD4:CD8, 1:1; CD45 negative; CD20 positive; CD5 positive). He

Comment

Subtypes of EPF

Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis was first described in a Japanese female presenting with folliculocentric pustules distributed on the face, torso, and arms.1 This noninfectious eosinophilic infiltration of hair follicles predominantly seen in the Japanese population is now regarded as the classic form. Three distinct subtypes of EPF now exist, including the originally described classic variant (Ofuji disease), an IS variant, and a rare infantile form.1

All 3 subtypes of EPF are more commonly seen in men than women. The classic form has a peak incidence between the third and fourth decades of life. It presents as chronic annular papules and sterile pustules exhibiting peripheral extension, with individual lesions lasting for approximately 7 to 10 days with frequent relapses. The face is the most common area of involvement, followed by the trunk, extremities, and more rarely the palmoplantar surfaces. Concomitant leukocytosis with eosinophilia is seen in up to 35% of patients.1 The infantile type represents the rarest EPF form. The average age of onset is 5 months, with most cases resolving by 14 months of age.1

Clinically, EPF is characterized by recurrent papules and pustules predominantly on the scalp without annular or polycyclic ring formation, as seen in the classic type. The palms and soles may be involved, which can clinically mimic infantile acropustulosis and scabies infection. Most patients exhibit a concomitant peripheral eosinophilia.1,2

In the late 1980s, the IS variant of EPF was recognized in HIV-positive (IS-HIV) and HIV-negative malignancy-associated (IS-heme) populations.1,3 This newly characterized form differs morphologically and biologically from the classic and infantile subtypes. The IS subtype has a unique presentation including intensely pruritic, discrete, erythematous, follicular papules with palmoplantar sparing and infrequent annular or circinate plaque forms.1 Frequently, with the IS-HIV form, CD4+ T-cell counts are below 300 cells/mL, and 25% to 50% of patients have lymphopenia with eosinophilia.3 Highly active antiretroviral therapy has been associated with EPF resolution in HIV-positive individuals; however, it also has been shown to induce transient EPF during the first 3 to 6 months of initiation.1,3,4

Unlike the IS-HIV form, the IS-heme form has occurred solely in males and is predominantly associated with hematologic malignancies (eg, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, acute myeloid leukemia, myelodysplastic syndrome) 30 to 90 days following bone marrow transplant, peripheral blood stem cell transplant, or chemotherapy treatment.5,6 Unlike the chronic and persistent IS-HIV form, prior cases of IS-heme EPF have been predominantly self-limited. Interestingly, only 2 reported cases of EPF have occurred prior to the diagnosis of malignancy including B-cell leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome.5

Histopathology

All 3 identified forms of EPF histopathologically show acute and chronic lymphoeosinophilic infiltrate concentrated at the follicular isthmus, which can lead to follicular destruction. Scattered mononuclear cells, eosinophils, and neutrophils are found within the pilar outer root sheath, sebaceous glands, and ducts. Approximately 40% of cases demonstrate follicular mucinosis.1 Histopathology of lesional palmar skin in classic-type EPF demonstrates intraepidermal pustule formation with abundant eosinophils and neutrophils adjacent to the acrosyringium.7,8

Pathogenesis

Although the pathophysiology of EPF is largely unknown, it is thought to represent a helper T cell (TH2) response involving IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 cytokines.9 Chemoattractant receptor homologous molecule 2, which is expressed on eosinophils and lymphocytes, is believed to play a role in the pruritus, edema, and inflammatory response seen adjacent to pilosebaceous units in EPF.10 Moreover, immunohistochemical and flow cytometry analysis has revealed a prevalence of prostaglandin D2 within the perisebocyte infiltrate in EPF.9 Prostaglandin D2 induces eotaxin-3 production within sebocytes via peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ, which enhances chemoattraction of eosinophils. This pathogenesis represents a prostaglandin-based mechanism and potentially explains the efficacy of indomethacin treatment of EPF through its cyclooxygenase inhibition and reduction of chemoattractant receptor homologous molecule 2 expression.9-11

Treatment

Multiple therapeutic modalities have been reported for the treatment of EPF. For all 3 subtypes, moderate- to high-potency topical corticosteroids are considered first-line therapy. UVB phototherapy 2 to 3 times weekly remains the gold standard, given its consistent efficacy.1,12 Indomethacin (50–75 mg daily) remains first-line treatment of classic EPF.4,12 Previously reported cases of classic EPF and IS-EPF have responded well to oral prednisone (1 mg/kg daily).12,13 In a retrospective review of EPF treatment data, the following treatments also have been reported to be successful: psoralen plus UVA, oral cetirizine (20–40 mg daily, particularly for IS-EPF cases), metronidazole (250 mg 3 times daily), minocycline (150 mg daily), itraconazole (200–400 mg daily, dapsone (50–200 mg daily), systemic retinoids, tacrolimus ointment 0.1%, and permethrin cream.4,12

Malignancy

Although the entity of IS-heme EPF is rare, the morphology and treatment are unique and can potentially unmask an underlying hematologic malignancy. In patients with EPF and associated malignancy, such as our patient, a differential diagnosis to consider is eosinophilic dermatosis of hematologic malignancy (EDHM). Eosinophilic dermatosis of hematologic malignancy is most commonly associated with chronic lymphocytic leukemia and can be differentiated from EPF clinically, histopathologically, and by treatment response. Eosinophilic dermatosis of hematologic malignancy clinically presents with nonspecific papules, pustules, and/or vesicles on the head, trunk, and extremities. On histopathology, EDHM shows a superficial and deep perivascular and interstitial lymphoeosinophilic infiltration. Furthermore, EDHM patients typically exhibit a poor treatment response to oral indomethacin.14

Conclusion

Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis is a noninfectious folliculocentric process comprised of 3 distinct types. The histopathology shows follicular spongiosis with increased eosinophils. The pathogenesis is most likely related to a multifactorial immune system dysregulation involving TH2 T cells, prostaglandin D2, and eotaxin-3. The treatment of EPF may involve topical corticosteroids, UVB phototherapy, or most notably oral indomethacin. In patients with EPF and malignancy, EDHM is a differential diagnosis to consider. Our case serves as a reminder that rare eosinophilic dermatoses may represent manifestations of underlying hematopoietic malignancy and, when investigated early, can lead to appropriate life-saving treatment.

- Nervi J, Stephen. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis: a 40 year retrospect. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:285-289.

- Hernández-Martín Á, Nuño-González A, Colmenero I, et al. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis of infancy: a series of 15 cases and review of the literature [published online July 21, 2012]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:150-155.

- Soepr

ono F, Schinella R. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. report of three cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;14:1020-1022. - Katoh

M, Nomura T, Miyachi Y, et al. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis: a review of the Japanese published works. J Dermatol. 2013;40:15-20. - Keida

T, Hayashi N, Kawashima M. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis following autologous peripheral blood stem-cell transplant. J Dermatol. 2004;31:21-26. - Goiriz R, Gul-Millán G, Peñas PF, et al. Eosinophilic folliculitis following allogeneic peripheral blood stem cell transplantation: case report and review. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34(suppl 1):33-36.

- Satoh T, Ikeda H, Yokozeki H. Acrosyringeal involvement of palmoplantar lesions of eosinophilic pustular folliculitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2013;93:99.

- Tsuboi H, Wakita K, Fujimura T, et al. Acral variant of eosinophilic pustular folliculitis (Ofuji’s disease). Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28:321-324.

- Nakahig

ashi K, Doi H, Otsuka A, et al. PGD2 induces eotaxin-3 via PPARgamma from sebocytes: a possible pathogenesis of eosinophilic pustular folliculitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:536-543. - Satoh

T, Shimura C, Miyagishi C, et al. Indomethacin-induced reduction in CRTH2 in eosinophilic pustular folliculitis (Ofuji’s disease): a proposed mechanism of action. Acta Derm Venereol. 2010;90:18-22. - Hagiwara A, Fujimura T, Furudate S, et al. Induction of CD163(+)M2 macrophages in the lesional skin of eosinophilic pustular folliculitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2014;94:104-106.

- Ellis

E, Scheinfeld N. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis: a comprehensive review of treatment options. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2004;5:189-197. - Bull R

H, Harland CA, Fallowfield ME, et al. Eosinophilic folliculitis: a self-limiting illness in patients being treated for haematological malignancy. Br J Dermatol. 1993;129:178-182. - Farber M, Forgia S, Sahu J, et al. Eosinophilic dermatosis of hematologic malignancy. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:690-695.

Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis (EPF) was originally described in 1965 and has since evolved into 3 distinct subtypes: classic, immunosuppressed (IS), and infantile types. Immunosuppressed EPF can be further subdivided into human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) associated (IS-HIV) and non-HIV associated. Human immunodeficiency virus–seronegative cases have been associated with underlying malignancies (IS-heme) or chronic immunosuppression, such as that seen in transplant patients.

Case Report

A 52-year-old man with a medical history limited to prostate adenocarcinoma treated with a robotic prostatectomy presented with a pruritic red rash on the face, neck, shoulders, and chest of 1 month’s duration. The patient previously completed a course of azithromycin 250 mg, intramuscular triamcinolone, and oral prednisone with only minor improvement. Physical examination demonstrated multiple pink folliculocentric papules and pustules scattered on the head (Figure 1A), neck, and chest (Figure 1B), as well as edematous pink papules and plaques on the forehead (Figures 1C and 1D). The palms, soles, and oral mucosa were clear.

Initial biopsy of the right side of the chest was nonspecific and most consistent with a reaction to an arthropod bite. The patient was started on oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 2 weeks. With no improvement seen, additional biopsies were obtained from the left side of the chest and forehead. The biopsy of the chest showed ruptured folliculitis with evidence of acute and chronic inflammation. The biopsy of the forehead demonstrated eosinophilic follicular spongiosis with intrafollicular Langerhans cell microgranulomas along with abundant eosinophils adjacent to follicles, consistent with EPF (Figure 2). Serum HIV testing was negative. Serum white blood cell count was normal at 6400/µL (reference range, 4500–11,000/µL) with mild elevation of eosinophils (8%). The remaining complete blood cell count and comprehensive metabolic panel were within reference range. The patient was subsequently started on oral indomethacin 25 mg twice daily and triamcinolone cream 0.1%. Within a few days he experienced initial improvement in his symptoms of pruritus and diminution in the number of inflammatory follicular papules.

