User login

The Bad Hire

Hospital medicine groups depend on camaraderie and expertise to carry them through long days and heavy workloads. Group cohesiveness—often fragile—depends on recruiting and keeping hard-working doctors who pull their weight professionally and boost the group’s chemistry.

In a field with five job openings for every qualified candidate, and average annual turnover at 12%, hospital medicine groups can ill afford a bad hire. Whether that person is a practice killer, a cipher who blends into the wallpaper while collecting a paycheck, or a doctor marking time until a fellowship or something better comes along, the group leader must quickly limit a bad hire’s negative impact.

Recognizing that competition to hire hospitalists is fierce, it may seem that avoiding or axing a bad hire—the physician who either doesn’t mesh with your team, is a professional and/or personal train wreck, or has a blue-ribbon pedigree, but performs poorly—is a luxury hospitalist groups can’t afford.

But as Per Danielsson, MD, medical director of Seattle-based Swedish Medical Center’s adult hospitalist program has learned the hard way: “No doctor is better than the wrong doctor. I don’t sugarcoat the demands of our program with prospects. We’re a seasoned hospitalist program, we work hard, and, if we have a position vacant, we’ll work even harder for short periods of time until we find the right person.”

With a hospitalist group of 25 providers, Dr. Danielsson spends more time than he’d like recruiting and interviewing candidates, but he considers it time well spent. “The CV and interview are important, but I’ve devised a list of 12 personality traits that I consider important,” he says. “I share the list with candidates to see if we have a good fit.”

Chris Nussbaum, MD, CEO of Synergy Medical Group, based in Brandon, Fla., says: “They don’t make doctors the way they used to. I don’t see why some hospitalists think seeing 20 to 25 patients a day is such a big deal. I’ve had several tell me that 20 patients a day is no problem—and then they only last one day.” When that happens, Synergy cuts its losses, not allowing a bad hire to linger.

Dr. Nussbaum didn’t think twice about firing one new hire—a physician with an impressive resume who, while writing chart notes at a nursing station, watched a nurse have a seizure, gathered his notes and left the room. “He expected an endocrinologist standing nearby to help out, but it’s outrageous that any hospitalist wouldn’t respond appropriately,” he says. Such callous behavior would send shock waves through any group, and that physician was fired on the spot.

Another organizational disrupter, briefly employed by IPC-the Hospitalist Company (North Hollywood, Calif.) made inflammatory remarks about a hospital’s pre-eminent specialist and other referring physicians. He was fired. Several hospitalist leaders report hiring physicians with stellar pedigrees whose hands consistently strayed to nurses’ derrieres. Those doctors were quickly shown the door.

Robin Ryan, a career coach from Newcastle, Wash., who has prepared office-based physicians for professional moves to hospitalist careers, says the new career path can be confusing. When a physician and a hospitalist group have made a mistake, Ryan says most groups cut their losses by terminating someone who doesn’t fit. “Contracts often require a hefty severance fee, but it’s often the road that groups take,” she says.

Probing Personality

To weed out potential bad hires, employees long have used personality tests. Such tests also help job candidates clarify what matters most to them professionally. The SHM’s Career Satisfaction Task Force has developed a framework for hospitalists to do that. The self-test rests on four pillars of job satisfaction: reward/recognition, workload/schedule, autonomy/control, and community/environment (to view, go to www.hospitalmedicine.org and click “Career Satisfaction White Paper”).

Sylvia McKean, MD, medical director, the Brigham & Women’s Hospital/Faulkner Hospitalist Program in Boston and the task force’s co-chair, urges hospitalists to complete the self-test to maximize a potential job fit.

“All jobs have unpleasant side effects,” says Dr. McKean. “People get sick at bad times. There is high stress and sometimes high error rates. It’s important for a hospitalist to analyze what your needs are and to find an environment that best suits them.”

Dr. McKean also offers wisdom from the other side of desk, having interviewed candidates for coveted spots at Brigham & Women’s hospitalist program. “I’ve interviewed doctors who aren’t interested in hospitalist medicine but view our program as a stepping stone to the job they really want here,’’ she says. “We hired and fired someone who wanted her own way all the time. She left for another prestigious hospital. Then there are others who don’t want to teach, but choose a teaching hospital.”

Dr. McKean hopes SHM’s self-assessment tools will help job candidates focus on what they want from a hospital medicine group and avoid the “pebbles” that erode job satisfaction.

IPC, which employs 600 physicians in 100 practices in 24 markets, tried personality testing then discarded it. IPC hired a psychometric firm to devise a psychological profile of “best” and “worst” performing hospitalists. The testers created a test measuring seven key characteristics relating to temperament, intelligence, and clinical skills.

IPC’s CEO Adam Singer, MD, says: “We tested all candidates but found the test ineffective because nearly everyone, including me, got five or better.” He dropped the test, relying instead on extensive interviews. Dr. Singer reviews 2,500 to 3,000 physician resumes annually and spends significant resources on avoiding bad hires. All that hard work doesn’t avoid the occasional mistake.

“I’ve seen everything—the brilliant doctor who can’t function on a team, aloofness, temper tantrums, rudeness, and always pushing responsibility on someone else,” says Dr. Singer. “When something’s wrong, 90% of the time we terminate them ASAP. The other 10% we salvage by finding what’s stressing them, relieving the pressure, and mentoring them into proper behavior.”

Cynthia Stamer, a Dallas-based attorney at Glast, Phillips & Murray, P.C., works extensively with physicians and hospitals and sees young physicians straight from residency joining hospitalist programs “just looking for a job and not focused on whether or not there’s a good personality fit.” She urges job candidates and hirers to better probe the fit.

Stamer finds good hospitalists to be stress jockeys who thrive on the intensity of hospital work. “I think they’re born and not bred,” she says. “They tend to be bored or disruptive in office practices, and to enjoy a pattern of work hard, play hard. The ability to throw the ‘on’ switch and be intense for block scheduling, then be ‘off’ for a block suits them,” she says.

Not That Bad

In a field where an extra pair of hands can make the difference between taking night call or the freedom to take several days off for emergencies, a mediocre team member might seem better than none. Some hospitalist groups would rather pull a bigger load temporarily than tolerate a laggard; others stomach imperfection.

Spotting problems during the hiring process can turn a bad hire into a proper fit. For example, offering a permanent part-time position to someone with young children who can’t commit to full-time employment avoids potential problems. Or, asking enough probing questions might help you discover a physician has a year before a coveted fellowship begins; tailoring a one-year contract for that person optimizes fit. Eliminating managerial tasks for a pure clinician who eschews the leadership fast track works, too.

What to do with the mediocre performer rather than the egregious misfit? Perhaps she consistently arrives to work late, doesn’t complete her charts, and tries to avoid admissions or challenging assignments. A group leader may salvage the situation through mentoring and tying pay to performance. Dr. Singer says: “Underperformers usually don’t understand their impact on the group. We teach them healthcare economics and the flow of dollars. We train them to get the relationship between pay and performance, and hope for results.”

Stamer urges hospitalist leaders to build termination procedures into employment contracts, to document poor performance, and to give severance pay or buy out a contract with a bad hire. “People get testy around disengagement, but if you can take the heat out of the process, it’s better in the long run,” she concludes.

As hospitalist supply approaches demand, avoiding bad hires should be easier. For now, most groups prefer pulling together and working harder rather than abide an outlier. It comes with the territory. TH

Marlene Piturro is a frequent contributor to The Hospitalist.

Hospital medicine groups depend on camaraderie and expertise to carry them through long days and heavy workloads. Group cohesiveness—often fragile—depends on recruiting and keeping hard-working doctors who pull their weight professionally and boost the group’s chemistry.

In a field with five job openings for every qualified candidate, and average annual turnover at 12%, hospital medicine groups can ill afford a bad hire. Whether that person is a practice killer, a cipher who blends into the wallpaper while collecting a paycheck, or a doctor marking time until a fellowship or something better comes along, the group leader must quickly limit a bad hire’s negative impact.

Recognizing that competition to hire hospitalists is fierce, it may seem that avoiding or axing a bad hire—the physician who either doesn’t mesh with your team, is a professional and/or personal train wreck, or has a blue-ribbon pedigree, but performs poorly—is a luxury hospitalist groups can’t afford.