Approximately 1 month after presentation, he began to experience symptoms of dysphagia and fatigue. In addition, tonsillar hypertrophy and palpable neck and axillary lymphadenopathy were present. Computed tomography of the neck, chest, and abdomen showed diffuse lymphadenopathy. Full-body positron emission tomography–computed tomography demonstrated extensive metabolically active lymphoma in multiple nodal groups above and below the diaphragm. There also was lymphomatous involvement of the spleen. An axillary lymph node biopsy was diagnostic for mantle cell lymphoma (CD4:CD8, 1:1; CD45 negative; CD20 positive; CD5 positive). He

Comment

Subtypes of EPF

Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis was first described in a Japanese female presenting with folliculocentric pustules distributed on the face, torso, and arms.1 This noninfectious eosinophilic infiltration of hair follicles predominantly seen in the Japanese population is now regarded as the classic form. Three distinct subtypes of EPF now exist, including the originally described classic variant (Ofuji disease), an IS variant, and a rare infantile form.1

All 3 subtypes of EPF are more commonly seen in men than women. The classic form has a peak incidence between the third and fourth decades of life. It presents as chronic annular papules and sterile pustules exhibiting peripheral extension, with individual lesions lasting for approximately 7 to 10 days with frequent relapses. The face is the most common area of involvement, followed by the trunk, extremities, and more rarely the palmoplantar surfaces. Concomitant leukocytosis with eosinophilia is seen in up to 35% of patients.1 The infantile type represents the rarest EPF form. The average age of onset is 5 months, with most cases resolving by 14 months of age.1

Clinically, EPF is characterized by recurrent papules and pustules predominantly on the scalp without annular or polycyclic ring formation, as seen in the classic type. The palms and soles may be involved, which can clinically mimic infantile acropustulosis and scabies infection. Most patients exhibit a concomitant peripheral eosinophilia.1,2

In the late 1980s, the IS variant of EPF was recognized in HIV-positive (IS-HIV) and HIV-negative malignancy-associated (IS-heme) populations.1,3 This newly characterized form differs morphologically and biologically from the classic and infantile subtypes. The IS subtype has a unique presentation including intensely pruritic, discrete, erythematous, follicular papules with palmoplantar sparing and infrequent annular or circinate plaque forms.1 Frequently, with the IS-HIV form, CD4+ T-cell counts are below 300 cells/mL, and 25% to 50% of patients have lymphopenia with eosinophilia.3 Highly active antiretroviral therapy has been associated with EPF resolution in HIV-positive individuals; however, it also has been shown to induce transient EPF during the first 3 to 6 months of initiation.1,3,4

Unlike the IS-HIV form, the IS-heme form has occurred solely in males and is predominantly associated with hematologic malignancies (eg, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, acute myeloid leukemia, myelodysplastic syndrome) 30 to 90 days following bone marrow transplant, peripheral blood stem cell transplant, or chemotherapy treatment.5,6 Unlike the chronic and persistent IS-HIV form, prior cases of IS-heme EPF have been predominantly self-limited. Interestingly, only 2 reported cases of EPF have occurred prior to the diagnosis of malignancy including B-cell leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome.5

Histopathology

All 3 identified forms of EPF histopathologically show acute and chronic lymphoeosinophilic infiltrate concentrated at the follicular isthmus, which can lead to follicular destruction. Scattered mononuclear cells, eosinophils, and neutrophils are found within the pilar outer root sheath, sebaceous glands, and ducts. Approximately 40% of cases demonstrate follicular mucinosis.1 Histopathology of lesional palmar skin in classic-type EPF demonstrates intraepidermal pustule formation with abundant eosinophils and neutrophils adjacent to the acrosyringium.7,8

Pathogenesis

Although the pathophysiology of EPF is largely unknown, it is thought to represent a helper T cell (TH2) response involving IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 cytokines.9 Chemoattractant receptor homologous molecule 2, which is expressed on eosinophils and lymphocytes, is believed to play a role in the pruritus, edema, and inflammatory response seen adjacent to pilosebaceous units in EPF.10 Moreover, immunohistochemical and flow cytometry analysis has revealed a prevalence of prostaglandin D2 within the perisebocyte infiltrate in EPF.9 Prostaglandin D2 induces eotaxin-3 production within sebocytes via peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ, which enhances chemoattraction of eosinophils. This pathogenesis represents a prostaglandin-based mechanism and potentially explains the efficacy of indomethacin treatment of EPF through its cyclooxygenase inhibition and reduction of chemoattractant receptor homologous molecule 2 expression.9-11

Treatment

Multiple therapeutic modalities have been reported for the treatment of EPF. For all 3 subtypes, moderate- to high-potency topical corticosteroids are considered first-line therapy. UVB phototherapy 2 to 3 times weekly remains the gold standard, given its consistent efficacy.1,12 Indomethacin (50–75 mg daily) remains first-line treatment of classic EPF.4,12 Previously reported cases of classic EPF and IS-EPF have responded well to oral prednisone (1 mg/kg daily).12,13 In a retrospective review of EPF treatment data, the following treatments also have been reported to be successful: psoralen plus UVA, oral cetirizine (20–40 mg daily, particularly for IS-EPF cases), metronidazole (250 mg 3 times daily), minocycline (150 mg daily), itraconazole (200–400 mg daily, dapsone (50–200 mg daily), systemic retinoids, tacrolimus ointment 0.1%, and permethrin cream.4,12

Malignancy

Although the entity of IS-heme EPF is rare, the morphology and treatment are unique and can potentially unmask an underlying hematologic malignancy. In patients with EPF and associated malignancy, such as our patient, a differential diagnosis to consider is eosinophilic dermatosis of hematologic malignancy (EDHM). Eosinophilic dermatosis of hematologic malignancy is most commonly associated with chronic lymphocytic leukemia and can be differentiated from EPF clinically, histopathologically, and by treatment response. Eosinophilic dermatosis of hematologic malignancy clinically presents with nonspecific papules, pustules, and/or vesicles on the head, trunk, and extremities. On histopathology, EDHM shows a superficial and deep perivascular and interstitial lymphoeosinophilic infiltration. Furthermore, EDHM patients typically exhibit a poor treatment response to oral indomethacin.14

Conclusion

Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis is a noninfectious folliculocentric process comprised of 3 distinct types. The histopathology shows follicular spongiosis with increased eosinophils. The pathogenesis is most likely related to a multifactorial immune system dysregulation involving TH2 T cells, prostaglandin D2, and eotaxin-3. The treatment of EPF may involve topical corticosteroids, UVB phototherapy, or most notably oral indomethacin. In patients with EPF and malignancy, EDHM is a differential diagnosis to consider. Our case serves as a reminder that rare eosinophilic dermatoses may represent manifestations of underlying hematopoietic malignancy and, when investigated early, can lead to appropriate life-saving treatment.

Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis (EPF) was originally described in 1965 and has since evolved into 3 distinct subtypes: classic, immunosuppressed (IS), and infantile types. Immunosuppressed EPF can be further subdivided into human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) associated (IS-HIV) and non-HIV associated. Human immunodeficiency virus–seronegative cases have been associated with underlying malignancies (IS-heme) or chronic immunosuppression, such as that seen in transplant patients.

Case Report

A 52-year-old man with a medical history limited to prostate adenocarcinoma treated with a robotic prostatectomy presented with a pruritic red rash on the face, neck, shoulders, and chest of 1 month’s duration. The patient previously completed a course of azithromycin 250 mg, intramuscular triamcinolone, and oral prednisone with only minor improvement. Physical examination demonstrated multiple pink folliculocentric papules and pustules scattered on the head (Figure 1A), neck, and chest (Figure 1B), as well as edematous pink papules and plaques on the forehead (Figures 1C and 1D). The palms, soles, and oral mucosa were clear.

Initial biopsy of the right side of the chest was nonspecific and most consistent with a reaction to an arthropod bite. The patient was started on oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 2 weeks. With no improvement seen, additional biopsies were obtained from the left side of the chest and forehead. The biopsy of the chest showed ruptured folliculitis with evidence of acute and chronic inflammation. The biopsy of the forehead demonstrated eosinophilic follicular spongiosis with intrafollicular Langerhans cell microgranulomas along with abundant eosinophils adjacent to follicles, consistent with EPF (Figure 2). Serum HIV testing was negative. Serum white blood cell count was normal at 6400/µL (reference range, 4500–11,000/µL) with mild elevation of eosinophils (8%). The remaining complete blood cell count and comprehensive metabolic panel were within reference range. The patient was subsequently started on oral indomethacin 25 mg twice daily and triamcinolone cream 0.1%. Within a few days he experienced initial improvement in his symptoms of pruritus and diminution in the number of inflammatory follicular papules.

Approximately 1 month after presentation, he began to experience symptoms of dysphagia and fatigue. In addition, tonsillar hypertrophy and palpable neck and axillary lymphadenopathy were present. Computed tomography of the neck, chest, and abdomen showed diffuse lymphadenopathy. Full-body positron emission tomography–computed tomography demonstrated extensive metabolically active lymphoma in multiple nodal groups above and below the diaphragm. There also was lymphomatous involvement of the spleen. An axillary lymph node biopsy was diagnostic for mantle cell lymphoma (CD4:CD8, 1:1; CD45 negative; CD20 positive; CD5 positive). He

Comment

Subtypes of EPF

Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis was first described in a Japanese female presenting with folliculocentric pustules distributed on the face, torso, and arms.1 This noninfectious eosinophilic infiltration of hair follicles predominantly seen in the Japanese population is now regarded as the classic form. Three distinct subtypes of EPF now exist, including the originally described classic variant (Ofuji disease), an IS variant, and a rare infantile form.1

All 3 subtypes of EPF are more commonly seen in men than women. The classic form has a peak incidence between the third and fourth decades of life. It presents as chronic annular papules and sterile pustules exhibiting peripheral extension, with individual lesions lasting for approximately 7 to 10 days with frequent relapses. The face is the most common area of involvement, followed by the trunk, extremities, and more rarely the palmoplantar surfaces. Concomitant leukocytosis with eosinophilia is seen in up to 35% of patients.1 The infantile type represents the rarest EPF form. The average age of onset is 5 months, with most cases resolving by 14 months of age.1

Clinically, EPF is characterized by recurrent papules and pustules predominantly on the scalp without annular or polycyclic ring formation, as seen in the classic type. The palms and soles may be involved, which can clinically mimic infantile acropustulosis and scabies infection. Most patients exhibit a concomitant peripheral eosinophilia.1,2

In the late 1980s, the IS variant of EPF was recognized in HIV-positive (IS-HIV) and HIV-negative malignancy-associated (IS-heme) populations.1,3 This newly characterized form differs morphologically and biologically from the classic and infantile subtypes. The IS subtype has a unique presentation including intensely pruritic, discrete, erythematous, follicular papules with palmoplantar sparing and infrequent annular or circinate plaque forms.1 Frequently, with the IS-HIV form, CD4+ T-cell counts are below 300 cells/mL, and 25% to 50% of patients have lymphopenia with eosinophilia.3 Highly active antiretroviral therapy has been associated with EPF resolution in HIV-positive individuals; however, it also has been shown to induce transient EPF during the first 3 to 6 months of initiation.1,3,4

Unlike the IS-HIV form, the IS-heme form has occurred solely in males and is predominantly associated with hematologic malignancies (eg, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, acute myeloid leukemia, myelodysplastic syndrome) 30 to 90 days following bone marrow transplant, peripheral blood stem cell transplant, or chemotherapy treatment.5,6 Unlike the chronic and persistent IS-HIV form, prior cases of IS-heme EPF have been predominantly self-limited. Interestingly, only 2 reported cases of EPF have occurred prior to the diagnosis of malignancy including B-cell leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome.5

Histopathology

All 3 identified forms of EPF histopathologically show acute and chronic lymphoeosinophilic infiltrate concentrated at the follicular isthmus, which can lead to follicular destruction. Scattered mononuclear cells, eosinophils, and neutrophils are found within the pilar outer root sheath, sebaceous glands, and ducts. Approximately 40% of cases demonstrate follicular mucinosis.1 Histopathology of lesional palmar skin in classic-type EPF demonstrates intraepidermal pustule formation with abundant eosinophils and neutrophils adjacent to the acrosyringium.7,8

Pathogenesis

Although the pathophysiology of EPF is largely unknown, it is thought to represent a helper T cell (TH2) response involving IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 cytokines.9 Chemoattractant receptor homologous molecule 2, which is expressed on eosinophils and lymphocytes, is believed to play a role in the pruritus, edema, and inflammatory response seen adjacent to pilosebaceous units in EPF.10 Moreover, immunohistochemical and flow cytometry analysis has revealed a prevalence of prostaglandin D2 within the perisebocyte infiltrate in EPF.9 Prostaglandin D2 induces eotaxin-3 production within sebocytes via peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ, which enhances chemoattraction of eosinophils. This pathogenesis represents a prostaglandin-based mechanism and potentially explains the efficacy of indomethacin treatment of EPF through its cyclooxygenase inhibition and reduction of chemoattractant receptor homologous molecule 2 expression.9-11

Treatment

Multiple therapeutic modalities have been reported for the treatment of EPF. For all 3 subtypes, moderate- to high-potency topical corticosteroids are considered first-line therapy. UVB phototherapy 2 to 3 times weekly remains the gold standard, given its consistent efficacy.1,12 Indomethacin (50–75 mg daily) remains first-line treatment of classic EPF.4,12 Previously reported cases of classic EPF and IS-EPF have responded well to oral prednisone (1 mg/kg daily).12,13 In a retrospective review of EPF treatment data, the following treatments also have been reported to be successful: psoralen plus UVA, oral cetirizine (20–40 mg daily, particularly for IS-EPF cases), metronidazole (250 mg 3 times daily), minocycline (150 mg daily), itraconazole (200–400 mg daily, dapsone (50–200 mg daily), systemic retinoids, tacrolimus ointment 0.1%, and permethrin cream.4,12

Malignancy

Although the entity of IS-heme EPF is rare, the morphology and treatment are unique and can potentially unmask an underlying hematologic malignancy. In patients with EPF and associated malignancy, such as our patient, a differential diagnosis to consider is eosinophilic dermatosis of hematologic malignancy (EDHM). Eosinophilic dermatosis of hematologic malignancy is most commonly associated with chronic lymphocytic leukemia and can be differentiated from EPF clinically, histopathologically, and by treatment response. Eosinophilic dermatosis of hematologic malignancy clinically presents with nonspecific papules, pustules, and/or vesicles on the head, trunk, and extremities. On histopathology, EDHM shows a superficial and deep perivascular and interstitial lymphoeosinophilic infiltration. Furthermore, EDHM patients typically exhibit a poor treatment response to oral indomethacin.14

Conclusion

Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis is a noninfectious folliculocentric process comprised of 3 distinct types. The histopathology shows follicular spongiosis with increased eosinophils. The pathogenesis is most likely related to a multifactorial immune system dysregulation involving TH2 T cells, prostaglandin D2, and eotaxin-3. The treatment of EPF may involve topical corticosteroids, UVB phototherapy, or most notably oral indomethacin. In patients with EPF and malignancy, EDHM is a differential diagnosis to consider. Our case serves as a reminder that rare eosinophilic dermatoses may represent manifestations of underlying hematopoietic malignancy and, when investigated early, can lead to appropriate life-saving treatment.

- Nervi J, Stephen. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis: a 40 year retrospect. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:285-289.

- Hernández-Martín Á, Nuño-González A, Colmenero I, et al. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis of infancy: a series of 15 cases and review of the literature [published online July 21, 2012]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:150-155.

- Soepr

ono F, Schinella R. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. report of three cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;14:1020-1022. - Katoh

M, Nomura T, Miyachi Y, et al. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis: a review of the Japanese published works. J Dermatol. 2013;40:15-20. - Keida

T, Hayashi N, Kawashima M. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis following autologous peripheral blood stem-cell transplant. J Dermatol. 2004;31:21-26. - Goiriz R, Gul-Millán G, Peñas PF, et al. Eosinophilic folliculitis following allogeneic peripheral blood stem cell transplantation: case report and review. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34(suppl 1):33-36.

- Satoh T, Ikeda H, Yokozeki H. Acrosyringeal involvement of palmoplantar lesions of eosinophilic pustular folliculitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2013;93:99.

- Tsuboi H, Wakita K, Fujimura T, et al. Acral variant of eosinophilic pustular folliculitis (Ofuji’s disease). Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28:321-324.

- Nakahig

ashi K, Doi H, Otsuka A, et al. PGD2 induces eotaxin-3 via PPARgamma from sebocytes: a possible pathogenesis of eosinophilic pustular folliculitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:536-543. - Satoh

T, Shimura C, Miyagishi C, et al. Indomethacin-induced reduction in CRTH2 in eosinophilic pustular folliculitis (Ofuji’s disease): a proposed mechanism of action. Acta Derm Venereol. 2010;90:18-22. - Hagiwara A, Fujimura T, Furudate S, et al. Induction of CD163(+)M2 macrophages in the lesional skin of eosinophilic pustular folliculitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2014;94:104-106.

- Ellis

E, Scheinfeld N. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis: a comprehensive review of treatment options. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2004;5:189-197. - Bull R

H, Harland CA, Fallowfield ME, et al. Eosinophilic folliculitis: a self-limiting illness in patients being treated for haematological malignancy. Br J Dermatol. 1993;129:178-182. - Farber M, Forgia S, Sahu J, et al. Eosinophilic dermatosis of hematologic malignancy. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:690-695.

- Nervi J, Stephen. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis: a 40 year retrospect. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:285-289.

- Hernández-Martín Á, Nuño-González A, Colmenero I, et al. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis of infancy: a series of 15 cases and review of the literature [published online July 21, 2012]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:150-155.

- Soepr

ono F, Schinella R. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. report of three cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;14:1020-1022. - Katoh

M, Nomura T, Miyachi Y, et al. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis: a review of the Japanese published works. J Dermatol. 2013;40:15-20. - Keida

T, Hayashi N, Kawashima M. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis following autologous peripheral blood stem-cell transplant. J Dermatol. 2004;31:21-26. - Goiriz R, Gul-Millán G, Peñas PF, et al. Eosinophilic folliculitis following allogeneic peripheral blood stem cell transplantation: case report and review. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34(suppl 1):33-36.

- Satoh T, Ikeda H, Yokozeki H. Acrosyringeal involvement of palmoplantar lesions of eosinophilic pustular folliculitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2013;93:99.

- Tsuboi H, Wakita K, Fujimura T, et al. Acral variant of eosinophilic pustular folliculitis (Ofuji’s disease). Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28:321-324.

- Nakahig

ashi K, Doi H, Otsuka A, et al. PGD2 induces eotaxin-3 via PPARgamma from sebocytes: a possible pathogenesis of eosinophilic pustular folliculitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:536-543. - Satoh

T, Shimura C, Miyagishi C, et al. Indomethacin-induced reduction in CRTH2 in eosinophilic pustular folliculitis (Ofuji’s disease): a proposed mechanism of action. Acta Derm Venereol. 2010;90:18-22. - Hagiwara A, Fujimura T, Furudate S, et al. Induction of CD163(+)M2 macrophages in the lesional skin of eosinophilic pustular folliculitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2014;94:104-106.

- Ellis

E, Scheinfeld N. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis: a comprehensive review of treatment options. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2004;5:189-197. - Bull R

H, Harland CA, Fallowfield ME, et al. Eosinophilic folliculitis: a self-limiting illness in patients being treated for haematological malignancy. Br J Dermatol. 1993;129:178-182. - Farber M, Forgia S, Sahu J, et al. Eosinophilic dermatosis of hematologic malignancy. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:690-695.

Practice Points

- Recalcitrant folliculocentric papules and pustules involving the head, trunk, arms, and legs should raise suspicion of possible eosinophilic pustular folliculitis (EPF).

- Underlying hematopoietic malignancy may be associated with cases of EPF.