But as Per Danielsson, MD, medical director of Seattle-based Swedish Medical Center’s adult hospitalist program has learned the hard way: “No doctor is better than the wrong doctor. I don’t sugarcoat the demands of our program with prospects. We’re a seasoned hospitalist program, we work hard, and, if we have a position vacant, we’ll work even harder for short periods of time until we find the right person.”

With a hospitalist group of 25 providers, Dr. Danielsson spends more time than he’d like recruiting and interviewing candidates, but he considers it time well spent. “The CV and interview are important, but I’ve devised a list of 12 personality traits that I consider important,” he says. “I share the list with candidates to see if we have a good fit.”

Chris Nussbaum, MD, CEO of Synergy Medical Group, based in Brandon, Fla., says: “They don’t make doctors the way they used to. I don’t see why some hospitalists think seeing 20 to 25 patients a day is such a big deal. I’ve had several tell me that 20 patients a day is no problem—and then they only last one day.” When that happens, Synergy cuts its losses, not allowing a bad hire to linger.

Dr. Nussbaum didn’t think twice about firing one new hire—a physician with an impressive resume who, while writing chart notes at a nursing station, watched a nurse have a seizure, gathered his notes and left the room. “He expected an endocrinologist standing nearby to help out, but it’s outrageous that any hospitalist wouldn’t respond appropriately,” he says. Such callous behavior would send shock waves through any group, and that physician was fired on the spot.

Another organizational disrupter, briefly employed by IPC-the Hospitalist Company (North Hollywood, Calif.) made inflammatory remarks about a hospital’s pre-eminent specialist and other referring physicians. He was fired. Several hospitalist leaders report hiring physicians with stellar pedigrees whose hands consistently strayed to nurses’ derrieres. Those doctors were quickly shown the door.

Robin Ryan, a career coach from Newcastle, Wash., who has prepared office-based physicians for professional moves to hospitalist careers, says the new career path can be confusing. When a physician and a hospitalist group have made a mistake, Ryan says most groups cut their losses by terminating someone who doesn’t fit. “Contracts often require a hefty severance fee, but it’s often the road that groups take,” she says.

Probing Personality

To weed out potential bad hires, employees long have used personality tests. Such tests also help job candidates clarify what matters most to them professionally. The SHM’s Career Satisfaction Task Force has developed a framework for hospitalists to do that. The self-test rests on four pillars of job satisfaction: reward/recognition, workload/schedule, autonomy/control, and community/environment (to view, go to www.hospitalmedicine.org and click “Career Satisfaction White Paper”).

Sylvia McKean, MD, medical director, the Brigham & Women’s Hospital/Faulkner Hospitalist Program in Boston and the task force’s co-chair, urges hospitalists to complete the self-test to maximize a potential job fit.

“All jobs have unpleasant side effects,” says Dr. McKean. “People get sick at bad times. There is high stress and sometimes high error rates. It’s important for a hospitalist to analyze what your needs are and to find an environment that best suits them.”

Dr. McKean also offers wisdom from the other side of desk, having interviewed candidates for coveted spots at Brigham & Women’s hospitalist program. “I’ve interviewed doctors who aren’t interested in hospitalist medicine but view our program as a stepping stone to the job they really want here,’’ she says. “We hired and fired someone who wanted her own way all the time. She left for another prestigious hospital. Then there are others who don’t want to teach, but choose a teaching hospital.”

Dr. McKean hopes SHM’s self-assessment tools will help job candidates focus on what they want from a hospital medicine group and avoid the “pebbles” that erode job satisfaction.

IPC, which employs 600 physicians in 100 practices in 24 markets, tried personality testing then discarded it. IPC hired a psychometric firm to devise a psychological profile of “best” and “worst” performing hospitalists. The testers created a test measuring seven key characteristics relating to temperament, intelligence, and clinical skills.

IPC’s CEO Adam Singer, MD, says: “We tested all candidates but found the test ineffective because nearly everyone, including me, got five or better.” He dropped the test, relying instead on extensive interviews. Dr. Singer reviews 2,500 to 3,000 physician resumes annually and spends significant resources on avoiding bad hires. All that hard work doesn’t avoid the occasional mistake.

“I’ve seen everything—the brilliant doctor who can’t function on a team, aloofness, temper tantrums, rudeness, and always pushing responsibility on someone else,” says Dr. Singer. “When something’s wrong, 90% of the time we terminate them ASAP. The other 10% we salvage by finding what’s stressing them, relieving the pressure, and mentoring them into proper behavior.”

Cynthia Stamer, a Dallas-based attorney at Glast, Phillips & Murray, P.C., works extensively with physicians and hospitals and sees young physicians straight from residency joining hospitalist programs “just looking for a job and not focused on whether or not there’s a good personality fit.” She urges job candidates and hirers to better probe the fit.

Stamer finds good hospitalists to be stress jockeys who thrive on the intensity of hospital work. “I think they’re born and not bred,” she says. “They tend to be bored or disruptive in office practices, and to enjoy a pattern of work hard, play hard. The ability to throw the ‘on’ switch and be intense for block scheduling, then be ‘off’ for a block suits them,” she says.

Not That Bad

In a field where an extra pair of hands can make the difference between taking night call or the freedom to take several days off for emergencies, a mediocre team member might seem better than none. Some hospitalist groups would rather pull a bigger load temporarily than tolerate a laggard; others stomach imperfection.

Spotting problems during the hiring process can turn a bad hire into a proper fit. For example, offering a permanent part-time position to someone with young children who can’t commit to full-time employment avoids potential problems. Or, asking enough probing questions might help you discover a physician has a year before a coveted fellowship begins; tailoring a one-year contract for that person optimizes fit. Eliminating managerial tasks for a pure clinician who eschews the leadership fast track works, too.

What to do with the mediocre performer rather than the egregious misfit? Perhaps she consistently arrives to work late, doesn’t complete her charts, and tries to avoid admissions or challenging assignments. A group leader may salvage the situation through mentoring and tying pay to performance. Dr. Singer says: “Underperformers usually don’t understand their impact on the group. We teach them healthcare economics and the flow of dollars. We train them to get the relationship between pay and performance, and hope for results.”

Stamer urges hospitalist leaders to build termination procedures into employment contracts, to document poor performance, and to give severance pay or buy out a contract with a bad hire. “People get testy around disengagement, but if you can take the heat out of the process, it’s better in the long run,” she concludes.

As hospitalist supply approaches demand, avoiding bad hires should be easier. For now, most groups prefer pulling together and working harder rather than abide an outlier. It comes with the territory. TH

Marlene Piturro is a frequent contributor to The Hospitalist.

Hospital medicine groups depend on camaraderie and expertise to carry them through long days and heavy workloads. Group cohesiveness—often fragile—depends on recruiting and keeping hard-working doctors who pull their weight professionally and boost the group’s chemistry.

In a field with five job openings for every qualified candidate, and average annual turnover at 12%, hospital medicine groups can ill afford a bad hire. Whether that person is a practice killer, a cipher who blends into the wallpaper while collecting a paycheck, or a doctor marking time until a fellowship or something better comes along, the group leader must quickly limit a bad hire’s negative impact.

Recognizing that competition to hire hospitalists is fierce, it may seem that avoiding or axing a bad hire—the physician who either doesn’t mesh with your team, is a professional and/or personal train wreck, or has a blue-ribbon pedigree, but performs poorly—is a luxury hospitalist groups can’t afford.

But as Per Danielsson, MD, medical director of Seattle-based Swedish Medical Center’s adult hospitalist program has learned the hard way: “No doctor is better than the wrong doctor. I don’t sugarcoat the demands of our program with prospects. We’re a seasoned hospitalist program, we work hard, and, if we have a position vacant, we’ll work even harder for short periods of time until we find the right person.”

With a hospitalist group of 25 providers, Dr. Danielsson spends more time than he’d like recruiting and interviewing candidates, but he considers it time well spent. “The CV and interview are important, but I’ve devised a list of 12 personality traits that I consider important,” he says. “I share the list with candidates to see if we have a good fit.”