Rapidly Growing Scalp Nodule

Cutaneous Metastasis of Pulmonary Adenocarcinoma

Cutaneous metastasis of pulmonary adenocarcinoma (CMPA) is a rare phenomenon with an overall survival rate of less than 5 months.1,2 Often, CMPA can be the heralding feature of an aggressive systemic malignancy in 2.8% to 22% of reported cases.2-4 Clinically, CMPAs often present as fixed, violaceous, ulcerated nodules on the chest wall, scalp, or site of a prior procedure.3,5,6 Other clinical presentations have been described including zosteriform and inflammatory carcinomalike CMPA and CMPA on the tip of the nose.7 Histologically, CMPA presents as a subdermal collection of atypical glands arranged as clustered aggregates of infiltrative glands penetrating the dermal stroma (quiz image). The atypical glands have large oval nuclei with high nuclear to cytoplasm ratios with scant pale cytoplasm.

Cutaneous metastasis of pulmonary adenocarcinoma is difficult to distinguish from other metastatic or primary glandular malignancies based on histology alone. Immunohistochemical analysis can aid in the diagnosis of the primary tumor. Pulmonary adenocarcinomas are positive for cytokeratin (CK) 7 and thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF-1), and they are negative for CK5/6 and CK20.7 The differential diagnosis for CMPA includes other internal malignancies such as invasive ductal adenocarcinoma of the breast and gastrointestinal adenocarcinomas (eg, gastric or colorectal carcinoma [CRC]). Additionally, endometriosis and primary sebaceous carcinomas can mimic cutaneous metastatic adenocarcinomas.

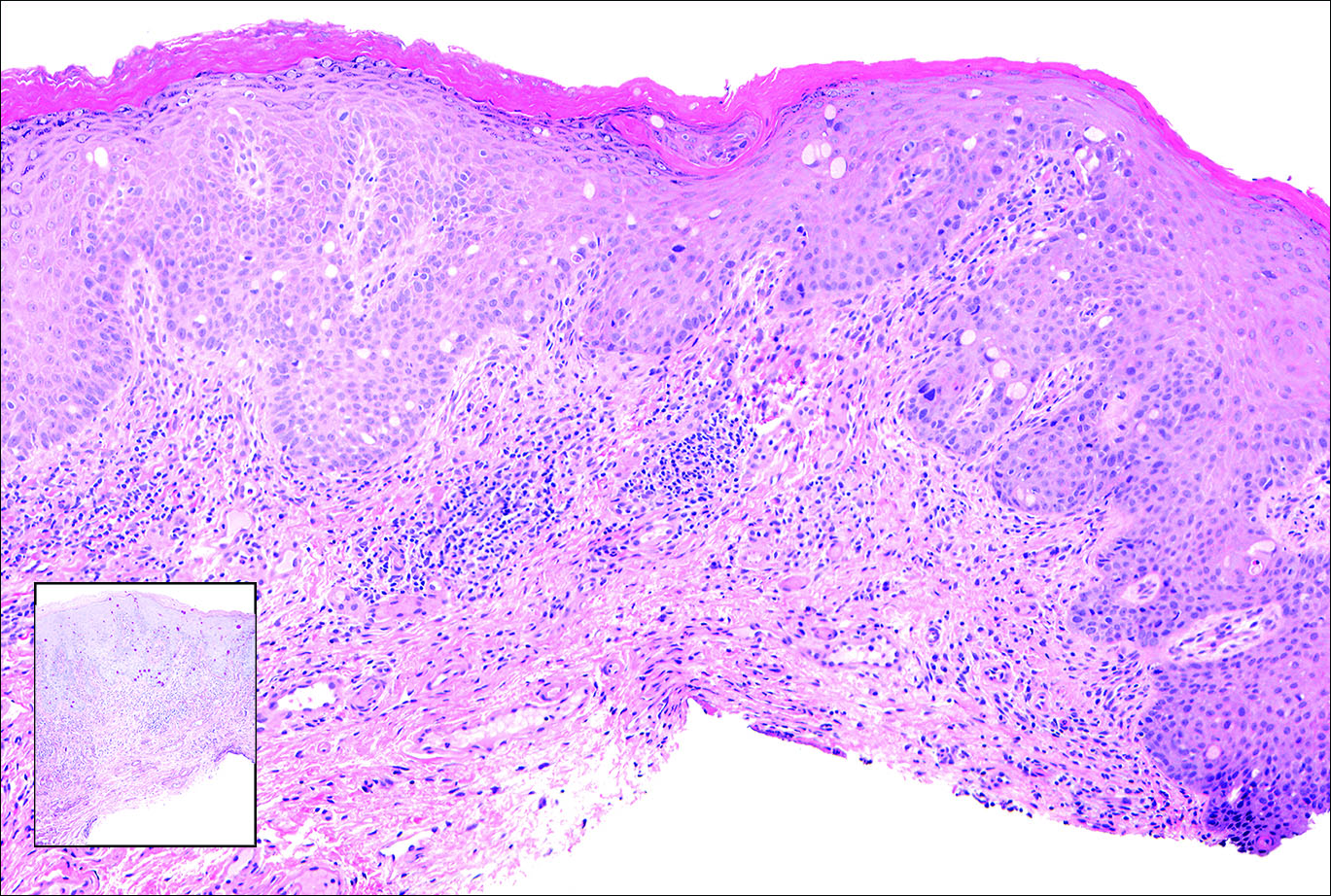

Endometriosis can mimic adenocarcinoma, especially when presenting as a subdermal nodule. However, the scattered dermal glands are cytologically banal and are surrounded by uterine-type stroma and extravasated hemorrhage, a classic presentation of endometriosis (Figure 1).

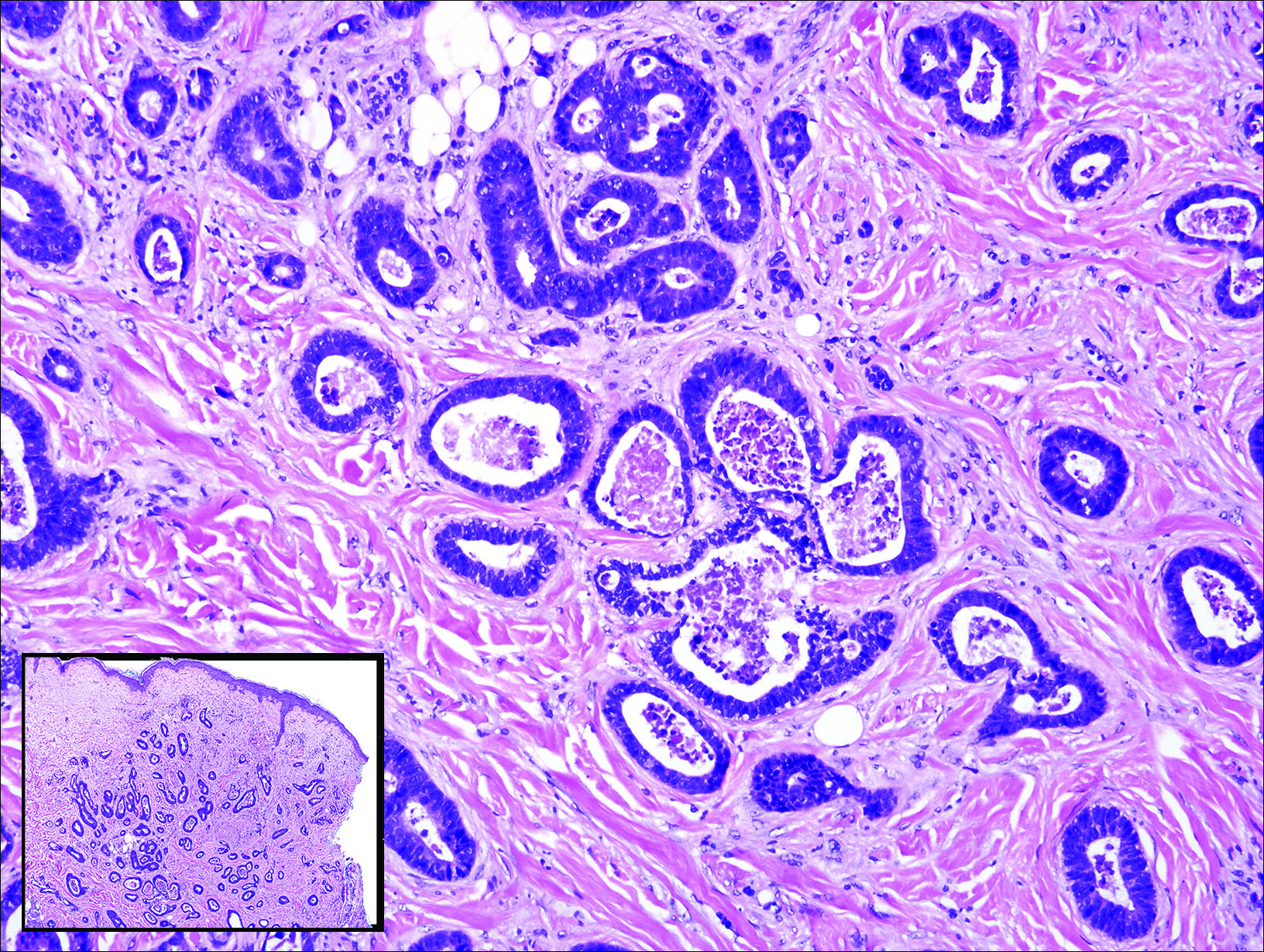

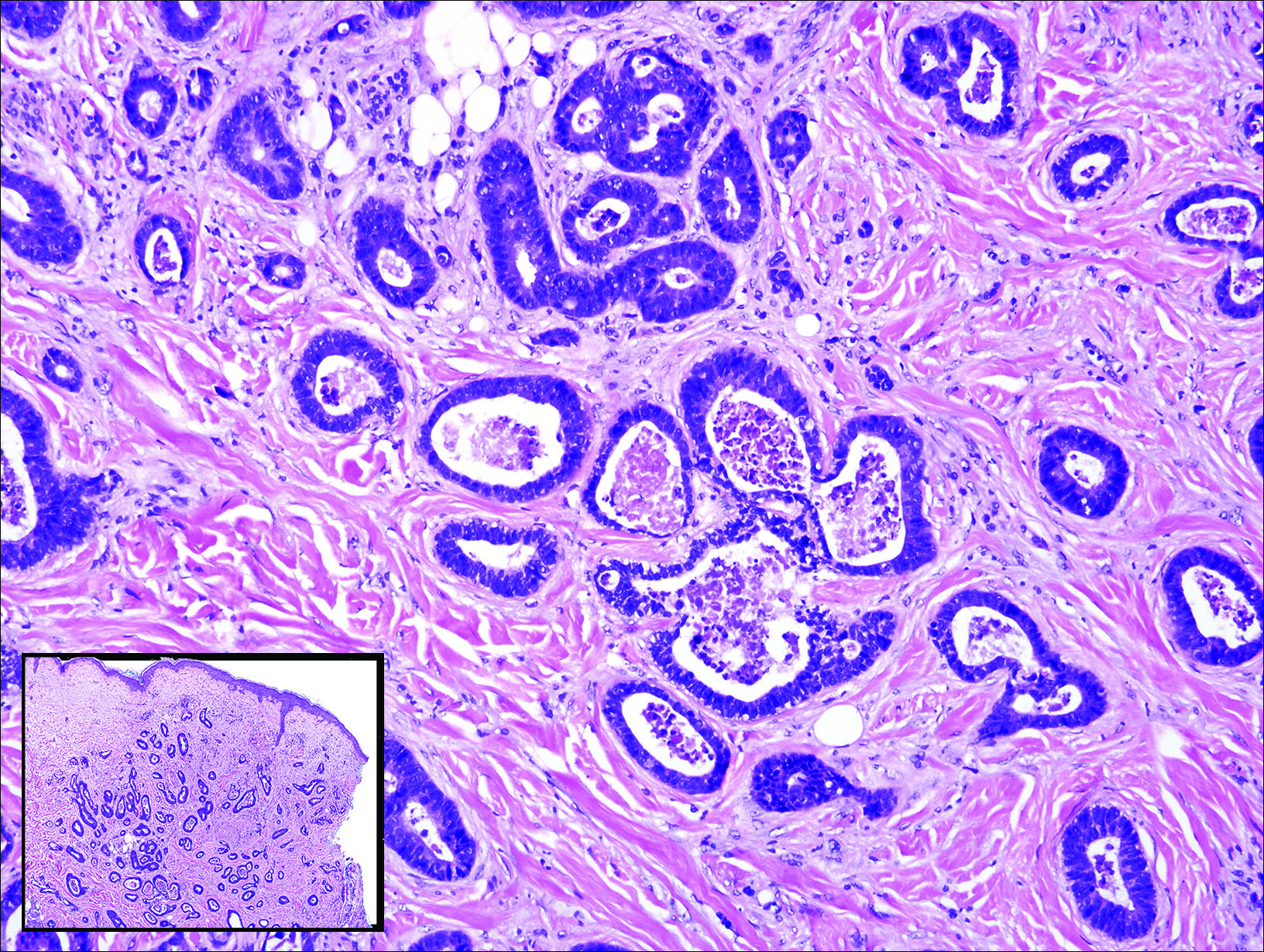

Invasive ductal carcinoma of the breast is one of the most common cutaneous metastases of internal malignancy.3 Clinically, these lesions present on the chest wall or abdomen as flesh-colored nodules. Histopathology generally reveals either tubular or single tumor cells infiltrating the dermis with surrounding desmoplastic fibrosis (Figure 2). Immunohistochemistry typically is positive for CK7, estrogen receptor, and mammaglobin, and negative for CK20, CK5/6, and TTF-1.