Chris Nussbaum, MD, CEO of Synergy Medical Group, based in Brandon, Fla., says: “They don’t make doctors the way they used to. I don’t see why some hospitalists think seeing 20 to 25 patients a day is such a big deal. I’ve had several tell me that 20 patients a day is no problem—and then they only last one day.” When that happens, Synergy cuts its losses, not allowing a bad hire to linger.

Dr. Nussbaum didn’t think twice about firing one new hire—a physician with an impressive resume who, while writing chart notes at a nursing station, watched a nurse have a seizure, gathered his notes and left the room. “He expected an endocrinologist standing nearby to help out, but it’s outrageous that any hospitalist wouldn’t respond appropriately,” he says. Such callous behavior would send shock waves through any group, and that physician was fired on the spot.

Another organizational disrupter, briefly employed by IPC-the Hospitalist Company (North Hollywood, Calif.) made inflammatory remarks about a hospital’s pre-eminent specialist and other referring physicians. He was fired. Several hospitalist leaders report hiring physicians with stellar pedigrees whose hands consistently strayed to nurses’ derrieres. Those doctors were quickly shown the door.

Robin Ryan, a career coach from Newcastle, Wash., who has prepared office-based physicians for professional moves to hospitalist careers, says the new career path can be confusing. When a physician and a hospitalist group have made a mistake, Ryan says most groups cut their losses by terminating someone who doesn’t fit. “Contracts often require a hefty severance fee, but it’s often the road that groups take,” she says.

Probing Personality

To weed out potential bad hires, employees long have used personality tests. Such tests also help job candidates clarify what matters most to them professionally. The SHM’s Career Satisfaction Task Force has developed a framework for hospitalists to do that. The self-test rests on four pillars of job satisfaction: reward/recognition, workload/schedule, autonomy/control, and community/environment (to view, go to www.hospitalmedicine.org and click “Career Satisfaction White Paper”).

Sylvia McKean, MD, medical director, the Brigham & Women’s Hospital/Faulkner Hospitalist Program in Boston and the task force’s co-chair, urges hospitalists to complete the self-test to maximize a potential job fit.

“All jobs have unpleasant side effects,” says Dr. McKean. “People get sick at bad times. There is high stress and sometimes high error rates. It’s important for a hospitalist to analyze what your needs are and to find an environment that best suits them.”

Dr. McKean also offers wisdom from the other side of desk, having interviewed candidates for coveted spots at Brigham & Women’s hospitalist program. “I’ve interviewed doctors who aren’t interested in hospitalist medicine but view our program as a stepping stone to the job they really want here,’’ she says. “We hired and fired someone who wanted her own way all the time. She left for another prestigious hospital. Then there are others who don’t want to teach, but choose a teaching hospital.”

Dr. McKean hopes SHM’s self-assessment tools will help job candidates focus on what they want from a hospital medicine group and avoid the “pebbles” that erode job satisfaction.

IPC, which employs 600 physicians in 100 practices in 24 markets, tried personality testing then discarded it. IPC hired a psychometric firm to devise a psychological profile of “best” and “worst” performing hospitalists. The testers created a test measuring seven key characteristics relating to temperament, intelligence, and clinical skills.

IPC’s CEO Adam Singer, MD, says: “We tested all candidates but found the test ineffective because nearly everyone, including me, got five or better.” He dropped the test, relying instead on extensive interviews. Dr. Singer reviews 2,500 to 3,000 physician resumes annually and spends significant resources on avoiding bad hires. All that hard work doesn’t avoid the occasional mistake.

“I’ve seen everything—the brilliant doctor who can’t function on a team, aloofness, temper tantrums, rudeness, and always pushing responsibility on someone else,” says Dr. Singer. “When something’s wrong, 90% of the time we terminate them ASAP. The other 10% we salvage by finding what’s stressing them, relieving the pressure, and mentoring them into proper behavior.”

Cynthia Stamer, a Dallas-based attorney at Glast, Phillips & Murray, P.C., works extensively with physicians and hospitals and sees young physicians straight from residency joining hospitalist programs “just looking for a job and not focused on whether or not there’s a good personality fit.” She urges job candidates and hirers to better probe the fit.

Stamer finds good hospitalists to be stress jockeys who thrive on the intensity of hospital work. “I think they’re born and not bred,” she says. “They tend to be bored or disruptive in office practices, and to enjoy a pattern of work hard, play hard. The ability to throw the ‘on’ switch and be intense for block scheduling, then be ‘off’ for a block suits them,” she says.

Not That Bad

In a field where an extra pair of hands can make the difference between taking night call or the freedom to take several days off for emergencies, a mediocre team member might seem better than none. Some hospitalist groups would rather pull a bigger load temporarily than tolerate a laggard; others stomach imperfection.

Spotting problems during the hiring process can turn a bad hire into a proper fit. For example, offering a permanent part-time position to someone with young children who can’t commit to full-time employment avoids potential problems. Or, asking enough probing questions might help you discover a physician has a year before a coveted fellowship begins; tailoring a one-year contract for that person optimizes fit. Eliminating managerial tasks for a pure clinician who eschews the leadership fast track works, too.

What to do with the mediocre performer rather than the egregious misfit? Perhaps she consistently arrives to work late, doesn’t complete her charts, and tries to avoid admissions or challenging assignments. A group leader may salvage the situation through mentoring and tying pay to performance. Dr. Singer says: “Underperformers usually don’t understand their impact on the group. We teach them healthcare economics and the flow of dollars. We train them to get the relationship between pay and performance, and hope for results.”

Stamer urges hospitalist leaders to build termination procedures into employment contracts, to document poor performance, and to give severance pay or buy out a contract with a bad hire. “People get testy around disengagement, but if you can take the heat out of the process, it’s better in the long run,” she concludes.

As hospitalist supply approaches demand, avoiding bad hires should be easier. For now, most groups prefer pulling together and working harder rather than abide an outlier. It comes with the territory. TH

Marlene Piturro is a frequent contributor to The Hospitalist.

VTE Studies Win Grants

Two pharmacist-hospitalist teams each won $50,000 grants June 12 from the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) Research and Education Foundation (Bethesda, Md.) to support development of screening tools and order sets to prevent and treat hospital-acquired venous thromboembolism (VTE).

The grant winners and lead co-investigators from each team:

- Robert Weibert, PharmD, health sciences clinical professor and director of the Anticoagulation Clinic, School of Pharmacy, and Gregory Maynard, MD, MS, head of the Division of Hospital Medicine and associate clinical professor of medicine at the University of California-San Diego (UCSD); and

- Rachel Hroncich, PharmD, pharmacy clinical coordinator of Presbyterian Healthcare Service, and Randle Adair, DO, PhD, a PMG hospitalist in adult medicine from Albuquerque, N.M.

The ASHP, a nonprofit organization, fosters safe medication use.

“We are thrilled that our grant application was selected by the ASHP and excited about the opportunity for our research to improve patient care,” says Dr. Hroncich.

The ASHP Research and Education Foundation grant program, sponsored by Sanofi-Aventis, supports research by hospitalists and hospital pharmacists to treat VTE, with a focus on hospitalized patients and post-discharge follow-up. The grants are geared to help hospitalists and pharmacists reduce hospital-acquired VTE, a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in hospitals.

VTE-related treatment costs $1.5 billion a year, according to researchers at the University of Washington School of Pharmacy in Seattle. ASHP statistics indicate VTE affects more than 450,000 hospitalized patients annually. The condition—an amalgam of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE)—affects a range of hospitalized patients. Gynecologic, orthopedic, urologic, vascular, trauma, and cancer patients all are at risk—as are those with other medical conditions such as congestive heart failure, severe respiratory disease, and obesity, or those who are bedridden.

The ASHP grants help pharmacist-hospitalist teams find tools to screen for VTE. Such tools let clinicians intervene early with at-risk patients. Better screening and intervention requires sound clinical, administrative, and IT processes.

The trick is to encourage busy hospitalists to use a consensus-based VTE screening tool for all hospitalized patients.

While most VTE research involves retrospective chart review of diagnostic codes, Drs. Weibert and Maynard’s grant research goes beyond such studies by identifying patients at risk concurrent with their hospitalizations. Dr. Maynard says the need is urgent: “Hospitals grossly underestimate the risk of VTE. In a 300-bed hospital, at least 150 patients are at risk of hospital-acquired VTE at any time.”

The UCSD team hopes to improve VTE screening by integrating an order set into the hospital’s computer physician order entry (CPOE) system. “The literature points to a bundle of best practices for VTE,” says Dr. Maynard, “including baseline lab work, use of compression stockings, using heparin for an optimal time period, patient education for those on anticoagulants, timely follow-up post discharge, the Society of Hospital Medicine collaborative, etc.”

Based on that body of knowledge and the input of its 15 full-time equivalent hospitalists, UCSD stakeholders in VTE screening debate what is practical and workable, conduct small, paper-based pilot projects, and fine-tune the protocol to integrate it with patient flow through admissions. “As we transition fully to a CPOE in our health system, we will incorporate a VTE order set that is doable and user-friendly,” adds Dr. Maynard.

UCSD’s pharmacist-hospitalist collaboration also encourages residents from both disciplines to work together on integrating protocols into clinical care processes. The team hopes that the VTE protocol will go beyond the inpatient stay by wrapping the protocol into the discharge plan. Dr. Weibert’s anticoagulation and pulmonary embolism clinics also help “build on our strengths,” he says.

The second team is led by newcomers to the grant winner’s circle, Drs. Hroncich (pharmacist) and Adair (hospitalist) from Presbyterian Healthcare Services, Albuquerque, N.M. They base their research on this question: Is it more efficient for the system’s 34 hospitalists to screen out those at low risk of VTE than to screen everyone for high risk?

The investigators have been collecting baseline data on compliance with VTE screening since 2003. Hospitalist use of a VTE screening tool on admissions was 60%, improving to 88% with reminders. “The implication is that 12% of the hospitalists didn’t use the screening tool,” says Dr. Adair. “We found that they were resistant to another piece of paper.” PHS data also showed that seven out of 10 patients had some VTE risk, that co-morbidities and hospitalization increase VTE risk, and that the age at which patients fall prey to VTE is dropping to between 50 and 60.

For the ASHP grant, Drs. Hroncich and Adair will monitor VTE screening on admission to all PHS general medical units. All patients 18 or older admitted to those units during a three-month period will be routinely screened on admission for VTE risk. Drs. Hroncich and Adair will make two VTE-related admission order sets available to hospitalists to complete. The current screening tool is designed to identify patients at risk of developing a VTE based on the presence of risk factors. The second, shorter admission order set will contain a screening tool that assumes that all patients need VTE prophylaxis, except low-risk patients and those with VTE prophylaxis contraindications. “The shorter tool should take only one or two minutes to complete,” says Dr. Hroncich.

The PHS team hopes that the shorter screening tool will overcome resistance to VTE screening. Dr. Hroncich says there are many barriers to VTE screening. They include lack of consensus on the best screening tool on admission, the misperception that VTE isn’t a big problem, lack of reliable processes so at-risk patients don’t fall through the cracks, and a misperception that anti-coagulant therapy is dangerous.

“It’s one thing to treat COPD and heart failure,” adds Dr. Adair, “but if I can prevent VTE with less than a 60-second screening, I can prevent a disease state from happening.” TH

Marlene Piturro is a frequent contributor to The Hospitalist.

Two pharmacist-hospitalist teams each won $50,000 grants June 12 from the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) Research and Education Foundation (Bethesda, Md.) to support development of screening tools and order sets to prevent and treat hospital-acquired venous thromboembolism (VTE).

The grant winners and lead co-investigators from each team:

- Robert Weibert, PharmD, health sciences clinical professor and director of the Anticoagulation Clinic, School of Pharmacy, and Gregory Maynard, MD, MS, head of the Division of Hospital Medicine and associate clinical professor of medicine at the University of California-San Diego (UCSD); and

- Rachel Hroncich, PharmD, pharmacy clinical coordinator of Presbyterian Healthcare Service, and Randle Adair, DO, PhD, a PMG hospitalist in adult medicine from Albuquerque, N.M.

The ASHP, a nonprofit organization, fosters safe medication use.

“We are thrilled that our grant application was selected by the ASHP and excited about the opportunity for our research to improve patient care,” says Dr. Hroncich.

The ASHP Research and Education Foundation grant program, sponsored by Sanofi-Aventis, supports research by hospitalists and hospital pharmacists to treat VTE, with a focus on hospitalized patients and post-discharge follow-up. The grants are geared to help hospitalists and pharmacists reduce hospital-acquired VTE, a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in hospitals.

VTE-related treatment costs $1.5 billion a year, according to researchers at the University of Washington School of Pharmacy in Seattle. ASHP statistics indicate VTE affects more than 450,000 hospitalized patients annually. The condition—an amalgam of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE)—affects a range of hospitalized patients. Gynecologic, orthopedic, urologic, vascular, trauma, and cancer patients all are at risk—as are those with other medical conditions such as congestive heart failure, severe respiratory disease, and obesity, or those who are bedridden.

The ASHP grants help pharmacist-hospitalist teams find tools to screen for VTE. Such tools let clinicians intervene early with at-risk patients. Better screening and intervention requires sound clinical, administrative, and IT processes.

The trick is to encourage busy hospitalists to use a consensus-based VTE screening tool for all hospitalized patients.

While most VTE research involves retrospective chart review of diagnostic codes, Drs. Weibert and Maynard’s grant research goes beyond such studies by identifying patients at risk concurrent with their hospitalizations. Dr. Maynard says the need is urgent: “Hospitals grossly underestimate the risk of VTE. In a 300-bed hospital, at least 150 patients are at risk of hospital-acquired VTE at any time.”

The UCSD team hopes to improve VTE screening by integrating an order set into the hospital’s computer physician order entry (CPOE) system. “The literature points to a bundle of best practices for VTE,” says Dr. Maynard, “including baseline lab work, use of compression stockings, using heparin for an optimal time period, patient education for those on anticoagulants, timely follow-up post discharge, the Society of Hospital Medicine collaborative, etc.”

Based on that body of knowledge and the input of its 15 full-time equivalent hospitalists, UCSD stakeholders in VTE screening debate what is practical and workable, conduct small, paper-based pilot projects, and fine-tune the protocol to integrate it with patient flow through admissions. “As we transition fully to a CPOE in our health system, we will incorporate a VTE order set that is doable and user-friendly,” adds Dr. Maynard.

UCSD’s pharmacist-hospitalist collaboration also encourages residents from both disciplines to work together on integrating protocols into clinical care processes. The team hopes that the VTE protocol will go beyond the inpatient stay by wrapping the protocol into the discharge plan. Dr. Weibert’s anticoagulation and pulmonary embolism clinics also help “build on our strengths,” he says.

The second team is led by newcomers to the grant winner’s circle, Drs. Hroncich (pharmacist) and Adair (hospitalist) from Presbyterian Healthcare Services, Albuquerque, N.M. They base their research on this question: Is it more efficient for the system’s 34 hospitalists to screen out those at low risk of VTE than to screen everyone for high risk?

The investigators have been collecting baseline data on compliance with VTE screening since 2003. Hospitalist use of a VTE screening tool on admissions was 60%, improving to 88% with reminders. “The implication is that 12% of the hospitalists didn’t use the screening tool,” says Dr. Adair. “We found that they were resistant to another piece of paper.” PHS data also showed that seven out of 10 patients had some VTE risk, that co-morbidities and hospitalization increase VTE risk, and that the age at which patients fall prey to VTE is dropping to between 50 and 60.

For the ASHP grant, Drs. Hroncich and Adair will monitor VTE screening on admission to all PHS general medical units. All patients 18 or older admitted to those units during a three-month period will be routinely screened on admission for VTE risk. Drs. Hroncich and Adair will make two VTE-related admission order sets available to hospitalists to complete. The current screening tool is designed to identify patients at risk of developing a VTE based on the presence of risk factors. The second, shorter admission order set will contain a screening tool that assumes that all patients need VTE prophylaxis, except low-risk patients and those with VTE prophylaxis contraindications. “The shorter tool should take only one or two minutes to complete,” says Dr. Hroncich.

The PHS team hopes that the shorter screening tool will overcome resistance to VTE screening. Dr. Hroncich says there are many barriers to VTE screening. They include lack of consensus on the best screening tool on admission, the misperception that VTE isn’t a big problem, lack of reliable processes so at-risk patients don’t fall through the cracks, and a misperception that anti-coagulant therapy is dangerous.