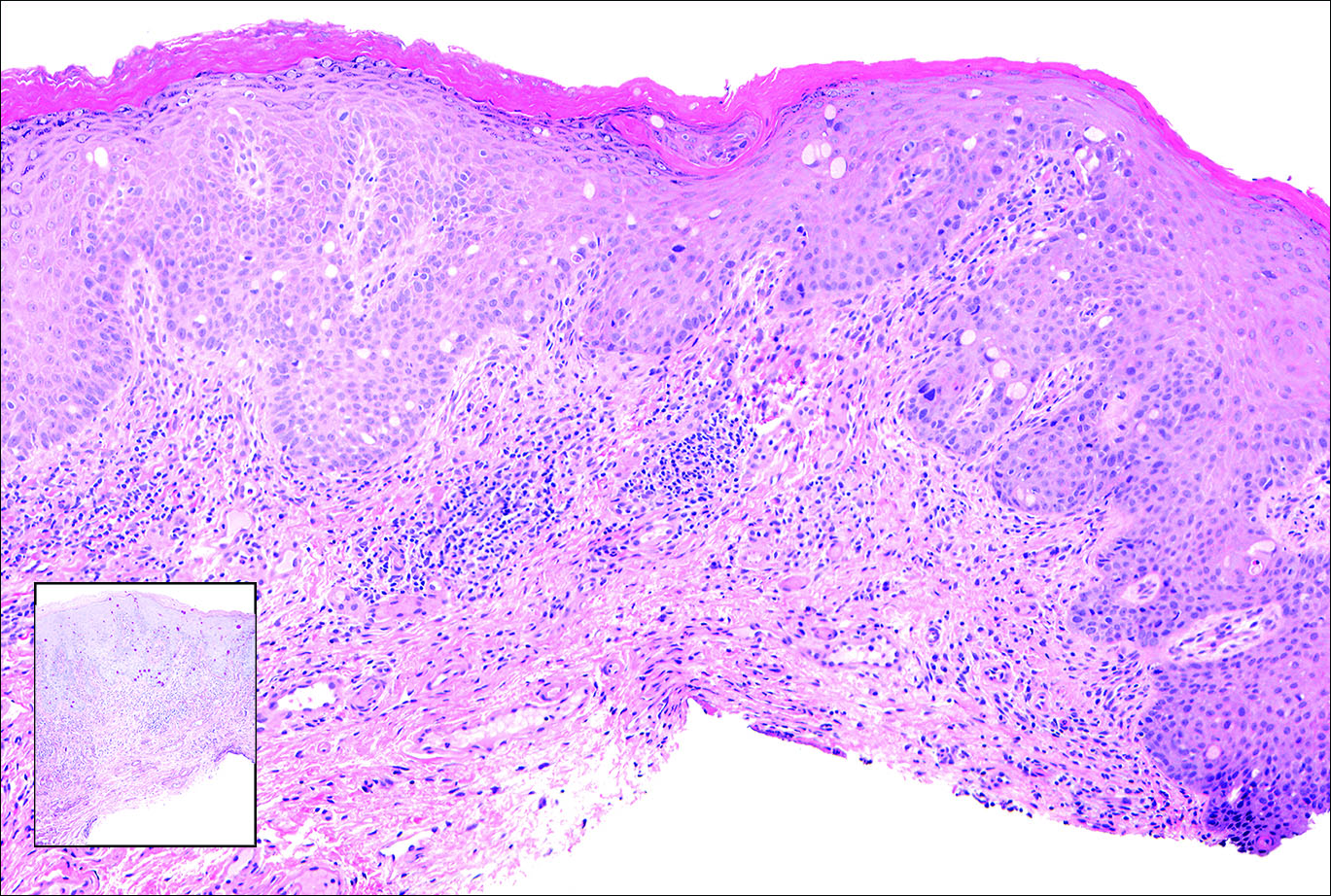

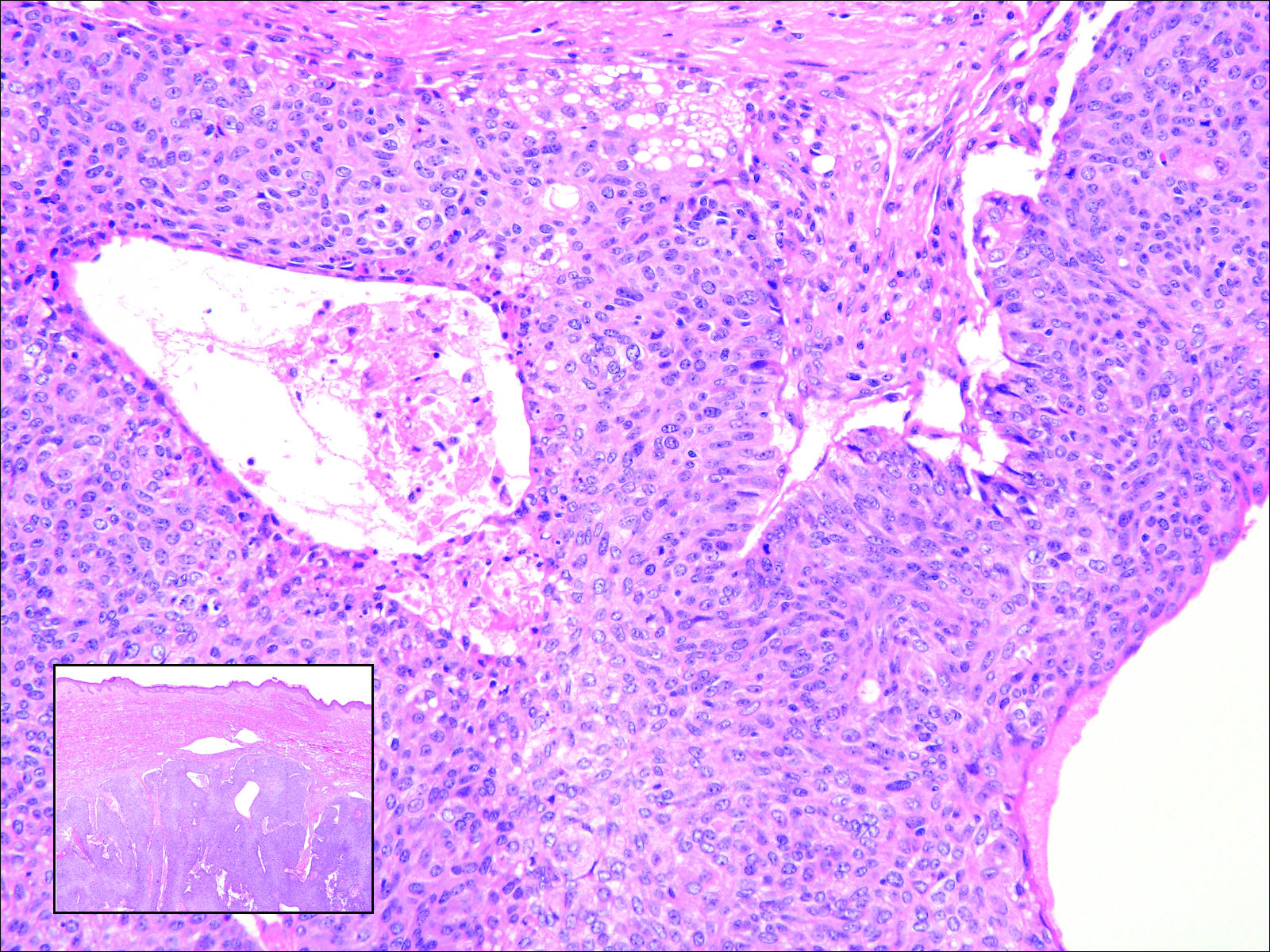

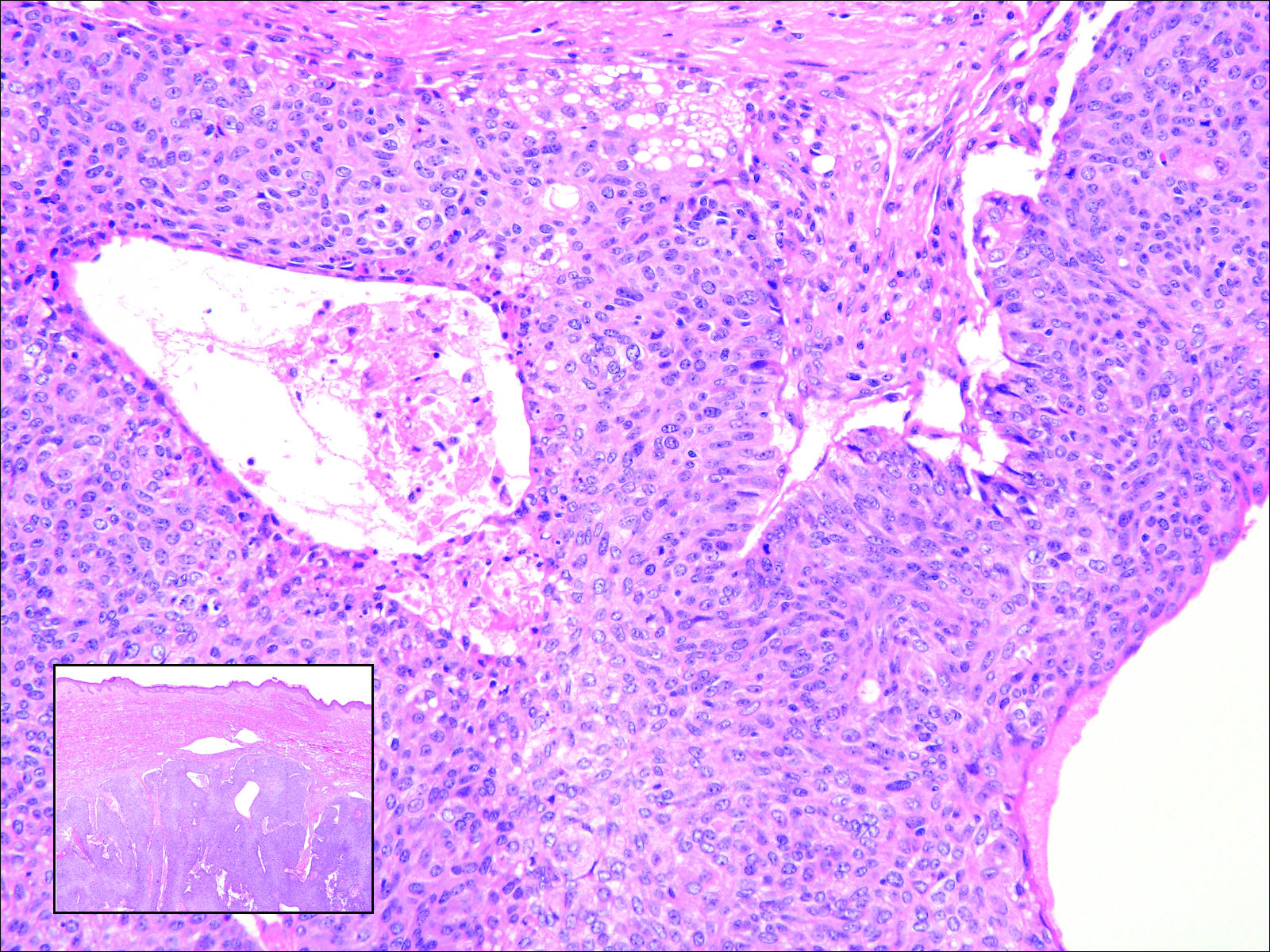

Gastrointestinal adenocarcinomas encompass a variety of primary sites that can metastasize to the skin including CRC. Clinically, cutaneous metastases of CRC present as multiple nodules on the trunk, abdomen, or umbilicus (also known as Sister Mary Joseph nodule).7,8 Distinguishing CRC as the primary site of origin can be difficult; however, there are subtle differences depending on the histologic subtype. In well-differentiated CRCs, well-defined atypical glands are haphazardly arranged within the dermis (Figure 3), while poorly differentiated lesions can present as single cells or with a signet ring-like morphology (Figure 4). For perianal lesions, extramammary Paget disease should be considered when biopsies show large, amphophilic, intraepithelial cells. These lesions often present with mucin and CK20 expression and are frequently associated with colorectal malignancies.9 Another characteristic feature of CRC is central necrosis with karyorrhectic debris, known as dirty necrosis. Immunohistochemical analysis typically shows expression of caudal type homeobox 2 and CK20 with infrequent expression of CK7 and no expression of TTF-1; however, additional clinical history (eg, history of colorectal adenocarcinoma, positive fecal occult blood test) often is the best distinguishing feature.

Primary sebaceous carcinoma also can mimic metastatic adenocarcinoma within the skin and is histologically similar to metastatic adenocarcinomas. The most distinguishing feature is sebaceous differentiation characterized by sebocytes, which have a vacuolated cytoplasm giving the nucleus a scalloped appearance, frequently with adjacent ductlike structures (Figure 5). Epidermotropism sometimes is present in sebaceous carcinomas but cannot be relied on as a distinguishing feature. Immunohistochemical analysis also is a helpful tool; these tumors typically are positive for p63 and podoplanin, distinguishing them from negative-staining metastatic adenocarcinomas.10,11

- Terashima T, Kanazawa M. Lung cancer with skin metastasis. Chest. 1994;106:1448-1450.

- Song Z, Lin B, Shao L, et al. Cutaneous metastasis as a initial presentation in advanced non-small cell lung cancer and its poor survival prognosis. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2012;138:1613-1617.

- Lookingbill DP, Spangler N, Helm KF. Cutaneous metastases in patients with metastatic carcinoma: a retrospective study of 4020 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29(2, pt 1):228-236.

- Saeed S, Keehn CA, Morgan MB. Cutaneous metastasis: a clinical, pathological, and immunohistochemical appraisal. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31:419-430.

- Chang SE, Choi JC, Moon KC. A papillary carcinoma: cutaneous metastases from lung cancer. J Dermatol. 2001;28:110-111.

- Snow S, Madjar D, Reizner G, et al. Renal cell carcinoma metastatic to the scalp: case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 2001;27:192-194.

- Alcaraz I, Cerroni L, Rutten A, et al. Cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:347-393.

- Schwartz IS. Sister (Mary?) Joseph's nodule. N Engl J Med. 1987;316:1348-1349.

- Goldblum J, Hart W. Perianal Paget's disease: a histologic and immunohistochemical study of 11 cases with and without associated rectal adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:170-179.

- Ivan D, Nash J, Preito V, et al. Use of p63 expression in distinguishing primary and metastatic cutaneous adnexal neoplasms from metastatic adenocarcinoma to skin. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;34:474-480.

- Liang H, Wu H, Giorgadze T, et al. Podoplanin is a highly sensitive and specific marker to distinguish primary skin adnexal carcinomas from adenocarcinomas metastatic to skin. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:304-310.

Cutaneous Metastasis of Pulmonary Adenocarcinoma

Cutaneous metastasis of pulmonary adenocarcinoma (CMPA) is a rare phenomenon with an overall survival rate of less than 5 months.1,2 Often, CMPA can be the heralding feature of an aggressive systemic malignancy in 2.8% to 22% of reported cases.2-4 Clinically, CMPAs often present as fixed, violaceous, ulcerated nodules on the chest wall, scalp, or site of a prior procedure.3,5,6 Other clinical presentations have been described including zosteriform and inflammatory carcinomalike CMPA and CMPA on the tip of the nose.7 Histologically, CMPA presents as a subdermal collection of atypical glands arranged as clustered aggregates of infiltrative glands penetrating the dermal stroma (quiz image). The atypical glands have large oval nuclei with high nuclear to cytoplasm ratios with scant pale cytoplasm.

Cutaneous metastasis of pulmonary adenocarcinoma is difficult to distinguish from other metastatic or primary glandular malignancies based on histology alone. Immunohistochemical analysis can aid in the diagnosis of the primary tumor. Pulmonary adenocarcinomas are positive for cytokeratin (CK) 7 and thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF-1), and they are negative for CK5/6 and CK20.7 The differential diagnosis for CMPA includes other internal malignancies such as invasive ductal adenocarcinoma of the breast and gastrointestinal adenocarcinomas (eg, gastric or colorectal carcinoma [CRC]). Additionally, endometriosis and primary sebaceous carcinomas can mimic cutaneous metastatic adenocarcinomas.