“It’s one thing to treat COPD and heart failure,” adds Dr. Adair, “but if I can prevent VTE with less than a 60-second screening, I can prevent a disease state from happening.” TH

Marlene Piturro is a frequent contributor to The Hospitalist.

Two pharmacist-hospitalist teams each won $50,000 grants June 12 from the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) Research and Education Foundation (Bethesda, Md.) to support development of screening tools and order sets to prevent and treat hospital-acquired venous thromboembolism (VTE).

The grant winners and lead co-investigators from each team:

- Robert Weibert, PharmD, health sciences clinical professor and director of the Anticoagulation Clinic, School of Pharmacy, and Gregory Maynard, MD, MS, head of the Division of Hospital Medicine and associate clinical professor of medicine at the University of California-San Diego (UCSD); and

- Rachel Hroncich, PharmD, pharmacy clinical coordinator of Presbyterian Healthcare Service, and Randle Adair, DO, PhD, a PMG hospitalist in adult medicine from Albuquerque, N.M.

The ASHP, a nonprofit organization, fosters safe medication use.

“We are thrilled that our grant application was selected by the ASHP and excited about the opportunity for our research to improve patient care,” says Dr. Hroncich.

The ASHP Research and Education Foundation grant program, sponsored by Sanofi-Aventis, supports research by hospitalists and hospital pharmacists to treat VTE, with a focus on hospitalized patients and post-discharge follow-up. The grants are geared to help hospitalists and pharmacists reduce hospital-acquired VTE, a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in hospitals.

VTE-related treatment costs $1.5 billion a year, according to researchers at the University of Washington School of Pharmacy in Seattle. ASHP statistics indicate VTE affects more than 450,000 hospitalized patients annually. The condition—an amalgam of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE)—affects a range of hospitalized patients. Gynecologic, orthopedic, urologic, vascular, trauma, and cancer patients all are at risk—as are those with other medical conditions such as congestive heart failure, severe respiratory disease, and obesity, or those who are bedridden.

The ASHP grants help pharmacist-hospitalist teams find tools to screen for VTE. Such tools let clinicians intervene early with at-risk patients. Better screening and intervention requires sound clinical, administrative, and IT processes.

The trick is to encourage busy hospitalists to use a consensus-based VTE screening tool for all hospitalized patients.

While most VTE research involves retrospective chart review of diagnostic codes, Drs. Weibert and Maynard’s grant research goes beyond such studies by identifying patients at risk concurrent with their hospitalizations. Dr. Maynard says the need is urgent: “Hospitals grossly underestimate the risk of VTE. In a 300-bed hospital, at least 150 patients are at risk of hospital-acquired VTE at any time.”

The UCSD team hopes to improve VTE screening by integrating an order set into the hospital’s computer physician order entry (CPOE) system. “The literature points to a bundle of best practices for VTE,” says Dr. Maynard, “including baseline lab work, use of compression stockings, using heparin for an optimal time period, patient education for those on anticoagulants, timely follow-up post discharge, the Society of Hospital Medicine collaborative, etc.”

Based on that body of knowledge and the input of its 15 full-time equivalent hospitalists, UCSD stakeholders in VTE screening debate what is practical and workable, conduct small, paper-based pilot projects, and fine-tune the protocol to integrate it with patient flow through admissions. “As we transition fully to a CPOE in our health system, we will incorporate a VTE order set that is doable and user-friendly,” adds Dr. Maynard.

UCSD’s pharmacist-hospitalist collaboration also encourages residents from both disciplines to work together on integrating protocols into clinical care processes. The team hopes that the VTE protocol will go beyond the inpatient stay by wrapping the protocol into the discharge plan. Dr. Weibert’s anticoagulation and pulmonary embolism clinics also help “build on our strengths,” he says.

The second team is led by newcomers to the grant winner’s circle, Drs. Hroncich (pharmacist) and Adair (hospitalist) from Presbyterian Healthcare Services, Albuquerque, N.M. They base their research on this question: Is it more efficient for the system’s 34 hospitalists to screen out those at low risk of VTE than to screen everyone for high risk?

The investigators have been collecting baseline data on compliance with VTE screening since 2003. Hospitalist use of a VTE screening tool on admissions was 60%, improving to 88% with reminders. “The implication is that 12% of the hospitalists didn’t use the screening tool,” says Dr. Adair. “We found that they were resistant to another piece of paper.” PHS data also showed that seven out of 10 patients had some VTE risk, that co-morbidities and hospitalization increase VTE risk, and that the age at which patients fall prey to VTE is dropping to between 50 and 60.

For the ASHP grant, Drs. Hroncich and Adair will monitor VTE screening on admission to all PHS general medical units. All patients 18 or older admitted to those units during a three-month period will be routinely screened on admission for VTE risk. Drs. Hroncich and Adair will make two VTE-related admission order sets available to hospitalists to complete. The current screening tool is designed to identify patients at risk of developing a VTE based on the presence of risk factors. The second, shorter admission order set will contain a screening tool that assumes that all patients need VTE prophylaxis, except low-risk patients and those with VTE prophylaxis contraindications. “The shorter tool should take only one or two minutes to complete,” says Dr. Hroncich.

The PHS team hopes that the shorter screening tool will overcome resistance to VTE screening. Dr. Hroncich says there are many barriers to VTE screening. They include lack of consensus on the best screening tool on admission, the misperception that VTE isn’t a big problem, lack of reliable processes so at-risk patients don’t fall through the cracks, and a misperception that anti-coagulant therapy is dangerous.

“It’s one thing to treat COPD and heart failure,” adds Dr. Adair, “but if I can prevent VTE with less than a 60-second screening, I can prevent a disease state from happening.” TH

Marlene Piturro is a frequent contributor to The Hospitalist.

Efficiency Rules

While nationwide demand for hospitalists outstrips supply, hospitals across the country are looking at how their hospitalists and their hospital medicine groups weigh in on efficiency.

The notion of efficiency at a time of rapid growth may seem counterintuitive, but healthcare dollars are always hotly contested, and an efficient hospitalist program has a better chance of capturing them than a less-efficient one.

Even the definition of efficiency is being refined. Stakeholders scrutinizing compensation packages, key clinical indicators, productivity and quality metrics, scheduling, average daily census, and patient handoffs to gauge whether or not their group has a competitive edge over others. And hospital medicine group (HMG) leaders are scrutinizing themselves because they know hospitals increasingly are inviting more than one HMG to work under their roofs—the better to serve different populations and compare one with another.

How to Measure Efficiency

An evolving medical discipline that aspires to specialize in internal medicine, hospital medicine is in the process of developing a consensus definition of efficiency for itself. Major variables included in the calculation are obvious: average daily census, length of stay (LOS), case mix-adjusted costs, severity, and readmission rates. Other, harder-to-quantify dimensions include how a hospitalist group practice affects mortality, and how scheduling, variable costs, hospitalist group type, subsidies, and level of expertise play out.

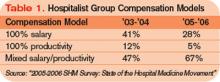

The foundation on which hospitalist groups build their efficiencies is the group type. In itself, how a hospitalist group chooses to organize itself reflects a maturing marketplace. SHM’s 2005-2006 productivity survey shows an increase in multistate hospitalist groups, up from 9% in ’03-’04 to 19% in the latest survey. Local private hospitalist groups fell from 20% in ’03-’04 to 12% in ’05-’06. The percentage of academic hospitalist groups rose from 16% to 20% in the same period.

It’s unclear how to interpret the shift from local to multistate hospitalist groups and the increase in academic medical center programs, but these trends bear watching. Comparison of the two most recent SHM surveys shows compensation models are also growing up, reflecting the need to balance base salary with productivity.

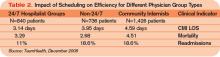

A major indicator of hospital group efficiency is the performance of groups with hospitalists on duty 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Although hospital administrators and hospitalist leaders struggle with the economics of providing night coverage when admissions are slow, such coverage pays off in quality and efficiency.

Stacy Goldsholl, MD, president of TeamHealth Hospital Medicine, a healthcare outsourcing firm based in Knoxville, Tenn., has long advocated 24/7 coverage as a crucial element in HMG efficiency. Even though she estimates that night coverage adds approximately $10,000 in subsidies to an average compensation package for a full-time hospitalist, such coverage improves efficiency in length of stay adjusted for severity and in readmissions. Full coverage allows hospitalists to be better integrated into the hospital in a way that fewer hours don’t.

“How hospitalists who cover 24/7 are used varies,” says Dr. Goldsholl. “Doing night admissions for community doctors, [working] as intensivist extenders, helping with ED [emergency department] throughput, being on rapid response teams—all are important contributors to improved efficiency,” says Dr. Goldsholl.

For Dr. Goldsholl, who has at least one academic medical center—Good Samaritan in Los Angeles at the University of Southern California Keck School of Medicine—on her roster, hospitalist group efficiency and productivity are major concerns for academic and community hospital administrators footing the bill for such services.

“Usually, TeamHealth is the exclusive hospitalist medicine provider contracting with a community hospital,” she explains. “Once we have been in a hospital for a while, we tend to see a progression in our responsibilities. Mostly we start with unassigned patients, then we expand to cover private primary care physicians’ patients. Then we co-manage complex cases with sub-specialists.”

Despite operating mostly in community hospitals, Dr. Goldsholl has fielded more queries from academic medical centers (AMCs) in the past several years.

“We’re definitely getting more interest from AMCs,” Dr. Goldsholl notes. “The work-hours restriction on residents—faculty who are uninterested in being hospitalists—whatever is driving their interest, they’re looking for solutions for handling their unassigned patients and beyond. To outsource to a private hospitalist company, an academic medical center would have to be in some pain, but interest is definitely picking up.”

Cogent Healthcare’s June 2006 contract with Temple University Hospital (TUH), Philadelphia, to provide a 24/7 hospitalist program of teaching and non-teaching services is another example of hospitals striving for efficiency. To better reach its clinical, economic, and regulatory goals, TUH switched from its own academic hospitalist group to partner with Cogent to manage its adult medical/surgical population. It’s too soon to gauge the results.

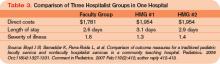

Despite stakeholders’ need to know more about which hospitalist group structure is most efficient, there’s little published data on AMC versus private group efficiency. One important study, published in the American Journal of Medicine (AJM) in May 2005, compared an academic hospitalist group with a private hospitalist group and community internists on several efficiency measures. The academic hospitalists’ patients had a 13% shorter LOS than those patients cared for by other groups and academic hospitalists had lowered costs by $173 per case, versus $109 for the private hospitalist group. The academic hospitalists also had a 20% relative risk reduction for severity of illness over the community physicians.

Lakshmi Halasyamani, MD, the AJM study’s lead author and chair of the Hospital Quality and Patient Safety Committee for SHM, speculated that the academic hospitalist groups’ efficiency resulted from fewer handoffs and that academic hospitalists’ relationships with their hospitals were more aligned than those of outsiders, both from financial and quality perspectives. Additionally, the academic hospitalist group used the hospital’s computerized physician order entry system and followed its protocols for clinical pathways and core measures. Scheduling also made a difference. The academic group worked in half-month blocks for an average of 14 weeks, while the private hospitalists worked from 8 a.m. to 6 p.m. on weekdays and some nights and weekends, leaving moonlighters to cover 75% of nights, weekends, and holidays and providing for rockier handoffs.

Another study comparing a traditional pediatric faculty group with two private hospitalist groups at St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center of Phoenix showed that the faculty group outperformed the private hospitalists on all measures.

The authors concluded that faculty models can be as efficient as or more efficient than private groups in terms of direct costs and LOS.

Fine Tuning

Although academic hospitalist groups have been thought of as less efficient than private hospitalist groups because the former tend to use salaried employees while the latter tend to compensate employees based more on performance, the data cited above indicate academic hospitalist groups may have a competitive edge with regard to efficiency. What may account for the difference is that academic hospitalists are familiar with and often products of their hospital’s culture and mores. Unlike physicians working for private hospitalist groups with their own structure and culture, academic hospitalists are of a piece with their hospital. It’s common to find academic hospitalists who return to their medical school alma mater after a stint in an office-based practice. Some never left, joining the academic hospitalist group directly from residency.

For the chief of a hospitalist program, being so attuned to the hospital’s rhythms can be a mixed blessing.

Pat Cawley, MD, is the hospitalist program director and founder of the academic hospitalist group at the Charleston-based Medical University of South Carolina’s Hospital. He has a hard time focusing on hospitalist group efficiency, though, when he’s still flat-out recruiting.

“Demand for hospitalists is still way outstripping supply,” says Dr. Cawley. “We currently have nine hospitalists and plan to add five more this year, but we could actually use 10 more.”

The South Carolina market is competitive, with other hospitals planning to establish hospitalist medicine programs and vying with Dr. Cawley’s program for fresh physicians. Medical University Hospital’s hospitalist group started in July 2003 with four physicians and has kept growing. The hospitalists spend most of their time functioning as a teaching service and also cover a long-term acute-care facility at another hospital.

Defining efficiency in South Carolina’s booming market is secondary to recruiting and incorporating new physicians as team members. Dr. Cawley uses average daily census (ADC) as an efficiency benchmark: 15-20 patients per hospitalist is productive, although many doctors are comfortable at 12.

“We looked at our learning curve, about 10-12,” points out Dr. Cawley. “We think 15-20 is better, although some places are reporting an ADC of 22. But after a certain point, performance doesn’t appear to improve.”

A big problem with improving hospitalist group efficiency, according to Dr. Cawley, is hospital inefficiency: “Lack of IT to get lab results quickly, not enough nursing and secretarial support for admissions and discharges, policies on contacting the primary doc versus having a standing order for a procedure—all decrease efficiency.”

He’d also like his hospital administrators to allow nurses to pronounce death (common in community hospitals but less so in AMCs). “The power of hospitalists is to challenge the hospital’s inefficiencies, to break down the barriers to more efficient practices,” adds Dr. Cawley. “Many institutions need huge culture change, and hospitalists must lead the way.”

A close watcher of hospitalist performance, Scott Oxenhandler, MD, medical director of the Memorial Hospitalist Group in Hollywood, Fla., heads a hospitalist group he started in June 2004 that now has 23 physicians and two nurse practitioners. Memorial Hospital also has two other private hospitalist groups. While Dr. Oxenhandler’s group handles unassigned patients (55%) and Medicaid/Medicare patients (45%), the other hospitalist groups have captured the more lucrative business of managed care and other commercially insured patients.

—Per Danielsson, MD, medical director, Swedish Medical Center Adult Hospitalist Program, Seattle

Dr. Oxenhandler says efficiency is a complicated issue involving several key components. “Following evidence-based medicine protocols and CMS core measures are fairly straightforward [ideas] for all of us,” he says, “but financial measures are more complex.”

He has taken aim at adjusted variable costs per discharge on lab tests, pharmacy, and radiology, “three areas where I know that our group can improve,” he adds.

As for how hard and how efficiently a hospitalist works, Dr. Oxenhandler is taking a closer look at that as his group and the field mature. “We know that average daily census can be deceiving and RVUs [relative value units] are more relevant to efficiency but not perfect,” he says. “Another factor is tenure with the hospitalist group. For the physician to excel and to mature clinically, he or she needs to stay with a hospitalist group long enough to improve readmission rates and to get a sense of how to better manage clinical resources.’’

Dr. Oxenhandler describes a patient presenting with heart failure and anemia to show how a hospitalist’s clinical skills might mature. After several days of repeated hemoglobin studies indicating anemia, the hospitalist might refer the patient—once stabilized and discharged—to his primary physician for an outpatient work-up for possible colon cancer—rather than do so during the hospitalization.

Dr. Oxenhandler has contemplated pursuing managed care contracts but hesitates because his hospitalist group’s clinical and cost performance is equal to that of the hospitalist group that currently holds such contracts. “Why should they switch to us unless we can outperform the other group?” he muses. “Plus, there would be added cost for us in more paperwork and administration, and we’d have to improve our efficiency to make it worthwhile.”