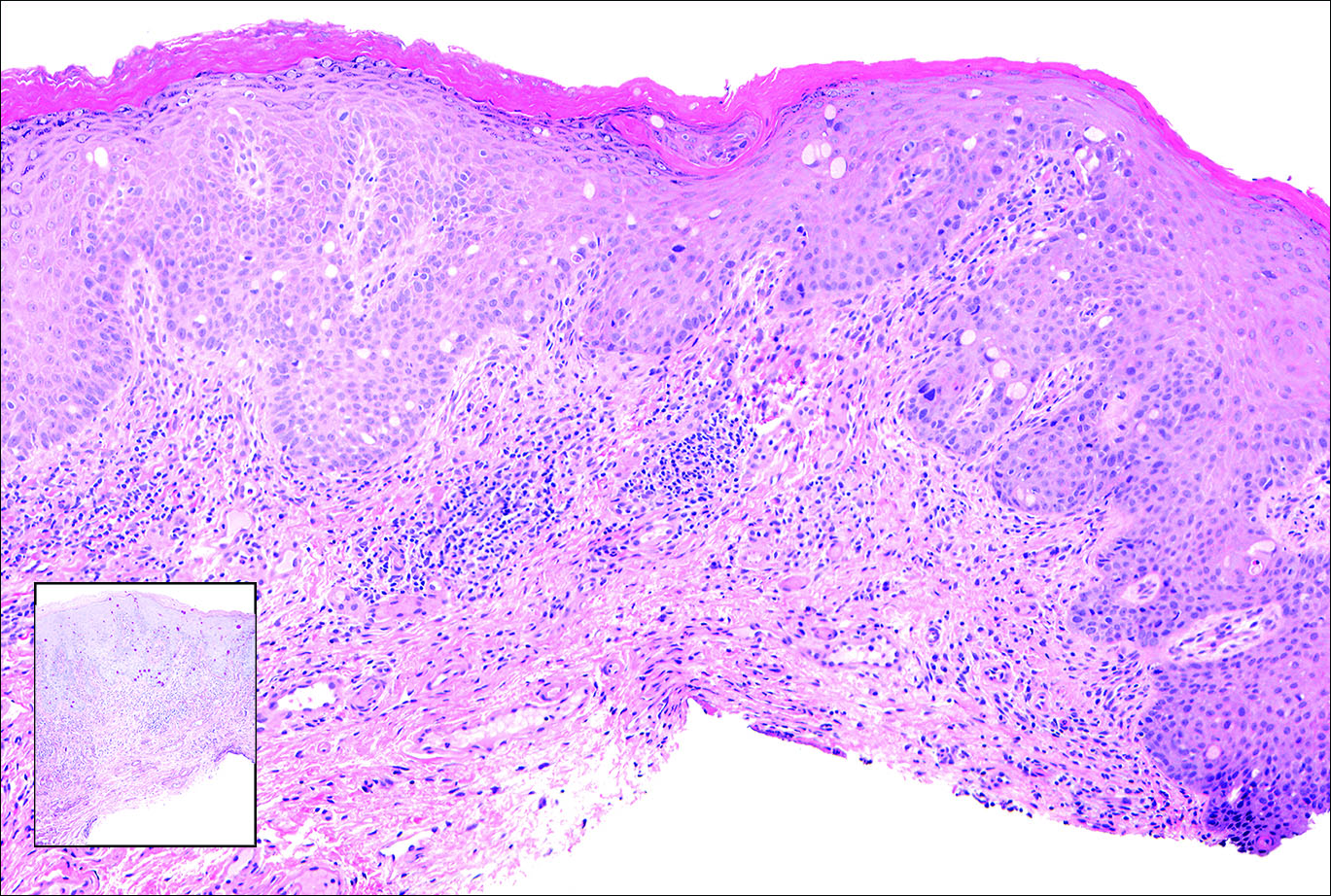

Endometriosis can mimic adenocarcinoma, especially when presenting as a subdermal nodule. However, the scattered dermal glands are cytologically banal and are surrounded by uterine-type stroma and extravasated hemorrhage, a classic presentation of endometriosis (Figure 1).

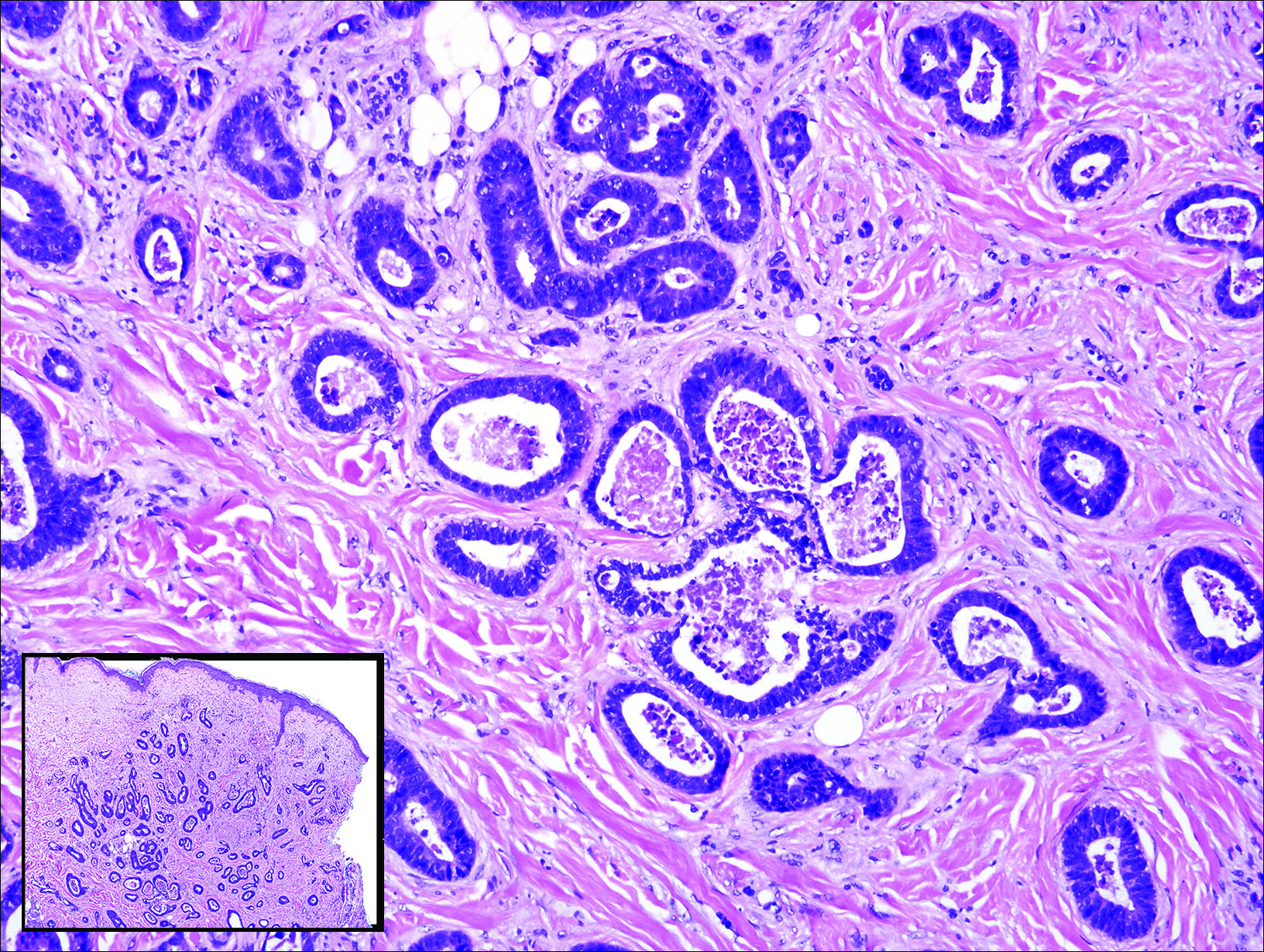

Invasive ductal carcinoma of the breast is one of the most common cutaneous metastases of internal malignancy.3 Clinically, these lesions present on the chest wall or abdomen as flesh-colored nodules. Histopathology generally reveals either tubular or single tumor cells infiltrating the dermis with surrounding desmoplastic fibrosis (Figure 2). Immunohistochemistry typically is positive for CK7, estrogen receptor, and mammaglobin, and negative for CK20, CK5/6, and TTF-1.