Per Danielsson, MD, Swedish Medical Center’s Adult Hospitalist Program’s medical director, has hospitalists rotating among the First Hill, Cherry Hill, and Ballard campuses in Seattle, Wash. Demand for hospitalist services at the sites keeps growing, and Dr. Danielsson sees no end in sight. “Today’s hospital stays are getting shorter, and the patients are sicker, and there is increasing pressure for greater efficiency here,” he says.

Overall, clinicians, administrators, and researchers need to zero in on the organizational factors of hospitalist groups—from scheduling to 24/7 coverage, handoffs, and use of in-hospital resources—to improve efficiency. At present, academic hospitalist groups appear to have a slight edge because they’re tied more closely to hospital personnel, technology, and care pathways than private groups that come from outside the hospital. But there isn’t enough data either way to say which group type is the most efficient. TH

Marlene Piturro is a frequent contributor to The Hospitalist.

While nationwide demand for hospitalists outstrips supply, hospitals across the country are looking at how their hospitalists and their hospital medicine groups weigh in on efficiency.

The notion of efficiency at a time of rapid growth may seem counterintuitive, but healthcare dollars are always hotly contested, and an efficient hospitalist program has a better chance of capturing them than a less-efficient one.

Even the definition of efficiency is being refined. Stakeholders scrutinizing compensation packages, key clinical indicators, productivity and quality metrics, scheduling, average daily census, and patient handoffs to gauge whether or not their group has a competitive edge over others. And hospital medicine group (HMG) leaders are scrutinizing themselves because they know hospitals increasingly are inviting more than one HMG to work under their roofs—the better to serve different populations and compare one with another.

How to Measure Efficiency

An evolving medical discipline that aspires to specialize in internal medicine, hospital medicine is in the process of developing a consensus definition of efficiency for itself. Major variables included in the calculation are obvious: average daily census, length of stay (LOS), case mix-adjusted costs, severity, and readmission rates. Other, harder-to-quantify dimensions include how a hospitalist group practice affects mortality, and how scheduling, variable costs, hospitalist group type, subsidies, and level of expertise play out.

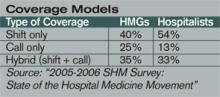

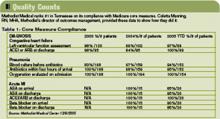

The foundation on which hospitalist groups build their efficiencies is the group type. In itself, how a hospitalist group chooses to organize itself reflects a maturing marketplace. SHM’s 2005-2006 productivity survey shows an increase in multistate hospitalist groups, up from 9% in ’03-’04 to 19% in the latest survey. Local private hospitalist groups fell from 20% in ’03-’04 to 12% in ’05-’06. The percentage of academic hospitalist groups rose from 16% to 20% in the same period.

It’s unclear how to interpret the shift from local to multistate hospitalist groups and the increase in academic medical center programs, but these trends bear watching. Comparison of the two most recent SHM surveys shows compensation models are also growing up, reflecting the need to balance base salary with productivity.

A major indicator of hospital group efficiency is the performance of groups with hospitalists on duty 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Although hospital administrators and hospitalist leaders struggle with the economics of providing night coverage when admissions are slow, such coverage pays off in quality and efficiency.

Stacy Goldsholl, MD, president of TeamHealth Hospital Medicine, a healthcare outsourcing firm based in Knoxville, Tenn., has long advocated 24/7 coverage as a crucial element in HMG efficiency. Even though she estimates that night coverage adds approximately $10,000 in subsidies to an average compensation package for a full-time hospitalist, such coverage improves efficiency in length of stay adjusted for severity and in readmissions. Full coverage allows hospitalists to be better integrated into the hospital in a way that fewer hours don’t.

“How hospitalists who cover 24/7 are used varies,” says Dr. Goldsholl. “Doing night admissions for community doctors, [working] as intensivist extenders, helping with ED [emergency department] throughput, being on rapid response teams—all are important contributors to improved efficiency,” says Dr. Goldsholl.

For Dr. Goldsholl, who has at least one academic medical center—Good Samaritan in Los Angeles at the University of Southern California Keck School of Medicine—on her roster, hospitalist group efficiency and productivity are major concerns for academic and community hospital administrators footing the bill for such services.

“Usually, TeamHealth is the exclusive hospitalist medicine provider contracting with a community hospital,” she explains. “Once we have been in a hospital for a while, we tend to see a progression in our responsibilities. Mostly we start with unassigned patients, then we expand to cover private primary care physicians’ patients. Then we co-manage complex cases with sub-specialists.”

Despite operating mostly in community hospitals, Dr. Goldsholl has fielded more queries from academic medical centers (AMCs) in the past several years.

“We’re definitely getting more interest from AMCs,” Dr. Goldsholl notes. “The work-hours restriction on residents—faculty who are uninterested in being hospitalists—whatever is driving their interest, they’re looking for solutions for handling their unassigned patients and beyond. To outsource to a private hospitalist company, an academic medical center would have to be in some pain, but interest is definitely picking up.”

Cogent Healthcare’s June 2006 contract with Temple University Hospital (TUH), Philadelphia, to provide a 24/7 hospitalist program of teaching and non-teaching services is another example of hospitals striving for efficiency. To better reach its clinical, economic, and regulatory goals, TUH switched from its own academic hospitalist group to partner with Cogent to manage its adult medical/surgical population. It’s too soon to gauge the results.

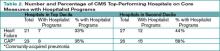

Despite stakeholders’ need to know more about which hospitalist group structure is most efficient, there’s little published data on AMC versus private group efficiency. One important study, published in the American Journal of Medicine (AJM) in May 2005, compared an academic hospitalist group with a private hospitalist group and community internists on several efficiency measures. The academic hospitalists’ patients had a 13% shorter LOS than those patients cared for by other groups and academic hospitalists had lowered costs by $173 per case, versus $109 for the private hospitalist group. The academic hospitalists also had a 20% relative risk reduction for severity of illness over the community physicians.

Lakshmi Halasyamani, MD, the AJM study’s lead author and chair of the Hospital Quality and Patient Safety Committee for SHM, speculated that the academic hospitalist groups’ efficiency resulted from fewer handoffs and that academic hospitalists’ relationships with their hospitals were more aligned than those of outsiders, both from financial and quality perspectives. Additionally, the academic hospitalist group used the hospital’s computerized physician order entry system and followed its protocols for clinical pathways and core measures. Scheduling also made a difference. The academic group worked in half-month blocks for an average of 14 weeks, while the private hospitalists worked from 8 a.m. to 6 p.m. on weekdays and some nights and weekends, leaving moonlighters to cover 75% of nights, weekends, and holidays and providing for rockier handoffs.

Another study comparing a traditional pediatric faculty group with two private hospitalist groups at St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center of Phoenix showed that the faculty group outperformed the private hospitalists on all measures.

The authors concluded that faculty models can be as efficient as or more efficient than private groups in terms of direct costs and LOS.

Fine Tuning

Although academic hospitalist groups have been thought of as less efficient than private hospitalist groups because the former tend to use salaried employees while the latter tend to compensate employees based more on performance, the data cited above indicate academic hospitalist groups may have a competitive edge with regard to efficiency. What may account for the difference is that academic hospitalists are familiar with and often products of their hospital’s culture and mores. Unlike physicians working for private hospitalist groups with their own structure and culture, academic hospitalists are of a piece with their hospital. It’s common to find academic hospitalists who return to their medical school alma mater after a stint in an office-based practice. Some never left, joining the academic hospitalist group directly from residency.

For the chief of a hospitalist program, being so attuned to the hospital’s rhythms can be a mixed blessing.

Pat Cawley, MD, is the hospitalist program director and founder of the academic hospitalist group at the Charleston-based Medical University of South Carolina’s Hospital. He has a hard time focusing on hospitalist group efficiency, though, when he’s still flat-out recruiting.

“Demand for hospitalists is still way outstripping supply,” says Dr. Cawley. “We currently have nine hospitalists and plan to add five more this year, but we could actually use 10 more.”

The South Carolina market is competitive, with other hospitals planning to establish hospitalist medicine programs and vying with Dr. Cawley’s program for fresh physicians. Medical University Hospital’s hospitalist group started in July 2003 with four physicians and has kept growing. The hospitalists spend most of their time functioning as a teaching service and also cover a long-term acute-care facility at another hospital.

Defining efficiency in South Carolina’s booming market is secondary to recruiting and incorporating new physicians as team members. Dr. Cawley uses average daily census (ADC) as an efficiency benchmark: 15-20 patients per hospitalist is productive, although many doctors are comfortable at 12.

“We looked at our learning curve, about 10-12,” points out Dr. Cawley. “We think 15-20 is better, although some places are reporting an ADC of 22. But after a certain point, performance doesn’t appear to improve.”

A big problem with improving hospitalist group efficiency, according to Dr. Cawley, is hospital inefficiency: “Lack of IT to get lab results quickly, not enough nursing and secretarial support for admissions and discharges, policies on contacting the primary doc versus having a standing order for a procedure—all decrease efficiency.”

He’d also like his hospital administrators to allow nurses to pronounce death (common in community hospitals but less so in AMCs). “The power of hospitalists is to challenge the hospital’s inefficiencies, to break down the barriers to more efficient practices,” adds Dr. Cawley. “Many institutions need huge culture change, and hospitalists must lead the way.”

A close watcher of hospitalist performance, Scott Oxenhandler, MD, medical director of the Memorial Hospitalist Group in Hollywood, Fla., heads a hospitalist group he started in June 2004 that now has 23 physicians and two nurse practitioners. Memorial Hospital also has two other private hospitalist groups. While Dr. Oxenhandler’s group handles unassigned patients (55%) and Medicaid/Medicare patients (45%), the other hospitalist groups have captured the more lucrative business of managed care and other commercially insured patients.

—Per Danielsson, MD, medical director, Swedish Medical Center Adult Hospitalist Program, Seattle

Dr. Oxenhandler says efficiency is a complicated issue involving several key components. “Following evidence-based medicine protocols and CMS core measures are fairly straightforward [ideas] for all of us,” he says, “but financial measures are more complex.”

He has taken aim at adjusted variable costs per discharge on lab tests, pharmacy, and radiology, “three areas where I know that our group can improve,” he adds.

As for how hard and how efficiently a hospitalist works, Dr. Oxenhandler is taking a closer look at that as his group and the field mature. “We know that average daily census can be deceiving and RVUs [relative value units] are more relevant to efficiency but not perfect,” he says. “Another factor is tenure with the hospitalist group. For the physician to excel and to mature clinically, he or she needs to stay with a hospitalist group long enough to improve readmission rates and to get a sense of how to better manage clinical resources.’’

Dr. Oxenhandler describes a patient presenting with heart failure and anemia to show how a hospitalist’s clinical skills might mature. After several days of repeated hemoglobin studies indicating anemia, the hospitalist might refer the patient—once stabilized and discharged—to his primary physician for an outpatient work-up for possible colon cancer—rather than do so during the hospitalization.

Dr. Oxenhandler has contemplated pursuing managed care contracts but hesitates because his hospitalist group’s clinical and cost performance is equal to that of the hospitalist group that currently holds such contracts. “Why should they switch to us unless we can outperform the other group?” he muses. “Plus, there would be added cost for us in more paperwork and administration, and we’d have to improve our efficiency to make it worthwhile.”

Per Danielsson, MD, Swedish Medical Center’s Adult Hospitalist Program’s medical director, has hospitalists rotating among the First Hill, Cherry Hill, and Ballard campuses in Seattle, Wash. Demand for hospitalist services at the sites keeps growing, and Dr. Danielsson sees no end in sight. “Today’s hospital stays are getting shorter, and the patients are sicker, and there is increasing pressure for greater efficiency here,” he says.

Overall, clinicians, administrators, and researchers need to zero in on the organizational factors of hospitalist groups—from scheduling to 24/7 coverage, handoffs, and use of in-hospital resources—to improve efficiency. At present, academic hospitalist groups appear to have a slight edge because they’re tied more closely to hospital personnel, technology, and care pathways than private groups that come from outside the hospital. But there isn’t enough data either way to say which group type is the most efficient. TH

Marlene Piturro is a frequent contributor to The Hospitalist.

While nationwide demand for hospitalists outstrips supply, hospitals across the country are looking at how their hospitalists and their hospital medicine groups weigh in on efficiency.

The notion of efficiency at a time of rapid growth may seem counterintuitive, but healthcare dollars are always hotly contested, and an efficient hospitalist program has a better chance of capturing them than a less-efficient one.

Even the definition of efficiency is being refined. Stakeholders scrutinizing compensation packages, key clinical indicators, productivity and quality metrics, scheduling, average daily census, and patient handoffs to gauge whether or not their group has a competitive edge over others. And hospital medicine group (HMG) leaders are scrutinizing themselves because they know hospitals increasingly are inviting more than one HMG to work under their roofs—the better to serve different populations and compare one with another.

How to Measure Efficiency

An evolving medical discipline that aspires to specialize in internal medicine, hospital medicine is in the process of developing a consensus definition of efficiency for itself. Major variables included in the calculation are obvious: average daily census, length of stay (LOS), case mix-adjusted costs, severity, and readmission rates. Other, harder-to-quantify dimensions include how a hospitalist group practice affects mortality, and how scheduling, variable costs, hospitalist group type, subsidies, and level of expertise play out.

The foundation on which hospitalist groups build their efficiencies is the group type. In itself, how a hospitalist group chooses to organize itself reflects a maturing marketplace. SHM’s 2005-2006 productivity survey shows an increase in multistate hospitalist groups, up from 9% in ’03-’04 to 19% in the latest survey. Local private hospitalist groups fell from 20% in ’03-’04 to 12% in ’05-’06. The percentage of academic hospitalist groups rose from 16% to 20% in the same period.

It’s unclear how to interpret the shift from local to multistate hospitalist groups and the increase in academic medical center programs, but these trends bear watching. Comparison of the two most recent SHM surveys shows compensation models are also growing up, reflecting the need to balance base salary with productivity.

A major indicator of hospital group efficiency is the performance of groups with hospitalists on duty 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Although hospital administrators and hospitalist leaders struggle with the economics of providing night coverage when admissions are slow, such coverage pays off in quality and efficiency.

Stacy Goldsholl, MD, president of TeamHealth Hospital Medicine, a healthcare outsourcing firm based in Knoxville, Tenn., has long advocated 24/7 coverage as a crucial element in HMG efficiency. Even though she estimates that night coverage adds approximately $10,000 in subsidies to an average compensation package for a full-time hospitalist, such coverage improves efficiency in length of stay adjusted for severity and in readmissions. Full coverage allows hospitalists to be better integrated into the hospital in a way that fewer hours don’t.

“How hospitalists who cover 24/7 are used varies,” says Dr. Goldsholl. “Doing night admissions for community doctors, [working] as intensivist extenders, helping with ED [emergency department] throughput, being on rapid response teams—all are important contributors to improved efficiency,” says Dr. Goldsholl.

For Dr. Goldsholl, who has at least one academic medical center—Good Samaritan in Los Angeles at the University of Southern California Keck School of Medicine—on her roster, hospitalist group efficiency and productivity are major concerns for academic and community hospital administrators footing the bill for such services.

“Usually, TeamHealth is the exclusive hospitalist medicine provider contracting with a community hospital,” she explains. “Once we have been in a hospital for a while, we tend to see a progression in our responsibilities. Mostly we start with unassigned patients, then we expand to cover private primary care physicians’ patients. Then we co-manage complex cases with sub-specialists.”

Despite operating mostly in community hospitals, Dr. Goldsholl has fielded more queries from academic medical centers (AMCs) in the past several years.

“We’re definitely getting more interest from AMCs,” Dr. Goldsholl notes. “The work-hours restriction on residents—faculty who are uninterested in being hospitalists—whatever is driving their interest, they’re looking for solutions for handling their unassigned patients and beyond. To outsource to a private hospitalist company, an academic medical center would have to be in some pain, but interest is definitely picking up.”

Cogent Healthcare’s June 2006 contract with Temple University Hospital (TUH), Philadelphia, to provide a 24/7 hospitalist program of teaching and non-teaching services is another example of hospitals striving for efficiency. To better reach its clinical, economic, and regulatory goals, TUH switched from its own academic hospitalist group to partner with Cogent to manage its adult medical/surgical population. It’s too soon to gauge the results.