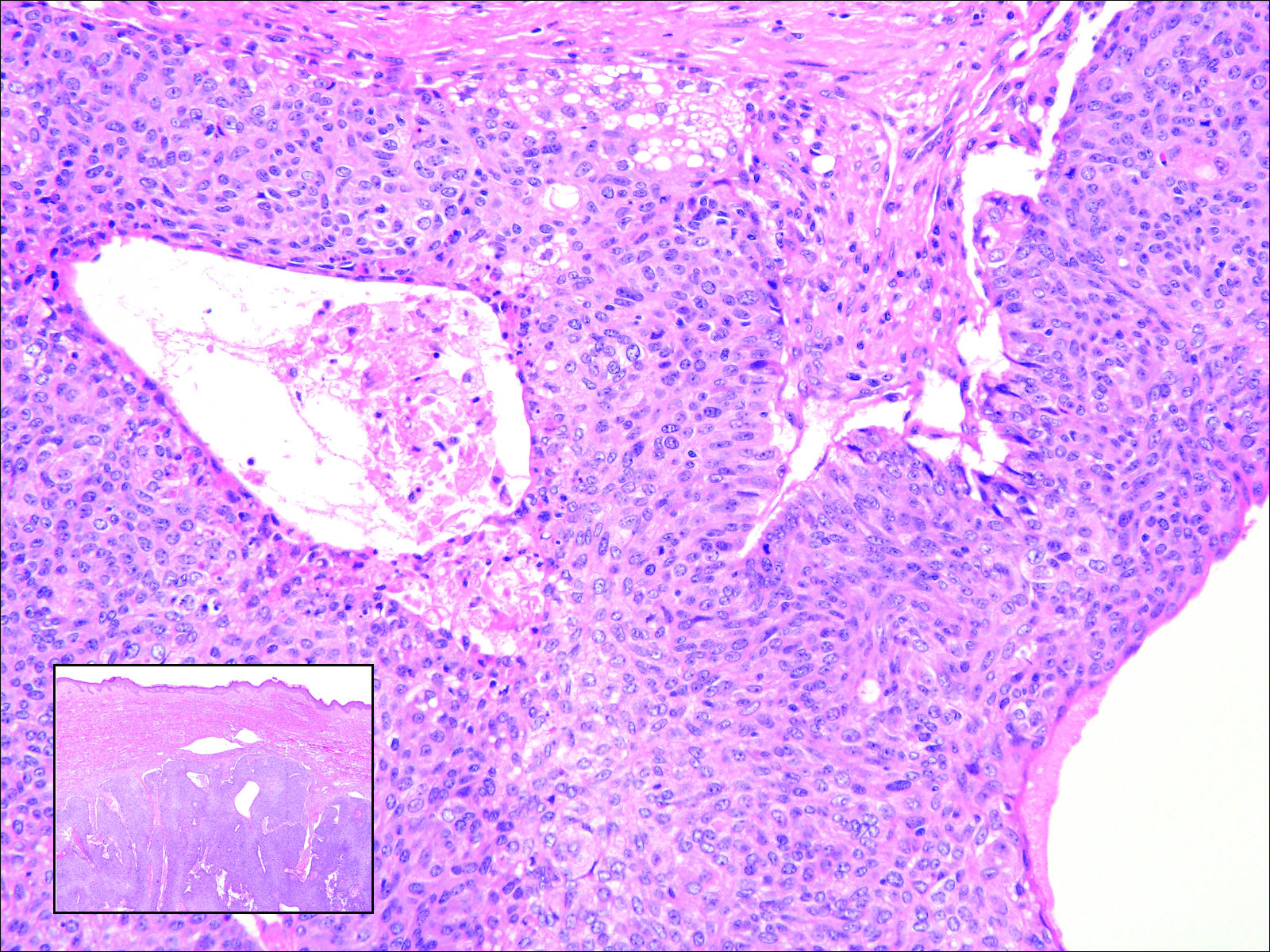

Gastrointestinal adenocarcinomas encompass a variety of primary sites that can metastasize to the skin including CRC. Clinically, cutaneous metastases of CRC present as multiple nodules on the trunk, abdomen, or umbilicus (also known as Sister Mary Joseph nodule).7,8 Distinguishing CRC as the primary site of origin can be difficult; however, there are subtle differences depending on the histologic subtype. In well-differentiated CRCs, well-defined atypical glands are haphazardly arranged within the dermis (Figure 3), while poorly differentiated lesions can present as single cells or with a signet ring-like morphology (Figure 4). For perianal lesions, extramammary Paget disease should be considered when biopsies show large, amphophilic, intraepithelial cells. These lesions often present with mucin and CK20 expression and are frequently associated with colorectal malignancies.9 Another characteristic feature of CRC is central necrosis with karyorrhectic debris, known as dirty necrosis. Immunohistochemical analysis typically shows expression of caudal type homeobox 2 and CK20 with infrequent expression of CK7 and no expression of TTF-1; however, additional clinical history (eg, history of colorectal adenocarcinoma, positive fecal occult blood test) often is the best distinguishing feature.

Primary sebaceous carcinoma also can mimic metastatic adenocarcinoma within the skin and is histologically similar to metastatic adenocarcinomas. The most distinguishing feature is sebaceous differentiation characterized by sebocytes, which have a vacuolated cytoplasm giving the nucleus a scalloped appearance, frequently with adjacent ductlike structures (Figure 5). Epidermotropism sometimes is present in sebaceous carcinomas but cannot be relied on as a distinguishing feature. Immunohistochemical analysis also is a helpful tool; these tumors typically are positive for p63 and podoplanin, distinguishing them from negative-staining metastatic adenocarcinomas.10,11

Cutaneous Metastasis of Pulmonary Adenocarcinoma

Cutaneous metastasis of pulmonary adenocarcinoma (CMPA) is a rare phenomenon with an overall survival rate of less than 5 months.1,2 Often, CMPA can be the heralding feature of an aggressive systemic malignancy in 2.8% to 22% of reported cases.2-4 Clinically, CMPAs often present as fixed, violaceous, ulcerated nodules on the chest wall, scalp, or site of a prior procedure.3,5,6 Other clinical presentations have been described including zosteriform and inflammatory carcinomalike CMPA and CMPA on the tip of the nose.7 Histologically, CMPA presents as a subdermal collection of atypical glands arranged as clustered aggregates of infiltrative glands penetrating the dermal stroma (quiz image). The atypical glands have large oval nuclei with high nuclear to cytoplasm ratios with scant pale cytoplasm.

Cutaneous metastasis of pulmonary adenocarcinoma is difficult to distinguish from other metastatic or primary glandular malignancies based on histology alone. Immunohistochemical analysis can aid in the diagnosis of the primary tumor. Pulmonary adenocarcinomas are positive for cytokeratin (CK) 7 and thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF-1), and they are negative for CK5/6 and CK20.7 The differential diagnosis for CMPA includes other internal malignancies such as invasive ductal adenocarcinoma of the breast and gastrointestinal adenocarcinomas (eg, gastric or colorectal carcinoma [CRC]). Additionally, endometriosis and primary sebaceous carcinomas can mimic cutaneous metastatic adenocarcinomas.

Endometriosis can mimic adenocarcinoma, especially when presenting as a subdermal nodule. However, the scattered dermal glands are cytologically banal and are surrounded by uterine-type stroma and extravasated hemorrhage, a classic presentation of endometriosis (Figure 1).

Invasive ductal carcinoma of the breast is one of the most common cutaneous metastases of internal malignancy.3 Clinically, these lesions present on the chest wall or abdomen as flesh-colored nodules. Histopathology generally reveals either tubular or single tumor cells infiltrating the dermis with surrounding desmoplastic fibrosis (Figure 2). Immunohistochemistry typically is positive for CK7, estrogen receptor, and mammaglobin, and negative for CK20, CK5/6, and TTF-1.

Gastrointestinal adenocarcinomas encompass a variety of primary sites that can metastasize to the skin including CRC. Clinically, cutaneous metastases of CRC present as multiple nodules on the trunk, abdomen, or umbilicus (also known as Sister Mary Joseph nodule).7,8 Distinguishing CRC as the primary site of origin can be difficult; however, there are subtle differences depending on the histologic subtype. In well-differentiated CRCs, well-defined atypical glands are haphazardly arranged within the dermis (Figure 3), while poorly differentiated lesions can present as single cells or with a signet ring-like morphology (Figure 4). For perianal lesions, extramammary Paget disease should be considered when biopsies show large, amphophilic, intraepithelial cells. These lesions often present with mucin and CK20 expression and are frequently associated with colorectal malignancies.9 Another characteristic feature of CRC is central necrosis with karyorrhectic debris, known as dirty necrosis. Immunohistochemical analysis typically shows expression of caudal type homeobox 2 and CK20 with infrequent expression of CK7 and no expression of TTF-1; however, additional clinical history (eg, history of colorectal adenocarcinoma, positive fecal occult blood test) often is the best distinguishing feature.

Primary sebaceous carcinoma also can mimic metastatic adenocarcinoma within the skin and is histologically similar to metastatic adenocarcinomas. The most distinguishing feature is sebaceous differentiation characterized by sebocytes, which have a vacuolated cytoplasm giving the nucleus a scalloped appearance, frequently with adjacent ductlike structures (Figure 5). Epidermotropism sometimes is present in sebaceous carcinomas but cannot be relied on as a distinguishing feature. Immunohistochemical analysis also is a helpful tool; these tumors typically are positive for p63 and podoplanin, distinguishing them from negative-staining metastatic adenocarcinomas.10,11

- Terashima T, Kanazawa M. Lung cancer with skin metastasis. Chest. 1994;106:1448-1450.

- Song Z, Lin B, Shao L, et al. Cutaneous metastasis as a initial presentation in advanced non-small cell lung cancer and its poor survival prognosis. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2012;138:1613-1617.

- Lookingbill DP, Spangler N, Helm KF. Cutaneous metastases in patients with metastatic carcinoma: a retrospective study of 4020 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29(2, pt 1):228-236.

- Saeed S, Keehn CA, Morgan MB. Cutaneous metastasis: a clinical, pathological, and immunohistochemical appraisal. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31:419-430.

- Chang SE, Choi JC, Moon KC. A papillary carcinoma: cutaneous metastases from lung cancer. J Dermatol. 2001;28:110-111.

- Snow S, Madjar D, Reizner G, et al. Renal cell carcinoma metastatic to the scalp: case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 2001;27:192-194.

- Alcaraz I, Cerroni L, Rutten A, et al. Cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:347-393.

- Schwartz IS. Sister (Mary?) Joseph's nodule. N Engl J Med. 1987;316:1348-1349.

- Goldblum J, Hart W. Perianal Paget's disease: a histologic and immunohistochemical study of 11 cases with and without associated rectal adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:170-179.

- Ivan D, Nash J, Preito V, et al. Use of p63 expression in distinguishing primary and metastatic cutaneous adnexal neoplasms from metastatic adenocarcinoma to skin. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;34:474-480.

- Liang H, Wu H, Giorgadze T, et al. Podoplanin is a highly sensitive and specific marker to distinguish primary skin adnexal carcinomas from adenocarcinomas metastatic to skin. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:304-310.

- Terashima T, Kanazawa M. Lung cancer with skin metastasis. Chest. 1994;106:1448-1450.

- Song Z, Lin B, Shao L, et al. Cutaneous metastasis as a initial presentation in advanced non-small cell lung cancer and its poor survival prognosis. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2012;138:1613-1617.

- Lookingbill DP, Spangler N, Helm KF. Cutaneous metastases in patients with metastatic carcinoma: a retrospective study of 4020 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29(2, pt 1):228-236.

- Saeed S, Keehn CA, Morgan MB. Cutaneous metastasis: a clinical, pathological, and immunohistochemical appraisal. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31:419-430.

- Chang SE, Choi JC, Moon KC. A papillary carcinoma: cutaneous metastases from lung cancer. J Dermatol. 2001;28:110-111.

- Snow S, Madjar D, Reizner G, et al. Renal cell carcinoma metastatic to the scalp: case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 2001;27:192-194.

- Alcaraz I, Cerroni L, Rutten A, et al. Cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:347-393.

- Schwartz IS. Sister (Mary?) Joseph's nodule. N Engl J Med. 1987;316:1348-1349.

- Goldblum J, Hart W. Perianal Paget's disease: a histologic and immunohistochemical study of 11 cases with and without associated rectal adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:170-179.

- Ivan D, Nash J, Preito V, et al. Use of p63 expression in distinguishing primary and metastatic cutaneous adnexal neoplasms from metastatic adenocarcinoma to skin. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;34:474-480.

- Liang H, Wu H, Giorgadze T, et al. Podoplanin is a highly sensitive and specific marker to distinguish primary skin adnexal carcinomas from adenocarcinomas metastatic to skin. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:304-310.

A 67-year-old woman with no history of malignancy presented with a scalp nodule. The photomicrograph showed atypical glands forming a subepidermal nodule with pleomorphic cells characterized by scant eosinophilic cytoplasm and large prominent nucleoli. Immunohistochemical analysis revealed diffuse thyroid transcription factor 1 and cytokeratin 7 positivity.